Chapter 48Mechanical and Neurological Lameness in the Forelimbs and Hindlimbs

General Considerations

Mechanical lameness reflects altered biomechanical forces affecting limb function. The biomechanics of limb function depend on normal functioning of peripheral nerves, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Appropriate muscle contraction and relaxation are important factors in limb biomechanics. A muscle that cannot contract with sufficient force or a muscle that cannot relax and stretch can result in an altered gait. Mechanical lamenesses are typically most obvious at the walk and often become less evident or disappear at the trot. Gait alterations may not be evident at the canter, although a horse with a mechanical lameness may not be capable of generating a smooth canter and may appear to be hopping or “off” behind at the canter. Mechanical lamenesses include altered gaits caused by decreased and increased joint flexion.

The importance of proper functioning of the neuromuscular system for a normal hindlimb gait is exemplified by horses with chronic motor neuron disease and myopathy from equine polysaccharide storage myopathy (EPSSM). Both of these neuromuscular disorders can be associated with a fibrotic myopathy-type or stringhalt-type of gait. Horses with EPSSM may develop prolonged or intermittent upward fixation of the patella. Underlying myopathy was found in some but not all horses with shivers (shiverers).1,2 Neuropathy is known to be a cause of stringhalt3,4 and was found in horses with fibrotic myopathy.5 Trauma to peripheral nerves may also cause a mechanical lameness. The possible role of altered proprioceptive input to the affected limb is intriguing and is discussed under appropriate headings.

Equine protozoal myelitis or myeloencephalitis (EPM) with involvement of motor neurons causing selective denervation may also cause mechanical lameness. In horses with EPM, lameness cannot be abolished using diagnostic analgesia. Horses with lameness from EPM should, however, also exhibit proprioceptive deficits and ataxia and usually exhibit muscle atrophy. Lameness in horses with EPM may be caused by pain arising from atrophied muscles, nerve root pain, or pain originating from peripheral nerves. EPM is unlikely to cause an obvious mechanical lameness without accompanying ataxia. It is difficult to accept that EPM could cause selective damage to motor neurons sufficient to cause a mechanical lameness without also causing concurrent spinal cord white matter damage and ataxia, but it does do so occasionally, and neurological deficits may be subtle early in the disease. Careful neurological evaluation by a clinician with expertise in equine neurological evaluation is an important part of examining a horse with mechanical lameness because distinguishing between gait abnormality caused by mechanical lameness and gait abnormality caused by neurological disease may be difficult.

Electromyography and muscle biopsy may aid in determining the cause of mechanical or neurologically mediated lameness. Concentric needle electromyography of denervated muscle often reveals abnormal spontaneous activity such as positive sharp waves, fibrillations, and myotonic bursts. Abnormal spontaneous activity may also be present in muscles of horses with myopathy, but these findings are generally mild and may be absent. Biopsy of the semimembranosus or semitendinosus muscle is useful for evaluating evidence of denervation atrophy and EPSSM. However, if denervation of a single muscle or part of a muscle causes the gait alteration, sampling error may result in a false-negative result.

Mechanical lameness does not always cause pain, and horses usually do not respond to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug therapy. Methocarbamol therapy is indicated only when muscle cramping from central nervous system disease is suspected. Phenytoin therapy has proved to be useful in some horses with mechanical lameness, particularly those with stringhalt.

Mechanical lameness in the horse is the result of abnormal structure or function of the musculoskeletal system or, more commonly, of the neuromuscular system. Possibly a variety of underlying problems can result in the same type of mechanical lameness. Limb dysfunction may also be caused by an imbalance of flexor and extensor muscle activity as a result of a primary neurological cause.

Anatomical Considerations

A number of unique anatomical features in the equine hindlimb contribute to mechanical lameness. The configuration of the patellar ligaments in the stifle joint allows locking of the stifle into an extended position (see page 94). The stay apparatus minimizes the muscular effort required for a horse to stand for long periods. The reciprocal apparatus links the actions of the stifle and hock, primarily through the fibularis (peroneus) tertius and superficial digital flexor tendons, such that an abnormal action in either joint affects the action of both.

Innervation patterns to the muscles of the hindlimbs may also contribute to mechanical lameness. The semitendinosus muscle, for example, receives innervation from two different nerves: the caudal gluteal and sciatic nerves. Often more than one muscular branch innervates long muscles such as the semitendinosus and possibly the semimembranosus. Damage to one nerve or to a muscular branch can result in partial denervation of a large muscle, with resultant altered biomechanical forces leading to abnormal limb action.

