3 The Primary (Deciduous) Teeth

Life Cycle

After the roots of the primary dentition are completed at about age 3, several of the primary teeth are in use only for a relatively short period. Some of the primary teeth are found to be missing at age 4, and by age 6, as many as 19% may be missing.1 By age 10, only about 26% may be present. The second molars in both arches and the maxillary incisors appear to be the most unstable of the primary teeth. Even so, the developing and completed primary dentition serves a number of purposes during that time and the period of transition to the permanent dentition.

Importance of Primary Teeth

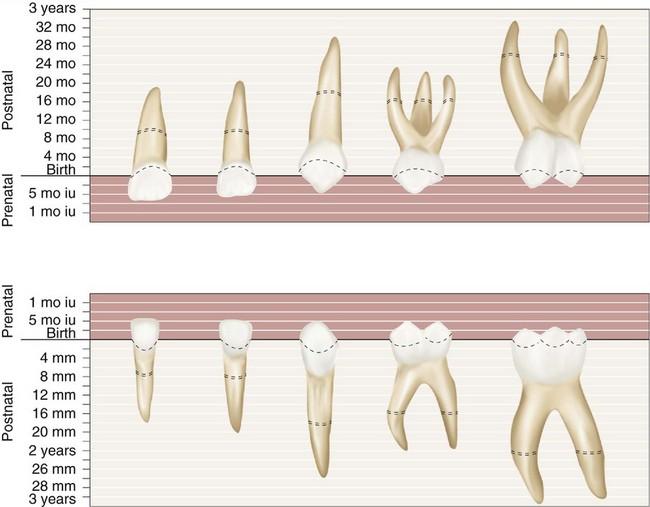

The general order of eruption of the primary dentition is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 3-1: central incisor, lateral incisor, first molar, canine, and second molar, with the mandibular pairs preceding the maxillary teeth.2,3 The loss of the deciduous teeth tends to mirror the eruption sequence: incisors, first molars, canines, and second molars, with the mandibular pairs preceding the maxillary teeth.

Figure 3-1 Diagrammatic representation of the chronology of the primary teeth. Eruption is completed at the approximate time indicated by the dotted area on the roots of the teeth. iu, Intrauterine.

(Modified from McBeath EC: New concept of the development and calcification of the teeth, J Am Dent Assoc 23:675, 1936; and Noyes EB, Shour I, Noyes HJ: Dental histology and embryology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 1938, Lea & Febiger.)

The high peak for caries attack occurs at age 13, when only 5% of the primary teeth remain. The susceptibility to dental caries is a function of exposure time to the oral environment and morphological type. The increase in prevalence of dental caries among tooth types is the reverse of their order of eruption. However, the relative susceptibility of different tooth surfaces is a complex problem. Although dental caries of the primary dentition and loss of these teeth are sometimes thought of erroneously as only an annoyance, this belief fails to acknowledge the role of the primary teeth in mastication and their function in maintaining the space for eruption of the permanent teeth.

A lack of space associated with premature loss of deciduous teeth is a significant factor in the development of malocclusion and is considered in Chapter 16. The development of adequate spacing (Figure 3-2) is an important factor in the development of normal occlusal relations in the permanent dentition. Thus there should be no question of the importance of preventing and treating dental decay and providing the child with a comfortable functional occlusion of the deciduous teeth. Therefore in this book the primary teeth are described in advance of the permanent dentition so that they may be given their proper sequence in the study of dental anatomy and physiology. The development of the primary occlusion is considered in Chapter 16.

Nomenclature

Some of the terminology for the primary dentition has already been introduced in Chapter 2; therefore the coverage here is more in the nature of a review. The process of exfoliation of the primary teeth takes place between the seventh and the twelfth years. This does not, however, indicate the period at which the root resorption of the deciduous tooth begins. It is only 1 or 2 years after the root is completely formed and the apical foramen is established that resorption begins at the apical extremity and continues in the direction of the crown until resorption of the entire root has taken place and the crown is lost from lack of support.

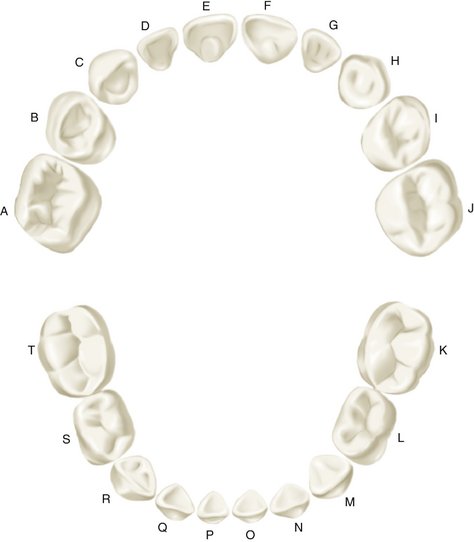

The primary teeth number 20 total—10 in each jaw—and they are classified as follows: four incisors, two canines, and four molars in each jaw. Figure 3-3 shows the primary dentition as numbered with the universal system of notation described in Chapter 1. Beginning with the median line, the teeth are named in each jaw on each side of the mouth as follows: central incisor, lateral incisor, canine, first molar, and second molar.

Figure 3-3 Universal numbering system for primary dentition.

(From Ash MM, Ramfjord S: Occlusion, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1995, Saunders.)

The primary teeth have been called temporary, milk, or baby teeth. These terms are improper because they foster the implication that these teeth are useful for a short period only. It is emphasized again that they are needed for many years of growth and physical development. Premature loss of primary teeth because of dental caries is preventable and is to be avoided.

The first permanent molar, commonly called the 6-year molar, makes its appearance in the mouth before any of the primary teeth are lost. It comes in immediately distal to the primary second molar (see Figure 2-10).

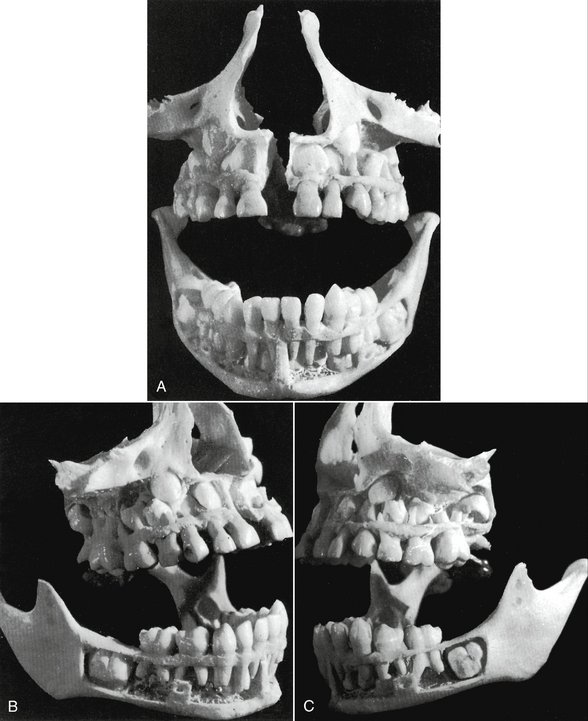

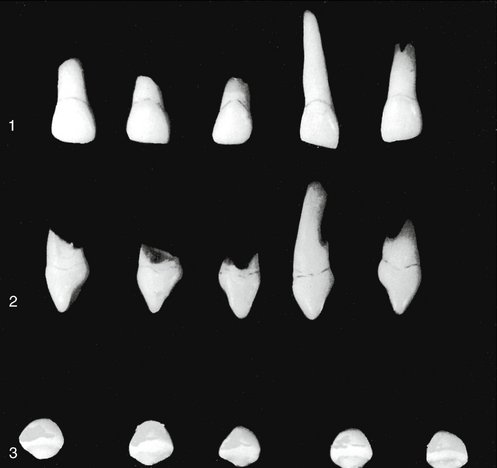

The primary dentition is complete at about 2.5 years of age, and no obvious intraoral changes in the dentition occur (Figures 3-4 and 3-5) until the eruption of the first permanent molar. The position of the incisors is usually relatively upright with spacing often between them. Attrition occurs, and a pattern of wear may be present.

