Chapter 76The Tarsal Sheath

The tarsal sheath corresponds to the synovial sheath of the lateral digital flexor tendon at the level of the hock. Tenosynovitis of this sheath is a well-recognized condition1-6 and can be caused by a wide range of lesions. Nonpainful, chronic distention in the absence of obvious pathological lesions, often called idiopathic thoroughpin, is common and should be distinguished from other debilitating causes of tenosynovitis, many of which can cause persistent, severe lameness.7,8 Specific lesions within the sheath can be difficult to confirm clinically.8,9

Functional Anatomy

The deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) in horses is formed by the fusion in the proximal metatarsal region of the thin medial digital flexor tendon and the larger lateral digital flexor tendon.10-13 The two tendons pass within separate sheaths. The lateral digital flexor muscle covers the caudal aspect of the tibia and is joined by the tibialis caudalis muscle in the distal aspect of the crus. The tendon starts 2 to 4 cm proximal to the tarsocrural joint and passes medial to the tuber calcanei over a fibrocartilage-covered groove on the plantar aspect of the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus. The lateral digital flexor tendon passes over the thick plantar ligament on the distal, medial aspect of the tarsus, medial to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT), before being joined by the medial digital flexor tendon 1 to 3 cm distal to the tarsometatarsal joint.

The tarsal sheath is 16 to 20 cm long and starts near the musculotendonous junction of the lateral digital flexor tendon in the distal caudal aspect of the crus. At this level the tarsal sheath forms a large pouch between the lateral digital flexor muscle and the common calcanean tendon. The distended pouch is largest over the lateral aspect of the crus. At the level of the tarsocrural joint the sheath extends laterally to surround the lateral digital flexor tendon. Cranially a rigid groove is formed by fibrocartilaginous thickening of the tarsocrural joint capsule. The sheath terminates as a recess dorsomedial to the DDFT in the proximal third of the metatarsal region.

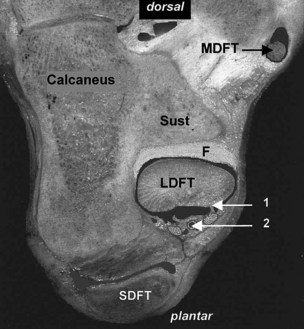

The tarsal sheath is enclosed at the level of the sustentaculum tali by a thick, transversely oriented ligament, the plantar retinaculum (Figure 76-1), and in the distal tarsus by a superficial fascia. The plantar nerves and vessels run within the retinaculum, in the plantar two thirds of its width, that is, plantar and plantaromedial to the lateral digital flexor tendon. The sheath is lined by a parietal synovial membrane with few villi, except distally. This membrane reflects plantarly to wrap around the tendon, leaving a thin but continuous membrane, or mesotendon, along the plantaromedial aspect of the lateral digital flexor tendon. This membrane carries vessels to the tendon and therefore should be preserved during surgery.

Fig. 76-1 Transverse section of the proximal tarsus, showing the lateral digital flexor tendon (LDFT) in the fibrocartilaginous groove (F) on the plantar aspect of the sustentaculum tali (Sust). Lateral is to the left. Vessels and nerves course within the retinaculum (2), lateral to the attachment of the mesotendon (1). MDFT, Medial digital flexor tendon; SDFT, superficial digital flexor tendon.

Causes of Tarsal Tenosynovitis

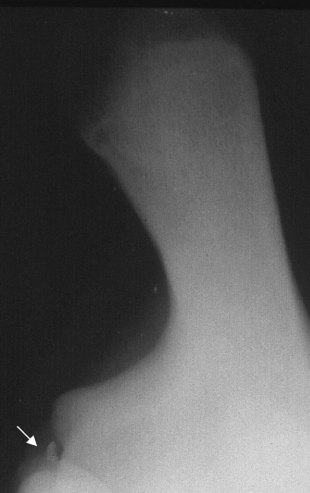

Distention of the tarsal sheath (Figure 76-2) is commonly termed thoroughpin, or true thoroughpin,14 but the condition may have distinct causes (see Figure 6-30).

