Diagnostic Sampling and Therapeutic Techniques

SMALL ANIMAL SAMPLING AND THERAPEUTIC TECHNIQUES

Administration of Medication in the Small Animal

LARGE ANIMAL SAMPLING AND THERAPEUTIC TECHNIQUES

Venous Blood Sample Collection

Arterial Blood Sample Collection

Thoracocentesis (Thoracentesis, Pleurocentesis, Chest Tap, Pleural Tap)

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 List and describe general principles for the collection of samples for laboratory testing.

2 Describe the patient's preparation, positioning, and procedures for blood collection from peripheral veins and capillary beds in small and large animals.

3 Describe indications and procedures for collection of arterial blood samples in small and large animals.

4 List and describe procedures for collection of urine samples from small and large animals and give advantages and limitations of each method.

5 Describe the indications and procedures for performing thoracocentesis, abdominocentesis, arthrocentesis, fine-needle aspiration, bronchoalveolar lavage, and collection of vaginal cytology samples in small and large animals.

6 Describe the indications and procedures for performing diagnostic peritoneal lavage.

7 Describe the two methods for performing a transtracheal wash and give advantages and disadvantages for each method.

8 Describe procedures for obtaining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and bone marrow aspirate samples and list indications, contraindications, and potential complications of the procedure.

9 List the routes used for administration of medications in small and large animals and describe procedures for administration of medications by each route.

10 Describe the procedure for placement and care of a peripheral intravenous (IV) catheter.

11 Describe the indications and procedure for placement and care of a jugular catheter.

12 List requirements for monitoring of patients with IV catheters.

13 Describe indications and methods for administration of oral medication of enteral feeding of small and large animals.

14 Describe procedures for collection and evaluation of milk samples from dairy animals.

15 Describe procedures for collection of rumen fluid in large animals.

BASIC GUIDELINES

Pretreatment blood and urine samples should be obtained before the administration of fluids and/or medications. The administration of fluids and the recent ingestion of a high-fat or high-protein meal may alter blood or urine laboratory values.

All supplies needed for the collection of samples and for therapeutic procedures should be gathered ahead of time. Samples should be collected and stored in appropriate containers with the patient's name and hospital identification number printed on each label.

Whenever a needle is inserted through the skin as a part of a treatment (e.g., subcutaneous injection) or a sampling procedure (e.g., bone marrow aspirate), the skin should be properly prepared and free from obvious inflammation and infection. Microbes and other contaminants present on the skin surface may be introduced into the underlying tissue when the needle is inserted. Needles and IV catheters from which the protective coverings have been removed should remain sterile and should only be handled at the hub (e.g., the shaft should not be touched or set down on a nonsterile surface).

The knowledge of potential risk or complications will place the veterinary technician in a position to be proactive rather than reactive to problems. The technician should be able to assess the patient and recognize when problems are occurring and have a “game plan” in mind for addressing the problems. For example, a technician knowledgeable in IV catheter complications is performing IV catheter care and notices that the catheter insertion site is erythematous, swollen, painful, and warm to the touch. The veterinary technician assesses the problem as thrombophlebitis, determines that a new catheter is needed, and removes the old one.

SMALL ANIMAL SAMPLING AND THERAPEUTIC TECHNIQUES

Veterinary technicians perform venipuncture on a routine basis, either to collect blood samples for laboratory tests or to inject a drug or medication. Proper animal restraint is as important as the venipuncture technique (Chapter 7). Blood samples must be collected with minimal trauma to the vessel and minimal stress and discomfort to the patient (Box 20-1). Patients’ stress can affect several laboratory tests (e.g., leukogram, cortisol and glucose concentrations).

A venipuncture is performed with either a needle and syringe or a Vacutainer collection system. The Vacutainer system consists of a double-pointed needle, plastic holder, and collection tubes with and without anticoagulants (Figure 20-1). The method and needle gauge selected depend on the vessel size, amount of blood required, intended use of the sample, and technician's preference.

FIGURE 20-1 The Vacutainer blood collection system is used to collect blood samples directly into the collection tunes. The system consists of a needle, holder, and collection tubes. (From Hendrix CM, Sirois M, editors: Laboratory procedures for the veterinary technician, ed 5, St Louis, 2007, Mosby Elsevier.)

The majority of venipunctures in cats and small dogs are performed with 22-gauge needles. Larger-gauge needles, such as 20- and 18-gauge, may be used in large-breed dogs and in most farm animals. For any venipuncture technique, the needle should always be inserted into the vein with the bevel facing upward.

Blood collected for coagulation profiles (i.e., activated clotting time, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) should be collected carefully with minimal tissue trauma and venous stasis. The needle should ideally penetrate the vessel on the first attempt to minimize the amount of tissue fluid that enters the sample; tissue fluid (thromboplastin) may initiate the clotting cascade.

Smaller, 25- to 28-gauge needles are used with smaller vessels, fragile vessels, or multiple venipunctures. Frequent sampling to establish a blood glucose curve is a situation in which the use of a small-gauge needle is appropriate. The amount of negative pressure applied to aspirate the blood into the syringe must not be excessive. Forceful retraction of the syringe plunger may result in hemolysis of the red blood cells as they pass through the needle, yielding erroneous laboratory values. The application of excessive negative pressure may also cause the vein to collapse.

Just before a venipuncture, the hair and skin over the vessel are wiped with a cotton ball saturated with 70% isopropyl alcohol. This helps to remove some superficial skin contaminants, causes vasodilation, and improves visualization of the vein. In animals with dense hair coats, the vessel may be easier to identify if the hair over the vessel is parted with the use of an alcohol-soaked cotton ball or shaved with a clipper. When blood is drawn for a bacterial culture, the region on top of the vein is shaved and aseptically prepared. Sterile gloves are worn when blood is collected for a culture.

The most important aspects of any venipuncture technique are the proper restraint of the animal and proper distention and immobilization of the vessel. These objectives are most easily accomplished when the procedure is done as a two-person project. The veterinary technician should only attempt the venipuncture when the vessel can be clearly delineated. Blind venipuncture attempts are doomed to failure and unnecessary patient's discomfort. If the technician is unable to locate the vessel (by visual inspection or digital palpation), the manner in which the vessel is distended and immobilized must be changed.

When collecting blood, excessive restraint should be avoided since it may incite more resistance from the animal than the venipuncture procedure itself.

To collect blood from a peripheral vein, introduce the needle into the occluded vessel as far distally as possible. If the initial venipuncture attempt is unsuccessful, reinsert the needle more proximal to the previous entry site. For a jugular venipuncture, the initial attempt is made in the caudal region of the jugular vein. Subsequent venipuncture attempts can be made in a more cranial region. If the vessel is damaged in the distal portion of the vein, a more proximal region is still patent and usable for blood collection.

After blood is collected, the needle is detached from the syringe, and the stopper is removed from the collection tube before the blood is transferred into the tube. This reduces the amount of hemolysis that may occur if blood is forcefully ejected through the narrow lumen of a needle. If blood is transferred into a tube containing an anticoagulant, such as lavender-topped ethylenediaminetetraacetic (EDTA) tubes, the stopper is quickly replaced, and the tube is gently inverted a few times to mix the blood with the anticoagulant. Vigorous shaking can cause hemolysis. The tube containing the anticoagulant should be at least half filled with blood to achieve the appropriate blood/anticoagulant ratio.

The most frequently used sites for canine blood collection are the cephalic, jugular, and lateral saphenous veins. The cephalic, jugular, femoral, and medial saphenous veins are used for feline venipunctures.

Cephalic Venipuncture: The patient may be positioned in sternal or lateral recumbency. The restrainer leans over the top of the animal and grasps the leg of interest at the elbow. The other hand and arm can be used to restrain the animal's head if the animal is awake to prevent an aggressive response to the skin puncture. If the animal is in sternal recumbency, the restrainer should lean on his or her elbow to help prevent the animal from withdrawing its leg at some critical time during the procedure. A tourniquet or thumb or forefinger is wrapped around the forearm at the level of the elbow. Pressure at this point occludes the cephalic vein. The skin is then rotated outward to roll the vein to the top (anterior) of the forearm.

The veterinary technician grasps the leg with one hand at the level of the metacarpus and further extends the leg. In “loose-skinned” animals, it may be necessary to flex the carpus. The objective is to tether the vein between the two points of traction (at the elbow and at the carpus) so that the vein is both distended and does not roll from side to side.

The needle is directed, as much as possible, along the longitudinal axis of the vein. The needle is inserted through the skin with the bevel facing up. The skin puncture is the painful part, and animals will often move in response to it. Once the animal has settled down, the needle can be directed into the vein. If blood does not spontaneously flow into the hub of the needle, gently aspirate to determine if the needle is or is not in the vein. If not, the needle should be advanced a bit farther and the process repeated. The needle can be advanced to its full length. If at this point the venipuncture has not been successful, the needle will have to be withdrawn to its subcutaneous (SQ) position (do not remove it entirely since another skin puncture will then be necessary). It is most important to withdraw the needle slowly, while gently aspirating. The deep wall of the vein may have been inadvertently penetrated, and the lumen will thereby be found as the needle is withdrawn.

Once the blood sample is taken or the drug is administered, the needle is withdrawn from the vein and digital pressure applied over the venipuncture site for at least 30 seconds. The site should be monitored for bleeding or hematoma formation for an additional several minutes.

