CHAPTER 41 Persons with Disabilities

“Special healthcare needs” include a broad spectrum of physical, developmental, mental, sensory, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional impairments that require medical management, healthcare interventions, and/or use of specialized services or programs. About 54 million disabled people in the United States have special healthcare needs. This number is expected to increase dramatically as the population ages. Disabled individuals who previously might have succumbed to childhood illnesses, chronic health conditions, infectious diseases, and/or severe trauma are living well into adulthood and old age. This trend creates an overwhelming demand for health and rehabilitation services.

Disabilities are often associated with elderly people; however, an individual can be disabled at any time during the lifespan. Common misconceptions about individuals with disabilities are that they are sick, are dependent on others, are mentally and physically debilitated, or live in institutions. In reality, most of these individuals are capable of living within the community either alone or with assistance. The trend has been to transition these individuals into the local community; normalization is a process that enables challenged individuals to engage in normal patterns of every day life. The outcome is mainstreaming, which means incorporating individuals with special needs into conventional activities. This concept promotes deinstitutionalization of challenged persons and allows them to live and function independently with little or no assistance from a caregiver. Mainstreaming is the goal of long-term care providers and educators assisting people with disabilities.

Mainstreaming disabled people creates a host of problems—problems that demand attention and resources. Disabled individuals encounter obstacles to healthcare, education, and employment opportunities. Access to these services is essential for persons to function at an acceptable level of health and wellness and to maintain independence. Nationwide networks and organizations are instrumental in influencing standards to achieve equal opportunities for the disabled.

LEGISLATION FOR DISABLED PERSONS

Numerous legislative policies enable disabled individuals access to goods and services as well as healthcare, for example, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, the Olmstead Decision of 1999, and the New Freedom Initiative of 2001 (Table 41-1). Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the ADA achieved the most significant outcomes in removing barriers for the disabled by guaranteeing that no otherwise qualified person shall, by reason of his or her handicap, be discriminated against in the areas of education, employment, or social services including healthcare.

TABLE 41-1 Disability Legislation

| Year | Law | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Rehabilitation Act, Section 504 | First federal statute that defined discrimination toward people with disabilities; no qualified individual shall be excluded, denied, or subjected to discrimination under any program or activity that receives federal financial assistance. |

| 1975 | Education for All Children Act | Mandated free, appropriate public education for children with disabilities; introduced the concept of mainstreaming disabled into society. |

| 1980 | Air Carrier Act | Prohibits discrimination in air transportation by domestic and foreign airline carriers against individuals with physical or mental impairments. |

| 1988 | Fair Housing Act | Prohibits housing discrimination and ensures that there is no discrimination in selling, renting, or denying a dwelling to a buyer or renter because of his or her disability. |

| 1990 | Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) | Most comprehensive federal statute that protects the rights of people with disabilities; prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in employment, state and local government, public accommodations, commercial facilities, transportation, and telecommunications. |

| 1996 | Telecommunications Act | Requires manufacturers of telecommunications equipment and providers of telecommunication services to make equipment and services accessible and usable by persons with disabilities. |

| 1997 | Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act | Authorizes the United States Attorney General to investigate conditions of confinement at state and local government institutions such as prisons, jails, pretrial detention centers, juvenile detention centers and correctional facilities, publicly operated nursing homes, and institutions for people with psychiatric or developmental disabilities. |

| 1999 | Olmstead Decision | The United States Supreme Court ruled that institutionalizing individuals with disabilities who are able to participate in and benefit from community settings is a form of discrimination. This decision opened the doors to people with disabilities who would like to live in and be active participants in their communities. |

| 2000 | Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act | Ensures that (1) individuals with disabilities participate in their communities through integration and inclusion in the economic, political, social, cultural, religious, and educational sectors of society, and (2) individuals with disabilities and their families participate in the design of and have access to culturally competent services, supports, and other assistance and opportunities that promote independence, productivity, integration, and inclusion in the community. |

| 2001 | New Freedom Initiative | This initiative was a nationwide effort to remove barriers to community living for people of all ages with disabilities and long-term illnesses. It was designed to help ensure that all Americans have the opportunity to learn, develop skills, engage in productive work, choose where to live, and participate in community life. |

| 2004 | Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act | Mandates that eligible children with disabilities have available to them free and appropriate public education; education should be designed to meet the unique needs of disabled children and provide transportation and other supportive services. |

The most significant policy statements regarding healthcare for individuals with disabilities are in Healthy People 2010 and the Call to Action to Improve the Health and Wellness of Persons with Disabilities (see the Web Resources section of the  website).These initiatives promote the health and well-being of children and adults with disabilities and ensure that they have access to comprehensive healthcare, enabling them to live full and productive lives. Even though statutes, regulations, court decisions, and programs provide equal opportunity for persons with disabilities, they alone cannot ensure quality of life.

website).These initiatives promote the health and well-being of children and adults with disabilities and ensure that they have access to comprehensive healthcare, enabling them to live full and productive lives. Even though statutes, regulations, court decisions, and programs provide equal opportunity for persons with disabilities, they alone cannot ensure quality of life.

BARRIERS TO HEALTHCARE

Financial Barriers

Cost remains the primary barrier to healthcare services. Financial resources are needed to obtain an education, participate in rehabilitative programs, train for a job, find adequate housing, use basic transportation, and survive. State and federal funds fail to cover the costs of everyone’s needs, forcing many disabled people to prioritize their spending, often at the expense of basic needs. Most disabled people rely on state and federal support (e.g., Social Security payments) to cover daily expenses. Individuals who are able to work earn low wages, and unemployment rates remain relatively high.

Without adequate funds for daily expenses, healthcare is often neglected. Most cannot afford private healthcare insurance and rely on Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for financial assistance. For those on a limited income without health insurance, money for healthcare is an out-of-pocket expense; healthcare is often sought on a crisis basis, for emergencies or pain control. For disabled individuals with health insurance, oral healthcare may be denied as a medically unnecessary service.

For disabled individuals living in an institution, medical and limited dental services may be provided, but high fees are associated with these services, the cost of which is passed on to the family or state. If a severely disabled person needs to be institutionalized, costs to the family may drain their financial resources. Eligibility requirements for Medicare and Medicaid limit access of mainstreamed residents to oral care services that otherwise would have been provided in an institutional setting. Many families choose to care for a severely disabled individual at home because long-term care is too great a financial burden.

Architectural Barriers

The ADA mandates that all public facilities contain a barrier-free design. This law requires that all architectural and communication barriers be removed from public areas of existing facilities (e.g., in hotels, restaurants, theaters, museums, retail stores, schools, banks, and healthcare facilities, including dental offices and clinics) when their removal is readily achievable. In addition, people who own, lease, sublet, or operate places of public accommodation in existing buildings are responsible for ensuring that all barriers are removed. Often, removal of the barrier can be achieved by making simple physical changes to the facility. A facility that is barrier-free enables a person to function independently both within and outside of the home environment. For example, a building that contains elevators and accessible restrooms is not considered truly barrier-free if there are no ramps or electronically operated doors to gain entrance. Specific building codes and architectural standards for a barrier-free facility are available from federal and state resources (see the Web Resources section of the  website).

website).

Transportation Barriers

One frequently overlooked barrier is transportation. All too often, clients with disabilities have long distances to travel to a healthcare facility that is qualified and willing to treat them. Public transportation such as subways, buses, rail systems, and airplanes provide limited assistance to the disabled, despite federal regulations that require modifications for greater access. Interpreting the schedule, finding the exact fare, waiting at a boarding stop during inclement weather, boarding the right vehicle, and tracking the number of stops can be extremely difficult for someone with impairments. As a result, many disabled choose not to use mass transportation and would rather stay home than risk traveling.