Fig. 76-2 Distention of the tarsal sheath, giving the typical thoroughpin swelling, medially in the distal caudal aspect of the crus and proximal metatarsal region (white arrows) and laterally, caudal to the tibia (black arrow).

Idiopathic Thoroughpin

Slight to moderate distention of the tarsal sheath is often seen in young horses.8,9 It also occurs in adults, particularly in Warmbloods and Western performance horses and horses with a straight hock conformation, after extended box rest or transport. Effusion also may result from acute inflammation in nearby tissues, congestion, and edema in the distal limb (sympathetic effusion). The distention usually is not associated with signs of inflammation or lameness and tends to resolve spontaneously.8 However, the distention can become recurrent or persistent in some horses.

Traumatic Thoroughpin

Tenosynovitis may be induced by trauma, leading to acute inflammation and hemorrhage in the sheath. In my experience, direct trauma to the medial plantar aspect of the sheath is common and most often results from a kick by another horse. Tenosynovitis also may result from hitting hard objects during jumping or occasionally from interference from the contralateral hind foot. These traumatic injuries may be associated with a chip fracture or fragmentation of the medial edge of the sustentaculum tali at the insertion of the plantar retinaculum.3,13 Transverse fracture of the calcaneus involving the sustentaculum tali also was described.3 In most horses no signs of direct trauma are apparent, and overstretching, or sprain, which may or may not involve the lateral digital flexor tendon, is suspected of causing acute tenosynovitis.8,9 Intrathecal hemorrhage always causes substantial inflammation and pain and can induce the formation of fibrinous adhesions. The inflammation often leads to chronic distention, with synovial thickening, fibrosis, and fibrous adhesion formation between the lateral digital flexor tendon and parietal sheath lining, which occasionally can cause persistent pain and mechanical lameness. Acute tenosynovitis without overt lameness also has been described.9

Primary Lateral Digital Flexor Tendon Injuries

Sprain injuries to the lateral digital flexor tendon do occur in the tarsal sheath region and are characterized ultrasonographically by longitudinal fraying and irregular hypoechoic lesions at the level of the sustentaculum tali. These lesions may be caused by overstretching and compression of the tendon over the bone.

Infectious Tenosynovitis

Direct trauma to the medial aspect of the hock can result in breach and contamination of the tarsal sheath.3,9,13,15 The medial edge of the sustentaculum tali is the most prominent relief on the medial aspect of the tarsus, and a wound at this level often disrupts the retinaculum, thus opening the sheath.6,13 Puncture wounds are rare in my experience, but they may occur, especially in the distal caudal aspect of the crus. Iatrogenic contamination induced by intrathecal injection is also common and should be suspected in horses with worsening of the lameness and signs of inflammation after such injections.9 If untreated, suppurative tenosynovitis may lead to infectious tendonitis, destruction of the fibrocartilage, and eventually osteitis or osteomyelitis of the calcaneus.3,4,6,13 Infection also may result from extension of abscesses in adjacent tissues.

Diagnosis of Tarsal Sheath Injuries

Clinical Signs

Distention of the tarsal sheath is visible in the distal aspect of the crus, particularly laterally between the common calcanean tendon and the tibia and, to a lesser extent, on the medial caudal aspect of the crus (see Figures 6-30 and 76-2). Such distention should not be confused with swellings associated with the plantar pouch of the tarsocrural joint (see Chapter 44), situated farther distally between the tuber calcanei and distal aspect of the tibia (bog spavin) or with distention of other bursae, for example, the deep calcanean bursa and calcanean bursa of the SDFT (see Chapter 79).8,10 False thoroughpin may result from soft tissue masses such as hematomata, tarsal sheath herniation, granulation tissue,8,9 or abscesses (see Chapter 79). Distention of the tarsal sheath also may be detected in the proximal metatarsal region on the medial aspect of the DDFT.