Figure 3-4 A, This is a specimen of a 5- to 6-year-old child prepared to show a full complement of primary teeth, the beginning of resorption of deciduous roots in some, and no apparent resorption in others. This front view shows the relative positions of the developing crowns of the permanent anterior teeth. The maxillary central and lateral incisors and the canine are shown overlapped in a narrow space, waiting for future development of the maxilla that will allow them to develop roots and improve the alignment. B, Right side. Unless they were lost in preparation, no development shows of mandibular permanent premolars. The tiny cusps formed at this age would be lost easily in preparation. C, Left side. Note the crowns of permanent maxillary premolars located between the roots of the first and second primary molars, with their roots still intact. Note the well-developed first permanent maxillary molar entirely erupted with half its roots formed. Ordinarily, the mandibular first permanent molar comes in and takes its place first, the maxillary molar following. The specimen shows the mandibular molar still covered with bone and no roots in evidence. The maxillary second molar crown is well developed and located in a place that is about level with the present root development of the permanent maxillary first molar.

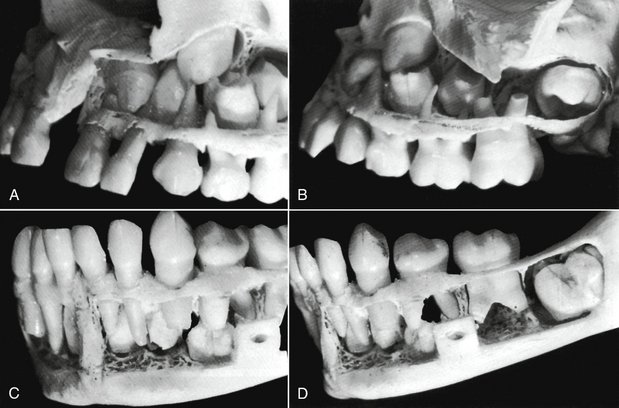

Figure 3-5 A sectional close-up of the specimen in Figure 3-4. A, The left side of the maxilla. The developing crowns of the central and lateral incisors, the canine, and two premolars are clearly in view. B, The left side of the maxilla, posteriorly. The molar relationship, both deciduous and permanent, is accented here. C, This is a good view of the mandible anteriorly and to the left. Permanent central and lateral incisors and the canine may be seen. Notice that the permanent canine develops distally to the primary canine root. D, Posteriorly, examination of the specimen mandible fails to find crown development of permanent premolars. However, the hollow spaces showing between the roots of primary molars may indicate a loss of material during the difficult process of dissection. The first permanent molar has progressed in crown formation, but the maturation of the whole tooth with alignment is far behind its opposition in the maxilla above it (see Figure 3-4, C).

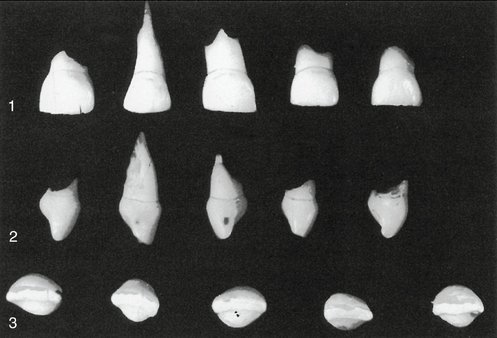

The primary molars are replaced by permanent premolars. No premolars are present in the primary set, and no teeth in the deciduous set resemble the permanent premolar. However, the crowns of the primary maxillary first molars resemble the crowns of the permanent premolars as much as they do any of the permanent molars. Nevertheless, they have three well-defined roots, as do maxillary first permanent molars. The deciduous mandibular first molar is unique in that it has a crown form unlike that of any permanent tooth (see Figure 3-24, C). It does, however, have two strong roots, one mesial and one distal—an arrangement similar to that of a mandibular permanent molar. These two primary teeth, the maxillary and mandibular first molars, differ from any teeth in the permanent set when crown forms are compared, in particular (see Figures 3-21 and 3-24). The primary first molars, maxillary and mandibular, are described in detail later in this chapter.

Major Contrasts between Primary and Permanent Teeth

In comparison with their counterparts in the permanent dentition, the primary teeth are smaller in overall size and crown dimensions. They have markedly more prominent cervical ridges, are narrower at their “necks,” are lighter in color, and have roots that are more widely flared; in addition, the buccolingual diameter of primary molar teeth is less than that of permanent teeth.4 More specifically, in comparison with permanent teeth, the following differences are noted:

Pulp Chambers and Pulp Canals

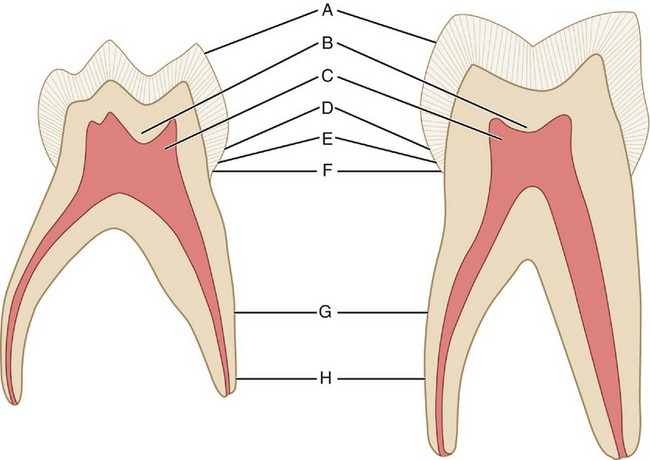

A comparison of sections of primary and permanent teeth demonstrates the shape and relative size of pulp chambers and canals (Figure 3-6), which is noted here:

Figure 3-6 Comparison of maxillary, primary, and permanent second molars, linguobuccal cross section. A, The enamel cap of primary molars is thinner and has a more consistent depth. B, A comparatively greater thickness of dentin is over the pulpal wall at the occlusal fossa of primary molars. C, The pulpal horns are higher in primary molars, especially the mesial horns, and pulp chambers are proportionately larger. D, The cervical ridges are more pronounced, especially on the buccal aspect of the first primary molars. E, The enamel rods at the cervix slope occlusally instead of gingivally as in the permanent teeth. F, The primary molars have a markedly constricted neck compared with the permanent molars. G, The roots of the primary teeth are longer and more slender in comparison with crown size than those of the permanent teeth. H, The roots of the primary molars flare out nearer the cervix than do those of the permanent teeth.

(From Finn SB: Clinical pedodontics, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1957, Saunders.)

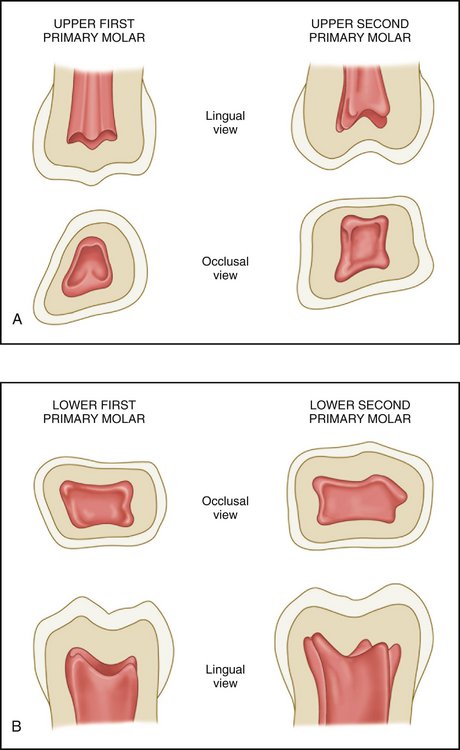

Figure 3-7 A and B, Pulp chambers in the primary molars. Note the contours of the pulp horns within them.

(Modified from Finn SB: Clinical pedodontics, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1957, Saunders.)

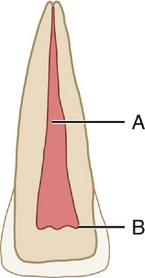

Studying the comparisons between the deciduous and the permanent dentitions (Figures 3-8 and 3-9) is of utmost importance. Discussion of further variations between the macroscopic form of the deciduous and the permanent teeth follows, with a detailed description of each deciduous tooth.

Figure 3-8 Permanent central incisor. A, Pulp canal; B, pulp horns. This figure represents a sectioned central incisor of a young person. Although the pulp canal is rather large, it is smaller than the pulp canal shown in Figure 3-9, and it becomes more constricted apically. Note the dentin space between the pulp horns and the incisal edge of the crown.

