CHAPTER 112 Acute Gastroenteritis

CHAPTER 112 Acute Gastroenteritis

ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

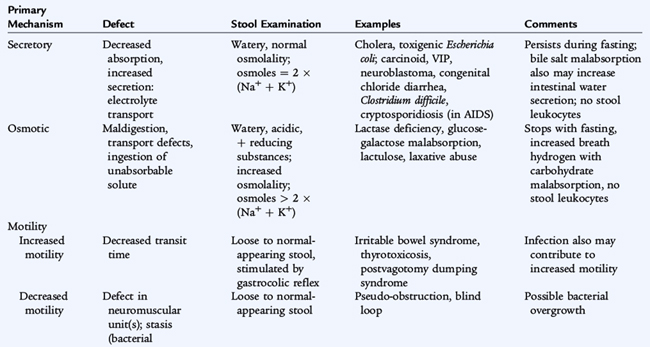

Acute enteritis or acute gastroenteritis refers to diarrhea, which is abnormally frequent and liquidity of fecal discharges. Diarrhea is caused by different infectious or inflammatory processes in the intestine that directly affect enterocyte secretory and absorptive functions (Table 112-1). Some of these processes act by increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) levels (Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin, vasoactive intestinal peptide–producing tumors). Other processes (Shigella toxin, congenital chloridorrhea) cause secretory diarrhea by affecting ion channels or by unknown mechanisms. Enteritis has many viral, bacterial, and parasitic causes (Table 112-2).

Diarrhea is a leading cause of morbidity and a common disease in children in the United States In the developing world, it is a major cause of childhood fatality. The epidemiology of gastroenteritis depends on the specific organisms. Some organisms are spread person to person, others are spread via contaminated food or water, and some are spread from animal to human. Many organisms spread by multiple routes. The ability of an organism to infect relates to the mode of spread, ability to colonize the gastrointestinal tract, and minimum number of organisms required to cause disease.

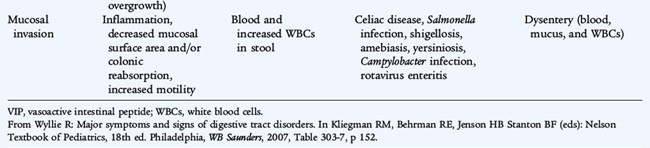

Viral causes of gastroenteritis in children include rotaviruses, caliciviruses (including the noroviruses), astroviruses, and enteric adenoviruses (serotypes 40 and 41). Rotavirus invades the epithelium and damages villi of the upper small intestine and, in severe cases, involves the entire small bowel and colon. Rotavirus is the most frequent cause of diarrhea during the winter months. Vomiting may last 3 to 4 days, and diarrhea may last 7 to 10 days. Dehydration is common in younger children. Primary infection with rotavirus may cause moderate to severe disease in infancy but is less severe later in life.

Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella typhi and, occasionally, Salmonella paratyphi. Worldwide, there are an estimated 16 million cases of typhoid fever annually, resulting in 600,000 deaths. The typhoid bacillus infects humans only. These infections are distinguished by prolonged fever and extraintestinal manifestations despite inconsistent presence of diarrhea. In the United States, approximately 400 cases of typhoid fever occur each year. Most occur in travelers returning from other countries. The incubation period of typhoid fever is usually 7 to 14 days (range 3–60 days). Infected persons without symptoms, or chronic carriers, serve as reservoirs and sources of continuous spread. Carriers often have cholelithiasis.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella produce diarrhea by invading the intestinal mucosa. The organisms are transmitted through contact with infected animals (chickens, pet iguanas, other reptiles, turtles) or from contaminated food products, such as dairy products, eggs, and poultry. A large inoculum, of 1000 to 10 billion organisms, is required because Salmonella are killed by gastric acidity. The incubation period for gastroenteritis ranges from 6 to 72 hours, but usually is less than 24 hours. Chronic carriage may develop.

Shigella dysenteriae may cause disease by producing Shiga toxin, either alone or combined with tissue invasion. The incubation period is 1 to 7 days. Infected adults may shed organisms for 1 month. Infection is spread by person-to-person contact or by the ingestion of contaminated food with 10 to 100 organisms. The colon is selectively affected. High fever and seizures may occur in addition to diarrhea.

