Loss, Grief, the Dying Patient, and Palliative Care

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Describe the stages of grief and of dying, with their associated behaviors and feelings.

2 Discuss the concept of hospice care.

3 Identify four expected symptoms related to metabolic changes at end-of-life stages.

4 Identify three common fears a patient is likely to experience when dying.

5 List the common signs of impending death.

6 Explain the difference between the patient’s right to refuse treatment and assisted suicide.

7 Explain how the Code for Nurses provides guidelines for the nurse’s behavior regarding the patient’s right to refuse treatment, euthanasia, and assisted suicide.

1 Identify ways in which you can support or instill hope in the terminally ill patient and his family.

2 Demonstrate compassionate therapeutic communication techniques with a terminally ill patient and/or his family.

3 Describe one nursing intervention for comfort care that can be implemented in a hospital or a nursing home for a dying patient for each of the following problems: pain, nausea, dyspnea, anxiety, constipation, incontinence, thirst, and anorexia.

4 Explain the reason for completing an advance directive to a terminally ill patient, and what “health care proxy” and “DNR” mean in lay language.

5 Prepare to provide information regarding organ or tissue donation in response to family questions.

6 Prepare to perform postmortem care for a deceased patient.

acceptance (p. 196)

advance directive (p. 202)

anticipatory grieving ( , p. 193)

, p. 193)

assisted suicide ( , p. 203)

, p. 203)

autopsy (p. 204)

bargaining (p. 196)

bereavement ( , p. 193)

, p. 193)

brain death (p. 194)

Cheyne-Stokes respirations ( , p. 202)

, p. 202)

closure ( , p. 202)

, p. 202)

comfort care (p. 197)

coroner ( , p. 204)

, p. 204)

death (p. 194)

denial (p. 196)

durable power of attorney for health care ( , p. 202)

, p. 202)

dysfunctional ( , p. 193)

, p. 193)

euthanasia (active, passive) ( ,

,  ,

, , p. 203)

, p. 203)

grief, grieving process (p. 193)

health care proxy ( , p. 202)

, p. 202)

hope (p. 197)

hospice ( , p. 195)

, p. 195)

loss (p. 193)

obituary ( , p. 202)

, p. 202)

palliation ( , p. 197)

, p. 197)

postmortem ( , p. 204)

, p. 204)

rigor mortis ( , p. 205)

, p. 205)

shroud ( , p. 205)

, p. 205)

thanatology ( , p. 196)

, p. 196)

Loss, grief, and death are well-known and universal parts of life. Loss involves change, and some loss is necessary for normal growth and development; for example, a child loses baby teeth to make way for permanent teeth. Other losses do not seem to have positive outcomes, such as loss of health, loss of a significant other, or loss of life. People adjust to loss through the grieving process, and coping with loss is learned from childhood on. A person’s reaction to loss is influenced by the importance of what was lost and the culture in which the person is raised.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics (2007), life expectancy recently increased to 77.9 years, mainly because of advances in treatment of heart disease, cancer, AIDS, and stroke. Heart disease and cancer are responsible for 50% of all deaths. HIV/ AIDS is no longer one of the 15 leading causes of death. Alzheimer’s disease has moved from 11th to 7th place. Accidents rank number 5 and diabetes number 6. Life expectancy for white females is highest (80 years), followed by African American females (76.5 years), white males (75.7 years), and African American males (69.8 years). The most recent death statistics indicate approximately 2,448,017 deaths in the United States annually (National Vital Statistics Report, 2008).

Death is a universally shared event. In all cultures and religions, there are beliefs and rituals to explain and cope with death, loss, and grief. It is common in American society to avoid talking about death, and to be unable to imagine our own death. Expressions such as “passed away,” or “went to his reward” are used instead of “died.” Children are often kept away from funerals, and most people have little contact with the dying. Many adults can state they have never seen a dead body, and more can say they have not been present during a death. Only in recent years has there been a move away from silence and denial toward a willingness to examine a universal life event: death.

Nurses and other health care professionals may have similar fears and anxieties about the end of life. Because so many deaths occur in hospitals and nursing homes, health care workers see more of death and dying than other people do. They are responsible for providing the best care possible to their dying patients. However, to meet the emotional and physical needs of patients and their significant others, nurses must first take the time to look at their own views of death and come to terms with its reality.

LOSS AND GRIEF

Loss is to no longer possess or have an object, person, or situation. It is a familiar occurrence in everyday life, for example, losing money, a job, one’s health, or life. One’s own death is often described as the most difficult loss for a person to accept. A loss can be physical, such as the amputation of a leg, or inability to speak or walk after a stroke. A loss can also be psychosocial. Disfiguring surgery or scarring from burns may result in an altered self-image and emotional problems. A person may lose the ability to carry out the role of homemaker or wage earner as a result of illness. A familiar environment and independence may be lost with a move to a nursing home. Very often loss consists of both physical and psychosocial aspects. Loss can be viewed as ranging from minor to catastrophic. A person’s reaction to loss depends not so much on the size of the loss but on the person’s value of what has been lost plus the influence of previous experiences and the ability to cope. Only the person experiencing the loss can define the value of the loss– you must put aside your own values regarding loss and accept the patient’s meaning of loss.

GRIEF

Grief is the total emotional feeling of pain and distress that a person experiences as a reaction to loss. The grieving process occurs over a period of time. A person adapts to the feelings and moves through the pain and associated symptoms toward recovery or acceptance. People who are dying as well as their loved ones experience loss and grief when faced with a terminal diagnosis. Bereavement is the state of having suffered a loss by death. A person who is grieving may experience physical and emotional symptoms, such as crying, fatigue, changes in appetite, sleep disturbances, loneliness, and sadness (Box 15-1). When a person thinks or knows that a loss is going to occur in the future, anticipatory grieving may occur before the loss actually happens. This happens when patients and their families face a serious or life-threatening illness, and it is believed to improve coping with the loss when it occurs.

