Postpartum Complications

• Identify the causes, signs and symptoms, and medical and nursing management of postpartum hemorrhage.

• Describe hemorrhagic shock as a complication of postpartum hemorrhage including management and hazards of therapy.

• Differentiate the causes of postpartum infection.

• Summarize assessment and care of women with postpartum infection.

• Describe thromboembolic disorders, including incidence, etiology, signs and symptoms, and management.

• Differentiate the role of the nurse in the hospital or birth center setting from the role of the home care nurse in assessing potential problems and managing care of women with postpartum physiologic complications.

Collaborative efforts of the health care team are needed to provide safe and effective care to the woman and family experiencing postpartum physiologic complications. This chapter focuses on hemorrhage and infection.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) continues to be a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2006; Johnson, Gregory, & Niebyl, 2007). It is a life-threatening event that can occur with little warning and is often unrecognized until the mother has profound symptoms. PPH has been traditionally defined as the loss of more than 500 ml of blood after vaginal birth and 1000 ml after cesarean birth (MacMullen, Dulski, & Meagher, 2005). A 10% change in hematocrit between admission for labor and postpartum or the need for erythrocyte transfusion also has been used to define PPH (Francois & Foley, 2007). However, defining PPH clinically is not a clear-cut undertaking. Diagnosis is often based on subjective observations, with blood loss often being underestimated by as much as 50% (Cunningham, Leveno, Bloom, Hauth, Rouse, & Spong, 2010).

Traditionally PPH has been classified as early or late with respect to the birth. Early, acute, or primary PPH occurs within 24 hours of the birth. Late or secondary PPH occurs more than 24 hours and up to 6 to 12 weeks postpartum (ACOG, 2006; Francois & Foley, 2007). Today’s health care environment encourages shortened stays after birth, thereby increasing the potential for acute episodes of PPH to occur outside the traditional hospital or birth center setting.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Considering the problem of excessive bleeding with reference to the stages of labor is helpful. From birth of the infant until separation of the placenta, the character and quantity of blood passed can suggest excessive bleeding. For example, dark red blood is probably of venous origin, perhaps from varices or superficial lacerations of the birth canal. Bright blood is arterial and can indicate deep lacerations of the cervix. Spurts of blood with clots can indicate partial placental separation. Failure of blood to clot or remain clotted indicates a pathologic condition or coagulopathy such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Chapter 28) (Francois & Foley, 2007).

Excessive bleeding may occur during the period from the separation of the placenta to its expulsion or removal. Commonly such excessive bleeding is the result of incomplete placental

separation, undue manipulation of the fundus, or excessive traction on the cord. After the placenta has been expelled or removed, persistent or excessive blood loss usually is the result of atony of the uterus or prolapse of the uterus into the vagina. Late PPH can be the result of subinvolution of the uterus, endometritis, or retained placental fragments (Cunningham et al., 2010). Predisposing factors for PPH are listed in Box 34-1.

Uterine Atony

Uterine atony is marked hypotonia of the uterus. Normally, placental separation and expulsion are facilitated by contraction of the uterus, which also prevents hemorrhage from the placental site. The corpus is in essence a basket-weave of strong, interlacing smooth muscle bundles through which many large maternal blood vessels pass (see Fig. 4-3). If the uterus is flaccid after detachment of all or part of the placenta, brisk venous bleeding occurs, and normal coagulation of the open vasculature is impaired and continues until the uterine muscle is contracted.

Uterine atony is the leading cause of PPH, complicating approximately 1 in 20 births (Francois & Foley, 2007). It is associated with high parity, hydramnios, a macrosomic fetus, and multifetal gestation. In such conditions the uterus is “overstretched” and contracts poorly after the birth. Other causes of atony include traumatic birth, use of halogenated anesthesia (e.g., halothane) or magnesium sulfate, rapid or prolonged labor, chorioamnionitis, and use of oxytocin for labor induction or augmentation (Cunningham et al., 2010; Francois & Foley). PPH in a previous pregnancy is a predominant risk factor for recurrent PPH (Kominiarek & Kilpatrick, 2007).

Lacerations of the Genital Tract

Lacerations of the cervix, the vagina, and the perineum also are causes of PPH. Hemorrhage related to lacerations should be suspected if bleeding continues despite a firm, contracted uterine fundus. This bleeding can be a slow trickle, an oozing, or frank hemorrhage. Factors that influence the causes and incidence of obstetric lacerations of the lower genital tract include operative birth, precipitate birth, congenital abnormalities of the maternal soft parts, and contracted pelvis. Other possible causes of lacerations are size, abnormal presentation, and position of the fetus; relative size of the presenting part and the birth canal; previous scarring from infection, injury, or operation; and vulvar, perineal, and vaginal varicosities.

Extreme vascularity in the labial and periclitoral areas often results in profuse bleeding if laceration occurs. Hematomas also may be present.

