Admitting, Transferring, Discharging and Patients

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Differentiate between routine and emergency admissions.

2 Describe the role of the admitting department.

3 List the elements included in a patient’s orientation to the nursing unit.

4 List five types of information that must be included in the discharge form sent with a patient going to another facility.

5 Delineate the necessary information to include on a patient’s discharge instructions when the patient is going directly home.

6 Explain the procedure for pronouncing and recording the death of a patient.

1 Assist with the performance of an admission assessment.

2 Orient a patient to the patient unit and hospital.

3 Assist with the transfer of a patient to another unit.

4 Interact with the social worker regarding the discharge needs of an assigned patient.

5 Use correct communication techniques to ensure safe handoff of a patient to another nurse, department, or facility.

6 Demonstrate appropriate interaction with the family of a patient who has expired.

autopsy (p. 401)

co-pays (p. 395)

coroner (p. 402)

deductibles (p. 395)

discharge planner (p. 399)

emergency admission (p. 394)

health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (p. 395)

managed care plans (p. 395)

Medicaid (p. 395)

medical social worker (MSW) (p. 401)

Medicare (p. 395)

routine admissions (p. 394)

TYPES OF ADMISSIONS

Each day, thousands of people are admitted to hospitals. This is part of the daily routine for the nurse, but for the patient it is a major event. You must not lose sight of its impact on those admitted for care.

Illness, injury, and the need for surgery are highly stressful, particularly if associated with loss of function, chronic health problems, a change in body appearance, or a terminal diagnosis. The financial impact can be devastating, both because of the cost of care and due to the loss of income. These stresses extend to include the family and often close friends and associates as well.

ROUTINE ADMISSIONS

Routine admissions are those that are scheduled in advance. The physician and patient have agreed to the admission as the most appropriate way to address the medical need, and the patient has had at least a short period of time in which to make plans and arrangements for this interruption in the usual routine (Cultural Cues 23-1).

Many facilities have specific units that provide for day-stay or same-day surgeries. These patients will arrive a couple of hours before the procedure and, after a short recovery period in the day-stay unit, go home the same day. Although considered outpatients, day-stay patients must still meet the same admission criteria as routine admissions. If their condition is such that they cannot go home the same day, they are usually admitted to an inpatient nursing unit because most day-stay units do not remain open at night.

EMERGENCY ADMISSIONS

An emergency admission is one for which there was no prior planning. These occur when sudden illness, injury, or abrupt worsening of an existing condition requires immediate admission for treatment. Such admissions tend to be particularly stressful for both the patient and close family and friends. In addition to worry and fear about the medical problem, there may be prior commitments that now cannot be met or children who need care. These concerns can have a direct effect on the patient’s response to treatment.

THE ADMISSION PROCESS

Preadmission Procedures and Requirements

Routine admissions normally take place the day of the scheduled procedure. For this reason, most facilities require that the patient come in a day or two before admission to complete the administrative paperwork and have any admitting laboratory work or other studies completed.

Insurance companies and health care regulatory organizations mandate that specific criteria be met when an individual is admitted to the hospital. For routine admissions, these are completed in advance. However, in an emergency situation, they take place as the patient is being stabilized in the emergency department and prepared for admission. These are discussed below.

Authorization for Admission

Most third-party payers require prior authorization for hospital admission. There are a variety of third-party payers, including private or employer-provided coverage through major insurance companies, managed care plans (health care plans in which all medical care except emergency care is managed and must be preauthorized by the insuring group), and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (organizations that provide most outpatient care at organization clinics, may provide inpatient care at organization hospitals, and must authorize usage of outside services). Government plans include Medicaid (state medical care coverage for low-income individuals and families), Medicare (medical care coverage provided through the Social Security Administration primarily for people age 65 and over), and TRICARE, previously called CHAMPUS (coverage in civilian facilities for military staff, family, and retirees).

In most cases it is the responsibility of the physician’s office to obtain this authorization. If authorization is denied, it means that the patient’s insurance carrier has refused to accept liability for payment. All payment programs and plans have criteria that define the services covered. For example, most plans do not cover procedures that are regarded as purely cosmetic, such as a face lift or breast augmentation, but these same plans may cover cosmetic procedures if they are to repair the effects of an injury or a necessary surgical procedure such as a mastectomy.

