Chapter 32 Confirming pregnancy and care of the pregnant woman

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

This chapter focuses upon the care and services provided and delivered to women during the antenatal period from the point at which a woman believes she may be pregnant to the onset of labour. During this period, pregnant women experience major physiological and psychological changes facilitating adaptation and preparation for birthing and transition to parenting (Coad & Dunstall 2005, Stables & Rankin 2005). Midwives are key professionals who deliver care to the women and their families. They work in partnership with women to assess women’s individual needs and to plan and implement the most appropriate care.

Confirmation of pregnancy

Many women of childbearing age who are sexually active may suspect that they are pregnant, especially if their menstrual period is delayed and/or other symptoms of pregnancy, such as nausea or vomiting, are experienced. Often, many women say that they ‘just feel different’. Women may choose to confirm their pregnancy either by using a home pregnancy test or by seeking diagnosis through their midwife or general practitioner (GP). Confirmation of pregnancy is established by a detailed history and a clinical examination based on the signs and symptoms of pregnancy, resulting from the physiological alteration in the body’s systems and organs. These include amenorrhoea; breast changes and tenderness; nausea and vomiting; increased frequency of micturition; enlargement of the uterus; and skin changes. These signs and symptoms become obvious to the woman as her pregnancy advances, but as some of these symptoms and signs may be found in other conditions not associated with pregnancy, it is important that the midwife is aware of these conditions, as she may need to refer the woman for further investigations or specialist advice.

Reflective activity 32.1

When you next undertake a ‘booking’ interview, discuss with the woman, and, if appropriate, her partner:

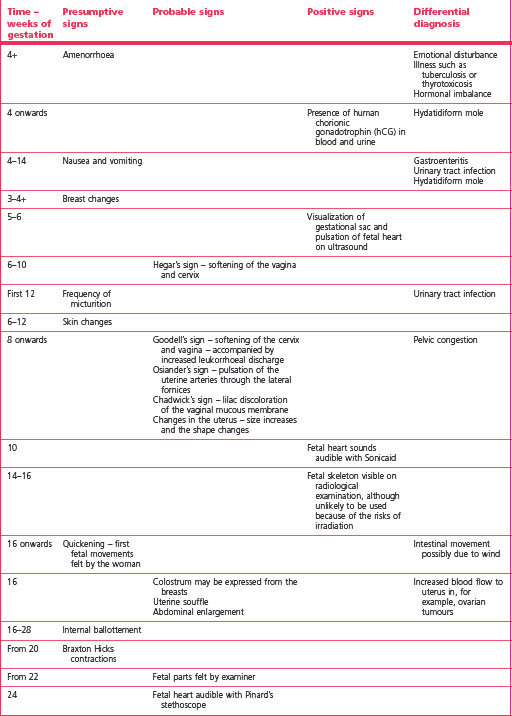

Signs and symptoms of pregnancy may be considered as presumptive, probable and positive, as illustrated in Table 32.1.

First 4 weeks

Amenorrhoea

Following implantation of the fertilized ovum, the endometrium undergoes decidual change and normally menstruation does not occur throughout pregnancy.

Amenorrhoea almost invariably accompanies pregnancy and, in a sexually active woman who has previously menstruated regularly, can be considered to be due to pregnancy unless this is disproved. However, the possibility of secondary amenorrhoea should be considered.

Breast changes

Discomfort, tenderness or tingling and a feeling of fullness of the breasts may be noticed as early as the third or fourth week of pregnancy, as the blood supply to the breasts increases.

Nausea and vomiting

These are common symptoms, with nausea affecting about 70% to 85% of pregnant women and vomiting approximately 50% (Gadsby et al 1993, Lacroix et al 2000, Whitehead et al 1992). Of the women who experience nausea, only a small percentage experience it in the morning but many suffer from it throughout the day. Vomiting, however, is also a feature of a variety of conditions, such as gastroenteritis, urinary tract infection and hydatidiform mole, and these should be ruled out.

Around 8 weeks

Around 12 weeks

Nausea and vomiting

These may decrease, and, for some women, cease altogether. The mean duration of nausea is about 34.6 days and in about 50% of women it lasts until 14 weeks’ gestation (Lacroix et al 2000).

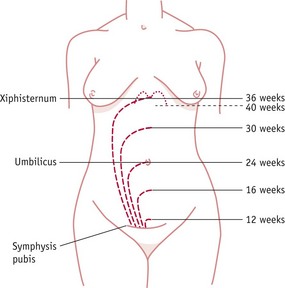

Enlarged uterus

The enlarged uterus is just palpable above the symphysis pubis at about 12 weeks. Other reasons for an enlarged uterus include tumours such as ovarian cysts or fibroids. Ascites may be mistaken for a pregnant uterus.

Skin changes

Pigmentation of the skin occurs and is especially pronounced in brunettes. Areas of increased pigmentation include the nipples and areola; the linea nigra, which is the line of pigmentation from the symphysis pubis to the umbilicus; and, rarely, chloasma, which is sometimes referred to as the ‘mask of pregnancy’ (see website). The nipples become more prominent and Montgomery’s tubercles are visible on the areola.

Around 16 weeks

Colostrum

The breasts may begin to secrete colostrum, which persists throughout pregnancy and for the first few days after delivery until milk is produced. A secondary areola may appear in brunettes.

Quickening

The first fetal movements may be felt by primigravidae at 19+ weeks and by multigravidae at 17+ weeks. The time scale over which fetal movements are first felt by the mother ranges from 15 to 22 weeks in primigravidae and from 14 to 22 weeks in multigravidae (O’Dowd & O’Dowd 1985). Quickening, often described as ‘flutters’, or a feeling of ‘bubbles coming to the surface’ rather than recognizable movements, is an unreliable indicator of gestational age as sometimes these feelings can be attributed to flatulence.

Around 20 weeks

For 90% of women, nausea and vomiting have usually diminished by 22 weeks’ gestation (Lacroix et al 2000). The secondary areola, if not already present, may appear. The fundus of the uterus is normally palpated just below the umbilicus.

Around 24 weeks

The fundus can be felt just above the umbilicus and the fetal parts and movements may be felt on abdominal palpation. The fetal heart sounds may be heard with a fetal stethoscope and at 24 weeks the fetus is considered to be capable of an independent existence.

From 28 to 40 weeks

The fundus continues to rise until 36 weeks, when it reaches the xiphisternum and remains at that level until the fetal head engages. Braxton Hicks contractions, painless irregular uterine contractions, may be palpated from about 16 weeks and these persist until the end of pregnancy.

When engagement occurs from 36 weeks, the fundus descends slightly, causing, together with the increased flexion of the fetus, a relief of pressure which is experienced by the woman in the form of ‘lightening’. This may not occur in multigravidae as the head often does not engage until labour is established. This lightening allows the woman to breathe with more comfort; however, the descent of the head may cause pressure on the bladder, resulting in increased frequency of micturition.

Signs of pregnancy found by vaginal examination

It is now uncommon to undertake a vaginal examination in early pregnancy; however, if performed, the following signs of pregnancy may be observed:

Positive signs of pregnancy

Although there are many physical changes experienced by the woman which might suggest pregnancy, there are a number of positive signs that will confirm pregnancy:

Laboratory diagnosis of pregnancy

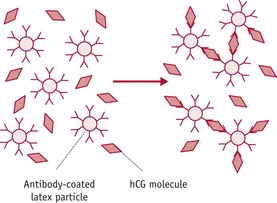

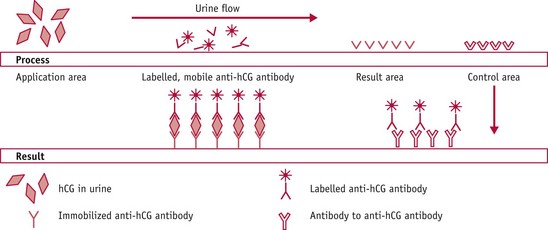

Chorionic tissue, which later forms the placenta, starts producing the hormone human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), which is excreted in the urine. This hormone is usually detected in the urine from the time of the first missed period. Immunological tests depend on the detection of hCG in the urine. Pregnancy tests fall into three categories with varying sensitivities to hCG:

Figure 32.2 The principle of the wick test as used in dipstick and cassette devices.

(From Wheeler 1999.)

Up to 40 types of laboratory test kit are available in the UK (Wheeler 1999). These have a wide range of different sensitivities, from 20 to 1000 IU/L of hCG.

