CHAPTER 126 Digestive System Assessment

CHAPTER 126 Digestive System Assessment

Children commonly present with symptoms originating in the digestive tract. The pediatrician needs to be able to evaluate a child’s symptoms quickly using knowledge, careful history, physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic tests.

HISTORY

Younger children may not be able to describe symptoms accurately, so reports of caregivers are important. Proper assessment of the history before moving on to physical examination and diagnostic testing helps narrow the possibilities and allows a focused examination and precise use of diagnostic studies.

Onset and progression of the major symptom should be characterized. Changes in symptoms, triggers that aggravate or alleviate the symptom and associated symptoms (e.g., fever, weight loss), and exposures to others (through travel or environmental exposure) should be identified.

Next, the pediatrician should ask about the child’s current status, what investigations have been performed, and whether therapies have been used. Important issues include the frequency and duration of symptoms and their the relationship to meals and defecation and impact on activities (school attendance). If medications have been used, therapeutic effect should be determined. Finally, the initial visit should include a thorough review of systems, family history, social history, and past medical history.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Children with gastrointestinal (GI) complaints need a full general examination and a thorough abdominal examination. Extraintestinal disorders may produce GI manifestations (e.g., emesis and group A streptococcal pharyngitis; abdominal pain and lower lobe pneumonia). A careful external inspection should evaluate for abdominal distention, bruising or discoloration, abnormal veins, jaundice, surgical scars, and ostomies. Abnormalities of intensity and pitch of bowel sounds should be determined. Palpation should assess for tenderness, noting location, facial expression, guarding, and rebound tenderness. The liver and spleen should be examined, measuring enlargement with a tape measure and noting abnormal firmness or contour. Assessment for the presence of palpable feces and mass lesions should occur. A rectal examination needs to be done when it is indicated. Children with history suggesting constipation, GI bleeding, abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, and suspicion of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may have important findings on rectal examination. The rectal examination includes external inspection for fissures, skin tags, abscesses, and fistulous openings. Digital rectal examination should include assessment of anal sphincter tone, anal canal size and elasticity, tenderness, extrinsic masses, presence of fecal impaction, and caliber of the rectum. Stool obtained on the glove should be tested for occult blood.

SCREENING TESTS

After the history and physical examination, laboratory testing may guide the diagnosis or treatment. Careful selection of tests minimizes cost, discomfort, and risk to the patient.

A complete blood count may provide evidence of inflammation (white blood cell [WBC] and platelet count), poor nutrition or bleeding (hemoglobin, red blood cell volume, reticulocyte count), and infection (WBC number and differential, presence of toxic granulation). Serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine help define hydration status. Tests of liver function include total and direct bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and γ-glutamyltransferase or alkaline phosphatase for more specific evidence of bile duct injury. Hepatic synthetic function can be assessed by coagulation factor levels, coagulation times, and albumin level. Pancreatic enzyme tests (amylase, lipase, trypsinogen) provide evidence of pancreatic injury or inflammation. Tests also are available for specific conditions, such as celiac disease, viral hepatitis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease (CD), and metabolic conditions. Urinalysis can be helpful in gauging dehydration and assessing effects of digestive system disease on the urinary tract.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Radiology

Plain abdominal radiographs and barium studies have great utility. There is usually no reason to start with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for evaluation of most symptoms. In choosing an imaging study, consultation with a radiologist is often advisable, not only to discuss the best imaging method, but to decide what variants of the technique should be used and how to prepare the patient for the study. In some cases, it is important for the patient to be fasting (ultrasound examination of the gallbladder). An intravenous (IV) catheter may be needed for contrast agent or radionuclide administration, or a preparatory enema may be required.

It is not necessary to obtain a plain abdominal x-ray to document excessive retained stool in a child whose history is consistent with constipation and encopresis. Examination alone can confirm the presence of a fecal mass in the left lower quadrant. Rectal examination can disclose fecal impaction. Similarly, if a simple barium upper GI series is planned to diagnose small bowel Crohn’s disease, a CT scan may not be needed, unless there are other concerns, such as abscess or lymphoma.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy permits the direct visualization of the interior of the gut. Modern equipment includes video endoscopes with high-quality electronic optics. Endoscopes are small and flexible, and may be used even in very small infants. The design of endoscopes permits a great deal of control of tip movement, illumination, image acquisition, and endoscope advancement through the gut. Endoscopes also allow for suction of intestinal contents and air and water insufflation; they have a separate channel for introducing instruments, such as biopsy forceps, snares, foreign body retrievers, electrocoagulators, injection needles, and other specialized tools. Wireless capsule endoscopy (Fig. 126-1) extends the diagnostic capabilities of endoscopy, enabling visualization of lesions beyond the reach of conventional endoscopes.

