7 Treating muscles, fascia and myofascial trigger points

Myofascial pain is defined as pain arising from muscles or related fascia and comes from hyperirritable areas of muscle, ligaments and fascia known as myofascial trigger points (Bennett 2007). There are approximately 400 muscles forming the largest organ in the body amounting to approximately 40% of the body weight and there is no single medical specialty that is solely responsible for the study of their diagnosis and function. Myofascial trigger points have been associated with low back pain, neck pain, tension headaches, temporomandibular joint pain, forearm and hand pain and pelvic and urogenital pain syndromes in 44 million Americans and so a clinical practitioner in any specialty is likely to see patients with myofascial pain caused by trigger points (Borg-Stein 2006, Simons 1983, Fernandez-de-las-Penas 2006, 2007, Ardic 2006, Hwang 2005, Dogweiler-Wiygul 2004).

The first challenge for the practitioner is to recognize that myofascial trigger points may be causing the patient’s pain; the second challenge is to locate, effectively treat and eliminate myofascial trigger points as pain generators; the third challenge is to eliminate the factors in the patient’s biomechanics, physiology and lifestyle that perpetuate the myofascial dysfunction. Myofascial pain caused by trigger points must also be distinguished from the full body pain, central sensitization, sleep disturbances and neuroendocrine dysfunction characteristic of fibromyalgia.

Characteristics of myofascial trigger points

Active myofascial trigger points cause pain at rest, restrict muscle range of motion and have characteristic myotomal pain referral patterns that do not follow dermatomal nerve root patterns or scleratomal patterns emanating from joint structures. The original referral patterns were identified in the 1930s by injecting hypertonic saline into muscles (Kelgren 1938) and pain patterns for over 100 muscles have been documented in detail in the two-volume text, Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual (Travell 1983, 1992). Myofascial trigger points are found by gentle palpation across the direction of the muscle fiber to identify an indurated taut band of muscle and then specific palpation within the taut band to locate a painful nodule that feels like a hardened grain of rice or lentil. Firm pressure on the small nodule may cause the muscle to twitch and may recreate the patient’s pain complaint in the myotomal referral area. Latent myofascial trigger points have taut bands that are tender to touch and restrict range of motion but do not cause spontaneous referred pain.

Calcium release

Myofascial trigger points are thought to arise from focal injury to muscle fibers caused by trauma or overuse. Biopsies of myofascial trigger points reveal a cluster of numerous microscopic foci of sarcomere “contraction knots” that are scattered throughout the tender nodule (Simons 2001, Gerwin 2004). These contraction knots are thought to be caused by calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and are maintained by an “energy crisis” in the now hypermetabolic muscle once the constant contraction is initiated. Muscle contraction requires the energy of four ATP; muscle relaxation requires two ATP (Adenosine triphosphate, ATP, is the chemical energy that fuels all physical processes; Guyton 1996). Once facilitated, the motor endplates release increased amounts of acetylcholine to maintain the contraction, perpetuating the contraction knots and forming a self perpetuating cycle of activation, energy depletion and local metabolic stress (Mense 2003). Calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum becomes relevant for FSM treatment of trigger points because the frequency thought to “remove calcium ions” is one that softens the taut band and usually eliminates the trigger points.

Nerve sensitization

Persistence of the trigger point leads to neuroplastic changes at the level of the dorsal horn in the spinal cord, leading to central pain sensitization and expansion of the pain beyond its original boundaries into the referred pain area (Arendt-Nielsen 2003). The central neuroplastic changes account for the characteristic trigger point referral patterns. Neuropathic pain sensitization at the level of the nerve root and the spinal cord accounts for the pain intensity seen during stimulation of the trigger point that often appears disproportionate to the stimulus (Curatolo 2006). The twitch response that occurs when the muscle is stimulated is a spinal reflex that can be abolished by transection of the spinal nerve that innervates the trigger point (Hong 1994, 1996).

The local biochemical milieu in an active trigger point is different from that of normal muscle fibers or latent trigger points. A microdialysis needle was used to take constant stream samples of the biochemical environment within an active trigger point before, during and after a twitch response and compared it to normal muscle and latent trigger points. Active trigger points show significantly elevated levels of the inflammatory peptides TNF-α, Interleukin-1(IL-1), calcitonin-gene-related-peptide (CGRP), substance P, bradykinin, serotonin, and norepinephrine (Shah 2005). Early biopsies of trigger points showed mast cells degranulating releasing histamine into the area around the trigger point (Simons 1983). The neural component of trigger point pain and perpetuation is relevant to FSM treatment because the most effective treatment protocols have evolved to include treating “inflammation in the nerve and the spinal cord” first with the FSM treatment protocols known to reduce inflammatory cytokines (McMakin 2005).

Treating myofascial trigger points

There is no form of drug therapy that alleviates myofascial trigger point pain or muscle dysfunction. Trigger point injections with saline and 1% lidocaine or procaine or dry needling are considered to be the most effective therapy but require a skilled well trained therapist to precisely localize the active trigger point by identifying a local twitch response in the taut band. Studies have shown problems with localizing the taut band and the active trigger point (inter-rater reliability) between therapists depending on their skill and training (Gerwin 1997, Hsieh 2000, Sciotti 2001). Needling or injection of single active trigger points limits effectiveness in muscular areas populated by multiple active, latent and satellite trigger points. Full length stretching of the muscle while using an ethyl chloride vapocoolant spray, called “spray and stretch”, disrupts the focal contractions and stops the prolonged ATP consumption that perpetuates the contraction knots. Not all muscles are suitable for this intervention and environmental considerations have reduced its use in recent years. Postural and ergonomic corrections to modify factors that perpetuate trigger points are critical to successful management.

Diagnosing myofascial pain

Any patient who presents with a chronic pain complaint should have a focused neuromuscular evaluation that includes evaluation of reflexes and sensation and a palpatory evaluation to check for taut bands and myofascial trigger points. There are wall charts and diagrams in text books that illustrate the referred pain patterns for specific muscles (Travell 1983, 1992, Niel-Asher 2008). The diagrams give guidance as to what muscles are likely to be a source of the referred pain in a given area. The practitioner should match the patient’s area of complaint with the pain patterns in the diagram and then check the muscles that refer pain to that area. Palpation of a taut band and the small painful nodule that is the trigger point, pressure on the nodule that reproduces the patient’s pain and restricted range of motion due to muscle tightness are all diagnostic of an active myofascial trigger point.

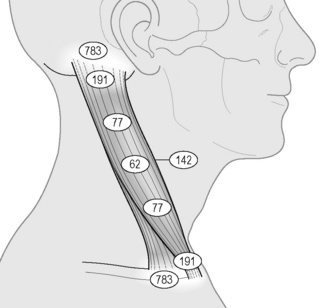

Figure 7.1 • Myofascial trigger points refer pain to sites distant from the source of the pain in distinct patterns that do not follow dermatomal or scleratomal referral patterns. Pain in the arm, shoulder or hand may originate with a trigger point found in the anterior scalenes. The trigger points in the scalenes may in turn be a result of a disc injury or overuse caused by poor posture.

History of causation consistent with myofascial trigger points

The patient should have some history of overuse or trauma that would account for the formation of a myofascial pain problem. Chronic postural strain, repetitive muscle use, degenerative joint and disc disease, acute disc injuries, food allergies and other inflammatory conditions and emotional stress are among the conditions that contribute to trigger points. Look for some temporal association with activities or events and the onset of pain. If the pain started around June of 1999, ask what was happening in May of 1999.

Physical examination

Physical examination should include deep tendon reflexes, a dermatomal sensory examination and palpation of the muscles suspected to be the source of the pain. The presence of dermatomal hyperesthesia or numbness, or hyper or hypoactive reflexes suggests neuropathic involvement that may influence treatment.

Myofascial palpation should be guided by the patient’s pain diagram and description. If the patient locates the pain at the “shoulder” the 12 muscles that can refer pain to the shoulder should be evaluated for the presence of taut bands and active and latent trigger points. Sustained pressure on the trigger point may reproduce the patient’s pain but a trigger point that is already maximally referring may not increase its referral in response to pressure. Detailed descriptions and advice on how to conduct a myofascial palpatory examination are beyond the scope of this text but the reader is encouraged to pursue training in this skill.

