Constipation, diarrhoea and irritable bowel syndrome

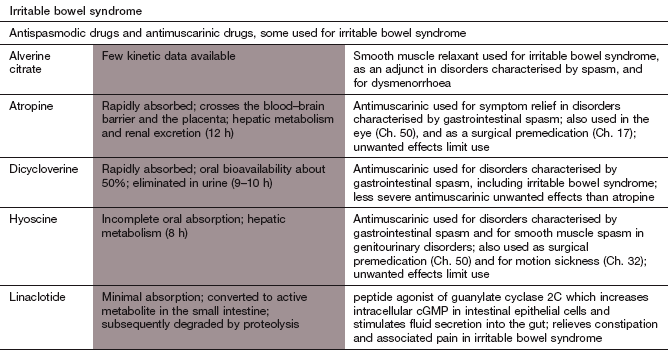

Constipation

Humans normally defaecate with a frequency ranging from three times a day to once every 3 days (or sometimes less often). Maintenance of ‘regular’ bowel habits is a preoccupation of Western societies, and is best achieved by increasing dietary fibre. Nevertheless, laxative drugs are widely prescribed or taken without prescription and are frequently abused.

Frequent constipation affects 10% of the population, and is the passage of hard, small stools less frequently than the patient's own normal function and is often associated with straining. There are many causes (Box 35.1). Underlying organic disease should be excluded when there is persistent constipation or if there has been a recent change in bowel habit.

Laxatives

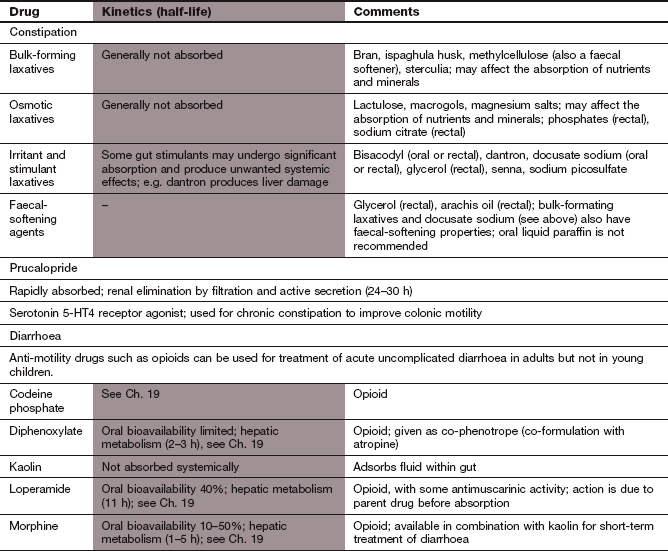

The mechanisms of action of common laxatives are shown in Figure 35.1. Some drugs have more than one mechanism, and they are classified by their principal action.

Fig. 35.1 Sites of action of the major classes of laxative drug.

Some laxative drugs have more than one mechanism of action. CCK, cholecystokinin.

Bulk-forming laxatives

Bulking agents include various natural polysaccharides, usually of plant origin, such as unprocessed wheat bran, ispaghula husk, sterculia and methylcellulose, all of which are poorly broken down by digestive processes. They have several mechanisms of action:

a hydrophilic action causing retention of water in the gut lumen, which expands and softens the faeces,

a hydrophilic action causing retention of water in the gut lumen, which expands and softens the faeces,

proliferation of colonic bacteria, which further increases faecal bulk,

proliferation of colonic bacteria, which further increases faecal bulk,

stimulation of colonic mucosal receptors by the increased bulk, promoting peristalsis,

stimulation of colonic mucosal receptors by the increased bulk, promoting peristalsis,

sterculia also contains polysaccharides which are degraded to substances that have an osmotic laxative effect.

sterculia also contains polysaccharides which are degraded to substances that have an osmotic laxative effect.

