chapter 23 Driving and community mobility as an instrumental activity of daily living

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

1. Define driving and community mobility as instrumental activities of daily living.

2. Identify the role of occupational therapy in addressing driving and community mobility issues at different stages of rehabilitation and recovery for the stroke survivor.

3. Understand the legal issues associated with involvement of driving issues and how to manage liability risks.

4. Identify performance skill deficits related to a stroke and client factors that can interfere with the occupation of driving.

5. Understand the current accepted practice for a comprehensive driving evaluation for the stroke survivor.

6. Identify resources for information, education, and referral in addressing driving and community mobility as an instrumental activity of daily living.

driving and community mobility

driver rehabilitation therapist

occupational therapy generalist in driving

occupational therapy specialist in driving

Following a stroke, the occupational therapist considers the many types of occupations in which the client engages. The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework1 defines instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) as activities “to support daily life within the home and community that often require more complex interactions than self-care used in ADL.” Driving and community mobility are included within the domain of occupational therapy (OT) and in the profession’s scope of practice.1 Community mobility is defined in the framework1 as “moving around in the community and using public or private transportation, such as driving, walking, bicycling, or accessing and riding in buses, taxi cabs or other transportation systems.” The OT practitioner during evaluation and intervention considers the client’s own perspective of how driving and community mobility meets his or her needs and interests.

Evaluation and intervention for functional and community mobility should center on safe mobility for the patient in the home and in the community for meeting his or her life needs and interests. For some following a stroke, driving may play a major role in getting to and from a job or it may be the means of obtaining nourishment and medications. Driving a motor vehicle is a common form of transportation used by clients recovering from a stroke, and therefore, addressing driving and/or community mobility is a crucial IADL that must be addressed by OT.

In 2005 American Occupational Therapy Association’s (AOTA) Representative Assembly adopted an official statement on Driving and Community Mobility.36 The document stated that “All occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants possess the education and training necessary to address driving and community mobility as an IADL. Throughout the evaluation and intervention process, all practitioners recognize the impact of clients’ aging, disability, or risk factors on driving and community mobility. Through the use of clinical reasoning skills, practitioners use information about client strengths and weaknesses in performance skills, performance patterns, contexts, and client factors to deduce potential difficulties with occupational performance in driving and community mobility.” In the continuum of activities of daily living (ADL), the occupational therapist must consider mobility in the rehabilitation process of the patient recovering from a stroke.

As with all other ADL and IADL, the occupational therapist considers the occupation of driving for a client with the holistic approach of examining the client factors, the performance skills, the performance patterns and habits, the contextual and environmental factors, and the activity demands. A determination is made as to any difficulties or issues in these areas that affect occupational performance for driving. Intervention is then structured to improve or enhance the problem areas prior to discharge from OT. If independent driving cannot be a short- or long-term goal for the client who is recovering from a stroke, then the occupational therapist must address the community mobility issues by examining the client’s resources in the community and assisting the client and family with good and safe transportation choices.

A century ago, individuals could walk to work, shops, friends’ homes, churches, and most other destinations. Today, with the primary mode of transportation being the personal vehicle and with the distance separating homes and businesses in the suburbs, few destinations are now within walking distance. Impairments and activity limitations caused by a stroke or age can further shorten distances traversable on foot. Reduced mobility in the community by an individual can result in a lower self-esteem, depression, and feelings of uselessness, loneliness, and unhappiness.

The performance skills necessary for safe driving begin to deteriorate around the age of 55-years-old and dramatically decline after age 75-years-old.27 Approximately 72% of strokes occur in persons older than 65-years-old. In addition to normal aging conditions, the brain damage from a cerebral infarct and its clinical manifestations can affect the person’s driving skills. The specific motor, sensory, and cognitive deficits depend on the location and severity of the cerebrovascular damage (see Chapters 1 and 18). This damage can cause one or more temporary or permanent impairments. Of the approximately 80% of persons who survive the initial period, 75% are left with residual perceptual-cognitive dysfunction.21 These or other impairments or additional client factors not related to the stroke may affect safe driving for this person. The occupational therapist must evaluate each patient recovering from a stroke individually, because the location and nature of the stroke can produce different problems and deficits, and everyone will have a different occupational profile.

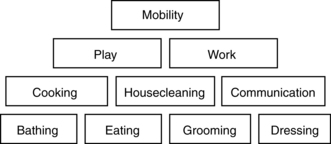

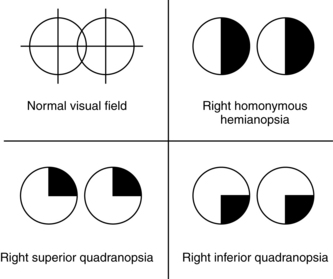

Achieving or not achieving independent transportation for a stroke survivor can impede or affect greatly all other IADL. Carp,5 a California psychologist who has studied older drivers, used the conceptual model in Fig. 23-1 to detail the determinants of emotional and social well-being. Life maintenance needs to include nourishment, clothing, medical care, banking, and pharmaceuticals. Community resources for meeting these needs include grocery and drug stores, department stores, physician’s offices, and banks. If a person has no access to these resources, independent living becomes nearly impossible. Other needs, labeled higher order, include needs for social interaction, usefulness, recreation, and religious experience. Carp’s research of investigative studies supported the idea that “if life is to have an acceptable quality, higher-order needs such as those expressed in trips for relaxation and enjoyment and religious activities are also essential.”

Figure 23-1 The determinants and dynamics of emotional and social well-being.

(Modified from Transportation Research Board—National Research Council, Special Report 218, Transportation in an aging society, Washington, DC, 1988.)

The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework1 supported Carp’s ideas by articulating that OT has a contribution “to promote the health and participation of people, organizations, and populations through engagement in occupation.” The Framework1 continued that “all people need to be able or enabled to engage in the occupations of their need and choice, to grow through what they do, and to experience independence or interdependence, equality, participation, security, health and well-being.”

The threat of losing a driver’s license may have devastating effects on a stroke survivor’s motivation to maintain independence in other areas of daily living. The primary fear of elderly persons is not death but losing their independence and becoming burdens to their loved ones.3 Carp5 stated the following:

Loss of license is a serious fear among drivers, a threat to their autonomy, usefulness, and self-esteem . . . A century ago people could walk to work, shops, others’ homes, religious services, and most destinations. Few destinations [today] lie within walking distance for any person . . . Mobility is a key influence on the congruence term in the model . . . Satisfaction of life-maintenance and higher order needs require going out into the community . . . The loss of a license would mean inability to go where they needed to go and therefore meet their needs independently . . . Just as receipt of the first driver’s license is an important rite of passage to adulthood and independence, license loss formally identifies one as “over the hill.”

Driving or being independent in community mobility by another means is inseparable with being one’s own person and taking care of oneself. The issue is more than just one of losing mobility. Rendering an opinion as to whether the patient recovering from a stroke is capable of driving has lasting implications. Driving is one of the more complex ADL and therefore must be taken with careful thought and serious consideration by using the best critical thinking methods by the rehabilitation team. Law enforcement officers or driver licensing personnel cannot address this issue effectively, which has potentially dangerous consequences to the stroke survivor or to pedestrians or other road users. Elderly drivers who do not self-regulate effectively are not detected easily with standard licensing procedures.21 Furthermore, doubt exists as to whether most licensing staffs have the skills necessary to detect these problem drivers.8

Driving and community mobility is a crucial activity of daily living skill

Community mobility is paramount to the patient recovering from stroke and attempting to maintain a productive lifestyle in the work, home, or social arenas. The occupation of driving and community mobility is such an important activity that it requires inclusion with other ADL issues in OT. If the rehabilitation team addresses safety in functional mobility or safety in the kitchen for the stroke survivor, then safety in driving demands addressing. If driving and community mobility is within the domain of OT, then it is the occupational therapist’s responsibility to address it as with any other ADL such as dressing, cooking, bathing, and functional ambulation. “Each area of mobility requires a certain skill level in occupational performance. A hierarchy of skills dictates the order in which each area is addressed. Mobility in basic activities of daily living (BADL) is first, followed by mobility in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Some occupational therapy (OT) goals for motor, sensory, perceptual, and cognitive functioning must be achieved prior to ADL training and specifically mobility training.”29

The occupational therapist should begin to discuss driving and community mobility early on in the stroke survivor’s rehabilitation and recovery intervention. Such discussion will lead to patient and family education and acceptance early to reinforce their responsibility and requirements in the process of the patient’s regaining independent driving or his or her need to investigate alternative transportation choices. The early discussion also will lessen the family’s stress and anxiety over the issue of driving for their family member, for they will not have to shoulder the burden of telling the person that he or she cannot drive and then dealing with an angry family member.

“As an activity that contributes to independence and quality of life, driving falls squarely within the province of occupational therapy practice,” Johansson stated.18 The discipline of OT has been given the role of evaluating clients regarding their ability to drive a motor vehicle primarily because of the wide spectrum of physical, cognitive, and perceptual skills that fall under the realm of OT.19 In addition, occupational therapists have a background in psychosocial dysfunction that can be key in giving the therapist the necessary therapeutic attitude and approach to this sensitive issue to understand how it can affect the psychosocial and emotional well-being of the patient. The AOTA has identified older driver evaluation and retraining as an important specialty area for practitioners to consider because of the broad approach of the profession to evaluation and treatment. Eberhard, a former senior research psychologist at the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration, said that he “envisions a key role for the OT profession in maintaining elders’ automotive proficiency. OT practitioners have clear insights into the need for mobility. They have the skills to assess functional mobility and the skills to enhance it.”26

In all settings, the occupational therapist is concerned with the performance level of ADL, with mobility being at the top of the pyramid (Fig. 23-2). The daily living task of functional mobility involves bed and wheelchair mobility, transfers, and functional ambulation while performing activities. Functional mobility tasks allow an individual to function independently by moving from one place to another. Successful community mobility allows a person to move about his or her community and environment and the person’s ability to drive or use other transportation choices may make the difference in the stroke survivor returning to his or her living situation prior to the stroke. Because persons of all ages can suffer a stroke, driving or transportation choices as a community mobility issue must be on the ADL repertoire for the occupational therapist to explore, evaluate, and provide intervention as necessary. The occupational therapist must understand the significance of community mobility for the total well-being of the client. A holistic view presents driving as a vital link between the client and the outside world.

Rehabilitation team’s responsibility

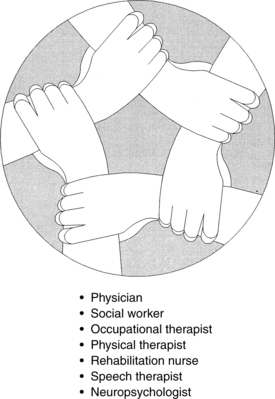

The entire rehabilitation team must address the issue of driving or transportation for the stroke survivor, with members addressing the issue within their own professional expertise (Fig. 23-3). The rehabilitation team must get involved with this issue because they are concerned with the overall functioning of the client and his or her resulting quality of life after a stroke. They are in the best position to identify any existing or potential contributors to driving risk. In addition, families need assistance and guidance with this highly sensitive issue before they take the family member home. The rehabilitation team must define a fair and reasonable course of action. They must weigh client-physician or client-therapist confidentiality versus public safety. The social and ethical dilemma faced by medical professionals and the department of driver licensing is to strike a balance between protecting the person’s privilege to drive and the safety of other road users, including pedestrians, other drivers, and vehicle passengers.

Figure 23-3 Driving should be addressed as appropriate by each member of the rehabilitation team following the same policies and procedures. The process depends on good communication among the team members.

Each team member has a role and responsibility and should be ready to address related issues as they arise. For example, the physician, as the head of the rehabilitation team and medical authority, must take a leading role with this issue. The physician should be the first to inform the client and family that because of its complexity and demand of high functional levels of skills, driving will be one the last activities addressed in the person’s rehabilitation and recovery.

Other team members also play a role in addressing the occupation of driving in relation to their specific area of knowledge and skill. For example, the nurse can provide a list of medications with which the client will be discharged home and note any side effects that could affect safe driving. The speech-language pathologist may address the need for a client with aphasia to begin carrying a personal identification card, so that if he or she is involved in an accident or is stopped by a police officer, the card would explain the speech difficulties. The speech-language pathologist also may inform the occupational therapist of any language deficits that might be contraindicated for safe driving. For example, if the stroke survivor has global aphasia and needs to be evaluated for driving using driving aids, he or she may have difficulty with verbal instructions on a new task, with directions, or with reading road signs. The physical therapist can reinforce the reality that the person with dense right hemiplegia will not be able to use the right foot for driving because of lack of necessary motor and sensory function. The physical therapist can also work on the goal of the client entering and exiting a vehicle with or without an orthotic device. The social worker can counsel the family to reinforce the team’s discharge recommendations related to referral for a formal driving evaluation if deemed necessary after discharge and can assist the OT Generalist in Driving and the family members in identifying alternative transportation choices in their specific community environment.

The OT practitioner will play the largest role and the greatest responsibility in addressing the occupation of driving for the stroke survivor. The roles of the OT practitioner have been defined in an AOTA online course entitled Driving and Community Mobility for Older Adults: Occupational Therapy Roles:16 “Occupational therapists are already educated and trained to address many of the important issues associated with driving and community mobility, and they must be ready to take on the role of the occupational therapy Driving and Community Generalist whatever the practice setting. In addition, an increasing number of occupational therapists must prepare and be available to assume the role of the Occupational Therapy Driver Rehabilitation Specialist.” The Occupational Therapy Driving and Community Mobility Generalist (Generalist in Driving) is defined as “all occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants with all the education, training and credentials necessary to practice occupational therapy but who do not possess specialized training and experience in driver evaluation or driver rehabilitation.” The Occupational Therapy Driver Rehabilitation Specialist (Specialist in Driving) is defined as occupational therapists and OT assistants with all the education, training, and credentials of an OT practitioner in addition to the advanced knowledge and skills in the specialty field of driver evaluation and driver rehabilitation (including intervention, vehicle modifications, and adapted driving equipment).

While the OT Generalist in Driving begins addressing issues and skills as they relate to the activity of driving early on for the stroke survivor, it may be necessary to seek the expertise of an OT Specialist in Driving at some point for an on-road evaluation. The physician should inform the stroke survivor and the family that the client should not drive until the team and the OT Generalist in Driving or Specialist in Driving has considered all aspects necessary to evaluate the occupation of driving.

Occupational therapists’ changing role with the stroke survivor

“Occupational therapists are responsible for all aspects of OT service delivery and are accountable for the safety and effectiveness of that service delivery process.”1 The occupational therapist’s unique background and training in evaluation and intervention in the performance skill areas of motor and praxis skills, sensory-perception skills, emotional regulation skills, cognitive skills, and communication and social skills coupled with the understanding of client factors and environment and contextual factors assist the therapist to understand all issues related to the occupation of driving. In addition, the occupational therapist’s background and understanding of psychological and emotional issues assists the therapist greatly in handling the delicate issue of driving when just speaking of driving can cause anxiety, defensiveness, and other psychological stress for not only the stroke survivor but also family members. The occupational therapist’s role many times is to educate, listen, and counsel not only the client but also family members. The occupational therapist’s keen ability to look at the “whole person” is important to the process in considering all aspects of engagement in community mobility, including driving, and how all the different aspects are interrelated and have transactional relationships.

The occupational therapist’s role changes during different phases as the stroke survivor moves through acute care hospitalization, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, discharge, and community follow-up. As the person moves through these phases, the occupational therapist addresses issues of driving relevant to each phase. The level of involvement varies during each phase. Driving or community mobility should be an established IADL goal early on with all other ADL goals and have a well-defined intervention plan toward the stroke survivor’s stated outcome with this activity. The outcome regarding this IADL is the end-result of the OT process throughout each recovery stage with the stroke survivor. Each occupational therapist that the stroke survivor sees along the continuum of care must understand his or her role and responsibility at the level that he or she treats the client.

Acute care phase

During the initial hospital phase following a stroke, the role for the occupational therapist is primarily one of inquiry and fact finding. One of the most common questions initially asked by a person in this phase is “Can I drive again?” or “When will I be able to drive again?” The therapist must be able to answer the question when asked and to speak with confidence about how this activity will be addressed along the continuum of care. The therapist can inquire whether the stroke survivor had been a licensed driver before and what was the frequency and circumstances of driving. For example, did the person drive to work or drive his or her children to school? Does the person live in a rural or suburban area? Was the person the primary driver in the family? Did the person drive intrastate, interstate, or just locally? Is the person at a stage at which he or she already had begun to limit driving to daylight only or within short distances of home? Is independent driving a goal for the person now? If the client has memory, cognitive, or speech deficits, the family may need to be consulted to obtain or verify the information given by the client. If the stroke survivor passes through the hospital phase quickly, then these questions may need to be explored more completely by the therapist in the next phase. The point is that driving should be addressed early and as commonly as dressing, grooming, and other mobility issues. Whether the appropriate time is in the acute care phase or the rehabilitation phase, the therapist should be equipped to address driving in an appropriate way.

Rehabilitation phase

As the stroke survivor moves into the rehabilitation phase, the foregoing information would be passed on to the rehabilitation unit therapist. The primary rehabilitation occupational therapist would pick up the issue by addressing driving as an IADL in the initial evaluation for an intervention plan with the stroke survivor as for other ADL such as dressing, bathing, and cooking. To address driving as an IADL and assess factors that may affect safe driving, the occupational therapist requires an understanding of all factors and skills involved in driving and activity demands of driving. With an understanding of the level of skill performance demanded in the driving task, the occupational therapist can include intervention, with driving in mind, much as the therapist would for other ADL tasks.

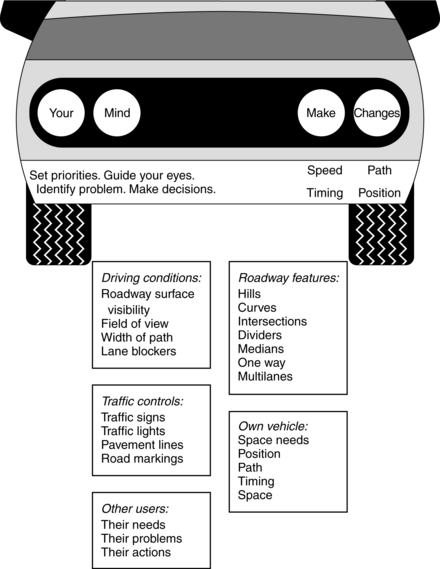

Driving an automobile is a complex task involving a hierarchy of skills. Adequate motor response and physical control of the vehicle are essential skills but are secondary to accurate perception and understanding of ever-changing traffic environments and unpredictable situations. A driver processes information and makes conscious or unconscious decisions using (1) environmental information such as traffic lights, road markings, road signs, and other road users; (2) attention and perceptual mechanisms using visual search, spatial relations, and time and space management; (3) reasoning, problem-solving, and planning to analyze each situation and understand cause and effect; and (4) response by physical control, adjustment, and compromise. Table 23-1 gives an overview of occupational performance in driving.

Table 23-1 Occupational Performance in Driving for a Stroke Survivor

| BASIC SKILL AREAS | PERFORMANCE FACTORS |

|---|---|

| Physical demands | |

| One functional upper extremity and lower extremity | Operation of primary/secondary vehicle controls with or without adaptive equipment |

| Visual demands | |

| Visual acuity: 20/40 in at least one eye | Reading/understanding road signs Reading odometer and dash gauges Can influence depth perception Identification of stimuli seen in side vision |

| Peripheral vision: >130 degrees of total field of vision with both eyes | Awareness of stimuli in side vision Visual scanning More useful than visual acuity |

| Good eye function/quality of vision: disease or age-related problems | Cataracts: poor glare recovery, poor night vision Diabetic retinopathy: blind spots, see incomplete driving scene Glaucoma: blurriness, blindness |

| Visual-perceptual demands | |

| Spatial relations | Reading/responding to road signs/markings; perception of space around car |

| Figure-ground | Maneuvering through parking lot; finding road signs in a visually busy environment |

| Visual closure | Discrimination of high- and low-priority issues; seeing the whole picture with incomplete cues |

| Visual memory | Time and space management; delay response time |

| Form constancy | Visual analysis in busy and/or low-light environments |

| Visual discrimination | Analysis of road signs by shape and color |

| Cognitive demands | |

| Strategic skills | Choice of route Time of day to take trip Planning a sequence of trips or stops Evaluating general risks in traffic (under varying traffic, road, and weather conditions) |

| Tactical skills | Anticipatory driving behavior Adjusting speed to varying traffic conditions Quick decisions related to expected or unexpected situations Judgment/reasoning to estimate risks |

| Operational skills (combines physical, visual, and cognitive) | |

| Attention: | |

| Focused | Responding to specific stimuli |

| Sustained | Maintaining focus during continuous driving |

| Selective | Maintaining focus in face of distractions |

| Alternating | Mental flexibility to focus between several tasks requiring attention |

| Divided | Responding simultaneously to multiple tasks or multiple task demands |

| Complex reaction time (appropriateness and timeliness of response) | |

| Memory skills | |

| Recent | Remembering destination, path to take, and event |

| Procedural | Subconscious operation of vehicle controls as old, learned behavior |

Preexisting or progressive age-related conditions

In addition to conditions or problems associated with the primary diagnosis of a stroke, the therapist should explore other preexisting medical or aging conditions that require attention. Stressel39 writes the following:

In general, aging results in the normal deterioration of the physical, cognitive, and visual functioning. People age at different rates, and age-related problems that are known to affect driver performance do not occur in all people at the same rate or to the same degree. The rate of decline is very individualized, and chronological age is not a good predictor of an individual’s capabilities. As the prevalence of disease increases with age, it becomes more difficult to differentiate between functional losses due to the effects of disease versus functional loss associated with the aging process. The process of aging is inescapable. Age-related changes are characteristically detrimental in nature, cumulative and irreversible over time, but often lack sharply defined points of transition. Changes begin at different chronological ages, progress at varying rates, and do not affect each body system in the same way. Although some diseases and deterioration may present themselves suddenly, generally there is a slow accumulation of deficits.

Several examples to illustrate this point are the stroke survivor who has had insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes for 25 years. He was diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy and had two laser surgeries for treatment. Another stroke survivor has been on kidney dialysis for two years after having an allergic reaction to a medication that damaged the kidneys. Each of these preexisting conditions, separate from any deficits related to the stroke, could increase risk factors associated with safe driving and should be addressed separately in terms of the affect on the driving task. Box 23-1 lists other examples of nonstroke factors to consider. Communication with the family, rehabilitation physician, neurologist, and perhaps the primary care physician is important to synthesize the patient’s entire medical history and consider all potential client factors that may affect the stroke survivor returning to independent driving.

Box 23-1 Nonstroke Medical Factors That Potentially Can Affect Driving Safety

Previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attack

Previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attack

Visual problems such as cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, or diabetic retinopathy

Visual problems such as cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, or diabetic retinopathy

Surgeries that caused limitations such as hip/knee replacements or cervical laminectomy

Surgeries that caused limitations such as hip/knee replacements or cervical laminectomy

Respiratory conditions such as emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Respiratory conditions such as emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Other neuromuscular conditions such as polio, multiple sclerosis, or muscular dystrophy

Other neuromuscular conditions such as polio, multiple sclerosis, or muscular dystrophy

Polypharmacy: multiple medications with interacting effects; prescription and over-the-counter looked at separately and in synergistic combination

Polypharmacy: multiple medications with interacting effects; prescription and over-the-counter looked at separately and in synergistic combination

Psychological diagnoses such as bipolar disease, depression, or schizophrenia

Psychological diagnoses such as bipolar disease, depression, or schizophrenia

After driving and community mobility are addressed in the initial gathering of the occupational profile, the second stage of involvement for the occupational therapist during the rehabilitation period is the crucial area of education of the stroke survivor and the family regarding individual responsibility in the whole process. In this phase, the client must be informed how, when, and by what process driving and community mobility will be addressed. The therapist should be able to speak with authority and confidence of the process of addressing driving, the timing, the referral procedure if referral to an OT driver rehabilitation specialist is necessary, and the available resources. The therapist must speak with first-hand knowledge of the value of the on-road evaluation, if necessary, so that the client and family will equally value the comprehensive driver evaluation services of the OT Specialist in Driving. The stroke survivor and family should know at that point that the client cannot drive until a conclusion has been reached by the collaboration of the OT practitioner and the rehabilitation team. By the OT practitioner giving the client the information at an early stage, the client will be prepared and more cooperative in moving through the process and knowing what to expect along the way. Speaking specifically about the activity of driving will help the client understand that the intervention plan includes treatment along the continuum of care that will improve and enhance his or her performance skills related to driving an automobile.

Driving is one area that scares many family members of stroke survivors. They need to be informed as well, so they can provide the necessary assistance and support for the client throughout the process in regards to the issue of driving. The family can begin dealing with the reality and can plan for alternative transportation choices for the stroke survivor until it has been finally determined that they have the driver competency to begin driving again. This should lessen the family’s fears and anxiety and bring them into an active role in the process while allowing them to remain in the background regarding the ultimate decisions about driving. In other words, the family cannot be blamed for the stroke survivor’s temporary or permanent loss of driving privileges. By addressing the driving issue in the medical setting, the family is relieved of having to address the issue themselves with the stroke survivor, which many times can cause frustration and emotional stress from the stroke survivor’s anger, lack of insight, or poor judgment.

Medical reporting with driver licensing authorities

Each state has licensing requirements and reporting laws. Many states do not require a driver to report a new medical episode resulting in disability between license renewals. Some states allow only a doctor to report a medical condition that may preclude safe driving. Other states may allow professionals such as a law enforcement officer or allied health professional or even nonprofessionals such as a neighbor or family member to report a driver’s medical condition or to raise a concern. Occupational therapists should investigate the requirements for the state in which they work to develop a consistent procedure to use with every client that includes a set policy approved by the administration and legal departments of the facility and understood by each team member. Many states have medical advisory boards to their departments of driver licensing that are good resources for licensing requirements and the medical reporting process.

The American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) at www.aamva.org is a nonprofit organization that develops model programs in motor vehicle administration, police traffic services, and highway safety. The AAMVA works with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to review Medical Advisory Boards and driver licensing renewal procedures throughout the United States. This information can be accessed from their website. The AAMVA also serves as an information and awareness resource regarding older driver issues.

That testing procedures in driver examination offices do not evaluate fully all skills related to driving is common knowledge, particularly when the driver may have a medical condition or deficit that is not physically obvious. Examiners may not have knowledge of an applicant’s diagnosis unless the person informs them or a physician provides written notification. These examiners do not have an understanding of possible implications of disability on driving skills. For example, a person with a complete right homonymous hemianopsia, which is a common vision deficit after a stroke, usually does not pass the visual requirements of most states for a minimum of 125 to 140 degrees of continuous field of vision. The typical methods of vision testing by driver licensing offices measure only visual acuity and not visual fields. A person can have 20/40 visual acuity, which is acceptable in most states; however, the driver examiner may never know the person has homonymous hemianopsia.

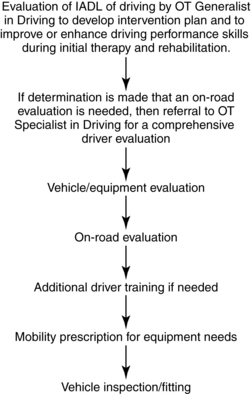

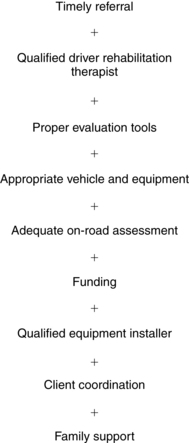

Predriving clinic screening

A comprehensive driving evaluation for a person who has had a stroke may include the steps illustrated in Fig. 23-4. The process for addressing driving and community mobility as an IADL starts during the initial OT in the acute care setting and continues through inpatient rehabilitation therapy, outpatient rehabilitation therapy, and beyond. Along this continuum of care, the occupational therapist should continue including the IADL of driving and/or community mobility until the conclusion is drawn and the outcome decided. A successful completion of this process depends on many factors that can influence the outcome, as noted in Fig. 23-5. A predriving screening by the occupational therapist should be completed prior to the client being discharged from inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient therapy. The purpose of the predriving screen near discharge is multifaceted. The OT Generalist in Driving should:

1. Evaluate for any residual deficits in the performance skill areas of motor and praxis skills, sensory-perceptual skills, emotional regulation skills, cognitive skills, and communication and social skills, and determine whether any of these deficits could or would interfere with driving performance skills.

2. Determine with the full team’s input if the client can begin driving or should not drive upon inpatient discharge, and document in the medical records that the client was informed of the conclusion.

3. Determine if a more in-depth driver evaluation by an OT Specialist in Driving is necessary, and begin the referral process.

4. Determine if the client can benefit from further therapy to improve and enhance his or her skills in outpatient therapy, and pass on the intervention goal of driving to the outpatient occupational therapist.

The inpatient and outpatient occupational therapist should have knowledge of the appropriate state licensing laws and understand the necessary level required in each performance skill area needed for safe driving so that the appropriate information can be passed on to the OT Specialist in Driving. For example, if the patient has left neglect or serious visual-perceptual deficits, these conditions are contraindicative for safe driving unless they resolve early. Another example is the field of vision requirement already discussed. If a stroke survivor has a complete homonymous hemianopsia, then the therapist should tell the client and family that a return to driving is not possible because of the requirements of the state unless the condition resolves itself enough to meet the field of vision requirements. Table 23-2 has examples of problem areas to note.

Table 23-2 Examples of Stroke-Related Deficits to Identify during Initial Assessment That May Impact Driving Performance

| DEFICIT | POTENTIAL ISSUES FOR FUTURE RETURN TO DRIVING |

|---|---|

| Left or right neglect | May not see or respond to road signs or markings; may ride to extreme right or left of lane; may miss turning lanes; will not look to affected side at intersections |

| Loss of field of vision | Will be surprised by unexpected stimuli or events that move into field of vision suddenly from blind area, may collide with something the driver did not even see such as a person stepping off a sidewalk or a car lane changing from the field loss side |

| Dense hemiplegia | May require adaptive devices to compensate for motor dysfunction in one or both affected extremities |

| Seizure | Most states have a required period of being seizure-free, with or without medication. |

| Complex regional pain syndrome type I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy) | Pain or strong medications may affect mood and be a distracting factor; associated motor deficits may require adaptive equipment for driving; posturing of the affected limb while driving is important. |

| Sensory-perceptual | Body positioning behind the steering wheel is difficult due to visual neglect or body imaging issues, inadequate spatial relations or time/space management, and poor depth perception, leading to short following distance and stopping distance, inadequate determination of speed and distance of approaching vehicle for making a safe unprotected left turn. |

| Communicate difficulties such as aphasia | Misreads signs or other road user cues; becomes distracted when attempting to talk |

| Impulsivity, poor inhibition | Responds or reacts without thinking or seeing the consequences; does not see the entire driving picture to make sound judgments and decisions |

| Denial, poor insight | Does not see or understand overall performance skill deficits or how the deficits interfere with safe driving; improvement difficult because he or she does not feel there is any need for improvement |

| Memory | May not remember where destination is or how to get there; becomes confused and anxious when cannot find street, misses a street, or is faced with a detour |

When structuring the predrive clinical screening, the therapist should be guided by common sense and evidence-based practice where applicable to use appropriate clinical tools and tests as they relate to driving. Although typical clinical tools and equipment in an OT department can be used for this screening, the therapist may need additional specialized equipment for more relevance to driving. Clients may be more cooperative with the clinical evaluation for the IADL of driving if they appreciate its relevancy to the driving task. For example, the client may feel frustrated and angry working on a puzzle or paper maze during the therapist’s predrive clinical screening but may understand the importance of a test that provides specific data related to driving such as reaction time, driving risk behavior assessed using a clinical tool to measure divided and selective attention, and a measuring of cognitive abilities for safe driving with a clinical tool that assesses memory, judgment, decision-making, attention, and motor speed abilities. The therapist should describe the relevance of any test given, so the client will be motivated to perform well on the test. The assessment of motor/praxis skills and sensory-perceptual skills is generally easy for the therapist to set up because the assessment and techniques used in these areas are similar to those used in other settings and with other disabilities. The difference is that the therapist must keep a mind set on the activity demands of driving as they do similarly with cooking, dressing, and other ADL they consider.

The therapist should attempt to use clinical tools and tests during this phase that have the most significance to the driving task. Box 23-2 lists some of the more common clinical tests. Additional tools and devices are available on the market that can be used in the clinic with driver-related tasks and have a degree of face validity and statistical correlation (Box 23-3).

Box 23-2 Examples of the Common Clinical Tests Used as Needed

Gardner Test of Visual Perceptual Skills

Gardner Test of Visual Perceptual Skills

Motor-Free Visual Perceptual Test—3

Motor-Free Visual Perceptual Test—3

Cognitive Linquistic Quick Test

Cognitive Linquistic Quick Test

Rey-Osterreith Complex Figure Test

Rey-Osterreith Complex Figure Test

Short Blessed Test or Mini-Mental Status Exam

Short Blessed Test or Mini-Mental Status Exam

Draw-a-Clock or Draw-a-Person test

Draw-a-Clock or Draw-a-Person test

Gross Impairments Screening Battery of General Physical and Mental Abilities (GRIMPS)

Gross Impairments Screening Battery of General Physical and Mental Abilities (GRIMPS)

Box 23-3 Clinical Evaluation Tools with Face Validity and/or Correlation to On-Road Driving Performance

Cognitive Behavioral Driver’s Inventory

Psychological Software Services

Engum and colleagues9 noted the following: “Knowing the patient’s diagnosis or pathology typically does not yield predictions about the patient’s ability to drive. . . . Even loss of brain mass is not deemed to be an exact predictor of driving skills . . . neuropsychological tests, which can detect gross organic impairment or provide useful catalogs of patients’ impairments and abilities, do not seem to assess driver potential.” The OT Generalist in Driving must collaborate with the OT Specialist in Driving to coordinate the tests and tools used, so duplication is not done.

Their four-year research project with more than 230 brain-damaged patients led to the development of the Cognitive Behavioral Drivers Inventory (CBDI). This inventory is designed to assess aspects of cognitive functioning such as attention, concentration, rapid decision-making, visual-motor speed and coordination, visual scanning and acuity, and shifting attention from one task to another. Their results demonstrated that more than 95% of the patients receiving passing scores on the CBDI were judged independently by an on-road driving test as safe to operate a motor vehicle. Conversely, all patients who failed the CBDI were judged as unsafe drivers in the independently administered road test.9 A subsequent study by some of the same authors in 1988 completed a double-blind test of the validity of the CBDI. Again, the authors found a high correlation between the results of the CBDI and the independent road test.8 Although the CBDI is psychometrically strong, it has no face validity. The CBDI is useful, but the Elemental Driver Simulator has face validity and may be better understood by patients as being relative to driving because it involves operating simulated primary car controls (Fig. 23-6).

Gianutsos,11 the originator of the Elemental Driving Simulator, stated, “road tests lack the basic psychometric requisites of tests—standardization, reliability and empirical validity.” She described the Elemental Driving Simulator as a “computer-based quasi-simulator that is based on objective, norm-referenced measures of the cognitive abilities regarded as critical for driving.” These cognitive abilities include mental processing efficiency, simultaneous information processing, perceptual-motor skills, and impulse control. The Elemental Driving Simulator also attempts to measure insight and judgment by comparing self-appraisal with performance. Research by Gianutsos11 and Engum and colleagues9 indicated a significant correlation in the Elemental Driving Simulator and CBDI. These researchers believe that their results confirm the reliability and validity of their clinical driving assessment programs. By using the Elemental Driving Simulator or CBDI, the therapist obtains not only objective data but also recorded information relevant to the driving task. More importantly, data from these tests have demonstrated reliability and validity with published norms and standardized rules. The drawbacks to these tools are that they are expensive, time consuming to give, and require the use of a proper computer, which can be intimidating for an older person.

The predriving clinical evaluation can be organized similar to or along with a typical discharge evaluation of performance skill areas and an ADL and IADL evaluation. The screening would be an obvious emphasis on driving skill requirements in an attempt to determine if the person is ready for referral for the on-road assessment or if the referral should be delayed to a better time. One should remember that if the person is referred too early, the results may produce negative consequences for the person’s driving privileges.

The 2008 OT Practice Framework1 describes performance skills as observable, concrete, goal directed actions that a client uses to engage in daily life occupations. Multiple factors, such as the context in which the occupation is performed, the specific demands of the activity being attempted, and the client’s body functions and structures, affect the client’s ability to demonstrate performance skills. With this in mind, the OT Generalist in Driving should evaluate the stroke survivor’s performance skills for driving with consideration of all of the client factors, contextual/environmental factors, and the activity demands of the occupation of driving for this particular individual.

Discussion of the components of a predriving clinical evaluation at this stage follows.

Motor and praxis skill assessment

The motor and praxis skill assessment should involve a brief functional look at the patient’s active range of motion, muscle strength, sensory modalities, bilateral and unilateral gross and fine motor coordination, and any abnormalities such as muscle tone, spasticity, stereotypical patterns, and associated reactions. A slowing of physical functioning can affect reaction time in responding to stimuli in the environment. Slower reaction time among older drivers may be caused by motor change or delayed visual processing. The loss of strength and range of motion can prevent the person from safely operating the primary or secondary controls of the vehicle. If the person has the necessary isolated control in the affected arm with appropriate sensation and smooth coordination, he or she may be able to continue using this arm for two-handed steering. For liability reasons, the OT Generalist in Driving will not evaluate or recommend adaptive equipment for driving but should be familiar with options available for the stroke survivor, so that the intervention plan may include education of the client and family on the importance of seeing the OT Specialist in Driving. The OT Generalist in Driving should also consider the person’s functional mobility in regards to ambulating to and from a vehicle and loading any assistive devices. Preintervention in this area can save time for the OT Specialist in Driving.

In driving, an affected limb cannot be used at all if the necessary functional skills are not available since it could be unsafe and cause the driver to lose control of the vehicle. An example would be an upper extremity that has a stereotypical flexor pattern with little isolated control. If the patient cannot use the affected arm safely, then various kinds of adaptive equipment and driving aids are available that can be used to aid one-handed steering or for reach of secondary control functions that the impaired extremity should operate. For example, the left hand generally operates the turn signals and the right hand generally operates the gear selector. Fig. 23-7 gives examples of adaptive equipment for driving that is recommended by the OT Specialist in Driving to assist with various vehicle controls. Some states require a spinner knob even if the person can palm the wheel and control it well with the remaining good arm. Compensatory techniques with special equipment can assist only with physically controlling a vehicle and do not resolve the person’s other potential problem area with cognitive and sensory-perceptual skills.

Figure 23-7 Typical driving aids for a person recovering from stroke.

(Courtesy Mobility Products and Design, Winamac, Ind.)

Regarding lower extremity function, if the patient does not have isolated control in the right lower extremity, then the person will require a left foot gas pedal (see Fig. 23-7). If the person has recovery in muscle strength, sensation, and coordination in the right leg, then the patient may be able to continue using this leg normally on the pedals. If the person wears a lightweight short leg brace and has some minimal movement in the ankle, and all other factors—such as strength, sensation, and coordination—are good, then this person still may be able to use the right leg for gas and brake operation or just gas operation. If movement to the brake pedal is slow with or without a brace, or the hip or knee fatigues quickly, then teaching a two-footed driving method may be possible if this is allowed in the state of residence and the person has plantarflexion and dorsiflexion in the affected ankle. Proprioception is necessary and should be evaluated carefully. The OT Specialist in Driving will determine if the stroke survivor has good foot placement, good pedal regulation, and acceptable reaction time using the affected leg. The in-vehicle and on-road evaluation will determine which method and what equipment, if any, is viable and necessary. After the moving assessment, the therapist may determine that the person requires equipment when initially it was thought he or she could use the affected upper or lower limb.

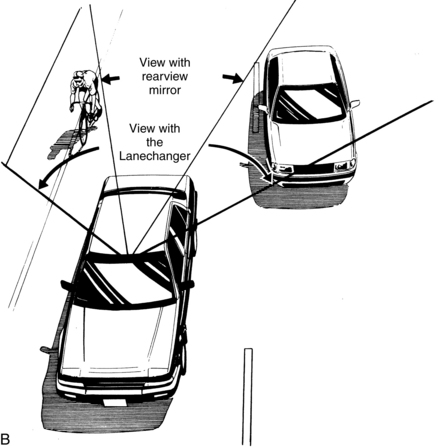

For secondary controls that are operated in a stationary position, the stroke survivor may be able to use compensatory methods for these controls; for example, using the left hand for inserting and turning the ignition key or operating the gearshift lever. If this is difficult, adaptive aids such as a gear selector crossover and key extension may be appropriate. Special panoramic mirrors can be beneficial when neck range of motion is limited or to increase visual awareness to the rear, sides, and blind spots (Figs. 23-8 and 23-9). These mirrors do not compensate for loss of peripheral vision, so they are not useful for correction of homonymous hemianopsia.

Figure 23-8 SmartView Mirror by Interactive Driving Systems. This mirror eliminates the confusion noted in the typical spot convex mirror and increases rear vision by dividing the mirror into two areas. The outside half of the SmartView mirror (white arrow) shows objects in the blind spot of the vehicle, or Danger Zone. If a car is detected in the Danger Zone, the driver must not move in front of it. In this photograph, the car shown is detected by the mirror to be in the driver’s Danger Zone. The upper inside quadrant of the mirror (black arrow) is boxed and shows the Safe Zone. If a car is seen in the box—and stays in the box—the driver may move in front of it.

(Courtesy Interactive Driving Systems, Cheshire, Conn.)

Sensory-perceptual assessment

A visual assessment is crucial because driving depends so much on visual input. A visual assessment in regards to the task of driving is more than mere checking of a patient’s visual acuity and depth perception. Scheiman,32 a rehabilitation optometrist who works with patients with various diagnoses, stated that good vision is more than clear vision: “the individual must have the ability to use his eyes for extended periods of time without discomfort, be able to analyze and interpret the incoming information, and respond to what is being seen.” His experience indicates that nearly half of the patients admitted to a rehabilitation center with stroke or traumatic brain injury have visual system deficits, primarily in the area of binocular vision and accommodation. Other commonly reported vision problems include reduced visual acuity, decreased contrast sensitivity, visual field deficits, visual neglect, strabismus, oculomotor dysfunction, and accommodative and stereopsis dysfunction. See Chapter 16.

The stroke survivor should be evaluated visually according to the vision requirements for licensing of the state. This usually includes visual acuity of 20/40 in at least one eye and a total field of vision of at least 130 to 140 degrees. Eye test charts can be used to ascertain visual acuity. A commercially available stereoscopic vision tester that is self-contained and often used by driver licensing agencies may be applicable to a clinical setting. In addition to visual acuity, these machines also screen for depth perception or stereopsis, contrast sensitivity, road sign recognition, phoria, fusion, and horizontal perimeter vision. These machines have limitations that the therapist must take into consideration when using them and interpreting the results. For example, stereoscopic vision testers rely on binocular vision. If a patient does not possess binocular vision for whatever reason, this machine can be used only on a limited basis. Box 23-4 lists vision testing resources. If any suspicions of problem areas arise, the stroke survivor should be referred to an eye care specialist. If the patient does not meet basic state requirements, an eye care specialist should see the patient before an on-road assessment. For example, if the stroke survivor does not meet the state’s visual requirement for peripheral vision, then he or she and the family should be educated on this fact and never referred to the OT Specialist in Driving. This information should be reported to the state’s medical review board with the Department of Driver Licensing, so the state can make a decision to suspend the person’s driving privileges (see Box 23-4).

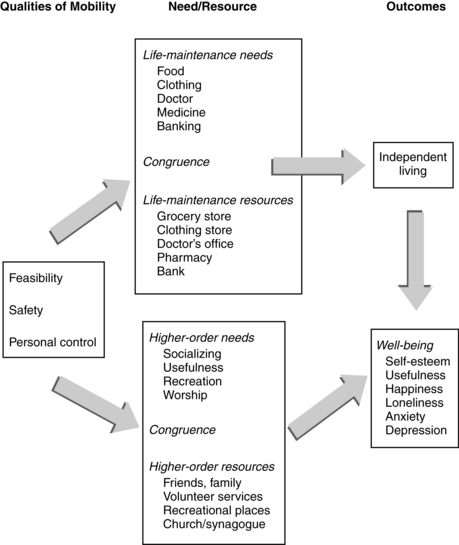

Some states allow a loss of vision in the upper quadrant as long as the lateral median in the superior quadrant is normal (Fig. 23-10). The exact degree of visual field available in each eye should be assessed quantitatively. Gianutsos and Suchoff13 have suggested that perimetric and functional visual fields also are important to assess. A patient with complete homonymous hemianopsia may have only 110 degrees of total visual field. Whenever an occupational therapist suspects that a patient has any degree of peripheral vision loss, an objective test using machines such as the Goldman or Humphrey perimeter test should be used. An OT clinic generally cannot afford expensive, large objective perimeter machines that can quantitatively measure exact degrees of visual fields in all quadrants. The therapist can perform a finger confrontation test or use a horizontal perimeter tool, and while this will confirm a complete hemianopsia, the test is not inclusive or objective. Before concluding that the patient cannot drive with this impairment, the therapist must make a referral to a local eye care specialist that uses one of the machines noted previously to get an accurate report of the exact field of vision.

Aside from visual deficits that may occur because of the stroke, the occupational therapist also must consider the normal change in visual skills occurring due to the person’s age. Testing eye range of motion, tracking, pursuits, and saccades can be done quickly with a few handheld sticks or a tracking ball. As does any organ in the body, the eye loses some of its capability with age. The pupil of the eye becomes less elastic and restricts the amount of light let into the retina. Many elderly patients complain of difficulty driving at night or during weather conditions when the illumination is poor, such as in rain, fog, or snow. Cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration are common among elderly persons. Cataracts, a clouding of the lenses, also can affect night driving and can produce hazy vision during the day. Cataract surgery has a 90% success rate in a healthy older person who does not have comorbidities. Glaucoma, an increase in ocular pressure that damages the optic nerve and retinal nerve fibers, begins by affecting side vision first and eventually compromises central vision. It is a treatable condition, and a referral to the appropriate eye care specialist is important before performing the on-road assessment. The therapist should consider diabetic retinopathy for a person with a history of diabetes. When the degree of macular degeneration is so great that it affects the central vision to a point that the person cannot see anything in this visual area, then the patient needs to stop driving. Therapists can assess visual scanning, awareness, and attention in the clinic by using some of the subtests in the visual-perceptual and cognitive tests discussed later in this chapter.

Because speed and movement can influence visual and visual-perceptual skills, the therapist must make the final determination of the proficiency and effectiveness of these areas for driving in the vehicle and in the dynamic moving traffic environment. For example, the speed of a vehicle decreases visual acuity and side vision. If a person has 200 degrees of visual field, at 20 miles per hour, the field is reduced to 104 degrees; at 40 miles per hour, to 70 degrees; and at 60 miles per hour, to 40 degrees. Speed also decreases visual acuity; the faster the speed, the less time available to react to visual stimuli in the environment.34 The Visual Attention Analyzer Model 2000 (Visual Resources, Chicago, Ill.) assesses the size of the useful field of view and comprises three subtests to evaluate processing speed, divided attention, and selective attention (see Chapter 19). This machine can be helpful to the OT Generalist in Driving as the machine evaluates and provides training modules that can be used in intervention to improve the person’s visual attention and processing speed.

Visual-perception and cognitive assessment

According to Toglia,40 the limitation to the deficit-specific approach to perception is that “it equates difficulty in performance of a specific task with a deficit . . . [and] does not consider the underlying reasons for failure or the conditions that influence performance.” For example, a patient may score low on a typical OT clinical test of visual-perceptual skills; nevertheless, the results may be a consequence of reduced visual acuity or accommodation and not necessarily a specific visual-perceptual deficit.

A stroke survivor who has serious visual-perceptual deficits will have difficulty throughout rehabilitation.43 The occupational therapist will complete documentation and observations of deficits in these areas during routine evaluation and intervention. The stroke survivor should not be referred to the OT Specialist in Driving until the deficit areas no longer interfere with basic ADL. If the therapist understands the definition of each visual-perceptual category and the way deficits in each area affect a person’s basic self-care skills, a further analysis of the activity demands of driving can show the way persistent problems in these areas can interfere with driving performance skills (see Chapter 18 and Chapter 19).

Driving requires a combination of perceptual skills in which cognitive performance plays a major role. Strong cognitive abilities are fundamental to attentiveness in the driving task, recognition of stimuli, and choice of the appropriate way to respond. A decline in cognitive abilities can significantly influence a person’s ability to plan, judge, and act adequately. A cognitively impaired person may have difficulty maneuvering a vehicle through rapidly changing traffic with many unexpected actions and reactions from other drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and bicyclists. Cognitive impairment has been linked to higher motor vehicle crash rates in elderly individuals.6 Problem areas may involve attention, orientation, concentration, learning (short-term memory), and problem-solving. Diffuse cognitive deficits occur more frequently in patients with large frontal strokes, visuospatial deficits in right hemisphere strokes, and apraxia in left hemisphere strokes.46 Unilateral neglect has been reported in half of the patients with right brain damage and in 20% to 25% with left brain damage.38 Diller and Weinberg7 reported that “patients with left hemiparesis often experience accidents that are related to difficulties in dealing with space, while accidents in patients with right hemiparesis are often related to slowness in processing information.”

Patients are generally more aware of motor problems than they are of cognitive problems.13 Gresham and colleagues14 noted that “unawareness of the stroke (or its manifestations) is often found in patients with lesions in the nondominant hemisphere. It can lead to impulsive, unsafe behavior in a patient who may otherwise appear relatively normal with respect to physical functioning.” Patients’ poor insight into their own problem areas can be dangerous because patients may not be aware of serious driver errors and the potentially fatal consequences of their actions.

The occupational therapist can use common verbal and written tasks to assess the areas of visual perceptual functioning such as spatial relations, visual discrimination, form constancy, depth perception and visual memory, sequential memory, and visual closure. Two commonly used tests are the Gardner Test of Visual Perceptual Skills and the Motor-Free Visual Perception Test—3, which is standardized for adults age 70-years-old or older. The Motor-Free Visual Perception Test—Vertical is for those who have difficulty with horizontally presented stimuli such as stroke survivors.

Therapists can use a variety of cognitive tests to assess memory, language, orientation, attention, concentration, reasoning, and problem-solving. The Helm-Estabrooks Cognitive Linguistic Quick Test can be administered in 20 to 30 minutes; is standardized for adults with acquired neurological dysfunction, ages 18- to 89-years-old; and can be used to identify a person’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses. This test gives a “snapshot” assessment of the status of these five cognitive domains: attention, memory, language, executive functions, and visuospatial skills (see Chapters 18 and 19).

During the administration of these clinical tests, one must remember that these tests are static and two-dimensional and do not begin to simulate the dynamics of the driving task. French and Hanson10 stated “controversy continues about which cognitive-perceptual assessments are the best predictors of behind-the-wheel performance.” The authors summarized studies performed by Galski, Bruno, and Elhe in 1992 that found a significant correlation between seven tests: “Part A of the Trailsmaking Test, the Rey-Osterreith Complex Figure Test, the Porteus Maze Test, the Visual Form Discrimination, the Double Letter Cancellation, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised Block Design Test, and Raven’s Progressive Matrices and the behind-the-wheel evaluation . . . . the [continued] research suggests that a combination of neuropsychological testing, visual screening, physical functioning, and actual driving (simulators and on-the-road evaluations) is necessary to predict driving performance.”

Engum and colleagues9 defined basic operational and behavioral skills as “attention, concentration, rapid decision-making, stimulus discrimination/response differentiation, sequencing, visual-motor speed and coordination, visual scanning, and acuity and attention shifting.” Table 23-3 describes several performance areas and the way deficits in these areas can affect driving performance.

Table 23-3 Effects of Various Deficits in a Stroke Survivor on Driving Performance

| TYPE OF DEFICIT | EFFECT ON DRIVING PERFORMANCE |

|---|---|

| Higher cognitive functions, memory, ability to learn | Cannot remember route to take to location or loses way if makes wrong turn; may not remember road names but can remember the route; severe deficits in higher functions may impede safe driving; unless the patient recovering from stroke is a new driver, the inability to learn new tasks may not impede safe driving; may require directions to be repeated |

| Motor | Usually does not impede safe driving because compensatory driving techniques or adaptive driving aids can be used |

| Disturbances in balance and coordination | May impede car transfers or loading of mobility device (e.g., wheelchair or walker); steering device, left-foot accelerator, or turn signal adaptation may compensate for inability to use the upper or lower extremity |

| Somatosensory | Generally does not interfere with driving because a person does not use an extremity with lack of sensation or with limiting pain while driving |

| Vision disorders | Severe visual loss or ocular motility disturbances may impede safe driving; the deficit may lead to the patient not meeting driver licensing requirements; persons with homonymous hemianopsia are not allowed to drive in most states; other age-related deficits such as glaucoma, cataracts, and diabetic retinopathy may impede safe driving. |

| Unilateral neglect | A contraindication for safe driving |

| Speech and language | Expressive aphasia, dysarthria, or apraxias of speech are usually not problems in driving, although attempting to carry on a conversation while driving may cause distraction; receptive aphasia may impede the driver from understanding directions or conversation. |

| Pain | The unaffected extremities may be used to drive; does not impede driving unless it is so severe it causes a distraction. |

An appropriate end to the predrive clinical evaluation may involve several tests to assess procedural memory for driving, knowledge of road rules, and road sign and/or situational problem-solving, reasoning, and judgment. Several formal tests can be used. The Driver Performance Test, distributed by the Advanced Driving Skills Institute (Orlando, Fla.), is a video of simulated real-world driving scenes and provides insight into the patient’s perceptual capabilities, psychomotor responses, and decision-making strategies. Using a driver education defensive driving technique of identifying, predicting, deciding, and executing, the Driver Performance Test requires the patient to search for hazardous situations or conditions, identify potential and immediate hazards, predict the effect of the hazard, decide the way to evade the hazard, and execute evasive driving actions.44 The drawback to this test is that it takes about 45 minutes to administer. Additional time is then necessary to review the answer video with the patient, an essential step for any learning or understanding to take place for the patient or the therapist.

