Chapter 40 Specialized services

Introduction

This chapter describes the specialized services provided by hospital pharmacy departments in the provision of various aseptic dosage forms. These services may include some, or all, of the following elements: cytotoxic or chemotherapy reconstitution services, centralized intravenous additive services (CIVAS), radiopharmacy services, ‘high-tech’ home-care services and also the provision of aseptically prepared medicines for clinical trials. In each case, the service involves the provision of aseptically-prepared medicines which are often, but not always, tailored to the specific needs of individual patients. This chapter introduces the scope, practice and pharmaceutical challenges of aseptic compounding services. Parenteral nutrition solutions, which are also compounded aseptically, are considered separately in Chapter 41 and radiopharmaceuticals in Chapter 42.

Cancer chemotherapy

The management of malignant disease is usually based on one or more of the following treatment modes, used singly or in combination: chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery. Of these treatment modalities, only chemotherapy is a truly systemic therapy. It has the potential to destroy tumour cells in distant metastasis or in tumour tissue that has infiltrated normal physiological structures and is inaccessible to surgery or radiation therapy without significant damage of healthy tissues. Chemotherapy may be administered with curative intent, but in most adult tumours the intent is normally palliative, with the aim of reducing or controlling symptoms and of prolonging useful life of the patient.

Classification of drugs used in cancer chemotherapy

Traditionally, medicines used in the treatment of malignant disease are cytotoxic in nature, simply meaning that these agents are toxic to cells. This cytotoxic effect is not selective to abnormal cancer cells, and therefore cytotoxic drugs cause severe damage to healthy tissues. Cytotoxic medicines act by interfering with normal cell division preventing DNA and RNA replication. This is often achieved by cross-linking DNA base pairs or by inactivating key enzyme systems or cell-division structures. The mechanisms of action involved and the relative toxicities of cytotoxic medications differ from one agent to another. Most cytotoxic drugs are active only against cells in the replication stages of the cell cycle (cycle-specific) and some are active only in certain phases of the cell cycle, such as S-phase or M-phase (phase-specific). A narrow therapeutic window, severe toxicity and a range of adverse effects characterize all cytotoxic drugs. Healthcare workers involved in handling and administration of cytotoxics must have an understanding of cytotoxic agents and the rationale behind their use in the treatment of cancer.

Cytotoxic agents used routinely in the treatment of cancer can be divided into five main groups. Classification is based on mechanisms of action.

Alkylating agents

These agents form covalent bonds, usually with adjacent DNA bases, either on the same strand of DNA or on opposite strands. Alkylators can also bind to other large molecules such as proteins. Multiple mechanisms of action result from this, including damage to cell membranes, depletion of amino acids and inactivation of enzymes. DNA replication is prevented which arrests cell division. Examples of alkylating agents include: chlormethine (mustine) hydrochloride, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, melphalan, chlorambucil, thiotepa, hexamethylmelamine and busulfan.

Antimetabolites

To allow normal cell division, cells must accumulate reserves of protein and nucleic acids. This requires the presence of certain essential metabolites to form the building blocks for the production of larger molecules. The antimetabolite drugs used in chemotherapy have a similar structure to some of these essential metabolites and can take their place in the nuclear material of the cells as a ‘false substrate’ which then inhibits biological activity. This breakdown in synthesis of essential metabolites and cell components means that cell division will not take place. Also, some antimetabolites have a higher affinity for key enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of nucleic acids than the natural substrate. This ‘locks’ the key enzyme into a stable complex and effectively inactivates it. An example of this is the inhibition of thymidylate synthetase by 5-fluorouracil. Antimetabolite drugs include methotrexate, 5-fluorouracil, cytosine arabinoside, 6-mercaptopurine and 6-tioguanine.

Vinca alkaloids

These are derived from natural products and the main mode of action is to bind to an intracellular protein, tubulin, which is involved in the process of cell mitosis. This stops cell division at the second phase of mitosis (metaphase), thus preventing cell reproduction. Cytotoxic agents in this group include vincristine, vinblastine and vindesine.

Antimitotic antibiotics

This is a group of agents historically used in the treatment of infections, which were then found to have an inhibitory effect on dividing tumour cells. Examples of these agents include daunorubicin, doxorubicin and epirubicin. These drugs are associated with multiple mechanisms of action, including intercalation of DNA, enzyme inhibition and free-radical formation which results in damage to the cell nucleus.

Miscellaneous agents

Members of this group do not readily fit into the other above-mentioned categories. However, these agents invariably interfere with DNA biosynthesis and cell replication to exert a cytotoxic effect. The miscellaneous group includes procarbazine and dacarbazine, and the platinum drugs, cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin, all of which exhibit alkylating activity, and others such as irinotecan and etoposide which act on different topoisomerase enzymes which enable DNA to unwind to facilitate replication. The taxane cytotoxic drugs, which include docetaxel and paclitaxel, act by a different mechanism on the microtubular apparatus of the cell. In summary, the miscellaneous group includes agents with diverse chemical structures and mechanisms of action, some of which are derived from natural products.

Targeted therapies

The recent introduction of the targeted therapies, also known as ‘biologicals’, has dramatically improved the therapeutic outcomes for many different types of cancer. The targeted therapies are mainly monoclonal antibodies which are directed against specific receptors on the surface of cancer cells. Trastuzumab (Herceptin), for example, is directed against the epidermal growth factor receptor. By inhibiting the stimulation of this receptor, intracellular signalling cascades that promote cell proliferation are blocked. Trastuzumab has been found to significantly improve the treatment of certain types of breast cancer when combined with conventional (cytotoxic) chemotherapy. Other examples of targeted therapies include bevacizumab and rituximab which are used for the treatment of colorectal cancer and certain lymphomas, respectively.

Although the targeted therapies are more specific than conventional chemotherapy agents, toxicity is still a major issue, with the risk of side-effects from conventional agents (e.g. cardiotoxicity caused by doxorubicin) being augmented by the targeted therapy. The targeted therapies are not considered to be cytotoxic agents, although there is some evidence that these drugs can cause indirect cytotoxic effects.

Dosage forms used in chemotherapy

The majority of chemotherapy doses are administered as injections or infusions. The parenteral route offers the advantages of assured bioavailability, careful control over the rate of drug administration and the sequence of administration for regimens based on two or more drugs, and also the ability to stop drug administration immediately in the event of severe, acute adverse effects. However, the parenteral route is invasive, uncomfortable and inconvenient for the patient, and may be associated with complications such as infection, extravasation and thromboembolism. The majority of chemotherapy injections or infusions are given in the hospital setting, usually at specialized outpatient clinics, where nursing and medical support is readily available.