Home pregnancy tests have a more consistent range of sensitivity, from 25 to 50 IU/L, take from 1 minute to obtain a result, appear easy to use and manufacturers claim a 99% accuracy rate. However, an American meta-analysis of the efficiency, sensitivity and specificity of tests highlighted that the diagnostic efficiency of home pregnancy tests is affected by the characteristics of the users (Bastian et al 1998). False negative results arose from testing before the recommended number of days from the last menstrual period, or from a failure to read or follow the instructions. Therefore, a negative result in a woman who does not menstruate within a week should be treated with caution. The test should be repeated and laboratory confirmation sought if doubt of pregnancy exists.

The advantages of using home pregnancy tests are that they can confirm pregnancy in the privacy of the home. This enables a woman to be the first to have the information and it provides a quick result at an early point in the pregnancy. However, given the varying sensitivities of home and laboratory tests, it is possible that a woman may receive a positive diagnosis of pregnancy using a home pregnancy test and a negative result from a laboratory test. This may cause anxiety and confusion. If this happens, the midwife needs to ask the laboratory which test they are using and its sensitivity. A repeat test may then be requested, to confirm pregnancy. It is also possible that spontaneous miscarriage could have occurred between the two tests.

Following confirmation of pregnancy, women are encouraged to contact their midwife or doctor to commence their antenatal care.

Pseudocyesis

This is a phantom or false pregnancy and may occur in women with an intense desire to become pregnant. Amenorrhoea will be present. The woman will complain of all the subjective symptoms of pregnancy, usually in a bizarre order; the abdomen may be distended and the breasts may secrete a cloudy liquid. However, she is not pregnant. The signs on which a certain diagnosis of pregnancy can be made – namely, palpation of the fetus or hearing the fetal heart – are not present. Referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist may be required.

Antenatal care

Over the past two centuries, antenatal services have seen major developments in terms of their provision and delivery. Contemporary antenatal services have quality at their heart, with patient safety, patient experience and effectiveness of care as their central tenets (DH 2008). All women seek a healthy outcome to their pregnancy; they want high-quality, personalized care coupled with greater information so that they can make informed choice about the place and nature of their care and are more in control of the care that they receive (Redshaw et al 2007).

The UK maternity services aim to provide a world-class service to women and their families, with the overall vision for the services to be flexible and individualized. Services should be designed to fit around the needs of the woman, baby and family circumstances, with due consideration being given to factors that may render some women and their families to become vulnerable and disadvantaged. Pregnancy is a normal physiological process for the majority of women. Women and their families need support to have as normal a pregnancy and birth as possible, with medical intervention being offered only if it is of benefit. However, in some circumstances, both midwifery and obstetric care are indicated and care should be based on providing good clinical and psychological outcomes for the woman and her baby (DH 2007a, DH & DfES 2004, NICE 2008).

Aims of antenatal care

The overall purpose of antenatal care is to work with women to improve and maintain maternal and fetal health by monitoring the progress of pregnancy to confirm normality and detect any deviation early so that corrective care can be provided. The aims of antenatal care are to:

Care during pregnancy

It is important that women seek professional healthcare early in pregnancy – that is, within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy (HM Treasury 2007, Lewis 2007, NICE 2008) – so that they can obtain and use evidence-based information to plan their pregnancy and to benefit from antenatal screening and health promotion activities (DH 2007a, DH & DfES 2004, NICE 2008). With early information about the available models of antenatal care, women, in partnership with healthcare professionals, can make decisions about the most appropriate pathway of their care best suited to their personal, social and obstetric circumstances.

Where women seek care at a later stage in pregnancy, they will have reduced access to antenatal care. It is likely that the woman will have reduced options in terms of antenatal screening tests. Some investigations, such as serum screening for Down syndrome (see Ch. 26), are accurate only if carried out at specific times, in this case between 15 and 18 weeks. Early detection of these conditions enables further investigations, such as ultrasound scan or amniocentesis, to be carried out at the optimum time.

Early access to antenatal care enables healthcare professionals to obtain baseline measures, facilitating accurate monitoring of the effect of physiological changes on vital systems and organs of the body and early detection of any complications. For example, the recording of the blood pressure in the first trimester of pregnancy provides a baseline against which the physiological changes in the blood pressure can be assessed. In some cases, complications may have already arisen by the time the woman seeks antenatal care.

The woman should be able to choose whether her first contact in pregnancy is with a midwife or her GP (DH 2007a). That said, antenatal services vary; in many parts of the UK, the first point of contact for maternity services is the woman’s GP (CHAI 2008, Redshaw et al 2007), but services are working towards the midwife being the first point of contact in the community setting.

To achieve the principles of antenatal care, pregnant women require evidence-based information. Evidence suggests that women desire accurate and timely information about pregnancy and childbirth so that they can develop their knowledge and understanding of pregnancy, childbirth and related issues, enabling them to make informed decisions about the care they want and prefer (Bharj 2007, Kirkham & Stapleton 2001, Mander 2001, Singh & Newburn 2000). Women need information which is based upon current evidence that is clearly understood and in a format they can easily access. When offering information, healthcare professionals must take into account the requirements of women who have physical and sensory learning disabilities and women whose competence in speaking and reading English is low, exploring appropriate ways of exchanging meaningful information.

Midwives are key healthcare professionals who work with women to support them to make informed choices regarding preferred arrangements for antenatal care, place of birth and postnatal care. Midwives should be friendly, kind, caring, approachable, non-judgemental, have time for women, be respectful, good communicators, providing support and companionship (Bharj & Chesney 2009, Nicholls & Webb 2006). These attributes are essential for the development of the woman–midwife relationship. Many worldwide studies highlight that all women perceive the woman–midwife relationship to be central to their pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal experiences (Anderson 2000, Bharj 2007, Davies 2000, Edwards 2005, Kirkham 2000, Lundgren & Berg 2007, Walsh 1999). Midwives therefore play an essential role in the life of women during their most significant period and have the power to either augment or mar women’s experiences of pregnancy and childbirth.

Reflective activity 32.2

Reflect upon the discussions you have had, or have observed, with women during the initial visit. Do you think that you provided sufficient information for the woman to make informed decisions about patterns of antenatal care, home birth and who she would wish to see during the antenatal period?

Outline of present pattern of maternity services in England

There are a wide range of models of care operating across the UK because of the geographical and demographic variations (Green et al 1998, Wraight et al 1993). The organization of maternity services varies throughout the UK. The maternity and obstetric units are formed as a part of larger district or regional general hospitals and the maternity and midwifery services are normally provided through such units and are integrated within the community and hospital. Midwifery units are designed and staffed according to the birth rates, therefore, the sizes of the units are variable dependent on the birth rates. Some NHS hospitals provide tertiary maternity and neonatal services for part of the regions. Generally, midwifery staff are employed by an acute maternity unit and may work either in the community or in the hospital, or, in some models of care, in both.

Birth settings

There are four different birth settings: ‘consultant-led obstetric units’ (CLU), ‘midwifery-led units’ (MLU), ‘home’, and ‘free-standing maternity units’ (FMU) (Hall 2003) (for choices of place of birth, see Ch. 34). CLUs are usually attached to the district or regional units and deliver care both for women who have complex healthcare needs and for those with no complications of pregnancy, labour and birth. CLUs are staffed by midwives and obstetricians. Women are normally referred to an obstetrician who becomes the lead professional for the duration of their childbirth continuum. Women with complex healthcare needs may access all their care in the antenatal, intranatal and postnatal period within these settings.

Some women with less complex healthcare needs may access some of their care in the hospital setting and some in the community setting. Some women who have had uncomplicated pregnancies and who are at low risk of developing complications during labour and/or birth choose to labour and birth within a CLU with a midwife as lead professional rather than an obstetrician. A full range of obstetric facilities (such as anaesthesia, surgery, blood transfusion and neonatal intensive care) are readily available in CLUs.

MLUs, sometimes known as ‘low-risk maternity units’ (Hall 2003), are often located close to, but separate from, CLUs. These units normally aim to provide care to women with uncomplicated pregnancies; the women, however, have to meet the criteria for the unit throughout pregnancy, labour and birth. MLUs are staffed predominantly by midwives, although they may be jointly run by midwives and GPs. If a deviation from normal is detected during pregnancy, labour or birth, the woman will be referred to an obstetrician, or, if appropriate, a GP, and may have to transfer place of care to the CLU. Normally, women access the majority of their antenatal care in the community setting with minimal care in the hospital setting.