The discs and facet joints should be considered and examined because myofascial trigger points can be created by and perpetuated by degenerative joint and disc disease and can in turn exacerbate degenerative joint disease when the taut muscle compresses the spinal segment.

Myofascial trigger points can create abnormal biomechanics in the peripheral joints – the shoulder, the elbow, the hip, the knee and even in the wrist and ankle when taut bands interfere with optimal joint motion. Conversely, inflammation in the peripheral joints, tendons and bursa can create muscle guarding and tightness that leads to taut bands and active trigger points. The dysfunction forms a feed forward and feedback cycle that perpetuates both the joint inflammation and the myofascial trigger points.

A visceral examination or abdominal palpation may be necessary if the patient has myofascial trigger points created by gastrointestinal or gynecological organ referral.

Treating myofascial trigger points with FSM

FSM was first used to successfully treat myofascial trigger points in 1996 and the first two articles published were collected case reports showing successful pain resolution in trigger points in the head, neck and face pain and in low back pain (McMakin 1998, 2004). FSM provides microamperage current known to increase ATP production by 500% in rat skin (Cheng 1982). The current alone would address the energy crisis that perpetuates the contracture knots allowing the knots to release by increasing ATP.

The frequencies used to “reduce inflammation in the nerve” have been shown to decrease inflammatory cytokines including IL-1, CGRP, substance P and serotonin – demonstrated by Shah to be increased in the active trigger point milieu (McMakin 2005, Shah 2005). FSM has been shown to down regulate spinal cord activation and reduce central sensitization in the treatment of fibromyalgia associated with spine trauma and could reasonably be assumed to perform the same function to reverse the central neuroplastic changes seen in myofascial pain. The observed effects of muscle softening, relaxation of the taut band and resolution of the trigger point occur as a response to specific frequencies meant to reduce inflammation in the nerve and reduce calcium ion deposits in the fascia. It is reassuring that these frequencies coincide with the pathologies now known to be associated with myofascial trigger points.

When FSM is used to treat myofascial trigger points the positive pair of electrodes are applied at the spine where the relevant nerve root exits and the other pair is applied at the end of the dermatomal nerve supplying the muscles being treated. The current flows through a regional area of biomechanically and neurologically related muscle tissue. The treatment does not require precise localization of the taut band or active trigger point which eliminates the reliability problems that have plagued dry needling and injection trigger point treatment methods and allows successful treatment by less skillful clinical assistants. The treatment can be applied to any muscle or muscle group and has no known negative environmental impact which gives it a distinct advantage over vapocoolant spray and stretch technique. When the dysfunctional muscle is treated at the same time as its related agonist and antagonist muscles in a functional region it provides biomechanical balance that enhances recovery and return to function.

The treatment is pain free, low risk and non-invasive and produces rapid reduction in pain giving it a distinct advantage over other methods in the treatment of myofascial trigger points.

Treating chronic myofascial pain and trigger points

Treatment of myofascial pain and trigger points has been developed over 12 years of clinical experience and literally tens of thousands of patient treatments. The protocols have become so predictably effective that the response to treatment can be used diagnostically.

The myofascial protocol has three parts. It starts with the frequencies to treat the nerve then moves to the frequencies to treat the muscle and then to the frequencies to treat the facet joint, the disc or the peripheral joints that might be instigating or perpetuating factors. This treatment is so consistently effective that if it does not eliminate the taut band and reduce the pain then some visceral source for the trigger points should be considered.

• The patient must be hydrated to benefit from microcurrent treatment.

• Hydrated means 1 to 2 quarts of water consumed in the 2 to 4 hours preceding treatment

• Athletes and patients with more muscle mass seem to need more water than the average patient.

• The elderly tend to be chronically dehydrated and may need to hydrate for several days prior to treatment in addition to the water consumed on the day of treatment

• DO NOT accept the statement, “I drink lots of water”

• ASK “How much water, and in what form, did you drink today before you came in?”

• Coffee, caffeinated tea, carbonated cola beverages do not count as water.

Channel A: condition frequencies

The frequencies listed are thought to remove or neutralize the condition for which they are listed except for 81, 49 / which are thought to increase secretions and vitality respectively. They are listed alphabetically and not in order of use or importance.

| 91 / | |

| 284 / | |

| 40 / | |

| 13 / | |

| 3 / | |

| 81 / | |

| 49 / |

Channel B: tissue frequencies

Neuropathic component

Dermatomal nerve roots become inflamed and sensitized from constant input by the contracting myofascial tissue or from a nearby disc injury. The disc nucleus contains very concentrated levels of the inflammatory substance phospholipase A2 (PLA2). When the annulus is damaged by trauma or postural strain it allows diffusion of small amounts of PLA2 to the nerve. This concentration is sufficient to cause nerve inflammation and muscle hypertonicity but insufficient to cause a classic dermatomal neuropathy.

Dermatomal nerve roots become inflamed and sensitized from constant input by the contracting myofascial tissue or from a nearby disc injury. The disc nucleus contains very concentrated levels of the inflammatory substance phospholipase A2 (PLA2). When the annulus is damaged by trauma or postural strain it allows diffusion of small amounts of PLA2 to the nerve. This concentration is sufficient to cause nerve inflammation and muscle hypertonicity but insufficient to cause a classic dermatomal neuropathy.Myofascial component

The fascia is the thin connective tissue covering surrounding the muscles and all soft tissues. The fascia becomes inflamed, calcified and fibrosed during the degenerative process.

The fascia is the thin connective tissue covering surrounding the muscles and all soft tissues. The fascia becomes inflamed, calcified and fibrosed during the degenerative process.• Artery and Elastic Tissue in the Muscle Belly: __ /62

62 is the frequency used for the artery and the elastic tissue in the arterial walls. The muscle belly responds to this frequency either because it is full of small arteries or because the elastic tissue in the muscle belly is somehow related to the artery wall.

62 is the frequency used for the artery and the elastic tissue in the arterial walls. The muscle belly responds to this frequency either because it is full of small arteries or because the elastic tissue in the muscle belly is somehow related to the artery wall. Fine neural fibers travel between layers of fascia in a fascia–nerve–fascia sandwich to innervate the muscles. Constant contractures and local metabolic dysfunction create inflammation at the site of the trigger point. Inflammation leads to calcium influx and fibrosis. Fibrosis between the nerve and fascia restricts movement, creates neuropathic pain and muscle activation when the nerve is stretched as the fascia moves. Calcium ions flow into the nerve when it is inflamed and change the firing threshold.

Fine neural fibers travel between layers of fascia in a fascia–nerve–fascia sandwich to innervate the muscles. Constant contractures and local metabolic dysfunction create inflammation at the site of the trigger point. Inflammation leads to calcium influx and fibrosis. Fibrosis between the nerve and fascia restricts movement, creates neuropathic pain and muscle activation when the nerve is stretched as the fascia moves. Calcium ions flow into the nerve when it is inflamed and change the firing threshold.Joint component – facet joints, discs, and peripheral joints

The periosteum lines the outside of the bone, interweaves with tendinous and ligamentous attachments and is very pain sensitive. Inflammation and calcification in the periosteum are the most common chronic pain generators in facet and peripheral joint pain.

The periosteum lines the outside of the bone, interweaves with tendinous and ligamentous attachments and is very pain sensitive. Inflammation and calcification in the periosteum are the most common chronic pain generators in facet and peripheral joint pain. The joint capsule attaches to the periosteum, surrounds the joint and becomes fibrosed, calcified, scarred and inflamed when damaged by trauma or chronic mechanical stress.

The joint capsule attaches to the periosteum, surrounds the joint and becomes fibrosed, calcified, scarred and inflamed when damaged by trauma or chronic mechanical stress. Cartilage lines the facet and peripheral joint surface and becomes damaged, degenerated, calcified and inflamed when traumatized by acute or chronic compression of the joint surface (see Chapter 6: Treating Facet Joint Pain).