Jugular Venipuncture: The patient may be positioned in sternal or lateral recumbency. Some large-breed dogs prefer to remain seated on the floor (Figure 20-2). Alternatively the patient is restrained on a table in sternal recumbency (Figure 20-3). One hand grasps the legs at the carpel joint and stretches the legs over the edge of the table. In any position, the head will need to be extended. Either the restrainer or the veterinary technician occludes the vein by applying occlusive pressure at the thoracic inlet. Care must be taken not to compress the trachea or impair breathing. Vein distention and immobilization can be maximized by pressing into the thoracic inlet in a caudal direction and by further extension of the head. Extensive longitudinal traction, however, can collapse the vein. With optimal positioning, the vein is easy to palpate (or visualize) and does not roll much from side to side. In sternal positioning, the venipuncture is usually done in a cephalad direction; in lateral positioning, the venipuncture is generally done in a caudal direction. The venipuncture is performed as previously described.

Lateral Saphenous Venipuncture: The patient is usually positioned in lateral recumbency (Figure 20-4). The restrainer grasps the upper leg at the stifle. The other hand and arm can be used to restrain the animal's forelegs and head if the animal is awake. Circumferential pressure is applied at the stifle to occlude and distend the vein. The veterinary technician grasps the leg with one hand at the level of the metatarsus. It should not be necessary for the veterinary technician to use his or her thumb to help immobilize the vein. The venipuncture is performed as previously described.

Medial Saphenous or Femoral Venipuncture: The medial saphenous or femoral vein is used to collect small volumes of blood. The patient is usually positioned in lateral recumbency. The restrainer grasps the lower leg at the stifle while reflecting the upper leg caudally with the forearm. The other hand and arm can be used to restrain the animal's forelegs and head if the animal is awake. Circumferential pressure is applied at the stifle to occlude and distend the vein. Alternatively, in the cat, grasp it by the scruff of the neck and place in lateral recumbency (Figure 20-5). The upper hind leg is abducted and flexed to expose the medial surface of the bottom leg. Applying pressure with the edge of the hand that abducts and extends the upper leg distends the vein. The veterinary technician grasps the leg with one hand at the level of the metatarsus. The venipuncture is performed as previously described.

Marginal Ear Venipuncture: On occasion, the technician will collect blood from a peripheral capillary bed to check for erythroparasitic organisms, such as Babesia spp. or Haemobartonella spp. The collection of a small drop of capillary blood is also used by clients who monitor their diabetic pets’ blood glucose levels at home. A peripheral capillary blood sample can be obtained by clipping the quick of a toenail or lacerating the buccal mucosa. A more desirable, less painful alternative is to collect a sample from the marginal ear vein, which is most easily visualized as it courses around the periphery of the dorsal aspect of the pinna.

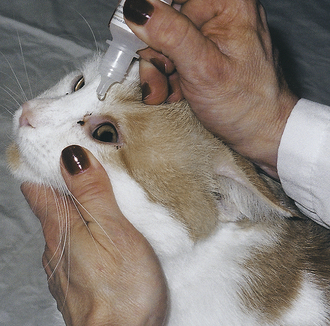

When a capillary sample is collected, the pinna of the ear is first warmed with a heated cloth, light source, or the technician's hands to help vasodilate the marginal ear vein and then wiped with a small amount of alcohol. A 25-gauge needle or lancet is used to nick the vein, and the pinna is massaged until a sufficient drop of blood is obtained (Figure 20-6). When a sample must be examined for erythroparasites, blood is collected into a heparinized capillary tube and is later smeared onto slides for a microscopic examination. If blood is collected to measure blood glucose, a Glucometer test strip is placed alongside the drop of blood on the pinna, and the blood is wicked directly onto the test strip. The test strip should be designed to measure a capillary, not venous, blood sample. The technician must make certain that the patient does not move its head or flick its ear, or the blood sample may be lost. After the blood sample has been obtained, firm pressure should be applied to the puncture site for approximately 15 seconds.

ARTERIAL BLOOD SAMPLE

One of the best ways to assess pulmonary function is through arterial blood gases. Blood gases tell us about the patient's ability to ventilate and oxygenate. Blood gases measure the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2—ventilation) and oxygen (PaO2—oxygenation) in the blood. Blood gas measurements are performed on a pH and blood gas analyzer. In the last few years, new inexpensive point-of-care instruments have been developed to measure pH and arterial blood gases. These analyzers are cost-effective and easy to use.

The collection of a blood sample for blood gas analysis entails a percutaneous puncture of an artery, such as the dorsal metatarsal or femoral artery. In the unconscious or anesthetized patient, the sublingual artery may be used. The dorsal metatarsal artery is smaller, but the interstitial connective tissues around it are “tighter” (compared with the femoral artery), which facilitates vessel positioning and minimizes postpuncture hematoma formation. The dead space of a 1- or 3-ml syringe (with a 25-gauge needle) is coated with lithium or sodium heparin (1000 U/ml); excess heparin is expelled from the syringe. In addition, a Vacutainer tube cork, alcohol swab, and a thermometer will be needed. When collecting the sample, care should be taken not to introduce air or apply excessive negative pressure, both of which can affect your PaO2 measurement. Once the sample collection is complete, withdraw the needle and apply digital pressure over the puncture site for at least 1 minute and monitor for bleeding or hematoma formation for another 4 minutes. Air is expelled from the syringe, and the syringe is capped with the cork and placed in an ice water bath if the lab test cannot be performed immediately. Blood gas samples may stay in an ice water bath for several hours before metabolism alters the pH or blood gas values.

Dorsal Metatarsal Artery Sample: An arterial puncture is usually done with the animal in lateral recumbency; however, it can be accomplished when the animal is standing if it resents the lateral recumbent positioning. If the patient is in lateral recumbency with the hock extended, it may be helpful to tape the paw to a table or sandbag. The pulse is palpated with one or two fingers of one hand (Figure 20-7). With the bevel up, the skin and arterial wall may be punctured in one motion following the path of the artery, or a two-step fashion: skin first then artery. Watch for a back flash of blood in the needle hub and then gently aspirate a 1- to 1.5-ml sample. If the arterial puncture is unsuccessful, the needle can be inserted a bit farther. As for a venipuncture, when the needle is withdrawn, it should be done slowly and with gentle aspiration applied to the plunger in case the deep wall of the artery was inadvertently punctured during the introduction. The needle is withdrawn to its SQ position, and the arterial puncture is reattempted.

Femoral Artery Sample: The arterial puncture is performed with the animal in lateral recumbency with the down leg extended caudally. The top leg should be positioned so that it is out of the way. After the puncture site is properly prepared, the first and middle finger of one hand locates the artery, and the leading edge of the same hand can be used to slide the skin and underlying SQ tissues toward the inguinal region. The femoral artery must be immobilized properly to prevent it from rolling away from the needle. The syringe is held at a 45-degree angle over the site where the pulse is strongest. The needle is advanced through the skin as previously described and the sample collected.

Arterial Catheter Placement: Arterial catheters are inserted for the continuous measurement of direct arterial blood pressure and for the collection of multiple arterial blood samples. The most common artery selected for catheterization is the dorsal metatarsal artery. The dorsal metatarsal has many advantages over the femoral artery. The cylindrical nature of the tarsus allows the catheter to be taped rather than sutured. There is less risk of hematoma formation and hemorrhage because of the tight SQ tissues. It is easier to maintain the catheter position because the catheter does not move and kink in the SQ tissues.

A 20- or 22-gauge over-the-needle (OTN) catheter may be placed in the dorsal metatarsal artery. The patient is placed in lateral recumbency with the hock extended, it may be helpful to tape the paw to a table or sandbag. The insertion site is clipped and aseptically prepared. The catheter is flushed with heparinized saline. The artery to be catheterized is palpated with one or two fingers of one hand. A relief hole is made completely through the dermis with the beveled edge of the needle (without entering the artery). The catheter is positioned SQ above the artery with the bevel up. The needle tip and artery are palpated simultaneously with the finger(s) of the opposite hand. The catheter is inserted into the artery steeply at first just so that the tip of the needle penetrates the upper wall of the artery and then flat against the skin surface and parallel with the longitudinal axis of the artery so that the bevel of the needle and the end of the catheter lie in the lumen of the artery. A “flash back” of blood should be seen in the hub of the needle; the catheter is gently advanced into the artery to its full length. The needle is replaced with a T-connector and stopcock. The catheter is taped in place and flushed with heparinized saline. See the section in this chapter on securing the peripheral catheter.

The catheter is either attached to a continuous flush system or flushed with heparinized saline every 2 hours. The toes should be checked for warmth every 2 to 4 hours. If the toes are cool, the catheter will need to be removed. Catheter care is performed every 48 hours.

URINE SAMPLE COLLECTION

A urine sample may be obtained by several methods. The veterinary technician should be familiar with the various techniques. Urine is most often collected for a gross and microscopic analysis and a culture if indicated. Common collection techniques include obtaining urine from the patient as it voids, from manual expression of the bladder, from catheterization of the bladder, and by cystocentesis. Most references advocate a volume of 7 to 10 ml for a quantitative urinalysis; however, for example, smaller samples are sufficient for a culture or spot assays for ketones or glucose.

Urine collected is stored in clean, dry containers. Urine that is collected and to be cultured is collected and submitted in sterile containers. Samples that are not analyzed within 30 minutes of collection are refrigerated in secured sealed containers. Urine samples are returned to room temperature before the analysis.

VOIDED COLLECTION

A naturally voided sample is easy to collect. It is most commonly obtained from canine patients by walking the dog outdoors and catching a midstream sample. These samples are adequate for a routine urine analysis. They are not acceptable samples for a culture because these free-catch samples contain bacteria, cells, and debris from skin, hair, and the genitourinary tract. The initial void of urine contains the greatest concentration of contaminants and should be excluded from collection. Innovative collection devices can be easily made to catch the urine of a voiding dog because most dogs stop urinating if a person gets too close. Examples are devices made of a log rod or a straightened clothes hanger with a loop at one end holding a disposable cup or container.

