Chapter 15 Musculo-Skeletal System

Bone

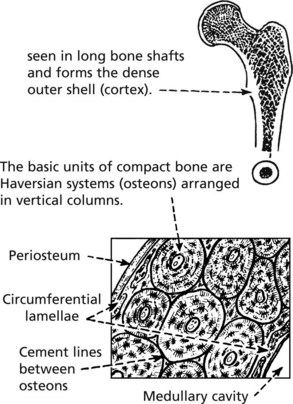

There are two different forms of normal adult bone, both with a lamellar (layered) structure.

Note: Cancellous bone comprises 20% of bone mass but 80% of bone turnover due to its large surface area

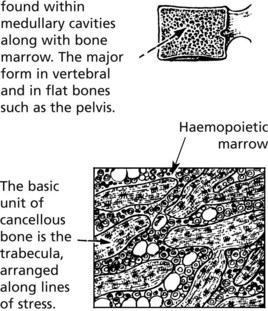

WOVEN BONE (non-lamellar), is a primitive form laid down in fetal development. In adult life, this type is seen in bone repair and bone-forming tumours. It can be remodelled to be replaced by lamellar bone.

Bone and Calcium

Bone acts as a reservoir for calcium, which is maintained within a narrow range (2.1–2.6 mmol/l). Hypocalcaemia stimulates parathyroids to produce parathyroid hormone (PTH) which promotes bone resorption, calcium absorption from the gut and reabsorption from the kidney. As the serum calcium rises, PTH production is switched off.

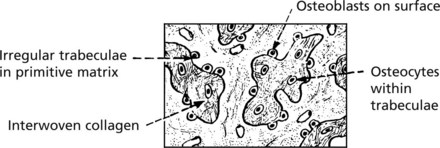

Bone Turnover

Osteoporosis

OSTEOPOROSIS is the commonest disorder of bone. It is defined as a systemic disease characterised by:

A patient is said to have osteoporosis if bone mineral density >2.5 standard deviations below the mean of normal young subjects.

Clinical effects: – osteoporosis is a disease predominantly of post-menopausal females, but men are also affected.

Note: In osteoporosis, the routine serum biochemical tests – particularly the calcium levels – are within the normal range.

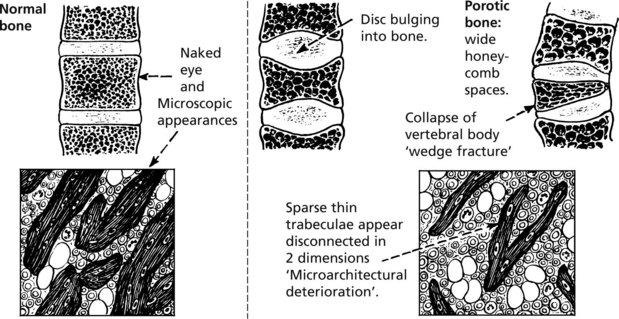

Pathology: The changes in the vertebral bodies are shown.

Aetiology

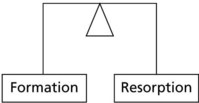

In normal bone the dynamic processes of formation and resorption are in balance.

In osteoporosis the balance is upset by

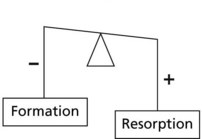

Bone mass decreases with age in both sexes: in old age, osteoblastic activity falls.

PEAK BONE MASS is important – a high initial figure makes osteoporosis less likely. This depends on factors including:

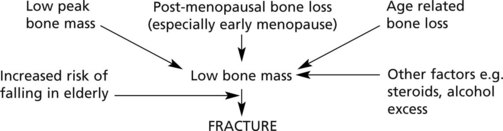

The aetiology can be summarised as follows:

Localised osteoporosis is commonly due to disuse and is seen as a complication of other disorders, e.g. local immobilisation following fracture; limb paralysis and adjacent to severe joint disease with limitation of movement.

Osteomalacia and Rickets

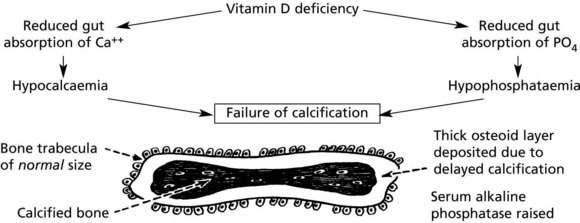

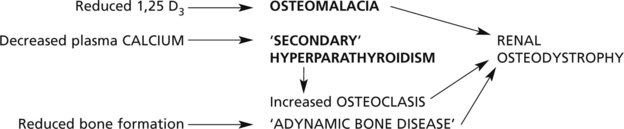

Osteomalacia and rickets are disorders of bone due to failure of mineralisation of newly formed osteoid, caused by vitamin D deficiency in almost all cases. The poorly calcified bones are soft causing deformity or fracture.

Osteomalacia occurs in adult life and affects the osteoid which is being continually laid down in the normal remodelling of bone.

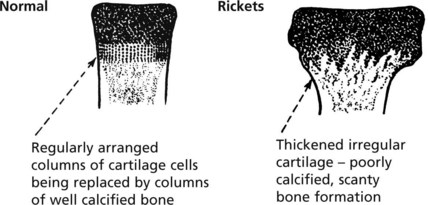

Rickets affects the growing child. As well as deformity and fractures, there is disturbance of growth plates. X-ray may show linear partial fractures of long bones which have failed to calcify (Looser’s zones).

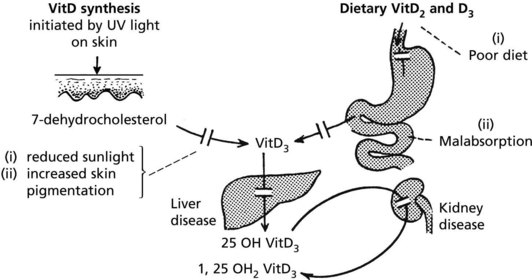

The following simplified diagrams indicate the causes of vitamin D deficiency and its effects on bone.

