Infectious Diseases

After studying this chapter, the student will be able to:

1 State the difference between an inflammatory and an immune response to infection.

2 Describe the factors that allow opportunistic infection to develop.

3 List two examples of opportunistic infections that can occur in the oral cavity.

4 For each of the following infectious diseases, name the organism causing it, list the route or routes of transmission of the organism and the oral manifestations of the disease, and describe how the diagnosis is made: impetigo, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, syphilis (primary, secondary, tertiary), verruca vulgaris, condyloma acuminatum, and primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

5 Describe the relationship between streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis and scarlet fever and rheumatic fever.

6 List and describe four forms of oral candidiasis.

7 Describe the clinical features of herpes labialis.

8 Describe the clinical features of recurrent intraoral herpes simplex infection and compare them with the clinical features of minor aphthous ulcers.

9 Describe the clinical characteristics of herpes zoster when it affects the skin of the face and oral mucosa.

10 List two oral infectious diseases for which a cytologic smear may assist in confirming the diagnosis.

11 List four diseases associated with the Epstein-Barr virus.

12 List two diseases caused by coxsackieviruses that have oral manifestations.

13 Describe the spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, including initial infection and the development of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

14 List and describe the clinical appearance of five oral manifestations of HIV infection.

(gran′′u-lo′mah) A tumorlike mass of inflammatory tissue consisting of a central collection of macrophages, often including multinucleated giant cells, surrounded by lymphocytes.

(gran′′u-lom′ah-tus dĭ-zēz′) A disease characterized by the formation of granulomas.

(in′′ku-ba'shĕn pir-ē-ĕd)The period between the infection of an individual by a pathogen and the manifestation of the disease it causes.

(mah-l z′) A vague, indefinite feeling of discomfort, debilitation, or lack of health.

z′) A vague, indefinite feeling of discomfort, debilitation, or lack of health.

(op′′or-tu-nis′tik in-fek'shun) A disease caused by a microorganism that does not ordinarily cause disease but becomes pathogenic under certain circumstances.

(par′′ĕs-the′zhĕ) An abnormal sensation such as prickling or tingling.

(path-o-jen′ik mi′′kro-or′gan-izm) A microorganism that causes disease.

(proo-ri′tĕs) Itching.

An infectious disease not detectable by the usual clinical signs. (sĕb-klinĭ-kel)

(hwit′lo) An infection involving the distal phalanx of a finger.

Humans are surrounded and inhabited by an enormous number of microorganisms. The ability of these organisms to cause disease depends on both the microorganism and the state of the body's defenses. The organism must be capable of causing disease, and the individual must be susceptible to the disease. Microorganisms are traditionally divided into those that produce disease (pathogenic) and those that do not (nonpathogenic). To cause disease the organism must gain access to the body, accommodate to growth in the human environment, and avoid multiple host defenses. These defense mechanisms include intact skin and mucosal surfaces, antimicrobial secretory and excretory products on the skin and mucosa, the competition among the components of the normal microflora, the inflammatory response, and the immune response.

Numerous infectious diseases can affect the tissues of the oral cavity. Bacterial, fungal, and viral infections are the most common; but even protozoan and helminthic infections, although extremely rare, have been reported.

The oral cavity can be the primary site of involvement of an infectious disease, or a systemic infection can have oral manifestations. These infections are transmitted from one individual to another by several different routes. Organisms can be transferred through the air on dust particles or water droplets. Some organisms require intimate and direct contact to be transferred. Some can be transferred on hands and objects, and others such as hepatitis B must be transferred from one person to another in blood or other body fluids. Microorganisms initially invading the oral tissues can cause a local infection, systemic infection, or both. Microorganisms circulating in the bloodstream can cause lesions in the oral cavity, and microorganisms causing infection in the lungs can be transferred to oral tissues when they are present in sputum. The oral cavity contains numerous microorganisms that make up the normal oral microflora. Changes such as a decrease in salivary flow, antibiotic administration, and immune system alterations affect the oral microflora so that organisms that are usually nonpathogenic are able to cause disease. This type of infection is called an opportunistic infection.

Microorganisms penetrating epithelial surfaces act as foreign material and stimulate the inflammatory response (see Chapter 2). The inflammatory response is a nonspecific response and results in edema and the accumulation of a large number of white blood cells at the site. The responses of the immune system are highly specific (see Chapter 3). Specific antibodies are formed in response to specific antigens; microorganisms are antigens.

Humoral immunity (immunity that is mediated by antibodies) is an effective defense against some microorganisms, and cell-mediated immunity (immunity in which T-lymphocytes are responsible for the respons) is the primary defense against others such as intracellular bacteria (tuberculosis), viruses, and fungi. Microbial infections are responsible for many more diseases than those included in this chapter. The diseases discussed here are common, cause specific oral lesions, and help to illustrate principles of infectious disease. Dental caries and periodontal disease clearly are infectious diseases that are important to dental hygienists. However, they are not included in this text because they are usually studied in courses other than oral pathology. The dental hygienist frequently encounters oral infectious diseases and must be able to recognize their clinical features and significance for control of infection.

IMPETIGO

Impetigo is a bacterial skin infection caused primarily by Staphylococcus aureus and occasionally by Streptococcus pyogenes. Impetigo most commonly involves the skin of the face or extremities and is usually seen in young children. The organisms are present on skin, and nonintact skin is necessary for infection; areas of trauma such as cuts and abrasions and areas of dermatitis are likely sites of this infection. The lesions of impetigo are infectious. Direct contact is required for transmission. Impetigo presents as either vesicles that rupture, resulting in thick, amber-colored crusts, or longer-lasting bullae. Lesions may itch (pruritus), and regional lymphadenopathy may be present. Systemic manifestations such as fever and malaise generally do not occur with this infection. When impetigo affects the perioral skin, the lesions may resemble recurrent herpes simplex infection (Herpes simplex infection is discussed later in this chapter). However, recurrent herpes simplex infection is much less common than impetigo in small children. The diagnosis of impetigo is made on the basis of the clinical presentation or by identification of the bacteria from cultures of the lesions. Topical or systemic antibiotics are used for treatment.

TONSILLITIS AND PHARYNGITIS

Tonsillitis and pharyngitis are inflammatory conditions of the tonsils and pharyngeal mucosa. Many different organisms cause them, including streptococci, adenoviruses, influenza viruses, and Epstein-Barr virus. The clinical features include sore throat, fever, tonsillar hyperplasia, and erythema of the oropharyngeal mucosa and tonsils.

Streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis are common bacterial infections that are spread by contact with infectious nasal or oral secretions. The appearance of streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis (i.e., “strep throat”) closely resembles tonsillitis and pharyngitis caused by other infections such as viral infections. Specific laboratory tests, including a rapid antigen detection test, are available for diagnostic confirmation of streptococcal infection. Antibiotics are used to treat streptococcal infection.

Tonsillitis and pharyngitis caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococci are significant because of their relationship to scarlet fever and rheumatic fever. Scarlet fever usually occurs in children. In addition to fever, patients with scarlet fever develop a generalized red skin rash that is caused by a toxin released by the bacteria. In addition to streptococcal tonsillitis and pharyngitis, oral manifestations of scarlet fever include petechiae on the soft palate and an appearance of the tongue that has been called strawberry tongue. The fungiform papillae are red and prominent, with the dorsal surface of tongue exhibiting either a white coating or erythema. Throat culture is helpful in confirming the diagnosis of stretpcocally pharyngitis in a patient with scarlet fever.

Rheumatic fever is a childhood disease that follows a group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection, usually tonsillitis and pharyngitis. Rheumatic fever is characterized by an inflammatory reaction involving the heart, joints, and central nervous system. Rheumatic fever may result in permanent damage to heart valves.

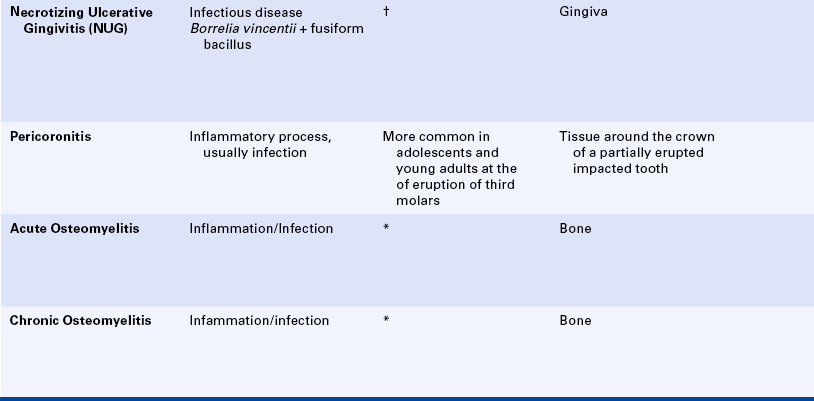

TUBERCULOSIS

Tuberculosis is an infectious chronic granulomatous disease usually caused by the organism Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The chief form of the disease is a primary infection of the lung. Inhaled droplets containing bacteria lodge in the alveoli of the lungs. After undergoing phagocytosis by macrophages, the organisms are resistant to destruction and multiply in the macrophages. They then disseminate in the bloodstream. After a few weeks dissemination ceases. The signs and symptoms of this lung infection include fever, chills, fatigue and malaise, weight loss, and persistent cough. The bacteria can be carried to widespread areas of the body and cause involvement of organs such as the kidneys and liver. This is called miliary tuberculosis. Involvement of the submandibular and cervical lymph nodes (usually as a result of ingesting the organism in nonpasteurized milk) causes enlargement of those nodes and is called scrofula or tuberculous lymphadenitis. The lung infection can occur at any age. Most commonly foci of infection in the lungs become completely walled off and heal by fibrosis and calcification. A reactivation of the primary lesion can occur years after the initial infection. This reactivation is usually a result of a compromised immune response.

Oral lesions associated with tuberculosis occur but are rare. They most likely appear when organisms are carried from the lungs in sputum and transmitted to the oral mucosa (Figure 4-1). The tongue and palate are the most common sites for oral lesions of tuberculosis, but they may occur anywhere in the oral cavity, even in bone as in osteomyelitis. Oral lesions appear as painful, nonhealing, slowly enlarging ulcers that can be either superficial or deep.

Diagnosis

Oral lesions of tuberculosis are identified by biopsy and microscopic examination of the tissue. The characteristic histopathologic lesions of tuberculosis are granulomas. The granulomas are composed of areas of necrosis surrounded by macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes. Similar lesions occur in sarcoidosis, deep fungal infections, and foreign-body reactions. Staining the tissue to be examined microscopically with a special stain may reveal the organisms. Tissue culture to diagnose tuberculosis requires a specialized laboratory.