Many stations and transportation vehicles also remain inaccessible, partly because the ratio of disabled persons to nondisabled persons is low and renovations are costly. When renovations are made, expenses are passed along to passengers, escalating transportation costs. Traveling expense then becomes an additional barrier to disabled people, who are usually on fixed incomes and unable to afford transportation services anyway. Reliance on others for transportation to and from the home may not be convenient for the disabled or for the driver. This places an added burden on family members or caregivers who accompany disabled persons.

Attitude of Healthcare Professionals

Healthcare practitioners pose a significant barrier to care. More disabled persons live outside of institutional settings; therefore more of them need to be treated within the private sector. A major complaint that disabled individuals have is finding practitioners willing to treat them. Some practitioners choose not to treat disabled individuals because Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements are often not equivalent to the fee schedules typically charged. In addition, extra time is often needed to treat these individuals, so that time for and income from treating others is lost. Fear of interacting with a disabled person and conflicting personal values about the disabled may make an individual avoid treating such a person. Advanced training and education on the healthcare needs of persons with disabilities is limited and lacks support from state and federal funding. As a result, many practitioners do not feel qualified to treat these individuals.

Many healthcare providers are unaware of the relationship between the mouth and the body (see Chapter 18) and fail to recognize oral diseases as infections that need immediate attention. Nurses and aides who work in institutions for the severely disabled may view oral care as a low priority and an unpleasant task and many times do not include this service in the client’s care plan.

Attitudes of Disabled Clients

Oral care holds significance as the lifeline for the disabled client. For example, the mouth is important for mastication, speaking, expressing personality, using telecommunication devices, working at a job, and portraying a positive self-image. However, many disabled individuals and/or their caregivers do not recognize the importance of maintaining good oral health. Often, medical treatment consumes the majority of their time and money; dental care becomes a low priority. Some disabled individuals, unaware of oral health, lack the motivation to keep the mouth disease-free. Others feel that dentists do not understand their impairment, which can lead to a negative dental experience. Dental hygienists must reach out to disabled individuals and establish a “dental home” for them.

PERSONAL SELF-WORTH

A healthy, functioning mouth implies that the individual values health and physical appearance. This positive portrayal of the mouth contributes to the client’s acceptance into society, self-worth, self-esteem, self-concept, and self-image. All people have achievements that build confidence and disappointments that lower confidence. The disabled client copes with life events with the same behaviors as the nondisabled individual; however, disabled people’s physical appearance may interfere with how others view them, which in turn affects how they view themselves.

Positioning of the disabled person may cause intimidation or self-consciousness in proximity to others. For example, people in wheelchairs are physically lower than those who do not use wheelchairs; hence, others look down on them while conversing. People who use assistive devices (canes, braces, or walkers) may be viewed as inept or unable to ambulate on their own. People who are hearing or visually impaired may have difficulty following a conversation and therefore may be excluded from the group. People with tremors or other muscular disorders may take a longer time to speak and may be viewed as mentally impaired by those unwilling to listen.

Disabled clients are individuals who have their own personal capabilities and limitations and adapt to life in much the same way as others. Therefore clients should be viewed as individuals who contribute to society despite their disabilities and who have needs similar to those of others.

DEFINING DISABILITIES

The term “disability” is associated with a limitation in a major life activity. Major life activities are those that the average person in the general population can perform with little or no difficulty (e.g., caring for oneself, walking, hearing, seeing, breathing, standing, speaking, sitting, learning, thinking, and interacting with others). This is an age-related measure that takes into consideration the activities that are normal for a given age group.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, participation restrictions, and environmental factors. Impairments occur as a result of pathology, accident, or disease and include any loss or abnormality—physiologic, anatomic, or mental—in function, which may or may not be permanent; for example, impairments can occur as a result of a stroke, which can cause sensory loss, aphasia, and paresis. Other examples of impairments include loss of a limb or body organ or a broken limb or hip. An activity limitation is difficulty in executing activities (e.g., having trouble with basic activities of daily living because of a health condition). A participation restriction is the inability to take part in conventional life situations for reasons that may be beyond the client’s control; for example, a working-age person with a severe health condition may find it difficult to work as a result of the workplace environment (e.g., lack of reasonable employer accommodations) and/or the social environment (e.g., discrimination). WHO’s definition includes the social aspects of disability and does not consider disability as only a medical or biologic abnormality. Including social factors further defines the impact that the environment has on the client’s ability to function in society.

Classification of Disabilities

Several methods are used to categorize individuals with disabilities. Government classification standards are based on criteria delineated in the ADA, that is, an individual with a disability is one who meets the following criteria:

These criteria are used to determine eligibility for federal assistance.

Disabilities (i.e., disabling conditions) also are categorized as follows:

Developmental disabilities occur congenitally or during the developmental period of the child, a period that lasts from birth to age 22 years. Developmental disabilities are generally chronic in nature; continue throughout the life of the person; and appear as mental, physical, or combined impairments. Individuals with developmental disabilities may experience difficulties with many functions and may be limited in their abilities to care for themselves, communicate effectively, learn new concepts, ambulate, or live independently.

Developmental disabilities occur congenitally or during the developmental period of the child, a period that lasts from birth to age 22 years. Developmental disabilities are generally chronic in nature; continue throughout the life of the person; and appear as mental, physical, or combined impairments. Individuals with developmental disabilities may experience difficulties with many functions and may be limited in their abilities to care for themselves, communicate effectively, learn new concepts, ambulate, or live independently. Acquired disabilities occur after the age of 22 years or are caused by a disease, trauma, or injury to the body. Common acquired disabilities include spinal cord paralysis from sports or motorcycle accidents, limb amputation because of disease, and limitations in range of motion from arthritis.

Acquired disabilities occur after the age of 22 years or are caused by a disease, trauma, or injury to the body. Common acquired disabilities include spinal cord paralysis from sports or motorcycle accidents, limb amputation because of disease, and limitations in range of motion from arthritis. Age-associated disabilities occur later in life, typically over the age of 65. As people reach a “ripe old age,” they are at higher risk for developing chronic disease, which in turn may result in disability. Chronic diseases include cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cognitive impairments, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and physical deterioration can also cause an elderly individual to become disabled.

Age-associated disabilities occur later in life, typically over the age of 65. As people reach a “ripe old age,” they are at higher risk for developing chronic disease, which in turn may result in disability. Chronic diseases include cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, osteoporosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cognitive impairments, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and physical deterioration can also cause an elderly individual to become disabled.Another classification groups disabilities into several major categories, clustering impairments with similar manifestations together (Table 41-2). These categories are useful when studying a group of disorders or when attempting to classify the condition of a client with oral pathology associated with a known disorder. This system mainly categorizes a person according to medical status and provides little information about how well an individual can compensate for limitations in daily function.

