chapter 28 Activities of daily living adaptations: managing the environment with one-handed techniques

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

1. Explore a variety of adaptive techniques and assistive devices to allow for completion of activities of daily living.

2. Enhance performance of activities of daily living using principles of energy conservation and work simplification.

3. Explore environmental modifications to enhance safety and ease of mobility in the performance of activities of daily living.

Occupational therapy intervention for stroke survivors is geared toward ameliorating deficits resulting from stroke and varies tremendously from one patient to another. For certain individuals, limited return of functional use of the involved extremity makes performance of self-care and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) uniquely challenging. According to the study described in “Compensation in Recovery of Upper Extremity Function After Stroke,”1a the emphasis of intervention during rehabilitation for patients with extensive upper extremity paralysis should be on teaching one-handed compensatory techniques. The occupational therapist is called to use creative problem-solving abilities to enhance independence in a wide range of activities, helping the patient achieve meaningful, realistic goals. Indeed recent evidence strongly suggests that focused occupational therapy makes a substantial impact in this area of activities limitations (Box 28-1). (See Chapter 21 for a comprehensive overview of IADL.)

Box 28-1 Evidence Briefs: ADL Retraining after Stroke

A recent systematic review and metaanalysis aimed to determine whether occupational therapy focused specifically on personal ADL improves recovery for patients after stroke. Nine randomized controlled trials including 1258 participants met the inclusion criteria. The authors concluded, “Occupational therapy focused on improving personal activities of daily living after stroke can improve performance and reduce the risk of deterioration in these abilities. Focused occupational therapy should be available to everyone who has had a stroke.” (Legg, et al, 2007)

A recent systematic review and metaanalysis aimed to determine whether occupational therapy focused specifically on personal ADL improves recovery for patients after stroke. Nine randomized controlled trials including 1258 participants met the inclusion criteria. The authors concluded, “Occupational therapy focused on improving personal activities of daily living after stroke can improve performance and reduce the risk of deterioration in these abilities. Focused occupational therapy should be available to everyone who has had a stroke.” (Legg, et al, 2007)

Steultjens and colleagues conducted a systematic review to determine from the available literature whether occupational therapy interventions improve outcomes for stroke patients. The authors identified and included 32 studies (18 were randomized controlled trials). They documented significant effect sizes for the efficacy of comprehensive occupational therapy on primary ADL, extended ADL, and social participation.

Steultjens and colleagues conducted a systematic review to determine from the available literature whether occupational therapy interventions improve outcomes for stroke patients. The authors identified and included 32 studies (18 were randomized controlled trials). They documented significant effect sizes for the efficacy of comprehensive occupational therapy on primary ADL, extended ADL, and social participation.

Trombly and Ma examined 15 studies involving 895 participants (mean age = 70.3-years-old). Of these studies, 11 (7 randomized controlled trials) “found that role participation and instrumental and basic activities of daily living performance improved significantly more with training than with the control conditions.” The authors concluded that “occupational therapy effectively improves participation and activity after stroke and recommend that therapists use structured instruction in specific, client-identified activities, appropriate adaptations to enable performance, practice within a familiar context, and feedback to improve client performance.”

Trombly and Ma examined 15 studies involving 895 participants (mean age = 70.3-years-old). Of these studies, 11 (7 randomized controlled trials) “found that role participation and instrumental and basic activities of daily living performance improved significantly more with training than with the control conditions.” The authors concluded that “occupational therapy effectively improves participation and activity after stroke and recommend that therapists use structured instruction in specific, client-identified activities, appropriate adaptations to enable performance, practice within a familiar context, and feedback to improve client performance.”

Basic environmental considerations

Before initiating basic activity of daily living (BADL) training, the therapist should address the variety of environments in which the patient is required to perform. While surveying the patient’s environment, the therapist should consider the following criteria:

Safety

Helping patients negotiate the bedroom environment safely is a priority because this is an area in which many self-care activities are performed. The height of the bed should allow the patient to sit comfortably with both feet flat on the floor to provide a good base of support. If the bed is too high or too low, the therapist can consider the following adaptations. Several inches can be sawed off or added to the bedposts of a wooden bed to adjust the bed height. Leg extensions are commercially available from a variety of rehabilitation catalogs. Another alternative is to remove the bed frame entirely and use only the box spring and mattress. Ideally, a double mattress should be used to improve ease of mobility and provide an increased sense of security. The mattress should be firm to allow for increased postural stability and improved balance. The bed should be placed within the room to allow access from both sides. Use of a transfer handle positioned on the patient’s noninvolved side improves safety and ease of mobility in and out of the bed (Fig. 28-1).

Bedroom furniture should be rearranged to eliminate obstacles hindering the patient from negotiating a path to the bathroom or room exit. If possible, changes in the floor surface should be avoided. Bare floor surface changing to raised carpeting, for example, may increase the risk of falls.

The sensory environment is another component to consider. Factors such as sufficient lighting and a comfortable room temperature must be ensured. If inadequate, both conditions present safety obstacles. For example, if the room temperature is too cold, the patient may experience an increase in muscle activity, possibly decreasing postural stability and the ability to perform self-care tasks successfully. (See Chapter 27 for a detailed review of home modifications.)

Ease of mobility and performance of activities of daily living

In addition to the safety of the environment, the therapist also must consider arrangement of the bedroom to increase ease of mobility and performance of ADL. The therapist may use energy conservation and work simplification techniques to teach the patient ways to prioritize, organize, and limit work to save time and energy and to enhance the successful outcome of task performance. The following techniques should be considered:

1. Eliminate excess space. Enough space must be available for ease of mobility without excess. Excess space forces a patient to travel greater distances, draining personal energy resources. For example, the bathroom ideally should be directly off the bedroom rather than down the hall. If this arrangement is not possible, a bedside commode and sitting table with a mirror that can be set up to allow for performance of toileting and grooming are useful modifications. A living room can be used to replace an out-of-the-way bedroom.

2. Arrange the room so that sequential tasks can be performed with minimal travel time in between.

3. Place appliances and controls where they can be accessed easily. Lamps, alarm clocks, and telephones should be placed where they are needed most often and are most convenient for the patient. The use of environmental control units should be considered.

4. Eliminate clutter. Thorough cleaning and organization is essential to allow for easy retrieval of commonly needed items.

