Chapter 38 Parenteral products

Introduction

Parenteral products are dosage forms that are delivered to the patient by a route outwith the alimentary canal. The parenteral route of administration is often used for drugs that cannot be given orally. This may be because of patient intolerance, the instability of the drug, or poor absorption of the drug if given by the oral route. In practice, parenteral products are often regarded as dosage forms that are implanted, injected or infused directly into vessels, tissues, tissue spaces or body compartments. From the site of administration the drug is then transported to the site of action. With developing technology, parenteral therapy is being used outside the hospital or clinic environment. Patients are increasingly using it at home and in the workplace, allowing them to administer their own medication.

Parenteral therapy is used to:

Parenteral injections are either administered directly into blood for a fast and controlled effect or into tissues outside the blood vessels for a local or systemic effect. An injection can be administered intravenously to rapidly increase the concentration of drug in the blood plasma, but the concentration soon falls due to the reversible transfer of the drug from blood plasma into body tissues, a process known as distribution. The drug concentration remaining in the blood plasma is affected both by the administered dose and by the quantity of drug transferred into body tissues. Thereafter, there is a slower decrease in the drug concentration due to irreversible excretion and metabolism. An intravenous infusion administers a large volume of fluid at a slow rate and ensures that the drug enters the general circulation at a constant rate. In this procedure, the drug concentration in the blood plasma rises soon after the start of the infusion and achieves a steady state when the rate of drug addition equals the rate of drug loss. When infusion is stopped, elimination of the drug from the body by metabolism and/or excretion generally follows first-order kinetics.

Following subcutaneous and intramuscular injection there is a delay in the systemic effects of the drug. The delay is due to the time for the drug to first pass through the epithelial cells and basement membrane that forms the walls of the capillaries before entering into the blood. This occurs by passive diffusion that is promoted by the concentration gradient across the capillary wall. Other factors are also important, including the permeability characteristics and the number of capillaries in the area. Most plasma solutes pass freely across the capillary walls, while water-soluble substances such as glucose and amino acids pass through intercellular aqueous spaces of the capillary wall. After passing through the capillary wall the drug concentration in the blood plasma rises to a peak level and then falls due to distribution to the tissues followed by metabolism and excretion.

Administration procedures

Intravenous injections and infusions

Administration by this route provides strict control of the drug concentration in the circulating blood. The vein that is selected for administering the formulation depends on several factors. These include the size of the delivery needle or catheter, the type and volume of fluid to be administered and the rate of administering the fluid. The fluids are administered into a superficial vein, commonly on the back of the hand or in the internal flexure of the elbow (see Fig. 21.1). The intravenous route is widely used to administer parenteral products, but it must not be used to administer water-in-oil emulsions or suspensions.

Subcutaneous injections

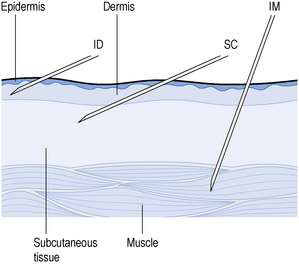

These are injected into the loose connective and adipose tissue immediately beneath the skin (Fig. 38.1). Typically, the volume injected does not exceed 1 mL. Injection sites include the abdomen, the upper back, the upper arms and the lateral upper hips. This route is used if the medicine cannot be administered orally. The drugs are more rapidly and predictably absorbed than when administered by the oral route. Following administration, the site of the injection, the body temperature, age of the patient and the degree of massaging of the injection site affect drug distribution. However, absorption of the drug after subcutaneous injection is slower and less predictable than when administered by the intramuscular route.

Intramuscular injections

Small-volume aqueous solutions, solutions in oil and suspensions are administered directly into the body of a relaxed muscle (see Fig. 38.1). Several muscle sites are used for these injections, including the gluteal muscle in the buttock, the deltoid muscle in the shoulder and the vastus lateralis of the thigh. In adults, the gluteal muscle is often used as larger volumes can be tolerated. In infants and small children, the vastus lateralis of the thigh is usually more developed than other muscle groups and is thus used. For rapid absorption of the medicament, the deltoid muscle in the shoulder is often used.

Other routes of parenteral administration are described below.

Intradermal injections

A volume of about 0.1 mL is injected into the skin between the epidermis and the dermis. Absorption from intradermal injections is slow. This route is often used for diagnostic tests for allergy or immunity. It is also used to administer some vaccines.

Intra-arterial injections

The drug is administered directly into an artery. Owing to the fast flow of blood in the artery it is likely that the drug will be rapidly dispersed throughout the blood system. However, manipulative difficulties restrict the use of intra-arterial injections but drugs can be administered by this route to target a specific organ or tissue that is served by the artery.

Intracardiac injections

These are aqueous solutions that are administered in emergency directly into a ventricle or the cardiac muscle for a local effect.

Intraspinal injections

These are aqueous solutions that are injected in volumes less than 20 mL into particular areas of the spinal column. They are categorized as intrathecal, subarachnoid, intracisternal, epidural and peridural injections. The specific gravity of these injections may be adjusted to localize the site of action of the drug.

Products for parenteral use

Parenteral products are sterile formulations that are administered into the body by various routes including injection, infusion and implantation.

Injections

These are subdivided into small- and large-volume parenteral fluids. Small-volume parenterals are sterile, pyrogen-free injectable products. They are packaged in volumes up to 100 mL. Small-volume parenteral fluids are packed as:

Single-dose ampoules

Most small-volume parenterals are currently packaged as either ampoules or vials. Glass ampoules are thin-walled containers made of Type I borosilicate glass (see Fig. 27.3). Injections packaged in glass ampoules are manufactured by filling the product into the ampoules, which are then heat sealed. To achieve the quality required of these products, the packaged solution must be sterile and practically free of particles. These products are typically prepared in clean room conditions (see Ch. 29). However, the great concern with using glass ampoules relates to the hazards of opening them because the product may become contaminated with glass particles. Opening is easier with glass ampoules with a weakened neck. This is achieved by applying a ceramic paint ring to the ampoule neck. The paint, after a process of heat baking, has the effect of weakening the neck. Even though the subsequent opening of the ampoules is physically easier, a large number of glass particles still contaminate the product. Another ampoule design has a score on the glass at the ampoule neck with a painted dot marker on the opposing side. These are known as one-point cut ampoules. They are easier to open, but glass particles continue to be released when they are opened.

