Structural Disorders and Neoplasms of the Reproductive System

• Describe the various structural disorders of the uterus and vagina.

• Discuss the pathophysiology of selected benign and malignant neoplasms of the female reproductive tract.

• Compare the common medical and surgical therapies for selected benign gynecologic conditions.

• Explain diagnostic procedures in client-centered terms.

• Examine the emotional effects of benign and malignant neoplasms.

• Develop a nursing care plan for a woman with endometrial cancer who has had a hysterectomy.

• Differentiate treatments for preinvasive and invasive conditions.

• Identify critical elements for teaching clients with selected benign or malignant neoplasms.

• Investigate health-promoting behaviors that reduce cancer risk.

• Assess the effects of and treatments for malignant neoplasms during pregnancy.

• Discuss the development and sequelae of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia.

Women are at risk for structural disorders and neoplastic diseases of the reproductive system from the age of menarche through menopause and the older years. Problems may include structural disorders of the uterus and vagina related to pelvic relaxation and urinary incontinence and chronic pain related to vulvodynia. Benign neoplasms of the reproductive organs, such as fibroids and cysts, and malignant neoplasms of the reproductive system also may occur. Benign tumors usually do not endanger life, tend to grow slowly, and are not invasive. Malignant tumors (cancers) grow rapidly in a disorganized manner and invade surrounding tissues. The development of structural disorders and benign or malignant neoplasms can have far-reaching effects for the woman and her family. Beyond the obvious physiologic alterations, the woman also experiences threats to her self-concept and her ability to cope. A woman’s concept of herself as a sexual being can be affected by the condition and its treatments. A woman’s family also is challenged in the way it responds to her diagnosis. When cancer occurs with pregnancy, it adds to the complexity of physical and emotional responses to childbearing.

Nurses have important roles in teaching women about early detection and treatment and in providing supportive care to women and their families. This chapter presents information that will assist the nurse in assessing and identifying problems associated with structural problems or benign or malignant reproductive neoplasms. Nursing care concepts related to early detection, treatment methods, and education are included.

Structural Disorders of the Uterus and Vagina

Alterations in pelvic support include uterine displacement and prolapse, cystoceles and rectoceles, urinary incontinence, and genital fistulas. Research by Wu and colleagues (2009) suggests that the prevalence of these disorders will increase by as much as 55% in the United States between the years 2010 and 2050 as the numbers of older women increase.

Uterine Displacement and Prolapse

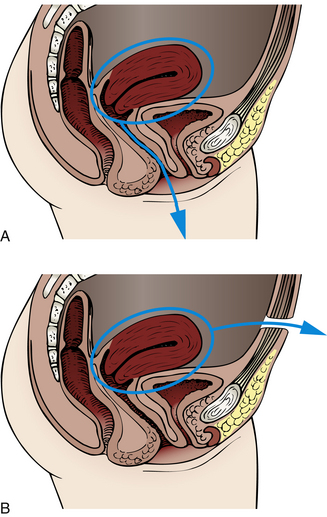

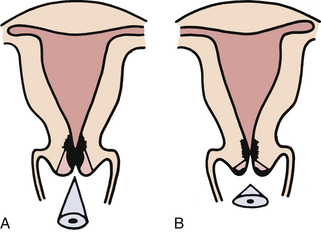

The round ligaments normally hold the uterus in anteversion, and the uterosacral ligaments pull the cervix backward and upward (see Fig. 4-3). Uterine displacement is a variation of this normal placement. The most common type of displacement is posterior displacement, or retroversion, in which the uterus is tilted posteriorly, and the cervix rotates anteriorly. Other variations include retroflexion and anteflexion (Fig. 11-1).

FIG. 11-1 Types of uterine displacement. A, Anterior displacement. B, Retroversion (backward displacement of the uterus).

By 2 months postpartum, the ligaments should return to normal length, but in about one third of women, the uterus remains retroverted. This condition is rarely symptomatic, but conception may be difficult because the cervix points toward the anterior vaginal wall and away from the posterior fornix, where seminal fluid pools after coitus. If symptoms occur, they may include pelvic and low back pain, dyspareunia, and exaggeration of premenstrual symptoms.

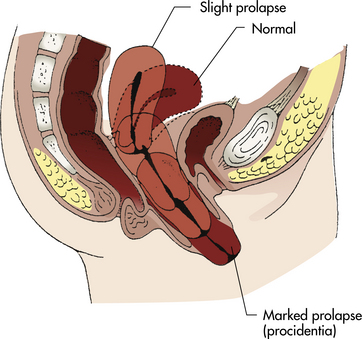

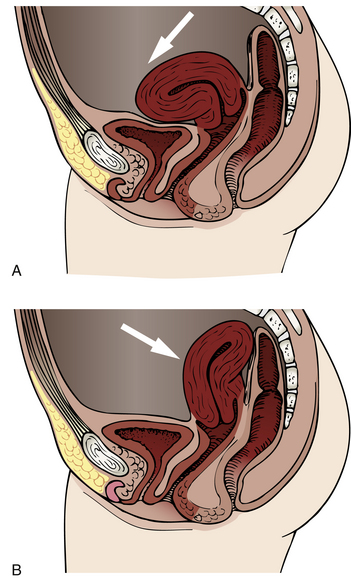

Uterine prolapse is a more serious type of displacement. The degree of prolapse can vary from mild to complete. In complete prolapse, the cervix and body of the uterus protrude through the vagina, and the vagina is inverted (Fig. 11-2).

Uterine displacement and prolapse can be caused by congenital or acquired weakness of the pelvic support structures (often called pelvic relaxation). In many cases, problems can be a delayed but direct result of childbearing. Although extensive damage may be noted and repaired shortly after birth, symptoms related to pelvic relaxation most often appear during the perimenopausal period, when the effects of ovarian hormones on pelvic tissues are lost, and atrophic changes begin. Pelvic trauma, stress and strain, and the aging process also are contributing factors. Other causes of pelvic relaxation include reproductive surgery and pelvic radiation.

Clinical Manifestations: Symptoms of pelvic relaxation generally relate to the structure involved: urethra, bladder, uterus, vagina, cul-de-sac, or rectum. The most common complaints are pulling and dragging sensations, pressure, protrusions, fatigue, and low backache. Symptoms may be worse after prolonged standing or deep penile penetration during intercourse. Urinary incontinence can be present.

Cystocele and Rectocele

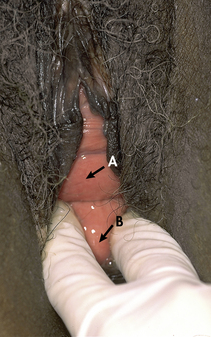

Cystocele and rectocele almost always accompany uterine prolapse, causing the uterus to sag even farther backward and downward into the vagina. Cystocele (Fig. 11-3, A) is the protrusion of the bladder downward into the vagina that develops when supporting structures in the vesicovaginal septum are injured. Anterior wall relaxation gradually develops over time as a result of congenital defects of support structures, childbearing, obesity, or advanced age. When the woman stands, the weakened anterior vaginal wall cannot support the weight of the urine in the bladder; the vesicovaginal septum is forced downward, the bladder is stretched, and its capacity is increased. With time the cystocele enlarges until it protrudes into the vagina. Complete emptying of the bladder is difficult because the cystocele sags below the bladder neck. Rectocele is the herniation of the anterior rectal wall through the relaxed or ruptured vaginal fascia and rectovaginal septum; it appears as a large bulge that may be seen through the relaxed introitus (see Fig. 11-3, B).

FIG. 11-3 A, Cystocele. B, Rectocele. (From Seidel, H., Ball, J., Dains, J., Flynn, J., Solomon, B., & Stewart, R. [2011]. Mosby’s guide to physical examination [7th ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.)

Clinical Manifestations: Cystoceles and rectoceles often are asymptomatic. If symptoms of cystocele are present, they include complaints of a bearing-down sensation or that “something is in my vagina.” Other symptoms include urinary frequency, retention, and/or incontinence, and possible recurrent cystitis and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Pelvic examination will reveal a bulging of the anterior wall of the vagina when the woman is asked to bear down. Unless the bladder neck and urethra are damaged, urinary continence is unaffected. Women with large cystoceles complain of having to push upward on the sagging anterior vaginal wall to be able to void.

Rectoceles may be small and produce few symptoms, but some are so large that they protrude outside of the vagina when the woman stands. Symptoms are absent when the woman is lying down. A rectocele causes a disturbance in bowel function, the sensation of bearing down, or the sensation that the pelvic organs are falling out. With a very large rectocele it may be difficult to have a bowel movement. Each time the woman strains during bowel evacuation, the feces are forced against the thinned rectovaginal wall, stretching it more. Some women facilitate evacuation by applying digital pressure vaginally to hold up the rectal pouch.

Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) affects young and middle-aged women, with the prevalence increasing as the woman ages. Although nulliparous women can have UI, the incidence is higher in women who have given birth and increases with parity. Women who are overweight and those who have had a hysterectomy are also at increased risk (Sung & Hampton, 2009). There are conflicting data about ethnicity and race as contributing factors (Waetjen, Laio, Johnson, Sampselle, Sternfield, Harlow, & Gold, 2007). Conditions that disturb urinary control include stress incontinence due to sudden increases in intraabdominal pressure (such as that due to sneezing or coughing); urge incontinence, caused by disorders of the bladder and urethra, such as urethritis and urethral stricture, trigonitis, and cystitis; neuropathies, such as multiple sclerosis, diabetic neuritis, and pathologic conditions of the spinal cord; and congenital and acquired urinary tract abnormalities. Research also suggests that a significant number of women have undiagnosed urinary incontinence (Wallner, Porten, Meenan, O’Keefe Rosetti, Calhoun, Sarma, & Clemens, 2009).

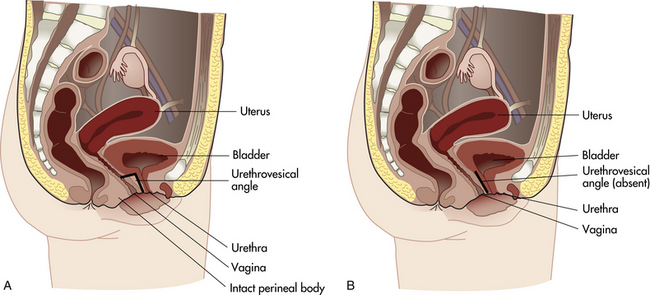

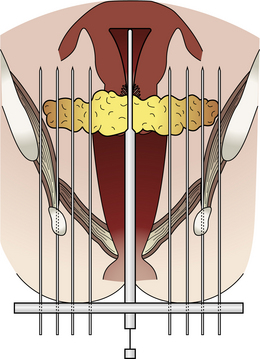

Stress incontinence may follow injury to bladder neck structures. A sphincter mechanism at the bladder neck compresses the upper urethra, pulls it upward behind the symphysis, and forms an acute angle at the junction of the posterior urethral wall and the base of the bladder (urethrovesical angle) (Fig. 11-4). To empty the bladder, the sphincter complex relaxes, and the trigone contracts to open the internal urethral orifice and pull the contracting bladder wall upward, forcing urine out. The angle between the urethra and the base of the bladder is lost or increased if the supporting pubococcygeus muscle is injured; this change, coupled with urethrocele, causes incontinence. Urine spurts out when the woman is asked to bear down or cough in the lithotomy position.

Genital Fistulas

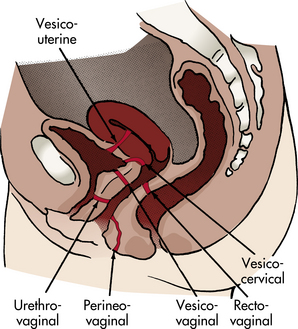

Genital fistulas are perforations between genital tract organs. Most occur between the bladder and the genital tract (e.g., vesicovaginal); between the urethra and the vagina (urethrovaginal); and between the rectum or sigmoid colon and the vagina (rectovaginal) (Fig. 11-5). Genital fistulas also may be a result of a congenital anomaly, gynecologic surgery, obstetric trauma, cancer, radiation therapy, gynecologic trauma, or infection (e.g., in the episiotomy).

Collaborative Care

Assessment for problems related to structural disorders of the uterus and vagina focuses primarily on the genitourinary tract, the reproductive organs, bowel elimination, and psychosocial and sexual factors. A complete health history, a physical examination, and laboratory tests are done to support the appropriate medical diagnosis. The nurse must assess the woman’s knowledge of the disorder, its management, and possible prognosis. Possible nursing diagnoses for structural problems of the uterus and vagina include the following:

• Deficient knowledge related to:

• Constipation or diarrhea related to:

• Ineffective coping related to:

• Interrupted family processes related to:

• lack of skill in self-care procedures

• lack of understanding of the reasons for the need to comply with therapy

• Social isolation, spiritual distress, disturbed body image, or chronic low self-esteem related to:

The health care team works together to treat the disorders related to alterations in pelvic support and to assist the woman in management of her symptoms. In general, nurses working with these women can provide information and self-care education to prevent problems before they occur, to manage or reduce symptoms and promote comfort and hygiene if symptoms are already present, and to recognize when further intervention is needed. This information can be part of all postpartum discharge teaching or can be provided at postpartum follow-up visits in clinics or physician/nurse-midwife offices, during postpartum home visits, or during gynecologic health examinations. In addition, information on how to prevent or recognize problems can be a topic for workshops for women or health fairs in community settings.

Besides providing information about prevention, nurses participate in a team effort to prepare the woman for surgery and self-care after discharge. Preoperative teaching involves the primary nurse, operating room nurse, surgeon, and anesthesia provider. Postoperatively, a nurse in the health promotion setting may be most aware of the woman’s living circumstances, physical limitations, and social problems and therefore may be best suited to coordinate continuity of care after discharge.

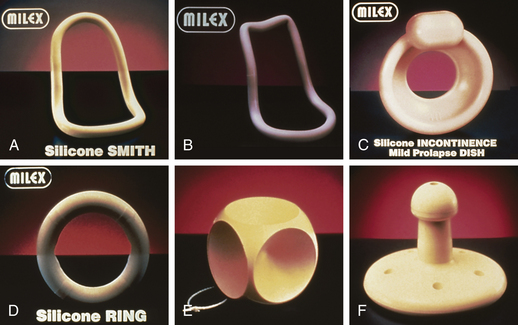

Interventions for specific problems depend on the problem and the severity of the symptoms. If discomfort related to uterine displacement is a problem, several interventions can be implemented. Kegel exercises (see p. 91) can be performed several times daily to increase muscle strength. A knee-chest position performed for a few minutes several times a day can correct a mildly retroverted uterus. A fitted pessary to support the uterus and hold it in the correct position (Fig. 11-6) may be inserted in the vagina. Usually a pessary is used only for a short time because it can lead to pressure necrosis and vaginitis. Good hygiene is important; some women can be taught to remove the pessary at night, cleanse it, and replace it in the morning. If the pessary is always left in place, regular douching with commercially prepared solutions or weak white vinegar solutions (1 tablespoon to 1 quart [liter] of water) to remove increased secretions and keep the vaginal pH at 4 to 4.5 is suggested. After a period of treatment, most women are free of symptoms and do not require the pessary. Surgical correction is rarely indicated.

FIG. 11-6 Examples of pessaries. A, Smith. B, Hodge without support. C, Incontinence dish without support. D, Ring without support. E, Cube. F, Gellhorn. (Courtesy Milex Products, Inc., a division of CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT.)

Treatment for uterine prolapse depends on the degree of prolapse. Pessaries may be useful in mild prolapse. Estrogen therapy also may be used in the older woman to improve tissue tone. If these conservative treatments do not correct the problem, or if there is a significant degree of prolapse, abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy (see later discussion) is usually recommended (Lentz, 2007).

Mild to moderate urinary infections can be significantly decreased or relieved in many women by bladder training and pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises (Bersuk, 2007; Dumoulin & Hay-Smith, 2010). Other management strategies include pelvic flow support devices (i.e., pessaries), vaginal estrogen therapy, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, electrical stimulation, insertion of an artificial urethral sphincter, and surgery (e.g., anterior repair) (Tarnay & Bhatia, 2010).

Nursing care for women with urinary incontinence includes assessment for depression that can result from decreased quality of life and functional status. Women also may need guidance about changes in lifestyle (e.g., losing weight) and education about pelvic muscle exercises (Peterson, 2008; Sung, West, Hernandez, Wheeler, Myers, Subak, et al., 2009).

Treatment for a cystocele includes use of a vaginal pessary or surgical repair. Pessaries may not be effective. Anterior repair (colporrhaphy) is the usual surgical procedure and is commonly performed for large, symptomatic cystoceles. This involves a surgical shortening of pelvic muscles to provide better support for the bladder. An anterior repair is often combined with a vaginal hysterectomy. Kegel exercises may be beneficial for symptoms of urinary and fecal incontinence (Lentz, 2007).

Small rectoceles may not require treatment. The woman with mild symptoms may derive relief from a high-fiber diet and adequate fluid intake, stool softeners, or mild laxatives. Vaginal pessaries usually are not effective. Large rectoceles that are causing significant symptoms are usually repaired surgically. A posterior repair (colporrhaphy) is the usual procedure. This surgery is performed vaginally and involves shortening the pelvic muscles to provide better support for the rectum (Lentz, 2007). Anterior and posterior repairs may be performed at the same time and with a vaginal hysterectomy.

Management of genital fistulas depends on the location. Surgical repair is the usual treatment; however, it may not be successful.

Nursing care of the woman with a cystocele, rectocele, or fistula requires great sensitivity, because the woman’s reactions are often intense. She may become withdrawn or hostile because of embarrassment caused by odors and soiling of her clothing that are beyond her control. She may have concerns about engaging in sexual activities because her partner is repelled by these problems. The nurse can tactfully suggest hygiene practices that reduce odor. Commercial deodorizing douches are available, or noncommercial solutions, such as chlorine solution (1 teaspoon of household chlorine bleach to 1 quart of water) may be used. The chlorine solution also is useful for external perineal irrigation. Sitz baths and thorough washing of the genitals with unscented, mild soap and warm water help. Sparse dusting with deodorizing powders can be useful. If a rectovaginal fistula is present, enemas given before leaving the house may provide temporary relief from oozing of fecal material until corrective surgery is performed. Irritated skin and tissues may benefit from use of the heat lamp or application of an emollient ointment. Hygienic care is time consuming and may need to be repeated frequently throughout the day; protective pads or pants may have to be worn. All of these activities can be demoralizing to the woman and frustrating to her and her family. If surgical repair is performed, nursing care focuses on preventing infection and helping the woman avoid putting stress on the surgical site.