Upward Fixation of the Patella (Locking Stifle) and Delayed Release of the Patella

Clinical Characteristics

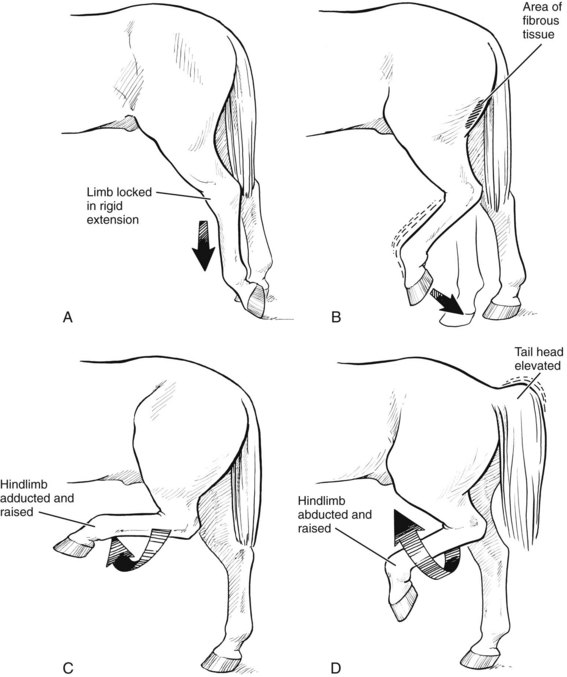

Horses and ponies with upward fixation of the patella are episodically unable to flex the stifle or the hock and drag the extended limb behind them on the toe (see Figures 5-18 and 48-1)![]() . The condition occurs most commonly after a period of standing still and tends to decrease with continued exercise. An intermittent form of patellar fixation, called delayed release of the patella, also occurs, in which the patella appears to catch briefly, sometimes followed by exaggerated flexion of the stifle and hock. Low-grade intermittent upward fixation or delayed release of the patella is relatively common, but it is often difficult to detect and is not necessarily observed daily. Affected horses have a slightly jerky movement of the patella that may be most apparent during deceleration from trot to walk and when the horse is working in deep footing, especially on turns. Affected horses may appear to be in some discomfort, may be resistant to work especially in deep footing, and can become irritable. Both upward fixation of the patella and delayed release may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Fifty-five of 78 horses (70.5%) with upward fixation of the patella were affected unilaterally and 23 (29.5%) bilaterally.6

. The condition occurs most commonly after a period of standing still and tends to decrease with continued exercise. An intermittent form of patellar fixation, called delayed release of the patella, also occurs, in which the patella appears to catch briefly, sometimes followed by exaggerated flexion of the stifle and hock. Low-grade intermittent upward fixation or delayed release of the patella is relatively common, but it is often difficult to detect and is not necessarily observed daily. Affected horses have a slightly jerky movement of the patella that may be most apparent during deceleration from trot to walk and when the horse is working in deep footing, especially on turns. Affected horses may appear to be in some discomfort, may be resistant to work especially in deep footing, and can become irritable. Both upward fixation of the patella and delayed release may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Fifty-five of 78 horses (70.5%) with upward fixation of the patella were affected unilaterally and 23 (29.5%) bilaterally.6

Fig. 48-1 Diagrammatic representation of the common mechanical hindlimb gait abnormalities. A, In horses with upward fixation of the patella, the hindlimb is periodically held in rigid extension. The fetlock joint is flexed, and the horse walks on the toe. Horses with intermittent upward fixation can have a gait similar to shivers (see D). B, Horses with fibrotic myopathy show slapping of the affected hindlimb downward just before the end of the cranial phase of every walk stride. Hock flexion is near normal, but fibrous tissue in the caudal thigh region limits the cranial phase of the stride. C, Horses with stringhalt exaggerate flexion of the hock with the hindlimb in a normal (adducted) position. This gait occurs at every walk stride. Excessive hock flexion causes some horses to hit the ventral abdomen with the dorsum of the hindlimb. D, Horses with shivers often have abnormal tail head elevation and hold the affected hindlimb in a flexed and raised position away from the midline (abducted). This abnormal gait occurs sporadically, not at every walk step, which helps to distinguish it from stringhalt.

Warmbloods, Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds, and some pony breeds (e.g., Shetland and Miniature ponies) may be predisposed to upward fixation of the patella.6 The episodic nature of intermittent upward fixation of the patella adds to the difficulty of detecting an affected horse. Careful observation while moving the horse over from side to side, turning in small circles, or walking down an incline can be particularly useful. Clinical signs of upward fixation of the patella or delayed release of the patella are most commonly seen in young horses, especially those kept stabled, and signs may diminish or disappear if the horse becomes fitter and stronger. However, clinical signs may recur if the horse is confined to box rest for an unrelated reason. Persistent upward fixation of the patella has also been described in a foal.7

Cause

Upward fixation of the patella has been attributed to abnormal laxity and to increased tenseness of patellar ligaments. Decreased force of muscle contraction of the thigh muscles (quadriceps and biceps femoris) that move the patella out of the locked position may also cause upward fixation of the patella. This may be the explanation for upward fixation of the patella occurring in unfit horses, those in poor condition, or those with underlying myopathy, causing weak or stiff muscles. Horses and ponies with overly straight hindlimbs may be prone to upward fixation of the patella because such conformation can result in overextension of the stifle joint, leading to patellar locking.6,7 Sixteen of 78 horses (20.5%) with upward fixation of the patella had straight hindlimb conformation.6 Foot conformation may also play a role. Thirty-one of 78 horses (39.7%) had long toes and/or a higher inside wall of the hind foot of the affected limb(s).6 Permanent upward fixation of the patella occurs rarely secondary to luxation or subluxation of the ipsilateral coxofemoral joint (see Chapters 50 and 126).

