Chapter 78Curb

The historical definition of curb is enlargement on the plantar aspect of the fibular tarsal bone (calcaneus) caused by inflammation and thickening of the (long) plantar ligament.1 There is confusion regarding the cause of curb; a seminal publication uses this historical definition in the text but describes curb as superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonitis in a figure legend.2 By ultrasonographic evaluation curb was redefined as a complex of soft tissue injuries that occurs on the distal plantar aspect of the tarsus.3,4 Long plantar (LP) desmitis is only one of many injuries that causes curb. However, the indelible term curb has been used for hundreds of years5 and is still useful to describe swelling of the distal, plantar aspect of the tarsus (excluding the calcaneal bursa and proximal aspect of the calcaneus). In the rest of this chapter, curb is used specifically to mean the clinically apparent soft tissue swelling of the plantar aspect of the tarsus seen best from the side. Conformational abnormalities or bony exostoses can mimic or contribute eventually to formation of curb.

Clinical Appearance of Curb

The convex profile typical of curb is best seen from the side (Figure 78-1). Careful evaluation of swelling from all perspectives, palpation, and thorough lameness examination are critical. Curb must be differentiated from other swellings of the hock, including capped hock, effusion, edema and fibrosis of the calcaneal bursa (see Chapter 79), tarsal tenosynovitis (see Chapter 76), thoroughpin (with or without involvement of the tarsal sheath), and bony enlargements of the distal hock region (see Chapter 44). Injuries of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) as it courses along the plantaromedial aspect of the hock within the tarsal sheath can produce typical signs of curb, but they account for only a small percentage of injuries in horses with curb.

Fig. 78-1 A Standardbred racehorse with typically appearing curb. Swelling associated with the distal, plantar aspect of the tarsus is centered over the centrodistal and tarsometatarsal joints. In this horse swelling was caused by superficial digital flexor tendonitis.

Horses with sickle-hocked conformation are said to be curby (see Chapter 4). Sickle-hocked and in-at-the-hock conformation lead directly to curb, a finding most common in Standardbred (STB) and Thoroughbred (TB) racehorses. Prognosis for STB racehorses with sickle-hocked conformation and curb is worse in a trotter than in a pacer. Trotters with sickle-hocked conformation are usually fast early in training and racing, but this conformation is often career limiting. Sickle-hocked conformation is also undesirable in TB racehorses. Horses with sickle-hocked conformation often develop curb first, but they then independently or concomitantly develop other lameness associated with the distal hock joints. Tarsal region lameness begins with curb in 2- and 3-year-olds and progresses to osteoarthritis of the centrodistal and tarsometatarsal joints or slab fractures of the central tarsal bone, or more commonly the third tarsal bone.

Horses can have curby conformation without developing curb, and horses with normal hindlimb conformation can develop curb. The proximal aspect of the fourth metatarsal bone (MtIV) is often prominent in horses with sickle-hocked conformation. The most dramatic example of altered joint morphology occurs in young foals with tarsal crush syndrome, the result of delayed or incomplete ossification of the tarsal cuboidal bones (see Chapter 44).

Firm, fibrous soft tissue swelling can develop just proximal to the MtIV as a sequela to injection or local analgesia of the tarsometatarsal joint, presumably from local trauma, hemorrhage, or leakage into the subcutaneous tissues. Mild bony proliferation or fragmentation of the proximal aspect of the MtIV, or of the fourth tarsal bone, can cause focal swelling easily mistaken for curb.

Considerable variation in clinical signs occurs, and the injury cannot be categorized, or a management program and prognosis established, without thorough clinical and ultrasonographic examinations. Historically, owners and trainers consider curb to be an annoying, self-limiting problem that rarely causes lameness or poor performance, that responds to a single treatment that is uniformly effective, and that is cured by treatment. Most racehorse trainers are opposed to resting a horse with curb unless lameness is performance limiting, so veterinarians often are faced with management decisions without an option for even short-term rest or a reduction in training intensity. Many traditional therapies have no data to support efficacy. Thus, progress in understanding and management of this complex soft tissue injury has been limited.

