CHAPTER 30 Acute Gingival and Periodontal Conditions, Lesions of Endodontic Origin, and Avulsed Teeth

Explain the cause, oral signs and symptoms, and treatment of periodontal abscesses, gingival abscesses, lesions of endodontic origin, acute herpetic gingivostomatitis, pericoronitis, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis.

Explain the cause, oral signs and symptoms, and treatment of periodontal abscesses, gingival abscesses, lesions of endodontic origin, acute herpetic gingivostomatitis, pericoronitis, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis.The dental hygienist is frequently in a position to identify urgent periodontal conditions in need of treatment. A major part of care provided in these situations is to recognize the disease process. In some situations the dental hygienist provides therapeutic or palliative care; in other cases the responsibility lies solely with referral for care. Postponement of appropriate care can result in prolonged pain, further periodontal tissue destruction, and tooth loss.

PERIODONTAL ABSCESS

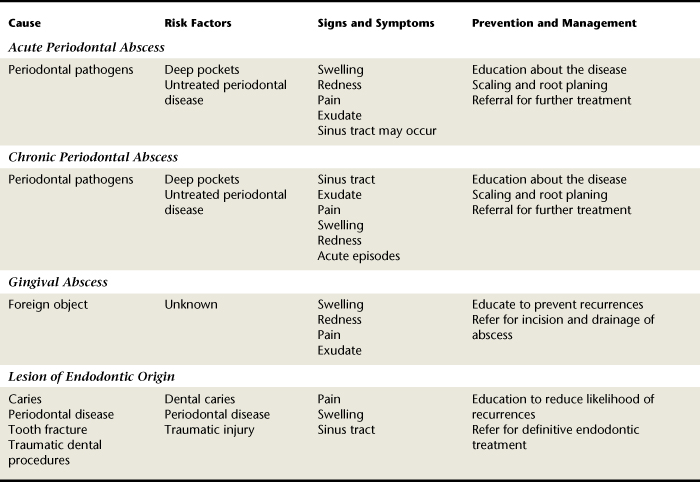

A periodontal abscess is a localized accumulation of pus within the periodontal tissues.1 Periodontal abscesses are distinguished by location—either gingival or periodontal—and by the course of the disease (i.e., acute or chronic).

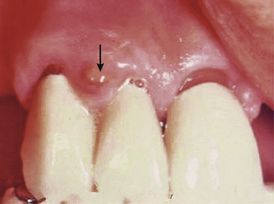

A gingival abscess is a periodontal abscess that is confined to the marginal gingiva and often occurs in previously healthy gingival areas (Figure 30-1).

A gingival abscess is a periodontal abscess that is confined to the marginal gingiva and often occurs in previously healthy gingival areas (Figure 30-1). A periodontal abscess is a deeper infection associated with periodontal pockets, furcations, and bone loss (Figure 30-2).

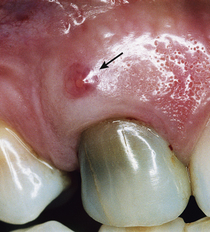

A periodontal abscess is a deeper infection associated with periodontal pockets, furcations, and bone loss (Figure 30-2). The acute periodontal abscess is a lesion with expressed periodontal breakdown, occurring over a limited period of time and with easily detectable clinical symptoms.1 It is characterized by pain, swelling, and other symptoms that lead the client to seek urgent care (Figure 30-3).

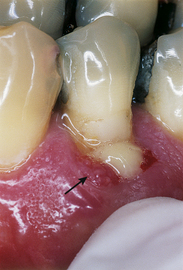

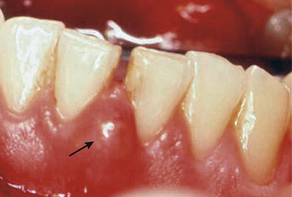

The acute periodontal abscess is a lesion with expressed periodontal breakdown, occurring over a limited period of time and with easily detectable clinical symptoms.1 It is characterized by pain, swelling, and other symptoms that lead the client to seek urgent care (Figure 30-3). The chronic periodontal abscess is a long-standing infection that often is associated with a sinus tract. This opening permits drainage of the infection and a diminution of acute symptoms such as pain and swelling, thus making the abscess chronic in nature. The sinus tract, an abnormal channel that connects the abscess to another space or the surface, is called a fistula1,2 (Figure 30-4).

The chronic periodontal abscess is a long-standing infection that often is associated with a sinus tract. This opening permits drainage of the infection and a diminution of acute symptoms such as pain and swelling, thus making the abscess chronic in nature. The sinus tract, an abnormal channel that connects the abscess to another space or the surface, is called a fistula1,2 (Figure 30-4).

Figure 30-3 An acute periodontal abscess between teeth No. 24 and No. 25 shows obvious signs of redness and swelling.

Periodontal abscesses also have been classified by number as either a single abscess or multiple periodontal abscesses.

Multiple abscesses have been related to factors such as medically compromised systemic health, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and systemic antibiotic therapy for non–oral health–related situations.1

Multiple abscesses have been related to factors such as medically compromised systemic health, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and systemic antibiotic therapy for non–oral health–related situations.1The importance of recognizing and treating clients with periodontal abscesses cannot be overemphasized. Data show that most abscessed teeth, particularly those receiving regular periodontal maintenance, benefit from treatment and can be preserved. An interesting retrospective study of tooth loss caused by a periodontal abscess demonstrated that 55% of teeth with periodontal abscess were maintained for an average of 12.5 years, with a range of 5 to 29 years.3 The importance of recognizing the disease process and encouraging clients to follow through with treatment is significant to one major goal of dental hygiene practice, preserving oral health.

Microbiology of the Periodontal Abscess

All periodontal abscesses share a characteristically complex pathogenic microflora similar to that associated with periodontal diseases. In these pathogenic microflora the preponderance of bacteria changes from approximately 75% gram-positive facultative rods and cocci associated with gingival health to one harboring approximately 74% gram-negative rods.4,5 These are complex mixed infections that vary from person to person and from one site of infection in the mouth to another within the same person.6 Those microbial species most associated with abscesses are listed in Box 30-1.

Characteristics and Treatment of Periodontal Abscesses

Acute Periodontal Abscess

The acute periodontal abscess is a localized accumulation of pus in the gingival wall of a periodontal pocket. It usually occurs on the lateral aspect of the tooth and appears edematous, red, and shiny. It may have a domelike appearance or come to a distinct point. Figure 30-3 presents an example of an acute periodontal abscess with these characteristics. Acute abscesses are frequently associated with preexisting periodontal disease. The anatomic features of periodontal pockets—pocket depth >5mm, furcation involvement, and tortuous pocket anatomy—may predispose the client to occlusion of the pocket orifice. This occlusion permits an exacerbation of infection in the pocket wall and pus formation. Pus can often be expressed from the pocket with gentle finger pressure (Figure 30-5).1

Abscess formation also can occur when a foreign body becomes lodged in the pocket.1 An exacerbated inflammatory reaction then occurs. If the pocket continues to drain through the orifice, it can stabilize and become a chronic infection that drains pus to relieve pressure in the tissues. Conversion to the chronic state rarely occurs when foreign objects such as peanut skins and popcorn hulls are embedded in the pocket, provoking the acute response.