Hospitalized patients can be elevated on a raised grate in a clean cage. The urine is collected from the cage floor with a syringe after the animal urinates.

Fresh voided urine samples of cats are obtained from litter boxes that are clean and empty. Lining the litter box with a plastic bag or clear plastic food wrap aids in collecting the sample. For cats that prefer litter in the boxes, shredded wax paper or specialty nonabsorbent litter made of plastic beads, such as NOSORB (Catco, Inc., Cape Coral, Fla.) are options. After the cat urinates in the litter pan, the urine is collected by a syringe or poured into a clean container.

MANUAL BLADDER EXPRESSION

Urine collected by manual expression of the bladder can be used for a routine urinalysis, but should not be used for a culture because the urine obtained by this method will contain contaminants from the lower urinary tract, skin, and hair. Bladder expression can be difficult to accomplish in some patients because the transabdominal compression causes the pressure inside the bladder to increase, but the urethral sphincter may not relax simultaneously. Manual expression of the urinary bladder is warranted in patients with neurologic impairments when the animal cannot initiate voluntary urination or does not have the ability to completely empty the bladder.

To perform manual expression of the urinary bladder, place a hand on either side of the caudal abdomen of a patient that is standing or in lateral recumbency. Isolate the bladder between the palmar surfaces of the fingers, and apply firm and steady pressure until urine is produced. In small-breed dogs and in cats, it is possible to use only one hand.

If urine cannot be produced by manual expression with moderate compression, an alternate method of emptying the bladder or obtaining a sample must be employed. Do not overexert pressure. Extreme caution is exercised in patients with an overly distended bladder in the presence of urethral obstruction, such as seen in obstructed male cats. Urethral or vesicular rupture may occur in these patients.

CATHETERIZATION

Indications for urinary catheterization include a urine sample collection, to empty the bladder, to relieve a urethral obstruction, to allow access to the urinary tract for radiographic studies, and for conditions in which an indwelling urinary catheter is indicated. Complications of urinary catheterization include a urinary tract infection, particularly with indwelling catheters or in patients with immunosuppression. Even though aseptic techniques are employed while placing the catheter, it may induce urethral inflammation and a bacterial urinary tract infection. Furthermore, urethra and bladder irritation and trauma can be other complications. Trauma from catheterization may cause increases in the red blood cell count, protein, and the number of transition epithelial cells in the sample. Urine samples may also contain contaminants from the genital region and urethra. Urine obtained by catheterization is, however, acceptable for a bacterial culture if a sample cannot be obtained by cystocentesis.

Indwelling urinary catheters are placed in patients at risk for urethral obstruction, such as male cats who have recently had urethral calculi removed, and also in patients with neurologic impairment or traumatic conditions that interfere with normal urination. Catheterization is also an important part of quantizing urinary output.

The prepuce or vulva is gently rinsed with a warm antimicrobial solution and water twice and then dried. Sterile gloves are worn to detach or connect the catheter to extension tubing or a collection system. A closed system is created by connecting the catheter to IV extension tubing that is connected to a sterile collection bag. Commercial urinary collection bags are available on the market, or an empty sterile fluid bag can be used. The collection bag serves as a urine reservoir. Its contents must be measured and emptied periodically.

Indwelling urinary catheters should be inspected for occlusion. The patient is also monitored for adequate urine output. A normotensive, normovolemic patient with intact renal function should produce 1 to 2 ml of urine per kilogram of body weight per hour. If there is not adequate urine in the reservoir bag, the patient's urinary bladder should be palpated for distention. The urinary catheter should be inspected for obstructions or kinks. The bladder can be gently compressed to determine whether urine will flow through the catheter. A small volume of sterile 0.9% saline solution can be flushed through the catheter as an attempt to relieve an obstruction.

Indwelling urinary catheters should be removed as soon as possible to reduce the inflammation of the urinary tract and catheter-induced infections. If catheterization is required long term, a new catheter should be placed every 4 to 5 days.

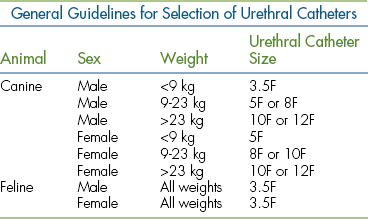

Urinary catheters are available in French sizes. See Table 20-1 of general guidelines for catheter selection. Note the length of available urinary catheters on the market. Many catheters that are manufactured for the human market do not possess the length for large breed canine male anatomy. Likewise, long-length catheters should be premeasured externally on the patient and excessive lengths not advanced in smaller patients because the catheter can tie itself in a knot within the urinary bladder, making withdrawal impossible without surgical intervention. Measurement therefore is made to the caudal portion of the bladder.

Male Dog

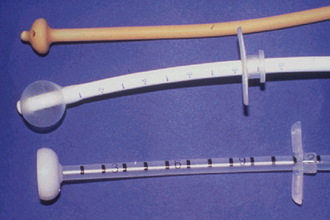

The placement of a urinary catheter in a male dog is not difficult unless a urethral obstruction exists. Polypropylene urinary catheters are rigid and easy to pass into the urinary bladder for a sample collection or to empty the bladder. If the catheter is to remain indwelling, a softer, flexible feeding tube or silicone self-retaining Foley catheter is more desirable and comfortable for the patient.

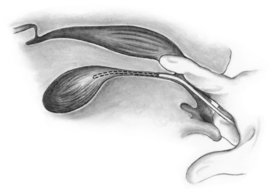

The dog is placed in lateral recumbency with the upper leg abducted. Carefully clip any long hairs around the preputial orifice. Flush the prepuce with a dilute antiseptic solution and rinse with warm sterile saline solution or water. An assistant retracts the prepuce so that the tip of the penis is exposed and maintains this position. The tip of the penis is gently washed with an antiseptic solution and rinsed with warm saline solution or water. Sterile gloves are donned. The catheter is taken aseptically out of the packaging, and the distal tip of the catheter is lubricated with a sterile water-soluble lubricant or sterile lidocaine ointment. If sterile gloves are not worn, the catheter should be kept wrapped so that it can be handled aseptically as it is advanced through the urethra. Sterile scissors can be used to cut a movable “butterfly” tab at the end of the packaging. The tab is then used to feed the catheter into the bladder and allows the operator to avoid touching the sterile catheter (Figure 20-8).

FIGURE 20-8 Urinary catheterization of a male dog. A butterfly tab is used to aseptically advance the catheter through the urethra. (From Ettinger SJ, Feldmen E, editors: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier Saunders.)

Insert and advance the catheter into the urethra. The catheter should never be forced. If the catheter cannot be passed, a smaller catheter should be used. It is common to feel some resistance at the level of the os penis, the portion of the urethra that curves around the ischial arch, and at the level of the prostate gland in older intact males. Steady gentle pressure should overcome this slight resistance. The catheter can be guided around the curvature at the ischial arch by applying digital pressure on the perineum externally or by pressing the catheter with an index finger placed in the rectum.

Urine should flow into the catheter as it enters the neck of the bladder. The catheter is then advanced 1 cm farther or to the predetermined measurement. A sterile syringe is attached to the catheter, and urine is slowly aspirated from the bladder. The first few milliliters of urine suctioned from the catheter should be discarded because it may contain contaminants and should not be submitted for a urinalysis or culture.

The catheter may be withdrawn from the bladder when the desired procedure is completed. If the catheter is to remain in the bladder, it must be secured. If the catheter is a self-retaining Foley catheter, the appropriate volume of sterile saline or water is injected into its distal balloon cuff via the one-way valve at the proximal end of the catheter. The catheter must be secured in the following fashion (optional for a Foley catheter): Two stay-suture loops are made through the skin on two sides of the distal prepuce with 3-0 or 4-0 nylon suture material. An adhesive tape “butterfly” tab is folded around the catheter and over on itself at the location where the catheter exits the penis. A suture is then passed through one side of the tape and then through the nylon loop in the prepuce. This is repeated on the other side of the tape and the other nylon loop in the prepuce. This secures the catheter to the prepuce so that it remains in place. The stay-suture loops remain in place in the prepuce and allow catheter adjustments or changes without having to pass another needle through the prepuce.

Female Dog

Urinary catheterization is more challenging in the female dog than in the male. Catheterization can be accomplished with the patient in a standing position, in lateral recumbency, or sternal recumbency with the hind legs dangling from the end of the table. On a conscious dog, it is preferred that the dog stand with its hindquarters positioned at the end of an examination table. The assistant should support the patient under the abdomen to prevent lowering of the hindquarters during catheterization. Excessive long hairs are clipped from the vulvar area. The vulva and perineal areas are gently washed with a dilute, warm antiseptic solution and rinsed with sterile saline solution or water. The ventral vaginal floor is instilled with 1.0 ml of sterile 2% lidocaine jelly. The two techniques to pass the catheter are by visualization with the use of a speculum and a light source or a blind technique using a digit to palpate and guide the catheter. A sterile speculum is used for a visualization of the urethral orifice. Examples of a speculum include a lighted vaginal speculum, a Killian nasal speculum, an otoscope fitted with a large-diameter speculum, and a laryngoscope blade. The speculum of choice is gently inserted into the vagina. Exercise caution to avoid the clitoral fossa. After donning sterile gloves, insert the speculum vertically and straighten to horizontal when the pelvic canal is entered. With the aid of a light, locate the urethral papilla and urethral opening and insert a lubricated catheter. The papilla and urethral orifice can be found 2 to 4 cm into the vagina in most dogs (Figure 20-9). Advance the catheter until urine is obtained or at the premeasured length. If a speculum is not available, the blind technique can be performed. Wearing sterile gloves, the technician places a lubricated finger into the vagina and slides it 2 to 5 cm along the ventral floor until the papilla and external urethral orifice is located. The catheter is introduced into the vagina and guided into the urethral orifice by the finger in the vestibule. The technician will acknowledge the proper placement by palpating the catheter within the urethral orifice and not in the cranial vestibule (Figure 20-10). The catheter is advanced until urine is obtained or at the premeasured length. A sterile syringe is attached to the catheter, and gentle negative pressure is applied for the desired sample. If the catheter is to remain in place, it is ideal to select a self-retaining Foley catheter. Once the catheter is placed in the bladder, the balloon cuff is inflated with the appropriate volume of sterile saline or water to prevent the catheter from slipping out of the bladder. The catheter is then taped to the tail to prevent the dog from stepping on it. A closed collection system is placed on the free end of the Foley catheter.

