Disorders of the skin

Introduction

Only a small proportion of skin disorders is surgically important. These include unsightly lesions, lumps and possible malignant lesions. Ulcers of the lower limb are common and usually of vascular or diabetic neural and/or ischaemic origin. Some venous ulcers are managed by dermatologists, but many are managed by surgeons and specialist nurses; these are discussed in Chapter 43. Ulceration is also a characteristic of many malignant skin lesions.

The initial referral is usually made to a dermatologist but skin disorders still comprise about 15% of new outpatient general surgical referrals. Many require only excision biopsy under local anaesthesia. Others patients are referred for advice after a skin lesion has been excised by a family practitioner.

A small proportion has a potentially sinister course, particularly malignant melanoma which must be accurately diagnosed and treated. Suspected malignant skin lesions are often managed jointly by dermatologists or surgeons (including plastic surgeons) and oncologists.

Malignant melanomas comprise only 2% of skin cancers in Northern Europe but, like basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas, their incidence correlates with sun exposure and fair skin. Skin malignancies and premalignant stages are much more common in sunny countries like Australia where they have reached epidemic proportions; also the frequency of all skin cancers is rising with increasing foreign travel.

Finally, the nails, which are specialised skin appendages, pose surgical problems in the form of infected ingrowing toenails and onychogryphosis. The rare subungual melanoma is an important diagnosis which must not be missed.

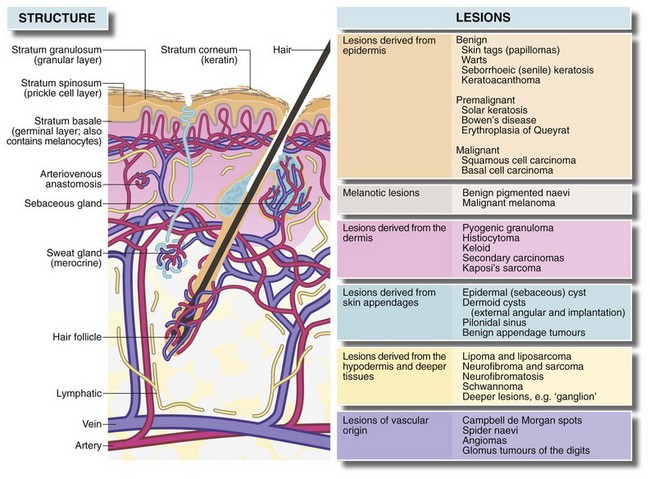

Structure of normal skin (Fig. 46.1)

The skin has three main layers, epidermis, dermis and hypodermis:

• The epidermis has four layers—basal, prickle-cell, granular and keratin. Cell division normally occurs only in the basal layer

• The dermis consists of dense, tough interlacing collagen fibres; their orientation determines lines of skin tension known as Langer's lines. These are surgically important because incisions parallel to them heal with minimal scarring

• The deepest layer of the skin is the hypodermis, consisting of loose fibro-fatty tissue and containing skin appendages—sweat glands, hair follicles and associated sebaceous glands. The skin is generally mobile over deeper structures because the hypodermis is only loosely connected to the superficial fascia, but is tightly bound to fascia in the palms, the soles of the feet and the scalp.

Symptoms and signs of skin disorders

The most common complaint is a lump. This may be tender or painful, and it may bleed, discharge or ulcerate. The lesion may be pigmented or have changed colour. It may have appeared suddenly or enlarged rapidly, or a longstanding lesion may have changed. Another reason for surgical referral is hyperhidrosis or excessive sweating.

The most frequent patient complaint is the ugliness or inconvenience of a lesion (e.g. in the way of a strap). Elderly patients often come reluctantly at the insistence of younger relatives. Some present late when a lesion is huge, while others present with trivial lesions. Either may fear malignancy.

In practice (and in clinical exams) skin lesion diagnosis rarely follows the pattern of history, examination and investigation. Rather, the lesion is thrust before the doctor's eyes and a ‘spot’ or differential diagnosis is made. History and examination then help confirm the diagnosis or narrow the possibilities. Table 46.1 summarises the clinical features of skin lesions and their diagnostic significance.

Table 46.1

Symptoms and signs of skin disorders

| Symptoms and signs | Diagnostic significance |

| 1. Lump in or on the skin Size, shape and surface features Revealed by inspection—is the lesion smooth-surfaced, irregular, exophytic (i.e. projecting out of the surface)? |

Epidermal lesions such as warts usually have a surface abnormality but deeper lesions are usually covered by normal epidermis. A punctum suggests the abnormality arises from an epidermal appendage, e.g. epidermal (sebaceous) cyst |

| Depth within the skin Superficial and deep attachments Which tissue is the swelling derived from? |

Tends to reflect the layer from which lesion is derived and therefore the range of differential diagnosis (i.e. epidermis, dermis, hypodermis or deeper) |

| Character of the margin Discreteness, tethering to surrounding tissues, three-dimensional shape |

A regular shaped, discrete lesion is most likely cystic or encapsulated (e.g. benign tumour). Deep tethering implies origin from deeper structures (e.g. ganglion). Immobility of overlying epidermis suggests a lesion derived from skin appendage (e.g. epidermal cyst) |

| Consistency Soft, firm, hard, ‘indurated’, rubbery |

Soft lesions are usually lipomas or fluid-filled cysts. Most cysts are fluctuant unless filled by semi-solid material (e.g. epidermal cysts), or the cyst is tense (e.g. small ganglion) Malignant lesions tend to be hard and irregular (‘indurated’) with an ill-defined margin due to invasion of surrounding tissue Bony-hard lesions are either mineralised (e.g. gouty tophi) or consist of bone (e.g. exostoses) |

| Pulsatility | Pulsatility is usually transmitted from an underlying artery which may simply be tortuous or may be abnormal (e.g. aneurysm or arteriovenous fistula) |

| Emptying and refilling | Vascular lesions (e.g. venous malformations or haemangiomas) empty or blanch on pressure and then refill |

| Transilluminability | Lesions filled with clear fluid such as cysts ‘light up’ when transilluminated |

| Temperature | Excessive warmth implies acute inflammation, e.g. pilonidal abscess |

| 2. Pain, tenderness and discomfort | These symptoms often indicate acute inflammation. Pain also develops if a non-inflammatory lesion becomes inflamed or infected (e.g. inflamed epidermal cyst). Malignant lesions are usually painless |

| 3. Ulceration (i.e. loss of epidermal integrity with an inflamed base formed by dermis or deeper tissues) | Malignant lesions and keratoacanthomas tend to ulcerate as a result of central necrosis. Surface breakdown also occurs in arterial or venous insufficiency (e.g. ischaemic leg ulcers), chronic infection (e.g. TB or tropical ulcers) or trauma, particularly in an insensate foot |

| Character of the ulcer margin | Benign ulcers—the margin is only slightly raised by inflammatory oedema. The base lies below the level of normal skin Malignant ulcers—these begin as a solid mass of proliferating epidermal cells, the centre of which eventually becomes necrotic and breaks down. The margin is typically elevated ‘rolled’ and indurated by tumour growth and invasion |

| Behaviour of the ulcer | Malignant ulcers expand inexorably (though often slowly), but may go through cycles of breakdown and healing (often with bleeding) |

| 4. Colour and pigmentation Normal colour |

If a lesion is covered by normal-coloured skin then the lesion must lie deeply in the skin (e.g. epidermal cyst) or deep to the skin (e.g. ganglion) |