Parenteral cytotoxics are available as sealed vials containing freeze-dried powders or sterile, concentrated solutions. These presentations are designed to provide an adequate shelf life (usually >2 years) for the manufacturer and the user. The freeze-dried powders require reconstitution with an appropriate diluent. The reconstituted solution or the infusion concentrate may then require further dilution before being filled into syringes, infusion bags or infusion devices for administration to patients. The process of taking chemotherapy doses, as provided by the manufacturer, and preparing the required dose in a ready to use form for administration to the patient is often simply termed ‘reconstitution’, although in practice, it is much more than that.

Parenteral cytotoxics can be administered via the following routes:

Syringe drivers and ambulatory infusion devices can be filled with cytotoxic medicines for use in the community by patients receiving home chemotherapy.

Care must be taken when checking prescriptions and administering chemotherapy that the route of administration has not been transposed. The vinca alkaloids (e.g. vincristine), for example, must never be injected by the intrathecal route, and when this has occurred as a result of an error, the results have always been fatal.

The focus of this chapter is mainly on the provision of parenteral cytotoxic medication for hospital and home patients. However, it should be noted that cytotoxic medicines are available in a range of oral dosage forms including tablets, capsules and suspensions. Recent advances in drug development have overcome some of the bioavailability issues associated with oral chemotherapy and have provided very effective treatments by the oral route. Capecitabine, for example, is a pro-drug of 5-fluorouracil which is selectively activated in the liver and in tumour tissue. A discussion of oral chemotherapy is beyond the scope of this text, and the reader is referred to the British Oncology Pharmacy Association’s ‘Position statement on care of patients receiving oral anticancer drugs’ and the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia’s ‘Standards of practice for the provision of oral chemotherapy for the treatment of cancer’ for more information on this increasingly important area (see Appendix 5).

Dose and schedule of chemotherapy

An explanation is given in Chapter 26 of how to calculate doses on the basis of the patient’s body surface area (BSA). The use of BSA is designed to reduce inter-patient variability in responding to chemotherapy, although the scientific validity of this approach is now being challenged. In the case of carboplatin, the dose is calculated according to the patient’s renal function and a pre-defined pharmacokinetic parameter (area under the plasma concentration–time curve or AUC). Clinical pharmacists specialized in oncology and haematology are routinely expected to validate chemotherapy protocols and prescribing systems, as well as calculating the doses required. In some parts of the UK, appropriately qualified pharmacists prescribe chemotherapy as supplementary prescribers (see Ch. 17).

Cytotoxic agents can be used individually or in combination. Many oncology centres use a combination of medicines in nationally recognized, evidence-based protocols. These are usually denoted by the initial letters of each medicine used in the regimen, e.g. FEC which stands for 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide in combination. Combinations of cytotoxic agents can increase toxicity, but providing they have a differing spectrum of toxicity, drug combinations may enable the administration of a higher dose-intensity. The risk of emergence of resistant tumour cells is also (at least theoretically) reduced. Further information about chemotherapy regimens can be found in the malignant disorders chapter of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (Walker & Whittlesea 2007).

Occupational exposure risks

For many years there have been concerns regarding the handling of cytotoxic agents by healthcare workers who are involved in the preparation and administration of these medicines. Cytotoxic drug exposure has been associated with various acute toxicities including headache, rash, nausea and dizziness. However, the more serious risks of occupational exposure are related to the potential mutagenic, carcinogenic and teratogenic effects of cytotoxic drugs. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies 11 cytotoxic drugs and two drug combinations as known human carcinogens, 12 drugs as probable human carcinogens and a further 11 drugs as possible human carcinogens. The United States National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety (NIOSH) issued an alert in 2004 which identified 51 drugs as potential risks to human reproduction. Routes of cytotoxic exposure include ingestion, inhalation, inadvertent inoculation (needle-stick injury) and skin contact. The latter is thought to be the most significant risk for occupational exposure.

The severity of these potential health risks requires that cytotoxic drugs are handled and used in controlled, contained environments by staff provided with adequate training and personal protective equipment (e.g. gloves, gowns, eye protection). To control these risks, and also to reduce the risk of medication errors, cytotoxic agents are prepared under strict aseptic conditions in designated areas within a hospital pharmacy (centralized service) or in dedicated pharmacy aseptic units attached to chemotherapy clinics. In the UK, this requirement is set out and enforced by the Health and Safety Executive.

Pharmacy staff preparing cytotoxic agents must be fully trained in the necessary aseptic and safe handling techniques and must be fully aware of the potential health risks and the precautions that are required when handling cytotoxic drugs. Nursing staff must also be taught strict handling and administration techniques to ensure that they do not expose themselves or patients and carers to any unnecessary risks. At one time, it was thought necessary for annual health checks and full blood counts to be carried out on all staff involved in the preparation and administration of cytotoxic drugs. Current opinion suggests that such checks are of little value, and that resources should instead be invested in the development and validation of safe procedures, staff training, competency assessment, containment facilities (isolators) and protective equipment. Procedures also need to be put in place for emergency situations, such as a cytotoxic spillage.

Published guidelines include the following areas of safe practice:

Useful guidelines on cytotoxic handling include The Cytotoxics Handbook (Allwood et al 2002), The Management and Awareness of Risks of Cytotoxic Handling (MARCH) at www.marchguidelines.com and the International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners (ISOPP) guidelines on safe handling at www.isopp.org.

Provision of a pharmacy-based chemotherapy preparation service

The provision of chemotherapy preparation (reconstitution) services requires that aseptic manipulation of pharmaceuticals is combined with protection of the operator and environment from cytotoxic exposure. Simultaneous protection of both the pharmaceutical product and the staff involved in its preparation is technically demanding and requires carefully developed systems and procedures together with extensive validation. The principles of the guidelines on cytotoxic handling (above) must be integrated with the principles of good pharmaceutical manufacturing practice. The establishment of a chemotherapy preparation service is not a trivial undertaking and a detailed business case defining the scope and need for the service is fundamental to achieve the support of hospital managers. This should include costings for facilities and equipment, maintenance costs, staff, consumables and drugs costs, together with funding for training and validation of staff. An outline capacity plan should ensure that the service is capable of meeting current and future demand; for example, the service should be able to meet the rising demand for targeted therapies.

The management of chemotherapy preparation services presents numerous challenges; balancing the requirement for stringent safety and quality assurance with the need to provide a timely and responsive service. The demand for chemotherapy, and hence the workload, can fluctuate dramatically. This adds to the difficulty in providing a service that is cost-effective, although new initiatives such as dose-banding (see later in the chapter) have helped in this respect.

Despite the challenges outlined above, it is important that pharmacy staff ‘own’ chemotherapy preparation services and take a clear lead. In the UK National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) Alert 20 on injectable medicines, it is clear that application of the risk assessment guidelines places all cytotoxic drugs, and most chemotherapy drugs, in the high-risk category. It is therefore essential that these medicines are prepared by specialized hospital pharmacy aseptic units or, alternatively, by appropriate commercial compounding providers. Pharmacy staff offer a unique combination of skills and expertise, including the practice of aseptic technique, a wide clinical knowledge of cancer chemotherapy, familiarity with formulation and drug stability issues, the application of good manufacturing practice (GMP), quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC) to aseptic preparation and considerable experience in working with standard operating procedures (SOPs), batch documentation and checking procedures. These are key attributes that help to ensure the provision of safe, effective chemotherapy and contribute towards minimizing the risks of occupational exposure to drugs used in the treatment of cancer.