Plastic ampoules are prepared, filled and sealed by a procedure known as blow–fill–seal. This is a four-step continuous procedure in which granules of plastic are heated to a semi-solid state. The plastic is then blow moulded and formed into ampoules. These containers are filled with the product and immediately sealed. This system is only used to package simple solutions. The plastic may take up drug components from the product. When the ampoule is opened by rotating the integral plastic closure, few particles are released into the solution.

Ampoules should have a reliable seal that can be readily leak tested. A good seal will not deteriorate during the lifetime of the product. Medicines packaged in ampoules are intended for single use only. As a result, these products do not contain chemical antimicrobial preservatives. The ampoule must also contain a slight excess volume of product. This is necessary to allow the nominal injection volume to be drawn into a syringe.

Multiple-dose vials

These are composed of a thick-walled glass container that is sealed with a rubber closure. The closure is kept in position by an aluminium seal that is crimped to the neck of the glass vial (see Fig. 27.4). These closures are then covered with a plastic cap. The cap is removed before a needle, attached to a syringe, is inserted through the rubber closure to withdraw a dose of product. The contents of the vial may be removed in several portions.

The glass vial packaging system has the advantage of increased dose flexibility and decreased costs per unit dose. There are also certain disadvantages with the use of glass vials. Fragments of the closure may be released into the product when the needle is inserted through the closure. There is also the risk of interaction between the product and the closure. Repeated withdrawal of injection solution from these containers increases the risk of microbial contamination of the product. These products must, therefore, contain an antimicrobial preservative unless the medicine itself has antimicrobial activity. An example of such a multidose product is insulin. Each dose is withdrawn from the vial when required and administered by the patient.

Prefilled syringes

With these devices, the injection solution is aseptically filled into sterile syringes. The packed solution has a high level of sterility assurance and does not contain an antimicrobial preservative. The final product is available for immediate use. Prefilled syringes are expensive and so only limited products are packaged in this way.

Administration of small-volume parenteral products

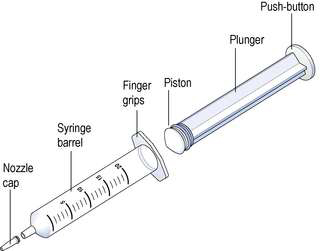

Hypodermic syringes and needles are extensively used for administering small volumes of parenteral formulations to the patient. These syringes have been sterilized by ethylene oxide gas or, occasionally, by gamma irradiation following packaging. Various sizes of hypodermic syringes are available. They are composed of a barrel, having a graduated scale, together with a plunger and a headpiece, known as a piston (Fig. 38.2). These components are often made of polypropylene, although the piston could be made of medical grade rubber.

Formulation of parenteral products

Vehicles for injections

The drug is generally present in an injection in low concentration. The vehicle provides the highest proportion of the formulation and should not be toxic nor have any therapeutic activity.

Mains water often contains a wide variety of contaminants such as electrolytes, organisms and particulate matter, and dissolved gases, such as carbon dioxide and chlorine. The wide variety of these contaminants causes a problem in the preparation of water for use in injections. This is called ‘water for injections’ and must be used as the vehicle for parenteral products. It is often used to prepare ophthalmic products but these could be made using purified water.

Water for injections

Water for injections is the most extensively used vehicle in parenteral formulations. Water for injections is well tolerated by the body and ionizable electrolytes readily dissolve in water. Water for injections must be free of pyrogens. It must also have a high level of chemical purity. The British Pharmacopoeia (BP; 2007) considers that water for injections can only be prepared by distillation in order to produce a consistent supply of the required quality of water.

Preparation of water for injections

The usual method of preparing water for injections in Europe and North America is distillation. While other processes can achieve a similar quality of product, these alternative systems cannot produce a consistent water quality. The source water used in the preparation of water for injections by distillation is usually potable water. This water varies in quality and may be contaminated with dissolved gases, suspended minerals and organic substances, mineral salts, chemicals, endotoxins and microorganisms. The high standard required of water for injections is only achieved if the quality of the source water is improved by suitable pretreatment before it is supplied as feed water for final processing. The pretreatment of the source water usually involves:

The water is then treated by reverse osmosis to yield purified water. This water is often used as the feed water for distillation and has a low silica content and a low total organic carbon content. A wide variety of designs of still are used in the production of water for injections. These stills are typically made of stainless steel, although chemically resistant glass could be used.

The single effect still is used to produce volumes less than 90 L/h. This usually fulfils the demands of small-scale production as required by a hospital pharmacy. The single effect still requires de-ionized feed water and has three main structural components:

When this still is functioning, the feed water in the horizontal evaporator is heated. Steam is produced at atmospheric pressure and at slow velocity. Some steam will condense before it enters a vertical vapour-liquid disengaging unit that is attached to the horizontal evaporator. Baffle plates at the base of the vapour-liquid unit reduce the risk of water droplets being carried in the steam into this unit. The water droplets and the non-volatile impurities are returned to the water in the evaporator. The vapour-liquid disengaging unit often contains a centrifugal device that spins the steam as it rises in this unit. This has the effect of throwing entrapped water droplets in the steam onto the wall of this vertical cylindrical section where it condenses and returns to the evaporator. Only pure steam exits from this unit into the condenser where the heat of vaporization is removed and converts the water vapour to the liquid distillate. Only stills designed to produce high purity water may be used in the production of water for injections.

