Chapter 122Lameness in the American Saddlebred and Other Trotting Breeds with Collection

Description of the Sport

The American Saddlebred, Morgan, Hackney Pony, National Show Horse, and Arabian (see Chapter 123) show horses are described as trotting breeds with collection. Lameness in disciplines such as dressage, road horses, and road ponies is similar. The American Saddlebred and National Show Horse have five gaits: walk, trot, canter, slow gait, and rack. The slow gait and rack are manmade gaits. These horses also perform in three gaited classes (walk, trot, and canter), fine harness classes, pleasure driving, pleasure-gaited classes, and equitation. Morgan and Arabian horses are shown similarly, but without the slow gait or rack. Hackney ponies are shown in harness, pleasure driving, and road pony classes. Show classes are further divided for professional, amateur, and juvenile riders. Equitation, hunt seat, Western, and numerous young horse and in-hand halter classes are available.

In road horse classes, Standardbreds, Morgans, American Saddlebreds, or Standardbred-cross horses are shown at the walk, trot, and road gait pulling a bike similar to a sulky used for Standardbred racehorses. These horses usually are more animated in gait than Standardbred racehorses and go both ways around the ring when performing. The road gait is a high-speed performance gait.

To understand lameness in a gaited show horse, the veterinarian must first understand the difference in locomotion between running and gaited horse disciplines. Concussion (impact) is a part of every gait. How a horse distributes concussion is related directly to athletic ability and the longevity of the horse’s career. Better equine athletes are more efficient in the distribution of concussion through the limbs and body. A superior equine athlete appears capable of using energy of concussion efficiently and distributing it for dispersion and recovery. Normally kinetic or stored energy from proper distribution of concussion causes recoil of the tissues receiving the energy of concussion. Tissue injury results in an inability to disperse concussive energy properly. Maintaining healthy hoof wall, bone, cartilage, tendons, ligaments, and muscles in a good conditioning and gait management program is essential. A veterinarian must be familiar with the gaits, because gait analysis is an important part of evaluating poor performance and subtle lameness. Many times a veterinarian may be dealing with a gait abnormality caused by the bit, saddle fit, or faulty shoeing rather than lameness.

Gaits of show horses are complex and must be synchronous to maintain distribution of concussion. Synchrony must be achieved in up to five gaits and is altered by the different gait specifications. Unlike most other horses the normal load distribution between forelimbs and hindlimbs in a show horse is about 35% and 65%, respectively (see Chapter 2). A show horse does not have to perform at racing speed. Synchrony of concussion and weight distribution are totally different compared with many sports horses, and because much concussion is dispersed through the hindlimbs, hindlimb lameness is more prevalent. In some other sports horses the head and neck are raised and lowered with the stride, a movement that assists in balance, energy distribution, and propulsion. A show horse, like a dressage horse, maintains a fixed and flexed head and neck carriage. This further shifts the balance and energy of concussion to the hindlimbs.

Show horses carry more body weight for a fleshier look than the greyhound-like racing counterparts. Riders of show horses, as a rule, also are heavier than racing jockeys.

Longevity of show horses compared with racehorses is related directly to speed of performance, which is dramatically less. Racehorses must change energy distribution at high speed quickly, potentially leading to catastrophic breakdown, but such actions and injuries in show horses are rare. A show horse often can remain competitive into the late teens and early twenties, but chronic wear and tear may result in lameness.

Although show horses do not perform at speed, high head carriage and high limb action and motion are strenuous. Show horses perform numerous gait changes and transitions going in both directions of the ring, and for a high-level (stake class) five-gaited class to last from 30 to 40 minutes is not unusual.

Because five-gaited movements and transitions are complex and arduous, compensatory lameness is common. A methodical approach to lameness diagnosis must be used to differentiate primary and compensatory lameness. A superior show horse distinctly separates its different gait movements, raising each carpus above the horizontal, with a high hock action. The horse drives off its hindlimbs with a flexed high head and neck carriage. Responsiveness to the bit, with an alert expression and attitude, and forward placement of the ears are desirable. Just as racehorses are bred for speed, show horses are bred for animated motion.