Training required for staff preparing cytotoxics

All personnel involved in preparing and handling of cytotoxics require training and competency assessment in the appropriate techniques. This should include training for pharmacists, pre-registration graduates and all technical staff and pharmacy assistants working in this field. On a practical level, all staff must be aware of the following over and above standard aseptic technique and the application of GMP to aseptic preparation:

Validation of operator techniques

Prior to commencing work on reconstitution of cytotoxics, an operator’s competence in this field must be assessed. This is achieved by validating operator techniques. The operator is asked to carry out broth transfer simulations where solutions of sterile broth are transferred from one vial or container to another. The aim of the simulation is to replicate the aseptic transfer techniques which would routinely be used when preparing sterile cytotoxic products. All work is carried out under strictly controlled aseptic conditions. The broth-filled vials can then be incubated for an appropriate time (7–14 days) and examined for microbiological growth. This procedure can be used in conjunction with observing the operator at work to determine operator competence in aseptic transfer techniques (see also Ch. 29).

Each operator undergoing training is required to undertake a predetermined number of broth transfer simulations. Operators must achieve negative results (no growth after incubation) on each occasion before they are deemed capable of preparing cytotoxic agents. The number of broth simulations undertaken can vary from one hospital to another but typically each operator and each process would be re-validated at least every 3 months. Training procedures should be reviewed on a regular basis and retraining and refresher courses made available to all staff. Operators routinely incorporate environmental monitoring tests such as settle plates and finger-dab plates into the production schedule as part of the QA process. A member of staff with environmental monitoring results outside of predefined action levels should be retrained and revalidated before resuming aseptic preparation work. Expert guidance on the validation and monitoring of aseptic compounding has been published in The Quality Assurance of Aseptic Services by the NHS Quality Control Committee (Beaney 2006).

Certain handling problems can be encountered when dealing with cytotoxic agents. The formation of an aerosol on removing a needle from a vial containing a cytotoxic agent can result from pressure differences between the inside of the vial and the syringe. This is known as ‘aerosolization’ and can be prevented by inserting a venting needle into the vial or using a specialized reconstitution device to allow air pressures to equilibrate during addition or withdrawal of solutions. Operator technique in the safe handling of cytotoxic drugs can be assessed by simulating aseptic transfer processes using a sterile solution containing a fluorescent dye such as quinine hydrochloride. Any splashes or spillage on the work area or equipment, indicative of poor technique, can be visualized using a portable ultraviolet (UV) lamp. Further details on this type of operator competency assessment can be found in The Cytotoxics Handbook (Allwood et al 2002). As with assessment of aseptic technique, safe handling should be evaluated using a combination of simulation and expert observation.

Documentation required for cytotoxics

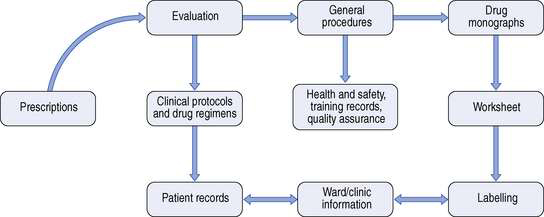

On receipt of a prescription for a cytotoxic agent a number of procedures must be undertaken. Figure 40.1 shows the areas of work in which a pharmacist may have involvement.

Fig. 40.1 Documentation required for cytotoxic services. (From Allwood et al 1997, reproduced with permission.)

When the prescription is received, it is checked by an experienced oncology pharmacist to ensure the accuracy of patient details and dosage calculations and that the presentation or dose form is suitable. The prescription must be validated against an approved chemotherapy protocol, where the drugs, doses, dose intervals and routes of administration are clearly defined. Many chemotherapy regimens are administered in ‘cycles’, with 2–3 week intervals between them. It is essential that patients receive the correct number of cycles of treatment at the correct intervals. Drug monographs and the manufacturer’s Summary of Product Characteristics can be consulted to check drug-specific details including, for example, shelf life of the reconstituted product and the recommended diluents.

Information from the prescription is transferred to a worksheet or batch document and details of medicine(s) required, diluent and volume for reconstitution are recorded together with the number of drug vials required. Details of batch numbers and expiry date for each component used, all dose and dilution calculations, preparation methods, container(s) to be used, time and date of preparation, and expiry of the final product are also required. Additionally, a sample label is attached to the worksheet. Most chemotherapy preparation units use preprinted worksheets for each chemotherapy protocol, with a pharmacist-approved master document from which copies are made. Alternatively, some units use a computer-based system which contains a database of all approved chemotherapy protocols. Examples of such systems in the UK include Oncology Patient Management Audit System (OPMAS) and Chemocare. These systems produce batch documents and labels, and although computer-generated documents are probably less prone to error, it is essential that all computer systems are fully validated before use.

Labels for cytotoxic medicines are conventionally printed on a yellow background and include the term ‘cytotoxic’, although many units prefer black print on a white background for clarity. Labels should include the following information:

When the worksheet is complete, the materials required for the reconstitution procedure are collected together in a marshalling area (adjacent to the clean room) and placed in a suitable plastic tray. The documents and components selected are then subjected to an initial check before transfer to the designated clean room. After preparation has been completed, the finished product(s) and used or part-used vials are returned in the tray, together with batch documents, for labelling, inspection and release. Some cytotoxic agents require protection from light and are sealed in opaque plastic overwraps which will also require labelling. The pharmacist responsible for the release of the prepared medicines will check all details on the worksheets and will reconcile the number of drug vials used in the preparation. If all of these details are in order, the pharmacist will sign the worksheet or batch documents to signify approval, and the medicines are delivered to the clinic, ward or patient, as appropriate. All batch documents must be retained, and many hospitals in the UK are expected to hold these for up to 13 years after the date of preparation.

Cytotoxic preparation areas

In the UK, and in many parts of Europe, pharmaceutical isolators are used for cytotoxic preparation. In addition to providing aseptic conditions for preparation of the product, isolators are designed to protect the operator and the clean room environment from cytotoxic contamination. To achieve this, many isolators operate under negative pressure with respect to the clean room, and the exhaust air is externally ducted via a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter. All isolators should be located in a classified clean room, although the grade of the clean room environment required is dependent upon the isolator transfer system.

It is generally accepted that isolators offer greater operator protection than open-fronted Class II safety cabinets, although there is little published evidence to support this view. The main disadvantages of isolators include limited access for equipment and difficulties in cleaning and removing cytotoxic residues. Gas sterilizable isolators enable sterilization of the outer surface of vials and components used in the preparation process. Gases such as vapourized hydrogen peroxide are pumped into the isolator to sterilize the inside of the isolator and the outer surface of components in situ, prior to manipulation. This increases assurance that the aseptic environment is maintained, but the validation of gas-sterilization cycles can be complex.