Lameness ranges from none, mild, or severe depending on the structure involved and extent of injury. Lameness tends to be worse if the soft tissue structure involved is located dorsal to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) in the plantar aspect of the tarsus (i.e., the DDFT and/or the long plantar ligament [LPL]), if SDFT injury is diffuse, or if a mixed injury involves more than one structure. Diagnosis is straightforward in horses with obvious lameness seen at a trot in hand and painful swelling, but lameness may be evident only as a slight loss of performance or unlevelness when the horse is performing maximally and may be perceived only by trainers, drivers, or riders. A horse with chronic curb may not exhibit signs of pain during palpation, or lameness at a trot in hand, but can show lameness at speed, and convincing a trainer that the long-term swelling is a source of pain may be difficult. The area should be palpated carefully with the limb bearing weight and flexed. Swelling may be firm and fibrous, with few signs of active inflammation, or may be warm, painful, and edematous. Acute, compliant, or mushy swelling is associated with hemorrhage or other subcutaneous fluid accumulation and sometimes deeper soft tissue injury. Horses with this form of curb usually have acute, moderate-to-severe lameness. Horses with distal hock joint pain often exhibit a painful response when direct pressure is placed on plantar hock structures, including the SDFT, proximal aspect of the MtIV, second metatarsal bone, and proximal aspect of the suspensory ligament. Often swelling is not detected in these horses. Response to upper limb flexion varies and is nonspecific. Direct digital palpation followed by trotting is useful, because horses with active inflammation show increased lameness.

Because horses with curb can have concomitant osteoarthritis or other problems of the distal hock joints, differentiation of the source of pain is important but difficult. Diagnostic analgesia is useful but not foolproof. If horses are lame at a trot in hand, local infiltration of local anesthetic solution subcutaneously over the curb is effective. A minimum of 20 to 30 mL of local anesthetic solution should be infiltrated along the lateral, plantar, and medial aspects of the curb. Small-gauge needles should be avoided (to avoid needle breakage), and the injection should be performed with the limb in flexion, because horses may object to several injections. If horses are not visibly lame at a trot in hand, examination at the track or under saddle should be performed. Selective intraarticular analgesia of the distal hock joints and sequential perineural analgesia to rule out the lower limb are essential. A tibial nerve block alleviates pain with curb, but it is seldom done because other common sources of pain are abolished similarly.

Radiography and scintigraphy help differentiate other sources of pain, but ultrasonography is the imaging method of choice to determine which structures are involved and the extent of damage.

Applied Anatomy and Normal Ultrasonographic Examination of the Plantar Aspect of the Tarsus

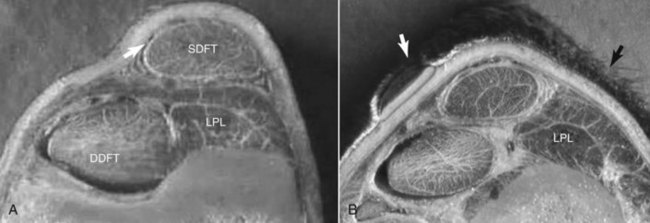

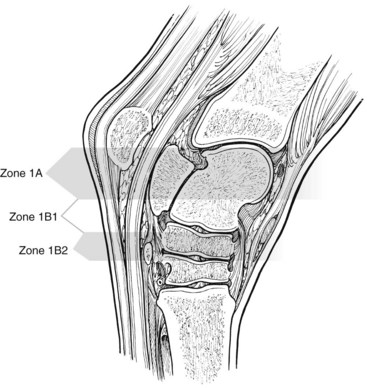

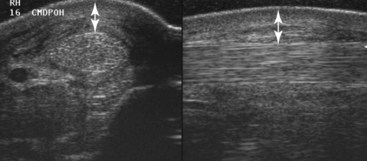

Plantar to the calcaneus are skin, subcutaneous tissues, a thin fibrous tissue layer, the SDFT, and the LPL (Figure 78-2). Medially the DDFT courses distally over the sustentaculum tali, within the tarsal sheath. Normally the tarsal sheath has a small amount of fluid that can be seen during ultrasonographic examination, but it is not felt. The LPL originates from the calcaneus, closely adheres to this bone, and inserts distally on the plantar surface of the fourth tarsal bone and the MtIV. The plantar aspect of the tarsus can be divided into zones to classify findings (Figure 78-3) or the distance measured from the proximal aspect of the calcaneus (point of hock). Swelling comprising curb occurs in zone 1 of the tarsal and metatarsal regions but can extend into zone 2 if SDF tendonitis occurs. Transverse and longitudinal images of both limbs should be obtained from the plantar midline, plantaromedial (to evaluate the DDFT), and slightly plantarolateral (to evaluate the distal aspect of the LPL). Measurement of cross-sectional area (CSA) is important to confirm lesions in which enlargement has occurred but with no overt fiber damage. Precise placement of the ultrasound transducer is important because the LPL changes size and shape as it courses distally. Knowledge of normal ultrasonographic anatomy is crucial (Figures 78-4 to 78-7).3,4

