Chapter 80Other Soft Tissue Injuries

Rupture of the Fibularis (Peroneus) Tertius

Anatomy

The fibularis (peroneus) tertius is an entirely tendonous muscle that lies between the long digital extensor and the cranialis tibialis muscles, which cover the craniolateral aspect of the tibia. The fibularis tertius originates from the extensor fossa of the femur. Distally the fibularis tertius divides into branches that enfold the tendon of insertion of the tibialis cranialis and insert on the dorsoproximal aspect of the third metatarsal bone, the calcaneus, and the third and fourth tarsal bones. The tendon is an important part of the reciprocal apparatus of the hindlimb, which coordinates flexion of the stifle and hock.

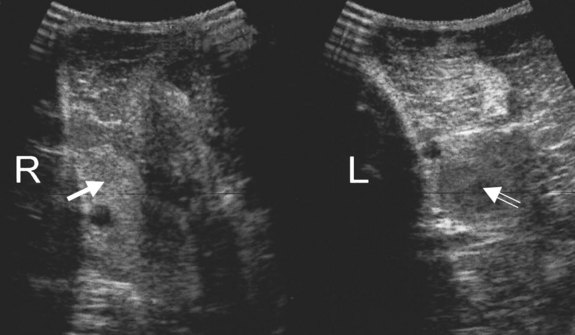

The fibularis tertius is the most echogenic structure on the craniolateral aspect of the crus and is identified readily by ultrasonography as a well-demarcated hyperechogenic structure relative to the surrounding muscles (Figure 80-1).

Fig. 80-1 Transverse ultrasonographic images of the craniolateral aspect of the midcrus of 7-year-old horse with left hindlimb lameness of 2 months’ duration. The fibularis tertius is the most echogenic structure in the center of the image of the right (R) hindlimb (solid arrow). Compare this with the image of the left (L) hindlimb, in which the fibularis tertius is markedly hypoechoic (open arrow). Note also that the overlying muscle is increased in echogenicity compared with the right hindlimb.

History and Clinical Signs

Rupture of the fibularis tertius invariably is caused by trauma resulting in hyperextension of the limb; for example, a horse trying to jump out of a stable and getting one hindlimb caught on the top of the stable door. This usually results in rupture of the tendon in the middle of the crus but occasionally farther distally. Alternatively, rupture may be caused by a laceration on the dorsal aspect of the tarsus, resulting in transection of the tendon. Occasionally, partial tearing of the tendon occurs, usually at the level of the tarsocrural joint, with prominent swelling. Occasionally the reciprocal apparatus is partially but not totally disrupted. Avulsion injuries of the origin of the tendon rarely occur in young foals. ![]() Injury close to the origin is unusual in mature horses, occurring in two of 25 adult horses with fibularis tertius injury.1

Injury close to the origin is unusual in mature horses, occurring in two of 25 adult horses with fibularis tertius injury.1

The clinical signs are pathognomonic, because rupture of this tendon allows the hock to extend while the stifle is flexed. When standing at rest, the horse may appear clinically normal, although with acute injury careful palpation may reveal some muscle swelling on the craniolateral aspect of the crus or farther distally. When the horse walks, it should be viewed carefully from behind and from the side. The hock may extend more than usual. The tendons of gastrocnemius and the superficial digital flexor muscles may appear unusually flaccid, and a dimple is seen on the caudal aspect of the crus about one handbreadth proximal to the tuber calcanei. At the trot the horse appears severely lame, with apparent delayed protraction of the limb because of overextension of the hock.

If the limb is picked up and pulled backward, the hock can be extended gradually and “clunks” into complete extension while the stifle remains flexed. A characteristic dimple appears in the contour of the caudal distal aspect of the crus (Figure 80-2). If rupture is only partial, or if lameness is chronic and some repair has taken place, clinical signs may be less severe and the diagnosis less obvious.

Fig. 80-2 A horse with rupture of the fibularis tertius. The hock can be extended while the stifle is flexed. Note also the characteristic dimple in the contour of the caudodistal aspect of the crus. Clinical signs developed after the horse had attempted to jump out of its stable and had got hung up on the door. The horse made a complete recovery.

Presumably, strain of this tendon can occur, resulting in lameness, but I have no experience of this, and to my knowledge this condition has not been documented.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of rupture of the fibularis tertius is based on the pathognomonic clinical signs. The site of rupture can be identified with ultrasonography (see Figure 80-1). The normally echogenic structure is not clearly identifiable and may be replaced by a region that is hypoechoic relative to the surrounding muscles. In horses with chronic injuries the surrounding muscles may become hypertrophied. Usually no associated radiological abnormalities are apparent in adult horses, although avulsion fracture of the origin has been described in foals.