| Red or purple | Redness implies increased arterial vascularity, which is most common in inflammatory conditions like furuncles. Vascular abnormalities which contain a high proportion of arterial blood such as Campbell de Morgan spots or strawberry naevi are also red, whereas venous disorders such as port-wine stain are darker. Vascular lesions blanch on pressure and must be distinguished from purpura which does not |

| Deeply pigmented | Benign naevi (moles) and their malignant counterpart, malignant melanomas, are nearly always pigmented. Other lesions such as warts, papillomata or seborrhoeic keratoses may become pigmented secondarily. Hairy pigmented moles are almost never malignant. Rarely, malignant melanomas may be non-pigmented (amelanotic). New darkening of a pigmented lesion should be viewed with suspicion as it may indicate malignant change |

| 5. Rapidly developing lesion | Keratoacanthoma, warts and pyogenic granuloma may all develop rapidly and eventually regress spontaneously. When fully developed, these conditions may be difficult to distinguish from malignancy. Spontaneous regression marks the lesion as benign |

| 6. Multiple, recurrent and spreading lesions | In certain rare syndromes, multiple similar lesions develop over a period. Examples include neurofibromatosis and recurrent lipomata in Dercum's disease. Prolonged or intense sun exposure predisposes a large area of skin to malignant change. Viral warts may appear in crops. Malignant melanoma may spread diffusely (superficial spreading melanoma) or produce satellite lesions via dermal lymphatics |

| 7. Site of the lesion | Some skin lesions arise much more commonly in certain areas of the body. The reason may be anatomical (e.g. pilonidal sinus, external angular dermoid or multiple pilar cysts of the scalp) or because of exposure to sun (e.g. solar keratoses or basal cell carcinomas of hands and face) |

| 8. Age when lesion noticed | Congenital vascular abnormalities such as strawberry naevus or port-wine stain may be present at birth. Benign pigmented naevi (moles) may be detectable at birth, but only begin to enlarge and darken after the age of 2 |

History and examination

As the patient describes the problem, the lesion is usually offered for examination which may guide the direction and emphasis of history taking. The patient should be questioned about sun exposure and about other similar lesions or any regional lumps. Detailed inspection and palpation follow, leading to a diagnosis or narrow differential diagnosis.

A general history must be taken to ascertain any relevant systemic symptoms (e.g. weight loss), concurrent disorders (e.g. diabetes predisposes to infection and influences surgical management), a history of previous similar lesions, surgical treatment or trauma to the area. For example, a history of rodent ulcers (basal cell carcinoma) makes this diagnosis more likely next time. Previous surgery or trauma can lead to implantation epidermoids or a chronic inflammatory response to a foreign body.

Family history is valuable in rare genetic disorders such as neurofibromatosis and tuberous sclerosis. Social history should include occupational details. For example, natal cleft pilonidal sinus is more common in truck drivers. Exposure to carcinogens such as lubricating oils persistently spilt on clothing may cause squamous carcinoma. Outdoor workers, especially in the tropics, are predisposed to all skin cancers. Chronic ulcers may be contracted during foreign travel, e.g. tropical ulcers, Madura foot, tuberculous or atypical mycobacterial ulcers. Patients sometimes deliberately injure themselves, producing odd chronic ‘artefactual’ lesions; a psychiatric history is valuable here, though rarely forthcoming.

Drug history is rarely relevant, though agents applied topically, e.g. silver nitrate stick, caustic agents and contact dermatitis to adhesive dressings can distort the clinical picture. Check if the patient is taking warfarin or aspirin since they may increase the risk of perioperative haemorrhage.

The lesion is examined in detail, looking for the points in Table 46.1. General clinical examination searches for other similar lesions, regional lymphadenopathy or a primary malignancy arising elsewhere and metastasising to skin. For example, if inguinal lymph nodes are enlarged, rectal and genital examination should be carried out to exclude concealed carcinoma. The lower limbs, including the soles of the feet, should also be examined for malignant melanoma.

Principles of managing skin lesions

Many skin lesions can be diagnosed from the history and clinical examination, but where there is doubt, biopsy is needed, particularly if there is risk of malignancy. Excision biopsy is treatment if the lesion is small. Incision and excision biopsy techniques are illustrated in Chapter 10, p. 136 and Box 46.1 summarises surgical options for skin conditions.

For axillary hyperhidrosis, the most effective and least risky option is injections of botulinum toxin into axillary skin. This needs to be repeated at 6–9-monthly intervals. Local excision of axillary sweat glands is another popular surgical option. For palmar hyperhidrosis unresponsive to dermatological management, thoracoscopic destruction of upper thoracic sympathetic nerves is highly effective.

Lesions originating in the epidermis

Skin tags (squamous cell papillomas)

Skin tags are small benign polypoid lesions up to 5 mm across consisting of loose connective tissue covered by normal, often pigmented, keratinised epithelium. Common in adults, they may occur anywhere, particularly the trunk, neck, axillae and groins; they may be irritated by clothing and bleed. Lesions are easily removed by cryotherapy (freezing), cautery or excision (under local anaesthesia), or by tying a fine thread around the stalk (also under local anaesthesia) which leads to ischaemic atrophy.

Warts

Warts are small, virus-induced epidermal tumours characterised pathologically by irregular thickening of the epidermis with excessive keratinisation and exaggerated dermal papillae. The morphology depends on the location.

The common wart (verruca vulgaris), a papilliferous lesion up to 1 cm in diameter, is most often found on the fingers and back of the hands. In children, warts are often multiple and can occur on the face. Facial lesions are often less keratotic with a smoother, more dome-like shape. They are often called juvenile or plane warts (verruca plana juvenilis). Lesions on the sole of the foot, plantar warts (verruca plantaris), become very keratotic and flattened by pressure. They may extend deeply into the foot, causing pain. Warts may also occur on the genitalia, perineum and perianal area. These originate with papilloma virus infection and are usually spread by sexual contact. Genital warts sometimes grow to a large size and are then known as condylomata acuminata.

Warts are frequently seen in immune-suppressed patients. They grow and regress spontaneously over several months, but often require treatment to relieve pain, irritation or inconvenience or for aesthetic reasons. Keratolytic applications (salicylic acid or podophyllin resin preparations), cryosurgery (liquid nitrogen application) or topical imiquimod are often the first choice of treatment. If unsuccessful, electrocautery (with or without curettage) and simple excision can be used.

Seborrhoeic keratosis

Seborrhoeic keratoses (seborrhoeic warts) are very common in elderly patients but occasionally appear in younger people (Fig. 46.2). They are most common on the trunk, face, neck and arms, often with many different sized lesions with varying pigmentation. They may be up to several centimetres in diameter. The lesions are slightly raised, sharply demarcated and plaque-like; they look and feel irregular and waxy. Darkly pigmented lesions cannot be distinguished clinically from superficial spreading malignant melanomas.

Histologically, a seborrhoeic keratosis is a localised proliferation of the epidermal basal layer. There is often hyperkeratosis in surface crypts, resulting in round keratin nests. Seborrhoeic keratoses are sometimes called basal cell papillomas, but are not true neoplasms and are unrelated to basal cell carcinoma.

Treatment is only required for unsightly or easily traumatised lesions. As they are so superficial, they can be ‘scraped off’ with a curette or scalpel under local anaesthesia. Cryotherapy is used but caution is needed in patients with dark skin, since enthusiastic cryotherapy can lead to permanent loss of pigmentation.