Women may choose to have their babies at home instead of a hospital setting (see Ch. 34). Each of the midwifery units in the UK has its own arrangements for providing a home birth service and its own guidelines and attitudes towards these. The provision of this service depends on local resources, local practices and policies, and the beliefs, skills and commitment of individual practitioners providing the service. Women who choose to have a home birth are normally given care in the community by the lead professional who may be either a midwife or GP. In circumstances where the maternity needs of the woman cannot be managed in the home setting, then she and/or her baby is transferred to the nearest CLU.

The purpose of the FMUs is to offer a ‘home-like’ environment within an institutional setting. The philosophy and the kind of care offered by an FMU are very similar to those of the MLUs and the main difference is that the FMU is geographically situated away from the CLU. Generally, women who access care at these settings have to fit in with the guidelines and protocols of these units and are normally those women who are less likely to require interventions. Should an intervention be required for a woman, a decision will need to be made about transferring to the CLU.

To meet the maternity needs of the local populations, two things have happened concomitantly in some areas of England. The move to centralize maternity services has seen a number of mergers and, at the same time, there have appeared a small number of new community units or birth centres to provide a limited service for women who would otherwise have to travel long distances to have their babies in large obstetric units (for example, see Kirkham 2003).

Team midwifery

Maternity services for women in the NHS are normally provided by a multiprofessional team comprising community midwives, GPs, and hospital-based midwives or doctors in the antenatal period and usually by hospital-based midwives or doctors in the intrapartum period (unless they have a home birth) and by midwives and the GPs in the postnatal period. However, many maternity units are maximizing a multiprofessional approach to service provision and delivery and are collaborating with other relevant healthcare professionals to develop a multi-agency integrated care pathway, involving shared care, for example, with the drug and alcohol treatment services. This collaborative approach to care has improved the experience and outcome for women and babies.

A variety of approaches to team midwifery are emerging; they strive to provide choice and continuity and these include team midwifery normally based in the community, one-to-one midwifery practice care for women (Green et al 1998, Page et al 2000), that is, a complete episode of care from the booking interview to transfer to the health visitor following birth, including intrapartum care. Other approaches include caseload midwifery, or, as it is sometimes referred to, midwifery group practice. This comprises a small number of midwives organized into a team who are responsible for the delivery of full range of maternity care (SNMAC 1998). The midwives in the team are each responsible for approximately 30–40 women in a year.

While many parts of the UK have some sort of team arrangement for providing maternity services, these teams may vary from two or three midwives to over 30. There is no agreed definition of teams (RCM 2000, SNMAC 1998, Wraight et al 1993) though teams are responsible for providing care in the hospital setting, community settings, or both. There are four possible options of care:

The type of care offered is dependent on the health needs of the woman and local practices and protocols. Where women do not have any perceived complications in the antenatal and intrapartum period, they may choose to have all their care in the community setting or a mixture of both community and hospital. However, those women who have or develop complications in pregnancy or the intrapartum period access services in the hospital setting.

Increasingly there are developments where the NHS is collaborating with the local authority to offer maternity services from children’s centres. In addition to this, some midwives are seconded to specialist outreach services, particularly Sure Start (integrated health, education and welfare support services for children under 4 and their families) and smoking cessation services.

In many areas, antenatal day assessment units have been developed to provide outpatient care. In circumstances where complications arise, such as moderate pregnancy-induced hypertension, the pregnant women can be referred to the antenatal assessment unit, where her and her baby’s health may be assessed and monitored. Referral to such units can be made by the women themselves, by midwives or by other healthcare professionals.

Domiciliary in and out scheme (DOMINO scheme)

A domiciliary in and out scheme (DOMINO scheme) is offered in some areas for women who wish for community-based care (Wardle et al 1997). Within this model, antenatal care is delivered by a community midwife as it would be for a home birth. The community midwife provides care at home during labour, and continues care when the woman is transferred into hospital for birth. Following birth, the woman and her baby, when healthy, are transferred home with postnatal care provided by the community midwife.

Independent midwifery services

Independent midwives are currently in the minority, delivering around 500 births per year in the UK. The midwives are self-employed and offer themselves for service to individual women. Their education and governance is the same as that of any other practising midwife within the UK and within the same regulatory body and with Supervision of Midwives. The main differences are that they set up their protocols for practice, using evidence-based practice, and usually offer a home birth service, meeting women’s individual requirements; and usually practise in small groups of two or three or in some cases single-handedly. Some midwives have honorary contracts with their local hospitals and offer a DOMINO service, though where midwives are unable to secure contracts, when a woman booked with them requires medical services, the independent midwife can only accompany her to hospital as a friend or doula.

Place of birth

During pregnancy, women need unbiased information to consider where they wish to give birth. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 34. The most common place of birth continues to remain the hospital setting and the rate of home births has not changed significantly over the past few decades, despite calls for increasing women’s choice in the place of birth (DH 2007a). Although the rate of home birth remains low, there are marked geographical variations. This appears to depend on midwives and doctors supporting the idea of healthy women having their babies at home. Where this was the case, the numbers of women having home births increased (Sandall et al 2001).

Pattern of care

Historically, irrespective of their personal needs, individual risk status or parity, all pregnant women were encouraged to routinely attend an antenatal clinic every 4 weeks up to 28 weeks’ gestation, then 2-weekly up to 36 weeks, and then weekly thereafter. Evidence in the 1980s suggested that healthy women were at no greater risk of maternal or perinatal mortality if they attended fewer antenatal visits than the historical pattern of care (Hall et al 1985) and in 1982 the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommended that maternity care providers should reduce the number of antenatal visits for women who do not have any complications of pregnancy from the historical pattern of 14–16 visits for all women to five to seven visits for multiparous women and eight or nine visits for primiparous women (RCOG 1982). This recommendation was not widely implemented until it was reiterated in the ‘Changing childbirth’ report (DH 1993), where it was suggested that many existing maternity care practices, such as the frequency and timing of antenatal care, had continued as a result of tradition and ritual rather than as a result of evidence of effectiveness. More recently, the NICE guidance (2008) recommended that for nulliparous women with uncomplicated pregnancies, ten antenatal appointments ‘should be adequate’, and that for parous women with uncomplicated pregnancies, seven antenatal appointments ‘should be adequate’. However, 25% of women have reported receiving fewer than the recommended number of antenatal visits (CHAI 2008). Whilst it is acknowledged that a reduction in the frequency of antenatal appointments does not result in an increase in adverse biological maternal and perinatal outcomes (Villar et al 2001), it is not clear whether a reduction in the frequency of antenatal visits affects women’s satisfaction with antenatal care and the social support that they may require. Nevertheless, it is essential that the number of antenatal visits should be tailored to meet women’s individualized health needs instead of attending antenatal appointments in a ritualistic pattern.

Throughout the childbearing period, all women should be provided with the opportunity to discuss issues and to ask questions (NICE 2008). To enable women to make informed choices about their care, midwives need to work in partnership with women and their families to develop and maintain relationships based upon effective communication skills, empathy and trust (Berry 2007). To communicate effectively and discuss matters fully with women, antenatal appointments need to be structured in such a way as to ensure the woman has sufficient time to make informed decisions (NICE 2008) and midwives need to develop the knowledge required to ensure they are able to offer up-to-date, consistent, evidence-based information and clear explanations, using terminology that women and their families are able to understand. Adjustments may need to be made to ensure that women with additional communication needs are able to access information in a format they are able to understand. This may include using interpreters, online resources or DVDs as well as leaflets and books to support discussions.

The first antenatal visit

The first antenatal visit and taking of the woman’s history may occur in the woman’s home, a health centre or GP surgery, or at the first visit to the hospital antenatal clinic. If a combined approach is taken, this will reduce the visits that the woman may have to make.

Women may feel apprehensive at their first visit, especially if they have not previously met the midwives or medical staff. Good communication skills and a non-judgemental attitude are important to enable women to feel at ease in discussing very intimate personal details. A warm, friendly greeting and a pleasant, comfortable environment can also help to put women at their ease. Whilst many women may be rather apprehensive at the first visit, young teenagers, women who are less proficient in speaking English and those who are unhappy about their pregnancy may feel especially vulnerable. Interpreters are required for women who have limited fluency in speaking English and, where possible, such women should be given information in formats that enable them to access and understand the information easily – for example, written information in their own language, audiovisual tapes or in braille. In many large cities where the number of teenage pregnancies is high, special ‘teenagers’ clinics’ or clubs may be provided to meet their particular needs.

