Developmental Disorders

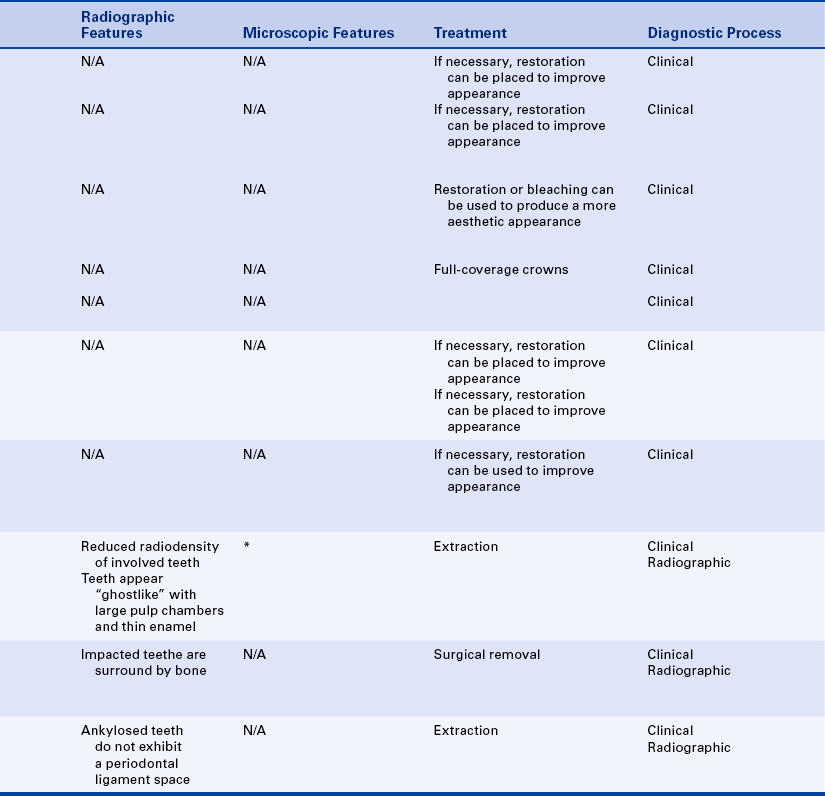

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1 Define each of the words in the vocabulary list for this chapter.

3 Recognize developmental disorders of the dentition.

4 Describe the embryonic development of the face, oral cavity, and teeth.

5 Define each of the developmental anomalies discussed in this chapter.

6 Identify (clinically, radiographically, or both) the developmental anomalies discussed in this chapter.

7 Distinguish between intraosseous cysts and extraosseous cysts.

8 Describe the differences between odontogenic and nonodontogenic cysts.

9 Name four odontogenic cysts that are intraosseous.

10 Name two odontogenic cysts that are extraosseous.

11 Name four nonodontogenic cysts that are intraosseous.

12 Name four nonodontogenic cysts that are found in the soft tissues of the head, neck, and oral region.

13 List and define three anomalies that affect the number of teeth.

14 List and define two anomalies that affect the size of teeth.

15 List and define five anomalies that affect the shape of teeth.

16 Define and identify each of the following anomalies affecting tooth eruption: impacted teeth, embedded teeth, and ankylosed teeth.

17 Identify the diagnostic process that contributes most significantly to the final diagnosis of each developmental anomaly discussed in this chapter.

(ang′′kĭ-lo-glos′e-ah) Extensive adhesion of the tongue to the floor of the mouth or the lingual aspect of the anterior portion of the mandible.

(ang′kĭ-lōsd tēth) Teeth that are fused to the alveolar bone; a condition especially common with retained deciduous teeth.

(an′′o-don′she-ah) Congenital lack of teeth.

(ah-nom′ah-le) Marked deviation from normal, especially as a result of congenital or hereditary defects.

(kom′ĭ-shūr) The site of union of corresponding parts (e.g., the corners of the lips) (labial commissure, commissural lip pits)

(kon-kres′ens)In dentistry a condition in which two adjacent teeth become united by cementum.

(kon-jen′ĭ-tal) Present at and existing from the time of birth.

(sist)An abnormal sac or cavity lined by epithelium and enclosed in a connective tissue capsule.

(dens in den′te) “A tooth within a tooth”; a developmental anomaly that results when the enamel organ invaginates into the crown of a tooth before mineralization.

(den′′tĭ-no-jen′ĕ-sis) The formation of dentin.

(dif′er-en′′she-a′shun) The distinguishing of one thing from another.

(di-las′′er-a′shun) An abnormal bend or curve, as in the root of a tooth.

(fu′zhun) The union of two adjacent tooth germs.

(jem-ĭ-na′shun) “Twinning′; a single tooth germ attempts to divide, resulting in the incomplete formation of two teeth; the tooth usually has a single root and root canal.

(hi′′po-don′she-ah) Partial anodontia; the lack of one or more teeth.

(im-pakt′ed tĕth) Teeth that cannot erupt into the oral cavity because of a physical obstruction.

(mak′′ro-don′she-ah) Abnormally large teeth.

(mi′′kro-don′she-ah) Abnormally small teeth.

(mul-tĭ-lok′ū-ler) A radiographic appearance in which many circular radiolucencies exist; these can appear “soap bubble–like” or “honeycomb-like.”

(nod′ūl) A small solid mass that can be detected through touch.

(prĕd-ĭ-lĕk′shun) A disposition in favor of something; preference.

(pro-lif′′ĕ-ra'shun) The multiplication of cells.

(sto′′mo-de′um) The embryonic invagination that becomes the oral cavity.

(soo′′per-nu′mer-ar′′e) In excess of the normal or regular number, as in teeth.

The development of the human body is an extremely complex process that begins when an egg is fertilized by a sperm. It continues with a series of cell divisions, multiplications, and differentiation into various tissues and structures. A failure or disturbance that occurs during these processes may result in a lack, excess, or deformity of a body part. These disorders are called developmental disorders, or developmental anomalies.

Inherited disorders are different from developmental disorders in that they are caused by an abnormality in the genetic makeup (genes and chromosomes) of an individual and transmitted from parent to offspring through the egg or sperm (see Chapter 6).

A congenital disorder is one that is present at birth. It can be either inherited or developmental; however, the cause of most congenital abnormalities is unknown.

The complex process of proliferation and differentiation that takes place in the human body provides numerous possibilities for errors or defects in development. The head and neck region is a common location for such errors because of its intricate sequence and pattern of development. This chapter includes descriptions of developmental disorders of the face, oral cavity, and teeth with which the dental hygienist should be familiar.

Some of the developmental disturbances discussed in this chapter can be identified clinically, whereas others are identified by radiographic examination; still others require biopsy and histologic examinations. A thorough clinical examination, including examination of extraoral and intraoral structures, is an essential component. Dental radiographs are an important part of the examination. Any developmental anomalies observed either clinically or radiographically are documented in the patient's record even if no treatment is indicated. The patient is informed of all dental anomalies, their possible implications, and the treatment necessary, if any. In some instances referral to a specialist is indicated. To better understand these developmental disorders, a brief review of the embryonic development of the face, oral cavity, and teeth is included in this chapter.

FACE

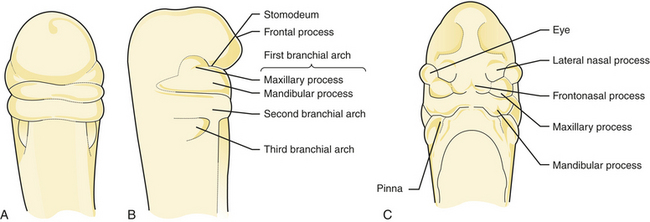

Development of the face is a process of selective growth or proliferation and differentiation (Figures 5-1 and 5-2). During the third week of embryonic life, an invagination or infolding of the ectoderm forms the primitive oral cavity, which is called the stomodeum. Just above the stomodeum is a process called the frontal process, and just below it is a structure called the first branchial arch. Additional branchial arches form below the first branchial arch. All of the face and most of the structures of the oral cavity develop from either the frontal process or the first branchial arch. The first branchial arch divides into two maxillary processes and the mandibular process. The maxillary processes give rise to the upper part of the cheeks, the lateral portions of the upper lip, and part of the palate. The mandibular arch forms the lower part of the cheeks, the mandible, and part of the tongue.

FIGURE 5-1 In the third week of embryonic life an invagination or infolding of the ectoderm forms the primitive oral cavity called the stomodeum. A and B, As facial development continues, the first branchial arch divides into two maxillary processes. C, The fourth week of development.

FIGURE 5-2 The right and left palatine processes fuse to form the maxilla and premaxilla. A Y-shaped pattern results.

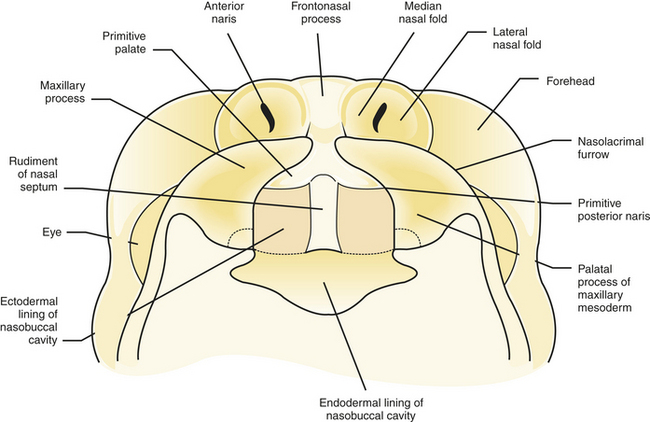

As development continues, two pits (called olfactory pits) mark the future openings of the nose that develop on the surface of the frontal process. They divide the frontal process into three parts: (1) the median nasal process, (2) the right lateral nasal process, and (3) the left lateral nasal process. The lateral nasal processes form the sides of the nose, whereas the median nasal process forms the center and tip of the nose. Later the median nasal process grows downward between the maxillary processes to form a pair of bulges called the globular process. This continues to grow downward, forming the portion of the upper lip called the philtrum. Most of these developments are completed by the end of the eighth week of embryonic life.

ORAL AND NASAL CAVITIES

The area of the palate called the premaxilla develops from the globular process. The lateral palatine processes (left and right) are formed from the maxillary processes. These lateral palatine processes then fuse with the premaxilla. The fusion creates a Y-shaped pattern (see Figure 5-2). The nasal septum arises from the median nasal process. The right and left maxillary processes fuse together with the nasal septum at the center of the palate.

The tongue develops from the first three branchial arches. The second and third branchial arches are located just below the first branchial arch (see Figure 5-1, B). The body of the tongue forms from the first branchial arch, and the base of the tongue forms from the second and third branchial arches.

TEETH

Tooth development, or odontogenesis, in the human embryo takes place at about the fifth week of embryonic life and involves both ectoderm and ectomesenchyme. The ectomesenchyme is derived from neural crest cells.

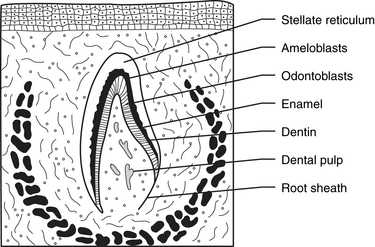

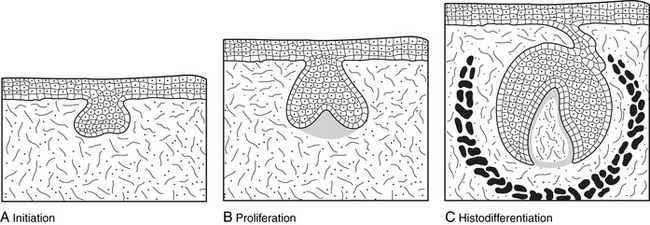

Odontogenesis begins with the formation of a band of ectoderm in each jaw called the primary dental lamina. Ten small knoblike proliferations of epithelial cells develop on the primary dental lamina in each jaw (Figure 5-3, A). Each of these proliferations extends into the underlying mesenchyme, becoming the early enamel organ for each of the primary teeth (Figure 5-3, B).

FIGURE 5-3 Development of a tooth germ showing initiation of dental lamina (A), proliferation of dental lamina (B), and differentiation of the components of the tooth germ (C).

The tooth germ is composed of three parts: (1) the enamel organ, (2) the dental papilla, and (3) the dental sac or follicle (Figure 5-3, C). The enamel organ develops from ectoderm, and the dental papilla and dental sac or follicle develop from mesenchyme. Cell differentiation in the enamel organ progresses to produce ameloblasts, which form enamel. In the dental papilla odontoblasts are produced to form dentin. The permanent or succedaneous enamel organs form at the same time.

Formation of dental hard tissues occurs during the fifth month of gestation (Figure 5-4). Dentinogenesis is the formation of dentin. Dentin is the first mineralized tooth tissue to appear. When it begins to form, the mesenchymal tissue within the tooth germ is called the dental papilla. After dentin is produced, the dental papilla is called the dental pulp. Enamel is the product of the enamel organ. Enamel matrix begins to form shortly after dentin, and mineralization and maturation of enamel follow the formation of the matrix. Amelogenesis refers to the formation of enamel.

The dental sac or follicle that surrounds the developing tooth germ provides cells that form cementum, the periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Cementogenesis (the formation of cementum) occurs after crown formation is complete. An epithelial structure called the Hertwig's epithelial root sheath proliferates to shape the root of the tooth and induces the formation of the root dentin. The cells of the Hertwig's epithelial root sheath must break up and pull away from the root surface before cementum can be produced. Very little cementum is produced until the tooth has erupted and is in occlusion and functioning. Root length is not completed until 1 to 4 years after the tooth erupts into the oral cavity.