For a more detailed discussion of aseptic preparation facilities, the reader is referred to Chapter 29.

Techniques and precautions

When handling cytotoxics, it is vital that the appropriate protective clothing is worn. Operators using clean room facilities must wear appropriate clean room clothing, with the addition of chemotherapy gowns or armlets for extra protection. These garments are non-shedding and have an absorbent surface and impermeable backing. This design reduces the risk of splashing of solutions on contact with the gown, and also protects the operator from skin contact by cytotoxic drugs. Normally full clean room suits are worn beneath the chemotherapy gown so it is important to ensure that the clean room temperature is carefully controlled. Gloves designed specifically for cytotoxic handling are available and these are normally fabricated from a nitrile material. Gloves should also be worn for handling cytotoxic drug vials outside the clean rooms as these can be contaminated with cytotoxic residues on the outer surface. For operators working in an isolator workstation, the use of a face mask is considered optional from the operator protection viewpoint, but, in accordance with good aseptic practice, face masks should always be used to cover facial hair.

Product segregation is crucial in all aseptic work to avoid any risk of product mix up. In the case of cytotoxic chemotherapy, any such error could be lethal to the patient. For this reason, only one product, or one batch of product, is permitted within the isolator or Class II workstation at any one time.

Reconstitution procedures

When carrying out reconstitution procedures, certain precautions must be taken:

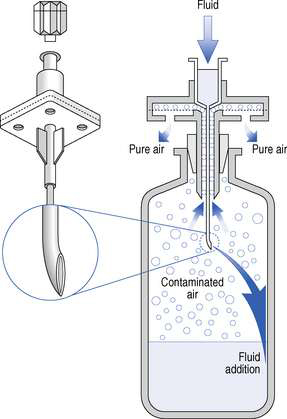

The vials that contain cytotoxic agents are effectively a closed system which contains either a powder requiring reconstitution or a drug concentrate requiring withdrawal from the vial into a syringe. In each case, equalization of pressure within the vial is required to allow withdrawal from it. This can readily be achieved by inserting a sterile 0.2 mm hydrophobic filter venting needle into the vial to facilitate liquid transfer. Ordinary needles with no hydrophobic filter must not be used for venting due to the risk of leakage of cytotoxic solution from the needle. Alternatively, reconstitution devices are available to help with the reconstitution process. Some of these devices consist of a small plastic spike with an integral hydrophobic filter. These devices are useful for rapid transfer of solutions, but the large needle bore can produce large holes in the rubber bung of cytotoxic vials, thus increasing the risk of leakage. The CytoSafe needle is a commonly used example of this type of product. This device consists of a needle which is vented to allow equilibrium of pressure between the vial and the syringe. It is useful for reconstitution of large vials or when more than one vial is required for a dose (Fig. 40.3). However, care must be taken when withdrawing or adding liquid to a vial as the filter may become blocked.

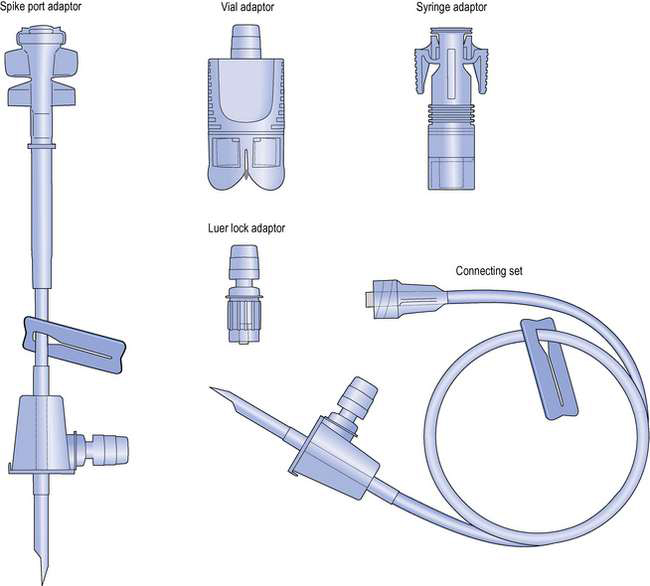

More recently, advanced ‘closed systems’ using needle-free technologies have been designed for cytotoxic handling. These devices virtually eliminate the risks of cytotoxic aerosol formation and operator needle-stick injuries. An example of this type of device is the Tevadaptor (Fig. 40.4). The Tevadaptor system comprises a vial adaptor to access the drug vial, and a syringe adaptor which fits securely onto a luer lock syringe and enables needle-free docking with the vial adaptor. These components allow the closed-system, needle-free addition of diluents to the drug vial for cytotoxic reconstitution, and also the withdrawal of liquids from drug vials into syringes. The spike port adaptor and the connecting set enable a syringe adaptor to dock with an intravenous (IV) bag for addition of additives to the infusion. The two sets provide for connection to the giving set by either a spike (spike port adaptor) or via a luer fitting (connecting set). Alternatively, the luer lock adaptor can be used to access infusion bags fitted with luer additive ports using the syringe adaptor.

Fig. 40.4 Tevadaptor closed cytotoxic reconstitution and fluid transfer system. (Courtesy of Teva Hospitals.)

The Tevadaptor and other closed reconstitution systems have been shown in studies to be effective in reducing cytotoxic contamination in the work area, and also on products leaving the isolator. The use of these devices will, inevitably, increase costs of the compounding process.

Cleaning the work area

Cytotoxic workstations, particularly isolators, can be difficult to clean. This can result in a build-up of cytotoxic contamination within the isolator with the potential to increase the risk of contamination of both the operator and the outer surfaces of preparations leaving the isolator. The amount of contamination in isolators can be reduced by good technique and by conducting the aseptic manipulation work on a chemotherapy preparation mat. These are sterile mats with an absorbent surface and an impermeable backing which will cover a large proportion of the isolator or Class II cabinet work surface. Any minor spillage is contained on the mat, which is disposable and normally replaced after each day or each work session.

When cleaning isolators or Class II workstations, it is important to recognize that most cytotoxic drugs are water soluble. For this reason, either sterile water or a sterile aqueous-based detergent solution should be used as the first cleaning agent, together with sterile absorbent wipes. This clean should then be followed with a spray and wipe of 70% alcohol to sanitize the surfaces and maintain the aseptic environment.

Effective cleaning is also essential to reduce the risk of cross-contamination of drugs being prepared in the isolator. There is documented evidence of product contamination by the previous infusion prepared in the isolator, and for this reason, the effectiveness of cleaning procedures should be validated. This can be done using simulations with fluorescent dyes replacing the cytotoxic drug, and using a UV lamp after the cleaning process to visualize any remaining fluorescent residues. However, a more robust validation would include deliberate contamination by three or four ‘marker drugs’ from different chemical classes, where wipe samples are analysed after cleaning to detect any low levels of drug residues that persist.