TABLE 41-2 Classifications of Disabilities

| Disability | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Developmental Disabilities | |

| Intellectual disabilities | Includes Down syndrome; reflects difficulties with learning, critical thinking, and skill development |

| Cerebral palsy | Nonprogressive disorder caused by brain damage either at birth or before the central nervous system (CNS) reaches maturity |

| Epilepsy | Cause by a chemical imbalance in the brain; associated with head injury, infection, and developmental disorders |

| Autism spectrum disorders | Lifelong neurologic disability with limitations in communication and social interactions |

| Sensory Impairments | |

| Visual impairments | Range from changes in visual acuity to blindness |

| Hearing impairments | Varying degrees of hearing loss to deafness |

| Orthopedic Disorders | |

| Paralysis | Most commonly associated with stroke |

| Spinal cord injury | Most commonly associated with accidents or injury |

| Missing extremities | Most commonly associated with injury or diabetes |

| Medical Disabilities | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | Hypertension, congestive heart disease, angina, valvular disease |

| Autoimmune diseases | Systemic lupus erythematosus, gout, Sjögren’s syndrome, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) | Infection that destroys white blood cells, resulting in breakdown of the immune system |

| Cancer | Oral and systemic cancer |

| Diabetes | Type 1 or type 2 |

| Respiratory disease | Tuberculosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Renal disease | End-stage renal disease |

| Blood disorders | Bleeding disorders, platelet disorders, sickle cell anemia, other anemias |

| Cognitive Impairments and Psychiatric Disorders | |

| Anorexia and bulimia | Eating disorders; characterized by self-starvation or massive food binges followed by self-induced vomiting or excessive use of diuretics |

| Mood disorders | Major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia |

| Dementia | Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Pick’s disease |

| Cerebrovascular accident (CVA, stroke) | Blockage of blood flow to the brain that can cause sudden partial or complete loss of function on one side of the body or death |

| Substance Use Disorder | Abuse of alcohol and/or psychoactive drugs |

| Degenerative Nervous System Disorders | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Neuronal degeneration in the cerebral cortex, resulting in loss of memory, critical thinking, and reasoning ability |

| Parkinson’s disease | Degeneration of deep cerebral nuclei, resulting in loss of control of voluntary movements; tremors, slowness of movement (bradykinesia); gradual onset of dementia |

| Huntington’s disease | Autosomal-dominant disorder that causes degeneration of the deep nuclei, cauda, and putamen; behavioral problems and constant muscle movement (chorea) |

| Cerebellar ataxias | Normal mental status; changes in gait and coordination |

| Motor neuron disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Cell death in the motor neurons of the spinal cord and cerebral cortex; progressive muscle atrophy leading to respiratory failure; no loss of mental or sensory functions |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | Muscle weakness characterized by cyclic nature of progression |

| Myasthenia gravis | Muscle weakness around the eyes and throat; difficulty in swallowing |

| Neurofibromatosis | Genetic autosomal dominant disease; multiple benign tumors |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | Mutation of prion protein gene; degeneration of neurons; neuronal loss, amyloid plaque formation and rapidly progressive dementia |

| Communication Disorders | |

| Dysarthria | Speech disorder from muscle weakness caused by damage to central or peripheral nervous system or both; slurred speech patterns |

| Apraxia | Speech disorder caused by a lesion within the CNS; impaired capacity to position muscles to form speech; stuttering |

| Aphasia | Language disorder caused by neurologic damage; inability to put thoughts into words or to comprehend words |

Functional status is perhaps the most useful method for categorizing disabilities because each disabled person has different abilities and limitations, regardless of medical diagnosis or degree of system involvement. Functional status describes how well the client can conduct basic and instrumental activities of daily living.

Basic activities of daily living (BADLs) include activities required for personal care such as feeding, dressing, grooming, bathing, and toileting.

Basic activities of daily living (BADLs) include activities required for personal care such as feeding, dressing, grooming, bathing, and toileting. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) encompass more complex tasks required for independent living (e.g., using a telephone, preparing meals, cleaning the house, driving a car, or using public transportation).

Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) encompass more complex tasks required for independent living (e.g., using a telephone, preparing meals, cleaning the house, driving a car, or using public transportation).Every individual values the ability to live independently. Functional independence enables individuals to participate in life situations that are meaningful and purposeful; participation in both basic and instrumental activities of daily living is essential to health and well-being. The dental hygienist who is able to improve the client’s functional abilities and oral health behaviors also increases the client’s functional status and quality of life.

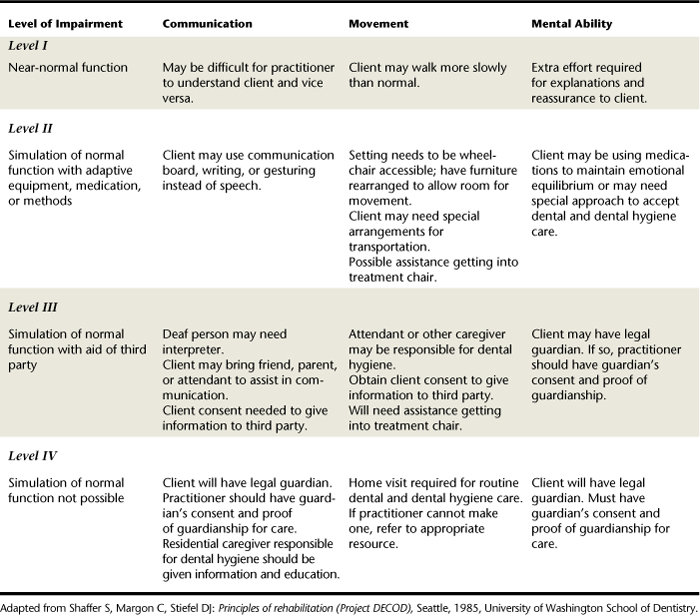

Impairments can affect five aspects of function: communication, movement, mental ability, medical health, and sensory perception. These aspects of function are limited; they do not address the degree of severity or extent of involvement of impairments, which may cause varying degrees of functional limitations. Table 41-3 illustrates how functional limitations are related to the severity of impairment according to four levels of involvement.

Interaction with People with Disabilities

Key points when describing or interacting with persons who have disabilities are as follows:

A person is not a disability; rather a person has an impairment. Therefore it is inappropriate to say, “She is my multiple sclerosis case.” It is more appropriate to say, “This is my client, Mrs. Jones. She has multiple sclerosis.”

A person is not a disability; rather a person has an impairment. Therefore it is inappropriate to say, “She is my multiple sclerosis case.” It is more appropriate to say, “This is my client, Mrs. Jones. She has multiple sclerosis.” An impairment does not override other client characteristics; therefore the impairment should be addressed only when necessary or relevant to the situation. Emphasizing the impairment without reason should be avoided.

An impairment does not override other client characteristics; therefore the impairment should be addressed only when necessary or relevant to the situation. Emphasizing the impairment without reason should be avoided. Clients with disabilities are not superhuman; learning to function as a person despite the impairment is survival, not a unique act that requires special talents. Sensationalizing goal attainment by impaired people is a common reaction, such as by saying “He triumphed over his inability to walk,” implying that the client was a victim of the impairment.

Clients with disabilities are not superhuman; learning to function as a person despite the impairment is survival, not a unique act that requires special talents. Sensationalizing goal attainment by impaired people is a common reaction, such as by saying “He triumphed over his inability to walk,” implying that the client was a victim of the impairment. Sensationalizing terms that draw on emotions, such as “relies on a cane” or “bound to a wheelchair,” are inappropriate and imply a false level of dependency on the part of the client.

Sensationalizing terms that draw on emotions, such as “relies on a cane” or “bound to a wheelchair,” are inappropriate and imply a false level of dependency on the part of the client. People with disabilities are not necessarily sick, regardless of whether the impairment was caused by an illness. It is inappropriate to describe an impaired client as a “patient” or a “case” unless that person is actively under medical care.