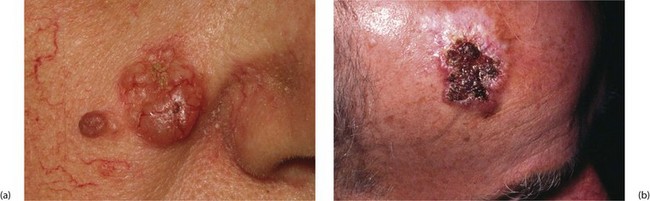

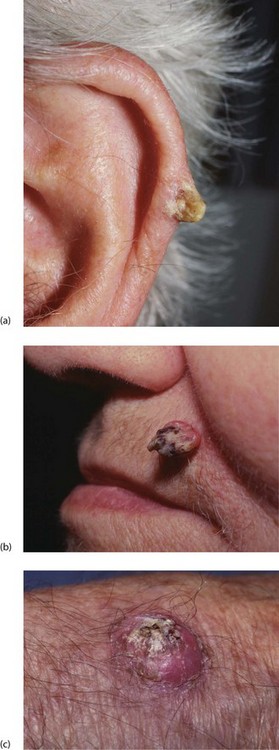

Keratoacanthoma

Keratoacanthoma is a nodular, single skin lesion, up to 2 cm across (Fig. 46.3b, c). They have an irregular central crater containing keratotic debris. The histological lesion consists of localised tumour-like epidermal proliferation, with a thick prickle cell layer (acanthosis) and marked keratinisation. Some epithelial cells are large with atypical nuclei; the underlying dermis exhibits chronic inflammatory cell infiltration.

Fig. 46.3 Keratin horn and keratoacanthoma

(a) Keratin horn on the pinna of an elderly man. If untreated, these can grow large.

(b) This alarming looking lesion is a benign keratoacanthoma. The central keratin plug is characteristic. Resolution is spontaneous after a few weeks.

(c) Similar lesion on the back of the hand. Squamous and basal cell carcinoma need to be excluded

This benign lesion can be difficult to distinguish clinically or even histologically from squamous carcinoma. Keratoacanthomas, however, have a short life cycle, appearing rapidly and regressing spontaneously over 2–3 months, whereas squamous carcinomas continue to enlarge. Keratin horns may look similar but rarely regress. The cause is unknown but its behaviour suggests a viral origin.

Diagnosis and treatment is by local excision unless the lesion is obviously regressing. If there is diagnostic doubt, the patient should be followed up as for squamous carcinoma.

Melanotic lesions

Benign naevi: Deeper layers of the epidermis contain scattered melanocytes that synthesise melanin which is transferred to nearby epidermal cells where it is responsible for skin colour. Melanocyte concentration is similar in all races but pigmentation depends on the quantity of melanin produced. Although skin colour is determined mainly by genetic factors, it is enhanced by exposure to ultraviolet rays of sunlight (tanning).

Melanocytes originate from the neural crest and migrate to ectoderm during embryological development. Hamartomatous accumulations of melanocytes in the epidermis or dermis or both form raised, variably pigmented lesions known as naevi or moles.

Lesions range from about 3 to 30 mm in diameter. The surface may be smooth or irregular and may contain hairs. According to clinical and histological features, naevi can be subdivided into five types: junctional, intradermal, compound, blue and Spitz or spindle cell (juvenile) naevi. The first three are closely related pathologically. Their main surgical importance is distinguishing them from malignant melanoma.

Lentigo: Lentigines (the plural of lentigo) are benign pigmented lesions that feature in the differential diagnosis of melanotic lesions. They are large, heavily pigmented patches on the face and hands of the elderly. Melanocytes are numerous, and melanin production is excessive but there is no accumulation of naevus cells. Lentigines are benign but predispose to superficial spreading malignant melanoma.

Management of pigmented lesions

People are more aware that pigmented lesions can be malignant, and large numbers now seek medical advice. Fortunately, only a small proportion has melanomas. With suspicion of malignancy, specialist dermatological opinion should be sought. A surgeon becomes involved if more than simple excision or biopsy is necessary.

It can be difficult to clinically differentiate different types of benign naevi, and to exclude malignancy; however, dermoscopy (dermatoscopy), i.e. examining the skin using surface microscopy, is useful in expert hands in distinguishing benign and malignant pigmented lesions. Note that if there is a recent change in a lesion or any doubt about its nature, excision biopsy is mandatory. In practice, if patient or doctor is worried about a pigmented lesion, no matter how benign it looks, it is usually removed. Lesions subject to chronic irritation (e.g. at the waist, neck or palm) or in a site that is difficult to observe (e.g. sole of foot or genitalia) should certainly be removed. A fusiform incision with a narrow margin of normal tissue (2–3 mm) removes the lesion, enabling the skin edges to be readily opposed. All excised pigmented lesions should be examined histologically because a few benign-looking lesions may turn out to be malignant.

Premalignant and malignant epidermal conditions

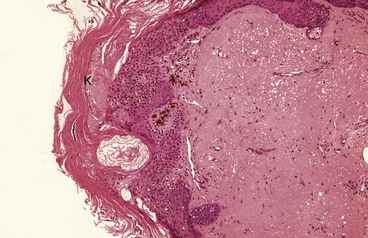

Solar (senile) keratosis and intra-epidermal carcinoma

Pathology and clinical features: Solar keratoses are flat, well-demarcated, brown, scaly or crusty lesions with an erythematous base (Fig. 46.4). They bleed easily if traumatised or scratched. Solar keratoses are often multiple and are most common in later life on sun-exposed parts such as face, neck, arms and hands. The incidence is higher in farm workers, fishermen and other outdoor workers. Solar keratoses are especially common in fair-skinned people living in tropical or subtropical regions like Australia or the southern USA.

Fig. 46.4 Solar keratosis—histopathology

Occurring in sun-exposed areas, this lesion typically shows thickening of the keratin layer K. Epidermal cells can show a range of atypia, which may amount to squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ. The dermis shows severe solar damage

Characteristic histological features are marked thickening of the keratin layer (hyperkeratosis) and prickle cell layer (acanthosis). There is a variable degree of dysplastic change and abnormal mitotic activity deep in the epidermis. These features suggest malignant transformation but, importantly, the basal layer remains intact.

The epidemiology and pathology of solar keratosis suggest it is a premalignant condition predisposing to squamous carcinoma. Lesions in which dysplastic changes extend from the basal layers to the surface (full thickness) are considered to be malignant and termed carcinoma-in-situ or intra-epidermal carcinoma. Clinically, these are larger and more erythematous than the common type and are described as Bowen's disease. Bowen's disease on the glans penis is known as erythroplasia of Queyrat.

Management: Management depends on number, size and distribution, age of the patient, and whether the skin type predisposes to cancer. Isolated lesions are best excised. For multiple keratoses, excision biopsy of representative lesions is performed initially to confirm the diagnosis, followed by topical 5-fluorouracil cream, diclofenac gel or imiquimod cream, or by excision biopsy, curettage or cryotherapy of suspicious lesions. Patients should be repeatedly advised to minimise exposure to UV rays by wearing protective clothing and hats and applying high factor total (UVA + UVB) sunscreen creams. Patients should be regularly examined for squamous cell carcinomas, basal cell carcinomas and melanomas, all more common with marked sunshine exposure.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Pathology: Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs, Fig. 46.5) occur anywhere on the skin or stratified squamous epithelium of the mouth, tongue, oesophagus, anal canal, glans penis or uterine cervix. Squamous cell carcinoma also occurs in metaplastic squamous epithelium in bronchus, oesophagus or bladder.

