Chapter 2 Lameness in Horses

Basic Facts Before Starting

Lameness is therefore not so much an original evil, a disease per se, as it is a symptom and manifestation of some antecedent vital physical lesion, either isolated or complicated, affecting one or several parts of the locomotive apparatus.

Definition

The clinical manifestations of lameness in the horse are well known, but an exact definition is difficult. The word lame is an adjective, meaning “crippled or physically disabled, as a person or animal … in the foot or leg so as to limp or walk with difficulty.”2 A medical dictionary defines lameness as “incapable of normal locomotion, deviation from the normal gait.”3 The noun lameness can be, but infrequently is, used interchangeably with claudication, described as “limping or lameness.”3

Lameness is simply a clinical sign—a manifestation of the signs of inflammation, including pain, or a mechanical defect—that results in a gait abnormality characterized by limping. The definition is simple, but recognition, localization, characterization, and management are complex.

Localization of Pain

In certain conditions, characteristic gait abnormalities allow immediate and straightforward recognition and localization of the problem. Sweeny, fibrotic myopathy, upward fixation of the patella, stringhalt, shivers, and radial nerve paresis are examples. However, similar gait deficits exist for a variety of lameness problems, complicating recognition and localization. A fundamental concept in lameness diagnosis is the application of diagnostic analgesic techniques to localize the source of pain causing lameness. The sequence of properly determining the lame leg (recognition) and then abolishing the clinical sign of lameness by use of diagnostic analgesia (localization), only to have lameness return when the local anesthetic effects abate, is essential for accurate diagnosis. In essence diagnostic analgesia establishes clinical relevance, a most important concept to the lameness diagnostician. With experience and under certain circumstances, this step in lameness diagnosis can be omitted. The degree of lameness, certain gait characteristics, and palpation findings allow the clinician to strongly suspect a certain diagnosis. The next step may be diagnostic imaging. For example, a racehorse with prominent lameness after training may be suspected of having a stress or incomplete fracture. Performing radiographic and scintigraphic examinations before proceeding with diagnostic analgesia is a prudent choice. Trial and error also occasionally work and in some instances may be the preferred approach. Intraarticular analgesia can be performed in selected joints without disrupting distal-to-proximal perineural techniques later during the same examination. However, because pathognomonic signs are rare, proficiency in diagnostic analgesic techniques is mandatory for the lameness diagnostician.

Baseline and Induced Lameness

Baseline, or primary, lameness is the gait abnormality recognized when the horse is examined at a walk or trot in hand before flexion or manipulative tests are used. The clinician usually recognizes this abnormality by watching the horse on a firm or hard surface, while it is being trotted in a straight line. Diagnostic analgesia is used to abolish this lameness. Changing the surface or nature of the exercise by lunging, or circling the horse at a trot in hand, potentially changes the baseline lameness. The surface and exercise (gait and speed) must be consistent. In some horses no observable lameness is present at a walk or trot in hand. Lameness may be evident when the horse is ridden, and this lameness becomes the baseline lameness.

Flexion tests and other forms of manipulation are used to exacerbate baseline lameness or to induce lameness. An induced lameness is one that is observed after flexion or manipulative tests, but induced lameness may not be the same as the baseline lameness. Manipulative tests are expected to, and often do, exacerbate the primary lameness. However, flexion and manipulative tests can cause development of additional lameness, unrelated to the primary or baseline lameness, and test results must be interpreted carefully.

Coexistent Lameness

Horses often have several sites of pain, although one usually is most obvious and the cause of baseline lameness. In many horses, secondary or compensatory (sometimes referred to as complementary) lameness develops in predictable sites or limbs. Concomitant bilateral forelimb or hindlimb lameness is common, but horses often demonstrate more prominent clinical signs in one limb. In horses with palmar foot pain, initially pronounced single forelimb lameness that is abolished by palmar digital analgesia may be present, with subsequent recognition of contralateral forelimb lameness. In racehorses, bilateral lameness, such as in the carpi or metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joints, is common. The clinician should carefully examine the contralateral limb. Predictable compensatory or secondary lameness often exists in the ipsilateral or contralateral forelimb when primary lameness is present in the hindlimb, or vice versa. In a Thoroughbred (TB) racehorse with left forelimb lameness, compensatory problems in the right forelimb and left hindlimb are not uncommon, because these limbs presumably are succumbing to excessive loads while protecting the primary source of pain. In a trotter, diagonal lameness often occurs (primary lameness in the left hindlimb and compensatory lameness in the right forelimb), whereas in pacers, ipsilateral lameness is most common (primary right forelimb and compensatory right hindlimb). When several limbs are involved, identification of the primary or major source of pain is important. If forelimb and hindlimb lameness exist simultaneously, diagnostic analgesic techniques should begin in the hindlimb (see Chapter 10). A common secondary lameness abnormality, proximal suspensory desmitis, can develop in the compensating forelimb or hindlimb.