Fig. 78-2 A, Cross-section of the left tarsus at the level of zone 1A (lateral is to the right and plantar is uppermost). At this level the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and long plantar ligament (LPL) are located on the plantar aspect of the calcaneus, and ultrasonographic examination of these structures is completed with the transducer on the plantar midline. For imaging of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), the transducer must be positioned plantaromedially. In this specimen from a normal horse the thin peritendonous and periligamentous tissue (arrow) layer can be seen. B, Cross-section of the left tarsus distal to the section shown in A at the level of zone 1B2 (same orientation as A). Note that the LPL is now located plantarolaterally; for accurate anatomical and cross-sectional data information regarding the LPL to be obtained, an ultrasound transducer must be placed along the plantarolateral aspect of the limb (black arrow). At this level the DDFT is located plantaromedially, and for accurate depiction of this structure ultrasonographically the transducer must be placed on the plantaromedial aspect of the limb (arrow).

Fig. 78-3 The plantar aspect of the tarsus is divided into zones 1A and 1B. Because zone 1B is rather large and important, the zone is sometimes subdivided into 1B1 and 1B2. An alternative technique for recording level of injury is to measure distally from the proximal aspect of the calcaneus.

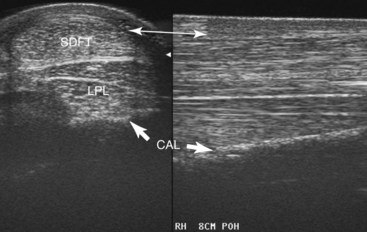

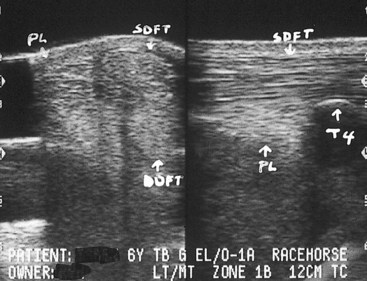

Fig. 78-4 Transverse (left) and longitudinal (right) midline ultrasonographic images at 8 cm distal to the point of the hock. A thin subcutaneous fibrous tissue layer runs along the plantar surface of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) (double-headed arrow). The SDFT (crescent-shaped) is narrower in a medial-to-lateral direction and somewhat thickened compared with further proximally. In the longitudinal scan the normal SDFT has a dense parallel fiber pattern. Deep to the SDFT the long plantar ligament (LPL) is at full thickness (plantar-to-dorsal direction), is rectangular, and is attached firmly to the calcaneus (CAL). At this level the deep digital flexor tendon is out of view medially and must be evaluated by placing the transducer plantaromedially.

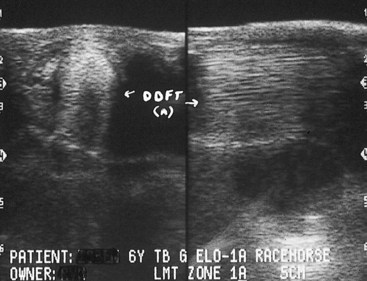

Fig. 78-5 Transverse (left) and longitudinal (right) ultrasonographic images from the plantaromedial aspect of the left hock 5 cm distal to the point of the hock. In the transverse image the tarsal sheath surrounds the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT). The tendon is oval and has a large eccentric hypoechoic region composed of residual muscle tissue, but this defect could be caused by incident angle artifact.

Fig. 78-6 Transverse (left) (medial is to the right) and longitudinal (proximal is to the left) (right) plantarolateral ultrasonographic images 9 cm distal to the point of the hock at the level of the fourth tarsal bone (T4). The long plantar ligament (PL) is a multiseptated structure, and large plantar fiber bundles are not normally perfectly aligned with dorsal bundles. In transverse images the PL normally may appear to lack echogenicity, and the size and shape change at the insertion on the fourth tarsal bone. The PL is wide at the insertion on the fourth tarsal bone (longitudinal scan).