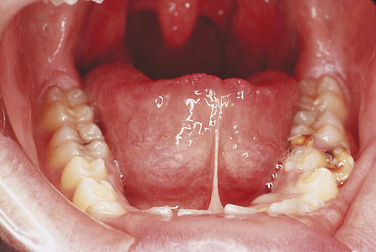

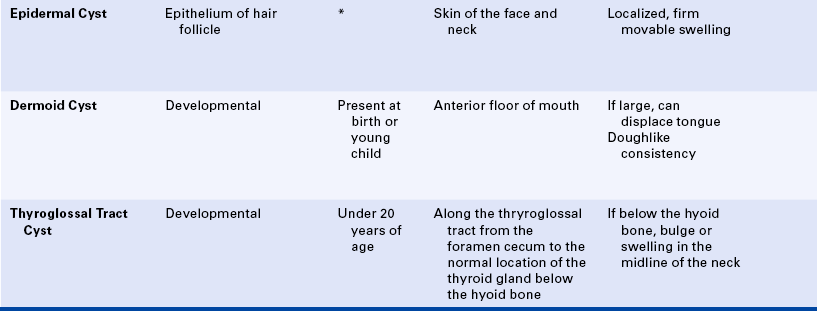

ANKYLOGLOSSIA

Ankyloglossia is an extensive adhesion of the tongue to the floor of the mouth, which is often referred to as “tongue-tied.” Ankyloglossia is derived from the Greek words “ankylos,” meaning adhesion, and “glossa,” meaning tongue. This adhesion results from the complete or partial fusion of the lingual frenum to the floor of the mouth. Total ankyloglossia is rare. Partial ankyloglossia appears clinically as a very short lingual frenum connecting the anteroventral portion of the tongue to the floor of the mouth (Figure 5-5). Patients with a short lingual frenum may exhibit no adverse effects, but some may have problems with speech. Gingival recession and bone loss can occur if the frenum is attached high on the lingual alveolar ridge. Surgical removal of a portion of the lingual frenum, known as frenectomy, is the usual treatment for ankyloglossia.

COMMISSURAL LIP PITS

Commissural lip pits are epithelium-lined blind tracts located at the corners of the mouth (commissures) (Figure 5-6). These tracts may be shallow, or they may be several millimeters deep. They are a relatively common developmental anomaly. The cause of commissural lip pits is not clear; both the incomplete fusion of the maxillary and mandibular processes and the defective development of the horizontal facial cleft have been suggested. The commissural lip pit may be observed during examination.

Another lip pit that occasionally may be seen is the congenital lip pit. It occurs near the midline of the vermilion border of the lip and may appear as either a unilateral or a bilateral depression. No treatment is indicated for lip pits.

LINGUAL THYROID

Lingual thyroid, or ectopic lingual thyroid nodule, is a small mass of thyroid tissue located on the tongue away from the normal anatomic location of the thyroid gland. It is an uncommon developmental anomaly that results from the failure of the primitive thyroid tissue to migrate from its developmental location in the area of the foramen cecum on the posterior portion of the tongue to its normal position in the neck.

Clinically the lingual thyroid nodule appears as a smooth nodular mass at the base of the tongue posterior to the circumvallate papillae on or near the midline. It can be asymptomatic or can cause a feeling of fullness in the throat or difficulty in swallowing. Histologically the lingual thyroid is composed of immature or mature thyroid tissue.

On occasion the size of the lingual thyroid necessitates its removal. However, this nodule may be the patient's only functioning thyroid tissue. Therefore it is necessary to establish the presence of functioning thyroid tissue elsewhere before any nodular lesion located in the posterior aspect of the tongue is removed. If a normally located thyroid gland is lacking or nonfunctional, the lingual thyroid is not removed.

DEVELOPMENTAL CYSTS

A cyst is an abnormal, pathologic sac or cavity lined by epithelium and enclosed in a connective tissue capsule. Cysts occur throughout the body, including the oral region.

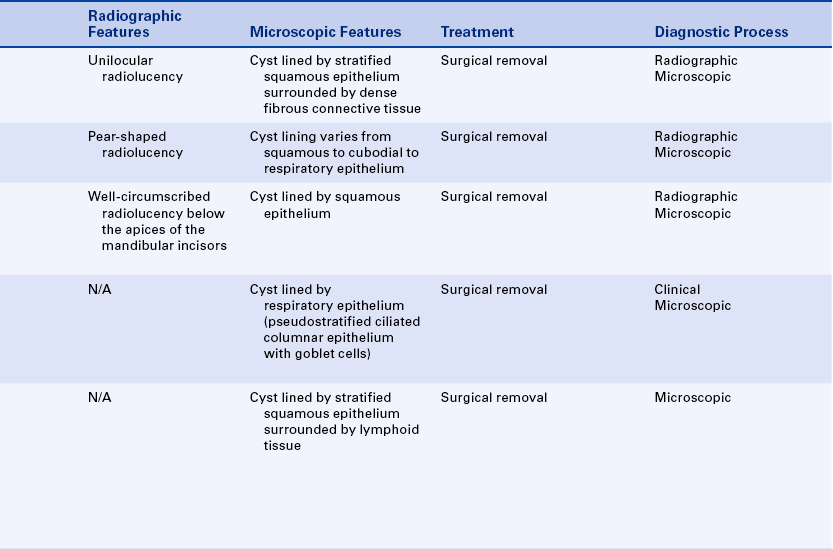

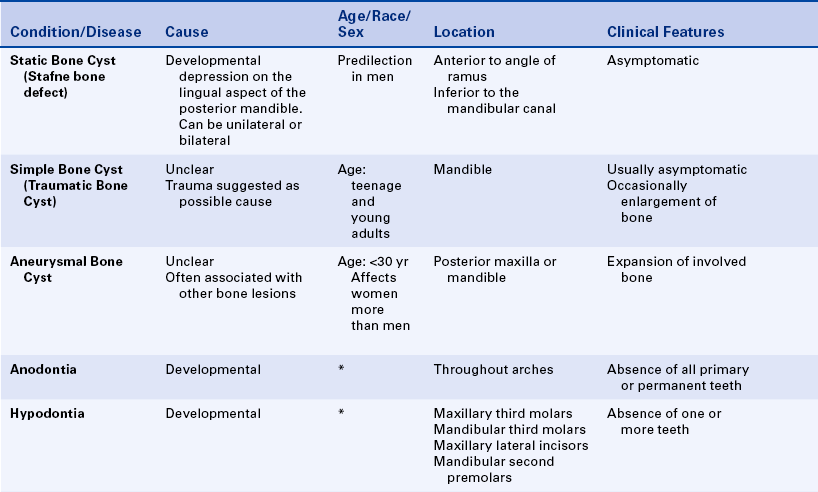

The cysts discussed in this chapter are all related to the development of the face, jaws, and teeth. Some have a distinctive histologic appearance, and a definitive diagnosis is based on microscopic examination of the tissue. Other cysts are lined by less distinctive epithelium. The diagnosis of these cysts is based on both the histologic appearance of the tissue and the location of the cyst.

The most common cyst observed in the oral cavity is caused by pulpal inflammation and is called the periapical cyst, (radicular cyst) (see Chapter 2). It develops from a preexisting periapical granuloma found at the apex of a non-vital tooth. The residual cyst is a periapical cyst that remains after extraction of the offending tooth. Because cysts are commonly observed in the jaws and surrounding soft tissues, the dental hygienist should understand their diagnostic criteria, pathogenesis, and prognosis. The preliminary identification of a cystic lesion is within the scope of dental hygiene practice.

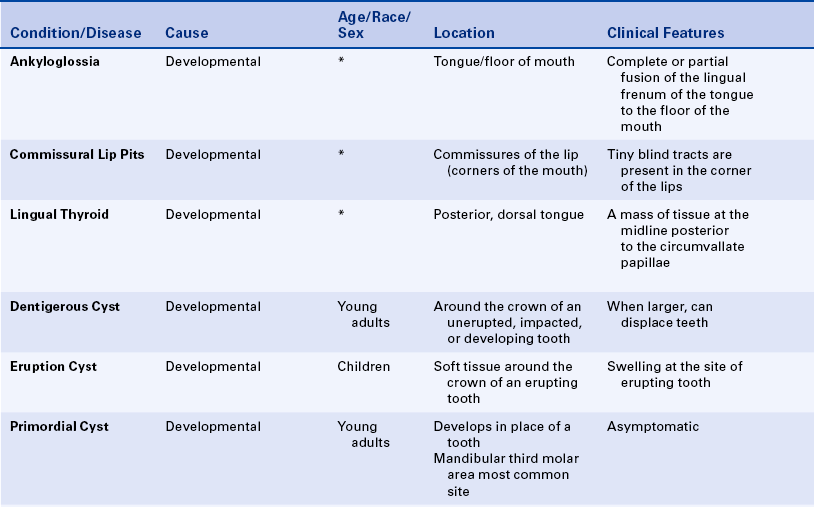

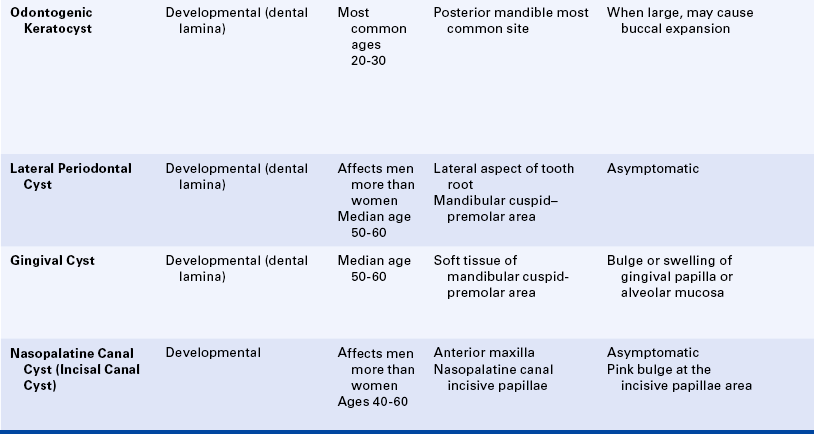

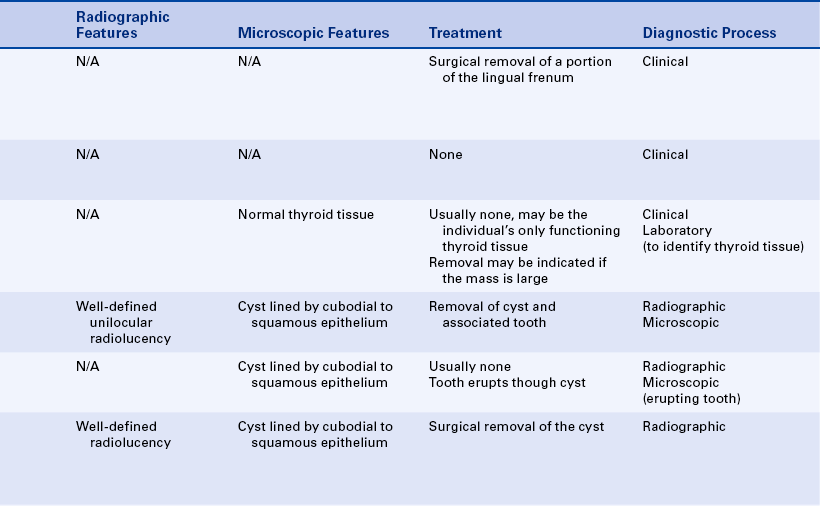

Developmental cysts are classified as odontogenic (related to tooth development) and nonodontogenic (not related to tooth development). Cysts are also classified according to location, cause, origin of the epithelial cells, and histologic appearance (Box 5-1). Developmental cysts can vary in size from small, asymptomatic lesions to large lesions that can cause expansion of bone. Very large and long-standing lesions can resorb tooth structure or move teeth. Oral cysts that occur within bone are called intraosseous cysts, and cysts that occur in soft tissue are called extraosseous cysts.

Radiographically cysts within bone generally appear as well-circumscribed radiolucencies. All cysts may appear unilocular, but some are more likely to appear as multilocular radiolucencies. When cysts are found within soft tissue, usually no radiographic change occurs.

ODONTOGENIC CYSTS

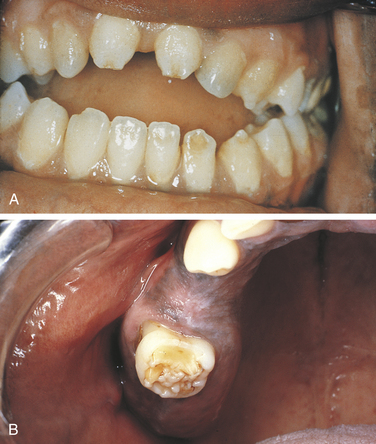

A dentigerous cyst, also called a follicular cyst, forms around the crown of an unerupted or developing tooth (Figure 5-7). It is the second most common odontogenic cyst after the periapical cyst. The epithelial lining originates from the reduced enamel epithelium after the crown has completely formed and calcified. Fluid accumulates between the crown and the reduced enamel epithelium. The reduced enamel epithelium results from remnants of the enamel organ. The most common location for the dentigerous cyst is around the crown of an unerupted or impacted mandibular third molar. However, a dentigerous cyst may form around the crowns of other unerupted or impacted teeth such as the maxillary cuspid or a supernumerary tooth. There is a higher incidence in males and this cyst is most often seen in young adults in their twenties and thirties. The size of these cysts can range from small and asymptomatic to very large. When large, it is capable of displacing teeth or causing a fracture of the mandible.

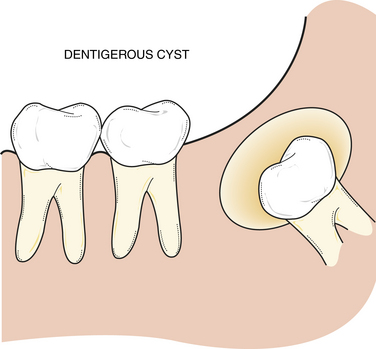

FIGURE 5-7 Schematic of a dentigerous cyst located around the crown of an unerupted or impacted tooth.

