Chapter 127Lameness in Breeding Stallions and Broodmares

Although maximal athletic fitness is typically not the goal for breeding stock, maintenance of musculoskeletal soundness is an important concern for breeding stallions and broodmares, especially because longevity is the usual expectation and a high percentage of these horses have existing musculoskeletal disease related to previous training and performance.

The Stallion

Musculoskeletal fitness is critical to breeding efficiency of a stallion. The principal management goals are to maintain adequate fitness for normal breeding behavior and to avoid conditions or treatments that may adversely affect spermatogenesis or sperm viability. Libido, mounting, thrusting, and ejaculatory dysfunction represent major causes of poor breeding performance in stallions.1 Musculoskeletal and neurological disease have been estimated to account for as much as 50% of these problems.1,2 The goal of managing a lame breeding stallion includes maintaining comfort and fitness to sustain libido and adequate copulatory agility.

Examination

Breeding stallions require skillful handling and are most efficiently examined in an area away from other stallions and mares, in a secluded area if possible. An experienced breeding stallion handler with appropriate restraint aids is ideal. Sedation can be used, but care must be taken not to confound the examination or jeopardize fertility. Phenothiazine tranquilizers, although useful for lameness examinations, have been associated with an increased risk of paralysis of the retractor penis muscle. If acepromazine is used, we recommend a small dose (5 to 10 mg intravenously 30 minutes before the examination) well before the horse gets excited, as well as diligent observation of the stallion for several hours to monitor its ability to retract the penis normally. Should the penis not retract with tactile stimulation once the horse is again otherwise normally alert and reactive, steps can be taken immediately for physical support and management to minimize loss of erectile function.3 For further diagnostic procedures (e.g., radiography), xylazine or detomidine and butorphanol may be necessary.

History should include signalment, information about the performance career, duration and details of breeding experience, current problem and associated details, medical history, medication, nutrition, and environment, including housing, breeding facilities (e.g., flooring and dummy), and breeding protocol (semen collection technique and stallion handling). Knowledge of old performance-related problems is useful. During the breeding season, the veterinarian should determine the breeding schedule because this will influence the diagnostic and therapeutic strategy.

Complete musculoskeletal evaluation in a breeding stallion ideally begins with a routine breeding soundness examination, including a general physical examination, examination of the internal and external genitalia, evaluation of at least two ejaculates collected 1 hour apart, and evaluation of penile microflora, as outlined by the Society of Theriogenology.4

The veterinarian should observe the stallion at a walk and trot in hand, preferably on an even, hard, flat surface or on grass; perform upper and lower limb flexion tests of the forelimbs and hindlimbs because osteoarthritis (OA) is common; examine the feet with hoof testers; and palpate the back. Manifestations of back pain include abnormal sinking, prolonged muscle fasciculation or guarding, and contraction of the epaxial muscles without touching the back. Back pain is common during the breeding season because of the work or secondary to lameness.

A simple neurological examination should include observation of the horse moving in small circles to the left and right, walking in a serpentine pattern with the head elevated, and assessment of hindlimb strength by pulling the tail as the horse walks. The veterinarian should look carefully for unusual patterns of muscle asymmetry, possibly indicative of equine protozoal myelitis (EPM) if the horse is in, or from, North America.

A stallion often is examined because of difficulty in breeding and should be observed during teasing, mounting, thrusting, and dismounting. Specific findings suggestive of a musculoskeletal or neurological problem include failure to couple squarely and to thrust with smooth, rhythmic pelvic action; asymmetric hindlimb weight bearing, particularly one hindlimb dangling while thrusting with the other; failure to properly flex or use the neck or back; abnormal tail posture (spiked high) and anal tone (relaxed, voiding gas or feces) during thrusting; an anxious look in the eye or atypical ear postures suggesting discomfort or distraction; failure to grasp securely with the forelimbs; lateral instability; falling during thrusting or dismount; weak, thready, or irregular ejaculatory pulses (often variable from day to day); and lameness after breeding.1 Common manifestations of musculoskeletal pain are reluctance to mount or dismount, early dismount, squealing during dismount, or savaging the mare or handler during or immediately after mounting. Frame-by-frame videotape analysis may help to determine when discomfort occurs, as well as to identify handling factors that enhance or impair performance. Diagnostic analgesia can be difficult to perform and is often unnecessary because of the obvious signs of OA. Further investigation in selected stallions may include ultrasonography, nuclear scintigraphy, and measurement of creatine kinase before and 1 hour after breeding.