Lacerations of the perineum are the most common of all injuries in the lower portion of the genital tract. These are classified as first, second, third, and fourth degree (see Chapter 19). An episiotomy may extend to become either a third- or fourth-degree laceration.

Prolonged pressure of the fetal head on the vaginal mucosa ultimately interferes with the circulation and may produce ischemic or pressure necrosis. The state of the tissues in combination with the type of birth may result in deep vaginal lacerations, with consequent predisposition to vaginal hematomas.

Pelvic hematomas may be vulvar, vaginal, or retroperitoneal in origin. Vulvar hematomas are the most common. Pain is the most common symptom, and most vulvar hematomas are visible. Vaginal hematomas occur more commonly in association with a forceps-assisted birth, an episiotomy, or primigravidity (Francois & Foley, 2007). During the postpartum period, if the woman reports a persistent perineal or rectal pain or a feeling of pressure in the vagina, a thorough examination is made. However, a retroperitoneal hematoma may cause minimal pain, and the initial symptoms may be signs of shock (Francois & Foley).

Cervical lacerations usually occur at the lateral angles of the external os. Most are shallow, and bleeding is minimal. More extensive lacerations may extend into the vaginal vault or into the lower uterine segment.

Retained Placenta

Nonadherent retained placenta may result from partial separation of a normal placenta, entrapment of the partially or completely separated placenta by an hourglass constriction ring of the uterus, mismanagement of the third stage of labor. Placental retention because of poor separation is common in very preterm births (20 to 24 weeks of gestation).

Management of nonadherent retained placenta is by manual separation and removal by the primary health care provider. Supplementary anesthesia is not usually needed for women who have had regional anesthesia for birth. For other women, administration of light nitrous oxide and oxygen inhalation anesthesia or intravenous (IV) thiopental facilitates uterine exploration and placental removal. After this removal, the woman is at continued risk for PPH and for infection.

Adherent Retained Placenta

Abnormal adherence of the placenta occurs for reasons unknown, but it is thought to result from zygotic implantation in an area of defective endometrium such that no zone of separation is present between the placenta and the decidua. Attempts to remove the placenta in the usual manner are unsuccessful, and laceration or perforation of the uterine wall may result, putting the woman at great risk for severe PPH and infection (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Unusual placental adherence may be partial or complete. The following degrees of attachment are recognized:

• Placenta accreta—slight penetration of myometrium by placental trophoblast

• Placenta increta—deep penetration of myometrium by placenta

Bleeding with complete or total placenta accreta may not occur unless separation of the placenta is attempted. With more extensive involvement, bleeding will become profuse when removal of the placenta is attempted. Cesarean hysterectomy is indicated in approximately two thirds of women. If future fertility is desired, uterine conserving techniques may be attempted. Blood component replacement therapy is often necessary (Francois & Foley, 2007).

Inversion of the Uterus

Inversion of the uterus after birth is a potentially life-threatening but rare complication. The incidence of uterine inversion is approximately 1 in 2500 births (Francois & Foley, 2007), and the condition may recur with a subsequent birth. Uterine inversion may be partial or complete. Complete inversion of the uterus is obvious; a large, red, rounded mass (perhaps with the placenta attached) protrudes 20 to 30 cm outside the introitus. Incomplete inversion cannot be seen but must be felt; a smooth mass will be palpated through the dilated cervix. Contributing factors to uterine inversion include fundal implantation of the placenta, manual extraction of the placenta, short umbilical cord, uterine atony, leiomyomas, and abnormally adherent placental tissue (Francois & Foley). The primary presenting signs of uterine inversion are hemorrhage, shock, and pain in the absence of a palpable fundus abdominally.

Prevention—always the easiest, cheapest, and most effective therapy—is especially appropriate for uterine inversion. The umbilical cord should not be pulled on strongly unless the placenta has definitely separated.

Subinvolution of the Uterus

Late postpartum bleeding may occur as a result of subinvolution of the uterus. Recognized causes of subinvolution include retained placental fragments and pelvic infection.

Signs and symptoms include prolonged lochial discharge, irregular or excessive bleeding, and sometimes hemorrhage. A pelvic examination usually reveals a uterus that is larger than normal and that may be boggy.

Care Management

Early recognition and of PPH are critical to care management. The first step is to evaluate the contractility of the uterus. If the uterus is hypotonic, management is directed toward increasing contractility and minimizing blood loss.

