Chapter 15 Miscellaneous unwelcome behaviors, their causes and resolution

Introduction

Physical causes of unwelcome behavioral responses should always be ruled out before any purely behavioral therapy is adopted. Painful lesions and other physical abnormalities should be eliminated because beyond their effects on horse welfare and development of annoying habits, they are likely to compromise athletic output (Fig. 15.1). For example, it has been proposed that undiagnosed pelvic or vertebral lesions could be important contributors to poor performance in horses.1 While occasional disorders such as ‘cold-back syndrome’ and the relationship between dental problems and behavior under-saddle have yet to be thoroughly explored, the treatment of most physical disorders that reduce performance is considered in detail in the veterinary literature.

Figure 15.1 A horse making a so-called dirty stop (getting very close to a fence before refusing). Horses refusing fences may have learned that they are physically unable to clear the top rail or that landing is a painful consequence of taking off.

(Photograph courtesy of Sandra Hannan.)

Since most problem behaviors that emerge in stables or at pasture are considered elsewhere in this book, the current discussion will focus on handling problems and problems with the ridden horse. In combination with Chapters 1, 4 and 13, this chapter aims to help veterinarians and equine scientists in their creation, from first principles, of humane and effective therapies for unwelcome behaviors. The current chapter indicates the basic approaches to therapy that can be tailored for each affected horse, defines some of the more common problems and offers a framework for understanding the origins of these problems.

Unfortunately, as discussed in Chapter 13, there is a lack of scientific data in these realms. This may reflect the importance we place upon the performance of the horse under-saddle and the consequent development of riding instruction that tends to focus on outcomes rather than mechanisms. Since the ideals of equestrian technique combine art and science, students of equitation encounter measurable variables such as rhythm, tempo and outline alongside many more elusive qualities such as so-called submission.2,3 This mixture and the dearth of mechanistic substance frustrate attempts to express equestrian technique in empirical terms4 and account for some of the confusion and conflict that arises in many human–horse dyads. With time, the application of science to the plethora of undesirable behaviors that horses trial and learn to adopt will undoubtedly reduce the ill-considered demands for quick fixes and ultimately decrease the wastage in the industry. In terms of prevention, we will, in time, fully appreciate the importance of consistent, low-stress foundation training as the bedrock of any horse’s training and the best means of avoiding dangerous traits subsequently emerging.

Mechanical approaches

Most naïve horses respond to humans as they would to any predator. They behave in ways that help them avoid physical or psychological pressure, by moving away bodily or posturally. These basic evasive responses can be modified successfully to produce a highly responsive equine performer or unsuccessfully to produce a problem horse.

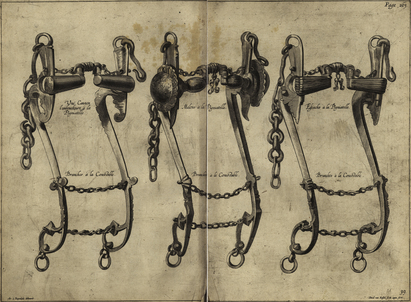

When trainers encounter horses that rapidly enter conflict and as a result do not comply, they often experiment with increased pressure to overcome resistance. Mechanical restraints and stimulants may be used to magnify the pressure that riders can apply. Because of the perceived need to force horses into an ‘outline’ and make them work ‘on the bit’ (see Glossary), the tendency is to use ever-stronger bits as the first approach to solving any resistance. This accounts for the multiplicity of bits on the market. As with any device, it is true to say that if there are many of them available, the chances are that none of them provides all the answers. Furthermore, enlightened trainers recognize that where aversive stimuli have failed to elicit the desired response and have begun to cause behavioral conflict, the application of more force is contraindicated. They rarely reach for such gadgets.

Frustrated trainers often try bits that apply pressure to different parts of the mouth or to the same area of the mouth but with greater severity (Fig. 15.2). Even though they can and sometimes do sever the tongue,5 saw-chain bits (so-called mule bits and correction bits) are readily available to riders who are having problems getting horses to respond to milder bits. If changing or increasing mouth pressure is unsuccessful, an alternative or additional means of making the horse adopt the desired shape is to apply pressure to other parts of the head, so training devices such as curb chains, gags, hackamores, bosals, draw reins, balancing reins and chambons may be employed. Unfortunately the tendency is to develop a reliance on these extra pulleys, rather than use them solely for retraining as the name might imply. Martingales and tie-downs are similar in that they apply pressure to prevent evasive raising of the head and are rarely dispensed with.

Figure 15.2 Etching of 18th-century bits. At times it seems that more effort has gone into designing bits than addressing poor equitation.