Incomplete scaling and root planing that leaves residual calculus at the base of treated pockets has been suggested as a cause of periodontal abscesses.7 It is postulated that the pocket orifice tightens from improved gingival health, leaving the calculus and associated plaque to infect the deeper pocket tissues. This is a commonly held belief, but few data support it. In an analysis of 29 persons seeking treatment at a postgraduate periodontics clinic and diagnosed with periodontal abscess, 18 of the persons (62%) had untreated periodontal disease, seven (24%) were on periodontal maintenance, and only four (14%) reported a history of recent scaling and root planing. Of these 29 persons, 27 were diagnosed with moderate to severe periodontal disease; the other two had early periodontitis. The mean probing depths of these abscesses were quite deep, 7.3 mm, ranging from 3 to 13 mm, and the abscesses were mostly associated with molar teeth.8

Given the number of abscesses treated, one would expect to see a much larger proportion of clients returning shortly after scaling and root planing appointments if incomplete treatment were a major cause of acute exacerbation. In another study, four types of periodontal treatment were compared and abscess rate was noted. Quadrants treated with supragingival scaling alone developed abscesses to a far greater extent than those treated with subgingival scaling and root planing or those treated with periodontal surgery.9,10 These data suggest that abscess formation is more associated with deep pockets and untreated disease than with recent scaling and root planing treatment. It is also known that residual calculus and plaque biofilm is often left in pockets after even the most thorough scaling and root planing, especially in deep pockets.9 This information highlights the following three points:

The clinician should scale and root plane as completely as possible with the intention of removing all subgingival deposits.

The clinician should scale and root plane as completely as possible with the intention of removing all subgingival deposits. Supragingival scaling alone is totally inadequate in periodontal treatment and may predispose periodontal clients to acute abscess formation.

Supragingival scaling alone is totally inadequate in periodontal treatment and may predispose periodontal clients to acute abscess formation.Signs and Symptoms

Acute periodontal abscess may be associated with any tooth in the mouth. Abscesses appear as shiny, red, raised, and rounded masses on the gingiva or mucosa. Abscesses can point and drain through the tissue or simply drain through the pocket opening. Purulent exudate is usually apparent around the abscess opening or can be expressed by finger pressure. Box 30-2 lists the signs of acute periodontal abscesses.

BOX 30-2 Signs and Symptoms of Acute Periodontal Abscess

From Killoy WJ: Treatment of periodontal abscesses. In Genco RJ, Goldman HM, Cohen DW, eds: Contemporary periodontics, St Louis, 1990, Mosby.

The client also may report that the tooth “feels high,” because it may become slightly extruded owing to swelling.1 Radiographs may be helpful in locating a preexisting area of bone loss and can suggest the origin of the abscess. However, the infection moves through the tissue in the direction of least resistance, so the external features may appear at some distance from the affected tooth.1

Treatment

Treatment consists mainly of drainage and appropriate use of antimicrobial agents. The acute phase of the disease must be managed to alleviate pain and prevent spread of infection. The abscess must be drained, either through the pocket opening or through an incision. Drainage through the pocket opening is less invasive and is commonly performed by the dental hygienist. The tooth or teeth in the affected area are anesthetized and scaled. Postoperative instructions call for rest, fluid intake, and warm saltwater rinses to help reduce swelling. The client is scheduled to return in 24 to 48 hours for reevaluation of the area and planning for required follow-up treatment (e.g., periodontal surgery to eliminate the problem area).9,10

The dentist often delegates initial treatment of the acute abscess that does not require surgical intervention to the dental hygienist. However, sometimes treatment requires an incision and reflection of the tissue (surgical flap procedure) to provide access to perform the debridement. If the client is febrile or if lymphadenopathy is present, the dentist prescribes antibiotic therapy. Figure 30-6 shows an example of debridement therapy for acute periodontal abscess.

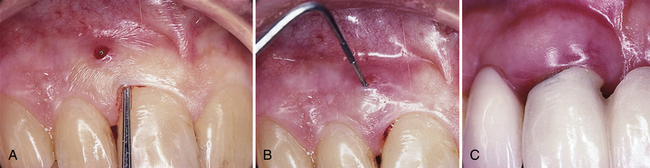

Figure 30-6 Treatment of acute periodontal abscess. Acute abscesses can often be successfully treated without surgical intervention. A, Abscess associated with tooth 9, showing swelling and a nondraining fistula. Clinically the tissue appears very red. B, Probe in place to show 9-mm depth of pocket before scaling, root planing, and curettage. C, Healing after 1 month shows normal tissue architecture and little recession. A 7-mm periodontal pocket is still present, but surgical reduction would result in nonesthetic recession. This situation can continue indefinitely with good homecare and frequent periodontal maintenance.

(Courtesy Philip R. Melnick.)

Repair potential for acute periodontal abscesses is excellent. After treatment, the appearance of the gingiva returns to normal within 6 to 8 weeks. Repair of bone defects requires approximately 9 months. Bone is lost rapidly during the acute phase, but with immediate recognition of the problem and proper treatment the lost tissue can be largely regained.1 The positive nature of clinical results from healing further emphasizes the importance of recognition and treatment of acute abscesses by the dental hygienist.

Chronic Periodontal Abscess

A chronic periodontal abscess resembles an acute periodontal abscess in that there is an overgrowth of pathogenic organisms in a periodontal pocket that drains inflammatory exudate.5,6 Chronic abscesses have communication to the oral cavity, either through the opening of the pocket or through a sinus tract that permits regular drainage.11 The chronic periodontal abscess is usually painless or causes dull, intermittent pain; however, the client may recount previous episodes of painful acute infection.1 Figure 30-7 provides examples of draining chronic periodontal abscesses.

Figure 30-7 Chronic periodontal abscess. A, Draining through a sinus tract. B, Probe inserted to show communication to periodontal pocket. C, Draining through the periodontal pocket.

(Courtesy Philip R. Melnick.)

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of the chronic periodontal abscess are similar to those of acute periodontal abscesses; however, the level of pain can be the distinguishing feature (Box 30-3). The dental hygienist must assess exudate associated with the periodontium as indicative of possible chronic abscess to ensure that appropriate dental referral and treatment are provided.

Treatment

Treatment of chronic periodontal abscess is similar to treatment of acute periodontal abscess. Scaling, usually requiring local anesthesia in the abscess area, must be performed. The client returns within 24 to 48 hours for further diagnosis. The dentist must determine the need for more periodontal treatment to reduce pocket depth and address other periodontal defects. Additional treatment usually includes pocket reduction periodontal surgery, but also may include tooth extraction and more frequent periodontal maintenance visits. Some chronic periodontal abscesses are better treated initially by gaining surgical access.10 Figure 30-8 shows the surgical treatment sequence for a chronic periodontal abscess.

