Ultraviolet radiation and the skin

An interaction between skin and sunlight is inescapable. The potential for harm depends on the type and length of exposure. Photoageing is a growing problem, because of an increasingly aged population and a rise in the average individual exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

The electromagnetic radiation spectrum

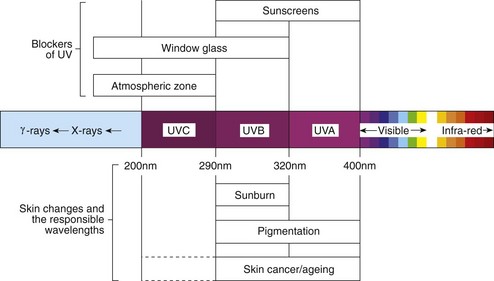

The sun’s emission of electromagnetic radiation ranges from low-wavelength ionizing cosmic, gamma and X-rays to the non-ionizing UV, visible and infrared higher wavelengths (Fig. 1). The ozone layer absorbs UVC, but UVA and smaller amounts of UVB reach ground level. UV radiation is maximal in the middle of the day (11.00–15.00 h) and is increased by reflection from snow, water and sand. UVA penetrates the epidermis to reach the dermis. UVB is mostly absorbed by the stratum corneum – only 10% reaches the dermis. Most window glass absorbs UV less than 320 nm in wavelength. Artificial UV sources emit in the UVB or UVA spectrum. Sunbeds largely emit UVA.

Effects of light on normal skin

Physiological

UVB promotes the synthesis of vitamin D3 from its precursors in the skin, and UVA and UVB stimulate immediate pigmentation (due to photo-oxidation of melanin precursors), melanogenesis and epidermal thickening as a protective measure against UV damage (p. 7).

Sunburn

If enough UVB is given, erythema always results. The threshold dose of UVB – the minimal erythema dose (MED) – is a guide to an individual’s susceptibility. Excessive UVB exposure results in tingling of the skin, followed 2–12 h later by erythema. The redness is maximal at 24 h and fades over the next 2 or 3 days to leave desquamation and pigmentation. Severe sunburn causes oedema, pain, blistering and systemic upset. The early use of topical steroids may help sunburn; otherwise, a soothing shake lotion (e.g. calamine lotion) is applied. Individuals may be skin typed by their likelihood of burning in the sun (Table 1). Prevention is better than cure, and ‘celts’ with a fair ‘type 1’ skin should not sunbathe and must use a high protection factor sunblock cream on exposed sites (p. 108). Some evidence suggests the sun avoidance message may have gone too far in that it could be causing white populations to become vitamin D deficient.

Table 1 Skin type according to sunburn and suntan histories

| Skin type | Reaction to sun exposure |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | Always burns, never tans |

| Type 2 | Always burns, sometimes tans |

| Type 3 | Sometimes burns, always tans |

| Type 4 | Never burns, always tans |

| Type 5 | Brown skin (e.g. Asian caucasoid) |

| Type 6 | Black skin (e.g. black African) |

Sunbeds

Sunbeds emit UVA radiation and have been used by 10–20% of adults in the UK. They will produce a tan in people with skin types 3 and over, but those with type 1 and 2 skin will not tan so well, if at all. Side-effects, particularly redness, itching and dry skin, are seen in half of all users. More serious effects can occur in patients taking drugs or applying preparations with a photosensitizing potential. An acute photosensitive eruption may develop, and intense pigmentation sometimes follows. Sunbeds can exacerbate polymorphic light eruption and systemic lupus erythematosus, and may induce porphyria-like skin fragility and blistering. They are a weak risk factor for malignant melanoma, and may cause premature skin ageing.

Dermatologists discourage sunbed use, particularly in the fair-skinned, in those with several melanocytic naevi and in anyone with a history of skin cancer. Patients who, despite these warnings, wish to use a sunbed should not do so more than twice a year and should limit each course to 10 sessions. Sunbeds are not recommended for the treatment of skin disease.

Phototherapy and photochemotherapy

Natural sunlight helps certain skin diseases (p. 46), and both UVB and UVA are extensively used therapeutically. UVA alone has little effect and is combined with photosensitizing psoralens given systemically or topically.

Ultraviolet B

UVB (290–320 nm) is given three times a week. The starting dose is decided from the patient’s MED or skin type. The dosage is increased on each visit according to a schedule. A course of 10–30 treatments is usual. Narrow-band (311 ± 2 nm: TL01) UV lamps are superior to broadband and allow a lower dose of UV to be used.

UVB is used to treat psoriasis and mycosis fungoides and, occasionally, atopic eczema, vitiligo and pityriasis rosea. It can be given to children and women during pregnancy. Its main side-effects are acute sunburn and an increased long-term risk of skin cancer.

When used to treat psoriasis, UVB may be combined with a topical preparation such as a vitamin D analogue (p. 30), tar or dithranol, or with oral acitretin.

