Chapter 11 Behavior of the stallion

Chapter contents

Free-ranging harem-maintenance behavior

Observations of free-ranging horses have provided numerous examples of the ways in which we restrict the behavior of managed stallions, restrictions that can lead to aggression and reduced fertility, libido and behavioral compliance.

Herding is usually employed by stallions to move the family group away from a threat such as a single stallion or another group. Free-running stallions typically herd together a harem of mares as a relatively stable social unit. They tend to recruit and retain mares most effectively when 6–9 years of age.1 The upper limit on the size of harems relates to the fact that if a stallion monopolizes too many mares he loses the ability to dissuade other males from performing sneak matings.1 Sometimes juvenile males, old stallions and, more occasionally, mares cooperate with the harem stallion in his herding activities. This herding behavior can be used to tighten a band or to move interlopers out of or, occasionally, non-member females into the group. Herding, characterized by the neck snaking from side to side, is also seen during courtship, its aim being to transiently distance the mare from the harem for copulation.2 Cohesion of the group contributes directly to biological fitness because, for example, invasion by non-member stallions can induce abortion and bring mares into season for subsequent mating by invading males.3 Vigilant herding is most evident after a harem mare has foaled. At this time the stallion works to maintain a greater than usual distance from other bands, perhaps because this helps him to capitalize on the fact that free-ranging mares peak in fertility during the foal heat.4

Sometimes low-ranking males, notably the sons of low-ranking mares, form lifetime alliances in which both stallions have mating rights and cooperate to defend their mares from intruding males.5 The balance of the pair is rarely equal, with the subordinate stallion siring approximately one quarter of the harem’s brood. This compares favorably with the success of sneak matings that represent the only alternative for non-alpha males.5 However, reciprocal altruism and mutualism do not occur in multi-stallion groups. Linklater & Cameron6 reported a positive relationship between aggression by the dominant stallion toward subordinate stallions and the subordinates’ effort in harem defense, which was negatively correlated with the extent to which these stallions were seen to consort with harem mares. Perhaps because they undergo more social flux than single-stallion groups, multi-stallion groups are associated with more aggressive interactions and reduced foaling rates – hence, the suggestion that there is selection pressure for single-stallion groups.7 The various agonistic responses that arise between stallions appear in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1 Features of the agonistic ethogram (as described for bachelors11) that are particularly common among and between stallions

| Response | Description |

|---|---|

Boxing  |

Two stallions in close proximity simultaneously rearing and striking out with alternate forelegs toward one another |

Circling  |

Two stallions closely beside one another head-to-tail, pivot in circles, usually biting at each other’s flanks, groin, rump and/or hindlegs. With prolonged circling, the stallions may progress lower to the ground until they reach a kneeling position or sternal recumbency, where they typically continue to bite or nip one another |

Dancing  |

Two stallions rear, interlock the forelegs and shuffle the hindlegs while biting or threatening to bite one another’s head and neck |

Defecate over  |

Defecation on top of fecal piles in a characteristic sequence: sniff feces, step forward, defecate, pivot or back up, and sniff feces again |

Erection  |

Fully extended and tumescent penis. Observed during mildly and moderately aggressive encounters. Bachelors will mount one another with an erection and anal insertion has been observed |

Flehmen  |

Head elevated and neck extended with the eyes rolled back, the ears rotated to the side and the upper lip everted exposing the maxillary gums and incisors. The head may roll to one side or from side to side. Typically occurs in association with olfactory investigation of feces |

Head bowing  |

A repeated rhythmic flexing of the neck such that the muzzle is brought toward the point of the breast. Head bowing usually occurs synchronously between two stallions when they first approach each other head-to-head |

Head bump  |

A rapid toss of the head that forcefully contacts the head and neck of another stallion. Usually the eyes remain closed and the ears point forward |

Head on neck, back or rump  |

The chin or entire head rests on the dorsal surface of the neck, body or rump of another horse. This often precedes mounting |

Herding  |

Combination of head threat and ears laid back with forward locomotion, apparently directing the movement of another horse. When lateral movements of the neck occur, the horse is said to be snaking |

Kneeling  |

Drop to one or both knees, by one or both stallions engaged in face-to-face combat or circling with mutual biting or nipping repeatedly at the head and shoulders and knees |

Masturbation  |

Erection with rhythmic drawing of the penis against the abdomen with or without pelvic thrusting. This is a solitary or group activity |

Mount  |

Stallion raises his chest and forelegs onto the back of another horse (be it a mare in a breeding context or another male in a bachelor group) with the forelegs on either side. Also seen primarily in bachelor groups are prolonged partial mounts, typically with lateral rather than rear orientation and often with just one foreleg across the body of the mounted animal. In a behavior similar to the initial mount orientation movements (termed head on neck, back or rump) the forelegs will not actually rise off the ground. Mounts and partial mounts may occur sequentially or independently of one another |

Neck wrestling  |

Sparring with the head and neck that may involve one or both protagonists dropping to one or both knees or raising the forelegs |

Parallel prance  |

Often seen immediately prior to aggressive encounters, two stallions move forward beside one another, shoulder-to-shoulder with arched necks and heads held high and ears forward, typically in a high-stepping low cadenced trot (passage, in dressage terminology). Rhythmic snorts may accompany each stride. Solitary prancing also occurs |

Posturing  |

Posturing describes a suite of pre-fight behaviors that includes head bowing, olfactory investigation, stomping, prancing, rubbing and pushing, all with neck arching and some stiffening of the entire body |

Sniff feces  |

Approach and sniff a pile of feces or a fecal pile, usually as a part of a fecal pile display. Often associated with some pawing, this is almost always followed by defecating over the feces and again sniffing the pile |

The harem stallion exhibits characteristic, even ritualistic, responses to urine and feces of harem members. It is believed that olfactory characteristics of these materials inform the stallion of the reproductive status of the mares while his responses to them serve to maintain the harem. Stallions are more responsive to olfactory stimuli from conspecifics than are mares and geldings.8 Contact with urine, feces or vaginal fluids during courtship and copulation occurs and forms an important part of the mating behavior, resulting in a flehmen response by the stallion.2 Pawing, sniffing and flehmen are followed by his depositing small amounts of feces or urine on top of previously voided material.9,10 The stimuli offered by fecal material are discussed in detail in Chapters 6 and 9.

Development and maintenance of sexual behavior in free-ranging stallions

From the first weeks of life colts demonstrate mounting attempts, mainly on their dams. These attempts are rarely accompanied by pelvic thrusting. Erections have been observed in colts as young as 3 months of age but these are of minimal import to a herd since the mature stallions monopolize estrous females and, in any case, spermatozoa are not found in testes before 12 months of age. Spermatogenesis lags behind hormonal maturity. Fertility does not increase significantly until the colt is approximately 2 years old with the histological transition from the pre-pubertal to the post-pubertal stage occurring at a mean age of 27.8 months (n = 28).12

Most colts leave the natal band and join bachelor groups around the time of the birth of their siblings.13 For example, in one study of Misaki feral horses in Japan, 17 of 22 colts left their natal bands at this time.13 Scarcity of resources is also regarded as a common cause of voluntary separation.14 So, as colts become steadily bolder with age and playmates disperse, they may gravitate toward bachelor groups in search of recreation.15 Beyond the age of 3 years, remaining young males may be forced to leave the harem group during the breeding season as a result of increased aggression by the harem stallion.2,14

The behavior of young stallions can then be considered in two stages. The first is a developmental stage in which the colts that have just dispersed from the natal band (between 0.7 and 3.9 years of age in Misaki horses) engage more in social play than agonistic behavior, while the second is a pre-harem formation stage, which involves departure from the bachelor group.16 The separation of the highest-ranking stallion from the subordinate males has significant behavioral and physiological consequences.

