Chapter 79Bursae and Other Soft Tissue Swellings

A bursa is a flattened, closed sac interposed between structures subject to friction or at points of unusual pressure, such as bony prominences and tendons. Bursae are lined with a cellular membrane resembling synovium and are classified according to position (subcutaneous, subligamentous, submuscular, and subtendonous) and according to the method of formation (congenital or acquired).

Acquired bursae develop because of pressure and friction over bony prominences. Tearing of the subcutaneous tissues results in accumulation of transudative fluid, which becomes encapsulated by fibrous tissue. In chronic injuries fibrous bands may develop within the capsule.

Supraspinous Bursa

The supraspinous bursa overlies the summits of the dorsal spinous process of the second to fifth thoracic vertebrae, under the funicular part of the nuchal ligament. Inflammation of the supraspinous bursa and surrounding soft tissues, so-called fistulous withers, is usually infectious in origin and may be a sequela to trauma. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, Brucella abortus, and Onchocerca cervicalis have been considered important causative agents.1-3

Clinical signs of supraspinous bursitis are generalized soft tissue swelling, heat and pain, and often draining tract(s). Osteitis or osteomyelitis of the dorsal spinous processes of the cranial thoracic vertebrae may be concurrent. Care must be taken not to misinterpret the normal granular radiopaque appearance of normal, incompletely ossified summits of the dorsal spinous processes.4 Diagnostic ultrasonography and radiology are useful for determining the extent of the infection, for identifying a foreign body, and for evaluating signs of osteitis or osteomyelitis.

Treatment is by aggressive surgical debridement of all infected tissue and establishment of adequate drainage, taking care not to penetrate the dorsoscapular ligament. Several surgical procedures may be required to resolve the infection successfully.1-3

Trochanteric Bursa

The Editors have no clinical experience of trochanteric bursitis. This condition is discussed further in Chapter 47.

Calcaneal Bursa

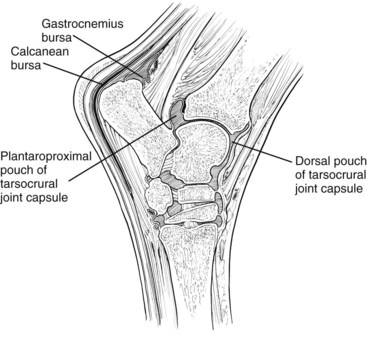

The calcaneal or intertendonous bursa lies between the tendons of the gastrocnemius and the superficial digital flexor muscles, proximal to the hock, and extends distally on the plantar aspect of the calcaneus to the distal aspect of the hock (Figure 79-1). In most horses a communication exists between the calcaneal bursa and the gastrocnemius bursa. There is communication between the calcaneal bursa and the subcutaneous bursa in 37% of horses.

Fig. 79-1 Diagram of a sagittal section of the hock region showing the relative positions of the calcaneal and gastrocnemius bursae.

Injuries of the calcaneal bursa are not common and are usually the result of trauma. However, mild distention of the calcaneal bursa often is seen with gastrocnemius tendonitis (see page 803). Mild distention also may be seen unilaterally or bilaterally, as an incidental finding unassociated with lameness.5 Primary inflammation of the bursa results in acute-onset lameness associated with distention of the bursa. Hemorrhage into the bursa also may occur. Conservative management by rest, with or without injection of short-acting corticosteroids, usually results in resolution of lameness, although enlargement of the bursa may persist.

More commonly, infection of the bursa is caused by a penetrating injury or is secondary to infectious osteitis of the calcaneus6,7 (see Chapter 44).

Chronic distention of the calcaneal bursa also has been seen with well-circumscribed osteolytic lesions on the tuber calcanei, which were thought to represent enthesopathy at the insertion of the gastrocnemius tendon.8

Further investigation should include diagnostic ultrasonography, radiography of the calcaneus, and synoviocentesis. Radiographic examination should include a flexed skyline image of the calcaneus.9 The internal structure of the bursa may be evaluated endoscopically,10 but some underlying bony lesions may not be visible if the insertion of gastrocnemius is intact.8 Endoscopy has been used diagnostically and therapeutically in horses with infectious osteitis, or bursitis, and in those with osteolytic lesions.