A skin test is used to determine if an individual has been exposed and infected with M. tuberculosis. An antigen called purified protein derivative is injected into the skin. If the individual's immune system has previously encountered the antigen, a positive inflammatory skin reaction occurs (a type IV delayed-hypersensitivity reaction). This skin reaction indicates previous infection with the bacteria but not necessarily active disease. When a skin test result is positive, chest radiographs are taken to determine if active tuberculosis disease is present.

Effective drug treatment for tuberculosis became available in the 1940s. In the United States most tuberculosis treatment centers had closed by the mid-1970s. State health departments reported a dramatic increase in new cases in the mid-1980s, particularly in densely populated urban areas. This increase was suggested to be related to human immunodeficiency virus infection and to noncompliance of patients with therapy. Recent public health efforts have focused on ensuring compliance with antituberculosis drug treatment; as a result the number of new cases reported has decreased.

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that can be transmitted occupationally to dental health care personnel. Routine use of universal precautions, including eye protection, mask, or facial shield, is important in preventing the transmission of airborne droplet infections such as tuberculosis. However, for patients with active tuberculosis, routine dental treatment is deferred. When emergency dental treatment is needed, the use of a special mask is recommended to ensure prevention of transmission of the tuberculosis organism.

Treatment and Prognosis

Oral lesions resolve with treatment of the patient's primary (usually pulmonary) disease. Several different combination medications, including isoniazid and rifampin, are used to treat tuberculosis. Treatment continues for many months and may continue for as long as 2 years. Patients usually become noninfectious shortly after treatment begins. Consultation with the patient's physician should confirm that treatment is ongoing and the patient is no longer infectious.

ACTINOMYCOSIS

Actinomycosis is an infection caused by a filamentous bacterium called Actinomyces israelii. These organisms were at one time thought to be fungi; therefore the name ends in the suffix “mycosis,” which usually indicates a fungal infection.

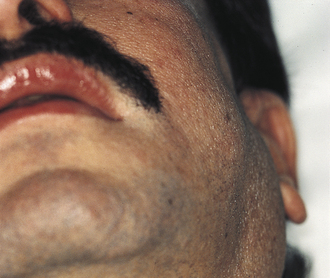

The most characteristic form of the disease is the formation of abscesses that tend to drain by the formation of sinus tracts (Figure 4-2). The colonies or organisms appear in the pus as tiny, bright yellow grains and are called sulfur granules because of their yellow color. The organisms can also be identified by microscopic examination. These organisms are common inhabitants of the oral cavity. It is not clear why they only occasionally cause disease. Predisposing factors have not been identified. The infection is often preceded by tooth extraction or an abrasion of the mucosa.

FIGURE 4-2 Actinomycosis. Skin lesion over mandible. Incision and drainage site seen below lesion. “Sulfur granules” were noted in the laboratory report, and the condition was treated with long-term antibiotic therapy.

Generally the clinician makes a diagnosis of actinomycosis by identifying the colonies in the tissue from the lesion. Actinomycosis is treated with long-term high doses of antibiotics.

SYPHILIS

Syphilis is a disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. The organism is transmitted from one person to another by direct contact. The spirochete, a corkscrewlike organism, can penetrate mucous membranes but requires a break in the continuity of the skin surface to invade through the skin. The organisms die quickly when exposed to air and changes in temperature. Syphilis is usually transmitted through sexual contact with a partner who has active lesions. It can also be transmitted by transfusion of infected blood or by transplacental inoculation of a fetus from an infected mother.

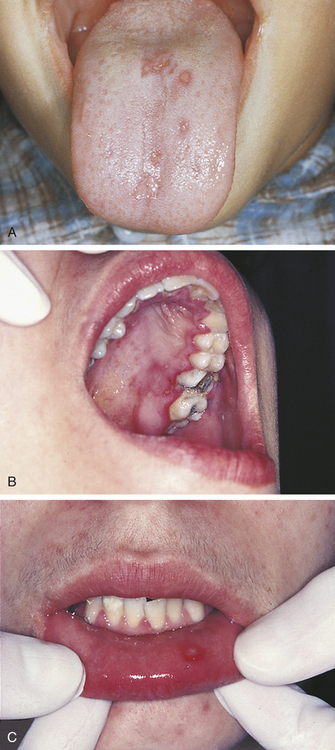

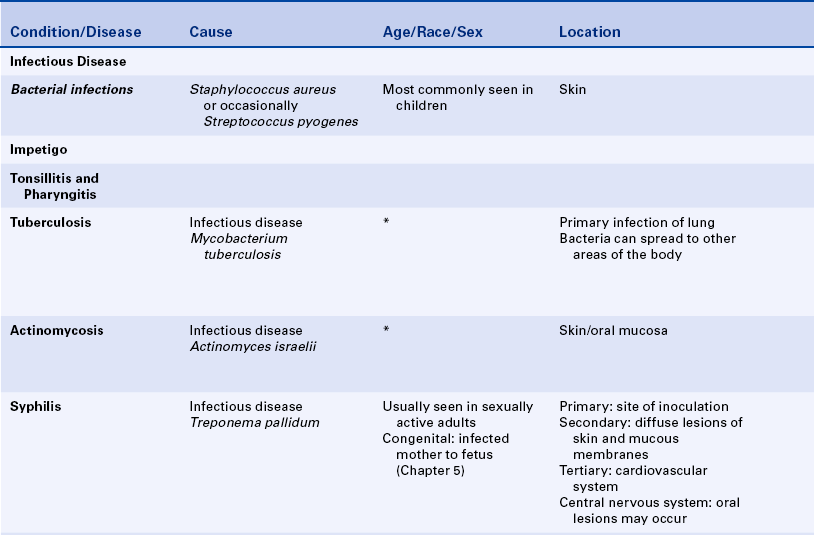

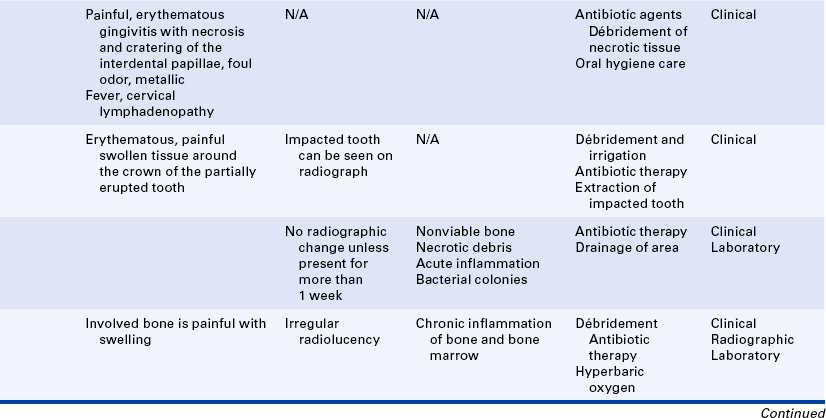

The disease occurs in three stages: (1) primary, (2) secondary, and (3) tertiary (Table 4-1). The lesion of the primary stage, called the chancre, is highly infectious and forms at the site at which the spirochete enters the body (Figure 4-3). Regional lymphadenopathy accompanies the chancre. The lesion heals spontaneously after several weeks without treatment, and the disease enters a latent period.

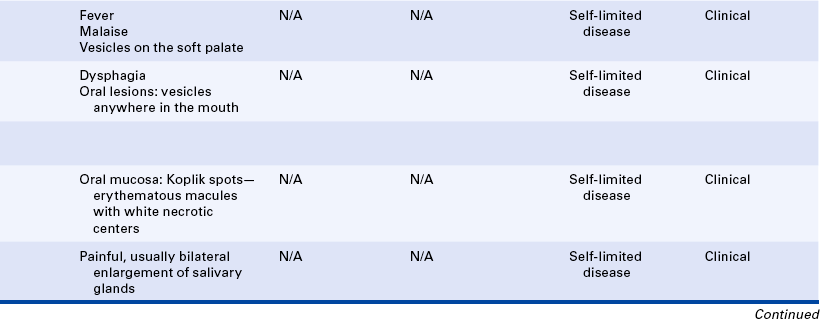

Table 4-1

| Stage | Oral Lesion |

| Primary | Chancre |

| Secondary | Mucous patch |

| Latent | None |

| Tertiary | Gumma |

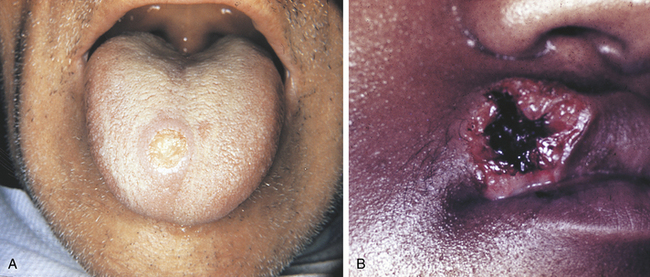

FIGURE 4-3 A, Chancre on tongue seen in primary syphilis. B, Chancre on lip. (A courtesy Dr. Norman Trieger; B courtesy Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli.)

The secondary stage occurs about 6 weeks after the primary lesion appears. In the secondary stage diffuse eruptions of the skin and mucous membranes occur. The skin lesions have many forms. The oral lesions are called mucous patches and appear as multiple, painless, grayish-white plaques covering ulcerated mucosa. The lesions of secondary syphilis are the most infectious. They undergo spontaneous remission but can recur for months or years. After remission the disease may remain latent for many years.

The tertiary lesions occur years after the initial infection if the infection has not been treated. They chiefly involve the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system. The localized tertiary lesion is called a gumma and is noninfectious. A gumma can occur in the oral cavity; the most common sites are the tongue and palate. The lesion appears as a firm mass that eventually becomes an ulcer. The gumma is a destructive lesion and can lead to perforation of the palatal bone.

Congenital Syphilis

Syphilis can be transmitted from an infected mother to the fetus because the organism can cross the placenta and enter the fetal circulation. Congenital syphilis often causes serious and irreversible damage to the child such as facial and dental abnormalities. The developmental disorders that result from fetal and neonatal syphilis are described in Chapter 5.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis of syphilitic lesions occurring on skin can be made using a special microscopic technique called a dark-field examination to identify the spirochetes. However, other spirochetes are present in the oral cavity; therefore this examination is not reliable for oral lesions. Two of the serologic (blood) tests that are commonly used to confirm the diagnosis of syphilis: (1) the Venereal Disease Research Laboratories (VDRL) test, and (2) the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test. These tests may produce negative results in primary syphilis because sufficient antibodies may not have formed for the test result to be positive.