The status of the stallion is broadly correlated with androgen activity. Testosterone concentrations increase with the age of stallions until they form their own harems.15 Furthermore, for individual stallions, testosterone concentrations are correlated with harem size.15 So, in a harem stallion, sexual and aggressive behavior, accessory sex-gland activity, testicular size and semen quality are enhanced by the dispersal of potential challengers. Meanwhile, stallions becoming bachelors undergo changes in the opposite direction3,11 and may show signs of concurrent depression (Sue McDonnell, personal communication 2002). Paradoxically, some domestic stallions may redevelop their libido when another stallion is brought to the breeding area, and some slow-breeding novice stallions seem to increase their arousal when given the opportunity to watch other stallions copulate.9

It is worth noting that despite low androgen concentrations, agonistic behavior, including mock and serious fighting, is a conspicuous characteristic of bachelor groups.11 Continued studies of bachelor groups could serve to further challenge the traditionally held view that stallions are innately aggressive and somehow deserving of isolation.17

Free-ranging matings

Prolonged pre-mating interactions are the norm for all free-ranging equids. Harem stallions discriminate among mares, according to their maturity and length of residency in the harem. As evidenced by the increased frequency of flehmen responses, olfactory stimuli help to identify estrous mares, but they are supported by visual and auditory cues from the mare.18,19 Always favoring mature harem mares, the harem stallion will often ignore young estrous mares (from both his and other harems) and actively chase away mature mares from other harems.20 Free-running stallions usually interact with sexually active mares or their excrement for many days before copulation. Often these encounters can be counted in hundreds per day.20 Because stallions can differentiate the sex of a horse on the basis of its feces (not its urine), it has been suggested that sampling of feces is extremely informative for a stallion when monitoring the cyclicity of females in his harem.10

When he has located an estrous mare, or she has located him, the harem stallion will often attract her attention by whinnying from a distance and then pawing the ground, prancing and nickering as he approaches. Once these preliminaries have taken place, the mare actively contributes to precopulatory behavior.21 To illustrate, it has been demonstrated that 88% of sexual interactions that lead to successful copulation begin with the mare approaching the stallion.20 An important trigger of the stallion’s physical sexual arousal seems to be the head-to-head approach by the mare toward him, followed by her moving forward or swinging her hips toward his head.20

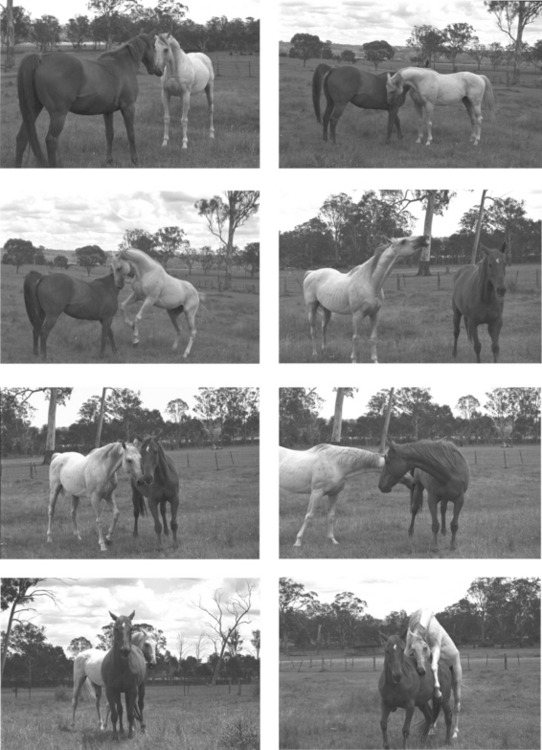

A stallion’s method of determining a mare’s receptivity is to nuzzle and push her hindquarters. Pre-copulatory behavior demonstrated by the stallion includes sniffing, nuzzling, licking and nibbling or nipping the head, shoulder, belly, flank, inguinal and perineal regions of the mare (Fig. 11.1).2,20,22 These prompts may elicit a mildly aggressive display by the mare, despite her being in full estrus. However, as this aggression subsides, the mare tolerates closer approaches by the stallion. Further arousal results when positive feedback is received from the mare.23

Figure 11.1 Courtship and copulation in the horse.

(Photographs courtesy of Michael Jervis-Chaston.)

Pre-copulatory behavior continues until the mare’s stationary ‘sawhorse’ posture cues the stallion to mount. Mounting may occur without erection. Studies have shown that mounting without an erection is common and has been demonstrated among highly fertile pasture-breeding horses.2 The number of mounts without an erection is typically 1.5–2 times the number of mounts with erection.2 In free-ranging equids, mounting with an erection almost always leads to insertion and ejaculation. While young inexperienced stallions typically mount laterally and then adjust their position, mounting by mature males is usually achieved by an approach from the rear. Although they may ejaculate sooner than their more experienced peers, colts take significantly longer to achieve an erection (after first seeing an estrous mare) and to mount.24 Once he has mounted correctly, the stallion grasps the mare’s iliac crests with his forelegs while his head leans against her neck, and he often nips or grasps her mane with his teeth.2

Free-ranging pony stallions achieve intromission during the first mount in 55% of copulations.25 Successful intromission (Fig. 11.1) during subsequent attempts is facilitated if the mare remains stationary. Intromission is generally accomplished after one or more seeking thrusts and is often marked by the stallion closely coupling up to the mare and paddling his feet as if attempting to ensure that they are on a firm surface.2 An average of seven pelvic thrusts26 occur before ejaculation, which is characteristically indicated by:

• flagging of the tail (associated with transient shrinkage of the urethral lumen and six to nine spurts of ejaculate)27

• rhythmic contractions of the muscles of the hindlegs

The period from intromission to ejaculation is usually 10–15 seconds, with young males tending to take less time.23 After ejaculation, the stallion often appears dazed as he relaxes on the mare’s back and his penis becomes flaccid. Once the stallion has regained his alertness, the mare steps forward, easing the stallion’s chest over her hindquarters, so that he lands gently on his front feet.27 The mean interval between the end of ejaculation and the start of dismount is eight seconds (Table 11.2).23

Table 11.2 Typical frequency and latency of copulatory behaviors by young and adult domestic stallions

| Typical value | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of responses | ||

| Sniff or nuzzle | 3 | 0–80 |

| Lick | 0 | 0–20 |

| Flehmen response | 2 | 0–10 |

| Nip or bite | 0 | 0–25 |

| Kick or strike | 0 | 0–10 |

| Vocalization | 3 | 0–35 |

| Number of mounts | 1 | 1–3 |

| Number of thrusts | 7 | 2–12 |

| Latency of responses (seconds) | ||

| Time to erection | 10 | 0–500 |

| Time to first mount with erection | 15 | 10–540 |

| Time from mount to insertion | 2 | 1–5 |

| Time from intromission to first emission | 15 | 8–20 |

After Waring et al24 and McDonnell.2

The stallion’s post-copulatory behavior often includes sniffing the mare’s vulva, as well as the spilled ejaculate or urovaginal secretions of the mare, and this typically prompts the flehmen response.28 After ejaculation, the stallion and mare generally uncouple within 3–15 seconds, with the mare being first to move away in 60% of cases and the stallion in 26%, although occasionally the mare follows.25