American Saddlebred

The American Saddlebred has a long history and aptitude for different gaits and is derived from many different lineages. The breed was developed in a young country where the best horses could be bred to the best. The American Saddlebred was developed as a horse of usefulness and beauty that could work in the field, pull a buggy or carriage, and have gaits that were smooth for travel under saddle.

The ability of the American Saddlebred to perform lateral gaits (slow gait and rack) came from the Narragansett pacers, which were among the earliest known easy-riding pacers. The Narragansett pacers were derived from French Canadian pacers of Arabian and Andalusian descent that were bred 100 to 200 years before the American Revolutionary War and had a comfortable saddle gait. Early settlers brought these horses, known as saddlers, to Kentucky. During the late 1830s and 1840s, many of these easy-riding saddlers were bred to the Thoroughbred foundation sires Denmark and Montrose. These crossbreeds were then bred to horses of trotting blood, from which the Standardbred breed was developed. Offspring of these crosses became favorite mounts of cavalry during the Civil War because they had an easy gait, versatility, and an ability to withstand the pressures of war. On April 7, 1891, the American Saddlebred Breeders Association was founded in Louisville, Kentucky, and became the first all-American breed registry. In recent years the American Saddlebred has gained popularity in South Africa and has been crossed with European Warmblood and carriage bloodlines (e.g., Dutch Carriage Horse). During the 1980s, the National Show Horse was derived from American Saddlebred and Arabian lineage.

The American Saddlebred ranges in height from 152 to 178 cm (15 to 17.2 hands; average 160 cm [15.3 hands]) and varies in weight from 455 to 545 kg. Colors include chestnut, bay, black, gray, golden (palomino), and spotted (chestnut, black, or bay mixed with white). As described in Modern Breeds of Livestock1:

[The] American Saddlebred has a strikingly long neck and considerable arch to the neck. The American Saddlebred is refined in appearance; has long, sloping pasterns that give spring to the stride; has a long, level croup; is strong and short-coupled; and has a back with high, well-defined withers above the level of the hips. The American Saddlebred is famous for refinement, smoothness, proportion, and a beautiful and handsome presentation and projects an alert, curious, expressive personality.

There are shows for American Saddlebreds throughout the United States and South Africa. The World Championship Horse Show is held each year in Louisville, Kentucky. Shows are run under the guidelines of USA Equestrian, which establishes rules, regulations, and drug-testing procedures. A veterinarian must be aware of current drug and medication rules, and failure to do so may result in fines and penalties to the horse, owner, and trainer.

Saddlebred Gaits

The five gaits of the American Saddlebred and other gaited horses are as follows2:

Lameness Examination

The history of lameness and poor performance must be discussed with the trainer and rider to seek their perception. This should include noting any problems with the bridle and the way a horse pulls on the bit and bridle. Show horses with hindlimb lameness often fight the bit and try to lower the head, an observation known as diving in the bit. Horses that become one-sided in the bit may have contralateral hindlimb or ipsilateral forelimb lameness. Faulty bit and bridle placement may cause gait abnormalities, particularly of the hindlimbs. Keeping the head up and fixed in position in a horse that dives in the bit is difficult. A horse with forelimb lameness is more likely to raise up out of the bridle. A horse cannot produce a gait properly or do proper gait transitions when being pushed into an uncomfortable bridle or if the rider is using the bit improperly. It is important to determine if the rider is using the bit to balance the horse or himself or herself. A rider using the bit poorly can induce a gait abnormality. Bit and bridle responsiveness is often a wild card that must be played during examination of a show horse for gait abnormalities and lameness.

Problems with a particular gait may indicate the source of lameness. Back pain is seen in horses that have difficulty in the canter, a condition known as being broke in the middle. This occurs with asynchronous movement of the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Broke in the middle also can be caused by stifle pain that causes a reduction in the cranial phase of the stride. Most commonly, however, broke in the middle is caused by stringhalt. Stringhalt prevents the limb from moving forward at a time when the forelimbs are required to go faster, causing a mismatch in synchronization between the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Distal hock joint pain and back pain can cause a hitching motion of the hindlimbs, jerking the lame limb caudally and leaving the hocks behind the motion.