Fig. 46.5 Squamous carcinoma

(a) This 70-year-old farmer had worked in the fields exposed to the sun all his life. He presented with this obviously malignant lesion on the upper part of the pinna. It was confirmed on biopsy to be a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (b) after local resection

Skin SCCs usually occur in older age groups, in areas of skin exposed repeatedly to ultraviolet light. Often, they develop from pre-existing solar (senile) keratoses.

Rarely nowadays, squamous carcinoma develops in skin chronically exposed to industrial carcinogens such as ionising radiation, arsenic or chromium compounds, soot, tar, pitch or mineral oils. For example, carcinoma of the scrotum was common in chimney sweeps in the nineteenth century; recognising soot as the predisposing factor was a milestone in understanding carcinogenesis.

Chronic inflammation also predisposes to squamous carcinoma, which rarely develops at the margins of osteomyelitic sinuses or longstanding ulcers. These are common in developing countries where burns are poorly treated. A chronic burns ulcer in which carcinoma arises is known as a Marjolin's ulcer.

Histologically, squamous cell carcinomas of the skin are usually well differentiated, and tumour cells resemble normal prickle cells. Keratin pearls and individual cell keratinisation are common.

Clinical presentation: Squamous cell carcinoma usually presents as an enlarging painless ulcer with a rolled, indurated (hardened) margin. Other lesions have an exophytic (outward growing, proliferative) cauliflower-like appearance with areas of ulceration, bleeding or serous exudation. SCCs invade the dermis and deeper tissues such as bone or cartilage; further spread is usually to regional lymph nodes. Distant metastases are relatively uncommon.

Management of squamous cell carcinoma: Management involves first confirming the diagnosis by biopsy, then local radiotherapy or excision with a margin of normal tissue. For certain SCCs, including recurrences, at sites where conserving normal tissue is important for cosmetic or functional reasons, as well as for SCCs whose edges cannot be clearly defined, a special technique known as Mohs' micrographic surgery is often employed. Under local anaesthesia, this involves frozen section histology of sequential horizontal sections. If malignant cells remain, further sections are removed until clear of malignancy.

Infiltrated lymph nodes are treated with radiotherapy or sometimes block dissection (i.e. removing all regional nodes in a single block of tissue). In general, these tumours respond favourably to radiotherapy and recurrence is unusual.

Prognosis is less good for tumours larger than 2 cm, recurrent lesions, lesions arising in pre-existing scars, on the skin of the lips, ears and scrotum, and lesions with poor histological differentiation or perineural invasion. These patients are usually reviewed regularly for about 5 years after treatment.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

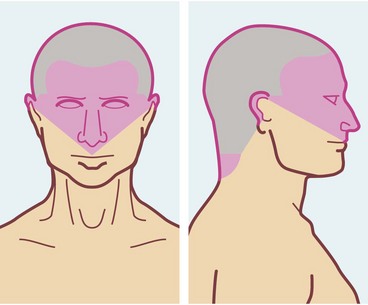

Pathology and clinical features: Basal cell carcinomas are common and nearly always result from exposure to excess ultraviolet in sunlight. White-skinned people in tropical and sub-tropical regions have an extremely high incidence, with up to 50% affected at some time, often with multiple lesions. As with SCCs, basal cell carcinomas usually develop from middle age onwards, but incidence is rising in younger ‘sun-worshippers’. Males are affected at least twice as often as females, reflecting greater occupational and recreational exposure to the sun.

Most BCCs arise on the upper part of the face (Figure 46.6), although any part of the skin can be involved. Most patients present early because lesions are so visible.

Basal cell carcinomas begin as small pearly-white nodules with visible telangiectatic blood vessels (Fig. 46.7). Early lesions may ulcerate, bleed and then heal again, but eventually they form irregular ulcers (rodent ulcers) with a pearly rolled margin. Although BCCs almost never metastasise they are definitely malignant, and will invade underlying bone and cartilage. Neglected lesions on the scalp or neck may even invade brain or spinal cord.

Histologically, tumour cells have strongly basophilic nuclei and little cytoplasm. Cells at the periphery are arranged in a palisade pattern reminiscent of normal basal cells.

Management of basal cell carcinomas: Small lesions are usually treated by cryotherapy without histology. Other treatments include topical chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod cream, local radiotherapy or 2–3 cycles of curettage combined with electrocautery. Excision biopsy may be appropriate for isolated or suspicious lesions. Radiotherapy must be used with caution on nose or ear where cartilage is susceptible to radiotherapy damage and may undergo necrosis. Larger destructive lesions usually require reconstructive plastic surgery involving skin grafts or flaps.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) employs topical methyl amino-levulinate cream and light therapy. The drug is selectively absorbed by cancer cells and converted into photoactive porphyrins. When cancer cells loaded with porphyrins are exposed to light of wavelength 570–670 nm, a molecular reaction destroys them. This selectively targets tumour cells whilst leaving normal cells unharmed. It is recommended for solar keratoses and basal cell carcinomas situated on the mid-face or ears, those on severely sun-damaged skin, particularly the lower legs of elderly patients, large lesions or recurrent lesions. Clinical trials have shown it gives cure rates at least as good as cryotherapy and surgery. It leaves minimal scarring and gives excellent cosmetic results.

As with squamous cell carcinomas, Mohs' micrographic surgery may be indicated for recurrent BCCs where conservation of normal tissue is important, or for BCCs where the edges cannot be clearly defined.

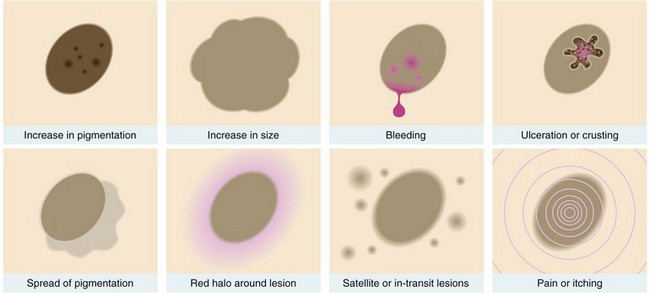

Malignant melanoma

Introduction and pathology: Malignant melanoma (Fig. 46.8) arises by malignant transformation of melanocytes. Most are poorly differentiated, with numerous mitotic figures, and the presence of melanin is diagnostic. Suspected amelanotic (non-pigmented) melanomas may need to be confirmed by immunohistochemical tests.

Malignant melanoma is a common cancer with the peak incidence in the fourth decade of life. World incidence is rising substantially and in the UK, diagnosed new cases rose by 50% between 1990 and 2000. In 2008 around 11 770 new cases were registered, compared with 98 800 non-melanoma skin cancers. There have been improvements in 5-year survival for melanoma patients from about 40% in the 1940s to about 80% now. In 2008 in the UK, 2560 people died from skin cancer, around 2070 from malignant melanoma.

In particular, melanomas of less than 1 mm Breslow thickness (see later) have a 95–100% 5-year survival rate. Improved survival is due to greater public awareness, earlier detection and better treatment.

Risk factors: The epidemiology of malignant melanoma is fascinating. About 80% occur in white-skinned people and the disease is extremely common in albinos of all races. Until recently, malignant melanoma was rare in northern Europe but the incidence has risen sharply over the last three decades. About 1 in 100 Americans will be affected some time in their lives. The highest incidence is in northern and western Australia and it is certain ultraviolet radiation is the essential aetiological factor. Whilst cumulative sun is the main factor for other skin malignancies, short periods of intense exposure causing blistering sunburn appear to be more important for malignant melanoma. There is evidence that unaccustomed exposure to strong sunlight can suppress general immunological responses and, by implication, immunological tumour surveillance. This might explain malignant melanomas on skin not generally exposed to the sun, for example the soles of the feet or anal canal.