Biomechanical Basis

Upward fixation of the patella is caused by failure of the medial patellar ligament to unhook from the medial ridge of the femoral trochlea, causing the stifle to lock in extension. Abnormalities of the fibrocartilage at the medial aspect of the patella also possibly make the joint prone to locking. Once the stifle is locked in extension, the hock is also fixed in extension through the action of the reciprocal apparatus. The biomechanical basis for stifle hyperflexion after the brief period of patellar catching in intermittent upward fixation of the patella (or delayed release of the patella) is not entirely clear and may be from increased force of contraction of the biceps and quadriceps muscles during the transient locking phase. Clearly, therapy for this disorder should be directed at correcting the underlying cause. Unfortunately, for many horses an exact cause is never determined.

Medical Therapy

Exercise is an important part of therapy for horses with upward fixation of the patella. Conditioning exercise, including work on hills, may result in complete resolution of the problem in some horses. Uphill work may be more beneficial than downhill exercise. Horses that respond to conditioning exercise indicate that muscle dysfunction can play an important role in the development of upward fixation of the patella. Corrective trimming and shoeing is also important; the toe should be shortened to facilitate breakover, and mediolateral imbalance should be corrected. It has been suggested that rounding the medial aspect of the foot to promote medial breakover may be beneficial together with elevation of the lateral heel using a wedge-heel shoe.6 Thirty-three of 64 (51.6%) horses with upward fixation of the patella had a successful outcome following corrective trimming and shoeing, dietary management to promote better condition, and exercise, and a further 13 (20.3%) improved.6

If underlying myopathy such as EPSSM is the cause, diet change to one that is high in fat and low in starches and sugars9 and continued exercise conditioning may be beneficial. The most effective diets are those that provide at least 20% to 25% of total daily energy from fat and less than 20% of total daily energy from starches and sugars.

Another medical therapy is administration of estrogenic compounds. The rationale is presumably that estrogens can cause tendon and ligament relaxation. Whether horses with upward fixation of the patella have overly tense patellar ligaments and whether estrogen has any effect on patellar ligaments and tendons are unclear. Estrogen effects on muscle cell metabolism and muscle tone are possible. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some horses may benefit from this type of therapy. Intramuscular injection of 1 mg of estradiol cypionate per 45 kg of body weight (i.e., 11 mg/500 kg) once weekly for 3 to 5 weeks has been recommended.

Injection of iodine-containing counterirritants into and around the medial and middle patellar ligaments has also been advocated.10 It has been proposed that maturation of a fibrous and inflammatory response may result in stiffening of the ligaments and thus relieve upward fixation of the patella.11 Injection of a 2% solution of iodine in oil or of ethanolamine oleate has been advocated. Injection of 1 to 1.25 mL of these compounds into numerous sites in and around the distal aspect of the medial and middle patellar ligaments is recommended. However, in an experimental study in normal horses, injection into the medial and middle patellar ligaments with iodine in almond oil provoked more fibroplasia and infiltration of inflammatory cells than ethanolamine.11

Surgical Therapy

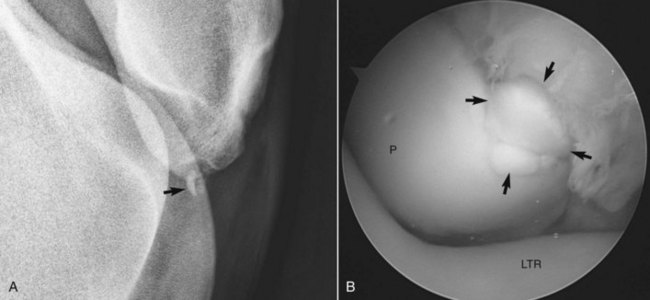

Medial patellar desmotomy may be necessary, although this should be considered only in horses with upward fixation of the patella that is unresponsive to conditioning exercise or medical therapy, or for horses that are persistently locked for several days. Because the transected ligament eventually heals with a fibrous union, the main benefit of surgery may be temporarily to alter the action of the stifle joint such that the horse is capable of conditioning exercise. Development of fragmentation of the apex of the patella (sometimes referred to as patellar chondromalacia) and associated lameness may occur after medial patellar desmotomy, although rest for 3 months postoperatively may reduce the risk (see Figure 46-4) (Figure 48-2).12 Treatment of fragmentation of the apex of the patella is by arthroscopic debridement (see Chapter 46). Middle patellar desmitis is also a potential untoward sequela.6,13 Occasionally after medial patellar desmotomy persistent lameness develops from residual desmitis, swelling and inflammation, or osteitis of the patella. One of us (MWR) has seen horses develop instability and knuckling of the hindlimb after medial patellar desmotomy. Percutaneous splitting of the medial patellar ligament may be equally effective, with less potential for secondary fragmentation of the apex of the patella.14,15 Twenty-three horses were treated by ligament splitting without complication,15 whereas eight of 18 horses (45%) treated by desmotomy had secondary stifle-related lameness, despite many being rested for 3 months postoperatively.6 A modification of the originally described technique for medial patellar splitting (desmoplasty) can be equally effective.16,17 Briefly, in a standing horse after sedation and the injection of local anesthetic solution subcutaneously over the involved medial patellar ligament(s), a 14-gauge, 4-cm-long needle is used to perform desmoplasty. The needle is inserted through skin at three locations (proximal, midligament, distal), and four to nine desmoplasty incisions, in roughly a cranial-to-caudal direction, are made in a fan-shaped fashion.16,17 One of us (MWR) has used 12 to 15 deep incisions, and although I was initially skeptical of efficacy, I have been impressed with resolution of clinical signs soon after the procedure, even in horses that are almost persistently locked. Horses are maintained on phenylbutazone, and the femoropatellar joint is medicated with hyaluronan and short-acting corticosteroids.