Examination first begins in a stall before the horse is worked. Careful palpation with emphasis on the tendons, ligaments, joint capsules, and bulbs of the heels should be performed. Palpation of the back and gluteal muscles before working is important, because the horse can warm out of soreness in these areas. Digital pulse amplitudes should be assessed.

The horse should be evaluated during movement under tack. Harness horses, road horses, and ponies should be examined while working with and without the overcheck (checked up and without the check). Five- and three-gaited horses should be examined performing each gait going in both directions. Often horses are lame only while going in one direction or only in the turns. Horses with lameness from the hock distally are often worse with the lame limb on the inside, whereas those with pain located more proximally are lame with the lame limb on the outside of the turn. Forelimb lameness is usually worse with the affected limb on the inside.

In most show horses flexion tests can be performed with a rider or in harness. The horse’s temperament may make this difficult, but I find that the horse being ridden or jogged in a cart after flexion is helpful.

Diagnostic Analgesia

Diagnostic analgesia in show horses is similar to that described for other sports horses. I start distally and work proximally.

Imaging Considerations

Conventional and computed or digital radiography are used extensively. Scintigraphy is most useful in horses with complex lameness, because primary and compensatory issues are difficult to differentiate. The solar scintigraphic image is mandatory to evaluate horses with palmar foot pain in which radiographs are negative, and may reveal evidence of abnormal modeling of either the navicular bone or the distal phalanx. Areas of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the distal phalanx may indicate excessive pressure that can be relieved by corrective shoeing. Thermography is of value in diagnosing tendonitis, sole pressure, muscle inflammation, and suspensory desmitis. Ultrasonographic examination is useful to confirm and assess damaged soft tissues and healing. Diagnostic arthroscopy is used occasionally.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has added hugely to the ability to diagnose and differentiate difficult lameness problems. Evaluation of the soft tissues, ligaments, and tendons of the feet, fetlocks, hocks, carpus, and stifles has created a quantum leap in the ability to diagnose bone, cartilage, and soft tissue injury.

Shoeing Gaited Horses

Shoeing gaited horses to assist with motion and gait transitions is an art form in itself. In general a long toe and high heel in front help to delay breakover and cause high knee action. In the past, weighted shoes and lead weights screwed into the bottom of shoe pads were used to induce animation. In recent years a transition to “lighter is better” has occurred, and now the focus is on fitness and training techniques to teach a horse to elevate its limbs to achieve animation. Shoeing depends to a great extent on a horse’s ability, conformation, and desired gait performance (e.g., five-gaited, three-gaited, or harness). For example, a three-gaited horse may have a long foot with long toe and heel length to delay breakover in the forefeet and hindfeet. This gives the extreme highly animated knee and hock action expected from a top three-gaited horse. In contrast, in a five-gaited horse a lower hind heel angle is used to assist with a longer hindlimb stride needed for the slow gait and rack. Compared with three-gaited horses, lighter and shorter front feet are maintained in five-gaited horses to promote speed at the trot and rack.

Shoeing with high heels and long toes, with or without pads, predisposes the American Saddlebred to a contracted heel, sheared heel, and quarter cracks. The recent use of cushion polymer compounds to maintain frog pressure is helpful, because frog pressure is lost with high heels and pads. Cushioned polymers placed in the collateral sulci (grooves) of the heel and over an atrophied frog have dramatically reduced hoof problems. Medial-to-lateral hoof balance is paramount.

Ten Most Common Lameness Conditions

The 10 most common lameness conditions in show horses are the following:

Specific Lameness Conditions

Distal Hock Joint Pain and Distal Tarsitis

There are two types of show horses: those that have distal hock joint pain and those that are getting it. Show horses with distal hock joint pain typically jerk the hindlimb caudally (hitching) and leave the hocks behind in motion. Many horses stab the toe, rather than landing normally with the heel first.