Horses with primary infection of the calcaneal bursa should be treated by debridement and lavage of the bursa and broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy. Horses with infectious and noninfectious lesions of the calcaneus have been managed conservatively and surgically, with rather disappointing results.6-8 Repeated surgeries are often required, and a substantial number of treated horses have persistent lameness.

Subcutaneous Abscess over the Tuber Calcanei

Puncture wounds in the region of the hock frequently result in penetration of the calcaneal bursa and infectious bursitis. Less commonly a subcutaneous abscess develops associated with firm, painful swelling on the plantar aspect of the hock and lameness. The extent of soft tissue swelling may make accurate palpation difficult, and ultrasonography is essential to determine whether or not the calcaneal bursa is involved. Radiographic examination of the calcaneus is also required. Treatment is by radical surgical debridement. The long-term functional outcome is usually satisfactory, although there is usually residual swelling (capped hock).

Gastrocnemius Bursa

The subgastrocnemius bursa usually communicates with the calcaneal or intertendonous bursa. Mild distention may be present, unassociated with lameness. Primary injuries of the gastrocnemius bursa are rare. The bursa may be distended in association with gastrocnemius tendonitis, resulting in a capped hock appearance (see page 804). Occasionally, infection may occur because of a puncture wound or extension of infection from the calcaneal bursa.

Capped Hock

A capped hock appearance may be caused by distention of the gastrocnemius bursa, distention of the subcutaneous bursa, or development of an acquired bursa over the tuber calcanei (see Figure 6-28). An acquired bursa develops because of repetitive trauma, such as the horse kicking the stable walls or leaning backward on its hindlimbs when traveling. Capped hock usually has no associated lameness. Protection of the hocks with hock boots may help to prevent deterioration.

Cunean Bursa

The cunean bursa lies underneath the cunean tendon on the medial aspect of the hock. Inadvertently penetrating the bursa is easy if one is inexperienced in injecting the centrodistal joint. Although the potential for primary bursitis exists, neither of the Editors of this text recognizes primary bursitis as a cause of lameness in racehorses or other sports horses. Gabel recognized a syndrome, “cunean tendonitis and bursitis–distal tarsitis syndrome of harness racehorses,” but appreciated that horses showed substantially better improvement in gait after intraarticular analgesia of the distal hock joints than after infiltration of the cunean bursa alone.11 Nonetheless, a component of periarticular soft tissue pain may occur in Standardbred trotters and pacers with distal hock joint pain, and treatment of the cunean bursa with corticosteroids frequently is used as part of management. Cunean tenectomy is practiced by some, but it has largely fallen from favor. Subcutaneous injection of corticosteroids and Sarapin over the proximal aspect of the second metatarsal bone may yield better results than medication of the cunean bursa.5

Capped Elbow

A capped elbow is an acquired bursa that develops over the olecranon of the ulna. The bursa results from repeated trauma from the heel of the shoe on the ipsilateral forelimb when the horse is lying down. The condition generally is not associated with lameness and is merely a cosmetic blemish. The use of a sausage boot around the pastern prevents trauma from the shoe, and usually the swelling diminishes substantially and rapidly in size. Horses with chronic injuries have been treated by injection of corticosteroids, orgotein, or dysprosium-165, with disappointing results, or surgically, with better cosmetic results.12

Acquired Bursa on the Dorsal Aspect of a Hind Fetlock

Firm swelling on the dorsal aspect of the hind fetlocks of horses that jump fixed fences is common. These lesions are false bursae that overlie the extensor tendon and are usually of no consequence, except cosmetically. However, a puncture wound may result in infection, causing enlargement of the bursa and surrounding soft tissue swelling, localized heat, and pain on palpation.5 In contrast to infection in a joint or tendon sheath, lameness is usually only mild to moderate. Ultrasonography is useful to better identify the causes of the soft tissue swelling, and diagnosis is confirmed by synoviocentesis and identification of many nucleated cells. Surgical treatment is required, and the prognosis is good.