Fig. 48-2 A, Lateromedial digital radiographic image (cranial is the right and proximal is uppermost) of the right stifle joint in a 7-year-old Warmblood gelding with bilateral hindlimb lameness. This horse had instability of the hindlimb characterized by knuckling after bilateral medial patellar desmotomy and the subsequent development of distal patellar fragmentation, bilaterally (arrow). B, Intraoperative arthroscopic photograph (lateral is to the right and proximal is uppermost) showing fragmentation (arrows) of the distal aspect of the left patella (P). The underlying lateral trochlear ridge (LTR) of the distal femur can be seen. The fragments were removed from both stifle joints.

Identification of a chronically thickened medial patellar ligament at a clinical examination for an unrelated reason (e.g., a prepurchase examination) usually reflects previous medial patellar desmotomy or splitting.

Fibrotic Myopathy

Clinical Characteristics

The gait of fibrotic myopathy is characterized by a shortened cranial swing phase of the affected hindlimb while walking, with an abrupt catching of the forward swing, a slight caudal swing, and slapping of the hoof onto the ground (see Figure 48-1). This abnormal gait is present at every walk stride and has a characteristic sound, but it is often much less apparent at the trot and canter. However, an affected horse appears lame at the trot. The degree of gait impairment varies according to the severity and extent of muscle pathology. Affected horses may have a palpable thickening on the caudal aspect of the crus, which may extend distally and medially toward the tuber calcanei, but this is not a consistent finding. Osseous metaplasia may accompany fibrosis in some horses. Affected muscles may exhibit some degree of atrophy. Some horses have an obvious dimple, scar, or depression in the affected muscle. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the caudal thigh musculature can be useful18 and may detect focal hyperechogenic areas of fibrosis when none are palpable or hyperechogenic areas with underlying acoustic shadowing associated with mineralization. The proximodistal extent of muscle abnormality can be determined.

Fibrotic myopathy may be more common in Western performance horses and gaited horses. Fibrotic myopathy is most often a unilateral problem but can occur bilaterally. Fibrotic myopathy may occur first in one hindlimb, followed by development of a similar abnormal gait in the other hindlimb months to years later. This gait abnormality does not appear to be painful or distressing to the horse, and signs do not increase from anxiety or decreased ambient temperature. Fibrotic myopathy occurs most often in adult horses but has also been described in neonates. Fibrotic myopathy in foals is not associated with palpable fibrosis of the distal aspect of semitendinosus muscle. Diagnosis is made by recognition of the typical gait abnormality. Occasionally injection of local anesthetic solution into the involved muscle bellies may partially alleviate clinical signs (see Chapter 122).

Cause

Fibrotic myopathy is usually the result of trauma of the semitendinosus muscle during activities that result in extreme tension, such as sliding stops in reining horses and struggling from catching a leg in a halter or tether. Traumatic injuries to the semitendinosus, or inflammatory processes such as abscesses at injection sites, can cause fibrotic myopathy. Less commonly, damage to the semimembranosus or gracilis muscle (see Chapter 47) is a cause.19 Fibrotic myopathy present at birth has been speculated to be caused by trauma at or soon after birth.20 Adhesions between the semitendinosus and the semimembranosus or biceps femoris muscles causing restriction of muscle action have been proposed.21 Careful study of a small series of horses with fibrotic myopathy found that underlying traumatic or degenerative neuropathy causing denervation of the distal semitendinosus muscle can result in fibrotic myopathy.5 Two horses with minimal fibrosis had bilateral fibrotic myopathy from degenerative neuropathy of unknown cause. One horse had unilateral fibrotic myopathy caused by nerve damage after fracture and scarring of the caudal aspect of the greater trochanter. This horse had characteristic fibrosis of the distal aspect of semitendinosus muscle. Underlying neuropathy is the most likely cause in horses in which fibrotic myopathy develops in one hindlimb and progresses to involve the other hindlimb.

Biomechanical Basis

Functional shortening caused by muscle scarring, adhesions to adjacent muscles, or denervation results in increased muscle tension that does not allow full extension of the stifle, and secondarily the hock, during the cranial swing phase.

Medical Therapy

No medical therapy has been shown to be consistently useful in treating fibrotic myopathy. In horses with complex muscle injury, such as those that develop fibrotic myopathy after lacerations or other traumatic injuries that involve not only the semitendinosus but the nearby semimembranosus muscle, corticosteroid injections into the fibrotic scars and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory therapy may partially alleviate clinical signs. Short-term improvement is reported in gaited horses with early fibrotic myopathy after injection of antiinflammatory drugs into involved muscles (see Chapter 122). Exercise does not appear to alleviate or exacerbate the abnormal gait.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical resection of the affected distal semitendinosus muscle (semitendinosus myotomy)22 or affected muscle and tendon of insertion (semitendinosus myotenectomy)19,21 and semitendinosus tenectomy at the tibial and tuber calcaneal insertions20 have all resulted in some degree of immediate gait improvement. However, occasionally no immediate reponse has been seen, but delayed improvement has been observed following tenectomy.23 Myotomy and myotenectomy have been associated with a relatively high degree of postoperative complications compared with simple tenectomy. If portions of muscle are excised, submission of these samples to a histopathologist with expertise in the pathology of neuromuscular disease may aid in determining the cause. Recurrence and exacerbation of clinical signs after myotomy and myectomy are the most common complications. Occasionally myotomy (fibrotomy) results in appreciable clinical improvement in horses with well-defined scars. At least partial recurrence of fibrotic myopathy after successful surgery occurs in about one third of horses, although the resultant gait deficit may not interfere with full return to function.22 If progressive neuropathy is the cause, recurrence of signs after any type of surgery is likely.