If the horse fails to show sufficient forward movement or impulsion, trainers direct their attention to the flanks where they can increase the pressure and more effectively drive the horse forward or simply away from the rider’s leg using whips and spurs. Although, for some, these stimulants are distasteful, they are not necessarily contraindicated since they can be used with subtlety and employed transiently to empower the rider’s leg signals. In contrast, tying horses’ heads down (with side reins and draw reins) and clamping their jaws shut with nosebands6 are counter-productive in the long term. Indeed there is growing concern that these approaches can automatically compromise welfare by virtue of their inflexibility and inherent absence of pressure-release.7

Behavior modification

Behavior therapy can help overcome undesirable equine responses that may have an innate component but are largely learned. The temptation may be to treat such traits in isolation. However, a holistic approach has tremendous merit since better results tend to occur if the human–horse relationship is nurtured when the rider is both on the ground and in the saddle. Time spent training horses in-hand seems to pay dividends even in the ridden horse,8 presumably through a process of generalization. Achieving stimulus control in-hand seems to facilitate stimulus control under-saddle.9 Inter-specific communication may help horses overcome fear and therefore reduce their tendency to use counter-predator responses. It is important that the translation of trained responses from cues in-hand to cues under-saddle is better understood by practitioners. It may simply be that an unconfused horse in-hand is a better prospect for training than a confused one. In any case, correctly identifying the effects of reduced confusion and fear and distinguishing stimulus control from mere compliance may allow us to describe and even measure the bonds that form between horses and their trainers.

By the same token, punishment is regarded by many owners as unenlightened, since it presupposes that horses know the difference between good and bad behavior. So, it is increasingly inappropriate for veterinarians to advocate punishment as a response to undesirable behavior in the horse. It undermines the human–horse bond and carries the risk of injury, which may place any practitioner who advises it in a legally liable position. Examples of acceptable techniques used for behavior modification include habituation and counter-conditioning (see Chs 4 and 13). Habituation is the key to overcoming fear-related responses such as traffic shyness but it can be expedited with counter-conditioning, an approach that relies heavily on the shaping of alternative responses through operant conditioning (see also Fig. 15.3). At its most elegant, equine operant conditioning takes the form of positive reinforcement and subtle negative reinforcement. Consistent use of negative reinforcement is the key to retraining the basics, but is notably more likely to work in horses that have not habituated to pressure. Techniques for restoring sensitivity to pressure cues demand exquisite timing of pressure-release. Meanwhile, clicker training employs positive secondary reinforcement that is particularly useful for refinement of responses, once negative reinforcement has established the basics.

Figure 15.3 Horse being clipped in the presence of food – an example of counter-conditioning.

(Reproduced with permission of Australian Equine Behaviour Centre.)

Horses with innate or learned evasion responses may have the rewarding outcomes of these responses removed by a process of extinction. Furthermore they can be trained to associate the fear-eliciting stimuli with positive outcomes in the same way that laboratory primates can be trained to voluntarily present their forelimbs for intravenous injections. (A case study that required a pony to learn to cope with hypodermic injections appears at the end of this chapter. It followed the injection desensitization training technique developed by ethologists at Pennsylvania State University.10) A far less humane approach to fearful horses is to flood them by exposing them to an overwhelming amount of the fear-eliciting stimulus in the hope that their responses are exhausted. For example, so-called ‘tarping’, a method of breaking by flooding, involves evoking learned helplessness by casting the horse, covering it with a tarpaulin and beating it until it no longer resists.

Practitioners are strongly encouraged to become extremely conversant with learning theory (see Ch. 4) before counseling owners on the application of these techniques. All of the undesirable responses in the current chapter can be remedied by behavior modification. But a prerequisite is to correctly identify the motivation for a given response. Readers are urged to consider the ethological content of this entire volume when determining causal factors. Beyond that the success of behavioral therapy depends on the consistency of administration and compliance of owners, who must be counseled that the latency for desirable outcomes depends largely on the number of times the horse has trialed and learned from the unwelcome response. With a thorough knowledge of learning theory, practitioners can customize behavior modification programs, modify advice in the light of initial responses and counsel owners when proximate results surprise the uninitiated. So, for example, when as a result of an extinction protocol, undesirable responses become more frequent, the accomplished student of learning theory can explain that this is a manifestation of the frustration effect (see p. 103 in Ch. 4) and that it is transient.

Handling problems

As discussed in the previous chapter, physically restraining horses during painful procedures is often possible but rarely preferable to chemical restraint since it tends to escalate the aversiveness of the procedure and is therefore ultimately likely to compromise the horse–human bond and make the horse less compliant for future procedures. Many handling problems are the legacy of previous (often unintentional) abuse. Others can have proximate causes in physical pathologies, so practitioners should always check first (with an examination and a thorough case history) for the involvement of these anomalies before embarking on any course of behavior therapy, e.g. a horse that is reluctant to step backwards must be checked for wobbler syndrome.