Metabolic Bone Disease

In rickets the growing ends of long bones are abnormal.

This results in stunting of growth and bowing of the lower limbs.

In females permanent deformities of the pelvis can cause serious difficulty during childbirth.

Enlargement of costochondral junctions gives the so-called rickety rosary

Hyperparathyroidism (see P.642)

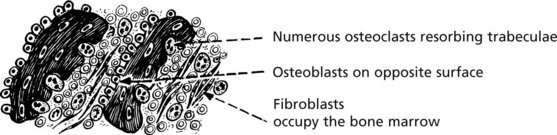

Bone changes may be seen in hyperparathyroidism, especially when severe or long-standing. There is increased bone resorption due to PTH-induced osteoclastic activity. Due to ‘coupling’, osteoblastic activity is also increased but the net effect is bone loss.

These changes affect all bones. There may be marked loss of bone with numerous osteoclasts and haemosidern pigment – the so-called ‘brown tumour of hyperparathyroidism’, which can mimic giant cell tumour.

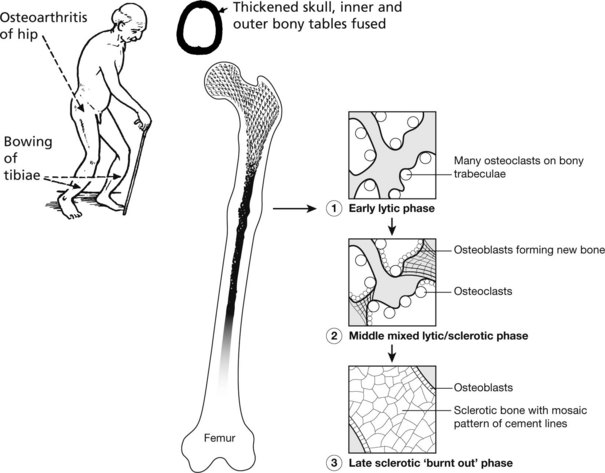

Paget’s Disease of Bone

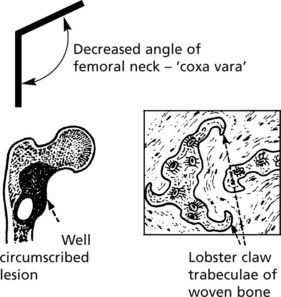

This disease of unknown aetiology usually presents after the age of 50 years and is more common in males. It is fairly common (3% of autopsies), but only in its more severe forms are there clinical symptoms. The disorder is focal: the bones particularly affected are the pelvis, vertebrae, skull and lower limbs. It has been suggested that virus infection (e.g. measles, distemper) of osteoclasts is responsible. Genetic factors are important.

To begin with, there is a localised increase in osteoclastic activity causing bone resorption; soon there is a marked osteoblastic reaction with bone resorption and deposition proceeding chaotically, so that irregular bone trabeculae with mosaic cement lines are formed. The bone may be thickened, but its structure is defective and weak. Biochemical changes reflect the cellular activity at trabecular level: Alkaline phosphatase ↑(osteoblastic); urinary hydroxyproline ↑(collagen destruction).

Often asymptomatic, the main effects are:

The use of bisphosphonates offers effective therapy in many cases.

Bone – Miscellaneous

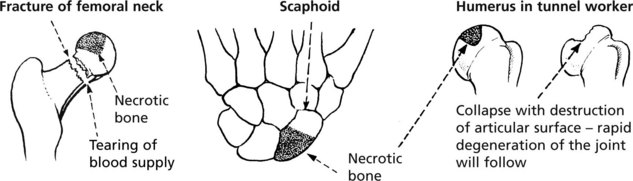

Osteonecrosis (Avascular Necrosis)

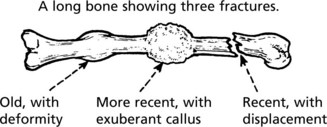

Interruption of its blood supply causes bone to undergo necrosis. This tends to occur with fractures at sites where the vascular supply is damaged. Fractures of the femoral neck and scaphoid bone are good examples.

Non traumatic causes include corticosteroid therapy, alcoholism, sickle cell anaemia, Gaucher’s disease and historically in decompression in those working in increased atmospheric pressure (caisson disease).

Bone necrosis occuring at an articular surface often leads to degenerative arthritis.

Note: These areas of necrotic bone may appear radiodense due to disuse osteoporosis of the adjacent living bone.

In children and adolescents osteonecrosis occurs at several epiphyseal sites probably due to trauma). The commonest is Perthes’ disease in which necrosis of one or both femoral heads occurs in children aged 4–10 years (male: female = 5:1).

Fibrous Dysplasia of Bone

This disorder may affect one (monostotic) or several (polyostotic) bones. On histology, well demarcated fibrous tissue containing small abnormal woven bone trabeculae is seen. Somatic mutations of the GNAS1 gene which encodes the α subunit of a stimulatory G-protein are responsible. Whether the disease is polyostotic or monostotic depends on the stage of development of the embryo when the mutation occurs, a state known as mosaicism.

Infections of Bone

Acute Osteomyelitis

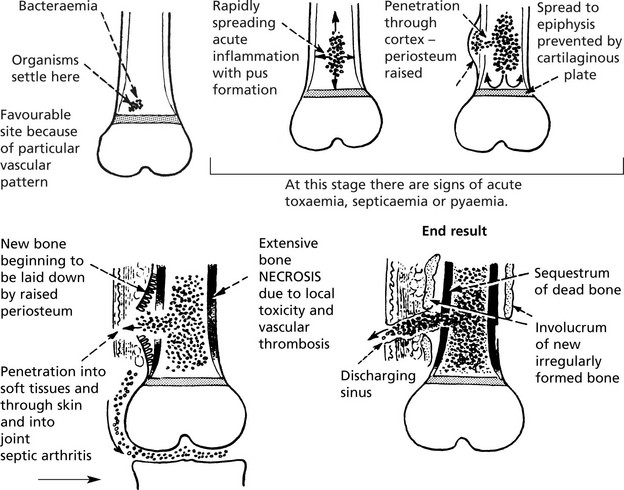

Classically caused by Staphylococcus aureus. This affects the metaphyses of long bones in children. Nowadays the incidence has been greatly reduced and the use of antibiotics aborts the development of the disease. The bacteria are blood borne and settle in the cancellous bone of the metaphysis. The effects are dramatic and rapidly progressive.