Distal hock joint pain without radiological abnormality is common in 2- and early 3-year-olds just starting to rack. As training and showing proceed, radiological evidence of osteoarthritis (OA), such as loss of joint space and periarticular osteophytes, can become apparent as early as 5 years of age and may be severe by 12 years of age.

The tarsometatarsal joint is by far the most valuable point of intraarticular injection in show horses. Occasionally, injection of the centrodistal (distal intertarsal) joint also is required. I prefer to use hyaluronan and a low-dose corticosteroid combination and recommend oral supplementation with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate–containing products. Magnetic therapy appears beneficial in horses with early onset of pathology. Horses with lameness that does not improve are considered candidates for shock wave therapy and/or treatment with interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP). Arthrodesis of the distal hock joints, using a drilling technique combined with laser ablation, is recommended in horses with severe pain or evidence of osteonecrosis of the distal tarsal bones detected radiologically or possibly earlier using MRI.

Although cunean tenectomy was once widely used, effects of the procedure are short-lived, and I do not recommend it. If a horse is hitching through the turns of a show ring, a 45° flat outside trailer is used on the hind shoe for support. The shoe is set back, and the toe is squared or rolled to improve breakover.

Gluteal Myositis and Back Pain

Show horses are prone to gluteal myositis and back pain, which are often secondary to primary distal hock joint pain. A willing horse hyperflexes its back to compensate for lower hindlimb pain. The middle gluteal muscle passes over the greater trochanter of the femur and the trochanteric bursa. Gluteal myositis and tendonitis are common sequelae to distal limb pain, but they can cause primary lameness. Trochanteric bursitis (whorl bone disease) can accompany gluteal myositis.

In horses with subacute gluteal myositis, upper limb flexion may stretch the gluteal muscles and produce a transient improvement in gait. Transient improvement may be seen by gently massaging the greater trochanter and gluteal muscles. However, in horses with chronic myositis with involvement of the trochanteric bursa, deep massage and pressure may make lameness worse. Horses with subacute primary gluteal myositis commonly have a tightrope trot (plaiting). Plaiting is associated with distraction and rotation of the hindlimb, with subsequent lateral movement of the hip, motion that may cause gluteal muscle strain. Horses that plait usually have base-narrow conformation, and corrective trimming in the form of spreading the stance (lowering the outside hoof walls) may help.

Back pain is identified easily using digital pressure along the thoracolumbar region, abaxial to the spinous processes. Many horses are in so much pain that one can almost put them on the ground with digital pressure. Diagnostic analgesia usually is not necessary. However, small amounts of local anesthetic solution injected at numerous sites along the affected muscles may give enough relief to allow evaluation for lameness that has been hidden by back or gluteal pain.

Management of horses with gluteal myositis and back pain requires a multifaceted approach, including local injection of Sarapin and corticosteroids. In most horses nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), methocarbamol, electrical stimulation, magnetic therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, and anticoncussion saddle pads are used in various combinations. Exercise regimens using stretching and flexing during the warm-up period are also beneficial. Acupuncture and chiropractic modalities often are used and can be of benefit if performed by skilled practitioners. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), with or without intramuscular injection of a combination of Sarapin, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and a low dose corticosteroid, is effective for immediate relief. Diagnosis and treatment of primary lameness problems, if present, are of utmost importance.

Palmar Foot Pain

Because show horses are shod intentionally with a high heel and long toe to produce high motion, they are prone to a contracted and/or sheared heel. Full or wedge pads are often applied to achieve the desired motion, and the lack of frog pressure can cause atrophy of the soft tissues of the heel. Without proper frog support, the bulbs of the heel contract and a sheared heel often develops. As the heel contracts or a sheared heel develops, more stress is applied to the quarters, predisposing the hooves to quarter cracks. Differentiation of causes of palmar foot pain is critical but difficult, because palmar digital analgesia affects these conditions and navicular syndrome similarly.