Dealing with cytotoxic spillage

During reconstitution or manipulation, operators must be aware of the procedures required for dealing with a cytotoxic spillage. In the event of a spillage, the problem should be dealt with immediately to prevent the spread of contamination. A written policy on dealing with spillages should be prepared and the operator should be fully competent in the implementation of this. Most policies are based on a spillage kit which contains all the required materials to deal with a spill. These include an absorbent cloth to wipe up liquid spillage and booms to contain a large volume spillage. Spillage involving a powder should be wiped up using a damp cloth to ensure that inhalation of powder particulates does not occur. Contaminated cloths should be disposed of in a cytotoxic hazardous waste bag or cytotoxics sharps bin. All surface areas contaminated by the spillage should be washed with copious amounts of water (sterile water is available in the spillage kit). Cytotoxic spillage kits should be available in pharmacy preparation units, on chemotherapy wards and clinics and in vehicles used to transport cytotoxic medicines.

If the spillage has come in contact with the skin, the contaminated area should be washed thoroughly with soap and water. Contact with eyes should be dealt with by irrigation with a sodium chloride eyewash, the incident reported and medical help sought. In the event of a needle-stick injury involving direct contact with a cytotoxic agent, the puncture wound should be encouraged to bleed and the area should again be thoroughly washed. All accidents involving spillage or needle-stick injury should be reported.

Disposal of cytotoxic waste

Cytotoxic waste materials are regarded as ‘hazardous waste’ and should be placed in a purple coloured plastic bag, sealed and labelled with a cytotoxic warning label ready for disposal by incineration. Sharp objects including needles, syringes, ampoules and vials should be placed in a sharps bin which is made of rigid plastic and does not allow leakage of cytotoxic waste. When the sharps bin is full, it should be sealed with ‘cytotoxic’ warning tape and disposed of by incineration. Operators should never put their hands or fingers into a sharps bin, and sharps bins should not be over-filled.

Nursing staff have the task of handling excreta of patients who have received cytotoxic medicines. The potential risks involved will vary depending on the cytotoxic medicine used, dosage given, route of administration and the type of elimination profile. Reports suggest that excreta should be assumed to be potentially hazardous for at least 48 hours after cytotoxic administration is complete. Ward staff should be made fully aware of the patients who pose this risk and should always take the necessary handling precautions, for example wearing chemotherapy gowns and gloves. Patients receiving chemotherapy in the outpatient clinic should have the use of a designated toilet to minimize the spread of contamination. For patients receiving home chemotherapy, family members should be warned about the potential hazards and advised to exercise extreme caution when handling excreta from the patient. The Cytotoxics Handbook (Allwood et al 2002) contains useful information on the persistence of cytotoxic drugs in patient excreta.

Packaging of cytotoxic infusions

As a minimum, cytotoxic infusions in syringes or infusion bags should be packaged in a labelled, hermetically sealed overwrap. This has two functions: containment of any leak from the infusion and protection of portering and nursing staff from any cytotoxic residues on the surface of infusion bags and syringes. Ideally (and essentially for transport over long distances), the infusions, in sealed overwraps, should be transported to wards and clinics in a rigid, closed plastic box to provide further protection from any mechanical trauma.

Management of the chemotherapy workload

It is evident from the above text that chemotherapy preparation is very labour-intensive. In recent years, there has been a clear tendency to move from in-patient treatment of cancer patients on hospital wards to chemotherapy outpatient clinics. The operation of outpatient clinics can place significant workload pressures on pharmacy chemotherapy units, partly because several patients often arrive for treatment at the same time, and also because blood test results and other patient-specific data are required before the oncologist is able to confirm the chemotherapy dose and allow treatment to proceed. This often results in several prescriptions arriving in pharmacy at the same time and, consequently, severe delays before some patients receive their chemotherapy on the outpatient clinic. Such delays are not only distressing for patients and chemotherapy nurses waiting to administer treatments, but can also result in treatments over-running normal working hours which can limit the availability of specialist oncology staff to deal with any treatment complications that patients may experience.

Various strategies have been employed to manage these problems. In many centres, it is possible to organize patients’ GPs to take blood samples 2 days before the patient is due to visit the outpatient clinic for treatment. Blood counts are then available to the oncologist before the patient arrives at the clinic for treatment. This enables prescriptions to be ‘pre-written’ so that pharmacy can prepare batch documents and tray-up consumables on the day before treatment, and the go-ahead for preparation can be authorized very early on the day of treatment. Pre-preparing treatments in anticipation of blood results is not recommended, because if treatment does not proceed, or if a dose reduction is required, significant costs are incurred from drug wastage.

More recently, many oncology centres have adopted the approach of ‘dose-banding’. Individual patient doses are calculated in the normal way, but the dose is then fitted to predefined dose ranges or ‘bands’. If for a given drug the predefined bands were 100–110 mg, 110–120 mg, 120–130 mg, etc. then, for example, a calculated dose of 113 mg would be fitted to the middle band of 110–120 mg. The dose provided to the patient is standardized for each band, normally at the mid-point of the band. So in this example, the standard dose provided would be 115 mg. The key point about dose-banding is that these standard doses are provided with a limited range of standard pre-filled syringes or infusion bags, either singly or in combination. In practice, five or six standard pre-fills are needed to provide the required range of standard doses. Depending on the validated shelf life, these standard pre-fills can be batch prepared, and a stock of them can be stored on the outpatient clinic for immediate dispensing when required. In many centres, this approach has reduced both patient waiting times and drug wastage to almost zero. Further advantages of this approach are that the batches of standard pre-filled syringes or bags can be prepared according to planned work schedules and may also be subjected to prospective QC testing prior to release. Not only is the workload planned and controlled, but quality and patient safety can be improved also. Dose-banding has been widely accepted by oncologists in the UK, largely because the maximum variation of the administered dose from the prescribed dose is limited to <5%.

There is no doubt that managing chemotherapy services is a very challenging task. Operating a patient-focused service which meets clinical needs within the confines of limited resources requires innovation, organization and regular communication with medical and nursing colleagues. The service should be carefully monitored and key outcomes such as errors and patient waiting times should be audited on a regular basis. Requests for new work should be handled efficiently, but a capacity plan to define safe workload limits must be in place to ensure that the service does not become overstretched and compromise patient safety.

Administration of cytotoxic medicines

Specialist chemotherapy nurses are usually responsible for administration of chemotherapy on the oncology or haematology ward and in the outpatient clinic. Some highly specialized, high-risk infusions (e.g. intrathecal and intra-arterial) are still administered by medical staff. Cytotoxic infusions are normally infused using electronic pumps, some of which provide a full audit trail of the infusion time, rate and volume delivered. For many drugs, the chemotherapy infusions are vesicant and can severely damage the lining of blood vessels and blood cells. To reduce such damage, these drugs are infused into a central vein (e.g. cephalic and vena cava) where there is a high blood flow to ensure rapid dilution of the drug infusion. Placing a central venous catheter into a patient is not a trivial procedure and is usually carried out in an operating theatre by an experienced anaesthetist. An alternative is the placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), which is tunnelled to a central vein via peripheral veins and can be inserted by a trained nurse in the clinic.