The presence of necrotic bone ensures that the inflammation continues.

The late complications are chronic osteomyelitis, disturbance of bone growth, amyloid disease may occur and occasionally squamous carcinoma arises in a sinus.

Other pyogenic bacteria can cause osteitis – the salmonella group (esp. S. typhi) and brucella, the latter often causing a low grade osteitis of the spine.

With inadequate antibiotic treatment, acute inflammatory processes may be converted into low grade osteitis. Staphylococcal infection of the spine may present in adults in this way.

Tuberculosis

The incidence of bone and joint infection parallels that of the more common pulmonary infection. It is therefore low in developed countries but still significant elsewhere, and has risen in association with HIV infection.

The spine and growing ends of long bones including the epiphyses are affected by blood borne spread and the infection spreads to the adjacent joints.

Bone is destroyed and replaced by granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis. Spinal infection spreads into adjacent tissues and leads to ‘cold abscess’ formation.

Although the progress is much less rapid than in acute osteomyelitis, without adequate treatment serious damage to bones and joints occurs.

Developmental Abnormalities

Generalised abnormalities are rare and usually inherited.

A mutation of the fibroblast growth factor receptor gene (FGFR3) is responsible, which causes constitutive activation and inhibits cartilage growth. Although inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, 80% of cases result from new mutations.

The basic defect is in the osteoblasts which fail to synthesise collagen properly, due to mutations affecting the Type I collagen genes on chromosomes 7 and 17. The severity of the disorder depends on the type of mutation, some cases being lethal in utero.

Bone marrow transplantation provides functioning osteoclasts and reverses the skeletal abnormalities.

Cysts of Bone

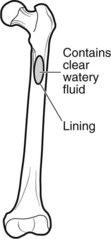

Simple bone cysts (unicameral-single chamber) have a thin fibrous lining and occur in the proximal humeral and femoral metaphyses of children. They often present with fracture.

Aneurysmal bone cysts (expanding blood-filled cysts in adolescents) are eccentric expanding blood-filled cysts presenting with swelling, pain or fracture.

These true cysts should not be confused with lytic lesions which appear cystic on X-ray.

Tumours in Bone

Primary bone tumours are rare. There are both benign and malignant forms, examples of which follow. In contrast, metastatic tumours and myeloma are common.

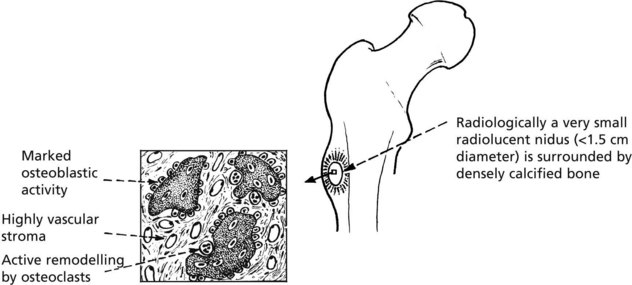

Osteoid Osteoma

This uncommon benign tumour has a striking clinical presentation and a distinctive pathology.

Clinical: Classically, an adolescent complains of well localised, increasingly severe bone pain. Aspirin and non steroidals give relief.

Pathological: The essential lesion is a small focus (nidus) of newly formed irregular trabeculae of osteoid or poorly calcified woven bone in a highly vascular stroma.

Note: Reaction in surrounding bone; sclerosis of adjacent cortex and periosteal bone thickening.

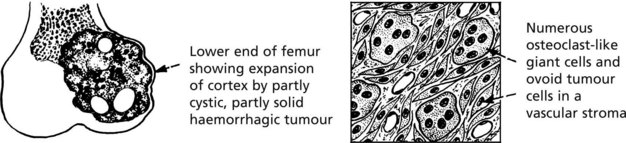

Giant Cell Tumour (Osteoclastoma)

This uncommon tumour presents in adult life (age 20–40 years), at the end of a long bone, especially adjacent to the knee. The tumour destroys bone and the cortex gradually expands, becoming egg-shell thin. Pathological fracture is common.

The histology is characteristic:

Behaviour: Almost all giant cell tumours are benign. Most are cured by thorough removal: approximately 20% recur: well under 5% become malignant and metastasise to the lungs.

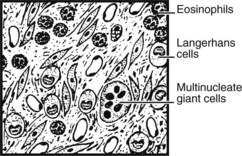

EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMA (at the benign end of the spectrum of Langerhans histiocytosis) usually presents as single osteolytic radiolucent lesions of bone in children. Vertebral collapse and pathological fractures are sometimes seen.

Malignant Tumours

Primary malignant tumours of bone are not common, but they are important as many arise in young people and are highly malignant. Some arise in older people with pre-existing bone disorders, e.g. Paget’s disease, previous irradiation.

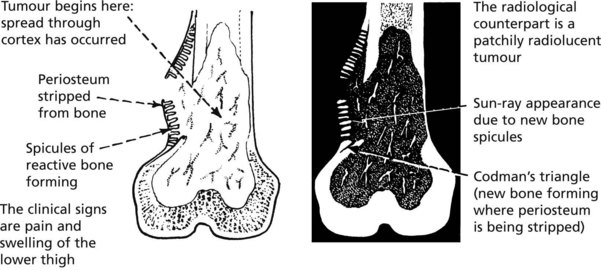

Osteosarcoma

This highly malignant tumour is the commonest primary malignant tumour of bone. It affects two distinct age groups and there is a preponderance of males over females.

| Young age group – majority of cases (10–25 years) | Elderly subjects (over 60 yrs.) |

|---|---|

| The tumour usually arises near the end of a limb long bone (particularly around the knee). | In 50% of this group, Paget’s disease is associated. Long bones, vertebrae and pelvis are often affected, and tumours may be multicentric in origin. |

The ‘classic’ tumour in an adolescent begins in the metaphysis of the medullary cavity. Most patients complain of bone pain and when the tumour penetrates the cortex there may be a soft-tissue swelling.