Coexistent lameness can make assigning primary or baseline lameness to a particular limb during lameness examination difficult (see Chapter 7). Bilaterally symmetrical pain may cause a short, choppy gait, but primary or baseline lameness often cannot be seen when the horse is examined in a straight line in hand. Often, horses with coexistent lameness must be circled, lunged, or ridden for primary or baseline lameness to be observed. The lameness diagnostician may have to arbitrarily assign lameness to a limb and begin diagnostic analgesia in this manner. Often, once the primary source of pain has been identified, horses show pronounced lameness of much greater magnitude than expected in another limb, vivid clinical evidence that coexistent lameness exists.

Lameness Distribution

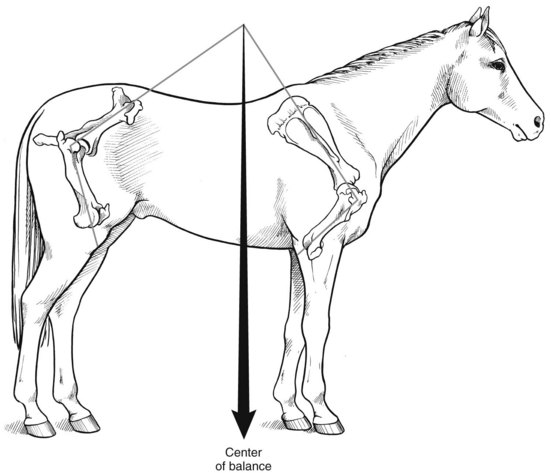

Among all types of horses, forelimb lameness is more common than hindlimb lameness. A horse’s center of gravity or balance, while dictated to a certain extent by conformation (see Chapter 4), is not located in the center of the horse but is closer to the forelimbs than the hindlimbs. Thus the forelimb/hindlimb (F/H) weight (load) distribution ratio is approximately 60% : 40% (Figure 2-1). Higher loads are expected on the individual forelimbs (30% each), predisposing the horse to greater injury.

Fig. 2-1 The center of balance (gravity) of the horse is located closer to the forelimbs, which accounts for the load distribution difference between the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Conformation, namely the angles of the shoulder and rump, and weight of the head and neck and gait can change this load distribution.