Treatment

Confinement to box rest for 3 months, followed by a slow resumption of work, usually results in total resolution of clinical signs. Most horses are able to return to full athletic function without recurrence of clinical signs; however, injury may recur if work is resumed prematurely. Healing should be monitored ultrasonographically. Fifteen of 21 horses (71%) retuned to full athletic function, with a mean convalescent period of 41 weeks.1 Performance horses were less likely to return to their former activity than pleasure horses. Site and cause of injury (laceration or trauma) did not influence the outcome, but the presence of other injuries adversely influenced the prognosis. Delayed recognition of the clinical signs and failure to confine the horse may result in a chronic lesion, which fails to heal satisfactorily. However, compensatory hypertrophy and/or fibrosis of surrounding muscles may permit functional recovery.1,2

Common Calcaneal Tendonitis

The common calcaneal tendon consists of components from the superficial digital flexor and gastrocnemius tendons and from the biceps femoris, soleus, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus muscles. Contributions from the last two muscles are called the axial and medial tarsal tendons. So-called “common calcaneal tendonitis” has resulted from a kick in the hock region.3 Unfortunately, the horse was not examined with ultrasonography until 5 months after injury, at which time soft tissue swelling was marked. Ultrasonographic examination revealed that the superficial digital flexor and gastrocnemius tendons appeared normal, but the axial and medial tarsal tendons were enlarged. The horse made a complete functional recovery.

Gastrocnemius Tendonitis

Tendonitis of the gastrocnemius is a relatively unusual cause of hindlimb lameness in the horse.4-6 Disruption of the gastrocnemius in neonatal foals is discussed separately.

Anatomy

The gastrocnemius muscle arises from two heads that terminate in the midcrus in a common tendon. Proximally the tendon lies caudal to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT); farther distally the tendon lies laterally and is ultimately cranial, inserting on the tuber calcanei. The SDFT and gastrocnemius tendons are separated by a bursa, the calcaneal or intertendonous bursa, that extends to the midtarsal region. A small bursa, the subgastrocnemius bursa, also lies cranial to the insertion of the gastrocnemius tendon on the tuber calcanei. A communication usually exists between these bursae. The intertendonous bursa also communicates with a subcutaneous bursa in approximately 37% of horses.

The tendon of the gastrocnemius may still contain some muscular tissue as far distally as the level at which it lies lateral to the SDFT. This results in hypoechoic regions within the tendon.

Gastrocnemius tendonitis usually occurs distally, distal to the musculotendonous junction. Rarely, damage occurs at the musculotendonous junction.7 Occasionally, injuries occur at the origin of the gastrocnemius on the distal caudal aspect of the femur.8

History and Clinical Signs

Lameness may be acute or gradual in onset and varies from mild to severe. Distention of the subgastrocnemius and calcaneal bursae frequently is associated with gastrocnemius tendonitis, and the horse often develops a capped-hock appearance because of distention of the subcutaneous bursa (Figure 80-3). However, these swellings can occur without lameness or detectable pathological conditions of the gastrocnemius or SDFT (see page 799). Mild enlargement of the gastrocnemius tendon may occur, but this can be difficult to appreciate. Eliciting pain by palpation usually is not possible. Occasionally there are no palpable abnormalities.

Fig. 80-3 Medial view of the left hock of a 7-year-old Thoroughbred with acute-onset lameness associated with gastrocnemius tendonitis. Note the capped-hock appearance (black arrowhead) and the distention of the calcaneal bursa (white arrowhead).

Severe lameness is characterized by a reduced height of arc of foot flight, shortened cranial phase of the stride, and a tendency to hop off the caudal phase of the stride. Horses with less severe lameness have no specific gait characteristics. Lameness often is accentuated by proximal or distal limb flexion. ![]() Two of four horses with injury to the origin of the gastrocnemius muscle had an unusual gait characterized by internal rotation of the affected limb (outward movement of the calcaneus).8 One of the Editors (MWR) has seen a horse with gastrocnemius tendonitis exhibit a similar, unusual gait in the affected limb. Care should be taken to not overinterpret this clinical finding in sound horses, because bilaterally symmetrical internal rotation of the hindlimbs can be a normal finding. A severe injury at the origin of the gastrocnemius muscle may result in an abnormal posture, with the hock of the affected limb lower than that of the contralateral limb.