Figure 3-9 Primary central incisor. A, Pulp canal; B, pulp horns. This figure represents a sectioned primary central incisor. The pulp chamber with its horns and the pulp canal are broader than those found in Figure 3-8. The apical portion of the canal is much less constricted than that of the permanent tooth. Note the narrow dentin space incisally.

Detailed Description of Each Primary Tooth

MAXILLARY CENTRAL INCISOR

Labial Aspect

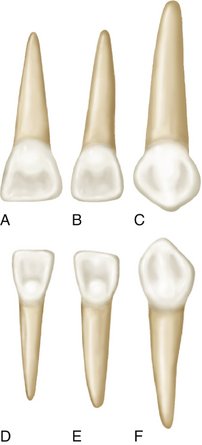

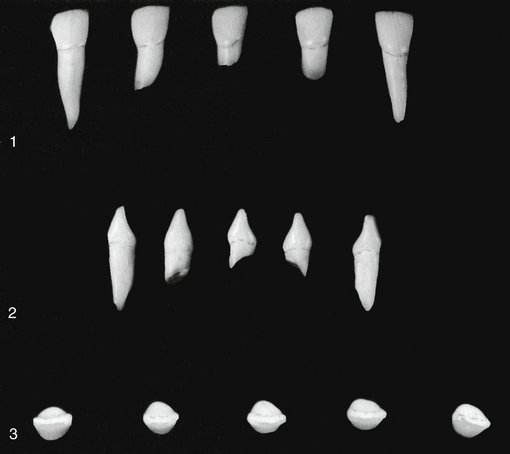

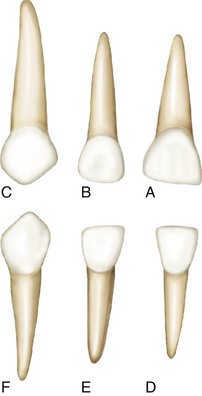

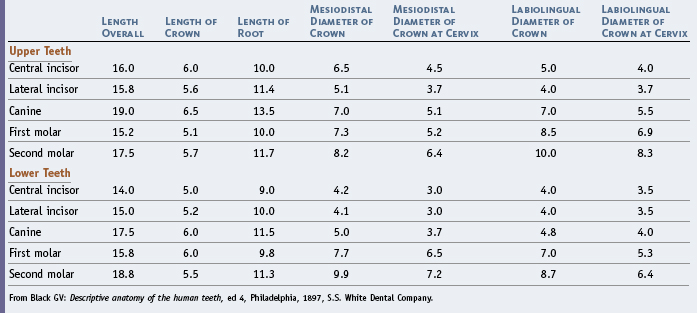

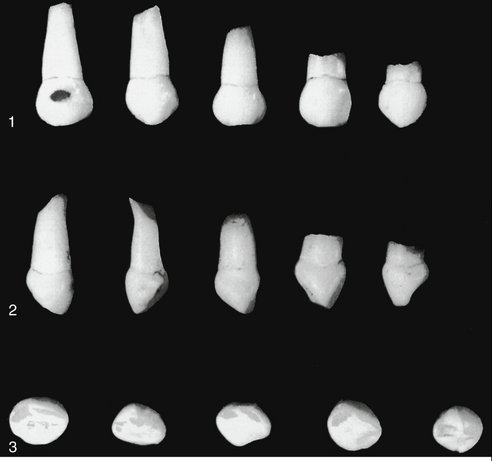

In the crown of the primary central incisor, the mesiodistal diameter is greater than the cervicoincisal length (Figures 3-10 and 3-11, A). (The opposite is true of permanent central incisors.) The labial surface is very smooth, and the incisal edge is nearly straight. Developmental lines are usually not seen. The root is cone-shaped with even, tapered sides. The root length is greater in comparison with the crown length than that of the permanent central incisor. It is advisable when studying both the primary and permanent teeth to make direct comparisons between the table of measurements of the primary teeth (Table 3-1) and that of permanent teeth (see Table 1-1).

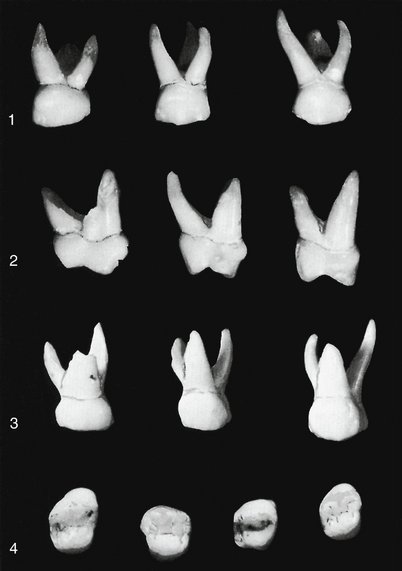

Figure 3-10 Primary maxillary central incisors (first incisors). 1, Labial aspect. Note the lack of character in the mold form; also note the mesiodistal width compared with the shorter crown length. A little of the crown length was lost through abrasion before the date of extraction. 2, Mesial aspect. The cervical ridges are quite prominent labially and lingually, with the bulge much greater than that found on permanent incisors. This characteristic is common to each primary tooth to a varied degree. Normally, these curvatures are covered by gingival tissue with epithelial attachment (see Chapter 5). 3, Incisal aspect.

Lingual Aspect

The lingual aspect of the crown shows well-developed marginal ridges and a highly developed cingulum (Figure 3-12, A). The cingulum extends up toward the incisal ridge far enough to make a partial division of the concavity on the lingual surface below the incisal edge, practically dividing it into a mesial and distal fossa.

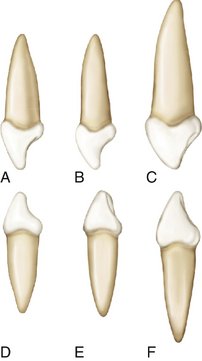

Figure 3-12 Primary right anterior teeth, lingual aspect. A, Maxillary central incisor. B, Maxillary lateral incisor. C, Maxillary canine. D, Mandibular central incisor. E, Mandibular lateral incisor. F, Mandibular canine.

The root narrows lingually and presents a ridge for its full length in comparison with a flatter surface labially. A cross section through the root where it joins the crown shows an outline that is somewhat triangular in shape, with the labial surface making one side of the triangle and mesial and distal surfaces making up the other two sides.

Mesial and Distal Aspects

The mesial and distal aspects of the primary maxillary central incisors are similar (Figure 3-13, A; see also Figure 3-10). The measurement of the crown at the cervical third shows the crown from this aspect to be wide in relation to its total length. The average measurement is only about 1 mm less than the entire crown length cervicoincisally. Because of the short crown and its labiolingual measurement, the crown appears thick at the middle third and even down toward the incisal third. The curvature of the cervical line, which represents the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), is distinct, curving toward the incisal ridge. However, the curvature is not as great as that found on its permanent successor. The cervical curvature distally is less than the curvature mesially, a design that compares favorably with the permanent central incisor.

Figure 3-13 Primary right anterior teeth, mesial aspect. A, Maxillary central incisor. B, Maxillary lateral incisor. C, Maxillary canine. D, Mandibular central incisor. E, Mandibular lateral incisor. F, Mandibular canine.

Although the root appears more blunt from this aspect than it did from the labial and lingual aspects, it is still of an even taper and the shape of a long cone. However, it is blunt at the apex. Usually the mesial surface of the root will have a developmental groove or concavity, whereas distally, the surface is generally convex.

Note the development of the cervical ridges of enamel at the cervical third of the crown labially and lingually.

Incisal Aspect

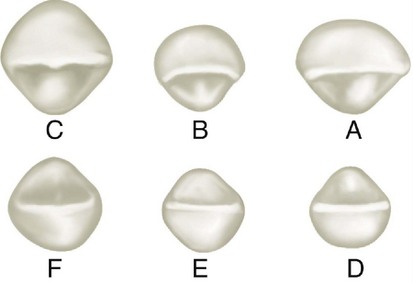

An important feature to note from the incisal aspect is the measurement mesiodistally compared with the measurement labiolingually (Figure 3-14, A; see also Figure 3-10, 3). The incisal edge is centered over the main bulk of the crown and is relatively straight. Looking down on the incisal edge, the labial surface is much broader and also smoother than the lingual surface. The lingual surface tapers toward the cingulum.

Figure 3-14 Primary right anterior teeth, incisal aspect. A, Maxillary central incisor. B, Maxillary lateral incisor. C, Maxillary canine. D, Mandibular central incisor. E, Mandibular lateral incisor. F, Mandibular canine.

The mesial and the distal surfaces of this tooth are relatively broad. The mesial and distal surfaces toward the incisal ridge or at the incisal third are generous enough to make good contact areas with the adjoining teeth, although this facility is used for a short period only because of rapid changes that take place in the jaws of children.

MAXILLARY LATERAL INCISOR

In general, the maxillary lateral is similar to the central incisor from all aspects, but its dimensions differ (Figure 3-15; see also Figures 3-11, B; 3-12, B; 3-13, B; and 3-14, B). Its crown is smaller in all directions. The cervicoincisal length of the lateral crown is greater than its mesiodistal width. The distoincisal angles of the crown are more rounded than those of the central incisor. Although the root has a similar shape, it is much longer in proportion to its crown than the central ratio indicates when a comparison is made.

MAXILLARY CANINE

Labial Aspect

Except for the root form, the labial aspect of the maxillary canine does not resemble either the central or the lateral incisor (Figure 3-16; see also Figure 3-11, C). The crown is more constricted at the cervix in relation to its mesiodistal width, and the mesial and distal surfaces are more convex. Instead of an incisal edge that is relatively straight, it has a long, well-developed, sharp cusp.

Compared with that of the permanent maxillary canine, the cusp on the primary canine is much longer and sharper, and the crest of contour mesially is not as far down toward the incisal portion. A line drawn through the contact areas of the deciduous canine would bisect a line drawn from the cervix to the tip of the cusp. In the permanent canine, the contact areas are not at the same level. When the cusp is intact, the mesial slope of the cusp is longer than the distal slope. The root of the primary canine is long, slender, and tapering and is more than twice the crown length.

Lingual Aspect

The lingual aspect shows pronounced enamel ridges that merge with each other (see Figure 3-12, C). They are the cingulum, mesial and distal marginal ridges, and incisal cusp ridges, besides a tubercle at the cusp tip, which is a continuation of the lingual ridge connecting the cingulum and the cusp tip. This lingual ridge divides the lingual surface into shallow mesiolingual and distolingual fossae.

The root of this tooth tapers lingually. It is usually inclined distally also above the middle third (see Figures 3-11, C and 3-13, C).

Mesial Aspect

From the mesial aspect, the outline form is similar to that of the lateral and central incisors (see Figures 3-13, C and 3-16, 2). However, a difference in proportion is evident. The measurement labiolingually at the cervical third is much greater. This increase in crown dimension, in conjunction with the root width and length, permits resistance against forces the tooth must withstand during function. The function of this tooth is to punch, tear, and apprehend food material.

Distal Aspect

The distal outline of this tooth is the reverse of the mesial aspect. No outstanding differences may be noted except that the curvature of the cervical line toward the cusp ridge is less than on the mesial surface.

Incisal Aspect

From the incisal aspect, we observe that the crown is essentially diamond-shaped (see Figures 3-14, C and 3-16, 3). The angles that are found at the contact areas mesially and distally; the cingulum on the lingual surface; and the cervical third, or enamel ridge, on the labial surface are more pronounced and less rounded in effect than those found on the permanent canines. The tip of the cusp is distal to the center of the crown, and the mesial cusp slope is longer than the distal cusp slope. This allows for intercuspation with the lower, or mandibular, canine, which has its longest slope distally (see Figure 3-11).

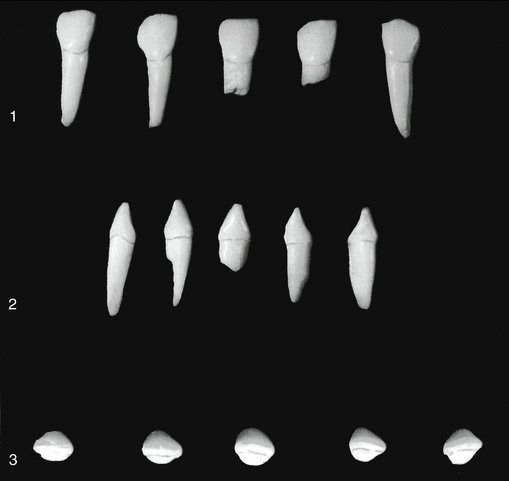

MANDIBULAR CENTRAL INCISOR

Labial Aspect

The labial aspect of this crown has a flat face with no developmental grooves (Figure 3-17; see Figure 3-11, D). The mesial and distal sides of the crown are tapered evenly from the contact areas, with the measurement being less at the cervix. This crown is wide in proportion to its length in comparison with that of its permanent successor. The heavy look at the root trunk makes this small tooth resemble the permanent maxillary lateral incisor.

Figure 3-17 Primary mandibular central incisors. 1, Labial aspect. 2, Mesial aspect. 3, Incisal aspect.

The root of the primary central incisor is long and evenly tapered down to the apex, which is pointed. The root is almost twice the length of the crown (see Figure 3-11, D).

Lingual Aspect

On the lingual surface of the crown, the marginal ridges and the cingulum may be located easily (see Figure 3-12, D). The lingual surface of the crown at the middle third and the incisal third may have a flattened surface level with the marginal ridges, or it may present a slight concavity, called the lingual fossa. The lingual portion of the crown and root converges so that it is more narrow toward the lingual and not the labial surface.

Mesial Aspect

The mesial aspect shows the typical outline of an incisor tooth, even though the measurements are small (see Figures 3-13, D and ">3-17, 2). The incisal ridge is centered over the center of the root and between the crest of curvature of the crown, labially, and lingually. The convexity of the cervical contours labially and lingually at the cervical third is just as pronounced as in any of the other primary incisors and more pronounced by far than the prominences found at the same locations on a permanent mandibular central incisor. As mentioned before, these cervical bulges are important.

Although this tooth is small, its labiolingual measurement is only about a millimeter less than that of the primary maxillary central incisor. The primary incisors seem to be built for strenuous service.

The mesial surface of the root is nearly flat and evenly tapered; the apex presents a more blunt appearance than is found with the lingual or labial aspects.

Distal Aspect

The outline of this tooth from the distal aspect is the reverse of that found from the mesial aspect. Little difference can be noted between these aspects, except that the cervical line of the crown is less curved toward the incisal ridge than on the mesial surface. Often, a developmental depression is evident on the distal side of the root.

Incisal Aspect

The incisal ridge is straight and bisects the crown labiolingually. The outline of the crown from the incisal aspect emphasizes the crests of contour at the cervical third labially and lingually (see Figures 3-14, D and 3-17, 3). A definite taper is evident toward the cingulum on the lingual side.

The labial surface from this view presents a flat surface that is slightly convex, whereas the lingual surface presents a flattened surface that is slightly concave.

MANDIBULAR LATERAL INCISOR

The fundamental outlines of the primary mandibular lateral incisor (Figure 3-18) are similar to those of the primary central incisor. These two teeth supplement each other in function. The lateral incisor is somewhat larger in all measurements except labiolingually, where the two teeth are practically identical. The cingulum of the lateral incisor may be a little more generous than that of the central incisor. The lingual surface of the crown between the marginal ridges may be more concave. In addition, a tendency exists for the incisal ridge to slope downward distally. This design lowers the distal contact area apically, so that proper contact may be made with the mesial surface of the primary mandibular canine (see Figures 3-11, E; 3-12, E; 3-13, E; and 3-14, E).

MANDIBULAR CANINE

Little difference in functional form is evident between the mandibular canine and the maxillary canine. The difference is mainly in the dimensions. The crown is perhaps 0.5 mm shorter, and the root is at least 2 mm shorter; the mesiodistal measurement of the mandibular canine at the root trunk is greater when compared with its mesiodistal measurement at the contact areas than is that of the maxillary canine (Figure 3-19). It is “thicker” accordingly at the “neck” of the tooth. The outstanding variation in size between the two deciduous canines is shown by the labiolingual calibration. The deciduous maxillary canine is much larger labiolingually (see Figure 3-13).

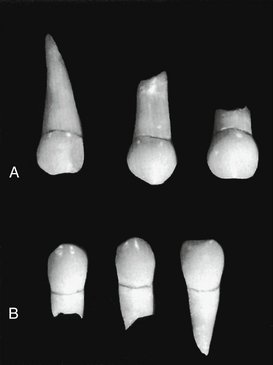

Figure 3-19 A comparison of primary canines, both in the size and shape of the crowns. Two of them have their roots intact and show no dissolution. A, Maxillary canines. B, Mandibular canines. Compare Figures 3-16 and 3-20.

The cervical ridges labially and lingually are not quite as pronounced as those found on the maxillary canine. The greatest variation in outline form when one compares the two teeth is seen from the labial and lingual aspects; the distal cusp slope is longer than the mesial slope. The opposite arrangement is true of the maxillary canine. This makes for proper intercuspation of these teeth during mastication.

Figure 3-20 illustrates the primary mandibular canines (see also Figures 3-11, F; 3-12, F; 3-13, F; and 3-14, F).

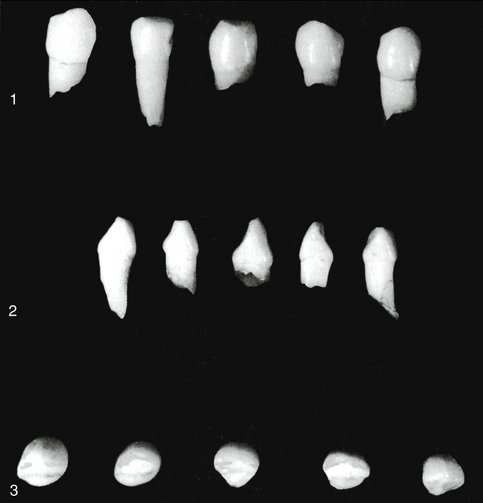

MAXILLARY FIRST MOLAR

Buccal Aspect

The widest measurement of the crown of the maxillary first molar is at the contact areas mesially and distally (Figure 3-21, A). From these points, the crown converges toward the cervix, with the measurement at the cervix being fully 2 mm less than the measurement at the contact areas. This dimensional arrangement furnishes a narrower look to the cervical portion of the crown and root of the primary maxillary first molar than that of the same portion of the permanent maxillary first molar. The occlusal line is slightly scalloped but with no definite cusp form. The buccal surface is smooth, and little evidence of developmental grooves is noted. It is from this aspect that one may judge the relative size of the primary maxillary first molar when it is compared with the second molar. It is much smaller in all measurements than the second molar. Its relative shape and size suggest that it was designed to be the “premolar section” of the primary dentition. In function it acts as a compromise between the size and shape of the anterior primary teeth and the molar area, this area being held temporarily by the larger primary second molar. At age 6, the large first permanent molar is expected to take its place distal to the second primary molar, which will complete a more extensive molar area for masticating efficiency.

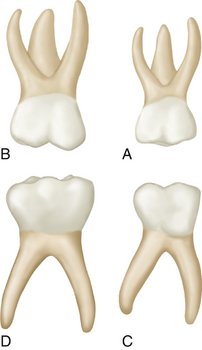

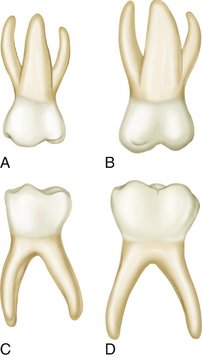

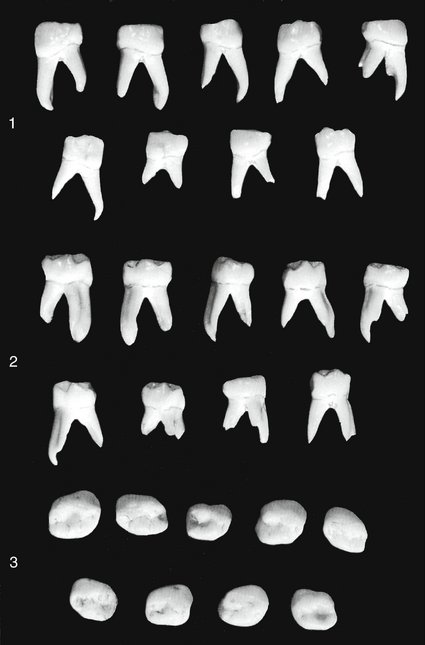

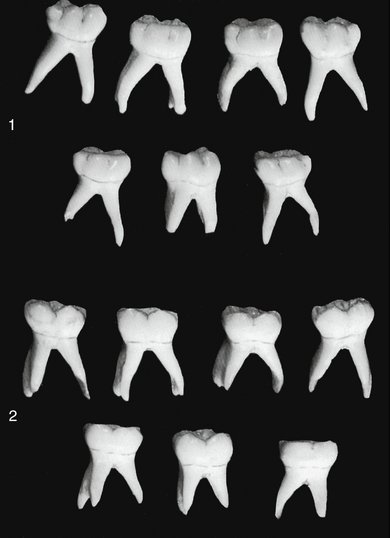

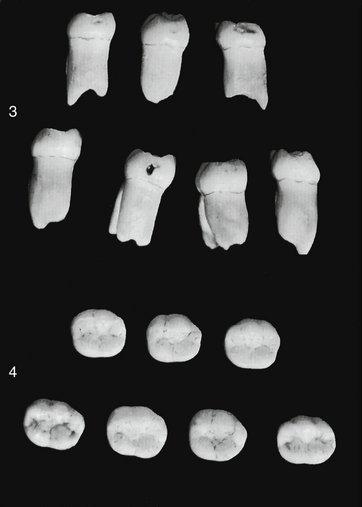

Figure 3-21 Primary right molars, buccal aspect. A, Maxillary first molar. B, Maxillary second molar. C, Mandibular first molar. D, Mandibular second molar.

The roots of the maxillary first molar are slender and long, and they spread widely. All three roots may be seen from this aspect. The distal root is considerably shorter than the mesial one. The bifurcation of the roots begins almost immediately at the site of the cervical line (CEJ). Actually, this arrangement is in effect for the entire root trunk, which includes a trifurcation, and this is a characteristic of all primary molars, whether maxillary or mandibular. Permanent molars do not possess this characteristic. The root trunk on permanent molars is much heavier, with a greater distance between the cervical lines to the points of bifurcations (see Figure 11-8).

Lingual Aspect

The general outline of the lingual aspect of the crown is similar to that of the buccal aspect (Figure 3-22, A). The crown converges considerably in a lingual direction, which makes the lingual portion calibrate less mesiodistally than the buccal portion.

Figure 3-22 Primary right molars, lingual aspect. A, Maxillary first molar. B, Maxillary second molar. C, Mandibular first molar. D, Mandibular second molar.

The mesiolingual cusp is the most prominent cusp on this tooth. It is the longest and sharpest cusp. The distolingual cusp is poorly defined; it is small and rounded when it exists at all. From the lingual aspect, the distobuccal cusp may be seen, since it is longer and better developed than the distolingual cusp. A type of primary maxillary first molar that is not uncommon and presents as one large lingual cusp with no developmental groove in evidence lingually is a three-cusped molar (see Figure 3-25, 4, second from left).

All three roots also may be seen from this aspect. The lingual root is larger than the others.

Mesial Aspect

From the mesial aspect, the dimension at the cervical third is greater than the dimension at the occlusal third (Figure 3-23, A). This is true of all molar forms, but it is more pronounced on primary than on permanent teeth. The mesiolingual cusp is longer and sharper than the mesiobuccal cusp. A pronounced convexity is evident on the buccal outline of the cervical third. This convexity is an outstanding characteristic of this tooth. It actually gives the impression of overdevelopment in this area when comparisons are made with any other tooth, primary or permanent, with the mandibular first primary molar being a close contender. The cervical line mesially shows some curvature in the direction of the occlusal surface.

Figure 3-23 Primary right molars, mesial aspect. A, Maxillary first molar. B, Maxillary second molar. C, Mandibular first molar. D, Mandibular second molar.

The mesiobuccal and lingual roots are visible only when looking at the mesial side of this tooth from a point directly opposite the contact area. The distobuccal root is hidden behind the mesiobuccal root. The lingual root from this aspect looks long and slender and extends lingually to a marked degree. It curves sharply in a buccal direction above the middle third.

Distal Aspect

From the distal aspect, the crown is narrower distally than mesially; it tapers markedly toward the distal end (Figure 3-24, A). The distobuccal cusp is long and sharp, and the distolingual cusp is poorly developed. The prominent bulge seen from the mesial aspect at the cervical third does not continue distally. The cervical line may curve occlusally, or it may extend straight across from the buccal surface to the lingual surface. All three roots may be seen from this angle, but the distobuccal root is superimposed on the mesiobuccal root so that only the buccal surface and the apex of the latter may be seen. The point of bifurcation of the distobuccal root and the lingual root is near the CEJ and, as described earlier, is typical.

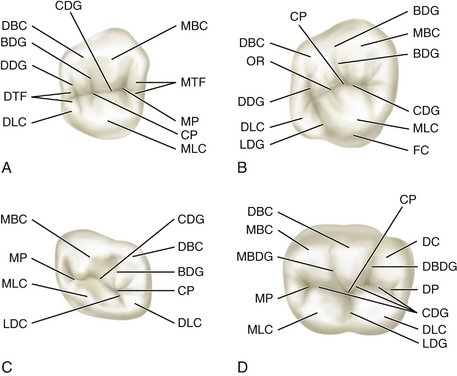

Figure 3-24 A, Maxillary first molar. MBC, Mesiobuccal cusp; MTF, mesial triangular fossa; MP, mesial pit; CP, central pit; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; DLC, distolingual cusp; DTF, distal triangular fossa; DDG, distal developmental groove; BDG, buccal developmental groove; DBC, distobuccal cusp; CDG, central developmental groove. B, Maxillary second molar. BDG, Buccal developmental groove; MBC, mesiobuccal cusp; CDG, central developmental groove; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; FC, fifth cusp; LDG, lingual developmental groove; DLC, distolingual cusp; DDG, distal developmental groove; OR, oblique ridge; DBC, distobuccal cusp; CP, central pit. C, Mandibular first molar. CDG, Central developmental groove; DBC, distobuccal cusp; BDG, buccal developmental groove; CP, central pit; DLC, distolingual cusp; LDC, lingual developmental groove; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; MP, mesial pit; MBC, mesiobuccal cusp. D, Mandibular second molar. DBC, Distobuccal cusp; CP, central pit; DC, distal cusp; DBDG, distobuccal developmental groove; DP, distal pit; CDG, central developmental groove; DLC, distolingual cusp; LDG, lingual developmental groove; MLC, mesiolingual cusp; MP, mesial pit; MBDG, mesiobuccal developmental groove; MBC, mesiobuccal cusp.

Occlusal Aspect

The calibration of the distance between the mesiobuccal line angle and the distobuccal line angle is definitely greater than the calibration between the mesiolingual line angle and the distolingual line angle (see Figure 3-24, A). Therefore the crown outline converges lingually. Also, the calibration from the mesiobuccal line angle to the mesiolingual line angle is definitely greater than that found at the distal line angles. Therefore the crown also converges distally. Nevertheless, these convergences are not reflected entirely in the working occlusal surface because it is more nearly rectangular, with the shortest sides of the rectangle represented by the marginal ridges. The occlusal surface has a central fossa. A mesial triangular fossa is just inside the mesial marginal ridge, with a mesial pit in this fossa and a sulcus with its central groove connecting the two fossae. A well-defined buccal developmental groove divides the mesiobuccal cusp and the distobuccal cusp occlusally. Supplemental grooves radiate from the pit in the mesial triangular fossa as follows: one buccally, one lingually, and one toward the marginal ridge, with the last sometimes extending over the marginal ridge mesially.

Sometimes the primary maxillary first molar has a well-defined triangular ridge connecting the mesiolingual cusp with the distobuccal cusp. When well developed, it is called the oblique ridge. In some of these teeth, the ridge is indefinite, and the central developmental groove extends from the mesial pit to the distal developmental groove. This disto-occlusal groove is always seen and may or may not extend through to the lingual surface, outlining a distolingual cusp. The distal marginal ridge is thin and poorly developed in comparison with the mesial marginal ridge.

Summary of the occlusal aspect of the maxillary first primary molar

The form of the maxillary first primary molar varies from that of any tooth in the permanent dentition. Although no premolars are in the primary set, in some respects the crown of this primary molar resembles a permanent maxillary premolar. Nevertheless, the divisions of the occlusal surface and the root form with its efficient anchorage make it a molar, both in type and function. Figure 3-25 presents all the aspects of the primary maxillary first molars.

Figure 3-25 Primary maxillary first molars. 1, Buccal aspect. Note the flare of roots. 2, Mesial aspect. The cervical ridge on the buccal surface is curved to the extreme. Also note the flat or concave buccal surface above this bulge as it approaches the occlusal surface. 3, Lingual aspect. 4, Occlusal aspect. This aspect emphasizes the extensive width of the mesial portion of primary first molars. The four specimens show size differentials even in deciduous teeth (see Figure 3-24).

MAXILLARY SECOND MOLAR

Buccal Aspect

The primary maxillary second molar has characteristics resembling those of the permanent maxillary first molar, but it is smaller (see Figure 3-21, B). The buccal view of this tooth shows two well-defined buccal cusps with a buccal developmental groove between them (Figure 3-26, 1). In line with all primary molars, the crown is narrow at the cervix in comparison with its mesiodistal measurement at the contact areas. This crown is much larger than that of the first primary molar. Although from this aspect the roots appear slender, they are much longer and heavier than those that are a part of the maxillary first molar. The point of bifurcation between the buccal roots is close to the cervical line of the crown. The two buccal cusps are more nearly equal in size and development than those of the primary maxillary first molar.

Lingual Aspect

Lingually, the crown shows the following three cusps: (1) the mesiolingual cusp, which is large and well developed; (2) the distolingual cusp, which is well developed (more so than that of the primary first molar); and (3) a third supplemental cusp, which is apical to the mesiolingual cusp and sometimes called the tubercle of Carabelli, or the fifth cusp (see Figure 3-22, B). This cusp is poorly developed and merely acts as a buttress or supplement to the bulk of the mesiolingual cusp. If the tubercle of Carabelli seems to be missing, some traces of developmental lines or “dimples” remain (see Figure 3-26, 3). A well-defined developmental groove separates the mesiolingual cusp from the distolingual cusp and connects with the developmental groove, which outlines the fifth cusp.

All three roots are visible from this aspect; the lingual root is large and thick in comparison with the other two roots. It is approximately the same length as the mesiobuccal root. If it should differ, it will be on the short side.

Mesial Aspect

From the mesial aspect, the crown has a typical molar outline that resembles that of the permanent molars very much (see Figures 3-23, B and 3-26, 2). The crown appears short because of its width buccolingually in comparison with its length. The crown of this tooth is usually only about 0.5 mm longer than the crown of the first deciduous molar, but the buccolingual measurement is 1.5 to 2 mm greater. In addition, the roots are 1.5 to 2 mm longer. The mesiolingual cusp of the crown with its supplementary fifth cusp appears large in comparison with the mesiobuccal cusp. The mesiobuccal cusp from this angle is relatively short and sharp. Little curvature to the cervical line is evident. Usually, it is almost straight across from buccal surface to lingual surface.

The mesiobuccal root from this aspect is broad and flat. The lingual root has somewhat the same curvature as the lingual root of the maxillary first deciduous molar.

The mesiobuccal root extends lingually far out beyond the crown outline. The point of bifurcation between the mesiobuccal root and the lingual root is 2 or 3 mm apical to the cervical line of the crown; this differs in depth on the root trunk from comparisons of this area in the recent discussion of primary molars. The mesiobuccal root presents itself as being quite wide from the mesial aspect. It measures approximately two thirds the width of the root trunk, which leaves one third for the lingual root. The mesiolingual cusp is directly below their bifurcation. Although from this aspect the curvature is strong lingually at the cervical portion, as on most deciduous teeth the crest of curvature buccally at the cervical third is nominal and resembles the curvature found at this point on the permanent maxillary first molar. In this, it differs entirely from the prominent curvature found on the primary maxillary first molars at the cervical third buccally.

Distal Aspect

From the distal aspect, it is apparent that the distal calibration of the crown is less than the mesial measurement, but the variation is found on the crown of the deciduous maxillary first molar. From both the distal and the mesial aspects, the outline of the crown lingually creates a smooth, rounded line, whereas a line describing the buccal surface is almost straight from the crest of curvature to the tip of the buccal cusp. The distobuccal cusp and the distolingual cusp are about the same in length. The cervical line is approximately straight, as was found mesially.

All three roots are seen from this aspect, although only a part of the outline of the mesiobuccal root may be seen, since the distobuccal root is superimposed over it. The distobuccal root is shorter and narrower than the other roots. The point of bifurcation between the distobuccal root and the lingual root is more apical in location than any of the other points of bifurcation. The point of bifurcation between these two roots on the distal is more nearly centered above the crown than that on the mesial between the mesiobuccal and lingual roots.

Occlusal Aspect

From the occlusal aspect, this tooth resembles the permanent first molar (see Figures 3-24 and 3-26, 3). It is somewhat rhomboidal and has four well-developed cusps and one supplemental cusp: mesiobuccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, distolingual, and fifth cusps. The buccal surface is rather flat with the developmental groove between the cusps less marked than that found on the first permanent molar. Developmental grooves, pits, oblique ridge, and others are almost identical. The character of the “mold” is constant.

The occlusal surface has a central fossa with a central pit, a well-defined mesial triangular fossa, just distal to the mesial marginal ridge, with a mesial pit at its center. A well-defined developmental groove called the central groove is also at the bottom of a sulcus, connecting the mesial triangular fossa with the central fossa. The buccal developmental groove extends buccally from the central pit, separating the triangular ridges, which are occlusal continuations of the mesiobuccal and distobuccal cusps. Supplemental grooves often radiate from these developmental grooves.

The oblique ridge is prominent and connects the mesiolingual cusp with the distobuccal cusp. Distal to the oblique ridge, the distal fossa is found, which harbors the distal developmental groove. The distal groove has branches of supplemental grooves within the distal triangular fossa, which is rather indefinitely outlined just mesial to the distal marginal ridge.

The distal groove acts as a line of demarcation between the mesiolingual and distolingual cusps and continues on to the lingual surface as the lingual developmental groove. The distal marginal ridge is as well developed as the mesial marginal ridge. It will be remembered that the marginal ridges are not developed equally on the primary maxillary first molar.

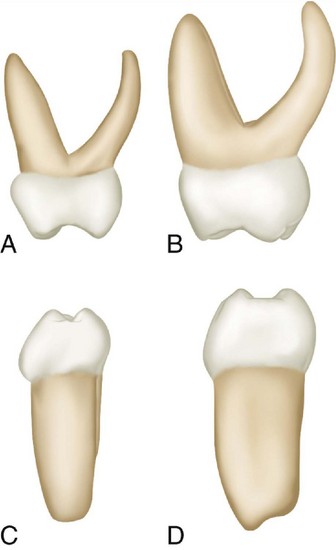

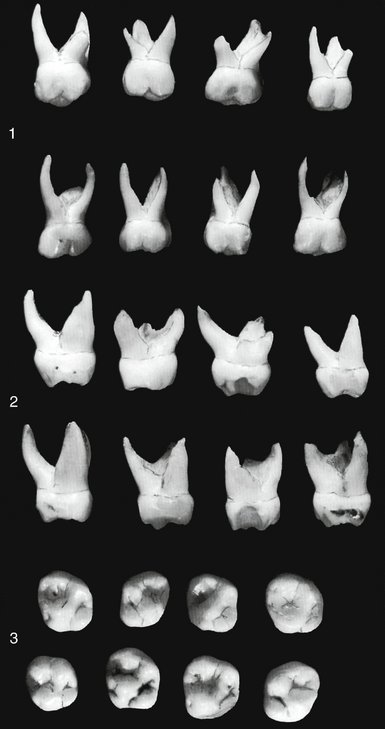

MANDIBULAR FIRST MOLAR

The mandibular first molar does not resemble any of the other teeth, deciduous or permanent. Because it varies so much from all others, it appears strange and primitive (Figure 3-27).

Figure 3-27 Primary mandibular first molars. This tooth has characteristics unlike those of any other tooth in the mouth, primary or permanent. 1, Buccal aspect. 2, Lingual aspect. 3, Occlusal aspect.

Buccal Aspect

From the buccal aspect, the mesial outline of the crown of the primary mandibular first molar is almost straight from the contact area to the cervix, constricting the crown very little at the cervix (Figure 3-28, A). The outline describing the distal portion, however, converges toward the cervix more than usual, so that the contact area extends distally to a marked degree (see Figures 3-21, C and 3-27, 1).

Figure 3-28 Three rare specimens of the primary mandibular first molars. A, Buccal aspect. B, Mesial aspect. These three specimens have their roots intact with little or no resorption showing. They enable the viewer to observe the actual shape and size of the mesial and distal roots. The mesial root is broad, curved, and long, with fluting down the center. This makes for tremendous anchorage. The distal root is much shorter, but it is heavy and also curved. It does its share in bracing the crown, being in partnership with the mesial root during the process.

The distal portion of the crown is shorter than the mesial portion, with the cervical line dipping apically where it joins the mesial root.

The two buccal cusps are rather distinct, although no developmental groove is evident between them. The mesial cusp is larger than the distal cusp. A developmental depression dividing them (not a groove) extends over to the buccal surface.

The roots are long and slender, and they spread greatly at the apical third beyond the outline of the crown.

The buccal aspect emphasizes the strange, primitive look of this tooth. The primary first mandibular molar from this angle impresses one with the thought of the possibility that at some time in the dim past, a fusion of two teeth ended in a strange single combination. That thought seems particularly apropos when a well-formed specimen of the tooth in question is located—one with its roots intact, showing no evidences of decalcification.

From the buccal aspect, if a line is drawn from the bifurcation of the roots to the occlusal surface, the tooth will be evenly divided mesiodistally. However, the mesial portion represents a tooth with a crown almost twice as tall as the distal half, and the root is again a third as long as the distal one. Two complete teeth are represented, but their dimensions differ considerably (see Figures 3-21, C and 3-27, 1).

Lingual Aspect

The crown and root converge lingually to a marked degree on the mesial surface (see Figures 3-22, C and 3-27, 2). Distally, the opposite arrangement is true of both crown and root. The distolingual cusp is rounded and suggests a developmental groove between this cusp and the mesiolingual cusp. The mesiolingual cusp is long and sharp at the tip, more so than any of the other cusps. The sharp and prominent mesiolingual cusp (almost centered lingually but in line with the mesial root) is an outstanding characteristic found occlusally on the primary first mandibular molar. It is noted that the mesial marginal ridge is so well developed that it might almost be considered another small cusp lingually. Part of the two buccal cusps may be seen from this angle.

From the lingual aspect, the crown length mesially and distally is more uniform than it is from the buccal aspect. The cervical line is straighter.

Mesial Aspect

The most noticeable detail from the mesial aspect is the extreme curvature buccally at the cervical third (see Figure 3-28, B). Except for this detail, the crown outline of this tooth from this aspect resembles the mesial aspect of the primary second molar and that aspect of the permanent mandibular molars. In this comparison, the buccal cusps are placed over the root base, and the lingual outline of the crown extends out lingually beyond the confines of the root base.

Both the mesiobuccal cusp and the mesiolingual cusp are in view from this aspect, as is the well-developed mesial marginal ridge. Because the mesiobuccal crown length is greater than the mesiolingual crown length, the cervical line slants upward buccolingually. Note the flat appearance of the buccal outline of the crown from the crest of curvature of the buccal surface at the cervical third to the tip of the mesiobuccal cusp. All of the primary molars have flattened buccal surfaces above this cervical ridge.

The outline of the mesial root from the mesial aspect does not resemble the outline of any other primary tooth root. The buccal and lingual outlines of the root drop straight down from the crown and are approximately parallel for more than half their length, tapering only slightly at the apical third. The root end is flat and almost square. A developmental depression usually extends almost the full length of the root on the mesial side.

Distal Aspect

The distal aspect of the mandibular first molar differs from the mesial aspect in several ways. The cervical line does not drop buccally. The length of crown buccally and lingually is more uniform, and the cervical line extends almost straight across buccolingually. The distobuccal cusp and the distolingual cusp are not as long or as sharp as the two mesial cusps. The distal marginal ridge is not as straight and well defined as the mesial marginal ridge. The distal root is rounder and shorter and tapers more apically.

Occlusal Aspect

The general outline of this tooth from the occlusal aspect is rhomboidal (see Figure 3-27, 3). The prominence present mesiobuccally is noticeable from this aspect, which accents the mesiobuccal line angle of the crown in comparison with the distobuccal line angle and thereby emphasizes the rhomboidal form.