COMMON MANIFESTATIONS OF GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS

Abdominal Pain

General Considerations

Abdominal pain can result from injury to the intra-abdominal organs, injury to overlying somatic structures in the abdominal wall, or extra-abdominal diseases. Visceral pain results when nerves within the gut detect injury. Visceral sensation is transmitted by nonmyelinated fibers and is vague, dull, slow in onset, and poorly localized. A variety of stimuli, including normal peristalsis and various chemical and osmotic states, activate these fibers to some degree, allowing some sensation of normal activity. Regardless of the stimulus, visceral pain is perceived when a threshold of intensity or duration is crossed. Lower degrees of activation may result in perception of nonpainful or perhaps vaguely uncomfortable sensations, whereas more intensive stimulation of these fibers results in pain. Overactive sensation may be the basis of some kinds of abdominal pain, such as functional abdominal pain.

In contrast to visceral pain, somatic pain results when overlying body structures are injured. Somatic structures include the parietal peritoneum, fascia, muscles, and skin of the abdominal wall. In contrast to the vague, poorly localized pain emanating from visceral injury, somatic nociceptive fibers are myelinated and are capable of rapid transmission of well-localized painful stimuli. When intra-abdominal processes extend to cause inflammation or injury to the parietal peritoneum or abdominal wall structures, poorly localized visceral pain becomes well-localized somatic pain. In acute appendicitis, visceral nociceptive fibers are activated initially, yielding poorly localized discomfort in the midabdomen. When the inflammatory process extends to involve the overlying parietal peritoneum, the pain becomes severe and localizes to the right lower quadrant. This is called somatoparietal pain.

Referred pain is a painful sensation in a body region distant from the true source of pain. The physiologic cause is the activation of spinal cord somatic sensory cell bodies by intense signaling from visceral afferent nerves, located at the same level of the spinal cord. The location of referred pain is predictable based on the locus of visceral injury. Stomach pain is referred to the epigastric and retrosternal regions. Liver and pancreas pain is referred to the epigastric region. Gallbladder pain often is referred to the region below the right scapula. Splenic pain is referred to the left shoulder. Somatic pathways stimulated by small bowel visceral afferents affect the periumbilical area. Colonic injury results in infraumbilical referred pain.

Acute Abdominal Pain

Distinguishing Features

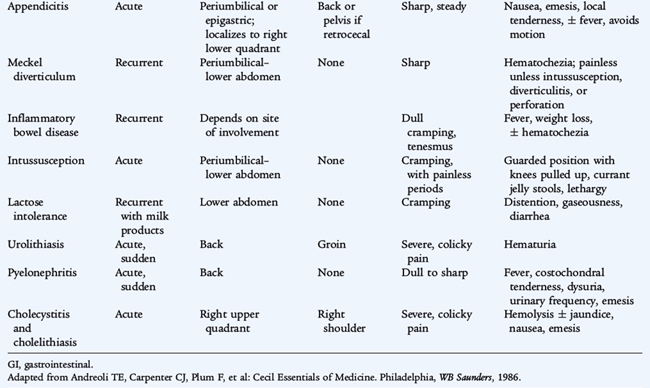

Acute abdominal pain can signal the presence of a dangerous intra-abdominal process, such as appendicitis or bowel obstruction, or may originate from extraintestinal sources, such as lower lobe pneumonia or urinary tract infection or stone. Not all episodes of acute abdominal pain require emergency intervention. Appendicitis must be ruled out as quickly as possible. Only a few children presenting with acute abdominal pain actually have a surgical emergency. These surgical cases must be separated from cases that can be managed conservatively (see Tables 126-2 and 126-3).

Diagnostic Evaluation

Important clues to the diagnosis can be determined by history and physical examination (Tables 126-1 to 126-3). The onset of pain can provide clues. Events that occur abruptly (e.g., passage of a stone, perforation of a viscus, or infarction) result in a sudden onset. Gradual onset of pain is common with infectious or inflammatory causes (e.g., appendicitis, IBD).