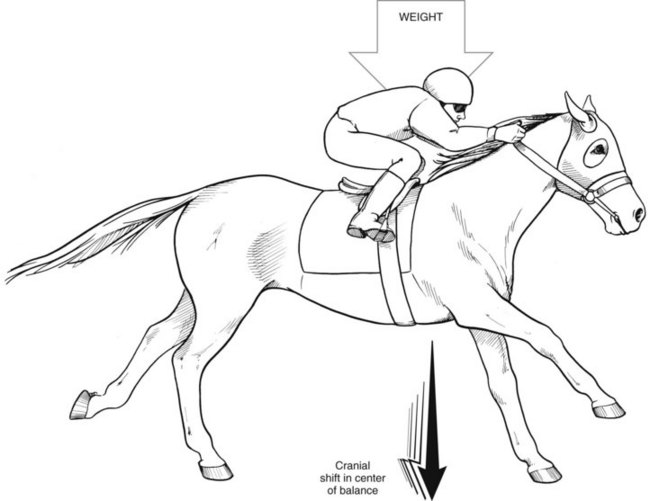

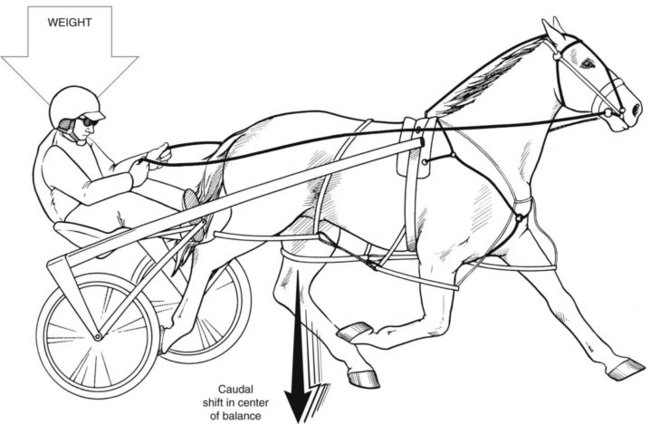

At certain times during the stride cycle of gaits such as the canter (three-beat gait) and gallop (four-beat gait), a single forelimb is weight bearing, which predisposes the limb to injury. The weight of a rider may shift F/H load distribution to 70% : 30% (Figure 2-2). Two-beat gaits, such as the pace and trot, allow more equal load sharing between forelimbs and hindlimbs because a forelimb and hindlimb (ideally, if the gait is balanced perfectly) hit the ground simultaneously. In pacers and trotters the proportion of forelimb lameness is less than in the TB racehorse. The added load of pulling a sulky, cart, or any heavy load increases the likelihood of hindlimb lameness in Standardbreds (STBs), other harness breeds, and draft horses (Figure 2-3). The F/H distribution of lameness in STB racehorses is 55% : 45%. Sporting activities such as dressage and jumping also may shift lameness distribution to the hindlimbs because collection (working off the hindlimbs) and propulsion needed by horses to perform these activities may predispose to hindlimb lameness. The tendency of good moving dressage horses to show advanced diagonal placement in trot results in a single hindlimb bearing weight.

Fig. 2-2 Gaits such as the canter and gallop (depicted) and the added weight of a rider, as shown here in a Thoroughbred racehorse, increase load on the forelimbs by shifting the center of balance, thus increasing the likelihood of forelimb lameness.

Fig. 2-3 In a Standardbred racehorse (pacer depicted), the hindlimbs share added load compared with a Thoroughbred racehorse because of a caudal shift in the center of balance. The type of harness with the overcheck bit, the added weight of the sulky and driver, and the necessity of pulling a load increase the likelihood of hindlimb lameness in this breed.

In the forelimb, up to 95% of lameness problems occur at the level of or distal to the carpus.4 The distal parts of the limb always should be excluded as a potential source of lameness before the upper limb is addressed, although many owners believe otherwise and may try to mislead an inexperienced practitioner. The foot should be suspected first. Pain in the foot is one of the most common causes of forelimb lameness in all types of horses, and in draft breed horses, the foot is also the most common site of pain in the hindlimb.

Hindlimb Lameness

Hindlimb lameness should not be underplayed, although its recognition is more difficult. In the forelimb lameness–prone TB racehorse, many hindlimb lameness problems are overlooked. However, a rider or jockey often may suspect a hindlimb problem when the lameness actually exists in the forelimb.

A practitioner should consider carefully the distribution of sites of hindlimb lameness. Historically, the hock has been regarded as the major source of problems, and although it is an important source of hindlimb lameness, other sites also are important. For instance, in both the TB and STB racehorse the metatarsophalangeal joint is a major source of lameness that historically has been overlooked.5,6 Maladaptive or nonadaptive bone remodeling of the distal aspect of the third metatarsal bone cannot be seen radiologically in early stages and requires careful diagnostic analgesic techniques to achieve localization. Scintigraphic examination is mandatory for definitive diagnosis.7 Lameness of the metatarsophalangeal joint in STBs is almost as common as that of the hock, but without careful examination and the use of diagnostic analgesia, hock lameness is suspected in many such horses and they are treated for it. In sports horses proximal suspensory desmitis is now recognized as a more important cause of lameness than hock pain. The combined use of diagnostic analgesia, ultrasonography, and scintigraphy has increased clinical knowledge of the broad spectrum of lameness conditions in the hindlimbs.

In the draft horse, lameness in the hindlimb most commonly develops in the foot. Lameness in this area reflects the work performed by these horses, and innate characteristics of the draft horse foot, which predispose the foot to conditions such as laminitis. In jumping and dressage horses, problems in the fetlock region such as osteoarthritis and tenosynovitis are common and reflect the stress imposed by these disciplines. Although owners, trainers, and veterinarians often suspect an upper hindlimb lameness, gait characteristics of lower limb lameness problems often are similar. Only use of diagnostic analgesia allows an accurate diagnosis.