Because the Driver Performance Test has no statistical validity, the therapist should decide whether to use valuable time administering it during this phase or letting the driver rehabilitation therapist use it in the next phase of the process. An important consideration is that this rapidly timed test may produce stress in the stroke survivor because it requires quick problem-solving and decision-making, marking on an answer sheet while having attention divided, and retaining information. The test taker has only a few seconds to choose an answer and then must go on to the next traffic scene because the test has no built-in delay or pause. If the test taker gets behind, he or she may become disorganized or distracted and not be able to respond to the next scene. Although quick thinking and reaction are important for driving, the Driver Performance Test may be a better tool to use after the patient has passed all clinical tests and road tests, and may be a more effective tool to use when the therapist determines that the patient needs more practice, training, or review in the areas tested by the Driver Performance Test (Box 23-5).

Importance of the combination of a clinical evaluation and an on-road evaluation

A comprehensive driver evaluation should involve the two phases of a clinical evaluation and an on-road evaluation. A therapist’s decision regarding the patient’s motor, sensory-perceptual, and cognitive abilities for driving should not be based solely on a clinical test(s) or solely on an on-road test. In a 1994 review of driver assessment methods at the Jewish Rehabilitation Center in Montreal, Canada, the chief of research and her associates found that 95% of their patients were given on-road tests because no clear cutoff score based on typical clinical tests was reliable in predicting whether a person was unsafe to drive.21 Earlier studies suggested that persons who pass tests for cognitive deficits do not require road tests.25,33 Experienced certified driver rehabilitation specialists (CDRS) typically do not agree with this opinion, and other more recent studies have found that clinical testing alone is insufficient and recommend a mandatory driving test.4,20,42

A therapist should not deny a stroke survivor the opportunity to have the road test based on the clinical findings only unless the patient has obvious serious performance skill issues or does not meet the basic requirements given by the department of driver licensing. The therapist at this point can make only an assumption regarding significant deficits and the potential for them to interfere with driving performance. There is little correlation between typical clinical tests and real driving performance, so the therapist performing the formal driving test on the road should make the conclusion regarding the stroke survivor’s driving abilities. Occupational therapists who are experienced driver rehabilitation therapists say that some patients who do well on clinical tests perform poorly in the car. However, they agree that some patients who do poorly in the clinic perform well in the familiar environment of the car. Again, the decision lies in the occupational therapist’s skill to combine clinical observations and analysis with clinical reasoning and judgment of in-car performance.

Determination of readiness for the road test

Driving is one of the most complex activities a person may perform, requires integration of many performance areas, and should always be at the top of the ADL pyramid. Because of its complexity, driving should be one of the last ADL attempted following a stroke.28 The stroke survivor must have reached all other ADL goals before being ready for the difficult ADL of driving. With abbreviated inpatient rehabilitation stays for stroke survivors becoming the norm, the driving evaluation should not take place until the patient has been discharged from the outpatient treatment program or has recovered to a maximal level of independence in the performance of other ADL. If the person is referred too early, he or she may not do well and may lose driving privileges. If the person is referred too late, then he or she may begin driving without an evaluation or the necessary medical approval and put other persons at risk.

Timeliness of the referral for the formal road test is important. Typically, the appropriate time for a referral to the driver rehabilitation therapist is not until two to four months after discharge from the inpatient facility. An exception to this timeline is if the person suffered a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and recovered quickly with minimal residual deficits. This person may be evaluated as early as two to four weeks after discharge from the inpatient facility. The clinical occupational therapist is the best person to determine whether the stroke survivor is ready for the formal road test before discharge as an inpatient or to determine an estimation of time for readiness after discharge to include in the team’s discharge planning and final recommendations to the patient and family. Input from all team members should be sought. The physician should provide only medical clearance when all parties agree that the stroke survivor is ready for the on-road evaluation.

A timely referral by the physician or other team members may reduce the likelihood that the patient may begin driving with no supervision from a family member or friend. The physician should communicate effectively to the stroke survivor that he or she should abstain from all driving until an evaluation has been completed. This recommendation should be documented and verbally communicated to the person’s caregivers. For liability protection of the rehabilitation facility and team members, the patient should be required to sign a form demonstrating understanding of the recommendations given and indicating willingness to comply. Each team member that has verbally given the same recommendations to the patient should document in the progress notes or discharge summary when and what instructions were given to the patient. If it appears that the person will not comply with the recommendations, the rehabilitation team (doctor or therapists) should advise the department of driver licensing.

The therapist should caution the patient and the family against practicing a week or so before the appointment with the driver rehabilitation therapist. This strategy is unsafe and needless and puts the patient at risk to be sued by parties for driving while impaired, which can cause personal and property damage. In addition, insurance companies may be able to claim fraud and violation of their regulations, so that they are not monetarily responsible for any damages ordered by a court. The potential consequences are not worth the risk and associated liability, and family members should be informed.

Occupational therapist as a specialist in driving or driver rehabilitation therapist

The impact of persisting sensory, perceptual, motor, and cognitive deficits on driving risk levels must be addressed through an objective, formal evaluation on the road and in a specially adapted evaluation vehicle. The professional performing this part of the driving evaluation must have a medical background, knowledge of driver education principles, and special training and skill in in-vehicle techniques and methods. The allied health professional in this role is called the driver rehabilitation therapist to distinguish the therapist from a commercial driving school instructor.

According to the 2009 membership directory of the Association of Driver Rehabilitation Specialists, most therapists certified by this organization have an OT background. Since 2005 the AOTA created an Older Driver Initiative to coordinate multiple projects related to increasing the occupational therapist’s awareness and professional training in addressing the occupation of driving and community mobility. The projects completed as of 2009 include an evidence-based literature review, publication of OT Practice Guidelines for Driving and Community Mobility for Older Adults (2006), Older Driver Microsite (www.aota.org/olderdriver), and a specialty certification in driver rehabilitation and community mobility. AOTA also has a variety of educational opportunities available at their annual conference or at their website for continuing education. The AOTA offers a professional certification designation (specialty certification in driving and community mobility [SCDCM] or driving and community mobility assistants [SCADCM]) through a portfolio and professional development process that is available for application year round. Adaptive Mobility Services, based in Orlando, Florida, has offered since 1984 educational workshops for the allied health professional who need advanced knowledge and skill in the field of driver evaluation as a OT Generalist in Driving or an OT Specialist is Driving. It now offers in-person and online CE opportunities. Box 23-6 has contact information on these organizations.

Box 23-6 Resources for Professional Education, Driver Education Materials, and Networking

Adaptive Mobility Services (AMS)

Department of Continuing Education

American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA)

Association of Driver Rehabilitation Specialists (ADED; formerly called Association of Driver Educators for the Disabled)