Admitting Department Function

The admitting department is responsible for making sure that all admission criteria are met. They collect the personal and insurance information and verify the authorization for admission. In many facilities, the admitting department is part of the business office and responsible for making payment arrangements on insurance deductibles and co-pays (the amounts the insurance carrier may require the patient to pay for care). They may also collect deposits and make payment arrangements for noncovered services.

For an emergency admission, this process may become the responsibility of the emergency department clerical staff.

DAY OF ADMISSION

Patients are usually required to report to the hospital 1 or 2 hours before the scheduled procedure. For early procedures, this often means that they arrive near the end of the night shift rather than on the day shift. Day-stay units typically begin the day shift early, at 5 or 6 A.M., to accommodate the early arrivals.

Patient Orientation to Nursing Unit

Newly admitted patients, particularly those who have never been hospitalized before, may be nervous and very unsure of what to expect. You can do a great deal to alleviate their anxiety during the initial contact by orienting them to the nursing unit.

You should smile, make eye contact, and call the patient by name. A good example of the initial contact would be, “Hello, Mr. Jones. My name is Sandra Smith. I’m an LPN/LVN and I’ll be one of your nurses today.” It is important that the patient be given the names of all caregivers and their specific roles. Never assume that a patient wishes to be called by his or her first name. They are entitled to be addressed in the manner that is most comfortable for them.

Proceed to orient the patient to the unit. Show the location of the call bell and demonstrate its use. Show the location of the bathroom and use of the emergency call bell next to the toilet. Also show the patient how to operate the television and the telephone (Figure 23-1). Explain about visiting hours and, if one is available, give the patient a printed orientation handout with this information. If the patient is to receive nothing by mouth (NPO), explain or reinforce this information. If the patient is not NPO and has no ordered fluid restriction, fill the water carafe and place it within the patient’s reach.

Although this initial contact is frequently brief and may immediately precede hurried preparations for surgery or other procedures, the patient must be made to feel welcome and valued. The patient must also be given ample opportunity to have questions answered and procedures explained. If the patient is too ill at the time of admission for a full orientation, it should be done as soon as the patient’s condition permits.

Care of Patient Belongings.: Hospitals provide very little space for personal belongings, but patients may find great comfort in wearing their own bathrobe or having a special picture on the bedside table or shelf. You can assist your patients to put belongings in the closet and encourage them to send home anything that will have no use during their stay. Valuables such as credit cards, money, or jewelry should be sent home with a family member. If this is not possible, obtain a valuables envelope and arrange for safe storage of these items following your facility’s specific protocol. Document all other items, such as dentures, hearing aids, or bedside clock, on the patient belongings list. Items that plug into electrical outlets need to be checked by the maintenance department to ensure they are properly grounded. During the patient’s stay, this list should be updated to indicate things sent home or new items brought in for the patient’s use.

Some patients will bring in their medications from home. Each facility will have a specific protocol regarding these medications. The medication reconciliation process should be used, comparing the patient’s medication orders to all of the medications that the patient has been taking. Most facilities will ask that you make a list of the medications and then send them home with the family. It is important to notify the physician of any medications the patient has been taking at home that are not included in the present orders. Know the proper procedure for your facility and follow it at all times.

Initial Nursing Assessment (Data Collection)

The nursing assessment in an acute care facility is written by the RN, but the LPN/LVN can greatly assist in this process by data gathering during the initial contact. Vital signs, lists of medications (including all over-the-counter medications, supplements, and herbals the patient takes), and information about allergies, previous hospital stays, illnesses, and surgeries can all be obtained by the LPN/LVN and given to the RN for use in the actual assessment. In some facilities, the nursing assessment is done during a preadmission interview, which greatly reduces the tasks that must be accomplished before patients are sent for their scheduled procedures.