Horses fearful of clippers may have had a cutting injury or heat damage during clipping. Head shyness can be the manifestation of partial blindness, dental anomalies and, occasionally, spinose ear ticks.11 Girthing and saddling problems may be related to thoracic and spinal lesions. Horses that are eager to rub their heads against handlers may have lice or, very occasionally, flying insects or spinose ear ticks that make them generally itchy and sometimes irritable. In a similar vein, when acute in onset, hypersensitivity to being touched may be attributed to strychnine poisoning and even lightning strike.11

Assuming that painful pathologies have been ruled out, the role of learning is of tremendous significance in emergent handling problems. Horses showing fear of veterinarians may simply remember them as the immediate precursors of pain or of unpleasant physical restraint prior to painful interventions. Similarly, those showing fear of farriers (Fig. 15.4) may have received a nailing injury in the past. The horse’s ability to form general relationships between certain activities and pain should not be overlooked. For example, painful lesions (e.g. subclinical orthopedic disorders that are exacerbated by riding) may make a horse generally reluctant to work and, by a process of backward chaining (see Ch. 4), difficult to catch.

As with all behavior problems, it is the responsibility of handlers and therapists alike to establish that the horse is not only capable of an appropriate response but that it is also free from pain. Furthermore, the horse must know what is being asked of it, i.e. it must have learned the cue. Only when these prerequisites are in place can the horse be helped to unlearn the inappropriate associations (Table 15.1). Techniques in behavioral therapy can be used in combination so the suggestions that appear in Table 15.1 should not be considered the complete or sole approach. Attention to the horse’s dietary, social and environmental needs helps to advance the effects of appropriate behavior modification.

Table 15.1 Common handling problems, their interpretation and suggested approaches to therapy that can be employed after any primary physical causes have been removed

| Problem | Interpretation | Approaches to therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Barging (trampling) | ||

| Biting and bite threats |

• Total refurbishment of the human–horse bond,a e.g. experienced personnel may make great strides with such horses in a roundpen |

|

| Claustrophobia | ||

| Difficult to bridle | ||

| Difficult to saddle-up | ||

| Difficult to shoe |

• Extinction of fear responses by habituation and counter-conditioning • Clicker training of appropriate responses, such as approaching farriers and their equipmentc |

|

| Dislike of grooming |

• Counter-conditioningb |

|

| Fear of being clipped | ||

| Fear of veterinarians | ||

| Hard to catch |

• Clicker training of appropriate responses such as approaching personnelc • Extinguish associations with being removed from group. Therefore habituate the horses to being caught but not necessarily brought in from the paddock or ridden |

|

| Head rubbing | ||

| Head shyness |

• Clicker training of appropriate responses such as approaching personnel, especially their hands and hand-held equipmentc |

|

| Kicking and kick-threats | ||

| Pulling |

• Reinstall leading cuesd |

|

| Pushing |

• Reinstall leading cuesd |

|

| Rearing |

• Reinstall leading cuesd |

|

| Refusal to back |

• Reinstall leading cuesd |

|

| Refusal to leave company | ||

| Refusal to load | ||

| Refusal to stand while being mounted | ||

| Striking |

a Refurbishment of horse–human bond is also discussed in the case study in Chapter 11, p. 252.

b Counter-conditioning is explained on p. 89 (see Ch. 4) and also in the case study at the end of the current chapter, p. 338.

c Clicker training is explained on p. 97 (see Ch. 4).

d Reinstallation of leading cues is explained in Chapter 13 and highlighted in the case study in that chapter on p. 304.

Problems with the ridden horse

Horses can demonstrate various unwelcome behaviors under-saddle, often in combination. However, for the sake of simplicity, inappropriate responses are considered separately in this chapter.

Inappropriate obstacle avoidance

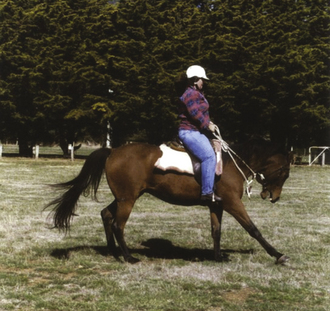

It is appropriate for horses to avoid hazards that may jeopardize their safety, but such innate self-preservation responses sometimes inconvenience riders (Fig. 15.5). Examples include avoidance of ground hazards, manifested as running out and refusal of fences, ditches and water jumps, while avoiding lateral confinement may prompt a horse to refuse to enter starting stalls. Unfortunately, the original causes of these responses may be obscured and the subsequent application of aversive stimuli may simply confirm to the horse the need to avoid such obstacles because they become associated with pain.

Figure 15.5 A horse avoiding obstacle despite (or perhaps even as a result of) the efforts of a novice rider.

(Photograph courtesy of Mellisa Offord.)

In other words, riders and handlers may focus on a given hazard and, through the use of pressure cues, may inadvertently make it increasingly aversive. It is therefore preferable to first work on deficits in the quality of operant responses such as leading to a light cue and straightness in less challenging contexts. Again, the sequential steps in a linear scale of training (see Ch. 13) should end in proof only after the preceding steps in the scale have been achieved repeatedly. Shying behavior is most rapidly learned and incorporated into the horse’s behavioral repertoire when it permits complete escape. As the horse escalates its shying behavior, the reinforcement from escape is compounded by the incremental loss of control by the rider.2 Additionally, riders who predict the responses may inadvertently apply pressure that may increase the horses’ motivation to find freedom.2 Re-training the ‘go’ response in such horses (see Ch. 13) is the preferred remedial course of action.