Specific Diagnostic Considerations and Therapy

Sore Back

A sore back is associated with inadequate coupling and thrusting during breeding. A stallion may fail to wrap the pelvis or neck around the mare or dummy and may tend to hold its head off the neck of the mare and paddle with the forelimbs. Thrusting is often of irregular depth and rhythm, that is, choppy and interrupted. An acutely sore back may become a chronic condition, exacerbated by breeding and an increased number of unsuccessful mounts, unless treated aggressively.

It is important to determine the primary cause of lameness and initiate the appropriate treatment. Pain can be secondary to another musculoskeletal cause such as OA, a heavy breeding schedule, poor footing, poor shoeing, poor fitting of the breeding dummy to the stallion, or allowing the stallion to advance up the side of a dummy mount so that it is thrusting with a curved back. Chronic back pain may be treated using acupuncture once weekly for 8 weeks and repeated every 3 to 4 weeks or as needed.5 Acupuncture therapy may be combined with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy, or NSAIDs may be used alone.5,6

Prognosis for normal breeding performance is guarded to good and varies with management factors. One key factor is ejaculatory efficiency. Once a stallion needs more than one or two mounts per breeding, expected performance diminishes rapidly.

Osteoarthritis

A stallion with OA appears stiff and painful during breeding; stiffness is often worse after rest and improves with exercise. The carpus, front fetlocks, and hocks are affected most commonly. Diagnosis may be obvious on physical examination and is confirmed radiologically.

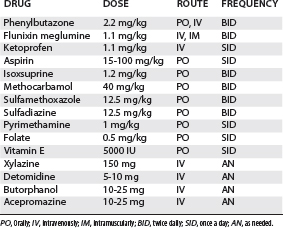

Pain control is essential to maintain adequate breeding performance. We recommend phenylbutazone (1.5 to 2 g orally [PO] twice daily for 4 to 5 days and then 1 g twice daily for 5 to 7 days)7 combined with a period of sexual and general rest if possible. Clinically significant improvement may not be evident for up to 5 to 10 days. Long-term, low-dose phenylbutazone treatment has no measurable effect on sperm production or testicular size,8 but horses should be monitored for signs of toxicity, including colic, loss of appetite, diarrhea, dependent edema, and mucosal ulceration or renal disease.9 Other NSAIDs, such as flunixin meglumine and ketoprofen, and intraarticular or systemic medication with corticosteroids, polysulfated glycosaminoglycans, and hyaluronan may be useful in selected horses.

Arthrodesis may be warranted for severe OA of the fetlock joint, but postoperative pain may persist, requiring long-term management. Pancarpal arthrodesis may be considered for stallions with severe carpal OA or after acute, severe carpal injury. With any lameness, pain management must be used to prevent increased recumbency, which can compromise thermal regulation of the testes, especially in hot conditions, and reduce sperm viability and fertility.

Neurological Disease

Neurological disease (see also Chapter 11) is usually evident during mounting, intromission, and thrusting, with a stallion stepping on its hind feet, bearing weight on a toe rather than the sole, and sometimes knuckling over. The stallion may bear weight unevenly during thrusting, sometimes becoming high sided on the mare or dummy mount, or falling. The stallion may have reduced proprioceptive control of the penis in seeking and intromission and may have poor anal tone during thrusting. The horse may require extraordinary effort to ejaculate.