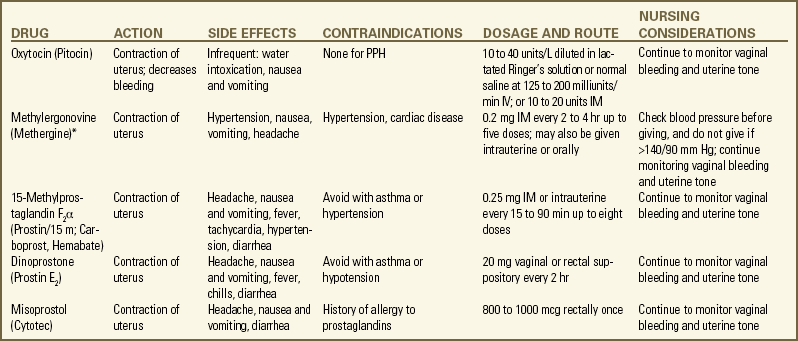

Hypotonic Uterus: The initial management of excessive postpartum bleeding is firm massage of the uterine fundus (Hofmeyr, Abdel-Aleem, & Abdel-Aleem, 2008). Expression of any clots in the uterus, elimination of any bladder distention, and continuous IV infusion of 10 to 40 units of oxytocin added to 1000 ml of lactated Ringer’s or normal saline solution also are primary interventions. If the uterus fails to respond to oxytocin, a 0.2-mg dose of ergonovine (Ergotrate) or methylergonovine (Methergine) may be given intramuscularly to produce sustained uterine contractions. However, administering a 0.25-mg dose of a derivative of prostaglandin F2α (carboprost tromethamine [Carboprost; Hemabate]) intramuscularly is more common. It can also be given intramyometrially at cesarean birth or intraabdominally after vaginal birth (Francois & Foley, 2007). Prostaglandin E2 (Dinoprostone) 20 mg vaginal or rectal suppository and rectal (800 to 1000 mcg) administration of misoprostol (Cytotec) also are used (ACOG, 2006).(see the Medication Guide for a comparison of drugs used to manage PPH to in addition to the medications used to contract the uterus, rapid administration of crystalloid solutions or blood or blood products or both will be needed to restore the woman’s intravascular volume (Francois & Foley).

Oxygen can be given by nonrebreather face mask to enhance oxygen delivery to the cells. An indwelling urinary catheter is usually inserted to monitor urine output as a measure of intravascular volume. Laboratory studies usually include a complete blood count with platelet count, fibrinogen, fibrin split products, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time. Blood type and antibody screen are done if not previously performed (Cunningham et al., 2010).

If bleeding persists, bimanual compression may be considered by the obstetrician or nurse-midwife. This procedure involves inserting a fist into the vagina and pressing the knuckles against the anterior side of the uterus, and then placing the other hand on the abdomen and massaging the posterior uterus with it. If the uterus still does not become firm, manual exploration of the uterine cavity for retained placental fragments is implemented. If the preceding procedures are ineffective, surgical management may be the only alternative. Surgical management options include vessel ligation (uteroovarian, uterine, hypogastric), selective arterial embolization, and hysterectomy (Cunningham et al., 2010; Francois & Foley, 2007).

Bleeding with a Contracted Uterus: If the uterus is firmly contracted and bleeding continues, the source of bleeding still must be identified and treated. Assessment may include visual or manual inspection of the perineum, the vagina, the uterus, the cervix, or the rectum and laboratory studies (e.g., hemoglobin, hematocrit, coagulation studies, platelet count). Treatment depends on the source of the bleeding. Lacerations are usually sutured. Hematomas may be managed with observation, cold therapy, ligation of the bleeding vessel, or evacuation. Fluids and blood replacement may be needed (Francois & Foley, 2007).

Uterine Inversion: Uterine inversion is an emergency situation requiring immediate recognition, replacement of the uterus within the pelvic cavity, and correction of associated clinical conditions. Tocolytics (e.g., magnesium sulfate, terbutaline) or halogenated anesthetics may be given to relax the uterus before attempting replacement (Cunningham et al., 2010). Medical management of this condition includes repositioning the uterus, giving oxytocin after the uterus is repositioned, treating shock, and initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics (Cunningham et al.; Francois & Foley, 2007).

Subinvolution: Treatment of subinvolution depends on the cause. Ergonovine, 0.2 mg every 3 to 4 hours for 24 to 48 hours, and antibiotic therapy are the most common medications used (Cunningham et al., 2010). Dilation and curettage (D&C) may be needed to remove retained placental fragments or to debride the placental site.

Herbal Remedies

Herbal remedies have been used with some success to control PPH after the initial management and control of bleeding, particularly outside the United States. Some herbs have homeostatic actions, whereas others work as oxytocic agents to contract the uterus (Tiran & Mack, 2000). Box 34-2 lists herbs that have been used and their actions. However, published evidence of the safety and efficacy of herbal therapy is lacking. Evidence from well-controlled studies is needed before recommendations for practice can be made (Born & Barron, 2005).![]()