Fig. 78-7 Transverse (left) (medial is to the left) and longitudinal (right) (proximal is to the right) plantarolateral ultrasonographic images 12 cm distal to the point of the hock, just distal to the insertion of the long plantar ligament (LPL) on the fourth tarsal bone (T4). The LPL is thick in the plantar-to-dorsal direction. A midline image would show the superficial digital flexor tendon and deep digital flexor tendon, but at this level a plantarolateral transducer placement is needed to assess the LPL. In the transverse image the normal heterogeneous fiber pattern of the LPL and cross-sectional area measurement can be seen. In the longitudinal image the LPL is seen attaching to the fourth metatarsal bone (MtIV) distally.

Curb: A Collection of Soft Tissue Injuries3

One hundred and ten horses with curb were examined using ultrasonography, including 87 (79%) racehorses (72 STB and 15 TB) and 23 nonracehorse sports horses (six field or show hunters, six Western performance horses, four show jumpers, two event horses, two gaited horses, two horses of unknown use, and one dressage horse).3 Mean and median ages (range 1 to 13 years) were 3.4 and 3.0, respectively. There were 32 late yearlings or 2-year-old horses, of which all were STBs; 24 of these STBs were examined before or near the time of a qualifying race. There were 24 intact males, 35 females, and 51 geldings. No sex predilection was found. Curb occurred in the left hindlimb (LH) in 60 horses, right hindlimb (RH) in 37 horses, and bilaterally in 13 horses. Of the 13 horses with bilateral curb, 11 were STBs. Within STBs there were 61 pacers and 11 trotters, compared with an expected population (ratio of pacers:trotters is 3:1 in North America) of 54 pacers:18 trotters. Curb was thought to result from excessive stress or strain from race training (80 horses), direct trauma (11 horses), previous injection (three horses), associated injuries (three horses), and an apparent “bad step” or unknown cause (13 horses). The most common reported form of direct trauma was stall or wall kicking. Curb was the primary reason for examination in 94 horses, was a compensatory lameness in 10 horses, and was seen in association with other tarsal injury or ipsilateral hindlimb lameness in six horses. Sixty-three horses were lame, and although lameness score was not uniformly recorded in the medical record, recorded lameness scores ranged from 1 to 2 out of 5. Horses with LP desmitis, those with SDF tendonitis extending distally from zone 1 into zone 2 of the proximal metatarsal region, those with deep digital flexor (DDF) tendonitis, and those with combined soft tissue injuries exhibited most pronounced lameness. Swelling (prominence of curb) was pronounced in horses with recent or combined soft tissue injury and in those with hematoma or abscess formation in the peritendonous and periligamentous (PT-PL) tissue. Swelling was described as fibrous in nature in many horses, particularly in STBs in which curb was chronic and in horses in which previous management included cryotherapy, topical counterirritation, or thermocautery. However, in acute injuries the swelling was often edematous, warm, and painful on palpation.

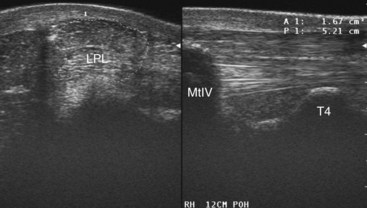

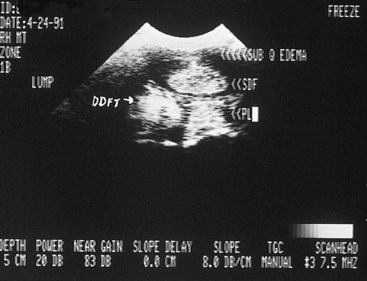

Ultrasonographic diagnosis included peritendonous-periligamentous (PT-PL) swelling without injury of the SDFT, DDFT, and LPL (29 [26%] horses) (Figures 78-8 to 78-10), PT-PL swelling primarily consisting of hematoma (six horses), and PT-PL swelling primarily consisting of abscess formation (five horses). Overall, 40 (36%) horses had swelling confined to the PT-PL tissues without other underlying soft tissue injury. There were 32 (29%) horses with PT-PL swelling and SDF tendonitis (Figure 78-11); 25 horses with PT-PL and LP desmitis (Figure 78-12); five horses with LP desmitis alone; five horses with DDF tendonitis; complex tarsal soft tissue injury of the LPL, PT-PL tissues, and gastrocnemius tendon in two horses; and tarsocrural collateral desmitis in one horse. Overall, only 32 (29%) horses had involvement of the LPL.