In operation, the first portion of the distillate must be discarded. The remainder is collected in a suitable storage vessel. Freshly collected distillate is usually free of microbial contaminants and should contain not more than 0.25 international units of endotoxin per mL as determined by the bacterial endotoxin test (see later). However, the distillate is regularly sampled and tested for microbial contamination. It is acceptable if there are fewer than 10 organisms per 100 mL present at any instance; no Pseudomonas bacteria should be present. To ensure that the distillate is of a suitable purity, the electrical conductivity of the distillate is measured. This measurement is used as an indicator of the quality of ionizable materials in the collected water. The electrical conductance should be less than 1.1 mS/cm when measured at 20°C. However, the measurement of electrical conductivity alone as an indicator of water quality can be misleading, as it does not detect silica in the distillate. To conform with the quality standards of the BP (2007) and the European Pharmacopoeia (EP; 2007), the distillate will also have the following quality limits:

| Total organic carbon | Not more than 0.5 mg per litre |

| Chlorides | Not more than 0.5 parts per million (p.p.m.) |

| Ammonium | Not more than 0.2 p.p.m. |

| Nitrates | Not more than 0.2 p.p.m. |

| Heavy metals | Not more than 0.1 p.p.m. |

| Oxidizable substances | Not more than 5 p.p.m. |

| pH | 5.0–7.0 |

Care is required in handling the freshly collected distillate as it is subject to microbial contamination during storage and distribution. Two systems are commonly used for the storage of water for injections: batch storage and dynamic storage.

Batch storage

With this system the water for injections is stored as a batch of discrete unit volumes which may be sterilized. Quality control tests are performed on this batch. Only after the batch is identified as being of suitable quality is it released for use. This system provides maximum product accountability before use. It is, however, an expensive storage system.

Dynamic storage

With this system the storage tank is a surge tank, usually made of quality polished stainless steel. As the level of water for injections in the tank falls then more water for injections is produced and filled into the tank. The fresh water for injections mixes with water remaining in the tank. This system is cheaper and simpler to operate than batch storage. However, it does lack batch accountability and the water may become contaminated through corrosion of the steel tank. Owing to the potential problem with Gram-negative bacterial contamination, it is important that the distillate is stored at 80°C to prevent bacterial growth. Heating the water in the tank is achieved with a steam-heated jacket around the tank.

Surge tanks require sterilization at timed intervals. They are fitted with a filter vent used to equilibrate the tank pressure during filling and emptying the tank. The filter prevents airborne bacterial contamination of the water for injections within the tank.

Distribution

A loop distribution system may be used to deliver the water for injections to the point of use. The water in the distribution system can become contaminated with organisms. As a result, the water in the stainless steel pipes is constantly circulated from the tank to avoid stagnation and to maintain the temperature. This distribution system has one major disadvantage in that the point of use may not require high-temperature water. Thus a cooling system may be fitted close to the point of use. Microbial growth may then occur in the cooled water.

Sterilized water for injections

This is prepared by packing a volume of water for injections in sealed containers. These containers are then moist-heat sterilized which yields a sterile product that remains free of pyrogens. Sterilized water for injections is used to dissolve or dilute parenteral preparations before administration to the patient.

Pyrogens

Water is potentially the greatest source of pyrogens in parenteral products. Untreated pyrogenic water is contaminated with pyrogens and these must be removed before the water can be used in parenteral products. This is achieved in the preparation of water as a vehicle for injections by distillation in the UK. Pyrogens are fever-producing substances. The injection of distilled water may produce a rise in body temperature if it contains pyrogens, while water that is free of this effect is described as apyrogenic.

Microbial pyrogens arise from components of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, fungi and viruses. Non-microbial pyrogens, such as some steroids and plasma components, also produce a pyrogenic response if injected. The most important pyrogens in pharmacy products are high molecular weight endotoxins that are found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. Therefore endotoxins potentially exist in all situations harbouring bacteria.

Freshly prepared parenteral products must not be contaminated with organisms that could produce pyrogens. They must be prepared in conditions that reduce microbial contamination because bacteria contaminating aqueous solutions can release endotoxins. Contaminated solutions will become more pyrogenic with the passage of time. Therefore, these products must be sterilized shortly after preparation.

Endotoxins produce significant physiological changes when injected. Their detection and elimination is very important for manufacturers of parenteral products.

Nature of endotoxins

Endotoxins isolated from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria are composed of three areas. The inner region is composed of lipid A that is linked to a central polysaccharide core. This polysaccharide core is joined to long projections known as the O-antigenic side chains. Lipid A is responsible for most of the biological activity of endotoxin. By itself it is not very soluble in water. However, it is joined to a core polysaccharide by an eight-carbon sugar that acts as a solute carrier for the lipid A in aqueous solutions.

The molecular weight of endotoxin is important in determining its biological activity. In a pure aqueous environment, endotoxin has a relative molecular mass of about 106. This is equivalent to the relative molecular mass of a virus particle and is the most common size of endotoxin found in large-volume parenteral formulations. In the presence of magnesium and calcium, the endotoxin forms bilayer sheets or vesicles with a diameter of about 0.1 μm. These small structures can easily pass through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. This size of filter is commonly used in the production of pharmacy products.

Biological activity of pyrogens

The injection of endotoxins and other pyrogens can produce many physiological effects. The most important arising from the use of pharmacy products is the pyrogenic effect, where the lipid A directly affects the thermoregulatory centres in the brain. At high dose levels, endotoxin will also:

As pyrogens can produce these toxic effects, they should never be knowingly injected. Their detection and elimination is very important for the production of parenteral products. The contamination of large-volume parenteral solutions with pyrogens is especially serious, owing to the large volumes that are administered to seriously ill patients.

Although endotoxins are the predominant pyrogen in parenteral formulations, other pyrogenic substances also exist. These agents include peptidoglycan, from Gram-positive bacteria, and bacterial exotoxins, as evidenced by the erythrogenic response produced by Streptococcus group A organisms which cause the skin to turn red. Viruses induce a pyrogenic response that often appears like the fever induced by the common cold virus. Moulds and yeasts also produce a pyrogenic effect following intravenous injection.

Tests for pyrogens

The rabbit test included in the BP (2007) and in the EP (2007) is very similar to the original rabbit test included in the 1948 edition of the BP. However, in recent times, alternative tests for bacterial endotoxins have been extensively used. The rabbit test that is used to identify the presence of a wide range of pyrogens does have problems for testing pharmacy products. It is an expensive and slow test that is difficult to perform even in specialized test centres. The bacterial endotoxin test is a specific test for endotoxins of bacterial origin. Bacterial endotoxin is the main pyrogen found in parenteral products and the test is carried out on both the components and the final parenteral products.