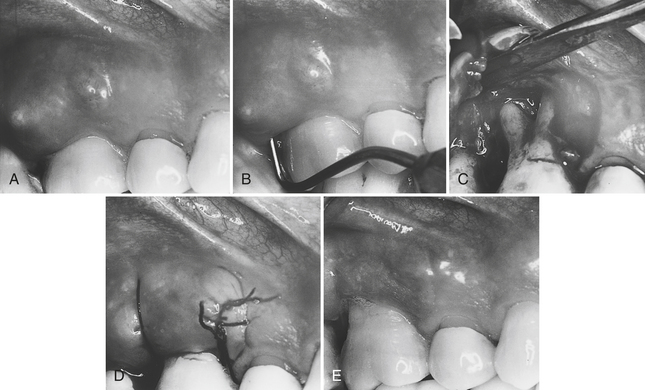

Figure 30-8 Surgical treatment of a chronic periodontal abscess associated with a furcation. A, Abscess associated with tooth 3 exhibits swelling and a fistula that is not draining. The tissue is very reddened, and the patient has intermittent severe pain. B, Periodontal probe inserted to show the depth of the pocket and determine its association with the buccal furcation. C, Flap reflected to permit access for debridement. Note the extent of the bone loss and depth of the furcation involvement. D, After debridement, the flap is sutured in place. E, Healing after 1 month shows tissue returned to normal color and consistency, and no evidence of the fistula. Note the recession that occurred following surgical treatment. This client must keep the teeth clean and return for frequent periodontal maintenance visits to preserve the tooth.

(Courtesy Philip R. Melnick.)

The dental hygienist plays a major role in educating the client about the chronic nature of this condition. The client is informed of the likelihood of increased bone loss and future acute episodes if no further treatment is performed, and the need for frequent maintenance care including scaling, root planing, and daily control of plaque biofilm. Often, discussing the risk of rapid bone loss during acute episodes of abscess helps the client value the need to seek further care and better preserve the teeth.11

Gingival Abscess

The gingival abscess usually occurs in previously disease-free areas and can often be related to forceful inclusion of some foreign body into the area. Most frequently, gingival abscesses are found on the marginal gingiva and are not associated with pathology of the deeper tissues.1

Signs and Symptoms

The gingival abscess can be observed on the marginal gingiva (see Box 30-4 for signs and symptoms). A pus-filled lesion that is not associated with the sulcular epithelium is often clearly seen. Figure 30-9 shows a gingival abscess in the otherwise healthy periodontium of a teenager.

Treatment

The gingival abscess must be drained and the foreign object removed by the dentist or periodontist. The acute lesion is incised and irrigated with saline solution. Sutures are not usually required. Warm saltwater rinses are recommended for postoperative therapy at home. The client must return for postoperative observation in about 24 hours, at which time the swelling should be greatly reduced and the acute tenderness subsided.

LESIONS OF ENDODONTIC ORIGIN

Lesion Types

The lesion of endodontic origin (LEO), the most common dental emergency,1 is also referred to as a dentoalveolar, apical, periapical, or endodontic abscess.12 Inflammatory processes in the periodontium associated with necrotic dental pulps have a clear infectious cause. In LEO the inflammatory processes are directed toward infectious components released from bacterial growth and bacterial disintegration in the root canal system.13 It is sometimes difficult to distinguish LEO from acute periodontal abscess because facial pain and tenderness to the tooth are similar. The endodontic abscess commonly results from infection of the pulpal tissues from caries, traumatic fracture of the tooth, or the trauma of a dental procedure. Pulpal infection can be spread laterally to a tooth from an adjacent infected tooth or infected periodontium, through the lateral canals.8

Microbiology

Most commonly the LEO is caused by microorganisms spreading into the pulp through the dentinal tubules from a carious lesion. However, the inflammatory processes in the periodontium occurring as a result of root canal infection may not only be localized at the apex, but also may appear along the lateral aspects of the root and in furcation areas of multirooted teeth.13 This type of lesion appears to be an infrequent event and does not seem to emerge at a rate that corresponds to the frequency with which lateral canals occur in the teeth.

Dissemination of the microorganisms and their toxic byproducts through the enamel to the dentinal tubules can be very rapid. Although microorganisms are the most common cause of pulpal disease, bacterial toxins also can initiate pulpal disease by penetrating through tubules with pores small enough to block bacteria.12,13 The toxins affect the odontoblastic cells and then penetrate into the pulp, initiating an inflammatory response. The bacterial cells also move toward the pulp by demineralizing the hard tooth structure with acids that they produce along the way. The microorganisms colonize in the pulp and produce a variety of toxins that result in pulp cell death. Bacteria and their metabolic products exit the apical foramen and can cause a localized formation of granulation tissue containing lymphocytes, plasma cells, mast cells, and other elements of the immune response. If the irritation continues, the granulation tissue gradually replaces the normal bone and periosteum at the apex of the tooth and gives rise to the common radiographic appearance of the LEO, a defined radiolucency at the apex of the affected tooth, called a periapical pathosis [PAP (Figure 30-10)].1

Figure 30-10 Lesions of endodontic origin. The radiographic appearance of an endodontic abscess associated with tooth No. 9 shows the classic appearance of radiolucency at the root apex. Note that the periodontal ligament does not appear to be intact around the apex of the tooth.

(Courtesy Edward J. Taggert.)

Characteristics and Treatment

Periapical Abscesses

There are both acute and chronic periapical abscesses. The acute periapical abscess occurs when bacteria or toxins rapidly enter the periradicular tissues, usually from the tooth pulp chamber. The confined abscess can cause severe pain. The pain may subside as the infection spreads toward a surface or space to provide relief to the tissues. Clients typically experience pain and swelling and may have systemic symptoms of infection, including osteitis (inflammation of the bone) or cellulitis (inflammation of cellular tissue, usually occurring in the loose tissues beneath the skin, in the mucous membranes, around muscle bundles, or around organs, which can be life-threatening). The chronic periapical abscess is associated with a more gradual introduction of irritants from the root canal to the periradicular tissues. The inflammatory response is intense, but the client gets relief from an either constantly or intermittently draining sinus tract.14 These usually drain into the mouth through a fistula in the bone or through the periodontal ligament, but they can also drain through the skin of the face. If the sinus tract is through the periodontal ligament and is left untreated, it will become a true periodontal pocket.1

Signs and Symptoms

The LEO is most identifiable on radiographs as a rounded radiolucency at the apex of the tooth. Figure 30-10 shows the typical appearance. However, early in the abscess formation the radiographic changes are often not obvious. If the LEO drains through a sinus duct in the cortical bone or through the periodontal ligament, it is likely to be much less identifiable on radiographs. LEOs that drain through the periodontal ligament can resemble acute periodontal abscesses because their symptoms are very similar, both exhibiting reddened tissue, swelling, and a sinus tract opening. It is often difficult to determine if the fistula opens into the periodontal pocket or goes to the apex of the tooth (Box 30-5).

In assessing an abscess to determine its origin, it is helpful to know that 85% of tooth pain is pulpal and 15% is periodontal. In addition, many teeth with lesions of endodontic origin are nonvital, which is a good distinguishing clue. However, some populations of clients likely to be treated by the dental hygienist, such as those treated in the periodontal practice, are much more likely to have periodontal than pulpal abscesses. Pain may be the distinguishing feature in differentiating between periapical and periodontal abscesses. Periapical pain is characterized as sharp, severe, intermittent, and hard to localize. In contrast, periodontal pain tends to be constant, less severe, and localized.1

Treatment

Treatment of apical abscesses requires either endodontic treatment to remove the pulp of the tooth and replace it with inert material, or extraction of the tooth. Untreated endodontic abscesses can lead to severe cases of brain abscess or fasciitis of the neck or chest wall that can be life-threatening.14 The dental hygienist has a responsibility to inform clients with untreated LEOs of the risk of delaying treatment. Clients without acute symptoms caused by draining of the abscess are likely to have the need for conceptualizing the disease process in order to pursue care and avoid further tissue destruction and ill effects from the infection. Table 30-1 summarizes LEO treatment strategies.