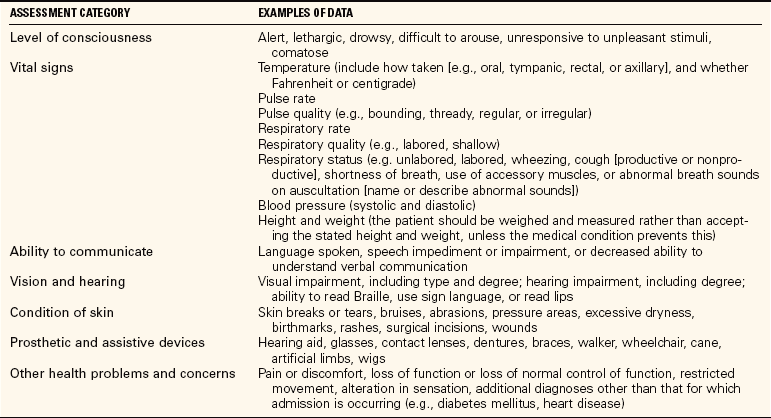

LPN/LVNs are frequently charge nurses in skilled nursing facilities and are responsible for completing the written assessment and care plan. When writing an assessment, it is important to accurately describe your findings. Most facilities use a check-off system, but a narrative description is still required. Table 23-1 shows the items to be assessed and gives examples of descriptive terms.

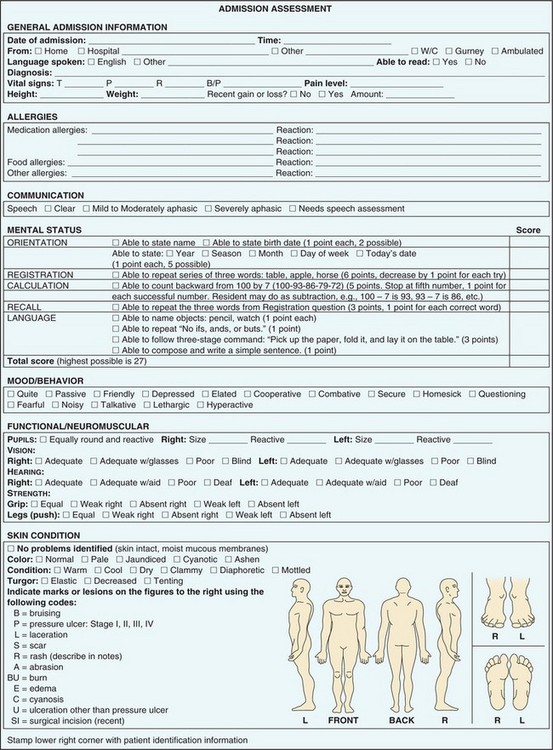

Figure 23-2 shows an example of the typical assessment form. Chapter 5 gives specific information on assessment data collection and use of nursing diagnoses. Chapter 6 discusses the writing of care plans.

Preparing the Chart

Most care facilities have unit secretaries who assist in the admission process by preparing the actual chart, transcribing orders, preparing lab slips and x-ray requests, and filling out consent forms. It is the responsibility of the nurse to check that everything has been accurately transcribed by the secretary. If the orders have been correctly transcribed, the nurse then signs immediately below them and also writes the date and time signed. The nurse must be able to set up a chart and do the transcription if there is no unit secretary available. Regardless of who does the actual transcription of orders and completion of request forms and consents, the nurse who checks and signs the orders is directly responsible for their accuracy. In most acute care facilities orders are verified by the RN, but in some acute facilities and in most skilled nursing facilities, this duty is performed by the LPN/LVN.

Admission orders are often long and complex. For safety, the individual transcribing the orders should make a checkmark by each order as it is processed. The nurse who reviews the orders must verify that each order has been processed and that the transcription is accurate. This means the nurse must read every lab slip, procedure request, and consent form, correcting as necessary. If there has been an error on a document to be signed, any changes must be clear and must be initialed. Any deletions must be crossed out with a single line, with the word “error” and the nurse’s initials written above. If a consent form has been transcribed inaccurately, or if the physician orders a change in the wording, it should be destroyed and a new form written for the patient’s signature.

Once transcription of the orders has been verified, the orders are signed. A line is drawn along the left margin of the orders being verified and then the nurse signs with the date and time immediately below the last order and the physician’s signature. The facility may require that this be done in red ink, or have some other specific protocol. Know and follow the policy of your facility.

Hospitals and other facilities have specific protocols for noting allergies. In most institutions they are not only written on the plan of care, but are also displayed on the front of the chart. In addition, patients often are given a colored armband with the allergies clearly listed.

PLAN OF CARE

Preparation of the written plan of care is part of the assessment and is done by the nurse with input from all the members of the health care team. The basis of the plan of care is the nursing process and nursing diagnosis, both of which are covered in detail in Chapters 4, 5, and 6.