Mares and stallions will often separate from the harem group during courtship and mating. Although the pre-copulatory interactions with mares may last several days, the copulatory interactions themselves frequently last for less than a minute. While breeding rates as high as 18 per day have been recorded,2 the daily mean for adult stallions is 11.23 The refractory period after ejaculation appears to be shorter in free-running stallions than in their intensively managed counterparts.20

Seasonality

Stallions possess an endogenous circannual reproductive cycle that is responsive to photoperiod.29 Timed to synchronize with the emergence of mares from winter anestrus, the responsiveness of stallions to sexual cues increases in spring and is maintained until the beginning of autumn but never completely disappears. The seasonality in testosterone concentrations15 is reflected in semen quality and can also influence the number of mounts per ejaculation, latency to achieve intromission, frequency of biting and striking.30 The prevalence of spontaneous erections in masturbating stallions also increases with day length.31

The artificial breeding season that starts in late winter for many breeds (such as the Thoroughbred, Standardbred, Quarterhorse and Arabian) may contribute to reports of low sexual vigor. The physiological season can be brought forward in young and middle-aged stallions by placing them under artificial lights, which can increase testicular size and sperm output.32 It is interesting to note that no deleterious effects on fertility have yet been reported in shuttle stallions that work two seasons per year by being shipped between northern and southern hemispheres.32

Traditional stallion management

The value of many stallions and the risk of injury through fighting are the principal factors that drive their owners to stable them and minimize unsupervised contact with other horses. By clipping out elements of the harem stallion’s sociosexual behavioral repertoire, hands-on stallion management can leave the entire male equid with the opportunity to perform only brief pre-copulatory interactions (Fig. 11.2).20 The resultant arousal and thwarted motivation can contribute to the handling difficulties some stallions present.

Domestic breeding stallions are generally maintained in physical isolation, either stabled alone or near other stallions.33 Breeding farms with more than one breeding stallion often stable all the stallions together, away from the mares, in a stallion yard. This management regime has the potential to impose some characteristics of the bachelor group on some occupants of the yard. McDonnell20 found that the bachelor status of stallions could be effectively reversed by housing them in a barn with mares or in a paddock adjacent to mares. Regardless of the season, libido, testosterone concentrations, testicular volume and efficiency of spermatogenesis increase once the trappings of bachelor status are removed.3

While most stallions over 20 years of age retain their libido, few maintain competitive sperm counts. The decline of this fertility parameter begins at approximately 10 years of age. Testosterone concentrations 36 hours before and after injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) may help to detect declining reproductive function in aged stallions.34

Domestic stallions are generally permitted to copulate in three situations:

Figure 11.3 If the mare has been properly teased and is truly receptive, minimal restraint is required for in-hand breeding.

(Photograph courtesy of Michael Jervis-Chaston.)

While pasture mating usually follows the template of free-ranging horse behavior discussed above (except that stallions are sometimes separated from their mares during anestrus), in-hand breeding and semen-collection involve some radical departures from the normal ethogram.

Compared with equids breeding at liberty, in-hand breeding stallions show lower rates of sexual vigor and fertility and higher rates of sexual behavior dysfunction. This may be because the selection of breeding animals adopts inappropriate criteria and perhaps favors stallions that would not achieve harem stallion status in a free-ranging context. Stallions at pasture are generally capable of breeding nine times (every 2.5 hours) throughout the day and night with sustained fertility, while in-hand breeding stallions show diminished rates of fertility when bred more than once or twice daily.20,22,35

Ginther36 found that a stallion will copulate with one estrous mare repeatedly, even when more than one mare is in estrus. Stallions breeding at liberty have been observed to copulate twice with the same mare during a 7-minute period, while other stallions have copulated three times with two mares during a 2-hour period.2 While free-ranging equids are able to interact year-round on a moment-to-moment basis, domestic stallions are typically allowed minimal contact with mares other than brief limited interactions immediately before copulation.20 McDonnell20 concludes that it is remarkable that stallions denied the natural length of interaction are considered to have a normal breeding career. Human success in maintaining a stallion’s performance under these conditions relies on most stallions being able to respond to suboptimal stimuli, either naturally or as a result of conditioning.

Vesserat and Cirelli37 found that the conception rates of in-hand breeding were in the range 55–60%, while with pasture-bred horses conception rates per cycle were 75–85%. This is largely because more matings are performed at pasture than is expected with in-hand mating.22 Pasture-bred pregnancy rates at the end of the breeding season can reach 100%,38 but herd management must be optimal. The best foaling rates (in Icelandic horses) on pasture are achieved when no more than 15 fertile cycling mares per stallion are run for one heat cycle, or a maximum of 20 fertile cycling mares per stallion if they remain as a group for two heat cycles (6 weeks).39

Factors affecting sexual responses in the stallion

The quality of sexual responses in domestic stallions may vary considerably because it is under the influence of a number of factors, including previous experience and current stimuli.

Individual preferences

Occasionally, stud owners report a stallion’s preference for small mares. In these cases, it pays to conduct a thorough examination of the musculoskeletal system before assuming that this is an innate response. Intriguing color preferences have also been reported. For example, there is a report of a stallion selecting and running with only buckskin (dun) mares.28 One must remember, however, that the affiliation between mares and their filly daughters is often very strong indeed and the effect this has on the color distribution of a natal band may offer an alternative explanation for the apparent preference.

Visual stimuli

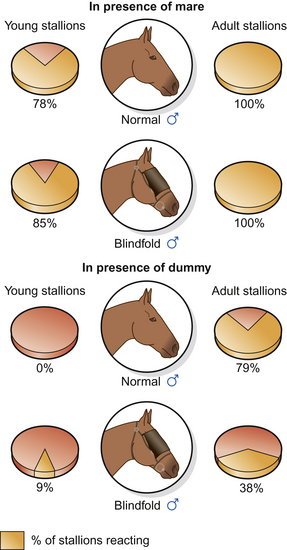

In most stallions, an overtly estrous mare will elicit a stronger sexual behavioral response than a breeding dummy or ovariectomised mare.2 Movement of the receptive mare as she turns from a head-to-head to hips-to-head presentation can have a strong arousing effect on stallions.20 It is likely that restraining the mare reduces the extent to which she can send solicitous expressive movements.

Typically the receptive mare urinates frequently and takes longer than normal to step out of the urination straddle. With her tail raised and slung to one side (most notably if she is a horse, rather than a pony) she winks her vulva repeatedly to deliver a flashing signal. A stallion responds to all of these cues by approaching and starting to tease her, which elicits further visual cues that signify receptivity in his prospective mate. Hostile signaling by a non-receptive mare includes laying back her ears, tail-swishing, kicking and biting. This is usually accompanied by squealing. A receptive mare is largely passive once she is in a hips-to-head position, but may actively present herself with a raised tail in response to the stallion’s nuzzling.

