Early Intervention

1 Explain family-centered early intervention philosophy and principles.

2 Define the components of an individualized family service plan (IFSP).

3 Explain models of evaluation, and describe specific assessments.

4 Describe developmentally appropriate and family-centered intervention approaches.

5 Define areas of emphasis in occupational therapy.

6 Explain strategies and activities used by occupational therapists in working with infants and children.

7 Describe the early intervention legislation and program regulations.

WHAT IS EARLY INTERVENTION?

The term early intervention connotes different meanings to different professionals. In this chapter, early refers to the critical period of a child’s development between birth and 3 years of age. Intervention refers to program implementation designed to maintain or enhance the child’s development in natural environments and as a member of a family. Early intervention describes services for children from birth to 3 years of age who have an established risk, have a developmental delay, or are considered to be environmentally or biologically at risk. The goal of early intervention is “to prevent or minimize the physical, cognitive, emotional, and resource limitations of young children disadvantaged by biologic or environmental risk factors” (p. 11).2

Legislation Related to Early Intervention

The 1980s brought widespread acceptance and support for family-centered care for children with special needs.62 Family-centered care is based on the principle that an infant is dependent on his or her parents and other family members for daily care and meeting his or her physical and emotional needs. At the same time, the birth of an infant with special health care needs affects the entire family emotionally, socially, and economically. In 1986, amendments to the Education of the Handicapped Act (EHA) established incentives for states to develop systems of coordinated family-centered care for infants with disabilities. These incentives were strengthened in 1990, when the EHA was further amended and retitled the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).36 Through Part C of IDEA, all children from birth through 2 years of age who have developmental delays are entitled to services. Revisions to IDEA were made again in 1997 and 2004; the newest version is P.L. 108-446, or the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004.

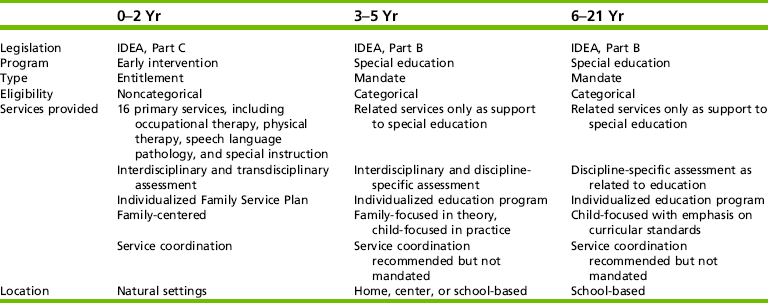

Part C of IDEA delineates the policies and regulations that participating states must follow in establishing early intervention services and systems. Table 23-1 summarizes the differences between Part C, which defines early intervention services for children between birth and 3 years of age, and Part B, which defines school programs for eligible students between 3 and 21 years of age (see Chapter 24). Part C is an entitlement program, and Part B defines mandated services. An entitlement simply acknowledges one’s rights to something; a mandate establishes programs and services that are obligatory by law.

The purpose of Part C of IDEA is to give each state support in maintaining and implementing comprehensive, coordinated, multidisciplinary, interagency systems of early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families. A description of Part C regulations can be found at the U.S. Department of Education website (http://idea.ed.gov/).

Occupational Therapy Services in Early Intervention Systems

Part C of IDEA considers occupational therapy to be a “primary service” for eligible infants and toddlers from birth through 2 years of age who qualify for early intervention services. As a primary service, occupational therapy can be provided as the only service a child receives or in addition to other early intervention services. By its legal definition, occupational therapy includes services to address the functional needs of the child related to adaptive development; adaptive behavior and play; and sensory, motor, and postural development. It includes adaptation of the environment and selection, design, and fabrication of assistive and orthotic devices to facilitate development and promote the acquisition of functional skills. The therapist designs these services to prevent or minimize the influence of initial or future impairment, delay in development, or loss of functional ability.

As described in the following sections, occupational therapists provide early intervention services as part of a team, coach team members and families to support occupational therapy interventions, use a family-centered approach that respects cultural differences, consult with families and children, and provide services in natural environments.

CURRENT PRACTICE IN EARLY INTERVENTION

The early intervention system recognizes that families can be and often are knowledgeable consumers and effective change agents for the child. It also acknowledges that families have specific needs related to a child with disabilities and that families may be the recipients of services.45,67 The early intervention team includes not only the family but also professionals who help each family identify its unique resources, priorities, and concerns. The team then identifies outcomes and goals that enable the family to function more effectively and help the child as a member of the family unit.41

The term family-centered encompasses several aspects: Importance is placed on family strengths, not deficits; families deserve to have control and make choices regarding the care their child receives; and families and providers work together to ensure provision of optimal early intervention services.16 Within a family-centered model, occupational therapists develop goals collaboratively with parents or primary caregivers. Using a family systems perspective, the therapist recognizes the influence and interrelationships of the family within various systems, such as extended family, neighborhood, and early intervention programs. By thinking broadly about families and their subsystems, the therapist can help parents communicate their concerns and identify their priorities for the child.

Families are both participants in and consumers of early intervention services. Traditionally, occupational therapists provided early intervention services with a medical orientation. That is, occupational therapy was provided in a clinic or center, and sessions usually were conducted one-on-one with the therapist and child or in a small group with peers who were also receiving early intervention services. With the changes to IDEA 1997, which required services to be provided in the natural environment, occupational therapists had to expand their thinking about early intervention. Service provision now occurs primarily in the home or other community-based settings and families have a greater role in carrying out therapeutic activities. The nature and extent of family involvement may vary and will depend on family needs, values, lifestyles, and variables within the structure of the early intervention program itself. The degree of family involvement may fluctuate and change in response to external or internal factors that affect family functioning and coping. Some examples are degree of acceptance of the child’s disability, job status of one or both parents, a new infant in the family, and changes in the family’s support networks, such as grandparents, friends, or church groups.

To provide appropriate intervention within the family-centered model, the occupational therapist must be aware of and respect differences in beliefs and values based on culture. “Perhaps no set of programs or services interacts with cultural views and values more than early intervention because of the focus on the very young child with a disability and the family” (p. 116).29 The therapist who provides intervention in the home has an intimate view of such things as customs, eating habits, and child-rearing practices that may vary among cultures. The family’s beliefs and views of disability and its cause, their view of the health care system, and their sources of medical information affect their attitude toward early intervention.70 Based on individual cultural backgrounds, the family may view the therapist as either a helper or one who interferes. Research suggests that early intervention providers may not develop individualized family service plan (IFSP) goals that consider cultural diversity (e.g., family income, location of residence).56 Given the importance of the IFSP in directing program implementation, this finding indicates that early intervention service providers need to make certain they include all family-identified priorities, not just those that relate to child development (see Box 23-1).

Many of the areas in which occupational therapists provide intervention and suggestions involve caregiving and are closely tied to values and beliefs about parenting and cultural views of children. Practices regarding feeding, toileting, and bathing may vary among cultures. The therapist is urged to evaluate various health beliefs to determine whether the effects are beneficial, harmless, harmful, or uncertain before making recommendations for change.30

Occupational therapists must be sensitive to the multiple factors that affect family involvement. It may be tempting to label a family as “difficult” or “noncompliant”; however, families of children with disabilities may be under a great deal of stress and may be doing their best at any particular time.33 For example, a parent who is homeless or jobless may not be concerned about occupational therapy for the child. Another parent may believe that certain skills or goals are more important than those identified by the occupational therapist. Family priorities need to be respected.

Building an ongoing relationship with families will enhance the early intervention process. Effective listening and interviewing skills are essential, as is the ability to communicate with sensitivity the therapist’s own concerns about the child’s occupations. Families who have children with special needs highly value services in which professionals provide clear, understandable, complete information; demonstrate respect for the child and family; provide emotional support; and provide expert, skillful intervention.57 Box 23-2 lists principles of family-centered intervention.

Partnering with Professionals

The success of an early intervention program depends largely on the integration of the child’s individual program components into a comprehensive system by a cooperative team of professionals. Teamwork is critical because of the interrelated nature of the problems of the developing child and the need for skills and resources from many professionals to meet the needs of the child and family. Occupational therapists working with infants and toddlers are early interventionists who have both specialized knowledge of childhood occupations and generalized knowledge regarding young children with special needs. The emphasis of intervention should be the child within the family unit, rather than the child alone, and intervention should be carried out through collaboration among all professionals involved.