TABLE 30-1 Treatment Strategies for Apical Abscesses

| Cause | Condition of the Pulp | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Endodontic | Nonvital | Endodontic |

| Periodontal | Vital | Periodontal |

| Endodontic | Nonvital | Endodontic—first observe then later institute periodontal therapy if necessary |

Combination Abscesses

The periodontium is a continuous unit. Pathology at the apex of the tooth from infection of the root canal system can extend to the marginal tissues, and infection originating in the periodontal tissues can progress to the pulp through openings at the apex or through lateral canals. A true combination periodontal and periapical abscess is present when both of these infectious processes are present. Whatever the route or source of the infection, when both the periodontal and pulpal tissues are involved and the disease has abscess formation, the abscess is considered a combination periapical and periodontal abscess.1

Signs and Symptoms

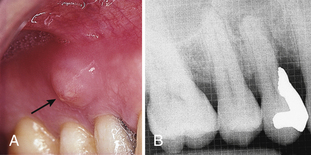

Combination abscesses cause some combination of the signs and symptoms described separately for periapical and periodontal abscesses. They are sometimes difficult to diagnose and can result in extensive damage to the surrounding periodontium because the intermittent nature of symptoms often causes clients to delay seeking treatment. The dentist diagnoses combination abscesses when symptoms of both pulpal and periodontal infection are identified. Figure 30-11 illustrates a combination abscess.

Figure 30-11 Combined periapical and periodontal abscess. The combined abscess is associated with tooth No. 5. It could have occurred from the spread of pathologic microorganisms from the deep pockets to the tooth pulp, the caries process, or trauma from placement of the very deep restoration. A, The sinus tract (fistula) emerges into the oral cavity. B, Radiolucency at the apex and significant bone loss appear on the radiograph.

(Courtesy Philip R. Melnick.)

Treatment

The most common form of treatment for periapical and periodontal abscesses is surgical exposure of the area including removal of the granulation tissue.13 Combination abscesses require treatment of both sources of infection. Both periodontal and endodontic therapy are indicated to preserve the tooth. In some cases the periodontal tissue destruction is so severe that the tooth must be extracted even though endodontic therapy could be performed successfully.15

HERPETIC INFECTIONS

More than 80 herpes viruses have been identified,16 eight of which are known human pathogens.17

Herpes simplex viruses belong to the ubiquitous Herpesviridae family of viruses, which contains herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus, as well as human herpesviruses and Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpes virus (type 8).16,17

Herpesvirus infection occurs worldwide, has no seasonal variation, and affects only humans naturally. The prevalence of HSV-1 infection increases gradually from childhood, reaching 60% to 95% of human adults.

Primary HSV-1 infection in oral and perioral sites usually manifests as gingivostomatitis, whereas reactivation of the virus in the trigeminal sensory ganglion gives rise to mild cutaneus and mucocutaneous disease, often termed recurrent herpes labialis.18,19

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Irrespective of the viral type, HSV primarily affects skin and mucous membranes.20 Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (PHGS) is the most common orofacial manifestation of HSV-1 infection and is characterized by oral and/or perioral vesiculoulcerative leasions.21 Although herpetic gingivostomatitis is a self-limiting disease, affected individuals may experience severe pain and be unable to eat or drink.

The virus is spread by physical contact, but there is no documentation that it can be spread through the airborne droplet route, contaminated water, or contact with inanimate objects. Most people encounter the virus and never show signs or symptoms of primary infection.20 It is known that up to 90% of the population has antibodies to HSV-1.

PHGS typically develops after first-time exposure of seronegative individuals or those who have not produced adequate antibody response during a previous infection with either of two HSVs.16,19

A majority of infections are subclinical. Although PHGS typically affects children between the ages of 1 and 5 years, occasional cases of primary infection affecting adults also occur.16 Infants are passively protected through maternal immunity for the first 6 months of life. The clinical manifestations of the infection, whether from HSV-1 or HSV-2, may lead to primary oral infection; nearly all are caused by HSV-1.19,20 The majority of HSV-1–induced primary orofacial infections are subclinical and therefore unrecognized.21 Symptomatic PHGS is typically preceded or accompanied by a sensation of burning or paresthesia at the site of inoculation, cervical and submandibular lymphadenopathy, fever, malaise, myalgia, loss of appetite, dysphagia, and headache. The most characteristic signs present are acute, generalized, marginal gingivitis with the inflamed gingiva appearing erythematous and edematous. Most clients with primary herpetic infections never experience the secondary or recurrent forms. In healthy individuals, primary infection has an excellent prognosis, with recovery expected within 10 to 14 days.17-19 Nevertheless, the painful herpetic ulcers in the mouth associated with primary infection often cause reduction in food and fluid intake, creating a human need for the prevention of health risks that accompany this disease. Nutritional deficits can be critical in children and infants. Serious dehydration is not uncommon and can lead to hospitalization of infants.

Signs and Symptoms

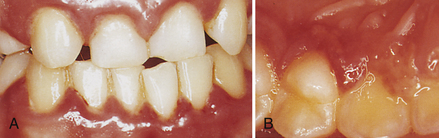

Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis is recognized by a set of characteristic systemic and intraoral signs and symptoms (Box 30-6). The vesicular eruptions may occur on the skin, vermilion border, or oral mucous membranes. Intraorally, they may appear on any mucosal or gingival surface, the hard palate, and alveolar mucosa or any other area of oral soft tissue.18 The discrete grayish vesicles rupture and coalesce within 24 hours to form ulcers. The ulcers have a red, elevated, “halolike” margin with a depressed yellow or gray central area. They are teeming with shedding virus. Figure 30-12 exemplifies the intraoral appearance of primary herpetic infection in a teenager. The disease is commonly associated with systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, headache, and cervical lymphadenopathy.16

BOX 30-6 Signs and Symptoms of Acute Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Figure 30-12 Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. This oral infection of the mouth is characterized by bright red gingiva, vesicles, and pain. A, Facial gingiva showing swelling and color change. B, Lingual view of premolar and anterior teeth showing coalesced vesicles.

(Courtesy Philip R. Melnick.)

Recognition of PHGS is based on knowledge of the appearance of the ulcers and assessment of systemic manifestations. Diagnostic tests, such as culturing for herpesvirus by the client’s physician, can be conducted for confirmation of the presence of the virus but are not routine. In addition, this is a highly infectious disease; therefore the dental hygienist and client, and the client’s parents in the case of children, must work together to prevent transmission of the virus to family members and other members of the oral healthcare team. Figure 30-13 shows a more unusual presentation of primary herpetic infection on the skin of the face.