Whatever the background of the woman, or her reactions to her pregnancy, building a positive relationship with her is one of the midwife’s most important aims during this first antenatal visit. This provides a foundation upon which the trust between a midwife and a woman will be built during the rest of the pregnancy. The woman needs open communication with a midwife who is well informed and committed to supporting her as an individual, encouraging the development of mutual respect, trust and partnership (Nicholls & Webb 2006, Redshaw et al 2007). There is growing evidence of women’s views of the maternity services that consistently highlights the importance of the quality of the women’s relationship with their midwife and the importance of this relationship in their satisfaction levels (CHAI 2008, Redshaw et al 2007).

The importance at the beginning of the interview is for the woman to establish confidence in the midwife, and so the purpose and process of the interview and issues such as confidentiality must be addressed initially. The woman needs to understand the midwife’s professional responsibilities, in terms of information which may be shared, and which may need to be discussed with other members of the team. Similarly, the midwife needs to ensure that a woman’s request that information is kept confidential is respected.

History taking

When the history is taken at home or in a community clinic, the woman is likely to be more at ease. If the interview takes place in the hospital, the midwife should prepare the interview room to be as pleasant and non-clinical as possible in order to facilitate communication and the development of a relationship of mutual trust. The midwife must also provide privacy and sufficient time for the interview, and make this clear to the woman.

During early pregnancy the woman may be experiencing nausea and fatigue and will appreciate not having to travel to attend a busy clinic amongst strangers. Any problems can usually be discussed in private and the midwife can give information and offer advice as appropriate. When other members of the family are present during this initial assessment, this gives the midwife the opportunity to meet them, but she should also be sensitive that there may be information that the woman considers private or confidential and would prefer not to discuss in their presence. Some time alone spent between the midwife and woman is essential and this should be facilitated.

The interview should be a two-way process of interaction between the woman and midwife. It involves assessment of the woman’s social, psychological, emotional and physical condition as well as obtaining information about the present and previous pregnancies, and the medical and family history. Care can then be planned in conjunction with the woman to meet her specific needs and wishes.

An antenatal booking interview should comprise more than merely recording an obstetric history; it should be about communicating information and promoting a relationship between the woman and the midwife (Methven 1982a, 1982b). Factors conducive to a more relaxed atmosphere and which promote communication should be considered, for example, the environment of the setting where the history is going to be taken, arrangements of the furniture in the room, body language and interpersonal skills. A few minutes spent by the midwife in introducing herself and talking informally enable the woman to settle down and relax before personal issues are discussed. A skilled midwife can elicit most of the information required from the woman in a pleasant conversational manner without the woman realizing that she is being closely questioned. Open rather than closed questions should be employed because these encourage free responses and promote two-way interaction between the woman and midwife. During the interview the midwife should be sensitive to the woman’s attitude to her pregnancy and, if possible, to that of her partner. Unusually adverse attitudes and body language should be noted and counselling and support given as required.

Personal details

The woman’s full name, marital status, address, telephone number, age, date of birth, race, religion and occupation (and that of her partner) are accurately recorded. Information regarding the woman’s marital status is elicited to determine if the woman is in a stable relationship or if the woman is alone and may need additional support from the midwife and other agencies.

The woman’s ethnicity is ascertained because some medical and obstetric conditions are more likely to occur in certain ethnic groups and appropriate diagnostic tests are required. However, asking about ethnicity is complex (Dyson 2005) and midwives need to develop competence in accomplishing this sensitively. The religion of the woman is recorded because of the special requirements and rituals which may be practised and affect the mother and her baby. Occupation gives an indication of socioeconomic status. Women in socioeconomic groups IV and V (see website) may experience social and economic inequalities. These wider determinants of health coupled with poverty are most likely to adversely affect their or their fetus’s/baby’s health and clinical outcomes (Lewis 2007, Palmer et al 2008). The midwife needs to work with other agencies to provide the woman and her family with appropriate support to promote and improve her health.

Present pregnancy

The date of the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP) is ascertained, care being taken to check that this was the last normal menstrual period. Some women have a slight blood loss when the fertilized ovum embeds into the decidual lining of the uterus and many mistake this for the last period. Pregnancy has been assumed to last 280 days, and to overcome the irregularity of the calendar a working rule of thumb was devised by Naegele. By counting forwards 9 months and adding 7 days from the first day of the last normal menstrual period, it is possible to arrive at an estimated date of delivery (EDD); alternatively, count back 3 months and add 7 days. This method of calculating the EDD is known as Naegele’s rule. However, as February is a short month and the remaining months have 30 or 31 days, from 280 to 283 days may be added to the date of the LMP. Rosser (2000) states that it is unclear whether the length of pregnancy is affected by social, ethnic or obstetric factors. It is important to explain that it is quite normal for the actual day of delivery to be up to 2 weeks before or after the EDD.

Details of the woman’s menstrual history should be sought: the age at which menstruation began; the duration of the periods; and the number of days in the cycle. Conception occurs shortly after ovulation. With a regular cycle of about 28 days, the standard calculation is reasonably accurate to within a few days, provided that the woman knows the date of her last normal menstrual period.

In a 35-day cycle, however, ovulation would occur 21 days after the period; in a 21-day cycle, only 7 days after. Adjustments may be made, therefore, when the woman has a regular long or short cycle. If the cycle is long (for example, 33 days), the days in excess of 28 are added when calculating the EDD (Table 32.2). With a regular short cycle, such as 23 days, the number of days less than 28 is subtracted from the EDD.

Table 32.2 Calculation of the EDD

| Cycle 28 days | Cycle 33 days | Cycle 23 days |

|---|---|---|

| LMP: 12 Aug 2010 | LMP: 12 Aug 2010 | LMP: 12 Aug 2010 |

| +7 days +9 months | +7 days +5 days +9 months | +7 days −5 days +9 months |

| EDD: 19 May 2011 | EDD: 24 May 2011 | EDD: 14 May 2011 |

The calculation is difficult if the woman does not know the date of her last menstrual period, cycles are irregular, or a normal cycle has not resumed since taking the oral contraceptive pill or following a previous birth. If the woman has a good idea of when conception occurred, the EDD can be calculated by adding 38 weeks to this date, or subtracting 7 days from 9 months.

Women should be asked to note the date when fetal movements are first felt. Primigravidae normally become aware of fetal movements between 18 and 20 weeks, whereas multigravidae recognize the sensation a little earlier, between 16 and 18 weeks. This may be used to confirm the expected date of delivery, although with the widespread use of ultrasound in the UK, the gestational age is usually established during ultrasound examination (see Ch. 33). A dating ultrasound offered to a woman between 10 and 13 weeks of pregnancy normally measures the crown–rump length (CRL) and for pregnancies beyond 14 weeks the fetal gestational age is determined by the measurement of the head circumference or biparietal diameter (BPD) (NICE 2008).

Although the use of ultrasound to estimate gestational age is very useful, some women may find it distressing if there are discrepancies between the date estimated by Naegele’s rule and that given following ultrasound examination, especially those who are certain of the date of conception or who have a regular cycle and are certain of the date of the first day of their last menstrual period. In most cases it would be inappropriate to alter the expected date of delivery without the mother’s agreement, especially when there is less than 10–14 days’ discrepancy with the previously given date (Proud 1997).

Other pregnancy symptoms such as breast changes, nausea and vomiting, and increased frequency of micturition are noted. Nausea and vomiting may range from occasional slight nausea to frequent severe vomiting with ketosis, when immediate medical treatment is necessary (see Ch. 53). Any history of bleeding per vaginam since the last normal menstrual period is recorded and the woman is requested to seek medical attention immediately should further bleeding occur (see Ch. 54).

In the first trimester of pregnancy a woman is quite likely to feel tired, perhaps nauseated and generally rather off-colour. A caring, approachable midwife who provides support, encourages the woman to express any worries and ask questions, and gives clear information, can be a great help to the woman at this time.

Previous pregnancies

It is necessary to ask about all previous pregnancies, including miscarriages or terminations of pregnancy. If the woman has had a miscarriage, she is asked at what stage in pregnancy it occurred, whether she knows of any possible cause, if she was transferred to hospital, and, if so, whether she needed either an operation to remove retained products of conception, or a blood transfusion, or both.