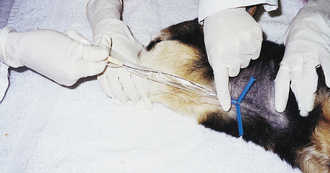

Male Cat

Routine catheterization of male cats for a urine collection is rare. The most common reason for catheterizing a male cat is to relieve a urethral obstruction. Catheterization of male cats will often warrant the use of sedation or a general anesthetic. Exercise extreme caution when sedating obstructed cats. Cats that have been obstructed long term are often obtunded and hyperkalemic and should therefore be carefully evaluated and monitored before the administration of anesthetic agents. The cat is placed in lateral or dorsal recumbency with his hind legs drawn cranially. The prepuce is retracted to expose the glans of the penis (Figure 20-11). The perineum is prepared aseptically as described for the male canine catheterization, and the penis is extended dorsally so that the urethra is parallel to the vertebral column. An evaluation of the tip of the penis of an obstructed cat should be done at this time. Wearing gloves, first palpate the tip of the penis to check for the presence of a distal urethral plug or calculus. If an obstruction is present in the tip of the penis, gently massage the penis between the thumb and forefinger to attempt to dislodge the plug. If this is unsuccessful, proceed with catheterization. With sterile gloves, lubricate a 3.5F polypropylene or silicone tomcat catheter and pass it into the urethra. If resistance is met, the catheter is slightly withdrawn and slightly rotated as it is readvanced. If the catheter cannot be easily advanced, a small volume of sterile saline or water is injected through the catheter. Extreme care must be exercised when attempting retropulsion of a urethral calculus. Avoid excessive force or volume of fluid that could result in significant urethral trauma or rupture of the urinary bladder. Once the catheter is placed and there is good urine flow, secure the catheter in place in the same fashion described for the male dog. The cat should be fitted with an Elizabethan collar to prevent removal of the catheter and urine collection system.

Female Cat

Routine catheterization of female cats for a urine collection is also rare. Just as in the male cats, this is due to difficulty and sedation requirements. The cat is placed in sternal recumbency, and the perineal region is prepared aseptically. The technician dons sterile gloves, the lips of the vulva are pulled caudally, and a sterile 3.5F catheter is inserted into the vagina. Keeping midline, the catheter is advanced. The urethra papilla is located about 0.7 to 1.0 cm within the vagina. The catheter should pass into the urethra with little resistance. When urine flows out of the catheter, attach a syringe. Discard the first 1 to 2 ml of urine that flows and obtain a second sample for an analysis. Remove the catheter or secure the catheter in place and attach a closed urine collection system as previously described.

CYSTOCENTESIS

Cystocentesis is the percutaneous aspiration of urine from the bladder. A cystocentesis procedure is indicated to obtain a sterile urine sample for analysis and/or culture and sensitivity testing. The sample is free of bacteria, cells, and debris from the lower urinary tract. It also minimizes iatrogenic urinary tract infections caused by catheterization, especially in patients with preexisting diseases of the urethra and/or urinary bladder. Cystocentesis sampling can also aid in the localization of hematuria, pyuria, and bacteriuria. Cystocentesis is used as a last resort to empty an overly distended bladder when a urethral obstruction prevents urinary catheterization. The common contraindication for cystocentesis is an attempt to perform the procedure when there is inadequate urine in the bladder or when the patient resists restraint and abdominal palpation. It is recommended to wait until there is sufficient urine in the bladder or seek ultrasound guidance along with proper physical and chemical restraint, if necessary. Although statistically rare, laceration of the bladder and laceration of the bowel resulting in peritonitis add to the complication list. Patients having recent abdominal surgery or trauma, suspected bleeding disorders, pyometra, or suspected caudal abdominal or bladder tumors should not undergo cystocentesis procedures.

Supplies needed to perform a cystocentesis in canine and feline patients include a 22-gauge, 1- to 1.5-inch needle attached to a 12-ml or larger syringe. The patient can be standing, in lateral recumbency, or ventral recumbency. The site is ventral or ventrolateral insertion into the bladder wall, depending on the patient's positioning. When cystocentesis is performed, most but not all of the urine should be removed from the bladder. Excessive pressure from a full bladder might lead to extravasation of urine from the puncture site when the needle is withdrawn. On the other hand, the removal of the entire volume of urine increases the risk of contact between the needle and the bladder wall, which may result in damage to the bladder. Thus it is ideal to insert the needle a short distance cranial to the trigone region of the bladder. Having the needle a short distance cranial to the junction of the bladder with the urethra rather than the vertex of the bladder, permits the removal of urine and decompression of the bladder without the need for reinsertion of the needle into the bladder lumen. If the needle is placed in or adjacent to the vertex of the bladder, it may not remain in the bladder lumen because the bladder progressively decreases in size following the aspiration of urine. Furthermore, the technician should position the needle at a 45-degree angle through the bladder wall, creating an oblique needle tract. By directing the needle in this fashion, the elasticity of the vesicle musculature and the interlacing arrangement of the individual muscle fibers will provide a better seal of the small pathway created by the needle when it is removed. Procedures for ventrolateral (Figure 20-12) and ventral cystocentesis (Figure 20-13) procedures are outlined in Box 20-2. Note that in male dogs the prepuce and penis are diverted laterally, and the needle is inserted on the ventral midline or slightly paramedian. If blood enters the needle, another cystocentesis attempt is made with a different needle and syringe. The needle should never be redirected once it is in the abdominal cavity because accidental laceration of viscera may occur. Lastly the technician needs to remember to always release negative aspiration pressure on the plunger of the syringe before withdrawing the needle and syringe apparatus.

FECES SAMPLE COLLECTION

Fecal samples are commonly collected from the ground, floor, cage bottom, or litter box after the animal defecates. Alternative methods include a lubricated fecal loop or a gloved finger inserted into the rectum to remove feces. Gross and microscopic examinations of feces for mucus, blood, intestinal parasites, and ova are commonly performed in veterinary practices. Fresh fecal samples are placed in a sealed container or bag. If the samples are to be checked for parasites but are not examined for several hours, the samples should be refrigerated. Refer to Chapter 17 for more information about a sample collection for a parasitologic examination.

THORACOCENTESIS

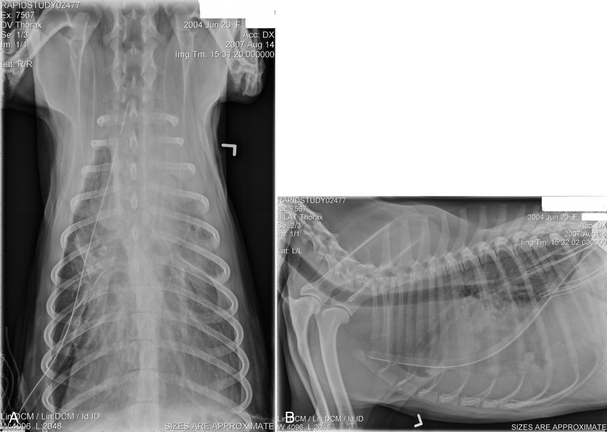

Thoracocentesis is a procedure, which may be used to diagnose or treat pleural filling defects (pneumothorax or pleural effusion). Air and fluid, which may compress the lungs within the pleural cavity, can be removed via thoracocentesis allowing the lungs to reexpand. Pleural filling defects should be considered when the patient has tachypnea; short, shallow breaths; respiratory distress; open-mouth breathing; and cyanosis. Chest auscultation may reveal diminished or absent breath sounds and muffled heart sounds. If a pneumothorax or pleural effusion is suspected, oxygen should be administered, and a thoracocentesis should be performed to stabilize the patient before stressing the patient while taking radiographs.

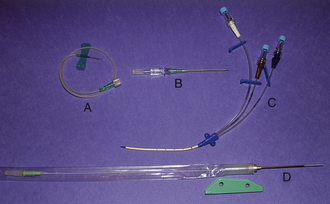

The veterinary technician sets up for thoracocentesis by gathering sterile gloves, a 2-(5.08 cm) to 5-inch (12.7 cm) OTN catheter, IV extension tubing, three-way stopcock, syringe, #15 scalpel blade, 2% lidocaine, clippers, antiseptic scrub and solution, and lab tubes (EDTA and clot tubes and culture transport media). The thoracocentesis is performed at the seventh to eighth intercostal space. An area several inches in diameter is clipped and surgically prepared. It is best to prep an area on the thorax dorsally for the collection of air and ventrally for fluid. Lidocaine (1 to 2 ml) is injected into and around the intended insertion site.

