Working with Families

1 Describe the occupations and functions of families using family systems theory.

2 Appreciate the diversity of families and define methods to learn about a family’s culture and background.

3 Explore the implications of having a child with special needs with regard to the co-occupations of family members.

4 Analyze the implications of having a child with special needs with regard to family function.

5 Synthesize information about the family life cycle and transitions to identify times of potential stress for families of children with special needs.

6 Specify the roles of the occupational therapist in collaboration with families.

7 Understand how to establish and maintain partnership with a family.

8 Enact alternative methods of communication that promote family–therapist partnerships.

9 Describe ways families can be empowered to facilitate their children’s development.

10 Explain strategies for supporting the strengths of families facing multiple challenges.

This chapter introduces a range of issues related to families, particularly families of children who have special developmental or health care needs. It considers how family members fulfill the functions of a family by collectively engaging in daily or weekly activities and by sharing special events. The chapter explores factors that contribute to the variety of families with whom therapists may work in providing occupational therapy for children. Having presented this background in the occupations of families and family diversity, the chapter then turns to the ways the special needs of children bring opportunities and challenges to families. This discussion includes the ways that having a child with disabilities can influence how family members organize their time, engage in activities, and interact with one another. Throughout the chapter, the importance of a family-centered philosophy and evidence from the literature are discussed.

REASONS TO STUDY ABOUT FAMILIES

Families are complex systems. Having a child with a disability or chronic health condition, which can happen in families anywhere on the socioeconomic spectrum, of any educational, ethnic, or genetic background, adds an appreciable degree of stress into this complex system. There is a greater incidence of negative outcomes when the odds are stacked against that family because of low socioeconomic status, poor education, minority status, and difficult genetic structure. Occupational therapists encounter all varieties of families and must be prepared to work with them all. Children cannot be treated as isolated individuals; they are members of families, social units that shape behavior and life experiences. Evidence shows that child outcomes will be shaped by how well therapists communicate with families and how well the partnership between them has been established.25,52,79 Learning about family systems is important preparation for working in any practice setting.

The development of children’s occupations cannot be understood without insight into what shapes their daily activities. Young children first learn about activities, how to perform them, what activities mean, and what to expect as the outcomes of their efforts within the family context.67 Although children’s activities vary from one culture to the next, universally their families play a major role in guiding children in how to spend their time, what to do, and why the things they do are important.88,135,166 All major health-related disciplines, including but not limited to psychology, sociology, and nursing practice, use the ecological view of children and the family: that each is interconnected with the other and the environments they experience. The more fully occupational therapists understand the influences on the way families operate in their daily routines and their goals for the ways children spend their time, the better prepared they will be to support each family in helping the child engage in activities the family values.

Another reason to study families explicitly is to circumvent the inclination to reference one’s own family experiences as a template for the way families operate. Walsh points out that when people speak of “the family,” they suggest a socially constructed image of a “normal” family, giving the impression that an ideal family exists in which optimal development occurs.174 In reality, many different types of families are successfully raising children. In this chapter, two or more people who share an enduring emotional bond, a commitment to pool resources, and carry out the typical family functions can be seen as a family.39,86,166,175 This chapter focuses on families raising children. One or more parents, grandparents, and stepparents, as well as adoptive or foster parents, can successfully bring up children. The authors refer to the caregiving adult as the “parent” of the child, and focus specifically on the “parent” only when it is germane to the discussion of family diversity (Box 5-1).

A third reason to study families is that the involvement of family members is central to the best practice of occupational therapy. In addition to organizing and enabling daily activities, the family provides the child’s most enduring set of relationships throughout childhood, into early adulthood, and possibly beyond. During the course of his or her lifetime, a person with a disability may receive services from people working through health services, educational programs, and social agencies. These relationships exist because professionals bring expertise required by the special needs of the young person. As the type of services needed changes, professionals enter and leave the young person’s life. The family represents a source of continuity across this changing pattern of professional involvement. The family forms a unique emotional attachment to their child, and their continuous involvement gives them special insight into the child’s needs, abilities, and occupational interests. In light of the family’s expertise, occupational therapists strive to collaborate with family members, following their lead and supporting their efforts in promoting the well-being and development of the child with special developmental or health care needs.14,25,146Appendix 5-A, which describes the actual experiences of parents raising three children with special needs, provides additional insight into the essential nature of family relationships.

Finally, including families in the process of providing services for children is not just best practice—it is the law. In recognizing the power of families, federal legislation requires service providers and educators to seek the input and permission of a parent or guardian on any assessment, intervention plan, or placement decision. The importance of the family in the early part of the child’s life (from birth to 3 years old) is reflected by the emphasis on family-centered services in Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act 2004.69 It requires providers to talk with parents and develop a family-directed Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) regarding the resources the family needs to promote the child’s optimal development. Later, in the school system, parents are involved in developing the Individualized Educational Program (IEP), which guides special education and related services (see Chapters 23 and 24).

THE FAMILY: A GROUP OF OCCUPATIONAL BEINGS

Family members, individually or together, engage in a variety of activities that are part of home management, caregiving, employed work, education, play, and leisure domains that help them feel connected to each other. A father fulfills one of his family roles by picking up groceries on his way home from work, or a child studies for a test because his parents expect good grades. Family occupations occur when daily activities or special events are shared among family members, such as a parent helping her son study for a test, the whole family going to a movie, or brothers shooting baskets. By engaging in occupations together, families with children fulfill the functions of the family unit expected of them by members of their community. Societies first anticipate that families provide children with a cultural foundation for their development as occupational beings. Family members share and transmit a cultural model, a habitual framework for thinking about events, for determining which activities should be done and when, and for deciding on how to interact.43 By providing a cultural foundation, families ensure that children learn how to approach, perform, and experience activities in a manner consistent with their cultural group. This cultural learning process enables children to acquire the occupations that will make their participation in a variety of contexts possible (Box 5-2). Culture is passed from generation to generation through rituals that include celebrations, traditions, and patterned interactions that give life meaning and construct family identity.143

Occupations have meaning because they convey a sense of self, connect us to other people, and link us to place.54 Routine family occupations give life order and structure the achievement of goals.143 Routine family occupations and special events also form the basis for repeated interpersonal experiences that give family members a sense of support, identity, and emotional well-being.149 The importance of family occupations is reflected by the fact that families create special activities for the specific purpose of spending time together.139

Families are also expected to help their children develop fundamental routines and lifestyle habits that contribute to their physical health and well-being. In the context of receiving care and sharing in family activities children acquire skills that lead to their independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) and learn habits that will influence their health across their life span. For example, in the context of sharing in family dinners and leisure activities after dinner, children establish habits that can reduce or increase future problems with obesity.

A final function of a family is to prepare children for formal or informal educational activities and whatever other practices the community uses to prepare young people to become productive adults.135 Parents, in the context of their daily routines and through their encouragement, provide children participation experiences that influence how they approach learning.68 Families of children with certain disabilities have a greater challenge meeting all these expectations, as will be discussed later in this chapter.