Benign Neoplasms

Benign neoplasms include a variety of nonmalignant cysts and tumors of the ovaries, the uterus, the vulva, and other organs of the reproductive system.

Ovarian Cysts

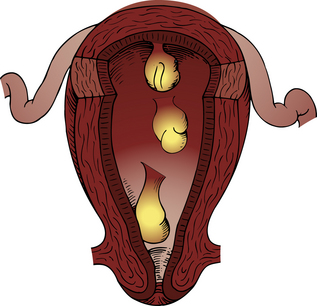

Functional ovarian cysts (Fig. 11-7) are dependent on hormonal influences associated with the menstrual cycle. These cysts may be classified as follicular cysts, corpus luteum cysts, theca-lutein cysts, endometrial cysts, and polycystic ovary syndrome. Other benign ovarian neoplasms include dermoid cysts and ovarian fibromas.

FIG. 11-7 Ovarian cyst. (From Seidel, H., Ball, J., Dains, J., Flynn, J., Solomon, B., & Stewart, R. [2011]. Mosby’s guide to physical examination [7th ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.)

Follicular Cysts

Follicular cysts develop most commonly in normal ovaries of young women as a result of the mature graafian follicle failing to rupture, or when an immature follicle does not resorb fluid after ovulation. A cyst is usually asymptomatic unless it ruptures, in which case it causes severe pelvic pain. If the cyst does not rupture, it usually shrinks after two or three menstrual cycles.

Corpus Luteum Cysts

Corpus luteum cysts occur after ovulation and are possibly caused by an increased secretion of progesterone that results in an increase of fluid in the corpus luteum. Clinical manifestations associated with a corpus luteum cyst include pain, tenderness over the ovary, delayed menses, and irregular or prolonged menstrual flow. A rupture can cause intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Corpus luteum cysts usually disappear without treatment within one or two menstrual cycles.

Theca-Lutein Cysts

Theca-lutein cysts are uncommon and in up to 50% of cases are associated with hydatidiform mole (see Chapter 28). Theca-lutein cysts develop as a result of prolonged stimulation of the ovaries by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). They also may occur if the woman has taken ovulation induction drugs; if she is pregnant and a large placenta is present, such as in the presence of a multiple gestation; or if the woman has diabetes (Katz, 2007). The cysts are almost always bilateral. A feeling of pelvic fullness may be noted by the woman if the ovary is enlarged, but most women are asymptomatic.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) occurs when an endocrine imbalance results in high levels of estrogen, testosterone, and luteinizing hormone (LH) and decreased secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone. This syndrome is associated with a variety of problems in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and with androgen-producing tumors. The condition can be transmitted as an X-linked dominant or autosomal dominant trait (Stein-Leventhal syndrome). Multiple follicular cysts develop on one or both ovaries and produce excess estrogen. The ovaries often double in size. Clinical manifestations include obesity, hirsutism (excessive hair growth), irregular menses or amenorrhea, and infertility. Impaired glucose tolerance and hyperinsulinemia occur in about 40% of women with PCOS (Lobo, 2007). Affected women are at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and possibly cardiovascular diseases (Benson, Hahn, Tan, Janssen, Schedlowski, & Elsenbruch, 2010). PCOS is often diagnosed in adolescence when menstrual irregularities and other symptoms appear (Lobo).

Collaborative Care

A variety of interventions may be implemented for the woman with a functional cyst. If expectant management is the treatment, the woman is advised to keep appointments for pelvic examinations to monitor the changes in size of the cyst (enlarging or shrinking). Pharmacologic interventions such as analgesics may be prescribed for pain management. Oral contraceptives may be ordered for several months to suppress ovulation for functional cysts. Large cysts (greater than 8 cm) or cysts that do not shrink may be removed surgically (cystectomy). Corpus luteum cysts are treated similarly. Theca-lutein cysts are usually managed conservatively (they usually regress) or by removal of the hydatidiform mole (Katz, 2007).

Nursing care focuses on educating the woman regarding treatment options as well as pain management with analgesics or comfort measures such as heat to the abdomen or relaxation techniques. If surgery is performed, the nurse provides preoperative and postoperative care. Discharge teaching includes signs of infection, postoperative incision care, the possibility of recurrence, and advice regarding follow-up appointments.

The treatment for PCOS depends on what symptoms are of greatest concern to the woman. Lifestyle modifications (e.g., losing weight) and management of presenting symptoms such as infertility, irregular menses, and hirsutism are the focus. Oral contraceptives (OCs) are the usual treatment for irregular menses, if pregnancy is not desired, because they inhibit LH and decrease testosterone levels. OCs can also lessen acne to some degree. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs may be used to treat hirsutism if oral contraceptives do not improve this condition. If pregnancy is desired, ovulation-inducing medications are given (Lobo, 2007). Metformin and other insulin medications for type 2 diabetes also are used to lower insulin, testosterone, and glucose levels, which in turn can reduce acne, hirsutism, abdominal obesity, amenorrhea, and other symptoms in women with PCOS (Lobo).

Nurses can provide information and counseling for women with PCOS. Information may be needed about the syndrome or about its long-term effects on the woman’s health. Research has shown that women report symptoms of psychologic distress including depression, anxiety, and social fears (Benson et al., 2010). Women may need to discuss their feelings about the physical manifestations of PCOS and may need emotional support if they have self-image problems related to the symptoms. Teaching about lifestyle modifications such as exercise and diet may be needed as well as education about the medications that are prescribed. Information about finding a support group or information on the Internet may be useful.

Other Benign Ovarian Cysts and Neoplasms

Two other ovarian neoplasms are dermoid cysts and ovarian fibromas. Dermoid cysts are germ cell tumors, usually occurring in childhood. These cysts contain substances such as hair, teeth, sebaceous secretions, and bones. Unless the cyst is large enough to put pressure on other organs, it is usually asymptomatic. Dermoid cysts may develop bilaterally and are often attached to the ovary. Treatment is usually surgical removal.

Ovarian fibromas are solid ovarian neoplasms developing from connective tissue and most often occurring after menopause. Fibromas range in size from small nodules to large masses weighing more than 23 kg. Most fibromas are unilateral. They are usually asymptomatic, but if large enough, they may cause ascites, feelings of pelvic pressure, or abdominal enlargement. Treatment is usually surgical removal.

Nursing care of women who have surgery for the removal of dermoid cysts and ovarian fibromas is similar to that described for functional ovarian cysts.

Uterine Polyps

Uterine polyps may be endometrial or cervical in origin. They are tumors that are on pedicles (stalks) arising from the mucosa (Fig. 11-8). The etiology is unknown, although they may develop in response to hormonal stimulus or be the result of inflammation. Polyps are the most common benign lesions of the cervix and endometrium that occur during the reproductive years. These polyps may be single or multiple. Endocervical polyps are most common in multiparous women older than 40 years. The woman may be asymptomatic or she may have premenstrual or postmenstrual bleeding or postcoital bleeding (Nelson & Gambone, 2010).

Collaborative Care

Clinical management of endometrial polyps is by surgical removal. Cervical polyps are usually removed in an office or clinic procedure without anesthesia. The polyp is grasped with a clamp and twisted or cut off. All polyps should be sent for pathologic examination. Endometrial sampling (which may require local anesthesia) should be done to determine if other pathologic conditions are present (Katz, 2007).

Nursing care includes preparing the woman for what to expect during the removal procedure and encouraging relaxation and breathing exercises and providing support during the procedure. After the procedure the woman is advised to avoid using tampons, sexual intercourse, and douching for up to 1 week or until the site is healed. She is taught how to identify signs of infection and to notify her health care provider if she experiences heavy bleeding (more than one pad in 1 hour).

