CHAPTER 5 Storage disorders and incontinence

INTRODUCTION

Storage disorders are common in both men and women and are often associated with urinary incontinence. Overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome affects approximately 12% of adult males and females in the population and the prevalence increases with age, whilst urinary incontinence affects millions of individuals worldwide, 85% of whom are women. More than one-third of healthy elderly women and approximately 50% of institutionalized females suffer from incontinence with estimates indicating that as many as one in four women experience urinary incontinence during their lifetime.

OAB and particularly urinary incontinence carry a considerable social stigma; many sufferers are unable to continue with their daily activities and many give up their employment. Not only are the symptoms troublesome but they are extremely embarrassing and can have a profound psychological as well as a social, sexual and hygienic impact. Many patients adopt elaborate coping mechanisms including voiding frequently, mapping out the location of toilets, drinking less or wearing dark clothing to mask incontinent episodes. Others resort to wearing incontinence pads or sanitary towels.

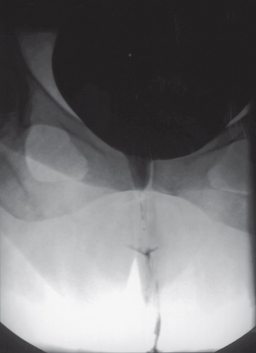

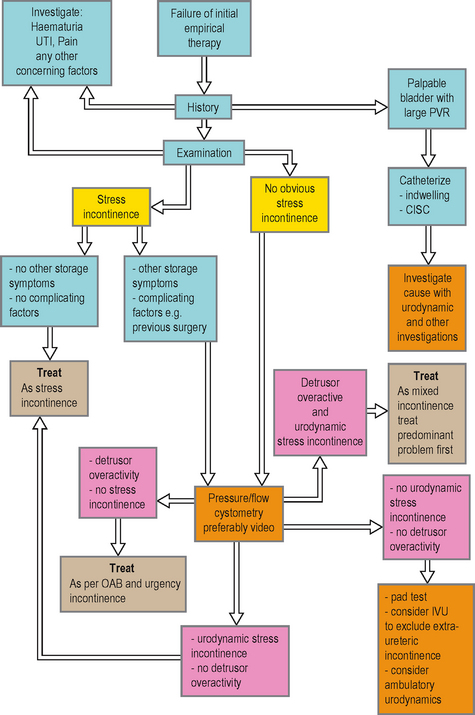

However, many successful treatments are available for these conditions; therefore it is important that sufferers are offered a suitable treatment and frequently urodynamics are required to determine the most appropriate management choice. A simple algorithm for the investigation of incontinence is shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Algorithm for the investigation of urinary incontinence. Initial investigations should focus on differentiating between detrusor overactivity and urodynamic stress incontinence, although the conditions frequently co-exist as mixed incontinence. CISC, clean intermittent self-catheterization; IVU, intravenous urogram.

OVERACTIVE BLADDER SYNDROME AND URGENCY INCONTINENCE

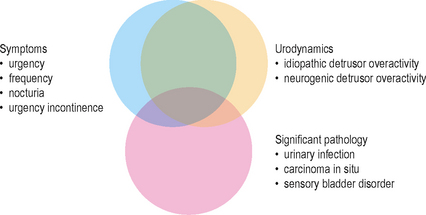

Overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome is defined as ‘urgency, with or without urgency incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia’. OAB can only be diagnosed if infection or other obvious pathologies that may cause the symptoms are excluded. OAB is also known as urgency syndrome and urgency/frequency syndrome. These symptom combinations are frequently associated with demonstrable detrusor overactivity (DO) during the filling phase of pressure/flow cystometry.