Grieving may also be dysfunctional when it falls outside normal responses. In prolonged grieving, the person seems trapped in a stage and unable to progress. However, there is no actual time frame for completion of grieving, and a major loss may result in grieving for 1 to 2 years. Visible absence of grieving may be viewed by others as a good adjustment, but it often results in later psychosomatic illness.

STAGES OF GRIEF

It has long been thought that the grieving person goes through stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Each stage has identifying behaviors and feelings, and each person moves through the stages at his own pace, and may skip or return to an earlier stage. Nurses have always been taught to recognize the great individuality of the grieving person and offer supportive care for the symptoms or behavior the person demonstrates, rather than anticipating what grieving response is the right one.

Until recently, the hypothesis of these stages had not been investigated empirically. However, the stages of grief theory was put to the test by Maciejewski and others (2007). Examination of the stage theory of grief has revealed that denial is not the first grief indicator. Instead, the loss is readily accepted, and yearning is the dominant grief indicator. This is followed by anger and depression. The five grief indicators’denial, yearning, anger, depression, and acceptance’peak within 6 months after the loss. The nurse should reevaluate and create additional nursing plans for patients who continue to score high in these areas after 6 months.

You can assist persons who are grieving by accepting their feelings and behaviors and validating their loss. To validate the loss is to reassure the grieving person that the loss was important and understood. Quiet presence, a warm caring concern for the person’s well-being, and the ability to listen to the person speak about the pain and loss are supportive (Figure 15-1). Encourage grieving individuals to tell you what the person (or lost object) was like, and what the loss means to them. Avoid the use of clichés like “You’ll forget all about this after awhile,” and do not minimize the loss. Observe the nonverbal communication of the patient, and be aware of and use appropriate nonverbal language such as a smile or a gentle touch. Crying may be embarrassing for the patient, and a simple act of handing a tissue acknowledges the acceptability of weeping. You should never tell a patient “Don’t cry.” You may be uncomfortable in a situation in which you feel like crying along with the patient. The patient will not be offended by your crying, and may draw support from a shared experience. You can acknowledge feelings of sadness and loss, but should avoid saying “I know just how you feel,” because this minimizes the patient’s feelings.

As a person moves through the stages of the grieving process, there is a continuing decline in function as the person attempts to adjust to the loss. With the stage of acceptance, there is gradual improvement in the level of daily function. Successful movement through the grieving stages allows the person to emerge with realistic memories of the event and the deceased, find renewed energy, a sense that life has meaning, and an ability to again experience pleasure, social relationships, and activities. The time it takes to move through the stages will depend on the loss and its meaning to the person.

DEATH AND DYING

Death is an event marked in different ways. The absence of a heartbeat and breathing was and is a historic and widely accepted definition of death. In today’s high-tech hospital environment, a ventilator can support the patient’s breathing and thereby provide oxygen to the heart when it would not continue unassisted. So, a definition of death that has been used since the 1970s is brain death (the permanent stopping of integrated functioning of the person as a whole as evidenced by the absence of EEG waves).

Except for suicide, a person has no control over when or how death occurs. Death may be sudden, unexpected, and instant, as when a person is killed in an accident or dies of a massive heart attack or stroke. Death may also be the end of a long battle against a chronic disease such as cancer or heart disease, or simply the diminished function of multiple systems in old age. Death is also encountered in situations in which the outcome could be either death or survival, as in an acute severe infection or trauma. Nurses who work in an emergency room, intensive care unit, medical-surgical unit, nursing home, or hospice will each have different experiences of patients’ death and dying (Cultural Cues 15-1). In these different cases and situations, the individuals who die and those who care about them will experience different emotions and physical reactions.

Each death and dying experience is unique, although there are commonalities that can help you to provide truly satisfying care to the patient and the family (Box 15-2).

END-OF-LIFE CARE WITHIN THE HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

The focus in our health care system has been one of cure and the development of diagnostic, technical, and chemical interventions to treat disease and injury that often have been fatal in the past. As a result, patients may be viewed as failures of the system if they die in spite of the best efforts of the health care team. Those with terminal illness who refuse life-prolonging (or death-delaying) treatment may feel as though their needs will not be met in the acute care environment (Box 15-3).

HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE CARE

Hospice is a philosophy of care for the dying and their families. It developed in England in the early 1960s as a reaction to the needs of dying people for care and comfort. After World War II, hospitals rather than the home had become the place where people died. Nurses provided around-the-clock care, and families were relieved of that burden. However, many of the needs of the dying were not being met in the hospital setting. A hospice originally was a medieval guest house or stopping place for travelers. Now the name “hospice” is also used to describe the specialized care provided to the dying in small clinics, houses, or the patient’s (or patient’s family’s) own home. Currently, a hospice is not necessarily a special facility but rather a program of care to meet the needs of the terminally ill and their families in their home or a health care facility.

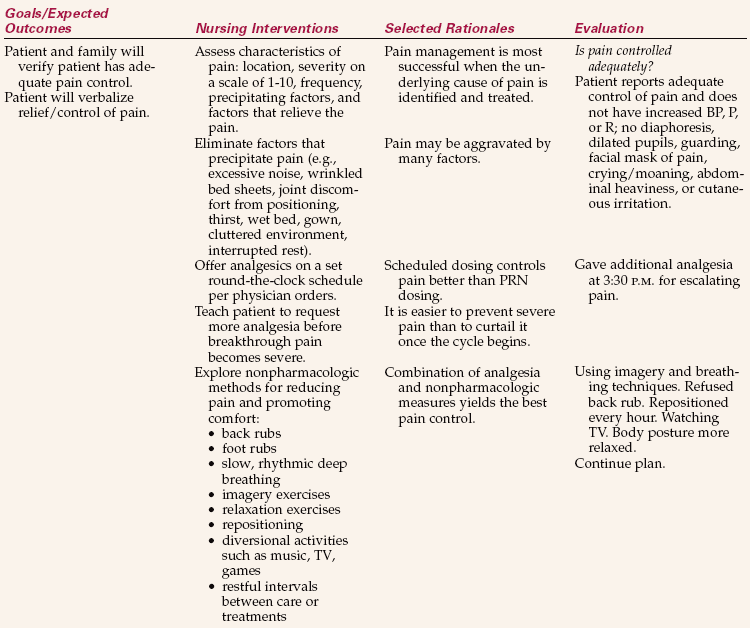

The hospice philosophy is based on the acceptance of death as a natural part of life and emphasizes the quality of remaining life. The medical, nursing, social, psychological, and spiritual needs of the patients and their significant others are met through a team approach. The team provides palliative care. Palliative care is concerned with treating symptoms, providing comfort measures, and promoting the best quality of life possible day by remaining day (see Nursing Care Plan 15-1). Nurses who care for the dying patient have a unique opportunityto become an intimate part of the patients’ lives. Nurses can support the dying patient physically and emotionally while maintaining a professional role.

Whether assisting the patient in the hospital or at home, certain comfort measures are required. Palliative care requires a specialized body of knowledge and skills that can be difficult to learn since it isn’t focused on “cure.” Family members are involved in this planning, and necessary support is provided to meet the needs of all those affected by the impending death (Figure 15-2). RNs and LPNs or home health aides provide nursing and personal care; trained volunteers are used to provide a variety of respite (relief) or socialization services. Hospice care may be provided in the patient’s home, nursing home, hospital, or hospice unit. Follow-up of the family during the year following the death provides assistance with the grieving process.

Palliative care is a fairly new field, and many nurses have chosen to undertake this specialty. The palliative care nurse is an important element for the patient’s and family’s comfort during this transition. In September 2004, a certification examination for LPNs and LVNs was launched by the National Board for Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nurses (NBCHPN). Detailed information is available by calling (888) 519-9901 or visiting www.nbchpn.org.

THE DYING PROCESS

Kübler-Ross and the Five Stages of Coping with Impending Death

In the late 1960s, Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a psychiatrist, began talking with terminally ill patients and identifying their needs. She also began educating medical students, nurses, and doctors about death and the stages through which she saw terminally ill patients progress. She transformed the way the health care community and much of the public view death, and she promoted much additional research into the areas of loss and death. As a result of her pioneering work, nurses and doctors are much more sensitive to the needs of the dying patient and family. Other researchers have added to her work, and the field of thanatology (the study of death) continues to grow.

Dr. Kübler-Ross’ identification of the stages a dying person moves through has been the foundation for understanding the dying process. Five stages, similar to those of the grief process, are described as being characteristic of dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (Table 15-1). The stages overlap, and as with the grieving process, the patient may move back and forth or even skip stages. In some cases, the patient may “get stuck” in one stage and not move through to acceptance. Family members are often at different stages from the patient and each other. Nurses, too, will move through the stages when they care for patients who are dying.

Table 15-1

Kübler-Ross’s Stages of Coping with Death

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

| Denial | “No, not me.” The person cannot believe the diagnosis or prognosis. It serves as a buffer to protect the patient from an uncomfortable and painful situation. A patient may seek other opinions or believe there has been an error. |

| Anger | “Why me?” The person looks for a cause or fixes blame. Doctors and nurses are often the target of displaced anger, as well as family and even God. Powerlessness to control the disease and events is an underlying issue. |

| Bargaining | “If I’m good, then I get a reward.” The wish is for extension of life, or later for relief from pain, and the person knows from past experience that “good behavior” is often rewarded. |

| Depression | “It’s hopeless.” There is a sense of great loss, of the impending loss of being. People mourn losing family, possessions, responsibilities, all they value. |

| Acceptance | “I’m ready.” The pain is gone, the struggle is over, the patient has found peace. There is withdrawal from the engagement of everyday activities and interests. Verbal communication is less important, and touch and presence are most important. |

Other Theories of the Dying Process

Theories of the dying process have identified other emotions that are commonly seen during the dying process: fear of dying, yearning, guilt, hope, despair, and even humor. Some professionals point out that an individual’s reaction to the threat of death is consistent with the way the person has coped with difficulties in the past, and that rather than experiencing stages, a person reacts with denial, anger, bargaining, hope, despair,and so forth in a fluctuating pattern. Coping with death takes many forms and is not limited to the dying person. It involves all who are connected with the dying person’s experience: family, friends, and caregivers. Coping with death may also involve tasks or actions that the dying person must work on in the areas of physical, social, psychological, and spiritual being (Cultural Cues 15-2). An example of a physical task would be to minimize physical distress such as pain. A social task might be to enhance or restore a relationship that is important to the dying person. Another example would be updating a will, making amends, and saying goodbye to friends and loved ones.

Hope and the Dying Process

Hope is an inner positive life force, a feeling that what is desired is possible. It takes many forms and changes as the patient declines. At first there is hope for cure, then a hope that treatment will be possible, next a hope for the prolonging of life, and finally hope for a peaceful death. Open-ended questions such as “What are you hoping for from this admission?” or “What are you hoping for today?” can allow patients to talk about their needs. You can always be supportive of hope by recognizing and affirming the wish the patient is expressing.

NURSING AND THE DYING PROCESS

Patients express many fears when they know they are dying: fear of pain, loneliness, abandonment, the unknown, loss of dignity, and loss of control. There may also be unfinished business that occupies the patient’s thoughts. The concept of comfort care is focused on identifying symptoms that cause the patient distress and adequately treating those symptoms. Palliation is the relief of symptoms when cure is no longer possible, and treatment is provided solely for comfort. This concept can be applied in any health care setting. Prevention of many symptoms is possible by anticipating their likelihood. The application of the nursing process to care of the dying patient uses skills and knowledge from physical, emotional, social, and spiritual contexts.