Cartilage lines the facet and peripheral joint surface and becomes damaged, degenerated, calcified and inflamed when traumatized by acute or chronic compression of the joint surface (see Chapter 6: Treating Facet Joint Pain). The disc annulus wraps around and contains the nucleus and is very well innervated and pain sensitive. It is the most common pain generator in chronic discogenic pain and in mild acute disc injuries that would create myofascial trigger points (see Chapter 4: Treating Discogenic Pain).

The disc annulus wraps around and contains the nucleus and is very well innervated and pain sensitive. It is the most common pain generator in chronic discogenic pain and in mild acute disc injuries that would create myofascial trigger points (see Chapter 4: Treating Discogenic Pain). The gel like disc nucleus fills the center of the disc and absorbs water to become a cushion for the vertebral bodies in the spine. It is very high in PLA2 and very inflammatory.

The gel like disc nucleus fills the center of the disc and absorbs water to become a cushion for the vertebral bodies in the spine. It is very high in PLA2 and very inflammatory.These frequencies were discovered in a list of frequencies published by Albert Abram’s in Electromedical Digest in 1931. 58 / 00 was the frequency combination to remove “abnormal cellular stroma”, probably meant to address the tendency of the cell to form scar tissue. 58 / 01 was used for scar in bony tissue. 58 / 02 was used for scar in soft tissue and 58 / 32 was used for scar tissue adhesions. When there is no bone involved 58 / 01 is not used. These are A/B pairs in which channel A is not a condition and channel B is not a tissue but both frequencies form a frequency pattern that appears to eliminate or lengthen scar tissue.

In treating chronic complaints the 58/’s are used in order as listed above for approximately 1 to 2 minutes each at the beginning of the treatment to soften the tissues. If there is no bone involved in the complaint it is customary to leave out 58 / 01. For those practitioners who can feel the softening produced by the frequency, it is often helpful to run the frequency until the softening stops and the tissue becomes relatively more firm. There may be some patients in whom one or more of these frequencies will produce softening for up to 3 to 4 minutes.

The 58/’s will increase range of motion but do not change pain.

Caution: 58 / 00, 01, 02, 32

• Do not use these frequencies on injuries newer than 5 to 6 weeks old.

• Newly injured tissue must form scar tissue in order to repair itself.

• Removing the scar tissue seems to undo the healing by weeks in a new injury.

• The 58/’s can be used very briefly (15 seconds) to modify scar tissue as it is forming after the first four weeks.

• Never use this combination before the injury is 4 weeks old

This precaution is the result of trial and uncomfortable error. A patient was being treated for facet joint and soft tissue injuries caused by an auto accident that had occurred 3 weeks previously. She was pain free after four treatments in 21 days and was treated on a Tuesday. She returned on Thursday complaining that whatever had been done on Tuesday had “undone” 2 weeks worth of healing and she felt as much pain as she had 2 weeks previously. Review of the Tuesday treatment notes revealed that the 58/’s had been used in addition to the protocols that had been reducing the pain for the preceding three weeks. She was so much improved that it seemed as if the injury was much older and the date of injury was not checked before treatment. When the symptoms increased the presumption was made that the 58/’s had removed repair tissue necessary to keep the joint and soft tissues pain free and stable. Treatment with frequencies to reduce inflammation and increase collagen eliminated her pain and she recovered as expected. The 58/’s were used again 4 weeks later to increase range of motion and there was no increase in pain.

Trial and error during the first year of treating with FSM in similar situations helped to determine that the 58/’s should not be used within 5 to 6 weeks of a new injury. They can be used briefly four weeks after the date of injury – for 5 to 10 seconds each – to thin out scar tissue as it is forming, especially in athletes who seem to heal faster than non-athlete patients. This reaction is predictable and reproducible. Take this precaution seriously.

Treat the nerve

Nerve protocol

40 / 396

• Reduce Inflammation in the nerve.

• Polarize current positive +.

• Treatment time: 5 minutes or as long as positive response occurs.

• The protocol to reduce inflammation in the nerve usually begins softening the muscles between the two contacts within one minute. At the end of 5 minutes the softening should have maximized and achieved whatever reduction in neural inflammation or sensitization that can be accomplished.

40 / 10

• Reduce inflammation in the spinal cord.

• Polarize current positive +.

• Treatment time: 2 minutes or as long as positive response occurs.

• The protocol to reduce inflammation in the cord is especially helpful in treating muscles in the cervical spine and shoulder that are especially tight bilaterally and seems to address spinal cord sensitization and upregulation. If this frequency combination is going to produce additional softening of the muscles it will do so within the first 2 to 3 minutes. If no change in muscle tone or texture becomes apparent in that time, change frequency to the next in the protocol. If the muscle softens in response to this frequency, the frequency combination can be used until no further softening is perceived which may take up to 5 to 10 minutes depending on the patient.

• Predicted Response: The frequencies for inflammation in the nerve and cord cause muscle relaxation in more than 80% of patients treated. As this response begins, use the manual techniques described below and wait for the tissue to stop softening before changing to the muscle protocol.

If there is dense scar tissue or bony stenosis of the nerve root or spinal cord or if a disc fragment is compressing the nerve root or cord at the involved level the patient’s pain may increase when polarized positive current is applied. It is the only time the pain will increase during polarized positive treatment for nerve inflammation. It may increase in the dermatome or at the spine or both.

Stop treating immediately if pain goes up during treatment. Move the patient to a seated position if possible. Move the contacts slightly up the spine superior to the nerve root being treated, reduce current levels and change the current from polarized positive to alternating. If this is going to reduce the reaction it will do so in 5 to 10 minutes. If the pain continues to increase, stop treating with current. The pain should go back down in a few hours although it may take up to 24 hours to reduce to base line.

This reaction is diagnostic. If physical examination findings of reduced sensation and deep tendon reflexes at the involved level or hyperactive deep tendon reflexes below the involved level are present this reaction suggests the need to x-ray or perform an MRI to confirm the presence of compression.

Treatment application

Lead placement: manual therapy

• The positive leads from channel A and channel B are placed in one glove.

• The negative leads from channel A and channel B are placed in the other glove.

• The two gloves will always be on opposite sides of the body part being treated during manual treatment of trigger points and myofascial tissue. The required interferential field forms in the space between the two gloves which should include the tissue being treated. The polarized positive current used with 40 / 396, 10 relaxes the tissue even if the contacts are not set up proximal distal.

• Positive leads: The positive leads are wrapped in or attached to a warm wet contact, such as a hand towel or long graphite electrode that is wrapped around the neck or placed along the spine where the nerve roots exit that innervate the involved muscle group.

• Negative leads: The negative leads are wrapped in or attached to a warm wet fabric contact or long graphite electrode that wraps around the end of the nerve root at the distal end of the muscle group to be treated.

Adhesive Electrode Pads may be used for convenience although the gloves seem to be more effective for reasons not understood. The adhesive electrode pads are especially useful for home treatment because they allow the patient to be active while being treated. The pads become “prickly” or sting when current levels are above 150μamps so may not be useful for larger patients or athletes.

When applying treatment with adhesive electrode pads, the current and the frequencies must pass through the area to be treated in an interferential pattern, forming an “X” in three dimensions. The positive electrodes are placed at the spine at the level of the disc to be treated. The negative electrodes may be placed directly anterior or anterior and slightly inferior to the spinal contacts if the disc alone is being treated or if the nerve is to be treated the negative electrodes may be placed at the ends of the nerve root affected by the injured disc.

A diagram for the placement would look like this:

| Positive Electrode Channel A | Positive Electrode Channel B |

| Area to be Treated | |

| Negative Electrode Channel B | Negative Electrode Channel A |

Manual therapy between the contacts: The practitioner’s hands can palpate, mobilize, and manipulate the myofascial tissue as it is treated by the current and frequencies being delivered by the stationary contacts. There should be some interference to prevent current flow through the practitioner. Latex or nitrile gloves can be worn on the hands or even on one hand to block the current or some form of massage oil can be applied lightly on the hands to serve as an insulator. Follow the directions for manual technique covered below.