Photochemotherapy (PUVA)

In psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy, 8-methoxypsoralen, taken orally 2 h before UVA (320–400 nm) exposure (Fig. 2), is photoactivated. This causes cross-linkage in DNA, inhibits cell division and suppresses cell-mediated immunity. PUVA is usually given for psoriasis or mycosis fungoides, and sometimes for atopic eczema, polymorphic light eruption (p. 46) or vitiligo (p. 74). The initial dose of UVA is determined by the minimum toxic dose (the MED for PUVA) or skin type, and is increased according to a schedule. PUVA is given two or three times a week and leads to clearance of psoriasis (with tanning) in 15–25 treatments. Maintenance PUVA is not recommended. PUVA can be combined with acitretin (‘Re-PUVA’) but not methotrexate.

The immediate side-effects of pruritus, nausea and erythema are usually mild. The long-term risks of skin cancer and premature skin ageing are related to the number of treatments or total UVA dose. Careful records must be kept. Cataracts are theoretically possible, and UVA-opaque sunglasses must be worn for 24 h after taking the psoralen.

Bath PUVA, in which the patient soaks in a bath containing a psoralen, is an alternative, especially if systemic side-effects make the oral route impractical. A lower dose of UVA is needed. Local PUVA using topical psoralen is useful for psoriasis or dermatitis of the hands or feet.

Photoageing

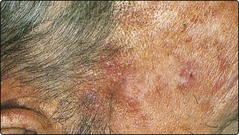

Photoageing describes the skin changes resulting from chronic sun exposure. Photoaged skin is coarse, wrinkled, pale-yellow in colour, telangiectatic, irregularly pigmented, prone to purpura and subject to benign and malignant neoplasms (Fig. 3). Some of these changes resemble those of intrinsic ageing, but the two are not identical, as may be judged by comparing, in an elderly patient, the sun-exposed face with the sun-protected buttock. The features of photoageing are usually more striking, particularly the development of premalignant and malignant tumours. Some rare conditions, e.g. xeroderma pigmentosum (p. 92), predispose to photoageing.

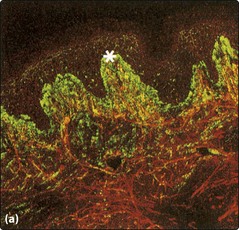

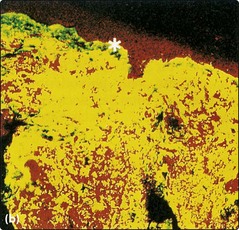

Histologically, the photoaged dermis shows tangled clumps of elastin with proliferation of glycosaminoglycans (Fig. 4). The epidermis is variable in thickness, with areas of atrophy and hypertrophy and a variation in the degree of pigmentation. In vitro, keratinocytes and fibroblasts from sun-exposed sites have a reduced proliferative ability compared with cells from sun-protected sites. The specific clinical changes of photoageing are discussed on page 118.

Fig. 4 (a) Sun-protected skin.

Preservation of the normal pattern of glycosaminoglycan (GAG: green, hyaluronan) and fibriform elastin (red) is shown. Asterisk (*) shows the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).

(b) Sun-exposed elastotic skin.

Tangled clumps of elastin (red) are shown, with proliferations of GAG (chondroitin sulphate) co-localized to elastin (yellow) throughout the dermis. Asterisk (*) shows the DEJ.

Management of photoageing

Prevention is the most effective treatment and is particularly important for those with a fair (type 1 or 2) skin. Avoidance of prolonged, direct sun exposure by wearing long-sleeved shirts and a wide-brimmed hat is useful, and sunscreens (p. 108) are applied to sites that are likely to receive some sun, such as the face or hands. The use of tretinoin or alpha hydroxy acids, in cream formulations, has been shown partially to reverse the clinical and histological changes of photoageing. Chemical peels and laser resurfacing are also used.

UV and the skin

UVB radiation is mostly absorbed by the epidermis, but UVA can penetrate to the dermis. UVB promotes vitamin D synthesis. UVA and UVB stimulate melanogenesis and epidermal thickening.

UVB radiation is mostly absorbed by the epidermis, but UVA can penetrate to the dermis. UVB promotes vitamin D synthesis. UVA and UVB stimulate melanogenesis and epidermal thickening.

Minimal erythema dose is the threshold amount of UVB to cause erythema.

Minimal erythema dose is the threshold amount of UVB to cause erythema.

Sunburn is maximal at 24 h and fades at 2–3 days to leave desquamation and pigmentation of the skin.

Sunburn is maximal at 24 h and fades at 2–3 days to leave desquamation and pigmentation of the skin.

Sunbeds emit UVA and will induce a tan in those with type 3 or 4 skin. Side-effects are common.

Sunbeds emit UVA and will induce a tan in those with type 3 or 4 skin. Side-effects are common.

Photoageing describes coarse, wrinkled, yellowed skin, prone to tumours, resulting from excess sun exposure.

Photoageing describes coarse, wrinkled, yellowed skin, prone to tumours, resulting from excess sun exposure.

UVB therapy, now mostly narrow-band TL01, is mainly used in psoriasis; a course of 10–30 treatments is usual.

UVB therapy, now mostly narrow-band TL01, is mainly used in psoriasis; a course of 10–30 treatments is usual.

PUVA has been a common treatment for psoriasis; used less now. Skin cancer is one potential long-term sequela.

PUVA has been a common treatment for psoriasis; used less now. Skin cancer is one potential long-term sequela.

Treatment of photoageing: prevention is best, but tretinoin cream can reverse some of the changes.

Treatment of photoageing: prevention is best, but tretinoin cream can reverse some of the changes.