In horses with idiopathic tenosynovitis, the swelling is soft and nonpainful and unassociated with lameness.9,16 In inflammatory conditions, swelling is soft, warm, and painful in the acute stage and nearly hard and rarely painful in chronic injuries. The degree of lameness varies.3,7 The level of pain is not always correlated with the severity of the condition. Prominent pain usually is induced by hock flexion in acute and chronic injuries, and the degree of hock flexion may be greatly decreased. Confirming that the lameness is associated with the sheath may be necessary by using intrathecal injection of 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic solution and by elimination of other sources of pain. Synoviocentesis may be difficult in horses with acute injuries because of edematous, hypertrophic, and congested synovial membrane.

Confirming infection is not always easy in all horses in the absence of a wound. Wounds over the sustentaculum tali always should be considered suspicious and warrant a contrast tenovaginogram or tenovaginocentesis.

Radiography

Radiographic examination is paramount in all horses with severe tarsal tenosynovitis to rule out fractures or osteitis of the sustentaculum tali and tuber calcanei (see Chapter 44).2-4,13 Lesions are most visible on dorsoplantar and dorsomedial-plantarolateral oblique images to highlight the medial and plantaromedial aspects of the calcaneus (Figure 76-3). A flexed skyline image of the plantar aspect of the sustentaculum tali (flexed proximocaudal-distoplantar image) is essential to demonstrate some lesions17 (Figure 76-4). Contrast radiography is also useful to highlight the surface of the fibrocartilage and the outline of the lateral digital flexor tendon18 but has been replaced largely by ultrasonography.12 However, contrast radiography remains a useful technique to confirm puncture wounds into the sheath. After collecting synovial fluid, 5 mL of an iodinated contrast medium mixed with 5 mL of Hartman’s solution is injected in the proximal pouch of the sheath, and lateromedial, dorsomedial-plantarolateral oblique, and dorsoplantar radiographic images are obtained to highlight a communication with the skin.

Ultrasonography

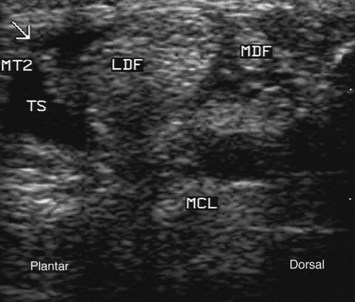

Ultrasonographic examination of the tarsal sheath is best performed with a linear 7.5-MHz or higher-frequency transducer. The lateral digital flexor tendon is best imaged from the medial aspect of the limb.12,13,19 Accurate imaging requires high-definition equipment and experience. The chestnut can be trimmed and soaked with warm water to improve imaging. In idiopathic distention, the sheath is filled with anechogenic fluid, and no evidence of synovial membrane hyperplasia is apparent. In acute tenosynovitis, the sheath is distended, and substantial thickening of the synovial membrane occurs. Hemorrhage is seen frequently as a hypoechogenic, whorl-like structure in the proximal pouch. Lesions may be seen in the lateral digital flexor tendon, but they are relatively rare. Longitudinal tears and superficial fraying are the most common types of lesions, but they should not be confused with hyperplasia of the visceral synovium covering the tendon. Early fibrinous adhesions may be visible. The integrity of the fibrocartilage groove and retinaculum can be assessed, and fragmentation of the edge of the sustentaculum tali may be detected.8,13 In chronic injuries, substantial fibrosis may be seen around the sheath, and often there are large adhesions between the lateral digital flexor tendon and parietal sheath, especially in the proximal pouch (Figure 76-5). The visceral lining is usually thick (several millimeters) and has increased echogenicity. Horses with chronic lameness and those that have received numerous injections of corticosteroids may have large, nodular fibrocartilaginous or partially mineralized masses, termed ossicles.2,9 Differentiating these from chip fractures or mineralization of the tendon or sheath lining without the use of tenoscopy may be difficult. Ultrasonography can help to differentiate true from false thoroughpin (see Chapter 79). Infection is characterized by severe inflammation of the synovial lining, and the fluid is often echogenic and heterogeneous because of the fibrin clots and debris.6,13 This may not be obvious early in the condition.