Olfactory stimuli

The odor of an estrous mare’s genital region and her urovaginal discharges contributes significantly to a stallion’s arousal.40 This accounts for the use of such fluids when training stallions for semen collection. The fluids cause a generic rather than specific response, since although stallions have been shown to discriminate between the urovaginal secretions of individual mares,8 olfaction appears to contribute to sexual arousal less than vision.41

Learning

Sexual behavior of domestic stallions is clearly influenced by experience and learning (Fig. 11.4), with breeding stallions learning by classical conditioning (see Ch. 4) to respond sexually to non-sexual stimuli associated with breeding. For example, in stallions bred in-hand, the service bridle, the service area and even key personnel can become conditioned stimuli that can cause arousal and erection.9 The importance of voyeurism in educating novice stallions should not be overlooked (see Fraser Darling effect in Glossary) since many free-ranging colts show keen interest when the harem stallion copulates.

Figure 11.4 Stimuli affecting the sexual responses of naïve and experienced stallions (after Wierzbowski42). Stallions visually assess mares (and dummies) as they approach to mount. Without the benefit of learning, naïve stallions may be more likely to mount when blindfolded because they are unaware of visual stimuli that are discouraging to them (e.g. threats in the case of mares) or simply inadequate (in the case of a dummy).

Stallions used for semen collection are expected to show sexual responses to a dummy. While occasional stallions will respond immediately to the dummy, most require the supportive effect of a transitional stimulus mare as an adjunct to several ejaculations with the dummy before reliable conditioning takes place. Teasing the stallion with a mare across the rear of the dummy is a particularly useful technique for developing the correct association.

Well-trained stallions distinguish themselves in the breeding shed by their tolerance of human interventions such as penis washing, while remaining responsive to conditioned commands used in the service area. The strength of innate responses and the role of learned associations have been quantified by comparing the responses of naïve and sexually experienced stallions when presented with a variety of stimuli.42 Sometimes libido becomes dependent on such conditioned stimuli and a program of generalization (see Ch. 4) is required to break down the association between such discriminative cues and sexual outcomes. While weaning these stallions off their discriminative stimuli, changes in routine have to be introduced very slowly.

Learning applies equally in the development of abnormal sexual responses. Many stallions that learn to associate the breeding area with negative experiences (such as harsh discipline) will eventually become problem breeders and will require retraining.30 As a result of inadvertent and inappropriate conditioning, fertile stallions may show minimal libido, so sexual responses are not reliable indicators of fertility.

Sometimes a change of service area can be sufficient to overcome context-specific reluctance to mount.9 Simple changes to management practices that allow greater mobility of the mare and less alteration of her normal estrous posture, seem to make her more attractive and enhance the sexual responsiveness of the stallion.3

Safety concerns are paramount when dealing with breeding stallions and mares, but modification of sexual congress in domestic equids to resemble more closely that of their free-ranging counterparts has been shown to increase sexual arousal and to reverse sexual dysfunction.2

Pharmaceuticals

Descriptions of the effects of numerous pharmaceuticals on stallion behavior appear elsewhere in the literature.35 That said, relatively little is known about endocrine control of reproduction in the stallion, but gonadotropins are considered pivotal in the regulation of libido and spermatogenesis. This is supported by the effects of Antarelix, a potent GnRH antagonist that reduces libido and plasma concentrations of gonadotropins, testosterone and estradiol within 48 hours of administration.43 Gonadotropin and testosterone secretion can be stimulated by GnRH analogues, but chronic treatment can impose a reversible drop in sperm production and libido.44 It has been suggested that because exogenous testosterone proprionate implants reduce spermatogenesis, they may be useful in controlling fertility, for example, in feral horses.45

Anxiolytics may reduce fearfulness in stallions that have developed negative associations with breeding.46 The stimuli that are most commonly responsible for reduced libido are linked to the presence of humans.46 However, the use of anxiolytics in the absence of behavior modification is not recommended.

Some pharmaceuticals have side effects that may profoundly compromise the usefulness of breeding stallions. For example, reserpine has been associated with penile paralysis and paraphimosis, when used repeatedly (5 mg s.c. every 2 weeks for 2 months) to control unmanageable behavior.47 Other agents, such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and pyrimethamine, may affect the pattern and strength of ejaculation (e.g. by altering lumbar flexibility or reducing coordination).48 Anabolic steroids depress luteinizing hormone concentrations and hence libido and semen quality,49 while sometimes causing a simultaneous increase in aggression.9

Castration

In some senses it is possible to consider geldings as domestic analogues of bachelor stallions (e.g. in terms of their testosterone profiles and behavior toward mares). Most castrations occur between 3 months and 2 years of age, and behavior manipulation is cited as the most common reason for the procedure.50 Because early castration increases carpal and tarsal measurements,51 it would be interesting to explore the consequences of pre-pubertal castration on morphology of the brain.

The social rank of geldings often correlates with the age at which they were castrated. This suggests that experience in male horses prior to neutering influences the behavior afterwards.52 But surprisingly, delaying castration until a stallion matures has been demonstrated not to increase the risk of stallion-like behavior after castration.53 Castration reduces the intensity of normal male sexual behavior by reducing testosterone concentrations.54 Houpt55 states that the testosterone concentration of a gelding should be < 0.2 ng/mL. Geldings are more responsive to the pacifying effects of progesterone than are stallions. Approximately 90% of mature stallions show low sexual activity within 8 weeks of castration.56 That said, experienced adult stallions can maintain normal sexual responses for more than a year after castration.53 McDonnell20 estimates that up to 50% of geldings show some stallion-like behavior to mares. Indeed we should not expect castration to eliminate all traits that may be considered characteristic of a harem stallion. After all, some sexual behaviors, including teasing, mounting and performing elements of the elimination marking sequence (see Ch. 9), are frequently observed in foals and adolescents of both sexes.57 Occasionally, geldings in their teens, with normal estrone sulfate and testosterone concentration and no history of use as studs, achieve intromission.58 Such animals may become more libidinous in response to stilboestrol.59

Although the possibility of supplementary hormones generated by the adrenal gland has been raised, aggressive masculine behavior after castration is not usually dependent on hormones.53,56,58 These significant outliers in the distribution of sex-related responses demonstrate that the brains of male horses are masculinized before birth.55 Agonistic responses reinforced prior to castration may also contribute to some of the aggression seen in geldings.60

There is no evidence for the traditionally held belief that epididymal remnants perpetuate sexual responses after castration.61 Because castration of cryptorchids can be difficult, it is possible that some testicular tissue and therefore testosterone production can remain after surgery.62 Plasma estrogen concentrations are useful in discriminating between cryptorchids and geldings.63 In horses over 3 years of age, estrone sulfate concentration is significantly greater (>10 000 pg/mL) where castration is incomplete than in geldings (>10 pg/mL).64 For horses under 3 years of age, a single assay of estrone sulfate is not sufficient to make a definitive discrimination. Instead, blood samples for testosterone concentrations must be taken before and 2 hours after the administration of HCG (10 000 IU i.v.).55 Cryptorchids typically have concentrations >2000 pg/mL, whereas geldings have concentrations <500 pg/mL.55

Chemical castration trials, e.g. using GnRH super agonists to down-regulate the pituitary-gonadal axis, have shown some promise.65 The transient castration of horses is likely to increase the flexibility with which potential breeding animals can be managed.