Treatment of cervical vertebral malformation (CVM) in adult horses is challenging, and management methods are important, including good footing, proper shoeing, proper positioning of the mare or dummy mount, ground collection of semen, and pharmacological aids to ejaculation when necessary (Box 127-1).1,10 Special precautions must be taken during collection of semen or breeding to protect the stallion, the mare, and the personnel working around the stallion. The mare or dummy mount should be positioned to minimize the risk of a stallion with poor lateral stability falling. Lateral support can be provided at the hips. For semen collection, a mare that does not wiggle from side to side should be used. A dummy mount may be better but usually elicits less vigorous thrusting than a live mount and cannot be moved forward to assist the stallion with dismounting. Surgery occasionally is performed, with recovery taking many months.11

BOX 127-1 Management and Pharmacological Aids to Enhance Libido and Facilitate Ejaculation

Management Aids

The management of horses with EPM (see Chapter 11) is similar to that for horses with CVM, together with daily pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine or sulfamethoxazole for at least 60 to 90 days (Table 127-1). To prevent anemia, supplementation with folate and vitamin E is advised.12 This treatment does not affect sperm production adversely.13

Sore Feet

Signs of sore hind feet include shallow thrusting, failure to plant the feet securely during thrusting, thrusting on one leg, and early dismount. Signs of sore front feet or other forelimb pain include hesitancy to mount and dismount. If not resolved quickly, sore feet can lead to long-lasting psychogenic sexual behavior dysfunction.

Many breeding stallions that come from the racetrack have poor hoof quality, underrun heels, long toes, and thin soles, predisposing them to sore feet. The feet should be observed daily and trimmed every 4 to 6 weeks. Leaving stallions barefoot is best, but some may require front shoes to remain comfortable. Rarely, bilateral hind foot pain can cause similar clinical signs, and hind shoes with corrective trimming may be necessary (Editors). These horses may be left barefoot during the off season to allow the feet to grow more normally. Provision of soft footing in the breeding shed and weight control are important. Pain control using NSAIDs may be necessary.

Fractures of the Distal Phalanx

Fractures of the distal phalanx can be acute or chronic injuries. Most are palmar process fractures, and horses can be managed with a bar shoe with side clips reset every 6 weeks, stall rest, and NSAIDs. Sagittal fractures of the distal phalanx are more serious, but horses may be managed in the same way.

Laminitis

Common primary causes of laminitis include contralateral orthopedic injuries, colitis, Potomac horse fever, Salmonella, and other infectious diseases that predispose to the release of endotoxins. The treatment of horses with acute laminitis includes treating the primary disease, supporting the distal phalanx, decreasing blood pressure, treating inflammation, and managing pain (see Chapter 34).14-16

Chronic laminitis, with rotation of the distal phalanx, can be an important problem in breeding stallions, manifested as a stiff gait or more overt lameness in one or both front feet. Trimming, shoeing, and providing analgesia are important (see Chapter 34).

Muscle Disease

Rhabdomyolysis and other muscle diseases are usually evident during or after thrusting. Inefficient thrusting on early mounts is followed by increasing discomfort, leading to rapid mounting and dismounting. The horse may sweat profusely and have an increased respiratory rate and obvious pain. Treatment during an acute episode includes administering acepromazine (10 to 20 mg intravenously) to control anxiety and 10 to 20 L of balanced electrolyte solution intravenously, keeping the horse confined to a stall, monitoring progress, and evaluating the stallion closely for paraphimosis. In horses with chronic rhabdomyolysis, the diet should be altered to primarily hay and high-quality, low-protein, low-carbohydrate feed.17 Methocarbamol (see Table 127-1) is useful in some horses.

Injuries

Injuries in stallions, including lacerations, punctures, abrasions, and fractures or dislocations, are managed similarly as in other horses. A common injury is abrasion or contusion of the carpus during mounting, especially with dummy mounts. A stallion with a painful carpus may fail to grasp a mare with the forelimb and may stand up on the mare or dummy. Sexual rest until the wound heals is usually best. If continued breeding is necessary, emollient topical analgesic ointment and skillful bandaging from the coronet to several centimeters above the carpus can relieve apparent discomfort, with the administration of NSAIDs if required.

Hyperextension injuries of a forelimb may occur at dismount but are usually not serious and resolve with NSAID treatment.

Aortoiliac Thrombosis

Signs suggesting aortoiliac disease include delayed ejaculation despite good libido (numerous mounts and more than 12 thrusts); progressive hindlimb weakness or pain during thrusting resulting in camping under the mare or dummy; and difficulty backing up to dismount.18 Erection aberrations are not as common as ejaculatory dysfunction, but they can include delayed or rapid tumescence or detumescence, or loss of erection during thrusting.