Syphilis is generally treated with penicillin. The VDRL test is used again to evaluate the success of treatment. The antibody titer decreases if treatment has been successful.

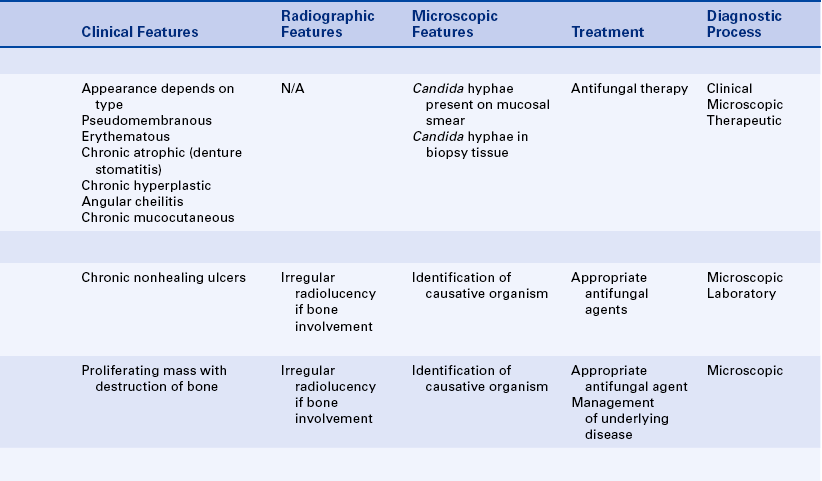

NECROTIZING ULCERATIVE GINGIVITIS

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) is also called acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG). It is a painful erythematous gingivitis with necrosis of the interdental papillae (Figure 4-4). NUG is usually caused by a combination of a fusiform bacillus and a spirochete (Borrelia vincentii) and is associated with decreased resistance to infection.

The gingiva is painful and erythematous, with necrosis of the interdental papillae generally accompanied by a foul odor and metallic taste. The necrosis results in cratering of the interdental papillae area. Sloughing of the necrotic tissue presents as a pseudomembrane over the tissues. Systemic manifestations of infection such as fever and cervical lymphadenopathy may be present. Clinical features distinguish NUG from acute marginal gingivitis and the gingival component of acute primary herpes simplex infection (see Figure 4-17, B).

PERICORONITIS

Pericoronitis is an inflammation of the mucosa around the crown of a partially erupted, impacted tooth. The soft tissue around the mandibular third molar is the most common location for pericoronitis. The inflammation is usually the result of infection by bacteria that are part of the normal oral microflora, which proliferate in the pocket between the soft tissue and the crown of the tooth. Compromised host defenses, ranging from minor illnesses to immunodeficiency, are associated with an increased risk of pericoronitis. Trauma from an opposing molar and impaction of food under the soft tissue flap (operculum) covering the distal portion of the third molar may also precipitate pericoronitis.

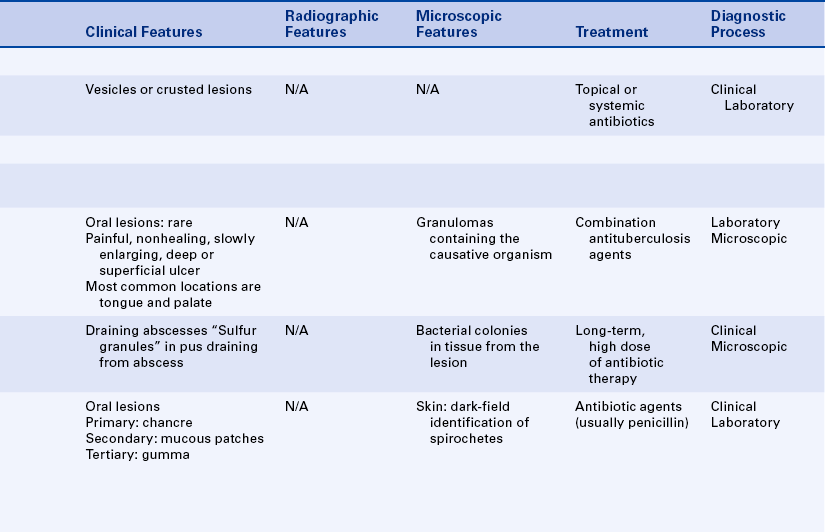

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS

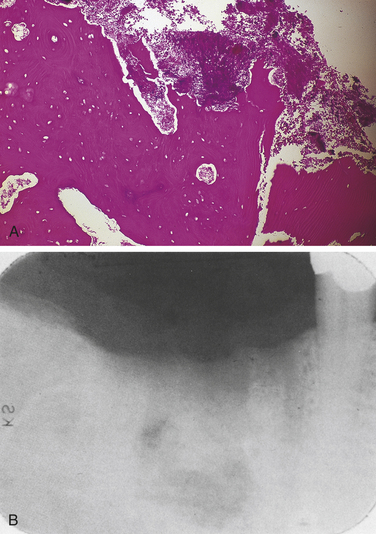

Acute osteomyelitis involves acute inflammation of the bone and bone marrow (Figure 4-5, A). Acute osteomyelitis of the jaws is most commonly a result of the extension of a periapical abscess. It may follow fracture of the bone or surgery and may also result from bacteremia.

FIGURE 4-5 A, Low-power microscopy of acute osteomyelitis showing nonviable bone. Bacterial colonies and inflammatory cells are seen between trabeculae of bone. B, Chronic osteomyelitis as seen radiographically.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of the specific organism causing acute osteomyelitis is based on culture results, and treatment is based on antibiotic sensitivity testing. Microscopic examination shows nonviable bone, necrotic debris, acute inflammation, and bacterial colonies in the marrow spaces. No change is seen on the radiograph unless the disease has been present for more than 1 week.

CHRONIC OSTEOMYELITIS

Chronic osteomyelitis is a long-standing inflammation of bone. It may occur in inadequately treated acute osteomyelitis, long-term inflammation of bone with no recognized acute phase, Paget disease, sickle cell disease, or bone irradiation that results in decreased vascularity. The involved bone is painful and swollen, and radiographic examination reveals a diffuse and irregular radiolucency that can eventually become radiopaque (Figure 4-5, B). When radiopacity develops, the condition is called chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis. Recently, cases of osteonecrosis of the mandible and maxilla have been reported in patients taking bisphosphonate medication. This may appear clinically similar to chronic osteomyelitis. Bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis is described in Chapter 9.

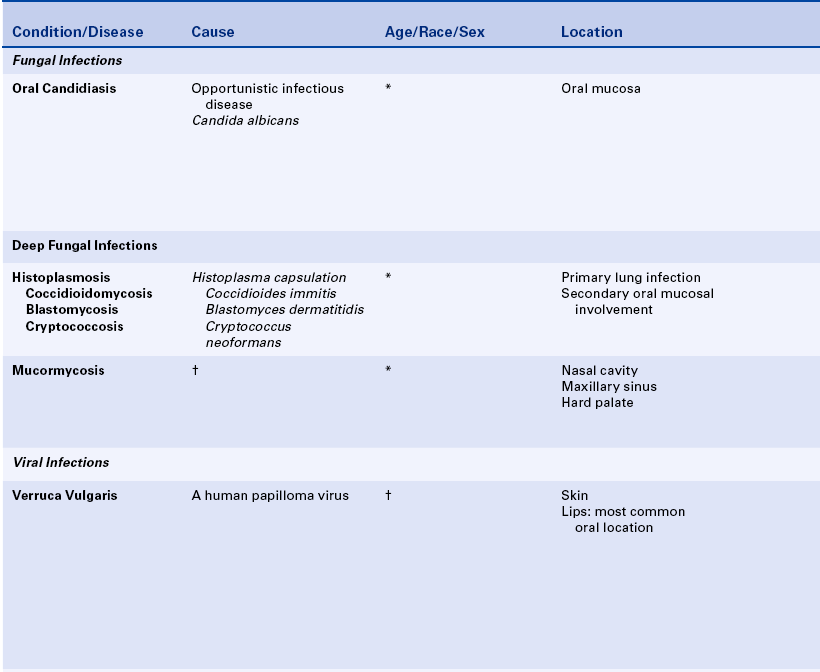

CANDIDIASIS

Candidiasis, also called moniliasis and thrush, occurs as a result of an overgrowth of the yeastlike fungus Candida albicans. It is the most common oral fungal infection. This fungus is part of the normal oral microflora in many individuals, particularly those who wear dentures. Overgrowth of Candida albicans is associated with many different conditions, including the following:

Newborn infants are particularly susceptible to an overgrowth of this fungus because they do not have either an established oral microflora or a fully developed immune system. Pregnant women often have Candida vaginitis, and the organism is transmitted to the infant while passing through the birth canal. Antibiotics can alter the bacteria of the oral microflora, which can allow the overgrowth of Candida albicans. Systemic and topical corticosteroids, diabetes, and cell-mediated immune system deficiency are other factors that allow the overgrowth of this fungus. Candidiasis is one of the most common oral lesions that occur in association with immunodeficiency. Candidiasis generally affects the superficial layers of the epithelium; therefore, when it is present, the proliferating organisms are easily identified in a sample obtained by scraping the surface (mucosal smear) of the lesion.

Types of Oral Candidiasis

Several forms of oral candidiasis exist; recognition of their clinical features is important so that candidiasis is included in the differential diagnosis of a variety of clinical presentations. The types of oral candidiasis are:

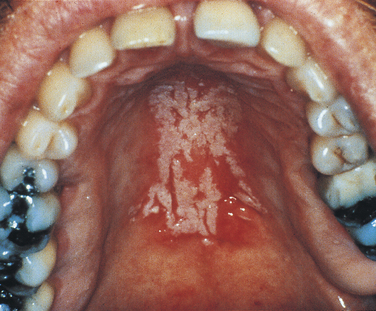

Pseudomembranous Candidiasis

A white curdlike material is present on the mucosal surface in pseudomembranous candidiasis (Figure 4-6). The underlying mucosa is erythematous. Occasionally a burning sensation is felt, and the patient may complain of a metallic taste.

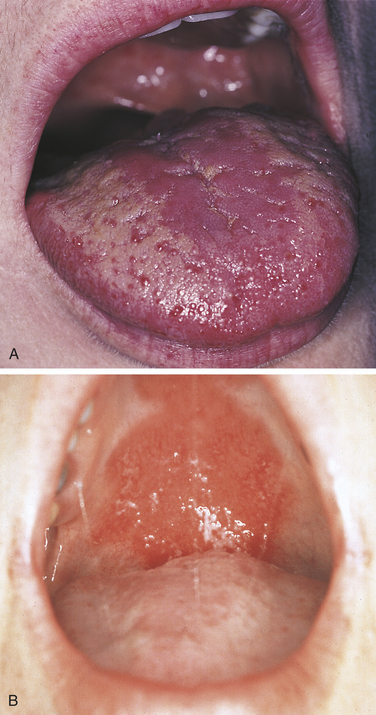

Erythematous Candidiasis

An erythematous, often painful, mucosa is the presenting complaint in erythematous candidiasis (Figure 4-7). This type of candidiasis may be localized to one area of the oral mucosa or be more generalized.