Leiomyomas

Leiomyomas, also known as fibroid tumors, fibromas, myomas, or fibromyomas, are slow-growing benign tumors arising from the muscle tissue of the uterus (Nelson & Gambone, 2010). They are the most common benign tumors of the reproductive system, occurring most often after age 50 years. They tend to occur more often in African-American women and women who have never been pregnant (Nelson & Gambone). Fibroids also occur more often in women who are overweight (Katz, 2007). They rarely become malignant. Because their growth is influenced by ovarian hormones, these benign tumors can become quite large when the woman is pregnant or taking hormone therapy. They often spontaneously shrink after menopause when circulating ovarian hormones are diminished (Katz; Nelson & Gambone).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

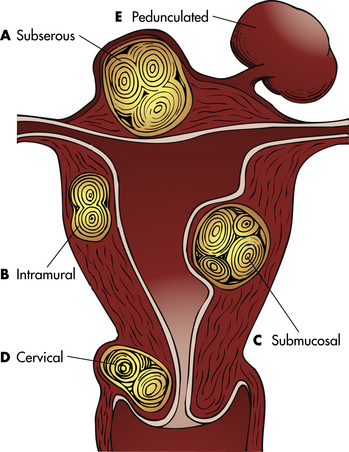

The cause of leiomyomas remains unknown, although genetic factors may be involved in their development. Most of the tumors are found in the body of the uterus. Leiomyomas are classified according to the location in the uterine wall. Subserous leiomyomas develop beneath the peritoneal surface of the uterus and appear as small or large masses that protrude from the outer uterine surface (Fig. 11-9, A). Intramural leiomyomas are tumors that develop within the wall of the uterus (see Fig. 11-9, B). Submucosal leiomyomas are the least common tumors, but often cause the most symptoms. These tumors develop in the endometrium and protrude into the uterine cavity (see Fig. 11-9, C). Leiomyomas can develop in the cervix and on the broad ligaments (see Fig. 11-9, D). They can grow on pedicles or stalks (see Fig. 11-9, E). Occasionally these break off the pedicle and attach to other tissues (become parasitic).

FIG. 11-9 Types of leiomyomas. A, Subserous. B, Intramural. C, Submucosal. D, Cervical. E, Pedunculated.

Most women are asymptomatic; abnormal uterine bleeding is the most common symptom of fibroids. If the tumor is very large, pelvic circulation may be compromised, and surrounding viscera may be displaced. A woman may complain of backache, low abdominal pressure, constipation, urinary incontinence, or dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation). Nausea and vomiting may occur if the tumor is obstructing the intestines. The woman also may notice an abdominal mass if the tumor is large. Anemia can occur if the woman has excessive bleeding. Pedunculated tumors can twist and become necrotic, causing pain.

The tumors appear to be influenced by the presence of estrogen. Fibroids can affect implantation and maintenance of pregnancy. During pregnancy, the tumors may produce complications such as preterm labor, miscarriage, or dystocia (difficult labor). The severity of the symptoms seems to be directly related to the size and location of the tumors.

Care Management

Knowledge of the medical-surgical management of leiomyomas is essential in planning nursing care. The knowledge enables the nurse to work collaboratively with other health care providers and to meet the woman’s informational and emotional needs. Clinical management for benign tumors of the uterus depends on the severity of the symptoms, the age of the woman, and her desire to preserve childbearing potential (see Nursing Process box: Woman with a Leiomyoma).

Medical Management

Medications: If symptoms are mild, regular checkups may suffice to observe for growth or changes in size. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be prescribed for pain; oral contraceptives inhibit ovulation and may relieve symptoms; and GnRH agonists such as leuprolide acetate (Lupron, Synarel) may be prescribed to reduce the size of the leiomyoma. Other medications used include medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera), danazol (Danocrine), mifepristone (Mifeprex), and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (e.g., raloxifene) (Katz, 2007; Nelson & Gambone, 2010; Wu, Chen, & Xie, 2007). The ideal medical therapy for treating fibroids has not been found, and research in this area continues (Sankaran & Manyonda, 2008).

The woman who prefers medical treatment will need information about the various medications, their actions and side

effects, and routes of administration. A woman who is receiving GnRH agonists to decrease the size of the fibroid must understand that regrowth will occur after the treatment is stopped. She also must know that a small loss in bone mass and changes in lipid levels can occur; therefore, long-term use is not recommended. Adding raloxifene to GnRH administration has been effective in preventing these effects in some premenopausal women (Nelson & Gambone, 2010; Sankaran & Manyonda, 2008). Amenorrhea may occur; however, women who wish to avoid pregnancy should use a nonhormonal or barrier method of contraception. A discussion of administration methods for GnRH agonists, including subcutaneous and intramuscular injections, intranasal administration, and subcutaneous implantation, will assist the woman in making a decision about her preferred method of administration (see Medication Guide, p. 205).

Uterine Artery Embolization: Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a treatment during which polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) pellets are injected into selected blood vessels to block the blood supply to the fibroid and cause shrinkage and resolution of symptoms (Katz, 2007). The procedure is done under local anesthesia and conscious sedation and can be done as an outpatient procedure, although some women will have the procedure in the hospital setting and remain overnight or be discharged within 4 to 6 hours (Katz; Pisco, Bilhim, Duarte, & Santos, 2009). An incision is made into the groin, and a catheter is threaded into the femoral artery to the uterine artery. An arteriogram identifies the vessels supplying the fibroid. Most fibroids are reduced in size by 50% within 3 months. Temporary amenorrhea or early menopause can occur in some women. Although symptom improvement occurs for most women, data are lacking about the effects on future fertility and pregnancy outcomes. Long-term effects of the procedure are unknown (Katz).

Preoperative teaching includes advising the woman not to drink alcohol or smoke and not to take aspirin or anticoagulant medications 24 hours before the procedure. If the procedure is done on an outpatient basis, the woman will usually need to take acid-suppressing medications, NSAIDs, and antihistaminic drugs as well as laxatives beginning the day before the procedure (Pisco et al., 2009). The woman is told to expect cramping during injection of the PVA pellets. Explanations about what to expect postoperatively include pelvic pain, fever, malaise, and nausea and vomiting that may be caused by acute fibroid degeneration. Pain can be controlled with NSAIDs or narcotic analgesics if needed. Postoperative nursing assessments include checking for bleeding in the groin, taking vital signs, assessing pain level, and checking the pedal pulse and neurovascular condition of the affected leg (Hiller, Miller, & Stavas, 2005). Discharge teaching includes signs of possible complications and when to notify the physician, self-care instructions, and follow-up advice (see Teaching for Self-Management box: Care after Uterine Artery Embolization).

Surgical Management

In addition to the surgical options of hysterectomy and myomectomy, other techniques have been developed to treat leiomyomas. These include laparoscopic techniques; hysteroscopic techniques; myolysis by heat, cold, and laser; and magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound surgery. Not all of these

techniques are suitable for every woman nor are all of them universally available to women (Istre, 2008).

Laser Surgery: Laser surgery or electrocauterization can be used to destroy small fibroids through a laparoscopic (abdominal) or hysteroscopic (vaginal) approach. Hysteroscopic uterine ablation (vaporization of tissues) can be performed under local or general anesthesia, usually as an outpatient procedure. Medical therapy using GnRH agonists to control bleeding temporarily and to suppress endometrial tissue may be given for 8 to 12 weeks before surgery. Although the uterus remains in place, the vaporization process can cause scarring and adhesions in the uterine cavity, affecting future fertility. Thus this procedure is for women who wish to retain their uterus but no longer desire childbearing potential (Nelson & Gambone, 2010). Risks of the procedure include uterine perforation, cervical injury, and fluid overload (caused by the leaking into blood vessels of fluid used to expand the uterus during surgery). The woman may experience postoperative cramping and a slight vaginal discharge for a few days. Before discharge the following information is given:

• Analgesics or NSAIDs can be used for pain relief as needed.

• Normal activities can be resumed within several days.

• Vaginal discharge is to be expected for 4 to 6 weeks.

• Use of tampons or vaginal intercourse should be avoided for 2 weeks.

• The next menstrual period may be irregular.

• The woman should be reminded about the effects of ablation on her fertility, if appropriate.

• The physician should be called if the woman has heavy bleeding or signs of infection.

Myomectomy: If the tumor is near the outer wall of the uterus, the uterine size is no larger than at 12 to 14 weeks of gestation, and symptoms are significant, myomectomy (removal of the tumor) may be performed (Katz, 2007). Myomectomy can be performed through a laparoscopic or abdominal incision approach or a vaginal (hysteroscopic) approach. Myomectomy leaves the uterine muscle walls relatively intact, thereby preserving the uterus and allowing the possibility of future pregnancies (Agdi & Tulandi, 2008). It is usually performed in the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle to avoid interrupting a possible pregnancy. GnRH therapy may be given before surgery to reduce the size of the fibroid. Fibroids can recur after myomectomy; further treatment may be needed (Nelson & Gambone, 2010).

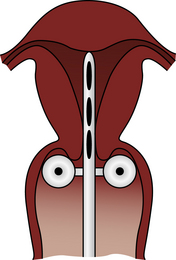

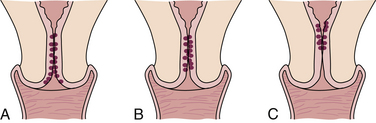

Hysterectomy: Hysterectomy (removal of the entire uterus) is the treatment of choice if bleeding is severe or if the fibroid is obstructing normal function of other organs. An abdominal or vaginal surgical approach depends on the size and location of the tumors. For example, abdominal hysterectomy is usually performed for leiomyomas larger than a uterus would be at 12 to 14 weeks of gestation or for multiple leiomyomas. The uterus is removed through either a vertical or transverse incision. In some circumstances the cervix is not removed. Vaginal approaches can be used for smaller tumors. In both abdominal and vaginal approaches, the uterus is removed from the supporting ligaments (broad, round, and uterosacral). These ligaments are then attached to the vaginal cuff, allowing maintenance of normal depth of the vagina (Fig. 11-10). Alternatives to these procedures are the laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) and the laparoscopic assisted supracervical hysterectomy (LASH). LAVH converts an abdominal procedure to a vaginal one by using a laparoscope in the abdomen to assist with removal of the uterus. LASH allows the cervix to remain. Both are associated with a quicker recovery and fewer postoperative complications (Mueller, Renner, Haeberle, Lermann, Oppelt, Beckemann, & Thiel, 2009; Nieboer, Johnson, Lethaby, Tavender, Curr, Garry, et al., 2009).