Recently more concern has arisen about maintaining frog pressure. Soft, acrylic polymers are now used for frog support in horses with frog atrophy. Turnout for several months, during which the horse is barefoot, may help. Expansion springs can be used to assist in reestablishing proper heel conformation. Severe quarter cracks are repaired using a lacing technique, applying screw compression plates, or nailing. Floating the heel bulb and quarter located under the crack is important to reduce weight bearing, allowing showing to continue.

Navicular disease is not uncommon, but in horses without abnormal radiological findings the diagnosis should be confirmed using scintigraphy. The aforementioned conditions of the hoof capsule and supporting soft tissues are much more common.

Treatment of soft tissue causes of palmar foot pain involves maintaining comfort while proper anatomy is reestablished. Corrective shoeing, NSAIDs, and long-term foot blocks often are used. If navicular disease is confirmed, intraarticular treatment of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint using hyaluronan and corticosteroids is recommended. Drugs aimed at improving peripheral perfusion or decreasing intraosseous pressure such as isoxsuprine may be useful with NSAIDs, long-term foot blocks, and corrective shoeing. ESWT appears promising in managing palmar foot pain.

MRI has been particularly beneficial for differentiating navicular disease, navicular bone cystic disease, deep digital flexor (DDF) tendonitis (see Chapter 32), adhesions of the DDF tendon (DDFT), distal sesamoidean impar desmitis, cartilage defects of the DIP joint, disruptions of the laminae and hoof capsule, and hemorrhage or abscessation of the structures of the foot. Blood flow studies using MRI contrast techniques are invaluable for evaluation of circulatory disturbances of the foot.

Osteitis of the Distal Phalanx

In horses with high stepping gaits the distal phalanx is prone to injury. Trauma to the solar margin such as bruising and fracture occurs. A careful evaluation for improper sole pressure or medial-to-lateral hoof imbalance should be performed. Well-exposed and well-positioned radiographs are essential. Digital venography may reveal compression of blood vessels within the hoof capsule and is useful to pinpoint a location of trauma.

Fractures of the distal phalanx are rare. Solar scintigraphic images are useful to diagnose fractures and other areas of distal phalangeal trauma and can help to formulate a corrective shoeing plan. Thermography may be useful for diagnosis of distal phalanx trauma.

For horses without distal phalangeal fracture, management includes corrective balancing and shoeing to relieve improper sole pressure and to provide support, NSAIDs, and isoxsuprine. If effusion of the DIP joint is present, intraarticular treatment with hyaluronan and corticosteroids, or IRAP is beneficial.

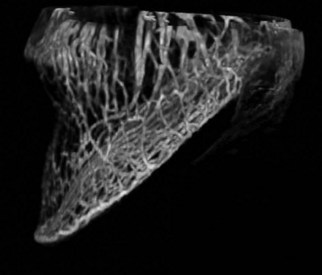

MRI of the distal phalanx may identify evidence of bone contusions. MRI blood flow contrast studies are more accurate than standing venograms and a computerized three-dimensional rotation can be accomplished with soft tissue and bone subtraction (Figure 122-1).

Osteoarthritis and Osteochondrosis of the Tarsocrural Joint

Lameness of the tarsocrural joint is not as common as distal hock joint pain. Osteochondrosis of the tarsocrural joint in show horses is similar to that described for other sports horses. The most common location is the cranial aspect of the intermediate ridge of the tibia. Although show horses with osteochondrosis lesions may compete successfully without surgical intervention, effusion and capsulitis are indications that surgery should be performed. Prognosis after arthroscopic surgery is favorable. However, prognosis for show horses with osteochondrosis lesions of the trochlear ridges of the talus is guarded. Osteophytes and small fragments of the distal aspect of the medial trochlear ridge are not a major source of lameness.