Relationship of Lameness and Conformation

Conformation of the distal extremities, and to a lesser extent the overall body, plays a major role in the development of forelimb and hindlimb lameness (see Chapter 4). When a practitioner examines a weanling or yearling with poor conformation, predicting the time and the exact way the lameness will occur may be difficult, but many well-recognized conformational faults can lead directly to lameness problems. Conformational faults of the carpus, such as carpus varus or valgus, back-at-the-knee, and offset knees, can be important factors in carpal and lower forelimb lameness. In the hindlimbs, excessively straight hindlimbs (“straight behind”) and sickle-hocked and in-at-the-hock conformation can lead directly to predictable lameness conditions. Although exceptions do exist, in the case of poor conformation, predictable lameness conditions consistently develop in poorly conformed horses. Evaluation of conformation is therefore an essential part of a lameness examination.

Poor Performance

Convincing trainers and owners may be difficult, but the leading cause of poor performance in racehorses is lameness, and lameness is the most prevalent health problem among all horses.8-11 In one study, 50% of North American operations with three or more horses had one or more lame horses, and 5% of the horses could be expected to be lame.10 In another study, 74% of racehorses evaluated for poor racing performance had substantial musculoskeletal abnormalities contributing to poor performance. Lameness examination was emphasized as a most important aspect of comprehensive performance evaluation.12,13 Others have emphasized the importance of lameness in epidemiological studies evaluating wastage in TB racehorses.14,15 Recently, lameness was once again found to be the most important condition causing missed training days in TB racehorses training in the United Kingdom.16 Two-year-olds missed training days significantly more than 3-year-olds, and stress fractures were the most important cause of lameness.16 Disappointingly, there has been little change in the importance of lameness and missed training days in the United Kingdom over a 20-year period.16 The same is likely true among all sports horses, particularly those competing at upper levels, although comprehensive studies have not been performed. Obvious lameness need not be demonstrated for performance to be compromised in horses, especially those competing at high speeds or upper levels. The possibility of achieving maximal performance in horses with substantial lameness is a common misconception. I have examined numerous top-level STB and TB racehorses in which easily recognized lameness is seen when the horses are trotted in hand on a hard surface. Notwithstanding the ignorance of many in the horse industry, the ability of many horses with obvious lameness to compete is a tribute to their mental and physical toughness. For example, bilateral forelimb or hindlimb lameness is common in racehorses but in some instances goes unrecognized if the condition is of similar severity in both limbs. Unilateral lameness of this magnitude would be recognized easily, but because the lameness is bilateral, horses still race, albeit at a lower level. Bilateral third carpal slab fractures and sagittal fractures of the proximal phalanx have been diagnosed in horses examined for poor racing performance but, if seen unilaterally, would have caused pronounced lameness. Part of the art of the lameness examination is separating those horses capable of performing with moderate pain at a high level from those that cannot do so.

Gait Deficits not Caused by Lameness

Gait abnormalities can exist with or without the presence of clinically apparent lameness. Deficits such as stringhalt, mild intermittent upward fixation of the patella, and shivers (see Chapter 48) can be present without obvious lameness and may complicate diagnosis of a completely different primary source of pain causing lameness. Horses with neurological disease may have gait deficits that are considered the result of painful lameness conditions (see Chapter 11). Horses with lower motor neuron diseases, such as equine protozoal myelitis, may have lameness associated with muscle atrophy or unexplained low-grade lameness associated with the disease. Concomitant lameness conditions can and do occur in these horses. Recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis can cause stiffness and in some instances lameness, or it can cause poor racing performance, all of which can be misinterpreted as lameness (see Chapter 83).

Unexplained Lameness

A diagnosis is made for most, but not all, lame horses through careful clinical examination and ancillary imaging modalities. Even with advanced imaging techniques, a solution is not always found (see Chapter 12), but it is hoped that future innovations in clinical examination and imaging will result in the continued expansion of the science of lameness diagnosis.

Components of the Lameness Examination and Lameness Strategy

Lameness Examination

Lameness examinations should be performed in an orderly, step-by-step way, but many factors may change or abbreviate the examination (Box 2-1). Owner financial constraints may not allow performance of certain diagnostic tests and may curtail the time necessary to complete the entire examination. Drug testing of competing racehorses or show horses may limit a practitioner’s ability to perform diagnostic analgesic techniques and restrict management options. Clients do not always understand the need for diagnostic analgesia. Education about the value of this technique, and the difficulties of interpretation of the results of diagnostic imaging without it, is vital.