Preoperative Care: Assessments needed before surgery include the woman’s knowledge of treatment options, her desire for future fertility if she is premenopausal, the benefits and risks of each procedure, preoperative and postoperative procedures (Boxes 11-1 and 11-2), and the recovery process (Askew, 2009). If the woman demonstrates understanding of this information, she can make an informed decision about treatment and feel a sense of control over the surgical experience. Resources on helping women to make decisions about treatment can be found at the website for the Fibroid Treatment Collective at www.fibroid.org.

Psychologic assessment is essential, particularly for a woman who is scheduled for a hysterectomy. Areas to be explored include the significance of the loss of the uterus for the woman, misconceptions about effects of surgery, and adequacy of her support system. Women who have not completed their childbearing, who believe that their self-concept is related to having a uterus (to be a complete woman), who feel that sexual functioning is related to having a uterus, or who have too little or too much anxiety about the surgery may be at risk for postoperative emotional reactions (Leppert, Legro, & Kjerulff, 2007). Yen and associates (2008) found that postoperatively most women reported positive feelings about femininity and their body image, less anxiety and depression, but still reported a worsening of sexual functioning.

Postoperative Care: Postoperative assessments and care after myomectomy and abdominal hysterectomy are similar to those for other abdominal surgery (Box 11-3). Assessments specific to abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy include assessment for vaginal bleeding (one perineal pad saturated in less than 1 hour is excessive), urinary retention (especially after vaginal hysterectomy), perineal pain after vaginal hysterectomy, and psychologic assessments (e.g, depression) (Leppert et al., 2007; Yen, Chen, Long, Chang, Yen, & Ko, 2008).

Discharge Planning and Teaching: Discharge planning and teaching are similar for myomectomy and hysterectomy (see Teaching for Self-Management box: Care After Myomectomy or Hysterectomy). Myomectomy and vaginal hysterectomy may be performed in an ambulatory setting, and women may be discharged the evening of the surgery. Women who have an abdominal hysterectomy may have a 1- to 2-day stay in the hospital before being discharged.

If a hysterectomy was performed, the woman is reminded that she will experience cessation of menses. If the woman is premenopausal, she will not experience menopause at this time unless her ovaries also were removed. In this case there will be no reason for her to consider hormone replacement therapy. If the ovaries are removed, the woman will need the most current information on the risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy (see Chapter 6). Other symptoms she may experience include pain, sleep disturbance, fatigue, anxiety, and depression.

Vaginal intercourse may be uncomfortable at first, especially after vaginal procedures. Use of water-soluble lubricants, relaxation exercises, and positions that control penile penetration may be beneficial (Katz, 2007). Women can be assured that this discomfort will decrease over time.

The schedule for follow-up care depends on the procedure performed, but usually a postoperative visit is scheduled within a week. Vaginal screening with cytology/Papanicolaou (Pap) test after total hysterectomy for a nonmalignant reason is not recommended (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2010a); however, vaginal cancer can occur after hysterectomy and health care providers may continue to recommend Pap screening to assess for vaginal cancer (Slomovitz & Coleman, 2007).

Vulvar Problems

Bartholin cysts are the most common benign lesions of the vulva. They arise from obstruction of the Bartholin duct, which causes it to enlarge. Small cysts often are asymptomatic; however, large cysts or infected cysts cause symptoms such as vulvar pain, dyspareunia (painful intercourse), and a feeling of a mass in the vulvar area (Eckert & Lentz, 2007).

Collaborative Care: If the woman is asymptomatic no treatment is necessary. If the cyst is symptomatic or infected, surgical incision and drainage may provide temporary relief. Cysts tend to recur; therefore, a permanent opening for drainage may be recommended. This procedure is called marsupialization and is the formation of a new duct opening for drainage (Eckert & Lentz, 2007).

Nursing care after surgery includes teaching the woman about pain-relief measures such as sitz baths, heat lamps to the perineum, and use of analgesics. The woman is taught to assess the incision site for signs of healing and infection and to take antibiotics, if prescribed, for prevention of infection.

Vulvodynia

Vulvar pain is a common gynecologic problem. Vulvodynia, also called vulvar pain syndrome or vulvovestibulitis, is reportedly experienced by 4% to 27% of women. The incidence is thought to be the same for women of all races and ethnicities (Kingdon, 2009).

Vulvodynia is a complex condition thought to be a chronic pain disorder of the vulvar area. The term vulvodynia is used if pain is present with no visible abnormality or no identified neurologic diagnosis (Katz, 2007). Pain can be described as provoked (e.g., by inserting a tampon or having vaginal intercourse) or unprovoked and localized to the vestibule or generalized over the vulvar area (Kingdon, 2009).

Etiology has not been established although psychologic and biologic theories have been proposed. The most common theory is that vulvodynia is caused by a chronic neuropathic pain syndrome. Inflammation may also be a causative factor and continues to be investigated. (Zolnoun, Hartmann, Lamvu, As-Saine, Maixner, & Steege, 2006). Past sexual and emotional experiences and personality traits are being investigated as causes because they can influence the perception and interpretation of nerve impulses (Kingdon, 2009).

A feature of neuropathic pain is allodynia, which is a painful sensation that is from something not supposed to be painful. It commonly occurs in women with vulvodynia. Several triggers that reportedly cause allodynia in the vulvar area include use of oral contraceptives; presence of candidiasis or human papillomavirus; wearing tight-fitting underwear and pants, especially synthetic materials; being a victim of childhood sexual abuse; and using chemical irritants such as scented detergents, soaps, and bubble baths (Arnold, Bachmann, Rosen, & Rhoads, 2007; Goldstein & Burrows, 2008; Harlow, Vitonis, & Stewart, 2008). However, with all these triggers, research evidence is conflicting and the need for scientific evidence is ongoing.

Collaborative Care: Assessment of a woman with possible vulvodynia includes a health history including a mental health history, specifically inquiring about anxiety or depression. A thorough pain assessment is essential. Questions about provoking and palliative factors, the quality of pain, radiation of the pain, strength of the pain and the timing of pain occurrence are included. A history may elicit complaints about burning, stinging or irritation in the vulvar area, and reports of how the woman feels her symptoms affect her physical activities and ability for sexual intimacy.

A thorough pelvic examination is recommended to rule out other causes of pain such as infection or trauma. The vulva should be inspected for erythema, ulcerations, and hyperpigmentation (Goldstein & Burrows, 2008; Katz, 2007). A cotton swab is used to identify areas of pain on pressure to confirm presence of allodynia. A systematic assessment (e.g., using positions of the face of a clock) is suggested, and ratings of pain should be rated as mild, moderate, or severe. Reed (2006) suggests the indentation of the swab be about 5 cm. A speculum examination (a pediatric size is recommended) is used to examine the vagina for redness, erosions, and dryness. A swab of vaginal secretions is obtained and can be tested for yeast, increased white blood cells, and pH. Cultures for Candida and bacteria can be obtained. A bimanual examination may be performed (Katz; Reed).

Management strategies are individualized to the woman. Often a series of therapies or a combination of therapies will be implemented to find the best treatment. Currently there is little evidence to support one therapy over another. Oral medications include gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants (Harris, Horowitz, & Bordiga, 2007; Katz, 2007; Reed, Caron, Gorenflo, & Haefner, 2006). Topical therapies include the use of lidocaine 5% ointment that can be applied nightly or prophylactically (i.e., before sexual intercourse) (Katz, 2007).

Other therapeutic measures that have been tried and are reportedly helpful for symptoms include pelvic floor exercises, biofeedback, vaginal dilator training, hypnosis, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (Hartmann, Strauhal, & Nelson, 2007; Munday, Buchan, Ravenhill, Wiggs, & Brooks, 2007; Katz, 2007; Pukall, Kandyba, Amsel, Khalifé, & Binik, 2007). ![]()

Hygienic measures suggested for women with vulvodynia include wearing white cotton underwear, using 100% cotton menstrual pads, using soaps and detergents for sensitive skin, avoiding wearing tight clothing over the vulvar area, avoiding lubricants that contain propylene glycol, and using natural oils such as olive oil for lubricants (Kingdon, 2009).

Surgery is usually not recommended until other measures have proven to be ineffective. The surgical procedure is a vestibulectomy, a difficult procedure that removes the vestibule and hymen and has a high rate of complications (Katz, 2007). Research by Bergeron, Khalife, Glazer, & Binik (2008) found this procedure to be no more effective than less invasive measure such as biofeedback.

Client information about vulvodynia including how to locate support groups is available on various websites including:

• International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease: www.issvd.org

• National Vulvodynia Association: www.nva.org

• Vulvar Pain Society: www.vulvarpainsociety.org

Nurses can recommend these websites to women who want more information about vulvodynia. Nurses also need to keep current on the latest research so that care can be evidence based.