Current level

• Average patients require 100–300μamps. Use lower current levels, 20–60μamps, for very small or debilitated chronically ill patients. Use higher current levels, 300–500μamps, for larger or very muscular patients. In general, higher current levels reduce pain and create softening more quickly. Do not use more than 500μamps as animal studies suggest that current levels above 500μamps reduce ATP production (Cheng 1982).

• Note: Current levels over 150μamps make it difficult to use the graphite gloves directly on the skin because they dry out quickly and the current becomes uncomfortable easily. It becomes cumbersome and tedious to continually moisten the graphite gloves. If higher current levels are required due to the patient’s size using wet towel contacts is recommended.

Waveslope

• Use a moderate to sharp waveslope with a ramped square wave pulse.

• The waveslope refers to the rate of increase of current in the ramped square wave as it rises from zero up to the treatment current level every 2.5 seconds on the Precision Microcurrent and the automated family of FSM units. Other microcurrent instruments may have slightly different duty cycles and the waveslope may be different but any unit which provides current flow with a square wave pulse should produce the desired effect. A sharp waveslope has a very steep leading edge on the square wave indicating a very sharp increase in current. A gentle waveslope has a very gradual leading edge on the waveform indicating a gradual increase in current.

• Use a moderate to sharp waveslope for chronic pain. Use a gentle waveslope for new injuries. A sharp waveslope is irritating in new injuries.

• Different microcurrent devices may provide different wave shapes and waveslopes but the reader may find them to be equivalent.

Manual technique: let the frequencies and current do the work

For those trained in manual therapies treating the muscles while using FSM requires some adjustment of technique. The key is to let the frequency do the work and to use the hands with gentle but firm pressure and minimal muscle contraction allowing maximal sensitivity to the softening affect created by the frequencies. The hands should lie gently on the skin allowing the pads of the finger tips to glide across the muscle. Ideally the hands will be almost limp with just enough tone in the distal finger muscles to allow the finger pads to gently assess the state of the tissue. This gentle touch allows the muscles being examined to relax and avoids the resistance created by overly aggressive palpation. The therapist may use body weight translated through the shoulder muscles and serratus anterior to advance the arm and increase the pressure of the hand and finger pads rather than use tension in the forearm and finger flexors to increase pressure.

The hands are sensing the change and softening in the muscles being created by the current and frequencies and helping it along but not forcing it. The frequencies will create the desired change of state in the muscle; it is not necessary to use force. The patient’s muscles will relax and allow deeper palpation if the practitioner’s hands are relaxed and will defensively tense if the contact is too firm or if the palpating fingers are too tense.

Move the fingers slightly every two to three seconds across the region, using gentle but firm pressure and a gentle pulling motion as if trying to warm, soften and elongate a piece of nougat or soft taffy. Pressure can be directed both along and across the muscle fiber direction. A gentle kneading motion is sometime effective. Small circular scrubbing motions are less effective and should be avoided especially in the anterior cervical spine near the sensitive baroreceptors and neurovascular structures.

Manual myofascial therapy using graphite gloves

• See Figures 7.2 to 7.9.

Figure 7.2 • A latex or nitrile glove is worn under the graphite glove to block current conduction to the practitioner. The graphite conducting gloves are placed on the practitioner’s hands over the insulating glove. Two positive leads are connected to one glove, usually the right. Two negative leads are connected to the other graphite glove. The interferential field where the current and frequencies mix is created between the two gloves.

Figure 7.3 • The graphite glove must be moist or wet to conduct current comfortably. The gloves may be sprayed with water at regular intervals during the treatment. Or the practitioner may dip the fingers of the graphite glove into a small plastic dish at regular intervals, usually when a frequency is changed or when the patient complains of a prickling or stinging sensation when the gloves become dry. It is best to avoid the stinging by wetting the gloves at regular intervals before they become dry.

Figure 7.4 • The starting position for the manual treatment of the cervical spine with the practitioner wearing the graphite gloves is shown. RELAX the wrists and lay backs of the wrists on the treatment table. RELAX the fingers and raise them so the pads of the finger tips contact the skin in the suboccipital area. DO NOT let the graphite gloves touch the patient’s ears as this will conduct current through the brain.

Figure 7.5 • Keep one hand still at the sub-occipitals. Bring the other hand around the neck, under the ear, and just below the jaw, allowing the finger tips to glide over the skin, Let the finger tips glide over the skin moving several centimeters at a time, not breaking contact but gliding in a smooth motion applying gentle pressure, moving the finger tips every 2 to 3 seconds. The fingers are sensing change rather than forcing it, inserting themselves gently in between adhered tissues as they soften and separate. The contact can become more firm as the tissues become very soft, later in the treatment.

Figure 7.6 • Using the same smooth gliding gentle pressure move the finger tips down the anterior cervical spine. Move the fingers every 2 to 3 seconds, not breaking contact with the skin, using gentle relaxed finger tip pressure to sense the changes being created. Do not “scrub” using little circles; this movement is annoying to the patient and can have inconvenient effects if done over the carotid sinuses. If the tissue is softening and time allows, stay on the frequency that is producing softening changes. If 1 to 2 minutes have passed and no changes have occurred, change to the next frequency on the list. When the gloves are lifted off the patient’s skin to change the frequency, it is a good opportunity to wet the gloves by spraying them with water or by dipping them in a small water dish.

Figure 7.7 • Relax the fingers and the wrists so they can change orientation easily and move comfortably around the supraclavicular space towards the muscles, discs, and facet joints of the posterior cervical spine. Keep the fingers relaxed and the pads of the fingers placed with gentle and firm upwards pressure. Move the fingers, gliding the fingers with gentle firm pressure every 2 to 3 seconds, up the posterior cervical spine towards the occiput. As the hand is being moved the frequencies are being changed every 1 to 3 minutes.

Figure 7.8 • As the fingers move up the posterior cervical spine the soft tissues should be softening, especially after the second or third circuit. The softening of the superficial fascia allows easy palpation of the facet structures and makes the taut bands containing trigger points or fibrosis stand out against the “smooshy” relaxed superficial tissues. The amount of cervical rotation is exaggerated for photographic clarity; the neck should be slightly rotated and each segment is rocked from side to side as facet joint tissue frequencies are used.

Figure 7.9 • Place the hand that just finished the circuit of one side of the cervical spine at rest at the suboccipital muscles. Move the other hand down the neck, under the jaw, down the anterior cervical muscles, around the supraclavicular space to the posterior cervical muscles and facet joints.

Box 7.1 Technique for treating the cervical muscles

Box 7.1 Technique for treating the cervical muscles

• RELAX the wrists and lay backs of the wrists on the treatment table.

• RELAX the fingers and flex them gently so the pads of the finger tips contact the suboccipital muscles.

• GLIDE them across the skin to contact the other muscles.

• DO NOT let the graphite gloves touch the patient’s ears as this will conduct current through the brain.

• DO NOT “scrub” or apply prolonged directed pressure over the carotid sinuses

Treat the muscle

58 / 00, 02, 32

• Remove scarring and adhesions from soft tissues and reduce the tendency to create scar tissue. These frequencies will produce the most pronounced change in tissue texture if the muscle has been injured by trauma.

• Polarize current positive + or alternating ± (see note below*).

• Treatment time: Use each frequency for 1 to 2 minutes each or as long as positive softening response occurs.

• If fibrosis or adhesions are involved in the muscle dysfunction the frequencies will begin to soften the muscle within the first minute. Use each frequency for 1 to 2 minutes. If the practitioner is sensitive and can feel the softening in the muscle, the frequency can be used for as long as it is producing changes in muscle texture or discontinued as soon as the softening stops even within seconds. If there has been significant muscle trauma from an accident, a crush injury or surgery each one of the 58/’s may produce softening for up to 5 or 10 minutes each. If there has been no muscle damage the frequency will have virtually no effect on muscle texture and may be useful for only a few seconds.

• Application: The lead placement, current level and waveslope do not change for the muscle portion of the treatment protocol.