PATIENT TRANSFER TO ANOTHER HOSPITAL UNIT

Changes in condition may require that a patient be transferred from one nursing unit to another. As patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) or cardiac care unit (CCU) become stable, they are often transferred to a definitive observation unit (DOU), also sometimes called a step-down unit, or to the med-surg unit. A patient who was originally admitted to the medical or surgical unit may become less stable and be transferred to the DOU, ICU, or CCU.

When a patient is to be transferred, the patient’s physician must be notified and approve the transfer. In situations of sudden deterioration of condition, the patient may be moved immediately per established hospital protocols, but in general transfers from one nursing area to another require a specific order by the attending physician. The admissions office, or in some facilities the business office, must be notified of any transfers.

It is also important that the patient’s family or significant other be notified, preferably prior to the actual transfer. In emergency situations, notification should be made as soon as possible.

Each facility has specific guidelines as to documentation, but it is always necessary that the transfer be recorded in the nursing notes, by both the nurse transferring the patient and the nurse receiving the patient. The care plan must be reviewed and revised and a full report given to the receiving nurse when the patient arrives on the new unit.

Failure to pass on necessary information in the process of transferring a patient has been cited as a major factor in patient care errors. The major accrediting body in the United States, The Joint Commission, has added “improving the effectiveness of communication among caregivers” to their patient safety goals. Their guidelines state that every facility is to have procedures in place that provide for accurate communication of patient information at the time of any transfer, whether to another nursing unit, to an ancillary department for tests or procedures, or to another facility. This information will include a complete listing of the patient’s current medications. They further state that this should include the opportunity for the person receiving the patient to ask questions regarding the patient and the plan of treatment.

Loss of patient belongings is most likely to happen during a transfer from one unit to another. This is particularly true of durable medical equipment, such as walkers, canes, and wheelchairs, because they are often overlooked on the assumption that they belong to the facility rather than the patient. For this reason, all equipment brought to the hospital by the patient should be clearly labeled, usually with a wide piece of tape on which the patient’s name is written in large letters.

Glasses, dentures, hearing aids, and jewelry are the other most frequently lost items, and replacement can be very expensive for the facility. Check the drawers, shelves, patient bathroom, and bed linens carefully to ensure that such things are not accidentally thrown away or sent to the laundry.

DISCHARGING THE PATIENT

Discharge planning begins at admission, particularly when the diagnosis indicates the patient will need rehabilitation or long-term assistance. Members of the health care team must document needs to be addressed so the patient can be discharged from acute care. The discharge planner (an RN who implements and organizes the plan for patient discharge) will use this information, as well as information gathered from the patient, the family, and the physician, to make appropriate discharge arrangements for the patient.

The actual discharge orders are written by the physician. When discharge orders are received, you should assist as needed with notifying the family or significant other, collecting patient belongings, and preparing the patient for the ride home or to a new facility. Just prior to discharge, retrieve any valuables stored in the hospital safe, and have the patient sign for them in accordance with hospital protocol.

DISCHARGE TO AN EXTENDED CARE OR REHABILITATION FACILITY

Acute hospital stays are often short, and patients may not be well enough to go directly home at the time of discharge. A growing number of patients are being discharged to rehabilitation or extended-care facilities.