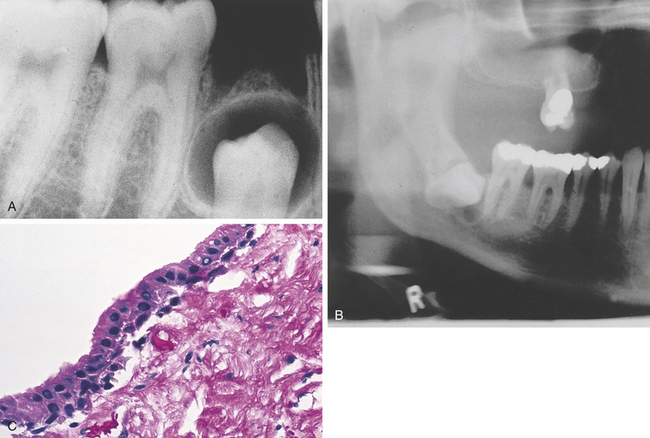

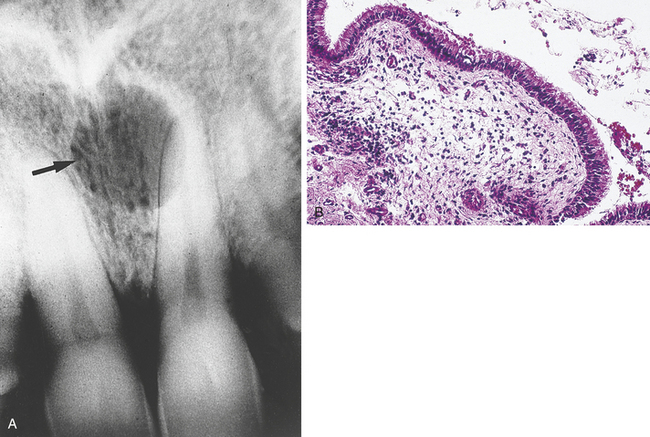

Radiographically the dentigerous cyst appears as a well-defined, unilocular radiolucency around the crown of an unerupted or impacted tooth (Figure 5-8, A and B). Histologically the lumen is most characteristically lined with cuboidal epithelium surrounded by a wall of connective tissue Figure 5-8, C). It may also be lined with stratified squamous epithelium. The lumen may be filled with a watery or serous fluid.

FIGURE 5-8 Radiographs of dentigerous cysts around the crown of an unerupted bicuspid (A) and an impacted third molar (B). C Microscopic appearance of a dentigerous cyst.

Treatment of a dentigerous cyst involves the complete removal of the cystic lesion and usually the tooth involved. If it is not removed, the cyst wall continues to enlarge. In addition, a risk exists that a neoplasm (i.e., ameloblastoma) may develop (see Chapter 7).

Eruption Cyst

An eruption cyst is similar to a dentigerous cyst. It is found in the soft tissue around the crown of an erupting tooth.

The eruption cyst can be seen in deciduous and permanent teeth, but it is most commonly associated with the first permanent molars and incisors.

Because the tooth erupts through the cyst, this condition usually does not require treatment. Occasionally the dome of the eruption cyst is removed to expose the crown. The tooth is allowed to erupt naturally.

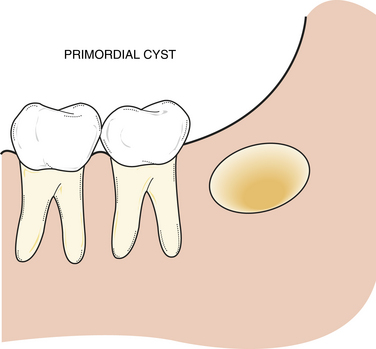

Primordial Cyst

A primordial cyst develops in place of a tooth and is most commonly found in place of the third molar or posterior to an erupted third molar (Figure 5-9). It originates from remnants and degeneration of the enamel organ. A history that the tooth was never present is an essential component of the diagnostic process.

Primordial cysts are most often seen in the young adult; no sex predilection has been reported. Clinically the cyst usually is asymptomatic and is discovered on radiographic examination. Radiographically it is a well-defined, radiolucent lesion that can be either unilocular or multilocular. The histologic appearance and diagnosis of the primordial cyst may vary. Histologically the lumen is lined by stratified squamous epithelium surrounded by parallel bundles of collagen fibers. A layer of orthokeratin or parakeratin can cover the epithelium. The term primordial cyst simply refers to its development in place of a tooth. For this reason, biopsy and histologic examination of primordial cysts are essential. Histologically a primordial cyst can be an odontogenic keratocyst or a lateral periodontal cyst.

Treatment of a primordial cyst involves surgical removal of the entire lesion. The prognosis depends on the histology; the risk of recurrence depends on the histologic diagnosis. For example, if the cyst is histologically an odontogenic keratocyst, the risk of recurrence is greater than if the cyst is lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

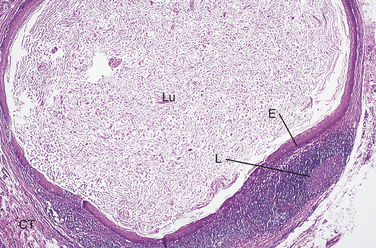

Odontogenic Keratocyst

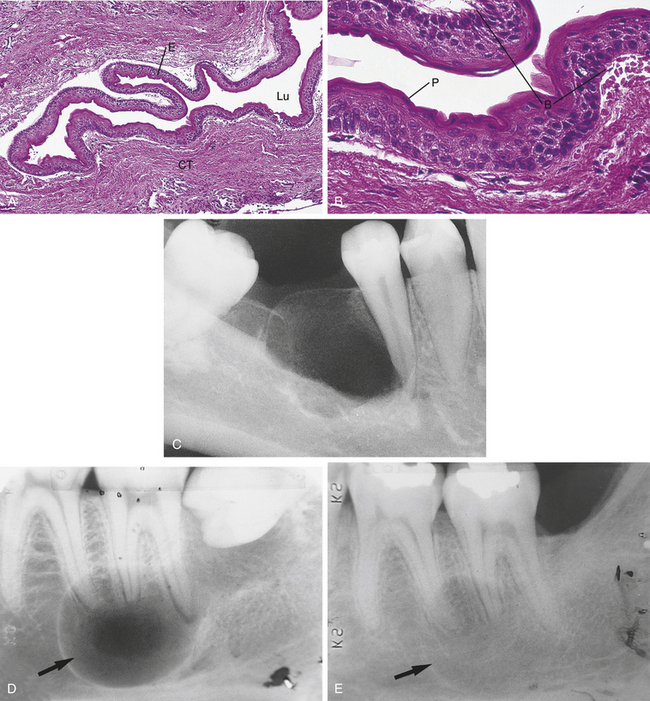

An odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) is an odontogenic developmental cyst that is characterized by its unique histologic appearance and frequent recurrence. The lumen is lined by epithelium that is 8 to 10 cell layers thick and surfaced by parakeratin. The basal cell layer is palisaded and prominent; the interface between the epithelium and the connective tissue is flat (Figure 5-10, A and B).

FIGURE 5-10 A, Microscopic appearance of an odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) showing a thin uniform epithelial lining (low power). Lu, Lumen; E, epithelium; CT, connective tissue. B, Microscopic appearance of an OKC showing a corrugated parakeratotic surface (P) and a prominent basal cell layer (B) (high power). C, Radiograph of an OKC showing a multilocular radiolucency. D, Radiograph of an OKC extending to the third molar. E, Same patient in D 2 years later, showing recurrence of OKC. The reader should note that the third molar has been removed.

These cysts are most often seen in the mandibular third molar region, and there is a slight predilection in males. Radiographically the odontogenic keratocyst frequently appears as a well-defined, multilocular, radiolucent lesion (Figure 5-10, C). Unilocular lesions may also occur. The radiographic appearance of an odontogenic keratocyst can be identical to that of an odontogenic tumor. The odontogenic keratocyst can move teeth and resorb tooth structure but does not usually cause expansion of bone. The OKC is also associated with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome) (see Chapter 6).

Treatment of an odontogenic keratocyst is rather aggressive because of the high recurrence rate (Figure 5-10, D and E). The cyst generally extends beyond the borders that are seen on the radiograph because it extends between the trabeculae of bone. Therefore thorough surgical excision and osseous curettage are recommended. Careful follow-up and evaluation are essential.

Calcifying Odontogenic Cyst

The calcifying odontogenic cyst (COC) is a developmental nonaggressive cystic lesion lined by odontogenic epithelium that closely resembles the epithelium of the odontogenic tumor called an ameloblastoma; in addition, it has a characteristic feature called ghost cells. Generally the cyst is treated conservatively and does not recur. A solid variant of the calcifying odontogenic cyst is called the odontogenic ghost cell tumor; it has been suggested that this solid variant represents a neoplasm rather than a cyst. Because of its histologic resemblance to the ameloblastoma, the calcifying odontogenic cyst is described in detail in Chapter 7.

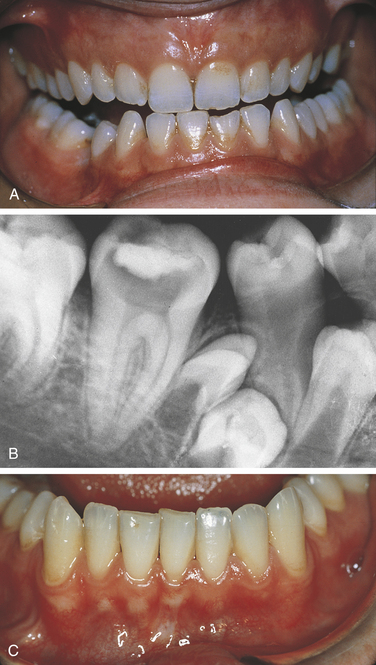

Lateral Periodontal Cyst and Gingival Cyst

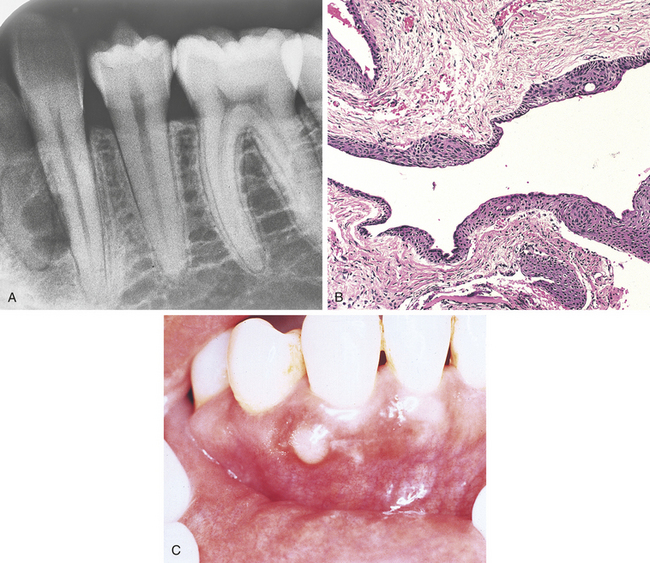

The lateral periodontal cyst is named for its location. It is seen most often in the mandibular cuspid and premolar area. It presents as an asymptomatic, unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion located on the lateral aspect of a tooth root (Figure 5-11, A). Histologically a thin band of stratified squamous epithelium that exhibits focal epithelial thickenings lines the cyst (Figure 5-11, B). The gingival cyst exhibits the same type of epithelial lining as the lateral periodontal cyst and is located in the soft tissue of the same area. The gingival cyst appears as a small bulge or swelling of the attached gingiva or interdental papillae (Figure 5-11, C).

FIGURE 5-11 A, Radiograph of a lateral periodontal cyst. This biloculated, well-defined radiolucency is located lateral to the tooth root. B, Microscopic appearance of a lateral periodontal cyst showing a thin epithelial lining with focal epithelial thickenings. C, Gingival cyst. (C courtesy Drs. Paul Freedman and Stanley Kerpel.)

The lateral periodontal cyst is found most often in males. No sex predilection has been reported for gingival cysts. Both the lateral periodontal cyst and the gingival cyst are treated by surgical excision. A few cases of recurrence of lateral periodontal cysts have been reported.

NONODONTOGENIC CYSTS

A nasopalatine canal cyst (incisive canal cyst) is located within the nasopalatine canal or the incisive papilla. When found in the papilla, it is referred to as a cyst of the palatine papilla. This cyst arises from epithelial remnants of the embryonal nasopalatine ducts. The lesion is most commonly seen in adults between 40 and 60 years of age, and a strong predilection exists for males. The cyst is usually asymptomatic. There may be a small pink bulge near the apices and between the roots of the maxillary central incisors on the lingual surface. The adjacent teeth are usually vital.

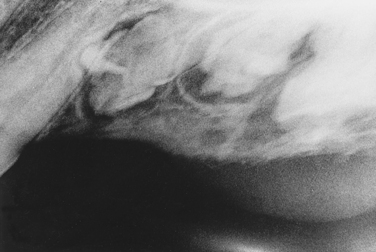

Radiographically the nasopalatine canal cyst is a well-defined, radiolucent lesion that is often heart shaped Figure 5-12, A), resulting from the anatomic Y shape of the canal. When it is heart shaped, it is evenly distributed to the right and left of the midline.

FIGURE 5-12 A, An incisive canal cyst may be located in the anterior maxilla in either bone or soft tissue or both. This radiograph of an incisive canal cyst shows a well-circumscribed radiolucency between the maxillary central incisors. B, Microscopic appearance of an incisive canal cyst showing a pseudostratified, ciliated, columnar epithelial lining.