• *Current Polarization May Change: Current polarization may change for the muscle portion of the treatment. For reasons that are not understood, about one half of patients treated will respond best if the current remains polarized positive during the muscle portion of the myofascial protocol and one half will respond best if the current is changed to alternating. If the patient responds to one or the other polarization while the 58 / 00, 02, 32 frequencies are being used then that polarization is to be used for the remainder of the treatment.

91 / 142, 62, 396, 77, 191, 783

• Remove calcium and hardening from the fascia, the muscle belly elastic tissue, the interfascial nerve fibers, the connective tissue, the tendons and the periosteum where the tendon attaches.

• Treatment time: Use each frequency for 2 to 4 minutes each.

• This frequency will produce softening in myofascial tissue. 91Hz may be used with each tissue frequency for 2 to 4 minutes each in a manual microcurrent unit (one that allows manual selection of a three digit frequency) or in a unit that automatically changes frequencies after a set time interval of 2 minutes. If a manual microcurrent unit is being used and the practitioner is sensitive to the softening in the muscle, the frequency can be used for as long as it is producing changes in muscle texture. The tissue response may last for up to 5 or more minutes depending on the patient and the chronicity. Athletes with myofascial dysfunction respond very well to 91Hz and it may produce softening for up to 5 to 10 minutes with certain tissues.

Manual technique – place the fingers on the tissue type being treated

The tissues treated respond very specifically to the frequency. Gentle manual pressure at the tissue being treated seems to assist the frequency effect. For example, when the “fascia” is being treated with 91 / 142 placing the fingers where the fascia is known to be most dysfunctional or hardened and gently separating the fibers as they soften will speed the softening process. When the muscle belly is being treated with 91 / 62 placing the fingers at the muscle belly and using them to follow the softening will assist the changes and allow more detailed assessment of them.

Figure 7.10 • When using a frequency to address a certain tissue place your fingers where you know that tissue to be. In the example above the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle has a tendon (191) that attaches to the periosteum (783) at the mastoid process behind the ear. The tendon gives way to the fibrous distal end of the muscle, which contains a higher percentage of connective tissue (77) than the more central muscle belly (62). The muscle cross-section thins out again as it moves toward the distal attachment and once again contains a higher percentage of connective tissue (77) which coalesces into the tendinous attachment (191) at the periosteum (783) of the sternum and clavicle. The fascia (142) covers the entire muscle. Begin to think of anatomy as tissue types. Use a visual anatomy reference such as Netter (1991) and move your fingers to where you know these tissues to be.

The small interfascial nerve fibers that run the length of the muscle between the fascial layers are probably most affected at the motor end plates. As this tissue is being treated with 91 / 396 allow the fingers to find the areas of softening and gently probe them. Connective tissue (77) runs throughout the muscle but is a proportionally greater portion of the structure near the tendinous portion of the muscle. Focus manual pressure at the part of the muscle where connective tissue is most concentrated while using 91/77.

Tendinous trigger points are usually the last to disappear and respond well to manual pressure directly on the tendon during treatment with 91 / 191, 195. Tendons interweave with the periosteum at their attachment and this junction becomes painful from the constant tension of the taut and shortened muscle band. The tender nodule on the periosteum usually softens and appears to “melt” when 91 / 783 is applied.

To enhance the process of treating specific tissues the practitioner can envision the familiar anatomy as tissue types. For example from an anatomical perspective the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle has its origin on the mastoid process and its insertion at the clavicle and sternum creating cervical flexion and contralateral rotation when activated. From a “tissue type” perspective the SCM attaches tendon (/ 191) to periosteum (/ 783) at the skull, becomes concentrated connective tissue (/ 77) just distal to that attachment and then becomes predominantly fascia (/ 142) that envelops the elastic muscle belly (/ 62) and the neural motor endplates (/ 396). From midline to distal attachment the connective tissue becomes more pronounced leading into the tendon that attaches again to periosteum.

For the practitioner who has less training in palpation or anatomy, the hands may simply traverse the area being treated and apply pressure to the tissues that are softening in response to the frequency being used. Use of an illustrated anatomy text, such as Netter’s Illustrated Atlas that provides a detailed visual reference for location of tissue types within the muscles speeds up the learning process for the manual therapist (Netter 1991).

13 or 3 / 142, 62, 396, 77, 191, 783

• Remove scarring or sclerosis from the fascia, the muscle belly elastic tissue, the interfascial nerve fibers, the connective tissue, the tendons and periosteum.

• These frequencies will produce the most pronounced change in tissue texture if the muscle has been injured by trauma or physical injury.

• Treatment time: Use each frequency for 1 to 2 minutes each.

• 13Hz: If fibrosis or adhesions are involved the 13Hz will begin to soften the muscle within the first minute. Use 13Hz for 1 to 2 minutes with each tissue. If the practitioner is sensitive and can feel the softening in the muscle, the frequency can be used for as long as it is producing changes in muscle texture or discontinued as soon as the softening stops even within seconds. If there has been significant muscle trauma from an accident, a crush injury or surgery or if the muscle dysfunction is very chronic, 13Hz will produce pronounced softening in the area of the muscle most injured. Athletes respond particularly well to 13Hz in most tissues treated.

• 3Hz: It is virtually impossible to verbally describe the difference between the changes created by 13Hz as compared to those created by 3Hz. Tissue affected by “sclerosis” feels stiffer, stringier and tighter to palpation before treatment than tissue more likely to respond to “scar tissue” or 13Hz. Ultimately, “sclerosis” is what goes away when the frequency 3Hz is used and “scar” is what goes away when the frequency 13Hz is used. The timing for 3Hz will be similar to that described above for 13Hz if the tissue responds to it by softening. Use one or both frequencies and compare their effects; they will be slightly different depending on the patient’s physiology, the history of injury and the chronicity. One is usually more effective than the other in a given patient and each produces a distinct change in tissue texture.

81, 49 / 142

• Support secretions and vitality in the fascia.

• If the muscle is completely soft and pain free and in the unlikely event that there is no spinal or peripheral joint involvement, the treatment should be finished at this point. The fascia secretes ground substance that helps repair itself and the associated tendons and connective tissue and clinical use of 81 / 142 suggests that this frequency pair stimulates and supports this process.

• Treatment time: Use each frequency for 2 minutes each.

• There is no specific manual technique required while these frequencies are being used although it is interesting to feel the tissue change texture as these frequencies are having their effect.

Treat the joint

In most cases of myofascial pain there is some dysfunction in the spinal discs or facet joints or the peripheral joints associated with the formation or perpetuation of myofascial trigger points. The joint dysfunction may be a cause of the trigger points or its result. Comprehensive treatment requires that the joint component be addressed.

Figure 7.11 • Place the positive leads glove in a warm wet fabric contact (hand towel) that is wrapped around the neck. This allows all of the cervical nerve roots and the spinal cord to be treated. Place the negative leads glove in a warm wet fabric contact (hand towel) that is draped across the lateral thoracic spine, across the lower scapula, along the lateral chest wall, under the axilla and around the upper arm. This placement allows all of the cervical nerves, all of the brachial plexus and all of the muscles of the cervical spine and shoulder to be treated simultaneously. Move the hands every 2 to 3 seconds using the finger pads with relaxed fingers to assess and treat any muscle. Move the hands under the towels to treat the anterior and posterior cervical muscles (scalenes, SCM, trapezius), the subscapularis, the infraspinatus, the serratus anterior, the levator scapulae. Even the pectoralis muscles can be addressed by reaching forward under the shoulder. Block the current from flowing through the practitioner by using a latex glove or some sort of oil on the hands. Do not get oil on the graphite gloves as it ruins their conductivity.

Treat the disc

40 / 710, 630, 330

• Remove inflammation from the spinal discs: the annulus, the disc as a whole and the nucleus pulposus. 40 / 710 will produce the most noticeable softening in the surrounding fascia if the disc is involved. Use this frequency for 2 to 4 minutes. If the mechanism of injury involves flexion or combined flexion and rotation, or if flexion exacerbates the pain, the disc is almost certainly involved. Use 40Hz on channel A combined with all three disc tissue frequencies on channel B if 40 / 710 (annulus) produces a very strong response.