Malignant Neoplasms

Malignant neoplasms of the reproductive system include cancers of the endometrium, the cervix, the ovary, the vulva, the vagina, and the uterine tubes. In 2010 an estimated 83,750 women in the United States were diagnosed with a gynecologic cancer; an estimated 27,710 died (ACS, 2010a). Overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk for developing many cancers, including cancers of the endometrium, ovary, and cervix. Evidence also suggests that being overweight increases the risk for cancer recurrence and decreases the likelihood of survival for these cancers (ACS).

Cancer of the Endometrium

Endometrial cancer is the most common malignancy of the reproductive system (ACS, 2010a). It is most commonly seen in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women between ages 50 and 65. Certain risk factors have been associated with the development of endometrial cancer, including obesity, nulliparity, infertility, late onset of menopause, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, PCOS, and family history of ovarian or breast disease (ACS; Creasman, 2007a). There appears to be an increase in risk for endometrial cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Hormone imbalance, however, seems to be the most significant risk factor (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2008). Numerous studies have correlated the use of exogenous estrogens (unopposed stimulation, i.e., absence of progesterone) in postmenopausal women with an increased incidence of uterine cancer. Tamoxifen taken by women for breast cancer also has been related to a slight increase in endometrial cancer (Creasman). Pregnancy and use of low-dose oral contraceptive pills appear to offer some protection (ACS). The incidence of endometrial cancer among Caucasian women is higher than that among African-American and Hispanic women; however, the mortality rates are more than one and one half times higher in African-American women (Ries, Melbert, Krapcho, Stinchcomb, Howlader, Horner, et al., 2008).

Endometrial cancer is slow growing and for that reason has a good prognosis if diagnosed at a localized stage. Most endometrial cancers are adenocarcinomas that develop from endometrial hyperplasia. The tumor usually develops in the fundus of the uterus and can spread directly to the myometrium and cervix, as well as to other reproductive organs. Metastasis (spread of cancer from its original site) is through the lymphatic system in the pelvis and through the blood to the liver, the lungs, and the brain.

Care Management

Assessment and Nursing Diagnoses

Assessment includes a history of physical symptoms. The cardinal sign of endometrial cancer is abnormal uterine bleeding (e.g., postmenopausal bleeding and premenopausal recurrent metrorrhagia). Thirty percent of postmenopausal bleeding is caused by carcinoma. Late signs include a mucosanguineous vaginal discharge, low back pain, or low pelvic pain. A pelvic examination may reveal the presence of a uterine enlargement or mass.

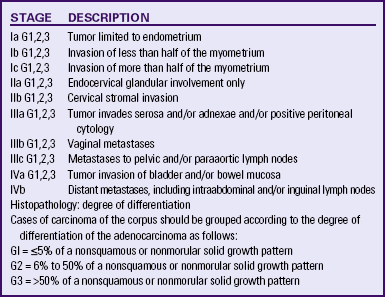

Histologic examination is used for diagnosis. A Pap smear of cellular material obtained by aspiration of the endocervix will identify only one third to one half of cases. Fractional curettage or endometrial biopsy yields the most accurate results. Fractional curettage involves scraping the endocervix and endometrium for histologic evaluation to determine the grade of neoplasm and its stage (extent). Perforation of the uterus is a possible complication of this procedure. Endometrial biopsy will identify about 90% of cases (Creasman, 2007a; Hacker, 2010a). It is usually done on an outpatient basis under local anesthesia. A suction-type curette is used to remove tissue for sampling. It is recommended that women at risk for HNPCC have an annual biopsy beginning at age 35 years (ACS, 2010a). Other diagnostic tests that may be useful include hysteroscopy (examination of the uterus through an endoscope) and vaginal ultrasonography. Tests to determine the spread of cancer include liver function tests, renal function tests, chest x-ray, intravenous pyelography (IVP), barium enema, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scans, and biopsy of suggestive tissues. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification system is used to describe the stages of endometrial carcinoma (Table 11-1).

TABLE 11-1

FIGO CLASSIFICATION OF ENDOMETRIAL CARCINOMA∗

∗Approved by FIGO, October 1988, Rio de Janeiro.

Source: Creasman, W. (2007a). Adenocarcinoma of the uterus. In P. DiSaia & W. Creasman (Eds.), Clinical gynecologic oncology (7th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Possible nursing diagnoses that would apply to a woman with endometrial cancer include the following:

• Deficient knowledge related to:

• Decisional conflict related to:

• Impaired skin integrity related to:

• Acute or chronic pain related to:

Expected Outcomes of Care

Planning for care of the woman with endometrial cancer depends on the stage of cancer and the treatment selected. Examples of expected outcomes are that the woman will do the following:

• Demonstrate understanding of her diagnosis of endometrial cancer, the treatments available, and her prognosis.

• Make informed decisions about treatment options.

• Describe a decrease in anxiety and fear.

• Report that pain is reduced or manageable.

• Experience no skin breakdown or infection related to treatment.

• State that she understands the effects of cancer and treatment on her body image and that her concerns are reduced.

• Report that she and her partner expect to be able to resume mutually satisfying sexual relations after treatment.

Plan of Care and Interventions

Therapeutic Management: Collaborative efforts from various health disciplines are needed to work with the woman with endometrial cancer. All must have an understanding of the treatments that may be used.

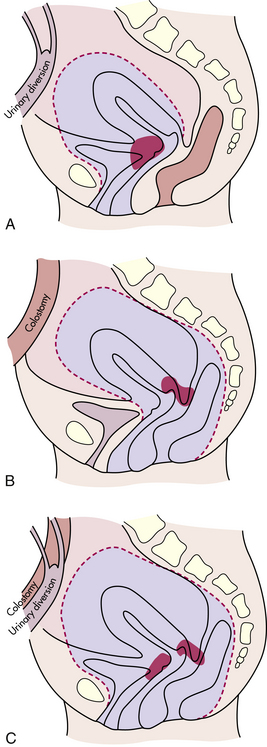

For stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium limited to the uterus, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is the usual treatment (Creasman, 2007a). Radiation use in stage I continues to be studied; it can reduce the risk of recurrence, but evidence does not demonstrate improved survival rates or reduce metastasis to distant sites. It can be used when the woman is a poor surgical risk (Lu & Slomovitz, 2007). A radical hysterectomy (abdominal hysterectomy with wide excision of parametrial tissue laterally and uterosacral ligaments posteriorly), BSO, and pelvic node dissection usually are performed for stage II endometrial cancer. If nodes are positive or if there is extensive uterine disease or metastasis outside the uterus, external pelvic radiation (see p. 257) is usually done postoperatively. Internal radiation therapy or brachytherapy (placement of an applicator loaded with a radiation source into the uterine cavity) (see p. 258) also may be used before surgery or combined with external radiation (Lu & Slomovitz). Treatment of advanced stages is individualized but usually includes a TAH-BSO plus chemotherapy or radiation, or both (Hacker, 2010a).

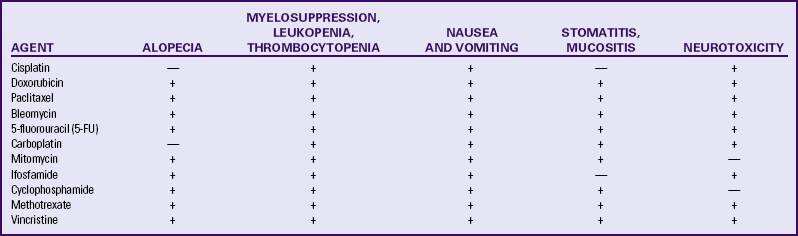

Chemotherapy is used to treat advanced and recurrent disease, although no effective treatment regimen has been established (Lu & Slomovitz, 2007). Agents that have been somewhat effective include cisplatin, doxorubicin, carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, and paclitaxel (Lu & Slomovitz). Chemotherapy may cause hair loss, anemia, and bone marrow depression, as well as other side effects (Table 11-2).

TABLE 11-2

Common Side Effects of Chemotherapy Agents Used for Gynecologic Cancers∗

∗Incidence and seriousness of side effects may be dose related.

Sources: Chu, C., & Rubin, S. (2007). Basic principles of chemotherapy. In P. DiSaia & W. Creasman (Eds.), Clinical gynecologic oncology (7th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby; Facts and Comparisons. (2009). Drug facts and comparisons. St Louis: Wolters Kluwer; Kunos, C., & Waggoner, S. (2007). Principles of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in gynecologic cancer. In V. Katz, G., Lentz, R. Lobo, & D. Gershenson (Eds.), Comprehensive gynecology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby.

Progestational therapy—use of medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) and megestrol (Megace)—may be effective for recurrent cancers, especially those that are estrogen receptor positive. These drugs usually do not cause acute side effects. Tamoxifen and raloxifene (see Medication Guide on pp. 226-227) are antiestrogens that have shown some effectiveness against recurrent endometrial cancer (Creasman, 2007a; Lu & Slomovitz, 2007).