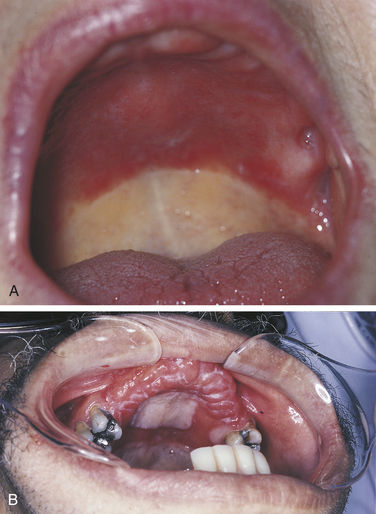

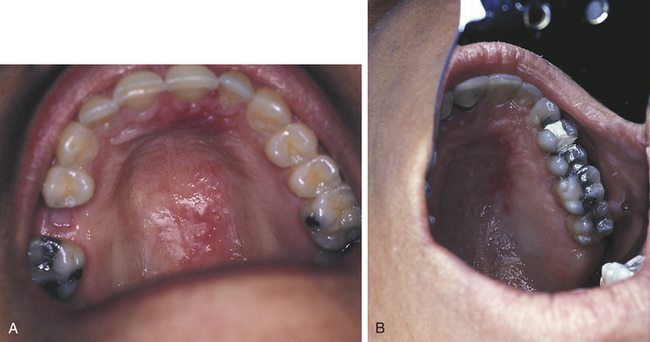

Denture Stomatitis

Denture stomatitis is the most common type of candidiasis affecting the oral mucosa. It is also called chronic atrophic candidiasis (Figure 4-8). This type of candidiasis also presents as erythematous mucosa, but the erythematous change is limited to the mucosa covered by a full or partial denture. The lesions may vary from petechiae-like to more generalized and granular. It is most common on the palate and maxillary alveolar ridge. Denture stomatitis is asymptomatic and is usually discovered by the dentist or dental hygienist during a routine oral examination.

Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (Figure 4-9) appears as a white lesion that does not wipe off the mucosa. Candidal leukoplakia and hypertrophic candidiasis are other names for this type of oral candidiasis. An important diagnostic feature of this type of candidiasis is its response to antifungal medication: when leukoplakia is caused by candidiasis, it disappears when treated with antifungal medication (therapeutic diagnosis). If the lesion does not respond to antifungal therapy, biopsy should be considered to establish the diagnosis of the lesion.

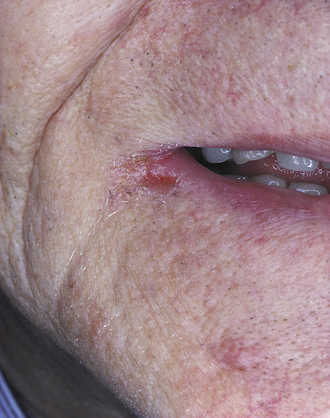

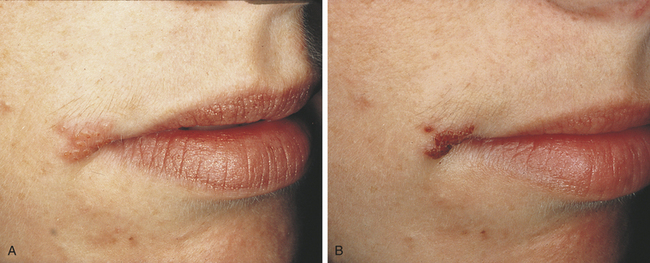

Angular Cheilitis

Candida organisms are often the cause of angular cheilitis (Figure 4-10). It appears as erythema or fissuring at the labial commissures. Angular cheilitis may be caused by other factors such as nutritional deficiency; however, it most commonly results from Candida infection. Angular cheilitis frequently accompanies intraoral candidiasis.

Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

A severe form of candidiasis that usually occurs in patients who are severely immunocompromised is called chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. The patient has chronic oral and genital mucosal candidiasis, skin as well as lesions. Oral involvement may appear as pseudomembranous, erythematous, or hyperplastic candidiasis; and angular cheilitis is common. The skin lesions usually involve the nails and skinfolds.

Median Rhomboid Glossitis

Several studies have reported an association between median rhomboid glossitis (Figure 4-11) and candidiasis. It appears as an erythematous, often rhombus-shaped, flat-to-raised area on the midline of the posterior dorsal tongue. Candida organisms have been identified in some lesions, and some lesions disappear with antifungal treatment. However, the response to antifungal treatment is not consistent; therefore, although this lesion has been associated with candidiasis, the cause is not yet clear.

Diagnosis and Treatment

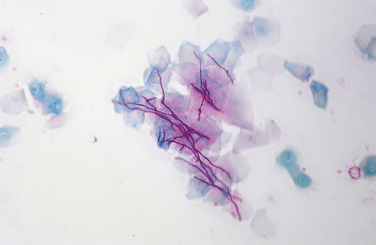

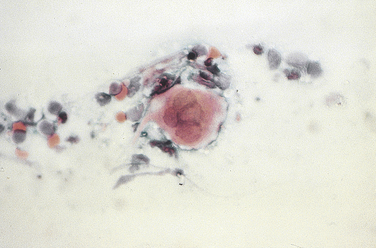

Because Candida is part of the oral microflora in many individuals, a culture is not useful for diagnosis. A positive culture result indicates that the organisms are present but not that they are causing infection. The use of the mucosal smear (Figure 4-12) is usually more helpful. The surface of the lesion is scraped vigorously with a tongue blade, wooden spatula, or specially designed brush; and the scrapings are spread on a glass slide and fixed with alcohol. The slide is then sent to an oral pathology laboratory for staining and examination. In addition to the smear, the response of the lesion to antifungal treatment is important in confirming the diagnosis of candidiasis. Lesions caused by Candida should resolve with antifungal treatment. Both topical and systemic medications are used for candidiasis. However, in some patients, particularly those who are immunocompromised, candidiasis is persistent and recurrent.

Although the final diagnosis and management of a patient with oral candidiasis is the responsibility of the dentist, dental hygienists are often the first to recognize the oral changes characteristic of this condition. Recurrent oral candidiasis may be an early sign of a severe underlying medical problem.

DEEP FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Oral lesions occur in some deep fungal infections (e.g., histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and cryptococcosis). They are all characterized by primary involvement of the lungs. Oral lesions are caused by implantation of the organism carried by sputum from the lungs to the oral mucosa.

Infections caused by these organisms are more common in certain areas of the United States than in others. Histoplasmosis is widespread in the midwestern United States, and coccidioidomycosis is more prevalent in parts of the western United States, particularly the San Joaquin Valley of California. Blastomycosis is common in the Ohio-Mississippi river basin area. Therefore oral lesions caused by these organisms are most likely seen in areas of the country in which the infection is most common.

Cryptococcosis is transmitted through inhalation of organisms contained in dust from bird droppings, particularly from pigeons. In addition to the regional distribution of these infections, reactivation, including the development of oral lesions, can also occur in patients who are immunocompromised.

Diagnosis

The initial signs and symptoms of these deep fungal infections are usually related to the primary lung infection. Oral lesions are preceded by pulmonary involvement. These oral lesions are chronic, nonhealing ulcers that can resemble squamous cell carcinoma. Diagnosis is made by biopsy and microscopic examination. Special staining of the tissue reveals the organisms, which can be identified by their microscopic appearance. The tissue can also be cultured; this is useful in establishing the diagnosis.

MUCORMYCOSIS

Mucormycosis, also called phycomycosis, is a rare fungal infection. The organism is a common inhabitant of soil and is usually nonpathogenic. However, infection with this organism occurs in diabetic and severely debilitated patients. The disease often involves the nasal cavity, maxillary sinus, and hard palate and can present as a proliferating or destructive mass in the maxilla. The diagnosis is made by biopsy and identification of the organisms in the tissue.

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS INFECTION

More than one hundred different types of the human papilloma virus (HPV) have been identified. Several have been identified in oral lesions, and some have been identified in normal oral mucosa. Human papilloma viruses have also been implicated in neoplasia.

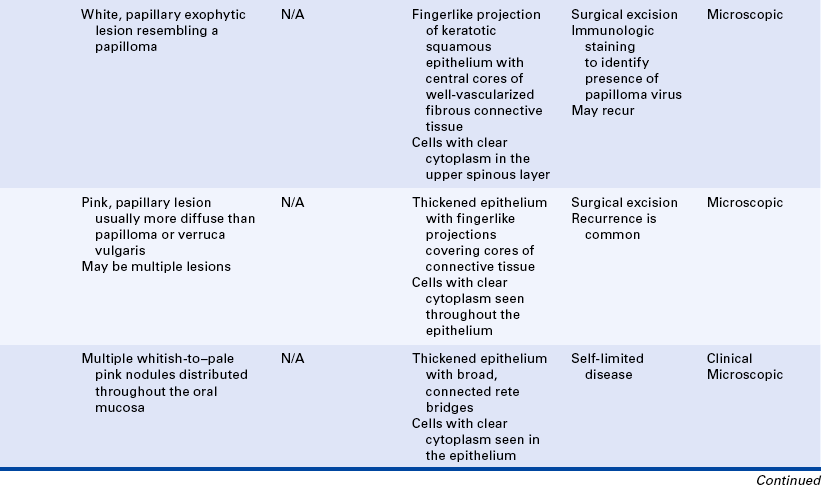

Verruca Vulgaris

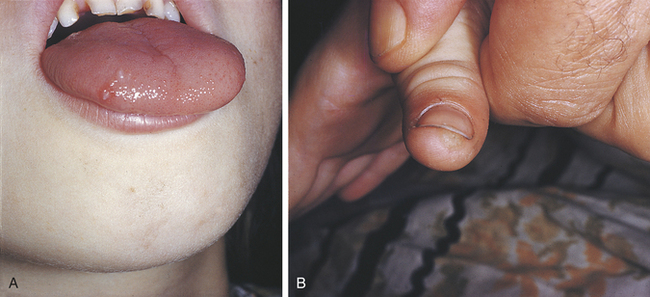

The verruca vulgaris, or common wart, is a papillary oral lesion caused by an human papilloma virus. It is a common skin lesion. Oral lesions are less common than skin lesions, but they do occur. The virus is inoculated by direct contact and may be transmitted from skin to oral mucosa. The lips are one of the most common intraoral sites for this lesion. Autoinoculation occurs through finger sucking or fingernail biting in patients with verrucae on the hands or fingers (Figure 4-13). The verruca vulgaris is usually a white, papillary, exophytic lesion (Figure 4-14) that closely resembles and is related to the benign tumor of squamous epithelium called the papilloma (see Chapter 7).