People with disabilities are not necessarily sick, regardless of whether the impairment was caused by an illness. It is inappropriate to describe an impaired client as a “patient” or a “case” unless that person is actively under medical care.Negative portrayal issues are encountered through personal contact or the mass media. For example, people may express pity for a disabled person without knowing the individual, or disbelief when seeing a disabled person enjoying himself “despite his impairment.” Healthcare professionals who work with disabled clients are often viewed as having special motivation or as “truly patient.” Television portrayals often treat the disabled adult like a child or an inferior. A disabled adult may be addressed by first name or with a surname when the situation dictates a more formal title. Other examples include speaking for the disabled person as if he or she were not there and assuming that the individual cannot make decisions independently. Negative portrayals should be avoided for a positive therapeutic relationship.

ASSISTIVE DEVICES

Many clients have complex oral needs associated directly with their conditions or with medications taken to stabilize or control the symptoms of their conditions. Clients may require special assistance in accomplishing self-care behaviors necessary for oral health and awareness.

The client’s impairment may dictate the need for assistive devices, tools used to achieve independence in daily functions and communication. Many devices are available through area pharmacies and agencies; others are specifically tailored for the client. Dental hygienists must be familiar with these devices because their use may affect client goals and decisions in care.

Walking Devices

Various devices are available for the client who has difficulty with ambulation. Canes, leg braces, crutches, and walkers are all devices that assist the client by bearing the weight of the body during motion (Figure 41-1). These devices replace function either unilaterally or bilaterally, greatly increase mobility, increase mobility for ambulation, and support the individual while he or she moves from bed to chair. The walking device should remain close to the client. For example, if the dental hygienist moves the device, the client must be informed of its location to avoid feeling trapped. The dental hygienist retrieves the device when needed or at the client’s request, and hands the device directly to the client for use. Anxious clients may prefer to hold the device as a measure of security. Although not ideal, this behavior may be tolerable as long as the device does not interfere with care.

Figure 41-1 Walking devices. A, Use of walker greatly increases client’s mobility. B, Crutches assist client by bearing the weight of the body during motion. C, Canes assist the client with balance and decrease weight bearing on the leg opposite the side on which the cane is held.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center; and Bobi Robles, Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation, Dallas, Texas.)

Wheelchairs are devices that assist clients who have limited or no mobility in the legs for ambulation. Wheelchairs increase mobility for those who may otherwise be confined to bed or chair. Because of improvements in building design, many facilities are completely accessible to wheelchairs, thus enabling clients to move freely without being inhibited by physical limitations in ambulation. Clients may be treated in the wheelchair or transferred to the dental chair for care (see section and procedures on wheelchair transfer techniques in this chapter). Most clients prefer to operate the wheelchair themselves; assistance should be provided only at their request.

Prosthetic Devices

Prosthetic devices enhance client appearance and improve function. Fitted after amputation, prosthetic legs improve ambulation, prosthetic arms increase reach and range of motion, and prosthetic hands improve grasp. Other devices may replace structures or organs because of congenital anomalies or that were removed because of pathology or trauma. Prosthetic devices may be permanently fitted through surgical implantation or may be removable and worn only when needed for functional or cosmetic purposes. Clients with removable devices such as those designed for loss of facial structure may feel more comfortable when the prosthesis is in place; therefore removal should occur only during assessment or when indicated during care. All devices should be replaced immediately after completion of the procedure to ensure client comfort and ease. Privacy must be maintained when the prosthetic device is removed, preferably in a closed area or examination room. Prophylactic antibiotic premedication may be indicated before dental hygiene care for the client who is within 2 years of a prosthetic joint replacement.

Assistive Listening Devices

Assistive listening devices for clients with hearing deficits detect sounds and assist with understanding speech. Hearing aids amplify sounds and are effective only when some hearing capacity exists. Hearing aids may be worn in the outer ear to improve sound conduction (e.g., conventional hearing aids) or surgically implanted under the skin or in the bone behind the ear for inner ear conduction (e.g., cochlear implants or bone anchor hearing aids). Because many people deny hearing loss, some may own a hearing aid but choose not to wear the device out of self-consciousness or embarrassment. These clients may appear unresponsive to questions or conversation. Such behaviors should alert the dental hygienist to possible hearing impairment, and the client should be asked about the use of a hearing device.

The oral environment can create annoyances for persons with hearing aids. Close operator proximity or incorrect placement of the hearing aid may cause it to squeal; high-pitched noises from dental handpieces or ultrasonic devices initiate this reaction. The client should be instructed to turn off or remove the hearing aid during dental care. Clients adapting to a new hearing aid often turn down the aid because “everything seems so noisy.” Because all sounds are amplified, these clients may become aware of sounds they never heard before or have not heard in a long time, especially if the hearing loss was gradual and untreated. Most environments contain background noise, and clients may turn off the hearing aid before coming for their appointment.

Other assistive listening devices are available. Amplifiers can be used on telephones, televisions, and radios to increase sound volume for those with partial hearing loss. Closed captioned television programs assist the hearing-impaired client with lip reading. Telecommunication devices for telephones reproduce sounds from a caller and convert them into written type that can be read from a monitor. A typed response transmits a message back to the caller.

Aids for the Visually Impaired

Clients who are visually impaired usually wear corrective lenses to improve vision and augment communication. If oral care instructions are given to a client who has forgotten his or her glasses, written material can be provided to read after the appointment. These materials should contain large print with adequate contrast. Clients who are blind frequently wear dark glasses to protect the eyes from light sensitivity. Blind clients require guidance, especially in an unfamiliar environment, and depend on tactile stimulation to understand the environment, as follows:

To accompany client to the treatment area, the client’s nondominant hand should be placed under the elbow of the hygienist, and the client should be asked to stand next to but slightly behind the hygienist.

To accompany client to the treatment area, the client’s nondominant hand should be placed under the elbow of the hygienist, and the client should be asked to stand next to but slightly behind the hygienist. Specific directions guide the client (e.g., “Take three steps forward, and then turn right. We’re going to step down onto a smooth floor. There is only one step.”)

Specific directions guide the client (e.g., “Take three steps forward, and then turn right. We’re going to step down onto a smooth floor. There is only one step.”) When arriving in the treatment area, the client should be told the location of objects in the room (e.g., “The chair is directly in front of you, about one foot away from where you are standing now.”) Allow client to feel the location and direction of the chair by placing the client’s hands onto the chair while giving verbal instructions. Remaining close with a hand resting on the client’s shoulder conveys comfort and concern while the client is getting settled into the chair.

When arriving in the treatment area, the client should be told the location of objects in the room (e.g., “The chair is directly in front of you, about one foot away from where you are standing now.”) Allow client to feel the location and direction of the chair by placing the client’s hands onto the chair while giving verbal instructions. Remaining close with a hand resting on the client’s shoulder conveys comfort and concern while the client is getting settled into the chair.Blind clients may use a cane or a guide dog during ambulation and prefer to use these aids to assistance by another individual. Guide dogs are permitted to remain in the treatment area and should be directed by the client to sit close and within clear view of the client. Do not attempt to pet the guide dog, as such dogs may feel threatened and may attack anyone who approaches them. In addition, guide dogs should never be left alone in another area; they may become anxious in the absence of their owners.

Assistive Speaking Devices

Assistive speaking devices recreate sounds that mimic normal speech patterns for persons who have had surgical removal of the larynx and cannot make sounds from the throat. Electronic speech devices held against the throat detect vibrations of air passing through the throat as the person mimics normal speech. The device reproduces a noise that resembles an automated, robotlike speech. Use of this device enhances verbal communication. Speech therapists train clients with laryngectomies to expel air from the esophagus for sound formation to produce altered speech.