CLINICAL NOTES: PATIENT EVALUATION OF STORAGE DISORDERS AND INCONTINENCE

OAB can be further categorized as:

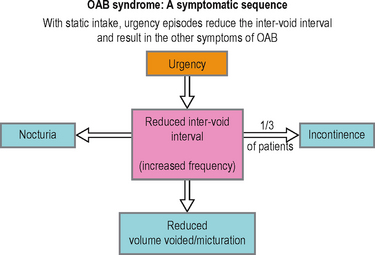

It is believed that the driving force within OAB is the symptom of urgency, defined as ‘the complaint of a sudden compelling desire to pass urine, which is difficult to deter’ (Figure 5.2). Urgency may compel the sufferer to void more frequently than normal and to wake from sleep to void. Increased frequency can also partly be a result of an adaptive or coping mechanism to suppress urgency. If urgency is severe and the patient has little warning or is not able to reach a toilet in time, then urgency incontinence may occur. Approximately 30% of patients with OAB have urgency incontinence, although the prevalence increases significantly in the elderly with multiple co-morbidities.

As urgency is frequently associated with detrusor overactivity (DO) during cystometry, it had been previously hypothesized that the pathology was due to dysfunction in the efferent motor innervation of the bladder. However, significant emerging evidence suggests that the dysfunction (or its central nervous system interpretation) is at least partly (if not wholly) due to afferent sensory dysfunction and this would be in concordance with the pivotal symptom of urgency being an essentially sensory symptom (Figure 5.3). Though the majority of OAB and urgency incontinence patients are classified as ‘idiopathic’, a number of clinical causes should be considered:

Figure 5.3 Overlap of OAB storage symptoms, urodynamic findings and other pathologies. Showing a large correlation of symptoms with urodynamic evidence of DO. However a small subset of these patients will also have other significant pathologies.

Frequently the symptoms are triggered by certain events such as running water, ‘key in the door’, ‘foot on the floor’, giggling, exertion or female orgasm.

Management of OAB and urgency incontinence

A large number of patients are treated empirically often by their primary care physician. If successfully managed and if important pathologies such as bladder carcinoma (Figure 5.4) and UTI have been excluded then there is often little need for further investigations. Frequently however the patient may have equivocal symptoms or the condition may not respond to initial therapy; in such circumstances the patient should be referred to secondary care for a more detailed evaluation and a greater range of management options. Successful management of OAB requires that the condition is accurately diagnosed and differentiated from other lower urinary disorders such as stress incontinence.

Figure 5.4 Other causes of storage symptoms. (a) A superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder in a patient with predominant storage symptoms. (b) Cystoscopic evidence of a suture and bladder calculus in a patient with storage symptoms following an abdominal hysterectomy.

Urodynamics in OAB and urgency incontinence

Voiding diaries

Should be used during the initial evaluation and subsequent monitoring to give an estimate of the frequency and voided volumes. They are also be useful in ruling out suspected nocturnal polyuria. Prior to performing invasive urodynamics a voiding diary will give an estimate of the bladder capacity, and this information should be used to prevent overfilling during the assessment.

1-hour pad test

Useful in patients strongly suspected of urinary incontinence but who have failed to demonstrate any leakage on other investigations such as video urodynamic pressure/flow studies (Figure 5.5). Approximately 30% of patients with urgency incontinence have a normal pressure/flow study. The test also gives a quantification of the degree of incontinence, as patients are usually inaccurate when asked to quantify the leakage.

Uroflowmetry

Not a particularly useful test in this condition, although may be beneficial in ruling out voiding dysfunction as a cause of the storage symptoms, such as in men with mixed LUTS. Should be performed prior to pressure/flow cystometry to give a more representative indication of the voiding pattern than is possible during invasive cystometry.

Pressure/flow cystometry

The gold standard test for detecting detrusor overactivity (DO) which is characterized by involuntary detrusor contractions (IDCs) during the filling phase. DO is thought to be the underlying cause for the symptom of urgency which drives the other symptoms in OAB and which may cause urgency incontinence. Pressure/flow cystometry should be used when a patient has been refractory to empirical therapy, to confirm the presence of DO before proceeding to further treatments. It is essential before considering any invasive treatments such as botulinum toxin therapy or surgery. In addition to clarifying the diagnosis it will help characterize other aspects of lower urinary tract function that may predict problems following an invasive procedure, for example a patient with concurrent voiding dysfunction may be more likely to require clean intermittent self-catheterization (CISC) following botulinum toxin therapy.