Bacterial endotoxin tests

This test, as detailed in Appendix XIV of the BP (2007), is commonly referred to as the limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) test. It detects or quantifies endotoxins from Gram-negative bacteria. The BP test allows the use of a lysate of amoebocytes from either the American or Japanese horseshoe crab. Not surprisingly, however, in practice the lysate used in tests in Europe and North America is obtained from amoebocytes of the American horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus, while the lysate of the Japanese crab (Tachypleus tridentatus) is used in tests carried out in Asia. Although six tests are detailed in the BP (2007), these tests can be grouped into one of three types, known as: the gel clot end point, the turbidimetric test and the kinetic chromogenic test. The gel clot end point is based on the formation of a solid gel clot. It is an in vitro test for bacterial endotoxins that does have some advantages, as it is cheap, rapid, simple to perform and sensitive to low endotoxin concentrations. This test is often used by hospital and small-scale manufacturers and is used as a definitive test if doubt exists regarding results obtained by the other test methods.

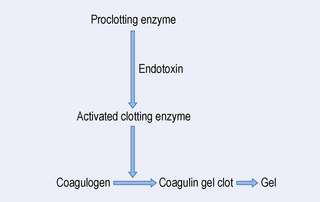

With the gel clot procedure, a solution containing the endotoxin is added to a solution of the lysate. The reaction requires a proclotting enzyme system and a clottable protein coagulogen that are provided by the lysate. The reaction that takes place is shown in Figure 38.3. The rate of this reaction is affected by several factors, including the concentration of endotoxin, the pH and the temperature. In the test procedure, the lysate is mixed with an equal volume of the test solution in a depyrogenated container, such as a glass tube. The tube is then incubated undisturbed at 37°C for a period of about 60 minutes. The test is a pass or fail test. The end point is identified by gently inverting the glass tube. A positive result is indicated by the formation of a solid clot of coagulin. This clot does not disintegrate when the tube is inverted. A negative result is indicated if no gel clot has been formed. This test needs appropriate positive and negative controls. For a positive control, a known concentration of endotoxin is added to the lysate alone and then repeated with a product sample. As a negative control, water that is free of endotoxin is added to the lysate. All the controls must produce appropriate results for the test to be valid. The sensitivity of the assay is limited by the sensitivity of the lysate used in the test. The gel clot test will detect between 0.02 and 1.0 endotoxin units per millilitre. Some recently developed biopharmaceuticals have shown similar activity to endotoxin in this and the other endotoxin tests. Before this test is carried out, it is necessary to determine that:

The turbidimetric test is used in the testing of water systems and for testing simple pharmacy products. The test measures the opacity change in the LAL test due to the formation of insoluble coagulin. An increase in the endotoxin concentration produces a proportional increase in opacity due to the precipitation of the clottable protein coagulin.

The kinetic chromogenic test is an automated test used by commercial parenteral manufacturers to test large numbers of complex products. The test gives an accurate result over a wide range of endotoxin concentrations. The test measures the colour change induced by the release of the chromogenic chemical para-nitroanilide. This is released as a by-product of the clotting reaction during the LAL test. The quantity of para-nitroanilide produced is directly proportional to the endotoxin concentration.

Pyrogen testing

The BP pyrogen test involves measuring the rise in body temperature of healthy mature rabbits. This temperature rise is recorded after the rabbits have been intravenously injected with a sterile solution of the test substance. The environment and the equipment used in the test are detailed in the BP (2007). This test can only be carried out where the rabbits can tolerate the test product.

The test itself is preceded by a preliminary test to identify and exclude any animal with an unusual response to the trauma of the injection. With the preliminary test, a warmed pyrogen-free saline solution is injected into the rabbits. The temperature of the rabbits is recorded from 90 minutes before the test to 3 hours after the injection, as specified in the BP (2007). The fever response in the rabbits after the injection with pyrogens follows a biphasic response. After the injection, there is a lag time of about 15–18 minutes, which is followed by a rapid temperature rise to a peak within 2 hours. The temperature then falls and is followed by a second rise in temperature. This returns to normal after 6–9 hours. False-positive temperature increases occur with rabbits as a result of:

The rabbits may develop a resistance to pyrogens. As a result, they are tested at specified time intervals.

Depyrogenation

Depyrogenation is the elimination of all pyrogens from the production materials, solutions and equipment. It is achieved by either removal or inactivation of the pyrogens. The main method of preventing pyrogens contaminating parenteral products is strict control of the ingredients used. That is solvents, raw materials, packaging materials and equipment should not be contaminated with pyrogens.

A simple method of removing small amounts of pyrogens from surfaces such as packaging components is by rinsing the surfaces with non-pyrogenic water. As pyrogens are non-volatile, distillation is the principal method of avoiding contamination of water used in parenteral products. This is achieved by positioning a trap, fitted with baffles, in the still. The trap removes the droplets of water by impingement and prevents pyrogens being carried over into the distillate. However, the freshly collected distillate that is initially pyrogen-free water can become contaminated with organisms and pyrogens if stored for more than 4 hours at 22°C. To avoid microbial growth in this water, it must be sterilized soon after collection or stored at high temperatures to suppress microbial growth. Pyrogens can be removed from solutions by ultrafiltration that separates pyrogens by a process based on their relative molecular mass. This specialized system has been used to depyrogenate antibiotic products during their commercial production. These filters are different from the 0.22 μm filters often used in pharmacy production.

Various methods are used to inactivate pyrogens including heat treatment, acid–base hydrolysis and oxidation. High temperature is widely used to incinerate pyrogens especially for glassware, thermostable equipment and formulation components. Dry heat at 250°C for 30 minutes is normally used. The commonly used dry or moist heat sterilization cycles (see Aulton 2007) will not greatly reduce the pyrogen burden of parenteral products.