Fig. 78-8 Transverse midline ultrasonographic image (medial is to the left) of the plantar aspect of the hock of 2-year-old Standardbred gelding obtained in zone 1B. There is subcutaneous edema (arrows) and thickening. The superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT), deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), and long plantar ligament (PL) were normal. This horse was managed using a peritendonous injection of corticosteroids.

Fig. 78-9 Transverse (left) (medial is to the left) and longitudinal ultrasonographic images of zone 1B2 of the right hock in a 2-year-old trotter with curb. Thickening and mild fluid accumulation in the peritendonous and periligamentous tissues (double-headed arrow) are present, but the underlying soft tissue structures are normal. In the longitudinal image the plantar swelling giving the clinical profile associated with curb can distinctly be seen.

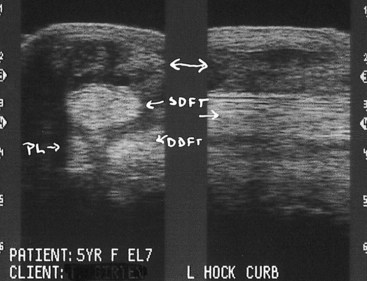

Fig. 78-10 Transverse (left) (medial is to the right) and longitudinal midline ultrasonographic images of the hock in zone 1B in a 5-year-old Thoroughbred racehorse. There is soft tissue swelling of heterogeneous echogenicity of the peritendonous and periligamentous tissues and fibrous adhesion (double-headed arrow) plantaromedial to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT). The SDFT, deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), and long plantar ligament (PL) are normal.

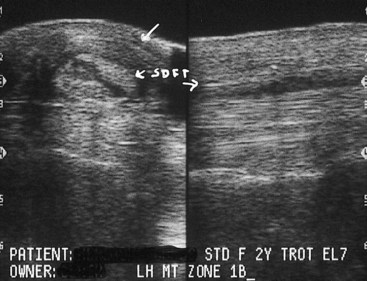

Fig. 78-11 Transverse (left) and longitudinal midline ultrasonographic images of the plantar aspect of the hock of 2-year-old Standardbred racehorse with curb resulting from peritendonous and periligamentous tissue injury and superficial digital flexor tendonitis. Subcutaneous fibrous tissue accumulation (top arrow) plantar to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and a central anechoic lesion of the SDFT can be seen, findings verified in the longitudinal view. Cross-sectional area of the affected superficial digital flexor tendon was 33% greater than that of the contralateral normal tendon.

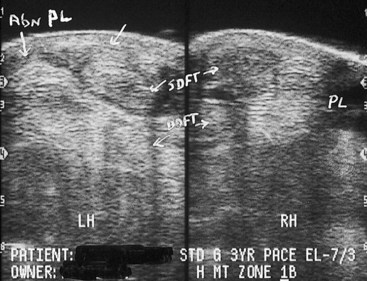

Fig. 78-12 Transverse plantarolateral ultrasonographic images of the left hindlimb (LH) (abnormal) and right hindlimb (RH) (normal) plantar tarsi in zone 1B of 3-year-old Standardbred pacer. The left long plantar ligament (PL) is enlarged, with an indistinct central hypoechoic lesion. DDFT, Deep digital flexor tendon; SDFT, superficial digital flexor tendon.

Management and outcome in these 110 horses with curb were difficult to assess, and information in medical records was lacking. There was a tendency for clinicians to manage horses with curb that were not lame or those in which curb was a compensatory issue with subcutaneous injections of a corticosteroid-containing preparation in combination with a reduction in exercise intensity or a short period of rest. Most of these horses had PT-PL swelling. Horses in which curb caused actual lameness were generally managed with rest and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) administration, but cryotherapy and topical counterirritation were often performed as well. Horses with severe SDF tendonitis extending into zone 2, LP desmitis, DDF tendonitis, or combination soft tissue injury were given long-term rest (>3 months) and controlled return to exercise, but they were the group most likely to do poorly or to remain lame. Horses (five) with PT-PL swelling and abscessation had surgical drainage and appropriate antimicrobial therapy and successfully returned to exercise. Associated ipsilateral lameness conditions included osteoarthritis of the centrodistal and tarsometatarsal joints and metatarsophalangeal joint pain.