Histologically the cyst is lined by epithelium that varies from stratified squamous to pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (Figure 5-12, B). The connective tissue wall contains nerves and blood vessels that are normally found in the area and may also contain inflammatory cells.

Treatment of a nasopalatine canal cyst is surgical enucleation. It is especially important that surgery take place in the edentulous patient before the fabrication of a prosthesis. Recurrence is rare.

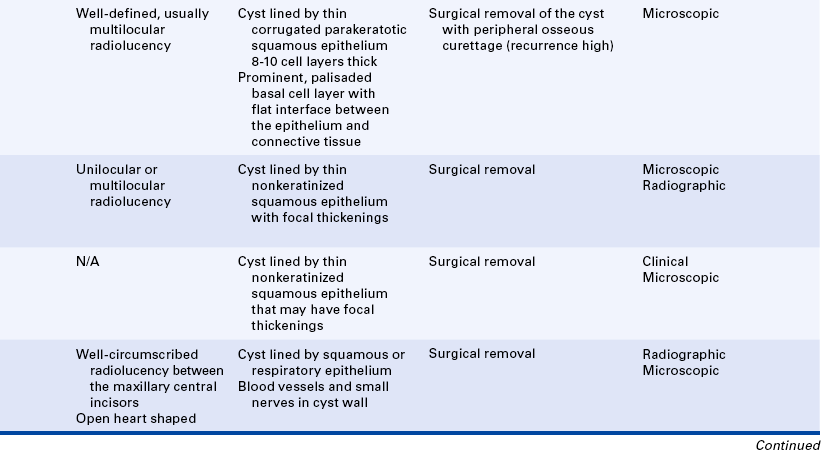

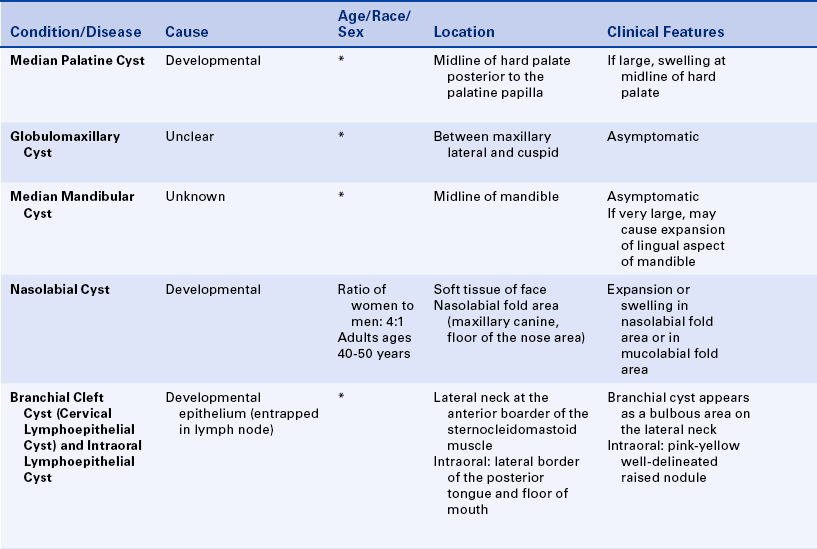

Median Palatine Cyst

A median palatine cyst appears as a well-defined unilocular radiolucency and is located in the midline of the hard palate (Figure 5-13). The cyst is thought to be a more posterior form of a nasopalatine canal cyst. Histologically the median palatine cyst is lined with stratified squamous epithelium that is surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissue. The median palatine cyst is treated by surgical enucleation. The prognosis is good, and recurrence is rare.

Globulomaxillary Cyst

Radiographically a globulomaxillary cyst is a well-defined, pear-shaped radiolucency found between the roots of the maxillary lateral incisor and cuspid (Figure 5-14). Although it was once thought to be a fissural cyst, it is now believed to be of odontogenic epithelial origin. Microscopic evaluation includes the central giant cell granuloma, OKC, and lateral periodontal cyst. The size of the lesion can vary; however, when it is large enough, a divergence of the roots can result. The adjacent teeth are usually vital. Pulp testing can rule out a periapical cyst or periapical granuloma. Surgical enucleation of the globulomaxillary cyst is recommended but determined by the microscopic diagnosis. The prognosis and recurrence also depend upon the final diagnosis.

Median Mandibular Cyst

A median mandibular cyst is a rare lesion. As its name indicates, it is located in the midline of the mandible. The origin of the median mandibular cyst is also unclear. Some believe it to be of odontogenic origin ranging from odontogenic cysts to tumors. Because no midline fusion occurs between the bony processes, there is no evidence of epithelial entrapment. The surrounding teeth are vital. Radiographically a well-defined radiolucency is seen below the apices of the mandibular incisors. A median mandibular cyst is treated by surgical removal, and prognosis is good.

Nasolabial Cyst

A nasolabial cyst is a soft tissue cyst with no alveolar bone involvement. The origin of this cyst is uncertain. At present it is thought to originate from the lower anterior portion of the nasolacrimal duct. The cyst is observed in adults 40 to 50 years of age; a strong predilection (4:1) exists for females.

Clinically there may be an expansion or swelling in the mucolabial fold in the area of the maxillary canine and the floor of the nose. Usually no radiographic change is associated with this cyst. However, when the lesion is large enough, expansive pressure can cause the resorption of bone (Figure 5-15). Histologically the cyst is lined with pseudostratified, ciliated columnar epithelium and multiple goblet cells. Treatment of a nasolabial cyst is surgical excision; prognosis is good, and recurrence is rare.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

A branchial cleft cyst (cervical lymphoepithelial cyst) is located on the lateral neck at the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It is composed of a stratified squamous epithelial lining surrounded by a well-circumscribed component of lymphoid tissue and connective tissue (Figure 5-16). It appears to arise from epithelium entrapped in a lymph node during development. When found intraorally, the lymphoepithelial cyst is most commonly seen on the floor of the mouth and the lateral borders of the posterior tongue. The lymphoepithelial cyst appears as a pinkish-yellow, raised nodule when seen intraorally. Treatment of a branchial cleft cyst (cervical lymphoid cyst) and intraoral lymphoepithelial cyst consists of surgical excision, and prognosis is good.

Epidermal Cyst

An epidermal cyst presents as a raised nodule in the skin of the face or neck. Histologically the cyst is lined by keratinizing epithelium that resembles the epithelium of skin (epidermis). The cyst lumen is usually filled with keratin scales. Most epidermal cysts are thought to originate from the epithelium of the hair follicle. Occasionally when located in the skin of the cheek, the nodule may be noted intraorally from the buccal mucosal aspect and the skin. An epidermoid cyst is treated by surgical excision, and prognosis is good.

Dermoid Cyst and Benign Cystic Teratoma

A dermoid cyst is a developmental cyst that is often present at birth or noted in young children. It is more common in other parts of the body than in the head and neck. When the dermoid cyst occurs in the oral cavity, it is usually found in the anterior floor of the mouth. The cyst may cause displacement of the tongue and may have a doughlike consistency when palpated.

Histologically the dermoid cyst is lined by orthokeratinized, stratified squamous epithelium surrounded by a connective tissue wall. The lumen is usually filled with keratin. Hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands may be seen in the cyst wall. A benign cystic teratoma has a cystic component that resembles the dermoid cyst. In addition, teeth, bone, muscles, and nerve tissue may be found in the wall of this lesion. Teeth are usually not found in the malignant form of the teratoma. Treatment of the dermoid cyst is surgical excision; prognosis is good, and malignant transformation is rare.

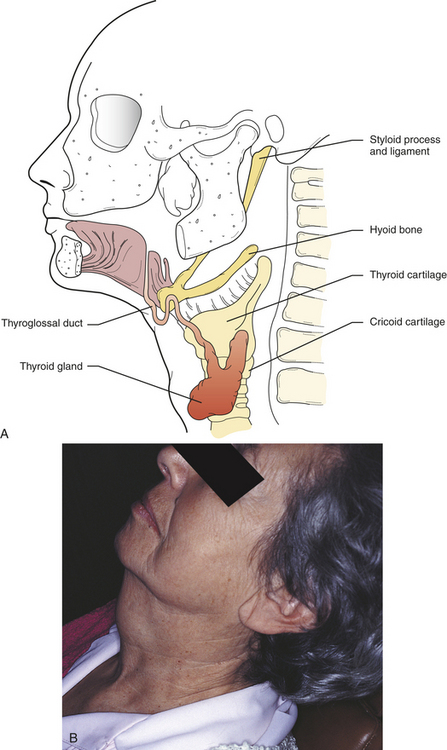

Thyroglossal Tract Cyst

A thyroglossal tract (duct) cyst forms along the same tract that the thyroid gland follows in development, from the area of the foramen cecum to its permanent location in the neck (Figure 5-17). Most of these cysts occur below the hyoid bone. The epithelial lining varies with location. Cysts above the hyoid bone are usually lined with stratified squamous epithelium, and those below the hyoid bone with ciliated columnar epithelium. Thyroid tissue may also be found within the connective tissue wall.

FIGURE 5-17 A, The thyroglossal tract extends from the area of the foramen cecum lingual to the lower part of the neck. B, A thyroglossal tract cyst is the cause of this enlargement at the midline of the neck.

The thyroglossal tract cyst is most often found in young individuals under 20 years of age. There is no sex predilection. Clinically if this cyst is located below the hyoid bone, it presents as a smooth bulge or swelling in the area of the midline of the neck. If located on the posterior aspect of the tongue, a smooth, rather firm mass of tissue is present, which can vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. The patient may complain of dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing) or difficulty when extending the tongue.

Treatment of a thyroglossal tract cyst consists of complete excision of the cyst and the tract, usually including a portion of the hyoid bone and muscle tissue along the thyroglossal tract. Generally prognosis is good, but a few cases of malignant transformation have been reported.

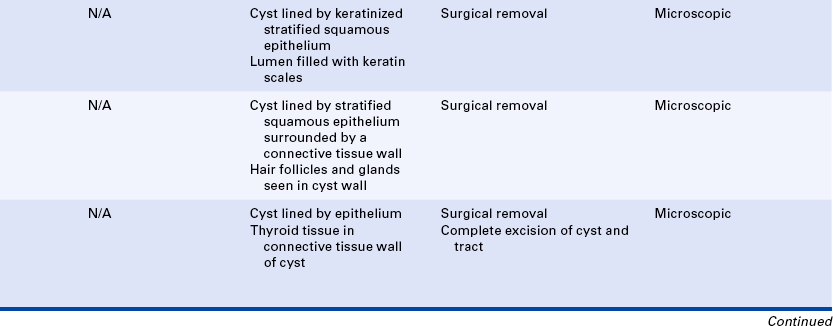

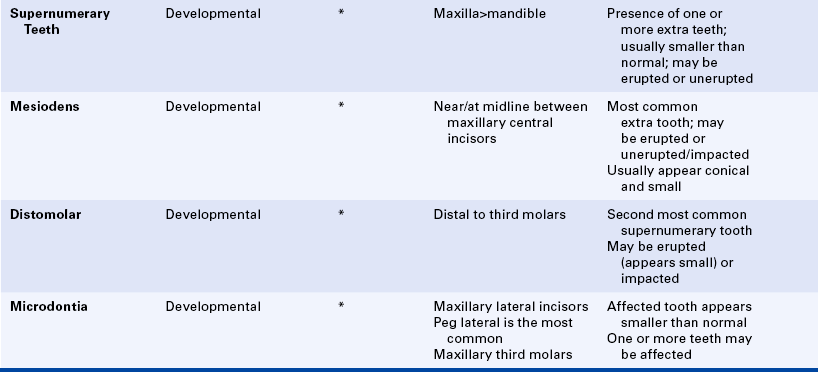

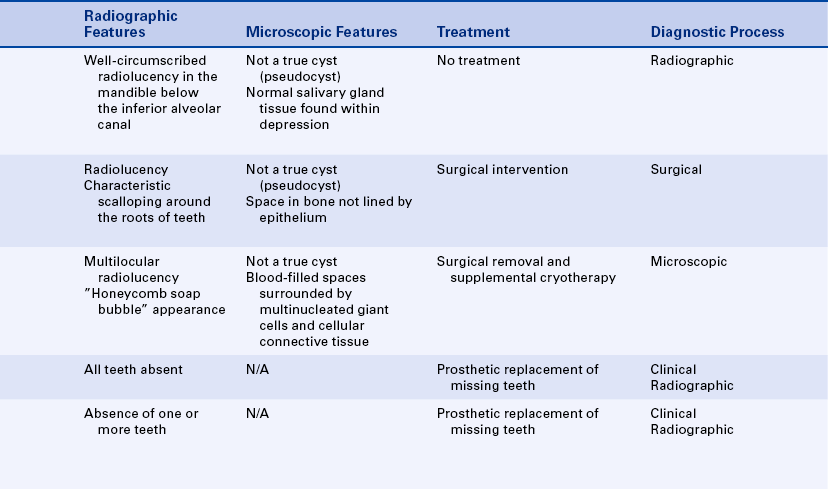

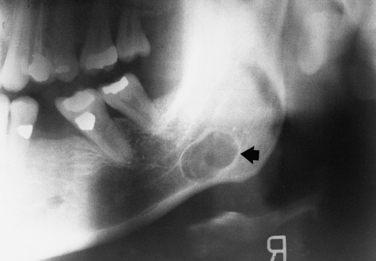

PSEUDOCYSTS

A static bone cyst (lingual mandibular bone concavity or Stafne bone defect) is not a true cyst because it is not a pathologic cavity and is not lined with epithelium. Therefore it is often referred to as a pseudocyst. Clinically, an anatomic depression may be felt on the posterior lingual area of the mandible. Radiographically a well-defined cystlike radiolucency is observed in this posterior region of the mandible, inferior to the mandibular canal. The radiolucency is caused by the lingual depression in the mandible, which is filled with normal salivary gland tissue (Figure 5-18). The salivary gland tissue may be an extension of the sublingual gland. The lesion is usually asymptomatic. There is a predilection in men.

FIGURE 5-18 Panoramic radiograph of a lingual mandibular bone concavity (Stafne bone cyst). Arrow points to a well-circumscribed radiolucency inferior to the mandibular canal.

This developmental defect requires no treatment. A sialogram can be used to identify salivary gland tissue. If any question exists about the diagnosis, the patient is followed until it is determined that no enlargement of the radiolucency has occurred. If the radiolucency occurs above the mandibular canal, a biopsy may be indicated to establish the diagnosis and differentiate this pseudocyst from cysts and tumors having a predilection for that location.

Simple Bone Cyst

A simple bone cyst (traumatic bone cyst) is a pathologic cavity in bone that is not lined with epithelium. The cause is uncertain, although an association with trauma has been suggested. The lesion is found most often in young individuals, and there is no sex predilection The lesion is observed radiographically as a well-defined unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion that characteristically shows scalloping around the roots of teeth (Figure 5-19). It is usually asymptomatic and is discovered on routine radiographs. Surgical intervention reveals a void within the bone. A curettage is performed on the wall lining the void to establish bleeding. The void or space fills up with bone 6 months to 1 year after the surgical procedure. Prognosis is excellent, and recurrence is unusual.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

An aneurysmal bone cyst is a pseudocyst that consists of blood-filled spaces surrounded by multinucleated giant cells and fibrous connective tissue (similar to the giant cell granuloma). There is no epithelial lining. The radiolucent lesion has a multilocular appearance that is often described as a “honeycomb” or “soap bubble.” It is usually seen in individuals under 30 years of age, and a slight predilection is reported in females. When in the jaws, the clinical presentation may include expansion of the involved bone.

A previous history of trauma to the area has been reported in some cases, but no direct correlation exists. Other reports have noted an association between the aneurysmal bone cyst and other bone lesions. It has frequently been associated with fibrous dysplasia, central giant cell granuloma, chondroblastoma, and other primary bone lesions. These other lesions cause a change in vascularity that results in the aneurysmal bone cyst. Surgical excision and supplemental cryotherapy are the recommended treatments for an aneurysmal bone cyst.

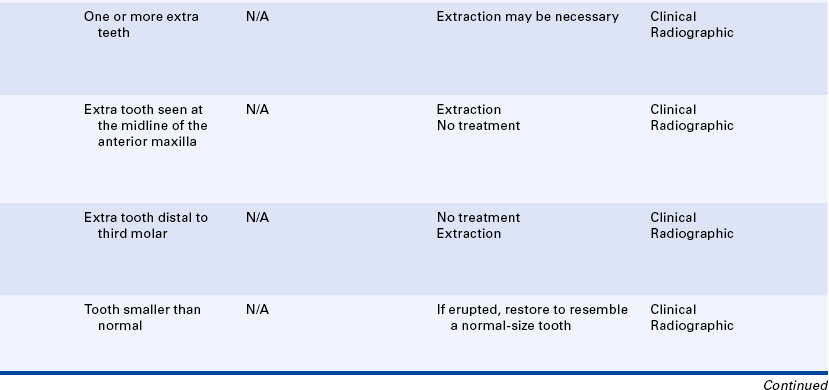

ABNORMALITIES IN THE NUMBER OF TEETH

Anodontia is the congenital lack of teeth. Total anodontia (lack of all teeth) is a rare condition that may affect either the deciduous or the permanent dentition. Because development of both deciduous and permanent teeth begins before birth, their failure to develop is congenital. However, teeth may not be identified as missing until the time of normal eruption or initial radiographic examination. Total anodontia is often associated with the hereditary disturbance ectodermal dysplasia, which is described in Chapter 6. Missing teeth require prosthetic replacement.

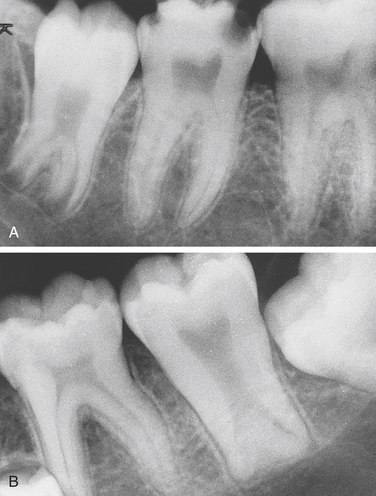

Hypodontia

Hypodontia is the lack of one or more teeth. This developmental anomaly is rather common and may affect either deciduous or permanent teeth (Figure 5-20). Any tooth in either dentition may be missing. The permanent dentition is most commonly affected. The teeth most often missing are the maxillary and mandibular third molars, the maxillary lateral incisors, and the mandibular second premolars. Teeth are often missing bilaterally. The mandibular incisor is the tooth most commonly missing in the deciduous dentition. Teeth are identified as congenitally lacking by careful clinical and radiographic examination along with a thorough patient history.

FIGURE 5-20 A and B, Hypodontia. Teeth missing have not been extracted; they never developed. (A courtesy Dr. George Blozis; B courtesy Dr. Margot Van Dis.)

Missing teeth tend to be familial (i.e., affecting more members of a family than would be expected by chance). In addition, factors such as jaw lesions in infancy and radiation therapy during tooth formation may result in the destruction of tooth germs and the subsequent lack of affected teeth.

Missing teeth may require prosthetic replacement. Their absence can also result in problems in occlusion caused by drifting or tipping of teeth. Orthodontic evaluation and treatment may be necessary. In addition, congenitally missing teeth may be a component of a syndrome. A syndrome is a group of findings that occur together. Patients with congenitally missing teeth should be evaluated for other abnormalities.

Supernumerary Teeth

Supernumerary teeth are extra teeth found in the dental arches (Figure 5-21). Supernumerary means more than the normal or regular number. Supernumerary teeth result from either the formation of extra tooth buds in the dental lamina or the cleavage of already existing tooth buds and may occur in either the deciduous or the permanent dentition. Extra teeth are most often seen in the maxilla and may occur singly or in multiples and unilaterally or bilaterally.

FIGURE 5-21 A, Supernumerary teeth. This patient has four maxillary lateral incisors. B, Radiograph showing unerupted supernumerary teeth. C, Supernumerary mandibular incisor. (A courtesy Dr. Margot Van Dis; B courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

Typically the supernumerary tooth is smaller than a normal-size tooth and often does not erupt. Most are discovered on radiographs as incidental findings. A supernumerary tooth may or may not resemble a normal tooth in shape and position.

The most common supernumerary tooth is called the mesiodens, which is located between the maxillary central incisors at or near the midline. It is usually a small tooth with a conical crown and short roots (Figure 5-22). It may occur singly or in pairs and may be inverted when seen on a radiograph. The mesiodens can erupt or remain embedded or impacted.

FIGURE 5-22 A, Mesiodens seen between the maxillary central incisors. B, Radiograph of an erupted mesiodens. C, Radiograph showing a pair of inverted impacted mesiodens. (A and B courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

The second most common supernumerary tooth is the maxillary fourth molar, which is also called a distomolar because it is located distal to the third molar (Figure 5-23 on p. 172). The distomolar can look like a miniature third molar or be of normal third molar size and shape. It rarely erupts into the oral cavity and is usually discovered on a radiograph.

FIGURE 5-23 A, Small erupted microdont distal to the maxillary second molar. B, Radiograph of a pair of distomolars located distal to the second molar. (A courtesy Dr. Margot Van Dis; B courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

Other supernumerary teeth include mandibular and maxillary premolars; maxillary lateral incisors; and the maxillary paramolar, a small rudimentary tooth that occurs buccal to the third molar. Erupted supernumerary teeth can cause crowding, malpositioning of adjacent teeth, or noneruption of normal teeth; therefore removal is often necessary. Nonerupted supernumerary teeth should be extracted because a risk exists for cyst development around the crown. Multiple supernumerary teeth may be a component of a syndrome such as cleidocranial dysplasia or Gardner syndrome. These syndromes are described in Chapter 6.

ABNORMALITIES IN THE SIZE OF TEETH

Microdontia is a developmental anomaly in which one or more teeth in a dentition are smaller than normal. The term is derived from the Greek words “mikros,” meaning small, and “odontos,” meaning tooth. Microdontia is classified as true generalized microdontia, generalized relative microdontia, or microdontia involving a single tooth.

True generalized microdontia is seen in the pituitary dwarf and is extremely rare. All the teeth are smaller than normal. In generalized relative microdontia normal-size teeth appear small in large jaws. Heredity plays a role in generalized relative microdontia. For example, a child may inherit large jaws from one parent and normal-size teeth from the other, resulting in the illusion of small teeth. Microdontia involving a single tooth is far more common than true generalized microdontia or generalized relative microdontia. The maxillary lateral incisor and the maxillary third molar are the teeth most often affected (Figure 5-24 on p. 172). The maxillary lateral incisors often appear peg shaped, with the mesial and distal tooth surfaces converging toward the incisal edge. This “peg lateral” is smaller than normal, tends to occur bilaterally, has short roots, and is thought to be familial. The maxillary third molar microdont typically appears small but normally shaped. Microdonts are identified clinically if erupted or radiographically if unerupted. For cosmetic reasons erupted microdonts may be restored to resemble teeth of normal size and shape. Impacted microdonts should be surgically removed to prevent cyst formation.

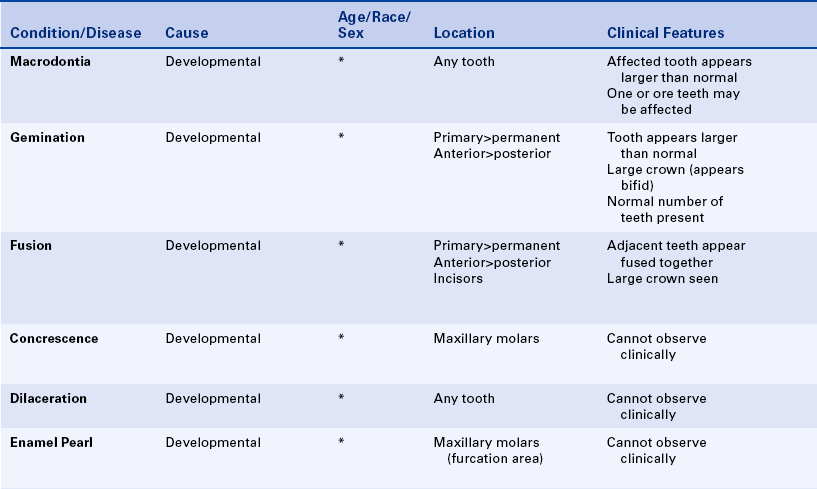

Macrodontia

Macrodontia is an uncommon developmental anomaly in which one or more teeth in a dentition are larger than normal. The term is derived from the Greek words “makros,” meaning large, and “odontos,” meaning tooth. Macrodontia is classified in the same manner as microdontia: true generalized macrodontia, relative generalized macrodontia, and macrodontia involving a single tooth.

True generalized macrodontia is rare and is seen occasionally in cases of pituitary gigantism. Relative generalized macrodontia is seen in individuals with normal or slightly larger than normal teeth in small jaws and is generally caused by the patient's inheriting tooth size from one parent and jaw size from the other. Macrodontia affecting a single tooth is uncommon. Localized macrodontia affecting one side of the dental arches may be seen in a condition called facial hemihypertrophy, which involves the enlargement of half of the head with enlarged teeth on the involved side. No treatment is indicated for macrodontia.

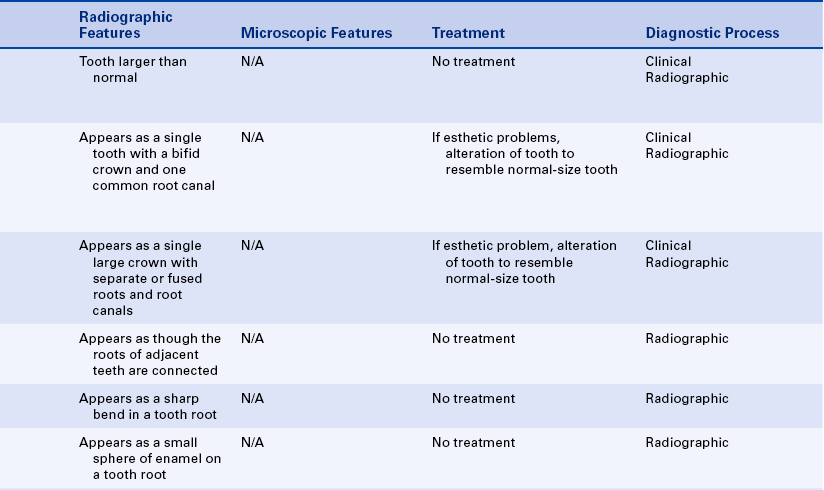

ABNORMALITIES IN THE SHAPE OF TEETH

Gemination is a developmental anomaly that occurs when a single tooth germ attempts to divide and results in the incomplete formation of two teeth. Geminate means paired or occurring in twos. The cause of this aborted twinning of a single tooth germ is unknown. Gemination is uncommon and is seen more frequently in the deciduous dentition, but occasionally it occurs in the permanent dentition. Gemination most often affects anterior teeth and is most often seen in the deciduous mandibular incisors and the permanent maxillary incisors.

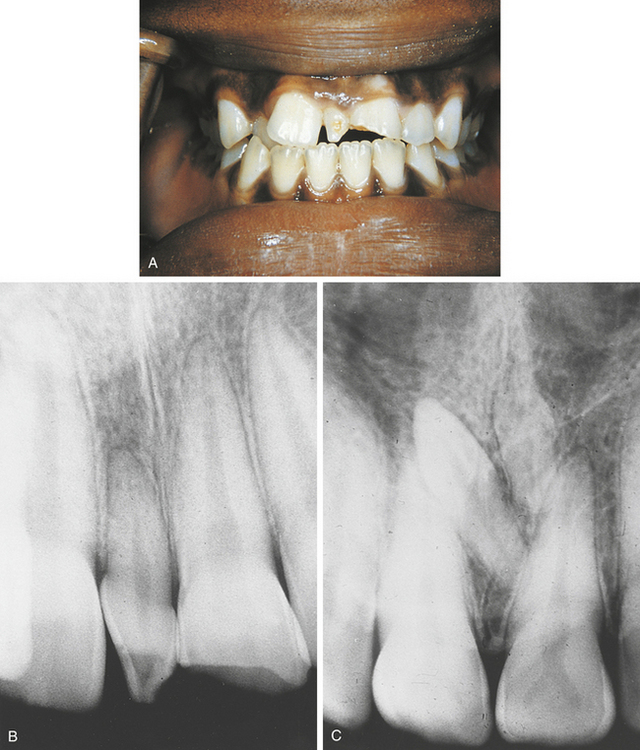

Clinically gemination appears as two crowns joined together by a notched incisal area (Figure 5-25, A and B on p.173). Radiographically usually one single root and one common pulp canal exist (Figure 5-25, C). The patient has a full complement of teeth.

FIGURE 5-25 A, Clinical picture of gemination in a mandibular cuspid. B, Gemination seen in a maxillary central incisor. C, Radiograph of the same maxillary central incisor. (A courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

A geminated tooth poses an aesthetic problem, particularly when it occurs in the maxillary anterior region. It also poses a prosthetic challenge. Therefore treatment usually involves alteration of the tooth so that it resembles a normal tooth in size and shape.

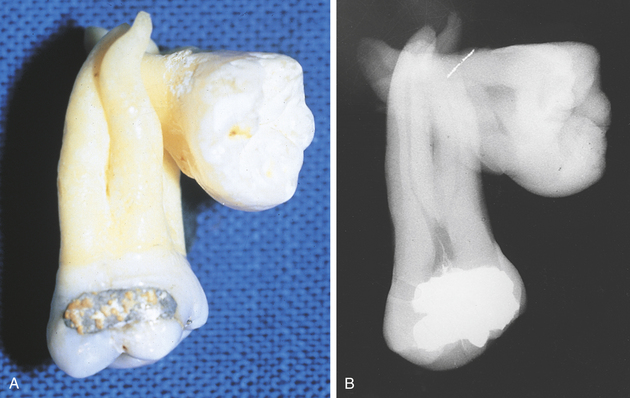

Fusion

Fusion results from the union of two normally separated adjacent tooth germs. The cause of fusion is uncertain; heredity, external pressure, and crowding all have been suggested. Fusion of adjacent teeth can be complete or incomplete, depending on the stage of tooth development at the time of contact. Early contact of developing tooth germs can result in a single large tooth; later contact can result in the union of crowns only or the union of roots only. True fusion always involves confluence of dentin. Fusion tends to occur in the anterior region, and the incisors are the teeth most often affected. Fusion of deciduous teeth occurs more often than fusion of permanent teeth.

Clinically fused teeth appear as a single large crown that occurs in place of two normal teeth and may exhibit an observable separation (Figure 5-26). Radiographically either separate or fused roots and root canals are seen. To differentiate fusion from gemination, the teeth must be counted. If the neighboring teeth of the tooth in question are present, the tooth is geminated; if a neighboring tooth is lacking, the tooth in question is fused. Fusion can occur between two adjacent normal teeth or between a normal tooth and a supernumerary tooth. It may be difficult to distinguish between a geminated tooth and the fusion of a normal tooth to a supernumerary tooth.

FIGURE 5-26 A, Clinical picture of fusion involving a permanent mandibular lateral incisor. B, Fusion of mandibular molars. (A courtesy Dr. George Blozis; B courtesy Dr. Rudy Melfi.)

As with geminated teeth, fused teeth may present aesthetic and occlusal problems; they also pose a restorative challenge. Treatment involves alteration of the size and shape of the tooth and may involve replacement of one of the fused teeth.

Concrescence

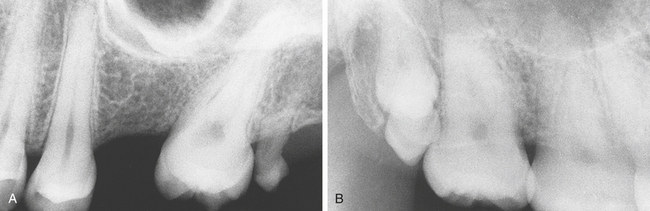

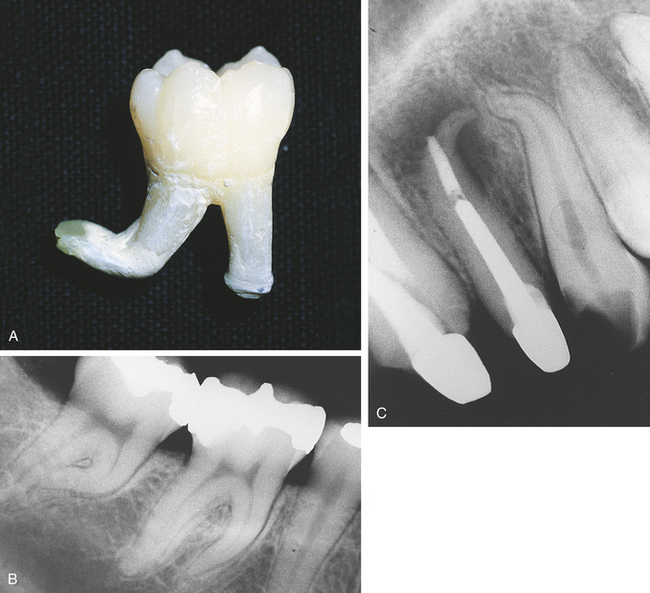

In dentistry concrescence is a condition in which two adjacent teeth are united by cementum only. It is actually a form of fusion that takes place after tooth formation is complete and is usually discovered as an incidental radiographic finding (Figure 5-27). The cause of concrescence is thought to be crowding or trauma that results in the close approximation of adjacent tooth roots. Subsequent cementum deposition acts to fuse the two adjacent roots. Concrescence is most often seen in adjacent maxillary molars and adjacent supernumerary teeth and may involve erupted, unerupted, or impacted teeth.

FIGURE 5-27 Concrescence illustrated in a photograph (A) of extracted teeth and in a corresponding radiograph (B). (Courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

Concrescence generally does not require treatment. If one of the teeth joined by cementum requires extraction, extraction of the fused neighbor is inevitable. However, the extraction of involved teeth is difficult, and excessive fracture of the associated alveolar bone may result.

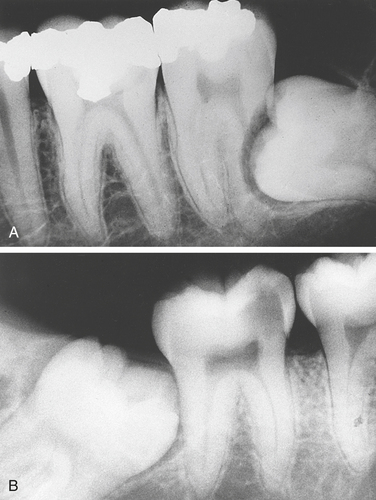

Dilaceration

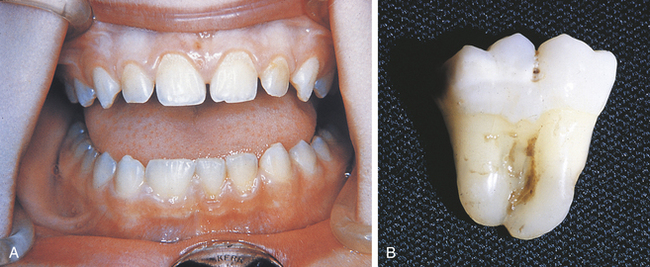

In dentistry dilaceration refers to an abnormal curve or angle in the root or, less frequently, the crown of a tooth (Figure 5-28 on p.175). This dental anomaly is thought to be caused by trauma to the tooth germ during root development. The position of the calcified portion of the tooth is changed, and the remainder of the tooth forms at an angle. A dilaceration can appear anywhere along the root portion of a tooth and can occur in any tooth in either the deciduous or the permanent dentition. A root dilaceration is usually discovered as an incidental radiographic finding.

FIGURE 5-28 A, Dilaceration on the distal root of an extracted tooth. B, Mesial root dilaceration on a mandibular second molar. C, Radiograph of root dilaceration in maxillary lateral and cuspid. (A courtesy Dr. Rudy Melfi.)

Dilacerations do not require treatment. However, they may cause problems if extraction or endodontic therapy becomes necessary. The importance of a preoperative radiograph is obvious.

Enamel Pearl

An enamel pearl, or enameloma, is a small, spheric enamel projection located on a root surface (Figure 5-29). This developmental anomaly is thought to occur as a result of the abnormal displacement of ameloblasts during tooth formation. The enamel pearl is usually found on maxillary molars. It is attached to cementum near the root bifurcation or trifurcation area. Occasionally it is located near the cementoenamel junction. The enamel pearl may consist of enamel only or enamel, dentin, and pulp.

The enamel pearl is an uncommon finding. It appears radiographically as a small, spheric radiopacity. Clinically the enamel pearl may be mistaken for calculus. Generally no treatment is necessary for this anomaly. Removal may be necessary if periodontal problems occur in the furcation area when an enamel pearl is present.

Talon Cusp

A talon cusp is an accessory cusp located in the area of the cingulum of a maxillary or mandibular permanent incisor (Figure 5-30 on p. 176). A talon is a claw of a predatory animal. The talon cusp is said to resemble an eagle's talon. It often projects lingually to the height of the incisal edge of the involved tooth. It is composed of normal enamel and dentin and contains a pulp horn. Frequently a caries-susceptible fissure is present between the cusps. Removal of the talon cusp is often indicated because it interferes with occlusion. Because of the presence of the pulp horn, endodontic therapy is necessary.

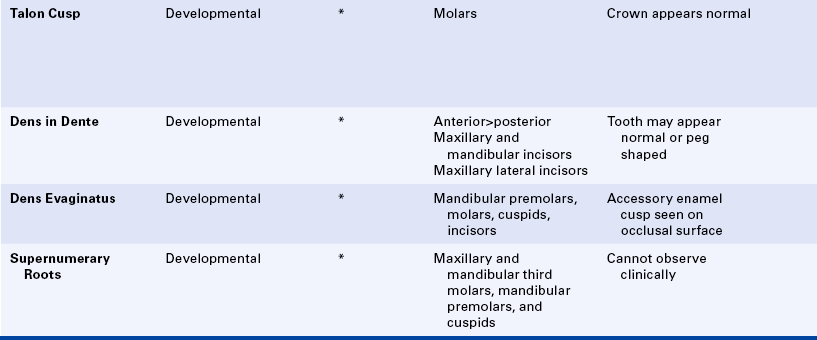

Taurodontism

Taurodontism is a term used to describe a developmental dental anomaly in which the teeth exhibit elongated, large pulp chambers and short roots (Figure 5-31). Taurodontism means “bull-like” teeth. The term was first used to describe teeth that resembled those of cud-chewing animals. Although the cause of taurodontism is uncertain, a variety of causes have been suggested, ranging from a primitive pattern of tooth development to the developmental failure of the Hertwig's epithelial root sheath to invaginate at the proper level.

FIGURE 5-31 A, Taurodont in the mandibular third molar. B, Taurodont in the mandibular second molar. (A courtesy Dr. Margot Van Dis; B courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

Taurodontism is uncommon and seen in both the deciduous and the permanent dentitions; it usually affects a single molar tooth or several molars in the same quadrant. Taurodontism can occur unilaterally or bilaterally. The crown of the tooth appears clinically normal. A taurodont is identified by its characteristic radiographic appearance. The tooth tends to have a stretched appearance, and the pulp chamber is greatly enlarged and elongated without a constriction at the cementoenamel junction. The roots appear short, with the furcation located near the apices. No treatment is indicated for taurodontism.

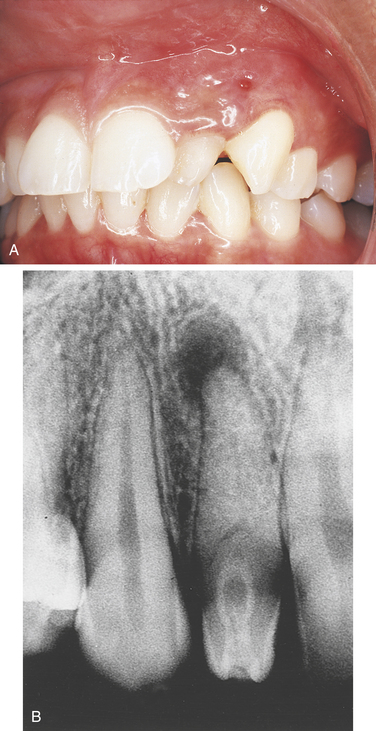

Dens in Dente

Dens in dente, also called dens invaginatus, is a developmental anomaly that results when the enamel organ invaginates into the crown of a tooth before mineralization (Figure 5-32 on p. 177). Invaginate means that one portion infolds into another portion of a structure. Radiographically a toothlike structure appears within the involved tooth. An elongated bulb or pear-shaped mass of enamel is seen in dentin surrounding a radiolucent area; hence the name dens in dente, or “tooth within a tooth.” This defect typically is confined to the coronal third of the tooth, but in some cases it extends to include the entire root length. Clinically the dens in dente may appear as either a normally shaped or malformed crown that exhibits a deep pit or crevice in the area of the cingulum. The invaginated toothlike structure retains a communication with the outside of the tooth via the pit or crevice visible on the crown surface.