Bulking agents take at least 24 h after ingestion to work. A liberal fluid intake is important to lubricate the colon and minimise the risk of obstruction. Bulking agents are useful for establishing a regular bowel habit in chronic constipation, diverticular disease and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but they should be avoided if the colon is atonic or there is faecal impaction.

Unwanted effects include a sensation of bloating, flatulence or griping abdominal pain.

Osmotic laxatives

Magnesium compounds such as the sulphate (Epsom salts) and the hydroxide are poorly absorbed from the gut and act as osmotically active solutes that retain water in the colonic lumen. They may also stimulate cholecystokinin release from the small-intestinal mucosa, which increases intestinal secretions and enhances colonic motility (Fig. 35.1). These actions result in more rapid transit of gut contents into the large bowel, where distension promotes evacuation within 3 h. About 20% of ingested magnesium is absorbed and inhibits central nervous system, cardiovascular and neuromuscular activity if it is retained in the circulation in large enough amounts, as can occur in renal failure. Magnesium hydroxide is a mild laxative, while the action of magnesium sulphate can be quite fierce, associated with considerable abdominal discomfort.

Lactulose is a disaccharide of fructose and galactose. In the colon, bacterial action releases fructose and galactose, which are fermented to lactic and acetic acids with release of gas. The fermentation products are osmotically active. They also lower intestinal pH, which favours overgrowth of some selected colonic flora but inhibits the proliferation of ammonia-producing bacteria. This is useful in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy (Ch. 36). Unwanted effects include flatulence and abdominal cramps. Lactulose can take more than 24 h to act.

Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) are large, inert molecules that are not absorbed from the gut and exert an osmotic effect in the colon. They are as effective as other osmotic agents, but their Na+ content may be hazardous for people with impaired cardiac function.

Sodium acid phosphate and sodium citrate are osmotic preparations that are given as an enema or suppository, usually for bowel preparation before local procedures or surgery.

Irritant and stimulant laxatives

Irritant and stimulant laxatives include the anthraquinones senna and dantron, and the polyphenolic compounds bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate. They act by a variety of mechanisms, including stimulation of local reflexes through myenteric nerve plexuses in the gut, which enhances gut motility and increases water and electrolyte transfer into the lower gut. Stimulant laxatives are useful for more severe forms of constipation, but tolerance is common with regular use and they can produce abdominal cramps. Given orally, they stimulate defecation after about 6–12 h.

Senna has the most gentle purgative action of this group. Given orally, it is hydrolysed by colonic bacteria to release the irritant derivatives sennosides A and B.

Senna has the most gentle purgative action of this group. Given orally, it is hydrolysed by colonic bacteria to release the irritant derivatives sennosides A and B.

Dantron is available as co-danthramer, a combination with the surface wetting agent poloxamer 188, and as co-danthrusate, a combination with the mildly stimulant and faecal-softening agent docusate (see below). Dantron is carcinogenic at high doses in animals, and it is recommended that its use in humans should be limited to the elderly or terminally ill.

Dantron is available as co-danthramer, a combination with the surface wetting agent poloxamer 188, and as co-danthrusate, a combination with the mildly stimulant and faecal-softening agent docusate (see below). Dantron is carcinogenic at high doses in animals, and it is recommended that its use in humans should be limited to the elderly or terminally ill.

Bisacodyl can be given orally or, for a more rapid action (15–30 min), rectally; it undergoes enterohepatic circulation.

Bisacodyl can be given orally or, for a more rapid action (15–30 min), rectally; it undergoes enterohepatic circulation.

Sodium picosulfate is a powerful irritant and is given orally to prepare the bowel for surgery or colonoscopy. It generally acts in less than 6 h.

Sodium picosulfate is a powerful irritant and is given orally to prepare the bowel for surgery or colonoscopy. It generally acts in less than 6 h.

Docusate sodium has some stimulant activity as well as detergent properties which may soften stools by increasing fluid and fat penetration into hard stool. It is a relatively ineffective laxative that is given rectally or orally.