Similar questions are asked about terminations of pregnancy, including the reason for termination and how it was performed. Some women may not wish this information to be recorded in handheld notes and their autonomy should be respected; however, the information should be recorded within hospital notes, and the reasons for this discussed with the woman.

Details of all pregnancies, labours and puerperia are essential:

All pregnancies are dealt with in chronological order. If the history reveals any obstetric or paediatric complications and previous notes are not accessible, the information should be sought from the hospital where care was delivered.

This is a useful part of the interview, as this may be the first opportunity that the woman has had for reviewing and reflecting on her previous childbirth experiences, and this provides a forum for clarifying management of problems both previously and in the future.

Medical and surgical history

This includes enquiry about any illness, operation or accident which could complicate pregnancy. It is necessary to ask by name about rheumatic fever; chorea; cardiac, respiratory and renal diseases; thyrotoxicosis; diabetes; hypertension; thromboembolic disorders; tuberculosis; epilepsy; and mental illness.

A history of mental illness, especially postnatal depression or puerperal psychosis, is of significance because such conditions may recur in a subsequent pregnancy. The woman is asked about infectious diseases of childhood and whether she has had rubella or been vaccinated against the disease. A blood test will confirm whether or not she is immune, and if non-immune, she is advised to avoid contact with the disease, as rubella virus, if contracted in pregnancy, can cross the placenta and cause fetal abnormality.

Operations on the uterus or the pelvic floor are significant. Following caesarean section or myomectomy, there may be a weakened uterine scar, especially if the wound was infected, and there is a slight risk that it could rupture during a subsequent pregnancy or labour. Women of childbearing age sometimes have to undergo extensive pelvic floor repair operations. If a woman has had a successful operation for the relief of stress incontinence, both the woman and the obstetrician will be concerned about the mode of delivery; sometimes, another vaginal delivery is considered inadvisable and caesarean section is planned.

Relevant accidents include those involving the spine and pelvis, particularly if a fracture has occurred and deformity resulted. Deformity of the spine or pelvis following poliomyelitis or congenital dislocation of the hip would cause similar concern, since in all these instances the bony pelvis may be asymmetrical and accordingly have a smaller capacity. Enquiry may be made about back pain or symphysis pubis dysfunction and appropriate support and advice given, and referral made if appropriate.

Details of any blood transfusions are important, including the reason and any adverse reactions.

Drugs and medications

It is important to ask the woman whether she is taking any drugs, because many drugs which are quite safe for the woman may have a teratogenic effect on the fetus. The woman should be informed about the risk of taking over-the-counter drugs without medical advice (NICE 2008).

Drug dependency in women of childbearing age is an increasing problem (Siney 1999) and it is important that the midwife ascertains whether the woman has previously taken or is currently taking prescribed drugs and/or drugs for ‘social or recreational’ use. The misused substances are likely to have a detrimental effect on the health of the woman and her fetus/baby; however, this is dependent on the type, dose and the route of the drug used. Women with drug dependency are at an increased risk of developing medical and obstetrical problems than are women who do not misuse drugs, and their babies are at an increased risk of neonatal complications (DH 1998, Hepburn 1993).

Women who misuse drugs may have a multitude of social, emotional, financial and sexual health problems that necessitate multi-agency involvement to try to minimize harm to themselves, their children and families. It is essential that the approach and attitude of the midwife is caring, non-judgemental and constructively helpful when discussing health needs and the support that can be offered to the woman; otherwise the woman may reject the help that the health and other specialist services can offer.

Smoking in pregnancy

Smoking during pregnancy is a most significant contributing factor for poor health, poor clinical outcomes and health inequalities, increasing, for example, the risk of miscarriage, placental abruption, placenta praevia, preterm birth, perinatal death, sudden unexpected death in infancy, and congenital abnormalities such as development of cleft lip and cleft palate in babies (Ananth et al 1999, Castles et al 1999, DiFranza & Lew 1995, Shah & Bracken 2000, Wyszynski et al 1997). Therefore, reducing smoking in pregnant women is an area of priority for all (DH & DfES 2004). Midwives are ideally placed to give health promotion advice to the woman and her partner on the detrimental effects of smoking on the woman, fetus and newborn baby. The initial interview and antenatal visits are ideal times to discuss whether the woman smokes, the implications of this, and whether she would like to give up smoking (NICE 2008).

Women should be encouraged to either stop or reduce smoking during pregnancy. They should be provided with unbiased and evidence-based information, aiming to encourage them to stop smoking, rather than cause fear or stress. Discussion with women’s partners and enlisting their support in reducing smoking may also be beneficial. Women should be offered details of how to access local NHS Stop Smoking Services and the NHS pregnancy smoking helpline. Smoking cessation programmes in pregnancy – such as providing information on the effects of smoking, advantages of stopping, and strategies to stop, particularly with individual counselling – have shown a varied benefit in stopping smoking, increasing mean birthweight and reducing prematurity (Lumley et al 2000).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence is in the process of developing guidance on public health intervention aimed at stopping smoking in pregnancy and following childbirth (NICE 2009) that would further assist midwives and other healthcare professionals to access and utilize recommendations for good practice.

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy

Alcohol has detrimental effects on the fetus (Gray & Henderson 2006). Women who consume high levels of alcohol before and during pregnancy and those who are alcohol dependent are more likely to have babies with varying forms of congenital abnormalities, often described as fetal alcohol syndrome (RCOG 2006).

The midwife should use the opportunity to take a history of alcohol use, assess the risk of alcohol dependence, or risk to the fetus from alcohol consumption, and advise and refer appropriately. There is no conclusive evidence regarding what is a safe amount of alcohol to drink during pregnancy and the advice given to the expectant mother should be based upon the current recommendation of NICE (2008). The NICE guidance recommends that women should be advised to avoid alcohol during pregnancy where possible. If they do choose to drink, they should not drink more than 1–2 UK units once or twice a week (1 unit equals half a pint of ordinary-strength lager or beer, or one shot [25 mL] of spirit; one small [125 mL] glass of wine is equal to 1.5 UK units). However, evidence suggests that getting drunk or binge drinking (that is, more than five standard drinks or 7.5 UK units on a single occasion) may be harmful to the baby (NICE 2008).

Diet in pregnancy

It is important to ask about the woman’s diet and nutritional intake. Advice should be tailored to her individual circumstances, taking into account her cultural, faith and socioeconomic background (see Ch. 17). General advice to all women should include the need for a well-balanced diet containing proteins (beans, pulses, lentils, meat and fish), dairy products (milk, cheese, yoghurt), fruit and vegetables, carbohydrates (bread, pasta, rice and potatoes) and fibre (wholegrain flour, wholegrain bread, and fruit and vegetables) (NICE 2008).

Pregnant women should be advised to avoid foods that may place their fetus at risk of Listeria monocytogenes infection, for example, unpasteurized soft cheeses and mould-ripened cheeses. Raw eggs and products containing raw eggs, such as mayonnaise, should be avoided because of the risk of salmonella infection, and undercooked meats and pâtés (which may be a source of Listeria, Escherichia coli and Toxoplasma) should also be avoided. Vegetable and salad foods should be washed prior to eating, and food should be stored at the correct temperature in the refrigerator and on the appropriate shelves to reduce the risk of infections such as listeriosis, E. coli and toxoplasmosis.

As high intakes (more than 10 times the recommended daily allowance) of retinol – the animal form of vitamin A – may be associated with congenital abnormality, the NICE (2008) recommendation is that foods containing vitamin A, such as liver and liver products, should be avoided. Women should be informed about the importance of vitamin D for their and their fetus’s health and encouraged to eat foods such as oily fish, eggs, nuts, meat and foods fortified with vitamin D.

Family history

The woman’s family medical history is important. Familial diseases such as hypertension and diabetes are sometimes discovered during routine antenatal examinations and it is useful to know the woman’s medical background. It is essential to know if any near relative has pulmonary tuberculosis, since the newborn child is very vulnerable to the infection and must be protected. Arrangements are made for the child to receive BCG vaccination before leaving hospital, as well as being segregated from the infected person.

As there is a familial tendency to produce twins, especially dizygotic twins, it is important to ask if there are twins in the family and, if so, whether they are monozygotic (identical) or dizygotic (non-identical) (Ch. 59).