Abbreviated lameness examinations often are performed in horses that exhibit severe lameness compatible with a fracture. Typical or obvious clinical signs may accompany severe lameness, and in many instances prolonged or extensive lameness examination is contraindicated. If incomplete fractures are suspected, diagnostic analgesic techniques may be dangerous and should be performed only in certain situations. A clinician may proceed directly to conventional or advanced imaging techniques before completing the initial steps of a conventional lameness examination.

Many other factors affect the ability to complete a comprehensive evaluation. Time constraints (usually of the veterinarian) often are cited, although shortcuts, if taken, usually create future problems. Omission of a diagnostic block or failure to perform detailed palpation often leads to misdiagnosis. Omission of a brief physical examination, including assessment of the horse’s temperature, can lead to embarrassing situations.

The footing available on which to complete the lameness examination can be problematic. A dry, flat, hard surface or space for lunging or riding may be unavailable. The horse’s temperament may preclude adequate movement and often limits the practitioner’s ability to perform diagnostic analgesia. Many ill-tempered horses are referred for advanced imaging techniques, such as scintigraphic examination, because diagnostic analgesic techniques are dangerous to the veterinarian and handler.

Lameness Etiquette

Owners frequently request an opinion from more than one veterinarian. Therefore professional, ethical conduct is important, with practitioner acknowledgment that horses can appear very different every day and that response to diagnostic analgesia is not always consistent. For example, differences of opinion concerning radiological interpretation can exist. A good working relationship with the client or agent is essential but should extend also to the farrier and any paraprofessionals involved in the management of the horse, even when opinions differ.

Prognosis Assessment

Assessment of prognosis for performance is important, but because few published data relating to many sports disciplines are available, clinicians often must rely on personal experience based on an understanding of the sport. Owners and trainers should consider prognosis carefully when making decisions to pursue therapeutic options, particularly when a long layoff period is required. I prefer to define prognosis as the “chance the horse will return to its previous level of competition.” However, this may not be a fair or reasonable definition.

Retrospective studies can be used to evaluate prognosis after surgical or conservative management for various conditions in racehorses. Objective data such as numbers of race starts, race times, earnings per start, and time from treatment to first race start can be assessed. Earnings per start is an important criterion because it establishes racing class or level of competition. However, in most retrospective studies, earnings per start decrease after treatment. The question is whether practitioners can accurately state that the horse will drop in class after treatment and whether this drop in class is the result of the injury, treatment, or aging of the horse an additional year before returning to racing. Use of this information is not easy.

Most owners and trainers have a different view of prognosis than the veterinarian. In considering the prognosis for a horse undergoing arthroscopic surgical removal of a small osteochondral fracture of the carpus, most owners emphasize the surgery rather than the original injury. Clinicians must explain thoroughly the magnitude of the injury and related damage and discuss prognosis, using terminology that clearly indicates that the extent of injury is the factor that determines prognosis.

Expecting a racehorse to return to its previous racing class may be an unrealistic expectation or at least a very strict definition for success. In a retrospective study of postoperative racing performance of STBs treated for carpal chip fractures, 74% of horses made at least one race start after surgery.17 Median earnings per start significantly decreased, but the median race mark (best winning time) also significantly decreased, indicating that horses made less money but raced faster after surgery.17 These results must be compared with a normal population of STBs as the horses age, without considering injury, because STB racing performance is not standard over time.18 Average earnings per start is highest in 2-year-old horses and decreases exponentially until retirement.18 A population of horses undergoing any long-term layoff that requires recommencement of racing the following year can be expected naturally (unrelated to the original injury) to have lower earnings per start, regardless of whether an injury occurred or treatment was given. Therefore retrospective studies may underestimate prognosis associated with injuries and management choices.

Success criteria and outcome assessment must be standardized to compare treatment results and to define prognosis. The current standard for racehorses is comparison of performance for five starts before and after injury and treatment. This criterion is strict; a practitioner first may prefer to predict the chance of the horse returning to racing and then assess the chance that the horse will perform at or near its previous level.

Other statistical methods have been used to evaluate racing performance in TBs using a regression model accounting for variables such as track surface, race distance, and age.19-21 To date, this performance analysis has been restricted to evaluation of horses after upper respiratory tract surgery but probably will be applied to horses with musculoskeletal injuries.

When comparing published information regarding management of various types of lameness, the clinician should be clear about criteria for inclusion of cases and be sure to compare “apples to apples.” For instance, comparing results of management of horses with chronic, recurrent hindlimb suspensory desmitis to those with acute forelimb suspensory desmitis is unfair.