Note: At this stage lung metastases may be present.

Histologically, varying amounts of osteoid, woven bone and sometimes islands of primitive cartilage are seen. The tumour cells are pleomorphic and mitotically active. With modern chemotherapy 50–60% of patients survive for 5 years.

Chondrosarcoma

This shows a much slower growth pattern and affects the age group 40–70 years. Multiple enchondromatosis pre-exists in a small number of cases. The tumours arise particularly in the limb girdles and proximal long bones and consist of lobules of cartilage. Progressive local extension is usual. Metastases, usually to the lung, are rare.

Ewing’s Sarcoma

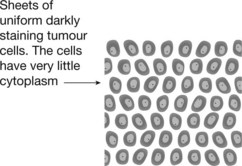

This rare malignant tumour affects the young (age 5–20 years) and arises in long bones, pelvis, ribs and scapulae. It is very aggressive, metastasising early to lungs and other bones.

The tumour cells are small and uniform. Fever and an elevated white count are common and may mimic osteomyelitis. The histological appearances may mimic lymphoma.

Ewing’s sarcoma is a primitive neuro-ectodermal tumour associated with translocation and fusion of genes, typically the EWS and Fli-1 genes, on chromosomes 11 and 22. With chemotherapy, survival is similar to that of osteosarcoma.

Secondary Tumours in Bone

this is by far the most common type of tumour in bone.

Tumours which show a predilection for spread to bone are carcinoma of the prostate, breast, lung, kidney and thyroid. Metastases are usually multiple. The incidence of bone secondaries especially in the spine is very high when these tumours become widespread. Occasionally latent renal and thyroid cancers present as a single bony metastasis with pathological fracture.

Metastases are usually osteolytic with extensive destruction of bone. In a minority of cases, osteoblastic activity is stimulated by the presence of the tumour so that dense reactive bone is formed. Osteosclerotic secondaries of this type are seen particularly in cancers of the prostate and breast.

Joint Diseases

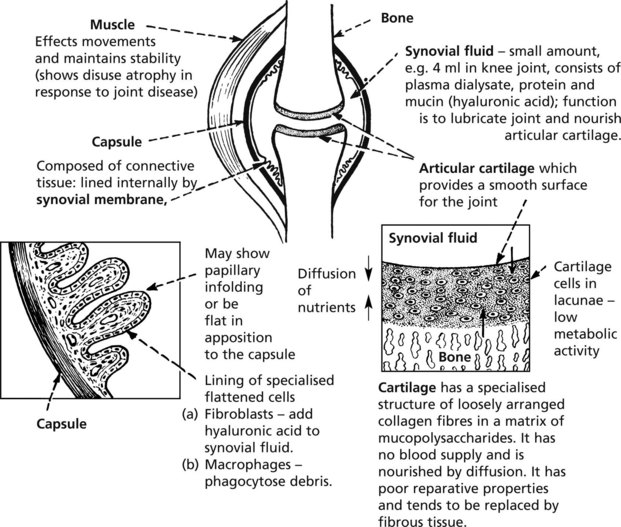

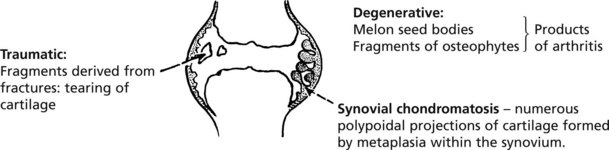

The diagram illustrates the structure of a synovial joint.

The two most common joint diseases illustrate how individual components of a joint may be initially affected:

As the diseases progress, other secondary effects are added and may obscure the basic pathology.

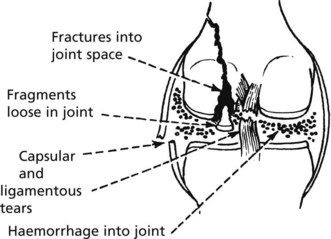

Joint Trauma

Trauma is very variable in its severity and effects.

At one end of the scale a single incident of ‘sprain’ or ‘strain’ involves only minor soft tissue damage with minimal associated haemorrhage – in these circumstances the healing capacity of joints is rapid and complete.

With mild degrees of trauma, particularly if repeated, the synovial membrane shows nonspecific reactive changes which include hyperaemia and a mild chronic inflammatory cellular infiltrate. There is often a joint effusion.

Serious damage to joints include:

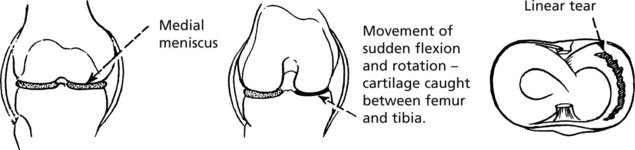

The medial meniscus of the knee is susceptible to tears:

Locking of the joint and effusion are common.

Apart from damage directly attributable to trauma, the most important consequence is an increased risk of osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Osteoarthritis (OA)

This is the commonest disorder of joints and, by causing pain and stiffness, is the commonest cause of chronic disability after middle age. The basic pathology is degenerative and is similar to the changes of ageing.

The disorder is divided into two main groups. In both types of osteoarthritis the basic pathological processes are the same.