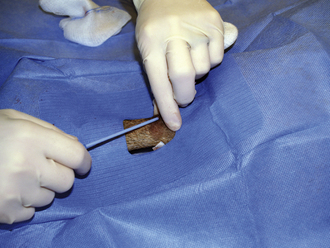

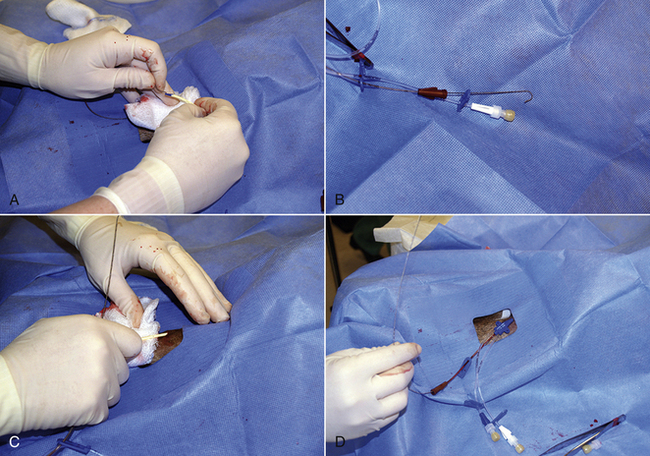

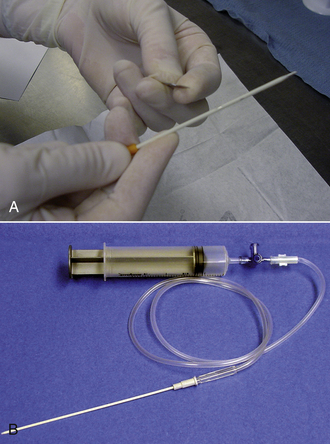

After putting on surgeon's gloves, assemble the equipment. It is helpful to add two or three small fenestrations to the catheter with the scalpel blade. Attach the stopcock to the syringe, and attach the extension tubing to the stopcock (Figure 20-14). An additional extension tube can be added to the free port of the stopcock and the end of the tube placed in a bowl or graduated cylinder to collect the pleural fluid.

FIGURE 20-14 A, Using a blade to place two to three fenestrations in an OTN catheter. B, The setup for a thoracocentesis using a syringe, stopcock, extension tubing, and OTN catheter.

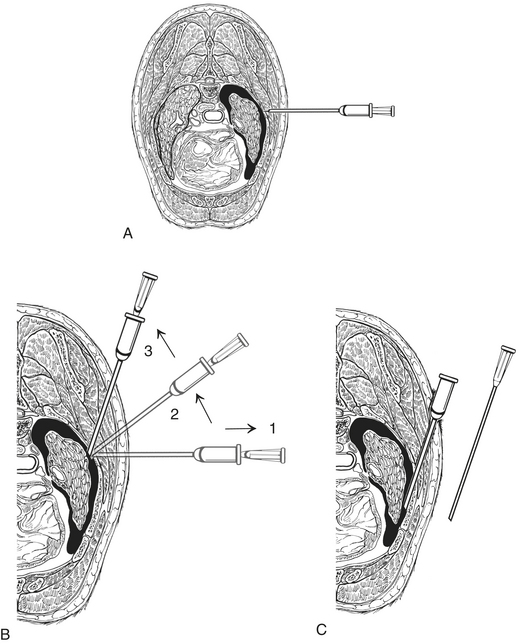

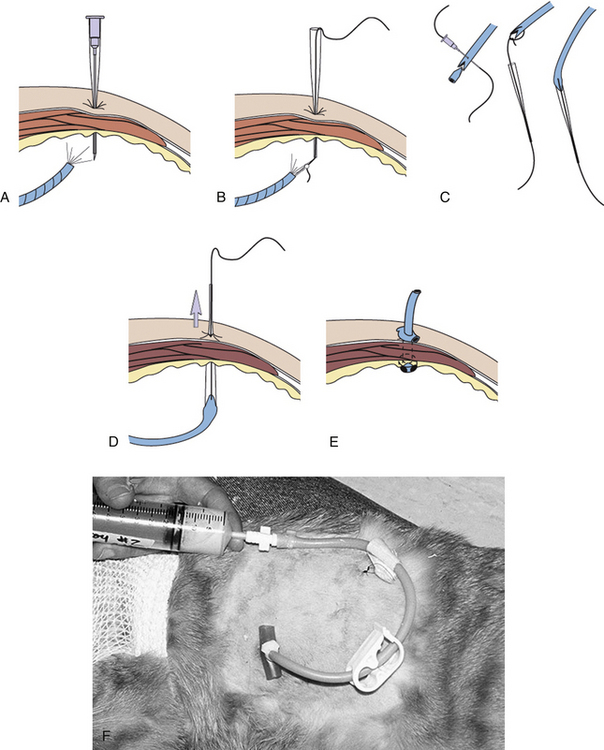

The patient may be standing or placed in either sternal or lateral recumbency. Intercostal vessels and nerves run along the caudal aspect of the rib, therefore the catheter will be inserted in the caudal aspect of the intercostal space and cranial to the anterior edge of rib. With the catheter perpendicular to the chest wall, the catheter is advanced gradually through the chest wall until a flash of fluid is seen in the hub or a pop is felt. The angle on the catheter is changed so that it is in the direction parallel to the long axis of the rib. The catheter is advanced a few millimeters so that the tip of the needle does not extend beyond the catheter; the needle and catheter are directed ventrally. The catheter is advanced off of the needle; the catheter is quickly attached to the extension tubing (Figure 20-15). In cats, a butterfly catheter can be used instead of extension tubing and catheter. In this instance, the needle is inserted in a direction that is parallel to the long axis of the rib with the bevel facing the thoracic cavity. If the thoracocentesis is nonproductive, it may be necessary to withdraw a few millimeters and redirect the catheter or needle. Using gentle pressure, aspirate until you achieve a slight negative pressure or until the patient's condition improves. Ultrasound can also be useful for determining the endpoint for the procedure.

FIGURE 20-15 An OTN catheter is used to perform a thoracocentesis. A, The catheter is perpendicular to the chest wall and is advanced through the chest wall gradually. B, The needle is withdrawn slightly and the angle of the catheter changed so that it is parallel to the long axis of the rib. C, The catheter is advanced into the pleural space, and the catheter is attached to the extension tube, and gentle aspiration is applied. (From King LG: Textbook of respiratory disease in dogs and cats, St Louis, 2003, Saunders.)

Complications include: pneumothorax, lung laceration, and laceration of an intercostal vessel or internal thoracic artery leading to hypovolemia secondary to hemothorax.

Postthoracentesis nursing care includes close observation, respiratory rate measurement, auscultation of lung sounds, and measurement of oxygen saturation with a pulse oximeter. Lab samples may be submitted for cell count, total protein, cytology, biochemical analysis (e.g., triglycerides, glucose, and lactate), and culture and sensitivity.

ABDOMINOCENTESIS

Abdominocentesis is the aspiration of fluid from the abdominal cavity. The procedure is considered diagnostic and therapeutic. It can aid in the diagnosis of hemoabdomen or uroabdomen, peritonitis, or ascites (from cardiac or hepatic causes). It is not indicated when the patient has suffered a penetrating abdominal injury or is suspected of having a pyometra.

The veterinary technician sets up for the procedure by gathering sterile gloves, two to four 20- or 22-gauge needles, syringe, clippers, antiseptic scrub and solution, and lab tubes (EDTA and clot tubes and culture transport media). The abdominocentesis is performed at the right, midabdominal region so as to avoid the liver, spleen, and urinary bladder. An area several inches in diameter is clipped and surgically prepped. A local anesthetic is not usually necessary. The patient may be standing or placed in either sternal or lateral recumbency. Using aseptic technique, the needle is gently introduced into the peritoneal cavity. Gently aspirate or allow fluid to flow from the hub into the test tubes. Rotation of the needle or the placement of a second needle into the abdomen 2 cm from the first can stimulate fluid flow. If no fluid is retrieved, the procedure should be repeated in one or two other locations. As an alternative, the abdominocentesis can be performed with an 18- to 20-gauge OTN catheter.

This procedure has a high incidence of false-negative results. Large volumes (5 to 7 ml/kg) of peritoneal fluid are necessary for detection by this method. The use of a syringe can increase the likelihood of false-negative results as a result of the occlusion of the needle with omentum or viscera. If the abdominocentesis result is negative, a diagnostic peritoneal lavage may be indicated.

Postprocedure nursing care includes monitoring of vital signs, observing for pain, abdominal distention, and continued bleeding or bruising of the centesis site. Lab samples may be submitted for cell count, packed-cell volume, total protein, cytology, biochemical analysis (e.g., creatinine, potassium, bilirubin, and lactate), and culture and sensitivity.

DIAGNOSTIC PERITONEAL LAVAGE

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) is the infusion of fluid into the abdominal and then the retrieval of the fluid for laboratory analysis. It has a higher diagnostic accuracy than abdominocentesis. The indications are the same as abdominocentesis or when the abdominocentesis result is negative. DPL has the same contraindications as abdominocentesis and is also not indicated when there is historical, physical, or radiographic evidence for the need for an exploratory laparotomy. Caution should be exercised in those patients with respiratory distress because the instilled fluid will place pressure on the diaphragm and potentially impair ventilation.

The veterinary technician sets up for the procedure by gathering a peritoneal lavage catheter or a long OTN catheter, IV administration set, isotonic crystalloid, basic surgical set, sterile gloves, lab tubes (EDTA and clot tubes and culture transport media), lidocaine, and surgical prep materials.