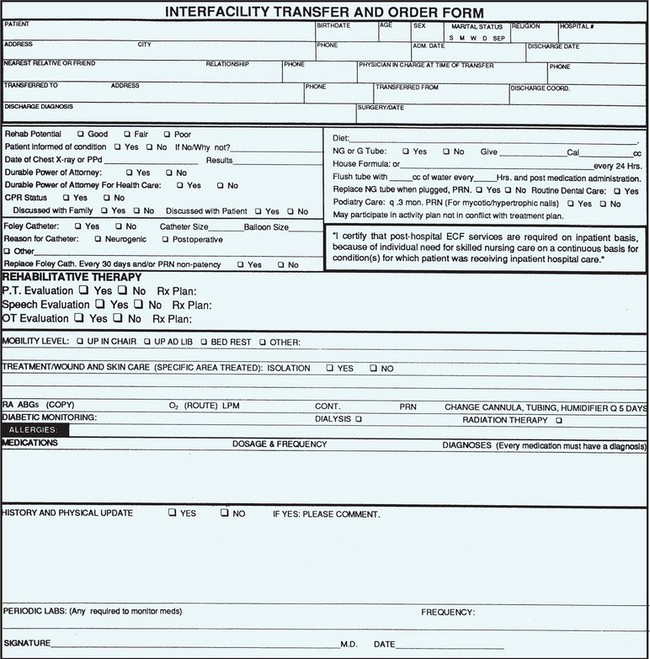

To ensure that information regarding necessary treatments, medications, and special needs is clearly communicated, the RN completes a detailed patient information sheet for the receiving facility (Figure 23-3). Information recorded includes primary and secondary diagnoses; current orders; medications (including over-the-counter medications, dietary supplements, and any herbals the patient takes), noting dosage, route, frequency, and time of last dose given; physician names and phone numbers; and a brief synopsis of the hospital stay. It is preferable but not always possible for the discharging nurse to call the admitting nurse at the new facility and give a verbal report prior to sending the patient.

If the patient is to be transferred by ambulance, arrangements for this service are made by the hospital’s discharge planner. If the patient is able to go by private car and the physician is in agreement, the patient is taken to the car via wheelchair by a staff member.

Any records to be transferred with the patient must be ready in an envelope before the transporting vehicle arrives. Often a copy of the discharge summary and instructions has also been faxed to the receiving facility to allow them to make advanced arrangements for the patient’s arrival.

Just prior to the time of discharge, assist the patient with packing of personal belongings. You should also assist the patient as necessary to dress in a manner appropriate to the mode of transport and the weather conditions.

DISCHARGE HOME

Patients being discharged directly home require essentially the same preparations as those discussed above. Most patients discharged directly home will travel by private car, but special transport may be needed for patients with severe mobility restrictions. It is the nurse’s responsibility to verify that necessary arrangements have been made so the discharge goes smoothly for the patient and family.

Written discharge instructions are prepared by the RN and reviewed with the patient and often with family members as well. Both the patient and the nurse sign the form, a copy is given to the patient, and one is placed in the chart. The discharge form lists medications, activity restrictions, special diet instructions, and ordered follow-up appointments. The name and phone number of the physician are also listed. This is particularly important if the patient is being cared for by a new physician. For example, an accident victim may have been assigned an orthopedic surgeon during admission through the emergency department and will need to know how to contact this physician for care following discharge.

Home Health Care

Many patients, particularly the elderly, receive home health care following discharge. Home health services may include skilled nursing, such as wound care, diabetic care and teaching, and intravenous medication administration. Physical, occupational, or speech therapy and respiratory care are also often part of home care services, as is personal care performed by a home health aide. Counseling and information regarding long-term planning, financial assistance, or community services available can be provided by a medical social worker (MSW). Many services that were once available only to hospital patients are now routinely provided in the home setting.

There are many advantages to home health care. These include reduced cost, decreased exposure to potentially serious infections, and most important, being in a familiar, comfortable environment. Medicare, Medicaid, and some insurance and managed care plans provide for payment of portions or all of these services when ordered by a physician.

Discharge Against Medical Advice

Occasionally a patient will insist on leaving the hospital against the advice of the physician. The patient has the right to make this choice. It is the responsibility of the health care team to help patients understand how the decision to leave the hospital may impact their health. Listen to what the patient has to say, answer questions, and offer to ask the physician or supervising nurse to talk with the patient.

If the patient’s ultimate decision is to leave, notify the physician immediately. If the physician feels it is inappropriate for a discharge order to be written, the patient is asked to sign a form stating that he is leaving against medical advice (AMA). Sometimes a patient will refuse to sign. You must document this, and then date and sign the form in the space provided. The patient’s stated reasons for leaving are written in the nursing notes.

When patients choose to leave against medical advice, they also need to be informed that insurance carriers will sometimes refuse to pay the hospital bill and that they would then become liable. Document this information in the chart.

DEATH OF A PATIENT

Although there is a growing trend toward remaining at home to die, most deaths still occur in hospitals and long-term care facilities. It is often a difficult time for family, friends, and at times even the hospital staff. Death after a long, good life or at the end of lingering illness or pain may be seen as a kind and welcome release. Death of a vigorous, active adult or a child, however, is often viewed as unfair and even unthinkable. Death may also bring great disruption to family life, especially if the individual was the primary wage earner or provider of care for the family children. See Chapter 15 for more about care of the dying patient.