Treatment

Treatment of gingival inflammation and any other elective dental care should be postponed until the PHGS has run its course. The client is assessed by the dentist to obtain a definitive dental diagnosis. Management of acute herpetic gingivostomatitis is entirely supportive because of the infectious nature of the disease and the fact that it runs its course in 7 to 10 days. The client should be instructed to rest, take fluids, and make every effort to eat a nutritious diet. The client should also try to clean the teeth at home with an extra-soft toothbrush if it can be tolerated.19

Professional care should not be performed because of the risk of transmission of the virus to other head and neck areas of the client, or to the dental hygienist and other workers. Even if the hygienist was previously exposed to the herpes virus or has had an episode of initial infection with or without recurrent lesions, the dental hygienist can still be inoculated with the virus by an inadvertent finger puncture with an HSV-contaminated instrument. This infection could result in the development of herpetic whitlow (Figure 30-14). Herpetic whitlow is a recurrent herpetic lesion of the finger that can be extremely painful and debilitating. The whitlow can last many weeks longer than the usual 2-week course of herpes virus infection in the oral tissue.1

The dental hygienist educates the client about consuming adequate fluids and soft, nutrient-dense foods; performing oral hygiene as much as possible at home; and using over-the-counter topical anesthetics and systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflamatory agents to minimize discomfort. The client can swab topical anesthetics onto the lesions for controlled local delivery. Topical anesthetics should be used cautiously with children so as not to anesthetize the throat, which can be frightening to them.

Recurrent Oral Herpes Simplex Infections

After primary infection, latent HSV reactivates periodically, migrating from the sensory ganglia to cause recurrent oral or genital herpes.17-19 Despite the high prevalence of HSV-1 in the population, only 15% to 40% of seropositive patients ever experience symptomatic mucocutaneous recurrence.17-19 An individual’s genetic susceptibility, immune status, age, anatomic site of infection, initial dose of inoculums, and viral subtype appear to influence frequency of recurrence. Compared with primary infections, recurrent episodes are milder and shorter in duration with minimal systemic involvement.20

Clients often arrive for dental hygiene appointments when they have recurrent herpetic lesions. These lesions are quite common, as previously mentioned, and do not interfere with activities of daily living, so clients are frequently unaware of the nature of the event. The typical recurrent lesion is on the lip and is referred to as herpes simplex labialis (HSL). Common names such as fever blister and cold sore reflect the public understanding of what precipitates these recurrences. Unfortunately, they are extremely innocuous names for lesions with serious potential effects for the dental hygienist.

Signs and Symptoms

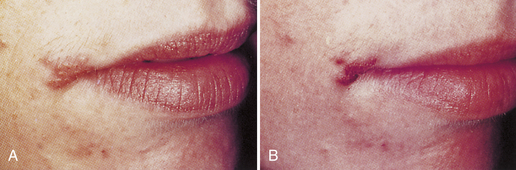

Clients often have prodromal symptoms of burning, tingling, or pain in the site where the lesion recurs (Box 30-7). Within hours of the prodromal symptoms, vesicles appear, which become ulcerated and coalesce into a large ulcer or ulcers. The lesions heal without scarring in about 14 days and can recur as often as once per month. Typically lesions will recur in the same place on the vermilion border and skin around the face. Figure 30-15 is an example of a recurrent herpetic lesion.

Figure 30-15 Recurrent herpetic infection on the lip—“cold sore.” Clients frequently do not recognize these lesions as recurrent herpetic infections that are highly contagious. A, Herpes labialis 12 hours after onset. B, Herpes labialis 48 hours after onset.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Treatment

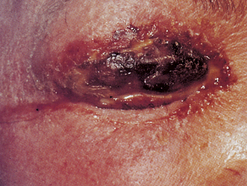

Recurrent lesions shed vast amounts of herpes virus. For this reason the dental hygienist must not treat the client while the lesions are present. Sometimes this can be very disconcerting because it may require reappointing a client who has waited months for an appointment. However, the dental hygienist is placed at great risk of inoculation, just as with primary herpetic infections. Not only are herpetic whitlow lesions a possibility, but the virus is also shed in the saliva, meaning that spatter during treatment can be hazardous. Figure 30-16 is an example of a recurrent herpetic infection of the cornea acquired from spatter.

Figure 30-16 Recurrent herpetic infection of the cornea. Without protective eyewear and standard precautions, calculus and other contaminants can enter the eye of the dental hygienist or client and infect the cornea with herpesvirus. Recurrences are extremely painful and last months. Partial loss of sight and disability can occur.

(Courtesy Dr. Sidney Eisig; from Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Treatment of the herpetic lesion is entirely supportive. There are some antiviral agents available by prescription (e.g., acyclovir) that the client may benefit from using. These agents can reduce the extent and duration of the recurrence. The dental hygienist should inform the client of this possibility and refer the client to the physician or dentist for further information.

It is extremely important for the client to be educated about these lesions and the client’s responsibility for preventing the spread of infection. Clients who have common recurrences are often aware of the prodromal symptoms and should be informed to call and reschedule dental appointments until the disease runs its course.

Recurrent herpetic lesions can occur intraorally and usually appear on the soft palate.21 These lesions sometimes erupt after therapeutic scaling and root planing when repeated palatal injections have been given to the client to achieve anesthesia. The client will either call or return for a subsequent appointment and the typical oral ulcers will be evident in the area where the injections were given. Figure 30-17 is an example of recurrent palatal herpes subsequent to periodontal therapy in the maxillary arch. This situation requires the same management as other herpetic episodes. The client should not be treated until the lesions have healed, and the client must be educated about the situation.

Figure 30-17 Recurrent herpetic infection of the palate.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Recurrent intraoral herpetic lesions can almost always be easily distinguished from the more commonly occurring aphthous ulcers. Reviewing the client history for recent trauma or illness may be helpful, but either lesion can result. The more distinguishing characteristic is that recurrent herpetic lesions almost always occur on the gingiva or hard palate, and aphthous ulcers almost always appear on the movable mucosa.

PERICORONITIS

Pericoronitis is soft-tissue inflammation associated with a partially erupted tooth. It may be acute, subacute, or chronic in nature.22 The most commonly affected tooth is the mandibular third molar, but maxillary third molars and other teeth that are the most distal in the arch have been associated with the disease. The flap of tissue that either completely or partly covers the associated tooth is called an operculum. The space between the flap of tissue and the tooth is an ideal location for food debris to collect and bacteria to grow. As bacteria increasingly infect the area, the tissue responds by becoming extremely inflamed and painful.16 There is constant inflammation in the area, so it is always considered subacute or chronically infected even if the acute symptoms are not present.22,23

Acute pericoronitis involves an extremely high degree of inflammation in the local area. As inflammation increases, the tissue swells and can interfere with the complete closing of the jaws. This can lead to added trauma, increased inflammation, and severe pain. The tissue becomes quite red, suppuration is evident, and the pain can radiate to the throat and ear.

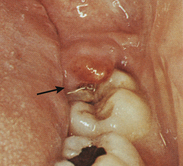

This disease is a common problem associated with young adults and has been considered to be a serious problem for military personnel, most of whom are in the 17- to 26-year-old group. In fact, 20% of dental emergencies reported by the military in World War II and 16% of those from the Vietnam conflict were acute pericoronitis.1 Figure 30-18 is an example of acute pericoronitis.

Figure 30-18 Pericoronitis. This condition is most commonly found in the third molar region and can be extremely painful. Note the swelling of the soft tissue distal to the second molar. Clinically the tissue is intensely red.

Signs and Symptoms

Oral areas that have an operculum are predisposed to pericoronitis and typically exhibit chronic signs of the disease, increased redness, and some exudate (Box 30-8).