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is a method of communication used by clients with severe speech and language impairment (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, aphasia, apraxia, traumatic brain injury, cerebral palsy). AAC is used for clients who are unable to use verbal speech yet are cognitively able, or when speech is extremely difficult to understand. The client will use, alone or in combination, gestures, communication boards, pictures, symbols, or drawings. For example, if the client is hungry, he or she will point to the picture on the ACC of someone eating. Clients who use an electronic communication board have it programmed by a speech language pathologist based on their functioning level (Figure 41-2).

Figure 41-2 Augmentative and alternative communication device used for clients with severe speech and language impairment.

(Courtesy DynaVox Technologies, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.)

When treating this type of client, the dental hygienist must listen carefully and repeat the message given by the client to ensure accuracy in understanding. It is also important to allow enough response time when communicating with a client who uses AAC. With practice, it becomes relatively easy to understand and communicate with these clients.

Assistive Devices for Paralyzed Persons

Elimination Devices

Clients paralyzed below the waist experience difficulty with normal waste elimination and may use a catheter for assistance with urination. Care must be taken when moving a client with a catheter so that it does not become kinked or dislodged. Also, clients may have a bowel and bladder routine to regulate waste elimination. Clients should be questioned regarding their elimination schedules and instructed to complete their bowel and bladder routine before appointments.

Communication Devices

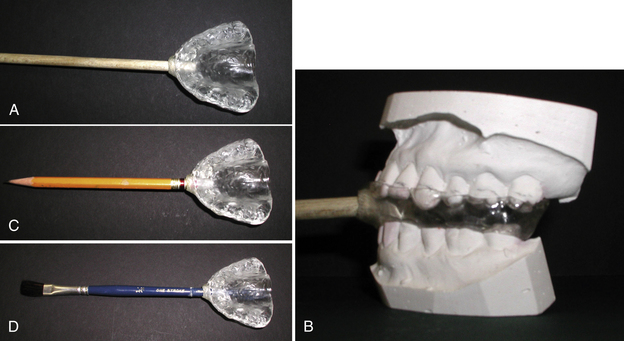

Clients paralyzed below the neck use a variety of devices to accomplish BADLs, most of which are designed by occupational or speech therapists. The mouth is needed to operate many of these devices, which alters the health and function of oral structures. The most common device used by tetraplegic clients is the mouth stick, a simple plastic or balsa wood rod with a rubber tip held in place by the teeth and lips (Figure 41-3).

Figure 41-3 Mouth stick. A, Custom-fabricated mouth stick for persons with tetraplegia. B, Mouth stick is fabricated so that the biting forces are equally distributed across the maxillary arch. C and D, Hole on anterior surface of mouth guard can also hold a pencil or a paintbrush.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Dallas, Texas.)

Mouth sticks can be used for communication, such as typing on a keyboard or pressing the buttons on a telephone. Mouth sticks also are used to turn book pages, operate a computer, and use appliances such as microwave ovens and remote-controlled televisions.

Teeth may be subjected to occlusal trauma from the mouth stick, which, in the presence of inflammation and risk factors, may result in rapid periodontal destruction and tooth loss. A biologically sound dentition and skin and mucous membrane integrity are of great significance to these clients. Without healthy teeth and supporting structures, they may not be able to hold the stick and therefore lose the ability to communicate and function independently.

Mouth sticks may contribute to muscle fatigue, oral tissue trauma from inserting the stick, difficulty with insertion without the assistance of a caregiver, unpleasant taste, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) discomfort, and gagging. Considerations in the fabrication of mouth stick appliances are listed in Box 41-1.

Fabrication of a mouth stick begins with an alginate impression of the client’s maxillary and mandibular arch. Stone dental casts are made and can be used to create the two types of mouth sticks that are currently available:

Mouth stick with an acrylic mouth guard. The mouth guard is designed over the mandibular stone cast, then adjusted in the client’s mouth for fit and occlusal stability. A hole is made in the appliance and adapted for the mouth stick. The occupational or speech therapist assists the prosthodontist with final evaluation of the length and design of the stick based on client needs.

Mouth stick with an acrylic mouth guard. The mouth guard is designed over the mandibular stone cast, then adjusted in the client’s mouth for fit and occlusal stability. A hole is made in the appliance and adapted for the mouth stick. The occupational or speech therapist assists the prosthodontist with final evaluation of the length and design of the stick based on client needs. Mouth stick with moving parts between the maxillary and mandibular arches. This device is used by persons who cannot move the head or neck. It contains a telescoping mouth stick that is held in a ball-and socket joint at the anterior portion of the appliance and a rack-and-pinion device that is incorporated into the joint. Muscles of mastication are used to produce vertical movements of the mouth stick; the tongue controls lateral movement and the telescoping function.

Mouth stick with moving parts between the maxillary and mandibular arches. This device is used by persons who cannot move the head or neck. It contains a telescoping mouth stick that is held in a ball-and socket joint at the anterior portion of the appliance and a rack-and-pinion device that is incorporated into the joint. Muscles of mastication are used to produce vertical movements of the mouth stick; the tongue controls lateral movement and the telescoping function.Before insertion of either appliance, oral inflammation should be eliminated. Careful monitoring of the fit and use of the appliance minimizes periodontal trauma and ensures optimal benefit for the client.

Assistive Devices for Protection of Oral Function

Assistive devices for protection and oral function (i.e., custom mouth protectors) are used to prevent self-inflicted trauma by clients with behavioral problems or who are comatose. The custom mouth protector does the following:

The devices should be used only in consultation with a behavioral specialist.

Clients with neuromuscular disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and/or stroke or clients who have had surgery in which a portion of the throat or palate has been removed may experience difficulty in speaking and swallowing and require a device to assist with oral function. Palatal lifts, palatal augmentation devices, and obturators are all devices that improve function by recreating normal physiologic movement of the oral tissues. The dental hygienist caring for the client with this type of device must monitor changes in speaking patterns, swallowing ability, and device cleanliness. If adjustment of the device is needed, the client should be referred to a prosthodontist.

ORAL SELF-CARE DEVICES

Although many devices facilitate BADLs, few existing devices help the client carry out oral self-care behaviors independently. Creative alternatives to traditional oral hygiene devices are designed for those with limitations in function. These devices should adapt to the client’s needs, skill level, and functional status.

Client Assessment

The dental hygienist assesses the client’s physical and mental limitations that affect how the client adapts to using a device.

Range of motion. The client’s ability to reach the oral cavity with the arms and hands is determined. Extent of range of motion dictates the length of the device required to accommodate physical limitations in reaching the mouth. For example, a client with a muscular impairment may be able to reach halfway across his or her body yet elevate the arm only to heart level. This client needs an extended length to compensate for the limited motion of reaching above heart level. Similarly, the client who is unable to bend at the elbows or wrists may have difficulty reaching certain areas of the oral cavity and may need an angled device for improved reach to fit in all areas of the mouth.