Masturbation

Many horse breeders traditionally consider masturbation to be an abnormal behavior. However, studies have shown that all free-running male equids, regardless of age, sociosexual environment and harem status, display frequent erections and penile movements (including the penis being bounced against the abdomen) referred to as masturbation, once every 1–3 hours.2 The extent to which penile engorgement and movement are gratifying in a directly sexual sense is questionable. Either way, spontaneous erection and masturbation are now considered normal responses.66 Furthermore it is now accepted that ejaculation is seen in only approximately 0.01% of such erections, thus dispelling the myth that masturbation leads to lower fertility rates.31 Indeed, field and laboratory studies confirm that the levels of spontaneous erection and masturbation are not associated with loss of fertility. Observations of confined stallions have shown that there may be some association between masturbation and REM sleep (see Ch. 10), which occurs only during recumbent rest.67

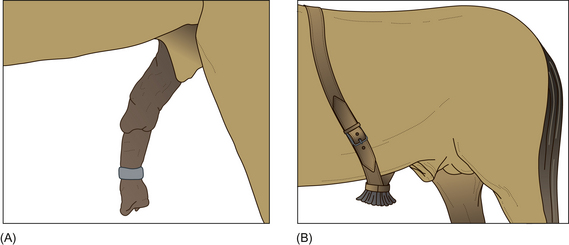

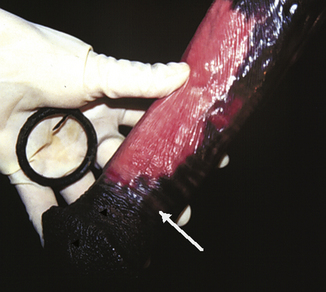

Despite reports that designate the behavior as normal and harmless, many devices exist for discouraging stallions from masturbation (Fig. 11.5). The multiplicity of devices suggests that none of them works universally. Most devices attempt to employ punishment to discourage masturbation. A stallion ring or a brush can be fitted. A stallion ring is a metal or plastic device that is placed on the shaft of the penis, inhibiting erection by physical restriction. The brush is a stiff-bristled brush that is strapped to the belly. These devices can cause abrasions and scarring of the penis (Fig. 11.6).2 It is not surprising to learn that electric shocks have also been employed to modify erections. Anti-masturbation devices rarely reduce spontaneous erection and penile movement, but in many cases increase the frequency and duration of episodes and often cause penile injury.20

Figure 11.5 (A) Stallion ring; (B) brush.

(After McDonnell.2 Redrawn with permission of Sue McDonnell.)

Figure 11.6 A stallion ring (in hand) and penis with a mild circumferential lesion (arrow) caused by abrasion.

(From McDonnell.2 Photograph by Sue McDonnell reproduced with permission.)

Conversely, while arousal may be unwelcome in most horses that are not currently required to mount a mare, it is actively encouraged in teasers. Circumcision of the prepuce and the penile epithelium with subsequent suturing is still practiced in parts of the world to create teasers.68,69

Sexual behavior of male donkeys

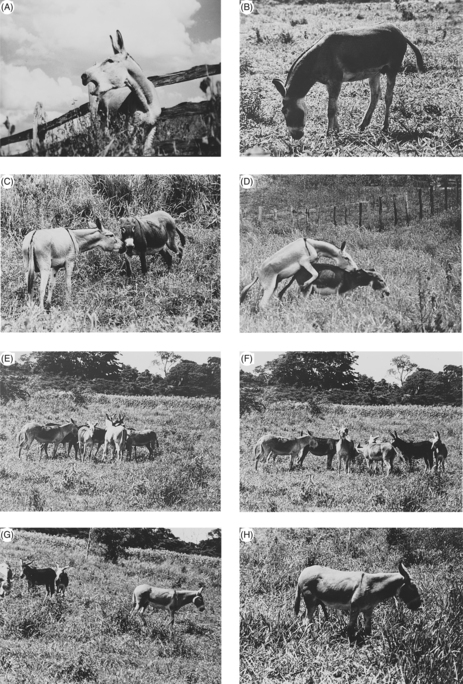

Male donkeys are more likely to be found alone than in an organized social unit.70 They show courtship of a similar duration to that of E. caballus stallions but within a territorial sociosexual structure.71 They also demonstrate significantly more vocalization and posturing (Fig. 11.7) as a prelude to copulation and seem to rely on more overtly active involvement of the female than horses do.72 Several periods of sexual interactions interspersed with periods of male withdrawal from the female’s company are typical.72 It is a characteristic of male donkeys to take their time to mate. Experienced donkey breeders note that this is a delay that can be extended when the jacks detect novel stimuli. Such apparently innocuous differences as the presence of strangers or even particularly strong wind can cause procrastination for hours.73

Figure 11.7 Courtship and copulation in donkeys: (A) vocalization by the jack; (B) jack smelling and/or marking feces or urine; (C) individual teasing of an estrous jenny; (D) mount without erection; (E and F) estrous jennies approaching and teasing the jack; (G) jack retiring from the estrous jennies; (H) jack attaining erection while retired.

(Reproduced, with permission of Elsevier Science, from Henry et al.72)

In some populations, groups of donkeys include subordinate males that are allowed to mate with some of the jennies within the territory of a dominant jack, but this usually takes place only after mating by the dominant jack.74 Subordinate jacks play a useful role in territorial defense and marking the excrement of the jennies.74

Typically jacks develop an erection only after mounting without an erection,75 and as a normal feature of donkey sexual behavior this should be expected in managed matings. That said, for some, erection is most frequently achieved when they stand at a distance from the jennies.75 So experienced breeders of donkeys provide males with sufficient space and liberty to approach and retreat from their jennies during courtship.75

When selecting jacks for interspecies matings it is usual practice to separate them from other donkeys at weaning and rear them with at least one horse. Although requiring closer scientific scrutiny,75 this is said to have a profound effect on their later choice of partner to the extent that it is common for a jack raised in this way to refuse to mate with a jenny.73

Behavior problems in the stallion

Failure in reproductive behavior

Broadly speaking, there are four aspects of failure to perform in the service area: libido, erectile, ejaculatory and coordination (Table 11.3).76 Most classes of dysfunction involve both psychogenic and physical factors that must be addressed at the same time. An interesting technique to help distinguish between the psychogenic and physical causes of impotence is to observe the stallion for nocturnal bouts of masturbation because their absence may help to rule out extraneous impediments to performance such as fear of aversive stimuli in the service area.77

Table 11.3 An overview of the ways in which sexual behavior in the stallion may be compromised or mitigated

GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

The doses are derived from reference material and should be modified according to veterinary clinical assessment. A number of the drugs have additional applications at different doses not discussed in this text.

The serum concentration of testosterone in normal and impotent stallions can be similar.78 Because the causes are not always distinct from one another, there may be some overlap in treatment. In most cases, behavioral approaches are recommended with the occasional need for pharmacological support. As with all behavior manifestations, a clinical examination may reveal a somatic cause or contribution to the problem. For example, as a result of insufficient lubricant (a result of excessive washing or excessive smegma), a stallion that fails to draw may have a reflected penis that engorges within the sheath.3

The web site http://research.vet.upenn.edu/HavemeyerEquineBehaviorLabHomePage/ReferenceLibraryHavemeyerEquineBehaviorLab/LabPublications contains a tremendous amount of information and advice on the behavior and management of stallions. Before attempting to modify the sexual responses of stallions, e.g. for semen collection purposes, readers are advised to visit this site and study the research papers it offers.