The occupational therapist may participate in various service delivery models. Direct, individual, child-centered services often are not the most appropriate in early intervention, and many programs provide services using a consultative model instead.49 Role release represents a common practice in early intervention using consultation. In role release, one professional, sometimes called the primary service provider, may be trained to take over functions that traditionally have been performed by another professional (Figure 23-1).5,48,55 Optimally, role release should be practiced as part of a transdisciplinary team model, where frequent collaboration among team members is supported.46 By ensuring regular face-to-face meetings, team members may build relationships characterized by mutual trust and respect, thus decreasing potential feelings of ownership over particular therapeutic approaches. Limited contact among team members may result in difficulties in implementing role release and ultimately inadequate services for children and families. Coaching, a practice used in both direct and consultative early intervention, has the potential to support role release and is discussed later in the chapter.

FIGURE 23-1 A music therapist helps children enhance their body awareness, a goal that is a primary responsibility of the occupational therapist.

Opportunities for participating in collaborative activities and teaming may be challenging, depending on the type of early intervention program. Greater possibilities existed for informal teaming when therapists provided intervention in centers versus the current practice in most states of providing intervention individually in homes and other community settings. In a study by Campbell and Halbert, early intervention service providers identified the need to improve communication and collaboration.7 Suggestions included a once-a-month meeting for team members to exchange information, a communication book available for all team members, and cotreatments with providers from different disciplines.

Provision of Early Intervention Services

Assessment and Intervention Planning

Teti and Gibbs traced the interest in infancy and infant assessment back to the 1800s and the Child Study Movement and the efforts of Stanley Hall, founder of the normative study of child development.65 Normative study of development is the basis for norm-referenced assessment, which assesses a particular behavior or attribute of children of a particular age group, establishing a mean age at development and an accompanying developmental curve against which other children can be evaluated.

An assumption of the developmental theory is that there is continuity of function from the infancy stages of sensorimotor development through the early childhood stages of verbalization and representational play. However, environmental and physiologic factors influence the continuity of development. The knowledge that environmental factors influence the infant’s development, and the belief that neurodevelopment in the infant is plastic and malleable, support the concept of early intervention.63,65

The developmental approach to infant assessment involves a multidimensional, holistic method in which individual developmental domains are assessed and their influence on behavior as a whole is considered. For example, infants with motor impairments are restricted in their ability to explore their environment, a critical component of sensorimotor development, which in turn can affect other developmental areas of cognition, language, and socialization.

The functional approach, which is analogous to an occupational approach, focuses on the child’s performance as it interacts with environmental activities, contexts, and conditions. To implement a functional approach, the therapist gathers information about the types of activities in which the child is to participate, methods of the child’s participation, and expected goals for each activity. Using this information, the therapist analyzes competencies and barriers to the child’s independent participation in relevant activities.

The functional approach relies on an ecologic framework that emphasizes skills and behaviors. This contrasts with the developmental approach, which documents the child’s skills by developmental domain (e.g., motor or cognitive). The functional approach documents the child’s behaviors by referencing skill clusters that describe occupations (e.g., feeding or playing).

Early intervention evaluation consists of a series of steps and is an ongoing, collaborative process of collecting, analyzing, and gathering information about the infant and the family to identify specific needs and develop goals in the IFSP.47 The evaluation, combined with a treatment program and ongoing reassessment, is a problem-solving process that continues throughout the period during which the infant or toddler is eligible for Part C services. Therapists can use developmental evaluations for screening, diagnosing or evaluating, and program planning. These processes are described in Chapters 7 and 8.

Evaluation and Planning

The process of evaluation is the gathering and interpreting of information on the child’s health status and medical background, current developmental levels of functioning, and family resources to maximize the child’s development. Two major goals in the evaluation of infants and toddlers are (1) determination of eligibility for early intervention programs and (2) development of outcomes and goals to guide the early intervention program. The second goal is addressed in the planning aspect of early intervention services, as discussed further on.

Eligibility Determination

Infants and toddlers who have established risk because of their diagnosis are automatically eligible for Part C services. This category includes diagnoses associated with developmental delay, such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, or spina bifida. Infants and toddlers without a specific diagnosis who are suspected of having developmental delay are entitled to an evaluation, which must be timely and comprehensive and must include input by a multidisciplinary team. The occupational therapist may be a member of the evaluation team. The team should be responsive to the family’s needs and desires when determining the time and location of the evaluation and which individuals should be present. The family’s involvement is central to the evaluation process, and a complete evaluation involves observation of interaction between the caregiver and the child. Information caregivers share about the child influences how assessments are implemented and results are interpreted. The focus of the evaluation should be on the process itself (i.e., engaging the child and eliciting representative performance). In addition to test scores, the evaluation should result in a list of strengths and weaknesses.49

The developmental areas that the team evaluates to determine eligibility are cognition, communication, motor, social-emotional, and adaptive. Play is another area of importance for the team to assess but is not part of most assessment instruments. However, play assessments demonstrate how well the child integrates separate skill areas and how he or she playfully interacts with social and physical environments. Therapists may use informal assessment through observing the child playing with caregivers, siblings, or peers. The Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment, Second Edition (TPBA-2) is an example of a commonly used play assessment that incorporates the early intervention team, rather than just one provider.43

Used frequently by early intervention teams, criterion-referenced assessments, including curriculum-based assessments, provide information about a child’s ability to perform a certain set of skills within a particular age range. Criterion-referenced tests are favored over norm-referenced tests, which compare a child’s abilities with those of their same-age peers, because children receiving early intervention services often have invalid scores because of a lack of flexibility in administering standardized protocols. The Hawaii Early Learning Profile (HELP); the Assessment, Evaluation and Programming System for Infants and Children, Second Edition (AEPS); and the Carolina Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers with Special Needs, Third Edition are well-used developmental curriculum-based assessments.3,38,54 Other recently developed scales are listed in Appendix 7-A.

Standardized assessments should never be the sole source for determining eligibility for early intervention services.1 Furthermore, few reliable, comprehensive standardized assessments are available for children between birth and 2 years of age. A standardized test provides merely a sampling of a child’s abilities and behaviors observed at a particular time and situation, from a particular perspective, and with a particular instrument.26 Assessment results that do not reflect the child’s typical functioning or behavioral characteristics are neither meaningful nor accurate. Therefore, professional judgment is a critical element of assessment. The test instruments chosen and the use of professional judgment may vary from state to state and may be specified by policies of the state lead agency.

Miller made the following recommendations for evaluation of infants and young children50:

• The therapist should base the assessment on an integrated developmental model. Parents and professionals must observe the child’s range of functions in different contexts to identify how the child can best be helped, rather than just coming up with a test score.

• Assessment involves multiple sources and multiple components of information. Parents and professionals contribute to forming the total picture of the child.

• An understanding of typical child development is essential to the interpretation of developmental differences among infants and young children.

• The assessment should emphasize the child’s functional capacities, such as attending, engaging, reciprocating, interacting intentionally, organizing patterns of behavior, understanding his or her environment symbolically, and having problem-solving abilities.25

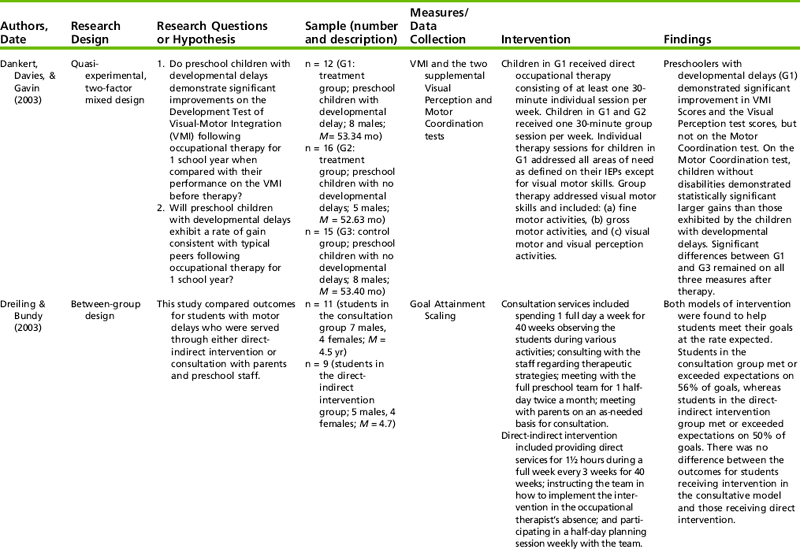

• The assessment process should identify the child’s current abilities, strengths, and areas of need to attain desired developmental outcomes (Figure 23-2).