Range of motion. The client’s ability to reach the oral cavity with the arms and hands is determined. Extent of range of motion dictates the length of the device required to accommodate physical limitations in reaching the mouth. For example, a client with a muscular impairment may be able to reach halfway across his or her body yet elevate the arm only to heart level. This client needs an extended length to compensate for the limited motion of reaching above heart level. Similarly, the client who is unable to bend at the elbows or wrists may have difficulty reaching certain areas of the oral cavity and may need an angled device for improved reach to fit in all areas of the mouth. Grip strength. Clients with arthritis or neuromuscular disorders experience difficulty holding a device that is too narrow or too small (Figure 41-4). To assess grip strength, have the client grasp various sizes of foam cylinders. These are more functional than having the client grip tennis balls or softballs. Another measure of grip strength includes assessing the client’s ability to retain finger closure for an extended length of time. The hygienist should grasp the client’s hand gently and ask the client to squeeze with as much force as possible and hold this position for 1 minute. This assessment determines the strength needed to hold the device for a given length of time. If the client is unable to keep the fingers closed for 1 minute, a universal cuff, such as a Palmar Velcro strap, may be needed for holding the device.

Grip strength. Clients with arthritis or neuromuscular disorders experience difficulty holding a device that is too narrow or too small (Figure 41-4). To assess grip strength, have the client grasp various sizes of foam cylinders. These are more functional than having the client grip tennis balls or softballs. Another measure of grip strength includes assessing the client’s ability to retain finger closure for an extended length of time. The hygienist should grasp the client’s hand gently and ask the client to squeeze with as much force as possible and hold this position for 1 minute. This assessment determines the strength needed to hold the device for a given length of time. If the client is unable to keep the fingers closed for 1 minute, a universal cuff, such as a Palmar Velcro strap, may be needed for holding the device. Skill level. Watching the client simulate the motion used to brush the teeth, or watching the client actually brush the teeth with his or her current technique, is used to assess skill level. The client should be prompted to perform skills such as reaching into the upper right quadrant, brushing the tongue, cleaning the lingual surfaces, and brushing the facial surfaces of anterior teeth. It is important to note what the client is capable of performing with relative ease and which behaviors present difficulty or confusion.

Skill level. Watching the client simulate the motion used to brush the teeth, or watching the client actually brush the teeth with his or her current technique, is used to assess skill level. The client should be prompted to perform skills such as reaching into the upper right quadrant, brushing the tongue, cleaning the lingual surfaces, and brushing the facial surfaces of anterior teeth. It is important to note what the client is capable of performing with relative ease and which behaviors present difficulty or confusion. Ability to understand and follow directions. This ability is evaluated during the grip strength assessment. The hygienist asks a sufficient number of questions to determine whether the client is capable of responding accurately to verbal commands and instructions. For example, the client who is cognitively impaired may have difficulty in producing a response on command and may require a device such as a power toothbrush that accomplishes the task with little effort.

Ability to understand and follow directions. This ability is evaluated during the grip strength assessment. The hygienist asks a sufficient number of questions to determine whether the client is capable of responding accurately to verbal commands and instructions. For example, the client who is cognitively impaired may have difficulty in producing a response on command and may require a device such as a power toothbrush that accomplishes the task with little effort. Perception about what seems easy or difficult. Direct client feedback is essential for a complete assessment, in that the client’s perceptions may influence compliance with any device, whether well adapted for his or her needs or not. The client should understand his or her role in the use of the device—a motivational strategy that promotes ownership of the responsibility for oral self-care behaviors.

Perception about what seems easy or difficult. Direct client feedback is essential for a complete assessment, in that the client’s perceptions may influence compliance with any device, whether well adapted for his or her needs or not. The client should understand his or her role in the use of the device—a motivational strategy that promotes ownership of the responsibility for oral self-care behaviors. Current oral status and oral self-care techniques, the range of opening of the mouth, and the activity of the oral musculature, especially the tongue. Intraoral assessment provides information about existing oral conditions that may dictate the need for certain device design characteristics. Widening of the oral cavity can be accomplished through the use of cones or tongue depressors (adding one on top each day to extend the opening of the mouth).

Current oral status and oral self-care techniques, the range of opening of the mouth, and the activity of the oral musculature, especially the tongue. Intraoral assessment provides information about existing oral conditions that may dictate the need for certain device design characteristics. Widening of the oral cavity can be accomplished through the use of cones or tongue depressors (adding one on top each day to extend the opening of the mouth).

Figure 41-4 Persons with arthritis may have difficulty holding an oral self-care aid such as a toothbrush or interdental cleaner. A modified oral self-care aid or power toothbrush or interdental cleaner is indicated. Right hand of client has been surgically repaired to allow more range of motion. At time of photo, left hand had not been treated.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Dallas, Texas.)

A comatose or semicomatose person in a hospital or extended care facility may benefit from toothbrushes such as the Plak-Vac Oral Suction Brush (Trademark Medical Corporation), which is a specially designed toothbrush that can be connected to a bedside suction device (Figure 41-5).

Figure 41-5 Plak-Vac Oral Suction Brush being connected to the bedside suction device in a critical care unit.

(Courtesy Michelle Bopp, Gene W. Hirschfield School of Dental Hygiene, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia.)

These assessment measures work well with clients who are mentally and physically capable of learning self-care techniques; however, some clients may not move their upper extremities at all and therefore rely on a primary caregiver to perform daily care. Caregiver interviews are important to assess willingness to provide daily oral care, determine the existing skill level of the caregiver, and identify concerns.

Customizing Oral Self-Care Devices

For clients with a limited range of motion, adaptations to oral self-care aids may be needed. Plastic rulers and rods, available from most hardware stores, can be attached to toothbrushes and floss holders with heavy electrical tape. The added length of the handle facilitates reach but may make placement of the working end of the self-care device in the mouth difficult. To compensate, a toothbrush with a compact head size may be used for better intraoral fit. The existing plastic handle of the toothbrush can be bent to angulate the brush bristles against the curve of the arches. To bend the handle of a toothbrush, gently heat the handle above a flame or simply hold the handle under very hot tap water until pliable.

To assist the client with weak grip strength, the handle of the device can be built up with a variety of materials to fit the client’s finger closure capability. For the client with limited finger closure, a wide bulky handle is needed to assist with grip. Bicycle grips, Styrofoam molds, and arts-and-crafts compounds as alternative handles greatly improve the client’s ability to hold the device (Figure 41-6). Toothbrushes and floss holders can be inserted into these items and changed when necessary. Clients who have difficulties with coordination may find that a lightweight handle is hard to manage and that a weighted end may be easier to find and hold. Plastic bicycle grips are preferred because they are available in a variety of sizes, textures, and weights, are inexpensive, and are easily cleaned after use.

Figure 41-6 Customized oral care aids for persons with physical disabilities.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Dallas, Texas.)

The occupational therapist or dental hygienist is responsible for making these devices initially, but the caregiver should be trained to construct them thereafter. Custom-made devices should be brought to every appointment to assess design, usage, and need for replacement.

Clients with poor dexterity and coordination, and/or limited gripping ability, benefit from power toothbrushes with large handles that are easily used on the client by a caregiver.

Several manufacturers market manual toothbrushes that can be bent by hand without heating to promote better angulation and mouth access. Floss holders and toothbrushes with wide handles or with specific handle designs all promote improved grasping ability by the client. Other manufacturers of manual toothbrushes have reconfigured the head of the brush—for example, with brush bristles that surround the tooth, enabling the client and/or caregiver to brush the entire tooth surface at one time (Figure 41-7). Toothpaste containers with alternative dispensers, such as flip-top lids and levers, should be recommended to clients with limited finger motion because grip strength is needed to dispense the toothpaste. Oral irrigation devices are excellent supplemental aids for self-care and local delivery of antimicrobial agents.

Figure 41-7 The Surround Toothbrush is designed to clean lingual, facial, and occlusal surfaces at the same time.