Guided by their cultural models, special circumstances, and community opportunities for activities, families use their resources in different ways (Box 5-3). For example, one family may choose to pay (using financial resources) to have the yard work done so that time (another asset) on Saturday afternoons can be used for having a picnic together. Another family invests interpersonal energies (an emotional resource) to get everyone to help with the yard work on Saturday afternoon so that money will be available to pay for music lessons. Financial, human, and emotional resources, as well as time, are not limitless, and in healthy families, members negotiate a give and take of their assets. For example, mothers of children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD) or attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may set aside extra time to help with their children’s activities and rely on hired help or assistance from other family members to get household tasks done.111,142 Typically, families with children have a hierarchical organization in which one or more family members (e.g., a parent) take major responsibility for determining how the resources are distributed, enabling the family to engage in activities that fulfill family functions. Availability of resources varies for many reasons, both within families and within their communities. Challenges for both families and therapists occur when families or the communities they live in have severely limited resources.147

SYSTEM PERSPECTIVE OF FAMILY OCCUPATIONS

A family functions as a dynamic system in which its members, comprising subsystems, engage in occupations together to fulfill the functions of a family. As with any system, the activity of one person can influence the activities of other members; this is known as interdependent influences that exist among the different parts, much as a change in one piece of a mobile causes movement in every other section. For example, a sixth grader may ask to stay after school with his friend, which means he is not available to watch his sister that afternoon while his mother shops. Consequently, the mother brings her daughter to the grocery store. Shopping with the preschool daughter takes the mother longer than shopping alone. As a result, they do not get home as quickly, and dinner is started late. The interdependent nature of family members’ activities is illustrated by the fact that the boy’s choice of what he wanted to do in the afternoon altered the activities of his mother and sister and indirectly affected the family’s mealtime routine that evening. Recognizing that a family functions as a whole, a therapist who suggests an after-school horseback riding class for a child with cerebral palsy can appreciate that the recommendation must be weighed in light of the family resources and the implications of that activity for the entire family system. As a complex social system, family members have to coordinate what they do and when they do things to share in family routines and rituals (Box 5-4). They accomplish this within subsystems, through their communications and family rules.28

With all of the activities a family does and the different members who can carry out these tasks, it would become confusing and draw on family resources if everyone had to negotiate daily who was going to do what, when, and in which way. An effective family system organizes itself into predictable patterns of daily and weekly activities and familiar ways with special events. Guided by their cultural models, and often organized through unspoken family rules, families settle into daily routines for various household activities.26,149 These daily routines include interactive rituals that take on symbolic meaning and seem so matter of course that people do not think of doing them any other way, and they resist changing them.43,143 Bedtime routines for a child, for example, can have a set sequence of taking a bath, brushing teeth, and the parent reading a book. If routines are interrupted, even by a welcomed event, such as a grandparent coming to visit, family members invest extra family resources reconfiguring their daily routines under the changed circumstances. For example, time is spent making up a bed on the sofa rather than giving the daughter a bath, and emotional energy is expended to help the daughter fall asleep in the living room so that the grandparent can sleep in her bedroom. Families may experience the disruption of their daily routines as unsettling and taxing, and it is not uncommon to hear family members sigh in relief when they can return to predictable patterns, that is, when “things get back to normal.”

In addition to routines for daily or weekly activities (Figure 5-1), families also establish predictable patterns for what they do during rituals, such as special events. Family traditions, such as cooking special food for birthday celebrations or sharing leisure activities on Sunday afternoons, help families develop a sense of group cohesion and emotional well-being for family members (Figure 5-2). Families may decide to maintain their traditions rather than address an individual member’s needs because these customary activities fulfill family functions. For example, a family that traditionally vacations with grandparents for several weeks in the summer may value the way special occupations together reinforce their sense of being a family. Conflict with the occupational therapist could arise if the therapist assumes that the family will shorten the traditional vacation to attend some therapy sessions during the summer. When the occupational therapist offers a range of options and asks the family to set priorities, family members can consider all of their routines and traditions and determine how they want occupational therapy services to fit into their lives.

FIGURE 5-1 Matthew and his brother wait for the school bus. Courtesy Jill and Mark McQuaid, Dublin, Ohio.

FIGURE 5-2 Matthew’s family celebrates Dad’s birthday. Courtesy Jill and Mark McQuaid, Dublin, Ohio.

Celebrations are predictable patterns of doing activities, such as religious rituals, that are shared with members of the community. Therefore, what is done during family celebrations may be similar to what other families that share a similar background do for the same celebration. This link to others gives family members a sense of meaning associated with their special events that connects them to a community of families. Therapists may be asked for assistance so that children can participate in celebrations. For example, a parent may want positioning suggestions so that her daughter with cerebral palsy will be comfortable during Christmas Eve services. The family of a boy with sensory processing problems may need ideas for coping that they can use while attending a Fourth of July fireworks display with the neighbors. By enabling these children’s occupational engagement, the entire family participates in community celebrations and confirms their identity as a family like every other family raising children.

Among the researchers who have investigated family routines and practices, Fiese and colleagues38,99,149 have examined the meaning of routines and related ritual interactions of families’ daily activities and religious celebrations. Their studies show that families who reported finding more meaning and commitment to their routines and special activities experienced better health of family members and stronger interpersonal relationships. Occupational therapists who suggest home carryover of interventions must be sure that the activities will fit within the family’s values and their existing routines; otherwise the intervention will not be incorporated.13,144,145

FAMILY SUBSYSTEMS

Regardless of the type of family structure (e.g., birth, adoptive, partner, blended, or foster), caregiving adults sharing parental duties need to coordinate their efforts. These adults form the parent subsystem of the family, which can be a positive force and can contribute to the child’s ability to face developmental challenges. Researchers have found a number of different solutions in how parents distribute childcare, realizing that the different forms may all be adaptive if they enable the system to operate and meet family functions.64,176 Studies have found that when a child has a disability, additional time for caregiving co-occupations is required in the mother–child subsystem.29,30 The type and severity of disability the child will affect the amount of time required; for example, Crowe found that mothers of children with multiple disabilities spent at least 1 hour more per day on child-related activities compared with mothers of children with Down syndrome.29 Disabilities that seem to create more stress and caregiving effort for the family include autism, severe and multiple disabilities, behavior disorders, and medical problems that require frequent hospitalization and in-home medical care.23,54,134

Researchers have reported that mothers experience stress from the increased workload of caring for a child with disabilities.54,120,149 In addition, mothers may experience more stress than their husbands because they are typically the primary parent working with the intervention team and, as a result, face greater demands on their time and communication skills.90,93 Mothers often become the conduit for communication, responsible for transferring information and expectations between clinic and family. Therefore, because mothers find themselves caught between the perspectives of both the professionals and family members, the professional must be especially sensitive to the needs of mothers.30,93,157,170