FIGURE 4-13 A and B, Verruca vulgaris on the tongue of a child with a similar lesion on the thumb. (Courtesy Dr. Edward V. Zegarelli.)

Histologically the verruca vulgaris consists of fingerlike projections of markedly keratotic, stratified squamous epithelium that exhibits a prominent granular cell layer; numerous cells with clear cytoplasm called koilocytes are present in the upper spinous layer of the epithelium. These cells contain the viral particles that are visible by electron microscopic examination. Each of the projections contains a central core of fibrous connective tissue containing many blood vessels. The vacuolated cells in the epithelium contain the viral particles.

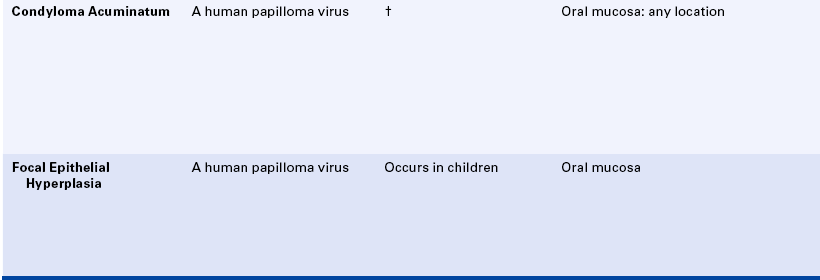

Condyloma Acuminatum

The condyloma acuminatum is a benign papillary lesion that is caused by another papilloma virus. The virus is generally transmitted by sexual contact and is most common in the anogenital region. It is transmitted to the oral cavity through oral-genital contact or self-inoculation.

Oral condylomas appear as papillary, bulbous masses and can occur anywhere in the oral mucosa (Figure 4-15). Multiple lesions may be present. They have been reported to occur on the tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, gingiva, and alveolar ridge. The oral condyloma tends to be more diffuse than the papilloma or verruca vulgaris and is generally not as well keratinized as the verruca vulgaris. The condyloma is pink, whereas the verruca vulgaris is usually white.

FIGURE 4-15 Condyloma acuminatum. The presence of condyloma acuminatum in a child is strongly suggestive of sexual abuse. (Courtesy Dr. Sidney Eisig.)

Histologically the condyloma acuminatum is composed of fingerlike (papillary) projections of epithelium covering cores of connective tissue. The epithelium is thickened, and cells with clear cytoplasm are seen throughout the epithelium. These clear cells contain viral particles that can be identified through immunologic staining.

When the condyloma acuminatum occurs in the oral cavity, it is generally treated by conservative surgical excision. However, recurrence is common, and multiple lesions make management difficult. Patients should be instructed to avoid oral-genital contact with an infected partner to prevent reinoculation.

Focal Epithelial Hyperplasia

Focal epithelial hyperplasia, also called Heck disease, is characterized by the presence of multiple whitish-to–pale pink nodules distributed throughout the oral mucosa (Figure 4-16). The disease is most common in children and was first described in Native Americans, but it has since been described in many different areas of the world. This disease is caused by another human papilloma virus. The lesions are generally asymptomatic and do not require treatment. They resolve spontaneously within a few weeks. Histologically the lesions show thickened epithelium with broad, connected rete ridges. Cells in the epithelium have clear cytoplasm, which is a common finding in lesions caused by a human papilloma virus.

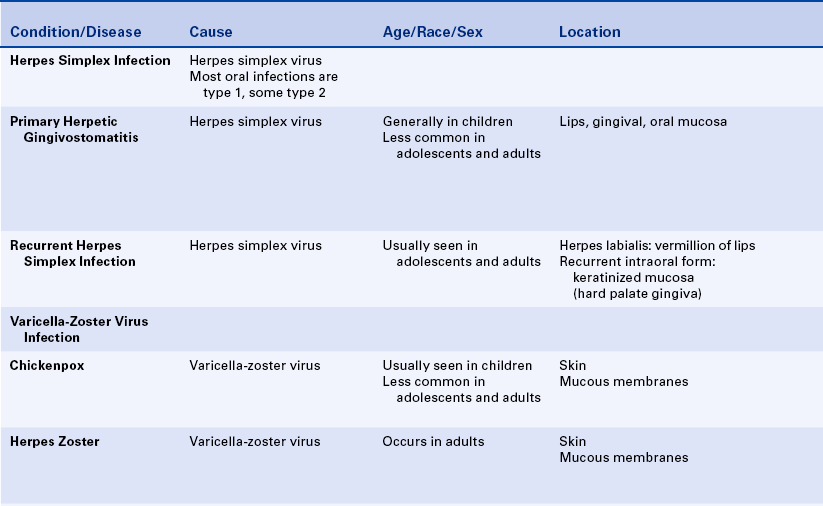

HERPES SIMPLEX INFECTION

Two major forms of the herpes simplex virus exist: (1) type 1 and (2) type 2. Oral infections are generally caused by type 1, and genital infections are most commonly caused by type 2. Oral infection with the herpes simplex virus occurs in an initial (primary) form and a recurrent (secondary) form. The herpes simplex virus is one of a group of viruses called human herpes viruses (HHVs). Other herpes viruses include varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV human herpes virus 8). Herpes simplex viruses have the ability to persist in an individual in a clinically quiescent or latent state. The primary infection undergoes remission without the virus being completely eliminated.

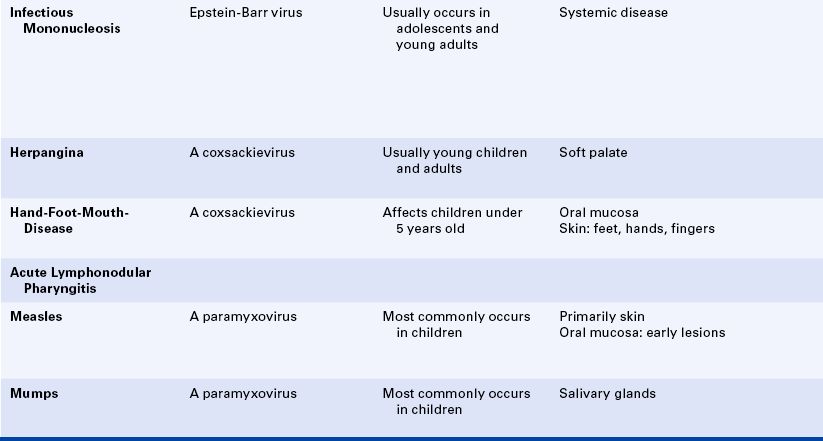

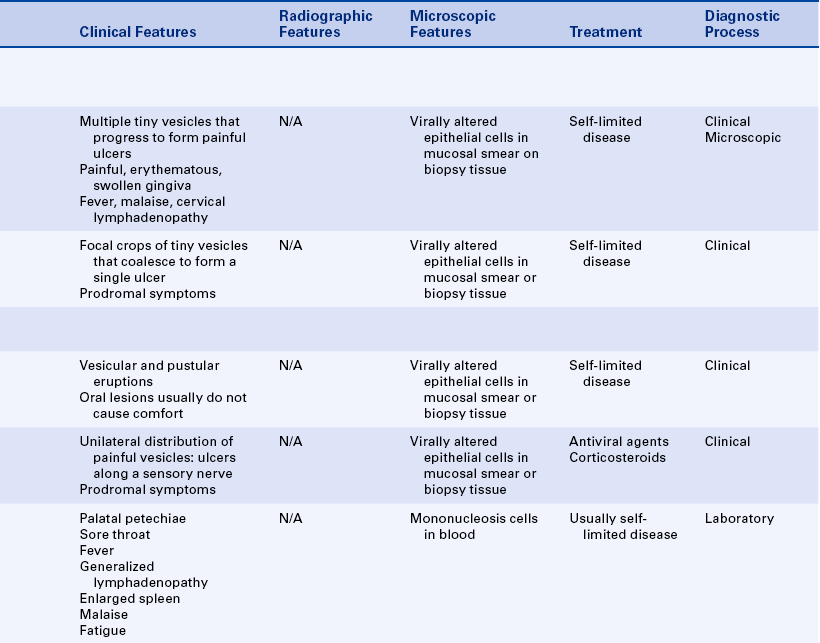

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

The oral disease caused by initial infection with the herpes simplex virus is called primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (Figure 4-17). Painful, erythematous, and swollen gingiva and multiple tiny vesicles on the perioral skin, vermilion border of the lips, and oral mucosa characterize the disease. These vesicles progress to form ulcers. Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, and cervical lymphadenopathy generally occur first, followed by gingival involvement and the appearance of mucosal vesicles and ulcers. The disease most commonly occurs in children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years. However, it may occur at any age if an individual who has not been previously exposed to the virus comes into contact with it or if a sufficient level of antibodies has not developed to confer protection against reinfection. Because many more individuals have antibodies to herpes simplex than have a history of the disease, the majority of infections are thought to be subclinical. The disease is usually self-limited. The lesions heal spontaneously in 1 to 2 weeks.

Recurrent Herpes Simplex Infection

The herpes simplex virus tends to persist in a latent state, usually in the nerve tissue of the trigeminal ganglion, and causes localized recurrent infections. It has been estimated that one third to one half of the population of the United States experience recurrent herpes simplex infection. The most common type of recurrent oral herpes simplex infection occurs on the vermilion border of the lips and is called herpes labialis (Figure 4-18), which is also called a cold sore or fever blister. Recurrent infections are often produced by certain stimuli such as sunlight, menstruation, fatigue, fever, and emotional stress. These stimuli are thought to trigger the viral replication and immunologic changes that result in clinical lesions.

Recurrent herpes simplex infection can also occur intraorally (Figure 4-19). The appearance and location of these lesions are important to distinguish them from aphthous ulcers (Table 4-2). Recurrent intraoral herpes simplex occurs on keratinized mucosa that is fixed to bone, most commonly the hard palate and gingiva. The lesions appear as painful clusters of tiny vesicles or ulcers that can coalesce to form a single ulcer with an irregular border. Usually patients experience prodromal symptoms such as pain, burning, or tingling in the area in which the vesicles develop. The lesions heal without scarring in 1 to 2 weeks. Episodes of recurrence vary from once a month in some individuals to once a year in others.