The tissue may be so swollen that it interferes with mastication and is easily traumatized during eating. The infection can extend very deeply into the tissues and cause peritonsillar abscess formation, cellulitis, and Ludwig’s angina.15 These signs are rare sequelae but emphasize the importance of recognition and treatment of the lesions.

A review of military studies documents the extent of symptoms associated with pericoronitis. In a military study of 359 recruits, pain, swelling, and redness were present in every instance. Purulent exudate was reported in half the cases, few of the patients bled on palpation, and no individual in that population had a fever. In addition, two thirds of 25 cases in the naval population reported previous episodes of pericoronitis, suggesting that pericoronitis is often a recurrent problem.22,24

Treatment

A number of considerations are involved in treating pericoronitis, including the severity of the case, whether it is a recurrence, and possible systemic complications. The dentist may ask the dental hygienist to participate in the care of the client with pericoronitis, which requires multiple visits.

Initial dental management is aimed at treating symptoms with the goal of making the client more comfortable. The infected area is debrided, usually by gentle flushing with warm water or dilute hydrogen peroxide delivered in a disposable irrigating syringe with a blunt needle. Topical anesthetic is applied first. Much tissue manipulation may not be possible, but the tissue needs to be lifted away from the tooth to permit as much debridement as is tolerable at the first treatment appointment.1 After this initial debridement the client is instructed to rest at home, use warm saltwater rinses, and drink fluids to avoid dehydration. The dentist may prescribe antibiotics if the client is febrile or if there is cervical lymphadenopathy. The client is asked to return the next day. At the second visit, the area is irrigated again and instrumented if possible, and more thorough homecare is initiated. A marked improvement is usually observed at the second appointment.

After the acute condition has resolved, the client is assessed by the dentist to determine further treatment. Dental treatment might include extraction of the offending third molar or operculum removal to produce a more normal gingival contour if the tooth is to be retained.25

The presence of any operculum is assessed and viewed with suspicion. There is almost always some amount of inflammation present, and the potential for acute exacerbation is likely. The dental hygienist informs clients of the potential of the condition to permit them to understand the situation and take responsibility for their oral health.

NECROTIZING PERIODONTAL DISEASES

Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) has been reported widely and is not uncommon in developing countries.26 Classical diagnostic features include ulceration and necrosis of the interdental papillae, pain, and spontaneous gingival bleeding. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases are clinically recognizable diseases distinct from chronic periodontitis. Until 199918 the condition was most commonly called acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis or just necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG). However, the disease is often associated with attachment loss, making the term gingivitis inaccurate, so the disease is now referred to as necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP). It is not certain whether or not the conditions with attachment loss are separate diseases from those confined to the gingiva, so the consensus is to use the more general disease name of necrotizing periodontal diseases.

Necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases are opportunistic infections of the gingiva that are associated with lifestyle risk factors such as stress and tobacco use, and also systemic conditions such as blood dyscrasias, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and Down syndrome.26

The disease was first described by Vincent in the late nineteenth century and was so common among troops fighting in trenches in Europe during World War I that the name trench mouth was adopted. It was primarily seen in young adult individuals and was thought to be communicable.27 The disease, however, is not communicable, infectious, or spread through direct contact. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases are recognized to be recurrent diseases with complex bacteriology consisting of a large proportion of spirochetes and gram-negative organisms. The consistent presence of specific bacteria, fusobacteria, and spirochetes has suggested the cause could be explained in microbiologic terms. These organisms invade the tissue, causing the characteristic appearance of the disease. Other contributory factors implicated include poor oral hygiene, mouth breathing, smoking, stress, sepsis, malnutrition, and systemic diseases including hormonal imbalance and alterations in lymphocyte and neutrophil function.26,27

Signs and Symptoms

Necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases have specific clinical characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of acute oral infections. The clinical appearance of the disease is one of cratered or “punched-out” papillae, very reddened gingivae, and pain. There is often a collection of debris, dead cells, and bacteria on the gingival surface that appears gray and is referred to as the pseudomembrane. The gingival lesions may be localized to specific areas or generalized throughout the mouth, and they progressively destroy the gingiva and underlying periodontal structures. Clients frequently exhibit an extremely offensive and fetid breath odor that can be smelled anywhere in the room occupied by the client. They may also complain of a thick or pasty texture to the saliva. In addition, the acute lesions can be extensive, covering parts of the face, as seen in developing countries when associated with malnutrition. Figure 30-19 shows the clinical oral features of NUP.

Figure 30-19 Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. The classic intraoral signs of this disease—redness, cratered papillae, pseudomembrane, and spontaneous hemorrhage—appear in the anterior areas.

The three most reliable criteria for recognizing the disease are as follows:

Other symptoms have been recognized as strongly associated with the disease (Box 30-9).

Stress is often related to both initial occurrence and recurrence of this disease. The role of psychologic factors involved with stress is not well understood, but it has been postulated that changes in the immune system occurring at stressful times predispose certain individuals to an exuberant bacterial response, resulting in necrotizing ulcerative disease.

Treatment

The course of a single episode of NUP is usually short but painful. Clients come to the oral care setting most often because of pain. Because of the cyclic and recurring nature of the disease, treatment focuses on microbial control through mechanical debridement by both client and clinician. It also requires consultation with the client’s physician because of possible predisposing systemic factors such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.15 Treatment should progress daily during the acute phase of the disease because the pain often inhibits thorough cleaning by the client or the dental hygienist at one time. Treatment includes periodontal debridement with ultrasonic scalers, plaque biofilm control, and 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses twice daily. The dentist may prescribe a systemic antibiotic if fever and lymphadenopathy are present. The recommended treatment sequence is described in Table 30-2.

TABLE 30-2 Treatment Regimen for Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis

| Day 1 | First visit: oral therapy | Scale and debride as much as possible.Mechanized (ultrasonic) instruments may be more easily tolerated than hand-activated scalers.Use topical anesthetic as needed.Provide plaque control instruction.Frequent rinsing with a mixture of warm water and 3% hydrogen peroxide is soothing and oxygenates the pseudomembranous plaque. |

| Day 1 | Systemic therapy | Review health history for underlying conditions, and consult with physician as needed.The use of an antibiotic such as penicillin, erythromycin, or metronidazole is indicated if the client has fever and cervical lymphadenopathy. |

| Day 2 | Second visit | Pain should be reduced considerably.Continue to remove calculus to the limit of the client’s tolerance.Oral hygiene instructions should be reinforced.The home rinsing regimen should be continued. |

| Days 4-7 | Third visit | Therapeutic scaling and root planing should be completed, taking as many appointments as necessary.Oral hygiene must be reinforced.Hydrogen peroxide rinses can be discontinued.Continue on 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinse twice daily for 2-3 weeks. |

| Month 1 | Reevaluation for continued care | Reinforce oral hygiene.Scale and root plane if necessary.Meticulous and regular debridement by the client and the dental hygienist to control bacterial pathogenicity is required.Cratering frequently occurs and can result in significant gingival defects that should be evaluated by the dentist for possible surgical correction. |

| Month 3 | Periodontal maintenance therapy | Regular professional mechanical dental hygiene care should be encouraged to minimize the risk of recurrence.Continued-care interval should be 2-4 months. |

Given the signs and symptoms, most clients with necrotizing periodontal diseases have unmet human needs in the areas of freedom from head and neck pain, skin and mucous membrane integrity of the head and neck, and conceptualization and problem solving. Client health and oral health and well-being are the keys to successful treatment of these diseases. Clients must be knowledgeable about the roles of stress, bacteria, and nutrition in the disease process and encouraged to take control of their oral health and lifestyle behaviors. Suggestions to identify stress management techniques and improve nutrition are necessary components of dental hygiene care (see Chapters 33 and 37).

