Introduction

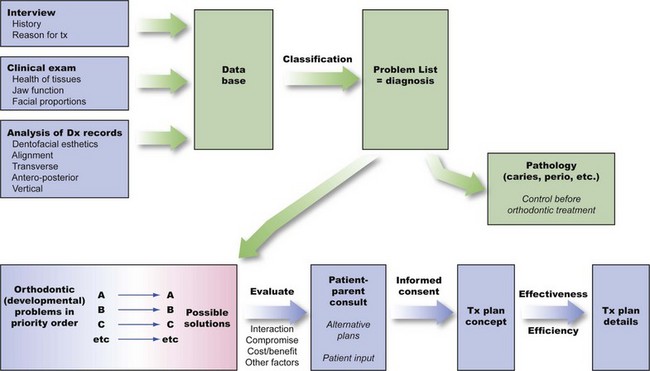

The process of orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning lends itself well to the problem-oriented approach. Diagnosis in orthodontics, as in other disciplines of dentistry and medicine, requires the collection of an adequate database of information about the patient and the distillation from that database of a comprehensive but clearly stated list of the patient’s problems. It is important to recognize that both the patient’s perceptions and the doctor’s observations are needed in formulating the problem list. Then the task of treatment planning is to synthesize the possible solutions to these specific problems (often there are many possibilities) into a specific treatment strategy that would provide maximum benefit for this particular patient.

Keep in mind that diagnosis and treatment planning, though part of the same process, are different procedures with fundamentally different goals. In the development of a database and formulation of a problem list, the goal is truth—the goal of scientific inquiry. At this stage there is no room for opinion or judgment. Instead, a totally factual appraisal of the situation is required. On the other hand, the goal of treatment planning is not scientific truth, but wisdom—the plan that a wise and prudent clinician would follow to maximize benefit for the patient. For this reason, treatment planning inevitably is something of an art form. Diagnosis must be done scientifically; for all practical purposes, treatment planning cannot be science alone. Judgment by the clinician is required as problems are prioritized and as alternative treatment possibilities are evaluated. Wise treatment choices, of course, are facilitated if no significant points have been overlooked previously and if it is realized that treatment planning is an interactive process requiring that the patient be given a role in the decision-making process.

We recommend carrying out diagnosis and treatment planning in a series of logical steps. The following first two steps constitute diagnosis:

1. Development of an adequate diagnostic database.

2. Formulation of a problem list (the diagnosis) from the database. Both pathologic and developmental problems may be present. If so, pathologic problems should be separated from the developmental ones so that they can receive priority for treatment—not because they are more important but because pathologic processes must be under control before treatment of developmental problems begins. The diagnostic process is outlined in detail in Chapter 6.

Once a patient’s orthodontic problems have been identified and prioritized, four issues must be faced in determining the optimal treatment plan: (1) the timing of treatment, (2) the complexity of the treatment that would be required, (3) the predictability of success with a given treatment approach, and (4) the patient’s (and parents’) goals and desires. These issues are considered briefly in the next paragraphs.

Orthodontic treatment can be carried out at any time during a patient’s life and can be aimed at a specific problem or be comprehensive. Usually, treatment is comprehensive (i.e., with a goal of the best possible occlusion, facial esthetics, and stability) and is done in adolescence, as the last permanent teeth are erupting. There are good reasons for this choice. At this point, for most patients there is sufficient growth remaining to potentially improve jaw relationships, and all permanent teeth, including the second molars, can be controlled and placed in a more or less final position. From a psychosocial point of view, patients in this age group often are reaching the point of self-motivation for treatment, which is evident in their improved ability to cooperate during appointments and in appliance and oral hygiene care. A reasonably short course of treatment in early adolescence, as opposed to two stages of early and later treatment, fits well within the cooperative potential of patients and families.

Even though not all patients respond well to treatment during adolescence, treatment at this time remains the “gold standard” against which other approaches must be measured. For a child with obvious malocclusion, does it really make sense to start treatment early in the preadolescent years? Obviously, timing will depend on the specific problems. Issues in the timing of treatment are reviewed in detail in Chapters 7 and 13.

The complexity of the treatment that would be required affects treatment planning, especially in the context of who should do the treatment. In orthodontics, as in all areas of dentistry, it makes sense that the less complex cases would be selected for treatment in general or family practice, while the more complex cases would be referred to a specialist. The only difference in orthodontics is that traditionally the family practitioner has referred a larger number of orthodontic cases. In family practice, an important issue is how you rationally select patients for treatment or referral. Chapter 11 includes a formal scheme for separating patients most appropriate for treatment in family practice from those more likely to require complex treatment.

The third special issue is the predictability of treatment with any particular method. If alternative methods of treatment are available, as usually is the case, which one should be chosen? Data gradually are accumulating to allow choices to be based on evidence of outcomes rather than anecdotal reports and the claims of advocates of particular approaches. Existing data for treatment outcomes, as a basis for deciding what the best treatment approach might be, are emphasized in Chapter 7.

Finally, but most important, treatment planning must be an interactive process. No longer can the doctor decide, in a paternalistic way, what is best for a patient. Both ethically and practically, patients must be involved in the decision-making process. Ethically, patients have the right to control what happens to them in treatment—treatment is something done for them not to them. Practically, the patient’s compliance is likely to be a critical issue in success or failure, and there is little reason to select a mode of treatment that the patient would not support. Informed consent, in its modern form, requires involving the patient in the treatment planning process. This is emphasized in the procedure for presenting treatment recommendations to patients in Chapter 7.

The logical sequence for treatment planning, with these issues in mind, is as follows:

1. Prioritization of the items on the orthodontic problem list so that the most important problem receives highest priority for treatment

2. Consideration of possible solutions to each problem, with each problem evaluated for the moment as if it were the only problem the patient had

3. Evaluation of the interactions among possible solutions to the individual problems

4. Development of alternative treatment approaches, with consideration of benefits to the patient versus risks, costs, and complexity

5. Determination of a final treatment concept, with input from the patient and parent, and selection of the specific therapeutic approach (appliance design, mechanotherapy) to be used

This process culminates with a level of patient-parent understanding of the treatment plan that provides informed consent to treatment. In most instances, after all, orthodontic treatment is elective rather than required. Rarely is there a significant health risk from no treatment, so functional and esthetic benefits must be compared to risks and costs. Interaction with the patient is required to develop the plan in this way.

This diagnosis and treatment planning sequence is illustrated diagrammatically in the figure on page 149.

The chapters of this section address both the important issues and the procedures of orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Chapter 6 focuses on the diagnostic database and the steps in developing a problem list. Chapter 7 addresses the issues of timing and complexity, reviews the principles of treatment planning, and evaluates treatment possibilities for preadolescent, adolescent, and adult patients. Chapters 6 and 7 provide an overview of orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning that every dentist needs and go into greater depth relative to decisions that often are made in specialty practice. In it, we examine the quality of evidence on which clinical decisions are based, discuss controversial areas in current treatment planning with the goal of providing a consensus judgment to the extent this is possible, and outline treatment for patients with special problems related to injury or congenital problems such as cleft lip and palate.