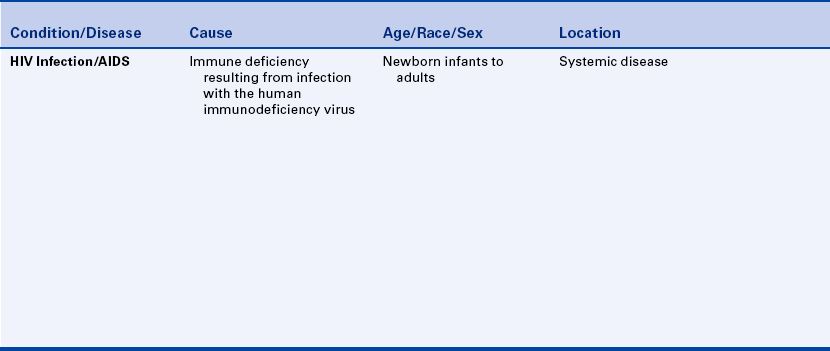

Table 4-2

Comparison of the clinical features of recurrent minor aphthous ulcers and recurrent herpes ulceration

| Feature | Minor Aphthous Ulcers | Herpes Simplex Ulceration |

| Location | Nonkeratinized mucosa | Keratinized mucosa |

| Number | One to several | Multiple (crops) |

| Vesicle precedes ulcer | No | Yes |

| Pain | Yes | Yes |

| Size | <1 cm | 1-2 mm |

| Borders | Round to oval | Crops of ulcers coalesce to form a large irregular ulcer |

| Recurrent | Yes | Yes |

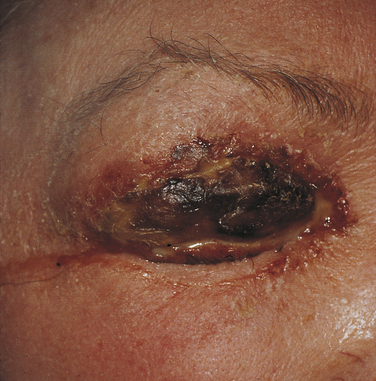

Herpes simplex virus is transmitted by direct contact with an infected individual, and the lesions of the primary infection occur at the site of inoculation. The herpes simplex virus can be isolated from both primary and recurrent lesions. The amount of virus present is highest in the vesicle stage. In some individuals the virus is present in the oral cavity, even when no lesions are present. Herpes simplex virus can cause a painful infection of the fingers called herpetic whitlow in dentists and dental hygienists (Figure 4-20). Herpetic whitlow can be either a primary or a recurrent infection. Herpes simplex can also cause eye infection (Figure 4-21). Routine barrier infection control procedures (mask, eye protection, and gloves) are important in preventing the transmission of the herpes simplex virus to dental health care providers.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of herpes simplex infection, both primary and recurrent, is generally based on the clinical characteristics of the disease (see Table 4-2). In immunocompromised patients the characteristic clinical features may be lacking. A viral culture can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. This procedure requires a special culture medium and at least 2 days before results are available.

Herpes simplex virus causes changes in epithelial cells that can be seen microscopically. These virally altered cells can be seen in tissue obtained by biopsy or on a smear taken by scraping the basal cells of the lesion and spreading them on a glass slide, fixing them with alcohol, and submitting them to a pathology laboratory for staining and examination (Figure 4-22). Smears of herpes simplex ulceration have been reported to be positive for virally altered cells only about 50% of the time.

Treatment

Antiviral drugs such as acyclovir are available for the treatment of herpes simplex infection and are used for treating genital herpes simplex infection. Antiviral drugs have not been shown to be consistently effective in treating the intraoral lesions of herpes simplex infection except in immunocompromised patients. The use of sunscreens may prevent the development of herpes labialis. Systemic antiviral medication has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating and preventing herpes labialis. Topical application of antiviral drugs may prevent or decrease the duration of herpes labialis when they are administered very early in the development of the lesion (prodrome) before epithelial damage has occurred.

VARICELLA-ZOSTER VIRUS

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes both chickenpox (varicella) and shingles (herpes zoster). Respiratory aerosols and contact with secretions from skin lesions transmit the virus. Both chickenpox and herpes zoster are contagious.

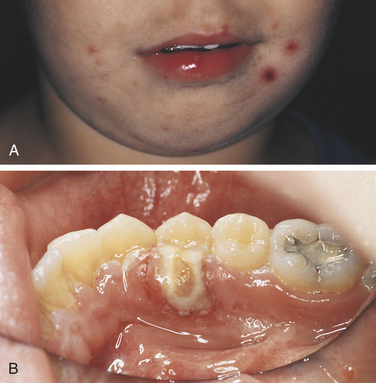

Chickenpox

Chickenpox is a highly contagious disease that causes vesicular and pustular eruptions of the skin and mucous membranes, along with systemic symptoms such as headache, fever, and malaise (Figure 4-23). The incubation period is about 2 weeks. Chickenpox usually occurs in children; although oral lesions occur, they generally do not cause severe discomfort. Usually an individual has only a single episode of chickenpox; but second, milder forms have also been described. Recovery generally occurs in 2 to 3 weeks.

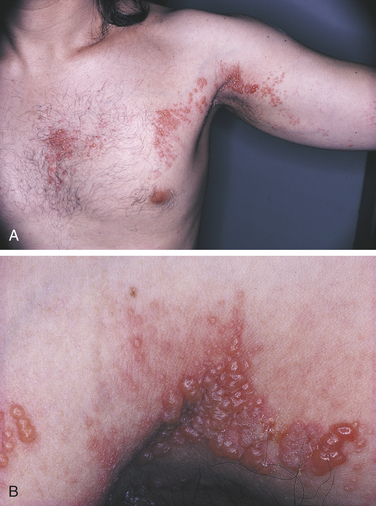

Herpes Zoster

Although chickenpox has been described in adults, the virus usually causes a different form of disease in this population. The form that usually occurs in adults is called herpes zoster or shingles. It is characterized by a unilateral, painful eruption of vesicles along the distribution of a sensory nerve (Figure 4-24). Whether or not the varicella-zoster virus is harbored in the sensory ganglia (during the interval between chickenpox and herpes zoster) in a manner similar to that of the herpes simplex virus is not clear. However, herpes zoster often occurs in association with immunodeficiency or certain malignancies such as Hodgkin disease and leukemia. A vaccine is available to prevent varicella-zoster infections. The vaccine is given to children to prevent chickenpox and to older adults to prevent the recurrence of the infection as herpes zoster.

FIGURE 4-24 Herpes zoster. A, Unilateral distribution of vesicles along the distribution of a sensory nerve. B, Many vesicles coalesce to form large lesions.

The depression of cell-mediated immunity (CMI) appears to be important in the development of herpes zoster. Any of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve may be affected: (1) the ophthalmic branch, (2) the maxillary branch, or (3) the mandibular branch (Figure 4-25). Oral lesions occur when the maxillary or mandibular branches are affected (Figure 4-26). The oral lesions, like the skin lesions, are characterized by their unilateral distribution. Prodromal symptoms of pain, burning, or paresthesia often precede the development of vesicles. Oral lesions are painful and begin as vesicles that progress to ulcers. The disease usually lasts for several weeks, and in some patients, neuralgia, which takes months to resolve, may follow the resolution of the lesions.

FIGURE 4-26 Herpes zoster. A, Unilateral facial lesions occurring along the distribution of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve. B, Intraoral lesions in the same patient illustrate the unilateral distribution of herpes zoster.

EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS INFECTION

The Epstein-Barr virus has been implicated in several diseases that occur in the oral region, including infectious mononucleosis, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and hairy leukoplakia. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma and Burkitt lymphoma are rare malignant neoplasms. Infectious mononucleosis and hairy leukoplakia are discussed here.

Infectious Mononucleosis

Infectious mononucleosis is an infectious disease caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). It is characterized by sore throat, fever, generalized lymphadenopathy, enlarged spleen, malaise, and fatigue. Palatal petechiae occur in infectious mononucleosis, usually appearing early in the course of the disease. The mechanism for the development of these petechiae is unclear. The diagnosis is confirmed by the identification in the blood of mononucleosis cells, which are atypical activated T lymphocytes. Severe complications such as hepatitis occur in some patients. In developed countries infectious mononucleosis occurs principally in late adolescence and young adults in upper socioeconomic classes. The virus is transmitted by close contact. Contact with saliva during kissing is a frequent route of transmission of Epstein-Barr virus. In most patients infectious mononucleosis is a benign, self-limited disease that resolves within 4 to 6 weeks. In some patients fatigue lasts much longer.

Hairy Leukoplakia

This irregular, corrugated white lesion most commonly occurs on the lateral border of the tongue (Figure 4-27). Epstein-Barr virus has been identified in the epithelial cells of hairy leukoplakia and is considered to be the cause of the lesion. Hairy leukoplakia was first identified in patients infected with HIV and occurs most commonly in these patients; it has also been reported in immunocompromized patients not infected with HIV.

COXSACKIEVIRUS INFECTIONS

The coxsackieviruses, named for the town in New York where the virus was first discovered, cause several different infectious diseases. Three of these have distinctive oral lesions and are discussed here. Fecal-oral contamination, saliva, and respiratory droplets can be the means of transmission.

Herpangina

Herpangina characteristically includes vesicles on the soft palate (Figure 4-28), along with fever, malaise, sore throat, and difficulty swallowing (dysphagia). An erythematous pharyngitis is also present. The disease is usually mild to moderate and resolves in less than 1 week without treatment.

Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease usually occurs in epidemics in children younger than 5 years of age. Oral lesions are generally painful vesicles and ulcers that can occur anywhere in the mouth. Multiple macules or papules occur on the skin, typically on the feet, toes, hands, and fingers. Lesions resolve spontaneously within 2 weeks.

Diagnosis

Although the oral lesions may resemble herpes simplex infection, the distribution of the skin lesions and the mild systemic symptoms usually help to differentiate the two conditions. Viral culture and measurement of circulating antibodies to the type of coxsackievirus that causes hand-foot-and-mouth disease may help to confirm the diagnosis but generally are not necessary.

Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Acute lymphonodular pharyngitis is another coxsackievirus infection that is characterized by fever, sore throat, and mild headache. Hyperplastic lymphoid tissue of the soft palate or tonsillar pillars appears as yellowish or dark pink nodules. The disease generally lasts several days to 2 weeks and does not usually require treatment.