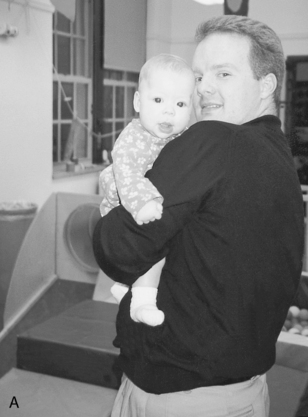

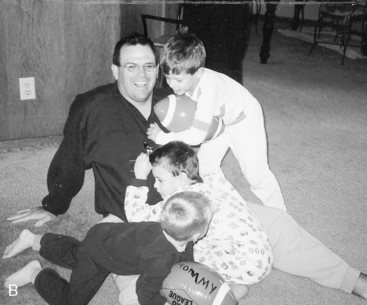

Some researchers have found that fathers can be more at risk for stress than mothers because they may feel isolated and helpless compared with the mother, who is more involved. Young and Roopnarine found that fathers spend about one-third the time caring for their children that mothers do.179 Also, fathers may lack social supports compared with their spouses. Scholars have come to recognize the multidimensional process influencing what fathers do and why they do it.126 They have also noted that fathers are more sensitive than mothers to the influence of the ecology of the family and the attitude of others. Other studies have found that mothers and fathers report similar levels of stress related to a child with disabilities.76,115 Although stress levels were similar,76 mothers attended 80% of the child’s intervention sessions compared with fathers, who attended 33%. The problem that arises from fathers’ inability to attend therapy is that information is often conveyed via the mother. Therapists should identify and use more direct methods of communicating with the father to ensure that information is transmitted accurately and to unburden the mother of the responsibility of transmitting information (Figure 5-3).

FIGURE 5-3 A, Father enjoys holding his child while attending an early intervention program in the evening with his family. B, Playtime with Dad before bed.

A child with disabilities can also affect the relationship between husband and wife. Although there is evidence that a child with disabilities can stress the marital relationship and decrease marital satisfaction, some parents have reported that their marriage was strengthened.134 Differences in marital satisfaction between families of children with disabilities and those of typically developing children tend to be minimal.20 Stress in dealing with the child may bring parents together for problem solving, and they may rely on each other for emotional support and coping. A strong relationship between husband and wife seems to buffer parenting stress. Britner et al. found that mothers who reported high levels of marital satisfaction also reported less parental distress and found their supports and interventions to be more helpful.20

Siblings

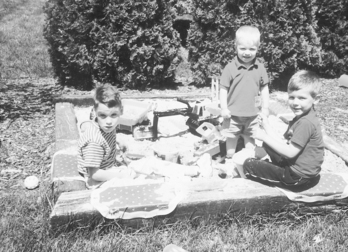

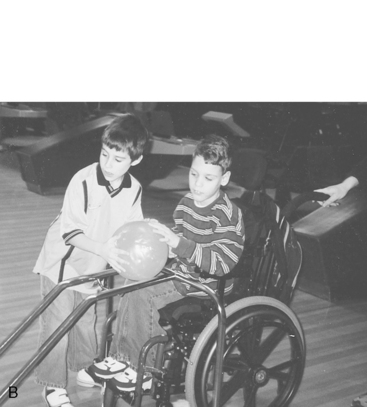

As was suggested in the discussion of the system perspective, family members reciprocally influence one another in a dynamic way. Having a brother or sister with special needs changes the experiences of other children growing up in that family (Figure 5-4). Williams et al. investigated how having a sibling with special needs influences the typically developing brother or sister.178 Using a method that allowed them to track direct and indirect effects (structural equation model), they investigated factors that might influence behavioral problems or the self-esteem of children who had a sibling with either a chronic illness (e.g., cancer, diabetes, or cystic fibrosis) or a developmental disability (e.g., autism, cerebral palsy). These workers considered factors that might influence the typical child’s experiences, such as how much the child understood about the disease, the sibling and his or her attitude, and social support. They also asked the mother about the mood and emotional closeness of the family (family cohesion). The researchers reported that the family’s socioeconomic status (SES) and cohesion and the siblings’ understanding of the disease were related to whether the typically developing sibling had behavioral problems. They also found that when the siblings felt supported, their behavior, mood, and self-esteem were more positive than when they felt unsupported.

FIGURE 5-4 Matthew and his brothers enjoy backyard play. A sandbox is a fail-proof medium that provides equal opportunity for multiple levels of play. Courtesy Jill and Mark McQuaid, Dublin, Ohio.

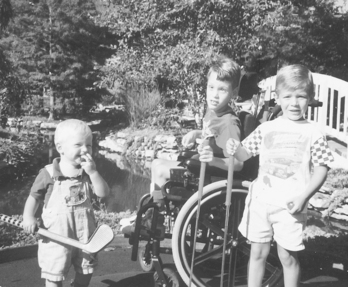

Siblings are an important source of support to each other throughout life. In general, the relationships between children with disabilities and their siblings are strong and positive (Figure 5-5).154 However, the research findings are varied across types of disabilities, sibling place in the family (older or younger), and sibling genders. Conflict among siblings may be more prevalent when a child has a disability such as hyperactivity or behavioral problems. Conflict tends to be less prevalent when a child has Down syndrome or mental retardation.61,81,154

FIGURE 5-5 Although Matthew is the oldest of four boys, his younger brothers already take the initiative to help him participate. A round of miniature golf requires his brothers’ assistance, which does not detract from the fun. Courtesy Jill and Mark McQuaid, Dublin, Ohio.

Often the roles of siblings are asymmetric, with the typically developing child dominating the child with the disability. Siblings without disability generally engage the child with a disability in play activities they can participate in, such as rough-and-tumble play rather than symbolic play. Siblings may be asked to take on caregiving roles, and assuming caregiving roles can have both positive and negative effects.154 Siblings learn to relate and interact in the context of a family. Positive and solid marital systems seem to promote more positive sibling relationships, and marital stress has a deleterious effect on sibling relationships. Rivers and Stoneman studied the effects of marital stress and coping on sibling relationships when one child had autism.134 Using multiple self-report measures of siblings and parents, they found that when marital stress is greater, the sibling relationship is more negative. This study confirmed the importance of examining sibling relationships in the context of the family, recognizing that all family subsystems affect each other.

As occupational therapists promote engagement in a full range of activities as a way of helping a child participate in family life, the inclusion of siblings is an important step in occupation-centered practice. Peer support groups for the typically developing siblings can also be occupation centered. Therapists can develop a recreational program for brothers and sisters of children with whom they work so that the siblings can meet one another and realize that their family is not the only one that faces challenging behaviors. These groups generally participate in structured activities and have open-ended discussions about what it means to have siblings with disabilities. One formalized support group for siblings is Sibshops, a recreational program that addresses needs and concerns through group activities.110 Sibshops’ primary goals for brothers and sisters of children with special needs are to meet their peers, discuss common joys and concerns, learn how others handle common experiences, and learn more about their siblings with special needs. In addition, parents and professionals are given the opportunity to learn more about the experiences of these typical siblings. When possible, siblings should be involved in occupational therapy sessions. They are likely to be the best playmates and can often elicit maximum effort from their brother or sister. In addition, sibling involvement gives the therapeutic activity additional meaning (play), and siblings can act as models for teaching new skills and providing needed support in a natural context.82

Extended Family

In the extended family, the experience of having a child with special needs depends on the meaning family members bring to their relationship with the child. For some grandparents, grandchildren represent a link to the future and an opportunity for vicarious achievement. Researchers find that when children have disabilities, grandparents express both positive and negative feelings and go through a series of adjustments similar to those of the parents.98,137 Many of the negative feelings, such as anger and confusion, appear to decrease with time. However, some never completely disappear. Positive feelings, such as acceptance and a sense of usefulness, increase over time. A grandparent’s educational level and sense of closeness to the child are positively associated with greater involvement with the child. Factors such as the grandparent’s age and health and the distance the grandparent lives from the child do not appear to influence involvement (Figure 5-6). Grandparents learn information about their grandchild’s condition primarily through the child’s parents. However, some seek information from other sources, such as support groups for grandparents of special-needs children. Margetts et al. found that grandparents of children with autism spectrum disorder felt strongly about the caring and support they provided for both their children and grandchildren. These researchers suggested that for professionals to be truly family centered, they need to ask whether the parents want to include the grandparents in the initial assessment of the child.