Fig. 76-5 Transverse ultrasonographic image of the tarsal sheath at the level of the tarsometatarsal joint obtained from the plantaromedial aspect. Plantar is to the left. There is hyperplasia of the synovial membrane around the lateral digital flexor tendon (LDF) and a well-organized adhesion between the tendon and parietal sheath wall (arrow). The tarsal sheath (TS) is distended. MCL, Medial collateral ligament; MT2, plantar border of the second metatarsal bone; MDF, medial digital flexor tendon.

Tenovaginocentesis

Tenovaginocentesis (collecting fluid from the tendon sheath) is useful to rule out infection and confirm inflammation.9,15 The fluid may be normal in appearance, but it is usually contaminated by blood. A moderate increase of cellularity (<8000/mcL) may be evident, except in horses with acute traumatic injuries where the nucleated cell count can exceed 10,000/mcL. Generally infection is associated with a thin, cloudy to purulent fluid and cell counts well in excess of 10,000/mcL. Note that centesis should be carried out after ultrasonography to avoid bleeding and gas artifacts.

Tenoscopy

Tenoscopy (see Chapter 24) is rarely necessary as a purely diagnostic method because the tarsal sheath is evaluated adequately with ultrasonography in most horses. A major exception is in infectious conditions, where it may be useful to assess potential damage to the fibrocartilages, which may not be visible with other diagnostic imaging methods.13,20

Management of Tarsal Tenosynovitis

Idiopathic and Traumatic Tenosynovitis

Treatment is of little value in horses with idiopathic tenosynovitis, which generally resolves spontaneously.8,9,16 Reduced (but not interrupted) exercise, sweats, and systemic antiinflammatory therapy can be helpful.9 It is not advisable to place a needle in the sheath because this may cause bleeding and subsequent inflammation.

Treatment of acute tenosynovitis is controversial. In the absence of tendon or bony lesions, rest, systemic or local nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), local dimethylsulfoxide creams, and cryotherapy (ice packs or cold hosing) are often effective.9 The horse should be rested in a box for 24 to 48 hours and then walked out in hand to reduce sheath fibrosis. Hyaluronan may be useful for horses with more severe tenosynovitis or in horses in which lateral digital flexor tendon lesions are present. Intrathecal corticosteroids may be useful in horses with acute tenosynovitis, but they certainly are contraindicated if tendon lesions exist. The latter carry a poor prognosis, except for superficial fraying.8,9 Bone fragments should be removed by tenoscopy because they can cause chronic inflammation and interference with the tendon.

In horses with more chronic tenosynovitis with associated lameness, corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone acetate (40 mg), triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg), or betamethasone have been used with varying success.8,9 Fluid retrieval to decrease the volume of the sheath, followed by rest and the application of pressure bandages may produce temporary relief of the distention,9 but recurrence is common, probably because of chronic proliferative synovitis. Recurrent swelling is often worse than originally seen. Repeated injections have been associated with mineralization of the tendon and synovial lining, and rupture of the lateral digital flexor tendon was reported9; therefore repeated injections are not recommended. If possible, the cause of the chronic inflammation should be ascertained. With bony fragments, ossicles, or adhesions, conservative treatment and medical therapy are often disappointing, and surgical debridement appears to be the most effective treatment.9,13 Debridement is best achieved by tenoscopy (see Chapter 24) (Figure 76-6). NSAIDs are administered for 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively, and the horse is restricted to box rest for 10 days, after which handwalking starts several times daily. The horse may be turned out in a small paddock or ridden gently after 2 to 3 weeks. Hyaluronan may be injected intrathecally at least 10 days after surgery.