FIGURE 23-2 The therapist can assess perceptual motor skills through observation of puzzle completion.

• The therapist should not challenge young children during the assessment by separating them from their parents or caregivers. The parents’ presence supports the child and begins the parent-professional collaborative process.

• An unfamiliar examiner should not assess young children. The therapist should give the child a “warm-up” period. Assessment by a stranger when the parent is restricted to the role of a passive observer represents an additional challenge.

• Assessments that are limited to easily measurable areas, such as certain motor or cognitive skills, should not be considered complete.

• The therapist should not consider formal or standardized tests the determining factor in the assessment of the infant or young child. Most formal tests were developed and standardized on typically developing children and not on those with special needs. Furthermore, many young children have difficulty attending to or complying with the basic expectations of formal tests. Formal test procedures are not the best context in which to observe functional capacities of young children. Assessments that are intended for intervention planning should use structured tests only as part of an integrated approach (Figure 23-3).

Once the team has defined a child’s eligibility for early intervention services, further assessment is important for the therapist and family to determine what intervention strategies and services are of greatest value to the child and family. At this point, evaluation becomes a comprehensive decision-making process to identify social-emotional, cognitive, motor, and communication problems; develop goals; and define an early intervention program plan.

Development of the IFSP

The IFSP is a map of the family’s services and informs anyone who will be working with the child and family which services will be provided, where they will be provided, and who will provide them. IDEA specifies that services must be provided in the infant’s natural settings. Development of the IFSP follows completion of the initial evaluation and assessment. The IFSP defines the environments in which the child is to be served and provides a statement of justification if services are not provided in natural environments. Occupational therapy intervention, as with other early intervention services, is based on identified concerns and expected outcomes in the IFSP. It is a process in which professionals and families share information to assist the family in making decisions about the types of services they believe will benefit them and the child. The IFSP also specifies who the provider will be; the location of the services; the frequency, intensity, and duration of services; and the funding sources. Box 23-3 lists the required components as they are stated in IDEA. The development of the IFSP occurs during a meeting facilitated by the service coordinator and attended by the family and at least one member of the evaluation team. The service coordinator’s role is to assist the family in accessing information and resources and coordinate implementation of the IFSP. Other service providers or anyone else the family would like to invite may also be in attendance. IFSP forms vary from state to state and among early intervention programs. Despite the differences in forms, each must include specific information as denoted by IDEA. The IFSP is a dynamic plan. To ensure that it meets the changing needs of the child and family, it is reviewed every 6 months or more often if deemed necessary. The family meets with other team members at least once a year. During this meeting, outcomes are examined and families may opt to make changes, including in the type of services the child receives.

Writing Goals and Objectives

The occupational therapist on the early intervention team focuses on outcomes from a family-centered perspective and identifies the child’s occupational performance as it relates to daily family routines. Box 23-4 lists questions to discuss with families. An outcome is a statement of changes desired by the family that can focus on any area of the child’s development or family life as it relates to the child.42 It reflects family priorities, hopes, and concerns in a broad statement that the whole team addresses. Before an outcome is developed, the early intervention team should collect information about the natural environments in which families and children spend their time, such as different areas of the home or the community (e.g., childcare center, playground, library). The team should also assist the family in identifying the activities that they typically do or would like to do in those environments, such as a family who eats breakfast at the kitchen table and would like the child to participate in eating as a morning routine.48,58 Early intervention providers may then provide strategies for caregivers to use to support child or family participation in an identified activity.

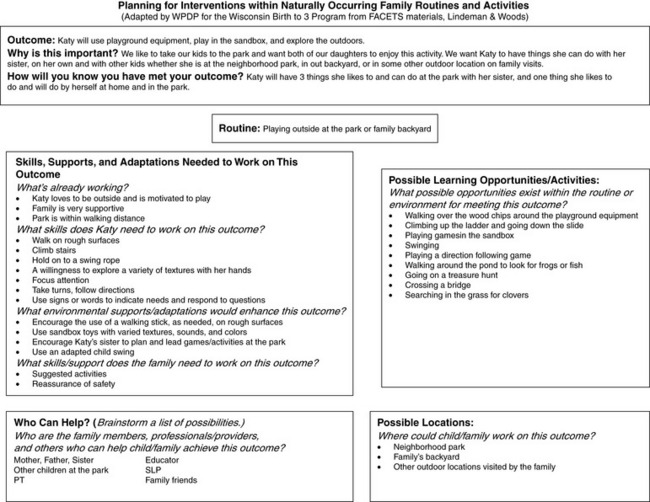

Once routines, activities, and suggested strategies have been identified, outcome statements may be written (see Figure 23-6). Because occupational therapists focus on child and family function and context, outcomes reflect performance areas and contexts rather than performance components.11 For example, it is not appropriate to write an outcome to “improve pincer grasp,” but instead to link a fine motor problem to daily function of both the child and the family unit. Examples of outcomes are “to feed himself finger food” and “to play with toys.” Often, outcome statements for children in early intervention are concerned with social participation. This includes those behaviors and skills needed to “fit in” and have been defined as “active engagement in typical activities available to and/or expected of peers in the same context” (p. 338).12 Typical outcome statements might be “to go to the grocery store with her parent” or “to play with other children.” Other outcome statements are parent focused and may include learning strategies to support the child or validation and understanding of the role of a parent of a child with special needs.

FIGURE 23-6 Sample Outcomes Sheet from an IFSP. (From Wisconsin Birth to 3 Information. [n.d.] Planning for Interventions within naturally occurring routines and activities. Retrieved September 2008 from http://www.waisman.wisc.edu/birthto3/KATY_ROUTINES.pdf).

After an outcome is developed, the next step is to describe what is happening now and what will happen when the outcome is achieved. Strategies are listed to address the outcome with people and resources that are needed. All relevant team members should be included. For example, if the outcome is “to feed himself finger food at a family meal,” the current problems might be “unable to hold food in hand and bring to mouth, cannot sit at a table, cries during meals unless parent is feeding him.” The team will recognize progress when the child can sit at the table independently and pick up and eat small pieces of food. To achieve this outcome, a number of strategies are proposed. The strategies are usually addressed according to the practice areas of specific disciplines. For instance, the physical therapist addresses stability for sitting (Figure 23-4) and the speech language pathologist provides strategies for communication, whereas the occupational therapist addresses sensory issues and hand use (Figure 23-5).

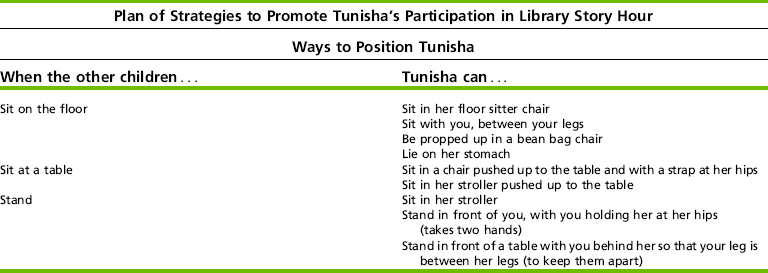

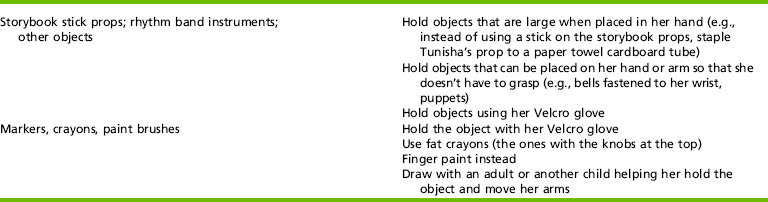

Outcomes focused on participation in community activities may be particularly meaningful for families and young children.8 Involvement in activities that occur in a setting outside the home, such as a local restaurant, church, or library, may be a caregiver’s main concern. Strategies could include adaptations to the environment or activity to support involvement and interventions to support development. An example of a worksheet that may be used to help families and other team members determine how to incorporate ideas and strategies into routines in community settings is provided (Table 23-2).