Non-aqueous solvents

Water-miscible cosolvents, such as glycerin and propylene glycol, are used as vehicles in small-volume parenteral fluids. They are used to increase the solubility of drugs and to stabilize drugs degraded by hydrolysis.

Metabolizable oils are used to dissolve drugs that are insoluble in water. For example steroids, hormones and vitamins are dissolved in vegetable oils. These formulations are administered by intramuscular injection.

Additives

Various additives, such as antimicrobial agents, antioxidants, buffers, chelating agents and tonicity-adjusting agents, are included in injection formulations. Their purpose is to produce a safe and elegant product. Both the types and amounts of additives to be included in formulations are given in the appropriate monograph in the BP (2007).

Antimicrobial agents

These are added to products that are packaged in multiple-dose vials. They are not used in large-volume injections or if the drug formulation itself has sufficient antimicrobial activity (such as Methohexital Sodium Injection). Antimicrobial agents are added to inhibit the growth of microbial organisms that may accidentally contaminate the product during use. The antimicrobial agents must be stable and effective in the parenteral formulation. Because they are effective in the free form, their activity can be greatly reduced by interaction with components of the injection. Rubber closures have been shown to take up antimicrobial preservatives from the injection solution. Preservative uptake is more significant with natural and neoprene rubber and much less with butyl rubber closures.

There is concern about the toxic effects of injections containing preservatives. As a result, a low but effective antimicrobial concentration is used in injections. Challenging the product with selected organisms can test the effectiveness of antimicrobial agents. The test procedure will evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the preservative in the packaged product. The test procedure is detailed in BP 2007. Table 38.1 gives details for some commonly used preservatives.

Table 38.1 Examples of antimicrobial preservatives used in aqueous multiple dose injections

| Antimicrobial preservative | Concentration (% w/v) |

| Benzyl alcohol | 1–2 |

| Chlorocresol | 0.1–0.3 |

| Cresol | 0.25–0.5 |

| Methyl hydroxybenzoate | 0.1 |

| Phenol | 0.25–0.6 |

| Thiomersal | 0.01 |

Antioxidants

Many drugs in aqueous solutions are easily degraded by oxidation. Small-volume parenteral products of these drugs often contain an antioxidant. Bisulphites and metabisulphites are commonly used antioxidants in aqueous injections. Antioxidants must be carefully selected for use in injections to avoid interaction with the drug. Antioxidants have a lower oxidation potential than the drug and so are either preferentially oxidized or block oxidative chain reactions. Injection formulations may, in addition to antioxidants, also contain chelating agents. Chelating agents such as EDTA or citric acid remove trace elements which catalyse oxidative degradation.

Buffers

The ideal pH of parenteral products is pH 7.4. If the pH is above pH 9, tissue necrosis may result, while below pH 3, pain and phlebitis in tissues can occur.

Buffers are included in injections to maintain the pH of the packaged product. Changes in pH can arise through interaction between the product and the container. However, the buffer used in the injection must allow the body fluids to change the product pH after injection. Acetate, citrate and phosphate buffers are commonly used in parenteral products.

Tonicity-adjusting agents

Isotonic solutions have the same osmotic pressure as blood plasma and do not damage the membrane of red blood cells. Hypotonic solutions have a lower osmotic pressure than blood plasma and cause blood cells to swell and burst because of fluids passing into the cells by osmosis. Hypertonic solutions have a higher osmotic pressure than plasma; as a result the red blood cells lose fluids and shrink. Following the administration of an injection it is important that tissue damage and irritation are minimized and haemolysis of red blood cells is minimized. Thus, the BP (2007) states that aqueous solutions for large-volume infusion fluids, together with aqueous fluids for subcutaneous, intradermal and intramuscular administration, should be made isotonic. Intrathecal injections must also be isotonic to avoid serious changes in the osmotic pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid. Aqueous hypotonic solutions are made isotonic by adding either sodium chloride, glucose or, occasionally, mannitol. The latter two agents are incompatible with some drugs. If the solution is hypertonic, it is made isotonic by dilution.

Some components of injections, such as buffers and antioxidants, affect the tonicity. Other components, such as preservatives, which are present in low concentration, have little effect on the tonicity.

Injection solutions are often made isotonic with 0.9% sodium chloride solution. The amount of solute, or the required dilution necessary to make a solution isotonic, can be determined from the freezing point depression. The freezing point depression of blood plasma and tears is −0.52°C. Thus solutions that freeze at −0.52°C have the same osmotic pressure as body fluids. Hypotonic solutions have a smaller freezing point depression and require the addition of a solute to depress the freezing point to −0.52°C.

The amount of adjusting substance added to these solutions may be calculated from the equation:

where W = percentage concentration of adjusting substance in the final solution, a = freezing point depression of the unadjusted hypotonic solution, b = freezing point depression of a 1% weight in volume (w/v) concentration of the adjusting substance.

An extensive list of freezing point depression values is detailed in Table 6 (pp 53–64) in the chapter ‘Solution properties’ in the 12th edition of the Pharmaceutical Codex (1994) (Example 38.1).

Example 38.1

A 100 mL volume of a 2% w/v solution of glucose for intravenous injection is to be made isotonic by the addition of sodium chloride.

A 1% w/v solution of glucose depresses the freezing point of water by 0.1°C and a 1% solution of sodium chloride depresses the freezing point of water by 0.576°C.

The depression of freezing point of the unadjusted solution of glucose (a) will therefore be:

A 1% w/v solution of sodium chloride depresses the freezing point of water by 0.576°C (b).

Substituting these values for a and b in the above equation:

The intravenous solution thus requires the addition of 0.555 g of sodium chloride per 100 mL volume to make it isotonic with blood plasma.

Other methods that are used to estimate the amount of adjusting substances required to make a solution isotonic include:

Details of these methods are given in the chapter ‘Solution properties’ (pp 64–67) in the 12th edition of the Pharmaceutical Codex (1994).

Units of concentration

The concentration of the components in parenteral products may be expressed in various ways (see also Ch. 26):

During the formulation of injections and infusions, the units of interest are the ions of electrolytes and the molecules of non-electrolytes. For molecules, 1 millimole (mmol) is the weight in milligrams corresponding to its relative molecular mass. A mole of an ion is its relative atomic mass weighed in grams. The number of moles of each of the ions of a salt in solution depends on the number of each ion in the molecule of the salt (Example 38.2).