Other risk factors include a family history of malignant melanoma, freckling of the upper back, red or blond hair, blue or green or grey eyes and the presence of solar (actinic) keratoses. Each of these factors increases risk by about 3.5 times.

Melanoma subtypes: Melanomas may be classified as growing radially (superficial spreading type) or vertically (nodular type). About 80% are the superficial spreading type. These grow slowly and usually arise in pre-existing pigmented naevi. Lesions are flat with a variegated border, often with patches of regression. Nodular melanomas are more common in men. They demonstrate an early vertical growth phase and develop more rapidly and behave more aggressively; they tend to arise in normal skin. Five per cent of nodular melanomas are amelanotic.

Lentigo maligna melanoma is uncommon and presents as large (< 3 cm) lesions on the face or neck of elderly women. It has a low metastatic potential but is locally invasive; it is distinct from lentigo maligna, its benign but precancerous counterpart.

Acral melanoma occurs on the palms or soles or under the nails. This is the only type found in dark-skinned individuals and has a low incidence in white people. They occur at a mean age of 60 (see Fig. 46.19 below). Malignant melanomas in less obvious areas have a reputation for aggressive behaviour but this may be because of late diagnosis.

Mucosal melanoma occurs on any mucosal surface from mouth to anus, pharynx or paranasal sinuses or vagina. They tend to behave aggressively. Ocular melanoma arises from uveal melanocytes and is the most common ocular malignancy. It is unique in metastasising to the liver, often years after treatment of the primary lesion.

Clinical features of malignant melanoma: Most malignant melanomas are black or dark brown, flat or nodular lesions which may bleed or ulcerate. If a pre-existing or new mole enlarges, darkens, bleeds or becomes inflamed, ulcerated or itchy, it should be regarded with great suspicion (see Fig. 46.9). Superficial spreading melanoma can easily be mistaken for a pigmented seborrhoeic keratosis. In general, spread to regional lymph nodes occurs early. Lateral spread in dermal lymphatics may produce satellite lesions around the primary nodule and ‘in transit’ lesions may appear along the course of the lymph node drainage.

Haematogenous spread occurs later, involving lung, liver, bone, brain and other tissues. Behaviour of malignant melanoma in an individual is unpredictable, although lesions arising before puberty or in the elderly tend to be less aggressive. Rarely, disseminated lesions undergo complete spontaneous regression, signifying immunological factors are probably involved. Melanomas with marked lymphocytic infiltration on histology have a better prognosis.

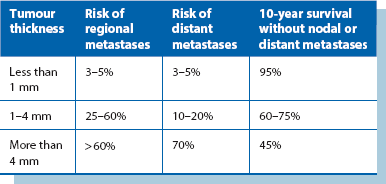

Prognostic factors: Measured tumour thickness on histological examination (Breslow) is the most useful guide to prognosis (Table 46.2) and has proved more accurate than the older ‘Clark’s level of invasion’. Tumour thickness correlates well with the likelihood of regional and distant metastases (Table 46.2). Other factors affecting prognosis include:

Table 46.2

Risk of regional and distant metastasis in malignant melanoma according to Breslow thickness

• The presence of ‘satellite lesions’ around the primary or ‘in transit’ lesions between primary and lymph node field—make the prognosis worse

• Ulceration of the primary lesion—increases likelihood of metastases and reduces survival

• Site of primary—head lesions carry a worse prognosis

• Gender—with thick lesions, females fare better than males

• Pathological stage—nodal or distant involvement. The number and size of lymph node metastases affects survival—a single positive node is associated with a 40% 10-year survival, falling to 13% with two or more positive. If distant metastases are present, 2-year survival is only 25%

• Certain histopathological characteristics (e.g. high mitotic rate) indicate poorer prognosis

Management of malignant melanoma: The first aim with a pigmented lesion is to establish whether it is malignant. Unless malignancy is clinically obvious, small lesions should be removed by excision biopsy and more extensive lesions sampled by incision biopsy. As a result of controlled trials, there have been two major changes in managing the local lesion. Firstly, it is no longer necessary to excise the lesion with a 5 cm margin all around and, secondly, split skin grafting is no longer regarded as essential to achieve skin cover and provide early warning of local recurrence. For melanomas less than 1 mm thick, a clear margin of 1 cm is sufficient. For thicker melanomas (1.1–4 mm), excision with 2 cm clearance achieves optimum survival. For lesions thicker than 4 mm, a 3 cm clearance is believed desirable. Primary closure or the use of local rotational flaps can usually achieve skin cover.

As regards lymph nodes, elective lymph node dissection of palpable or ultrasonographically detected regional lymph nodes improves survival. There has been interest in sentinel node biopsy for lesions thicker than 0.75 mm. Lymphatic dye is injected to travel to and locate ‘sentinel’ nodes for frozen section biopsy, proceeding to node dissection if positive. However, a large controlled trial comparing this with ‘watchful waiting’ plus excision of nodes that become palpable showed no survival advantage.

Adjuvant therapy has improved with B-RAF inhibitors, e.g. vemurafenib. C-KIT inhibitors, e.g. imatinib, plus modified radiotherapy is under trial and may reduce local recurrence rates and even improve survival. Melanoma cells are sensitive to higher radiotherapy dose fractions than are usual (600 rad as opposed to 180 rad). Systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy gives disappointing results, but for locally advanced limb melanoma with ‘in-transit’ lesions and regional spread not amenable to surgical excision, hyperthermic local or limb perfusion chemotherapy may provide effective control (but not cure).

Lesions originating in the dermis

In pathological terms, cysts are epithelium-lined cavities; most represent ducts dilated by retained secretion, usually due to obstruction. In contrast, breast cysts may show epithelial hyperplasia, excessive secretion and structural distortion. Some cysts arise from ectopic epithelial remnants (dermoids) or as a result of central necrosis in a malignant epithelial mass. Cysts commonly require surgical removal (or drainage) for aesthetic reasons or to exclude malignancy.

Cysts are common in skin. Most arise from elements of hair follicles in the dermis and consist of an epithelium-lined cavity filled with viscous or semi-solid epithelial degradation products. These are epidermal and pilar cysts. Occasionally, cysts arise from developmental epithelial remnants (dermoid cysts) or by traumatic implantation of epithelial fragments (implantation (epi) dermoids).

Epidermal cysts: These are by far the most common skin cysts, and are often incorrectly described as ‘sebaceous cysts’. Usually solitary, they may be found anywhere on the body (except the palms or soles), most commonly scalp, trunk, face and neck. They range up to several centimetres in diameter. Epidermal cysts are smooth and rounded, and covered by normal epidermis in which a blocked duct (punctum) may be visible. On palpation, they have a doughy, fluctuant consistency and are not usually tender. An important clinical diagnostic feature is that since they originate in skin, they are attached to it but are mobile over deeper tissues. Multiple small epidermal cysts sometimes develop on the scrotal skin or areola and cause embarrassment.

Histologically, an epidermal cyst has a stratified squamous lining epithelium and is filled with keratin, consistent with derivation from a hair follicle. The cyst contents are thick and waxy, and were originally thought to be sebaceous material. This gave rise to the erroneous name.

