Inflammatory bowel disease

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are the two types of chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract which together are termed ‘inflammatory bowel disease’ (IBD). This common terminology conceals many differences in predisposition and pathogenesis between the two conditions. It is also likely that within each category there are different individual disease phenotypes.

Ulcerative colitis is a disorder that is confined to the mucosa and submucosa, with inflammation usually confined to the large bowel, although when the whole of the colon is involved there can also be inflammation in the terminal ileum. The extent of colonic involvement varies, but the rectum is always involved and mucosal inflammation is continuous, not patchy. Symptoms include bloody diarrhoea, fever and weight loss. Ulcerative colitis can be associated with extracolonic manifestations such as uveitis, sacroiliitis and various skin disorders (Box 34.1).

Crohn's disease is a transmural granulomatous condition that can involve any part of the gut. The bowel involvement is discontinuous and segmental, most frequently found in the terminal ileum and colon but often sparing the rectum. Fistula formation, small-bowel strictures and perianal disease such as abscesses and fissures are common. Clinical features of colonic involvement include diarrhoea, abdominal pain and fatigue. Involvement of more proximal parts of the gut produces various symptoms depending on the site of the disease, and diarrhoea need not be present (Box 34.1).

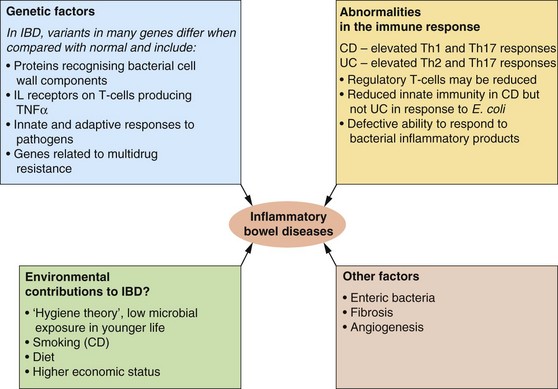

The aetiologies of IBD are unclear, although several susceptibility genes have been identified (Fig. 34.1). The genetic predisposition is stronger in Crohn's disease, but both conditions can occur in the same families. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of Crohn's disease and the frequency of exacerbations, but slightly decreases the risk of ulcerative colitis. The trigger for disease in susceptible individuals is unknown but a failure of development of immune tolerance in the gut may be important, and IBD may arise from impaired handling of microbial antigens by the intestinal immune system. Cells involved in innate immunity contribute to the inflammation, including natural killer T-cells, neutrophil leucocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells. These secrete tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) and a variety of pro-inflammatory interleukins and chemokines. The abnormal immune response also involves an excess number of adaptive immune cells. In Crohn's disease these are T-helper type 1 (Th1) lymphocytes while in ulcerative colitis they are T-helper type 2 (Th2) lymphocytes, leading to different patterns of cytokine release (Ch. 38). T-helper type 17 (Th17) lymphocytes are also involved in the pathogenesis of both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Regulatory T-cells are probably deficient. There is a close interaction between the immune system and the enteric nervous system that contributes to initiation and maintenance of inflammation, motility disturbance in the bowel and pain. Inflammatory bowel disease can undergo periods of relapse and remission over many years.

Fig. 34.1 Factors associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

Investigations into the aetiology of inflammatory bowel disease have confirmed the multiplicity of factors that might be involved. The association of some events is strong while others are weak. Some changes may occur as a consequence of the disease rather than being involved in the cause. CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL, interleukin; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Treatment of both types of IBD is intended to induce and maintain remission. The drugs used for these two conditions are broadly similar, but Crohn's disease is less responsive to some of the widely used drugs, especially when it involves the small intestine. Better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms in IBD has resulted in advances in treatment, although much still needs to be learned.