• Treatment time: 2 to 4 minutes for each frequency combination. Time will vary for each frequency combination depending on patient

Figure 7.12 • Place the positive leads glove in a warm wet fabric contact (hand towel) and wrap it around the neck where it can treat the outflow of every cervical nerve. Place the negative leads contact in a warm wet contact (hand towel) that is draped across the abdomen, along the chest wall, under the axilla and around the upper arm and onto the chest. Position the patient’s hand and forearm so it lays on the wet contact. This placement allows every cervical nerve root (C4–C8), the entire brachial plexus and every muscle in between to be treated simultaneously. Move the relaxed hands every 2 to 3 seconds allowing the finger pads to assess and treat the muscles in between and under the towels. This position allows easy access to the anterior scalenes, the pectoralis major and minor, subscapularis, serratus anterior, deltoid, biceps, triceps, corico-brachialis, SCM, forearm flexors and extensors. Block the current from flowing through the practitioner by using a latex glove or some sort of oil on the hands. Do not get oil on the graphite gloves as it ruins their conductivity.

response. If time allows, continue using a given frequency as long as the tissue continues to soften. If the tissue stops softening and firms up, change to the next channel B frequency. Animal studies show 40 Hz produced maximal reduction in inflammation at 4 minutes.

91 / 710

• Remove hardening from the disc annulus. The disc annulus becomes hardened and calcified in chronic degeneration. When myofascial trigger points are associated with degenerative changes the muscles soften and the disc appears to become more flexible when 91 / 710 are used. This frequency combination prolongs the effect of the myofascial treatment.

• Treatment time: 2 to 4 minutes. The spinal joint will become more flexible as this combination is used. Gentle side to side rocking to mobilize the joint in extension and segmental rotation will help

Figure 7.13 • With the patient prone, place the positive leads glove in a warm wet fabric contact (hand towel) lengthwise down the spine. Place the negative leads glove in a warm wet fabric contact (hand towel) lengthwise under the trunk from clavicle to pubic bone. This placement allows all of the thoracic nerves, discs, and facets and all of the thoracic muscles to be treated simultaneously. Move the hands every 2 to 3 seconds using the finger pads with relaxed fingers to assess and treat any muscle. Move the hands between and under the towels to treat the thoracic paraspinals, the latissimus, the trapezius, the rhomboids, and the thoracic intercostal muscles and nerves. Block the current from flowing through the practitioner by using a latex glove or some sort of oil on the hands. Do not get oil on the graphite gloves as it ruins their conductivity.

maximize this affect. Change to the next frequency when the frequency does not produce any further improvement.

Treat the spinal facet joint

40 / 783, 157, 480

• Remove inflammation from the spinal facet joint tissues: the periosteum, the cartilage and the joint capsule. If the mechanism of injury involved extension or compression combined with extension as in a fall or rear-end auto accident, or if spinal extension exacerbates the pain, then inflammation in the facet joint tissues is almost certainly involved. This is not meant to be a comprehensive treatment of the facet joint but is meant to address the role of the facet joint as a perpetuating factor in the myofascial trigger points.

• Treatment time: 2 to 4 minutes for each frequency combination. Time will vary for each frequency combination depending on patient response. If time allows, continue using a given frequency as long as the tissue continues to soften.

Figure 7.14 • The exact same process is used for treating the anterior thoracic muscles except that the patient is supine. Positive contacts are at the spine so the nerves can be treated with polarized positive current. Negative leads are placed midline on the trunk. This placement and patient position allows treatment of the thoracic intercostal muscles and nerves, the pectoralis major and minor, the abdominal obliques and rectus abdominus, the ilio-psoas, and even the glute medius and minimus. Glide the finger pads across the skin moving them every 2 to 3 seconds feeling for softening and mobilizing adhesions. Think of the anatomy as tissue types. When the frequency for “connective tissue” (77) is being used focus the fingers at the linea alba and the connective tissue bands in the rectus abdominus. When treating the thoracic intercostals remember to include the periosteum (783) among the frequencies used and place the fingers at the attachments between the periosteum and the intercostal fascia while it is running.

If the tissue stops softening and firms up, change to the next frequency. Animal studies show 40Hz produced maximal reduction in inflammation at 4 minutes.

91 / 783, 480

• Remove hardening from the periosteum and joint capsule. The joint capsule and periosteum become hardened and calcified in chronic facet joint degeneration. These two frequency combinations soften the joint capsule and reduce the tenderness where the capsule attaches to the periosteum. These two combinations usually produce significant improvement in joint function.

• Treatment time: 2 to 4 minutes. The spinal joint will become more flexible and less painful as this combination is used. The periosteum is very pain sensitive and 91 / 783 usually produces the best improvement in facet joint pain. 91 / 480 usually produce the best improvement in joint flexibility and motion. Gentle side to side rocking with the finger tips to mobilize the joint capsule in segmental rotation will help maximize this affect. Change to the next frequency when the frequency being used does not produce any further improvement (see manual technique note below).

13 / 480, 396 with movement

• Remove scarring from the joint capsule and its nerve. Chronic inflammation in and around the joint creates fibrosis and scarring in addition to the calcium influx seen in chronically inflamed tissues. The joint capsule and its recurrent nerve become adhered to each other by scarring. When the capsule stretches during flexion or rotation the nerve is stretched and produces pain with movement. The pain produced by scarring in the nerve tends to be sharp and occurs only with movement. Releasing the scarring between the nerve and the capsule alleviates the pain fairly quickly and usually produces significant increase in motion.

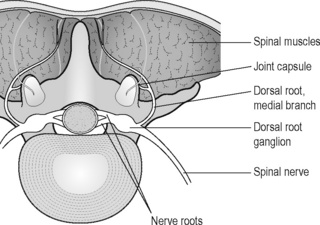

Figure 7.15 • The relationship between the medial branch of the dorsal nerve root that innervates the facet joint capsule and the paraspinal muscles. Inflammation of this nerve mediates facet joint pain and chronic inflammation leads to adhesions between the nerve and the facet joint capsule and between the nerve and the muscle. Branches of the ventral root stimulate muscle hypertonicity. Adhesions between the fascia and sensory and motor nerves cause pain with muscle contractions and joint motion. 13 / 396, 142 soften these adhesions and increases comfortable joint motion. Visualize gently teasing the nerve away from the capsule and the paraspinal muscles.

• Manual Technique: When using the frequencies for removing scar tissue from the joint capsule and its nerve, create slight segmental rotation to move the capsule through a small range while the frequencies for calcium and scarring are being used. When treating the cervical spine supine this is accomplished by lifting the joint line a few centimeters on one side and then the other with the finger pads. Move the joint line in such a way as to reproduce this joint motion when the patient is prone. In the thoracic spine gentle pressure may be applied by using the thumbs to rock the joint in slight rotation at the capsule line. When treating the lumbar spine supine, the patient is positioned with the knees flexed and the back flat. If tolerated, the lumbar joints can be mobilized by rocking the knees a few inches from side to side to produce lumbar rotation. If rotation is not tolerated, the practitioner can place the finger pads on the joint line and lift the joint line about a centimeter, rocking the joint capsule from side to side. The use of such movements generally reduces pain and increases range of motion in the joint capsule more quickly. This manual technique can be beneficial when using 91 / 480 to remove calcium from the joint capsule.

Figure 7.16 • Visualize the relationship between the facet joint capsule and nerve adhered to it. Visualize gently dissolving the scar tissue between the nerve, the joint capsule and fascia with 13 / 396, 480, 142 and gently rock the joint to tease the nerve away from the fascia and the joint capsule. The movement should be very small to start, perhaps 2–3mm, and should stop and go back to neutral at the first sign of restriction. Move the joint again by lifting the segment at the capsule; this time the movement may be easier and should move about 3–4mm and perhaps 10 to 20 degrees of rotation. Move the joint back to neutral at the first sign of pain, muscle splinting or resistance. Keep the backs of the hands on the table, keep the fingers relaxed and use the pads of the finger tips to lift the joint at the lamina / joint capsule juncture which can be identified by bony landmarks or by the presence of taut muscles over the capsule. This photo shows the very end range of this process. The technique applies to mobilizing any spinal joint and the surrounding muscles.