Two of four horses with injury to the origin of the gastrocnemius muscle had an unusual gait characterized by internal rotation of the affected limb (outward movement of the calcaneus).8 One of the Editors (MWR) has seen a horse with gastrocnemius tendonitis exhibit a similar, unusual gait in the affected limb. Care should be taken to not overinterpret this clinical finding in sound horses, because bilaterally symmetrical internal rotation of the hindlimbs can be a normal finding. A severe injury at the origin of the gastrocnemius muscle may result in an abnormal posture, with the hock of the affected limb lower than that of the contralateral limb.

Diagnosis

Lameness associated with gastrocnemius tendonitis is improved substantially by perineural analgesia of the tibial nerve, possibly because of local diffusion of the local anesthetic solution. Diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasonographic examination. Comparison with the contralateral limb is useful. Lesions usually occur distal to the musculotendonous junction but do not involve the insertion on the tuber calcanei.

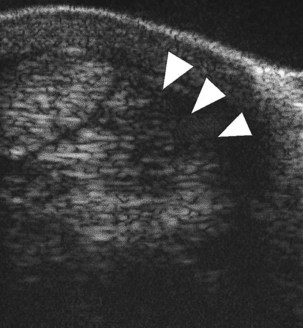

The tendon usually is damaged in the distal aspect of the crus, where it lies cranial to the SDFT. Ultrasonographic abnormalities include enlargement of the tendon, poor definition of the margins, and focal or diffuse hypoechoic or anechoic regions (Figure 80-4). Usually no detectable radiological abnormalities are apparent. In young Thoroughbred racehorses there may be increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU) in the tuber calcanei, which should prompt investigation of the gastrocnemius tendon as a potential cause of lameness. Ultrasonographic assessment of the gastrocnemius tendon is also warranted if lameness is abolished by perineural analgesia of the tibial and fibular nerves, but no potential cause of lameness is identified in the hock or proximal metatarsal regions.

Fig. 80-4 Transverse ultrasonographic image of the caudal distal aspect of the crus of a 6-year-old mare with left hindlimb lameness that was alleviated by perineural analgesia of the tibial nerve. Medial is to the left. The gastrocnemius tendon is enlarged, its caudal lateral aspect is poorly defined (arrowheads), and there is a large hypoechoic region consistent with gastrocnemius tendonitis.

Injury at the origin of the gastrocnemius muscle on the caudal aspect of the femur may be associated with IRU and, if chronic, radiological evidence of proliferative new bone formation.8

Treatment and Prognosis

Conservative treatment with box rest and controlled exercise for up to 12 months generally has resulted in progressive improvement in lameness associated with gastrocnemius tendonitis and improvement in the ultrasonographic appearance of the tendon. Horses with mild lesions have been able to return to full athletic function without recurrent lameness, but those with more severe lesions have a more guarded prognosis.5,6 Overall 14 of 25 horses managed conservatively have returned to full athletic function.9 However two horses with moderate or severe lesions that failed to respond to conservative management subsequently returned to full athletic function after intralesional treatment with β-aminopropionitrile fumarate.9 Three of four horses with injury of the origin of the gastrocnemius returned to athletic use, but recurrent injury occurred in the fourth horse.8

Disruption of the Gastrocnemius in Neonatal Foals

Disruption of gastrocnemius in neonatal foals is an unusual cause of hindlimb lameness or an inability to stand.10,11 The condition has often been associated with dystocia. Partial or complete rupture usually occurs at the proximal musculotendonous junction, resulting in soft tissue swelling over the caudodistal aspect of the femur. Injury is usually unilateral, although it is occasionally bilateral. Diagnosis is based on the stance of the foal and detection of soft tissue swelling and is confirmed by ultrasonography. Foals able to bear weight are treated by stall rest alone; a sleeve cast or splints are applied to those that are unable to load the limb. Complications include severe hemorrhage associated with the injury, leading to cardiovascular compromise (three of 28 foals, 11%); concurrent disease (17 of 28, 61%); abscess formation at the site of rupture (four of 28, 14%); and cast sores (seven of 18, 39%).11 Historically the prognosis was considered guarded,10 but in a recent report 23 (82%) of 28 foals survived to discharge from the hospital, and 13 (81%) of 16 horses that reached 2 years of age trained or raced.11

Subluxation and Luxation of the Superficial Digital Flexor Tendon from the Tuber Calcanei

Lateral (see Figure 6-29), or less commonly medial, luxation or subluxation of the SDFT from the point of the hock may occur along with damage to or rupture of the retinacular bands that insert medially and laterally on the tuber calcanei. Although usually a unilateral injury, the condition can occur bilaterally.