Docusate sodium has some stimulant activity as well as detergent properties which may soften stools by increasing fluid and fat penetration into hard stool. It is a relatively ineffective laxative that is given rectally or orally.

The chronic use of stimulant laxatives has been suspected to cause progressive deterioration of normal colonic function, with eventual atony (‘cathartic colon’). It is now recognised that the condition probably arises from severe, refractory constipation rather than from the treatment.

Faecal softeners

Arachis oil can be given rectally to soften impacted faeces. Other drugs with faecal-softening actions include bulk-forming laxatives and docusate sodium. Liquid paraffin can be given orally, but is not recommended since it impairs the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and can cause anal seepage with anal pruritus, and lipoid pneumonia after accidental inhalation.

Management of constipation

For simple constipation adopting a high-fibre diet, supplemented by bulking agents when necessary, is recommended. Exercise and an adequate fluid intake are also important. For short-term use, a stimulant laxative such as senna or bisacodyl can be taken orally at night to give a morning bowel action. Suppositories will give a more rapid effect. For longer-term therapy, regular magnesium salts or macrogols are usually well tolerated and effective.

Senna, magnesium salts and docusate appear to be safe in pregnancy. Bisacodyl, co-danthramer and co-danthrusate are suitable for the elderly or for the terminally ill with opioid-induced constipation. For opioid-induced constipation in terminal care, the peripheral opioid receptor antagonist methylnaltrexone can be added if laxatives are ineffective (Ch. 19). Lactulose is useful as a second-line agent and specifically to treat constipation associated with hepatic encephalopathy (Chs 36 and 56). For people in whom neurological disease affecting bowel motility is the cause of constipation, a faecal softener should be used, with regular enemas or rectal washouts.

Refractory idiopathic constipation is a condition almost exclusively found in women, starting at a young age. Long-term use of stimulant laxatives, often at high dosage, may be necessary. Bulk-forming laxatives are ineffective, and a high-fibre diet usually increases abdominal distension and discomfort. Prucalopride, a 5-HT4 receptor agonist (see compendium) is sometimes used for refractory chronic constipation. Biofeedback can help in up to 80% of people with the condition. For those who fail with these approaches, surgical intervention with colectomy may be the only option.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is frequent watery bowel movements, with or without gas and cramping. Severe acute diarrhoea is usually a result of gastrointestinal infection, and it can be the consequence of both reduced absorption of fluid and an increase in intestinal secretions. Viral gastroenteritis is much more common than bacterial causes of diarrhoea in children, but viral and bacterial causes are both important in adults. Traveller's diarrhoea is a particularly common problem because of exposure of the traveller to organisms which have not been encountered before. Common causes include enterotoxin-producing Escherichia coli, Clostridium jejuni and Salmonella and Shigella species. Parasites such as Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium species and Cyclospora cayetanensis are less commonly involved. Diarrhoea may result from local release of bacterial enterotoxins, which have a variety of actions on gut mucosal cells, including stimulation of intracellular cAMP synthesis, which causes excess Cl− secretion into the bowel.

Drugs that can produce diarrhoea include magnesium salts (see above), cytotoxic agents (Ch. 52), α- and β-adrenoceptor antagonists (Chs 5 and 6) and broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs, which produce diarrhoea by altering colonic flora (Ch. 51). Antibacterial treatment can be associated with Clostridium difficile colitis.

Chronic diarrhoea requires full investigation for non-infectious causes such as carcinoma of the colon, inflammatory bowel disease and coeliac disease. Irritable bowel syndrome is often accompanied by increased frequency of defaecation, loose stool and a sensation of incomplete evacuation (see below).