TABLE 126-1 Diagnostic Approach to Acute Abdominal Pain

| HISTORY | |

| Onset | Sudden or gradual, prior episodes, association with meals, history of injury |

| Nature | Sharp versus dull, colicky or constant, burning |

| Location | Epigastric, periumbilical, generalized, right or left lower quadrant, change in location over time |

| Fever | Presence suggests appendicitis or other infection |

| Extraintestinal symptoms | Cough, dyspnea, dysuria, urinary frequency, flank pain |

| Course of symptoms | Worsening or improving, change in nature or location of pain |

| PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | |

| General | Growth and nutrition, general appearance, hydration, degree of discomfort, body position |

| Abdominal | Tenderness, distention, bowel sounds, rigidity, guarding, mass |

| Genitalia | Testicular torsion, hernia, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy |

| Surrounding structures | Breath sounds, rales, rhonchi, wheezing, flank tenderness, tenderness of abdominal wall structures, ribs, costochondral joints |

| Rectal examination | Perianal lesions, stricture, tenderness, fecal impaction, blood |

| LABORATORY | |

| CBC, C-reactive protein, ESR | Evidence of infection or inflammation |

| AST, ALT, GGT, bilirubin | Biliary or liver disease |

| Amylase, lipase | Pancreatitis |

| Urinalysis | Urinary tract infection, bleeding due to stone, trauma, or obstruction |

| Pregnancy test (older females) | Ectopic pregnancy |

| RADIOLOGY | |

| Plain flat and upright abdominal films | Bowel obstruction, appendiceal fecalith, free intraperitoneal air, kidney stones |

| CT scan | Rule out abscess, appendicitis, Crohn disease, pancreatitis, gallstones, kidney stones |

| Barium enema | Intussusception, malrotation |

| Ultrasound | Gallstones, appendicitis, intussusception, pancreatitis, kidney stones, ovarian/tube diseases |

| ENDOSCOPY | |

| Upper endoscopy | Suspected peptic ulcer or esophagitis |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CBC, complete blood count, ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase.

Adapted from Andreoli TE, Carpenter CJ, Plum F, et al: Cecil Essentials of Medicine. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1986.

A standard group of laboratory tests usually is performed for abdominal pain (see Table 126-1). After an abdominal x-ray series is obtained, further imaging studies may be warranted. CT can visualize the appendix if appendicitis is suspected. If the initial evaluation suggests intussusception, a barium or pneumatic (air) enema may be the first choice to diagnose and treat this condition with hydrostatic reduction (see Chapter 129).

Differential Diagnosis (Table 126-2)

Acute pain requires an urgent evaluation to rule out surgical emergencies. In young children, malrotation, incarcerated hernia, congenital anomalies, and intussusception are common concerns. In older children and teenagers, appendicitis is more common. An acute surgical abdomen is characterized by signs of peritonitis, including tenderness, abdominal wall rigidity, guarding, and absent or diminished bowel sounds. Helpful characteristics of onset, location, referral, and quality of pain are noted in Table 126-3.

Functional Abdominal Pain and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Recurrent abdominal pain is a common problem, affecting more than 10% of all children. The peak incidence occurs between ages 7 and 12 years. The differential diagnosis of recurrent abdominal pain is fairly extensive (Table 126-4). However, most children with this condition do not have a serious (or identifiable) underlying illness causing the pain.

Differential Diagnosis

Children with functional abdominal pain characteristically have pain almost daily. The pain is not associated with meals or relieved by defecation, and is often associated with a tendency toward anxiety and perfectionism. Symptoms often result from stress at school or in novel social situations. The pain often is worst in the morning and prevents or delays them from attending school. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a subset of functional abdominal pain, characterized by onset of pain at the time of a change in stool frequency or consistency, a stool pattern fluctuating between diarrhea and constipation, and relief of pain with defecation. Symptoms in IBS are linked to gut motility. Pain is commonly accompanied in both groups of children by school avoidance, secondary gains, anxiety about imagined causes, lack of coping skills, and disordered peer relationships.

Distinguishing Features

One needs to distinguish between functional pain/IBS and more serious underlying disorders. Warning signs for underlying illness are listed in Table 126-5. If any warning signs are present, further investigation is necessary. Even if the warning signs are absent, some laboratory evaluation is warranted. A judicious laboratory evaluation after a careful history and complete physical examination can assure parents and physicians that no serious illness is being missed. The initial evaluation recommended in Table 126-6 is a sensible approach, avoiding unnecessary testing and providing ample sensitivity for most serious underlying disorders. A 3-day trial of a lactose-free diet can rule out lactose intolerance. If tests are normal and no warning signs are present, testing should be stopped. If there are warning signs, progression of symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities that suggest a specific diagnosis, additional investigation may be warranted. For example, if antacids consistently relieve pain, an upper GI endoscopy to look for peptic disease may be considered. If the child is losing weight, a barium upper GI series with a small bowel follow-through or CT can be performed to look for evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Celiac disease (see Chapter 129) also should be considered and diagnosed by antibody testing and endoscopic duodenal biopsy.

TABLE 126-6 Suggested Evaluation of Recurrent Abdominal Pain

| Initial Evaluation | Follow-up Evaluation* |

|---|---|

CBC, complete blood count; CT, computed tomography; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GI, gastrointestinal.