Stringhalt

Clinical Characteristics

A horse with stringhalt has an exaggerated upward flexion of a hindlimb or both hindlimbs that occurs at every walk stride (see Figure 48-1)![]() .24-26 The affected limb is brought up and in (adducted) underneath the horse, such that the fetlock may contact the ventral abdominal wall. This abnormal gait often lessens considerably during the trot and usually, but not always, disappears at the canter. Affected horses may have difficulty backing, and the gait abnormality may only be apparent while backing in horses with mild disease. In such horses a diagnosis of mild shivers should also be considered. The Australian form of stringhalt is often bilateral and occurs in groups of horses on pasture containing a plant similar to dandelions known as flatweed (Hypochoeris radicata).3 The toxic principle is as yet unknown. Forelimbs may also be affected in horses with Australian stringhalt. A similar syndrome has been seen in the Pacific Northwest of North America,24 in Europe,26 and in South America.27 In an outbreak in Brazil, plants containing H. radicata were fed to a normal horse and mild stringhalt developed, but signs abated when a similar plant from a different location was fed, leading to speculation that plants may vary in toxicity.27 In mice, ingestion of H. radicata was associated with a significant increase in a metabolic biomarker, scyllo-inositol, known to be associated with other neurodegenerative diseases from neuronal and glial dysfunction.28 Horses with stringhalt may or may not appear distressed by the gait abnormality. Similar to shivers (see the following discussion), anxiety and cold weather are reported to increase the severity of clinical signs in horses with stringhalt.4,24

.24-26 The affected limb is brought up and in (adducted) underneath the horse, such that the fetlock may contact the ventral abdominal wall. This abnormal gait often lessens considerably during the trot and usually, but not always, disappears at the canter. Affected horses may have difficulty backing, and the gait abnormality may only be apparent while backing in horses with mild disease. In such horses a diagnosis of mild shivers should also be considered. The Australian form of stringhalt is often bilateral and occurs in groups of horses on pasture containing a plant similar to dandelions known as flatweed (Hypochoeris radicata).3 The toxic principle is as yet unknown. Forelimbs may also be affected in horses with Australian stringhalt. A similar syndrome has been seen in the Pacific Northwest of North America,24 in Europe,26 and in South America.27 In an outbreak in Brazil, plants containing H. radicata were fed to a normal horse and mild stringhalt developed, but signs abated when a similar plant from a different location was fed, leading to speculation that plants may vary in toxicity.27 In mice, ingestion of H. radicata was associated with a significant increase in a metabolic biomarker, scyllo-inositol, known to be associated with other neurodegenerative diseases from neuronal and glial dysfunction.28 Horses with stringhalt may or may not appear distressed by the gait abnormality. Similar to shivers (see the following discussion), anxiety and cold weather are reported to increase the severity of clinical signs in horses with stringhalt.4,24

Cause

True stringhalt and sporadic, or pasture-associated, stringhalt are most likely caused by underlying neuropathy. The Australian form of stringhalt has been clearly shown to be from underlying neuropathy.3 Some horses with sporadic stringhalt have had evidence of neuropathy and denervation atrophy, although the cause has not been apparent. Histopathological evaluation of the lateral digital extensor muscle after lateral digital extensor myotenectomy has been particularly useful in detecting evidence of denervation atrophy. Horses with equine motor neuron disease have generalized denervation atrophy and can develop stringhalt that may be bilateral. Denervation atrophy of numerous muscles of the affected hindlimb is seen in horses with stringhalt from EPM. Careful examination of numerous nerves from horses with sporadic24 or pasture-associated stringhalt3 has revealed widespread neuropathy. Laryngeal hemiplegia associated with stringhalt is common, indicating a predisposition for abnormalities of long nerves. Stringhalt may be a different form of neuropathy than that seen in horses only developing laryngeal hemiplegia because clinical signs in some horses that develop stringhalt spontaneously resolve. Stringhalt may be similar to peripheral neuropathies in dogs, in which long nerves such as the recurrent laryngeal and sciatic nerves can be preferentially involved, and the cause is often not known. Lesions occur in the left recurrent laryngeal nerve in about 60% of horses with Australian stringhalt.3 Clinical signs of laryngeal dysfunction may or may not be apparent. Development of stringhalt has been reported in horses after trauma to the dorsal tarsal and metatarsal regions in the area of the extensor tendons.25 If proprioceptive deficits and ataxia are detected in a horse with stringhalt, peripheral neuropathy caused by EPM should be considered likely.