PROVIDING SUPPORT FOR SIGNIFICANT OTHERS

Often the most important gift we can give the bereaved is just being there. Simply sit and listen while they talk of their loss and the fears about the changes it will bring. People need to grieve; it is an important step in healing.

Many people derive significant comfort from spiritual or religious beliefs and practices. Offer to call their priest, minister, rabbi, or spiritual advisor. If death is anticipated, doing this while the patient still lives can be particularly helpful, especially if the religious beliefs include specific predeath rituals.

You can also offer to make phone calls or arrangements for someone to come and take the significant other’s home if this seems appropriate. An elderly widow or widower alone at the bedside of the just-deceased spouse, for example, may have difficulty making such a decision without some guidance or assistance.

Allow the family and friends adequate time at the bedside to say their good-byes. Crying, touching their loved one, and hugging each other are all part of a necessary human process in dealing with grief.

It is important to note that you must have dealt with your own feelings about death before you can be a good support person for someone else. Young nurses should not feel personally rejected if the family looks to older staff members for comfort and assistance. Older individuals have usually had more opportunity to experience loss through death, and family members frequently feel they will have a deeper understanding of the impact.

PRONOUNCEMENT OF DEATH

In most states it is still required that a physician pronounce death. You must be familiar with the policy and procedure for your facility and adhere to it. The time life signs ceased, the time death was pronounced, and the name of the person making the official pronouncement must be documented in the nursing notes.

AUTOPSIES

Most deaths are not followed by an autopsy (examination of the remains by a pathologist to determine cause of death). Autopsy is usually performed when the patient has died of unknown causes, has died at the hands of another, or has not been seen within a specific period of time by a physician. In such cases the death becomes a coroner’s case, and it is the coroner (city/county medical officer responsible for investigating unexplained death) who orders and authorizes the autopsy. The laws governing autopsy in these instances vary, and facility guidelines will follow local state law.

Autopsy may also be performed when it is felt that information valuable to medical research may be obtained, or when the family has questions about the cause of death. In such cases, the next of kin must authorize the autopsy.

ORGAN DONATION

The need for donor organs grows continually. Thousands of people each year owe their opportunity for a longer, healthier life to an organ donation. Requests to the family for organ donation are usually done by a physician or a nurse specially trained to do this. When handled in a sensitive, caring manner, requests for organ donation can be an opportunity for the family to allow something good to come out of a personal tragedy.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. Obtaining authorization for an emergency admission is often the responsibility of:

2. When instructing a patient scheduled for same-day surgery, you tell would him to: (Select all that apply.)

1. report to the same-day surgery unit 3 to 4 hours before the scheduled procedure.

2. bring only essential items to the hospital.

3. have someone available to take him home after the procedure.

4. report to the same-day surgery unit 1 to 2 hours before the scheduled procedure.

3. When making the first contact with a patient, it is most important to:

4. In an acute care facility, the person responsible for the initial nursing assessment is:

5. In a skilled nursing facility, the person responsible for the initial nursing assessment may be: (Select all that apply.)

6. Orders are verified and signed off by:

7. If a patient brings credit cards, money, and jewelry to the hospital, you can provide for their security by: (Select all that apply.)

1. sending all of the items home with the family.

2. placing the contents in a valuables envelope and storing it in the bedside drawer.

3. placing the contents in a valuables envelope to be stored in a safe.

4. making a list of all the items on a “belongings list” and placing it in the chart.

8. When transferring a patient to another facility, copies of pertinent medical records:

1. are the responsibility of the family to deliver.

2. must accompany the patient.

3. are mailed at the time of transfer.

4. must be delivered by hospital messenger because they are confidential.

9. Discharge instructions for patients who go directly home from the hospital should include: (Select all that apply.)

1. physician’s phone number for follow-up appointment.

2. instructions on how and when to take medications.

3. instructions for activity restrictions and exercises to be performed.

4. signs and symptoms of complications to report to the physician.

10. If a patient decides to leave against medical advice:

1. he must be detained until the physician can come in and talk with him.

2. he must sign a release or he may not leave the facility.

3. a court order should be obtained to force him to remain for treatment.

11. An autopsy may be required when: (Select all that apply.)