Example 38.2

Sodium chloride has one sodium and one chloride ion. Thus, 1 mole of sodium chloride provides 1 mole of both sodium and chloride ions. The weight of sodium chloride which provides a 1 mmol quantity is 58.5 mg. This weight corresponds to its relative molecular mass and provides 1 mmol of both sodium and chloride ions.

Magnesium chloride has one magnesium and two chloride ions. The weight in milligrams that provides 1 mmol of magnesium and 2 mmol of chloride ions is 203 mg. This weight corresponds to the relative molecular mass of this salt. The quantity of salt in milligrams containing 1 mmol of a particular ion can be determined by dividing the relative molecular mass of the salt by the number of the particular ions that it contains. Weights of common salts that provide 1 mmol are given in Table 4 in the chapter ‘Solution properties’ (pp 49–50) in the 12th edition of the Pharmaceutical Codex (1994).

Conversion equations

Useful conversion equations include the following:

| mg per litre | = W × M |

| grams per litre | = (W × M)/1000 |

| % w/v | = (W × M)/10 000 |

where W = the number of milligrams of salt containing 1 mmol of the required ion, M = the number of millimoles per litre (Examples 38.3-38.5).

Example 38.3

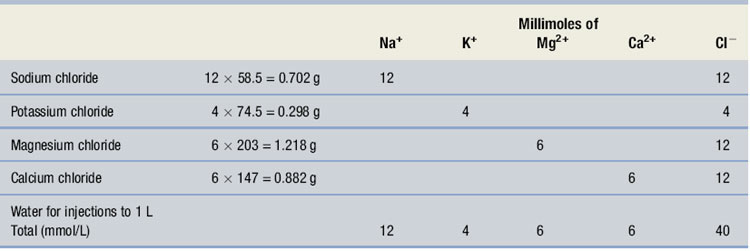

Calculate the quantities of salts required for the following electrolyte solution:

| Sodium | 12 mmol |

| Potassium | 4 mmol |

| Magnesium | 6 mmol |

| Calcium | 6 mmol |

| Chloride | 40 mmol |

| Water for injections | to 1 L |

From Table 4 in the Pharmaceutical Codex (1994), 4 mmol of potassium ion is provided by 4 × 74.5 mg of potassium chloride, which also yields 4 mmol of chloride ions. 6 mmol of magnesium ions is provided by 6 × 203 mg of magnesium chloride, which also yields 2 × 6 = 12 mmol of chloride ions as there are two chloride ions in the molecule. 6 mmol of calcium ions is provided by 6 × 147 mg of calcium chloride, which also yields 12 mmol of chloride ions as there are two chloride ions in the molecule. 12 mmol of sodium ions is provided by 12 × 58.5 mg of sodium chloride that also yields 12 mmol of chloride. The formula can, therefore, be shown as in Table 38.2. It should be noted that the charges on the anions and cations are equally balanced.

Table 38.2 The formula for Example 38.3

Example 38.4

Calculate the number of millimoles of dextrose and sodium ions in 1 litre of sodium chloride and dextrose injection containing 5% anhydrous dextrose and 0.9% w/v of sodium chloride.

Use the conversion equation for % w/v calculations:

Example 38.5

Calculate the number of millimoles of magnesium and chloride ions in 1 litre of a 2% solution of magnesium chloride.

Each mole of magnesium chloride provides 1 mole of magnesium ions and 2 moles of chloride ions. Thus, 1 litre of the solution contains 9.85 mmol of magnesium ions and 19.7 mmol of chloride ions.

Special injections

These are more complex formulations than solutions for injection.

Suspensions

Commonly, suspensions for injection contain less than 5% of drug solids with a mean particle diameter within the range 5–10 μm. Owing to the presence of particles in these formulations, these injections are more difficult to process and sterilize than solutions for injection. During the manufacture of suspensions for injection, the components are prepared and sterilized separately. They are then aseptically combined (see Ch. 29). The final product cannot be filter sterilized owing to the presence of particles in the formulation. Powders for use in sterile suspensions can be sterilized by gas, but gas residues must be avoided.

Dried injections

With these products the dry sterile powder is aseptically added to a sterile vial. Alternatively, a sterile filtered solution can be freeze dried in a vial. The dry drug powder is reconstituted with a sterile vehicle before use.

Non-aqueous injections

Drugs that are insoluble in an aqueous vehicle can be formulated in solution using an oil as the vehicle. These formulations are less common than aqueous suspensions. Several oils are used in these formulations, including arachis oil and sesame oil, which are easily metabolized. These viscous injections give a depot effect with slow release of the drug and are administered by intramuscular injection.

Large-volume parenteral products

These are parenteral products that are packed and administered in large volumes. They are formulated as single-dose injections that are administered by intravenous infusion. They are sterile aqueous solutions or emulsions with water for injections as the main component. It is important that they are free of particles. During the administration of these fluids, additional drugs are often added to the fluids (see Ch. 40). This may be carried out by the injection of small-volume parenteral products to the administration set of the fluid, or by the ‘piggyback’ method. In this procedure a second, but smaller, volume infusion of an additional drug is added to the intravenous delivery system.

Large-volume parenteral products include:

All of these products have direct contact with blood or are introduced into a body cavity. Large-volume parenterals are variously formulated and packaged and have been used to: Large-volume parenterals must be terminally heat sterilized. While water for injections is the main component of these products, they also incorporate other ingredients including:Most large-volume parenteral fluids are clear aqueous solutions, except for the oil-in-water emulsions. The production of emulsions for infusion is highly specialized as they are destabilized by heat. This results in production difficulties, particularly because the size of the oil droplets must be carefully controlled during the heat sterilization.

Production of large-volume parenteral products

The fluids are produced and filled into containers in a high-standard clean room environment (see Ch. 29). The high standards are required to limit the contamination of these products with organisms, pyrogens and particulate matter. Use of stringent quality assurance procedures is essential to ensure the quality of the products.