The bladder is emptied, and the patient is placed in lateral recumbency. The skin of the ventral abdomen is clipped and prepared caudal to the umbilicus. The skin and abdominal wall are infiltrated with lidocaine. If a peritoneal lavage catheter is used, the veterinarian may make a small midline incision just caudal to the umbilicus through the skin, SQ tissue, and superficial abdominal fascia. As an alternative, the veterinarian may make the incision just to the right of the umbilicus so as to minimize the risk of trauma to the spleen and descending colon. If an OTN catheter is used, the veterinarian will make a stab incision. The catheter is inserted through the incision and directed caudally and dorsally. The catheter is gently aspirated; if a diagnostic sample is obtained, there is no need to perform the lavage. If not, approximately 20 ml/kg of warmed crystalloid solution is infused into the abdomen. The patient is gently rocked from side to side. The fluid is allowed to flow freely from the catheter or gently aspirated. If the fluid is clear, the catheter is removed; otherwise, it is sutured in place temporally for serial evaluations.

Post-DPL nursing care is the same as abdominocentesis.

TRANSTRACHEAL WASH

It has been proven that culture swabs of the pharynx and the tonsil region are unreliable in evaluating lower respiratory tract disease because of the contamination of samples with oral flora (Bordetella may be an exception). Appropriate sampling is obtained more consistently by using techniques that bypass the mouth and oropharynx completely. Transtracheal lavage and aspiration provide a means to obtaining material from the tracheobronchial tree for a culture and cytology that is uncontaminated by the oral cavity. The technique is simple, clinically useful, and can be accomplished in a relatively short time period.

The veterinarian makes the decision to perform a transtracheal lavage based on clinical, radiographic, and hematologic findings. Specific examples for indications include: acute bronchopneumonia for a culture and cytology of the provocative agent; identifying the presence of inflammation and whether likely infectious or noninfectious; identification of the cells involved in inflammation (eosinophils, neutrophils, etc.); identification of parasitic eggs or larvae; identification of infectious agents (bacteria, fungi); and the identification of abnormal tracheobronchial cells (chronic inflammatory changes, neoplastic cells). The patient most likely will have a chronic productive cough. Patients may elicit a cough upon a physical examination by external palpation of the laryngeal area.

Patients who are not ideal candidates for a transtracheal lavage procedure are those with severe respiratory distress and are compromised when manipulated. Patients with coagulopathy conditions may require plasma transfusions before the procedure or may be best suited for a tracheal lavage procedure through a sterile endotracheal tube (see endotracheal lavage).

Risks or complications relative to the procedure include postprocedural hemorrhage, SQ emphysema, acute dyspnea, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and iatrogenic infection.

Note that it is best to have the patient awake with a cough reflex present. Therefore heavy sedation or a general anesthetic is not advised for the procedure. An oxygen source, including a facemask, should be at hand at all times. Preoxygenation of the patient via a facemask is advised, even in eupneic animals. The following describes the common procedure techniques and approaches to tracheal lavages.

PERCUTANEOUS TECHNIQUE

Equipment: A firm 16-gauge × 2-inch indwelling OTN catheter, a 3.5 Fr polypropylene urinary catheter, 20-ml or 35-ml syringe filled with sterile nonbacteriostatic saline (approximately 0.5 to 1.0 ml/kg of body weight), three-way stopcock (optional), #11 scalpel blade (optional), sterile gloves, 2% lidocaine drawn up in a syringe, bandage material (sterile 2- × 2-inch gauze with antiseptic gel, plus gauze roll and tape). Alternatively, you can also use a 14-gauge catheter and a 5 Fr urinary catheter. Technique:

1. Positioning. Restrain the animal either in sitting or sternal recumbency. Large-breed dogs are managed better on the floor and in a corner of a room. Extend the animal's head dorsally so that the nares point toward the ceiling.

2. Site. Cricothyroid ligament or intertracheal membrane (through trachea between cartilage rings). For the latter approach, it is generally practiced to use a lower site near the thoracic inlet in large-breed dogs to ensure that the catheter tip will reach the tracheal bifurcation (dependent on catheter length).

3. Preparation. Standard clipping of hair and surgical prep over area. Infiltrate with 2% lidocaine to level of ligament.

4. Incision. Stab incision 2 to 3 mm is optional. No suturing required. Alternatively, tenting of the skin and introduction of catheter through the skin before positioning and advancing through cricothyroid ligament or intertracheal membrane is advised.

5. Placement of catheters. Rigid 16-gauge indwelling catheter with stylet in place is placed through SQ tissues to level of the ligament. Steady the trachea with one hand, and with the other hand hold the catheter. With firm action then pass through ligament and into lumen of trachea. The catheter angle should be at 45 degrees once in the tracheal lumen, pointing down toward the tracheal bifurcation. Advance the catheter over the stylet and remove stylet. Keep a hand on the hub of the catheter at all times. Next, verify placement by attaching a syringe to the catheter in place in the trachea. Air should be easily aspirated. Pass the urinary catheter through the indwelling catheter to a predetermined level (measure from larynx to caudal border of the scapula to approximate distance to tracheal bifurcation) (Figure 20-16).

6. Obtaining sample. Attach a sterile 20-ml or 35-ml syringe containing no more than 10 ml of nonbacteriostatic saline to the urinary catheter. Rapidly infuse the saline and aspirate while slightly moving the urinary catheter back and forth in the trachea gently. It may be helpful to coupage the animal's chest at this time because the greatest amount of material will be aspirated if suction is applied while the animal coughs. Repeat this procedure until the fluid in the syringe is cloudy or contains visible clumps of mucus. The presence of the optional stopcock allows air to be evacuated from the syringe without disrupting the assembly. If desired, repeat aspiration procedure with a new syringe for two samples: one for a culture and one for cytology. When the procedure is complete, cap the syringe containing the lab samples with a new needle. Note: Do not expect to retrieve all of the saline infused through the catheter. A yield of 20% to 25% is common.

7. Patient monitoring. Monitor the patient closely during the sample collection. Oxygen can be delivered directly through the catheter or by facemask, if necessary.

8. Removal of catheters. Remove urinary catheter first, then the indwelling catheter. This will prevent contamination of soft tissues with the catheter tip.

9. Bandage placement. A light pressure wrap with a sterile 2- × 2-inch gauze square with antiseptic dressing applied on the entry site is sufficient. This may prevent excessive bleeding or SQ emphysema.

Method 2: Through-the-Needle Catheter

Equipment: Through-the-needle catheter, 19-gauge × 12 inches, 20-ml syringe filled with 10 ml of nonbacteriostatic saline, three-way stopcock, #11 scalpel blade (optional), sterile gloves, 2% lidocaine drawn up in a syringe, bandage material (sterile 2- × 2-inch gauze with antiseptic gel, plus gauze roll and tape). Technique:

1. Positioning, site, preparation, and incision (steps 1 to 4) are the same as in method 1.

2. Placement of catheter. The trachea is stabilized with one hand while holding the catheter with the other hand. The needle of the catheter is placed through the SQ tissues until it contacts the ligament. The angle of the needle is perpendicular to the trachea with the bevel pointing down. With a firm action, introduce the needle through the ligament, and then change the angle of the needle to 45 degrees, pointing downward toward the tracheal bifurcation. Advance the catheter through the needle, sliding the catheter down the enclosed plastic housing. Make sure the needle is pointing down toward the bifurcation. If not, the catheter may feed back up through the larynx and cause the animal to chew or gag. After advancing the catheter to its full length, withdraw the needle from the trachea and skin, leaving the catheter in place. If the needle is left in the trachea and the animal begins to move, the catheter may be severed off by the needle tip, leaving the catheter as a foreign body in the trachea. The needle guard provided with the catheter should be placed over the needle at this point to prevent injury to the animal or cutting of the catheter with the exposed sharp tip.

3. Obtain the sample and monitor the patient the same way as described in method 1 (steps 6 to 7).

4. Withdraw the catheter. Remove the catheter from the trachea and skin, making sure not to cut the catheter with the needle.

5. Bandage placement. Same as described in method 1 (step 9).

Method 3: Sterile Endotracheal Tube

Equipment: A sterile endotracheal tube suitable for the patient's size. A 5F or larger polypropylene urinary catheter, 20-ml syringe filled with sterile nonbacteriostatic saline, three-way stopcock, sterile gloves, 2% lidocaine (for feline patients to facilitate intubation and reduce laryngeal spasms), laryngoscope, gauze roll to secure endotracheal tube, anesthetic agents necessary to achieve intubation with endotracheal tube.

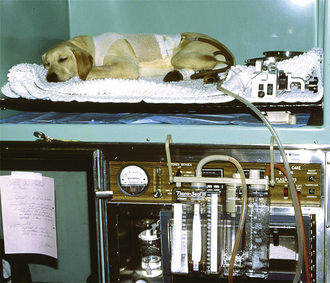

1. An anesthetic plan should be established for the patient. It is necessary to induce anesthesia in the animal just to the depth necessary to cleanly place a sterile endotracheal tube. Care should be taken not to contaminate the tip of the endotracheal tube in the oral cavity. Laryngeal spasms may be reduced, especially in the feline patient, with the use of a few drops of 2% lidocaine placed on the arytenoids before intubation. Common anesthetic agents used are ketamine hydrochloride and diazepam, propofol, and thiopentathal. Monitor the animal closely. Apnea is a common finding with propofol and barbiturate induction agents. Once the endotracheal tube is placed and secured with roll gauze, the animal can be allowed to recover from the induction dose to a lighter plane of anesthesia so that a cough response is elicited when the procedure is performed. It is necessary to hold the head of the patient in case the animal begins to chew the endotracheal tube. It is ideal to position the patient in ventral recumbency.