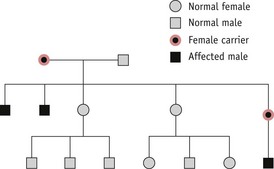

The woman should be asked if there is any history of congenital abnormality in the family (Fig. 32.3) as she and her partner may need referral for genetic counselling (see Ch. 26). A number of diagnostic techniques are available for the diagnosis of congenital conditions in pregnancy and these may be discussed with the couple.

The midwife also carefully observes and enquires about the woman’s reaction to her pregnancy, whether she is happy about it and coping with the initial minor disorders, or appears anxious, tense and unhappy. Guiding the conversation in a skilful, relaxed, unhurried manner and active listening and interpretation of both verbal and non-verbal communications help to elicit the woman’s feelings and concerns. Appropriate support and help can then be offered.

It might appear that history taking is a lengthy procedure; however, in most cases it can be completed within 30–60 minutes, as the majority of clients are healthy young women who have never been seriously ill. This personal history provides a basis on which it is possible to assess the woman’s physical, psychological and emotional health and wellbeing and, to some extent, anticipate the outcome of her pregnancy. An important aspect of this time spent taking the history is that the midwife and woman can meet and develop the relationship which has such a fundamental influence on the woman’s subsequent experience of pregnancy and childbirth.

On completion, the midwife can make an holistic assessment of the woman that influences the discussion around her particular needs and wishes. The midwife gives clear, accurate information about the variety of services available to enable the woman to make informed choices. Only then can a care plan for pregnancy and childbirth be discussed, tailored and agreed to the woman’s individual needs. The woman should be given appropriate literature for her reference after her visit, such as The Pregnancy Book (DH 2007b). A future appointment may be made with the midwife and arrangements are made for any antenatal diagnostic tests to be undertaken.

Domestic abuse

Domestic abuse during pregnancy is of major concern; it affects the physical and mental health and safety of the woman and her fetus. (This is discussed in Chapter 23 but a brief overview is given here as part of the antenatal care routine.) Pregnancy may trigger or exacerbate abuse (Mooney 1993), and this may result in injury, obstetric complications such as miscarriage, placental abruption, antepartum haemorrhage, preterm labour, intrauterine growth restriction and stillbirth (Cokkinides et al 1999, Janssen et al 2003), as well as maternal death (Lewis 2007).

All women should be routinely asked about domestic abuse (BMA 1998, RCM 1999, RCOG 1997).The midwife may be the first point of contact for possible help for a woman who is abused, and the opportunity to initiate questions that may lead to disclosure of abuse can arise at the booking interview or during subsequent antenatal care. Suspicion may arise where the woman is always accompanied by her partner, especially where he constantly answers questions and undermines her. In addition to having an understanding of domestic abuse, including the symptoms and signs of abuse, the midwife needs to be skilled in asking difficult questions (see Ch. 23). All women should be afforded an opportunity to disclose domestic abuse in a safe environment (NICE 2008). Women who experience domestic abuse should be offered information about the choices available to them and the resources to support them. Documentation of abuse should be made with the woman’s consent, but not in handheld records. Medical evidence of abuse may be needed should the case proceed to court. If the woman does not wish her disclosure to be recorded, her autonomy should be respected.

Subsequent antenatal appointments

When the woman and midwife meet for an antenatal appointment, the midwife should greet the woman in a friendly manner, introduce herself, review with the woman the purpose of the appointment, and elicit from the woman any concerns or questions she may have regarding the wellbeing of herself or her fetus, or any other issues.

Antenatal appointments offer women opportunities to discuss and ask questions about their maternity care. They also provide the midwife with an opportunity to offer women information about pregnancy, health promotion and preparation for parenthood. Issues that should be discussed during the antenatal period include infant feeding, management of breastfeeding, care of the baby, vitamin K prophylaxis and newborn screening tests, as well as information about changes that the woman may experience during the postnatal period, including ‘baby blues’ and postnatal depression (NICE 2008).

Details of all discussions between the woman and the maternity care provider, including information discussed, advice offered and plans of care developed, should be agreed and then recorded in the woman’s handheld records, using terminology that the woman is able to understand.

Antenatal appointments may take place in a range of settings, such as the woman’s home, a GP surgery, hospital or children’s centre. Whilst easy access to the setting for women is essential, the midwife must carefully consider the environment in which the antenatal appointment will take place and ensure that women have the opportunity to discuss issues they regard as sensitive in a confidential manner.

Infant feeding

An important area of discussion relates to the woman’s intended method of feeding (see Ch. 43). The woman should be asked about whether in previous pregnancies she commenced breastfeeding and for how long she fed her baby. It is useful to explore whether she had any difficulty last time and/or whether she is aware of the health benefits of breastfeeding for herself and her baby.

The difficulties that women have in breastfeeding can be overcome, and the rate and duration of breastfeeding increased, if the woman has access to evidence-based information and care (see Ch. 43). During the antenatal period, women should have the opportunity to discuss in detail with a midwife how successful breastfeeding can be initiated and maintained. This can include information on analgesia in labour, offering the baby skin-to-skin contact and an early opportunity to suckle following delivery, correct ‘latching’ and positioning, the value of breast milk, baby-led feeding (both day and night), rooming in, and the management of common breastfeeding problems. Midwives need to be aware, when discussing infant feeding, that ‘How do you intend to feed your baby – breast or bottle?’ is a loaded question and the two choices should never be offered as if they are equal. Many women are unaware of the risks associated with artificial feeding and need appropriate and accurate information on which to make an informed choice. For women who have decided to breastfeed, the values of breastfeeding should be reinforced, with positive encouragement of how they can succeed. For women who express a preference for artificial feeding, the reasons for their choice should be explored and information offered to support them to make an informed choice.

Assessments in pregnancy

Maternal weight

Many women are concerned about their weight during pregnancy. Maternal obesity is internationally recognized as being a major cause of maternal mortality and morbidity. In the UK, the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report ‘Why mothers die 2000–2002’ (Lewis 2004) identified that 35% of women who had a pregnancy-related death were obese and that obesity is related to an increase in complications during pregnancy. To identify which women may be at increased risk of complications as a result of obesity, women’s body mass index (BMI) is calculated during the first antenatal appointment (see Box 32.1).

Box 32.1

Calculation of body mass index (BMI)

Example 1 Weight 57 kg (9 stone); height 1.68 m (5′ 6″):

Example 2 Weight 64 kg (10 stone); height 1.57 m (5′ 2″):

Example 3 Weight 76 kg (12 stone); height 1.57 m (5′ 2″)

| BMI score | Category |

|---|---|

| <18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal |

| 25.0–29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0–34.9 | Moderately obese |

| 35.0–39.9 | Obese |

| ≥40 | Severely obese |

Research has identified that risk factors for maternal obesity include health inequalities and socioeconomic deprivation (Heslehurst et al 2007). During the antenatal period it is essential that healthy nutrition and weight management are discussed with pregnant women. Referral to a dietician may be appropriate. Traditionally, women were weighed during each antenatal appointment; however, it is now recommended that repeated maternal weighing, as part of routine antenatal care, should not be undertaken (NICE 2008), although some women may express a preference to be weighed in order to monitor their weight.

Blood pressure and urinalysis

At each antenatal visit, the woman’s blood pressure must be measured and a sample of her urine tested for protein (NICE 2008). These tests are performed to screen for hypertensive disorders and pre-eclampsia (see Ch. 56). The midwife needs to ensure that the results of these screening tests are accurate, as clinical decision making and subsequent care will be informed by the results. Accuracy of the results may be affected by poor technique, or the use of inaccurate or inappropriate equipment.

During antenatal appointments it is usual to measure blood pressure when the woman is sitting upright with her back supported for comfort (see Ch. 56). The woman should rest for 5 minutes prior to the measurement being taken and the midwife should instruct the woman not to talk or eat during the measurement as this may result in an inaccurate higher measurement being recorded (McAlister & Straus 2001). Tight clothing on the arm should be removed; the upper arm supported at heart level and the sphygmomanometer cuff placed at heart level. This is because measurements made with the arm lower than heart level can be 11–12 mmHg higher than those made with the arm supported and the cuff at heart level (Dougherty & Lister 2008). Conversely, if the arm is raised above heart level, the measurement may be falsely low (Beevers et al 2001). Selection of the appropriate sized cuff for the individual woman is important to obtain an accurate reading; the cuff should cover 80% of the circumference of the woman’s upper arm (British Hypertensive Society 2008).