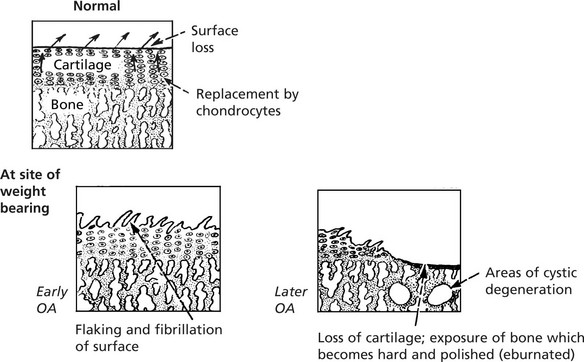

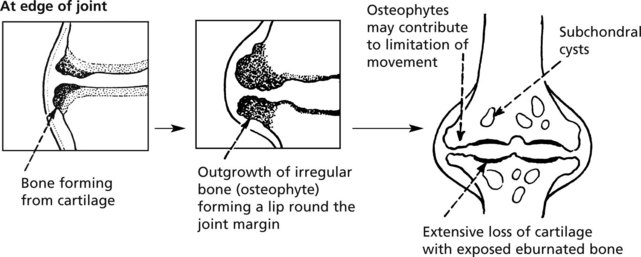

The integrity of the articular cartilage represents a balance between ‘wear and tear’ losses and replacement by chondrocytes of the specialised matrix.

The earliest change in ageing and OA is in the chemical composition of the matrix which becomes softer. This is followed by progressive characteristic morphological changes.

The synovial membrane may show mild, non-specific inflammation and effusion may occur but these changes are secondary.

Distribution: secondary OA often affects a single predisposed joint.

In primary OA, the larger weight bearing joints and the spine in particular are susceptible, but interphalangeal joints bear osteophytic outgrowths (Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes). Osteoarthritis is the main indication for hip and knee replacement surgery.

A particularly severe form (Charcot’s joint) is seen when the nerve supply to a joint is defective – neuropathic arthropathy.

Gout

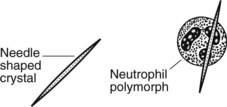

Patients with gout develop acute arthritis often of the great toe. Uric acid is produced in purine (DNA) breakdown. In gout, there is hyperuricaemia (serum uric acid >7 mg/dl). Periodically, urate crystals are deposited within the affected joint, at first in the articular cartilage, but chronically in the adjacent bone and soft tissues forming masses known as tophi. Joint aspiration shows characteristic appearances.

PSEUDO-GOUT. In this condition of the elderly, rhomboid crystals of calcium pyrophosphate are deposited in the joint, evoking a similar inflammatory reaction. Larger joints such as the knee tend to be affected; chronic degenerative arthritis often supervenes or co-exists. The radiological appearances are known as chondrocalcinosis.

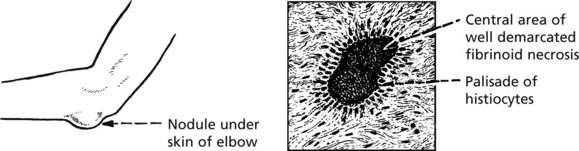

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

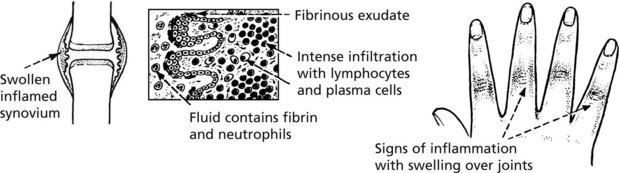

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common systemic disease (1–3% of population in Europe). The most affected tissue is the synovial membrane. The typical clinical course is insidious in its onset and progression; in a minority, the onset is acute and the progress rapid. Frequently there are remissions and exacerbations.

| Incidence: female > male 3:1 | Age of onset: usually 35–55 years, but also in childhood – usually severe. |

Typically, affecting multiple joints symmetrically, the joints of the hands and feet and the knee joints are affected; there may be involvement of the spine.

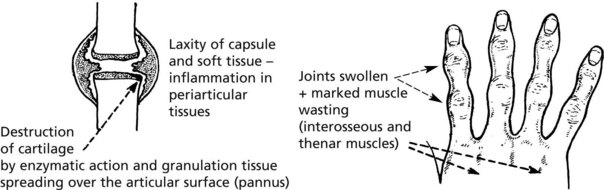

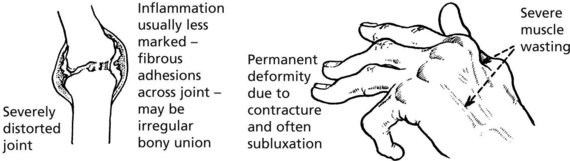

Pathology: The synovial membrane shows chronic inflammation.

Late

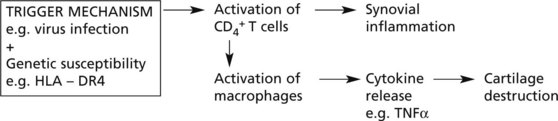

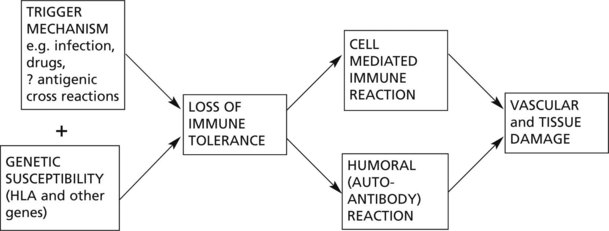

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease, with no single provoking factor. A possible hypothesis is:

Joint destruction is due to a complex cascade of cytokines, inflammatory cell interaction, and alteration of activity of chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteoclasts.

Modern therapy directed against TNFα suppresses disease activity and stops joint destruction.

Rheumatoid Factors

These are antibodies, mainly of IgM and IgG class, which are directed against the patient’s IgG, and may form immune complexes which may contribute to the joint inflammation. Patients in whom these autoantibodies can be found in the serum are described as seropositive. Around 85% of RA patients are seropositive.

The systemic nature of the disease is illustrated by inflammatory processes affecting the connective tissues at other sites.