Aggression and other handling problems

Prancing and vocalization are normal responses made by a stallion that has seen a mare and should never be discouraged. Nipping and striking are less welcome and can be modified by negative punishment whereby the stallion is led away from the mare or the dummy as an immediate consequence of these responses.79 Aggression by stallions during sexual congress is associated with freshness at the time of the first matings of the season31 or failure to ejaculate.36 Overuse at stud can also result in a stale attitude that manifests as aggression to both mares and handlers.9 That said, offering stallions so many opportunities to mate that they become sated is one approach to the hyperlibidinous state. However, in modifying any unwanted behavior, it is especially important for the breeding stallion to retain desirable (sexual) responses.

When being handled in company (e.g. at a show) stallions are less likely to be aggressive to conspecifics if they are not allowed to sniff other horses’ feces.80 By the same token, the application of odor-masking substances to the nostrils of stallions is reported to make them more tractable under circumstances when stimuli from novel mares are being inadvertently presented.80 When introducing mares to geldings as field mates, it pays to ensure they are not in estrus, since this occasionally precipitates stallion-like responses, including herding and aggression. Male sexual behavior can be reduced with oral (altrenogest) or injectable (medroxyprogesterone acetate) progestins.61

By retrieving straying youngsters and occasionally playing with foals and yearlings, stallions play a role in parenting especially after the first week of life.81 Before then they allow the mare and foal to bond by reducing disturbances. However, although it seems unlikely to have any adaptive significance, infanticide has been reported in Przewalski stallions82 and Camargue horses83 as have isolated incidents of aggression toward foals by domestic stallions and even geldings.61 This may have contributed to the perception that stallions are innately aggressive.17 However, it is worth remembering that, in contrast to donkeys, in which the territorial adult males are dominant over all their conspecifics,84 E. caballus stallions in the free-ranging state are generally not the dominant nor the most aggressive members of natal bands.85 Despite this, the perception that stallions are inherently dangerous and therefore should be isolated prevails in many human traditions.17 If aggression does emerge in the behavioral repertoire of a stallion, it is paradoxically preferable for personnel that he is consistently aggressive rather than being unpredictable.

Hyper-reactive and so-called frenzied stallions benefit from management changes that help to resolve fizzy riding horses. Turn-out and reduced grain intake are especially helpful when used in combination with behavior modification and are always worth trying before hormonal approaches, e.g. use of progesterone or tranquilizers, are attempted.

Self-mutilation

Frustration in stallions restrained from estrous mares can be directed towards personnel, anestrous mares, youngstock and even their own bodies. Self-mutilation shows some seasonality and is most commonly seen in stabled stallions and very occasionally in geldings, mares and foals.61 In stallions, severity can be life-threatening and prevalence can reach 2%.86 Self-mutilation manifests as rubbing, biting, kicking, and lunging into fixed objects. McDonnell86 identifies three categories of self-mutilation based on their putative ontogeny and form. Type I is categorized as a normal behavioral response to intermittent or persistent physical discomfort (such as abdominal discomfort, skin allergies and limb pain) and can be eliminated by relieving the discomfort. Type II, found in males is self-directed inter-male aggression. Characteristically, it involves the elements of the interactive sequence seen in encounters between two stallions. Type III is more typical of a stereotypy, being repetitive, invariant and often rhythmic.

Physical restraint, such as the traditional neck cradle, is largely counterproductive9 and while Shuster & Dodman87 suggest that clomipramine (1.0 mg/kg p.o.) reduces self-biting attempts by approximately 50%, attempts to enrich the animal’s environment are pivotal to successful therapy. Regardless of the type of self-mutilation, treatment should certainly aim to counter environmental factors that trigger the responses. The strategic presentation of ample forage in place of concentrated feed, providing company, preferably equine, and exercise should all be explored86. For type II, treatment should also reflect an understanding of the inter-male interactive behavior of horses. It should not include the use of mirrors, as has been advocated for weavers and box-walkers.

The combined use of stallions as breeding and performance animals has advantages and disadvantages. While helping to meet the behavioral needs of a stallion, exercise also enhances fertility and prolongs a stallion’s working life by maintaining cardiovascular and musculoskeletal fitness.38 By keeping the breeding stallion in ridden work, it may be possible to temper his explosive displays after periods of stabling and maintain his responsiveness to vocal commands. By contrast, there are some data to suggest that forced daily exercise can reduce libido in young stallions.88 Despite the notable exception offered by several world-class stallions, many stallion handlers feel that such attempts to combine work can have deleterious effects on performance or fertility or both. It would be useful to identify the inter-relationships between fertility, biddability and competitive flare.

Summary of Key Points

• Management regimens on studs should meet the behavioral and physiological needs of the stallion and the mare.

• In the free-ranging state, a harem stallion interacts with his mares almost continuously and the mare plays a pivotal role in the timing of copulation.

• The reproductive function of stallions is subject to social modulation.

• Free-ranging stallions protect foals in their natal band.

• If safety can be maintained, increased contact between mares and stallions can reduce the prevalence of unwelcome behaviors in stallions and improve herd fertility.

• Stallions can be allowed to mount without an erection. If it becomes necessary to force a stallion to dismount, this should be accomplished without aversive stimuli that can have unpleasant associations later.

• Allowing the mare to facilitate the stallion’s dismount by walking forward reduces the risks of unwelcome associations with copulation.

• Masturbation is part of the normal ethogram of male horses.

Case study

A 10-year old Dartmoor x Shetland stallion, called Topper, showed a guarding behavior when placed with other horses, especially mares. The absence of good handling allowed this to become a dangerous default response to humans and other animals.

In the year before he arrived at his current home, Topper had killed four dogs as they were walked through his field. Poor fencing allowed him to wander from his paddock on many occasions. His visiting and guarding of other horses in his area had taken him out of his home paddock and this was causing significant disruption in the local village. He had been beaten repeatedly for displays of aggression but this had not helped matters. On the day of his prehension at the request of the police, three experienced personnel and an RSPCA officer spent 6 hours driving him into a corral, then a further 2 hours in the pen with him before they caught him.

Topper was castrated 2 weeks before he arrived at his new home. On arrival at the new home Topper would not tolerate being touched. He was very aggressive when humans in his vicinity engaged eye contact with him, even if they were not approaching him. Rather than run away from such challenges he would, instead, charge straight towards the humans then rear and attempt to strike their heads.

After one month of passive habituation to the presence of humans, Topper would allow two key personnel to enter his yard as he watched suspiciously. He eventually discovered carrots and showed a tremendous liking for them. Carrots were therefore used first as lures that could be shown to him and then given to him if he approached. Soon Topper learned to look for carrots and to follow carrot-bearing humans while remaining a distance of a meter or so behind them. Clicker training (see Ch. 4) was used to shape desirable responses in the presence of humans. Using carrots as primary reinforcers, his responses were shaped so that he remained still with humans around him. Interestingly, because it was clearly rewarding for him, the departure of humans from a zone around him was also offered as reinforcement contingent on the sound of the clicker. This system is akin to the advance-and-retreat method used by many roundpen trainers. It gradually modulated his aggression and allowed him to develop an alternative response when overwhelmed by the proximity of humans: he learned to run away.

After one month Topper was safe with the two people who fed him, as long as they did not corner him. He would tolerate being touched as long as he was approached and handled very slowly. Although he would generally rather not be near people, aggression became extremely rare. However, his owners took the precaution of never allowing children into his box with him. Three years later, he still sounded very much like a stallion when he roared at mares in season in neighboring paddocks but gradually this response tended to occur only in early spring rather than in summer.

