Skin cancer – Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a heterogeneous disease comprising clinically distinct but histologically similar entities with differing risk factors implicated in their aetiopathogenesis.

Aetiopathogenesis

Squamous cell carcinoma is derived from moderately well-differentiated keratinocytes. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is clearly the strongest predisposing risk factor for this condition. The evidence for this is extensive and includes: a direct correlation between average annual UV radiation and risk of SCC; increased incidence with proximity to the equator; high incidence in albinos versus non-albinos in tropical climates; and an association with the development of features of photoageing such as wrinkles. The increased incidence of SCC in the last 25 years parallels an increased exposure to UVA due to both UVB protective sunscreens, which prevent sunburn but prolong exposure to UVA, and also the increased use of sunbeds.

chronic actinic damage, accumulating over a lifetime of sun exposure (p. 106); psoralen with ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatment can predispose

chronic actinic damage, accumulating over a lifetime of sun exposure (p. 106); psoralen with ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatment can predispose

immunosuppression, e.g. in renal transplant patients (p. 57)

immunosuppression, e.g. in renal transplant patients (p. 57)

X-rays or other ionizing radiation; radiant heat (e.g. from a fire; see erythema ab igne, p. 70)

X-rays or other ionizing radiation; radiant heat (e.g. from a fire; see erythema ab igne, p. 70)

chronic ulceration and scarring (e.g. a burn, lupus vulgaris or discoid lupus erythematosus, genetic blistering diseases)

chronic ulceration and scarring (e.g. a burn, lupus vulgaris or discoid lupus erythematosus, genetic blistering diseases)

smoking pipes and cigars (relevant for lip lesions)

smoking pipes and cigars (relevant for lip lesions)

industrial carcinogens (e.g. coal tars, oils)

industrial carcinogens (e.g. coal tars, oils)

genetic factors (e.g. albinos, xeroderma pigmentosum, p. 92).

genetic factors (e.g. albinos, xeroderma pigmentosum, p. 92).

Pathology

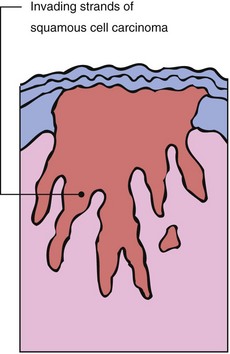

The malignant keratinocytes, which retain the ability to produce keratin, destroy the dermoepidermal junction and invade the dermis in an irregular manner (see Fig. 1).

Bowen’s disease (in situ squamous cell carcinoma)

Bowen’s disease is common and typically occurs on the lower leg in elderly women. The lesions are solitary or multiple. Previous exposure to arsenicals predisposes to the condition.

Pink or lightly pigmented scaly plaques, up to several centimetres in size, are found on the lower leg or trunk (Fig. 1). Transformation into invasive squamous cell carcinoma is infrequent. Bowen’s disease may resemble discoid eczema, psoriasis or superficial basal cell carcinoma. Histologically, the epidermis is thickened and the keratinocytes are atypical, but not invasive. Small biopsy samples may not be representative of the entire lesion and if there is clinical doubt then larger or excisional biopsies should be undertaken.

Bowen’s disease is treated by cryotherapy, curettage, excision, topical 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, or photodynamic therapy (p. 113).

Keratoacanthoma

A keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing tumour usually arising in the sun-exposed skin of the face or arms (Fig. 2). A keratoacanthoma is now generally considered a low-risk SCC, but was previously not regarded as malignant and may resolve spontaneously leaving a prominent scar. The tumour grows rapidly over a few weeks into a dome-shaped nodule up to 2 cm in diameter. There is often a keratin plug, which may fall out to leave a crater.

Histologically, a keratoacanthoma resembles an SCC, although it shows more symmetry and shouldering. Excision is the preferred treatment, but thorough curettage and cautery will usually be satisfactory. If recurrence occurs after curettage, excision is recommended.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant tumour arising from keratinocytes of the epidermis or hair follicle and is the second most common skin cancer. The incidence of SCC is thought to be approximately a quarter that of basal cell carcinoma (BCC), affecting 2 per 1000 population per annum. SCC mainly occurs in white-skinned people over 55 years of age, is three times more common in males than in females and may metastasize.