2. Placement of catheter. With sterile gloves, advance the polypropylene urinary catheter to a predetermined distance to the tracheal bifurcation (measure from larynx to caudal border of the scapula to approximate distance to tracheal bifurcation).

3. Obtain the sample as described in method 1, step 6.

4. Remove the polypropylene catheter.

5. Monitor and recover the patient. Provide supplemental oxygenation through the endotracheal tube as needed. Monitor patient's respiratory effort and signs for distress. Thickened mucus secretions may occlude airway. Suction endotracheal tube with an aspiration catheter, if necessary. Remove endotracheal tube when patient regains swallowing reflex and no longer tolerates the tube in place. Continue to monitor patient until ambulatory.

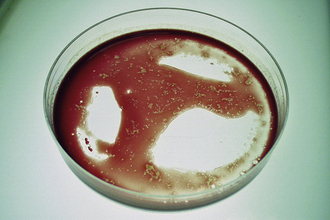

SAMPLE HANDLING

Tracheal lavage samples are commonly submitted for both a culture and cytologic examination. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures are often requested by the clinician. If a reference laboratory is used, check with the laboratory for their protocols on sample handling. They may provide transport media for your samples. If samples are submitted in a syringe, the needle should be sealed with a rubber stopper, the sample refrigerated, and cultured within 12 hours. If smears for cytology are made before shipment, make smears from both the supernatant and sediment after centrifugation. Be sure to make monolayer smears and air-dry. Smears may then be packaged in a protective container for shipment. If an on-site cytology examination is preferred, suitable stains are Romanovsky's or Giemsa-type stains.

CYTOLOGIC SAMPLE INTERPRETATION

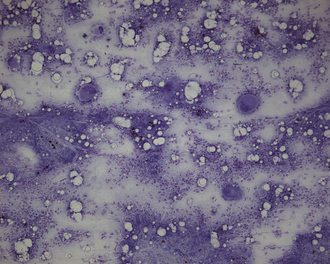

The material obtained from deep transtracheal lavage procedures will include cellular elements normally lining the tracheobronchial tree; cells infiltrated from inflammatory, hemorrhagic, congestive, neoplastic, or other pathologic processes; and background material derived from mucus, proteinaceous exudate, or cellular fragments. Etiologic agents may be observed including bacteria, fungi, and parasites.

ARTHROCENTESIS

Arthrocentesis is the aspiration of fluid from a joint. The disorders involving joints are etiologically diverse, ranging from congenital, developmental, and acquired disorders to various infections and immunologic diseases. Depending on the specific disorder, joint disease may be a primary or secondary symptom. For the veterinarian to establish and differentiate the diagnosis of joint disease in the dog and cat, a synovial fluid analysis is essential.

Indications for a joint fluid analysis include persistent or cyclic fever, especially a fever of unknown origin (FUO). Indications also include patients that have generalized stiffness or limb lameness, especially associated with systemic signs of illness, fever, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, hyperfibrinogenemia, malaise, and anorexia. Arthrocentesis may be indicated in patients with a definite lameness. Palpation of localized pain and/or joint swelling may be detected along with a change in stability or range of motion involving the affected joint or joints.

Contraindications for joint fluid collection include those patients with moderate to severe pyoderma or lick granuloma. The risk is too great for potentially inoculating the joint from the infected skin. Risks and complications include trauma with or without hemorrhage into the joint, especially when degenerative changes involving the joint are present making access difficult, and when patients are uncooperative and are not immobilized. Iatrogenic contamination or inoculation of the joint is a complication prevented with good aseptic techniques.

PROCEDURE: JOINT FLUID COLLECTION OF DISTAL JOINTS IN THE DOG AND CAT

The equipment needed for arthrocentesis is: ¾-inch or 1-inch, 25-gauge needles and 3-ml syringes; 1-inch or 1½-inch, 22-gauge needles and 3-ml syringes; clean microscope slides and coverslips; sterile gloves; clippers; and aseptic surgical preparation supplies.

Patient restraint is essential. Joint fluid can sometimes be obtained from the distal joints without sedation or any type of anesthetic if the patient is not painful. However, sedation or light tranquilization and the use of analgesics are necessary for uncooperative and/or patients experiencing pain.

The patient's preparation includes placing the animal in lateral recumbency. Prepare the sites by clipping the animal's hair and proceeding with an aseptic surgical preparation.

With sterile gloves donned, palpate the joint space to be entered with the index finger. Introduce the needle attached to the syringe. Hold the syringe in such a manner that you can easily aspirate back on the plunger and you do not have to reposition your hands on the syringe. A steady hand is essential to minimize joint trauma and to produce a noncontaminated (bloody) sample (Figure 20-17). A slight negative pressure is applied to the syringe upon entry into the joint. The suction should always be released before withdrawing the needle. This will prevent contamination (blood) from the skin, SQ tissues, and synovium. An adequate sample is often just enough fluid to fill the needle hub.

FIGURE 20-17 Hold the syringe in such a manner that you can easily aspirate back on the plunger and you do not have to reposition your hands. The shown “dart” technique is favorable with many clinicians and technicians.

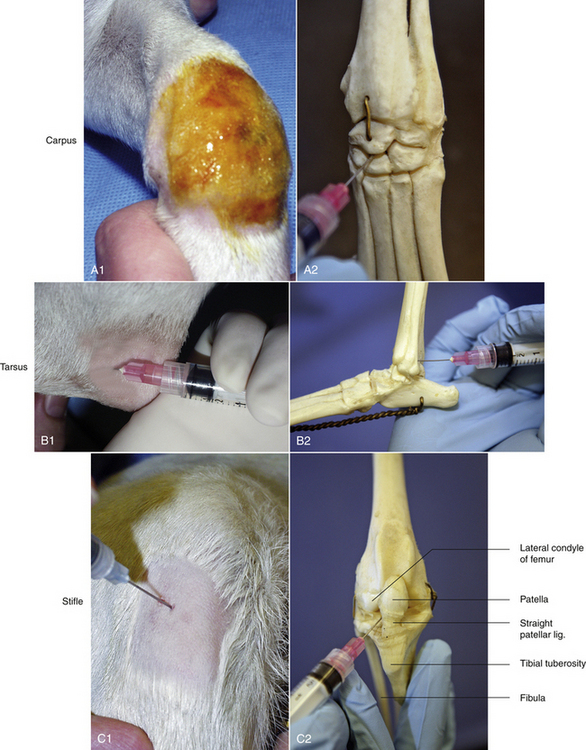

Common sites for arthrocentesis in the dog and cat include the distal joints, including the carpus, tarsus, and stifle (Figure 20-18). Techniques for these sites are as follows:

FIGURE 20-18 The carpus (A1 and A2), tarsus (B1 and B2), and stifle (C1 and C2), are common sites for arthrocentesis in the dog and cat. Illustrations show the skeletal joint anatomy and a patient. The carpus can be approached perpendicular at any intercarpal space; A1 and A2. The tarsus can be approached laterally with the needle directed caudal to lateral malleolus and keeping the syringe and needle parallel with the metatarsal bones; B1 and B2. Reference landmarks for the stifle joint are the patella, straight patellar ligament, tibial tuberosity, and the lateral condyle of the femur (C2).

Carpus: The joint is held in flexion. The needle can be inserted in any palpable intercarpal space. The medial radiocarpal joint is most commonly used. This is to avoid the cephalic vein that courses over the carpal joint. The needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin to avoid the articulating surfaces.

Tarsus: The jock is held in partial flexion: 90 degrees with metatarsals and tibia. The joint may be approached either medially or laterally. During a lateral approach, care must be taken to avoid the caudal branch of the saphenous vein. The needle is inserted just caudal to the lateral malleolus and dorsal to the tibial tarsal bone. The needle is directed under the lateral malleolus where it forms a lip over the fibular tarsal bone. Keep the syringe and needle parallel (flat) with the metatarsal bones, heading in the direction of the animal's toes. The insertion of a ¾-inch, 25-gauge needle is often advanced to its full length before obtaining fluid in a medium- to large size dog.

Stifle: The stifle joint is partially flexed during the procedure. The patella, straight patellar ligament, tibial tuberosity, and the lateral condyle of the femur provide landmarks for tapping the stifle. These landmarks form a triangle that aid in entering the joint space. The needle is inserted just lateral to the straight patellar ligament. The needle is directed medially (approximately 35-degree to 45-degree angle) and slightly upward into the origin of the cruciate ligaments between the femoral condyles. A longer 1-inch to 1½-inch needle is usually necessary for tapping the stifle.

JOINT FLUID ANALYSIS

A single drop of synovial fluid is sufficient for gross and histologic appearance. The synovial joint analysis is complete with an additional drop of synovial fluid for a bacterial culture (aerobic, anaerobic, and Mycoplasma). If samples are submitted to a reference laboratory, synovial fluid can be placed in a small EDTA tube. When synovial fluid is minimal, excess EDTA should be decanted from the EDTA collection tube to minimize a diluting effect.

Gross appearance: A normal synovial fluid sample is a small volume of about 0.05 to 0.3 ml. It is colorless, clear, and viscous. An increased volume in synovial fluid can be observed in both noninflammatory and inflammatory joint diseases. A bloody tap as a result of trauma during the collection procedure can usually be distinguished from hemarthrosis because blood is incompletely mixed with the synovial fluid. Blood can be aspirated from inflamed (septic; acutely traumatized, coagulation defects) joints. A yellow-tinged fluid is a result of previous hemorrhage with release of hemoglobin pigments into the joint fluid (inflammatory, degenerative, and traumatic joint disease). If either red blood cells (RBCs) or white blood cells (WBCs) or both are in excess, an increase in turbidity or lack or clarity is observed. The viscosity can be subjectively evaluated by observing the fluid exiting the needle and onto a microscope slide. A normal joint sample will form a long string between the needle and slide. In addition, the drop on the slide should remain global rather than dispersing over the slide. A thin, runny consistency is a frequent, consistent finding in inflammatory disorders. Occasionally, poor viscosity is observed in degenerative or traumatized joints.