Biomechanical Basis

Although underlying neuropathy is well established as a cause of stringhalt, the biomechanical basis for the exaggerated flexion is still somewhat perplexing. Altered proprioception from neuropathy was suggested,6 and this hypothesis is appealing. In stringhalt, however, the gait deficit appears to be consistently abnormal, stride to stride, unlike that seen in horses with other forms of proprioceptive deficits. Neuropathy may lead to paresthesia or altered input to or activity of muscle spindles. Given the exaggerated flexion of the hindlimbs of most horses after placement of hindlimb shipping (traveling) boots, altered sensation leading to limb hyperflexion is plausible. Other proposed causes include tendon adhesions around the tarsocrural joint or altered tendon reflexes after trauma24 and hyperexcitability of motor neurons.4

Medical Therapy

For horses with stringhalt associated with plant toxicity, removal from the pasture may be curative, although recovery may take months to years and may not be complete.4 Trauma-induced stringhalt may resolve with exercise therapy.25 Oral phenytoin at 15 to 25 mg/kg once or twice daily may also be effective in some horses. The beneficial actions of phenytoin may include stabilization of neuronal, peripheral nerve, or skeletal muscle membrane electrical activity or decreased anxiety from sedation.4 Botulinum toxin type B was used to reduce anal tone in horses, and it is compelling to consider its use for management of horses with stringhalt and other neuromuscular conditions.29 Horses appear unusually sensitive to the effects of botulinum toxin; therefore caution should be used. In a recent experimental and clinical study, normal ponies (400 IU) and two Warmbloods with stringhalt (700 IU) were injected with botulinum toxin type A into the long digital extensor, lateral digital extensor, and vastus lateralis muscles.30 Surface electromyography revealed reduced surface signals over the injected muscles; there was obvious clinical improvement in the two horses with stringhalt that lasted 12 weeks after injection, and kinematic studies confirmed a reduction in intensity of hindlimb hyperflexion.30

Surgical Therapy

Horses with residual gait abnormality after plant toxicity or traumatic neuropathy and horses with stringhalt caused by degenerative peripheral neuropathy may benefit from lateral digital extensor myotenectomy.26 Horses with traumatically induced stringhalt appear to benefit most from lateral digital myotenectomy. In some horses, clinical signs may actually gradually worsen after surgery. Resolution of clinical signs after blocking the lateral digital extensor tendon may be a useful response to determine whether myotenectomy is indicated (see Chapter 122). In horses with stringhalt in which local anesthetic solution is placed directly into the lateral digital extensor muscle, both of us have observed 50% to 75% improvement in clinical signs, but clinical signs also improve if the cranial tibial and long digital extensor muscles are blocked. Selective blocking of the superficial and deep fibular (peroneal) nerves, the common fibular nerve, and the tibial nerve may help determine etiology in some horses, but the response is inconsistent. Selective peroneal (fibular) neurectomy remains a potential method of surgical management. Although some affected horses may return to full and high-level athletic performance after surgery, for many this should be considered a salvage procedure to allow a more normal gait for breeding horses, pasture pets, and horses in which the owner’s expectations of performance are limited to light hacking.

Shivers (Shiverers, Shivering)

Clinical Characteristics

First described in draft breeds, shivering also occurs commonly in Warmbloods. Anecdotal evidence suggests a heritable predisposition. Shivers also occurs sporadically in other breeds, including Thoroughbreds, Quarter Horses, Arabians, and Morgans.

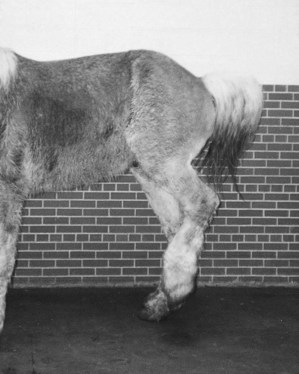

The clinical features of shivers, particularly in horses with early or mild disease, may resemble stringhalt or intermittent upward fixation of the patella. Affected horses may be described as stringy, especially by draft horse owners. Affected horses exhibit an episodic hyperflexion of the hindlimb and often abduct the limb before placing the hoof on the ground (see Figure 48-1). The affected limb may be held up in a flexed and abducted position for several seconds. This is most commonly seen when the limb is picked up. Sometimes the tail is simultaneously raised (Figure 48-3) ![]() . The horse may stretch its head up or forward during these episodes, and flickering of the eyelids and ears occurs occasionally. The muscles of the affected limb may tremble, and sometimes the tail quivers. Some horses only show clinical signs when the limbs are picked up and have a normal gait under all other circumstances. If an abnormal gait is present, unlike stringhalt it is sporadic rather than occurring at every stride and is not apparent at the trot or canter. The abnormal gait is most often seen when backing, turning tight circles, in the first walk stride after standing, and in the last walk stride before halting. The clinical signs may also be seen periodically while the horse is standing still. Anecdotally, the abnormal gait may be exacerbated by lack of exercise, cold ambient temperature, and increased anxiety in the horse. Neurological examination does not reveal evidence of postural reflex abnormalities or of ataxia.

. The horse may stretch its head up or forward during these episodes, and flickering of the eyelids and ears occurs occasionally. The muscles of the affected limb may tremble, and sometimes the tail quivers. Some horses only show clinical signs when the limbs are picked up and have a normal gait under all other circumstances. If an abnormal gait is present, unlike stringhalt it is sporadic rather than occurring at every stride and is not apparent at the trot or canter. The abnormal gait is most often seen when backing, turning tight circles, in the first walk stride after standing, and in the last walk stride before halting. The clinical signs may also be seen periodically while the horse is standing still. Anecdotally, the abnormal gait may be exacerbated by lack of exercise, cold ambient temperature, and increased anxiety in the horse. Neurological examination does not reveal evidence of postural reflex abnormalities or of ataxia.