Surgical removal (see Ch. 10): Epidermal cysts are mainly removed because of recurrent inflammation. Others are removed for cosmetic reasons or sometimes because they interfere with clothing or hair combing. An incision is made over the cyst beside and around the punctum, taking care not to puncture the cavity. The cyst is enucleated by blunt dissection and delivered in its entirety. This ensures all lining epithelium is removed and prevents recurrence.

Inflamed epidermal cysts: Trauma to epidermal cysts (often unnoticed) may cause some contents to escape into surrounding tissues, eliciting an intense foreign-body inflammatory response. The patient may complain of pain, swelling, redness and even spontaneous discharge of liquefied cyst contents; this looks like pus but is sterile. These inflamed epidermal cysts are often described as ‘infected’ but this is rarely the case and antibiotic therapy is not indicated.

It is unwise to attempt removal of an acutely inflamed epidermal cyst because tissue planes cannot be recognised and some epithelial lining is likely to be left. If pain is severe, liquefied cyst contents should be drained by simple incision under local anaesthesia; this provides rapid symptom relief. Culture of this material rarely yields any growth. The residual smaller cyst should be excised later in the usual way as it is almost certain to flare up repeatedly if left.

Infective lesions

(Note: not infective in aetiology)

Pyogenic granuloma (Fig. 46.10) is a common inflammatory skin lesion that arises in response to minor penetrating foreign bodies such as splinters or thorns. It usually develops over about a week and rarely regresses spontaneously. Lesions are most common on the hands and feet but may occur on lips or gums. Pathologically, there is a mass of exuberant granulation tissue containing numerous polymorphs.

Clinically, these are solitary, reddish-blue fleshy nodules which may be polypoid. The surface may be ulcerated, making it clinically indistinguishable from amelanotic malignant melanoma. Pyogenic granulomas should be excised and the base curetted or cauterised to prevent recurrence.

Furuncle (boil) and carbuncle

A furuncle is a staphylococcal abscess that develops in a hair follicle in the dermis. Early lesions can be easily treated with topical fusidic acid. Diabetes mellitus can be a predisposing factor. The lesion rapidly enlarges and eventually ‘points’ at the surface, spontaneously discharging pus. The centre often contains a core of necrotic tissue. Once pus has discharged and the necrotic tissue shed, the lesion heals spontaneously; however, the necrotic core may need excising to speed healing. Drainage may be encouraged with poultices or dressings, such as magnesium sulphate paste, said to draw the pus to the surface by osmosis. Furuncles are most common in young men with acne, especially on the face, back of the trunk and lower limbs. Axillary furuncles are common in middle-aged females and tend to recur. Surgical drainage is necessary if a chronic abscess develops. A furuncle may be the source of systemic sepsis, especially in uncontrolled diabetes. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is a rare but very serious (and often fatal) complication of a furuncle on the lateral aspect of the nose or infra-orbital area. This area drains into the cavernous sinus via the facial vein and inferior ophthalmic veins (see Fig. 46.13).

A carbuncle, also staphylococcal, is larger than a furuncle and consists of a honeycomb of abscesses, often draining (inadequately) via multiple sinuses. The back (nape) of the neck is the usual site (Fig. 46.11); here the skin is tightly bound by interlacing bundles of fibrous tissue. Carbuncles are more likely to occur in diabetics, and may bring diabetes to light. Treatment is with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics such as flucloxacillin as early as possible. The aim is to minimise pus formation and necrosis that would lead to skin loss and delay healing. If pus has formed, thorough desloughing and drainage of the abscesses is required, usually leaving wounds open to heal by secondary intention.

Necrotising fasciitis

This serious and alarming condition is usually a complication of surgery or traumatic wounds and is covered in Chapter 3.

Miscellaneous lesions

Localised hyperplasia of sebaceous glands of the nose and in skin creases is common in men and women. Sebaceous glands are plentiful in this area. The condition probably reflects a mildly abnormal response to sex hormones. Apart from their unsightly appearance, these small nodular lesions may be clinically indistinguishable from basal cell carcinomas; diagnosis is made on histology after excision biopsy.

In rhinophyma, an extreme manifestation of sebaceous hyperplasia, the nose becomes enlarged and lumpy. It is mainly seen in older men, and is (unreliably) said to occur in heavy drinkers. Rhinophyma is treated by surgical correction, carbon dioxide laser or dermabrasion.

Keloid scars

Keloids are formed by excessive collagen deposition in the dermis during wound healing. The result is an elevated nodular lesion covered by normal epidermis. The chest and neck are particularly susceptible. The problem is much more common in black people.

Keloid formation may cause poor cosmetic results after injury, minor surgery, or even ear-piercing. Simply excising the lesion often makes scarring worse. Treatment is generally unsatisfactory; silicone gel under an occlusion dressing and/or intralesional steroids usually causes some regression. In extreme cases, excision of the scar followed by a low dose of local radiotherapy may suppress further keloid formation.

Histiocytoma

Histiocytomas (also known as dermatofibromas) are common painless skin lesions occurring mainly on the limbs. They are firm nodules, usually about 5 mm in diameter and deep reddish-brown in colour. They may be mistaken for malignant melanoma. Histologically, they contain numerous lipid-filled macrophages (histiocytes). One histological variant contains prominent vascular elements and has given rise to the confusing term sclerosing angioma.

Dermoid cysts

True dermoid cysts are pathologically similar to epidermal cysts, being lined by stratified squamous epithelium. As well as keratin, they can contain hair, sebaceous glands and other ectodermal structures. Dermoids are congenital lesions which arise from cystic change in epithelial remnants left at lines of embryological fusion. They are usually found in the midline of the scalp, neck and lower jaw and at the outer angle of the eyebrow (external angular dermoid). Treatment is by careful excision since some communicate with deeper structures and the tracts may need more extensive surgery.

Implantation (epi)dermoids

These small keratin-filled cysts arise from epidermal fragments implanted in the dermis by minor penetrating injuries. Though not derived from epidermal appendages, they are pathologically similar to epidermal cysts but may contain small foreign bodies. Implantation dermoids are most often seen on the fingers, often under the scar of a previous laceration.

Malignant lesions

Secondary (metastatic) carcinoma

Metastatic tumour deposits may present as small hard painless skin nodules. They are usually located in the dermis and covered by normal epidermis. Visceral malignancy, e.g. pancreatic or colon cancer, rarely presents with a metastasis at the umbilicus (Sister Joseph's nodule). With skin metastases, there is usually a history of treated malignancy elsewhere. Lobular breast carcinomas are the most common cause, but carcinomas of stomach, uterus, lungs, large bowel and kidneys can also metastasise to skin. Occasionally, biopsy of a mysterious skin lesion leads to a diagnosis of occult malignancy.

True skin metastases are different from local spread or local implantation of cells during surgery. Laparoscopic surgery for malignancy initially acquired a bad reputation because of port sites recurrences, but improved techniques have virtually eliminated this.

Management of skin secondaries depends on the primary diagnosis but the overall prognosis is usually poor. Treatment is palliative, by local excision, radiotherapy or chemotherapy, depending on the severity of symptoms and the size, number and location of secondaries.