Urine testing for protein can be performed by quickly dipping a reagent strip into a sample of fresh urine. The reagent strips are impregnated with chemicals that react with abnormal substances in the urine and change colour. It is important to inform women that the urine sample should be fresh, as urine that has been stored deteriorates quickly and this can affect the final result (Higgins 2008). To ensure reliable results, it is essential that the reagent strips are stored and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reagent strips usually need to be stored in a dry, dark place, so it is important to make certain that the lid is always replaced between antenatal consultations during a clinic.

During pregnancy it is common for women to report an increase in the amount of vaginal discharge they experience. This discharge may contaminate the urine sample and protein be detected in the urine. If abnormal substances are detected in the urine, culture and sensitivity testing under laboratory conditions may be indicated. For example, if a reagent stick test indicated the presence of nitrites or leucocyte esterase in the urine, culture and sensitivity testing would identify the organism and specify the most appropriate treatment (Dougherty & Lister 2008).

Blood testing

Anaemia

During pregnancy, maternal iron requirements increase due to the requirements of the fetus and placenta and an increase in maternal red cell mass (NICE 2008). Maternal plasma volume increases by up to 50% and the red cell mass increases by up to 20%, resulting in a drop in the haemoglobin concentration in the blood which resembles iron deficiency anaemia. In addition to testing for anaemia in early pregnancy, all women should be offered testing for anaemia at 28 weeks’ gestation (NICE 2008). If anaemia is detected, treatment should be considered, as treatment at this point should allow sufficient time for correction of anaemia before term. Haemoglobin levels outside the normal UK range (10.5 g per 100 mL at 28 weeks) should be investigated (NICE 2008). Irrespective of their rhesus D status, it is recommended that all women are screened for atypical red cell antibodies at 28 weeks’ gestation (NICE 2008) (for further details, see Ch. 33).

Abdominal examination

During the antenatal period, abdominal examination is carried out to determine the symphysis fundal height and, from 36 weeks’ gestation, to determine the presentation of the fetus. To perform an abdominal examination, the midwife needs to be able to observe, palpate and auscultate the woman’s abdomen. Some women may find the nature of this examination intimate and embarrassing. Attention to privacy and the woman’s comfort should reassure the woman. Sensitive communication skills are required to enable the midwife to explain the purpose and procedure of the examination, and as the midwife performs the examination, she should ensure that the woman understands the findings by explaining them using appropriate language and terminology.

Prior to commencing the abdominal examination, the woman should be asked to empty her bladder if she has not done so recently. This is to ensure that the examination does not cause the woman undue discomfort and that a full bladder does not distort either the measurement of symphysis–fundal height or the palpation.

The woman should then lie as flat as she finds comfortable in the supine position. One or two pillows may be required for comfort and she may wish to slightly flex her legs. Some women experience a condition called supine hypotensive syndrome when lying flat on their back, which results from compression of the inferior vena cava and the abdominal aorta by the gravid uterus. Signs that a woman may be suffering from supine hypotensive syndrome include dizziness, pallor, tachycardia, sweating, nausea and hypotension. These unpleasant signs should resolve when the woman is assisted to turn onto her side and blood flow is no longer obstructed. To reduce the risk of this syndrome, the midwife should consider using a wedge, or pillows, under the woman’s right side to alter the centre of gravity and reduce compression of the inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta. Only the woman’s abdomen needs to be exposed, and sheets, or a blanket, can be used to cover legs if required. The midwife should wash and dry her hands prior to commencing the abdominal examination.

During the antenatal period an abdominal examination consists of the following parts:

Observation

The approximate size and shape of the uterus should be observed. The size of the uterus should correspond to the estimated period of gestation calculated by the dating scan or, if this is not available, the date of the last known menstrual period. When making this assessment, take into account the height of the woman.

If the uterus appears to be larger than that indicated by the period of gestation, the main possibilities include:

If the uterus appears to be smaller than that indicated by the period of gestation, the most likely causes are:

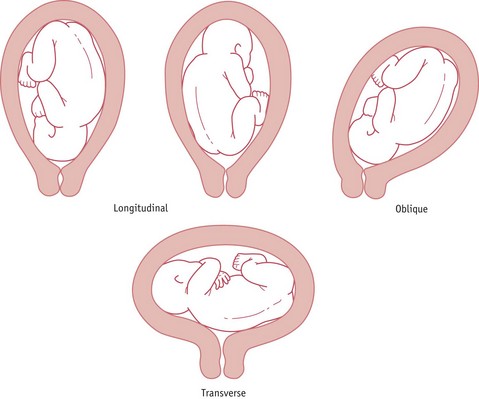

The gravid uterus is usually a longitudinal ovoid in shape. Sometimes, during late pregnancy, the shape of the uterus may be described as ‘unusual’. This may be due to the fetus lying in either an oblique or transverse position.

Whilst observing the size and shape of the uterus, the midwife may note abdominal scars, striae gravidarum (also called stretch marks), or a line of dark pigmentation called the linea nigra which extends from the umbilicus to the pubis. If not already noted in the maternity records, the reason for abdominal scars should be ascertained and this recorded in the maternity records. Striae gravidarum may be seen as red marks if they are new or silver-coloured marks if they date from a previous pregnancy or weight gain. Fetal movements may also be observed.

Palpation

Palpation of the abdomen should be carried out gently and smoothly using both hands, warmed. Whilst it is the pads of the fingers that are used to palpate the fetal parts, it is essential that nails are short to avoid causing the woman discomfort. Undue pressure may cause the woman pain and tightening of the abdominal muscles, as well as stimulation of uterine contractions; both of which will make the palpation more difficult. During the palpation, the midwife should position herself so that she is able to observe the woman’s face for signs of discomfort, such as grimacing. If signs of discomfort are observed, the midwife should ascertain the reason for the discomfort, reassure the woman and amend her technique.

Symphysis pubis–fundal height may be estimated by palpation, or, as recommended by NICE (2008), measured using a tape measure. If the midwife is estimating the fundal height by palpation, the ulnar border of the hand is placed at the uppermost point of the fundus of the uterus and the height compared with the size expected for the period of gestation (see Fig. 32.4).

Whilst NICE currently recommends that the symphysis–fundal height is measured using a tape measure, there are some limitations to this procedure. A review of the current evidence base revealed a wide variation in accuracy and limited predictive value in the use of symphysis–fundal height measurement in detecting both small and large-for-gestational-age babies (NICE 2008). Research has also shown that clinicians are biased in their measurement of fundal height if they have knowledge of the gestational age of the pregnancy or if they use a marked tape measure (Ross 2007).

The Perinatal Institute for Maternal and Child Health (2007) recommends using a non-elastic tape measure with the centimetre markings placed on the underside next to the woman’s abdomen to reduce observer error and bias. The tape measure should be secured at the top of the fundus with one hand and, with the tape measure staying in contact with the skin, the tape measure should be run along the longitudinal axis of the uterus to the top of the symphysis pubis, without correcting to the midline of the woman’s abdomen. The measurement should be recorded in the woman’s antenatal maternity record and plotted on a growth chart. Customized symphysis–fundal height charts, adjusted for maternal weight, height, parity and ethnic group, are available. If the midwife suspects that the fetus is small for gestational age, then referral should be made for ultrasound biometric testing (RCOG 2002).

From 36 weeks’ gestation the abdominal examination should include palpation to determine the position of the fetus. Assessment of fetal presentation by abdominal palpation prior to 36 weeks’ gestation should not be routinely offered to women because it is not always accurate, is of little predictive value and may cause unnecessary discomfort (NICE 2008).

The following terms are used in relation to the position of the fetus in utero:

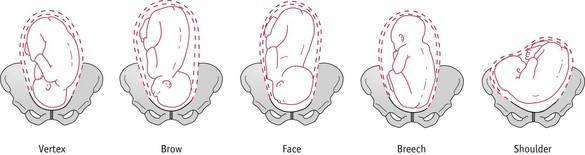

The presentation of the fetus in utero is determined by the part of the fetus lying in the lower pole of the uterus (Fig. 32.5). After 36 weeks’ gestation, the most common presentation is cephalic. Other possible presentations are breech, face, brow and shoulder.