AVULSED TOOTH

Prevalence

Avulsion of permanent teeth is the most serious of all dental injuries. The avulsed tooth is one that is separated from the alveolar bone by trauma.28 Avulsed teeth, though not strictly periodontal emergencies, are traumatized teeth that can be replanted successfully if managed properly. The prognosis depends on the measures taken at the place of accident or at the time immediately after avulsion. In some cases the dental hygienist may be the first person in the dental profession meeting the patient. The dental hygienist may in this situation have the opportunity to help a parent of a small child or a student or adult participating in athletic activities to preserve an avulsed tooth through quick action.

Traumas to the oral region occur frequently and comprise 5% of all injuries for which people seek treatment In preschool children the figure is as high as 18% of all injuries. Avulsion is the most common dental injury to children younger than 15 years of age. The situation occurs in as many as one in every 200 American children, approximately 2 million occurrences per year. Among all facial injuries, dental injuries are the most common; avulsions occur in 1% to 16% of all dental injuries.28 Replantation is the treatment of choice but cannot always be carried out immediately. To meet the client’s need for a biologically sound and functional dentition, it is incumbent on the dental hygienist to respond to this dental emergency. However, the dental hygienist should take responsibility to inform parents, children, students, and adults participating in athletic activities to use mouth protectors to prevent oral injuries. In addition, information should be given to teachers and coaches about the risk of oral injuries at some of the sports activities. Furthermore, replantation should not be performed when primary teeth have been avulsed because of the risk of injury to the underlying permanent tooth germ.28,29

An appropriate treatment plan after an injury is important for a good prognosis. Guidelines are useful for dental hygienists, dentists, and other healthcare professionals in delivering the best care possible in an efficient manner. The International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) has developed a consensus statement from the dental literature and group discussions. Lost time and improper handling of the avulsed tooth can substantially reduce long-term success of replantation. Moreover, the dental hygienist should inform parents, teachers, and coaches about the procedure so increased awareness can improve the opportunity for successful tooth replantation when injuries causing avulsed teeth occur.

Hence, good healing after an injury to the teeth and oral tissues depends, in part, on good oral hygiene. Patients should be advised on how best to care for teeth that have received treatment after injury. Brushing with a soft brush and rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine is beneficial to prevent accumulation of plaque and debris.

The procedure for constructing a custom-made athletic mouth protector is described in Chapter 35, Procedure 35-7. Athletic mouth protectors are highly recommended to prevent tooth avulsion.

Treatment

The dental hygienist might be present at a sporting event or other venue when a tooth is traumatically avulsed or might have a child who experiences a traumatically avulsed tooth. The avulsed tooth is quickly separated from the alveolus from a fall or a strike of some kind. Typically, a layer of periodontal ligament cells remains on the cemental surface of the avulsed tooth and on the bone in the socket because of the very fast occurrence of the trauma. Successful treatment of avulsed teeth by replantation is dependent on rejoining intact periodontal ligament cells covering the cementum of the tooth to those remaining in the socket.

The object of this emergency treatment is to promote healing of the periodontal ligament once the tooth is replanted in the socket. To maximize the chances of healing, the tooth must be handled only by the crown to prevent damage to the remaining periodontal ligament cells. It is essential that the avulsed tooth not dry out and that it not be debrided in any way. As little as 1 hour of dry storage before replantation negatively affects the success rate of the procedure.28,29

The ideal place to store and transport the avulsed tooth is in the socket, if it can be gently placed and held there while the client is taken to an oral healthcare setting or a hospital emergency room. The socket provides the most nutritious environment for the cells of the periodontal ligament, thereby increasing their survival rate. If it is not possible to replace the tooth temporarily in the socket because of other injuries associated with the trauma, or emotional upset, physiologic saline is a safe alternative. Unfortunately, it may not be handy. Milk is also a good medium because it has physiologic osmolality and relatively few bacteria. Saliva has more bacteria than milk, but is a good way to keep the tooth moist. However, the client may be too upset or too young to hold the tooth in the mouth. Warm saltwater can prevent dehydration but cannot keep the cells alive long. Air-drying or wrapping the tooth in gauze or other materials, even for a short time, is contraindicated because that will kill the periodontal ligament cells.6 Alternatives may have to be thought through quickly, and a decision made during a stressful situation, to avoid dehydration and death of cells. The options for storage and transportation of the avulsed tooth are highlighted in Table 30-3.

TABLE 30-3 Storage of Avulsed Teeth during Transportation for Treatment

| Choice | Transportation Medium |

|---|---|

| First | Replace in socket |

| Second | Store in physiologic saline |

| Third | Store in cold, fresh milk |

| Fourth | Place in the individual’s mouth, under the tongue or in the cheek |

| Fifth | Store in warm saltwater |

| Sixth | Store in tap water |

At the emergency treatment facility the tooth is removed from its transport medium, gently rinsed if necessary, replanted in the socket after the blood clot is removed, and splinted into place. A 5- to 7-day course of systemic antibiotics typically used for dental infections is prescribed. Endodontic procedures need to be performed at a later time, usually about 2 weeks after replantation, to avoid inflammatory root resorption.28 The protocol to manage the avulsed tooth is presented in Procedure 30-1. A comparative summary of the conditions presented in this chapter can be found in Table 30-4.

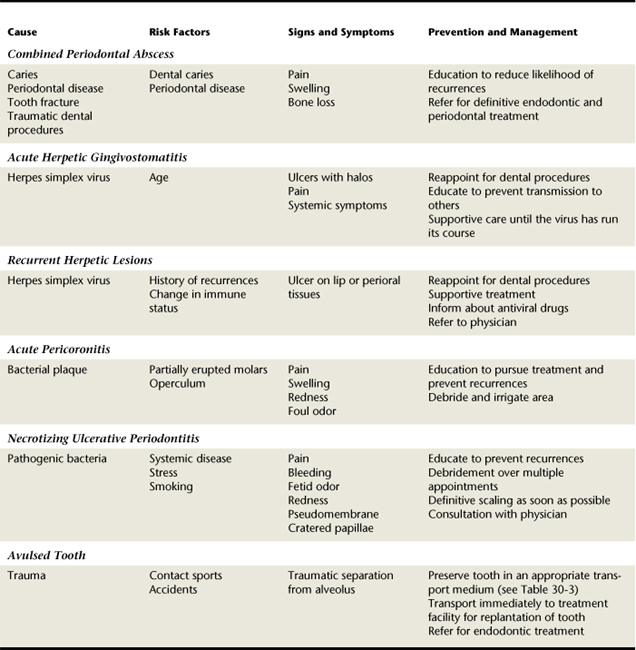

TABLE 30-4 Summary Comparison of Acute Gingival and Periodontal Conditions, Lesions of Endodontic Origin, and Avulsed Teeth

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Educate clients about disease transmission and lifestyle influences, particularly related to the herpes virus and necrotizing periodontal diseases.