Sero-Negative Arthritis

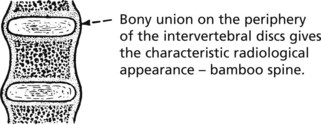

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an arthritis affecting particularly the sacroiliac, costovertebral and vertebral joints, but peripheral arthritis is also seen.

| Incidence: 0.05% of population male:female; 3:1. | Age of onset: Young adults progressing into middle age. Rheumatoid factor negative. |

The disorder is, like RA, an active chronic arthritis, but differs in that it may cause osseous ankylosis (bony union), so that no movement of the affected joints is possible.

Aortitis leading to aortic incompetence and uveitis may be seen.

Psoriatic arthritis affects the axial and peripheral joints. Typically the distal interphalangeal joints are involved and the adjacent nails are affected.

Reiter’s syndrome: This is a syndrome of polyarthritis, urethritis and uveitis following infections, e.g. chlamydia, yersinia and salmonella. The detailed mechanisms are unclear.

HLA association. Ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and Reiter’s syndrome are associated with HLA-B27 (>95% in AS). Genetic susceptibility is an important factor predisposing to the arthritis.

No such association with HLA-B27 is evident with RA, which however shows an association with HLA-DR4, twice that of the general population.

| OSTEOARTHRITIS | RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of disorder | Degenerative | Inflammatory |

| Site of initial damage | Articular cartilage | Synovial membrane |

| Age | Late middle age + | 3rd decade (any age) |

| Joints affected | Large weight bearing often single, pre-existing local factors in some cases | Small joints of hands and feet, multiple |

| Systemic disease | None ESR – normal Rheumatoid factor – absent |

++ ESR ↑ Rheumatoid factor positive Secondary anaemia |

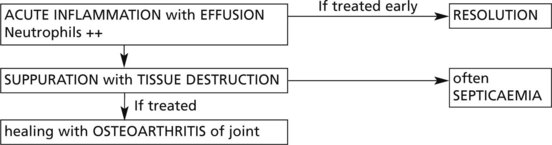

Infections of Joints

In Western countries the incidence is low: a few cases arise complicating reactivated pulmonary tuberculosis in the elderly. If untreated, there is a low grade chronic inflammation with effusion and progressive destruction of tissues.

The diagnosis requires culture of joint fluid and/or biopsy when the typical histology of tuberculosis is seen.

Joint and Soft Tissues – Miscellaneous

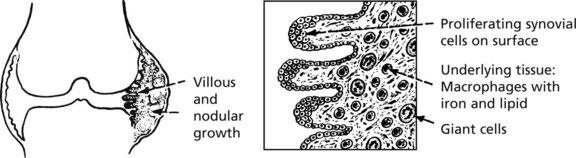

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS) (Tenosynovial Giant Cell Tumour)

This may affect any synovial tissue, but the knee and hip joints are most commonly involved.

There is a strong male predominance (age 20–50). The synovial membrane shows proliferation of brown pigmented large villi or rounded nodules.

It is now thought to be neoplastic but to all intents it never metastasises.

The so-called benign giant cell tumour of tendon sheath is now considered to be a solitary variant of PVNS.

Similar but well-defined nodules are common in the fingers and toes.

Para-Articular Tissues – Miscellaneous

Bursae

These are synovial-lined spaces usually overlying bony prominences, e.g. the olecranon and patella, and often connected with adjacent joint spaces. They may become inflamed (bursitis).

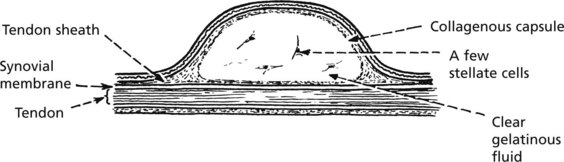

Ganglion

This is a swelling which forms in relation to joint synovium or more usually, tendon sheath due to myxoid degeneration. It is not lined by synovium. Ganglia are classically seen around the wrist.

This type of myxoid cystic degeneration may occur at other less prominent sites, e.g. within the cartilagenous menisci of the knee.

Dupuytren’s Contracture. See page 124.

Collagen Diseases

This term describes a group of multisystem diseases, many autoimmune in origin.

The group includes rheumatoid arthritis (RA); systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); systemic sclerosis; polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and dermatomyositis.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

SLE is a chronic relapsing and resulting disease characterized by damage to multiple organs but especially the skin, joints, kidneys and central nervous system. It is much commoner in females.

SLE is an autoimmune disorder. There are antibodies directed against cellular constituents, e.g. antinuclear, anti-DNA. These autoantibodies damage tissue by a type III hypersensitivity reaction (p.102).

Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma)

This is a rare, slowly progressive disease in which there is gradual fibrosis of various organs including the skin (face and hands), gastrointestinal tract, heart and lungs. It is associated with Raynaud’s disease. The basic abnormality is in the small blood vessels, which show sclerosis with intimal thickening. The change is associated with fibrosis of the surrounding tissues. Auto-antibodies, typically against nuclear components, are often found.

In collagen diseases, the basic mechanisms are inflammatory and are mediated by autoimmune processes. The inflammatory damage is very variable in its severity, its site of predilection and even its local effects. Multiple factors, of which inherited susceptibility and resistance are important, are involved. The following diagram illustrates the basic mechanisms.