The importance of rhythm and direction in basic training is explained when one considers horses that learn to refuse jumps. Habitual losses of rhythm and tempo or directional line often lead to stalling while approaching fences.2 When horses learn to stall in the jumping effort, outright refusal is generally their next step.

Hyper-reactivity responses

While innate obstacle avoidance responses may paradoxically help to ensure the safety of riders (e.g. by prompting the horse to steer around a hazard unseen by its rider), other innate self-preservation action patterns of horses, especially those that keep them safe from predators, are sometimes triggered too readily or are performed with speed that riders are unable to predict. These are chiefly flight responses motivated by a need to get away from the stimulus, rejoin a group of conspecifics or return to the home range. Depending on the human observer, horses that readily offer theses responses are variously described as sharp, keen, fizzy or flighty.12 Of course, these labels blame the horse rather than identifying deficits in its training.

There are several common examples of hyper-reactivity in the ridden horse. As discussed above, shying is an avoidance response that sends horses leaping laterally or backwards away from auditory, olfactory or visual stimuli. Many horses in unfamiliar surroundings offer this response innately but some adopt it as their default response to novelty. Traffic shyness is a particularly important example. The most successful approach to this dangerous problem involves a process of habituation, but the challenge for trainers is to present a comprehensive range of diverse stimuli (a model for habituating former racehorses appears in the case study in Ch. 4).

Jogging, on the other hand, is largely learned and manifests as a horse that is unresponsive to signals to walk (Fig. 15.6). This undesirable gait is often accompanied by persistently repeated extension of the neck to pull the reins through the rider’s hands in horses that have learned to ‘pull’. These horses demonstrate a clear need for reinstallation of the ‘stop’ cue. Similar unresponsiveness takes an extreme form in horses that bolt, i.e. that gallop with no response to rein pressure. These animals may learn to ignore bit pressure whenever they wish to remove themselves from a perceived threat or return to their home range or social group.

Agonistic responses to conflict

When faced with discomfort or a threat, most horses move away. If horses cannot escape from such a stimulus, they enter behavioral conflict and increase their kinetic effort in a bid to relieve the pressure (Table 15.2). Some horses develop seemingly irrational phobias by becoming sensitized to associated stimuli and anticipating the escalation of bit or leg pressure that riders use to make them ‘behave’. The therapeutic approach to conflict is discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

Table 15.2 Selected examples and descriptions of agonistic responses to conflict

| Response | Description |

|---|---|

| Bucking | Response used to fight conspecifics and dislodge predators |

| Rearing | Response used to fight conspecifics and predators |

| Balking, bolting home, napping and jibbing | Motivation to return to home range or social group is greater than motivation to respond to rider’s signals |

| Rushing fences | Although the behavioral mechanism is unclear, horses choosing to travel too rapidly toward fences are thought to be making a perverse attempt to reduce the aversiveness of the stimulus by running towards it |

| Falling out through the shoulder | Failure to turn appropriately on command |

Evidence of pain and irritation

When a horse fails to respond as requested by the rider, the innate human tendency is to repeat the cue with greater force in a bid to increase the animal’s motivation to relieve the pressure. However, it is important that somatic causes of a horse’s disinclination to respond are eliminated before more aversive stimuli are applied. There is a strong argument for the attending veterinarian to use analgesics as a diagnostic probe when horses fail to respond appropriately, especially if this departure is sudden. Pain is recognized as an important contributor to unwelcome behavioral responses.13 Occasionally horses may learn to relieve pressures caused by riders by removing the riders themselves, e.g. by bucking (Fig. 15.7), rolling or even rubbing the riders against fixed objects.

Gentle snorting is usually a good sign in horses under-saddle because it tends to be accompanied by signs of relaxation such as spontaneous head lowering. In contrast, grunting and groaning are expiratory noises associated with tenesmus and abdominal guarding. As such they reflect low-grade discomfort in the very general region of the horse’s forequarters. Far more profound an indication of thoracic and lumbar pain is seen in ‘cold-back’ syndrome during girthing and mounting. This often includes responses to being saddled, mounted and especially to being girthed that vary from aggression to recumbency.

Horses commonly learn to reduce the discomfort of the bit by manipulating it to lie in relatively insensitive parts of the mouth. Common names for these evasions include raking, boring, getting the tongue over the bit and seizing the bit between the teeth (Fig. 15.8). Mouth pain is usually associated with heavy-handed riding or inappropriate equipment, e.g. the action of some jointed bits is thought to cause pinching between the commissures of the lip and the second premolar. Some maintain that in the event of a horse fighting the bit, comfort in this part of the mouth can be maximized by creating a ‘bit seat’ or ‘cheek seat’, i.e. removing an appreciable portion of the second premolar.14 While one study reported improved athletic performance in most horses after the creation of bit seats,14 an abiding question is whether a simple change of bits (e.g. to an unjointed design) would be just as effective. Alarmingly, some overzealous equine dentists suggest that partial tooth removal should be considered for all horses that are required to wear double birdles. This is an outrageous suggestion since it effectively means that all horses competing in elite dressage should be surgically altered in this way. The use of double bridles (and the jaw-clamping nosebands that are frequently used with them)6 should be questioned before horses’ dental arcades are routinely modified to accommodate them.