In commercial manufacturing facilities, large volumes of fluids are used in the production of a batch of product. The fluids are packaged from a bulk container into the product container in highly mechanized operations using high-speed filling machines. Just before the fluid enters the container, particulate matter is removed from the fluid by passing it through an in-line membrane filter. Immediately after filling, the neck of each glass bottle is sealed with a tight-fitting rubber closure that is kept in place with a crimped aluminium cap. The outer cap is also aluminium and an outer tamper-evident closure is used.

When using plastic bags, the preformed plastic bag is aseptically filled and immediately heat sealed. As an alternative, a blow–fill–seal system can be used. This integrated system involves melting the plastic, forming the bag, filling and sealing in a high-quality clean room environment. Blow–fill–seal production decreases the problems with product handling, cleaning and particulate contamination. Following filling of the product into containers, the fluids are examined for particulate matter and the integrity of container closures established.

Moist heat should be used to sterilize parenteral products, irrigation solutions and dialysis fluids wherever possible. This should be carried out as soon as possible after the containers have been filled. Plastic containers must be sterilized with an over-pressure during the sterilization cycle to avoid the containers bursting.

Containers and closures

Large-volume parenteral fluids are packaged into:

The containers and closures that are used for packaging parenteral products must:Glass bottles are normally made of Type II glass (Fig. 38.4), but Type I glass is used for products that have a high pH, despite the increased costs. Glass bottles have advantages for packaging these fluids as they are transparent and chemically inert. They may be used for products that are incompatible with plastic containers. Glass bottles also have some disadvantages. They are much heavier than plastic and therefore less transportable. Although they are strong, they are also brittle, and subject to damage during transport and storage. During use they require the use of an air inlet filter device for pressure equilibration within the container. Particles of glass can be released into the injection fluids. Damage to the neck of the bottles may result in contamination of the container contents from the external environment. A further problem with glass containers may occur during moist heat sterilization. This results in contamination of the fluid due to a pressure imbalance between the internal and external environment. Owing to these difficulties with glass containers, plastic containers have become widely used.

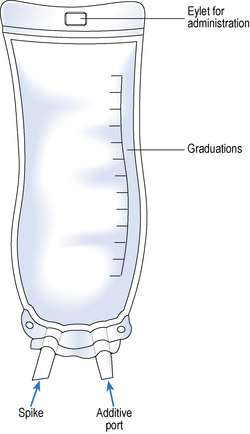

PVC collapsible bags are used to package most infusion fluids. They are designed with a port for the attachment of the administration set and an additive port for the addition of small-volume parenteral fluids.

The disadvantages of plastic bags are:Semi-rigid plastic containers are used for volumes of 100 mL for electrolyte solutions, 3 L for TPN solutions and up to 5 L for dialysis solutions.

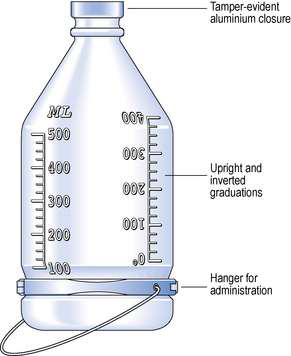

Semi-rigid bags are designed with two ports. One port allows the attachment of the administration set. The other port permits the addition of small-volume parenteral products or small-volume infusion fluids. These containers are intended for single use. They have a graduated scale that can be read either in an inverted or upright position (Fig. 38.5). To enable containers of large-volume parenterals to be suspended from a drip stand for administration, bags are made with an eyelet opening that can be pierced to suspend the bag. Glass bottles are supplied with a plastic band that fits around the container to allow the bottle to be suspended during fluid administration.

Administration of large-volume parenteral fluids

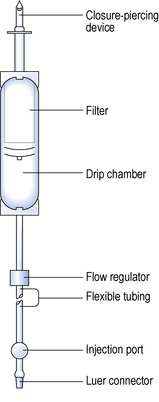

All large-volume parenterals are administered to the patient by a parenteral route using a wide variety of administration sets. Most infusion fluids are administered using the standard infusion set specified in British Standard 2463 (Part 2, 1989). These sets are packaged as sterile units intended for single use (Fig. 38.6). Fluid moves through them by gravity, at a rate that is affected by the physical characteristics of the fluid and the fluid pressure, determined by the height of the infusion above the patient. The administration set is made up of a rigid plastic spike that is inserted into the rubber septum of an infusion container. A filter that removes any particles from the fluid is positioned above a clear drip-control chamber, which aids monitoring the fluid flow rate. These components are connected by at least a 150 cm length of clear flexible tubing. The tubing has a flow regulator and a rubber injection port. The tubing is fitted with a Luer connector for attachment to a needle or catheter that is inserted into the vein of a patient.

Labelling

Batch-produced products have identical labels attached to both the product and the outer packaging carton that is used for transport. With flexible plastic containers, the labelling requirements are commonly printed directly on to the container prior to filling. With bags containing TPN fluids, a label is placed on the bag itself and an identical label is attached to the outer plastic cover on the bag. Labels are attached to infusion fluid containers. The labels on parenteral fluids should include the following details:

Containers often carry a warning label to discard the remaining product when treatment is completed.

Aseptic dispensing

Most parenteral fluids are terminally moist heat sterilized. However, some products are aseptically compounded from sterile ingredients in the hospital pharmacy. These products are prepared and dispensed for individual patients. Examples of aseptically prepared products are TPN fluids and the aseptic reconstitution of freeze-dried formulations. These freeze-dried products are often reconstituted using either water for injections or 0.9% sodium chloride injection. Aseptic dispensing is performed in a Grade A clean room environment or a Grade A isolator chamber (see Ch. 40). The dispensing of these products relies on good aseptic procedures to ensure the sterility of the product. Owing to the absence of terminal sterilization, it is important that manufacture is performed using rigorous quality assurance procedures. Aseptically dispensed products are given a very limited expiry time.