Throughout the nursing process, therapeutic communication is an important skill the nurse uses to promote communication. Beginning students and new graduates are often fearful of not knowing what to say or of saying the wrong thing. The first step in addressing these fears is for you to become comfortable with your own beliefs, values, and attitudes about death and dying. Second, read and learn about the actual dying process and observe experienced nurses talking with dying patients and grieving relatives. Third, be open to the difficult questions of life and death that permit patients to discuss their feelings and needs. Patients are usually very sensitive as to how caregivers (and family members) react to uncomfortable subjects. Often, a patient will not bring up a subject with family members or staff who avoid conversations that are painful or anxiety provoking. Time and experience are the best teachers. Chapter 8 discusses specific therapeutic communication skills in greater detail.

A trusting relationship with the patient occurs as you are able to meet the identified needs. Listening skills, observation, and use of nonverbal communication, touch, and presence all contribute to the patient’s sense of acceptance. Fears of isolation or loneliness decrease with nursing care that seeks to treat the patient with compassion and individuality. The family’s anxiety decreases as they see the patient responding to the care and attention of the team.

APPLICATION of the NURSING PROCESS

A baseline assessment and continuing data collection are essential to identify the problems and needs of the patient and his family. An admission history should determine what they have been told by the physician regarding the illness and its expected course. Asking “What has your doctor told you about your condition?” may lead to identifying knowledge the patient needs in order to make informed decisions. Questions about advance directives regarding treatment options, resuscitation, advanced life support, and organ donation can provide information about the patient’s attitude toward death and the stage of his grief or dying reaction (denial, anger, etc.). Asking questions about religious beliefs and practices, as well as asking directly “What do you hope for during this admission?” and “What are your concerns?” provides data for the provision of comprehensive comfort care. At no time should the patient be pushed to discuss something he is obviously avoiding. A question such as “Is there anything else you’d like to talk about?” opens the door to issues the patient may wish to discuss.

An assessment of the patient’s physical condition would include such measures as weight (with attention to usual weight), mobility and the ability to perform activities of daily living, weakness or energy level, appetite (nausea, indigestion, gas), bowel and bladder function, and respiratory function (Safety Alert 15-1). Special attention should be paid to assessing pain: location, nature, and what relieves it or makes it worse. Pain should then be assessed using a 0-to-10 scale or similar method of measuring the patient’s report of pain. The frequency of pain assessment will depend on many factors, such as the severity of pain and whether pain is increasing or well controlled on the current treatment regimen (see Chapter 31).

The patient’s emotional condition can often be observed during the interaction, and symptoms such as anxiety, agitation, confusion, or depression may be obvious. Validating your observation with the patient allows him to speak about his feelings. Stating “Tell me how you are coping with all this” begins to identify strengths and needs. Spiritual assessment can begin with questions about the patient’s religious affiliation, and whether he would like to meet with a spiritual advisor (chaplain, rabbi, religious leader). Even when a patient indicates “none” for religious affiliation, spiritual needs may be present. Clues regarding spiritual distress may be found in questions such as “Why is God punishing me?” or what the meaning in his life has been.

Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing diagnoses for the dying patient will be varied, depending on the disease process. For example, a patient dying of end-stage renal disease will have problems with fluid excess, whereas a patient dying of chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) will have problems with ineffective airway clearance. Certain nursing diagnoses are common at some point to most dying patients (Box 15-4).

Planning

It is very important to include the patient and his family in the planning of care, and in establishing the goals or outcomes. Planning should be a team effort, with all members of the team aware of the patient’s goals and needs. Giving the patient control is a first priority at a time when it seems that he has no control. As far as possible, agency rules and routines that are geared toward cure should be relaxed to recognize that the goal is comfort. These would include relaxing restrictive visiting hours, eliminating routine vital signs and lab work, and avoiding rigid schedules for getting up, bathing, or sleeping.

Implementation

The nurse promotes self-care as long as the patient is able. Family members can derive much satisfaction in learning to provide physical care when the patient is no longer able to be independent. Be sensitive to patient or family member reluctance to provide (or receive) what is uncomfortable for either one, such as performing perineal care for a parent.

Common Problems of the Dying Patient and Nursing Management

Anticipatory Guidance.: Anticipating the death assists in preparing the family and patient by giving them guidance about physical changes, symptoms, and complications that may arise. This may also aid the patient and family in deciding about possible hospice care.

End-Stage Symptom Management.: There are many expected symptoms, such as pain, gastrointestinal distress, dyspnea, fatigue, cough, death rattle, and delirium, that are related to metabolic changes at the end of life. The last few days of patient life have been studied extensively. The nurse must recognize these symptoms and be able to either alleviate them or help explain them to the patient and family.

Pain Control.: Although nursing research has demonstrated safe and effective principles of pain control, many terminally ill patients unnecessarily die with uncontrolled pain. It is perhaps the first fear patients have regarding dying. Several myths still contribute to inadequate pain relief. The patient may fear becoming an addict, or that the medication will not work when he needs it if he takes it for minimal pain. Another fear that nurses have is that the pain medicine will result in hastening the patient’s death by depressing respirations.Still a third is the reliance on PRN (as-needed) medication for end-of-life pain rather than around-the-clock dosing. A truly compassionate nurse studies and learns about pain management and applies those principles in daily practice.

Pain can be controlled (eliminated) in almost all cases when the medical and nursing team work together (Nursing Care Plan 15-1). Regularly scheduled pain medication with PRN backup for breakthrough pain is one of the most effective methods of controlling pain. Carefully assess pain location, intensity, and response to medication every 2 to 4 hours, or more often if needed, to determine the necessity for increases in dosage (Health Promotion Points 15-1). There is no concern for addiction or of reaching a safety or effectiveness limit when narcotics are increased in response to pain for the dying patient. Patients with severe pain can receive huge doses of narcotics without respiratory depression or tolerance when the dose has been increased in response to increasing pain. Since comfort is the goal of palliative care, administering only oral medications, when feasible, is the preferred choice. However, this may not be possible as death draws near, and it is also the goal to allow a pain-free death. In some cases it may be possible to administer transdermal and/or rectal pain medications. The oral route and long-acting transdermal patches can also avoid the necessity of injections. Even when the patient is no longer taking fluids by mouth, small amounts of concentrated pain medication can be inserted in the buccal cavity (cheek) (Table 15-2). Transdermal fentanyl has helped eliminate the burden of pain at the end of life. Sometimes this regimen is supplemented with rescue doses of morphine if pain isn’t controlled. Whatever the regimen for pain control, studies have shown that pain relief, either total or at least to a level that is tolerable, is possible 75% to 97% of the time.