Transition Planning

Another aspect of planning is working with the early intervention team on the child’s transition from early intervention to preschool (Part C to Part B services). The transition process for young children with disabilities and their families is often characterized by stress because of the many factors involved, such as a change of environment (i.e., receiving early intervention services at home and then moving to a preschool classroom), a change of providers (i.e., the child and family may have a close relationship with early intervention providers, but will receive services from school personnel after the transition), and a difference in philosophy between early intervention programs and schools (i.e., family-centered in early intervention versus child-centered in schools).59 Stress may be decreased when transitions are well-planned and support to families and children is provided throughout the process.29

Occupational therapists have an important role in transition planning because their background in understanding how different contexts may influence occupational performance is a distinctive part of occupational therapy intervention.51 Outcomes and strategies written on the IFSP may be used as guides for addressing the needs of the child and family during the transition process, such as having a child participate in a small play group (Case Study 23-1) to help them adjust to the social expectations of preschool. Potential ways in which occupational therapists may support families and children during transition include: preparing caregivers for changes in roles and routines that will occur after the move to preschool, teaching caregivers how to work with their children to develop specific skills needed in preschool, and visiting the preschool classroom before the transition to assess needs for environmental adaptation or modification. The therapist might also support a smooth transition by making sure the child’s adaptive equipment is sent to the new setting and providing team members in the new setting a videotape of the child and caregivers doing self-care routines.69

Payment for Occupational Therapy Services

States determine how therapists are paid for their services. In some states, therapists are employed by the state agency that oversees the early intervention program, whereas in others the therapist is self-employed or employed through a private agency. In a typical scenario, the therapist bills for the time spent in direct, face-to-face contact with the child, family, or other caregiver. Billing for time spent in team meetings, on the phone with team members or family, and other indirect activities may or may not be reimbursed. Because state funding for early intervention programs is subject to annual budget shortfalls and at continuous risk for being cut, therapists are typically reimbursed through federal programs (i.e., Medicaid) or private insurance first with families paying part of the cost of early intervention services.24 Often the payment amount is determined on a sliding scale based on a family’s income. Although therapists working in early intervention must travel throughout the community to provide services in natural environments, travel is rarely reimbursed.

Working in Natural Environments

Part C of IDEA specifies that early intervention services are provided in the child’s natural environment. Natural environments are defined as settings that are natural or normal for children without disabilities and include the home and community settings. To enable the child to remain an integral part of the family and for the family to be integral parts of the neighborhood and community, services should be community based and in locations convenient to the family.18,37,66 Ideally, the therapist should offer the family a range of options so they can choose those that best fit their priorities, lifestyle, and values. These options should include those that provide the least restrictive settings in situations that would be natural environments for a typically developing child of the same age. Some examples are a playgroup, mother’s morning out program, childcare center, playgrounds, grocery stores, or fast-food restaurants (Figure 23-7). In addition, the outcomes on the IFSP should support the provision of services in the natural environment, with outcomes linked directly to family routines and contexts (Figure 23-8).39,40

FIGURE 23-7 The therapist encourages a child to participate in sensory motor activities on the playground.

The key to successful intervention is collaboration between therapists and caregivers within the home or childcare setting. Intervention in natural environments includes using toys and materials that can be found in the natural environment and will remain available to the family or other caregivers on a consistent basis. Therapists who rely on clinical equipment, whether they bring it to home visits or use it in their centers, may be trying to influence the child’s performance by using toys and equipment most comfortable for the therapist.28 Specialized equipment, such as suspended swings, therapy balls, or a child-sized table and chair (Figure 23-9), may be optimal for a clinic-based program for addressing sensory or motor deficits, but may not be available to families at home, caregivers at a child care facility, or another environment in the absence of the therapist. If early intervention is provided in a clinical setting, it is equally important for the therapist to offer opportunities for the family and other caregivers to learn and practice the interactions and principles to promote generalization in the natural environment. Best practice in occupational therapy infers expanding direct treatment to include primary caregivers (parents, grandparents, childcare providers). This involves learning to accept and respect differences in philosophies, priorities, and practices.27

FIGURE 23-9 The occupational therapist uses preschool materials to achieve the child’s fine-motor goals.

The Division of Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children supports the philosophy of inclusion in natural environments with the following statement: “Inclusion, as a value, supports the right of all children, regardless of their diverse abilities, to participate actively in natural settings within their communities. A natural setting is one in which the child would spend time if he or she had not had a disability” (p. 4).15

The philosophy of inclusion extends beyond physical inclusion to mean social and emotional inclusion of the child and family.10,67 The implications for occupational therapists are that they provide opportunities for expanded and enriched natural learning with typically developing peers. Self-contained or segregated settings are more restrictive and do not prepare children for participating or being a part of their natural and spontaneous environment.61

Occupational Therapy in Natural Environments

By providing early intervention services in natural environments, occupational therapists may take advantage of the actual contexts in which the occupations and co-occupations of children and families occur. Natural learning environments are those in which planned and unplanned, structured and unstructured, and intentional and incidental learning experiences occur.20 Mothers’ Morning Out and mother-infant playgroups exemplify such planned activity. Petting a puppy in the park is an unplanned activity. Hippotherapy and doing puzzles are structured activities, whereas playing on the playground is an unstructured one. Putting on one’s clothes is an intentional task; falling into a pile of autumn leaves is an incidental learning experience. Learning opportunities are composed of a variety of life experiences that make activity setting an appropriate description for natural learning environments.20

Literature on early intervention supports service delivery in natural environments and includes studies on natural intervention strategies, generalization of skills, inclusion, home-based services, and consultation with service providers.61 Research suggests that opportunities for learning in natural environments were most effective for addressing the developmental needs of young children when the opportunities were “interesting and engaging and…provided children contexts for exploring, practicing, and perfecting competence” (p. 90).21

Natural intervention strategies are those that use incidental learning opportunities that occur throughout the child’s typical activities and interactions with peers and adults (Figure 23-10), follow the child’s lead, and use natural consequences. Intervention strategies that occur in real-life settings over those that take place in more contrived clinic-based settings are more effective in promoting the child’s acquisition of functional motor, social, and communication skills (Figure 23-11).5,32,49 At one time, segregated settings such as special preschools and pediatric therapy clinics were seen as the only or preferred setting for children with disabilities to receive therapy services because inclusive opportunities were limited or did not exist. A resulting advantage of providing occupational therapy in natural environments is that children tend to be more comfortable in familiar settings such as their home and are more apt to be responsive and interactive with the therapist.

Generalization of skills is the ability to respond appropriately under spontaneous and natural conditions such as responses to people, environments, objects, and stimuli. Generalization of skills and behaviors occurs more readily when the intervention setting is the same as the child’s natural environment(s) (Figure 23-12).35 This requires the therapist’s ingenuity to develop strategies that will be acceptable and supported by the caregiver(s).8,28 Recognizing and accepting the family’s uniqueness in cultural and child-rearing practices, occupational therapists are able to facilitate the child’s ability to generalize new skills to a variety of settings (Figure 23-13).

FIGURE 23-12 Play with peers in natural environments helps the child generalize newly learned skills.

Inclusive early childhood programs provide opportunities for therapists to collaborate with primary caregivers including parents, grandparents, and childcare providers. Including siblings in therapy sessions can reinforce meaningful relationships between siblings who often feel left out during the care for their brother or sister with special needs. Inclusive settings provide a variety of enriching learning opportunities. Early childhood programs, for example, enhance opportunities for play and interactions with typically developing peers in real-life situations in the classroom. Therapists can benefit from collaborating with childcare providers through opportunities for peer role modeling and teaching (Figure 23-14). Participation in community programs gives the family common experiences for relating to friends and neighbors and helps them view their child as one with differing abilities rather than one with disabilities. To be successful, the inclusion program should ensure that (1) the child’s individual needs are met with appropriate aids and support services, (2) the child with special needs benefits from the typical program, and (3) the needs of the typical children are not compromised.