Treat the peripheral joint

40 / 191, 195, 783, 157

• Remove inflammation from the peripheral joint tissues: the tendon, the bursa, the periosteum and the cartilage. When there is a regional myofascial problem the peripheral joint will often be adversely affected. Abnormal biomechanics caused by hypertonic muscles in the shoulder will often create an impingement of the supraspinatus tendon and bursa. The diagnosis may be “impingement syndrome” but the cause will be trigger points and taut bands in the subscapularis and teres because they are not performing the function of pulling the humeral head down and away from the tendon, bursa and acromion during abduction. In the absence of direct trauma or specific overuse, all of this dysfunction may occur because the disc has inflamed the nerve, making the muscles taut and unresponsive. The same principle holds true for every peripheral joint. As always the cause must be treated in order to create lasting improvement.

• Treatment time: 2 to 4 minutes each. Time will vary for each frequency combination depending on patient response. Continue using a given frequency as long as the tissue continues to soften. Animal studies show 40Hz produced maximal reduction in inflammation at 4 minutes.

91 / 783, 480, 195, 191

• Remove hardening from the periosteum, the joint capsule, the bursa and the tendon. Inflammation leads to chronic inflammation which leads to induration or hardening in the soft tissues and joint surfaces. 91Hz softens the tissue being treated and in the case of peripheral joints reduces the pain in the periosteum and bursa in particular.

• Treatment time: 2 to 4 minutes on each combination. The joint will become more flexible and less painful as these combinations are used. The periosteum and bursa are very pain sensitive and 91 / 783, 195 usually produces the best improvement in peripheral joint pain. 91 / 480 usually produces improvement in joint flexibility and motion. Gentle rocking of the joint in a small range with the finger tips to mobilize the joint capsule will help maximize this affect. Change to the next frequency when the frequency being used does not produce any further improvement (see manual technique note above).

Figure 7.17 • Place the positive leads in a warm wet contact under the low back using either a graphite glove or alligator clips (see Chapter 11). Place the negative leads in a warm wet towel on the thigh above the knee. This placement allows polarization of the L2, L3 and L4 nerve roots and treatment of every tissue between the contacts. Lay the relaxed hand gently on the abdomen; palpate the muscle by increasing the pressure slowly to minimize guarding. If the abdominal muscles splint with very light pressure some visceral perpetuating factor is almost certainly involved. See “When is myofascial pain not myofascial pain?”. If the trigger points are coming from the muscle, the nerve, the disc or the joint this position will allow simultaneous treatment of all of the agonists and antagonists, pain generators and perpetuating factors.

Figure 7.18 • The same contact placement can be used with modified manual technique to treat the anterior and posterior low back muscles and to increase motion in the lumbar facet joints when the pain is purely musculoskeletal. Patients with low back pain from myofascial trigger points and facet joint degeneration are most comfortable in a supine position with the back flat and knees bent. Treat the psoas and lumbar paraspinals first using the “treat the nerve – treat the muscle” strategy. When the protocol progresses to the “treat the joint” frequencies lay one hand under the arch of the low back and use the finger tip pads to lift and gently mobilize the facet joints as described in Fig. 7.16. Move the joints incrementally with a very slow gradual rocking motion while using 91, 13 / 396, 480, 783, 710.

Figure 7.19 • The patient will be more comfortable lying prone if the discs are involved and the facet joints are not pain generators. Place the positive leads contact in a warm wet towel across the low back. Place the negative leads contact under the abdomen. This position focuses the current and frequencies on the lumbar spine alone. If there is referred pain or associated myofascial pain in the hamstrings or gluteals the negative leads contact may be placed under the knees so the current flows through the tissue in three dimensions. Using gloves or alligator clips in towels frees the practitioner’s hands to focus on, assess or treat any muscle or joint.

Figure 7.20 • Extremity muscles can be treated with the practitioner wearing the gloves, as shown here. Or any extremity muscle can be treated by wrapping the positive lead contact at the spine where the relevant nerve exits and wrapping the negative leads contact distal to the area of involved muscle and using the hands in between the two contacts to treat the desired muscles. The frequency protocols remain the same – treat the nerve, treat the muscle, treat the joint. Think of the muscles being treated and think of the anatomy as tissue types. Forearm and lower leg flexors and extensors have very long tendons, tendon sheaths and proportionally high concentrations of connective tissue that can become inflamed, calcified and adhered (40, 91, 13 / 191, 195, 77). The nerves in the extremities can become adhered to the surrounding fascia by trauma or inflammation (58/’s, 13 / 396, 142).

Customize treatment

The frequency response is very condition and tissue specific and efficient treatment requires that the pain generators (fascia, nerve, periosteum) and the pathologies affecting them (inflammation, hardening, scarring) be accurately assessed. Different patients will respond differently to each portion of the myofascial protocol. This response becomes instructive. The frequency response, the tissue softening (smoosh) created when a correct frequency is used, happens so quickly and so predictably that eventually the practitioner learns to use this response to guide treatment and frequency choices. The successful frequencies will address the pathologies associated with the formation or perpetuation of trigger points.

For example, the mouse research demonstrated that the frequency to reduce inflammation functioned in a 4-minute time dependent fashion. All of the anti-inflammatory effect was present at 4 minutes and half of it was present at 2 minutes. In general this time dependent response seems to apply to humans as well.

In the interest of efficiency the joint portion of the treatment should focus on the tissues most affected by the pathology being treated. Every tissue may be treated with 40Hz for 4 minutes each but this increases treatment time considerably and not all of the tissues may actually be inflamed enough to require 4 minutes of treatment. Determining which tissues are most likely to be inflamed can be done according to the history and the mechanism of injury or by palpation of the painful area. If treatment time is limited 40Hz may be used with each tissue for only 2 minutes in the hope that the cumulative effects will create an optimal response. Ideally the manual therapist will note which tissue frequency has the strongest softening response to 40Hz and will spend more time treating that tissue.

The sensitivity needed to make this determination improves with time and experience. The practitioner is advised to use a relaxed hand during treatment in part because transmission of sensory information is enhanced when motor output is minimized. The practitioner is advised to be patient as this skill develops.

Customize by history and examination

If the mechanism of the original injury includes only flexion or flexion combined with rotation then the disc is most likely to be involved. If the pain increases when the patient flexes the painful area then the disc is most likely to be involved. If the injury was fairly minor, the disc annulus may be the only compromised tissue and the other two disc components may not respond to or require treatment.

If the mechanism of the original injury, even years earlier, involved extension (joint compression) and then flexion as is seen in a rear end impact auto accident or some falls, then the facet joint tissues may be the most inflamed but the disc annulus will be involved too.

If the mechanism of injury involves only chronic joint extension and compression or ballistic traumatic extension during a fall, then the spinal facet joint tissues are most likely to be inflamed and to respond to treatment.

If the history and examination suggests that the peripheral joint tendons, bursa and periosteum are inflamed due to impact, overuse or because the pain is localized directly over these structures then the treatment may reasonably be focused on inflammation and hardening in these tissues.

Customize by palpation

Once the nerve and muscle have been treated the texture of the soft tissues will have changed dramatically. Most of the soft tissue will be “smooshy” as if the ground substance within has changed from a solid to a gel or even to a liquid. The feeling is unlike anything produced by traditional myofascial therapy or any intervention short of general anesthesia and has to be experienced to be appreciated.

When the spinal discs or the facet joints or the peripheral joints are inflamed the muscles overlying these structures will not be “smooshy” but will remain stiff or taut after the surrounding tissues have become soft. The difference in texture and tone is dramatic to the practitioner experienced and adept at palpation and draws attention to the area needing attention.

If the taut muscles are just lateral to the spinous processes and include the multifidi or the iliocostalis group that overlie the spinal facet joints, and if they become stiffer with even minimal joint compression then reducing inflammation and hardening in the facet joint structures is most likely to produce the best response in the muscles.