Kaposi's sarcoma

This once rare condition has leapt to prominence as one of the most frequent presentations of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is associated with human herpes virus 8. The condition appears as multiple blueish-red to brown nodules or plaques, all of which are primary tumours (Fig. 46.12). They most commonly occur on the limbs. Excision biopsy confirms the diagnosis. KS tumours are characterised by proliferating dysplastic fibroblasts, accompanied by chronic inflammation, endothelial proliferation and haemorrhage. Treatment varies: classical type KS usually does not need treatment but larger lesions respond to radiotherapy. Endemic KS is treated by chemotherapy, and AIDS-related KS is controlled by highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Lesions of the hypodermis and deeper tissues

Cellulitis is a diffuse spreading infection of subcutaneous tissues and deeper layers of skin. It may be acute or chronic. Beta-haemolytic streptococci, usually Lancefield group A (Streptococcus pyogenes), are commonly responsible. These bacteria produce fibrinolysins and hyaluronidase which break down intercellular barriers and promote spread of infection through tissue planes. Although an intense neutrophil inflammatory response develops, pus rarely accumulates. Rather, the tissues become red and oedematous. If the skin surface is broken, a serous exudate is released.

Any area of skin may develop cellulitis (Fig. 46.13), the organisms usually gaining entry via a traumatic or surgical wound, although a wound is not always found. Clinically, the skin is greatly thickened, tense, hot, red and painful; margins are fairly clearly demarcated from adjacent normal skin. Lymphatics draining the affected area become inflamed and lymphangitis develops. Inflamed lymphatics are visible as red streaks passing towards the regional lymph nodes, which are also swollen and tender (lymphadenitis). Systemic features such as fever and tachycardia indicate bacteraemia or even septicaemia.

Acute cellulitis was a serious infection in earlier times, not least as a complication of surgery. It is now readily treated with antibiotics.

Cellulitis of the lower limb

Low-grade cellulitis can occur in the lower limb without evidence of any wound. This is usually in older women and presents as a localised, but not clearly demarcated, brawny inflammation of the leg, usually without regional lymph node involvement or systemic features of infection. Predisposing factors are lymphatic obstruction or oedema from any cause. These infections often recur and are difficult to document bacteriologically because there is no wound and no infected exudate. Nevertheless, they usually respond to antibiotics (such as tetracycline), rest, elevation of the limb, and compression stockings when the inflammation has settled. Recurrence is common at intervals of months or years.

A similar low-grade cellulitis may occur in the upper limb or chest wall as a result of lymphatic obstruction following lymph node excision or radiotherapy for breast cancer.

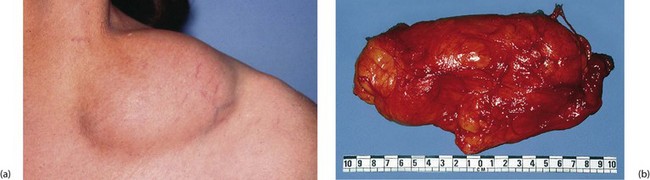

Lipoma and liposarcoma

Lipomas are benign tumours of fat. They occur anywhere fat is normally present, most often in the hypodermis of trunk and limbs. The aetiology is unknown, although mild trauma may be a factor. Typically, they present on the forearms (often multiple), in the supraclavicular fossa (Fig. 46.14), over the deltoid muscle or over the scapula. Lipomas can also be found within the peritoneal cavity, including the bowel submucosa, and within muscles or joints. They may also sometimes arise beneath periosteum.

Pathologically, lipomas consist of a multilobular mass of fatty tissue with thin fibrous septa. A tenuous fibrous capsule usually defines the lesion clearly from the surrounding tissue. Lipoma cells are histologically indistinguishable from normal adipocytes. Lipomas vary in size from about 2 to 20 cm and are shaped like a flattened dome. Overlying skin is normal. Their consistency is soft and almost fluctuant. Lipomas are removed if they are inconvenient or unsightly. If the margin is poorly defined at operation, recurrence is likely.

Liposarcoma is a rare malignant variant. It tends to occur in the retroperitoneal area and mediastinum rather than in the skin.

Neurofibroma, neurofibromatosis and schwannoma

Neurofibromas are benign tumours arising from the supporting fibroblasts of peripheral nerves. Tumour cells are loosely arranged in a gelatinous (myxomatous) intercellular material which often makes the lesion soft and pulpy to palpation. In the skin, neurofibromas may present as solitary sessile or pedunculated lesions near peripheral nerves. They are sometimes very tender.

The autosomal dominant inherited syndrome neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen's disease) is characterised by multiple neurofibromas and café-au-lait spots (coffee-coloured skin patches). Sometimes, neurofibromas are extremely numerous, and occasionally there is gross hypertrophy of subcutaneous tissues and skin folds. (This extreme variant was once thought to be the diagnosis of the famous ‘elephant man’ of Sir Frederick Treves; it is now believed, however, that he suffered from another inherited condition, Proteus syndrome.) A small proportion of neurofibromas undergo malignant change into sarcomas.

Schwannomas are benign tumours arising from the Schwann cells supporting peripheral nerves. They present as firm, nodular lesions tethered to a nerve, and pressure on the tumour may cause pain in the area of distribution of the nerve. Treatment is by careful excision, attempting to preserve the affected nerve. This requires an operating microscope and microsurgical manipulation.

Ganglion

This extremely common and inappropriately named condition is a cyst-like lesion derived from the lining of a synovial joint, tendon sheath or embryological remnants of synovial tissue. The ‘cystic’ space does not usually communicate with the associated joint or tendon sheath, and like synovial joint cavities, is not lined by epithelium. It contains a colourless, gelatinous fluid. Ganglia present as superficial lumps, usually about 1–2 cm in diameter, though sometimes larger. They are most common on the dorsum of the forearm and hand (Fig. 46.15) and around the ankle. They are rarely painful but sometimes cause mechanical problems or interference with footwear. Ganglia are easily recognised by their smooth, hemispherical surface, and firm but slightly fluctuant ‘cyst-like’ consistency. The overlying skin is normal and mobile and the ganglion weakly transilluminable.

The age-old treatment for a ganglion was a sharp blow with a family bible, which dissipated the cyst contents into the tissues. Recurrence almost inevitably followed. Needle aspiration or surgical excision are the accepted methods of treatment now, but recurrence is still common.

Lesions of vascular origin

Campbell de Morgan spots are small, bright-red spots which appear on the trunk, usually in older patients. They represent highly localised capillary proliferation and have no clinical significance except for titillation of bored examiners! Like other vascular lesions they blanch when compressed and then refill.

Spider naevi

Spider naevi or telangiectases are small red lesions consisting of a central arteriole from which radiate dilated capillaries. Isolated spider naevi may be found in normal individuals on trunk, neck and face. Their numbers markedly increase in chronic liver disease, especially cirrhosis, and occasionally in pregnancy. Treatment is rarely required but, when needed, laser therapy is probably the treatment of choice.

Angiomas

Despite their name, angiomas are not true neoplasms but rather congenital hamartomas. They arise from localised excessive development of thin-walled blood vessels which may be of small diameter (capillary haemangiomas) or hugely dilated (cavernous haemangiomas). The histological appearance is often ambiguous, with most angiomas containing both elements, as well as arteriovenous or even lymphatic components.

‘Port-wine stains’

The most common haemangiomas are port-wine stains. These occur anywhere, but especially on the face, neck and scalp, and cause cosmetic distress. They are present from birth and remain unchanged throughout life. Lesions are flat or slightly elevated and reddish-blue. They have an asymmetrical outline and range up to many centimetres in diameter. Trauma may cause bleeding or ulceration.

Surgical treatment, often urged by anguished patients, is rarely successful except for small lesions. Sclerosing agents can be injected to promote thrombosis, organisation and progressive devascularisation, but results are disappointing. Lasers such as the pulse dye laser, tuned to the colour frequency of haemoglobin, and other high-energy light sources are encouraging innovations and give promising results in some patients. Regrettably, the use of covering cosmetic preparations remains the best advice for most.