Infusion fluids used for nutrition

Nutrients can be delivered to patients by intravenous administration. This is known as total parenteral nutrition and should allow for both tissue synthesis and anabolism. Some patients require TPN for prolonged periods. Initially patients are provided with their TPN in hospital. They may then undergo training to allow self-administration at home. This is known as home parenteral nutrition. Information on total and home parenteral nutrition is given in Chapter 41.

Admixtures

These are prepared by adding at least one sterile injection to an intravenous infusion fluid for administration. The injections to be added are packed in an ampoule or vial, or may be reconstituted from a solid. These additions should be carried out using aseptic procedures in a Grade A environment within an isolator cabinet or clean room facility. This environment is required to maintain the sterility of the product and avoid contamination of the product with particulate matter, microorganisms and pyrogens. Following the additions, a sealing cap may be placed over the additive port of the infusion bag to prevent further, potentially incompatible, additions at ward level. Hospital pharmacies often have a centralized intravenous additive service (CIVAS) as detailed in Chapter 40. These facilities ensure that additions to infusion fluids are carried out in a suitable environment.

Novel delivery systems

Special delivery systems are used to facilitate self-medication by patients in a home environment. Some of these delivery systems are described below.

Infusion devices

There are situations that require strict control of the volume of fluids that are infused into a patient. Accurate flow control with infusion devices is vital for patient safety and for optimum efficacy of the infusion. A range of delivery systems are available that regulate the volume of fluid administered to the patient.

These systems are used both in the hospital and for the self-administration of fluids by patients at home. The selection of an infusion device for the self-administration of medicines by patients requires careful consideration of several factors including:

Infusion devices available include: All these devices should be:Infusion pumps

These devices use pressure as the driving force to allow administration of fluids into the patient. Infusion pumps, which can be divided into those that move fluid by a piston and valve mechanism and those that move the fluid by peristalsis, are widely used. Infusion pumps are expensive to purchase and operate but allow fluids to be accurately infused into the patient at a slow rate. These devices are becoming more sophisticated with greater electronic controls.

Infusion controller

This is a simple device that can accurately deliver the required fluid volume, although difficulties occur with the administration of viscous solutions. The device relies on gravity moving the infusion fluid down the intravenous administration set. The drop rate in the administration set drop chamber is monitored by a photoelectric mechanism. The device then applies a constriction on the tube of the administration set to give a preselected flow rate.

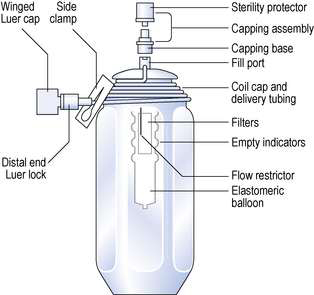

Elastomeric infusers

These devices are made of a rigid or flexible outer shell with an inner flexible reservoir (Fig. 38.7). The reservoir inside the device is aseptically filled with the fluid. The elasticity of the filled reservoir exerts a constant pressure. This forces the fluid through an integrated flow restriction device that controls the rate of fluid outflow. The tube from the infuser can be connected to an indwelling cannula in a central vein of the patient. These devices are expensive but they are simple to operate and allow easy home care use.

Syringe infusers

These devices are used for controlling the delivery of small volumes of intravenous infusions over a predetermined period of time. The syringe driver is widely used as an infusion controller for the administration of intravenous antibiotics and patient-controlled analgesia. They are often powered by mains electricity, or may be battery operated, although clockwork syringe infusers have limited low-risk applications. Syringe infusers move the syringe plunger by a motor-driven screw forcing the fluid into tubing for delivery to the patient. These small, lightweight devices allow the administration of precise volumes of fluids. Syringe devices provide good patient home care for patient-controlled analgesia where the drug is often infused over long periods. Patient-controlled analgesia is used by patients to self-regulate the intravenous administration of pain-relieving drugs at controlled intervals. Parenteral administration gives a rapid onset of drug action.

Irrigation solutions

These solutions are applied topically to bathe open wounds and body cavities. They are sterile solutions for single use only. Examples of irrigation fluids are 0.9% w/v sodium chloride solution or sterile water for irrigation. Most irrigation fluids are now available in rigid plastic bottles. Urological irrigation solutions are used for surgical procedures; they are usually sterile water or sterile glycine solutions and are used to remove blood and maintain tissue integrity during an operation.

Water for irrigation is sterilized distilled water that is free of pyrogens. The water is packed in containers and is intended for use on one occasion only. The containers are sealed and sterilized by moist heat.

Peritoneal dialysis fluids

Peritoneal dialysis involves the administration of dialysis solutions directly into the peritoneum by way of an indwelling catheter. The fluid is then drained after a ‘dwell-time’ to remove toxic waste products from the body. Peritoneal dialysis solutions are sterile solutions manufactured to the same standards as parenteral fluids. The composition of peritoneal dialysis fluid simulates potassium-free extracellular fluid. These fluids are packaged in volumes of 3–5 L in plastic containers that are similar to the bags used for TPN (see Ch. 41).

Haemodialysis

In this dialysis procedure, blood is removed and returned to the patient by way of a catheter, or a double needle arrangement, using a fistula where an artery and vein are joined together. The dialysis procedure involves the use of an artificial disposable membrane within a ‘dialyser’ machine that acts as an artificial kidney. An electrolyte fluid, simulating body fluid, bathes one side of the membrane, with blood from the patient on the other side. There is no direct contact between the blood and the dialyser fluid. Thus fluids for haemodialysis do not require to be sterile or free of pyrogens or particulate matter.

Fluid volumes of 30–50 L are used daily in haemodialysis procedures (see Ch. 41).

Blood products

These products are not usually identified as sterile products although they are commonly packaged as sterile large-volume parenteral fluids. These biological products include albumin, human plasma and blood protein fractions. All these products must be treated to inactivate virus contamination prior to packaging. This is usually achieved by specialized heat treatment or filtration. These products are unstable to heat sterilization. Therefore, they are filter sterilized and then aseptically filled into containers in large-scale production facilities. Most of these products are packed as liquids, although a few blood protein fractions such as factor VIII and factor IX are freeze dried. The collection, management and distribution of these products is carried out by the blood transfusion service.