FIGURE 5-6 Matthew’s grandparents enjoy their time with him and offer important support to his parents. Courtesy Jill and Mark McQuaid, Dublin, Ohio.

Patterson, Garwick, Bennett, and Blum interviewed parents of children with chronic conditions about the behavior of extended family members.130 Family members, such as grandparents, uncles, and aunts of the child, were especially important to fathers and mothers for emotional and practical assistance. When extended family members were not supportive, parents expressed frustration and hurt over their lack of contact. In addition, parents recalled examples of times family members made insensitive comments about the child, ignored the child, or did not want to talk about the child’s disability. Parents of children with behavioral problems reported that extended family members tended to blame the child’s actions on the parents’ inability to discipline correctly.161 Families may be reluctant to ask relatives for assistance, wishing instead that they might volunteer.47 With the consent of the parents, occupational therapists can encourage extended family members to become more involved by offering to share information with them and inviting them to therapy sessions. In this way, therapists can help families build on important social and emotional resources.

FAMILY LIFE CYCLE

Family systems undergo metamorphosis and adapt as family members change. Some transitions can be anticipated with developing children and seem to be tied to age more than ability. For example, normative events in children that require adjustments in families include the birth of a child, starting kindergarten, transitions between schools, leaving high school, and living outside the home. Other changes in the family are not anticipated. Non-normative events may include a grandparent coming to live with the family or a parent accepting a different job in another city. Families that are cohesive and adaptable adjust interactive routines, reorganize daily activities, and return to a sense of “normal” family life. If interactive routines and role designation are too rigidly set, the family may not be able to operate effectively through periods of transition. This is especially true if the family experiences unanticipated, threatening events, such as a job loss or a medical crisis. All families use coping strategies to accommodate periods of transition.

Occupational therapists must understand that all families are unique. Although life-cycle models consist of predictable events, the individuality of each family must be acknowledged. The characteristics and issues at each life stage are highly variable, and each family moves through the stages at different rates. For example, family members may experience and resolve their feelings when they first learn about their child’s diagnosis, or they may take months to “come to grips” with the information.131 In addition, the family may experience cycles of sadness and acceptance later, within and between life stages. Issues that the family seemed to resolve when the child was an infant may occur again when the child reaches school age and an “educational diagnosis” is made or a learning problem is identified. Other life stage–related events, such as the child’s ability to develop friendships when first entering grade school, may become an issue again, such as when the child enters high school.165 Appendix 5-A provides examples of the issues that arise in each of the life stages. Finally, owing to the nature of the family structure, different members of the family may be at different stages at the same time. Therefore, characteristics of the family members and the child’s phase of development must be considered. For example, in a skipped-generation family, grandparents frequently have to deal with changes associated with old age at the same time they are parenting their grandchildren. In other families, parents may be taking care of their elderly parents in addition to caring for a child with special needs. Similarly, a young couple may have more energy and resources to cope with the birth of a child with special needs than does an older couple with four other children participating in school activities.

Early Childhood

Identifying a child as being at risk for health or developmental problems is usually a complicated process. Unless the child is born with medical problems, or with congenital problems in a body structure, or has features that suggest a syndrome, many children are not diagnosed until months, and sometimes years, later. Families that describe their experiences in raising a child with a disability frequently recall their journey by looking back to a period when “something was not right.”40 Families of children with pervasive developmental delays recall a sense that they had to search for a diagnosis with repeated testing and visits to several clinics or evaluation centers. Even parents of a child with an unusual physical complaint, such as joint pain that only occurs at night, might have to persevere in finding the cause when professionals initially determine that the child is only seeking attention. After receiving a diagnosis and ending a period of uncertainty, families hope for a period of stability, but as one educated father commented, “No amount of professional or personal preparation trains you for the reality of chronic illness” (p. 243).63

Parents’ requests for information generally include questions regarding day-to-day childcare, medication management, insurance issues, and support systems available.65

Parents whose first child has special needs do not have the same experiences to draw on as those of families with older children.47 Parents of young children may ask questions such as: “Do you think he can go into a regular classroom” and “Do you think she will be able to live on her own some day” Thoughtful responses to these questions recognize the parents’ need for optimism and hope. However, the responses must be honest and realistic. Even therapists with years of experience and extensive knowledge about disability and development cannot make definitive statements about the future. Long-range predictions about when the child will achieve a certain milestone or level of independence are always speculative. However, parents feel frustrated when they are told that the future cannot be predicted. Lawlor and Mattingly found that families want to be exposed to anticipatory planning.90 Parents want to understand that they have reason to expect their child, despite disabilities, will have a place in society and an opportunity to engage in socially valued occupations during adulthood. Therapists can help parents understand the range of possibilities by telling them about the continuum of services for older children and young adults in the community. Talking with parents of older children with a similar condition or hearing the therapist’s story of a child with the same characteristics provides some insight into the future.42,177 Even without knowing the child’s developmental course, parents start to develop an understanding that services are in place, and they begin to create new stories about their child’s future.

Given information about the system, their rights, and the resources available to them in their communities, parents can solve problems and independently access needed services. The caregiving routines of parents whose young child has a disability are not particularly different from those of all parents of young children. At this time in the child’s life, the parent’s work consists of managing the child’s play environment and introducing new, developmentally appropriate objects and materials. The parent ensures safety and may adjust or arrange the play environment so that the infant can access objects of interest. Feeding, diapering, bathing, and daily care are also natural parenting activities at this time. Only when infants and young children have serious medical conditions or behavioral problems are daily occupations significantly altered.

When children are medically unstable but still at home, a family may have home-based nursing for extended periods (i.e., months to several years). Murphy described the stress created by the constant presence of nurses and professional care providers in the home.113 Role ambiguity often results when parents feel that they must take on unpaid nursing work and nurses take on parenting roles. Parents also report stress from a lack of privacy and the continual feeling that they are “on duty.” Parents of medically fragile children must make tremendous accommodations, which should elicit high levels of sensitivity and responsiveness from professionals. For example, when parents have a medically unstable infant and around-the-clock, in-home nursing care, services such as respite become a priority.