Strawberry naevi

The strawberry naevus is a distinct type of angioma. These occur in early childhood as bright-red fleshy lesions and grow for a few years before involuting spontaneously. Almost all resolve without scarring. Large strawberry naevi causing complications, e.g. ocular occlusion, are treated primarily with oral propranolol. Surgery is not indicated except to deal with redundant skin left after involution.

Cystic hygroma

Cystic hygroma is a lymphangioma presenting as a lump in the neck, usually during childhood; it is described in more detail in Ch 47, p. 589. Characteristically, the lesion is highly transilluminable.

Congenital syndromes

Gross vascular malformations form part of several rare congenital syndromes. These include Sturge–Weber syndrome (angiomas of the face and intracranial contents) and Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. The latter is characterised by the triad of port-wine stain, varicose veins and bone and soft tissue hypertrophy involving one lower limb; it may include the pelvis. Parks–Weber syndrome is probably another name for the same condition. The primary abnormality is probably multiple microscopic arteriovenous communications. These lead to hypertrophy of the limb (gigantism), which is warm to palpation. Venous abnormalities include gross varicose veins, deep venous abnormalities and persistent atypical veins often leading to venous ulceration.

Glomus tumour

This is a benign tumour derived from glomus bodies, small arteriovenous communications normally found in the peripheries. Glomus bodies are thought to play a part in controlling local blood flow. Glomus tumours occur singly, usually in fingers and often beneath the nail. They are tiny (1–3 mm) red flat lesions, exquisitely tender to the touch. Treatment is by surgical excision.

Lesions derived from skin appendages

Several benign tumours arise from skin appendages. The most common is the cylindroma, derived from sweat glands. Diagnosis is usually made only on histological examination of an excised nondescript skin lump.

Pilonidal sinus and abscess are described in Chapter 30.

Disorders of the nails

Ingrowing toenail

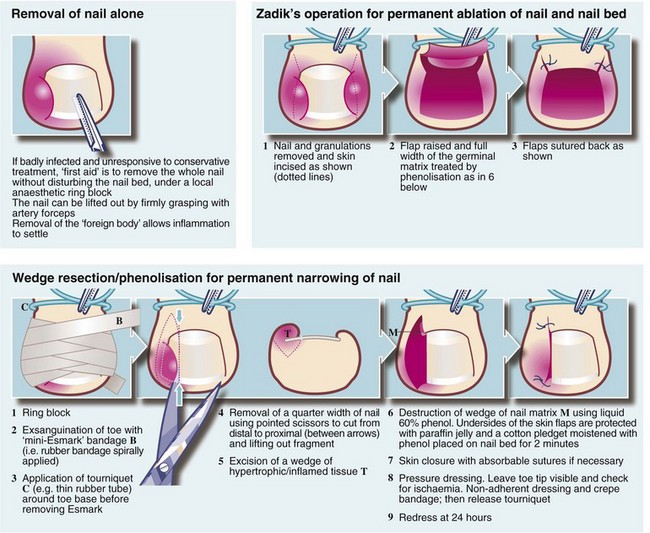

Pathophysiology: An ingrowing toenail (Fig. 46.16) occurs when the distal edge of the nail persistently cuts into the adjacent nail fold. The problem almost always affects the great toe. In effect there is a laceration which cannot heal because of the presence of a foreign body (the toenail). Superimposed infection by local bacterial and fungal flora complicates the picture. The combination of acute inflammation and attempts at repair produces exuberant granulation tissue around the laceration plus inflammatory swelling. Swelling aggravates trauma caused by the nail edge.

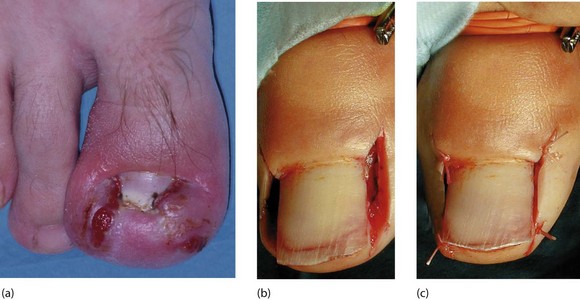

Fig. 46.16 Ingrowing toenail

(a) Inflamed ingrowing toenail affecting medial and lateral sides. There is a great amount of hypertrophy, making suitable footwear hard to find. (b) and (c) A different patient undergoing wedge resection and phenolisation of both sides of the nail. Note the use of a tourniquet

Ingrowing toenail is mainly confined to teenagers and young adults, particularly males. It probably results from a combination of inadequate hygiene, unsuitable footwear, cutting the nails too short at the corners and the macerating effect of sweat on the skin. High levels of circulating testosterone in adolescence may be an aetiological factor.

Management: The main objective of treatment is to prevent persistent trauma by the nail edge. Surgical operations result in a week or more of discomfort and immobility, so conservative treatment should be tried first.

Conservative treatment: In all cases, simple conservative measures include regular bathing, frequent changes of socks (which should be cotton), avoiding tight or narrow shoes and avoiding trauma to the toe when inflamed, for example from kicking a football.

For an inflamed ingrowing toenail, foot soaks in warm saline should be carried out twice daily for at least 10 minutes. Surgical spirit applied twice daily may also help. A useful further measure, once inflammation is settling, is to pack a small pledget of cotton wool beneath the nail corner to lift it out of the laceration. At the same time, the nail fold can be pushed away by packing an elongated pledget between nail fold and nail edge. These tiny packs can be left in place for days but need to be expanded as the nail corner rises away from its bed. Loose fittting footwear should be worn.

These conservative measures undertaken by the patient often succeed even in severe cases but require perseverance. Systemic antibiotics should be used only if infection is spreading; topical antibiotics are of little use.

Surgical treatment: Urgent surgical treatment involves avulsing the whole nail, or removing one side of it. This immediately removes the ‘foreign body’ and permits rapid resolution. For recurrent ingrowing toenails, particularly if abnormal nail morphology is contributory, part of the nail bed is best removed. Popular procedures are illustrated in Figure 46.17. Operations are usually performed under local anaesthesia using a ring block and tourniquet. Local anaesthetic incorporating a vasoconstrictor such as adrenaline (epinephrine) must never be used in digits because of the risk of ischaemic necrosis.

Onychogryphosis

Onychogryphosis (‘ram’s horn nail’) (Fig. 46.18) is a gross abnormality of nail growth. It affects the great toenail, which becomes thickened and distorted and nail cutting with ordinary nail scissors becomes impossible. Onychogryphosis is usually seen only in elderly patients and probably results from previous nail bed trauma. The condition usually presents when it interferes with wearing shoes. A chiropodist (podiatrist) can treat onychogryphosis with grinding instruments at regular intervals. Surgical removal of the nail and ablation of the bed is sometimes performed.

Subungual melanoma

Malignant melanomas sometimes develop beneath finger or toenails (Fig. 46.19). They are difficult to diagnose. Pigmented melanomas are easily mistaken for old subungual haematomas, and amelanotic melanomas appear even more innocuous, resembling pyogenic granulomas. Subungual melanomas often present early as a changing pigmented nail streak or longitudinal melanonychia. Advanced or clinically aggressive nail unit melanomas tend to present as a tumourous growth. Any suspicious lesion under the nail should be biopsied to avoid the disaster of missing a potentially curable malignant melanoma.