False Thoroughpin

A thoroughpin is the colloquial name for distention of the tarsal sheath, but more commonly the term is misused to describe a variety of swellings that may develop in the distal aspect of the crus cranial to the gastrocnemius tendon. These conditions are otherwise called false thoroughpins and should be differentiated from distention of the tarsal sheath, tarsocrural joint capsule (see Chapter 44), or calcaneal bursa (see page 799). A false thoroughpin occurs laterally more commonly than medially and may develop unilaterally or bilaterally. A false thoroughpin varies in size from small to large. In contrast to distention of the tarsal sheath or the plantar outpouching of the tarsocrural joint capsule, these swellings cannot be balloted from laterally to medially and do not extend distal to the hock (Figure 79-2). They may be sudden or insidious in onset and may or may not be associated with lameness.

Fig. 79-2 Plantar view of a right hock. A false thoroughpin (arrow). The swelling in this horse was acute in onset, but it was unassociated with lameness. The horse was maintained in full work, and despite this the swelling reduced in size. Ultrasonographic evaluation revealed a unilocular fluid-filled cavity.

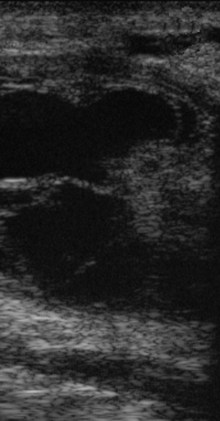

The causes vary and are poorly understood. False thoroughpins are usually solitary, fluid-filled sacs (Figure 79-3), unilocular or multilocular, with a wall of variable thickness, with or without large echogenic fibrous bands traversing them (Figure 79-4). They may develop secondary to local hemorrhage or because of herniation of the tarsal sheath or the calcaneal or gastrocnemius bursae.13-15

Fig. 79-3 Dorsolateral-plantaromedial oblique radiographic image of a hock. A positive-contrast radiographic study of false thoroughpin. This fluid-filled cavity did not communicate with the tarsal sheath.

Fig. 79-4 Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of a false thoroughpin. Proximal is to the left. There is a thick-walled fluid-filled cavity with some echogenic bands.

Diagnostic ultrasonography is useful to identify the nature and extent of the swelling (see Figure 79-4). Unlike the tarsal sheath, no tendon is within the cavity. Positive-contrast radiography can be used to demonstrate whether any communication exists between adjacent structures (see Figure 79-3).

A false thoroughpin may be an incidental clinical finding unassociated with lameness. The condition is seen commonly in horses with a base-narrow hindlimb conformation.5 Other causes should be excluded before one concludes that a false thoroughpin is the cause of lameness. Even if the swelling is acute in onset, in the absence of lameness I have maintained horses in work with no deleterious effects. Sometimes such swellings spontaneously reduce in size, but some swelling is likely to persist.

Long-term lameness associated with a false thoroughpin has been seen in a number of horses with chronic hindlimb lameness that has not responded to conservative management. Surgical excision of large multiloculated cystlike lesions has resolved lameness successfully in some horses,5 although cosmetic results may be disappointing.

Spherical Masses Close to the Fetlock

Small, focal, hard, nonpainful spherical swellings are sometimes seen on the palmarolateral (plantarolateral) or palmaromedial (plantaromedial) aspect of the fetlock adjacent to the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS). These do not generally cause lameness. Ultrasonographic examination reveals a fluid-filled mass. Lameness associated with herniation of the DFTS is discussed in Chapter 74, page 776.