The diagnosis of OA of the tarsocrural joint is derived from the results of physical examination, flexion tests, diagnostic analgesia, radiography, nuclear scintigraphy, and MRI. Horses with early OA of the tarsocrural joint are managed with intraarticular injections of hyaluronan, with or without corticosteroids. Oral supplementation with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate–containing compounds appears beneficial. Intramuscular and intravenous administration of polysulfated glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronan, respectively, are helpful. NSAIDs may be necessary. Horses with chronically distended tarsocrural joints (so-called boggy hocks) usually respond well to routine intraarticular medications, but if they are refractory, I add 0.5 mL atropine sulfate. IRAP appears effective for management of horses with chronic capsulitis and OA of the tarsocrural joint.

MRI of the tarsocrural joint and distal aspect of the tibia has permitted identification of soft tissue damage, tibial stress fractures, and bone cysts communicating with the tarsocrural joint, which may be associated with damage to the opposing cartilage and subchondral bone.

Osteoarthritis and Osteochondrosis of the Fetlock Joint

Conditions of the fetlock joint in show horses are essentially the same as seen in other sports horses. The most common conditions are osteochondral fragments of the proximal dorsal aspect of the proximal phalanx and sesamoiditis. Plantar process osteochondrosis fragments are uncommon but are recognized. During prepurchase examinations, I obtain lateromedial radiographic images of each metatarsophalangeal joint specifically to evaluate for plantar process fragments. Fractures of the proximal sesamoid bones occur infrequently. Osseous cystlike lesions of the distal aspect of the third metacarpal bone (McIII) and osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) lesions of the sagittal ridge of the McIII occur infrequently and are less devastating than in racing breeds. Mineralized proliferative synovitis lesions are often confused with osteochondral fragments, but show horses with this condition have a favorable prognosis. Primary OA of the fetlock joint is seen commonly in show horses that wing the lower limb while moving, but radiographs are often negative.

Diagnosis of lameness of the fetlock joint is routine, using radiography, nuclear scintigraphy, ultrasonography, and, when necessary, MRI. Nuclear scintigraphy is most useful in diagnosing sesamoiditis.

Arthroscopic removal of osteochondral fragments of the proximal phalanx is not always necessary, because many show horses compete well and require little maintenance therapy when fragments involve the front fetlock joints. When fragments involve the hind fetlock joints, arthroscopic removal is recommended, because these horses have gait abnormalities characterized by a skipping motion that are accentuated at the rack and slow gait. This is particularly evident in horses with plantar process fragments of the proximal phalanx.

Horses with sesamoiditis respond well to corrective shoeing (lowering the heel), NSAIDs, isoxsuprine, and injection of hyaluronan and corticosteroids into the fetlock joint. Shock wave therapy appears to be effective in managing horses with chronic sesamoiditis, collateral ligament damage, and severe arthritic changes. Treatment with IRAP with or without ESWT is beneficial in horses with severe OA.

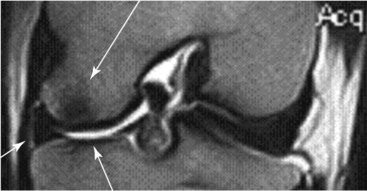

MRI may be helpful for evaluation of the articular cartilage and subchondral bone and for identification of injuries of the intersesamoidean ligament (Figure 122-2), oblique sesamoidean ligaments, straight sesamoidean ligament, palmar annular ligament, and digital flexor tendons.

Osteoarthritis and Osteochondrosis of the Stifle Joint

OA of the stifle joints is a common lameness in show horses, particularly in horses being pushed to perform at a young age. Normal weight distribution favoring the hindlimbs, coupled with learning the slow gait and rack at a young age, predispose the horses to stifle pain. Horses with stifle lameness usually have a shortened cranial phase of the stride and are said to be “humping up in the hip” at the beginning of the caudal phase of the stride. Lameness often is pronounced with the limb on the outside of the ring and is worse in the turns. Diagnosis is made using assessment of gait, diagnostic analgesia, radiography, nuclear scintigraphy, and MRI if needed. Subchondral bone cysts of the medial femoral condyle and OCD of the trochlear ridges of the femur are commonly diagnosed in young show horses with stifle effusion. Arthroscopic surgery, debridement, and fragment removal are recommended in those horses with effusion and lameness. Prognosis for a five-gaited horse with OCD of the stifle is guarded, even with surgery. Many of these horses can compete successfully in other divisions such as harness, pleasure driving, and equitation.