Curb was previously described as simply LP desmitis,1,2,5 but is a collection of plantar tarsal soft tissue injuries. In fact, in 68% of horses with curb in this study, the LPL was normal ultrasonographically, and horses with curb were more likely to have injury of the PT-PL tissue alone or in combination with SDF tendonitis than injury of the LPL.3 Curb should not be used synonymously with LP desmitis. Although not directly studied, CSA measurement (see Figure 78-7) of all soft tissue structures should routinely be performed and compared with measurements from the contralateral limb (some horses are bilaterally affected), because common forms of SDF tendonitis and LP desmitis are often associated with increased CSAs rather than frank fiber tearing.

Curb is primarily an injury of racehorses, especially STBs. Gait, speed, and training methods differ between racing breeds, and STB racehorses have a higher prevalence of conformational abnormalities, such as sickle-hocked and in-at-the-hock conformation. These conformational abnormalities have not been directly studied, and a cause-and-effect relationship is therefore difficult to establish. However, sickle-hocked conformation may increase load on the distal plantar soft tissue structures, predisposing to curb. Weight and load distribution are considerably different in STBs and TBs. Curb develops frequently in STB racehorses that train and race on a thin, near-hard surface, contrary to many soft tissue injuries that result from work on deep surfaces. Many curbs develop in young STB racehorses early in training when they are jogging and not formally performing speed work. In some instances track surfaces are inconsistent and perhaps slippery, because early training is done in the winter months. In many horses clinical signs are recurrent and progressive, and the development of clinical signs early in training supports a theory that curb develops primarily as a result of overload of plantar soft tissue structures, in a roughly plantar-to-dorsal direction, because the most common tissue involved is the PT-PL tissues. For instance, in our study SDF tendonitis was not seen in horses without PT-PL tissue enlargement, suggesting that PT-PL injury may have preceded injury of the SDFT.3 Pronounced lameness in horses with SDF tendonitis was seen only when injury progressed distally into zone 2 in the proximal metatarsal region; in some horses sickle-hocked conformation and alleged loss of support of the hock produced what appeared as a dropped hock. Horses with this form of curb, LP desmitis, or combination injury are most likely to be lame. Curb was more common in the LH limb, and although it is tempting to associate this finding with counterclockwise training, many horses developed curb before speed work commenced in that direction. Perhaps in STBs the conventional practice of giving horses many slow miles of jogging in a clockwise direction may place additional load on the outside LH, predisposing to curb. Curb appears more common in pacers than trotters. Nonracehorse sports horses develop curb, but only sporadically, and lameness is often moderate to severe and most commonly is associated with PT-PL tissue swelling, although other structures are sometimes involved.

Peritendonous and Periligamentous Inflammation

PT-PL tissue swelling occurs alone or with abnormalities of one or more of the SDFT, DDFT, or LPL. PT-PL tissue injury can occur secondary to direct trauma from horses kicking a wall or trailer door, or rarely from a direct kick or interference injury from another horse, resulting in acute, large, painful swelling. Ultrasonographic examination most often reveals frank hemorrhage and edema. More commonly the horse has neither a history of trauma nor clinical findings suggesting trauma. We suspect that PT-PL tissue injury reflects excess loading or strain of the plantar tarsal soft tissue structures from race training. Extensive jogging of young STBs early in training may cause dramatic increase in hock loading, and tension and overstretching of thin PT-PL tissue occurs. PT-PL tissue injury may be an accumulated overload injury and may develop secondarily to other lameness. The PT-PL tissue is most plantar in location, is thin, may be most vulnerable to injury from abnormal strain, and may be the first tissue in progression to be injured. Conformational abnormalities may predispose the horse to such injuries. The cause of such soft tissue injury in mature nonracehorses is unknown, and although swelling can develop with relatively mild lameness, more often lameness is moderate to severe.

Clinical examination reveals localized soft tissue swelling, often with heat and pain on palpation, with or without lameness. Previous application of liniments or blisters or pin firing may create sore skin and considerable soft tissue swelling. Ultrasonographic findings depend on the duration of the injury. Acute lesions have an accumulation of anechoic fluid subcutaneously; in more chronic injuries, swelling is from subcutaneous echogenic material (see Figures 78-8 to 78-10). The SDFT, DDFT, and LPL should be inspected carefully, but they are frequently normal.