Clinical presentation

Squamous cell carcinomas usually develop in sun-exposed sites such as the face, neck, forearm or hand (Fig. 3). Commonly other signs of photodamage will be evident in adjacent skin: solar elastosis, hyperkeratosis, mottled pigmentation and telangiectasia. Premalignant changes such as actinic keratoses and Bowen’s disease as well as other skin cancers may also be present. On mucous membranes, leukokeratosis and fissuring or actinic chelosis are frequent. Lesions present in a variety of ways:

A hyperkeratotic papule, plaque or cutaneous horn with an indurated base.

A hyperkeratotic papule, plaque or cutaneous horn with an indurated base.

A small ulcer that refuses to heal.

A small ulcer that refuses to heal.

A firm ulcerated or crusted nodule (Fig. 4).

A firm ulcerated or crusted nodule (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Squamous cell carcinoma.

The cancer is seen here on the upper pinna in a patient with actinically damaged skin.

The tumour may start within an actinic keratosis as a small papule that, if left, progresses to ulcerate and form a crust. This type of SCC does not commonly metastasize. Ulcerating forms of SCC which develop at the edge of ulcers (Fig. 5), in scars and at sites of radiation damage are frequently more aggressive. Metastasis is found in 10% or more of these cancers. An important clinical marker of SCC is its rapidity of growth. Most patients will report a lesion that grows over several months, in contrast to a BCC which would frequently develop slowly over 6 or more months. Tenderness is also an important symptom identified in SCCs and is thought to represent the extension of the SCC around nerves.

Differential diagnosis

An SCC needs to be distinguished from keratoacanthoma, actinic keratosis, BCC, in situ SCC (Bowen’s disease), amelanotic malignant melanoma and seborrhoeic keratosis. Excisional or incisional biopsy is needed in every case to confirm the diagnosis or adequacy of excision.

Management

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Large lesions may require a skin graft. In the elderly, SCCs of the face or scalp can be treated by radiotherapy (after an incisional biopsy for histological diagnosis). SCCs can be subdivided into high risk and low risk of recurrence or metastasis, although the exact boundaries are somewhat controversial. Generally agreed features of a high-risk SCC are given in the Box. Patients are examined for lymph node metastasis at presentation: suspicious nodes are biopsied. Carefully agreed follow-up, especially for high-risk SCCs, is recommended.

Fig. 6 Squamous cell carcinoma on the dorsum of the hand.

Adjacent photo-ageing is evident. Histological examination confirmed that this SCC was 3 mm in thickness.

Fig. 7 Squamous cell carcinoma on the left cheek.

This rapidly growing lesion was firm and tender. Such lesions should be excised urgently and not be managed as a possible cyst.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Bowen’s disease is in situ squamous carcinoma and follows a less aggressive course. Treatment is with cryotherapy, topical, surgical or photodynamic therapy.

Bowen’s disease is in situ squamous carcinoma and follows a less aggressive course. Treatment is with cryotherapy, topical, surgical or photodynamic therapy.

Keratoacanthoma is a spontaneously resolving lesion that bears clinical and histological resemblance to SCC. Excision is recommended.

Keratoacanthoma is a spontaneously resolving lesion that bears clinical and histological resemblance to SCC. Excision is recommended.

Squamous cell carcinoma is often seen in the sun-exposed skin of white people in association with signs of actinic damage. A more aggressive form of the tumour is found with chronic scarring. All types are treated by surgical excision.

Squamous cell carcinoma is often seen in the sun-exposed skin of white people in association with signs of actinic damage. A more aggressive form of the tumour is found with chronic scarring. All types are treated by surgical excision.

Squamous cell carcinomas with a worse prognosis (high risk) include:

Squamous cell carcinomas with a worse prognosis (high risk) include: