36 Urinary tract emergencies

Urethral Obstruction

Feline

Theory refresher

Clinical signs associated with the lower urinary tract – in particular dysuria, stranguria, pollakiuria and haematuria – are a common reason for cats to be presented both as routine and emergency patients. Lower urinary tract disorders include urolithiasis, feline idiopathic cystitis, urinary tract infection, anatomical defects, behavioural disorders and neoplasia. An increased risk of lower urinary tract disease has been reported for example in cats confined indoors and those restricted to dry food diets with inadequate fluid intake, and signs are most commonly seen in 2- to 6-year-old cats.

Depending on the underlying disorder, complete urethral obstruction may or may not occur and this clearly has significant implications from an emergency perspective. Complete urethral obstruction almost exclusively occurs in male cats and is a potentially fatal condition (see below). Cats presenting with lower urinary tract signs but without obstruction usually have a small or empty bladder and require symptomatic medical therapy, analgesia in particular. Many of these cats will have idiopathic cystitis and will improve within 3–5 days. All these cats require appropriate analgesia but antibiosis should only be used in cases in which bacterial infection is documented by microbiology.

Clinical Tip

Nursing Aspect

On an emergency basis, nurses are often the first members of staff to speak to owners ringing about cats with lower urinary tract signs. In the author’s opinion, emergency consultation should be recommended for all cats showing dysuria, stranguria, pollakiuria or haematuria. Male cats in particular may have urethral obstruction which can be rapidly fatal. Both unobstructed male and female cats require analgesia as a minimum as these clinical signs are typically associated with varying degrees of pain.

In some cases of urethral obstruction owners report that their cat is straining nonproductively but are unable to distinguish stranguria from constipation. It is also noteworthy that not all cats with urethral obstruction show consistent urinary signs, at least earlier on. In some cases, owners ring to report an abnormal pelvic limb gait that is often presumed to be the result of trauma; alternatively, the cat may be showing nonspecific vocalization or apparent discomfort, especially when picked up. There is therefore perhaps an argument to examine all male cats with potentially compatible signs of obstruction. As a minimum, the author would strongly recommend examining all male cats with potential signs of obstruction that either have a history of lower urinary tract disease or that are confined indoors (at increased risk of urethral obstruction).

Mechanical urethral obstruction is much more common in male cats due to the narrow diameter of the penile urethra; it occurs very infrequently in females. Urethral plugs are the most common cause in male cats but uroliths may also cause obstruction, potentially in combination with a plug. Urethral strictures and rarely tumours are other possible causes. Urethral plugs are often made up of struvite material in a proteinaceous matrix. The most common uroliths in cats are made of struvite or calcium oxalate. Unlike in dogs, struvite urolithiasis in cats is not typically associated with urease-producing bacterial infection.

Prolonged urethral obstruction results in hypovolaemia and systemic hypoperfusion that may occur for a number of reasons, including the effect of hyperkalaenia and acidaemia on the cardiovascular system, and dehydration where this is a factor. In addition to azotaemia, urethral obstruction can result in profound electrolyte and acid–base disturbances including metabolic acidosis, hyperphosphataemia and hypocalcaemia. Hyperkalaemia occurs mainly due to impaired urinary excretion of potassium. The clinical manifestations of hyperkalaemia reflect alterations in cell membrane excitability and of greatest concern are the potentially life-threatening effects on cardiac conduction (Box 36.1).

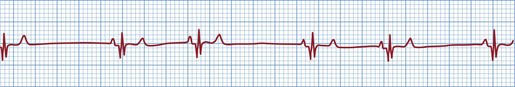

BOX 36.1 Electrocardiographic findings associated with hyperkalaemia

Figure 36.2 Atrial standstill in a cat with hyperkalaemia showing absence of P waves; peaked T waves are also present.

(From Darke PGG, Bonagura JD, Kelly DK 1996 Color atlas of veterinary cardiology. Mosby-Wolfe, London, with permission.)

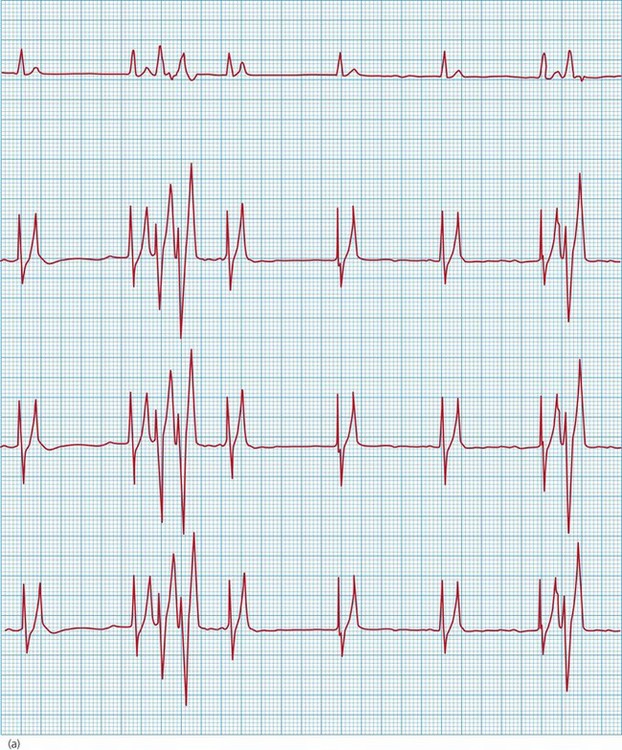

Figure 36.3 Electrocardiogram from a cat with severe hyperkalaemia (a) before and (b) shortly after administration of calcium gluconate. The pre-treatment strip shows atrial standstill with absence of P waves, as well as peaked T waves and ventricular premature complexes (VPCs). P waves are visible and there are no VPCs in the post-treatment strip.

Clinical Tip

Table 36.1 Treatment of clinically significant hyperkalaemia

| Agent | Dose/route | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 10% calcium gluconate | 0.5–1.0 ml/kg i.v. bolus over 30–60 s | |

| Neutral (regular, soluble) insulin | 0.1–0.5 IU/kg i.v. | Slower onset of action (can be more than 15 minutes) |

| Glucose solution | 0.25–0.5 g/kg i.v. | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 1–2 mmol/kg slow i.v. (repeat if necessary) |

ECG, electrocardiogram; IU, international units; i.v., intravenous.

Cats with urethral obstruction present with a spectrum of clinical compromise and, as always, the management provided should be appropriate to the individual case. With rational intensive management, even the most moribund of patients has an excellent prognosis for full short-term recovery. Long-term prognosis clearly depends on the underlying urinary tract disorder.

Case example 1

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 4-year-old male neutered domestic short hair cat presented collapsed. The owner reported that the cat may have been lethargic 24 hours prior to presentation and was inappetent on the morning of presentation. The owner was at work during the day and had returned to find the cat collapsed, at which point she contacted the practice for an emergency consultation. The cat had outdoor access and the owner had not noticed any clinical signs of lower urinary tract disease. No other significant preceding history was reported.

Major body system examination

On presentation the cat was obtunded. Cardiovascular examination revealed a heart rate of 60 beats per minute with no obvious murmur. Femoral pulses could not be palpated and mucous membranes were very pale without a discernible capillary refill. Respiratory rate was 36 breaths per minute and lung auscultation was unremarkable. Abdominal palpation revealed a moderate to large rigid bladder, and rectal temperature was markedly lowered (33.0°C).

Assessment

The cat was assessed as being severely hypovolaemic. While severely hypovolaemic cats are very often bradycardic and hypothermic, the degree of bradycardia in this case was inappropriately severe. Bladder palpation was suggestive of urethral obstruction and the severity of bradycardia was therefore suspected to be partly due to hyperkalaemia.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database. The most significant findings of this were severe hyperkalaemia (10.1 mmol/l, reference range 3.6–4.6 mmol/l) and severe azotaemia (blood urea nitrogen 80.0 mmol/l, reference range 3.0–10.0 mmol/l; creatinine 1950 µmol/l, reference range 50–140 µmol/l). Facilities were not available to measure blood pH or ionized calcium.

Continuous electrocardiography was commenced that demonstrated atrial standstill with a wide-complex sinoventricular rhythm.

Clinical Tip

Case management

The cat was started on a 20 ml/kg bolus of 0.9% sodium chloride (normal, physiological saline) and treated immediately thereafter with 10% calcium gluconate (see Table 36.1) to which there was a rapid response with respect to heart rate and rhythm (see Figure 36.3). Neutral (regular, soluble) insulin and glucose were administered intravenously at this time. No warming measures were performed initially in order not to worsen hypoperfusion (see Ch. 17) but the cat was given a low dose of methadone (0.1 mg/kg i.v.). Another dose of calcium gluconate was also given, prompted by deterioration of the heart rhythm.

The cat was monitored very closely and continuously reassessed. Perfusion showed some improvement following the initial bolus, after which the cat was assessed to be mildly to moderately hypovolaemic. A further smaller bolus (10 ml/kg) of saline was administered. Serum potassium concentration was rechecked approximately 30 minutes after the initial emergency database and was improving in keeping with clinical progress.

Clinical Tip

Stabilization continued in this vain until the cat’s clinical condition had markedly improved with a stable cardiovascular system and much more appropriate mentation. The cat was then sedated for urethral catheterization using ketamine (2 mg/kg i.v.), midazolam (0.2 mg/kg i.v.) and a further dose of methadone (0.1 mg/kg i.v.). Intravenous fluid therapy was continued at 6 ml/kg/hr in the interim. A further two boluses of ketamine were required subsequently to complete the procedure. Catheterization was performed using a 5-French MILA® Tomcat urethral catheter (MILA International, inc., Erlanger, Kentucky, USA) (Fig. App2.2) that was connected to a urine collection bag (Closed System Drainage Set (Drainset)®, Infusion Concepts, Halifax, UK) (Figure App2.3) in a closed system (see p. 296).

Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

Following urethral catheterization, the cat was maintained on a 2.5% glucose saline solution at an empirical rate of 8 ml/kg/hr initially with close monitoring of urine output and hydration parameters. Analgesia was continued in the form of buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg i.v. q 6 hr) and potassium supplementation was provided as needed. Blood glucose, potassium, urea and creatinine concentrations were monitored intermittently and glucose supplementation stopped when appropriate. The urinary catheter was removed after being in situ for 36 hours, by which time the azotaemia had also resolved and the urine appeared grossly normal.

The cat was subsequently discharged approximately 24 hours later after he had demonstrated normal urination. Meloxicam (0.3 mg/kg s.c.) was administered prior to discharge, at which time the cat had been nonazotaemic for 48 hours.

Clinical Tip

Clinical Tip

Nursing Aspect

Following urethral catheterization, cats require close attentive monitoring and nursing. With respect to feeding, the priority in the short term is to tempt them to eat and the author is happy to offer these cats highly palatable foods rather than attempt to enforce a prescription urinary support diet. However, these cats have many short-term reasons to be inappetent (hospitalization, indwelling urethral catheter, Elizabethan collar) and force-feeding is both unnecessary and likely to induce food aversion; it should therefore be avoided.

Indwelling urethral catheters and closed collection systems need to be checked regularly to ensure that they remain in place, are not leaking and have not become blocked or disconnected. In addition, usual standards of care with respect to TLC, clean dry bedding and gentle handling are important.

Canine urethral obstruction

Mechanical urethral obstruction is considerably less common in dogs than cats but the same principles apply with respect to management of the emergency patient. This section will highlight some notable features of the canine condition.

Canine urethral obstruction may occur due to urolithiasis, blood clots, strictures, neoplasia, severe urethritis or penile fractures. In male dogs the urinary bladder may also become trapped in a perineal hernia. Transitional cell carcinoma is the most common cause of urethral obstruction in female dogs, while obstructive urolithiasis is more common in males. Uroliths that become lodged in the urethra may be flushed into the bladder by retrograde hydropulsion for subsequent medical dissolution or removal (surgical or nonsurgical) (see p. 298); occasionally urethrotomy may be required.

Struvite (radioopaque) uroliths are the most common type in dogs in general, and occur more commonly in female dogs. Unlike cats, these stones are typically associated with urease-producing bacterial infections. Calcium oxalate (radioopaque) uroliths are more common in male dogs than females, especially if neutered or overweight. Canine breeds at increased risk of calcium oxalate urolithiasis include the Yorkshire terrier, the Lhasa Apso, the Miniature Schnauzer and the Shih Tzu, along with various other small breeds. It is noteworthy that many of these breeds also appear at increased risk of struvite urolithiasis although the latter is also seen for example in the Cocker Spaniel and mixed breed dogs.

Urate (radiolucent) uroliths are most often identified in the Dalmatian, but an increased incidence is also reported in the English Bulldog. Urate stones in other breeds may be secondary to a portosystemic shunt causing impaired uric acid and ammonia metabolism; this is especially common in the Yorkshire terrier. Cystine (radioopaque) uroliths are seen in young to middle-aged dogs and occur most commonly in the Dachshund, the Staffordshire bull terrier, the English Bulldog and the Newfoundland.

It should also be remembered that dysuria in dogs may also be the result of prostatic enlargement, for example due to acute bacterial prostatitis or abscessation. Haemorrhagic or purulent fluid may drip from the penis and defecatory tenesmus may occur. These dogs often have a stiff gait and may be painful on caudal abdominal palpation. Rectal examination reveals prostatomegaly and pain on palpation. Occasionally systemic signs of lethargy, pyrexia and even sepsis may be seen.

Acute Renal Failure and Leptospirosis

Acute renal failure

Theory refresher

Acute renal failure (ARF) refers to a rapid decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), the consequences of which include accumulation of uraemic toxins and metabolic waste products, and dysfunctional fluid, electrolyte and acid–base homeostasis. The kidneys normally receive 20% of cardiac output, making them especially susceptible to ischaemic and toxic injury.

Causes

ARF may occur due to prerenal, postrenal or, most commonly, intrinsic renal causes.

Prerenal renal failure

Prerenal disease is the result of decreased renal blood flow, usually due to generalized hypoperfusion resulting from severe dehydration, hypovolaemia from other causes, or other forms of shock. Prolonged prerenal azotaemia may result in structural injury and irreversible intrinsic renal failure. It is essential to correct prerenal azotaemia before performing interventions that may predispose patients to further renal injury (e.g. general anaesthesia, nephrotoxic drugs).

Intrinsic renal failure

Intrinsic renal failure is the result of renal parenchymal injury. It may occur as a result of ischaemia, glomerular disease or tubular disease, and is characterized by azotaemia with isosthenuria (urine specific gravity 1.007–1.015). Toxins, including nephrotoxic drugs, are the most common cause in companion animals, although it is noteworthy that in most cases the diagnosis is one of association (i.e. between a compatible history and the development of ARF) without definitive proof. In some cases there is no compatible history and the diagnosis remains entirely presumptive.

Toxins associated with ARF in companion animals include grapes and raisins (dogs), lilies (cats), vitamin D (ARF due to hypercalcaemia) and ethylene glycol (see Ch. 30). Drugs with the potential for significant nephrotoxicity include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and aminoglycoside antimicrobials, although a large number of other drugs have been implicated. ARF may also occur as a result of primary traumatic injury (rare) as well as in syndromes such as heatstroke, sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Leptospirosis (see below) is probably the most commonly recognized infectious cause of ARF. Pyelonephritis may also cause ARF and most commonly occurs as a result of ascending lower urinary tract infection secondary to bacterial cystitis. Clinical signs may include lethargy, inappetence, vomiting, pyrexia and renal pain. Pyelonephritis may also occur secondary to haematogenous spread of bacteria.

Postrenal renal failure

Postrenal causes of ARF involve obstruction and/or rupture of the urinary tract. Although animals with postrenal abnormalities can have severe azotaemia, in most cases irreversible intrinsic renal injury does not occur if the cause is treated early. Ureteral obstruction due to calcium oxalate uroliths is increasingly recognized as a cause of ARF in cats.