Nursing Interventions

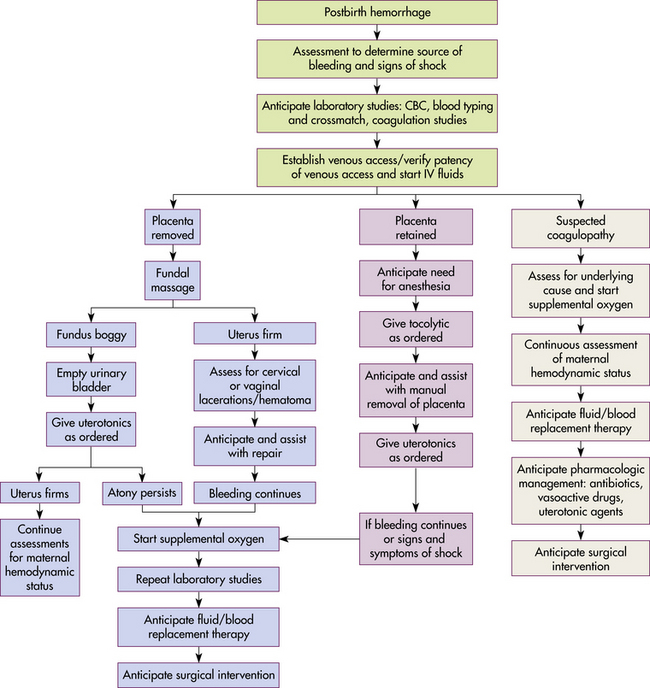

PPH may be sudden and even exsanguinating. The nurse must therefore be alert to the symptoms of hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock and be prepared to act quickly to minimize blood loss (Fig. 34-1 and Box 34-3). Immediate assessments, nursing diagnoses, expected outcomes of care, and interventions are listed in the Nursing Process box.

FIG. 34-1 Nursing assessments for postpartum bleeding. CBC, Complete blood count; IV, intravenous; uterotonics, medications to contract the uterus.

The woman and her family will be anxious about her condition. The nurse can intervene by calmly providing explanations about interventions being performed and the need to act quickly.

After the bleeding has been controlled, the care of the woman with lacerations of the perineum is similar to that of women with episiotomies (analgesia as needed for pain and hot or cold applications as necessary). The need for increased roughage in the diet and increased intake of fluids is emphasized. Stool softeners may be used to assist the woman in reestablishing bowel habits without straining and putting stress on the suture lines.

The care of the woman who has experienced an inversion of the uterus focuses on immediate stabilization of hemodynamic status. This situation requires close observation of her response to treatment to prevent shock or fluid overload. If the uterus has been repositioned manually, care must be taken to avoid aggressive fundal massage.

Discharge instructions for the woman who has had PPH are similar to those for any postpartum woman. In addition, the woman should be told that she will probably feel fatigue, even exhaustion, and will need to limit her physical activities to conserve her strength. She may need instructions in increasing her dietary iron and protein intake and iron supplementation to rebuild lost red blood cell (RBC) volume. She may need assistance with infant care and household activities until she has regained strength. Some women have problems with delayed or insufficient lactation and postpartum depression (PPD). Referrals for home care follow-up or to community resources may be needed, such as to Postpartum Support International at www.chss.iup.edu/postpartum (see the Nursing Care Plan).

Hemorrhagic (Hypovolemic) Shock

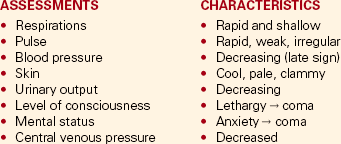

Hemorrhage may result in hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock. Shock is an emergency situation in which the perfusion of body organs may become severely compromised and death may occur. Physiologic compensatory mechanisms are activated

in response to hemorrhage. The adrenal glands release catecholamines, causing constriction of arterioles and venules in the skin, the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract, the liver, and the kidneys. The available blood flow is diverted to the brain and the heart and away from other organs, including the uterus. If shock is prolonged, the continued reduction in cellular oxygenation results in an accumulation of lactic acid and acidosis (from anaerobic glucose metabolism). Acidosis (reduced serum pH) causes arteriolar vasodilation; venule vasoconstriction persists. A circular pattern is established; that is, decreased perfusion, increased tissue anoxia and acidosis, edema formation, and pooling of blood further decrease the perfusion. Cellular death occurs. See the Emergency box for assessments and interventions for hemorrhagic shock.

Medical Management

Vigorous treatment is necessary to prevent adverse sequelae. Medical management of hypovolemic shock involves restoring circulating blood volume and treating the cause of the hemorrhage (e.g., lacerations, uterine atony, or inversion). To restore circulating blood volume, a rapid IV infusion of crystalloid solution is given at a rate of 3 ml infused for every 1 ml of estimated blood loss (e.g., 3000 ml infused for 1000 ml of blood loss). Packed RBCs are usually infused if the woman is still actively bleeding and no improvement in her condition is noted after the initial crystalloid infusion. Infusion of fresh-frozen plasma may be needed if clotting factors and platelet counts are below normal values (Cunningham et al., 2010; Francois & Foley, 2007).