A potential complication of chemotherapy administration occurs when the tip of the catheter used for drug administration locates in the tissues instead of the lumen of the vein. This is known as ‘extravasation’ or ‘tissuing’ and can cause extremely serious tissue damage which, in extreme cases, can require the amputation of the limb. In the event of extravasation occurring, administration is halted immediately for staff to aspirate infusion from the tissues and carry out locally agreed policies and procedures which involve, for example, the administration of steroids to reduce tissue inflammation. Extravasation kits should be available on hand in the ward or clinic in anticipation of this problem.

Administration of chemotherapy is clearly a complex and potentially dangerous procedure. National Cancer Standards define the qualification and experience of staff engaged in all aspects of cancer treatment, including drug administration. The NPSA 20 Alert on injectable medicines will place the administration of chemotherapy under particular scrutiny, and will further ensure that only experienced and competent staff are permitted to administer these infusions. Specialized and very high-risk administration routes, such as intrathecal chemotherapy, are the subject of specific and detailed guidelines. For example, in the UK, the NHS Executive published National Guidance on the Safe Administration of Intrathecal Chemotherapy (HSC 2003/010) in 2003. Pharmacy has a major role in assuring error-free drug administration. Infusions must be presented in the appropriate form and container, and must be clearly labelled so that nursing staff are provided with unambiguous information about the route, method and rate of administration. The involvement of the oncology clinical pharmacist in the development of drug administration procedures is crucial.

Provision of chemotherapy at home

The introduction of effective oral chemotherapy for cancer, such as capecitabine, has enabled increasing numbers of patients to receive treatment at home. It is also possible to provide parenteral chemotherapy in the domiciliary setting, with home chemotherapy programmes. Patients have more involvement in the administration of their medicines, are able to spend more time with their families and avoid the inconvenience of regular hospital treatment. This, in turn, liberates hospital beds to treat other patients.

Chemotherapy infusions can be administered to patients at home or at work using small, portable ambulatory pumps. These range from sophisticated, programmable electronic devices and battery operated syringe drivers to simple, disposable elastomeric pumps which have a fixed rate of infusion. For a more detailed review of ambulatory infusion devices, the reader is referred to Chapter 38 of this publication and to The Cytotoxics Handbook (Allwood et al 2002).

The pharmacist responsible for the centralized cytotoxics service must have a good working knowledge of chemotherapy regimens and the appropriate infusion devices available for home chemotherapy. In certain oncology centres, the pharmacist may also become involved in training patients to manage their infusion devices, and in the safe handling and disposal of cytotoxic drugs. This is necessary to ensure the health and safety of patients and their carers in the home-care environment.

The implications for a pharmacy department setting up a home chemotherapy service are wide ranging. Many home chemotherapy doses are supplied for 1 or 2 weeks at a time. Staff will need to be trained and validated in the techniques used for filling the ambulatory infusion devices required for home chemotherapy. Early home chemotherapy regimens were relatively simple, for example 5-fluorouracil continuous infusion for colorectal cancer. However, more complex, multiple agent regimens are now used. In cases where either the therapeutic response or drug clearance is influenced by a circadian rhythm, it is possible to exploit chronotherapy to optimize treatment using electronic infusion pumps programmed to administer different amounts of chemotherapy over a 24-hour period.

The stability of drug infusions in ambulatory devices is a key element in the provision of home chemotherapy services. In addition to prolonged storage under refrigerated conditions, ambulatory infusion devices are worn under the patient’s clothing, exposing drug infusions to elevated temperatures (37°C) for extended periods of time. Stability data on cytotoxic infusions are documented in The Cytotoxics Handbook (Allwood et al 2002) and Handbook on Injectable Drugs (Trissel 2006). In many cases, stability data appropriate to specific combinations of drug infusions and devices can only be found in the scientific literature, or may need to be determined de novo. In this context, the continuation of research on drug stability under clinical conditions is a crucial role for the few hospital pharmacy departments with a research laboratory.

Centralized intravenous additive service (CIVAS)

The Breckenridge Report produced in the UK in 1976 made recommendations that IV infusions should be prepared, where possible, by hospital pharmacies. Although the preparation of IV cytotoxic medicines was taken up soon after this report, the wider provision of an IV additive service did not commence until the 1980s and then only in a limited number of hospitals.

The establishment of the UK national CIVAS group in 1991 gave more hospital pharmacists the initiative and support for the provision of a CIVAS. By 1998 the CIVAS Handbook was produced to provide guidelines for hospital pharmacists setting up a CIVAS. Currently a large proportion of hospital pharmacists in the UK and many European countries provide a CIVAS, and this is augmented by a growing number of commercial compounding units. Despite these developments, it is estimated that of all infusions prepared in UK hospitals, less than 40% are prepared in pharmacy CIVAS units.

Scope of a CIVAS

A CIVAS is set up to provide a range of parenteral dosage forms suitable for administration to patients. Medical, nursing and pharmacy staff involved in patient care in this field will decide the range of dosage forms supplied. A CIVA service can provide the following:

Often a CIVAS is operated in conjunction with other aseptic compounding services in the pharmacy (e.g. cytotoxic reconstitution and compounding of parenteral nutrition solutions). Given that CIVAS are resourced to provide only a proportion of the IV additive/compounding needs of a hospital, they normally prioritize the services offered according to clinical risk. Accordingly, CIVAS-produced infusions often include antibiotics for neonates and paediatric patients which require extensive dilution to the required doses. Other high-risk infusions such as complex electrolyte mixtures and ambulatory infusions for home use are often prepared by hospital CIVAS units or are sourced from commercial suppliers. Economic factors can also influence which infusions are prepared in CIVAS units. Many IV medicines contain no preservative and are designed for single use only. Preparation of infusions from these medicines on the hospital ward can often result in significant wastage because only the dose required for immediate use can be taken. However, subject to validated infusion stability, it is possible for a CIVAS unit to prepare a batch of infusions for several days’ use, or even longer, so reducing or eliminating drug wastage. In the UK, aseptically prepared medicines may only be assigned a shelf-life of >7 days if supported by validated stability data and providing the unit in which the infusions are prepared holds a ‘Specials Manufacturing License’ issued by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

It is likely that the recent NPSA Alert 20 on injectable medicines will provide the stimulus for more ward or clinic-prepared infusions to be transferred to pharmacy CIVAS units to reduce the risk of medication errors.