* Consider using one or more of these to investigate warning signs, abnormal laboratory tests, or specific or persistent symptoms.

Treatment

A child who is repeatedly kept home from school because of pain receives attention for his symptoms, is excused from responsibilities, and withdraws from full social functioning. This situation tends to both increase anxiety and provide positive reinforcement for being ill. To break the cycle of pain and disability, the child with functional pain must be assisted in returning to normal activities immediately. The child should not be sent home from school with stomachaches; rather, the child may be allowed to take a short break from class until the cramping abates. It is useful to inform the child and the parents that the pain is likely to be worse on the day the child returns to school, because anxiety worsens dysmotility and enhances pain perception. Sometimes, medications can be helpful. Fiber supplements are useful to manage symptoms of IBS. In difficult and persistent cases, amitriptyline or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor may be helpful. When significant anxiety or social dysfunction persists, a mental health professional should be consulted.

Vomiting

Vomiting is a coordinated, sequential series of events that leads to forceful oral emptying of gastric contents. It is a common problem in children and has many causes. Vomiting should be distinguished from regurgitation of stomach contents, also known as gastroesophageal reflux (GER), chalasia, or spitting up. Although the end result of vomiting and regurgitation is similar, they have completely different characteristics. Vomiting is usually preceded by nausea, followed by forceful gagging and retching. Regurgitation, on the other hand, is effortless and not preceded by nausea.

Differential Diagnosis

In neonates with true vomiting, congenital obstructive lesions should be considered. Allergic reactions to formula also are common in the first 2 months of life. Infantile GER (“spitting up”) occurs in most infants and can be large in volume, but is effortless and these infants do not appear ill. Pyloric stenosis occurs in the first month of life and is characterized by steadily worsening, forceful vomiting which occurs immediately after feedings. Prior to vomiting a distended stomach, often with visible peristaltic waves is often seen. Pyloric stenosis is more common in male infants, and there may be a positive family history. Other obstructive lesions, such as intestinal duplication cysts, atresias, webs, and midgut malrotation must be ruled out. Metabolic disorders (organic acidemias, galactosemia, urea cycle defects, etc.) can cause vomiting in infants. In older children with acute vomiting, viral illnesses are common. Other infections, especially streptococcal pharyngitis, urinary tract infections, and otitis media, commonly result in vomiting. When vomiting is chronic, central nervous system (CNS) causes (increased intracranial pressure, migraine) must be considered. When abdominal pain or bilious emesis accompanies vomiting, evaluation for bowel obstruction, peptic disorders, and appendicitis must be immediately initiated.

Distinguishing Features

Physicians caring for children see hundreds of patients with viral gastroenteritis for every one with a less common diagnosis. It is important to be alert for unusual features that suggest another diagnosis (Table 126-7). Viral gastroenteritis usually is not associated with severe abdominal pain or headache and does not recur at frequent intervals.

TABLE 126-7 Differential Diagnosis of Vomiting by Historical Features

| Potential Diagnosis | Historical Clues |

|---|---|

| Viral gastroenteritis | Fever, diarrhea, sudden onset, absence of pain |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | Effortless, not preceded by nausea, chronic |

| Hepatitis | Jaundice, history of exposure |

| Extragastrointestinal infections | |

| Otitis media | Fever, ear pain |

| Urinary tract infection | Dysuria, unusual urine odor, frequency, incontinence |

| Pneumonia | Cough, fever, chest discomfort |

| Allergic | |

| Milk or soy protein intolerance (infants) | Associated with particular formula or food, blood in stools |

| Other food allergy (older children) | |

| Peptic ulcer or gastritis | Epigastric pain, blood or coffee-ground material in emesis, pain relieved by acid blockade |

| Appendicitis | Fever, abdominal pain migrating to the right lower quadrant, tenderness |

| Anatomic obstruction | |

| Intestinal atresia | Neonate, usually bilious, polyhydramnios |

| Midgut malrotation | Pain, bilious vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, shock |

| Intussusception | Colicky pain, lethargy, vomiting, currant jelly stools, mass occasionally |

| Duplication cysts | Colic, mass |

| Pyloric stenosis | Nonbilious vomiting, postprandial, <4 mo old, hunger |

| Bacterial gastroenteritis | Fever, often with bloody diarrhea |

| Central nervous system | |

| Hydrocephalus | Large head, altered mental status |

| Meningitis | Fever, stiff neck |

| Migraine syndrome | Attacks scattered in time, relieved by sleep; headache |

| Cyclic vomiting syndrome | Similar to migraine, usually no headache |

| Brain tumor | Morning vomiting, accelerating over time, headache, diplopia |

| Motion sickness | Associated with travel in vehicle |

| Labyrinthitis | Vertigo |

| Metabolic disease | Presentation early in life, worsens when catabolic or with exposure to substrate |

| Pregnancy | Morning, sexually active, cessation of menses |

| Drug reaction or side effect | Associated with increased dose or new medication |

| Cancer chemotherapy | Temporally related to administration of chemotherapeutic drugs |

Assessment

Physical examination should include assessment of the child’s hydration status, including examination of capillary refill, moistness of mucous membranes, and skin turgor (see Chapter 38). The chest should be auscultated for evidence of pulmonary involvement. The abdomen must be examined carefully for distention, organomegaly, bowel sounds, tenderness, and guarding. A rectal examination and testing stool for occult blood should be performed.