Lateral displacement of the SDFT occasionally occurs secondarily to hyperextension of the hind fetlock associated with progressive breakdown of the suspensory apparatus in older horses (see Figure 72-24 and page 760).

Anatomy

The SDFT lies caudally in the distal aspect of the crus and broadens to form a cap over the tuber calcanei. At this level, broad, thick retinacular bands extend medially and laterally to insert on the tuber calcanei. The calcaneal bursa is interposed between the SDFT and the tendon of gastrocnemius.

History and Clinical Signs

Partial or complete disruption of one of the retinacular bands that attach the SDFT to the tuber calcanei can result in subluxation or, more commonly, luxation of the SDFT laterally or medially. Occasionally the SDFT tendon splits sagittally, with the tendon luxating both medially and laterally. Lameness is usually sudden in onset and severe, although occasionally mild lameness precedes this, associated with soft tissue swelling in the region of the point of the hock. Frequently no history of trauma is apparent, and the injury often occurs as the horse is being worked. The horse may suddenly stop and may become extremely distressed, especially if the tendon repeatedly moves on and off the tuber calcanei. The horse may kick out repeatedly with the limb. The tendon may return to its normal position when the horse bears weight. Soft tissue swelling rapidly ensues, resulting in a capped hock appearance, making accurate palpation difficult. If the horse is kicking repeatedly when moving, one may conclude wrongly that the soft tissue swelling developed as the result of trauma caused by kicking.

With subluxation of the SDFT, the tendon is usually positioned normally at rest. Careful observation of the tendon as the horse moves may reveal instability. With luxation it may be possible to see that the SDFT has been displaced laterally or, less commonly, medially. If the tendon remains luxated, then the horse tends to be less agitated, although obviously in pain in the acute stage. Careful palpation may reveal instability of the tendon or its displacement to an abnormal position.

In horses in which lateral displacement occurs secondary to hyperextension of the fetlock, the condition may be insidious in onset and slowly progressive and unassociated with acute lameness.

Diagnosis

Ultrasonographic examination is helpful if the tendon is displaced by confirming its abnormal position, but such examination can add to confusion if the tendon is in the normal position when the horse stands still. It may be possible to identify a partial tear in the medial, or less commonly the lateral, retinacular band. The calcaneal bursa may be distended, and if the condition is chronic there may be synovial proliferation. Occasionally there is a longitudinal split in the SDFT, which adversely affects prognosis.

Treatment

In the acute stage pain relief is essential, and tranquilization may be necessary to calm the horse. If the SDFT is unstable and is moving constantly on and off the tuber calcanei, management in the acute and chronic phases may be difficult. If the tendon is permanently dislocated laterally or medially, the distress usually resolves rapidly. Antiinflammatory drugs are best avoided, because the surrounding soft tissue swelling helps stabilize the tendon. If the tendon has luxated laterally, prolonged rest (6 months) usually results in resolution of pain, although a mechanical lameness may persist. This limits the horse’s function for dressage, but these horses may be able to race or show jump at a high level. The prognosis associated with medial luxation is more guarded and tends to be associated with a greater degree of mechanical lameness.

If the SDFT is unstable initially, the tendon may with time and progressive further disruption of the attaching retinacular bands become more stable in a luxated position. Peritendonous injection of a sclerosing agent, P2G (Martindale Pharmaceuticals, Romford, Essex, England), has been helpful in stabilizing the luxated tendon in a limited number of horses.9 Surgical transection of a partially torn retinacular band has helped in chronic subluxation.9 Attempts at surgical stabilization of the SDFT in its normal position often have been disappointing, although successful results have been reported.12,13 Surgical stabilization is worth considering only if the horse is temperamentally suited to a full-limb cast. Prognosis is influenced by the ease of reconstruction of the torn retinaculum, which depends on the site of the tear (close to the tendon, close to the bone, or midway) and its age.

Infection of the Common Digital Extensor Tendon

Infection of the common digital extensor tendon and its sheath is usually the result of a puncture wound with or without deposition of a foreign body such as a blackthorn. It results in swelling, heat, pain, and lameness (see also page 789). Successful management was described by complete resection of the infected tendon.14