Comprehensive Management

The useful breeding career of a stallion with lameness problems often can be prolonged substantially with coordinated veterinary care and breeding management. Particular concerns and challenges include the following:

Pain Management

Phenylbutazone is the most common NSAID used for breeding stallions. A 4-week oral treatment course (2.2 mg/kg twice daily) has no adverse effects on semen quality at the time of ejaculation or after 24 and 48 hours stored at 4° C.8 Although fertility trials have not been done, clinical experience suggests no adverse effects of chronic treatment with phenylbutazone at levels tolerated well by a stallion. We recommend orally administered phenylbutazone daily throughout the breeding season to keep the stallion comfortable and functioning with as little effort and pain as possible to avoid a potential downward spiral of delayed ejaculation, additional effort, and exacerbated lameness.

Firocoxib is now available for horses. Although not specifically tested in breeding stallions, efficacy for lameness has been reported to be similar to that of phenylbutazone.19

We have used gabapentin clinically in combination with phenylbutazone in an attempt to help breeding stallions with possible neurogenic and musculoskeletal discomfort.20 Early studies indicate that oral bioavailability of gabapentin is low compared with intravenous administration but is well tolerated at 20 mg/kg.21

Complementary pain management, including acupuncture,5,6 electrostimulation, and massage therapy, may provide additional comfort, with no adverse effects, on semen quality or fertility.

Fitness and Weight Management

Routine exercise is one of the most important management factors for maintaining cardiovascular and musculoskeletal physical and mental fitness of any breeding stallion. A general recommendation for exercise for a sound breeding stallion is daily paddock exercise for a minimum of 8 hours or a minimum of 30 minutes of supervised exercise or light work. Although the common tendency is to rest a lame horse, controlled exercise is probably even more important for breeding efficiency of a lame stallion. A daily exercise program, including turnout or supervised light work, appears to clinically significantly improve the breeding efficiency of a lame stallion. The type of exercise is influenced by the degree of lameness and the temperament of the stallion. Controlled exercise may include daily riding, lunging, jogging, swimming, or exercise on a treadmill or mechanical walker.

Libido and breeding efficiency almost always improve with a stallion carrying less rather than more body weight, particularly for hindlimb lameness or incoordination. We have seen remarkable improvement in breeding efficiency and stamina after reduction in body weight in Quarter Horses with small sore feet or in stallions with aortoiliac thrombosis.

Breeding Management and Handling

Breeding Schedule

For any hand-bred stallion, and particularly for a stallion with lameness, an important goal of breeding management is to minimize the work of each breeding and the cumulative work of the season. For heavily booked stallions, total seasonal work can be reduced and efficiency of each breeding often can be improved by limiting services to one per mare cycle. This forces upgraded mare management so that she is close to ovulation when covered. This type of mare tends to be more stimulating to the stallion and to stand more solidly for breeding. For certain stallions with smaller books, availability for service often can be limited to one mare, 3 or 4 days weekly. In our experience, by shifting effort toward mare management and effectively increasing the sperm numbers per service, seasonal pregnancy rates are often as good as or better than with more frequent services.

For stallions that are breeding by artificial insemination, with good to excellent longevity of sperm motility, a reasonable book of mares can be served with collection of semen limited to two or three times weekly. For stallions in registries permitting frozen semen, it is helpful to bank frozen semen for consideration for use during busy periods or to reduce pressure for obtaining fresh ejaculates when problems arise.

Maintaining Ideal Levels of Libido

It is important to maintain good to high libido to help a stallion to ejaculate more efficiently in the face of pain, neurological dysfunction, or musculoskeletal disability. Well-tested management schemes and pharmacological aids are available to enhance libido (see Box 127-1). The most useful management tools in a stabled stallion are housing near mares and away from stallions and ample daily teasing exposure to mares.22 Treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone can be useful to boost libido via increased circulating testicular steroids.23 Diazepam, by inhibiting the memory of pain associated with breeding, may be helpful.24,25

Occasionally, rowdy or overenthusiastic breeding behavior complicates management and breeding of a lame stallion. The stallion handler should use judicious correction and guidance to establish and maintain organized control, without overcorrection that will diminish libido.26 Medication is not recommended because tranquilization at a level effective to control behavior makes the stallion unstable for breeding, and using progesterone or other endocrine-mediated treatments adversely affects spermatogenesis.