If the taut muscles are more lateral to the spine and slightly anterior to the facet joint then the disc is more likely to be involved. In the cervical spine, the posterior and lateral scalenes, levator scapulae, and SCM will be tight and tender. In the thoracic and lumbar spine, the paraspinal muscles or the quadratus lumborum directly over the involved disc, but lateral to the lamina, will be taut when the surrounding muscles have relaxed from treating the nerve and muscle pathologies. In the cervical spine with the patient supine, the anterior scalenes and longus coli will remain taut and tender directly over the anterior portion of the involved cervical disc when the other muscles have relaxed. In the lumbar spine the psoas will remain tender and taut directly anterior to the involved disc. The muscle tension indicates that treating the disc should be the next step.

If the peripheral joint is inflamed the muscles directly over the tendon or bursa will be taut and there will be point tenderness to pressure directly over the inflamed periosteum, bursa and tendon.

Customizing treatment by either palpation or history makes treatment more efficient. The frequency response helps train sensitivity because the softening occurs when the frequency is correct. The practitioner can treat by the script provided above until the sensitivity to the softening affect develops.

Side effects of FSM myofascial treatment

Detoxification reaction

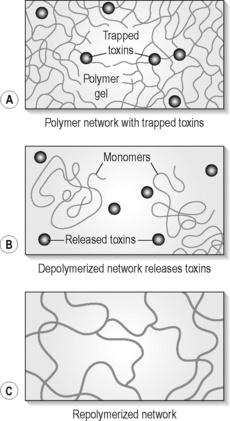

The most common side effect that occurs with myofascial treatment is a detoxification reaction similar to that seen after a deep tissue massage. The patient may feel flu-like symptoms including fatigue, brain fog, nausea, headache, generalized malaise and body aches or increased pain. The symptoms start about 60 to 90 minutes after the treatment and very rarely will progress to include vomiting.

The symptoms are presumed to come from incomplete processing of toxic metabolites released from the muscles as they pass through the liver so they can be excreted. There are two liver detoxification enzyme pathways that perform this function. The phase-one liver detoxification pathways perform hydrolysis reactions in which a water molecule is broken in half and the polarized particle is attached to the substance being processed so it can be shipped out of the liver as an inactive polarized metabolite. The phase-two detoxification pathways break the toxin apart and attach a cap, called a substrate to its active end. The substrate is said to be “conjugated” to the toxin and makes it inactive so it can be safely excreted as an inactive metabolite. Under normal conditions phase-one and phase-two detoxification pathways co-ordinate function and toxins are excreted at a steady rate.

When the liver is processing toxins at the normal rate, water and the substrates are recycled in time to meet the steady demand. When large quantities of toxins are released in a short time from the fascia by either deep massage or an FSM treatment, the liver detoxification pathways can become overwhelmed and run out of either water or substrate or both. With insufficient material available to complete the detoxification processes the liver enzymes release the half finished metabolites prematurely and these may, in many cases, be more toxic than the original product. These half-processed metabolites are the source of the symptoms experienced in a detoxification reaction.

This reaction is most often a problem in the first one to two myofascial treatments. Liver enzymes will proliferate in number and become more active in response to increased demand. The patient easily remembers to drink extra water after even one “detox” episode and this side effect is rarely seen more than once or twice.

• Prevention: The first myofascial treatment should not exceed 20 minutes. A short treatment on a smaller muscle group will limit the amount of toxins released. Patients with known liver disease or known problems with detoxification should be treated for an even shorter period of time. Patients should be instructed to drink up to one

Figure 7.21 • Waste products trapped in the fascia are released during treatment as the fascia unwinds and can overwhelm liver detoxification processes if the liver has inadequate water or enzyme substrate

(from Oschman 2008).

quart of water in the 90 minutes following treatment to supply the additional water needed for hydrolysis reactions in the liver. The patient may also be given an in-office dose of a complex low dose anti-oxidant supplement containing such substrates as vitamin C, vitamin E, n-acetyl-cysteine, lipoic acid and other liver friendly nutrients. If this is not possible the patient can be instructed to take a dose of a commonly available multiple vitamin supplement of their choosing when they reach home.

• Treatment: If the patient calls and describes a detoxification reaction recommend immediate consumption of water containing a bit of lemon if it is available and provide reassurance about the source of the symptoms and their temporary nature. Alcohol, Tylenol (acetaminophen) and caffeine occupy the same detoxification pathways used by the muscle metabolites and should be avoided after treatment. The reaction rarely lasts more than 4 to 12 hours when these steps are taken.

Nerve pain

When treatment for myofascial pain produces a significant increase in range of motion, as it often does, bone spurs near the neural foramen in the spine, primarily in the cervical spine, can impinge on the nerve because of the increased motion and irritate the nerve. The patient experiences improved neck pain but a new onset of pain in the distal nerve root. The patient may comment, “My neck feels great but my thumb and forearm really hurt.”

• Prevention: This reaction is hard to prevent but can often be predicted which is almost as useful. If the patient is older than 45 or has a significant history of spine trauma, the presence of bone spurs in the cervical spine is somewhat predictable and can be confirmed by a standard x-ray series that includes oblique views which best demonstrate bony encroachment on the neural foramen. This reaction is uncommon but diagnostic and never happens except when range of motion allows bone spurs to move into the nerve. If the patient refuses or cannot have the x-ray the practitioner can proceed on the assumption that bone spurs are present. In treating patients who experience this reaction it would be advisable to end every future myofascial treatment by treating the nerve to see if it can be prevented.

• Treatment: The nerve pain is easy to treat by using 40 / 396 with the current polarized from the neck to the end of the irritated nerve root. The pain should be reduced within 10 minutes and eliminated within 20 minutes. The cerebellum and proprioceptive system react to the nerve irritation and restrict range of motion in the cervical spine within a day or two of treatment so the bone spurs will stay well away from the nerve in the future. The muscles will remain trigger point free and pain free for some period of time and it may be 3 to 6 months before the muscle need to be re-treated. If the muscles are less taut and the neck is more mobile there is some suggestion that the bone spurs can be reabsorbed.

Increased joint pain

When myofascial treatment increases range of motion and degenerated joints are allowed to move farther than they have in years, joint surfaces can become inflamed after the unfamiliar movement. It is similar to sliding a drawer open for the first time in years and hearing the screech as it scrapes across the sticky and stiff drawer glide. The unlubricated cartilage surface of the facet joint is the sticky drawer guide and the “screech” causes inflammation of the joint surface from the unfamiliar motion. The irritation in the capsule and recurrent nerves as they stretch beyond their normal range can also create increased joint pain following myofascial treatment.

• Prevention: This reaction can be prevented by remembering to treat the spinal joint for inflammation, hardening and scarring in the cartilage, the nerve and the joint capsule at the end of the myofascial protocol. 40, 91, 13 / 157, 480, 783, 396 used for 2 to 3 minutes each will usually minimize or prevent this reaction.

• Treatment: This reaction can be treated by applying 40 / 116, 157, 783, 59, 39, 480, 396 for 4 minutes each. See Chapter 5 for more detail on treating

Increased segmental pain from ligament laxity

If myofascial tissue has been tight to form a splint to stabilize a joint with lax ligaments and the FSM treatment loosens the muscles and increases the range of motion, the lax joint is no longer splinted or stable. The joint will translate instead of gliding properly, as described in the ligamentous laxity chapter, allowing the facet joints to crash into each other and creating stress on the discs and causing local inflammation. The patient will feel wonderful for about 2 to 4 hours following myofascial treatment but will report point tenderness over one or more joints at the spine after that.

The patient will often comment that the “treatment made my pain worse” in these cases. The reply should be, “When and where did your pain increase?” This reply reassures the patient that there is a reason for the pain which can be determined by knowing exactly when and where it increased. If the pain increased within 2 to 6 hours of the treatment and palpation localizes the tender area to the posterior joints or ligaments of the spine it is diagnostic of ligamentous laxity.