(Courtesy Specialized Care Co, Hampton, New Hampshire.)

For clients who are unable to hold devices on their own, a universal cuff may be used for assistance. The strap, with Velcro adhesive on which various adaptive devices can be attached, fits around the arm or wrist and acts as a splint for stabilization. Universal cuffs may be adapted for use with oral physiotherapy aids. The dental hygienist should consult with an occupational therapist when treating a client who might benefit from a universal cuff for self-care devices.

Several design characteristics of the device include the following:

Made of a lightweight, readily available, inexpensive material and easily constructed; plastics are preferred because they resist water damage and can be easily cleaned, rinsed, and dried.

Made of a lightweight, readily available, inexpensive material and easily constructed; plastics are preferred because they resist water damage and can be easily cleaned, rinsed, and dried.CLIENT POSITIONING AND STABILIZATION

Physically challenged clients frequently have problems with support and balance; therefore a physical assessment before care determines whether adaptations are needed to treat the client safely. A list of client stabilization and supportive devices can be found online at the Special Care Dentistry Association website (www.scdaonline.org). Click on the link to Publications and Resources and scroll down to SCDA Product Guide.

Clients with neuromuscular problems, such as tremors, muscle spasms, or hyperflexive responses, may require a stabilization device, such as a seatbelt, to help remain in an upright and secure position. Other medical immobilization devices, such as papoose boards (Figure 41-8), are available to use with clients who have extreme spasticity or severe behavioral problems. Routine use of immobilization should be limited because it can promote distrust in the client and may decrease the possibility of future cooperation. In addition, physical restraints have been associated with bruising, respiratory compromise, aspiration pneumonia, and cellulitis from limb restraint. Immobilization or support devices should also be used with caution with a seizure prone-client because these devices must be removed quickly in the event of a seizure. However, in certain individuals in whom cooperation is near impossible, it may be necessary to use these devices at every visit in order to render care. The risks and benefits of using any form of immobilization must be explained to the client, parent, and/or caregiver, and informed consent must be obtained. Pillows or rolled towels may also be placed underneath the knees and the neck of the client to prevent muscle spasms and to provide additional support during care.

Figure 41-8 Physical restraint used to maintain the disabled client in a stable, safe position.

(Courtesy Specialized Care Co, Hampton, New Hampshire.)

To prevent injuries during care, a dental assistant or caregiver may hold the client’s arms and legs in a comfortable position. A dental assistant can easily rest his or her arm closest to the client across the client’s chest, with the client’s arms tucked underneath. With this technique, the client’s arms are prevented from moving into the working area in the event of a muscular reflex. In the case of a child who is difficult to keep still in the dental chair, the child may lie on top of the parent, with the parent’s arms around the child’s body. This practice should be discontinued early in the course of care after behavioral management techniques and trust exercises have been conducted with the child (Table 41-4). If a client is uncooperative and resists sitting in a chair, parents and caregivers can have the client lie on the floor with the client’s head in the caregiver’s lap, so that improved access into the mouth is obtained. Clients who are extremely combative and unable to remain still may need sedation.

TABLE 41-4 Behavioral Management Techniques

| Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Explanation and exposure (desensitization) | Graduated exposure to the oral healthcare setting instills familiarity with the environment. |

| Familiarization visit | Introducing client to the oral healthcare environment before initiation of care reduces fear and stress. |

| Demonstration (tell-show-do) and modeling | |

| Feedback | Immediate feedback improves client learning and skill development through evaluation of progress and performance. |

| Negative consequences (punishment) | Negative feedback decreases likelihood of repeating an undesired behavior; most effective as an early intervention strategy in cases of undesired behavior. |

| Positive consequences (reward) | Rewards strengthen behavior and encourage the repetition of a behavior; rewards include praise, special privileges, token systems, and material goods. |

| Distraction | Audiovisual stimuli, e.g., listening to music through headphones or watching a videotape, decrease uncooperative behavior by providing stimuli on which client can focus during care. |

| Communication | Words and phrasing that reflect empathy, respect, and warmth enhance client-provider interaction and trust. |

| Hand signals | Allow fearful client to raise a hand as a sign to stop treatment; promotes the client’s feelings of safety and security. |

| Touch | Reassuring touch displays warmth and understanding toward anxious client. |

| Relaxation, hypnosis, sedation | Counseling or drugs may be needed for clients with extreme anxiety, fear, or uncooperative behavior. |

The dental hygienist may find the need for additional head support and stabilization for the client during care. Sitting at the 12-o’clock position, the dental hygienist should wrap her or his nondominant arm around the client’s head and firmly under the chin for stabilization. Small pillows, neck rolls, or a rolled bath sheet also may be placed on either side of the client’s head for additional support. Beanbag chairs placed in the dental chair can provide additional support for physically challenged children with unstable joints and limbs (Figure 41-9).

Figure 41-9 Beanbag chairs help support limbs of physically challenged children during dental treatment.

Headrests, solid backrests, seatbelts, chest straps, lateral trunk supports, and hip guides are commonly used on wheelchairs to help keep the client positioned correctly in the chair. Cushions are helpful with paralyzed clients to provide additional support and to minimize the occurrence of pressure sores (decubitus ulcers or decubiti).

To reduce risk of aspiration, caregivers must not apply dentifrice or topical agents when the client is supine. The client with a neuromuscular or behavioral problem may use ingestible toothpaste as a safe alternative.

During care the practitioner should place the client in a sitting or semi-inclined position to prevent aspiration of materials, fluids, or instruments. Rubber dam isolation also prevents aspiration of dental materials; however, routine use is not recommended for impaired clients, especially those who have a compromised airway, are aggressive or uncooperative, or have swallowing difficulties. During dental treatment, it is essential to use good evacuation with the aid of a dental assistant, especially when increased salivation is present.

To prevent closure of the mandible onto the operator’s fingers, use of a mouth prop is recommended for treating impaired clients who are seizure prone, have muscle weakness, or experience muscle spasms. Standard mouth props should have one end of the dental floss tied through the hole at the base of the mouth prop and the other end attached to the client’s napkin clip. This allows the mouth prop to be pulled quickly from the mouth and prevents swallowing in the event of an emergency. Larger hand-held mouth props can also be used during assisted oral self-care (Figure 41-10).

Figure 41-10 Clinician using the Open Wide disposable mouth prop on an adult.

(Courtesy Specialized Care Co, Hampton, New Hampshire.)

The client is usually the best source of advice on how to approach positioning and movement. Ideally, all clients should be treated in the dental chair, but on occasion a client in a wheelchair may be too weak to transfer into the dental chair or may require positioning needs that only the wheelchair can provide. Some power wheelchairs have seat functions that will recline or tilt the client for adequate positioning, and this may be more comfortable for the client. The client may be treated in the wheelchair if the treatment area is wide enough for positioning the client either alongside or behind the dental chair. Clients who remain in the wheelchair need additional head support during care, which can be obtained by using a portable headrest or by turning the wheelchair around so that the client’s head is leaning against the back of the dental chair’s headrest (Figure 41-11). Treating multiple clients from this position may cause musculoskeletal problems; therefore clients who cannot be transferred should be treated early in the day while the hygienist is well rested. After providing care from a compromised operator position, the hygienist should break for adequate rest and muscle stretching before treating another client (see Chapter 9).

Figure 41-11 Wheelchair positioned so that the head is leaning against the back of the dental chair’s headrest.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Dallas, Texas.)

Figure 41-12 Transfer belt is placed around the client’s waist and below the ribcage.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center; and Bobi Robles, Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation, Dallas, Texas.)