Nursing Interventions

Hemorrhagic shock can occur rapidly, but the classic signs of shock may not appear until the postpartum woman has lost 30% to 40% of her blood volume. The nurse must continue to reassess the woman’s condition, as evidenced by the degree of measurable and anticipated blood loss, and mobilize appropriate resources.

Most interventions are instituted to improve or monitor tissue perfusion. The nurse continues to monitor the woman’s pulse and blood pressure. If invasive hemodynamic monitoring is ordered, the nurse may assist with the placement of the central venous pressure (CVP) or pulmonary artery (Swan-Ganz) catheter and monitor CVP, pulmonary artery pressure, or pulmonary artery wedge pressure as ordered (Gilbert, 2011) (see Chapter 31).

Additional assessments to be made include evaluating skin temperature, color, and turgor, as well as assessing the woman’s mucous membranes. Breath sounds should be auscultated before fluid volume replacement, if possible, to provide a baseline for future assessment. Inspection for oozing at the sites of incisions or injections and assessment for the presence of petechiae or ecchymosis in areas not associated with surgery or trauma are critical in evaluating for disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Chapter 28).

Oxygen is administered, preferably by nonrebreathe face mask, at 10 to 12 L/min to maintain oxygen saturation. Oxygen saturation should be monitored with a pulse oximeter, although measurements may not always be accurate in a woman with hypovolemia or decreased perfusion. Level of consciousness is assessed frequently and provides an additional indication of blood volume and oxygen saturation (Gilbert, 2011). In early stages of decreased blood flow the woman may report “seeing stars” or feeling dizzy or nauseated. She may become restless and orthopneic. As cerebral hypoxia increases, she may become confused and react slowly or not at all to stimuli. Some women complain of headaches (Curran, 2003). An improved sensorium is an indicator of improved perfusion.

Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring may be indicated for the woman who is hypotensive or tachycardic, continues to bleed profusely, or is in shock. A indwelling (Foley) catheter with a urometer is inserted to allow hourly assessment of urinary output. The most objective and least invasive assessment of adequate organ perfusion and oxygenation is urinary output of at least 30 ml/hr (Cunningham et al., 2010). Blood may be drawn and sent to the laboratory for studies that include hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, platelet count, and coagulation profile.

Fluid or Blood Replacement Therapy

Critical to successful management of the woman with a hemorrhagic complication is the establishment of venous access, preferably with a large-bore IV catheter. The establishment of two IV lines facilitates fluid resuscitation. Vigorous fluid resuscitation includes the administration of crystalloids (lactated Ringer’s, normal saline solutions), colloids (albumin), blood, and blood components (Francois & Foley, 2007). Fluid resuscitation must be closely monitored because fluid overload may occur. Intravascular fluid overload occurs more frequently with colloid therapy than with other fluids. Transfusion reactions may follow the administration of blood or blood components, including cryoprecipitates. Even in an emergency, each unit should be checked per hospital protocol. Complications of fluid or blood replacement therapy include hemolytic reactions, febrile reactions, allergic reactions, circulatory overload, and air embolism.

Coagulopathies

When bleeding is continuous and no identifiable source is found, a coagulopathy may be the cause. The woman’s coagulation status must be assessed quickly and continuously. The nurse can draw and send blood to the laboratory for studies. Abnormal results depend on the cause and can include increased prothrombin time, increased partial thromboplastin time, decreased platelets, decreased fibrinogen level, increased fibrin degradation products, and prolonged bleeding time. Causes of coagulopathies may be pregnancy complications such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura or von Willebrand disease and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Idiopathic or immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an autoimmune disorder in which antiplatelet antibodies decrease the life span of the platelets. Thrombocytopenia, capillary fragility, and increased bleeding time are diagnostic findings. ITP may cause severe hemorrhage after cesarean birth or cervical or vaginal lacerations. The incidence of postpartum uterine bleeding and vaginal hematomas also is increased. Neonatal thrombocytopenia can result, but serious bleeding is unusual (Rosenberg, 2007).

Medical management focuses on control of platelet stability. If ITP was diagnosed during pregnancy, the woman likely was treated with corticosteroids or IV immunoglobulin. Platelet transfusions are usually given when bleeding is significant. A splenectomy may be needed if the ITP does not respond to medical management (Samuels, 2007).

von Willebrand Disease

von Willebrand disease (vWD), a type of hemophilia, is probably the most common of all hereditary bleeding disorders (Samuels, 2007). Although von Willebrand disease is rare, it is among the most common congenital clotting defects in U.S. women of childbearing age. It results from a deficiency or defect in a blood clotting protein called von Willebrand factor (vWF). There are as many as 20 variations of vWD disorders, most of which are inherited as autosomal dominant traits—types I and II are the most common (Cunningham et al., 2010). Symptoms include recurrent bleeding episodes such as nosebleeds or after tooth extraction, bruising easily, prolonged bleeding time (the most important test), factor VIII deficiency (mild to moderate), and bleeding from mucous membranes (Samuels). Although factor VIII increases during pregnancy, a risk for PPH still exists as levels of vWF begin to decrease (Cunningham et al.).