Laboratory evaluation of vomiting should include serum electrolytes, tests of renal function, complete blood count, amylase, lipase, and liver function tests. Additional testing may be required immediately when history and examination suggest a specific etiology. Ultrasound is useful to look for pyloric stenosis, gallstones, renal stones, hydronephrosis, biliary obstruction, pancreatitis, appendicitis, malrotation, intussusception, and other anatomic abnormalities. CT may be indicated to rule out appendicitis or to observe structures that cannot be visualized well by ultrasound. Barium studies can show obstructive or inflammatory lesions of the gut and can be therapeutic, as in the use of contrast enemas for intussusception (see Chapter 129).

Treatment

Treatment of vomiting needs to address the consequences and causes of the vomiting. Dehydration must be treated with fluid resuscitation. This can be accomplished in most cases with oral fluid-electrolyte solutions, but IV fluids are commonly required. Electrolyte imbalances should be corrected by appropriate choice of fluids. Underlying causes should be treated when possible.

The use of antiemetic medications is controversial. These drugs should not be prescribed until the etiology of the vomiting is known and then only for severe symptoms. Phenothiazines, such as prochlorperazine, may be useful for reducing symptoms in food poisoning and motion sickness. Their side effect profile must be considered carefully, and the dose prescribed should be conservative. Anticholinergics, such as scopolamine, and antihistamines, such as dimenhydrinate, are useful for the prophylaxis and treatment of motion sickness. Drugs that block serotonin 5-HT3 receptors, such as ondansetron and granisetron, are used for viral gastroenteritis, and can improve tolerance of oral rehydration therapy. They are clearly helpful for chemotherapy-induced vomiting, often combined with dexamethasone. No antiemetic should be used in patients with surgical emergencies or when a specific treatment of the underlying condition is possible. Correction of dehydration, ketosis, and acidosis by oral or intravenous rehydration is helpful to reduce vomiting in most patients with viral gastroenteritis.

Acute and Chronic Diarrhea

Parents use the word diarrhea to describe loose or watery stools, excessively frequent stools, or stools that are large in volume. Constipation with overflow incontinence can be mislabeled as diarrhea. A more exact definition is excessive daily stool liquid volume (>10 mL stool/kg body weight/day).

Diarrhea is a major cause of childhood morbidity and fatality worldwide. Deaths from diarrhea are rare in developed countries, but are common elsewhere. Acute diarrhea is a major problem when it occurs with malnutrition or in the absence of basic medical care (see Chapter 30). In North America, most acute diarrhea is viral, is self-limited, and requires no diagnostic testing or specific intervention. Bacterial agents tend to cause more severe illness and typically are seen in outbreaks or in regions with poor public sanitation. Bacterial enteritis should be suspected when there is dysentery (bloody diarrhea with fever) and whenever severe symptoms are present. These infections can be diagnosed by stool culture or other assays for specific pathogens. Chronic diarrhea lasts more than 2 weeks and has a wide range of possible causes, including more difficult to diagnose serious and benign conditions.

Differential Diagnosis

Diarrhea may be classified by etiology or by physiologic mechanisms (secretory or osmotic). Etiologic agents include viruses, bacteria or their toxins, chemicals, parasites, malabsorbed substances, and inflammation (Table 126-8). Secretory diarrhea occurs when the intestinal mucosa directly secretes fluid and electrolytes into the stool. Secretion may be the result of inflammation, as in inflammatory bowel disease, or a chemical stimulus. Cholera is a secretory diarrhea stimulated by the enterotoxin of Vibrio cholerae which causes increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) within enterocytes, leading to secretion into the small bowel lumen. Secretion also is stimulated by mediators of inflammation and by various hormones, such as vasoactive intestinal peptide secreted by a neuroendocrine tumor.