Management depends on the degree of lameness, the stage of training, the race or competition schedule, and the owner’s or trainer’s wishes. Blistering is used widely, but we question its value. Although not supported by scientific evidence, thermocautery (pin firing) appears to be an effective management tool, perhaps because it enforces rest. However, prolonged rest is rarely necessary in racehorses, and many horses can be managed by local injection of corticosteroids (triamcinolone acetonide, 9 mg) without substantial interruption of training. More than one treatment may be required if the swelling and lameness do not resolve. A lame horse must be rested to prevent injury to deeper structures. In nonracehorses with moderate-to-severe lameness, lameness may take several weeks to resolve. If the swelling becomes firm, fibrous, and pain free but lameness recurs, further investigation is warranted, because other causes of tarsal pain often develop in STB and TB racehorses with curb.

Infection can occur from direct trauma with skin penetration, previous injection, or severe topical counterirritation. If infection is suspected, cytological examination and culture are indicated. If a hematoma resulting from trauma is large or recurrent or if the curb is infected, establishing drainage is often necessary. A distal incision is made to provide drainage, and fibrin and debris are removed. Care must be taken to avoid penetration of the tarsal sheath when creating the incision. A drain is inserted if necessary, and the hock is bandaged. Culture usually reveals Staphylococcus species, and appropriate antimicrobial and NSAID therapy is instituted. Horses are rested for 2 to 3 weeks to allow the tissues to heal, even though lameness from PT-PL tissue injury was not present before infection developed. Prognosis in horses with infection of PT-PL tissues is excellent but is far worse in those with infection of the SDFT, DDFT, or tarsal sheath.

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

A common finding in horses with curb is SDF tendonitis. Sickle-hocked conformation may predispose the horse to tendonitis, which can occur alone but rarely is seen without concomitant inflammation of the PT-PL tissues. Pathogenesis likely involves progressive or accumulated overload injury of first the thin, fragile PT-PL tissues and later the SDFT.

Previous PT-PL tissue injury appears to predispose to subsequent SDF tendonitis if the training level is increased quickly. PT-PL injury may simply be an early stage of a progressive lesion that eventually involves the SDFT or LPL. Progressive injury occurs frequently if horses with PT-PL tissue injury are treated with cryotherapy, internal blisters, or corticosteroids, and training intensity is accelerated before mature fibrous tissue can form. In horses with PT-PL tissue injury and SDF tendonitis, lameness varies, but it is much more likely to be observed than in horses with only PT-PL tissue injury. Lameness may be acute in onset and often is seen at fast speeds, but it can be seen in some horses at a trot in hand. SDF tendonitis occurs commonly in young STB racehorses but usually at a later stage of training than PT-PL tissue injury. Ultrasonographic examination reveals enlargement of the CSA of the SDFT, with a variable change in echogenicity and fiber pattern, depending on the severity of the injury (see Figure 78-11). Often, subcutaneous edema or fibrosis occurs, depending on the chronicity of the injury.

In horses with SDF tendonitis, rest is an important part of management. Lesions usually are localized to the plantar aspect of the tarsus; those extending farther distally are associated with more severe lameness, and horses have a poorer prognosis. Horses with localized lesions have a fair prognosis, although the prognosis is worse in trotters than in pacers. Horses with mild acute SDF tendonitis, with enlargement of the tendon without fiber tearing, should be rested for 3 to 4 weeks. Without rest, progressive fiber damage may occur, resulting in prolonged recovery. Horses with more severe injuries may require up to 4 months of stall rest and controlled walking exercise.

In some STB racehorses actively racing, SDF tendonitis can be managed symptomatically, without giving rest, if the lesion is well localized and mild. Rest is always the best option but one often met with resistance from trainers. Mild lameness may be observed at speed or while the horse is trotting in hand, but severe lameness should not be evident. Ultrasonographic examination often reveals PT-PL tissue injury with enlargement of the SDFT, but core lesions are not present. In most horses local therapy using cold water hosing and poultice application, NSAID therapy, and subcutaneous injection of a corticosteroid preparation is successful. Subcutaneous injection of methylprednisolone acetate (200 mg) and Sarapin (25 mL) medial, plantar, and lateral to the SDFT is often done by practitioners with apparent success. Care is taken not to inject corticosteroids directly into the substance of the SDFT and LPL. Horses are given 10 to 14 days of jogging and light training before racing again. Nonracehorses with localized lesions usually respond well to rest for up to 3 months and have a favorable prognosis. Intralesional injections of fresh bone marrow, platelet-rich plasma, cultured stem cells, or other preparations may help healing and improve long-term prognosis, but we currently have no experience with intralesional therapy in this location.