Drugs for inflammatory bowel disease

Mechanism of action and effects

The active anti-inflammatory constituent of all the aminosalicylates is 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA). The different aminosalicylate drugs are formulated in a variety of ways, but they are all designed to deliver 5-ASA to the lumen of the colon (see Pharmacokinetics). Sulfasalazine was the first aminosalicylate shown to be effective in treating IBD. Colonic bacteria cleave sulfasalazine into its constituent parts: 5-ASA and sulfapyridine. Sulfapyridine is responsible for many of the unwanted effects of this drug, but in contrast to its role in inflammatory arthritis (Ch. 30) it has no therapeutic value in IBD. The mechanisms of action of aminosalicylates are not clear, but they may involve inhibition of leucocyte chemotaxis by reducing cytokine formation, reduced free radical generation and inhibition of the production of lipid inflammatory mediators (such as prostanoids, leukotrienes and platelet-activating factor). Aminosalicylates are increasingly used as first-line prophylaxis of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis, and are highly effective for reducing relapse rates. Their efficacy in Crohn's disease is less well established, particularly for non-colonic disease. They are less effective in treatment of acute exacerbations of IBD.

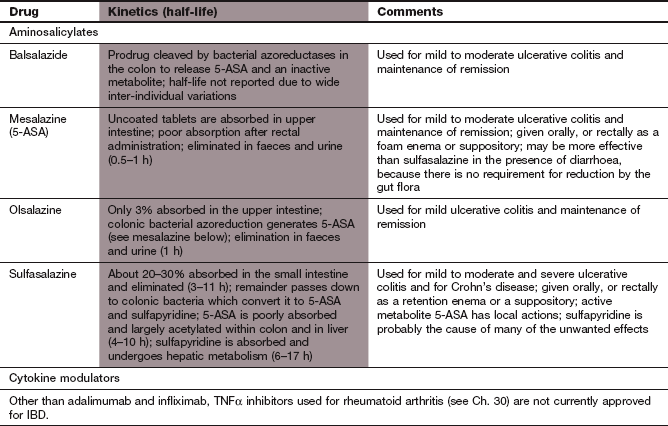

Pharmacokinetics

Sulfasalazine is partially absorbed from the gut intact, but most reaches the colon, where it undergoes reduction by gut bacteria to sulfapyridine and 5-ASA. Sulfapyridine and about 20% of the 5-ASA are absorbed from the colon, and then metabolised in the liver. Both have plasma half-lives of 5–20 h. There are several ways of delivering 5-ASA to the mucosa of the lower gut without also giving sulfapyridine. Mesalazine (the 5-ASA molecule itself) is given as an enteric-coated or modified-release formulation to limit absorption from the small bowel and deliver adequate drug to the colon. Olsalazine is a drug comprising two 5-ASA molecules joined by an azo bond. It is not absorbed from the upper gut and 5-ASA is released after reductive splitting of the azo bond by colonic flora. Balsalazide is a prodrug in which 5-ASA is linked to a carrier molecule (4-amino-benzoyl-β-alanine) by an azo bond, which is cleaved by bacterial reduction in the large bowel.

Mesalazine and sulfasalazine can be given rectally (by suppository or enema) to treat distal disease in the colon.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids (Ch. 44) are very effective for inducing remission in active IBD; however, there is little evidence that they prevent relapse when used at doses that do not produce significant unwanted effects. Newer corticosteroids formulated for topical use, such as budesonide (see also Ch. 44), have limited systemic unwanted effects and are useful alternatives to the older drugs. Topical treatment with liquid or foam enemas or suppositories is used for localised rectal disease, but oral or parenteral administration is needed for more severe or extensive disease.

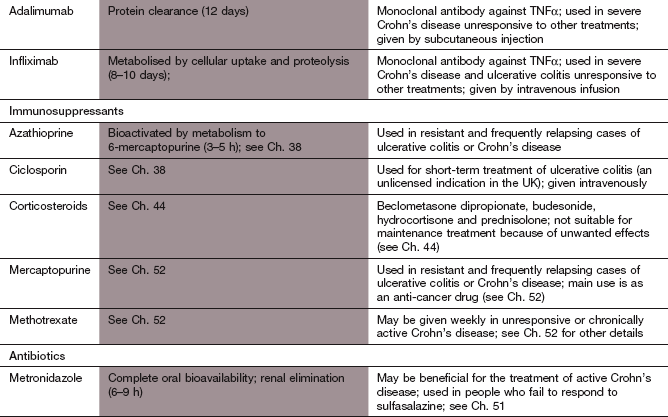

Cytokine inhibitors (ANTI-TNFα antibodies)