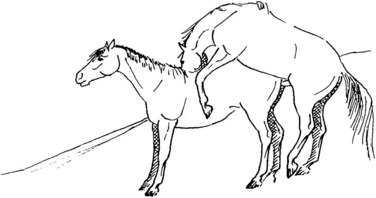

Breeding Shed Handling Considerations

Most disabled stallions benefit from having the mare or dummy mount slightly down grade. This can reduce the work of the hindlimbs in supporting the body weight. For a live mount mare, a down grade is achieved best with a sloping ramp extending at least 3 m behind, in front, and to each side of the mare (Figure 127-1). A height differential between the stallion and the mare can be built with mats or by placing the mare in a pit. These work well if the mare remains stationary, but if the mare moves back, the grade may be reversed for the stallion. If the mare moves forward, the stallion can become trapped between the mare and the front edge of mats, or in the pit with the mare. When breeding a stallion with the mare downhill, it is important to avoid the peak of a knoll that slopes off to the sides, behind the stallion, or in front of the stallion. This sets the stallion up to fall sideways should the mare move sideways or to be at further disadvantage if the mare moves backward. Once the stallion mounts, restraint of the mare should be optimized to reduce movement in any direction. Disabled stallions that are tentative to mount also can be deterred by low ceilings, cornered mares, or dummy mounts.

When using a dummy mount for stallions with hindlimb, back, or neck problems, we find that greater heights are better. Most disabled stallions do better when guided to remain mounted squarely from the rear, as opposed to across the dummy, or traveling up the side. This is best accomplished by securing the artificial vagina at a physiological angle against the dummy for the stallion to serve, rather than taking the artificial vagina to the horse.

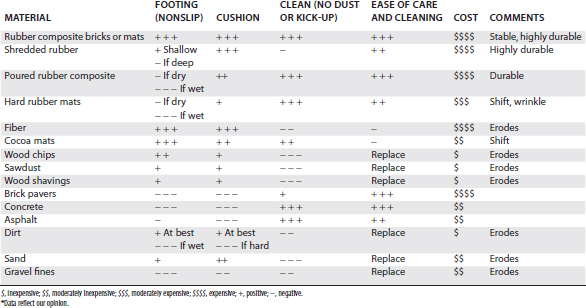

Excellent footing in the breeding area, which is customized to a stallion’s particular needs, can improve breeding efficiency greatly (Table 127-2). The surface should be nonslip even when wet, seamless and even to avoid stumbling, and provide moderate cushion. Stallions with hindlimb weakness or incoordination tend to camp under the mare. For these stallions the footing behind the mare is critical to maximize the ability to correct the stance. Although some cushion is good, it should not be so spongy or deep that the stallion gets caught up or buried in the substrate. Stallions with sore feet, especially front feet, benefit from a softer footing, particularly a soft landing during dismount. Heavy sod on well-drained soil is often the simplest and best outdoor footing. Composite rubber athletic surfaces, particularly if poured and seamless, make ideal breeding surfaces.

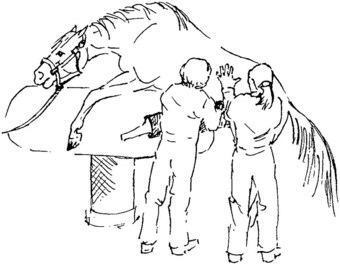

A stallion should be given ample freedom about the head, particularly during mounting and thrusting, to allow postural adjustments. Enforcing routines that work well for sound stallions, such as always keeping the head on the left side of the mare or dummy mount, may discourage a disabled horse. For severely ataxic, weak, or uncomfortable stallions, thrusting and ejaculation can be facilitated with gentle stabilizing assistance or spotting during breeding. We recommend an assistant apply gentle pressure with the hands on one or both hips to support the stallion from falling (Figure 127-2). Some stallions tolerate support from the rear, for example, with a wide strap held from either side behind the buttocks. Some resent this type of support, appearing to become trapped on the mare.