Evidence of poor physical ability

While some horses do not comply with riders’ signals because they associate the responses desired by riders with musculoskeletal discomfort, others are insufficiently athletic because of poor conformation or lack of fitness (Table 15.3). Clearly, as with those resulting from pain, these cases are unresponsive to behavior therapy. It is also worth checking that riders are giving signals in consistent anatomical sites, e.g. lack of consistency can explain why a short-legged rider may fail to prompt a satisfactory ‘go’ response from a horse that has previously been ridden only by long-legged riders.

Table 15.3 Selected examples of inadequate performance under-saddle that reflect poor physical ability

| Response | Description |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | Lack of energy as distinct from lack of willingness to respond |

| Problems in transition | Congenital propensity, e.g. to disunite at the canter (see Glossary) |

| Tripping, toe-dragging, stumbling and clumsiness | Poor locomotion due to fatigue, conformation or excessive hoof growth |

| Forging, clicking and over-reaching | Inappropriate farriery, conformation problems and inattentive equitation |

| Brushing, speedy cutting and dishing | Inappropriate farriery and conformation problems |

| Hitting fences | Failure to elevate limbs, especially the leading foreleg, while jumping |

Evidence of learned helplessness

Horses may learn that they are unable to help themselves when responses they use to relieve pain or discomfort or threats (or their precursors) are unsuccessful. By a process of habituation, such horses often become unresponsive to the stimuli, but it is unclear whether they all do so with a concurrent reduction in physiological distress.

Horses that exhibit general reluctance to work and resistance to signals from the rider are described as ‘stale’ or ‘sour’. Specifically they may be referred to as being hard-mouthed (Fig. 15.9) or lazy and sluggish, whereas, more correctly, they should be considered to have habituated to rein pressure or leg pressure, respectively. It is difficult but not impossible to re-educate these horses (see Ch. 13). Classically, animals that have learned helplessness are generally unresponsive to multiple stimuli in their environment, not just training-related stimuli.

Causes of unwelcome responses in the ridden horse

Two broad sections are proposed here: unwelcome behavioral responses caused directly by humans, and those attributable more to the horse than the rider. However, it is accepted that while the dichotomy is not absolute, the responsibility for equine behavior problems ultimately lies with humans, since we have undertaken the domestication and exploitation of equids. Because humans are so directly involved in the first group, it is likely that interventions such as behavior therapy are more likely to work in these cases.

Human causes of unwelcome behavioral responses

Some unwelcome responses disappear if management deficiencies are corrected or if the rider becomes more skilled or is replaced by a more talented equestrian. Horses learn to evade discomfort in both appropriate and inappropriate ways. Sometimes, for example in rodeos, horses are required to produce exaggerated agonistic responses as part of their work. Indeed Schonholtz15 points out that some horses are purpose-bred for a heightened anti-predator response (e.g. one line of buckers accounted for 30 horses used at the US National Rodeo Finals in 1996). While this is claimed by some to be evidence for the increasingly humane treatment of rodeo animals, it may simply indicate that hypersensitive horses can be bred. This means that selected animals are less likely to habituate to being ridden with a bucking strap in place because they continue to find the procedure aversive. So purpose breeding seems an unconvincing justification for the use of selected rodeo animals on welfare grounds.

While schooling in the form of operant conditioning can make a horse respond desirably, it can also evoke resistance, conflict and learned helplessness when administered crudely, inconsistently or too rapidly.16 Avoiding and resolving problems in the ridden horse have both already been explained in Chapter 13.

Poor riding technique

The importance of rider position is always stressed in riding manuals, with good reason (see Fig. 7.24). Without this prerequisite, riders attempt to maintain or resume a centered position and usually have a significant effect on the horse’s movement and balance in the short term (Fig. 15.10). In the long term, a rider’s lack of balance allows the horse to practice unrequested responses. The more opportunities the horse has to trial responses that are not under stimulus control, the greater it perceives its freedom from the control of the rider. This allows an escalating series of random behaviors to be trialed and possibly reinforced. These tendencies, in turn, can affect a rider’s confidence and thus prompt the emergence of a so-called defensive seat, characterized by a forward tilt of the upper body with excessive rein contact and some gripping with the lower legs. For these reasons, novice riders should never be paired with uneducated horses.

Figure 15.10 An inexperienced rider showing lack of balance, with the hands uneven and the legs placed too far forward. Typically these characteristics predispose the rider to being ‘left behind’ the horse whenever it moves forward with unexpected speed, an outcome that prompts many novices to compensate by using the reins to balance.

(Photograph courtesy of Sandro Nocentini.)

Poor application of learning theory

Although horses are adaptable and therefore tolerant of poor handling and training, this does not obviate the need to use tact and sensitivity when applying aversive stimuli. Punishment and inappropriate negative reinforcement are prevalent because few riders appreciate the importance of learning theory (Table 15.4).