Table 15-2

Opioid Use in Patients with Renal Impairment

| DRUG | RECOMMENDATION |

| Morphine | Use cautiously with dose adjustment and careful monitoring |

| Hydrocodone | Use cautiously with dose adjustment and careful monitoring |

| Oxycodone | Use cautiously with dose adjustment and careful monitoring |

| Codeine | DO NOT USE |

| Methadone | Safe |

| Fentanyl | Appears safe, reduce dose |

| Meperidine | DO NOT USE |

| Propoxyphene | DO NOT USE |

Nonchemical approaches to pain relief may include visualization and guided imagery, relaxation and breathing exercises, massage, music therapy, meditation, religious healing, biofeedback, hypnosis or self-hypnosis, the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and hydrotherapy (e.g., whirlpool). Teach the patient these simple techniques as an adjunct to drug therapy. Provide a quiet environment and assist the patient as necessary (see Chapter 31).

Constipation, Diarrhea.: Constipation is predictable for a patient receiving opiates, experiencing decreased fluid intake and mobility, and having certain abdominal diseases. In addition to classic nursing measures for preventing constipation (increasing fiber, fluids, and exercise; see Chapter 30), consult with the physician for orders for stool softeners and a standing laxative order. Suppositories and enemas, or manual disimpaction, can be avoided in most cases with careful monitoring and adherence to a laxative schedule.

Anorexia, Nausea, Vomiting.: Anorexia, or loss of appetite, may be due to nausea, drug side effects (especially a sore mouth), the disease process, or the slowdown that occurs naturally in the dying process. Antiemetics are the first choice to eliminate nausea and vomiting. Small servings, home-prepared food favorites, and attention to eliminating unpleasant sights and odors at mealtime may stimulate a poor appetite. A bad taste can be improved by frequent oral care, mouthwashes, or hard candies (sour balls). A nutritionist may be very helpful in suggesting food choices that are appealing as well as easily digested. You can do a great deal to support the patient and the family with an explanation of the dying process: that decreased intake is more comfortable for the patient than having food to digest and move through a system that is slowing down. There is also some evidence to suggest that starvation decreases the patient’s awareness of pain by producing chemicals that act as pain relievers. Weight loss is commonly seen in dying patients, but few patients complain of feeling hungry. Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) may also be a problem. Moistening the mouth with fluids or artificial saliva may be helpful. Additional care of the dysphagic patient is presented in Chapter 27.

Dehydration.: As death nears, patients spend more time sleeping or in a semiresponsive state. They take in fewer and fewer fluids until the question arises about providing intravenous (IV) fluids or tube feedings out of concern for dehydration. Research has shown that dehydration results in less distress and pain and that hydration does not improve comfort. Dry mouth and thirst are the most common complaints, which may be induced by the drugs being administered, and these can be alleviated by small sips of fluids, ice chips, and lip lubrication. Resulting decreased urine output means less effort to use a commodeor less incontinence. This is an issue that is best discussed before it arises, at the time advance directives are being established. It is an emotional issue, and families often have a difficult time accepting that withholding fluids is more comforting than administering them. Families can be comforted with an explanation of how the dying person is indeed made more comfortable by withholding fluids. The nurse must help educate the patient and family as to both the benefits and burdens of hydration. Many times the course is for patients to choose what to take and be allowed to refuse further nourishment. This is referred to as “patient-endorsed intake.”

Dyspnea.: Difficult breathing may be seen early in the dying process in certain lung or heart disorders. It is also seen shortly before death, when respirations may become noisy, irregular, or labored. Secretions in the lungs accumulate and block the airways to contribute to noisy or rattling respirations. The patient is usually not responsive, or not aware of the dyspnea, but it is very upsetting to family members. Suctioning is not effective in clearing the secretions, but medications such as a scopolamine patch or morphine can decrease secretions and ease breathing. Administering oxygen by nasal prongs may provide comfort.

Death Rattle.: Noisy respirations are heard when patients can no longer clear their throats of normal secretions. Family members are often alarmed and are afraid the patient will choke to death. In these cases, scopolamine or atropine, drugs that are known to reduce secretions, may be used to quiet the patient and bring breathing back to normal.

Delirium.: Dying patients may experience hallucinations and/or altered mental status. Nurses must first search for causes such as pain, positional discomfort, or bladder distention and address those physical problems. Next, the nurse should discuss the delirium with the patient’s family and encourage the family to talk to the patient in quiet tones while remaining calm.

Impaired Skin Integrity.: Weight loss, decreased nutrition, incontinence, and inactivity all contribute to the risk of skin breakdown. Turn and position the patient, use protective measures such as an air pressure mattress, heel or elbow protectors, and sheepskin or foam pads, and keep the skin clean and dry. An indwelling or condom catheter may be indicated to conserve the patient’s dwindling energy as well as to prevent skin breakdown.

Weakness, Fatigue, Decreased Ability to Perform Activities of Daily Living.: Increasing weakness eventually results in the patient’s becoming bed-bound. Accept the patient’s wishes regarding walking, sitting up in a chair, or remaining in bed. The dying patient is not going to get stronger or better; he gets weaker and weaker, not because he is lying in bed, but because he is dying. Allow the patient to do as much as possible for himself, and provide physical care when he is no longer able.