Only certain strains of E. coli produce diarrhea. E. coli strains associated with enteritis are classified by the mechanism of diarrhea: enteropathogenic (EPEC), enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteroinvasive (EIEC), enterohemorrhagic (EHEC), or enteroaggregative (EAEC). EPEC is responsible for many of the epidemics of diarrhea in newborn nurseries and in day care centers. ETEC strains produce heat-labile (cholera-like) enterotoxin, heat-stable enterotoxin, or both. ETEC causes 40% to 60% of cases of traveler’s diarrhea. EPEC and ETEC adhere to the epithelial cells in the upper small intestine and produce disease by liberating toxins that induce intestinal secretion and limit absorption. EIEC invades the colonic mucosa, producing widespread mucosal damage with acute inflammation, similar to Shigella. EHEC, especially the E. coli O157:H7 strain, produce a Shiga-like toxin that is responsible for a hemorrhagic colitis and most cases of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which is a syndrome of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure (see Chapter 164). EHEC is associated with contaminated food, including unpasteurized fruit juices and especially undercooked beef. EHEC is associated with a self-limited form of gastroenteritis, usually with bloody diarrhea, but production of this toxin blocks host cell protein synthesis and affects vascular endothelial cells and glomeruli, resulting in the clinical manifestations of HUS.

Campylobacter jejuni is spread by person-to-person contact and by contaminated water and food, especially poultry, raw milk, and cheese. The organism invades the mucosa of the jejunum, ileum, and colon. Yersinia enterocolitica is transmitted by pets and contaminated food, especially chitterlings. Infants and young children characteristically have a diarrheal disease whereas older children usually have acute lesions of the terminal ileum or acute mesenteric lymphadenitis mimicking appendicitis or Crohn disease. Postinfectious arthritis, rash, and spondylopathy may develop.

Clostridium difficile causes C. difficile–associated diarrhea, or antibiotic-associated diarrhea, secondary to its toxin. The organism produces spores that spread from person to person. C. difficile–associated diarrhea may follow exposure to any antibiotic.

Entamoeba histolytica (amebiasis), Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium parvum are important enteric parasites found in North America. Amebiasis occurs in warmer climates, whereas giardiasis is endemic throughout the United States and is common among infants in day care centers. E. histolytica infects the colon; amebae may pass through the bowel wall and invade the liver, lung, and brain. Diarrhea is of acute onset, is bloody, and contains leukocytes. G. lamblia is transmitted through ingestion of cysts, either from contact with an infected individual or from food or freshwater or well water contaminated with infected feces. The organism adheres to the microvilli of the duodenal and jejunal epithelium. Cryptosporidium causes mild, watery diarrhea in immunocompetent persons that resolves without treatment. It produces severe, prolonged diarrhea in persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (see Chapter 125).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Gastroenteritis may be accompanied by systemic findings, such as fever, lethargy, and abdominal pain.

Viral diarrhea is characterized by watery stools, with no blood or mucus. Vomiting may be present, and dehydration may be prominent. Fever, when present, is low grade. Typhoid fever is characterized by bacteremia and fever that usually precede the final enteric phase. Fever, headache, and abdominal pain worsen over 48 to 72 hours with nausea, decreased appetite, and constipation over the first week. If untreated, the disease persists for 2 to 3 weeks marked by significant weight loss and occasionally hematochezia or melena. Bowel perforation is a common complication in adults, but is rare in children. Dysentery is enteritis involving the colon and rectum, with blood and mucus, possibly foul smelling, and fever. Shigella is the prototype cause of dysentery, which must be differentiated from infection with EIEC, EHEC, E. histolytica (amebic dysentery), C. jejuni, Y. enterocolitica, and nontyphoidal Salmonella. Gastrointestinal bleeding and blood loss may be significant. Enterotoxigenic disease is caused by agents that produce enterotoxins, such as V. cholerae and ETEC. Fever is absent or low grade. Diarrhea usually involves the ileum with watery stools without blood or mucus and usually lasts 3 to 4 days with four to five loose stools per day. Insidious onset of progressive anorexia, nausea, gaseousness, abdominal distention, watery diarrhea, secondary lactose intolerance, and weight loss is characteristic of giardiasis.