Table 15.4 Common rider faults that demonstrate poor application of learning theory and may serve to confuse horses

| Rider fault | Example |

|---|---|

| Nagging | Repeated application of aversive stimuli regardless of response |

| Poor timing | Application of signals after the response has been offered |

| Inconsistency | Failure to relieve pressure to reinforce every desirable response |

| Failure to reinforce | Ignorance of the need to relieve pressure |

| Inappropriate punishment | Punishment for fear responses |

| Poor balance | Inability of the rider to balance without signaling to the horse |

| Pursuit of style at the expense of other appropriate goals | Prioritizing desirable outline over self-carriage |

Unrealistic expectations

As the commercial value of a horse is often related to its ability to compete, many owners seek to push their horses to the limits of their performance. When the expectations of the owners are not met, this may account for some abiding dissatisfaction and the application of interventions that can elicit conflict. Coercion is ineffective and inhumane when the real problem is ignorance of the true limitations of the horse’s ability. For example, although the majority of Thoroughbreds are physiologically suited to fast work, one study demonstrated that only 10% win enough prize money to offset the purchase and ongoing expenses.17 Such horses may be viewed as underachievers and may even attract more use of the whip than those that run fast enough to meet their owners’ expectations.

The use of the whip in racing, in general, is being questioned, not least because there is significant risk that when whipping occurs, horses may be too tired to respond to repeated whippings and that this probably amounts to abuse. The effectiveness of the whip in steering a racing horse has been also brought into doubt.18 Furthermore, recent evidence from races of 1200 m and 1250 m has shown that horses, on average, achieved highest speeds in the 600 m to 400 m section (from the finish) when there was no whip use, and increased whip use was most frequent in the final two 200-m sections when horses were fatigued.19 This increased whip use was not associated with significant variation in velocity as a predictor of superior placing at the finish.19 The same data set showed that horses were more likely to be struck in the penultimate 200 m of races if they were being ridden by apprentice jockeys and if they were drawn closer to the rail.20 It is alarming that jockey inexperience is associated with increases in the use of an aversive tool. It is surprising that, regardless of their experience, jockeys were found to be using the whip more if their horses were drawn closer to the rail since there is evidence that those further from the rail have slower race times, so one would expect those horses to need more whipping if, indeed, it was effective in remediating deviations in path caused by having to run on the outside of a bend. Under an ethical framework that considers costs paid by horses against benefits accrued by humans,21 these data make whipping tired horses in the name of sport very difficult to justify.

Hyper-reactivity

While reactivity is selected-for in some high-performance breeds, especially those used for racing, it is unwelcome in the breeding stock of others such as those used for draft purposes. Motivation to respond to pressure may be reduced in the more stoic animals that are commonly labeled sluggish. Perversely the so-called warmbloods may be so tolerant of bit pressures (Fig. 15.11) that they can perform in dressage competitions while subjected to bit pressures that hotbloods cannot ignore.

Figure 15.11 Unfortunately, strong rein contacts are normal in contemporary dressage, perhaps because judges struggle to identify lightness.

(Reproduced with permission of Julie Taylor.)

Hyper-reactivity may arise from inappropriate matching of horses with the work required of them. For example, some horses cannot be used in traffic because they are intolerant of large objects moving in their peripheral vision. Additionally, most traffic-shy horses learn to anticipate aversive stimuli from riders (including rein and leg pressures) when traffic is encountered. This means that instead of habituating to traffic as most horses do, they recognize the rider’s alarm and become especially responsive to traffic-related stimuli, in other words, they become sensitized (see Ch. 4). As discussed with shying, even in the absence of anticipation, inadvertently applying pressure may increase the horses’ motivation to find freedom (Fig. 15.12).2,22

Beyond mismatching horses for work, two general causes of hyper-reactivity are management and schooling. We know that the frequency of unwanted behavior during training is increased by stabling.23 By feeding horses inappropriately and housing them without regard for their need for conspecific company and spontaneous exercise and play, humans increase the likelihood of explosive displays of locomotory behaviors. So, the influence of intensive management should always be considered when a horse presents with training problems, e.g. because shying appears more likely in stabled horses, it is appropriate to consider the effects of post-inhibitory rebound24 and the role of over-feeding high-energy foods as contributors to hyper-reactivity in the wake of confinement. As far as the role of schooling is concerned, it is worth remembering that some riders train their horses to be acutely sensitive to leg pressure. This is appropriate only if the horses are never ridden by novices who may trigger responses inadvertently, e.g. by using their legs to grip and balance.

Failure to consider social needs

Most equestrian pursuits require riders to thwart the horse’s innate need to have constant conspecific company. Inattention to this need or inadequate training of the horse to cope without it can lead to undesirable responses under-saddle. Separation-related distress may cause bolting, while aggression to conspecifics while under-saddle may mean that a horse cannot be ridden in company. Providing insufficient space between horses that are strangers or occasionally even affiliates can cause horses to show aggression to conspecifics while being worked. This is unwelcome since it can cause injuries to both horses and riders. The more obedient a horse is under-saddle the less likely are these responses, so re-training the ‘go’ and ‘stop’ responses is clearly indicated. Due consideration should also be given to the social environment to which the horse is exposed at home and the relevance of this at exercise.