School Age

When a child enters school, all families are excited about the new opportunities for learning and the child’s new demonstration of independence. However, school entry is not always a positive event for families of children with disabilities. Families that experienced early intervention services may be disappointed to find fewer family services and less family support offered by the school. Typically, parents are not encouraged to attend classes or school-based therapy sessions. Many parents view the transition to school as an opportunity to be less involved and a sign of their child’s maturation. To ease the transition from home to school, the parents of children with special needs should learn about the school’s programs, schedules, rules, and policies (Figure 5-7).

FIGURE 5-7 Matthew has an aide at school who supports his participation in both academic and nonacademic activities. Courtesy Jill and Mark McQuaid, Dublin, Ohio.

For children with mild learning disabilities, entry into school may be the first time that the gap between a child’s performance and teachers’ expectations for his or her performance is identified. Therefore, this may also be the first time that parents receive information that their child has special needs. When this is the case, parents can experience surprise, disbelief, or relief. School age is a time when children with disabilities may first discover that they have differences. How they make the adjustment to this information depends on the knowledge and sensitivity of the adults and children around them.

To the school-aged child, making friends and maintaining friendships become critically important. Some parents report concern if their children appear lonely, isolated, and friendless. Turnbull and Ruef found that children with behavioral problems frequently have no friends, leaving the parents with the additional responsibility of creating and supervising play opportunities with other children.161 Teachers and therapists can use different strategies to promote friendships in inclusive environments. Typically developing peers can take turns being a child’s “special buddy,” and they can offer assistance with projects or tutoring. In situations in which social stigma is an issue, peer relations can be promoted by explaining the disability to the other children and by designing classroom activities that promote cooperation and positive interaction.

Adolescence

Adolescence is a challenging and potentially stressful time for all families, as the development of self-identity, sexuality, and expectations of emotional and economic autonomy herald the transition to adulthood. These issues may pose additional challenges in the lives of children with disabilities as they maneuver through adolescence. Parents need to prepare the young person to handle his or her growing social, financial, and sexual needs, as well as how to avoid substance abuse. (See the review of high-risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic illness by Valencia and Cromer.169) In certain cases, parents face decisions about their child’s use of birth control and protection from sexually transmitted diseases.45 With adolescence, new concerns about a son’s or daughter’s vulnerability increase as that child ventures further into the community and beyond. These decisions will vary significantly depending on the nature of the disability: cognitive, physical, social, visible, or not. They will also be mediated by financial opportunities or constraints.

Although the child usually is well accepted by family members, the social stigma incurred from peers and others may increase during adolescence. As one mother said, “The community accepts our children much more easily when they are small and cute. Babyish mannerisms are no longer acceptable … [Our son] has had real problems with his social relationships. He simply does not know how to initiate a friendship. He has difficulty maintaining a sensible conversation with his peers. He doesn’t handle teasing well, so he is teased unmercifully” (p. 90).4

The cute child with unusual behaviors may become a not-so-cute adolescent with socially unacceptable behaviors. As one parent explained why her son was not invited to a holiday party, “Everyone in the family was invited except Billy. I thought it must be an oversight, but the friend later explained apologetically, ‘I thought Billy’s presence might make the other guests uncomfortable.’ This kind of attitude is difficult to accept, particularly when he had been included very successfully in a similar party. I find myself crying at the unfairness” (p. 16).140

Other parents have reported difficulty in caring for their child’s growing physical needs. As the child reaches adulthood, parents who are reaching middle age may feel their strength and energy declining. As one parent put it,

The sapping of energy occurs gradually. The isolation it imposes does, too. As I work professionally with young mothers, I see them coping energetically with the demands of everyday life. They are good parents, caring ones, doing everything possible to help their child [with a disability] reach full potential, sometimes doing more than they have to; and if they have other children, they are doing the same for them. Most of these mothers even get out, see friends, attend meetings, volunteer in the community, and do all the things their friends and families expect them to do. All this is at least possible when one’s child is little, although it demands enormous energy. But to look at the mothers of children who have turned into teenagers is to see the beginnings of the ravages. Their lifestyle is changing. They go out less, see fewer people, do less for their children. They are stripping their living to the essentials (p. 144).112

Adolescence is the time when most parents must learn to let their children make their way in the world. For parents of children with disabilities, this time may require additional emotional support and financial resources. Magill-Evans, Wiart, Darrah, and Kratochvil conducted a small qualitative study with parents of adolescents with physical disabilities and some of the adolescents themselves that documented the multifaceted needs of each family in balancing the connection of the youth and the parent between the old way of relating and the new acceptance of the autonomy needs of the young adult.97 They found that both the young person and the parent had issues to be dealt with at this time, ranging from the need of each for emotional support during the transition to the need for financial resources to meet the physical or educational requirements of the young person for care from nonfamily members. Gender differences have also been found to have significant impact during the transition to adulthood. In one survey study of adolescents receiving special education services, the expectations and opportunities regarding work and family for males were perceived to be greater, even though the female respondents placed greater emphasis on having children and going to college. In addition, while both genders were concerned about obtaining health insurance, more of the female respondents rated this as a very important goal.133 As with all facets of the life cycle, this is a time for a sensitive, collaborative approach between families and service providers so that the right supports and resources are offered to each family.

FAMILY RESOURCES AND THE CHILD WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Having a child with special needs does not eliminate any of the functions of a family. That is, through their activities, families continue to provide a cultural and psychosocial foundation and guide their children’s experiences in activities that will lead to optimal health and participation in the larger community. Understanding how families make choices in light of finite resources and their vision of children’s futures puts some of these decisions families make about daily activities and what they want to work on in a different light.74 For a period, especially when a problem is recently diagnosed or when medical treatment is needed, family resources (e.g., time, money, and emotional energy) may be directed primarily to the needs of the child.108 For example, a mother who has a full-time job to help pay medical and therapy bills and spends four hours a day feeding her medically fragile child has limited time and emotional energy to devote to helping another child with homework or to sharing in recreational activities. Over time, this allocation of resources can have negative implications for family members, and if the feeding problems are chronic, other choices may need to be made.