Osmotic diarrhea occurs after malabsorption of an ingested substance, which “pulls” water into the bowel lumen. A classic example is the diarrhea of lactose intolerance. Osmotic diarrhea also can result from maldigestion, such as that seen with pancreatic insufficiency, or with malabsorption caused by intestinal injury. Certain nonabsorbable laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol and milk of magnesia, also cause osmotic diarrhea. Fermentation of malabsorbed substances (e.g., lactose) often occurs, resulting in gas, cramps, and acidic stools. The most common non infectious cause of loose stools in early childhood is functional diarrhea, commonly known as toddler’s diarrhea. This condition is defined by frequent watery stools in the setting of normal growth and weight gain. It is caused by excessive intake of carbohydrate-containing sweet liquids, overwhelming the absorptive capacity of the intestine. Diarrhea typically improves tremendously when the child’s beverage intake is reduced or changed.

Distinguishing Features

Stools are isosmotic—that is, they have the same osmolarity as body fluids. This is true even in osmotic diarrhea, because of the relatively free exchange of water across the intestinal mucosa. Osmoles present in the stool are a mixture of electrolytes and other osmotically active solutes. To determine whether the diarrhea is osmotic or secretory, the osmotic gap may be calculated:

The formula for the osmotic gap assumes that the stool is isosmotic (an osmolarity of 290 mOsm/L). Stool sodium and potassium are measured, added together, and multiplied by 2 to account for their associated anions. This result is subtracted from 290. Secretory diarrhea is characterized by an osmotic gap of less than 50 because most of the dissolved substances in the stool are electrolytes. A number significantly higher than 50 defines osmotic diarrhea and indicates that malabsorbed substances other than electrolytes account for fecal osmolarity.

Another way to differentiate between osmotic and secretory diarrhea is to stop all oral feedings and observe whether the diarrhea stops. It must be done only in a hospitalized patient receiving IV fluids to prevent dehydration. If the diarrhea stops completely, the patient has osmotic diarrhea. A child with secretory diarrhea continues to have stool output. Neither method for classifying diarrhea works perfectly, as most diarrheal illnesses are a mixture of secretory and osmotic components. Viral enteritis damages the intestinal lining, causing malabsorption and osmotic diarrhea. The associated inflammation results in release of mediators that cause excessive secretion. A child with viral enteritis may have decreased stool volume while not receiving oral feedings (NPO), but the secretory component persists until the inflammation resolves.

The history should include the onset of diarrhea, number and character of stools, estimates of stool volume, and presence of other symptoms, such as blood in the stool, fever, and weight loss. Recent travel should be documented, dietary factors should be investigated, and a list of medications recently used should be obtained. Factors that seem to worsen or improve the diarrhea should be determined. Physical examination should be thorough, including evaluation for abdominal distention, tenderness, bowel sound characteristics, presence of blood, and evidence of dehydration or shock.

Laboratory testing includes stool culture and complete blood count if bacterial enteritis is suspected. If diarrhea occurs after a course of antibiotics, a Clostridium difficile toxin assay should be ordered. If stools are oily or fatty, fecal fat content should be checked. Tests for specific diagnoses should be sent when appropriate, such as serum antibody tests for celiac disease or colonoscopy for suspected inflammatory bowel disease. A trial of lactose restriction for several days is helpful to rule out lactose intolerance.

Constipation and Encopresis

Constipation is a common problem in childhood, accounting for a significant proportion of clinic visits. When a child is thought to be constipated, the parents may be concerned about straining with defecation, hard stool consistency, large stool size, decreased stool frequency, fear of passing stools, or any combination of these. Physicians define constipation as two or fewer stools per week or passage of hard, pellet-like stools for at least 2 weeks. A common pattern of constipation is functional constipation, which is characterized by two or fewer stools per week, voluntary withholding of stool and infrequent passage of large diameter, often painful, stools. Children with functional fecal retention often exhibit retentive posturing (standing or sitting with legs extended and stiff or crossed legs) and have associated fecal incontinence caused by leakage of retained stool (encopresis).

Differential Diagnosis

Young children are vulnerable to functional constipation. Functional constipation commonly occurs during toilet training, when the child is unwilling to defecate on the toilet. Retained stool becomes harder and larger over time, leading to painful defecation. This aggravates voluntary withholding of stool, with perpetuation of the constipation.

Hirschsprung disease is characterized by delayed meconium passage in newborns, abdominal distention, vomiting, occasional fever, and foul-smelling stools. This condition is caused by failure of ganglion cells to migrate into the distal bowel, resulting in spasm and functional obstruction of the aganglionic segment. Only about 6% of infants with Hirschsprung disease pass meconium in the first 24 hours of life compared with 95% of normal infants. Most affected babies rapidly become ill with symptoms of enterocolitis or obstruction. Affected older children do not pass large-caliber stools because of rectal spasm. They do not have encopresis. When evaluating a 3-year-old with fear of defecation, large stools, fecal soiling, and no history of neonatal constipation, Hirschsprung disease is not a likely diagnosis. Other causes of constipation include spinal cord abnormalities, hypothyroidism, drugs, cystic fibrosis, and anorectal malformations (Table 126-9). A variety of systemic disorders affecting metabolism or muscle function can result in constipation. Children with developmental disabilities have a great propensity for constipation because of diminished capacity to cooperate with toileting, reduced effort or control of pelvic floor muscles during defecation, and diminished perception of the need to pass stool.