Mechanisms and uses

Infliximab was the first monoclonal antibody to be approved for the treatment of Crohn's disease. Adalimumab is effective when infliximab is poorly tolerated or for those who have become refractory to treatment. Inhibition of the binding of TNFα to its receptors reduces production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1 and IL-6), leucocyte migration and infiltration, and activation of neutrophils and eosinophils. Infliximab may also be useful for treatment of severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Unwanted effects of TNFα antibodies are discussed in Chapter 30.

Immunosuppressants

Azathioprine and, less often, mercaptopurine are useful in some people with active IBD and may enable corticosteroid doses to be reduced. Mercaptopurine is more frequently used in North America; it may be a little less effective than azathioprine but perhaps with a lower rate of nausea. Maximal efficacy is not achieved with either drug for about 6–12 weeks. Nausea, vomiting, rashes and a hypersensitivity syndrome affect about 10% of people during the first 6 weeks of therapy. Pancreatitis and liver toxicity are rare but serious complications.

Methotrexate is useful in Crohn's disease. It is given subcutaneously or intramuscularly and is only used when azathioprine has failed. Ciclosporin can induce remission in corticosteroid-resistant ulcerative colitis but has no long-term efficacy. More details of these drugs are found in Chapter 38.

Antibacterials

Metronidazole (Ch. 51) is moderately effective for treatment of some aspects of Crohn's disease, particularly perianal disease, although the mechanism of action is uncertain. Ciprofloxacin probably has similar efficacy.

Management of inflammatory bowel disease

Treatment is determined by the extent and severity of disease. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and also selective cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors (Ch. 29) can exacerbate symptoms in severe colitis and should not be used. Opioids (Ch. 35) should be avoided in the treatment of diarrhoea in extensive colitis since they can precipitate the life-threatening complication toxic megacolon.

Rectal drug delivery is often successful if the disease is limited to the rectum or left side of the colon (distal colitis). For mild symptoms, topical mesalazine is more effective than topical corticosteroid. Foam enemas or suppositories will treat inflammation up to 12–20 cm from the anus, while liquid enemas are effective up to 30–60 cm (i.e. to the splenic flexure). Oral aminosalicylate can be combined with rectal administration to improve efficacy. For more severe disease an oral corticosteroid may be necessary to induce remission, with gradual dosage reduction to minimise unwanted effects once control is achieved.

More extensive colitis will settle with an oral aminosalicylate if symptoms are mild to moderate, but the response can take 6–8 weeks. Oral corticosteroids such as prednisolone induce remission more quickly. Severe colitis requires intensive fluid and electrolyte replacement; anaemia should be corrected by transfusion, and large doses of parenteral corticosteroid should be given. Infliximab can be used for severe refractory disease. Surgery is required in about 20% of people with ulcerative colitis.

Once symptoms are quiescent, maintenance treatment with topical mesalazine or an oral aminosalicylate should be life-long and reduces the relapse rate by two-thirds. It also reduces the risk of developing colorectal cancer by up to 75%.

The indications for immunosuppressants in the treatment of ulcerative colitis are the same as for Crohn's disease (see below). Azathioprine is the only immunosuppressant agent with a good evidence base for long-term therapy of ulcerative colitis. Intravenous ciclosporin may induce remission in refractory cases.

Crohn's disease

Smoking cessation reduces the risk of relapse in Crohn's disease by 65%, an effect comparable in size to that achieved with an immunosuppressant. Corticosteroid therapy is the mainstay of medical treatment for active Crohn's disease, usually with oral prednisolone. Maintenance corticosteroid therapy does not reduce the risk of relapse, and every effort should be made to withdraw the drug once the disease activity has been controlled. Immunosuppressant drugs such as azathioprine may be useful to aid this process, especially in chronically active Crohn's disease, where corticosteroid dependence occurs in 40–50% of people who take the drug to induce remission. Azathioprine should be considered if control of Crohn's disease requires more than two 6-week courses of oral corticosteroid therapy per year, or if the disease relapses as the dose of corticosteroid is reduced. Azathioprine can also be used to induce remission. Methotrexate can induce and maintain remission in Crohn's disease, but is usually used when there is intolerance to azathioprine or mercaptopurine. Intramuscular or subcutaneous injections may be more effective than oral methotrexate due to greater bioavailability.