FIGURE 5-32 A, Clinical illustration of dens in dente in maxillary lateral incisor. B, Radiograph of dens in dente in maxillary lateral incisor. (A courtesy Dr. George Blozis.)

Dens in dente customarily affects a single tooth. Anterior teeth, particularly the maxillary and mandibular incisors, are more commonly affected than the posterior teeth. The maxillary lateral incisor is the most frequently affected tooth, and when affected it is often peg shaped.

The dens in dente is vulnerable to caries, pulpal infection, and necrosis as a result of the communication between the oral cavity and the invaginated area of the tooth. Consequently the dens in dente is often nonvital and is seen in association with a periapical lesion (periapical cyst, periapical granuloma, periapical abscess). If the dens in dente is detected shortly after eruption, a prophylactic restoration can be placed in the deep pit or crevice to prevent caries and subsequent pulpal necrosis. A nonvital dens in dente may be treated endodontically. A malformed crown can be restored with composite materials or a full-coverage crown.

Dens Evaginatus

Dens evaginatus is an accessory enamel cusp found on the occlusal tooth surface (Figure 5-33). This is a rare developmental anomaly that occurs most often on the mandibular premolars. When affected, they are called tuberculated premolars. Molars, cuspids, and incisors can also be affected. Dens evaginatus is thought to result from the proliferation and outpouching of enamel epithelium during tooth development.

Clinically the dens evaginatus appears as a small, rounded nodule on the occlusal surface of a mandibular premolar between the buccal and lingual cusps. A pulp horn may extend into this extra cusp. The dens evaginatus may not require treatment. However, it can cause occlusal problems, and removal may be necessary. Occlusal wear or fracture of this accessory cusp may result in pulp exposure, and endodontic treatment may be necessary.

Supernumerary Roots

Supernumerary roots (extra roots) can involve any tooth (Figure 5-34). No cause for this developmental anomaly has been identified. External pressure, trauma, and metabolic dysfunction during root development have been suggested. Supernumerary roots are not uncommon and tend to occur in teeth that exhibit root formation after birth. The multirooted teeth most often affected are the maxillary and mandibular third molars. The single-rooted teeth most often affected are the mandibular bicuspids and cuspids. Supernumerary roots may exhibit dilaceration and are diagnosed radiographically.

Generally no treatment is indicated for supernumerary roots. However, they become clinically significant if extraction of the involved tooth or endodontic therapy becomes necessary.

ABNORMALITIES OF TOOTH STRUCTURE

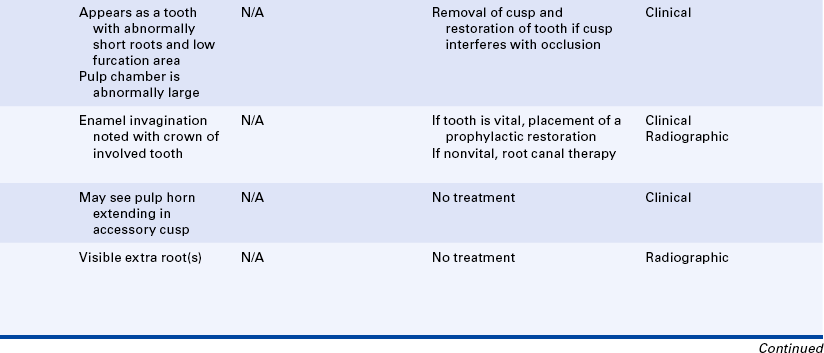

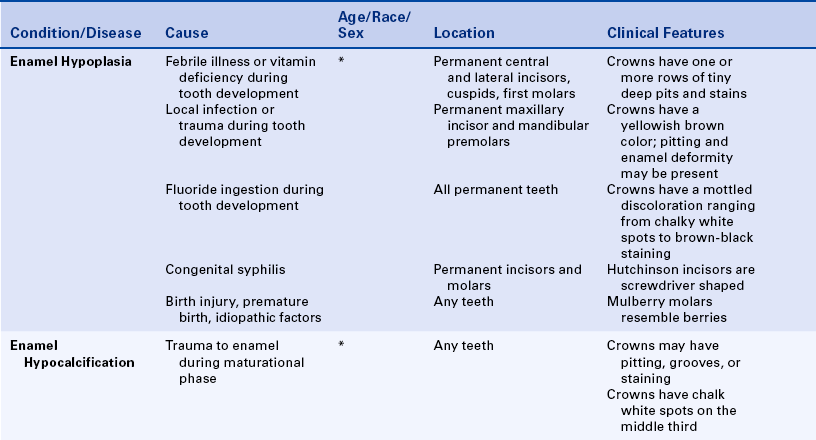

Enamel hypoplasia is the incomplete or defective formation of enamel, resulting in the alteration of tooth form or color. Hypoplasia is defined as the incomplete development of an organ or tissue. Enamel hypoplasia results from a disturbance of or damage to ameloblasts during enamel matrix formation. Enamel hypoplasia can affect either the deciduous or the permanent dentition.

Numerous factors can cause enamel hypoplasia:

Febrile illness (measles, chickenpox, scarlet fever)

Febrile illness (measles, chickenpox, scarlet fever)

Vitamin deficiency (vitamins A, C, D)

Vitamin deficiency (vitamins A, C, D)

Enamel hypoplasia that is inherited is called amelogenesis imperfecta (see Chapter 6). The factors that cause enamel hypoplasia by injuring the sensitive ameloblasts during enamel formation are discussed in this chapter.

Enamel Hypoplasia Caused by Febrile Illness or Vitamin Deficiency

Ameloblasts are one of the most sensitive cell groups in the body. It is believed that any serious systemic disease or severe nutritional deficiency is capable of producing enamel hypoplasia. Febrile illnesses (measles, chickenpox, and scarlet fever) and vitamin deficiencies (vitamins A, C, and D) that occur during the time of tooth formation can result in a type of enamel hypoplasia characterized by pitting of the enamel. Only the crowns of teeth that are developing at the time of the febrile illness or vitamin deficiency are affected.

This type of hypoplasia usually involves the permanent central incisors, laterals, cuspids, and first molars, which are the teeth that form during the first year of life. One or more horizontal rows of tiny, deep pits are seen traversing the affected tooth surface. The number and rows of pits may vary, depending on the extent and severity of injury to the ameloblasts. These enamel pits tend to stain and appear unsightly (Figure 5-35).

FIGURE 5-35 Enamel hypoplasia. In this patient the enamel hypoplasia follows a pattern that is suggestive of a systemic problem such as a high fever.

Teeth affected with enamel hypoplasia of the pitting type may be restored with composites during childhood and later with porcelain veneers or full-crown coverage.

Enamel Hypoplasia Resulting from Local Infection or Trauma

Enamel hypoplasia of a permanent tooth may result from infection of a deciduous tooth. A single tooth is usually affected and is referred to as a Turner tooth. A carious deciduous tooth with periapical involvement can disturb the ameloblasts of the underlying permanent tooth. The severity of the defect depends on the severity of the deciduous tooth infection, the degree of periapical tissue involvement, and the stage of development of the underlying permanent tooth.

The teeth most often affected are the permanent maxillary incisors and the permanent mandibular premolars. The clinical appearance of the affected tooth depends on the extent of the injury. The color of the enamel of these teeth may range from yellow to brown, or severe pitting and deformity may be involved. These enamel defects can frequently be identified radiographically before the eruption of the involved tooth. An anterior Turner tooth may be restored to provide an improved aesthetic appearance; a posterior Turner tooth may require a restoration to provide improved function.

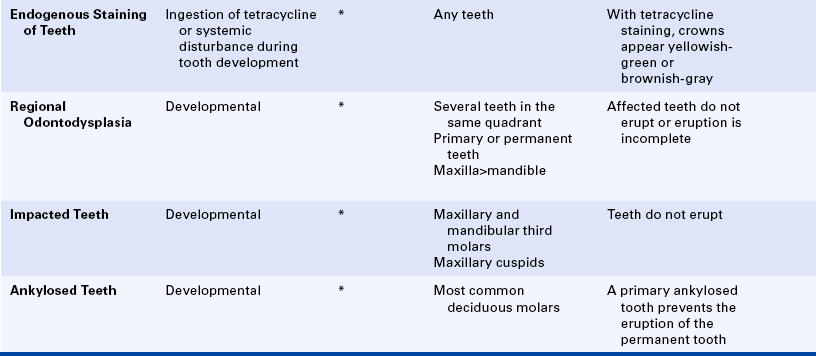

Enamel Hypoplasia Resulting from Fluoride Ingestion

Enamel hypoplasia resulting from fluoride ingestion, or dental fluorosis, occurs as a result of the patient ingesting high concentrations of fluoride during tooth formation, usually in drinking water. Affected teeth exhibit a mottled discoloration of enamel (Figure 5-36). Mottling refers to irregular areas of discoloration. The more fluoride ingested, the more severe the mottling. The optimum range of fluoride is 0.7 to 1.2 parts fluoride/million gallons of water. Ingestion of water with a fluoride concentration two to three times the recommended amount results in mild fluorosis that appears as white flecks and chalky opaque areas of enamel.

FIGURE 5-36 Mottled enamel. The discoloration of the enamel in this patient occurred as a result of high fluoride intake.

Ingestion of water containing four times the recommended amount of fluoride causes brown or black staining and a pitted or overall corroded enamel appearance.

All permanent teeth are involved in this type of enamel hypoplasia. The teeth affected by fluorosis are generally decay resistant. To improve the aesthetic appearance of these teeth, bleaching, bonding, composites, porcelain veneers, or full-coverage crowns can be used.

Enamel Hypoplasia Resulting from Congenital Syphilis

Syphilis is a contagious sexually transmitted disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. It is described in detail in Chapter 4. Congenital syphilis is transmitted from an infected mother to her fetus via the placenta. Children with congenital syphilis have numerous developmental anomalies and may be blind, deaf, or paralyzed. In utero infection by T. pallidum results in enamel hypoplasia of the permanent incisors and first molars. This is so rare that a lengthy discussion is not warranted.

The affected incisors are shaped like screwdrivers: broad cervically and narrow incisally, with a notched incisal edge (Figure 5-37, A). They are called Hutchinson incisors. First molars appear as irregularly shaped crowns made up of multiple tiny globules of enamel instead of cusps (Figure 5-37, B). Because of their berrylike appearance, these molars are called mulberry molars. Not every case of congenital syphilis exhibits these dental findings, and similarly shaped teeth may be seen in individuals without congenital syphilis.

Treatment to improve the aesthetic appearance of these teeth includes full-coverage crowns.

Enamel Hypoplasia Resulting from Birth Injury, Premature Birth, or Idiopathic Factors

Enamel hypoplasia can occur as a result of trauma or change of environment at the time of birth or in premature infants. In addition, many cases of enamel hypoplasia do not have an identifiable cause despite careful and thorough history taking. The ameloblast is a sensitive cell that is easily damaged. For this reason even a mild illness or systemic problem can result in enamel hypoplasia. Such illnesses may be so insignificant that they are not known to the patient or remembered by the patient's parents. To improve the aesthetic appearance of these teeth, composites, porcelain veneers, or full-coverage crowns can be used.

Enamel Hypocalcification

Enamel hypocalcification is a developmental anomaly that results in a disturbance of the maturation of the enamel matrix. It usually appears as a localized, chalky white spot on the middle third of smooth crowns. The underlying enamel may be soft and susceptible to caries. The cause of enamel hypocalcification is uncertain; however, trauma during the maturation of enamel matrix has been suggested. Bleaching, composites, porcelain veneers, or full-coverage crowns can be used to improve the aesthetic appearance of these teeth.

Endogenous Staining of Teeth

Endogenous or intrinsic staining of teeth occurs as a result of the deposition of substances circulating systemically during tooth development. For example, ingestion of tetracycline during tooth development causes a yellowish-green discoloration of dentin that is visible through the enamel. At the time of eruption the teeth fluoresce under ultraviolet light. Later the tetracycline is oxidized, the color changes from yellowish to brown, and the teeth no longer fluoresce. Other conditions such as rhesus (Rh) incompatibility (erythroblastosis fetalis), neonatal liver disease, and congenital porphyria (an inherited metabolic disease) also cause endogenous staining of teeth.

Regional Odontodysplasia

Regional odontodysplasia, or ghost teeth, is an unusual developmental problem in which one or several teeth in the same quadrant radiographically exhibit a marked reduction in radiodensity and a characteristic ghostlike appearance (Figure 5-38). Very thin enamel and dentin are present. Occasionally the enamel is not visible on the radiograph. The pulp chambers of these teeth are extremely large. Either the teeth do not erupt, or eruption is incomplete. If ghost teeth erupt into the oral cavity, they are typically nonfunctional and malformed.

Regional odontodysplasia can affect either the deciduous or the permanent dentition. The maxilla, especially the anterior maxilla, is more often involved than the mandible. The cause of regional odontodysplasia is unknown. A vascular phenomenon has been suggested. Extraction usually is the treatment of choice for ghost teeth.

ABNORMALITIES OF TOOTH ERUPTION

Impacted teeth are teeth that cannot erupt because of a physical obstruction. Embedded teeth are those that do not erupt because of a lack of eruptive force. An impacted tooth is one of the most common developmental defects occurring in humans. Any tooth can be impacted. The most commonly impacted teeth are the maxillary and mandibular third molars, the maxillary cuspids, the maxillary and mandibular premolars, and supernumerary teeth. Impacted teeth are identified radiographically (Figure 5-39).