Financial Resources

Having a child with special needs has implications for family economics. Parents with children who have disabilities have many hidden and ongoing expenses. When children are hospitalized, many expenses (e.g., days out of work, childcare for siblings, transportation, meals, motel rooms) are incurred, in addition to costs not covered by insurance.123 Mothers on welfare reported that they faced multiple barriers.94 Although they wanted to become self-sufficient, they found that employment seemed like a distant dream as they struggled with transportation and finding childcare, particularly for older children.173 Jinnah and Stoneman offer an excellent review of literature and qualitative study on parents’ experiences with finding childcare for their school-age children.70 Part of their recommendations address the training needs of providers of childcare, as well as the information needs of parents regarding the accessibility requirements of childcare centers under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Although financial problems create added stress, therapists are often reluctant to discuss finances, especially costs associated with their own services. In a sample of mothers of children with cerebral palsy, Nastro found that insurance coverage was inadequate to meet the families’ needs. As one mother reported, “Each piece of equipment has a big price tag. Even the smallest piece has a couple-hundred-dollar price tag. Most insurance companies do not cover it. Medicaid does not cover everything” (p. 52).116

Also, many insurance plans have caps on the number of therapy visits allowed per year. Therefore, parents must cut back on services or pay for sessions by finding a way to save somewhere else. Children who require extensive medical treatment can bring economic devastation to a family, especially when insurance coverage is inadequate.80,124

Another challenge to financial resources occurs when a parent decides to remain unemployed so that he or she has time to provide extra caregiving. Multiple studies have documented that a parent may need to work fewer hours, if at all, to care for the child.10,132 With one spouse unable to take on paid employment, these households are at higher risk for problems associated with low income. Financial strain is increased in single-parent homes. Case-Smith found that mothers of children with medical conditions left employment because of the frequency of their children’s illness.23 These children needed specialized medical care (i.e., nursing care) that prohibited their attending community childcare centers. The need to stay home with a child who has multiple medical needs and frequent illness coupled with lack of community childcare for such a child can become a particularly difficult situation for parents to manage. Part of the essence of family-centered care is addressing such needs in a family.71

Human Resources

The human resources important to a family in raising children are education, practical knowledge, and problem-solving ability. An understanding of the basis of the child’s problems and of possible adaptations is a powerful resource in helping families establish effective patterns of daily activities. As a parent, Marci Greene observed that a comprehensive parent–professional partnership should include ongoing sharing of information with parents.48 Initially, most parents want additional information about their children’s conditions and about accessing services.82 This is followed by needing information about potential complications, and how to care for their child’s physical and psychological needs on a daily basis.65 However, parents appreciate dialog with professionals beyond informational topics such as the development of feeding skills or behavioral management. Parents want professionals to share conceptual knowledge as well.48 The timing of parents’ ability to use this knowledge and engage in home programs varies appreciably from the time of initial diagnosis of disability through adjustment to their situation, and in qualitative studies having the need for information met is often deemed inadequate.65,131

Families who are coping with stress have reported that “the ability to build on personal experience and expertise” (p. 261) is an essential coping strategy.47 Parents can develop this knowledge through parent-to-parent groups in which families can share strategies with other families who have similar types of issues.40,177 For therapists, listening to parents and individualizing the information, as well as connecting family members to other resources, helps build the parents’ personal resources. The CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research has developed a formal, individualized information Keeping It Together™ (KIT) for parents, which has been shown to increase parent “perceptions of their ability and self-confidence in getting, giving and using information to assist their child with a disability” (p. 498).153 Therapists must remember that many parents are the experts on their own children and often have extensive information or stories to share about what works for them.11

Time Resources

Daily and weekly activities, by their very definition, require time investment, and every family at one time or another experiences stress because there are too many things to be done and not enough time. Children with disabilities often depend on caregivers longer than typically developing children, and the extra daily care or supervision needed can extend for many years.30,40,97 The amount of time spent in shared activities around caregiving can be wearing and frustrating and can reduce the family’s time for recreation and social gatherings. In a study of more than 200 families of children with Down syndrome, mothers spent three times as much time in childcare as mothers of typically developing children.10 The fathers of children with Down syndrome spent twice as much time in childcare as fathers of typically developing children. One commonly used coping strategy of family caregivers is to organize the day into well-established routines.47 Helitzer and colleagues found that mothers of children with disabilities reported that they used “structure, routine, and organized time management as a way to maintain a sense of control” (p. 28).57 However, their busy, structured lives often were disrupted by crises, such as trips to the hospital or urgent care department and, as a result, the mothers felt they were “living on the edge” and that every disruption in their routines was experienced as a crisis.

Crowe found that mothers of children with multiple disabilities spent significantly more time in child care activities and less time in socialization than mothers of typical children.29 In a qualitative study of parents of children with chronic medical conditions and disabilities, parents reported that they had round-the-clock responsibilities in administering medical procedures and performing caregiving tasks.23 They described the challenges of “always being there” to care for their child’s extraordinary medical needs and to engage their very dependent child in developmentally appropriate activities. These parents, whose children were often ill and even hospitalized, were always “on call” and often had to cancel activities outside the home when the child was ill.

Service providers can be a source of threat to the family’s time and emotional resources. Providers seeking to implement family-centered practice often expect parents to take on responsibility for implementing therapy.93,96 Greene described how her family “experienced the burden of home programming” as occupational therapists, physical therapists, and speech and language pathologists made separate recommendations, each requiring a chunk of the day.93 These home assignments became a source of guilt and marital difficulty as the family struggled to meet the needs both of their daughter and of her typically developing sibling. Less experienced therapists, in their enthusiasm to help, often neglect to consider the family’s time commitments when offering suggestions.

Emotional Energy Resources

Families of children with disabilities may experience special forms of stress, social isolation, and less psychological well-being than families with typically developing children.9,32,102 The idea that parents of children with disabilities experience recurrent grief is pervasive in the literature, yet disputed.41,166 Fox et al. conducted a qualitative investigation to understand how children with developmental delays and behavioral problems influenced the family’s lifestyle.40 Their parents suggested that dealing with the child’s needs required a lot of emotional energy from the different family members. One theme—“It’s a 24-hour, 7-day-a-week involvement”—was supported by stories of frustration from responding to challenging behaviors and applying parenting practices that would meet the needs of their children. Parents reported that individuals who offered “a shoulder to lean on” and professional assistance, encouragement, and information were particularly helpful.

Studies have shown that parents of children with disabilities may experience anxiety and depression.55,120 Mothers appear more vulnerable than fathers. In a large comparison study of families of children with autism, developmental disability, or without disabilities, Olsson and Hwang found that mothers of children with autism were more depressed than mothers of children with mental retardation and that both groups were more depressed than mothers of children without disabilities. The fathers in these families did not exhibit more depression than fathers of typical children. Mothers’ self-competence may be more related to the parenting role than that of fathers, and mothers may be more vulnerable when stressful difficulties arise in the parenting domain. Hastings, investigating levels of stress, depression, and anxiety in a cohort of 18 couples with children with autism, found that mothers and fathers felt similar levels of stress; however, mothers were more anxious.55 Mothers may feel more responsibility for the child55 and may take on a larger part of the extra care that a child with disabilities requires.120

When children have chronic medical problems that require round-the-clock use of technology, parents often find themselves exhausted and sleep deprived. Some of the consequences for parents whose children require routine medical procedures are anxiety and depression because of the risks inherent in the administration of the medical procedures. When parents must administer medical procedures beyond the typical parent–child activities of nurturance, caregiving, and play, they appear to experience stress and anxiety. In addition, they often do not have the time and resources to access energizing and relaxing activities, such as socializing and recreation.9,80

Stress level in families with children with chronic diseases or conditions has been found to have a strong relationship with family income and family function, with lower income associated with higher stress, especially as the children become adolescents.9 Parents with limited resources, whether financial, educational, emotional, or a combination, are at higher risk of experiencing parental stress, which may lead to abusing or neglecting children with disabilities.150 The added needs of children with chronic health issues or behavioral or intellectual limitations can push the low-resource parent over the edge of reason to a point where maltreatment of the child is the consequence.58

SOURCES OF DIVERSITY IN FAMILIES

Families with children who need occupational therapy services come from many different backgrounds and in a variety of forms, and therapists working with these children have the rewarding opportunity to learn from their families. Therapists must find a balance between focusing on the similarities and appreciating the differences among families.1 Because individuals are inclined to view the world through their own cultural model and to use personal experiences as a point of reference, it takes professional commitment to become skilled at working with a variety of different families.