Phases and progression

ARF is typically classified as being oliguric, anuric or polyuric based on the amount of urine being produced and this classification is important with respect to both management and potential prognosis. In an adult animal, oliguria is typically defined as urine output of less than 0.5–1 ml/kg/hr and polyuria as urine output of more than 2 ml/kg/hr. In general, a normal animal that suffers sufficiently severe renal injury will first become oliguric, which may or may not then progress to anuria. Conversion from oliguria or anuria to polyuria does not necessarily equate with recovery of the kidneys; however, it is an encouraging sign and also greatly facilitates patient management. In the author’s experience, polyuria is associated with a better outcome, at least with respect to discharge from the hospital.

Polyuria must be treated with appropriate intravenous fluid therapy to match urine output; these animals are unable to concentrate their urine in the face of inadequate fluid intake and will become dehydrated. Once the patient is stable, fluid therapy can be tapered by 10–20% each day as long as urine output decreases at a similar rate and azotaemia does not worsen. Animals that survive to discharge are likely to retain a degree of azotaemia, which may or may not then fully resolve over the subsequent weeks.

Treatment

ARF carries a guarded prognosis but treatment is designed to support the patient in order to allow as much time as possible for the kidneys to recover. Management involves:

Treatment of ARF is further described in Case example 2.

Clinical Tip

Leptospirosis

Theory refresher

Leptospires are filamentous spirochaete bacteria that are maintained in nature by subclinically infected wild and domestic reservoir hosts. Direct transmission occurs through contact with infected urine, venereal and placental transfer, bite wounds or ingestion of infected tissues; indirect transmission occurs through contaminated water sources, soil, food or bedding. Recovery from clinical disease depends on an appropriate antibody response but recovered dogs may excrete organisms intermittently in urine for months after infection (the organism does not replicate outside the host).

The incidence of classic canine leptospirosis caused by Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae or L. canicola decreased dramatically with the widespread use of vaccination. However, the incidence of canine leptospirosis has risen again due to an increasing prevalence of serovars that are not commonly included in vaccinations. Clinical cases of leptospirosis in cats are reported infrequently as cats are resistant.

Clinical findings

Leptospirosis is a multisystemic disease with a wide variety of possible clinical signs and clinicopathological abnormalities that are likely to be related to the virulence of the specific serovar and the age and immune status of the host. Peracute infections may occur with massive leptospiraemia and possible death with minimal signs.

Acute and subacute infections may manifest with a variety of nonspecific clinical signs as well as one or more of the following:

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of leptospirosis is typically made on the basis of compatible history and clinical findings, and demonstrating high initial or convalescent serum antibody titres. Titres (initial) can be negative in the first 7–10 days of acute illness and testing may need to be repeated once or twice, 2–4 weeks apart (convalescent). It is noteworthy that dogs with positive titres generally cross-react to a variety of serovars and the serovar with the highest titre is interpreted as belonging to the infecting serogroup. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis can be performed on urine collected prior to the instigation of treatment and may provide a more rapid diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment of leptospirosis involves appropriate supportive therapy for the individual patient (e.g. for dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, renal failure or hepatic injury) and specific treatment of the infection. Treatment of leptospirosis is biphasic. Penicillin-derived antibiotics are used for 2 weeks to treat circulating leptospiral organisms; preparations for intravenous administration are readily available and are of use in the early stages when inappetence is likely. This phase of treatment is then followed by a 2-week course of a tetracycline-derived antimicrobial.

Case example 2

Presenting Signs and Case History

A 3-year-old female neutered Labrador retriever presented with a 2-day history of lethargy, depression, anorexia and vomiting. The owner was not sure how much the dog had been drinking; however, she reported that the dog appeared to be urinating less often. There was no known history of drug administration and the dog had received appropriate vaccination including against L. icterohaemorrhagiae and L. canicola. Scavenging was a possibility as the dog received daily walks during which she was often let off the lead and out of sight, and she also had free access to the owner’s garden. No other significant history was reported.