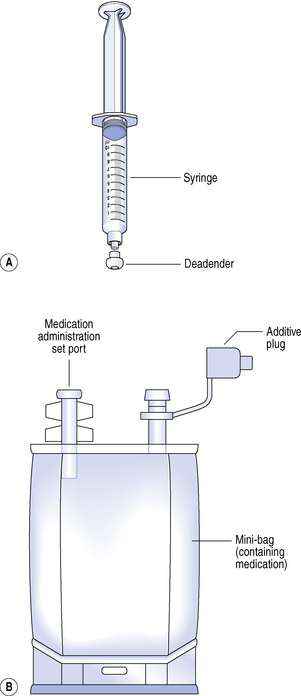

CIVAS dosage forms

Most hospital pharmacies supply IV additives in the form of a pre-filled syringe or a minibag. Minibags are small volume infusion bags containing volumes of 50–250 mL of common infusion diluents such as 0.9% sodium chloride infusion, 5% glucose infusion or water for injection. Nursing staff often prefer CIVAS doses supplied in minibags as they are easier to administer than syringes, although local preference can vary. Reconstitution procedures are usually required as IV doses are normally received from the manufacturer as sterile freeze-dried powders in sealed vials. The freeze-dried presentation enables the manufacturer to assign a realistic shelf life to these medicines, which are often relatively unstable in aqueous solution. These vials are then reconstituted with the appropriate diluent and drawn up into a syringe. The syringe is then sealed with a blind hub, or if a minibag presentation is required, the dose is transferred to an appropriate minibag ready for administration to the patient. In some cases it will be necessary to withdraw a predetermined volume from the minibag to allow the additive volume to be accommodated. In addition to pre-filled syringes and minibags, CIVAS also provide pre-filled ambulatory infusion devices for domiciliary treatments.

Provision of a CIVAS

Traditionally, IV doses were prepared on the ward or clinic by nursing staff or junior doctors who have limited training in aseptic technique and little experience of calculating appropriate doses and the complex manipulations required for preparing IV medicines. Ward facilities for preparing IV medicines are not ideal and increase the risk of the product being contaminated as it is not prepared under aseptic conditions. A CIVAS operated by trained, competency-assessed pharmacy staff using purpose-built aseptic dispensing facilities ensures that IV products are prepared to the highest possible standards. Clear, comprehensive labelling, full documentation and improved control of ward stocks of IV medicines are also possible with a pharmacy CIVAS. These attributes can significantly improve the risk management of infusions used in a wide variety of therapeutic areas.

The issues to be considered when setting up a CIVAS are essentially the same as those discussed previously for establishing centralized cytotoxic reconstitution services, although the health and safety and occupational exposure aspects are less important with CIVAS. A dialogue should be established between representatives from pharmacy, medical staff, nursing staff and hospital administrators. Information should be gathered on the number of IV doses being used, who prepares them and the conditions under which they are prepared. The proportion of this workload that should be transferred to the proposed pharmacy CIVAS unit can be identified through a risk assessment, and the resources necessary to provide this capacity can be determined. It may be helpful to clearly define the service that wards and clinics can expect through the development of service level agreements.

Any consideration of the resources required to set up a CIVAS must consider the capital costs for the aseptic unit and associated equipment (laminar flow hoods, labelling systems), maintenance costs for facilities and equipment, staff costs for both the CIVAS and the associated QA systems, staff training costs and consumable costs. It should also be possible to estimate the proportion of these costs that can be offset by savings from reduced drug wastage. There may also be the possibility of generating income by providing CIVAS to neighbouring hospitals and private clinics, providing there is adequate capacity.

The main goals of providing a CIVAS should include:

Although there are compelling reasons for the provision of pharmacy CIVAS in all major hospitals, it is important in presenting a balanced argument to be aware of potential disadvantages to the hospital and healthcare system:Many of these problems can be overcome through good communication, both within the pharmacy department and with medical and nursing staff. A service level agreement (SLA) is a useful device for ensuring that all stakeholders know their responsibilities and that the service operates within the confines of the available resources.

Techniques used in CIVAS

The techniques, procedures, documentation systems and validation requirements of CIVAS are essentially the same as those described previously for chemotherapy services. The main difference is that CIVAS medicines tend to be less hazardous so there is a much lower emphasis on occupational exposure control. This means that instead of isolators and Class II cabinets, CIVAS units tend to use conventional horizontal and vertical laminar flow cabinets. However, it should be recognized that some antibiotics (e.g. penicillins) are sensitizing agents, and some hospitals prefer to use isolator technology for both their cytotoxic and CIVA services.

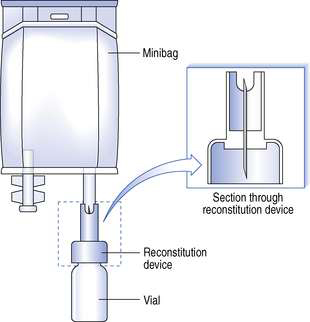

The reduced hazards associated with CIVAS medicines enable the use of pressurized systems in the reconstitution of freeze-dried drugs and in fluid transfer systems. For example, if minibags are used, a reconstitution device can be used to transfer the diluent into the vial, then, after vigorous shaking, back into the bag again. Throughout this procedure the vial and minibag remain attached via the reconstitution device which has a double-ended needle. One end of the needle is placed through the rubber bung of the vial and the other end is connected into the rubber septum of the minibag (Fig. 40.5).

Prior to removal from the laminar airflow cabinet or the isolator cabinet, all prepared syringes are sealed with a blind hub and minibags are sealed with an additive plug or tamper-evident closure. This ensures that no further additions are made to the syringe or minibag outside the pharmacy. All products are labelled and sealed into an outer bag before being transported to the ward.

Quality assurance

All procedures used during preparation of CIVAS doses must be fully validated and documented. Procedures must also be audited and be subject to in-process monitoring. Staff preparing IV products should complete appropriate batch documents and adhere to authorized SOPs and published guidelines. As with the chemotherapy preparation service described previously, batch documents, finished product, used components and records for environmental monitoring and operator validation are all considered as part of the decision-making process for the release of CIVAS medicines for administration to patients. As with any procedure carried out under aseptic conditions, routine environmental monitoring must be undertaken. This will include the use of settle plates (normally at every work session), finger-dab plates by each operator at the end of each session, and active microbial sampling, air particulate sampling and measurement of air flows from filters at least monthly. Clean room over-pressures should be recorded at least daily, and HEPA filter integrity checks should be carried out at least on an annual basis or in the event of any deviation from defined operating conditions.

Records will be kept for all IV medicines prepared and will include the batch numbers of products used during reconstitution procedures. This ensures that in the event of a product recall or any problems with an IV medicine, a full audit trail documenting all aspects of the process can be reviewed. Records of any errors or complaints should also be maintained, together with the action taken. This information should also be used to inform staff training.

Validation of procedures

Validation of aseptic processes and operator technique will include the use of broth transfer simulations and observation by experienced practitioners. The level of activity and number of staff working in the unit should be taken into account as staff movements are a potential cause of microbiological contamination (see Ch. 29). Validation of processes and operator technique for CIVAS is almost identical to the validations necessary for chemotherapy preparation (see above), with the exception that fluorescent dye simulations are arguably less critical. However, the use of fluorescent dye simulations can still play a valuable role in the validation of cleaning procedures.