FIGURE 23-14 In an inclusive program, a peer models, encourages, and supports the child with developmental delays.

Home-based services are another example of services in the natural environment. Therapists have the benefit of seeing the child with special needs within the context of the family and in activities of daily living and a multitude of interrelated roles.28,61 Therapists are trained to be good observers, a skill that is a distinct advantage in natural environments. Home therapy programs designed during home-based visits tend to be more successful because therapists are more realistic in suggesting goals that are based on the resources available, can problem-solve issues unique to the home environment, and can better individualize the program to meet the family’s interests and needs.

Challenges to Implementing Therapy in Natural Environments

Providing therapy in natural environments presents several challenges from the perspective of therapy providers, families, and governing bodies (particularly state and local agencies). Therapists may engage in role release through coaching and provide support to caregivers within the child’s natural environments. A transdisciplinary model requires developing effective communication skills to make available the same repertoire of intervention strategies among providers and to support the family’s integration of the strategies into their daily routine.23,61

Occupational therapists must be able to work within multiple environments creatively and flexibly and take advantage of teachable moments. For example, the occupational therapist may have plans to use the playground for sensory integration strategies and the classroom in the childcare center for addressing fine motor skills, only to find it is a rainy day and the children cannot go outdoors. When she arrives at the classroom, the occupational therapist sees that the children are engaged in a rainy day activity of playing dress-up, which she immediately uses as the context for her intervention. Being able to revise treatment requires quick thinking and creativity.

Providing services within natural environments requires therapists to travel. Travel time between cases can be lengthy because of traffic in urban settings and distances in rural settings, resulting in increased mileage costs and lower caseloads.

Third-party payers (insurance companies, Medicaid, managed care organizations) may consider therapy in community settings as an indirect service, which is not reimbursable.27 Early intervention payers often reimburse only for direct or hands-on time with the child and generally will not reimburse for parent sessions, team meetings, or training of essential staff.28

Therapists must be familiar with state legislation related to early intervention and become advocates for their families. An early intervention therapist may assume the role of political activist as legislation may be amended. Interpretations of the laws often differ from region to region, which can affect service delivery.

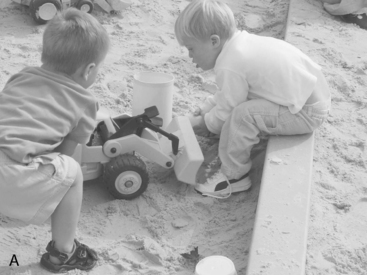

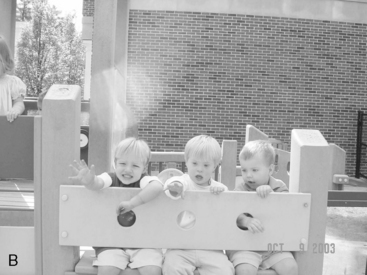

Occupational therapy services are provided in various settings that represent a continuum from the most restrictive (e.g., hospital settings) to the least restrictive (e.g., community settings). The setting should reflect family preferences and should be consistent with the needs of the child and the goals identified on the IFSP. For example, a child with significant and acute medical problems may be best served in the hospital-based program, whereas another with similar problems may be best served in the home. A child with autism may function best in a preschool program with typically developing peers. Occupational therapy in this natural environment would focus on functional behaviors and skills such as facilitating transitions from one activity to another, engaging with and responding to peers and teachers, practicing activities of daily living, or participating in sensory or tactile activities (Figure 23-15, A). The occupational therapist can include the typical peers as role models and as partners in play (Figure 23-15, B). Another child with the same diagnosis, however, may not be ready for a group environment and would be best seen in one-on-one therapy in an environment with fewer distractions, such as in a home. Early intervention legislation requires interagency cooperation; thus, families can choose the most appropriate settings and services from either private or public providers.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY INTERVENTION

Occupational therapists promote a child’s independence, mastery, and sense of self-worth and self-confidence in their physical, emotional, and psychosocial development. These services are designed to help families and other caregivers improve children’s functioning within their environments. Intervention characterized by engagement in meaningful occupations of the child and family in the natural environment is used to expand the child’s functional abilities.

Addressing Family and Child Needs in Natural Environments

In family-centered intervention, the occupational therapist addresses the needs of the entire family, rather than concentrating only on specific deficits in the child. The therapist should be guided by family concerns and the amount of involvement that various family members choose to have in the child’s intervention program. One important way for the therapist to increase the effect of their services is to make the program relevant to the family’s lifestyle and time commitments. Activities should be those that target behaviors and skills that the child can generalize to his or her daily routines at home, school, and community. Parents vary in their ability to implement structured therapy activities with their children. Family demands and support networks are always considerations in discussing home programs with parents. One mother stated the following: “There are times when even an acceptable amount of therapy becomes too much—when your child needs time just to be a child, or when you need time to be with the rest of the family. It is okay to say ‘no’ at those times, for a while. Your instinct will tell you when” (p. 51).64

Sometimes it is more important to support the role of parent than to assume that the parent can take on the role of the therapist. Daily routines in a family with a child who has a disability can take an excessive amount of time and energy, which does not allow for carrying out a therapy home program. Suggestions that the family can incorporate into the daily routine are the most successful. For example, the caregiver can provide tactile stimulation and range of motion at bath time; an older sibling can encourage the infant to reach for toys while their mother cooks dinner.

Occupational therapists can provide support for families by listening to them, giving positive feedback regarding parenting skills, encouraging recreational activities for the family, and helping them access community resources.22 Often the therapist can help the family by providing intervention to make daily routines go more smoothly. Examples are suggestions for positioning and handling to make feeding more efficient and for adapting a bath seat to make bathing less taxing. Research on supporting caregiver-child relationships is summarized in a table on the Evolve website.

An understanding of and respect for the individual differences between families are important because recent research suggests that there is great variation among families receiving early intervention services (Research Note 23-1). DeGrace reminds occupational therapists that customs and beliefs of families serve as the basis for daily routines and that therapists should “be aware of their biases, and sensitive to the ethnic and cultural ways of living of those we serve” (p. 348).14 She encourages therapists to think beyond routines and consider family rituals, multifaceted experiences that support the building of family relationships and occupations (e.g., saying goodnight, buying new school shoes) as key elements in family-centered intervention. In this way, occupational therapy goals then center on meaningful aspects of family life, such as celebrations, family traditions, and daily rituals.

Intervention Approaches

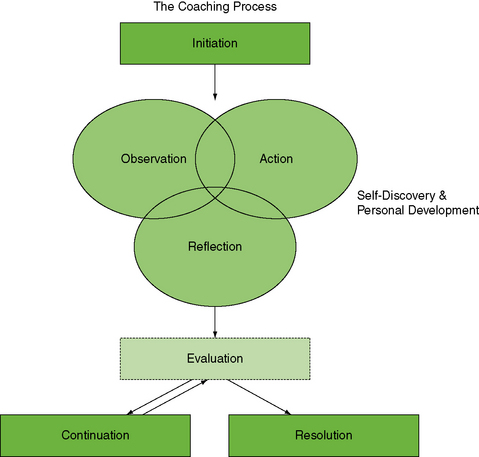

Several authors have described family-centered approaches for providing inclusive early intervention services within the natural environment.10 One approach that takes advantage of adult learning styles is coaching. Natural environments offer opportunities for therapists to coach caregivers to gain self-confidence and assume responsibility in their child’s daily care, and coaching other service providers to carry out occupational therapy interventions. As described by Rush, Shelden, and Hanft, the process of coaching is characterized by the coach (the early interventionist), who “has specialized knowledge and skills to share about growth and development, specific intervention strategies, and enhancing the performance of young children with disabilities,” and the learner (the caregiver), who “has intimate knowledge of a child’s abilities, challenges, and typical performance in a given situation…daily routines and settings, lifestyle, family culture…desirable goals for [the learner] and the child” (p. 38).60 The coach supports the learner and the child to achieve outcomes through a process described by Rush et al. (Figure 23-16)60:

FIGURE 23-16 The Coaching Process. Modified from Rush, D. D., Shelden, M. L., & Hanft, B. E. [2003]. Coaching families and colleagues: A process for collaboration in natural settings. Infants & Young Children 16[1], 33-47.