Cystometry is also valuable in determining the underlying diagnosis in patients with a mixture of storage and voiding symptoms such as men who may have OAB and also bladder outlet obstruction (BOO). Similarly, in women with a mixture of symptoms suggestive of both urgency incontinence and stress incontinence video cystometry is invaluable in determining if both conditions are present (mixed incontinence) and which is the predominant problem requiring focused treatment. Note that the presence of urgency (but not urgency incontinence) and stress incontinence is known as mixed symptoms.

Non-urodynamic tests

A number of validated questionnaires are available to determine the severity of the condition and the impact on the quality of life. These are useful both in the initial assessment of severity and also to monitor the impact of treatment. Common questionnaires include the King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ), Patients Perception of Bladder Condition (PPBC), the International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) and the Short Form-36 (SF36) questionnaire.

Urodynamic findings in OAB and urgency incontinence Table 5.1)

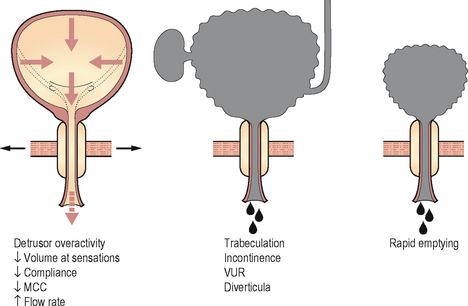

Detrusor overactivity

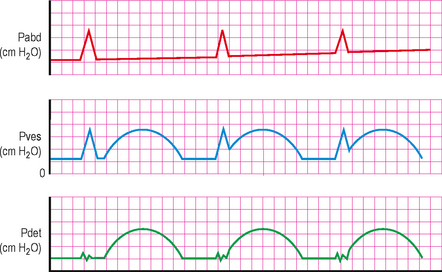

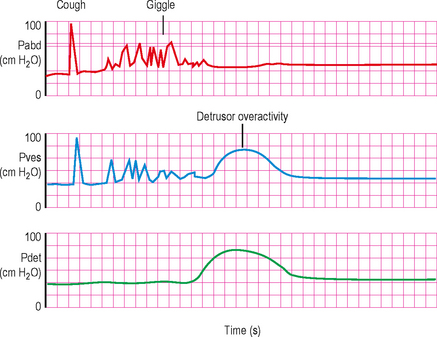

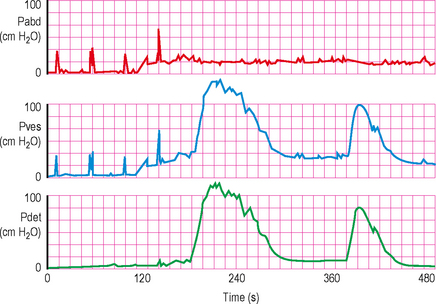

The characteristic finding of DO during pressure/flow cystometry is shown in Figure 5.6. In patients with a known neurological cause for the lower urinary tract dysfunction this is described as neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO; see Chapter 9), whereas when the aetiology is unknown it is described as idiopathic detrusor overactivity (IDO). DO was previously called detrusor instability and NDO was previously called detrusor hyperreflexia.

Table 5.1 Possible findings during urodynamic testing of patients with OAB or urgency incontinence.

| Possible findings during urodynamic testing of patients with OAB or urgency incontinence | |

|---|---|

| Voiding diaries | |

| 1-hour pad test | |

| Uroflowmetry | |

| Pressure/flow cystometry (Figure 5.5) | |

Figure 5.6 High pressure detrusor overactivity. Note the rise in intra-vesical activity which is mirrored in the detrusor trace. This is the hallmark of detrusor activity, as the lack of activity in the intra-abdominal trace confirms that the activity has emanated from within the bladder.

If DO is detected then it should be ascertained if there is associated urgency and if the urgency sensation is the same as the troublesome symptom the patient normally experiences. The volume at which DO occurs and the rise in amplitude should be documented as described in Chapter 4, as should any associated leakage. It should also be stated if the DO was spontaneous or provoked.

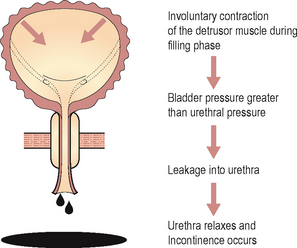

Frequently, phasic (systolic) contraction activity with increasingly frequent and higher amplitude contractions occur as the bladder continues to be filled (Figure 5.7). Often, a large terminal contraction occurs at which time the patient feels that he/she can no longer delay micturition and they have therefore reached maximum cystometric capacity (MCC). The patient should be allowed to void voluntarily at this point. If voiding is delayed then the patient will frequently be incontinent (Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.7 Phasic detrusor overactivity, showing a wave of detrusor contractions, in this case with each contraction rising in amplitude and being of slightly longer duration.

Increasingly forceful detrusor overactivity associated with urgency can cause significant discomfort for the patient and incontinence is embarrassing. Therefore if the presence of detrusor overactivity has answered the ‘urodynamic question’, there is no need to significantly delay entering the voiding phase of the study as little additional information is likely to be gained.

Cough induced incontinence

Frequently the abrupt change in intra-abdominal pressure during coughing provokes urinary incontinence (Figure 5.9). This is often confused with stress incontinence on the history alone but during video urodynamics DO is seen immediately following a cough with associated urinary leakage. Changing patient position, for instance to the standing position, may similarly trigger DO.

STRESS INCONTINENCE

Stress incontinence is predominantly a female problem and depending on the definition and the population studied the prevalence of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is estimated to affect between 4% and 35% of the adult female population, with an apparent increase in prevalence with age. In men, stress incontinence is most commonly seen in patients following a radical prostatectomy.

The current ICS definition of the symptom is ‘the complaint of involuntary leakage on effort or exertion, or on sneezing or coughing’. If involuntary leakage is observed during increased abdominal pressure, in the absence of a detrusor contraction during an urodynamic assessment; then the patient is described as having ‘urodynamic stress incontinence (USI)’. This term replaces the older term of genuine stress incontinence (GSI).

Stress incontinence can affect females of any age and any parity. Although it is particularly common in multiparous women who have had traumatic or prolonged vaginal deliveries and is usually associated with loss of pelvic floor support and/or damage to the sphincter mechanism. This results in either:

Many females with SUI will have a combination of both bladder neck descent/hyper-mobility and ISD, but there is some dispute about the relative importance of these in USI and any delineation into these categories may be simplistic and arbitrary and requires further research (see Chapter 2).

Management of stress incontinence

Initial therapy can be commenced empirically by the primary care physician. However if this fails, the patient should be evaluated in secondary care for consideration of a surgical procedure to improve the symptoms.

Available treatment choices include:

Urodynamics in stress incontinence

Voiding diaries

Particularly useful in those with mixed symptoms suggestive of stress and urgency incontinence. Useful if leakage (urge versus stress) is recorded to document the frequency of stress incontinence episodes. Prior to performing invasive urodynamics a voiding diary will give an estimate of the bladder capacity, and this information should be used to prevent overfilling during the assessment. Many women with stress urinary incontinence alter their behaviour to try to cope better with the condition; for example they may increase their urinary frequency to maintain an empty or low volume bladder and thereby reduce the frequency or severity of any stress incontinence.

1-hour pad test

Useful in patients strongly suspected of urinary incontinence but who have failed to demonstrate any leakage on other investigations such as video urodynamic studies. The test gives a quantification of the degree of incontinence.

Uroflowmetry

Not a particularly useful test in this condition; although may be beneficial in ruling out any voiding dysfunction which may complicate treatment. Should be performed prior to pressure/flow cystometry to give a more representative indication of the voiding pattern than is possible during invasive cystometry. Exaggerated flow rate or ‘fast void’ may be seen in patients with significant urethral insufficiency.

Pressure/flow cystometry

Video urodynamics is the gold standard test and allows leakage to be visualized with increases in intra-abdominal pressure. In addition, bladder neck opening and bladder neck descent/hyper-mobility can also be assessed during screening. In the simplest of cases where there are no uncertainties regarding the diagnosis and no complicating factors, pressure/flow assessment is not required prior to surgery, although this recommendation remains controversial and a diagnosis made on the basis of history alone will not predict detrusor overactivity in up to 25% of cases. In all other cases urodynamics should be performed to confirm the diagnosis, rule out other causes for the incontinence such as urgency incontinence or cough provoked incontinence and assess for possible post-operative complications. For example poor voiding function may suggest a potential need for CISC following an invasive procedure. Cystometry is recommended when considering an invasive procedure in somebody who has previously been treated operatively.

Other urodynamic tests

Electromyography (EMG) measurement during pressure/flow studies may give an indication of the pelvic floor and/or sphincter activity. UPP measurement (Chapter 3) and ALPP (Chapter 4) may help determine if ISD is the cause of the SUI and possibly direct further management. However, all of these tests are non-standardized and currently provide data of uncertain clinical significance (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Possible findings during urodynamic testing of patients with stress incontinence.

| Possible findings during urodynamic testing of patients with stress incontinence | |

|---|---|

| Voiding diaries | |

| 1-hour pad test | |

| Uroflowmetry | |

| Pressure/flow cystometry |

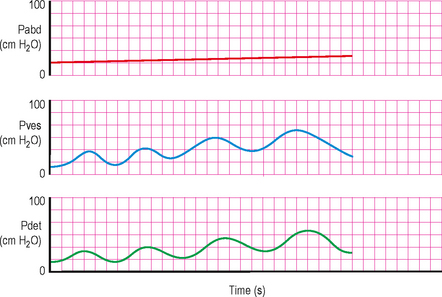

• Voiding is usually rapid with a high flow rate (30–60 ml/s) and low voiding pressures, due to reduced outflow resistance (Figure 5.10)

|

| Electromyography | |

| Urethral pressure profilometry | |

| Abdominal leak point pressures | |

Non-urodynamic tests

Cystoscopy adds little to the evaluation of patients who have stress incontinence, but it is occasionally helpful in assessing the short fibrotic ‘stove-pipe’ urethra sometimes present in patients who have ISD. Complex patients suspected of having a vesical fistula or urethral diverticulum require an appropriate diagnostic workup, including cystoscopy.

Urodynamic findings in stress incontinence

Video urodynamics

Bladder neck descent and hyper-mobility

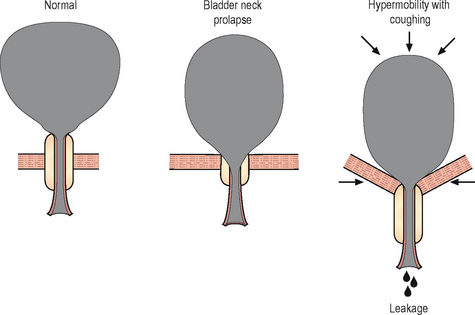

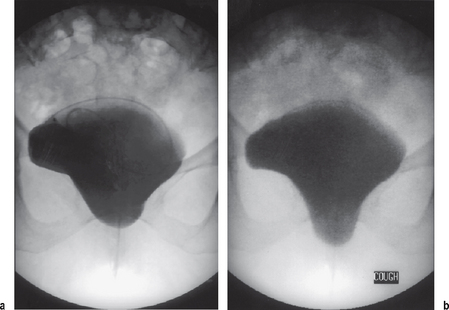

When the bladder descends due to poor pelvic floor support, increases in intra-abdominal pressure are not transmitted equally to the bladder body and proximal urethra (Figure 5.10, 5.11). Most of the increased pressure is transmitted only to the bladder. This elevates the intra-vesical pressure above the maximum pressure exerted by the urethral sphincter mechanism, resulting in stress incontinence. This is easily visualized with video urodynamics, when standing partially obliquely, the bladder neck position may be abnormally low (below the level of the upper third of the pubic symphysis), signifying loss of pelvic floor support, coughing or valsalva causes the bladder and bladder neck to descend further and leak (Figure 5.12). On termination of the increased intra-abdominal pressure the bladder neck quickly ‘springs back’ to its original position terminating leakage.

Figure 5.10 (a) and (b) Typical video urodynamic appearances for urodynamic stress incontinence, showing low pressure, high flow due to decreased bladder outlet resistance and also showing radiological evidence of an open bladder neck.

Figure 5.11 Stress incontinence in bladder neck descent/hyper-mobility, showing lack of transmission of pressure to the urethra, resulting in leakage.

Figure 5.12 Radiological appearances of bladder neck descent. (a) Cystogram of a female patient in the supine position showing a degree of bladder base prolapse. (b) The same patient on coughing showing descent of the bladder base and urethra; on the dynamic screening image leakage was visible.

Whether to reduce a prolapse during a urodynamic study, both to compensate for the ‘kinking’/‘obstructive’ effect of a cysto-urethrocoele and to replicate the effect of a surgical procedure is often discussed and still remains the subject of debate but limited consensus.

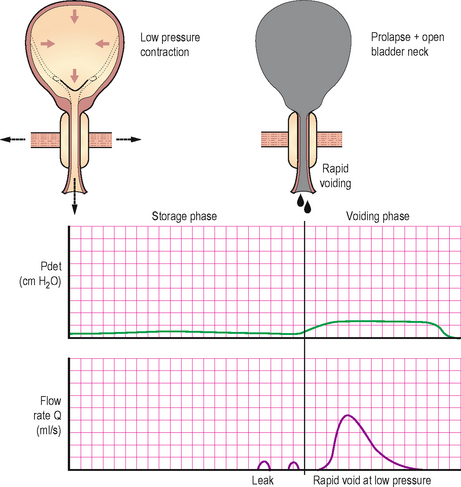

Intrinsic sphincter deficiency

With intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) the sphincter mechanism is weakened and therefore unable to resist the increases in intra-vesical pressure that occur with stress (Table 5.3). When severe, even the slightest increase in pressure (e.g. from minor movement) may cause leakage or the sphincter may be completely open (incompetent) with almost continual leakage. Many patients are unable to interrupt micturition due to weakness of their striated sphincter mechanism. Unfortunately, there is no consensus regarding how best to assess for ISD, with advocates for physical examination (Q tip test), video urodynamics, urethral pressure measurements and abdominal leak point pressure measurements (ALPP > 100 cm H2O unlikely to be ISD, ALPP < 60 cm H2O suggestive of ISD). This area needs further research, particularly with recent developments in therapies aimed specifically at treating ISD as opposed to bladder neck descent/hyper-mobility. However, in our opinion (based on current evidence) video urodynamics is essential to differentiate between the relative contributions of bladder neck prolapse/hyper-mobility and ISD, because it deals with function, anatomy and dynamics. Typically on video urodynamics patients with pure ISD demonstrate severe leakage with minimal increase in intra-abdominal pressure, there is minimal bladder neck descent and the urethra does not ‘spring back’, but appears to stay open and continues leaking even after the stress event. Often there is a rectangular shaped incompetent bladder neck (Figure 5.13) and this should be differentiated from the ‘beaking’ of the bladder neck that is probably a normal finding, even in continent females.

Table 5.3 Intrinsic sphincter deficiency: contributory causes.

| Contributory causes to intrinsic sphincter deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Causes |

| Urethral trauma | Pelvic fracture, traumatic childbirth |

| Neurological disorder | Myelodysplasia |

| Vaginal delivery | Pudendal nerve injury |

| Previous operation | Failed operation for incontinence, urethral dilatation, urethral diverticulectomy, radical prostatectomy |

OTHER TYPES OF INCONTINENCE

Mixed urinary incontinence

This is the complaint of involuntary leakage associated with urgency and also with exertion, effort, sneezing or coughing. Therefore it is a combination of:

This problem is particularly common and presents a management dilemma, as patients are often refractory to initial treatments and certain treatments may aggravate the other component of the incontinence. For example treating the stress component with an invasive procedure may aggravate the urgency incontinence component. Patients with mixed incontinence symptoms should ideally undergo video urodynamics to determine which component predominates and is associated with the most troublesome symptoms. Treating the most troublesome component first usually achieves the best long term results and often a variety of treatments are needed to optimize management.