Infectious Tenosynovitis

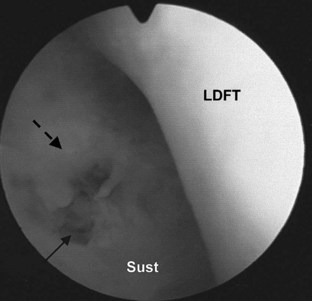

Horses with acute infectious tenosynovitis may be treated by thorough lavage of the tarsal sheath, with 5 L of sterile, polyionic isotonic fluids, through large-bore catheters or needles placed in the proximal pouch and distal recess of the sheath.9,15 Lavage may be carried out in the standing horse, but it is best performed with the horse under general anesthesia for accurate needle placement and use of a high-velocity, high-pressure lavage system. This technique is less useful if purulent material, adhesions, or bony lesions are present. These horses are best treated by tenoscopic lavage and debridement.13 All debris and hypertrophic synovium, frayed areas on the lateral digital flexor tendon, and lesions on the sustentaculum tali (Figure 76-7) are debrided, preferably using motorized equipment, and bone fragments are removed. Drains are rarely necessary, except with recurrent infectious tenosynovitis, but in horses with chronic lameness, leaving a 2- to 4-cm incision (the endoscopic portal) open for drainage is advisable. If a wound is present at the level of the sustentaculum tali, this may be used as an endoscopic portal and then enlarged and left to heal by second intention. Drainage can be prolonged, and primary closure and use of a closed suction drain may be preferable. Fragmentation and osteitis of the sustentaculum tali outside the sheath are best approached through a separate incision. Curettage to the level of healthy bone is performed. Damage to the long medial collateral ligament of the tarsus should be assessed. Aminoglycoside antimicrobial drugs may be inserted into the tarsal sheath at the end of surgery. The horse is treated with systemic broad-spectrum antibiotics (see Chapter 65) for at least 2 weeks postoperatively. NSAIDs are used for at least 5 days and may be continued as necessary. A pressure bandage is applied from foot to midcrus and changed every 1 to 3 days, depending on the amount of exudate produced. The horse should be rested in a box until the wound has healed and then walked out in hand for 2 to 3 weeks before being turned out in a small paddock.

Fig. 76-7 Tenoscopic view of the tarsal sheath at the level of the sustentaculum tali (Sust). A small erosion in the fibrocartilage (plain arrow), surrounded by fibrinous pannus (dotted arrow), is secondary to subacute infectious tenosynovitis. LDFT, Lateral digital flexor tendon.

In horses with chronic infectious tenosynovitis with substantial damage to the fibrocartilaginous groove on the sustentaculum tali or to the lateral digital flexor tendon, open surgery was advocated.6,8 The tarsal sheath is approached through a desmotomy (longitudinal transection) of the flexor retinaculum to debride all the lesions, followed by the application of a fenestrated drain and repeated lavages for several days. The retinaculum is left unsutured to relieve pressure, and the skin is closed over it.6 A tenectomy of the damaged lateral digital flexor tendon within the sheath was performed in one horse unresponsive to this approach. However, this was associated with clinically significant complications from poor healing of the wound. In another horse, midmetatarsal tenotomy of the DDFT was carried out, with a heel extension shoe applied to prevent digital hyperextension. This decreased the lameness, presumably by decreasing shearing of the lateral digital flexor tendon on the roughened sustentaculum tali. In my opinion, most horses respond to tenoscopic treatment. More aggressive techniques should be reserved for horses that are unresponsive or those with severe damage to the tendon.

Prognosis

The prognosis is good in horses with idiopathic thoroughpin,8,9,16 although some horses may have persistent, nonpainful distention of the tarsal sheath. In these horses surgery to imbricate the stretched synovial sheath has been advocated,9 but recurrence is common. The prognosis is fair in horses with acute tenosynovitis treated medically8,9 and in horses with chip fractures of the sustentaculum tali treated by tenoscopy.13 In chronic traumatic tenosynovitis, some horses may respond to a single injection of corticosteroids,3 but most have recurrent distention and lameness caused by adhesion formation and peritenovaginal fibrosis. These may respond well to tenoscopic treatment,13 but a guarded prognosis should be given if lameness is a prominent feature. In horses with infection the prognosis is fair with prompt drainage and curettage, but poor in horses with severe tendon lesions or extensive damage to the sustentaculum tali.2,4,9 A fair prognosis was reported with aggressive surgical debridement in horses with osteitis/osteomyelitis of the sustentaculum tali, even if chronic.20