Nursing Management: Nursing care is individualized to the woman and her specific situation and diagnosis. Interventions for the woman having surgery are directed by assessment of her perception of the anticipated surgery, her knowledge of what to expect after surgery, and any preoperative special procedures, such as cleansing enemas or douches. In today’s practice of short hospital stays even for radical surgery, many of these preoperative procedures are performed at home before admission, so assessment of understanding becomes a critical nursing

action (see Cultural Considerations box). Nursing care for the woman having a TAH-BSO will be similar to that care for a woman having a hysterectomy for leiomyoma described earlier. The following section focuses on care of the woman having a radical hysterectomy.

Preoperative Care: The nurse working with the woman preparing for a radical hysterectomy and pelvic node dissection should explain any preoperative procedures to be done (see Box 11-2). Additional teaching is needed for the woman having a radical hysterectomy regarding possible postsurgical events (e.g., a suprapubic drain often remains in place for several days to a week).

Postoperative Care: Assessment of vital signs usually follows a postanesthesia protocol, gradually decreasing in frequency to two to four times a day. Intravenous fluids are maintained at a rate rapid enough to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance and are usually discontinued when the woman is taking oral fluids well and has no elevated temperature. A regular diet is resumed as tolerated. Intake and output are monitored. The Foley catheter is usually removed the morning after surgery and the first few voidings are measured.

The woman should turn and take deep breaths with assistance as needed. Breath sounds are assessed, and any deviations from normal are reported immediately. The most significant single cause of morbidity and prolonged hospitalization after major procedures is respiratory complications. Anesthesia and surgery alter breathing patterns and ability to cough. Atelectasis, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolus may occur.

To promote venous return and prevent deep vein thrombosis, the woman may wear antiembolic stockings or wear pneumonic pressure devices (i.e., boots) while she is in bed (Chard, 2010). Leg exercises and early ambulation are beneficial. Most women are encouraged to get out of bed the evening of or the day after surgery. Assistance in getting up and walking may be needed.

Hemorrhage is always a possible complication after surgery. The wound drainage tube is emptied as needed or every 4 hours, and the amount and character of drainage are recorded. Drainage from any tube is assessed for bleeding. Vaginal drainage, if any, should be serosanguineous. Hematuria is noted and recorded. The primary health care provider is kept apprised of any deviations from normal expectations.

Paralytic ileus may occur after surgery in which the intestines have been manipulated. Use of a nasogastric tube, limiting oral fluids, and early ambulation all support the return of gastrointestinal function. An enema or suppository may bring relief of flatus and stimulate the return of bowel function. Oral laxatives should not be given until lower bowel function has returned.

Narcotic analgesics and NSAIDs are used for postoperative pain. Patient-controlled analgesia pumps are commonly used to deliver the narcotic medications (Lowdermilk, 2008). Nursing measures such as massages, repositioning, and emotional support are all helpful adjuncts to pharmacologic control of discomfort.

Because the in-hospital convalescent period is generally short, close observation by the nurse and attention to detail are critical. Nursing actions appropriate to this period include monitoring for urinary retention after the catheter is removed, monitoring the woman’s appetite and diet, monitoring bowel function, and encouraging progressive ambulation and self-care.

Discharge Planning and Teaching: Discharge planning and teaching are done throughout the preoperative and postoperative phases and culminate during the convalescent phase. Discharge teaching topics for the woman with a radical hysterectomy are similar to those that can be found in the Teaching for Self-Management box: Care After Myomectomy or Hysterectomy (see also Nursing Care Plan: Hysterectomy for Endometrial Cancer).

Care for the woman who has had external or internal radiation therapy is the same as that described for the woman with cervical cancer (see later discussion).

Nursing care for the woman undergoing chemotherapy will depend on the type of drug given. If alopecia is likely, the nurse can suggest wigs, scarves, or other kinds of head coverings. If the therapy affects the appetite or causes gastrointestinal side effects, suggestions such as those in Box 11-4 may be useful.

After discharge the woman may require continued nursing care or monitoring of her physical status or advice for management of effects of treatment or the cancer. The family is likely to have to provide much of the woman’s care. Nurses must identify what families see as their greatest need so that interventions are planned that best use the family’s resources.

Psychologic care for the woman with endometrial cancer is essential. A women needs to be able to discuss her concerns about having cancer and the potential for recurrence. She may have fears of death; permanent disfigurement and change in functioning; altered feelings of self as a woman; and concerns regarding her femininity, sexuality, and loss of reproductive capacity. She may have questions arising from things she has heard about posthysterectomy changes, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy. Significant others should be encouraged to express their questions and concerns as well. The woman and her significant others may benefit from a referral to a community cancer support group (see the ACS website, www.cancer.org).

Evaluation

The nursing care of a woman with endometrial cancer is evaluated by using the expected outcomes and measurable criteria to ascertain the degree to which the outcomes were met.

Incidence and Etiology

Cancer of the ovary is the second most frequently occurring reproductive cancer and causes more deaths than any other female genital tract cancer (ACS, 2010a). Because the symptoms of this type of cancer are vague and definitive screening tests do not exist, ovarian cancer is often diagnosed in an advanced stage. The 5-year survival rate for cancer diagnosed at a localized stage is about 94%; however, only about 15% of all ovarian cancers are found at this stage. For advanced stages, the rate is about 28% (ACS). Malignant neoplasia of the ovaries occurs at all ages, including in infants and children. However, cancer of the ovary is seen primarily in women older than age 50 with the greatest number of cases found in women ages 60 to 64 years (Copeland, 2007).

Major histologic cell types occur in different age-groups, with malignant germ cell tumors most common in women between 20 and 40 years of age and epithelial cancers occurring in the perimenopausal age-groups. The spread of ovarian cancer is by

direct extension to adjacent organs, but distal spread can occur through lymphatic spread to the liver and the lungs.

The cause of ovarian cancer is unknown; however, a number of risk factors have been identified. These factors include nulliparity, infertility, previous breast cancer, family history of ovarian or breast cancer, and history of HNPCC. Inherited BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations increase the risk, but 90% of women do not have inherited ovarian cancer (Coleman & Gershenson, 2007; Copeland, 2007). Women of North American or northern European descent have the highest incidence of ovarian cancers. Pregnancy and use of oral contraceptives seem to have some protective benefits against ovarian cancer, whereas use of postmenopausal estrogen may increase the risk (ACS, 2010a). Genital exposure to talc, a diet high in fat, lactose intolerance, and use of fertility drugs have been suggested as risk factors, but research findings are inconclusive (Berek, 2010; Coleman & Gershenson; Copeland).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Ovarian cancer has been called a silent disease because early warning symptoms that would send a woman to her health care provider are absent (e.g., no bleeding or other discharge and no pain). Abdominal bloating, noticeable increase in abdominal girth, pelvic or abdominal pain, difficulty eating or feeling full quickly, and urinary urgency or frequency have been identified as the four most common symptoms of early ovarian cancer (Goff, Mandel, Drescher, Urban, Gough, Schurman, et al., 2007). The increase in abdominal girth (caused by ovarian enlargement or ascites) is usually attributed to an increase in weight or a shift in weight that is seen commonly in women entering their middle years. An ovary enlarged 5 cm or more than normal that is found during routine examination requires careful diagnostic workup. Pelvic pain, anemia, and general weakness and malnutrition are signs of late-stage disease.

Early diagnosis of ovarian cancer is uncommon. Attempts at early detection have not proven to be reliable. Taking a family history is important because it may reveal cancer of the uterus or breast. Transvaginal ultrasound, CA-125 antigen (a tumor-associated antigen) testing, and frequent pelvic examinations have all been used without a great deal of success because these tests do not have high levels of sensitivity and specificity (Fields & Chevlen, 2006). Research continues on the use of proteomics (study of proteins in blood) to identify ovarian cancer in its earlier stages (ACS, 2010a; Cesario, 2010). Emerging technology includes tumor cell profiling and nanotechnology (use of microchips to sense biomarkers that are unique to a specific cancer).

Transvaginal ultrasound and CA-125 screening currently are not recommended for routine screening in the general population but are recommended for women who are at high risk (e.g., BRCA1 mutation carriers) (ACS, 2010a). Routine pelvic examination continues to be the only practical screening method for detecting early disease, even though few cancers are detected in women without symptoms. Any ovarian enlargement should be considered highly suggestive and needs further evaluation by laparoscopy or laparotomy. Responsibility for diagnosis rests with the pathologist. The size of the tumor is not indicative of the severity of disease. Clinical staging is done surgically and gives direction to treatment and prognosis (Copeland, 2007).

Therapeutic Management

Treatment is dictated by the stage of the disease at the time of initial diagnosis. Surgical removal of as much of the tumor as possible is the first step in therapy. This may involve just the removal of one ovary and tube or the radical excision of the uterus, ovaries, tubes, and omentum. Cytoreductive surgery (the debulking of the poorly vascularized larger tumors) also is done. The smaller the volume of tumor remaining, the better the response to adjuvant therapy. Because about three fourths of women are in stage II, III, or IV disease at the time of diagnosis, surgical cure is not possible; therefore, after tumor reduction surgery is performed, women with epithelial cell carcinoma will receive chemotherapy.

A combination of antineoplastic drugs such as paclitaxel and cisplatin or carboplatin and paclitaxel is recommended for most women with advanced disease. Women being treated with chemotherapy are followed up closely with laboratory and radiologic tests and CA-125 levels to monitor their response to the therapy (Copeland, 2007).