The mesiolingual cusp may be seen as the largest and best developed of all the cusps, and it has a broad, flattened surface lingually. The buccal developmental groove of the occlusal surface divides the two buccal cusps evenly. This developmental groove is short, extending from between the buccal cusp ridges to a point approximately in the center of the crown outline at a central pit. The central developmental groove joins it at this point and extends mesially, separating the mesiobuccal cusp and the mesiolingual cusp. The central groove ends in a mesial pit in the mesial triangular fossa, which is immediately distal to the mesial marginal ridge. Two supplemental grooves join the developmental groove in the center of the mesial triangular fossa; one supplemental groove extends buccally and the other extends lingually.

The mesiobuccal cusp exhibits a well-defined triangular ridge on the occlusal surface, which terminates in the center of the occlusal surface buccolingually at the central developmental groove. The lingual developmental groove extends lingually from this point, separating the mesiolingual cusp and the distolingual cusp. Usually, the lingual developmental groove does not extend through to the lingual surface but stops at the junction of lingual cusp ridges. Some supplemental grooves immediately mesial to the distal marginal ridge in the distal triangular fossa join with the central developmental groove.

MANDIBULAR SECOND MOLAR

The primary mandibular second molar has characteristics that resemble those of the permanent mandibular first molar, although its dimensions differ (Figure 3-29).

Figure 3-29 Primary mandibular second molars. 1, Buccal aspect. 2, Lingual aspect. 3, Mesial aspect. 4, Occlusal aspect.

Buccal Aspect

From the buccal aspect, the primary mandibular second molar has a narrow mesiodistal calibration at the cervical portion of the crown compared with the calibration mesiodistally on the crown at contact level. The mandibular first permanent molar, accordingly, is wider at the cervical portion (see Figures 3-21, D and 3-29, 1).

From this aspect also, mesiobuccal and distobuccal developmental grooves divide the buccal surface of the crown occlusally into three cuspal portions almost equal in size. This arrangement forms a straight buccal surface presenting a mesiobuccal, a buccal, and a distobuccal cusp. It differs, therefore, from the mandibular first permanent molar, which has an uneven distribution buccally, presenting two buccal cusps and one distal cusp.

The roots of the primary second molar from this angle are slender and long. They have a characteristic flare mesiodistally at the middle and apical thirds. The roots of this tooth may be twice as long as the crown.

The point of bifurcation of the roots starts immediately below the CEJ of crown and root.

Lingual Aspect

From the lingual aspect, two cusps of almost equal dimensions can be observed (see Figures 3-22, D and 3-29, 2). A short, lingual groove is between them. The two lingual cusps are not quite as wide as the three buccal cusps; this arrangement narrows the crown lingually. The cervical line is relatively straight, and the crown extends out over the root more distally than it does mesially. The mesial portion of the crown seems to be a little higher than the distal portion of the crown when viewed from the lingual aspect. It gives the impression of being tipped distally. A portion of each of the three buccal cusps may be seen from this aspect.

The roots from this aspect give somewhat the same appearance as from the buccal aspect. Note the length of the roots.

Mesial Aspect

From the mesial aspect, the outline of the crown resembles that of the permanent mandibular first molar (see Figures 3-23, D and 3-29, 3). The crest of contour buccally is more prominent on the primary molar, and the tooth seems to be more constricted occlusally because of the flattened buccal surface above this cervical ridge.

The crown is poised over the root of this tooth in the same manner as all mandibular posteriors; its buccal cusp is over the root and the lingual outline of the crown extending out beyond the root line. The marginal ridge is high, a characteristic that makes the mesiobuccal cusp and the mesiolingual cusp appear rather short. The lingual cusp is longer, or higher, than the buccal cusp. The cervical line is regular, although it extends upward buccolingually, making up for the difference in length between the buccal and lingual cusps.

The mesial root is unusually broad and flat with a blunt apex that is sometimes serrated.

Distal Aspect

The crown is not as wide distally as it is mesially; therefore it is possible to see the mesiobuccal and distobuccal cusps from the distal aspect. The distolingual cusp appears well developed, and the triangular ridge from the tip of this cusp extending down into the occlusal surface is seen over the distal marginal ridge.

The distal marginal ridge dips down more sharply and is shorter buccolingually than the mesial marginal ridge. The cervical line of the crown is regular, although it has the same upward incline buccolingually on the distal as on the mesial.

The distal root is almost as broad as the mesial root and is flattened on the distal surface. The distal root tapers more at the apical end than does the mesial root.

Occlusal Aspect

The occlusal aspect of the primary mandibular second molar is somewhat rectangular (see Figures 3-24, D and 3-29, 4). The three buccal cusps are similar in size. The two lingual cusps are also equally matched. However, the total mesiodistal width of the lingual cusps is less than the total mesiodistal width of the three buccal cusps.

Well-defined triangular ridges extend occlusally from each one of these cusp tips. The triangular ridges end in the center of the crown buccolingually in a central developmental groove that follows a staggered course from the mesial triangular fossa, just inside the mesial marginal ridge, to the distal triangular fossa, just mesial to the distal marginal ridge. The distal triangular fossa is not as well defined as the mesial triangular fossa. Developmental grooves branch off from the central groove both buccally and lingually, dividing the cusps. The two buccal grooves are confluent with the buccal developmental grooves of the buccal surface, one mesial and one distal, and the single lingual developmental groove is confluent with the lingual groove on the lingual surface of the crown.

Scattered over the occlusal surface are supplemental grooves on the slopes of triangular ridges and in the mesial and distal triangular fossae. The mesial marginal ridge is better developed and more pronounced than the distal marginal ridge. The outline of the crown converges distally. An outline following the tips of the cusps and the marginal ridges conforms to the outline of a rectangle more closely than does the gross outline of the crown in its entirety.

A comparison occlusally between the deciduous mandibular second molar and the permanent mandibular first molar brings out the following points of difference. In the deciduous molar the mesiobuccal, distobuccal, and distal cusps are almost equal in size and development. The distal cusp of the permanent molar is smaller than the other two. Because of the small buccal cusps, the deciduous tooth crown is narrower buccolingually, in comparison with its mesiodistal measurement, than is the permanent tooth.

1. Fulton JT, Hughes JT, Mercer CV. The life cycle of the human teeth. Chapel Hill, NC: Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina; 1964.

2. McBeath EC. New concept of the development and calcification of the teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1936;23:675.

3. Noyes EB, Shour I, Noyes HJ. Dental histology and embryology, ed 5. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1938.

4. Finn SB. Clinical pedodontics, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1957.

Barker BC. Anatomy of root canals: IV. Deciduous teeth. Aust Dent J. 1975;20:101.

Baume LJ. Physiologic tooth migration and its significance for the development of occlusion. I. The biogenetic course of the deciduous dentition. J Dent Res. 1950;29:123.

Broadbelt AG. On the growth pattern of the human head, from the third month to the eighth year of life. Am J Anat. 1941;68:209.

Carlsen O. Carabelli’s structure on the human maxillary deciduous first molar. Acta Odontol Scand. 1968;26:395.

Carlsen O, Andersen J. On the anatomy of the pulp chamber and root canals in human deciduous teeth. Tandlaegebladet. 1966;70:93.

de Campos Russo M, et al. Observations on the pulpal floor of human deciduous teeth and possible implications in endodontic treatment. Rev Fac Odontol Aracatuba. 1974;3:61.

Fanning EA. Effect of extraction of deciduous molars on the formation and eruption of their successors. Angle Orthod. 1962;32:44.

Friel S. The development of ideal occlusion of the gum pads and the teeth. Am J Orthod. 1954;40:196.

Friel S. Occlusion: observations on its development from infancy to old age. Int J Orthod Oral Surg. 1927;13:322.

Moorrees CFA, Chadha M. Crown diameters of corresponding tooth groups in the deciduous and permanent dentition. J Dent Res. 1962;41:466.

Richardson AS, Castaldi CR. Dental development during the first two years of life. J Can Dent Assoc. 1967;33:418.

Van der Linden FPGM, Duterloo HS. Development of the human dentition: an atlas. Hagerstown, MD: Harper & Row; 1976.

Woo RK, et al. Accessory canals in deciduous molars. J Int Assoc Dent Child. 1981;12:51.

site for additional study resources.

site for additional study resources.