OTHER VIRAL INFECTIONS THAT MAY HAVE ORAL MANIFESTATIONS

Measles is a highly contagious disease causing systemic symptoms and a skin rash that results from a type of virus called a paramyxovirus. The disease most commonly occurs in childhood. Early in the disease, Koplik spots, which are small erythematous macules with white necrotic centers, may occur in the oral cavity.

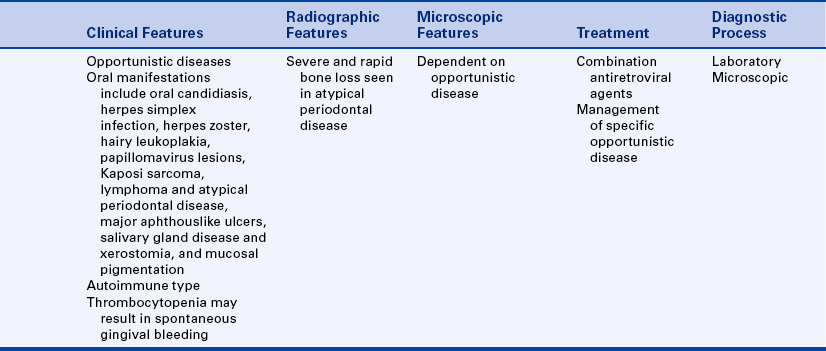

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS AND ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME

The virus associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was identified in 1983; in 1986 it was designated as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The HIV virus is transmitted by sexual contact with infected persons, by contact with infected blood and blood products, and to infants of infected mothers. HIV infects cells of the immune system. The most important of the cells of the immune system that the virus infects is the CD4 T-helper lymphocyte. This lymphocyte is important both in CMI and in regulating the immune response. As the disease progresses, this lymphocyte becomes depleted. Other cells that may be infected with HIV include macrophages, Langerhans cells, dendritic cells, and cells of the nervous system.

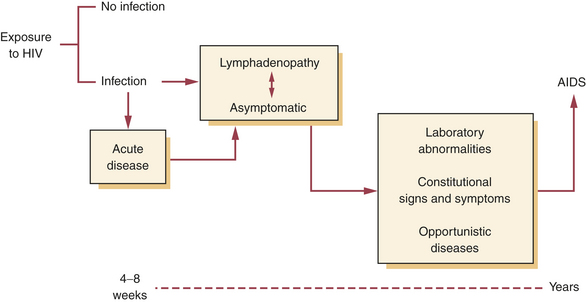

THE SPECTRUM OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

Many individuals experience an acute disease that occurs shortly after infection with HIV, whereas other individuals remain asymptomatic. The acute disease resolves, and infected individuals may have no signs or symptoms of disease for some time. In most patients infected with HIV, a progressive immunodeficiency eventually develops. As the immune system begins to fail, the number of CD4 lymphocytes decreases; nonspecific problems such as fatigue and opportunistic infections such as oral candidiasis may develop. As the immune system becomes profoundly deficient, life-threatening opportunistic infections and cancers occur. The most severe result of infection with HIV is AIDS.

DIAGNOSING AIDS

The diagnosis of AIDS is well defined. The definition of AIDS has been established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is given in Box 4-1. Since it was identified in the early 1980s, this definition has been changed several times as knowledge of the disease has grown. The most recent definition of AIDS in adults and adolescents includes HIV infection with severe CD4 lymphocyte depletion (less than 200 CD4 lymphocytes per microliter [μl] of blood). The normal CD4 lymphocyte count is between about 550 and 1000 lymphocytes/μl blood. The revised definition continues to include a number of opportunistic diseases such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, esophageal candidiasis, and Kaposi sarcoma. Also included is HIV-related wasting syndrome. In addition to including the CD4 lymphocyte count, the revised definition includes pulmonary tuberculosis, recurrent pneumonia, and invasive cervical cancer.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS TESTING

Tests that identify antibody to HIV are the tests generally used to determine if a person has been infected with HIV. Recently a rapid HIV test has been approved. This test identifies antibody to HIV either in oral fluid or in blood. The oral test uses a collector specially designed to obtain a sample of transudate through the oral mucosa. A positive oral test is confirmed by a blood test. A negative test does not require confirmation. Routine HIV testing generally uses a blood test that is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). When this test is positive twice, it is followed by a more specific test called the Western blot test. To be considered seropositive for HIV, a person must have two positive ELISA test results followed by a positive Western blot test result. Other tests such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identify virus rather than antibody. In the United States different states have different laws concerning HIV testing. Informed consent by the patient and pretest counseling may be required before HIV testing can be done.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

As mentioned, the initial infection with HIV may be completely asymptomatic. However, early in HIV infection the amount of circulating virus is very high, and the risk of transmission to others may be very high. In some individuals lymphadenopathy may develop; in still others an acute illness resembling infectious mononucleosis and lasting 8 to 14 days can occur. When this acute illness develops, the patient may have sore throat, general malaise, myalgia, and arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, and fever. Patients with acute infection can also have a skin rash, nausea, and diarrhea. After this acute illness, some individuals have persistent lymphadenopathy, but many become completely asymptomatic.

The virus infects cells of the immune system; as a result this system stops protecting the individual against certain infections and tumors. In time, as the immune system becomes deficient, a variety of signs and symptoms can develop, signaling changes in the immune system. Several of these signs and symptoms occurring together are sometimes called AIDS-related complex. They include oral candidiasis, fatigue, weight loss, and lymphadenopathy. HIV can also infect cells of the nervous system, resulting in dementia in some patients.

Antibodies to HIV generally begin to be detectable in blood about 6 weeks after the initial infection. However, in some individuals antibodies may not be detectable for 6 months and occasionally for up to 1 year or more.

The spectrum of HIV infection includes the full range of problems that result from infection with this virus from asymptomatic infection to AIDS (Figure 4-29). AIDS represents terminal HIV infection in this spectrum. It is not yet known how many of the persons who become infected with HIV go on to experience immunodeficiency, opportunistic diseases, or dementia. Some patients who are HIV-seropositive appear to remain immunocompetent for many years. Cofactors that can contribute to the development of the immunodeficiency are being studied. Each year the results of natural history studies show an increase in the percentage of HIV-infected individuals in whom AIDS develops.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Tests such as PCR are used to measure the amount of HIV circulating in serum. This is called viral load. Measurement of viral load along with the CD4 lymphocyte count is used to assess HIV infection. Patients with HIV infection are managed with combinations of different types of antiretroviral (anti-HIV) drugs and drugs that prevent and treat opportunistic diseases. The combination of drugs is called highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART or ART). Measurement of viral load is used to evaluate the effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy. Management of HIV infection is continually changing in response to the results of ongoing clinical drug trials.

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS

Oral lesions are prominent features of AIDS and HIV infection (Box 4-2). Some of these lesions are known to be indicators of developing immunodeficiency and predictors of the development of AIDS in individuals who are HIV seropositive. The oral lesions that occur develop because of the deficiency in cell mediated immunity and the deregulation of immunologic responses that occurs when the T-helper cells (CD4+ lymphocytes) become depleted. Oral lesions include opportunistic infections, tumors, and autoimmune-like diseases. As a result of management of HIV infection with antiviral therapy, oral manifestations of HIV are much less common than earlier in the history of this disease.

Oral Candidiasis

This oral lesion occurs frequently in individuals with cell-mediated immunodeficiency and is one of the most common oral lesions seen in persons with HIV infection (Figure 4-30). It is also called thrush. All of the different types of oral candidiasis described earlier in this chapter, including mucocutaneous candidiasis, can occur. It is important to remember that candidiasis can be associated with a variety of conditions other than HIV infection, such as uncontrolled diabetes, other immunodeficiency diseases, antibiotic treatment, and xerostomia. Both topical and systemic antifungal treatment can be used to control oral candidiasis in the patient with immunodeficiency caused by HIV infection. Recurrence is common.

FIGURE 4-30 Candidiasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Removable white plaques are present on the mucosa of the soft palate.

In persons who are known to be infected with HIV, the development of oral candidiasis is worrisome because it generally signals the beginning of a progressively severe immunodeficiency. Persons with unexplained oral candidiasis should be referred to a physician for evaluation if the cause of the candidiasis cannot be determined. Studies have shown oral candidiasis to be a very early sign of developing immunodeficiency and predictive of the development of AIDS in a person who is infected with HIV. Oral lesions caused by other fungal infections such as histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis have also been reported in persons with HIV infection, but they are rare.

Herpes Simplex Infection

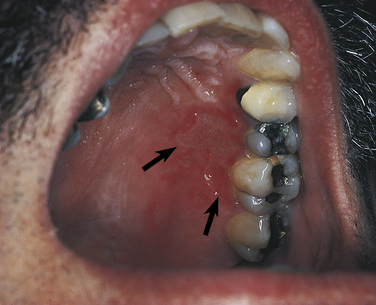

Ulcers caused by the herpes simplex virus occur in persons with HIV infection (Figure 4-31). Herpes labialis and lesions consistent with intraoral recurrent herpes simplex infection can also develop in persons with HIV infection. The clinical characteristics of these lesions are the same as those occurring in immunocompetent individuals. However, when the immune system, particularly cell mediated immunity, becomes deficient, HIV-infected individuals are at risk for the development of ulcers caused by the herpes simplex virus that do not have the same clinical characteristics as those seen in immunocompetent persons. These appear as persistent, superficial, painful ulcers that can be located anywhere in the oral cavity. Small, characteristic herpes simplex–like ulcers can be seen surrounding larger ulcers, but their presence cannot be depended on for diagnosis. The diagnosis of these ulcers is made by several methods, including viral culture, cytologic smear, biopsy, and response to the antiviral medication acyclovir.

FIGURE 4-31 Herpes simplex ulceration of the hard palate in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arrows point to the periphery of the ulcer.

Ulceration of the oral mucosa from herpes simplex infection that has been present for more than 1 month is an oral lesion that meets the criteria for the diagnosis of AIDS. This can occur only when a person has profound immunodeficiency. Oral ulcers caused by cytomegalovirus may also occur in HIV-infected individuals who are severely immunodeficient. These ulcers are much rarer than those caused by herpes simplex virus.

Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is caused by the varicella-zoster virus and is described earlier in this chapter. When herpes zoster occurs in a person with HIV infection, it generally follows the usual pattern (see Figures 4-24 to 4-26). Although the infection can disseminate, most cases are self-limited. In the facial and oral area the lesions appear as distinctly unilateral ones following the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve. The development of herpes zoster in a person infected with HIV is a sign of developing immunodeficiency.