The woman may be at risk for bleeding for up to 4 weeks postpartum. The treatment of choice is administration of desmopressin, which promotes the release of vWF and factor VIII. It can be given nasally, intravenously, or orally. Transfusion therapy with plasma products that have been treated for viruses and contain factor VIII and vWF (e.g., Humate-P, Alphanate) also may be used (Lee & Abdul-Kadir, 2005; Samuels, 2007).

Thromboembolic Disease

A thrombosis results from the formation of a blood clot or clots inside a blood vessel and is caused by inflammation (thrombophlebitis) or partial obstruction of the vessel. Three thromboembolic conditions are of concern in the postpartum period:

• Superficial venous thrombosis: involvement of the superficial saphenous venous system

• Deep venous thrombosis: involvement varies but can extend from the foot to the iliofemoral region

• Pulmonary embolism: complication of deep venous thrombosis occurring when part of a blood clot dislodges and is carried to the pulmonary artery, where it occludes the vessel and obstructs blood flow to the lungs

Incidence and Etiology

The incidence of thromboembolic disease in the postpartum period varies from approximately 1 in 1000 to 1 in 2000 women (Pettker & Lockwood, 2007). The incidence has declined in the past 20 years because early ambulation after childbirth has become the standard practice. The major causes of thromboembolic disease are venous stasis and hypercoagulation, both of which are present in pregnancy and continue into the postpartum period. Other risk factors include operative vaginal birth, cesarean birth, history of venous thrombosis or varicosities, obesity, maternal age older than 35 years, multiparity, infection, immobility, and smoking. Women with associated genetic risk factors are also at risk (Pettker & Lockwood).

Clinical Manifestations

Superficial venous thrombosis is the most frequent form of postpartum thrombophlebitis. It is characterized by pain and tenderness in the lower extremity. Physical examination may reveal warmth, redness, and an enlarged, hardened vein over the site of the thrombosis. Deep venous thrombosis is more common than superficial venous thrombosis during pregnancy than after the birth and is characterized by unilateral leg pain, calf tenderness, and swelling (Fig. 34-2). Physical examination may reveal redness and warmth, but many women have few if any symptoms. A positive Homans sign may be present, but further evaluation is needed because the calf pain may be attributed to other causes, such as a strained muscle resulting from the birthing position (Pettker & Longwood, 2007). Acute pulmonary embolism is characterized by dyspnea and tachypnea (more than 20 breaths/min). Other signs and symptoms frequently seen include tachycardia (more than 100 beats/min), apprehension, cough, hemoptysis, elevated temperature, syncope, and pleuritic chest pain (Cunningham et al., 2010; Pettker & Lockwood).

Physical examination is not a sensitive diagnostic indicator for thrombosis. Venography is the most accurate method for diagnosing deep venous thrombosis; however, it is an invasive procedure that is associated with serious complications. Noninvasive diagnostic methods such as real-time and color Doppler ultrasound are commonly used. Cardiac auscultation may reveal murmurs with pulmonary embolism. Electrocardiograms are usually normal. Arterial oxygen pressure may be lower than normal (Katz, 2007a; Pettker & Lockwood, 2007).

Medical Management

Superficial venous thrombosis is treated with analgesia (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents), rest with elevation of the affected leg, and elastic stockings (Cunningham et al., 2010; Katz, 2007a). Local application of moist heat also may be used. Deep venous thrombosis is initially treated with anticoagulant (usually continuous IV heparin) therapy, bed rest with the affected leg elevated, and analgesia. After the symptoms have decreased, the woman may be fitted with elastic stockings to prevent venous congestion when she is allowed to ambulate. The woman is taught to put on the elastic stockings before getting out of bed. IV heparin therapy continues for 3 to 5 days or until symptoms resolve. Oral anticoagulant therapy (warfarin) is started during this time and will be continued for approximately 3 months. Continuous IV heparin therapy is used for pulmonary embolism until symptoms have resolved and is followed by subcutaneous heparin or oral anticoagulant therapy for up to 6 months (Pettker & Lockwood, 2007).

Nursing Interventions

In the hospital setting, nursing care of the woman with a thrombosis consists of continued assessments: inspecting and palpating the affected area; palpating peripheral pulses; checking for Homans sign; measuring and comparing leg circumferences; inspecting for signs of bleeding; monitoring for signs of pulmonary embolism including chest pain, coughing, dyspnea, and tachypnea; and assessing respiratory status for presence of crackles. Laboratory reports are monitored for prothrombin or partial thromboplastin times. The woman and her family are assessed for their level of understanding about the diagnosis and their ability to cope during the unexpected extended period of recovery.