Educate clients about disease transmission and lifestyle influences, particularly related to the herpes virus and necrotizing periodontal diseases. Educate clients with painful oral infections to consume adequate fluids and nutrient-dense foods, perform oral hygiene, and use over-the-counter topical anesthetics to control discomfort.

Educate clients with painful oral infections to consume adequate fluids and nutrient-dense foods, perform oral hygiene, and use over-the-counter topical anesthetics to control discomfort. Teach clients with a history of recurrent herpetic infection to cancel dental appointments when an active oral lesion is present.

Teach clients with a history of recurrent herpetic infection to cancel dental appointments when an active oral lesion is present. Review methods and treatment to prevent the recurrence of pericoronitis and necrotizing periodontal diseases.

Review methods and treatment to prevent the recurrence of pericoronitis and necrotizing periodontal diseases.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Dental hygienists have a legal responsibility to recognize emergency conditions, make appropriate referrals, and treat those conditions within the scope of dental hygiene practice (see Chapter 8).

Dental hygienists have a legal responsibility to recognize emergency conditions, make appropriate referrals, and treat those conditions within the scope of dental hygiene practice (see Chapter 8). Dental hygienists have an ethical responsibility to educate clients about the significance of their diseases and the potential for recurrence and infection of others.

Dental hygienists have an ethical responsibility to educate clients about the significance of their diseases and the potential for recurrence and infection of others.KEY CONCEPTS

Lesion of endodontic origin (LEO) is a serious infection that requires consultation and referral for immediate treatment. Left untreated, LEO could develop into a brain abscess or fasciitis of the neck or chest wall, which can be life-threatening.

Lesion of endodontic origin (LEO) is a serious infection that requires consultation and referral for immediate treatment. Left untreated, LEO could develop into a brain abscess or fasciitis of the neck or chest wall, which can be life-threatening. Periodontal abscesses have a pathogenic microflora similar to that associated with periodontal diseases.

Periodontal abscesses have a pathogenic microflora similar to that associated with periodontal diseases. Incomplete subgingival scaling and root planing has been suggested as a cause of periodontal abscesses; however, there are few data to support this assumption.

Incomplete subgingival scaling and root planing has been suggested as a cause of periodontal abscesses; however, there are few data to support this assumption. Abscesses can point and drain through the tissue or simply drain through the periodontal pocket opening.

Abscesses can point and drain through the tissue or simply drain through the periodontal pocket opening. Infection moves through tissue along the pathway of least resistance; therefore clinical features of the infection may appear at a distance from the affected tooth.

Infection moves through tissue along the pathway of least resistance; therefore clinical features of the infection may appear at a distance from the affected tooth. Pain may be the key feature distinguishing between periapical and periodontal abscesses. Periapical pain is sharp, severe, intermittent, and hard to localize; periodontal pain is constant, less severe, and localized.

Pain may be the key feature distinguishing between periapical and periodontal abscesses. Periapical pain is sharp, severe, intermittent, and hard to localize; periodontal pain is constant, less severe, and localized. Primary and recurrent herpetic infections are serious but self-limiting conditions that require postponement of elective dental hygiene and dental treatment. Dental hygiene care should not be performed on a client with a herpetic infection because of the risk of transmission of the virus to the dental hygienist and other workers.

Primary and recurrent herpetic infections are serious but self-limiting conditions that require postponement of elective dental hygiene and dental treatment. Dental hygiene care should not be performed on a client with a herpetic infection because of the risk of transmission of the virus to the dental hygienist and other workers. Necrotizing periodontal diseases are complex processes that benefit from the dental hygiene process of care.

Necrotizing periodontal diseases are complex processes that benefit from the dental hygiene process of care.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Dorothy A. Perry for her past contributions to this chapter.

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedure presented in this chapter.

1. Newman M.G., Takei H.H., Klokkevold P.R., Carranza F.A., editors. Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis: Saunders, 2006.

2. Lopatin A.S., Sysolyatin S.P., Sysolyatin P.G., Melnikov M.N. Chronic maxillary sinusitis of dental origin: is external surgical approach mandatory? Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1056.

3. Cantatore J.L., Klein P.A., Lieblich L.M. Cutaneous dental sinus tract, a common misdiagnosis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2002;70:264.

4. Hersh E.V., Moore P.A. Adverse drug interactions in dentistry. Periodontology 2000. 2008;46:109.

5. Socransky S.S., Haffajee A.D. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontology 2000. 2005;38:135.

6. Paster B.J., Olsen I., Aas J.A., Dewhirst F.E. The breadth of bacterial diversity in the human periodontal pocket and other oral sites. Periodontology 2000. 2006;42:80.

7. Suvan J. Effectiveness of mechanical nonsurgical pocket therapy. Periodontology 2000. 2005;37:48.

8. Herrera D., Roldán S., González I., Sanz M. The periodontal abscess. I. Clinical and microbiological findings. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:387.

9. Renvert S., Persson R. Supportive periodontal therapy. Periodontology 2000. 2004;36:179.

10. Claffy N., Polyzois I., Ziaka P. An overview of nonsurgical and surgical therapy. Periodontology 2000. 2004;36:35.

11. Nair P.N. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J. 2006;39:249.

12. Gomes B.P., Jacinto R.C., Pinheiro E.T., et al. Molecular analysis of Filifactor alocis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola associated with primary endodontic infections and failed endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2006;32:937.

13 Caliskan M.K. Nonsurgical retreatment of teeth with periapical lesions previously managed by either endodontic or surgical intervention. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:242.

14. Mylonas A.I., Tzerbos F.H., Mihalaki M., et al. Cerebral abscess of odontogenic origin. Case report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2007;35:63.

15. Nair P.N. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:348.

16. Fatahzadeh M., Schwartz R.A. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:737.

17. Steben M., Duarte-Franco E. Human papillomavirus infection: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(2 Suppl):S2.

18. Woo S.B., Challacombe S.J. Management of recurrent oral herpes simplex infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl):S12.

19. Wu I.B., Schwartz R.A. Herpetic whitlow. Cutis. 2007;79:193.

20. Slots J. Herpesviruses in periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000. 2005;38:3.

21. Yin M.T., Dobkin J.F., Grbic J.T. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management of human immunodeficiency virus infection in patients with periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000. 2007;44:55.

22. Yamalik K., Bozkaya S. The predictivity of mandibular third molar position as a risk indicator for pericoronitis. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12:9.

23. White R.P.Jr. Progress report on third molar clinical trials. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:377.

24. Kunkel M., Kleis W., Morbach T., Wagner W. Severe third molar complications including death—lessons from 100 cases requiring hospitalization. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:1700.

25. Dogan N., Orhan K., Gunaydin Y., et al. Unerupted mandibular third molars: symptoms, associated pathologies, and indications for removal in a Turkish population. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:e497.

26. Folayan M.O. The epidemiology, etiology, and pathophysiology of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis associated with malnutrition. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2004;5:28.

27. Arendorf T.M., Bredekamp B., Cloete C.-A., Joshipura K. Seasonal variation of acute necrotising ulcerative gingivitis in South Africans. Oral Dis. 2001;7:150.

28. Flores M.T., Andersson L., Andreasen J.O., et al. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. II. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23:130.

29. Ram D., Cohenca N. Therapeutic protocols for avulsed permanent teeth: review and clinical update. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:251.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..