A chief consideration in management of a child with diarrhea is to assess the degree of dehydration as evident from clinical signs and symptoms, ongoing losses, and daily requirements (see Chapter 33). The degree of dehydration dictates the urgency of the situation and the volume of fluid needed for rehydration. Mild to moderate dehydration usually can be treated with oral rehydration; severe dehydration usually requires intravenous (IV) rehydration and may require ICU admission.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

Initial laboratory evaluation of moderate to severe diarrhea includes electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and urinalysis for specific gravity as an indicator of hydration. Stool specimens should be examined for mucus, blood, and leukocytes, which indicate colitis in response to bacteria that diffusely invade the colonic mucosa such as Shigella, Salmonella, C. jejuni, and invasive E. coli. Patients infected with Shiga toxin–producing E. coli and E. histolytica generally have minimal fecal leukocytes.

A rapid diagnostic test for rotavirus in stool should be performed, especially during the winter. Bacterial stool cultures are recommended for patients with fever, profuse diarrhea, and dehydration or if HUS is suspected. If the stool test result is negative for blood and leukocytes, and there is no history to suggest contaminated food ingestion, a viral etiology is most likely. Stool evaluation for parasitic agents should be considered for acute dysenteric illness, especially in returning travelers, and in protracted cases of diarrhea in which no bacterial agent is identified. The diagnosis of E. histolytica is based on identification of the organism in the stool. Serologic tests are useful for diagnosis of extraintestinal amebiasis, including amebic hepatic abscess. Giardiasis can be diagnosed by identifying trophozoites or cysts in stool; less often a duodenal aspirate or biopsy of the duodenum or upper jejunum is needed. Giardia is excreted intermittently; three specimens are required. If stool tests are nondiagnostic, the duodenal fluid may be examined using the Entero-Test, a nylon string affixed to a gelatin capsule, which is swallowed. After several hours, the string is withdrawn and duodenal contents are examined for G. lamblia trophozoites.

Positive blood cultures are uncommon with bacterial enteritis except for S. typhi (typhoid fever), nontyphoidal Salmonella, and E. coli enteritis in very young infants. In typhoid fever, blood cultures are positive early in the disease, whereas stool cultures become positive only after the secondary bacteremia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Diarrhea can be caused by infection, toxins, gastrointestinal allergy (including allergy to milk or its components), malabsorption defects, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, or any injury to enterocytes. Specific infections are differentiated from each other by the use of stool cultures and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, when necessary. Acute enteritis may mimic other acute diseases, such as intussusception and acute appendicitis, which are best identified by diagnostic imaging. Many noninfectious causes of diarrhea produce chronic diarrhea, with persistence for more than 14 days. Persistent or chronic diarrhea may require tests for malabsorption or invasive studies, including endoscopy and small bowel biopsy (see Chapter 129).

Common-source diarrhea usually is associated with ingestion of contaminated food. In the United States, the most common bacterial food-borne causes (in order of frequency) are nontyphoidal Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, E. coli O157:H7, Yersinia, Listeria monocytogenes, and V. cholerae. The most common parasitic food-borne causes are Cryptosporidium parvum and Cyclospora cayetanensis. Common-source diarrhea also includes ingestion of preformed enterotoxins produced by bacteria, such as S. aureus and Bacillus cereus, which multiply in contaminated foods, and nonbacterial toxins such as from fish, shellfish, and mushrooms. After a short incubation period, vomiting and cramps are prominent symptoms, and diarrhea may or may not be present. Heavy metals that leach into canned food or drinks causing gastric irritation and emetic syndromes may mimic symptoms of acute infectious enteritis.

TREATMENT

Most infectious causes of diarrhea in children are self-limited. Management of viral and most bacterial causes of diarrhea is primarily supportive and consists of correcting dehydration and ongoing fluid and electrolyte deficits and managing secondary complications resulting from mucosal injury.

Hyponatremia is common; hypernatremia is less common. Metabolic acidosis results from losses of bicarbonate in stool, lactic acidosis results from shock, and phosphate retention results from transient prerenal-renal insufficiency. Traditionally, therapy for 24 hours with oral rehydration solutions alone is effective for viral diarrhea. Therapy for severe fluid and electrolyte losses involves IV hydration. Less severe degrees of dehydration (<10%) in the absence of excessive vomiting or shock may be managed with oral rehydration solutions containing glucose and electrolytes. Ondansetron may be administered to reduce emesis when persistent.