Culture: Aerobic, anaerobic, and Mycoplasma cultures are most often negative in polyarthritis. A negative culture therefore supports a noninfectious inflammatory polyarthritis disorder.

Histologic appearance: Normal values are noted in Box 20-3. Absolute cell counts can be done with a hemocytometer. Often joint fluid samples are small, and cell counts are estimated. Estimated counts are more often practiced in a clinical setting. This can be accomplished by recording the number of nucleated cells per microscopic field and comparing the counts with a peripheral blood smear of known concentration of nucleated blood cells.

1. Blood smear = 6 WBC/high-power field (hpf) from a blood sample containing 18,000 WBC/μl

Synovial fluid smear = 0 to 1 WBC/hpf

Estimated count = 0 to 3000/mm3

The estimated count and zero to an occasional WBC observed suggest a normal joint.

2. Blood smear = 6 WBC/hpf from a blood sample containing 20,000 WBC/μl

The estimated count and frequent appearance of WBCs on the smear suggest a markedly elevated nucleated cell count.

Differential: Mononuclear cells. Normal synovial fluid contains a mixture of small and large mononuclear cells. The absolute number of mononuclear cells varies considerably. Therefore the subclassification and absolute count of mononuclear cells provide limited diagnostic information. Elevations tend to occur with traumatized or degenerative joints, chronically inflamed joints, and joints with osteochondrosis.

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs): They are generally absent or, if present, should account for less than 10% of the nucleated cell count. An increase in the relative (normal cell count) or absolute number of PMNs indicates inflammation of the synovial joint lining. Generally the more severely inflamed joints will contain a greater concentration of WBCs with a greater percentage of PMNs.

BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

Bone marrow aspiration is performed to evaluate the cells in the bone marrow. Bone marrow aspirations for cytology or a core biopsy are safe, easily performed techniques that may yield valuable information regarding the cause or pathogenesis of many disease processes.

Indications for bone marrow aspiration include patients with nonresponsive anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia without suspicion of infection (i.e., sepsis), pancytopenia, suspected hematopoietic malignancies (i.e., myelogenous leukemia), polycythemia, and inappropriate RBC response, such as the presence of nucleated RBCs in peripheral blood without the presence of reticulocytes or without anemia. Patients that are suspected to have neoplasia, such as lymphoma or multiple myeloma, undergo bone marrow aspiration procedures. Clinical staging of lymphoma or mast cell tumors are also indications.

Contraindications include patients with clotting factor abnormalities and patients with severe thrombocytopenia. This is a relative contraindication and may require the administration of plasma or platelet-rich plasma before the procedure.

Complications include infection at the site if aseptic technique is not maintained, especially in leukopenic patients; damage to soft tissue structures; and hematoma formation if a coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia is present.

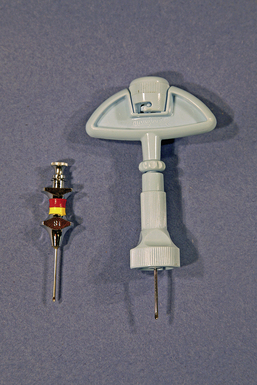

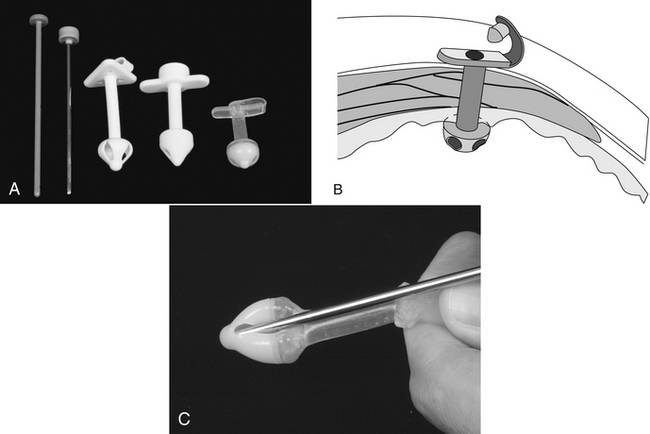

The supplies needed to perform a bone marrow aspiration procedure include a bone marrow aspiration needle. The needle may be purchased from a variety of manufacturers, but common types used in a small animal practice are 18-gauge, 1-inch Rosenthal needles with a matched stylet and 16-gauge,  15⁄16-inch Illinois needles with a matched stylet and depth stop (Figure 20-19). Other equipment required is: #11 scalpel blade, 12- or 20-ml syringe; sterile gloves; sterile drape; local anesthetic, such as 2% lidocaine in a syringe with a needle; clean glass slides; and EDTA collection tube. A complete blood count (CBC) with reticulocyte count is done within 24 hours before or after the aspirate so the peripheral and marrow cell populations can be composed. The bone marrow aspiration procedure is a very painful procedure. Heavy sedation with good analgesic agents in combination with a local infiltrate anesthetic or general anesthetic is warranted.

15⁄16-inch Illinois needles with a matched stylet and depth stop (Figure 20-19). Other equipment required is: #11 scalpel blade, 12- or 20-ml syringe; sterile gloves; sterile drape; local anesthetic, such as 2% lidocaine in a syringe with a needle; clean glass slides; and EDTA collection tube. A complete blood count (CBC) with reticulocyte count is done within 24 hours before or after the aspirate so the peripheral and marrow cell populations can be composed. The bone marrow aspiration procedure is a very painful procedure. Heavy sedation with good analgesic agents in combination with a local infiltrate anesthetic or general anesthetic is warranted.

FIGURE 20-19 Bone marrow aspiration needles: 18-gauge stainless steel Rosenthal needle; 16-gauge Illinois-style needle with depth stop.

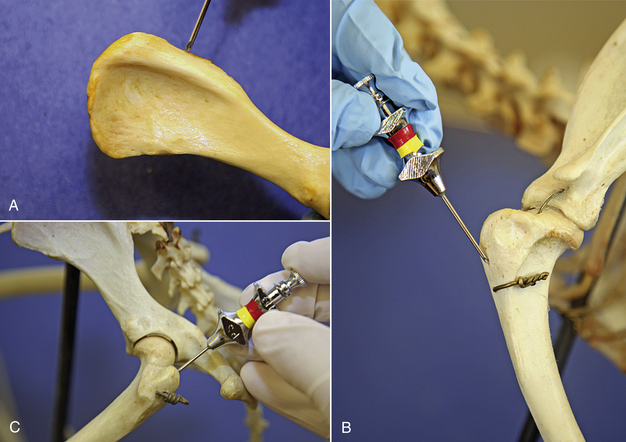

Bone marrow aspirations are most commonly performed in the ilium, humerus, and femur in small animal patients (Figure 20-20). The patient's size, age, and conformation determine which site is used. It is important to remember that aged patients’ bone marrow is less active in long bones than flat bones, therefore in geriatric patients, a higher success rate for a cellular diagnostic sample is sought in a flat bone, such as the ilium. Bone marrow aspiration procedures are performed with strict aseptic technique. The hair over the site is clipped, and the skin is surgically prepared. Sterile gloves are worn by the person performing the aspiration. The patient's positioning for the dorsal iliac crest is sternal or lateral recumbency; lateral recumbency for the humeral head; and lateral recumbency for the intratrochanteric fossa of the femur.

FIGURE 20-20 Common sites for bone marrow aspiration in the dog and cat patient: A, wing of the ilium, B, the greater tubercle of the proximal humerus, and C, the trochanteric fossa of the femur.

ILIAC BONE MARROW ASPIRATION

The patient is placed in sternal or lateral recumbency with its legs drawn forward to better palpate the wings of the ilium. The hair is clipped from the procedure site, and the skin is prepared for aseptic surgery. Local infiltration of 2% lidocaine is done by injecting into the skin, SQ tissue, and periosteum of the bone. A stab relief incision is made into the skin over the iliac crest with a #11 scalpel blade. The bone marrow needle's stylet is inspected, confirming that the stylet is perfectly occluding the distal tip and in place or the needle will become plugged with cortical bone. If a Rosenthal needle style is used, the operator must hold the needle in such a fashion that the stylet does not back out by placing counter pressure on the stylet with an index finger or palm of the hand. One hand is placed on the ilium to stabilize it. The bone marrow needle with its stylet in place is advanced through the skin incision and onto the bone. The needle is advanced into the bone by rotary motion, twisting the wrist only in a clockwise, counterclockwise motion. The goal is to keep a single axis and to avoid wobbling of the needle. This is accomplished by keeping the elbow immobilized and using wrist action only. Considerable force is typically required. The needle is advanced into the bone 1 to 1.5 cm or until the needle is well seated.

Once the needle is well seated and stabilized in the bone, the stylet is removed from the needle and placed on a sterile field. A 12- or 20-ml syringe is firmly attached to the bone marrow needle, and negative pressure is applied to the syringe plunger. The aspiration should be very quick and negative pressure immediately discontinued once 0.1 to 1.0 ml of sample is obtained. The actual aspiration of the marrow fluid is the most painful for the patient, and the conscious, sedated patients may show signs of discomfort. The restrainers of unanesthetized patients should be prepared for the patient to react with a yelp, cry, or movement.