TABLE 126-9 Common Causes of Constipation and Characteristic Features

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Distinguishing Features

Congenital malformations usually cause symptoms from birth. Functional constipation is overwhelmingly the most common diagnosis in older patients. Constipation in older children often begins after starting school, when free and private access to toilets may be restricted. Use of some drugs, especially opiates and some psychotropic medications, also is associated with constipation.

For a few specific causes of constipation, directed diagnostic testing can make the diagnosis. Hirschsprung disease can be suggested by findings on barium enema: a narrowed aganglionic distal bowel and dilated proximal bowel. Rectal suction biopsy confirms the absence of ganglion cells in the rectal submucosal plexus, with hypertrophy of nerve fibers. Lack of internal anal sphincter relaxation can be shown by anorectal manometry in Hirschsprung disease. Hypothyroidism is diagnosed by thyroid function testing. Anorectal malformations are easily detected by rectal examination. Cystic fibrosis (meconium ileus) is diagnosed by sweat chloride determination or CFTR gene mutation analysis (see Chapter 137). Most children with constipation have functional constipation and do not have any laboratory abnormality. Examination reveals normal or reduced anal sphincter tone (owing to stretching by passage of large stools). Fecal impaction is usually present, but a large caliber, empty rectum may be found if a stool has just been passed.

Evaluation and Treatment of Functional Constipation

In most cases of constipation, the history is consistent with functional constipation—absence of neonatal constipation, active fecal retention, and infrequent, large stools with soiling. In these patients, no testing is necessary other than a good physical examination. A prolonged course of stool softener therapy is needed in these children to alleviate fear of defecation. The child should be asked to sit on the toilet for a few minutes on awakening in the morning and immediately after meals, when the colon is most active and it is easiest to pass a stool. Use of a positive reinforcement system for taking medication and sitting on the toilet is a helpful for younger children. The stool softener chosen should be non–habit forming, safe, and palatable. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and milk of magnesia are the most commonly used agents. PEG, which is tasteless and minimally absorbed, has become the preferred stool-softening laxative for most situations.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

GI tract bleeding can be an emergency when large volume bleeding is present, but the presence of small amounts of blood in stool or vomitus is also sufficient to cause concern. Evaluation of bleeding should include confirmation that blood truly is present, estimation of the amount of bleeding, stabilization of vital signs, localization of the source of bleeding, and appropriate treatment of the underlying cause. When bleeding is massive, it is crucial that the patient receive adequate resuscitation with fluid and blood products before moving ahead with diagnostic testing.

Differential Diagnosis

In newborns, blood in vomitus or stool may be maternal blood swallowed during delivery or during breastfeeding. Blood-streaked stools are particularly associated with allergic colitis or necrotizing enterocolitis in this age group, but small streaks of bright red blood also can be seen in the diaper of infants with an anal fissure or milk allergy. Coagulopathy, peptic disease, and arteriovenous malformations can cause upper or lower GI tract bleeding in neonates.

In infants up to 2 years of age, peptic disease or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced gastric injury causes hematemesis; esophageal varices also occur in this age group with portal hypertension caused by conditions such as biliary atresia. After this age, peptic disease and esophageal varices continue to be common causes of hematemesis. Rectal bleeding in older children is likely to be caused by a juvenile polyp, IBD, Meckel’s diverticulum, or nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. The presence of diarrhea and mucus in the stool particularly suggests IBD or bacterial dysentery. When rectal bleeding is massive and painless, Meckel’s diverticulum is a common cause. The bleeding caused by polyps or lymphoid hyperplasia can be significant, but seldom is profuse enough to result in changes in pulse or blood pressure (Table 126-10).