Drugs for treating diarrhoea

The anti-motility action of opioids is a result of binding to µ-receptors on neurons in the submucosal neural plexus of the intestinal wall (Ch. 19). This enhances segmental contractions in the colon, inhibits propulsive movements of the small intestine and colon and prolongs the transit time of intestinal contents. These actions provide the opportunity for prolonged contact of intestinal contents with the gut mucosa and enhanced absorption of fluids.

The opioids most often used to treat diarrhoea are codeine, loperamide and diphenoxylate (used in combination with atropine as co-phenotrope). Most have short half-lives (<5 h). Loperamide has a more rapid onset of action, and a longer half-life (11 h), giving it a longer duration of action. It is more selective for the gut because high first-pass metabolism limits systemic absorption and, in contrast to other opioids, dependence is not a problem. Loperamide has additional antimuscarinic activity that also inhibits peristalsis (also achieved by atropine in co-phenotrope) and it increases anal tone. Morphine is sometimes used to treat diarrhoea in combination with kaolin (see below), but is not generally recommended. Unwanted effects of opioid drugs are discussed in Chapter 19.

Adsorbent and bulk-forming agents

Kaolin is an adsorbent that is relatively ineffective, and is not recommended for the treatment of acute diarrhoea. Ispaghula, methylcellulose and sterculia are bulking agents that can help to control faecal consistency in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, or for people with an ileostomy or colostomy. They are not recommended for treatment of acute diarrhoea.

Management of diarrhoea

In developed countries, most people with acute infective diarrhoea who are otherwise fit generally require only high oral fluid and electrolyte intake. Fluid and electrolyte balance are particularly important in young children and the elderly, as they can dehydrate more quickly. Specially formulated powders containing electrolytes (particularly Na+ and K+) and glucose (to enhance electrolyte absorption) are available (oral rehydration therapy, ORT). When correctly reconstituted with clean water they provide a balanced rehydration solution that should be given rapidly over 3–4 h, and then continuing need reassessed. Intravenous fluids may be required in severe dehydration.

If drug treatment is required, an opioid is useful for mild to moderate diarrhoea. Opioids should be avoided in dysentery, when prolonging contact of the organism with the gut mucosa can be detrimental. In young children, ileus with severe abdominal distention can occur with opioids, and it is recommended that they are not used in this age group.

Antibacterial prophylaxis can be used to prevent traveller's diarrhoea in people visiting high-risk areas. Ciprofloxacin or azithromycin are most often recommended (Ch. 51), depending on the area to which the person is travelling. Alternatively, an antibacterial can be taken at the first sign of illness, and it will usually shorten the duration of the attack to less than 24 h. Ciprofloxacin is often recommended for empirical treatment if there is fever or bloody diarrhoea to suggest invasive disease (such as produced by Campylobacter or Shigella species). If these are not present then rifaximin, a non-absorbable antimicrobial, can be used.

Diarrhoea in inflammatory bowel disease should be treated by management of the underlying condition. Antidiarrhoeals should not be used in active inflammatory bowel disease because of the risk of precipitating toxic megacolon (see Ch. 34).

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea

Antibacterial-induced diarrhoea usually resolves rapidly on stopping the provoking drug. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea produces more prolonged and severe diarrhoea. Any broad-spectrum antibacterial can promote colonisation with C. difficile in the colon, but cephalosporins, penicillins and clindamycin are the most frequent causes. C. difficile colonisation does not necessarily produce symptoms, which arise from toxin production by the bacteria. The diagnosis is confirmed by detection of toxin in the stool. C. difficile-associated diarrhoea fails to settle with conservative treatment in 80% of cases, and can produce fatal colitis. Treatment with oral metronidazole or alternatively oral vancomycin should be given (Ch. 51).

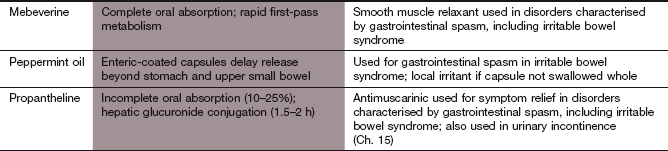

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is said to occur in 15% of the population. It is characterised by abdominal distension, bloating and alteration in bowel habit. There are two overlapping clinical presentations: constipation-predominant and diarrhoea-predominant. Abdominal discomfort may be relieved by defecation, but there is a sensation of incomplete evacuation and mucus is often passed per rectum. The cause is unknown, but a generalised motor and/or sensory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract is likely. A strong psychological component is also evident and the brain–gut axis is thought to play an important role.

Confirming the diagnosis of IBS involves exclusion of more serious bowel pathology. Screening should include inflammatory markers, coeliac disease immunology and excluding anaemia, which may indicate alternative diagnoses. Faecal calprotectin (a marker of inflammatory bowel disease) may also be part of a screening workup.

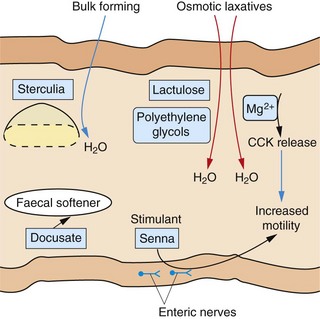

Drugs for treating irritable bowel syndrome

Mechanism of action: Antimuscarinic drugs reduce colonic motility by inhibiting parasympathetic stimulation of the myenteric and submucosal neural plexuses. They also inhibit gastric emptying.

Other antispasmodic agents

Mechanism of action: These antispasmodic agents have direct smooth muscle-relaxant properties (possibly by phosphodiesterase inhibition). They can relieve gut spasm and the associated pain.

Management of irritable bowel syndrome

Drug therapy should form only part of the treatment of IBS, supplemented by cognitive behavioural therapy, relaxation and hypnotherapy where appropriate. Hypnotherapy is effective in up to 60% of people, but should be given by a properly trained therapist. Reductions in tea and coffee consumption and smoking, and modification of diet, may be helpful.

Constipation can be treated with bulking agents such as ispaghula husk or, if colonic transit time is very prolonged, an osmotic laxative may be effective. Lactulose is not recommended. Linaclotide, is a guanylate cyclase 2C agonist (see compendium) that activates the enzyme on the luminal surface of intestinal epithelial cells and increases anion and fluid secretion. It is used to reduce abdominal pain in refractory constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Loperamide is the first-choice drug for diarrhoea because it has a rapid onset of action and enables people to control their bowels, particularly when out of their normal environment or in other circumstances where diarrhoea would be socially disruptive. Care has to be taken with other opioids because of the risks of dependency and opioid-induced abdominal pain. Regular use of small doses of a laxative or antidiarrhoeal drug may be preferable to intermittent use. The non-absorbable antibacterial rifaximin can reduce symptoms in diarrhoea-predominant IBS.

Treatments for diarrhoea in IBS do not usually reduce the abdominal pain. There may be benefit from antispasmodic agents or a low-dose of a tricyclic antidepressant for analgesic effect (Ch. 19). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are only recommended if a tricyclic antidepressant is ineffective (Ch. 22). Proton pump inhibitors (Ch. 33) may relieve diarrhoea by reducing the gastro-colic reflex.

Overall, current treatment of IBS is unsatisfactory. Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (for diarrhoea-predominant IBS) and 5-HT4 receptor agonists (for constipation-predominant IBS) are available in some countries, but currently not in the UK.

True/false questions

1. Constipation is when defaecation is less frequent than once daily.

2. Most cases of simple constipation can be treated by lifestyle changes.

3. Chronic intake of senna causes progressive hyperactivity of colonic motility.

4. Antacids containing aluminium salts can cause constipation.

5. Laxatives invariably induce bowel movements within 6 h.

6. Diarrhoea can be largely of psychological origin in some people.

7. In infants (<2 years) diarrhoea is mainly caused by bacterial infection.

8. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs may cause pseudomembranous colitis.