Skeletal Muscle

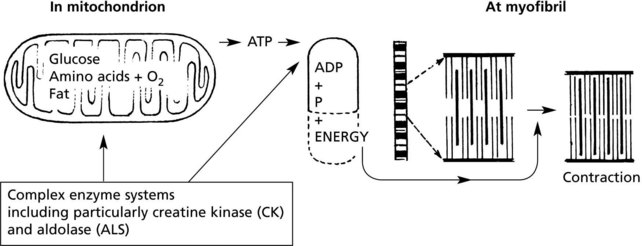

Muscle Contraction

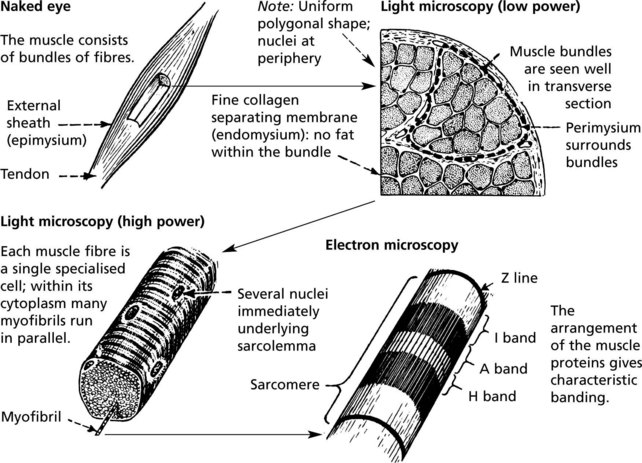

The basic mechanism is as follows:

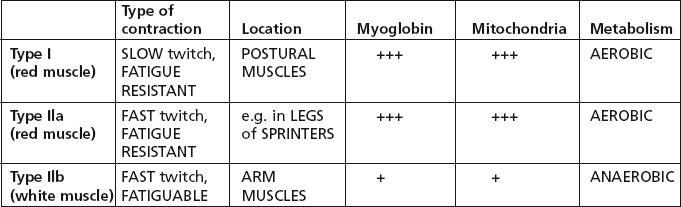

There are 3 types of muscle fibre, related to differences in functional activity.

Note: Most muscles are a mixture of the 3 fibre types, but the proportion varies according to the function of the muscle.

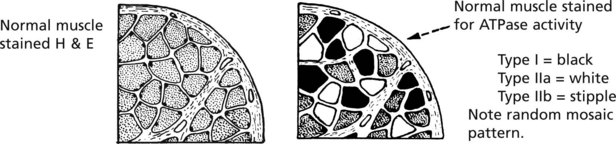

In section, the three fibre types are identified by their ATPase activity.

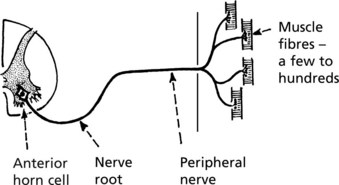

It is of interest that the muscle fibre function is not intrinsic but is conditioned by its type of nerve supply: any single anterior horn cell innervates fibres of only one type.

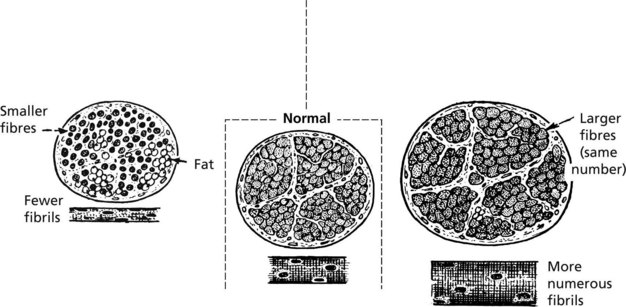

Atrophy And Hypertrophy

Generalised disuse atrophy occurs as a result of prolonged immobilisation in bed. Local atrophy follows immobilisation due to joint disease or after bone fractures.

Hypertrophy of muscle tissue in response to increased work load is well seen in athletes.

Note: Atrophy may be partially masked by increased fat in the septal tissues.

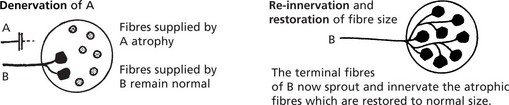

Neurogenic Atrophy

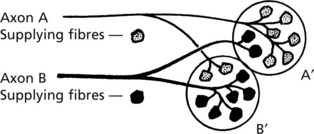

This form of atrophy is seen when the nerve supply is damaged. The distribution of nerve fibres within the muscle is important and is represented diagrammatically in respect of two motor units: A and B.

Note that while A and B respectively innervate the majority of fibres in bundles A′ and B′, there is overlap between bundles. Since many axons supply a muscle the overlap is considerable.

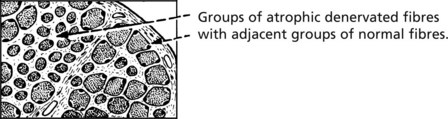

Apart from complete traumatic section of a peripheral nerve, it is unusual for all motor fibres to a muscle to be destroyed. Both the basic pattern of innervation and the variations in nerve fibre damage are reflected in the histological appearances in the denervated muscle.

Myasthenia Gravis

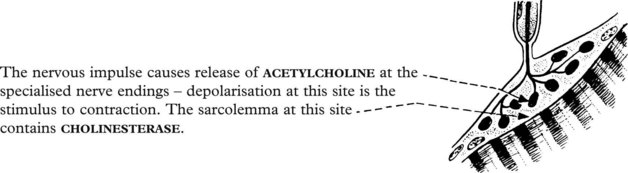

The motor end-plate is the specialised neuromuscular junction situated at the middle of each muscle fibre. The nervous impulse causes release of acetylcholine at the specialised nerve endings – depolarisation at this site is the stimulus to contraction. The sarcolemma at this site contains cholinesterase.

In myasthenia gravis young females are most affected with muscle weakness and early fatigue of the ocular and head and neck muscles particularly.

Antibodies to acetylcholine receptors are present in 90% of cases, blocking the effect of acetylcholine at the motor end plate.

There is a strong association with thymic abnormalities. In young women this is usually thymic germinal centre hyperplasia: in middle aged males a thymoma may be present.

Muscle Damage

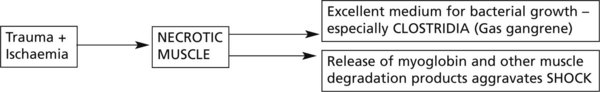

Trauma and ischaemia may combine to cause necrosis of a mass of muscle and the effects may be serious.

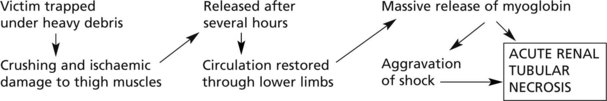

The latter situation is well exemplified in the CRUSH SYNDROME – classically seen in building collapse.