Anxiety, Depression, Agitation.: Emotional or psychological symptoms may be treated with appropriate drugs with good effect. Listen and use good therapeutic communication skills to allow the patient to express his fears, feelings, and needs, and to convey nonjudgmental acceptance (see Chapter 8). Skillful assessment of these symptoms may identify physical pain or spiritual distress that can be treated.

Spiritual Distress, Fear of Meaninglessness.: Each person needs to believe that his life has had meaning, and this is the essence of the spiritual nature of the dying process. A life review allows the patient to put his life in perspective. Reminiscing is one way of starting a life review. Encourage the patient to tell about family photographs or albums. Ask “What was it like when you were a child (or worked on the farm, lived in the city, met your wife)?” It is more important to listen than to talk.

Evaluation: Evaluation is based on the specific expected outcomes written for the patient. These will depend on which nursing diagnoses are pertinent to the patient’s situation. In most cases, the degree of comfort obtained for the patient by the nursing interventions will need to be evaluated. Was pain adequately controlled? Was tissue integrity protected? Were actions to facilitate the patient’s and family’s grieving process effective? Was the patient’s fear alleviated? Did interventions for a self-care deficit make the patient more comfortable? Answers to these questions will help determine whether expected outcomes have been met. If the plan of care is not effective, the plan must be revised.

SIGNS OF IMPENDING DEATH

As death approaches, the patient grows physically weaker and begins to spend more time sleeping. Body functions slow, appetite decreases, and the patient may refuse even favorite foods and later fluids as well. Explain to the patient and the family what to expect. Moistening the patient’s lips and mouth, and providing oral hygiene, will be more comforting than “pushing” food or fluids.

Urine output decreases and urine becomes more concentrated. There may be edema of the extremities or over the sacrum. Incontinence may occur as patients become less aware of their surroundings. However, be alert to the possibility of urinary retention and the need for catheterization.

Vital signs change as death approaches. The pulse increases and becomes weaker or thready. Blood pressure declines, and the skin of the extremities becomes mottled, cool, and dusky. Respirations become shallow and irregular. There may be pooling of secretions in the lungs that causes respirations to sound moist. Often at the time of death, a “death rattle” of those secretions occurs. Cheyne-Stokes respirations may be noted: respirations that gradually become shallower and are followed by periods of apnea (no breathing). Body temperature may rise, and the patient (if responsive) may complain of feeling hot or cold, although the extremities will be cool to the touch as circulation slows. Blankets should be used as the patient desires.

PSYCHOSOCIAL AND SPIRITUAL ASPECTS OF DYING

As outlined in Kübler-Ross’ stages of coping with dying, it is hoped that the patient will have reached the stage of acceptance as death draws closer. It is during this time that the patient will talk about making funeral arrangements and “putting my affairs in order.” To die with closure is to say goodbye to those people and things that are important. It may also involve saying “I’m sorry, forgive me,” “I forgive you,” and “I love you.” It is a time when the patient may give to family and friends special memories or possessions. A life review can assist patients to tell their story and put their life in perspective. Assisting the patient to write or share his life story with significant others allows them to keep special memories of their loved one.

As individuals approach death, their spiritual needs take on greater importance. As patients ponder the meaning of their life, their beliefs about what happens to them in death take on new meaning. Religious practices and rituals have great significance for some patients. It is important for you to be familiar with those beliefs (see Chapter 14). Rather than impose your own religious beliefs on dying patients and family, you should assist patients to find comfort and support in their own belief systems. An assessment of the spiritual needs of the patient is outlined in Chapter 14, and when indicated, you may collaborate with the patient’s religious representative or hospital chaplain to provide spiritual care.

As life ebbs, the patient becomes less verbal and more withdrawn. Everyday activities and news are not of interest, and nonverbal communication becomes most important. Sitting with patients and using touch, such as holding their hand or stroking their hair, will be most meaningful. Even when patients appear to be sleeping or nonresponsive, physical touch and presence are comforting. Always be aware of remarks you make in the presence of an unresponsive patient because they DO hear. Hearing is believed to be one of the last senses to be lost before death, and “dying” patients have awakened to report conversations by family and health care workers that they were not meant to overhear.

Dying patients may exhibit confusion and disorientation. They may report dreams or visions of deceased relatives, and they usually are not frightened by these experiences. Often this is comforting, and they may speak of preparing for a journey to join loved ones. At times patients may become restless and agitated. Adequate pain and anxiety medication can ease the distress of these symptoms. Keep soft lights on in the room. Assurance that it is “okay to go” and that family members will take care of each other may ease dying individuals’ anxiety about leaving their responsibilities.

LEGAL AND ETHICAL ASPECTS OF LIFE AND DEATH ISSUES

The health care system is still grappling with care of the dying. Recognizing the patient’s right to make decisions about end-of-life situations, advance directives, and the designation of a health care proxy have gained legal and public acceptance.

ADVANCE DIRECTIVES

An advance directive spells out patients’ wishes for health care at that time when they may be unable to indicate their choice. A durable power of attorney for health care is a legal document that appoints a person (health care proxy) chosen by the patient to carry out his wishes as expressed in an advance directive. Discussing advance directives with patients opens the communication path to establish what is important to them, and what they view as promoting life versus prolonging dying. Patients determine under which situations they would agree to do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. Their choices regarding artificial feeding and fluids, ventilators, and administration of antibiotics are documented.

Much of the debate in health care today deals with end-of-life decisions such as euthanasia, assisted suicide, adequate pain control, and death with dignity. Nurses must be active in keeping up to date on legal decisions regarding these issues, and continue to learn and apply new nursing theory and procedures regarding end-of-life care. They must also deal with their own feelings and values regarding patient choices to seek life-prolonging or death-seeking treatment.