Antibiotic therapy is necessary only for patients with S. typhi (typhoid fever) and sepsis or bacteremia with signs of systemic toxicity, those with metastatic foci, or infants younger than 3 months with nontyphoidal salmonella. Antibiotic treatment of Shigella produces a bacteriologic cure in 80% of patients after 48 hours, reducing the spread of the disease. Many Shigella sonnei isolates, the predominant strain affecting children, are resistant to amoxicillin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ). Recommended treatment for children is an oral third-generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone for patients 18 years and older.

Treatment of C. difficile includes discontinuation of the antibiotic and, if diarrhea is severe, oral metronidazole or vancomycin. E. histolytica dysentery is treated with metronidazole followed by a luminal agent, such as iodoquinol. The treatment of G. lamblia is with albendazole, metronidazole, furazolidone, or quinacrine. Nitazoxanide can be used in children younger than 12 months of age for the treatment of Cryptosporidium.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

The major complication of gastroenteritis is dehydration and the cardiovascular compromise that can occur with severe hypovolemia. Seizures may occur with high fever, especially with Shigella. Intestinal abscesses can form with Shigella and Salmonella infections, especially typhoid fever, leading to intestinal perforation, a life-threatening complication. Severe vomiting associated with gastroenteritis can cause esophageal tears or aspiration.

Deaths resulting from diarrhea reflect the principal problem of disruption of fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, which leads to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, vascular instability, and shock. In the United States, approximately 75 to 150 deaths occur annually from diarrheal disease, primarily in children under 1 year of age. These deaths occur in a seasonal pattern between October and February, concurrent with the rotavirus season.

At least 10% of patients who have typhoid fever shed S. typhi for about 3 months, and 4% become chronic carriers. The risk of becoming a chronic carrier is low in children. Ciprofloxacin is recommended for adult carriers with persistent Salmonella excretion.

PREVENTION

The most important means of preventing childhood diarrhea is the provision of clean, uncontaminated water and proper hygiene in growing, collecting, and preparing foods. Good hygienic measures, especially good hand washing with soap and water, are the best means of controlling person-to-person spread of most organisms causing gastroenteritis. Similarly, poultry products should be considered potentially contaminated with Salmonella and should be handled and cooked appropriately.

Immunization against rotavirus infection is recommended for all children beginning at 6 weeks of age, with the first dose by 14 weeks 6 days and the last dose by 8 months (see Chapter 94). Two typhoid vaccines are licensed in the United States: an oral live attenuated vaccine (Ty21a) for children 6 years and older, and a capsular polysaccharide vaccine (ViCPS) for intramuscular (IM) administration for persons 2 years and older. These are not recommended for travelers to endemic areas of developing countries or for household contacts of S. typhi chronic carriers.

Families should be aware of the risk of acquiring salmonellosis from household reptile pets. Transmission of Salmonella from reptiles can be prevented by thorough hand washing with soap and water after handling reptiles or reptile cages. Children under 5 years of age and immunocompromised persons should avoid contact with reptiles. Pet reptiles should not roam freely in the home or living areas and should be kept out of kitchens and food preparation areas to prevent contamination.

The risk for traveler’s diarrhea, caused primarily by ETEC, may be minimized by avoiding uncooked food and untreated drinking water. Prophylaxis with bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) for adults (2 oz or 2 tablets orally four times a day) may be effective for prevention but is not recommended for children. Symptomatic self-treatment for mild diarrhea with loperamide (Imodium) and WHO oral rehydration solution (ORS) is recommended for children at least 6 years of age and adults. Self-treatment of moderate diarrhea and fever with a fluoroquinolone is recommended in adults at least 18 years old. Prompt medical evaluation is indicated for disease persisting more than 3 days, bloody stools, fever above 102°F or chills, persistent vomiting, or moderate to severe dehydration, especially in children.

Lactobacillus acidophilus is a probiotic and reduces the incidence of community-acquired and antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children treated with oral antibiotics for other infectious diseases.