Disease confined to the distal colon can respond to topical therapy with a corticosteroid, and an oral aminosalicylate such as mesalazine can also have a modest benefit in colonic Crohn's disease (see management of ulcerative colitis, above). For Crohn's disease outside the colon, aminosalicylates are generally ineffective.

The antibacterial drugs ciprofloxacin and metronidazole are particularly useful for perianal disease. They probably have both an antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effect. Infliximab or adalimumab are used to induce and maintain remission in Crohn's disease that is resistant to conventional therapy. A single infusion can induce remission in Crohn's disease for up to 3 months, and subsequent intermittent 2-monthly maintenance infusions can reduce the severity of the disease. Antibody formation, which may cause allergic reactions and/or loss of efficacy, is less likely to occur with this regimen, and can be further reduced by corticosteroid pretreatment and maintenance immunosuppressant therapy.

Surgery may be necessary for disease that is refractory to medical therapy. Intestinal obstruction can require bowel resection, or abscesses may need drainage. A defunctioning ileostomy to ‘rest’ the bowel may allow active inflammation to settle with medical therapy in refractory disease, but colonic disease usually recurs after closure of the stoma. Surgery should be an integral part of the management plan, and is required in up to 80% of people with Crohn's disease.

True/false questions

1. Crohn's disease lesions are transmural and confined to the small bowel.

2. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of Crohn's disease.

3. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) the main active constituent of sulfasalazine is sulfapyridine.

4. Mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid; 5-ASA) can be given rectally.

5. Mesalazine is equally useful in the treatment of Crohn's disease involving the colon or the small bowel.

6. Corticosteroids are effective for maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis.

7. Immunosuppressants such as azathioprine are ineffective for the treatment of Crohn's disease.

8. Infliximab can induce remission even in refractory IBD.

9. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided in IBD.

10. Diarrhoea in IBD can be treated with the opioid loperamide.

One-best-answer (OBA) question

Choose the most accurate statement concerning IBD drugs from A–E below.

A 5-Aminosalicylic acid given orally or rectally is well absorbed.

B Balsalazide comprises two molecules of 5-ASA joined by an azo bond.

C Azathioprine is the first-line drug of choice in treating mild Crohn's disease.

D Adalimumab is an antibody directed against interleukin-6.

E Metronidazole can be used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease.

Case-based questions

A 35-year-old man presented with a 3-week period of frequent diarrhoea with mucus but no blood in the stool. Stool analysis for infective agents was negative. Sigmoidoscopy indicated gross thickening of the mucosa, with inflammation and linear ulcers. Changes were present in restricted areas (skip lesions) with intervening normal mucosa. Histology was diagnostic of Crohn's disease and investigation suggested that the condition was confined to the sigmoid and part of the ascending colon.

A What is the cause of Crohn's disease?

B How should this man be treated initially?

C How do corticosteroids act in Crohn's disease?

D How should the corticosteroid be given, and why?

E Why should the corticosteroid dosage be reduced slowly at the end of treatment?

F How can remission be maintained in this man?

G What alternative therapies can be given to try to reduce the risk of corticosteroid dependence?

1. False. Crohn's disease is transmural but can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract.

2. True. There is increased risk of Crohn's disease in smokers but a slightly decreased risk of ulcerative colitis.

3. False. Sulfasalazine is broken down in the colon to 5-ASA, which is responsible for the beneficial effects in IBD, and sulfapyridine, which causes most of the unwanted effects.

4. True. Modified-release formulations of mesalazine are available for rectal administration to deliver the drug to the distal colonic mucosa.

5. False. Although mesalazine may be of some benefit in colonic Crohn's disease, it is not very effective for small-bowel Crohn's disease.