5. Arrange for easy access of clothing and toileting supplies by eliminating excess reaching and bending. Shelves are easier to access than drawers are. If drawers are used, they are easier to open with a central knob rather than handles. Also, closet rods can be lowered to eliminate excess reaching. An alternative solution includes use of a reacher.

Therapists must be aware of the neurobehavioral deficits that affect BADL and IADL. These deficits influence equipment choices and training techniques (see Chapters 17 and 18).

Functional assessment

The World Health Organization’s 2001 International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health4 provides a useful conceptual framework while considering using functional assessment instruments in stroke rehabilitation. Many instruments have been used in research and clinical practice to assess functional outcomes in patients who have survived a stroke (Table 28-1). See Chapter 21 for a review of standardized tools to assess IADL.

Table 28-1 Examples of Functional Assessments for Stroke Survivors

| INSTRUMENT | BRIEF DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| American Heart Association Stroke Outcome Classification (Kelly-Hayes and colleagues, 1998) | The purpose of this instrument is to serve as a standardized and comprehensive classification system to document the impairments and disability resulting from a stroke. The scale considers the number of neurological domains involved, severity of impairment, and level of function. |

| A-ONE (Arnadottir, this volume) | Documents level of functional independence in basic ADL and mobility and underlying neurobehavioral impairments. See Chapter 18. |

| Barthel ADL Index (Mahoney, 1965) | Scores for activities are weighted so that the final item scores range from 0 for dependent performance to 15 for independent performance. Total score ranges from 0 to 100. Activities include feeding, bathing, grooming, transfers, dressing, bowel, bladder, toileting, walking, wheelchair use, and stair climbing. |

| Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Law and colleagues, 2005) | Measures clients’ perceptions about performance and satisfaction with self-care, productivity, and leisure. After identifying occupational performance issues, the clients rate their perception of performance and satisfaction with performance on a 1 to 10 scale. The same scale is used for reassessment. |

| Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (Keith and colleagues, 1987) | Administered by members of the rehabilitation team by direct observation. A detailed scoring system is used, and therapists are trained to administer the FIM in a standardized manner. Items scored on a 1 to 7 scale include self-care, sphincter control, mobility, locomotion, communication, social skill, and cognition. |

| Modified Rankin Scale (van Swieten and colleagues, 1988) | A 5 point scale used to rate disability and need for assistance. |

Basic activities of daily living

Grooming and hygiene

When performing hygiene and grooming, assistive devices and alternative methods often provide increased independence and safety and decreased energy expenditure.

Toileting.

A toilet tissue dispenser should be mounted within easy reach of the unaffected side and allow for easy, one-handed retrieval of tissue sheets. Two possibilities include a tissue box dispenser mounted on the bathroom wall or an easy-load toilet paper holder, which eliminates excessive paper roll waste. This alternative gives a more aesthetic appearance, possibly improving acceptance by the patient (Fig. 28-2). Moist towelettes can be used in place of toilet paper and are a viable alternative for patients with urgency or impaired sphincter control.

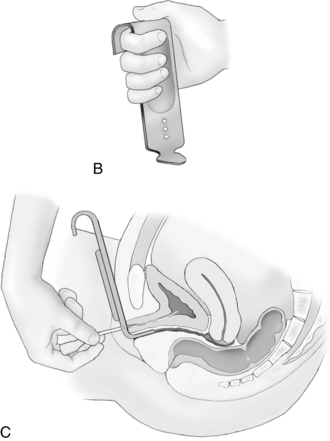

Two devices that are available and recommended to increase independence in bladder care for women who have survived a stroke include the Asta-Cath and the Feminal. Both products are available from A+ Products. The Asta-Cath female catheter guide is a simple device that assists women in locating their urinary meatus. As the Asta-Cath is inserted into the vagina, it spreads the labia, and one hole aligns with the urinary meatus. The patient then can pass a No. 14 French or smaller catheter into the bladder for emptying. The three alignment holes allow for most anatomical differences (Fig. 28-3). The Feminal is designed so that a woman can urinate in a reclined, seated, or standing position. When gently pressed against the body, the unique shape creates a leak-proof seal (Fig. 28-4).

Showering and bathing.

Transferring from a slippery tub, controlling water temperature, and washing adequately in a slippery tub are safety factors to consider during bathing. Nonslip mats should be placed inside and outside the tub. All toiletries should be placed where they can be reached easily. Articles should be moved close together if the individual is sitting on a tub bench to ensure safe reaching. To ensure safety of water temperature and ease of bathing, a handheld shower hose with control of water flow may be used to prevent scalding. This device can be purchased through a variety of catalogs.

Long-handled scrub sponges and bath brushes are excellent assistive devices for washing. A flex sponge is able to bend in any direction to wash all of the body, including the nonaffected arm, axilla, and shoulder, which may be difficult to reach (Fig. 28-5). Soap on a rope or a suction soap holder may be used to prevent soap from slipping about or getting lost in the water. The soap on the rope is hung around the neck or hung within easy reach. Another alternative is to use liquid soap in a pump container. A soaper sponge also may be used to wash without having to hold a slippery bar of soap. If grasp is limited, the patient can use a terry cloth wash mitt with a pocket to hold the bar of soap. The aforementioned devices may be purchased through a variety of rehabilitation catalogs. For those who must rely on another to bathe them, a mechanical lift positions the person in a body sling. This lifting device has a swing arm to allow a person to be suspended in a shower or over a tub.

Shampooing.

Shampoo in a pump spray bottle helps avoid waste and reaches a broader area of the scalp. A full-spray handheld shower is convenient for rinsing.

Drying.

To decrease energy expenditure while drying, an extra large towel or terry wraparound robe can be worn to absorb most of the water. The back and nonaffected arm are the most difficult areas to dry. The following procedure can be incorporated:

1. Place the towel over one shoulder.

2. Reach behind and grasp the other end, pulling the towel down across the back.

An alternative method is to toss the towel over the top of a doorway and shut the door as much as possible to hold the towel in place. The patient then can pull the towel across the back and shoulder with the nonaffected extremity.

Washing at the sink.

Some individuals may have difficulty showering or bathing for a variety of reasons. An alternative method is to have body washes at the sink. The easiest position in which to wash the affected arm is to place the arm and axilla in the sink basin. To wash the unaffected arm, the individual steadies the soapy washcloth over the edge of the sink and rubs the arm and hand over it. The patient then washes the rest of the body with one hand. Again, a flex sponge is useful to wash all of the body, including the nonaffected extremity. A supplement to washing at the sink is the use of a bidet. The Hygenique Plus Bidet/Sitz Bath System is designed specifically for personal hygiene needs. This system combines a spray wand for bidet cleansing and a sitz bath (Fig. 28-6).

For individuals with low endurance who are unable to shower or bathe at the sink, a total-body, pH-balanced cleanser may be used for shampooing, bathing, and incontinence care. This product is available through a variety of rehabilitation catalogs. Drying techniques are the same as previously described.

Performing oral hygiene.

Oral hygiene care can be done easily with one hand. A toothpaste dispenser can dispense the correct amount of toothpaste on the brush for individuals with limited hand function (Fig. 28-7). The method of brushing (electrical or manual) is a personal choice. The use of an electrical toothbrush may decrease energy expenditure because the brush vibrates up and down, and the patient holds the arm in one position. A Waterpik attachment is excellent for massaging the gums and rinsing between the teeth. Suction toothbrushes may be attached to a suction unit to prevent dysphagia-related aspiration in individuals who cannot tolerate thin liquids.

The simplest method for denture care is to soak the dentures overnight in a commercial denture cleanser. If additional cleansing of dentures is needed, the patient can use a suction denture brush.

Flossing teeth with one hand can be performed easily and effectively with a commercially available dental floss holder.

Applying deodorant.

Aerosol sprays are easier to apply to the unaffected arm unless the individual has sufficient function to reach the axilla with a roll-on or stick applicator. The affected axilla must be placed passively away from the body to apply deodorant. This can be accomplished by bending forward at the hips and allowing gravity to assist the arm away from the body.

Caring for fingernails.

Nail care of the affected hand can be done easily with the noninvolved hand. Cleaning, cutting, and filing the nails of the unaffected hand are more difficult.

The following strategies may be used to ease nail management:

1. To clean the unaffected hand, a nailbrush with suction cups for cleaning fingernails can be used.

2. To cut the nails of the unaffected hand, the patient may use a one-hand fingernail clipper. When the patient presses down on the board, the jaws of the clipper close (Fig. 28-8).

3. Filing the nails of the unaffected hand can be done in a variety of ways. A suction emery board is useful. Other individuals may choose to use a homemade device such as an emery board or sandpaper glued to a piece of wood, a nail file secured to a table with masking tape, or a file wedged in a drawer.

4. Applying nail polish to the unaffected hand can be done by mounting a clothespin on a piece of wood with a C-clamp to hold the polish brush. The polish is applied when the person moves the nail in relation to the brush.

Caring for toenails.

Cleansing toes can be accomplished with the use of a footbrush or Footmate System (Fig. 28-9). Clipping toenails is easier if the feet are soaked in warm water first. A pistol-grip remote toenail clipper is one of several devices designed for one-handed use to clip toenails; it allows one to reach the foot with less bending (Fig. 28-10).

Hairstyling.

Simple, short hairstyles are the easiest to manage with one hand. Combing or styling long hair may be easier using adjustable, long-handled grooming accessories, available through various rehabilitation catalogs. Lightweight splinting material also may be used to extend the handles of an individual’s favorite grooming tools.

Blow-drying hair can be made easier by using a commercial product called the Hands-Free Hair Dryer Holder, which allows the unaffected hand free operation to style hair (Fig. 28-11). An alternative method is a home-devised product such as a position-adjustable hair dryer. A lightweight blow-dryer, a desk lamp with spring-balanced arms, a tension control knob at each joint, and a mounting bracket are the only materials needed to fabricate the device. The position-adjustable hair dryer requires limited body movement because the dryer can be positioned in any plane desired.1

Brush attachments to the hair dryer also can be used for blow-drying styles. A hot brush curling system can be used for setting hair in simple hairstyles.

Dressing

Retraining an individual with hemiplegia who is limited to the use of one hand to dress presents challenges to the patient and the therapist. Specific deficits that the therapist must address include the following:

1. Impaired postural stability and balance

2. Decreased dexterity and work speed

3. Impaired ability to stabilize clothing articles and body parts

4. Decreased endurance accompanied by increased energy demands on the body

When retraining the patient in dressing techniques, the therapist should incorporate adequate time and allowances for rest breaks into the session. The patient should be able to achieve success without undue effort. Loose-fitting clothes should be selected. Roomy clothes with limited fasteners allow for increased ease of movement and easier donning and doffing.

Dressing and undressing invariably involve awkward movement patterns and a certain amount of sitting down and standing up. Care must be taken to ensure that the danger of falling is minimized. Management of clothes is always difficult at first; the occupational therapist should reinforce to the individual that independence and efficiency are achieved through practice.

Fasteners

Many individuals with hemiplegia can learn to manage fasteners if the following requirements are met:

Buttons and hooks are of a larger size.

Buttons and hooks are of a larger size.

Fasteners are positioned in front of or on the nonaffected side of the garment and are within sight.

Fasteners are positioned in front of or on the nonaffected side of the garment and are within sight.

Buttons.

If the patient is unable to manage fasteners, the therapist can use the following adaptation:

1. Remove the buttons from the garment and then sew them back on over the buttonholes.

2. Using Velcro squares, sew the loop side of the Velcro over the original button side of the garment.

The patient then simply uses hand pressure to close the garment. A standard collar extender also can be used. With this item, collars and cuffs are increased by ½ inch, increasing ease of management.

Zippers.

Zippers may be easier to manage if a ring or loop is added to the zipper tab. Patients should avoid open-ended zips. Patients can leave the zip fastened at the bottom and don the garment by pulling it on over the head. A large safety pin left fastened can prevent the zipper from sliding all the way down and detaching during overhead donning.

Adaptive dressing techniques.

Before initiating dressing training, the therapist should ensure the patient is seated on a stable, supportive surface, preferably a sturdy armchair. Both of the patient’s feet should be securely positioned on the floor to establish a solid base of support and increase postural stability. Clothing should be placed within easy reach and in the order in which each item is required. This helps maximize energy preservation.

A wide variety of dressing techniques are described in the literature, depending on the particular treatment theory incorporated by the therapist. Some general principles that facilitate ease of one-handed dressing are described in the following sections.

Upper extremity dressing

Donning garments with front fasteners.

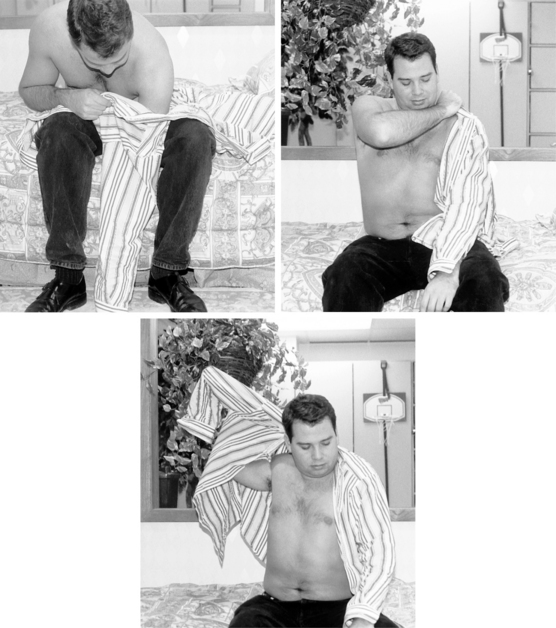

The patient should follow these instructions for donning garments with front fasteners (Fig. 28-12):

1. Pull the shirtsleeve onto the affected arm.

2. Pull the shirtsleeve over the affected shoulder.

3. Swing the garment around until the other sleeve hangs down the back or pull the sleeve over the head and around the neck. The patient may even anchor it by biting the sleeve.

4. Reach to the back with the nonaffected arm and place it into the opening of the remaining sleeve.

5. Use a shrugging motion with the nonaffected arm, and straighten the sleeve into place.

Shirtsleeves may need to be expanded or loose fitting to be pulled over the noninvolved hand. This can be achieved by sewing a piece of elastic into the sleeve cuff to allow for easy passage over the hand2 and to eliminate the difficulty of managing a cuff button.

The top button of a shirt collar is often difficult to fasten. The button is usually small, and the collar fits snugly around the neck. The problem can be eliminated by replacing the button with a Velcro fastener.2

Donning ties.

Ties are difficult to manipulate single-handedly. The simplest solution is to use a conventional, already-tied tie. A piece of elastic may be inserted into the back of the tie to replace a small part of the fabric. This allows for easy passage of the tie over the head. Clip-on ties also are convenient to use.

Donning pullover shirts

The patient should follow these instructions for donning pullover shirts:

1. Use shirt tags or labels to identify the front and back sides of the garment.

2. Pull the correct sleeve onto the affected arm, and pull the garment onto the affected shoulder.

3. Bend the head forward through the neck opening.

4. Put the unaffected arm into the other sleeve.

5. Straighten the sleeve by rubbing the arm against the leg.

Donning brassieres.

Front-fastening bras are easier to manage than bras that fasten in back. The bra should be donned by putting the affected arm in first. Another method is to fasten the bra first and then put the bra on by donning it over the head. Larger hooks can be substituted for smaller hooks, or a Velcro strap and D ring may be sewn in as substitutions for the fastener. A bra extender can be purchased and interchanged between bras; increasing the girth accommodation can ease donning.

Patients may manage back-closure bras in the following way:2

1. Align the bra around the waist so that the cups face backward. The strap can be held in place by hugging it with the affected arm, by tucking it into the elasticized panty waist, or by using a clothespin to hold it onto the pants.

3. Swivel the bra around so that the cups are in front.

4. Pull the strap over the affected shoulder.

5. Using the thumb of the unaffected hand, pull the strap over the unaffected shoulder.

The easiest solution, although not necessarily the most aesthetic, is a fully elasticized bra such as a sports bra, which can be slipped on over the head. A hook-and-eye bra can be adapted by sewing the back fasteners together.

Lower extremity dressing

Donning pants and underwear while lying in bed

The patient should follow this procedure for donning underwear and pants in bed:

1. Bend the affected leg until the foot is within reach. The patient may use the unaffected leg to assist with this.

2. Place the pants over the affected foot and allow the leg to straighten into the pant leg.

3. Put the unaffected leg into the pants and pull the pants up as far as possible.

4. Using the unaffected leg, or if possible both legs, lift the pelvis off the bed. Wriggle the pants up to the waist.

5. Fasten the pants. (Velcro may be used in place of buttons.)

Donning pants and underwear while sitting up

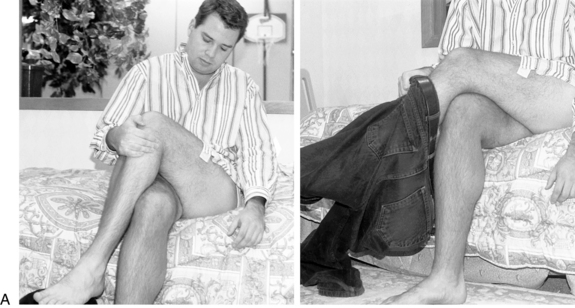

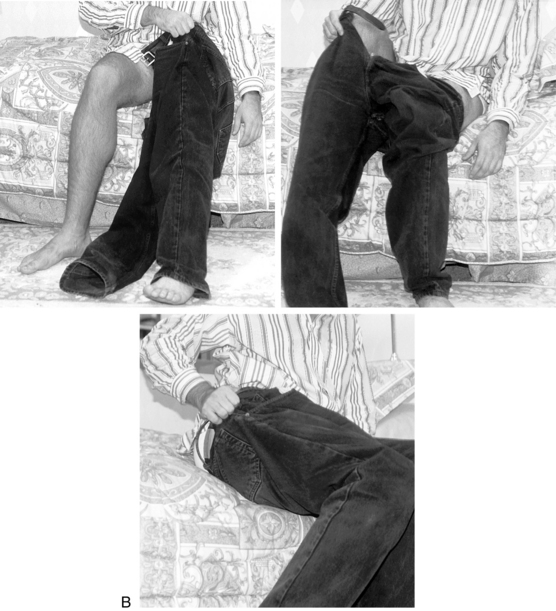

The patient should follow this procedure for donning underwear and pants while sitting up (Fig. 28-13):

1. While sitting (preferably on a firm surface), cross the affected leg over the unaffected leg. Use clasped hands to lift the leg.

2. Put the correct pant leg over the affected foot and pull it onto the leg.

4. Pull the pants up as far as possible while sitting; shift weight over each buttock.

5. Stand up to pull the pants up around the waist. If balance is impaired, lean against a wall or sturdy piece of furniture to provide support and minimize the risk of falling. The patient also can use a pant clip. The pant clip attaches to the pants and an upper body garment, and the clip holds the pants up while the patient transitions to standing, thereby improving safety and function.

Donning skirts

The patient should follow this procedure for donning skirts:

1. Put the skirt over the head and then pull it down.

2. Make sure to maneuver the fasteners to the front or the unaffected side for increased ease of fastening.

A skirt with an elasticized waist that expands to pass over the head may be simpler.

Donning socks

The patient should follow this procedure for donning socks (Fig. 28-14):

1. Cross the affected leg over the other leg, using clasped hands to lift the leg.

2. With the leg in place, open the sock using the thumb and index finger of the unaffected hand. Roll the sock down to the heel before slipping it on for greater ease in donning.

3. Bend forward at the hips to assist in reaching the foot. Pull the sock over the foot.

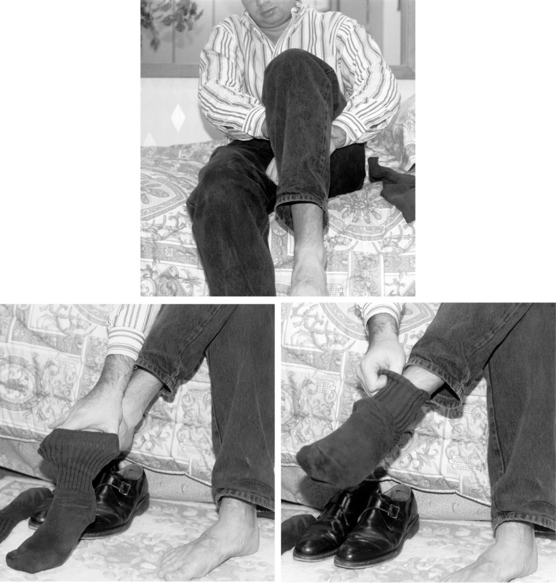

Donning shoes

The patient should follow this procedure for donning shoes (Fig. 28-15):

1. Choose shoes that provide good support. A broad heel can provide better stability if balance is poor. Men’s standard dress shoes have a toe spring built into the front. For a patient recovering from stroke, the toe spring may assist with toe clearance during the swing phase of gait.

2. Bring the affected foot closer to the body by crossing it over the unaffected leg or by using a small footstool.

3. With the leg in place, open the shoe as much as possible before attempting to put it on.

4. Bend forward at the hips to reach the foot. Place the shoe over the ball of the foot and pull it on. A helpful technique to aid with getting the shoe over the foot is to mold a small piece of splinting material onto the shoe heel and allow it to harden. This helps to keep the heel rigid, preventing it from buckling under as the foot slides in.

5. Shoes with Velcro closures are easy to manage with one hand. Shoelaces can be substituted with elastic laces or coilers that do not require tying.

Donning lower extremity orthotics.

Lower extremity orthotics can be difficult for patients to manage one-handed, and patients may require assistance. In general, the donning of orthotics is easier if placed into the shoe first. An adaptation to the pant leg that may be helpful in donning the orthotic is to open the inseam of the pant cuff to the desired length. Stitch the loop side of a Velcro strip underneath the top of the seam and the hook side to the front of the seam. The pant leg then can be opened up, allowing for easier manipulation of the orthotic over the calf.

Adaptive devices

The therapist should introduce adaptive dressing devices only if the patient cannot otherwise perform dressing safely or efficiently. Dressing devices to consider might include the following:

A reacher, particularly if a patient has poor trunk control

A reacher, particularly if a patient has poor trunk control

A dressing stick, which can be useful to extend reach if trunk balance is impaired and to push garments off the affected side

A dressing stick, which can be useful to extend reach if trunk balance is impaired and to push garments off the affected side

A long-handled shoehorn, which may assist the patient in slipping on shoes

A long-handled shoehorn, which may assist the patient in slipping on shoes

All of the aforementioned devices are available from a variety of rehabilitation catalogs.

Walker, Drummond, and Lincoln3 completed a randomized crossover study. One group (n = 15) received three months of no intervention followed by three months of treatment; the other group (n = 15) received three months of treatment followed by three months of no treatment. Treatment was provided by an occupational therapist and focused on dressing training for the subjects and their families. The subjects were assessed by an independent evaluator using the Nottingham Stroke Dressing Assessment; the Rivermead ADL Assessment, self-care section; and the Nottingham Health Profile. Both groups showed statistically improved performance during the treatment phase, neither group showed a change during the nontreatment phase, and subjects who received treatment in the first three months maintained their improvement.

Feeding techniques

Positioning at the table.

The affected extremity should be supported in a good weight-bearing position on the table. This position promotes appropriate upper extremity alignment, visual awareness of the extremity, and trunk symmetry.

Use of adaptive devices.

To avoid embarrassment while dining with others and to reach full independence with feeding, the patient often uses compensatory strategies and adaptive equipment. The following equipment is recommended:

Nonskid mats should be used to prevent slippage of plates and bowls and to hold them steady during meals.

Nonskid mats should be used to prevent slippage of plates and bowls and to hold them steady during meals.

Plate guards and scoop dishes are recommended to eliminate food getting pushed off the plate while scooping or when buttering bread.

Plate guards and scoop dishes are recommended to eliminate food getting pushed off the plate while scooping or when buttering bread.

A rocker knife or knife with serrated and curved edges is easy to use with one hand if safety awareness is intact.

A rocker knife or knife with serrated and curved edges is easy to use with one hand if safety awareness is intact.

Combined implements such as knife and fork or knife, fork, and spoon are available for purchase. Safety in using these combined instruments is a concern if loss of sensation or weakness in oral-motor structures is present. Utensils with built-up handles also may be used to assist a weak grasp.

Combined implements such as knife and fork or knife, fork, and spoon are available for purchase. Safety in using these combined instruments is a concern if loss of sensation or weakness in oral-motor structures is present. Utensils with built-up handles also may be used to assist a weak grasp.

Instrumental activities of daily living

Kitchen activities

An individual with hemiplegia can accomplish kitchen tasks safely with adequate activity pacing; properly placed, secured equipment; and provision of adaptive devices.

Energy conservation and work simplification.

A consequence of weakness and impaired upper extremity function is that the individual with hemiplegia tires more quickly and thus needs to work at a slower pace. The following energy conservation guidelines should be included in treatment plans focusing on increasing IADL:

Allow increased time for task completion.

Allow increased time for task completion.

Take frequent, short rest breaks.

Take frequent, short rest breaks.

Sit when working, when possible.

Sit when working, when possible.

Use ready-prepared foods when possible.

Use ready-prepared foods when possible.

Use labor-saving equipment. (Electrical equipment such as microwaves and food processors with easy-to-control on-off switches and self-cleaning ovens and self-defrosting freezers reduce manual labor requirements.) A variety of cookbooks are available for use with microwave ovens. Recipes tend to be simpler and require less preparation and shorter cooking times.

Use labor-saving equipment. (Electrical equipment such as microwaves and food processors with easy-to-control on-off switches and self-cleaning ovens and self-defrosting freezers reduce manual labor requirements.) A variety of cookbooks are available for use with microwave ovens. Recipes tend to be simpler and require less preparation and shorter cooking times.

Arrange work surfaces at a height that allows for maximal efficiency.

Arrange work surfaces at a height that allows for maximal efficiency.

To allow for easy access to supplies, items needed most often should be kept on convenient shelves at the front of the most accessible cupboards and drawers or at the back of the work surface.

Storage

A variety of storage devices can be purchased that enhance easy equipment access:

Plastic-covered racks slide under or clip to the underside of shelves, increasing visible storage space. They can be purchased at hardware stores.

Plastic-covered racks slide under or clip to the underside of shelves, increasing visible storage space. They can be purchased at hardware stores.

Peg-Boards can be hung on the wall and used to hang small pots, strainers, kitchen tongs, and spatulas.

Peg-Boards can be hung on the wall and used to hang small pots, strainers, kitchen tongs, and spatulas.

Magnetic knife racks can be placed over a counter top and can be used to store knives, peelers, and kitchen scissors.

Magnetic knife racks can be placed over a counter top and can be used to store knives, peelers, and kitchen scissors.

Lazy Susans, which can be placed in easy-to-reach cupboards or at the back of a counter, are useful for persons who have trouble bending or reaching beyond the front of the cabinet; they allow for convenient storage of jars, cans, and bottles.

Lazy Susans, which can be placed in easy-to-reach cupboards or at the back of a counter, are useful for persons who have trouble bending or reaching beyond the front of the cabinet; they allow for convenient storage of jars, cans, and bottles.

Transport.

Moving supplies safely about the kitchen is another significant challenge for the person with hemiplegia. To avoid lifting and carrying, the patient can use a rolling cart for transporting items from one side of the kitchen to the other. Ideally, the cart should have a handle at one end to provide support while walking. Dycem can be used to help secure items on the cart shelves. A clip secured to the side of the cart with glue can be used to hold a cane or walking device while the person pushes the cart with the noninvolved hand.

Stabilization.

Patients can accomplish cooking activities successfully single-handedly with adequate stabilization of items. Tasks such as opening packages and containers, peeling, slicing, making sandwiches, stirring, and mixing create problems that usually can be solved by a variety of self-help devices. The following paragraphs describe commonly used and readily accessible items for self-help.

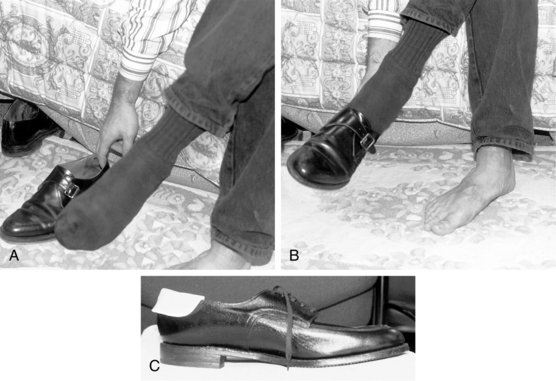

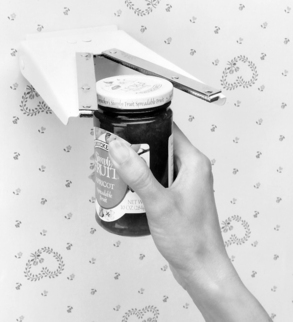

The Zim jar opener is mounted easily to the wall or underside of a cabinet and allows for one-handed screw cap removal of lids measuring from ½ to 3½ inches in diameter (Fig. 28-16).

A jar opener combined with a Belliclamp allows for easy opening of jar lids for individuals with weak grasps or use of only one hand. The Belliclamp holds jars and bottles securely during use of the jar opener. The Spill Not Jar and Bottle Opener has a plastic nonskid base with three rubber-lined openings to accommodate jars from 1 to 3 inches in diameter. A rubber lid opener provides a firm grip for easy opening of jar tops. Lightweight electrical or cordless can openers are easy to use with one hand and are available from a variety of product catalogs and appliance stores. An example is the E-Z Squeeze One Handed Can Opener (Sammons-Preston).

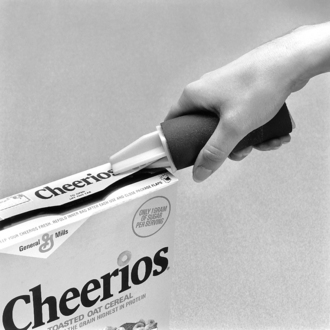

Patients can open cardboard boxes containing cereals, rice, and instant potatoes one-handed by stabilizing them firmly in a kitchen drawer and then carefully using scissors or the point of a knife to slit the boxtop open. Box toppers are inexpensive devices that easily slide open box tops and are ideal for one-handed use (Fig. 28-17).

Pan holders keep pots and pans stabilized on a range top while the individual stirs or sautés one-handed and are important to prevent spillage of hot food (Fig. 28-18).

A common device for stabilizing equipment and food items during food preparation is Dycem. The product is made from gelatinous material, is nonslip on both sides, and is an easy, inexpensive alternative to help secure items such as pans and mixing bowls in place during cooking. The Stay Put Suction Disc provides another means of securing bowls and plates to any smooth surface using vacuum pressure (Fig. 28-19). Mixing bowls with suction bases are available from a variety of product catalogs and allow for more vigorous one-handed stirring without sliding or tipping. Similarly, the Little Octopus Suction Holders are inexpensive and provide double acting grip to anchor glasses, dishes, bowls, and other common objects during meal preparation. Other items such as suction bottom nail brushes can useful during meal preparation to clean fruits and vegetables.

Cutting boards designed for one-handed use and designed from wood, Formica, or plastic come equipped with rubber suction feet to secure the board in place. Stainless steel nails hold food in place for cutting and chopping. Food guards keep food from sliding while the individual spreads butter or sandwich spreads. Cutting boards can be fabricated easily using 2-inch thick wood and nails.

Food storage.

Rigid plastic containers with overlapping lids usually are easy to open and seal with one hand.2 Plastic containers with screw-top lids are ideal for storing rice, sugar, flour, and other items that pour. Aluminum foil molds easily with one hand and is useful for covering containers and wrapping food that requires refrigeration.

Dish washing.

Nonstick cooking utensils are easy to clean and make the cleanup process go quicker. Oven-to-table cookware cuts down on the number of supplies used. Pots and pans can be stabilized for scrubbing by positioning them on a wet dishcloth positioned in the corner of the sink. For washing cups and glasses, the patient can use a brush suctioned to the inside of the sink, such as a suction bottle brush (Fig. 28-20).

Home maintenance

Work simplification methods should be applied in the performance of household tasks. Housework requires a great deal of mobility and necessitates getting into awkward positions. Housework can be made easier by removing clutter from the house. Time spent dusting is cut in half without added clutter. To conserve personal energy and ensure ease of performance, adaptive devices such as lightweight, long-handled, and electronic tools may serve as useful supplements.

Caring for the floor.

Long-handled, freestanding dustpans; self-wringing sponge mops; electrical floor scrubbers; light upright vacuum cleaners with helping hand attachments; and no-wax floors can ease the maintenance of floor care. While mopping the floor, the individual should use a rectangular bucket. This allows the sponge mop to be soaked fully with water in a half-filled bucket as opposed to partial soaking in a round bucket. The bucket should be filled and emptied on the floor with a plastic jug to avoid heavy lifting.

Cleaning the bathroom.

The patient should use a long-handled reach sponge mop to clean the bathroom. This product is available through a variety of rehabilitation catalogs. The risk of falling is great, and kneeling or sitting should be considered in the performance of this household task.

Extra cleaning materials should be kept upstairs and downstairs to avoid unnecessary journeys. Items can be transported in an apron with large pockets, a shoulder bag, or a wheeled cart.

Bed making.

Bed making can be difficult with only one hand. Beds should be positioned so that access to both sides is easy. To conserve energy, the patient can make the bed by completing each corner of one side from the undersheet to bedspread before moving to the other side to repeat the operation.

Laundry

Machine washing clothes.

The patient should select fabric and garment designs that are completely machine washable and dryable and should use automatic machines.

Ironing

The patient should use a lightweight iron. Steam irons are efficient at removing creases from many materials.

Most ironing boards are height adjustable so that the individual can sit or stand when using them. Ironing boards can be difficult and heavy to manage with one hand. The board may be left permanently standing if space permits. Ironing also can be done on the kitchen table or a counter covered with a folded towel or sheet.

Sewing

Threading needles.

A patient can thread a needle easily with one hand if the needle is held in a pincushion, padded armchair, or bar of soap. Self-threading needles and automatic needle threaders also are available at most major department stores.

Cutting.

A patient can cut material if it is stabilized by weight to prevent slipping. Although most scissors are for right-handed use, scissors and shears for left-handed use are available.

Communication

Writing.

Individuals whose strokes have affected their dominant sides need to consider dominance retraining to learn to write with the noninvolved hand. An important goal for such individuals is to be able to sign their names legibly.

Writing practice begins with exercises consisting of continuous circles and connected up and down strokes. Patients practice large strokes first and progress to smaller ones. With increasing proficiency, patients practice alphabet letters. At the initiation of training, patients should use a larger-size pencil, crayon, or rubber pencil grip attached to a standard pencil. The paper may be stabilized with Dycem or a clamp or by weighting the paper down.

Except for meeting the requirement of a functional signature, individuals may prefer to use another method of written communication. Individuals with hemiplegia can access equipment such as personal computers, tape recorders, and word processors easily.

Using the telephone.

Providing for easy access to the telephone is not a significant problem. Use of a speakerphone can facilitate telephone use. Another product, the commercially available phone holder, frees the noninvolved hand for dialing or taking messages. This device consists of a flexible arm clamped to a table, which holds the telephone receiver in a stationary position; the device is available through product catalogs.

Community-based activities

Marketing and grocery shopping

Energy conservation should be applied in marketing and grocery shopping. The individual should make a list of necessary items and anticipate weekly expenses to minimize trips to the cash machine. The patient should categorize items according to aisles, thus limiting excess walking around the store. The patient can use a lightweight pushcart to carry items around the store and home if a car is not available. Individuals using wheelchairs require assistance with shopping trips. The patient should place money in an easily accessible pocket or purse to ensure easy retrieval at the checkout line. An alternative is mail, phone, or online shopping.

Banking

Banking has become easier during the past decade. Individuals can go the bank, access money through automatic teller machines, and bank by phone or online. If the patient’s signature has been altered because of loss of function in the dominant hand, the bank must be notified. Banks have varying policies regarding this situation. For the most part, the new signature can be placed on file easily. Some banks, however, require a written and notarized letter from a physician before a new signature can be authorized.

CASE STUDY One-Handed Training after Stroke

E.B. is a 74-year-old male recovering from a left stroke with right hemiplegia and a medical history of significant hypertension. E.B. worked as an engineer for 50 years but has been retired for the past two years. He currently is married, and his wife works full-time. E.B. resides in a ground-floor apartment with three steps up to enter the building.

E.B. was referred for home care services on discharge from the hospital. Initial occupational therapy evaluation revealed the following: He was alert and oriented to person, place, situation, and time. His cognitive perceptual status was intact. Before his stroke, E.B. was right-hand dominant. On evaluation, his right upper extremity was flaccid. His left upper extremity had functional range of motion and strength. Sensation was intact throughout. Static and dynamic sitting balance was good. When standing, however, he was unsteady while performing challenging tasks. His endurance for light activity was poor. E.B. required assistance with the following ADL tasks: bathing, grooming, feeding, dressing, simple meal preparation, writing, and community-based activities.

The therapist established a number of treatment goals with the patient:

Short-term goals

1. E.B. will independently bathe himself using assistive devices.

2. E.B. will independently clean and floss his teeth with use of assistive devices.

3. E.B. will be able to cut and butter food independently with a rocker knife.

4. E.B. will independently dress himself using adaptive techniques and devices.

5. E.B. will independently prepare himself lunch.

6. E.B. will independently perform home-based financial responsibilities.

Adaptations

Before initiating basic ADL training, the therapist surveyed the environment to ensure safety and ease of mobility. The following changes were recommended and implemented:

1. Excess clutter was removed from the bedroom, bathroom, kitchen shelves, and drawers to ensure easier access of needed supplies. Closet rods were lowered to allow for easier access of clothing.

2. The bathroom floor rug was replaced with nonslip mats inside and outside the tub. A tub transfer bench with handheld shower attachment was provided.

3. A board was placed under the mattress to increase firmness, and a bedrail was placed on E.B.’s uninvolved side to increase safe transfers in and out of bed.

4. A lamp was placed on a bedside table next to E.B. to ensure sufficient lighting.

ADL training was initiated with implementation of several adaptations:

Dressing

1. Energy conservation techniques were reviewed because of E.B.’s poor endurance.

2. E.B. was able to don and doff shirts but unable to manipulate fasteners. Velcro was substituted for buttons.

3. E.B. was able to don his pants successfully with the support of a sturdy dresser placed next to the bed, which he leaned against to pull up his pants safely while standing.

4. E.B. was able to don his shoes after a piece of splinting material was molded into the shoe heel. Elastic laces allowed for easy fastening.

Feeding and simple meal preparation

A rocker knife, nonskid mat, and plate guard allowed E.B. to cut and butter his food successfully and without spillage.

E.B. also was required to make lunch for himself while his wife was at work. His favorite lunch was a ham and cheese sandwich with lettuce and tomato and a glass of apple juice.

The following kitchen adaptations were made:

1. E.B. used a rolling cart to gather necessary supplies at one time and maneuver them to the kitchen table, where he could sit to complete the task.

2. A cutting board was fabricated using 2-inch thick wood, nails, and a plastic food guard glued to the side of the board. Using the board, E.B. was able to cut tomato slices successfully, stabilize lettuce, and spread mayonnaise on a slice of bread while stabilizing it against the food guard.

3. Presliced ham and cheese were stored in a plastic zipper bag that E.B. could access easily and seal using the zipper bag sealer.

4. Using a Zim jar opener, E.B. was able to open the apple juice bottle top.

Dominance retraining and financial management

E.B. was initially right-hand dominant. An important goal for him was to be able to sign his name legibly on legal documents. He was put on a program of writing practice exercises. After obtaining a legible signature, E.B. contacted the bank and was required to submit a copy of his new signature to be placed on file.

Marketing and grocery shopping

As E.B.’s endurance improved, shopping outings with his wife were encouraged. The following energy conservation guidelines were incorporated:

1. E.B. made a list of necessary items and grouped them according to aisles to limit excess walking.

2. A lightweight pushcart was purchased to carry items around the store and into the home.

3. Before leaving home, E.B. would place his money in an easily accessible pocket from which he could retrieve it quickly at the checkout line.

Summary

This chapter describes equipment recommendations and practical and creative solutions that the occupational therapist can incorporate to assist patients in becoming more independent in performing BADL and IADL. For individuals with limited functional return of the involved upper extremity, compensatory techniques are crucial during the rehabilitation process and maximize the potential for reaching meaningful goals. As always, the therapist should concentrate on activities the patient finds most meaningful and curtail activities the individual does not want to perform. For individuals with extensive paralysis resulting from stroke, family members or hired outside help may be required to assist with ADL.

Review questions

1. When is use of compensatory strategies most advantageous as part of the rehabilitation process?

2. What environmental considerations need to be taken into account before the initiation of ADL training?

3. Where can specific information regarding the reliability and validity of BADL evaluation instruments be obtained?

4. What are some compensatory techniques and adaptive devices an individual may use during grooming and hygiene to compensate for loss of one upper extremity?

5. Which specific deficits need to be considered before the initiation of dressing training?

6. What energy conservation and work simplification techniques should be considered during IADL training?

7. Which compensatory techniques and adaptive devices should be considered to compensate during kitchen-based activities for loss of one upper extremity?

8. What types of adaptive devices should be considered for easier performance of home-maintenance activities?

9. If a signature has been altered because of loss of function in the dominant hand, what issues need to be addressed before the patient resumes financial responsibilities?

1. Feldmeier DM, Poole JL. The position-adjustable hair dryer. Am J Occup Ther. 1987;41(4):246-247.

1.a Nakayama H, Jorgensen HS, Raaschou HO, et al. Compensation in recovery of upper extremity function after stroke. the Copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994:75;8:852-857.

2. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical practice guidelines #16. post stroke rehabilitation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research. 1995.

3. Walker MF, Drummond AER, Lincoln NB. Evaluation of dressing practice for stroke patients after discharge from hospital. a crossover design study. Clin Rehabil. 1996:10;1:23.

4. World Health Organization. International classification of function. Geneva: The Organization; 2001.

Berger PE, Mensh S, Whitaker J. How to conquer the world with one hand . . . and an attitude, ed 2. Merrifield, VA: Positive Power Publishing; 2002.

Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, et al. The functional independence measure. a new tool for rehabilitation. Eisenberg MG, Grzesiak RC, editors. Advances in clinical rehabilitation, vol 1. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1987.

Kelly-Hayes M, Robertson JT, Broderick JP, et al. The American Heart Association Stroke Outcome Classification. executive summary. Circulation. 1998:97;24:8-2474.

Law M. The Canadian occupational performance measure, ed 4. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2005.

Legg L, Drummond A, Leonardi-Bee J, et al. Occupational therapy for patients with problems in personal activities of daily living after stroke. systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ. 2007:335;7626:922.

Mahoney FI, Barthel D. Functional evaluation. the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:56-61.

Mayer TK. One-handed in a two-handed world, ed 2. Boston: Prince-Gallison Press; 2000.

Nakayama H, Jorgensen HS, Raaschou HO, et al. Compensation in recovery of upper extremity function after stroke. the Copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994:75;8:852-857.

Steultjens EMJ, Dekker J, Bouter LM, et al. Occupational therapy for stroke patients. a systematic review. Stroke. 2003:34;3:676-687.

Trombly CA, Ma HI. A synthesis of the effects of occupational therapy for persons with stroke, Part I. Restoration of roles, tasks, and activities. Am J Occup Ther. 2002:56;3:9-250.

van Swieten J, Koudstaal P, Visser M, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604-607.