Gentle, guiding handling during dismount is important for all stallions but particularly for a disabled horse. For stallions with hindlimb weakness, pain, or incoordination, special consideration should be given to allowing the stallion as much recovery time as possible before dismount and to moving the mare slowly out from under the stallion rather than forcing the stallion to back off. Ataxic stallions that tend to step on themselves and the mare while breeding can benefit from simple, well-secured protective boots or wraps for themselves and the mare.

Monitoring Breeding Performance

Stallions with chronic musculoskeletal discomfort or disability usually deteriorate, and breeding performance should be monitored systematically so that adjustments can be made to maximize performance. A sensitive measure of improved comfort is the number, rhythmic pattern, and strength of pelvic thrusts from insertion to ejaculation. Normal, sound stallions typically require seven to nine thrusts at about 1-second intervals, with even sweep and strength, to ejaculate. The normal range of mount duration is 20 to 30 seconds, with insertion time 12 to 20 seconds. With discomfort, horses tend to require more thrusts, the sweeping pattern of the thrusts becomes less organized (irregular depth, rhythm, and strength), and the hindlimbs become more dancy as opposed to being planted with equal weight bearing on each. The head and ear positions of an uncomfortable stallion also suggest distraction (as if about to quit, fall, or dismount) as opposed to commitment. Horses with sore backs or necks tend to fail to couple closely. Thrusts may be jerky and shallow. Stallions with hindlimb neurological deficits may bear weight unevenly, become camped under, or become tipped toward the stronger side, with the weaker hindlimb dangling. They seem particularly unable to maintain lateral stability. We recommend developing a customized record sheet for daily grading of each abnormality. Videotaping each breeding from a direct lateral view that spans the entire mount and stallion and from the rear provides the most complete record.

One Mount Rule

For longevity of a disabled stallion through a season or through a breeding career, we recommend that ejaculation should be achieved with one mount. If a horse does not ejaculate in one or at most two mounts, the horse should be taken back to the stall or paddock to rest and return fresh. This strategy often effectively yields a greater number of successful mounts, provided that conditions are optimized for the first mount. The horse should be at the highest level of arousal possible for safe handling, the mount well positioned and optimally restrained if it is a live mare, the artificial vagina at optimum pressure and temperature for semen collection, and the handling team in top form and focused. If particular procedures or medications (see Box 127-1) are known to make the horse more comfortable, enhance libido, or reduce the ejaculatory threshold, we recommend using these from the start.

Ground Semen Collections

For stallions that breed by semen collection, a valuable alternative to mounting is ground semen collection. Most stallions with good to excellent libido are excellent candidates for semen collection while standing on the ground or even while supported in a sling. This technique is particularly useful in horses with aortoiliac thrombosis, cervical vertebral malformation, EPM, and other conditions with hindlimb instability or weakness.

Pharmacologically Induced Ex Copula Ejaculation

For stallions that breed by artificial insemination, pharmacologically induced (or chemical) ejaculation can be used with the stallion at rest in his stall. Currently the generally most effective treatment (50% to 70% of attempts) is a combination of imipramine hydrochloride administered orally about 2 hours before intravenously administered xylazine hydrochloride (see Box 127-1). For a particular stallion, best results can be achieved by titrating through a range of doses for each component drug.

Broodmare

Soundness of a broodmare is important for the demands of pregnancy and lactation and for ongoing comfort for normal expression of estrus behavior, willingness to stand for natural service when necessary, conception, and normal interactive maternal behavior.27 Diagnosis and treatment should not adversely affect fertility or the safety of the developing fetus, or nursing foal. As a population, broodmares tend to have a high rate of husbandry-related feet and limb problems. They may have old training or racing injuries. Broodmares coming and going tend to have herd social aggression and related injuries. Broodmares also suffer lameness secondary to foaling.