Horses with severe SDF tendonitis have severe mushy swelling. If not given rest, these horses develop progressive tearing of the SDFT distal to the hock in the metatarsal region and lose support of the hock. Long-term rest (9 to 12 months) is recommended, but prognosis for return to previous race class is poor and in trotters, grave.

Deep Digital Flexor Tendonitis

DDF tendonitis is a rare cause of curb. Horses with curb resulting from DDF tendonitis are usually acutely lame and have substantial swelling. Mixed injury with DDF tendonitis accompanying SDF tendonitis and LP desmitis occurs, but it is unusual. Horses with DDF tendonitis have concomitant PT-PL tissue inflammation and effusion of the tarsal sheath (tenosynovitis). The DDFT simply can be enlarged compared with the contralateral limb or can have anechoic or hypoechoic core lesions. During ultrasonographic examination, the DDFT should be evaluated carefully from the midline and plantaromedial aspects. Lameness often is pronounced, and rest is recommended for a minimum of 4 to 6 months, but prognosis is guarded because lameness can recur. Serial ultrasonographic examination, corrective shoeing, and controlled exercise are given.

Long Plantar Desmitis

LPL injury usually causes acute lameness, but chronic soft tissue swelling and progressive lameness can occur. Soft tissue swelling often is pronounced. Although LP desmitis can occur in racehorses, this form of curb appears to be equally common in other types of horses, such as Western performance horses. In one of the Editor’s experience (SJD) LP desmitis is rare in sports horses in Europe. LP desmitis can be well localized or diffuse. Cross-sectional measurements of the LPL are critical, because desmitis often manifests as ligament enlargement rather than overt fiber tearing. Subtle thickening of the LPL may cause high-speed lameness, and evaluation of the CSA may be the only method to identify early lesions in these horses. Lesions can occur at any level within zones 1A and 1B, and injury may involve the insertion of the LPL on the MtIV (see Figure 78-12).

Conservative management is best for horses with LP desmitis, because lameness and swelling often are pronounced. Owners and trainers of nonracehorses are often open to a conservative approach involving ample rest (3 months) to rehabilitate horses with curb properly. Intervening with therapy to enforce rest is not necessary. Controlled return to exercise is straightforward in this type of horse, because walking and trotting under saddle can be given easily. Graded exercise programs are not administered as easily or desired in STB racehorses compared with nonracehorse sports horses. Lunging and walking and trotting under saddle are usually not practical, although riding trotters is popular among trainers originally from Europe. Walking and light jogging in a jog cart are the best methods for graded exercise in a STB racehorse. We do not recommend turnout exercise in any horse with soft tissue injury, because we feel strongly that this prolongs recovery and may lead to reinjury, but we realize our recommendations may not be followed. Cryotherapy, topical counterirritants, subcutaneous injections, and thermocautery are less likely to influence inflammation and healing of the LPL than more superficial causes of curb, but these treatments are sometimes requested. As experience is gained with intralesional therapy for management of soft tissue injuries in horses, it will undoubtedly be applied to injuries in the plantar aspect of the tarsus.

Curb can result from LP desmitis at its insertion on the MtIV. These horses do not have extensive swelling but focal thickening just proximal to the MtIV. Mild soft tissue swelling must be differentiated from a prominent but normal MtIV seen in yearlings with sickle-hocked conformation. Horses with curb resulting from distally located LP desmitis show lameness and mild, focal swelling and are managed with rest.

Mixed Soft Tissue Injuries

Ultrasonographic examination of curb nearly always identifies PT-PL tissue inflammation and in many horses an abnormality of the SDFT, DDFT, or the LPL. Occasionally, however, simultaneous injury of the SDFT and LPL occurs in addition to PT-PL tissue inflammation. This is most common in nonracehorse sports horses, in which lameness and swelling are severe. Long-term rest is recommended, but prognosis is guarded.