Family researchers and service providers have focused on understanding how a family’s culture and traditions affect child-rearing practices and how these might be adaptive, strengthening a family or bringing about positive developmental outcomes.83 Families have patterns of different characteristics (e.g., family structure, family income, having a family member with a disability) and the ecology in which families’ function varies (e.g., religious opportunity, crime rate in the neighborhood, period in history). Therefore, generalizations of research findings about diverse family groups are rarely accurate, and sensitivity to the unique differences of each family is always needed. Three sources of family diversity discussed next are the family’s ethnic background, family structure, and socioeconomic status. A fourth section considers differences in parenting styles and practices.

Ethnic Background

Ethnicity is a term used to describe a common nationality or language shared by certain groups of families. It tends to be a broad concept, and heterogeneity among families within groups described as Latino, African American, Anglo-American, or Asian should be anticipated. Furthermore, people may identify themselves as belonging to more than one ethnic group, making it harder to use the concept to guide the way the therapist works with families. Coll and Pachter offer two reasons for retaining ethnicity as an important variable when working with families raising children.27 First, families that are not part of the dominant ethnic group experience a discontinuity between their cultural models and the majority culture that shapes the social institutions. Thus a cultural as well as a language gap may exist between health systems and educational programs and the families of minority ethnic groups.2 In addition, as the proportion of ethnic groups grows in the United States, the sons and daughters of these groups make up a larger proportion of the overall population of children in this country. Occupational therapists who serve children with special needs can anticipate working with an ever-growing, ethnically diverse group of families. The influence of ethnic background on the ways a family fulfills its functions and raises its children is a complex topic that is merely introduced here. Resources on the Evolve website provide further information.

Ethnic groups share cultural practices that can determine who has the authority to allocate family resources and a value system that sets priorities for family routines and special events. Families in an ethnic group may have similar daily activities, ways of interacting, and ways of thinking about events, and may find similar meaning in their routines, traditions, and celebrations. Differences among ethnic groups are expressed in gender role expectations, child-rearing practices, and expectations at certain ages, as well as in definitions of health and views of disability. Cultural practices are not static traits; rather, they change when members of the group adapt to new situations.53

Although every family wants their children to be successful members of the community, their vision of what this entails varies among different ethnic groups and influences how children spend their time and what is expected of them.88 Carlson and Harwood studied the structure and control Anglo-American and Puerto Rican mothers asserted over their infants during ADLs.22 The researchers observed mothers in their daily routines and found that Puerto Rican mothers controlled their infants’ behaviors more than the Anglo-American mothers, who tolerated more off-task behaviors. Carlson and Harwood pointed out that Puerto Rican parents are guided by the anticipation that their children will join a Puerto Rican community that values respectful cooperation. The Anglo-American willingness to follow the child’s lead is compatible with valuing individual autonomy. Without insight into ethnic differences, a therapist watching parent–child interaction may mistakenly interpret a Puerto Rican mother’s physical control and effort to divert a child’s attention to the needs of others as intrusive and insensitive to the toddler’s sense of identity and self-efficacy. Therapists avoid this type of error by understanding what a parent hopes to achieve before formulating an opinion about the appropriateness of a family’s interactive routines.

The influx of recent immigrants expands the diversity within ethnic groups that therapists will encounter. Within a community, one family may have members who have been in a country for generations, and the family next door may have recently relocated to the country. Migration affects the family and how it functions at multiple levels.37 First, relocation to another country frequently includes a series of separations and reunions of children and family members. Suarez-Orozco, Todorova, and Louie found that 85% of the 385 youths in their sample of recent immigrants had been separated from a parent and nearly half had lived apart from both of their parents during the process of family migration.155 Although the length of separation varied, it was not unusual for a child to have been apart from the father for 2 years or longer. In some families, the tradition of having a child live with a grandparent or other relative may buffer the initial separation and help reduce the stress. Yet when the children are brought into the United States to join their immigrant parents, they must leave behind a caregiver and familiar community. Researchers found that reunification could be protracted, because families may not have been able to pay for travel or housing for all family members, meaning that people arrived in stages, months or years apart. In addition, when both parents immigrated ahead of their children, it was not unusual for the children subsequently brought into the country to have to adjust to living not only with their parents again but also possibly with younger siblings born in the new country. Therapists working with immigrant families need to be sensitive to the possibility of family friction, depression, and a sense of uncertainty among family members.

For each immigrant family, the process of acculturation varies; this is the process of selectively blending their traditions in how things are done, what activities are important, and interactive styles with the cultural practices of the majority group.37 Parenting practices might insulate children from exposure to the language, ways, and values of the majority culture until the children go to school. For example, enrolling children in child care programs may seem the equivalent of child abandonment in some cultures, and families may bring a grandparent with them as part of the immigration process so that both parents can find paid employment. This may mean that children entering school have had few experiences beyond their home environment. In school, surrounded by new peers, the children’s acculturation process is influenced, creating conflict among family members.27 Unfortunately, feeling disconnected from home or discriminated against at school leads some youths to drop out of school as a way to ease the tension.53 When this situation includes a child with disabilities, the occupational therapist has more to consider in addition to the specific needs of the child.2

Family Structure

Family features, such as the presence of children in the household, marital status, sexual orientation, and age/generation, are factors described as the family structure.1 It is important to remember in working with families that acceptance of diversity within the family structure and family subsystems is necessary to be effective.

Family structure in combination with its cultural model influences how the family organizes itself to fulfill essential roles, such as caregiving of dependent family members or allocation of family resources. The idea that there is a best family structure in which children are raised is a myth.174 For example, single-parent families have been portrayed as dysfunctional and as leaving children more vulnerable to having problems3; yet single parents have also been found to raise competent, well-adjusted children.114 One third of the births in the United States are to unmarried women.117 The majority of single-parent households are headed by women; however, the number of fathers who are single parents has increased.168 The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study is an attempt to discard myths and replace them with evidence that will guide intervention and policy making to support low-resource families.105 Some of their findings demonstrate that “Unwed parents are committed to each other and to their children at the time of birth…Most unmarried mothers are healthy and bear healthy children” (p. 3).105

Larson sampled the activities and emotions during activities of employed mothers in two-parent or single-parent homes of adolescents and found that the stereotype of the single-parent home was not necessarily the rule.87 Single mothers in his study had less stressed, more flexible routines after a day at work, and friendlier relationships with their teenagers than did their counterparts in two-parent homes. Mothers with a husband reported more hassles trying to make and serve dinner by a designated dinnertime and experienced housework as more unpleasant. Larson speculates that the negotiation of responsibilities and trying to live up to expectations of being a “wife” in a two-parent home contributed to these differences. Clearly, every family structure has advantages and risk factors.87