Specific Diagnostic Considerations and Therapy

Sore Feet

It is recommended that maiden mares should arrive on a breeding farm at least 8 to 10 weeks before the beginning of the breeding season. This allows time to assess and monitor condition of the feet and time for trimming as needed. Early arrival also affords time to acclimate the horse to the farm routine and social environment and for advanced photoperiod manipulation (under lights). Simple sore feet are a common problem in a maiden mare coming from the racetrack. The mare may have thin-walled feet and soles, underrun heels, long toes, bruised feet, quarter cracks, or corns. The mare may have been shod for a long time and not be accustomed to being barefoot. If sore feet are suspected as a cause of lameness, the feet should be examined with hoof testers. Baseline radiography may be indicated. Soaking, poulticing, sole painting, and the administration of phenylbutazone or flunixin meglumine (see Table 127-1) may be required for effective management of mares with foot soreness. Feet of broodmares should be trimmed every 6 to 8 weeks and ideally mares should be barefoot on all limbs and certainly for the hindlimbs.

A subsolar abscess is the most common cause of acute foot pain (see Chapter 28). Other causes include a sequestrum, laminitis, or a fracture of a palmar process of the distal phalanx. A sequestrum of the distal phalanx may be removed in a standing horse,28 eliminating the risks of general anesthesia for a developing fetus.

Laminitis

Acute or chronic laminitis can be a management problem in mares and may be secondary to pleuritis, diarrhea, severe lameness, or most commonly after foaling followed by a retained placenta (more common in draft breeds; see Chapter 125) or infectious metritis. Chronic laminitis also occurs in overweight mares, mares with a previous history of laminitis, or those that have ingested large amounts of feed or fresh pasture. Acute or chronic laminitis can have a negative effect on fertility secondary to pain.27

The treatment goals in broodmares with acute laminitis and chronic laminitis are similar to those described for the stallion. In our experience, some mares with chronic laminitis can be salvaged as successful broodmares with careful foot care, pain medication, good footing, separation from other broodmares and associated competition, and management similar to that described for the breeding stallion. In addition, some can conceive and deliver a normal foal, if these management techniques are successful. However, reproductive lives are often limited by laminitis.

Osteoarthritis

A broodmare with OA may need confinement to a stall or small paddock and analgesic medication (see Table 127-1). With severe OA of the fetlock or carpus, arthrodesis may be considered as a last resort in a broodmare that can no longer conceive or maintain a foal because of chronic pain.

Enlarged or Swollen Limbs

Palmar or plantar dermatitis of the pastern (scratches or mud fever) secondary to wet or muddy footing may cause lameness, particularly in hindlimbs. The mare should be removed from the wet area. Local therapy may be necessary, including washing, drying, and clipping the affected area and local application of a steroid/triple antibiotic topical ointment.

Lymphangitis is seen most commonly in the hindlimbs, is worse in later pregnancy, and causes reluctance to move, painful and pitting edema, and fever. Treatment includes stall rest, antibiotic therapy, and phenylbutazone.

A puncture wound and secondary cellulitis may cause lameness. Locating the original wound is often difficult. Aggressive antibiotic and antiinflammatory therapy is necessary. Additional treatment may include surgical drainage, hot packs, warm water hosing, and bandaging.

Hindlimb lameness may be associated with mastitis. The udder is painful to touch; the mare may not allow the foal to nurse; her appetite may decrease; and she may be febrile. Lameness resolves with symptomatic treatment of the mastitis.

Rhabdomyolysis

Acute rhabdomyolysis occurs occasionally in late gestation after particularly vigorous exercise. The mare may not come in for normal feeding or night stables and is often anxious, has a stiff walk, and may have dark-colored urine. Diagnosis is confirmed by measurement of serum creatine kinase levels. Treatment includes stall rest and NSAIDs. A mare with a foal at foot can be treated with the foal present.

Foaling-Related Injuries

Obturator nerve paralysis secondary to dystocia can result in mild to severe lameness. The mare may show difficulty in abducting the hindlimb and standing immediately after foaling. Femoral nerve paralysis secondary to dystocia results in inability to fix the patella and therefore the hindlimb. This is seen immediately after foaling. Symptomatic therapy for either condition includes NSAIDs, supportive therapy, nursing care, such as slinging if necessary, and adequate bedding and footing. The prognosis for full recovery is guarded, and a nurse mare may be needed for the foal.