Horse-related causes of unwelcome behavioral responses

If horses continue to perform poorly, despite demonstrable improvements in management or technique, they may have innate or acquired physical anomalies that make them unsuitable for ridden work. This is not meant to suggest that the horses are at fault, since most of these problems can ultimately be attributed to human intervention or omission.

Pain

Applying pressure in sensitive areas is an implicit feature of traditional equitation, which relies on negative reinforcement. While humans routinely inflict discomfort on ridden horses intentionally with rein and leg pressure via bits and spurs, they may also do so unintentionally as a result of poor management or oversight (Table 15.5).

Table 15.5 Selected examples of management factors that contribute to unintentional pain in ridden horses

| Problem area | Example |

|---|---|

| Tack | Saddles can pinch the dorsal lumbar musculature |

| Hoof care | Inappropriate hoof trimming can contribute to bruising of the foot |

| Malnutrition | Overfeeding can increase the risk of rhabdomyolysis |

| Dental anomalies | Sharp spurs and hooks in the molar and premolar teeth may make jaw movement uncomfortable and therefore make the horse less likely to relax its jaw when ridden |

| Cranial discomfort | Trigeminal pain may cause headshaking with frenzied flexion and extension of the poll |

| Musculoskeletal pathologies | Navicular pain may make the horse resistant to work on hard surfaces |

| Exercise surfaces | Certain exercise surfaces may cause unnecessary pain |

Physical inability

Some horses will never be able to excel in some fields (Table 15.6). Their inability should be identified rather than misinterpreted as disobedience or the absence of a ‘will to please’.

Table 15.6 Examples of some of the ways in which some horses are predisposed to poor performance

| Problem area | Example |

|---|---|

| Anomalies in perception | Partial blindness can lead to generalized wariness |

| Conformation | Inadequate height or hindquarter strength can disadvantage a horse intended for jumping or dressage, respectively |

| Physiology | Inherently low thresholds for dehydration and fatigue |

| Gait anomalies | A familial tendency to trot may disadvantage some Standardbreds when asked to pace |

Summary of Key Points

• Equine behavior therapy relies on:

• The reasons for failure of behavioral modification include:

• Riders often experiment with increased force before seeking professional help.

• Persistent application of traditional techniques that have contributed to the emergence of unwelcome behaviors makes the problems themselves more persistent.

• Clinical examinations are essential to rule out non-behavioral causes of undesirable behaviors.

• Consideration of the motivation for undesirable responses in ethological terms helps to identify causal factors.

• In all cases, the key to behavior therapy is sound application of learning theory.

• Clients should be counseled not to expect quick fixes, especially with long-standing problems.

Case study

A 5-year-old riding pony mare had developed a reputation for being impossible to inject. A veterinarian who was persuaded to inject her with a sedative prior to being clipped while she was restrained within a float had his spleen ruptured in the frenzied flight response that ensued when the mare appreciated she was going to be injected.

Injections

Because they had become associated with previous adverse experiences, raised voices and forceful restraint readily conveyed to this pony the message that any veterinary intervention was going to be unpleasant and that the person doing it was to be avoided and feared. Clearly, the use of force and punishment was inappropriate.

This case was approached in two phases. The first was to counter the mare’s fear of injections, and the second focused on her fear of the clippers. The overall goal was to make the experience of both more positive than negative. Using the technique established by Professor Sue McDonnell10 for achieving compliance with any intervention, the mare had to learn three basic lessons. These were that the intervention:

• does not really hurt that much

• could lead to rewards, if tolerated

• could not be stopped with regular flight or fight responses.

The first step was to ensure that the restraint was not causing genuine discomfort or fear, so the mare was handled in a large corral in which she could move without crashing into anything if she withdrew at speed during the procedure. To avoid conveying anxiety to the mare, it was important that personnel working with her were not tense or fearful. Many horses have learned that flinching or retreating on the part of personnel is a portent of their departure, which reinforces agonistic responses.

For injection shyness, it was important to ensure that the injections themselves were as painless as possible by using a small-gauge needle and a quick but gentle injection technique. Successive tolerable approximations of the procedure were patiently repeated. Initially, each improvement in compliance was rewarded with a primary reinforcer (see Shaping in Ch. 4). In this mare’s case, carrots were demonstrably reinforcing, so they were used in the shaping process. Any adverse reactions were not punished. If she moved away, the mare was trained to find that this did nothing to help her avoid the procedure. Personnel stayed with her as much as possible, and calmly waited for her to stop recoiling.

The mare eventually learned to tolerate injections and even appeared to enjoy most normal non-painful veterinary or management procedures.