• Initiation: The coach or the learner identifies a need, and a joint plan is developed that includes the purpose of the coaching and specific learner outcomes.

• Observation: The coach may use four possible types of observation: (1) the learner demonstrates an existing challenge or practices a new skill while the coach observes; (2) the coach models a technique, strategy, or skill while the learner observes; (3) the learner consciously thinks about how to support the child’s learning while performing the activity; and (4) the coach and the learner observe aspects of the environment to determine how they may influence the situation.

• Action: This includes activities that take place at times other than when the coach and the learner are in contact, such as the learner’s practicing the new skill or strategy or engaging in a situation that may be discussed with the coach.

• Reflection: The coach uses questioning and reflective listening, and provides reflective feedback and joint problem solving to help the learner understand how to analyze practices and behaviors. The coach then reviews the discussion or observes the learner to assess the learner’s understanding. The learner’s strengths, competence, and mastery are acknowledged.

• Evaluation: The coach evaluates the effectiveness of the coaching process with both the learner and also himself or herself. Evaluation with the learner may not take place every time the coach and the learner have discussions; however, the coach should self-evaluate to determine if changes need to be made, if the coach is assisting the learner to achieve identified outcomes, or if the coaching needs to continue.

• Continuation: The results of the coaching session are summarized and a plan is developed for what should occur before and during the following session.

• Resolution: Both the coach and the learner agree that identified outcomes have been achieved. The learner has increased competence and confidence to support the child’s learning opportunities in the natural environment.

Coaching may be especially helpful in a service delivery model, where one early intervention team member is the primary provider for the child and family (Case Study 23-2). In this model, the other team members provide coaching on a consultative basis for the family, and they also provide coaching to the primary service provider. As in any team process, coaching requires that team members use good communication skills, and trust and respect one another. Opportunities for communication and collaboration are crucial to the success of coaching, thus necessitating support from early intervention programs and agencies for additional meeting time and covisits. It is important for team members to understand that coaching is not a linear process, but rather a process in which feedback is used to refine solutions as needed (Box 23-5).

The occupational therapist may work with caregivers to plan and carry out therapeutic interventions for the infant and child by integrating developmentally appropriate activities into daily routines and activity settings identified by the family, rather than focusing on the acquisition of isolated skills. For example, it would be inappropriate for the occupational therapist to concentrate on coaching caregivers on how to develop precise fingertip prehension without consideration of how this skill contributes to the overall function of the child in the environment or how it fits into the developmental needs of the child. Developmentally based curricula such as the HELP, AEPS, or Transdisciplinary Play-Based Intervention, Second Edition provide activities matched to the developmental sequences within each domain.44 However, the therapist should guard against using a “cookbook” approach in intervention for specific developmental deficits.

After identifying a need in a specific domain, such as fine motor skills, the therapist can work with caregivers to identify learning opportunities in the natural environment that require a child to use those skills. To promote generalization of the fine motor skills, the therapist and caregivers should use play activities that involve the “just right” challenge to the child across domains (i.e., activities that include skill building in the cognitive and social domains). For example, playing with puzzles is a motor task that also involves cognitive skills such as concept of size, shape, and dimension, and visual perceptual skills such as visual closure. Most developmental skills and play occupations are learned in the context of social interaction, including give and take with another child or adult, eye contact, praise, and delight at successful attempts. A team whose members have overlapping functions can effectively address developmental needs (Figure 23-17).

Working with Medically Fragile Children

Young children who have special health care needs make up approximately 11.2% of the age group birth through 5 years.34 Children who are medically fragile represent a subset of these and often require the use of specialized medical equipment (e.g., ventilator, gastrostomy tube) and receive services from two or more medical specialists (e.g., neurologist, developmental pediatrician).52 They and their families may have additional challenges when receiving health care services, including early intervention. For instance, families of these children in the birth through 5 age group reported that their health care providers did not listen carefully or spend enough time with them at visits, and had significantly more hospitalizations, doctor visits, and nonphysician visits (e.g., occupational therapy) than families who did not have children with complex health care needs.34 More time is spent coordinating the care of young children with complex health care needs than that of other children in early intervention.52 A recent study found that 87% of families of young medically fragile children (birth through 5) identified that they usually or always felt like a partner in their child’s care; however, the percentage decreased as the poverty level increased and as the child’s functional abilities decreased.13

Occupational therapists working with medically fragile children in early intervention should be prepared to address family needs related to daily routines, such as helping families determine optimal positioning during catheterization or timing attempts at oral feeding in a child with a gastrostomy tube. Occupational therapists should identify that the child’s primary caregivers know the child best, thus respecting family opinions regarding the child’s care. In addition, occupational therapists need to be flexible with family schedules, given the frequency with which a young child with complex health care needs may require hospitalizations or doctor visits. Occupational therapists should work closely with the team to determine the optimal approach for involving families, particularly those who live in poverty or represent diverse cultures. A thoughtful, family-centered approach that takes into account specific, individualized needs of the child and family is necessary.

Areas of Intervention

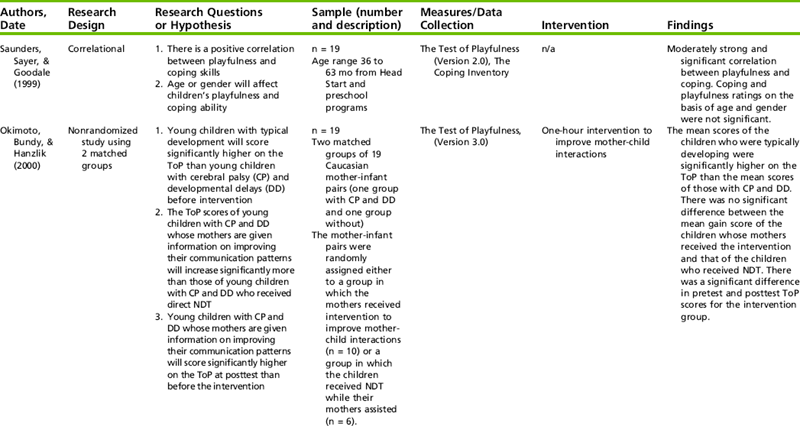

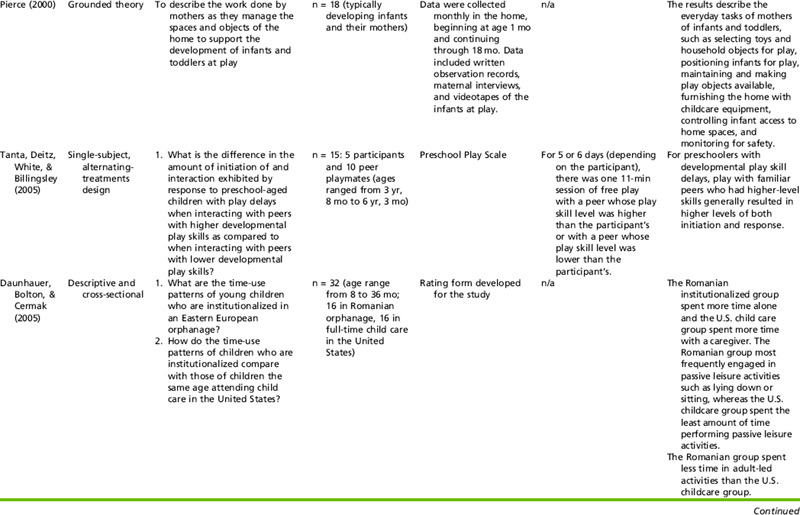

One of the most important areas of a child’s development is involvement in the occupation of play. Play is open-ended, self-initiated, self-directed, and unlimited in its variety. Play can be exploratory, symbolic, creative, or competitive in nature (see Chapter 18). Skills that will be the foundation for engagement in other occupations, such as the ability to manipulate objects, problem-solve, and attend to tasks, may be developed and practiced during play. Research on play with young children is summarized in Table 23-3.