9. The use of antibacterial drugs to treat acute episodes of diarrhoea is rarely necessary.

10. Oral rehydration powders are reconstituted to give a hypertonic solution.

One-best-answer (OBA) questions

1. Choose the correct statement below concerning laxatives.

A Bulk laxative use should be accompanied by drinking plenty of water.

B Magnesium sulphate inhibits cholecystokinin release.

C Lactulose acts by stimulating the enteric nerves.

2. Which of the following statements about diarrhoea is incorrect?

A Rotavirus is an uncommon cause of diarrhoea in adults.

B Kaolin is not recommended for acute diarrhoea.

C Campylobacter jejuni is a common cause of bacterial gastroenteritis in the UK.

D Loperamide decreases the gut residence time of the infective organism.

E Antibacterial drugs can be used prophylactically for traveller's diarrhoea.

1. False. Normal bowel habit varies widely, with defaecation between three times daily and once every 3 days (or longer) regarded as normal.

2. True. Increased fibre intake and exercise help most cases of ‘simple’ constipation.

3. False. Chronic use of senna has been associated with loss of colonic function and damage to the myenteric plexus (cathartic colon), but it is now thought to be due to the refractory constipation itself rather than to inappropriate use of stimulant laxatives.

4. True. Aluminium salts cause constipation, as do other drugs including opioid analgesics, calcium channel blockers and some antidepressants.

5. False. Some laxatives (such as magnesium salts) can act within 6 h, whereas others including lactulose and docusate take considerably longer to exert their activity.

6. True. There is a psychological component to diarrhoea and other symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome, which may respond to counselling or hypnotherapy.

7. False. Viral gastroenteritis, especially rotavirus, is the major cause of infant diarrhoea.

8. True. Broad-spectrum antibacterials may cause colitis due to overgrowth of the anaerobe Clostridium difficile; it is treated with metronidazole or vancomycin.

9. True. In developed countries antibacterial drugs are rarely necessary for acute diarrhoea in otherwise healthy individuals; fluid and electrolyte replacement are appropriate.

10. False. The osmotic action of a hypertonic solution would draw water into the bowel, exacerbating diarrhoea; oral rehydration solution should be isotonic or slightly hypotonic.

OBA answers

A Correct. Adequate water intake is necessary to hydrate bulk-forming laxatives.

B Incorrect. Magnesium sulphate is an osmotic laxative that also induces cholecystokinin release, stimulating enteric nerves.

C Incorrect. Lactulose is an osmotic laxative.

D Incorrect. Aluminium salts can cause constipation.

E Incorrect. The bulk-forming laxative sterculia takes more than 24 h to act.

2. Answer D is the incorrect statement.

A Correct. Rotavirus causes diarrhoea in young children but very rarely in adults.

B Correct. Kaolin is an adsorbent with limited effectiveness.

C Correct. C. jejuni is one of the commonest causes of gastroenteritis in adults in developed countries.

D Incorrect. Loperamide inhibits gut contractility by its opioid and antimuscarinic actions, and this may increase the residence of invasive organisms.

E Correct. Ciprofloxacin or co-trimoxazole can be used prophylactically in travellers to high-risk areas.

DuPont, HL. Bacterial diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1560–1569.

Ford, AC, Talley, NJ. Irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ. 2012;345:e5836.

Kelly, CP, LaMont, JT. Clostridium difficile – more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932–1940.

Lembo, A, Camilleri, M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360–1368.

Mayer, EA. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1692–1699.

Spiller, R. Clinical update: irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2007;369:1586–1588.

Spiller, R, Aziz, Q, Creed, F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–1798.

Thielman, NM. Acute infectious diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:38–47.

Thomas, J, Karver, S, Cooney, GA. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. New Engl J Med. 2008;358:2332–2343.

Wald, A. Appropriate use of laxatives in the management of constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:410–414.