Clipping

Counter-conditioning was used to train the mare to associate the sound of the clippers with the arrival of her evening meal. The clippers were switched on every evening until the mare and her stable-mates were all responding to the sound of the clippers alone by demonstrating typical restlessness that one finds at feed times, e.g. when buckets are rattled. The next step was to introduce the sight of the clippers in combination with their sound. The mare had all meals presented only after the clippers had been switched on in her stable.

The final steps involved counter-conditioning the fear of the clippers making contact. With the attraction of the food, the mare was encouraged to move toward the clippers. When she did so they were switched off. In this way she was given some operant control of her fear. This was a form of negative reinforcement since the response was made more likely by the removal of the aversive stimulus. She was then target trained with food to move towards the clippers so that they developed associations with rewards.

The seasonality of clipping meant that the clippers would normally have been shelved for many months before being re-used. This was considered counter-productive since spontaneous recovery of the fearful response was a possibility. So, throughout the summer months, the mare continued to have the clippers presented and still has to approach them before they are switched off and she is fed. Now, when she has to be clipped, she can be clipped without any forceful restraint and, indeed, without any sweating.

References

1. Haussler KK, Stover SM, Willits NH. Pathologic changes in the lumbosacral vertebrae and pelvis in Thoroughbred racehorses. Am J Vet Res. 1999;60(2):143–153.

2. McGreevy PD, McLean A. Development and resolution of behavioural problems with the ridden horse. In: D Mills, S. McDonnell (eds). The Domestic Horse. The Evolution, Development and Management of its Behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005, 196–212.

3. Hawson LA, McLean AN, McGreevy PD. Variability of scores in the 2008 Olympics dressage competition and implications for horse training and welfare. J Vet Behav. 2010;5:170–176.

4. Roberts T. Equestrian technique. London: JA Allen, 1992.

5. Rollin BE. Equine welfare and emerging social ethics. Animal Welfare Forum: Equine Welfare. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216(8):1234–1237.

6. McGreevy PD, Warren-Smith A, Guisard Y. The effect of double bridles and jaw-clamping crank nosebands on facial cutaneous and ocular temperature in horses. J Vet Behav. 2012;7:142–148.

7. McGreevy PD. The fine line between pressure and pain – ask the horse. Veterinary Journal. 2010;188:250–251.

8. McGreevy PD, McLean A. Development and resolution of behavioural problems with the ridden horse. In: Mills DS, McDonnell SM. The Domestic Horse: The Origins, Development, and Management of its Behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

9. McGreevy PD, McLean AN. The roles of learning theory and ethology in equitation. J Vet Behav. 2007;2:108–118.

10. McDonnell SM. How to rehabilitate horses with injection shyness (or any procedure non-compliance). Annual Meeting AAEP, San Antonio, Texas, November 26–28, 2000.

11. Waring GH. Horse behavior: the behavioral traits and adaptations of domestic and wild horses including ponies. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes, 1983.

12. Mills DS. Personality and individual differences in the horse, their significance, use and measurement. Equine Vet J Suppl. 1998;27:10–13.

13. Casey R. Recognising the importance of pain in the diagnosis of equine behaviour problems. In: Harris PA, Gomarsall GM, Davidson HPB, Green RE, eds. Proceedings of the BEVA Specialist Days on Behaviour and Nutrition; 1999:25–28.

14. Wilewski KA, Rubin L. Bit seats: a dental procedure for enhancing performance of show horses. Equine Pract. 1999;21(4):16–20.

15. Schonholtz CM. Animals in rodeo – a closer look. Animal Welfare Forum: Equine Welfare. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;216(8):1246–1249.

16. McLean AN, McLean MM. Horse training the McLean way – the science behind the art. Victoria, Australia: Australian Equine Behaviour Centre, 2002.

17. More SJ. A longitudinal study of racing Thoroughbreds: performance during the first years of racing. Aust Vet J. 1999;77:105–112.

18. McGreevy PD, Oddie CF. Holding the whip hand – a note on the distribution of jockeys’ whip-hand preferences in Australian Thoroughbred racing. J Vet Behav. 2011;6(5):287–289.

19. Evans DL, McGreevy PD. An investigation of racing performance and whip use by jockeys in Thoroughbred races. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e15622.

20. McGreevy PD, Ralston L. The distribution of whipping of Australian Thoroughbred racehorses in the penultimate 200 metres of races is influenced by jockeys’ experience. J Vet Behav. 2012;7:186–190.

21. Jones B, McGreevy PD. Ethical equitation: applying a cost-benefit approach. J Vet Behav. 2010;5:196–202.

22. Keeling LJ, Jonare L, Lanneborn L. Investigating horse–human interactions: the effect of a nervous human. Veterinary Journal. 2009;181(1):70–71.

23. Rivera E, Benjamin S, Nielsen B, et al. Behavioral and physiological responses of horses to initial training: the comparison between pastured versus stalled horses. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2002;78(2–4):235–252.

24. Houpt K, Houpt TR, Johnson JL, et al. The effect of exercise deprivation on the behaviour and physiology of straight-stall confined pregnant mares. Anim Welfare. 2001;10(3):257–267.