6. False. Although they are effective for inducing remission, there is little evidence that corticosteroids prevent relapse.

7. False. People with chronic Crohn's disease can become corticosteroid-dependent, and immunosuppressants such as azathioprine can be useful in reducing this dependence. Many months of treatment are required before they are fully effective.

8. True. A single infusion of infliximab can induce remission for up to 3 months; remission may be maintained by further infusions at 2-monthly intervals.

9. True. NSAIDs and selective cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors (coxibs) can exacerbate symptoms in severe disease.

10. False. Opioids should be avoided as they can precipitate toxic megacolon.

OBA answer

Answer E is the most accurate.

A Incorrect. 5-ASA is poorly absorbed by either route and acts locally within the gut.

B Incorrect. The 5-ASA dimer is olsalazine, while balsalazide is a molecule of 5-ASA linked to an inert carrier molecule; in both cases the active 5-ASA is released by colonic bacterial reduction.

C Incorrect. Azathioprine is usually given in corticosteroid-refractory disease or when people are having frequent courses of corticosteroids for treatment (more than two 6-week courses per year).

D Incorrect. Adalimumab is a fully humanised monoclonal antibody against TNFα and is given subcutaneously for the treatment of refractory disease.

E Correct. Antibacterials such as metronidazole can be useful in treating Crohn's disease, particularly if there is perianal disease.

Case-based answers

A The cause of Crohn's disease is unknown. Several hypotheses have implicated a number of risk factors, including infection, altered immune response to infection and environmental factors (see Fig. 34.1).

B Initial treatment is with corticosteroids. Because the Crohn's disease is confined to the distal colon, topical treatment with a corticosteroid such as budesonide could be used to limit systemic unwanted effects. If, however, there was involvement of the proximal large bowel or small bowel it would be necessary to give an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisolone.

C Corticosteroids have a variety of actions. They can alter the release of inflammatory mediators such as arachidonic acid metabolites, kinins and cytokines. They can alter cell-mediated cytotoxicity, antibody production, adhesion molecule expression, phagocytic function, leucocyte chemotaxis and leucocyte adherence.

D Corticosteroids should be given until remission occurs. If possible, the corticosteroid should be administered locally to keep the plasma concentration low, but for individuals who experience systemic symptoms of IBD (such as fatigue, anorexia or weight loss) oral therapy is indicated.

E Systemic corticosteroids suppress the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis and can reduce the circulating levels of endogenous adrenal glucocorticoids (see Ch. 44). Gradual reduction of the dose of therapeutic corticosteroid allows recovery of the production of endogenous glucocorticoids.

F If the colitis is restricted to the distal colon, topical administration of mesalazine or an oral formulation that delivers 5-ASA to the colon could be used. 5-ASA is, however, less effective in Crohn's disease, particularly if it involves the small bowel.

G Continuous corticosteroid therapy for periods of 6 months or longer is eventually required in 40–50% of people with Crohn's disease. If more than two 6-week courses of corticosteroid per year are required to maintain control of symptoms, immunosuppressive therapy should be considered. Immunosuppressive therapy is usually with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine; prolonged treatment with these drugs is usually required (up to 6 months) before a clinical response occurs. TNFα antibody treatment is also of benefit in severe disease that is not responsive to other therapies.

Baumgart, DC, Sandborn, WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657.

Collins, P, Rhodes, J. Ulcerative colitis: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2006;333:340–343.

Cummings, JFR, Keshav, S, Travis, SPL. Medical management of Crohn's disease. BMJ. 2008;336:1062–1066.

Katz, JA. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:65–71.

Mowat, C, Cole, A, Windsor, A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607.

Panés, J, Gomollón, F, Taxonera, C, et al. Crohn's disease: a review of current treatment with a focus on biologics. Drugs. 2007;67:2511–2537.

Peyrin-Biroulet, L, Desreumaux, P, Sandborn, WJ, et al. Crohn's disease: beyond antagonists of tumour necrosis factor. Lancet. 2008;372:67–81.

Scaldaferri, F, Fiocchi, C. Inflammatory bowel disease: progress and current concepts of etiopathogenesis. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:171–178.