Second-look surgery is a technique used to determine the response of the disease to chemotherapy and to determine whether treatment should be continued; however, this procedure usually is not done unless it is part of a research protocol (Copeland, 2007).

Radiation has been used to treat early-stage disease, and some women have had long-term survival after debulking surgery followed by radiation therapy. It has also been used as a palliative measure in advanced disease (Coleman & Gershenson, 2007).

Nursing Implications

Lockwood-Rayermann, Donovan, Rambo, and Kuo (2009) reported on data analyzed from a survey conducted by the National Ovarian Cancer Coalition. These researchers concluded that awareness of the symptoms of and risk factors for ovarian cancer are low in the general population. Therefore, nurses need to be involved in raising the awareness of these risks and symptoms with the public and with women who are seeking care in health care settings such as clinics and physician offices (Cesario, 2010).

Goff and associates (2007) developed a symptom index to be used in identifying women at risk for ovarian cancer who might benefit from early screening. The index includes asking about symptoms (pelvic/abdominal pain, urinary urgency/frequency, increased abdominal size/bloating, and difficulty eating/feeling full) and the frequency and duration of the symptoms. The index is considered positive if any of the symptoms occurred more than 12 times per month and had been present for less than 1 year. Nursing can incorporate asking about these symptoms when women are seen for annual examinations or other gynecologic health visits and encouraging women to keep a symptom diary (Cesario, 2010).

The woman diagnosed with ovarian cancer has concerns similar to those described for the woman with endometrial and cervical cancer. Nursing interventions for the woman having surgery, chemotherapy, or external radiation therapy are described in other sections of this chapter.

Women with advanced ovarian cancer have a significant rate of recurrence. Follow-up for 5 years must be intensive. When a cure or remission cannot be achieved, palliative measures are initiated that alleviate symptoms of the progressing disease and provide comfort and maximal function. As the disease progresses, nutritional support, including enteral feedings and parenteral hyperalimentation, may be needed because of the effects on the gastrointestinal tract of both the disease and the treatments. The goal of nursing care is assisting the woman to maintain quality of life and to remain at home with her family as much as possible.

Because the period between a focus on cure and a focus on palliation is often prolonged, the woman with ovarian cancer is apt to experience most of the grief stages described by Kübler-Ross and to need support and encouragement through each stage. After diagnosis the woman often experiences denial and then anger. As treatment begins, she may “bargain” for a cure. If treatment is successful and death is forestalled by remission or cure, the process of adjustment to dying ceases, and the woman again focuses on life and its challenges. When treatment fails to secure a cure or remission ends, the woman must turn again to the task of adjustment (see Legal Tip).

Family and friends also have diverse feelings. When grieving is prolonged, as it often is when the woman has cancer, the stress can be enormous and can interfere with other interpersonal relationships. If the woman is hospitalized, the environment may further intrude on relationships, limiting privacy and access to the woman and hindering opportunities for caring gestures. The nurse can assist the woman and her family to share their feelings with each other and help them to develop a support network. Referral to a cancer support group may be useful (see National Ovarian Cancer Coalition, www.ovarian.org).

Cancer of the Cervix

Cancer of the cervix is the third most common reproductive cancer. The accessible location of the cervix to both cell and tissue study and direct examination have led to a refinement of diagnostic techniques, contributing to improved diagnosis and management of these disorders. The incidence of invasive cancer has decreased over the last 30 years, reducing mortality rates. However, the incidence of preinvasive cancer has increased, and more women in their 20s and 30s are being diagnosed with preinvasive cervical lesions (ACS, 2010a).

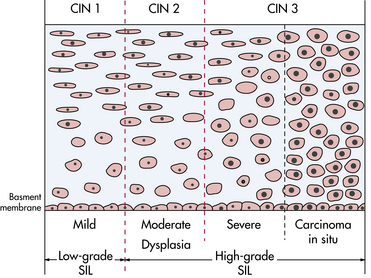

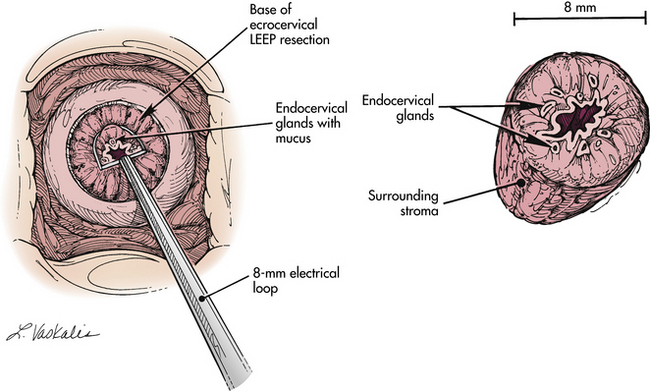

Cancer of the cervix begins as neoplastic changes in the cervical epithelium. Terms that have been used to describe these epithelial changes or preinvasive lesions include dysplasia and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN); CIN is the term currently used. CIN 1 refers to abnormal cellular proliferation in the lower one third of the epithelium; this change tends to be self-limiting and generally regresses to normal. CIN 2 involves the lower two thirds of the epithelium and may progress to carcinoma in situ. CIN 3 involves the full thickness of the epithelium and often progresses to carcinoma in situ. Carcinoma in situ (CIS) is diagnosed when the full thickness of epithelium is replaced with abnormal cells (Creasman, 2007b) (Fig. 11-11). Terms used to describe neoplastic changes in abnormal cervical cytology reports are low-grade and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (SILs); however, CIN continues to be a common term used in clinical practice.

Preinvasive lesions are limited to the cervix and usually originate in the squamocolumnar junction or transformation zone (Fig. 11-12). Intensive study of the cervix and the cellular changes that take place has shown that most cervical tumors have a gradual onset rather than an explosive one. Preinvasive conditions may exist for years before the development of invasive disease. These preinvasive conditions are highly treatable in many cases.

FIG. 11-12 Location of squamocolumnar junction according to age. The location where the endocervical glands meet the squamous epithelium becomes progressively higher with age. A, Puberty. B, Reproductive years. C, Postmenopausal.

Invasive carcinoma is the diagnosis when abnormal cells penetrate the basement membrane and invade the stroma. There are two types of invasive carcinoma of the cervix: microinvasive and invasive. Microinvasive carcinoma is defined as one or more lesions that penetrate no more than 3 mm into the stroma below the basement membrane with no areas of lymphatic or vascular invasion (Creasman, 2007b). Invasive carcinoma describes invasion that goes beyond these parameters. The staging of invasive carcinoma extends from stage 0 (CIS) to stage IVb (distant metastasis or disease outside the true pelvis). A number of substages within each stage also exist. Clinical stages for cancer of the cervix are shown in Table 11-3.

TABLE 11-3

FIGO Classification of Cervical Carcinoma

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

| 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinoma |

| I | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus should be disregarded) |

| Ia | Invasive cancer identified only microscopically; all gross lesions, even with superficial invasion, are stage Ib cancers. Invasion is limited to measured stromal invasion with maximum depth of 5 mm and no wider than 7 mm |

| Ia1 | Measured invasion of stroma 3 mm in depth and no wider than 7 mm |

| Ia2 | Measured invasion of stroma >3 mm and 5 mm in depth and no wider than 7 mm. |

| The depth of invasion should not be >5 mm taken from the base of the epithelium, surface or glandular, from which it originates. Vascular space involvement, venous or lymphatic, should not alter the staging | |

| Ib | Clinical lesions confined to the cervix or preclinical lesions greater than stage Ia |

| Ib1 | Clinical lesions 4 cm or less |

| Ib2 | Clinical lesions >4 cm |

| II | Involvement of the vagina but not the lower third, or infiltration of the parametria but not out to the side wall |

| IIa | Involvement of the vagina, but no evidence of parametrial involvement |

| IIb | Infiltration of the parametria, but not out to the side wall |

| III | Involvement of the lower third of the vagina or extension to the pelvic side wall. All cases with a hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney should be included, unless they are known to be attributable to other cause |

| IIIa | Involvement of the lower third of the vagina but not out to the pelvic side wall if the parametria are involved |

| IIIb | Extension onto the pelvic side wall and/or hydronephrosis or nonfunctional kidney |

| IV | Extension outside the reproductive tract |

| IVa | Involvement of the mucosa of the bladder or the rectum |

| IVb | Distant metastasis or disease outside the true pelvis |

Source: Monk, B., & Tewari, K. (2007). Invasive cervical cancer. In P. DiSaia & W. Creasman (Eds.), Clinical gynecologic oncology (7th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

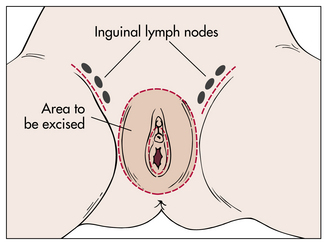

Approximately 90% of cervical malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas; 10% are adenocarcinomas. Squamous cell carcinomas can spread by direct extension to the vaginal mucosa, the pelvic wall, the bowels, and the bladder. Metastasis usually occurs in the pelvis, but it can occur to the lungs and the brain through the lymphatic system.