TABLE 23-3

Relevant Research on Play Skills and Young Children

Summary and Practice Applications:

In the series of studies presented above, the role of caregivers and others for supporting children’s play activities in the infant through preschool years is described. The studies by Okimoto et al. (2000) and Daunhauer et al. (2007) specifically point to the importance of caregivers in helping young children with disabilities or at-risk for developmental delays to develop play occupations. Tanta et al. (2005) suggest that similar-age peers may also have the potential to support play skill development in at-risk populations although more research is needed. In sum, the research findings on play in young children indicate that many factors relate to engagement of play, particularly for young children with developmental delays.

Occupational therapists working in early intervention should involve caregivers in play-based interventions and routines.

Special attention should be given to the type of interactions caregivers have with their children during play and modeling or coaching strategies may be used by occupational therapists to assist caregivers in developing strong play interaction skills.

Play in the natural environment should incorporate typically developing peers when possible, such as a community playground.

Data from Saunders, I., Sayer, M., & Goodale, A. (1999). The relationship between playfulness and coping in preschool children: A pilot study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 221–226; Okimoto, A. M., Bundy, A., & Hanzik, J. (2000). Playfulness in children with and without disability: Measurement and intervention. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54, 73–82; Pierce, D. (2000). Maternal management of the home as a developmental play space for infants and toddlers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54, 290–299; Tanta, K. J., Deitz, J.C., White, O., & Billingsley, F. (2005). The effects of peer play level on initiations and responses of preschool children with delayed lay skills. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59, 437–445; Daunhauer, L. A., Bolton, A., & Cermak, S. A. (2005). Time-use patterns of young children institutionalized in Eastern Europe. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research: Occupation, Participation, and Health, 25, 33–40; Daunhauer, L. A., Coster, W. J., Tickle-Degnen, L., & Cermak, S. A. (2007). Effects of caregiver-child interactions on play occupations among young children institutionalized in Eastern Europe. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 429–440.

Learning how to play may also be a goal of intervention, particularly for children with significant disabilities. Children with special needs may not develop play skills because of long hospitalizations or medical treatments, or because of the limitations imposed by a physical impairment. Other children may experience deficits in play because of cognitive limitations or difficulties in social interactions.

Because play is usually embedded in the daily routine of young children, therapists should coach caregivers on how to use different toys or play activities to support the child’s learning of new skills. The occupational therapist should work with families to determine the natural environments where play takes place or where caregivers or children want play to occur, such as in the backyard, the child’s bedroom, or a community playground. Childcare providers may also receive support to learn strategies and approaches that will enhance play. The therapist may suggest ways in which the provider can encourage age-appropriate play with peers, and play with toys and other materials (e.g., sand and water table) at the childcare facility.

Objects and materials typically found in the natural environment should be the focus of play, rather than items brought into the home by the therapist (e.g., therapy ball). Therapists can show caregivers how to create games and toys out of everyday objects, such as plastic containers and wooden spoons. Because play is intrinsically motivating for young children, therapists and caregivers should seek natural learning opportunities within play activities that the child enjoys. For example, a toddler with hemiplegic cerebral palsy is observed playing with stuffed animals and using her affected arm to stabilize her trunk when reaching into a bin to take them out. This activity supports a motor-based occupational therapy goal for the child to incorporate her affected arm in play and may be repeated for practice with gradual adaptation (e.g., the toddler gives her animals a bear hug before putting them back in the bin). This is a learning opportunity that uses play as initiated by the child with her own toys.

Sometimes therapists are so intent on remediating certain deficits that they ignore the importance of play. A toy becomes only a motivator, or a diversion, so that a specific skill or component of that skill can be mastered.6 Although this may sometimes be necessary, the therapist must also teach caregivers to facilitate play skills in the child and use play as a way of enhancing development. To use play as an intervention strategy for caregivers, the occupational therapist must model playfulness in interactions with the child. Whether it is a game of peek-a-boo or knocking down a pretend wall and falling into the foam blocks, the activity should elicit a sense of enjoyment and fun (Figure 23-18).

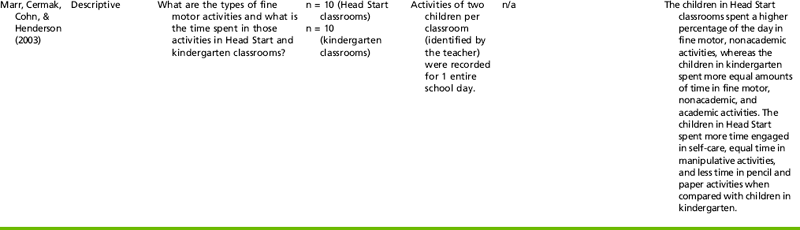

Motor Performance

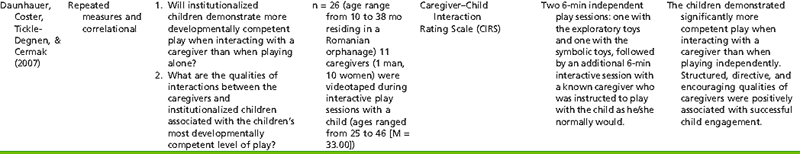

The occupational therapist is often concerned with delayed function or atypical function in the motor domain, particularly fine motor skills including grasp and release of objects, bilateral manipulation, and in-hand manipulation; hesitancy to touch and explore with the hands; and lack of hand-to-mouth pattern and other skills. Some relevant research for occupational therapists on motor skills and young children is presented in Table 23-4. Intervention begins with analyzing the quality of movement and determining underlying factors, such as tactile discrimination and kinesthetic awareness.

TABLE 23-4

Examples of Research on Motor Skills and Young Children

Summary and practice Applications:

The research studies on development of motor skills provides preliminary support for the use of different service delivery models such as consultation through home programs and in preschools (Dankert, et al., 2003; Dreiling & Bundy, 2003).

Although several studies above suggest that consultation may be an effective approach for preschool-age children, more research is needed to determine if children in early intervention programs benefit more from this approach than individual therapy. Future research on the use of transdisciplinary models and parent support activities, such as coaching, would greatly enhance occupational therapy’s involvement in early intervention.

Data from Dankert, H. L., Davies, P. L., & Gavin, W.J. (2003). Occupational therapy effects on visual-motor skills in preschool children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 542–549; Dreiling, D., S., & Bundy, A. C. (2003). A comparison of consultative model and direct-indirect intervention with preschoolers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 566–569; Marr, D., Cermak, S., Cohn, E. S., & Henderson, A. (2003). Fine motor activities in Head Start and kindergarten classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57, 550–557.

To analyze motor performance, the therapist observes how functional a child is in a particular skill, such as stacking blocks. Although this is not an essential functional skill, it is a play activity that assists in development of sufficient hand skill for manipulating, placing, and releasing objects. These skills enable the child to use tools with control and with the arms unsupported. When this type of skill appears delayed or deficient, the therapist analyzes which underlying components are interfering with performance (Figure 23-19). For example, the therapist notes the influence of muscle tone and proximal stability when the child attempts stacking 1-inch cubes. The therapist must then determine the following:

FIGURE 23-19 Observation of play with age-appropriate materials is used to assess fine motor skills.

• Are spasticity, tremor, or associated movements (mirroring) present?

• Does total body tone change with effort?

• Can the child stack the cubes while sitting unsupported on the floor?

• Does the child slump or demonstrate lack of postural stability?

• Can the child easily disassociate the movement of the arm from the body?

• Is the child’s hand-eye coordination delayed?

• Does inattention or a lack of understanding interfere with performing the task?

• Does the child have difficulty with the motor planning needed for precise release of one block on top of another?

• Does tactile hypersensitivity cause the child to be reluctant to handle the block or result in flinging or throwing any object held in the hand?

The best indication of the child’s fine motor abilities may be through observation of spontaneous activity. For instance, a child with autistic spectrum disorder or another disorder that interferes with the child’s ability to interact with others may be unable to imitate or follow directions for a task. Therefore inability to stack blocks may reflect not a deficit in fine motor ability but rather inexperience or disinterest in the activity. Motivation must always be taken into account in analyzing a child’s ability to perform an activity. In addition to observing spontaneous activity, the occupational therapist could ask caregivers to suggest motor-based activities that are meaningful to the child and then gradually modify them to increase the challenge. Through careful observation, the occupational therapist can establish what underlying factors may be interfering with the development of motor skills.