Whereas he was initially safe to groom only when tied up, now he can be groomed while standing loose in the stable. His owner notes that as long as Topper is shown each brush before it is used he now seems to quite like being groomed, although she remains convinced that he would prefer to be dirty. The vestiges of head-shyness remain, and handling the ears continues to be a problem.

Although Topper is content in the company of most horses and ponies he is persistently fearful of donkeys. He is kept with a gelding that he mutually grooms but does not guard. Through clicker training, Topper is used for demonstrations of liberty training in which he performs Spanish Walk (see Fig. 4.12) and jumps, bows and rears on command.

References

1. Kaseda Y, Khalil AM. Harem size and reproductive success of stallions in Misaki feral horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1996;47(3/4):163–173.

2. McDonnell SM. Normal and abnormal sexual behaviour. Vet Clin North Am: Equine Pract. 1992;8:71–89.

3. Berger J. Induced abortion and social factors in wild horses. Nature. 1983;303(5912):59–61.

4. McDonnell SM. Stallion sexual behaviour. In: Samper JC, ed. Equine breeding and artificial insemination. London: WB Saunders, 2000.

5. Feh C. Alliances and reproductive success in Carmargue stallions. Anim Behav. 1999;57(3):705–713.

6. Linklater WL, Cameron EZ. Tests for cooperative behaviour between stallions. Anim Behav. 2000;60(6):731–734.

7. Linklater WL, Cameron EZ, Minot EO, Stafford KJ. Stallion harassment and the mating system of horses. Anim Behav. 1999;58(2):295–306.

8. Marinier SL, Alexander AJ, Waring GH. Flehman behaviour in the domestic horse: discrimination of conspecific odours. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1988;19(3–4):227–237.

9. McDonnell SM. Reproductive behaviour of the stallion. Vet Clin North Am: Equine Pract. 1986;2:535–556.

10. Stahlbaum CC, Houpt KA. The role of the flehmen response in the behavioural repertoire of the stallion. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:1207–1214.

11. McDonnell SM, Haviland JCS. Agonistic ethogram of the equid bachelor band. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1995;43:147–188.

12. Melo MIV, Sereno JRB, Henry M, Cassali GD. Peripubertal sexual development of Pantaneiro stallions. Theriogenology. 1998;50(5):727–737.

13. Kaseda Y, Ogawa H, Khalil AM. Causes of natal dispersal and emigration and their effects on harem formation in Misaki feral horses. Equine Vet J. 1997;29(4):262–266.

14. Khalil AM, Kaseda Y. Early experience affects developmental behaviour and timing of harem formation in Misaki horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;59(4):253–263.

15. Khalil AM, Murakami N, Kaseda Y. Relationship between plasma testosterone concentrations and age, breeding season and harem size in Misaki feral horses. J Vet Med Sci. 1998;60(5):643–645.

16. Khalil AM, Murakami N. Effect of natal dispersal on the reproductive strategies of the young Misaki feral stallions. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1999;62(4):281–291.

17. Goodwin D. The importance of ethology in understanding the behaviour of the horse. The role of the horse in Europe. Equine Vet J Suppl. 1999;28:15–19.

18. Anderson TM, Pickett BW, Heird JC, Squires EL. Effect of blocking vision and olfaction on sexual responses of haltered or loose stallions. J Equine Vet Sci. 1996;16:254–261.

19. Houpt KA, Guida L. Flehmen. Equine Pract. 1984;6(3):32–35.

20. McDonnell SM. Reproductive behaviour of stallions and mares: comparison of free-running and domestic in-hand breeding. Anim Reprod Sci. 2000;60–61:211–219.

21. Rees L. The horse’s mind. Sydney: Stanley Paul; 1984.

22. Bristol F. Breeding behaviour of a stallion at pasture with 20 mares in synchronized oestrus. J Reprod Fert Suppl. 1982;32:71–77.

23. Waring GH. Horse behavior. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes, 1983.

24. Waring GH, Wierzbowski S, Hafez ESE. The behaviour of horses. Hafez ESE, ed. The behaviour of domestic animals, 3rd edn., London: Baillière Tindall, 1975.

25. Tyler SJ. The behaviour and social organisation of the New Forest ponies. Anim Behav Monogr. 1972;5:85–196.

26. Asa CS, Goldfoot DA, Ginther OJ. Sociosexual behaviour and the ovulatory cycle of ponies (Equus caballus). Hormones Behav. 1979;13:49–65.

27. Kosiniak K. Characteristics of the successive jets of ejaculated semen of stallions. J Reprod Fert Suppl. 1975;23:59–61.

28. Feist JD. Behaviour of feral horses in the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range. PhD thesis, University of Michigan; 1971.

29. Clay CM. Influences of season and artificial photoperiod on reproduction in stallions. Diss Abstr Int B Sci Eng. 1989;49(8):2941.

30. Pickett BW, Voss JL, Squires EL. Impotence and abnormal sexual behaviour in the stallion. Theriogenology. 1977;8:329–347.

31. Tischner M, Tomica E, Jezierski J. Age and seasonal effects on sexual behaviour of stallions at rest. Anim Reprod Sci. 1986;12(3):233–237.

32. Umphenour NW, Steiner JV. Breeding of the Thoroughbred stallion. In: Samper JC, ed. Equine breeding and artificial insemination. London: WB Saunders, 2000.

33. McCarthy PF, Umphenour NW. Management of stallions on large breeding farms. Vet Clin North Am: Equine Pract. 1992;8:219–235.

34. Clement F, Plongere G, Magistrini M, Palmer E. Appréciation de la fonction sexuelle de l’étalon. Le Point Veterinaire. 1998;29(191):343–348.

35. McDonnell S, Garcia MC, Kenney RM. Pharmacological manipulations of sexual behaviour in stallions. J Reprod Fert Suppl. 1987;35:45–49.

36. Ginther OJ. Sexual behaviour following introduction of a stallion into a group of mares. Theriogenology. 1983;19:877–886.

37. Vesserat GM, Cirelli AA, Jnr. Stallion behaviour. Equine Pract. 1996;18:29–32.

38. Tischner M. Patterns of stallion sexual behaviour in the absence of mares. J Reprod Fert Suppl. 1982;32:65–70.

39. Steinbjkornsson B, Kristjansson H. Sexual behaviour and fertility in Iceland horse herds. Pferdeheilkunde. 1999;15(6):481–490.

40. Lindsay FEF, Burton FL. Observational urine testing on the horse and donkey stallion. Equine Vet J. 1983;15(4):330–336.

41. Anderson TM, Pickett BW, Heird JC, Squires EL. Effect of blocking vision and olfaction on sexual responses of haltered or loose stallions. J Equine Vet Sci. 1996;16(6):254–261.

42. Wierzbowski S. The sexual reflexes of stallions. Roczniki Nauk Rolniczych. 1959;73(B-4):753–788.

43. Hinojosa AM, Bloeser JR, Thomson SRM, Watson ED. The effect of a GnRH antagonist on endocrine and seminal parameters in stallions. Theriogenology. 2001;56(5):903–912.

44. Boyle MS, Skidmore J, Zhang J, Cox JE. The effects of continuous treatment of stallions with GnRH analogue. J Reprod Fert Suppl. 1991;44:169–182.

45. Kirkpatrick J, Turner JW, Perkins A. Reversible chemical fertility control in feral horses. J Equine Vet Sci. 1982;2(4):114–118.

46. McDonnell S, Kenney RM, Meckley PE, Garcia MC. Novel environmental suppression of stallion sexual behaviour and effects of diazepam. Physiol Behav. 1986;37:503–505.