Fig. 48-3 Belgian draft horse exhibiting the raised tail and hindlimb overflexion characteristic of severe shivers.

The farrier may first diagnose shivers because trimming and shoeing the hindlimbs is often difficult. The horse may be reluctant or appear unable to hold the affected limb up or to stand on three limbs for any length of time. When asked to lift a hind foot, the horse often hesitates, followed by an exaggerated flexion. Affected horses may appear worried when a hindlimb is picked up. They may be more comfortable if allowed to turn the head and neck toward the limb being picked up.23

Shivers may be a progressive disorder in some but not all horses. Severely affected horses develop generalized muscle atrophy and weakness and may exhibit periodic cramping of each leg in succession, with occasional leaning of the body such that the horse appears ready to fall. Onset is often between 2 and 4 years of age, but this varies extremely, as does the rate of progression. One of the authors (SJD) is aware of a homebred 10-year-old Warmblood mare that exhibited shivers as a neonate and has continued to show similar clinical signs throughout its life. The most severe form of progressive shivers occurs in draft horses. A somewhat milder form occurs in Warmbloods, in which sporadic abnormal hindlimb action is seen, but Warmbloods with shivers rarely exhibit a raised and quivering tail. Clinical signs in such horses are often mistaken for stringhalt or intermittent upward fixation of the patella. Affected horses can continue to compete at high levels in dressage or jumping for many years. Prepurchase evaluation of these high-performing shiverers can be particularly vexing because the expected progression of signs is completely unpredictable.

Occasionally shivering is seen in one or both forelimbs. The gait is usually not affected; however, when the limb is picked up, the limb shows muscle tremors.

A recently recognized and poorly understood syndrome known as “stiff-horse syndrome” may resemble shivers. Affected horses have a stiff gait and muscle spasms in the epaxial muscles of the lower back and in the muscles of the hindlimbs. Spasms may be precipitated by voluntary movements or by someone picking up a limb. Increased levels of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase have been reported.31

Abnormal flexion of one or both hindlimbs mimicking shivering has also been seen as a result of chorioptic mange affecting the distal aspect of the hindlimbs of a Shire horse.23

Cause

Although an underlying neuropathy was proposed, careful study of two draft horses with shivers failed to reveal evidence of peripheral or central nervous system disease.1 Examination of muscle from these and a small but growing number of horses with shivers of various breeds has revealed underlying EPSSM. Contiguous groups of glycogen-depleted skeletal muscle fibers in muscles of the proximal thigh and back have been seen in a small number of horses studied and indicate that this disorder may involve episodic muscle contracture (cramping).1 However, a more recent study in Belgian draft horses failed to demonstrate a convincing association between EPSSM and shivers.32

Biomechanical Basis

Explaining the abnormal gait of shivers is difficult. The possible role of episodic muscle cramp or abnormal sensations within the affected leg is worthy of further study. Horses with an abscess in a hind hoof may show an abnormal flexing of the limb while standing that resembles shivers, and hind hoof abscesses often increase the abnormal action of the affected hindlimb in horses with shivers.

Medical Therapy

There is no reliable method of treatment. Change to a high-fat and low-starch and low-sugar diet may be beneficial in some horses after 4 to 6 months.2,8 Whether this therapy acts by decreasing muscle cramping, decreasing anxiety in the horse, a combination of these effects, or some other mechanism is still unknown. These horses include those in which muscle biopsy revealed characteristic changes of EPSSM and horses with no apparent abnormalities in the muscle samples examined. Improvement is often only partial, but most owners have been pleased with results, and it is conceivable that dietary therapy may help to slow the progression of the disease.

Hindlimb Extensor Weakness

Group outbreaks of bilateral hindlimb extensor weakness resulting in knuckling of the hind fetlocks either transiently or for longer periods, or in horses with more severe signs, such as inability to ambulate faster than a walk or paraplegia, have been associated with the consumption of big bale silage or poor quality fungal-infested hay.33 In some horses, clinical signs were mild and nonprogressive, whereas in others severe signs developed within hours. Affected horses showed no signs of flexor weakness or ataxia, but some showed proprioceptive deficits and reduced skin sensation. In some horses, spontaneous resolution of clinical signs was observed over 6 months, whereas in others clinical signs were slowly progressive. Post mortem examination revealed consistent evidence of neuronal degeneration in the sciatic nerves and to a lesser extent in the lumbar intumescence of the spinal cord; however, other peripheral nerves were not routinely examined. Clinical signs in some of the mildly affected horses were consistent with femoral nerve paralysis (see also Chapter 11).

Unilateral or bilateral femoral nerve paralysis most commonly occurs after general anesthesia.34 If unilateral, the horse cannot extend the stifle and rests the limb in a flexed position on the dorsal aspect of the fetlock. If bilateral, the horse is unable to stand for any length of time, except in a crouched position with the hindlimbs flexed.