Prepubic tendon rupture or ventral body wall hernias may occur during late gestation, apparently without reason. Ventral edema cranial to the udder is severe, unilaterally or bilaterally. An affected mare may have difficulty rising. It is difficult to obtain an accurate diagnosis until edema resolves after foaling. The body wall enlarges in the ventral flank. Diagnostic tests include palpation per rectum and ultrasonography. Occasionally, a tear in the ventral body wall can be palpated per rectum. Supportive treatment consists of NSAIDs, physical support of the enlarged area using large bandages, restricted exercise, close monitoring before and during foaling, a laxative diet, and assisted early induction of foaling. Successful surgical repair of ruptured prepubic tendons and large ventral body wall hernias is often unrewarding, but smaller defects can be repaired successfully. The prognosis for mares with large tears of a ruptured prepubic tendon and future use as broodmares is guarded to poor.29 Embryo transfer may be a reasonable alternative in breeds that allow this form of management (the Editors).

Neurological Disease

The most common neurological disease of adult broodmares in the United States is EPM. Cervical vertebral malformation also occurs and should be distinguished because treatment is different. Treatment for EPM is as for a stallion, but folate supplementation is not recommended in broodmares receiving pyrimethamine because of the potential alteration in organogenesis.30

Old Injuries

Many broodmares have old superficial digital flexor tendon or suspensory ligament injuries that may deteriorate, or mares may sustain acute reinjury. Aged broodmares may have gradual thickening and lengthening of the hindlimb suspensory ligaments. Broodmares with acute reinjuries are treated by restricted exercise, analgesia if needed, local therapy, and ultrasonographic monitoring. Stall confinement with daily handwalking may be needed for 3 to 4 months, depending on ultrasonographic evidence of healing. Treatment of mares with hindlimb suspensory desmitis with a dropped fetlock consists of strict stall confinement, pain medication if needed, and application of an extended heel, egg bar shoe. This shoe should be removed just before foaling for safety.

Occasionally, older broodmares develop extensive new bone, especially around the carpus, causing lameness. The mare should be separated from the normal herd to reduce competition for food and water, with restricted exercise and analgesia provided.

General Husbandry and Breeding Management Considerations

Simple management and handling may improve the comfort of an acutely lame broodmare and prolong the useful life of a chronically unsound broodmare. Attention to social groupings can reduce the chance of new injury and provide greater comfort for an older or lame broodmare. Many farms separate broodmares into compatible groups, including maidens, seasoned broodmares, barren mares, and older broodmares. The goals should be to limit competition for food and water and to minimize risk of encountering manufactured obstacles during aggressive interactions. Some farms follow a buddy system, in which compatible pairs are kept together as much as possible. Convalescent broodmares often do well grouped together for rehabilitation or special medical attention. Good footing, including breeding areas, pastures, alleyways, areas around hay bunks, loading ramps, and in stalls, can prevent injury and provide comfort for a lame broodmare. Broodmares benefit from as much exercise as possible to maintain overall good musculoskeletal fitness, and obesity should be avoided.

Phenylbutazone is the most commonly used drug for the effective pain management and has limited or no effect on organogenesis. Its use may be associated with gastric ulceration and concurrent treatment with omeprazole (4 mg/kg curative or 2 mg/kg preventative) may be of value, although any effects on organogenesis have not been reported.

Emergency surgery to repair a fracture may be necessary to save the life of the mare and fetus. Ideally a preformed plan should be in place, especially close to gestation. Is the decision to save the mare and the foal or to consider a nonsurvival cesarean section to deliver the foal? If the decision is made to proceed to save the mare and fetus, administration of synthetic progesterone (30 mg/kg PO twice daily) may be helpful, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy. Elective surgery should be delayed until the mare has foaled whenever possible.

For lame or otherwise disabled mares, artificial insemination should be considered whenever possible. For natural cover, we recommend excellent footing, a gentle approach, reduced restraint, and acute pain control. To reduce the stress in broodmares with pain, maiden mares, or broodmares with a known volatile live cover breeding history, the use of 25 mg of acepromazine and 10 to 25 mg of butorphanol given together intravenously 15 to 20 minutes before breeding may increase safety without the ataxia or sudden outbursts seen with xylazine administered alone. When possible, medication, including nutritional supplements, should be avoided during gestation and early lactation, including detomidine and xylazine used alone.