Interventions include explanations and education about the diagnosis and the treatment. The woman will need assistance with personal care as long as she is on bed rest; the family should be encouraged to participate in the care if that is what she and they wish. While the woman is on bed rest, she should be encouraged to change positions frequently but to avoid placing her knees in a sharply flexed position that could cause pooling of blood in the lower extremities. She also should be cautioned to avoid rubbing the affected area because this action could cause the clot to dislodge. Heparin and warfarin are administered as ordered, and the physician is notified if clotting times are outside the therapeutic level. If the woman is breastfeeding, she is assured that neither heparin nor warfarin is excreted in significant quantities in breast milk. If the infant has been discharged, the family is encouraged to bring the infant for feedings as permitted by hospital policy; the mother also can express milk to be sent home.

Pain can be managed with a variety of measures. Position changes, elevating the leg, and application of moist heat may decrease discomfort. Administration of analgesics or antiinflammatory medications may be necessary.

The woman is usually discharged home with oral anticoagulants and will need explanations about the treatment schedule and possible side effects. If subcutaneous injections are to be given, the woman and family are taught how to administer the medication and about site rotation. The woman and her family also should be given information about safe care practices to prevent bleeding and injury while she is receiving anticoagulant therapy, such as using a soft toothbrush and an electric razor. She also will need information about follow-up with her health care provider to monitor clotting times and to make sure the correct dose of anticoagulant therapy is maintained. The woman also should use a reliable method of contraception if taking warfarin because this medication is considered teratogenic (Gilbert, 2011). Oral contraceptives are contraindicated because of the increased risk for thrombosis (Cunningham et al., 2010).

Postpartum Infections

Postpartum infection, or puerperal infection, is any clinical infection of the genital tract that occurs within 28 days after miscarriage, induced abortion, or childbirth. The definition used in the United States continues to be the presence of a fever of 38° C or more on 2 successive days of the first 10 postpartum days (not counting the first 24 hours after birth) (Katz, 2007b). Puerperal infection is probably the major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality throughout the world; endometritis is the most common cause. In the United States it occurs after approximately 2% of vaginal births and 10% to 15 % of cesarean births (Katz, 2007b). Other common postpartum infections include wound infections, mastitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and respiratory tract infections.

The most common infecting organisms are the numerous streptococcal and anaerobic organisms. Staphylococcus aureus, gonococci, coliform bacteria, and clostridia are less common but serious pathogenic organisms that also cause puerperal infection. Postpartum infections are more common in women who have concurrent medical or immunosuppressive conditions or who had a cesarean or operative vaginal birth. Intrapartal factors such as prolonged rupture of membranes, prolonged labor, and internal maternal or fetal monitoring also increase the risk of infection (Duff, 2007). Factors that predispose the woman to postpartum infection are listed in Box 34-4.

Endometritis

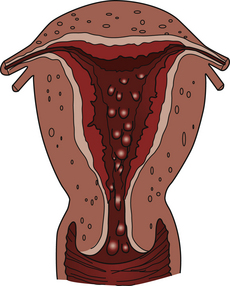

Endometritis is the most common postpartum infection. It usually begins as a localized infection at the placental site (Fig. 34-3) but can spread to involve the entire endometrium. Incidence is higher after cesarean birth than after vaginal birth. Assessment for signs of endometritis may reveal a fever (usually greater than 38° C); increased pulse; chills; anorexia; nausea; fatigue and lethargy; pelvic pain; uterine tenderness; or foul-smelling, profuse lochia (Duff, 2007). Leukocytosis and a markedly increased RBC sedimentation rate are typical laboratory findings of postpartum infections. Anemia also may be present. Blood cultures or intracervical or intrauterine bacterial cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) should reveal the offending pathogens within 36 to 48 hours.

Wound Infections

Wound infections also are common postpartum infections but often develop after the woman is at home. Sites of infection include the cesarean incision and the episiotomy or repaired laceration site. Predisposing factors are similar to those for endometritis (see Box 34-4). Signs of wound infection include erythema, edema, warmth, tenderness, seropurulent drainage, and wound separation. Fever and pain also may be present.

Urinary Tract Infections

UTIs occur in 2% to 4% of postpartum women. Risk factors include urinary catheterization, frequent pelvic examinations, epidural anesthesia, genital tract injury, history of UTI, and cesarean birth. Signs and symptoms include dysuria, frequency and urgency, low-grade fever, urinary retention, hematuria, and pyuria. Costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness or flank pain may indicate upper UTI. Urinalysis results may reveal Escherichia coli, although other gram-negative aerobic bacilli also may cause UTIs.