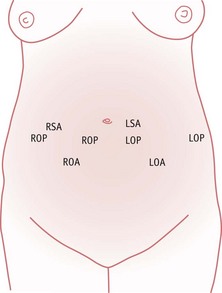

The denominator is a fixed point on the presenting part which is used to indicate the position:

The position of the fetus in utero is the relationship of the denominator to the six areas of the woman’s pelvis (see website). The areas of the woman’s pelvis are:

In a cephalic presentation, the denominator is the occiput, so the position of the fetus is described as:

Anterior positions are more common than posterior positions and help to promote flexion of the fetus. In the anterior position, the fetal back is uppermost and can flex more easily against the woman’s soft abdominal wall than when it lies against the woman’s spinal column as occurs in a posterior position.

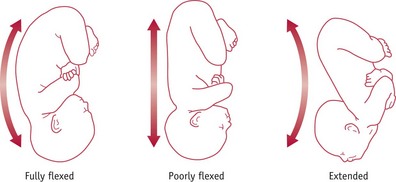

The attitude is the relationship of the fetal head and limbs to its body. The attitude of the fetus may be described as being fully flexed, deflexed, partially extended or completely extended (Fig. 32.6). When fully flexed, the fetal head and spine are flexed, the arms are crossed over the chest, and the legs and thighs are flexed, forming a compact ovoid which fits the uterus comfortably.

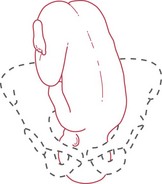

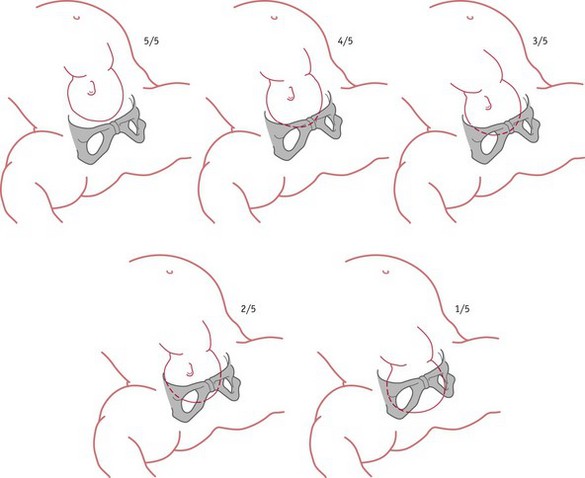

Engagement of the fetal head occurs when the transverse diameter of the fetal skull has passed through the brim of the pelvis (that is, the biparietal diameter measuring 9.5 cm) (Fig. 32.7). Engagement of the fetal head may be measured in fifths. The amount of head palpable above the brim of the pelvis is assessed and described as follows (Fig. 32.8):

The lie is the relationship of the long axis of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus (Fig. 32.9). The lie of the fetus may be longitudinal, oblique or transverse. In the later weeks of pregnancy, the lie should be longitudinal.

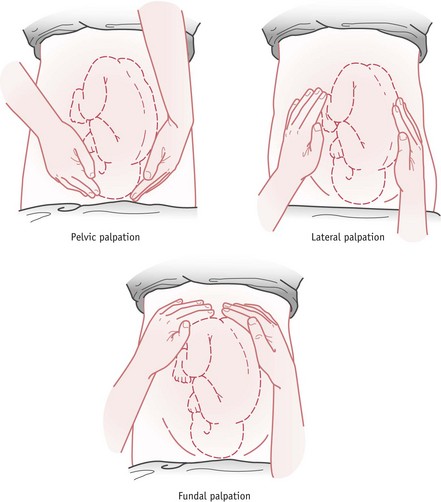

To determine the presentation, position, attitude, engagement and lie of the fetus in utero by abdominal examination, the midwife will use three distinct manoeuvres:

For palpation of the abdomen, see Figure 32.10.

Pelvic palpation

This is the most important manoeuvre in abdominal palpation as it is during the pelvic palpation that the presentation of the fetus is determined. Traditionally, midwives may have performed a fundal palpation, followed by a lateral palpation and then a deep pelvic palpation. However, for some women, palpation of the uterus may cause tightening of the uterine and abdominal muscles, which may make it very difficult to determine fetal presentation, so consideration should be given to performing the pelvic palpation first, when the muscles of the uterus and abdomen are relaxed. In addition to determining the presentation of the fetus, the attitude and degree of engagement of the fetal head may also be identified. To perform a deep pelvic palpation, the midwife stands alongside the woman, facing the woman’s feet. The midwife then places one hand on each side of the uterus near the pelvic brim. The fingertips should then sink gently and smoothly into the pelvis to feel the presentation. The fetal head feels hard and round. If the fetal head is not engaged, it may be possible to ballotte it. This means that if the fetal head is given a gentle tap by an examining finger, the head floats away from the finger and then is felt to return to the examining finger. If the fingertips can sink further into the pelvis, more on one side than the other, this may mean that the head is flexed and the occiput is lying on the side into which the fingers sink more deeply. Occasionally, some midwives or obstetricians may also perform pelvic palpation using a manouevre called ‘Pawlick’s grip’. The thumb and first finger of the hand are spread open and placed just above the symphysis pubis with the thumb and finger tips pointing towards the woman’s face. The thumb and finger then grasp the lower part of the abdomen to determine the presentation and engagement of the presenting part. Some practitioners find this manoeuvre useful if the presenting part is above the pelvic brim; however, it is unlikely that all the information required during a pelvic palpation can be ascertained by use of Pawlick’s grip alone and deep pelvic palpation may need to be carried out in addition to Pawlick’s grip. In order to minimize discomfort for the woman, it may be more prudent to perform deep pelvic palpation first.

Fundal palpation

Fundal palpation is carried out to determine which part of the fetus is lying in the fundus of the uterus. Still turned to face the woman, the midwife uses both hands to gently palpate the fundus. If the fetal presentation is cephalic, then the breech will be felt in the fundus. The breech feels irregular in outline, less hard than the fetal head, and fetal lower limbs may be felt near it. If the presentation of the fetus is breech, then the fetal head will be felt in the fundus. The fetal head feels smooth, round and hard. It is usually ballottable and separated from the trunk by a groove, the fetal neck. It is possible to move the fetal head more freely than the breech, which can only be moved from side to side.

Lateral palpation

Lateral palpation is carried out to determine the position of the fetal back. The midwife turns to face the woman’s face. One hand is placed flat on one side of the woman’s abdomen to steady it whilst the other hand gently palpates down the length of the other side of the maternal abdomen. The process is then reversed, with the hand that was being used to steady the abdomen being used to palpate the length of the abdomen and the hand that was firstly used to palpate the abdomen being used to steady the uterus. The fetal back is felt as a continuous smooth resistant object whereas the fetal limbs are felt as being small irregular objects which may move whilst they are being palpated. If the fetal back cannot be palpated but fetal limbs are felt on both sides of the midline of the uterus, the fetal position is most likely to be occipitoposterior.

Auscultation

This is carried out when women visit the antenatal clinic. The early sounds are heard through ultrasound and from about 16 weeks may be heard via the electronic monitor (see Ch. 36).

Auscultation can be done with the Pinard monaural fetal stethoscope or the binaural stethoscope, and/or with an electronic fetal heart monitor. Ideally, the midwife should use the Pinard, and then the electronic monitor, as the means of monitoring the heartbeat are different, and the former is more likely to identify a true fetal heartbeat (Gibb & Arulkumaran 1997). Having palpated the abdomen, the midwife should know where to listen for the fetal heart sounds, which are heard at their maximum at a point over the fetal shoulder. When the fetus is lying in an occipitoanterior or occipitolateral position, the heart sounds are heard from the front and to the right or left according to the side on which the fetal back lies (Fig. 32.11). The fetal heart sounds like the ticking of a watch under a pillow, the rate being about double that of the woman’s heartbeat observed at the wrist. The woman and her partner usually enjoy listening to their baby’s heartbeat too.

A uterine souffle, caused by the flowing of blood through the uterine arteries, may be heard; this is a soft, blowing sound, the rate of which corresponds to the woman’s pulse.

Abdominal findings throughout pregnancy

At first, only the height of the fundus is ascertained (see Fig. 32.4).

Engagement of the fetal head

There is a popular myth that engagement of the head occurs at 36 weeks in a primigravida. In about 50% of primigravidae, engagement of the head occurs between 38 and 42 weeks (Weekes & Flynn 1975), and in 80% of cases labour ensues within 14 days of the head engaging. In multigravidae, because of lax uterine and abdominal muscles, engagement may not take place until labour is established. If the head is engaged, the pelvic brim is certainly of adequate size and the probability is that the cavity and outlet are also adequate.