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual families reflect one variation of family structure that therapists encounter. Children may be the products of a parent’s previous heterosexual relationship or may be born or adopted into families headed by adults who are gay, lesbian, or bisexual.127 Because parents do not want to expose their children to the prejudice of homophobia, many are reluctant to be identified, and estimates of the number of parents who are not heterosexual range from 1% to 12% of families.151 Many of the issues and needs of all parents are expressed by gay, lesbian, and bisexual parents.125

Because sexual orientation has been the basis for judicial decisions that have denied people parenting rights, recent studies have investigated the issue of whether the sexual orientation of the parent affects the child’s behaviors or influences the child’s sexual orientation. Studies comparing the psychological adjustment and school performance of children being raised by lesbian or gay parents to those of children with heterosexual parents have generally found no differences.127

A final source of stress, divorce, the way many single-parent families are formed, can cause disruption that alters household routines, traditions, and celebrations. Sometimes the stress between the marital partners leads to impaired occupational functioning of the children and the divorce may come as a relief. Factors that contribute to positive developmental outcomes for children after couples break up include the parents’ psychological well-being, economic resources, whether the family is part of a larger kinship network, and how parents navigate the separation and dissolution process. For example, Greene, Anderson, Hetherington, Forgatch, and DeGarmo reported contradictory findings regarding how well children adjust after their parents’ divorce.49 Initially, parenting practices were erratic, and the parent–child relationship, especially between custodial mothers and young sons, could be stormy. Yet two years after a divorce, many of the problems had diminished; therefore, some of the consequences of divorce depend on where in the adjustment process researchers conduct their study. Anderson argued that the best way to strengthen single-parent families was to empower parents by recognizing their strengths and encouraging them to reestablish routines.5 The therapist can be supportive by acknowledging that these parents face considerable challenges in raising children alone and by aiding the parent in identifying resources such as friends, extended family, religious groups, and other single parents.

When birth parents are unable or unavailable to care for children, kinship care is a way to preserve family ties that might be lost if children are placed in foster homes.75 Households in which grandparents are raising their grandchildren are examples of those providing kinship care and are a growing source of differences between families. These families, primarily headed by middle-aged or older women and disproportionately by women of color, are often formed after adverse events, such as child neglect or abandonment, maternal substance abuse, or incarceration or death of the parents.72,75,85 Much of the research on grandparents raising their children’s children explores the issue of caregiver stress. Evidence from both qualitative and quantitative studies suggests that grandparents caring for their grandchildren (or great-grandchildren) find it both rewarding and challenging.8,75 Grandparents reported satisfaction in being able to “be there” for the child or children and reported that they have had to learn new parenting skills in response to the new generation. However, they also experienced parenting stress, which was exacerbated when they lacked social support, had limited financial resources, or were in poor health. When a child is reported to have behavioral or health problems, the caregiving demands increase the grandparents’ sense of emotional distress.56

During their childhood, many children experience changes in the family structure. Unwed mothers may marry, or parents in a family may divorce and later one or both may remarry. A child may transition from a two- to a three-generation family when an aging grandparent moves into the home. Therapists should talk with family members in an inclusive manner that does not suggest an assumed family structure. Asking a parent or child, “Can you tell me about your family” does not suggest any expectations about who is in a family and helps family members openly express their definition of who is in their family.

Socioeconomic Status

The influence of the family’s SES on children’s occupations and development is complex.62 SES reflects a composite of different factors, including the social prestige of family members, the educational attainment of the parents, and the family income. These factors influence each other and have various implications for how a family fulfills its functions, by influencing the degree of access families have to activities and experiences for their children. Education influences parenting practices by affecting how an adult incorporates new ideas about a healthy life style and child development into these practices. Factors that influence employment, such as a below-average education, inability to speak English, or disability of a family member, leave families more vulnerable as job opportunities come or go. When employment is found, the job may not pay enough to meet the family’s needs, leaving the family with no resources if unexpected events occur.

Researchers have demonstrated that low income or limited education is associated with differences in the quality of parents’ interaction with their children.62,135 In these circumstances, parents may not be as responsive, addressing the child less often, providing fewer learning opportunities, and not engaging in an interactive teaching process. Parish and Cloud present a compelling review of the literature on the factors that lead children with disabilities to be more likely to live in poverty.124 These factors include the increased cost of raising such a child and the decreased ability of their mothers to be employed, because of both the needs of the child and the lack of available child care. A recent study in England found the incidence of very preterm birth was much greater among mothers of lower SES, and preterm birth raises risk factors for the child.148 Suggestions for working with families with low SES are addressed later in the chapter.

Therapists need sensitivity and skill to work with families across the SES continuum. Although this factor has not yet been addressed in the professional literature, having higher SES clearly affords additional opportunities, time, and expectations of parents for those experiences they desire for their children. The concept of “helicopter parents” who hover over every aspect of their child’s life tends to extend to their children with special needs. Therapists must draw on their many skills in assisting these parents to find balance between what can be done through direct service, what they can do themselves, and how to allow a child space in which to be a “typical” child.

Parenting Style and Practices

The individual interactive style and parenting practices of an adult raising a child are additional factors that must be considered in gaining an understanding of the diversity of families. Steinberg and Silk distinguish between parenting style, the emotional climate between parent and child, and parenting practices, goal-directed activities parents do in raising their children.152 For example, two parents may believe that if they want their children to do well in school, it is their responsibility to spend time with the children reviewing their homework (a parenting practice). However, the interpersonal interactions while they engage in this shared activity (parenting style) can be distinctly different. One parent may discuss the work and help the child find solutions to problems, whereas the other parent may feel he has the emotional energy only to point out errors. There is no test or license for parenting in this country. During the time of extended families, there was mentorship and modeling for parenting practices. In today’s nuclear families, stresses run higher and skills may be lacking. When work separates the family, or as the dysfunctional practices of previous generations come to play in the current generation, there is great need to help parents learn parenting skills. Some individual professionals and disciplines, often State Extension Services, are creating programs to teach parenting skills. This is an area in which the holistic occupational therapy knowledge base and framework would prove quite beneficial.

A well-adapted child develops as a result of from complex interactions between parenting style and practice. Regardless of ethnic background, poverty status, and parenting practices, a parenting style that is warm, responsive, and positive and that provides structure and learning opportunities is associated with children who rank higher on many measures of social and cognitive development.6,152

Dialog between parents and therapists does not always go smoothly, and the collaborative nature of the relationship is sometimes lost if the parent and therapist hold different ideas about parenting style or parenting practices. This tension increases if the parent worries about the therapist’s disapproval.91 The professional cannot assume greater knowledge than the parent about what the child needs to be able to do or about the interactive style that best accompanies shared activities (Research Note 5-1). Therapists can be supportive and can empower parents by working with them so that family resources such as time and emotional energy are available when shared activities occur.

AN ECOLOGIC PERSPECTIVE