Once the analysis is complete, the occupational therapist works with caregivers to determine how various age-appropriate toys, games, sensorimotor experiences, and other strategies may be incorporated into the child’s daily routine to remediate motor skill deficits. For instance, a family who enjoys hiking may encourage their toddler to pick up fallen leaves on the trail and put them in a small bag, an activity that encourages refined grasp and release skills. A provider in an infant’s childcare room may take extra time to play with the infant using colorful rattles to encourage activation of the arm for reaching.

Because engaging in motor activities may be especially challenging for young children with special needs, it behooves the occupational therapist to be creative when designing intervention strategies with caregivers. New motor skills are learned through practice.9 The more a child enjoys the motor activity, the more likely he or she will perform it repeatedly. Also, an intervention strategy that fits easily into a caregiver’s routine is more likely to be repeated. In this way, practice becomes incorporated into the everyday life of the child and family.

Sensory Processing

Infants and toddlers who have difficulty processing sensory information lack the ability to cope with environmental demands or to achieve internal control. As infants, they may be irritable, cry frequently, be difficult to comfort, or have difficulty with changes in routine. Alternately, they may sleep extensively with little awake time, seem oblivious to noises that others attend to, or have delays in motor development. As these infants move into toddlerhood, their deficits in sensory processing may continue and influence their engagement in everyday occupations such as dressing, grooming, and eating meals. Occupational therapists have an important role in addressing sensory processing challenges in young children (see Chapter 11).

Dunn described four main types of sensory processing difficulties in young children17:

• Low registration: These children notice less in their environment. Although they appear more easygoing than other children, they may have behaviors that interfere with their learning such as not responding to their name when called and having a more difficult time completing tasks.

• Sensation seeking: These children need a greater amount of sensory input than others and will seek out intense sensory experiences. They may have difficulty completing tasks because they become easily distracted by sensory experiences and may find ways to give themselves sensory input, such as through frequent movement or humming.

• Sensation avoiding: These children tend to notice things in the environment more than others, becoming easily overwhelmed by sensory input. They are often alone, isolating themselves from others and preferring to be in quiet places.

• Sensory sensitivity: These children detect sensation more than others, tending to become distracted and often upset by sensory events that are not easily noticed by others.

The occupational therapist recognizes that sensory processing difficulties have a pervasive influence on the child’s development. There are two main ways in which the occupational therapist may intervene. First, the therapist may use appropriate tactile, vestibular, and proprioceptive input that elicits organized behavior and adaptive responses on the part of the child. For example, it was determined that a 1-year-old child displayed tactile sensitivity. He refused to hold toys, refused to bear weight on his arms, was irritable when held, pulled away from touch, and avoided exploring his environment. The occupational therapist worked with the caregivers to plan intervention that included proprioceptive and tactile input and midline play with textured toys. She and the child’s mother reviewed the daily routine and determined that additional tactile stimulation be provided at bath time with water play, foamy soap, and terrycloth rubs. Soon the child was clapping his hands spontaneously—a skill he had not attempted before and a nice adaptive response (Case Study 23-3).

A second approach to addressing sensory processing difficulties has been described by Dunn.17 In this approach, occupational therapists focus on context, including both the physical context and the social context (e.g., relationship between child and caregivers), making modifications and adaptations to natural environments when needed. Because sensory experiences are rooted in the daily routines of children, occupational therapists need to work with caregivers to determine when the child demonstrates difficulties. The therapist may then provide strategies for modification or adaptation of the routine to support the child’s engagement. Generally, children who have low registration and those who are sensation seeking will benefit from intense sensory experiences integrated into the daily routine, whereas children who are sensation avoiding need less sensory input throughout the day, and children with sensory sensitivity will benefit from structured patterns of sensory experiences incorporated into daily routines. Specialized assessment tools, such as The Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile, may be used to help determine intervention needs.16

Dunn provides the example of Millie, a 30-month-old toddler who is sensory avoiding.17 After hearing concerns from her parents, the therapist visits Millie at a daycare center to observe her play behaviors and notices that Millie has difficulty playing in groups. It appears that Millie becomes overwhelmed during open playtime and tends to watch the other children instead of engaging in play. To support Millie at daycare, the therapist, parents, and daycare providers discuss potential strategies and decide to provide her with a separate yet visually accessible play space, enabling her to participate in play and limiting the sensory input.

Infants and toddlers with sensory processing difficulties can be challenging for caregivers, particularly infants and toddlers who fall into the sensory sensitivity category because their behavior may be unpredictable. The caregiver-child relationship with an infant who has behaviors such as crying when picked up or cuddled, sleeping only for short periods, feeding poorly, and smiling infrequently may be characterized by weak caregiver attachment because they can interfere with the bonding process.68 Occupational therapists should work closely with caregivers to address not only changes in the daily routine to support the young child, but also to investigate ways to support the caregiver-child relationship, such as modeling for caregivers how to engage their infant in simple play activities without providing extra sensory stimulation.

Self-Care/Adaptive

Occupational therapists have longstanding experience in the area of activities of daily living (ADLs), also referred to as self-care or adaptive skills. In children, the focus is on participation in eating and feeding, dressing, toileting, and sleeping. Physical difficulties may interfere with the ability to perform self-care skills, such as bringing the hand to the mouth during feeding and cooperating in dressing by extending an arm or a leg. Psychosocial behaviors that influence the acquisition of self-care skills are temperament, self-regulation, caregiver-child interaction, motivation, and adaptability. Sensory processing problems may cause aversive behaviors, such as the child with tactile hypersensitivity who gags on some foods or refuses to wear certain articles of clothing. The evaluation of self-care skills should occur in the natural environment in which the skills occur, such as the child’s home, daycare center, or preschool (Figure 23-20). Information on interventions for improving self-care skills and feeding may be found in Chapters 15 and 16, respectively.

Adapted Equipment and Positioning

The occupational therapist in early intervention can make an important contribution to the overall functioning of children through the recommendation and provision of appropriate adapted equipment (see Chapters 16 and 21) (Figure 23-21). A floor sitter may enable the child with cerebral palsy to play on the floor near his or her typically developing peers. An adapted insert for a chair may make it possible for a child to begin to use the hands for an art project or to self-feed. As the neurologically involved child approaches preschool age and is not yet ambulating, the parents may have to face the prospect of obtaining a wheelchair. The occupational therapist can assist in recommending appropriate equipment and in being sensitive to the effect that envisioning their child in a wheelchair may have on the family. The child with a neurologic impairment who can stay in an infant stroller or a highchair does not appear as different as the 3-year-old child who must have a wheelchair and special equipment.

SUMMARY

Occupational therapists use holistic approaches with children and their families that emphasize functional, developmentally appropriate approaches. By recognizing that children are part of a family system, the therapist designs programs that fit into the family’s daily routine; consider sensory, motor (gross and fine), social, and cognitive aspects of performance; and emphasize play as the child’s primary occupation.

REFERENCES

1. Andersson, L.L. Appropriate and inappropriate interpretation and use of test scores in early intervention. Journal of Early Intervention. 2004;27(1):55–68.

2. Blackman, J.A. Early intervention: A global perspective. Infants & Young Children. 2002;15(2):11–19.

3. Bricker. Assessment, evaluation, and programming system (AEPS) for infants and children, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes, 2002.

4. Bruder, M.B. The provision of early intervention and early childhood special education within community early childhood programs: Characteristics of effective service delivery. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 1993;13:19–37.

5. Bruder, M.B., Bologna, T. Collaboration and service coordination for effective early intervention. In: Brown W., Thurman S.K., Pearl I.F., eds. Family centered early intervention with infants and toddlers: Innovative cross-disciplinary approaches. Baltimore: Brookes; 1993:103–127.

6. Burke, J. Play: The life role of the infant and young child. In: Case-Smith J., ed. Pediatric occupational therapy and early intervention. 2nd ed. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998:189–206.

7. Campbell, P., Halbert, J. Between research and practice: Provider perspectives on early intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2002;22:213–226.