TABLE 126-10 Causes and Distinguishing Characteristics of Gastrointestinal Bleeding

| Age | Type of Bleeding | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| NEWBORN | ||

| Ingested maternal blood* | Hematemesis or rectal, large amount | Apt test indicates adult hemoglobin is present |

| Peptic disease | Hematemesis, amount varies | Blood found in stomach on lavage |

| Coagulopathy | Hematemesis or rectal, bruising, other sites | History of home birth (no vitamin K) |

| Allergic colitis* | Streaks of bloody mucus in stool | Eosinophils in feces and in rectal mucosa |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | Rectal | Sick infant with tender and distended abdomen |

| Duplication cyst | Hematemesis | Cystic mass in abdomen on imaging study |

| Volvulus | Hematemesis, hematochezia | Acute tender distended abdomen |

| INFANCY TO 2 YEARS | ||

| Peptic disease | Usually hematemesis, rectal possible | Epigastric pain, coffee-ground emesis |

| Esophageal varices | Hematemesis | History or evidence of liver disease |

| Intussusception* | Rectal bleeding | Crampy pain, distention, mass |

| Meckel diverticulum* | Rectal | Massive, bright red bleeding; no pain |

| Bacterial enteritis* | Rectal | Bloody diarrhea, fever |

| NSAID injury | Usually hematemesis, rectal possible | Epigastric pain, coffee-ground emesis |

| >2 YEARS | ||

| Peptic disease | See above | See above |

| Esophageal varices | See above | See above |

| NSAID injury* | See above | See above |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Usually rectal | Crampy pain, poor weight gain, diarrhea |

| Bacterial enteritis* | Rectal | Fever, bloody stools |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | Rectal | History of antibiotic use, bloody diarrhea |

| Juvenile polyp | Rectal | Painless, bright red blood in stool; not massive |

| Meckel diverticulum* | See above | See above |

| Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia | Rectal | Streaks of blood in stool, no other symptoms |

| Mallory-Weiss syndrome* | Hematemesis | Bright red or coffee-ground, follows retching |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Rectal | Thrombocytopenia, anemia, uremia, diarrhea |

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Distinguishing Features

Red substances in foods or beverages occasionally can be mistaken for blood. A test for occult blood is worth performing whenever the diagnosis is in doubt.

Blood may not be coming from the GI tract. The clinician should ask about cough, look in the mouth and nostrils, and examine the lungs carefully to exclude these sources of hematemesis. Blood in the toilet or diaper may be coming from the urinary tract, vagina, or even a severe diaper rash. If the bleeding is GI, the clinician needs to determine whether it is originating high in the GI tract or distal to the ligament of Treitz. Vomited blood is always proximal. Rectal bleeding may be coming from anywhere in the gut. When dark clots or melena are seen mixed with stool, a higher location is suspected, whereas bright red blood on the surface of stool probably is coming from lower in the colon. When upper GI tract bleeding is suspected, a nasogastric tube may be placed and gastric contents aspirated for evidence of recent bleeding in the proximal gut.

The location and hemodynamic significance of the bleeding can also be assessed by history and examination. The parents should be asked to quantify the bleeding. Details of associated symptoms should be sought. The vital signs should be evaluated and assessment for orthostatic changes performed when bleeding volume is large. Pulses, capillary refill, and pallor of the mucous membranes should be assessed. Laboratory assessment and imaging studies should be ordered as indicated (Table 126-11).

TABLE 126-11 Evaluation of Gastrointestinal Bleeding

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION

All Patients

Evaluation of Bloody Diarrhea

Evaluation of Rectal Bleeding with Formed Stools

INITIAL RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION

All Patients

EVALUATION OF HEMATEMESIS

Evaluation of Bleeding with Pain and Vomiting (Bowel Obstruction)

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CBC, complete blood count; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; GI, gastrointestinal.

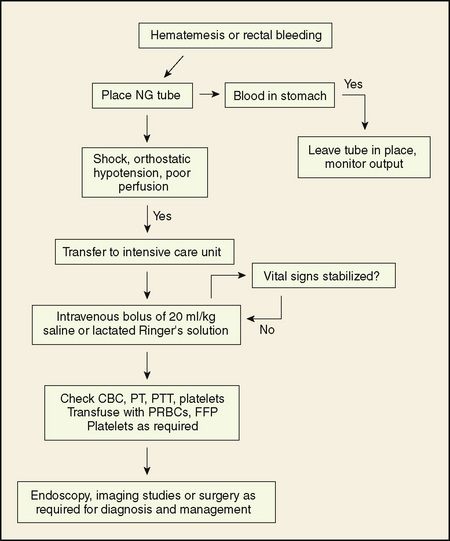

Treatment

Treatment of GI bleeding should begin with an initial assessment, rapid stabilization of shock, if present, and a logical sequence of diagnostic tests. When a treatable cause is identified, specific therapy should be started. In many cases, the amount of blood is small, and no resuscitation is required. For children with large volume bleeds, the ABCs of resuscitation (check airway, breathing, and circulation) should be addressed first (see Chapters 38 and 40). Oxygen should be administered and the airway protected with an endotracheal tube if massive hematemesis is present. Two large bore IV lines are needed to restore adequate circulation with fluid boluses or transfuse with packed red blood cells as required. Frequent reassessment is needed (Fig. 126-2).