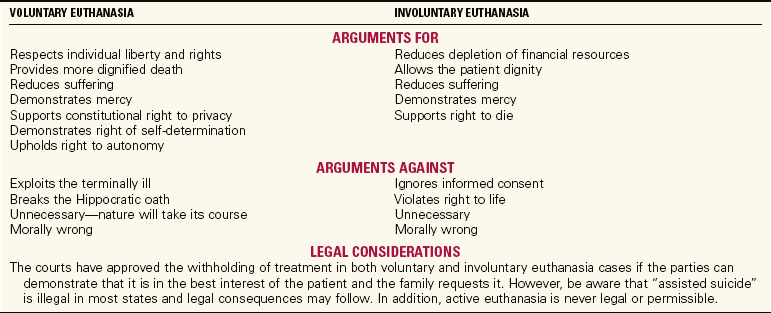

EUTHANASIA

Euthanasia is the act of ending another person’s life to end suffering, with (voluntary) or without (involuntary) his consent. It may be called “mercy killing.” Some distinction is also made between active and passive euthanasia. Passive euthanasia occurs when a patient chooses to die by refusing treatment that might prolong life. An example would be withholding artificial feeding or parenteral (IV) fluids when the patient is unable to take them orally. It would also include not treating pneumonia with antibiotics. Honoring the refusal of life-prolonging treatment of a patient with a terminal illness is legally and ethically permissible. Active euthanasia is generally defined as administering a drug or treatment to end the patient’s life. Active euthanasia is not legal or permissible in the United States. The arguments for legal and ethical considerations regarding euthanasia are presented in Table 15-3.

Assisted suicide is distinguished from active euthanasia. It is making available to patients the means to end their life (such as a weapon or drug) with knowledge that suicide is their intent. Both active euthanasia and assisted suicide are considered to be a violation of the American Nurses Association’s Code for Nurses. Their position statements regarding active euthanasia state that “the nurse does not act deliberately to terminate the life of any person” (American Nurses Association, 1994, p. 2) and that “nurses must …not participate in assisted suicide” (American Nurses Association, 1995, p. 6).

Assisted suicide has generated a great deal of debate and dialogue in health care as nurses witness firsthand the despair, pain, and debilitation of their patients. Assisting the patient’s death may be seen as a compassionate and humane response. Although an individual case may be compelling, there is a larger potential for abuse of this solution for difficult care problems, especially for the elderly, the disabled, and the poor. Oregon passed a law legalizing assisted suicide in 1998. However, the courts in other states continue to decide cases involving assisted suicide and active euthanasia that may change the legal status of such acts.

ADEQUATE PAIN CONTROL

Adequate pain control is another issue that affects the comfort of the dying and has to do with the reluctance of physicians to prescribe large enough doses of pain medication for fear of legal action under the Controlled Substances Act. There is also concern that they may be viewed as prescribing lethal doses in an assisted suicide effort. National legislation (the Lethal Drug Abuse Prevention Act of 1998) had been proposed to prevent physicians from prescribing controlled substances for the purpose of assisting suicide. The bill failed. If passed into law, it could have had a negative effect on the physician’s willingness to prescribe adequate pain medication.

Nurses must be advocates for compassionate end-of-life care. Knowledgeable and skillful symptom management, the relief of suffering, and the promise of presence, of not abandoning the patient, become the cornerstones of end-of-life care that can eliminate the need for a person to choose euthanasia or suicide.

ORGAN AND TISSUE DONATION

Kidneys, livers, hearts, and lungs are organs that can be transplanted from one person to another. Other tissues such as corneas, bone, and skin can also be transplanted. The need for organs and tissues exceeds the supply. Every day people die waiting for a transplant. People can indicate their wish to be donors on their driver’s license or in advance directives, but permission to remove the organs or tissues of a dead person must be given by the next of kin. Organs such as hearts, lungs, and livers can only be obtained from a person who is on mechanical ventilation and has suffered brain death but still has perfusion to the organs. Other tissues can be removed for several hours after death, such as after a massive heart attack or stroke. The donor must be free of infectious disease and cancer. The criteria are set by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). Physicians are usually the people to request organ donation from family members, but you may be in a position to answer questions the family raises about organ donation. You should know that donation of organs does not delay funeral arrangements, that there is no obvious evidence that the organs were removed when the body is dressed, and there is no cost to the family for the removal of organs donated.

POSTMORTEM (AFTER DEATH) CARE

When the patient stops breathing, the heart may continue to beat for several minutes. (It is when the heart stops that death is said to have occurred, unless the person is on a ventilator.) When a patient is being mechanically ventilated, brain death must be established to determine death. In a hospital or nursing home, a physician is usually designated as the person responsible for pronouncing the death. However, in some institutions midlevel providers, such as physician assistants and nurse practitioners, may perform this function. When a patient dies at home, the pronouncement of death may be delegated to an undertaker, registered nurse, or coroner. A coroner is a person with legal authority to determine cause of death. Any deaths that occur under suspicious circumstances are investigated by a coroner. These would include deaths that result from injury, accident, murder, or suicide. Any death within 24 hours after admission to the hospital, during surgery, or death of a person who has not been under a physician’s care, is reported to the coroner. In the health care setting, if a death is a coroner’s case, no tube or line is removed from the body to prevent removal of evidence of wrongdoing. IV lines and associated tubing are simply cut, tied off, and the catheters left in place.

A death certificate is completed by the physician, the undertaker, and a pathologist if an autopsy is done. An autopsy is an examination of the body, organs, and tissues to determine the cause of death. Consent for autopsy must be obtained from the next of kin, except in a coroner’s case, when no permission is needed.