Distal patellar fragmentation and cartilage damage are seen in older horses, and horses respond well to intraarticular injections of hyaluronan and corticosteroids. Arthroscopic surgery is recommended in horses refractory to this therapy.

Lateral luxation of the patella occasionally is diagnosed in foals, which have a guarded prognosis. Atrophy of the trochlear groove of the femur usually occurs with this condition, which may be genetic and familial.

Upward fixation of the patella is seen in young horses with underdeveloped quadriceps muscles. Most improve with training in a jog cart to build up the hindlimb musculature in lieu of intense riding and training. Trainers must be advised to be patient. Medial patellar desmotomy should be used as a last resort and should be done only if radiographs of the stifle are negative. Horses with early OA and negative radiographs are managed by decreasing training intensity and implementing a jogging program to develop the hindlimb musculature. A weighted drag behind the cart is added later, before the normal riding program resumes. Internal blisters are used commonly. Intraarticular injection of hyaluronan and corticosteroids alleviates clinical signs, but without modification of exercise the results are short-lived.

Horses with chronic OA are maintained using intraarticular injections, oral supplements, intramuscularly and intravenously administered polysulfated glycosaminoglycans, and NSAIDs.

MRI may reveal degeneration of the meniscal cartilages in areas of contact with osseous cystlike lesions of the proximal aspect of the tibia or subchondral bone cysts in the medial femoral condyle. Identification of injury of the meniscal cartilages, meniscotibial ligaments, and cruciate ligaments is important for establishing a prognosis and formulating a management plan in show horses with stifle joint disease (Figure 122-3).

Fig. 122-3 Dorsal turbo spin echo magnetic resonance image of a stifle joint (proximal is to the top and medial is to the left) in a show horse showing an area of low signal intensity consistent with bone injury of the distal aspect of the medial femoral condyle (upper arrow) and corresponding mild injury of the proximal medial aspect of the tibia (lower arrow). The medial meniscus (left arrow) is shaped abnormally.

Suspensory Desmitis

Show horses with long pasterns and high heels are prone to suspensory desmitis because the fetlock drops excessively and stretches the suspensory ligament. Show horses trained in deep footing (sand or mud) are at increased risk for suspensory desmitis. Avulsion fracture of the McIII at the origin of the suspensory ligament may occur in association with suspensory desmitis. Suspensory desmitis is more common in forelimbs than in hindlimbs. Treatment of show horses with suspensory desmitis involves rest, NSAIDs, periligamentous injection of corticosteroids, leg sweating, magnetic therapy, and support wraps. Rest includes handwalking, because horses with suspensory desmitis appear to respond better to limited, controlled exercise than to stall rest alone. The heel should be lowered and a palmar or plantar extension applied.

ESWT has been extremely beneficial in show horses with suspensory body or suspensory branch injuries, and particularly those with proximal suspensory desmitis. Intralesional injection with IRAP or stem cells, combined with ESWT, has been most effective.

MRI may give additional information about suspensory pathology compared with ultrasonography, permitting identification of adhesions to the second or fourth metacarpal (metatarsal) bones.

Tendonitis

Performing in deep, muddy, outdoor show rings and a long-toe, high-heel hoof conformation predispose horses to tendonitis of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and DDFT and desmitis of the accessory ligament of the DDFT. As a rule tendonitis is not nearly as devastating in show horses as in racehorses.

Horses with tendonitis respond well to sweats, peritendonous injection of corticosteroids, NSAIDs, magnetic therapy, and ESWT. Rarely, show horses require tendon splitting and desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the DDFT or the accessory ligament of the SDFT. Serial ultrasonographic examinations are important to monitor healing.