Major system examination

On presentation the dog was depressed but ambulatory. Heart rate was increased (132 beats per minute) but cardiovascular examination was otherwise unremarkable. Mucous membranes were mildly hyperaemic and appeared jaundiced; capillary refill time was approximately 1 second. Respiratory rate was increased at 36 breaths per minute but there was only a mild increase in effort and auscultation was appropriate. Abdominal palpation was unremarkable and the bladder could not be palpated. Rectal examination was unremarkable but the dog was mildly hypothermic (37.0°C). Doppler (systolic) blood pressure was normal at 140 mmHg.

Emergency database

An intravenous catheter was placed in a cephalic vein and blood obtained via the catheter for an emergency database. This revealed high-normal manual packed cell volume (PCV) (52%, reference range 37–55%) and serum total solids (TS) (66 g/l, reference range 49–71 g/l). Mild hyperkalaemia (5.8 mmol/l, reference range 3.6–4.6 mmol/l) and mild hyponatraemia (136.1 mmol/l, reference range 140.0–153.0 mmol/l) were identified. Peripheral blood smear examination revealed a moderate thrombocytopenia, unremarkable red blood cell morphology, and a subjective moderate mature neutrophilia. The dog was found to be severely azotaemic (blood urea nitrogen 60 mmol/l, reference range 3.0–9.1 mmol/l; creatinine 900 µmol/l, reference range 98–163 µmol/l) and moderately hyperphosphataemic (4.20 mmol/l, reference range 0.8–2.0 mmol/l) with marked hyperbilirubinaemia (95 µmol/l, reference range 0–2.4 µmol/l). Brief abdominal ultrasonography revealed a very small bladder and no free fluid was detected.

Case management

The severity of the azotaemia was consistent with either a severe renal or a postrenal azotaemia but there was no evidence to support the latter; a prerenal component was possible. In addition, the dog was not anaemic as would be expected if she had been suffering from chronic renal failure with an acute crisis. Given all the findings in this case, a diagnosis of ARF was made. There was no evidence of haemolysis and the hyperbilirubinaemia was presumed to be posthepatic or hepatic in origin. These two findings, in addition to the moderate thrombocytopenia, were suggestive of possible leptospirosis and a sample was submitted for serology.

A soft indwelling Foley urethral catheter was placed under sedation (butorphanol 0.3 mg/kg i.v., diazepam 0.2 mg/kg i.v.) using strict aseptic technique and barrier nursing, and the bladder emptied. The catheter was connected to a closed urinary collection system. Urinalysis revealed: isosthenuria (urine specific gravity 1.013); marked bilirubinuria with mild glucosuria, proteinuria and haematuria; and an increase in red and white blood cells on sediment examination. The dog was not felt to be hypovolaemic but moderate dehydration (7%) was suspected, and she was started on 0.9% sodium chloride (normal, physiological saline) at 10 ml/kg/hr to provide rehydration and maintenance requirements over approximately 8 hours (see Ch. 2). Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg i.v. q 8 hr) was started for possible leptospirosis, and antiemetic therapy (maropitant 1 mg/kg s.c.) and omeprazole (0.7 mg/kg slow i.v. q 24 hr) were administered.

After 10 hr of fluid therapy, there had been minimal urine production. The dog was therefore given a bolus of furosemide (4 mg/kg i.v.), and 1 hour later her urine output had increased to 1.0 ml/kg/hr. Mannitol (1 mg/kg i.v over 30 minutes) was administered and the dog was started on a constant rate infusion of furosemide (0.3 mg/kg/hr). The dog was monitored closely for signs of fluid overload, in particular with respect to respiratory rate and effort, and regular monitoring of blood pressure and blood parameters performed.

Over the following 12 hours, the dog remained oliguric and despite appropriate tapering of fluid therapy and further diuresis, began to show signs of fluid overload in the form of chemosis and peripheral subcutaneous oedema. Her azotaemia and hyperbilirubinaemia also worsened. The dog’s owners were advised at this point that she either needed to be referred for peritoneal dialysis (haemodialysis was not available) or sadly euthanased on welfare grounds, having failed to respond to medical management. The owners elected for the latter which was done without further delay. Postmortem was declined but the results of Leptospira serology were subsequently received and confirmed the suspected diagnosis (microagglutination test (MAT) positive for Leptospira copenhageni at 1/3200).

Clinical Tip