Overflow incontinence

This is the involuntary loss of urine associated with overdistension of the bladder secondary to inefficient bladder emptying. It may occur as a result of:

Overflow incontinence is often seen in elderly men with chronic retention. Patients with inefficient bladder emptying and overdistension may present with unconscious dribbling, urinary frequency, urgency or stress urinary incontinence. For this reason determination of the post-void residual urine volume is important in all patients with urinary incontinence to rule out chronic retention.

Unconscious incontinence

This is unperceived involuntary incontinence of urine, neither related to abdominal straining nor associated with urgency. The patient’s first sensation is wetness. Its identification is important because it usually represents marked bladder dysfunction.

Most patients who have unconscious incontinence have either:

Situational urinary incontinence

These are types of urinary incontinence that only occur in certain situations, and they may be related to underlying stress incontinence or underlying DO, for example during sexual intercourse or during giggling (often called giggling incontinence); see (Figure 5.14).

Continuous urinary incontinence

This is the complaint of continuous leakage of urine. This may be due to a vesical fistula, for example a vesico-vaginal fistula, a congenital abnormality, for example an ectopic ureter, or possibly due to gross intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Some elderly patients with significant urethral insufficiency and/or severe detrusor overactivity report leaking ‘all the time’.

Co-existence of different types of incontinence

Any of the types of incontinence described above can exist in combination. As with mixed incontinence identification of the various contributory factors are important because they influence treatment selection and help in anticipating post-operative problems. Video urodynamics, in combination with a thorough urological history and physical examination forms the cornerstone of the evaluation of these more complex patients.

INCONTINENCE IN MEN

Urinary incontinence is far less common in men due to the much more adequate urethral/sphincter mechanism. Most cases of male incontinence are due to:

Urodynamics forms the cornerstone for evaluating male voiding dysfunction. Indications for pressure/flow cystometry include:

POST-PROSTATECTOMY INCONTINENCE

Urinary incontinence can be one of the most debilitating and devastating complications following prostatectomy. Its incidence following transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is less than 1% but following radical prostatectomy for prostatic carcinoma the incidence of severe or total incontinence is approximately 2–12%, with up to 50% of patients complaining of milder stress leakage.

Usually during a prostatectomy the proximal urethral sphincter is ablated, therefore continence is maintained only by the distal urethral sphincter which is composed of both striated and smooth muscle components (see Chapter 2). However if there is pre-existing incompetence of the distal urethral sphincter or if it (or it’s innervation) is damaged by surgery then incontinence may occur.

Predisposing causes of distal sphincteric damage before prostatectomy include:

Sphincteric incompetence resulting from surgery is usually due to:

Because the intrinsic smooth muscle of the distal sphincter mechanism is separate from the extrinsic striated muscle of the peri-urethral pelvic floor, most patients with post-prostatectomy incontinence are capable of stopping and starting their urinary stream using the peri-urethral striated muscles.

However, not all post-prostatectomy incontinence is secondary to distal sphincteric incompetence. Other causes include:

Detrusor overactivity may be present in up to 50% of patients who are incontinent following prostatectomy and may be the underlying cause of the incontinence or a significant contributing factor.

Patient evaluation in post-prostatectomy incontinence

Patients with incontinence following prostatectomy require an in-depth history and physical examination. Most patients give a history of stress incontinence and slow dribbling leakage when standing upright. Many patients are continent when supine and only experience stress or urgency incontinence when changing posture to the standing position. On examination patients who have sphincteric incompetence often leak when asked to perform a valsalva manoeuvre. Any abnormal neurology may suggest an underlying abnormality leading to sphincteric denervation. Overflow incontinence can also be ruled out by suprapubic palpation and measuring a PVR. Urinalysis is necessary to exclude a UTI.

URODYNAMICS IN PRACTICE: POST-PROSTATECTOMY INCONTINENCE

Management

The therapeutic armamentarium for post-prostatectomy incontinence includes:

The success rate for peri-urethral injection therapy is less than 30%. The treatment of choice for post-prostatectomy stress incontinence secondary to sphincteric incompetence is the artificial urinary sphincter (AUS); approximately 90% of patients achieve social continence and nearly 50% achieve complete continence. In experienced hands, the AUS gives patients the highest chance of cure and should be offered to appropriate patients.