Splint Exostoses

Splint exostoses are caused by lunging young horses in tight circles too fast and too long. Direct trauma from interference can cause splint exostosis or fracture. Once splints become inactive, they rarely cause lameness, unless the mineralization impinges on the suspensory ligament or if the exostosis is so large that it repeatedly becomes traumatized. Diagnosis is made by palpation and radiological assessment for fracture. Treatment consists of leg sweats, subcutaneous injections of corticosteroids over the exostosis, and ESWT in horses refractory to sweating and injections. Surgical removal of distal splint bone fracture fragments, large exostoses, or nonunions that impinge on the suspensory ligament should be performed.

Other Lameness Conditions

Stringhalt

Stringhalt is common in the show horse and needs to be differentiated from other hindlimb lameness conditions. Local anesthetic solution (5 mL at each of three sites) is injected into the lateral digital extensor muscle, and the horse is observed while ridden 10 minutes later. If gait is improved, I recommend lateral digital myotenectomy. Previous trauma to the lateral or common digital extensor tendons can predispose horses to stringhalt (see Chapter 48).

Semimembranosus or Semitendinosus Myositis

Myositis of the semimembranosus or semitendinosus sometimes can mimic stringhalt and cause bizarre gait abnormalities similar to fibrotic myopathy. Horses and ponies (particularly road ponies) show restriction of the cranial phase of the stride. The hindlimb appears to hang up in a flexed position, or the horse is short-strided. Typically a trainer says the horse cannot get underneath itself. This occurs particularly in gaited horses that cannot perform the slow gait or rack. This condition may be an early form of fibrotic myopathy.

Diagnosis involves injecting 5 mL of local anesthetic solution in three or four sites each in the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles. The horse is evaluated ridden in 10 minutes, and often the change is dramatic.

Short-lived benefit is seen by injecting the involved muscles with Sarapin and a corticosteroid and using electrotherapy. The best solution appears to be tenotomy of the medial branch of the semitendinosus muscle, the same procedure described for surgical management of horses with fibrotic myopathy.

Tibial Stress Fractures

Young show horses, particularly young, talented five-gaited prospects, can become suddenly difficult to gait. Typically the trainer says, “The horse was one of the best young prospects I ever had, and then suddenly I lost him,” or “Everything came undone.” Tibial stress fractures are the show horse counterpart to bucked shins in the Thoroughbred. Diagnosis is difficult and usually involves ruling out everything else first and proceeding to nuclear scintigraphy, the most consistent and best method of diagnosis. Horses are given 60 days of jogging and are reassessed.

Hindlimb Extensor Tenosynovitis

The long digital extensor tendon sheath at the level of the hock can become inflamed and distended, a condition that is particularly prevalent in talented gaited horses. There is usually an indentation of the distended sheath just below the hock, caused by constriction by the retinaculum. Although lameness is unusual, severe distention of the sheath may cause a stiff gait, because the horse cannot flex the hock normally. Tenosynovitis may be confused with bog spavin. If left untreated, the synovium becomes hypertrophic, and movement of synovium under constricting retinaculum causes a hitch in hindlimb gait. Treatment consists of draining synovial fluid and injecting a combination of hyaluronan, corticosteroids, and 0.5 mL of atropine sulfate. Massaging with DMSO and a corticosteroid is also beneficial.

Cervical Myositis

The degree of neck flexion required in show horses often causes pain, particularly in young horses. Older horses may develop OA of the facet joints, especially of the fifth to seventh cervical vertebrae. Diagnosis is based on radiological examination and nuclear scintigraphy. Myelography may be necessary if there is evidence of hindlimb incoordination. Horses with cervical myositis and pain often are observed to be fighting the bit. Diagnosis is made by palpation. Injection of Sarapin and corticosteroids in the affected muscles, methocarbamol, electrical stimulation, and NSAIDs are used. Acupuncture and chiropractic procedures also may be beneficial. ESWT may be beneficial in horses with OA of the facet joints. Ultrasound-guided intraarticular injection may also be of benefit.