Intermittent knuckling of one or both hind fetlocks when ridden may be seen alone or in association with another cause of hindlimb lameness. It may reflect a proprioceptive deficit, altered limb placement in an attempt to minimize pain, or be neurologically mediated.23 The rider may complain that the hindlimbs sporadically “give way.” Often young horses in early race training stumble or knuckle behind, a condition sometimes referred to as “loose stifles.” This condition may be more common in young Standardbred racehorses and is often managed with patellar intraligamentous or periligamentous injections of counterirritants. Efficacy is questionable, but in most horses the condition resolves as training continues.

Stumbling

Stumbling may occur in front or behind. Stumbling in front is frequently a reflection of foot pain; foot placement is altered to try to minimize pain, resulting in a more “toe first” landing pattern. Stumbling behind may be a reflection of extensor weakness (see Hindlimb Extensor Weakness section). It may also be a reflection of hindlimb lameness that results in toe drag (see Toe Drag section). Stumbling either in front or behind is often worst on uneven footing.

Flexion of the Fetlock and Inability to Load the Heel

Permanent semiflexion of a fetlock with inability to fully load the heel may be the result of chronic desmopathy of the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT). In forelimbs, this is usually unilateral and is the result of chronic work-related injury of both the accessory ligament of the DDFT and the superficial digital flexor tendon, with associated adhesion formation. In hindlimbs the condition may be unilateral or bilateral and is associated with a chronic degeneration of the accessory ligament of the DDFT (see Chapter 71).35

Toe Drag

Some clinically normal horses show a mild bilateral hindlimb toe drag, especially when worked on a soft surface, which may not be apparent under other circumstances.23 A unilateral hindlimb toe drag is usually a reflection of a pain-related lameness. A bilateral hindlimb toe drag may reflect laziness, unfitness, long toes as a result of poor trimming, weakness, flexor weakness, bilateral lameness, ataxia, scirrhous cord, mastitis, and thoracolumbar or sacroiliac region pain.

Pacing at the Walk

Walk is normally a four-beat gait: left hind, left fore, right hind, right fore. Occasionally a horse starts to pace at the walk, that is, the left hindlimb and left forelimb are advanced more or less simultaneously, followed by the right forelimb and hindlimb in an almost two-beat gait. This is often variable in degree within and between examinations and is usually most obvious when the horse is walking down an incline. This change in interlimb coordination is believed to be neurologically mediated, although no other gait abnormality or neurological deficit is detectable, and the mechanism has not been defined.36 Other aspects of performance may be completely unaffected. The gait is not influenced by antiinflammatory analgesic drugs. The pace is considered a primitive gait, whereas the walk is one of the most complex because of the variability in overlap and lag time between limbs.37 Once a horse has started to pace at the walk, it usually continues to do so. Pacing may have no clinical relevance in some horses, particularly older horses that curiously develop the condition spontaneously. However, in young horses not bred to pace (i.e., Standardbreds), pacing may be an early sign of progressive neurological disease.

Stepping Short on a Hindlimb at the Walk

Stepping short on one hindlimb at the walk but with no detectable lameness at the trot is a poorly understood syndrome, which may be sudden in onset and tends to be persistent despite prolonged rest, with or without physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic manipulation, or acupuncture treatment. Such horses have an obvious gait abnormality when ridden at the walk but perform normally at all other gaits. When examined moving in hand at the walk, the hindlimb gait is usually symmetrical. There is no response to antiinflammatory analgesic drugs or any local analgesic technique. Comprehensive radiographic, scintigraphic, and ultrasonographic examinations are unrewarding.

The gait may be influenced by neck position, being more obvious in a collected walk than if the horse is allowed to walk on a long rein. The cause is unknown. Continued work does not seem to have a deleterious effect.

Unusual Abduction of a Hindlimb

Rarely, a horse is observed to have excessive abduction of the hindlimb during protraction. Gait deficit is prominent at the walk but abates at the trot. No obvious source of pain can be found, and horses appear able to perform with this unusual gait deficit. Excessive abduction at the walk may be a manifestation of shivers, but we have observed this deficit rarely in light breeds as well.

Other Mechanical Lamenesses

The biomechanical basis of mechanical lameness resulting in decreased flexion of the stifle and hock, such as fibrotic myopathy and upward fixation of the patella, is readily understood. These gaits are also characteristic and readily distinguished from other mechanical lamenesses. However, the mechanical lamenesses resulting in hyperflexion—that is, intermittent upward fixation of the patella, stringhalt, and shivers—have clinical similarities that can make them difficult to distinguish. One may also safely say that altered gaits from abnormal muscle or nerve function may not fall into one of the previously defined categories. A horse may appear stringy, locked up, have a goose waddle or stiff, stabbing hindlimb gait, or just appear off in a hindlimb because of mechanical lameness. A slight reduction in hock flexion at the walk may be considered normal for a horse, but this gait may also reflect a mechanical lameness (see Chapters 12 and 97).

In all horses with perplexing hindlimb lameness, the possibility of a form of mechanical lameness should be considered. This is especially true in breeds such as draft, Quarter Horse, and Warmblood-related breeds that are recognized to have a predilection for underlying myopathy. Because underlying myopathy or neuropathy is likely to be the most common cause of mechanical lameness, electromyography and muscle biopsy should be considered in all horses with mechanical lameness of the forelimbs or hindlimbs.