47. Memon MA, Usenik EA, Varner DD, Meyers PJ. Penile paralysis and paraphimosis associated with reserpine administration in a stallion. Theriogenology. 1988;30(2):411–419.

48. Bedford SJ, McDonnell SM. Measurements of reproductive function in stallions treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and pyrimethamine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1999;215(9):1317–1319.

49. Squires EL, Todter GE, Berndtson WE, Pickett BW. Effect of anabolic steroids on reproductive function of young stallions. J Anim Sci. 1982;54(3):576–582.

50. Moll HD, Pelzer KD, Pleasant RS, et al. A survey of equine castration complications. J Equine Vet Sci. 1995;15(12):522–526.

51. Heusner GL, Pope JB, Crowell-Davis SL, Caudle AB. The effect of prepubertal castration on the growth and behaviour of colts. In: Proceedings of the 15th Equine Nutrition and Physiology Symposium, Fort Worth, Texas, 1997. Savoy, USA: Equine Nutrition and Physiology Society Publications; 1997: 223–224.

52. Van Dierendonck MC, Devries H, Schilder MBH. An analysis of dominance, its behavioural parameters and possible determinants in a herd of icelandic horses in captivity. Neth J Zool. 1995;45(3–4):362–385.

53. Line SW, Hart BL, Sanders L. Effect of prepubertal versus postpubertal castration on sexual and aggressive behaviour in male horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186(3):249–251.

54. Thompson DL, Pickett BW, Squires EL, Nett TM. Sexual behaviour, seminal pH and accessory sex gland weights in geldings administered testosterone and (or) estradiol-17 beta. J Anim Sci. 1980;51(6):1358–1366.

55. Houpt KA. Is there life after castration? In: Harris PA, Gomarsall GM, Davidson HPB, Green RE, eds. Proceedings of the BEVA Specialist Days on Behaviour And Nutrition, Newmarket, Suffolk, UK, 1999: 15–16.

56. Berbish EA, Ghoneim IM, Mousa SZ, Attia MZ. Effect of castration on sexual and aggressive behaviour on male horses. Vet Med J Giza. 1996;44(2B):535–539.

57. McDonnell SM, Poulin A. Equid play ethogram. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2002;78(2–4):263–295.

58. Cox JE. Behaviour of the false rig: causes and treatments. Vet Rec. 1986;118(13):353–356.

59. Lunaas T. Libidinous behaviour in gelding exacerbated by stilboestrol. Norsk Veterinaertidsskrift. 1980;92(2):116.

60. England G. Allen’s fertility and obstetrics in the horse, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1996.

61. Crowe CW, Gardner RE, Humburg JM, et al. Plasma testosterone and behavioural characteristics in geldings with intact epidymides. J Equine Med Surg. 1977;1:387–390.

62. Trotter GW, Aanes WA. A complication of cryptorchid castration in three horses. Am J Vet Med Assoc. 1981;179:246–248.

63. Ganjam VK. An inexpensive, yet precise, laboratory diagnostic method to confirm cryptorchidism in the horse. In: Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Convention of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, Vancouver, bc 1977. C/o Dr FJ Milne, Ontario Veterinary College, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, 1978: 245–248.

64. Ekmann A, Lehn-Jensen H, Fjeldborg J. [A systematic clinical examination method for diagnosis of presumed equine cryptorchidism] (Danish). Dansk Veterinaertidsskrift. 2000;83(21):6–14.

65. Johnson CA, Thompson DL, Cartmill JA. Effects of deslorelin acetate implants in horses: Single implants in stallions and steroid-treated geldings and multiple implants in mares. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:1300–1307.

66. McDonnell SM, Henry M, Bristol F. Spontaneous erection and masturbation in equids. In: Equine reproduction V: Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on equine reproduction. Journals of Reproduction and Fertility Ltd, Cambridge, CB5 8DT, UK; 1991: 664–665.

67. Wilcox S, Dusza K, Houpt KA. The relationship between recumbent rest and masturbation in stallions. J Equine Vet Sci. 1991;11(1):23–26.

68. Silva LAF, Fioravanti MCS, Marques Junior AP, Melo MIV. Evaluation of the sexual behaviour of Managalarga stallions circumcised to prevent extension of the penis. Revista Brasileira de Reproducao Animal. 1994;18(3–4):110–115.

69. Silva LAF, Carneiro MI, Fioravanti MCS, et al. Creation of stallion teasers by shortening of the penis by circumcision. Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinaria e Zoootecnia. 1995;47(6):789–798.

70. Rudman R. The social organisation of feral donkeys (Equus asinus) on a small Caribbean island (St. John, US Virgin Islands). Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(2–3):211–228.

71. Henry M, McDonnell SM, Lodi LD, Gastal EL. Pasture mating behaviour of donkeys (Equus asinus) at natural and induced oestrus. J Reprod Fert Suppl. 1991;44:77–86.

72. Henry M, Lodi LD, Gastal MMFO. Sexual behaviour of domesticated donkeys (Equus asinus) breeding under controlled or free range management systems. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(2–3):263–276.

73. Taylor TS, Matthews NS. Mammoth asses – selected behavioural considerations for the veterinarian. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(2–3):283–289.

74. McCort WD. The behavior and social organization of feral asses (Equus asinus) on Ossabaw Island, Georgia. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, 1980.

75. McDonnell SM. Reproductive behavior of donkeys (Equus asinus). Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(2–3):277–282.

76. Klug E, Bartmann CP, Gehlen H. Diagnosis and therapy of copulatory disorders in the stallion. Pferdeheilkunde. 1999;15(6):494–502.

77. McDonnell SM, Hinze AL. Aversive conditioning of periodic spontaneous erection adversely affects sexual behavior and semen in stallions. Animal Reproduction Science. 2005;89:77–92.

78. Wallach SJR, Pickett BW, Nett TM. Sexual behaviour and serum concentrations of reproductive hormones in impotent stallions. Theriogenology. 1983;19(6):833–840.

79. Hurtgen JP. Breeding management of the Warmblood stallion. In: Samper JC, ed. Equine breeding and artificial insemination. London: WB Saunders, 2000.

80. Saslow CA. Understanding the perceptual world of horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2002;78(2–4):209–224.

81. McDonnell SM. The equid ethogram: a practical field guide to horse behavior. Lexington, KT: The Blood Horse, 2003.

82. Boyd L. Behaviour problems of equids in zoos. Vet Clin North Am: Equine Pract: Behav. 1986:653–664.

83. Duncan P. Foal killing by stallions. Appl Anim Ethol. 1982;8:567–570.

84. Klingel H. Observations on social organization and behaviour of African and Asiatic Wild Asses (Equus africanus and Equus hemionus). Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(2–3):103–113.

85. Houpt KA, Keiper R. The position of the stallion in the equine hierarchy of feral and domestic ponies. J Anim Sci. 1982;54:945–950.

86. McDonnell SM. Practical review of self-mutilation in horses. Animal Reproduction Science. 2008;107:219–228.

87. Shuster L, Dodman N. Basic mechanisms of compulsive and injurious behaviour. In: Dodman NH, Shuster L. Psychopharmacology of animal behaviour disorder. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 1998:185–220.

88. Dinger JE, Noiles EE. Effect of controlled exercise on libido in 2-year-old stallions. J Anim Sci. 1986;62(5):1220–1223.