Mastitis

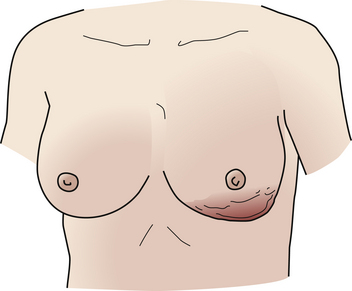

Mastitis affects approximately 1% to 10% of women soon after childbirth, most of whom are first-time mothers who are breastfeeding (Newton, 2007). Mastitis almost always is unilateral and develops well after the flow of milk has been established (Fig. 34-4). The infecting organism generally is the hemolytic Staphylococcus aureus. An infected nipple fissure usually is the initial lesion, but the ductal system is involved next. Inflammatory edema and engorgement of the breast soon obstruct the flow of milk in a lobe; regional, then generalized, mastitis follows. If treatment is not prompt, mastitis may progress to a breast abscess.

Symptoms rarely appear before the end of the first postpartum week and are more common in the second to fourth weeks. Chills, fever, malaise, and local breast tenderness are noted first. Pain, swelling, redness, and axillary adenopathy also may occur.

Care Management

Signs and symptoms associated with postpartum infection were discussed with each infection. Laboratory tests usually performed include a complete blood count, venous blood cultures, and uterine tissue cultures. Nursing diagnoses for women experiencing postpartum infection are listed in Box 34-5.

The most effective and least expensive treatment of postpartum infection is prevention. Good maternal perineal hygiene with thorough handwashing is emphasized. Strict adherence by all health care personnel to aseptic techniques during childbirth and the postpartum period is very important.

Management of endometritis consists of IV broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (e.g., cephalosporins, penicillins, clindamycin, and gentamicin) and supportive care, including hydration, rest, and pain relief. Antibiotic therapy is usually discontinued 24 hours after the woman is asymptomatic (Duff, 2007).

Nursing measures including assessments of lochia, vital signs, and changes in the woman’s condition continue during treatment. Comfort measures depend on the symptoms and can include cool compresses, warm blankets, perineal care, and sitz baths. Teaching should include side effects of therapy, prevention of spread of infection, signs and symptoms of worsening condition, and adherence to the treatment plan and the need for follow-up care. Women may need to be encouraged or assisted to maintain mother-infant interactions and breastfeeding (if allowed during treatment).

Treatment of wound infections may combine antibiotic therapy with wound debridement. Wounds may be opened and drained. Nursing care includes frequent wound and vital sign assessments and wound care. Comfort measures include sitz baths, warm compresses, and perineal care. Teaching includes good hygiene techniques (e.g., changing perineal pads front to back, handwashing before and after perineal care), self-care measures, and signs of worsening conditions to report to the health care provider. The woman is usually discharged to home for self-management or home nursing care after treatment is initiated in the inpatient setting.

Medical management for UTIs consists of antibiotic therapy, analgesia, and hydration. Postpartum women are usually treated on an outpatient basis; therefore, teaching should include instructions on how to monitor temperature, bladder function, and appearance of urine. The woman also should be taught about signs of potential complications and the importance of taking all antibiotics as prescribed. Other suggestions for prevention of UTIs include using proper perineal care, wiping from front to back after urinating or having a bowel movement, and increasing fluid intake.

Because mastitis rarely occurs before the postpartum woman who is breastfeeding is discharged, teaching should include warning signs of mastitis and counseling about the prevention of cracked nipples. Management includes support of breasts, local application of heat (or cold), adequate hydration, analgesics, and antibiotic therapy (e.g., dicloxacillin or flucloxacillin). Lactation can be maintained by emptying the breasts every 2 to 4 hours by breastfeeding, manual expression, or breast pump (Katz, 2007b) (See Chapter 25 for further information).

Postpartum women are usually discharged by 48 hours after birth, and often signs of infection may not be manifested until after the woman is at home. Nurses in birth centers and hospital settings must be able to identify women at risk for postpartum infection and provide anticipatory teaching and counseling before discharge. After discharge, telephone follow-up, hotlines, support groups, lactation counselors, home visits by nurses, and teaching materials (videos, written materials) can be used to decrease the risk of postpartum infections. Home care nurses must be able to recognize signs and symptoms of postpartum infection and provide the appropriate nursing care for women who need follow-up home care.

KEY POINTS

• Postpartum hemorrhage is the most common and most serious type of excessive obstetric blood loss.

• Hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock is an emergency situation in which the perfusion of body organs may become severely compromised, leading to significant risk of morbidity or death for the mother.

• The potential hazards of the therapeutic interventions may further compromise the woman with a hemorrhagic disorder.

• Clotting disorders are associated with many obstetric complications.

• The first symptom of postpartum infection is usually fever greater than 38° C on 2 consecutive days in the first 10 postpartum days (after the first 24 hours).

• Prevention is the most effective and inexpensive treatment of postpartum infection.

![]() Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of the Key Points on

Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of the Key Points on ![]()