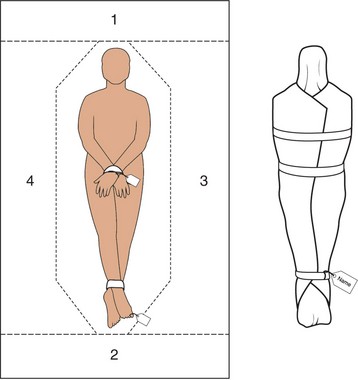

As the nurse, you are responsible for postmortem (after death) care of the body. Family members may wish to assist with or perform the preparation of the body as their last service to the patient, especially if they have been present throughout the dying process. If family members were not present when the patient died, the body may be prepared for the family to come to say goodbye and for removal to the morgue or undertaker (Skill 15-1). It is comforting for the family to have you indicate such things as “he died very peacefully,” and to explain the final care the patient received. Ask if the family wishes to be left alone with the body for their final goodbyes. You should return any personal belongings of the patient to the family, especially jewelry or valuables. The family members’ reactions become your focus, and a private quiet place should be provided for them to begin the grieving process until they are able to leave. Unused drugs are returned to the pharmacy according to agency policy. Unused drugs are never given to the family. It is not recommended to flush the drugs down the toilet.

Nurses can gain a great deal of satisfaction in caring for the dying patient and his family. Helping patients to attain their goal of dying with dignity, without pain, and with a sense of closure is a tremendous challenge, but one that is rewarding. You should realize that you will also grieve for the dying patient. Many hospitals and health care agencies provide for support sessions after a particularly difficult death or when a unit has a succession of unexpected or challenging losses. You will need to take care of yourself in order to continue taking care of your patients, and this includes recognizing the normal feelings that occur with loss, and allowing yourself to move through the grief rather than trying to avoid it. Talking with the chaplain, co-workers, and other experienced nurses can support and heal the grief. Seeking professional assistance may be indicated if grieving becomes dysfunctional.

NCLEX-PN® EXAMINATION–STYLE REVIEW QUESTIONS

Choose the best answer(s) for each question.

1. A patient who has been recently diagnosed with cancer says to the nurse, “If I can just live until my son graduates from college, I’ll donate 10% of my estate to the church.” The patient is in a stage described by Dr. Kübler-Ross as:

2. A therapeutic response the nurse could make when a patient says, “I don’t want to die” is:

1. “I’m sure you don’t want to die.”

2. “You have an excellent physician, maybe you won’t die.”

4. “I’m sorry you are going through this; would you like to talk about it?”

3. A clinical sign that a patient is close to death would be:

1. nausea that occurs after meals.

2. pain that is well controlled with small doses of morphine.

4. Comfort care for a terminally ill patient would include:

1. a magnetic resonance image (MRI) to determine if metastases were causing bone pain.

2. use of medication to relieve nausea.

3. insertion of an intravenous line to provide fluids.

4. a gastrostomy tube to provide nutrition when the patient is unable to eat normally.

5. The priority of palliative care is to:

1. control symptoms and promote comfort without the hope of cure.

2. prevent the recurrence of cancer when it is first diagnosed.

3. control costs of terminal illness by avoiding expensive treatments or drugs.

4. keep the patient at home rather than in a hospital or nursing home.

6. Validation of loss can be of great comfort to a grieving individual. A patient states, “I am so depressed! I didn’t know it would be so difficult to cope after losing my mother.” To validate the loss, you respond:

1. “Yes, but time is a great healer and you will eventually adjust.”

2. “I am sorry you are having such a hard time. Tell me a little about your mother and what she meant to you.”

7. Certain cultures believe that talking about bad things like “death” can bring it on. Your patient is an American Indian with advanced breast cancer whose family is at her bedside. The family has asked that you only discuss plans for a cure, and not discuss palliative measures. How do you plan for the patient’s care during the final stages of her illness?

1. You ignore end-of-life issues and continue to treat the patient for a cure, even though the treatment is painful.

2. You discuss palliative measures with the family, being careful to discuss “comfort” and not “death.”

3. Tell the family that their family member cannot receive hospice care if she does not know about her impending death.

4. If the family asks you questions, refer them to the physician.

8. An assigned patient has prostate cancer and is declining rapidly. He is frightened by the progression and asks you if there is any hope. What is your response?

1. “Your prostate cancer is incurable. We have exhausted our treatment measures, but I can discuss comfort measures with you.”

2. Would you like me to call a chaplain for you? Maybe it’s time to put your trust in a higher power.”

3. “There is always hope. Let’s look at how we can address your issues together. What is it that you are hoping for at this point?”

4. “You cannot give up! A positive attitude helps effect a cure.”

9. A patient with terminal cancer has accepted his impending death and so has his family. They have asked for palliative care. You know that this involves:

1. moving the patient to a hospice because that is the only place palliative care is appropriate.

2. keeping the patient in the hospital, which is the only place he can receive pain medicine in large doses.

3. moving the patient home, where he can be in familiar surroundings, even though his access to medicines and nursing care will be limited.

4. helping the patient and his family arrange for a setting that is comfortable to them.

10. After receiving palliative care for several months, your patient has died. The family is feeling deep grief. You feel saddened also, and you know that:

1. crying is inappropriate because you are not even a family member or a close friend.

2. it is appropriate for you to shed some tears also, allowing yourself to move through the grief rather than trying to avoid it. You may also need to seek professional assistance.

3. you need to ignore your feelings and stay strong for the family so you can provide better nursing care.

4. you should avoid the family and allow them to grieve in private. You are no longer needed, and your presence just reminds them of their loss.

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES ? Read each clinical scenario and discuss the questions with your classmates.

Lynn Nuñez, a 45-year-old woman with advanced breast cancer that has spread to her lungs and bones, is admitted to your unit for terminal care and palliation. She has draining sores on her left breast. She is experiencing a great deal of pain when she moves, but she does not want to be “sedated.” Her wish is to spend her last days with her family, which includes her husband, mother and father, and two teenage daughters. The family is close and supportive, but is having a very hard time seeing Lynn suffer. She is Roman Catholic, and the parish priest has visited daily. She has indicated she does not wish to have extraordinary measures, including feeding tubes, IVs, or antibiotics. She is DNR.

1. What would you think are Lynn’s prioritized needs for care?

2. If she were assigned to you for care, what do you think you might suggest for

• Frequency of vital signs measurement

• Personal care: bathing, mouth care, skin care

3. What might your response be if Lynn were to ask you, “Why do I have to suffer like this?”