Repair of Muscle Damage

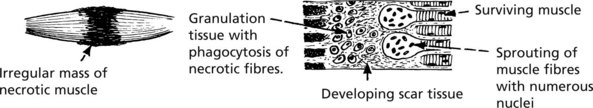

The inflammatory response is followed by organisation with removal of the dead muscle. There are two possible results:

Pyogenic infections of muscle are uncommon but abscess formation may follow intramuscular injections.

Muscular Dystrophy

Muscular dystrophies are inherited diseases, causing muscle damage and weakness.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

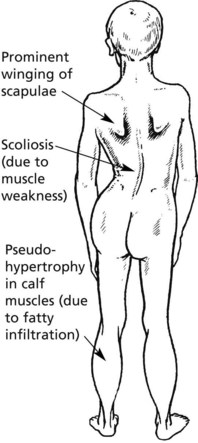

This is the commonest and most serious form.

Clinical features: Muscle weakness in early childhood; typically wheelchair-bound by 12 years of age and death by late teens or early twenties.

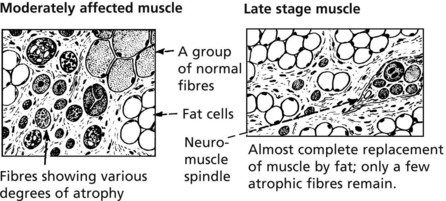

Pathology: The main features are

In time, fibres are atrophic and there is fibrosis and fatty replacement.

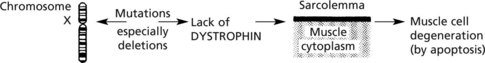

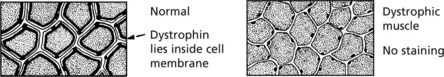

Aetiology: This is an X-linked recessive disease occurring almost exclusively in boys. The dystrophin gene lies on the short arm of chromosome X.

Biopsy in early stages shows a lack of dystrophin using immuno-staining (anti-dystrophin antibodies).

Genetic screening for mutations of the dystrophin gene is now available.

Becker type muscular dystrophy is a milder form caused by mutation in the dystrophin gene resulting in diminished levels of the protein.

Other muscular dystrophies include the facio-scapulohumoral, limb girdle and myotonic dystrophy forms.

Inherited Myopathies

Specific Metabolic Defects

There is a group of genetic myopathies with specific biochemical or morphological abnormalities.

In some, the inborn error of metabolism is generalised and includes muscle; in others it is confined to the muscle fibre. Some examples will be given:

| (1) Glycogen storage | (2) Lipid metabolism | (3) Periodic paralysis |

| Type 2 (Pompe) – deficiency of acid maltase Type 5 (McArdle) – muscle phosphorylase Type 7 – phosphofructokinase (PFK) |

Defect in free fatty acid transport into and utilisation within fibre. | Associated with hypo-and hyperkalaemia – the muscle defect is a vacuolar degeneration of the sarcolemma |

| (4) Morphological abnormalities | ||

| (a) Mitochondrial | (b) Others | |

| Large or increased numbers of mitochondria – abnormal oxidative processes | (i) Central core myopathy  |

(iii) Centronuclear myopathy  |

(ii) Rod body myopathy (nemaline)  |

(iv) Disproportion of fibre types I and II | |

These myopathies vary in age of onset, clinical presentation and prognosis.

A further rare but interesting autosomal dominant genetic abnormality of muscle is malignant hyperpyrexia. In this condition the administration of a general anaesthetic precipitates acute muscle damage. Clinically, there is very high fever, muscle stiffness, cyanosis and acidosis very often resulting in death.

Acquired Myopathies

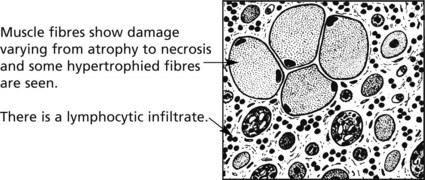

Inflammatory myopathies – polymyositis and dermatomyositis – are two similar inflammatory disorders of muscle.

POLYMYOSITIS – occurs in both sexes and at any age, but especially in middle age. It is characterised by muscle pain and weakness - especially of proximal muscle groups. Progress is variable – deterioration may be rapid or slow.

DERMATOMYOSITIS – has similar muscle changes and also skin lesions often on the face and hands. In adults, dermatomyositis may herald malignancy – often bronchial carcinoma – and there is often evidence of other connective tissue diseases e.g. rheumatoid arthritis.

Other Myopathies

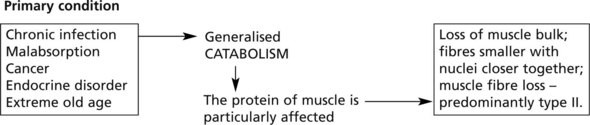

In any wasting disease, loss of muscle with weakness is seen.

Myopathy is seen in acromegaly, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperaldosteronism (due to hypokalaemia), hyperparathyroidism and in corticosteroid excess.

In alcoholics and a variety of drugs in addition to corticosteroids, e.g. chloroquine, vincristine; and in vitamin D deficiency.

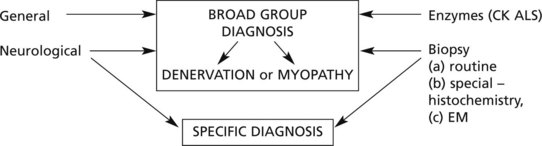

Muscle Diseases – Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of muscular weakness and atrophy is important since there is considerable variation in prognosis and management of these disorders, although often there is no treatment.

A diagnosis is usually reached from a synthesis of the information obtained from investigations under three headings:

The electromyogram records the activity of groups of muscle fibres and even of individual fibres (usually fine needle electrodes). The pathological changes are reflected in variations of the electrical potential within the muscle during various types of activity.

These methods distinguish primary myopathies, including myotonias, from denervation atrophy.

EM examination and biochemical analysis may identify specific disorders.