Figure 41-13 One end of the sliding board is placed underneath the client, and the other end is laid across the dental chair.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center; and Bobi Robles, Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation, Dallas, Texas.)

Figure 41-14 Client’s hands are placed on side of wheelchair, and head is positioned on the operator’s shoulder opposite the direction of the transfer.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center; and Bobi Robles, Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation, Dallas, Texas.)

Figure 41-15 Client is lifted off the wheelchair and positioned for transfer to the dental chair.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center; and Bobi Robles, Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation, Dallas, Texas.)

Figure 41-16 During the two-person transfer, the first operator stands behind the wheelchair and the second operator positions herself at the client’s thighs.

(Courtesy Kathleen Muzzin, Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University Health Science Center; and Bobi Robles, Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation, Dallas, Texas.)

WHEELCHAIR TRANSFER TECHNIQUES

Transferring from Wheelchair to Dental Chair

Procedure 41-1 describes transferring the client from the wheelchair to the dental chair using a one-person lift. Before making the transfer, however, the health history must be assessed carefully to determine the client’s current health status, nature of the condition that dictates wheelchair use, existing physical strength, risk of inducing muscle spasms, and areas of the body that could be injured if the client is moved incorrectly. In addition, the client should be questioned regarding use of urinary appliances (catheters and collecting bags) that may become dislodged during a transfer. A kinked catheter results in inadequate drainage of the bladder, causing an accumulation of toxic waste, and could trigger an emergency situation. The client must be asked about use of waste elimination appliances so that proper care can be taken during the transfer. The client’s physician should be consulted about specific medical concerns identified on the health history assessment before any transfer is attempted.

Procedure 41-1 TRANSFERRING CLIENT FROM WHEELCHAIR TO DENTAL CHAIR USING A ONE-PERSON LIFT

STEPS

The client’s physical ability to participate with the transfer is assessed. Many clients who have undergone physical therapy for their condition may be accustomed to transfer techniques, especially if they have been taught to transfer at home by themselves. Some clients have the ability to assist with the transfer, although they may be unfamiliar with the actual procedural steps involved. Others may perceive that they have the physical strength and skills needed to assist with the transfer when actually they do not possess these abilities. Misconceptions may be dangerous if the transfer is attempted without verifying whether the client’s perceptions and abilities are realistic. Also, the client’s willingness to transfer is essential for the dental hygienist to know; it is important to remember that during any transfer procedure there is a level of dependency on the practitioner by the client, especially during lifting from the wheelchair. An uncooperative client who overestimates or underestimates his or her abilities or a client who resists transfer attempts poses significant management challenges, as well as increased risks for injury to both the client and dental hygienist.

The client’s level of coordination and balance determines need for assistance with the transfer process. Assistance may be required from another operator (Procedure 41-2) or may be obtained with the use of a transfer belt or sliding board.

Transfer belts are straps secured around the client’s waist to provide a place to hold the client in the event that the person begins to fall during the transfer process. These are especially useful with clients who have little to no upper body strength, such as tetraplegics.

Transfer belts are straps secured around the client’s waist to provide a place to hold the client in the event that the person begins to fall during the transfer process. These are especially useful with clients who have little to no upper body strength, such as tetraplegics. Sliding boards are used to assist the client with fair to good upper body strength by helping the client slide out of the wheelchair, across the board, and into the dental chair. The wheelchair must be positioned beside the dental chair, and the arms to both chairs must be removed to accommodate the board. One end of the board is placed underneath the client, and the other end is laid across the dental chair. The client uses upper arm and body strength to move across the board while the board provides support from underneath the client’s legs. Sliding boards also are useful with clients who are overweight or are otherwise too difficult for one person to safely move alone. Transfer belts may be used as an added precaution during a sliding board transfer.

Sliding boards are used to assist the client with fair to good upper body strength by helping the client slide out of the wheelchair, across the board, and into the dental chair. The wheelchair must be positioned beside the dental chair, and the arms to both chairs must be removed to accommodate the board. One end of the board is placed underneath the client, and the other end is laid across the dental chair. The client uses upper arm and body strength to move across the board while the board provides support from underneath the client’s legs. Sliding boards also are useful with clients who are overweight or are otherwise too difficult for one person to safely move alone. Transfer belts may be used as an added precaution during a sliding board transfer.Procedure 41-2 TRANSFERRING CLIENT FROM WHEELCHAIR TO DENTAL CHAIR USING A TWO-PERSON LIFT

STEPS

Operator safety must also be ensured as follows:

The operator should never attempt to transfer a client alone. Although the one-person transfer technique requires only one individual to maneuver the client, an additional person must be available to provide assistance if needed. The additional person reduces the risk of falling or injury to the client during a transfer.

The operator should never attempt to transfer a client alone. Although the one-person transfer technique requires only one individual to maneuver the client, an additional person must be available to provide assistance if needed. The additional person reduces the risk of falling or injury to the client during a transfer. One operator should never attempt to transfer a client who is very tall or heavy, especially clients who have no upper body strength. These clients have a much greater chance of falling because of their lack of coordination and balance, and they may injure themselves and the operator.

One operator should never attempt to transfer a client who is very tall or heavy, especially clients who have no upper body strength. These clients have a much greater chance of falling because of their lack of coordination and balance, and they may injure themselves and the operator. All transfer movements performed by the operator should be done with feet separated for good balance and knees bent to protect against back strain.

All transfer movements performed by the operator should be done with feet separated for good balance and knees bent to protect against back strain.Preparation for a Wheelchair Transfer

Before beginning the transfer procedure, the hygienist explains the steps to reduce client fear. If the client is expected to assist with the transfer, the client is informed of how and when assistance is needed. A simulation is helpful before the actual procedure is performed, especially for clients who have never been transferred. When preparing for a wheelchair transfer, the hygienist does the following:

Positions wheelchair at a slight angle to the dental chair. Dental chair should be slightly lower than wheelchair.

Positions wheelchair at a slight angle to the dental chair. Dental chair should be slightly lower than wheelchair. Positions wheelchair wheels facing forward, and locks wheels. This stabilizes the chair and prevents tipping or slipping during the transfer.

Positions wheelchair wheels facing forward, and locks wheels. This stabilizes the chair and prevents tipping or slipping during the transfer. Removes footrests from chair or folds them back so that client’s feet do not become caught during the transfer. Client’s feet are gently placed on the floor to prevent spasm and to position feet for the transfer.

Removes footrests from chair or folds them back so that client’s feet do not become caught during the transfer. Client’s feet are gently placed on the floor to prevent spasm and to position feet for the transfer. Removes arms of both wheelchair and dental chair. If arm of dental chair is not removable, then position it as far back as possible so that it does not interfere with the transfer.

Removes arms of both wheelchair and dental chair. If arm of dental chair is not removable, then position it as far back as possible so that it does not interfere with the transfer. Checks area for any sharp edges, hazards, obstacles, or cords that could cause injury during transfer.

Checks area for any sharp edges, hazards, obstacles, or cords that could cause injury during transfer.Complications in Wheelchair Transfer

Muscle Spasms

Movement may stimulate muscle spasms, and the hygienist must be prepared to protect the client from injury if spasms occur. Continuous spasms are reduced by massaging the affected area or waiting until the muscle relaxes. Use of supportive pillows reduces the incidence of spasms induced by movement. Anxiety can also contribute to spasms; therefore fear and stress reduction strategies are used before a transfer is initiated.

Decubitus Ulcers (Pressure Sores)