FIGURE 5-39 A, Horizontal impaction of the third molar. B, Mesioangular impaction of the third molar.

Third molar impactions are classified according to the position of the tooth: mesioangular, distoangular, vertical, and horizontal. The most common position of an impacted third molar is mesioangular. The crown of the third molar points in a mesial direction and is in contact with the second molar, which is preventing its eruption. In a distoangular impaction the crown of the third molar points in a distal direction toward the ramus, and the roots of the impacted tooth are adjacent to the distal root of the second molar. In a vertical impaction the crown of the third molar is in a normal position for eruption, but eruption is prevented by the distal aspect of the second molar or by the anterior border of the ramus. In a horizontal impaction the crown of the third molar is seen in a horizontal position relative to the inferior border of the mandible.

Teeth can be completely impacted in bone with no communication with the oral cavity, or they can be partially impacted. In a partial impaction the tooth lies partly in soft tissue and partly in bone. Partially impacted teeth often have a communication with the oral cavity and are susceptible to infections (see Pericoronitis, Chapter 4). For unknown reasons some completely impacted teeth undergo resorption. This resorption usually begins in the crown portion of the tooth, and the tooth is slowly replaced by bone. Radiographically this resorption should not be confused with caries. Caries of an impacted tooth is impossible unless communication with the oral cavity occurs.

Impacted teeth are surgically removed to prevent odontogenic cyst and tumor formation or damage (resorption) to adjacent teeth or because the bone (in some cases) may be more susceptible to fracture. Partially impacted third molars are removed to prevent infections. Studies have shown that the optimal time to extract impacted third molars is between the ages of 12 and 24 years. With increased age a greater incidence of nerve paresthesia exists.

Ankylosed Teeth

Ankylosed (or submerged) teeth are deciduous teeth in which bone has fused to cementum and dentin, preventing exfoliation of the deciduous tooth and eruption of the underlying permanent tooth (Figure 5-40). Deciduous molars are most often affected by ankylosis. The cause is unknown; trauma and infection of the periodontal ligament have been suggested.

Initially the tooth erupts into the oral cavity into normal occlusion. The ankylosed tooth is not exfoliated. When the permanent teeth erupt, those adjacent to the ankylosed tooth have taller occlusocervical heights. Compared with the adjacent teeth, the ankylosed tooth appears submerged and has a different, more solid sound when percussed.

The presence of an ankylosed tooth is usually suspected on the basis of the clinical appearance and is confirmed radiographically. The periodontal ligament space is lacking or indistinct because of the union of bone and cementum, and the tooth usually exhibits root resorption. Ankylosis may be seen in permanent teeth that have been avulsed and reimplanted.

Extraction of ankylosed deciduous teeth is necessary to allow eruption of the underlying permanent tooth. Extraction of ankylosed permanent teeth is often necessary to prevent malocclusion, caries, and periodontal disease.

Alley, K.E., Melfi, R.C. Permar's oral embryology and microscopic anatomy, ed 10. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

Darby, M. Mosby's comprehensive review of dental hygiene, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby; 2006.

Langlais, R.P., Miller, C.S. Color atlas of common oral diseases, ed 3. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Miller, B.F. Miller-Keane encyclopedia and dictionary of medicine, nursing, and allied health—revised reprint, ed 7. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

Neville, B.W., Damm, D.D., Allen, C.M. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 3. St. Louis: Saunders; 2009.

Regezi, J.A., Sciubba, J.J., Jordan, R.C.K. Oral pathology: clinical-pathologic correlations, ed 5. St Louis: Saunders; 2008.

Regezi, J.A., Sciubba, J.J., Pogrel, M.A. Atlas of oral and maxillofacial pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000.

Scheid, R.C. Woelfel's dental anatomy: its relevance to dentistry, ed 7. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Alexander, W.N., Lilly, G.E., Irby, W.B. Odontodysplasia. Oral Surg. 1966;22:814.

Alfors, E., Larson, A., Sjögren, S. The odontogenic keratocyst: a benign cystic tumor? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984;42:10.

Al-Talabani, N.G., Smith, C.J. Experimental dentigerous cysts and enamel hypoplasia: their possible significance in explaining the pathogenesis of dentigerous cysts. J Oral Pathol. 1980;9:82.

Baker, B.R. Pits of the lip commissures in Caucasoid males. Oral Surg. 1966;21:56.

Barker, G.R. A radiolucency of the ascending ramus of the mandible associated with invested parotid salivary gland material and analogous with a Stafne bone cavity. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:81.

Baum, B.J., Cohen, M.M. Patterns of size reduction in hypodontia. J Dent Res. 1971;50:779.

Bodin, I., Julin, P., Thomsson, M. Hyperdontia III: supernumerary anterior teeth. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1981;10:35.

Bodin, I., Julin, P., Thomsson, M. Hyperdontia IV: supernumerary premolars. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1981;19:99.

Brannon, R.B. The odontogenic keratocyst—a clinicopathologic study of 312 cases. I. Clinical features. Oral Surg. 1976;42:54.

Brannon, R.B. The odontogenic keratocyst—a clinicopathologic study of 312 cases. II. Histologic features. Oral Surg. 1977;43:233.

Buchner, A., Hansen, L.S. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the oral cavity: a clinicopathologic study of 38 cases. Oral Surg. 1980;50:441.

Burton, D.J., Saffos, R.O., Scheffer, R.B. Multiple bilateral dens in dente as a factor in the etiology of multiple periapical lesions. Oral Surg. 1980;49:496.

Carter, L., Carney, Y., Perez-Pudlewski, D. Lateral periodontal cyst: multifactorial analysis of a previously unreported series. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:210.

Cavanha, A.O. Enamel pearls. Oral Surg. 1965;19:373.

Christ, T.F. The globulomaxillary cyst—an embryologic misconception. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;30:515.

Conklin, W.W. Bilateral dens invaginatus in the mandibular incisor region. Oral Surg. 1978;45:905.

Dachi, S.F., Howell, F.V. A survey of 3874 routine full-mouth radiographs. II. A study of impacted teeth. Oral Surg. 1961;14:1165.

Darling, A.I., Levers, B.G.H. Submerged human deciduous molars and ankylosis. Arch Oral Biol. 1973;18:1021.

Dean, H.T., Arnold, F.A. Endemic dental fluorosis or mottled teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1943;30:1278.

Dehlers, F.A.C., Lee, K.W., Lee, E.C. Dens evaginatus (evaginated odontoma). Dent Pract. 1967;17:239.

Delany, G.M., Goldblatt, L.I. Fused teeth: a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981;103:732.

DiFiore, P.M., Hartwell, G.R. Median mandibular lateral periodontal cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:545.

Eisenbud, L.E., et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:202.

el-Mofty, S.K., Shannon, M.T., Mustoe, T.A. Lymph node metastasis in spindle cell carcinoma arising in an odontogenic cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:209.

Everett, F.G., Wescott, W.B. Commissural lip pits. Oral Surg. 1961;14:202.

Fantasia, J.E. Lateral periodontal cyst: an analysis of 46 cases. Oral Surg. 1979;48:237.

Freedman, P.D., Lumerman, H., Gee, J.K. Calcifying odontogenic cyst. Oral Surg. 1975;40:93.

Gardner, D.G. An evaluation of reported cases of median mandibular cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:208.

Gardner, D.G. The dentinal changes in regional odontodysplasia. Oral Surg. 1974;38:887.

Gardner, D.G., Girgis, S.S. Taurodontism, shovel-shaped incisors and the Klinefelter syndrome. J Can Dent Assoc. 1978;8:372.

Gardner, D.G., Sapp, J.P. Regional odontodysplasia. Oral Surg. 1973;35:351.

Grahnen, H., Granath, L.E. Numerical variations in primary dentition. Odontol Revy. 1961;12:342.

Grahnen, H., Larsson, P.G. Enamel defects in deciduous dentition of prematurely born children. Odontol Rev. 1958;9:143.

Hamner, J.E., III., Witko, C.J., Metro, P.S. Taurodontism: report of a case. Oral Surg. 1964;18:409.

Henderson, H.Z. Ankylosis of primary molars: a clinical, radiographic, and histologic study. J Dent Child. 1979;46:117.

Hernandez, G.A., et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst versus hemangioma of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:790.

Holt, R.D., Brook, A.H. Taurodontism: a criterion for diagnosis and its prevalence in mandibular first molars in a sample of 1115 British school children. J Int Assoc Dent Child. 1979;10:41.

Howell, R.E., et al. CEA immunoreactivity in odontogenic tumors and keratocysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:576.

Jasmin, J., Ionesco-Benaiche, N., Muller, M. Latent fluorides: report of a case. J Dent Child. 1995;62:220.

Keith, A. Problems relating to the teeth of the earlier forms of prehistoric man. Proc R Soc Med. 1913;6(part 3):103.

Kelly, J.R. Gemination, fusion, or both? Oral Surg. 1978;45:326.

King, R.C., Smith, B.R., Burk, J.L. Dermoid cyst in the floor of the mouth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:567.

Kitchin, P.C. Dens in dente. J Dent Res. 1935;15:1176.

Krolls, S.O., Donalhue, A.H. Double-rooted maxillary primary canines. Oral Surg. 1980;49:379.

Leamas, R., Jimenez-Planas, A. Taurodontism in premolars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75:501.

Mathewson, R.J., Siegel, M.J., McCanna, D.L. Ankyloglossia: a review of the literature and a case report. J Dent Child. 1966;33:238.

Maurette, P.E., Jorge, J., deMoraes, M. Conservative treatment protocol of the odontogenic keratocyst. J.Oral and Maxillofacial Surg. 2006;64:379–3383.

Mellor, J.K., Ripa, L.W. Talon cusp: a clinically significant anomaly. Oral Surg. 1970;29:224.

Milazzo, A., Alexander, S.A. Fusion, gemination, oligodontia and taurodontism. J Pedodontics. 1982;6:194.

Mlynarczyk, G. Enamel pitting: a common symptom of tuberous sclerosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:63.

Morningstar, C.H. Effect of infection of deciduous molar on the permanent tooth germ. J Am Dent Assoc. 1937;24:786.

Partridge, M., Towers, J.F. The primordial cyst (odontogenic keratocyst): its tumor-like characteristics and behavior. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:271.

Pendrys, D.G. Dental fluorosis in perspective. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:63.

Ray, G.E. Congenital absence of permanent teeth. Br Dent J. 1951;90:213.

Reaume, C.E., Sofie, V.L. Lingual thyroid: review of the literature and a report of a case. Oral Surg. 1978;45:841.

Redman, R.S. Respiratory epithelium in an apical periodontal cyst of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:77.

Rushton, M.A. Invaginated teeth (dens in dente): contents of the invagination. Oral Surg. 1958;11:1378.

Rushton, M.A. Odontodysplasia: “ghost teeth,”. Br Dent J. 1965;119:109.

Sapp, P.J., Stark, M. Self-healing traumatic bone cysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:597.

Shafer, W.G. Dens in dente. NY Dent J. 1953;19:220.

Suchina, J.A., Ludington, J.R., Jr., Madden, R.M. Dens invaginatus of a maxillary lateral incisor: endodontic treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:467.

Tolson, G., et al. Report of a lateral periodontal cyst and gingival cyst in the same patient. J Periodontol. 1996;67:541.

Trope, M. Root resorption of dental and traumatic origin: classification based on etiology. Pract Periodontics Anesthet Dent. 1998;10(4):515.

van Gool, A.V. Injury to the permanent tooth germ after trauma to the deciduous predecessor. Oral Surg. 1973;35:2.

Vorheis, J.M., Gregory, G.T., McDonald, R.E. Ankylosed deciduous molars. J Am Dent Assoc. 1952;44:68.

Weinmann, J.P., Svoboda, J.F., Woods, R.W. Hereditary disturbances of enamel formation and calcification. J Am Dent Assoc. 1945;32:397.

Yip, W.K. The prevalence of dens evaginatus. Oral Surg. 1974;38:80.

Yoshikazu, S., Tanimoto, K., Wada, T. Simple bone cyst: evaluation of contents with conventional radiography and computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:296.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Which term refers to a defect present at birth?

2. Which term refers to the origin and tissue formation of teeth?

3. Which term refers to the joining of teeth by cementum only?

4. Which teeth are most often missing?

5. Which tooth is the most common supernumerary tooth?

6. Which teeth most often appear smaller than normal?

7. Which term refers to the developmental anomaly that arises when a single tooth germ attempts to divide and results in the incomplete formation of two teeth?

8. Which term refers to the developmental anomaly that arises from the union of two normally separated adjacent tooth germs?

9. Which term refers to an abnormal angulation or curve in the root or crown of a tooth?

10. Which term refers to a developmental anomaly in which teeth exhibit elongated, large pulp chambers and short roots?

11. Which developmental anomaly is often associated with a nonvital tooth and periapical lesions?

12. Which of the following teeth most often exhibit supernumerary roots?

13. Which one of the following describes the appearance of enamel hypoplasia resulting from a febrile illness or vitamin deficiency?

14. Which one of the following is associated with enamel hypoplasia resulting from congenital syphilis?

15. Which one of the following describes the appearance of enamel hypocalcification?

16. Which term describes a tooth that has not erupted because of the lack of eruptive force?

17. Which teeth are most often impacted?

18. Which term describes a tooth in which bone has fused to cementum and dentin and prevents the eruption of an underlying permanent tooth?

19. Which cyst is not an odontogenic cyst?

20. The most common cause of the periapical cyst is:

21. Which cyst is an odontogenic intraosseous cyst that forms around the crown of a developing tooth?

22. Which cyst develops in place of a tooth?

23. Which cyst is characterized by its unique histologic appearance and frequent recurrence?

24. The lateral periodontal cyst is defined by its location. In which area is the lateral periodontal cyst most commonly found?