Infusion stability and shelf life assignment

The assignment of a shelf life or expiry date to any aseptically prepared medicine is a rigorous, evidence-based process which requires expert interpretation of physical and chemical stability data and a clear understanding of the level of protection afforded to prevent microbiological contamination during the aseptic preparation process.

In the UK, aseptic medicines prepared under Section 10 of the 1968 Medicines Act, which requires pharmacist supervision of the process, are restricted to a maximum shelf life of 7 days, and then only if there is evidence to support this. Even if there is evidence to support a longer shelf life, an expiration of >7 days cannot be assigned to any CIVAS medicines prepared under this system. On the other hand, aseptic medicines made under a manufacturer’s ‘specials’ license issued by the MHRA can be assigned any reasonable shelf life providing this is supported by rigorous evidence on the physical and chemical stability of the infusion, and evidence that the microbiological quality of the product is maintained during both preparation and subsequent storage.

Stability data for CIVAS infusions, including cytotoxic drugs, can be sourced from a number of textbooks including Handbook on Injectable Drugs (Trissel 2006), The Cytotoxics Handbook (Allwood et al 2002) and the CIVAS Handbook (Needle 2007). In many cases, it will be necessary to search the scientific and professional literature for original stability study reports and, on some occasions, the drug manufacturer may be willing to share extended stability data. Whatever the source of information, stability data should always be subjected to critical appraisal before they are used in the assignment of infusion shelf lives.

It is critical that stability studies are carried out under pharmaceutically and clinically relevant conditions. The drug concentration, choice of diluent, container and storage conditions must reflect those used in clinical practice. The method used to assay the drug must be stability indicating, meaning that it will be responsive to any drug degradation and that drug degradation products will not interfere with the accurate determination of the drug itself. This cannot be assumed even for sophisticated and selective analytical methods such as high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). It is vital that validation data support the stability-indicating ability of the assay. In addition to the drug assay, physical stability is assessed by determination of sub-visual particulate matter, visual appearance, pH and the absence of any material or chemicals leaching from the container into the infusion. For more complex biological molecules such as monoclonal antibodies, assessment of stability using simple chemical and physical testing is not adequate. These large molecules are held in secondary and tertiary structures by weak intramolecular hydrogen bonds, and these complex conformations are essential to maintain biological activity. It is important, therefore, to assess the stability of such molecules on the basis of biological activity. In all cases, realistic acceptance limits must be defined for drug degradation. Typically either 5% or 10% degradation is permitted, depending on the clinical use of the product and the expected toxicity of the degradation product(s).

Normally, aseptically prepared medicines are stored under refrigerated conditions (2–8°C) to inhibit the proliferation of any microbial contaminants. However, the limited physical stability of some infusions under refrigerated conditions requires that room temperature storage is used instead. In some cases, freezing the infusion at −20°C can extend the shelf life of CIVAS prepared infusions. Infusions of the cephalosporin antibiotic ceftazidime are an example in which infusion stability can be increased from 8 days at 2–8°C to 84 days at −20°C. Such infusions must be fully thawed and equilibrated to room temperature before issue to the clinical area.

Assessment of infusion stability is a key responsibility of any pharmacist managing a CIVAS. In the case of infusions which are outsourced from commercial compounding units, it is essential that clear and robust evidence is available to support the assigned shelf life. Care must be exercised when attempting to extrapolate published stability data to infusions with variations in the concentration, diluents or container used. Expert review and a written justification are required to validate a shelf life where there is any variation to the conditions under which the stability data were obtained.

Consideration must also be given to the transportation and storage of aseptically prepared medicines, particularly where infusions are transported over long distances to other hospitals or to patients receiving home infusion treatments. Cold chain transport systems or refrigerated vans must be fully validated to ensure that the stability of infusions is not compromised, and the temperature of refrigerators used for storage of infusions should be monitored at least daily, but preferably by continuous monitoring and data logging (see Ch. 43).

Provision of IV doses for home patients

The potential benefits described previously for home chemotherapy are also applicable to the treatment of other, non-malignant diseases. The range of clinical applications for home infusion therapy is continually expanding; for example pain control (postoperative and terminal care), thalassaemia, infections of the bone, joints and skin, cystic fibrosis (prophylaxis and acute infection flare-up), Parkinson’s disease, and non-malignant conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis are treated with cytotoxic drugs. The ambulatory infusion devices used for non-malignant diseases are similar to those described for cancer chemotherapy, with the exception that larger infusion volumes tend to be used and with some drugs, for example antibiotics, the accuracy of the infusion rate is less critical. A number of different options are available for patients receiving home IV therapy (see Ch. 38).

Single-dose bolus injections

These are provided as a pre-filled syringe for bolus administration by either the patient or an outreach nurse. Pre-filled syringes of ceftriaxone, administered once daily for the home treatment of cellulitis, are an example of this type of presentation.

Single-dose infusions

Medicines that need to be given as an infusion at a frequency of one to four times daily are often administered using single-use, disposable elastomeric devices, such as the Baxter Intermate. The drug infusion is filled via a luer lock valve into an elastomeric reservoir which, when expanded, drives the infusion through a flow-restrictor device which may also incorporate a hydrophobic filter to eliminate any air bubbles. These devices require no battery and are available with a wide range of flow rates and infusion volumes. Elastomeric infusors can be used for self-administration by patients who can connect the device to a peripheral or central venous catheter. Examples of home infusions using elastomeric devices include ceftazidime and tobramycin infusions for cystic fibrosis, and desferrioxamine infusion for the treatment of thalassaemia.

Continuous infusions

Prolonged, continuous infusions are required for control of severe pain, where powerful opioid analgesics are infused, often by the subcutaneous route. Continuous infusions, running for 12 hours or more, are also used for other drugs such as the dopamine agonist apomorphine, which is used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. This type of infusion can be administered with small, portable syringe drivers. These battery-operated infusion devices use a syringe as the infusion reservoir and are ideal for the administration of small infusion volumes (<20 mL over 24 hours). More sophisticated electronic infusers work by a peristaltic mechanism and use polyvinyl chloride infusion reservoirs of 50–500 mL volume. These devices are often programmable and are designed to prevent alteration of settings by the patient. However, they are expensive and tend to suffer from a relatively short battery life.

The hospital pharmacy CIVAS has a clear role in providing pre-filled syringes and reservoirs for home infusion patients. Some centres also provide the actual infusion devices and other consumables required by home infusion patients (e.g. sharps bins for disposal of waste, alcohol wipes and sterile gloves). Close liaison between pharmacy, nursing and medical staff is required to ensure home infusions are prescribed and prepared when needed, that the infusion device selected is appropriate to the patient’s needs, and that the CIVAS unit can respond to any changes of dose or therapy.