Hairy Leukoplakia

Hairy leukoplakia is caused by Epstein-Barr virus and was discussed earlier in this chapter. It was first described in individuals with HIV infection; although it has been reported in HIV-negative individuals, most cases are an oral manifestation of HIV infection. It almost always occurs on the lateral borders of the tongue and may extend onto the dorsal and ventral tongue (see Figure 4-27; Figure 4-32). On the lateral tongue it appears as an irregular white lesion that has a corrugated surface. The corrugations may not be present when the lesions extend onto the dorsal or ventral tongue. Histologically this lesion shows hyperkeratosis (often with hairlike projections), epithelial hyperplasia, vacuolated epithelial cells, and little or no inflammatory infiltrate in the underlying connective tissue.

Other white lesions such as those resulting from chronic tongue chewing and hyperplastic candidiasis can resemble hairy leukoplakia clinically. Biopsy of the lesions can reveal a histologic appearance that is consistent with hairy leukoplakia. However, the most reliable method of diagnosis is identification of the Epstein-Barr virus in the lesion.

Generally hairy leukoplakia is not treated. Lesions may respond to antiviral medication such as acyclovir or zidovudine but recur when treatment is discontinued. Studies have shown hairy leukoplakia to be predictive of the development of AIDS in HIV-infected persons.

Papilloma Virus Infections

Lesions caused by papilloma viruses are described earlier in this chapter. Papillary oral lesions resulting from several different papilloma viruses have been described in persons with HIV infection. They have either normal color or slightly erythematous mucosa (Figure 4-33). These lesions may be persistent and may occur in multiple oral mucosal locations. Results of studies have suggested that the prevalence of these human papilloma virus lesions has not decreased with antiretroviral therapy as has the prevalence of most other HIV-associated oral lesions. Diagnosis of these lesions is made by biopsy and histologic examination, with special tests to identify papillomavirus.

Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is one of the opportunistic neoplasms that occur in patients with HIV infection. A herpes virus called human herpes virus (HHV-8) or kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV) has been associated with this neoplasm. Oral lesions appear as reddish-purple, flat or raised lesions and are seen anywhere in the oral cavity. The most common locations are the palate and gingiva (Figure 4-34).

FIGURE 4-34 Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A, Skin. B, Gingiva. (Courtesy Dr. Fariba Younai.)

The diagnosis is made by biopsy. However, the clinical appearance of the lesion can be used when it is characteristic and the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma has been made at another site. At present no effective treatment for Kaposi sarcoma exists. Surgical excision to decrease the size of the lesion is sometimes attempted, as are radiation treatment and chemotherapy. Kaposi sarcoma is one of the intraoral lesions that may fulfill the criteria for the diagnosis of AIDS.

Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is another of the malignant tumors that occur in association with HIV infection. It occasionally occurs in the oral cavity. Epstein-Barr virus has been associated with this neoplasm. These tumors have appeared as nonulcerated, necrotic, or ulcerated masses and have been surfaced by either ulcerated or normal-colored erythematous mucosa (Figure 4-35).

The diagnosis is made by biopsy and histologic examination. Treatment involves several different chemotherapeutic drugs. Oral lymphoma is another oral lesion that may meet the criteria for the diagnosis of AIDS.

Gingival and Periodontal Disease

In patients with HIV infection unusual forms of gingival and periodontal disease can develop. These occur in HIV-infected individuals whose immune system has become deficient. These have been called linear gingival erythema (LGE) and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP). A condition resembling necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) also occurs in individuals with HIV infection.

Linear gingival erythema has three characteristic features: (1) spontaneous bleeding, (2) punctate or petechiae-like lesions on the attached gingiva and alveolar mucosa, and (3) a bandlike erythema of the gingiva that does not respond to therapy. Linear gingival erythema is different from typical gingivitis in that gingivitis is generally not characterized by spontaneous bleeding and the erythema of typical gingivitis responds within a few days to 1 week to scaling, root planing, and improvement of oral hygiene. Linear gingival erythema occurs independently of oral hygiene status.

Some patients experience gingivitis that resembles necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, and it can be either generalized or localized to specific areas. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis resembles necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis in that patients experience pain, spontaneous gingival bleeding, interproximal necrosis, and interproximal cratering (Figure 4-36). Patients also experience intense erythema and, most characteristically, extremely rapid bone loss. Necrotizing stomatitis is characterized by extensive focal areas of bone loss along with the features of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis.

FIGURE 4-36 A and B, Atypical periodontal disease in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

The specific causes of these atypical gingival and periodontal diseases remain unclear. The microbiota associated with these diseases is being studied and have not been found to be distinctly different from those of inflammatory periodontal disease. These atypical gingival and periodontal conditions are not common in HIV-infected individuals and appear to occur in patients whose immune systems have become severely compromised.

Treatment of HIV gingivitis and periodontitis involves scaling, root planing, and soft tissue curettage. In addition, intrasulcular lavage with povidone-iodine, use of chlorhexidine mouth rinse, and short-term systemic metronidazole administration have been helpful in the treatment of these conditions. Good oral hygiene, including the use of smaller toothbrushes and interproximal cleaning devices, has been a component of management.

Most HIV-infected patients do not have HIV-associated gingival and periodontal problems. However, recognition of early lesions is essential to prevent extensive bone loss, and frequent recall is helpful in early identification of gingival and periodontal disease. Lack of response to periodontal treatment is a clue to the recognition of HIV-associated gingivitis and periodontitis.

Spontaneous Gingival Bleeding

A decrease in the number of platelets resulting from an autoimmune type of thrombocytopenic purpura is occasionally seen in patients with HIV infection. These patients can have bleeding gums or mucosal petechiae. Gingival bleeding not related to thrombocytopenia has also been described in linear gingival erythema and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. A platelet count and bleeding time should be considered before deep scaling procedures are performed.

Aphthous Ulcers

Characteristic minor aphthous ulcers occur in patients with HIV infection and AIDS. Studies have suggested that an increase in the incidence of these ulcers occurs in patients with HIV infection. The clinical appearance and behavior of minor aphthous ulcers in HIV-infected patients is the same as in other individuals (see Chapter 3). Minor aphthous ulcers are diagnosed on the basis of their clinical appearance.

Ulcers that resemble major aphthous ulcers also occur in patients with HIV infection (Figure 4-37). They appear as deep, persistent, painful ulcers and must be differentiated from infectious ulcers. Biopsy and histologic examination of these ulcers does not show any evidence of an infectious cause. These ulcers respond to topical and systemic corticosteroid therapy. Topical application of tetracycline and thalidomide has also been used in the management of these ulcers. Similar ulcers have been reported in the esophagus of patients with HIV infection.

Salivary Gland Disease

Bilateral parotid gland enlargement has been reported to occur in patients who are HIV positive (Figure 4-38). The histologic appearance is reported to be that of a benign lymphoepithelial lesion, often with a prominent cystic component. Xerostomia has been reported to be associated with HIV infection. The cause is not clear. It may be related to medication administration or salivary gland disease.

Kumar, V., et al. Robbins basic pathology, ed 8. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Neville, B.W., et al. Oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 3. St. Louis: Saunders; 2009.

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute: http://www.hivguidelines.org (clinical guidelines).

Regezi, J.A., Sciubba, J.J., Jordan, R.C.K. Oral pathology: clinical-pathologic correlations, ed 5. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

Alves, M., et al. Longitudinal evaluation of loss of attachment in HIV-infected women compared to HIV-uninfected women. J. Periodont. 2006;77:773.

Baccaglini, L., et al. Management of oral lesions in HIV-positive patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;103(Suppl):S50.

Depaola, L.G. Human immunodeficiency virus disease: natural history and management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:266.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(RR-17):1.

Challacombe, S.J. Immunologic aspects of oral candidiasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:202.

Eisen, D. The clinical characteristics of intraoral herpes simplex virus infection in 52 immunocompetent patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:432.

Eisenberg, E., Krutchkoff, D., Yamase, H. Incidental oral hairy leukoplakia in immunocompetent persons. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:332.

Eng, H.-L., et al. Oral tuberculosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:415.

Fotos, P.G., Vincent, S.D., Hellstein, J.W. Oral candidiasis: clinical, historical, and therapeutic features of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:41.

Glick, M., Muzyka, B.C. Alternative therapies for major aphthous ulcers in AIDS patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:61.

Green, T.L., et al. Oral lesions mimicking hairy leukoplakia: a diagnostic dilemma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:422.

Greenspan, D., et al. Incidence of oral lesions in HIV-1-infected women: reduction with HAART. J Dent Res. 2004;83:145.

Hodgson, T.A., Greenspan, D., Greenspan, J.S. Oral lesions of HIV disease and HAART in industrialized countries. Adv Dent Res. 2006;19:57.

Harris, A.M., Van Wyk, C.W. Heck's disease (focal epithelial hyperplasia): a longitudinal study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:82.

Hernandez, Y.L., Daniels, T.E. Oral candidiasis in Sjögren's syndrome: prevalence, clinical correlations, and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:324.

Holbrook, W.P., Gunnlaugur, T.G., Ragnarsson, K.T. Herpetic gingivostomatitis in otherwise healthy adolescents and young adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:113.

Holmstrup, P., Westergaard, J. Periodontal diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1994;21:270.

Iacopino, A.M., Wathen, W.F. Oral candidal infection and denture stomatitis: a comprehensive review. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:46.

Jones, A.C., Gulley, M.L., Freedman, P.D. Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis in human immunodeficiency virus–seropositive individuals: a review of the histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and virologic characteristics of 18 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:323.

Koorbusch, G.F., Fotos, P., Terhark, K. Retrospective assessment of osteomyelitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:149.

Kulak-Ozkan, Y., Kazazoglu, E., Arikan, A. Oral hygiene habits, denture cleanliness, presence of yeasts and stomatitis in elderly people. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:300.

Leigh, J.E., Kishore, S., Fidel, P.L., Jr. Oral opportunistic infections in HIV-positive individuals: review and role of mucosal immunity. AIDS Patient Care. 2004;18:443.

Leggott, P.J. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:187.

Lynch, D.P. Oral candidiasis: history, classification and clinical presentation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:189.

MacPhail, L.A., et al. Recurrent aphthous ulcers in association with HIV infection: description of ulcer types and analysis of T-lymphocyte subsets. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:678.

MacPhail, L.A., et al. Differences in risk factors among clinical types of oral candidiasis in the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:45.

McKenzie, C.D., Gobetti, J.P. Diagnosis and treatment of orofacial herpes zoster: report of cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120:679.

Miller, R.L. The differential diagnosis of white lesions resembling oral hairy leukoplakia. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 1993;73:20.

Morrow, D.J., Sandhu, H.S., Daley, T.D. Focal epithelial hyperplasia (Heck's disease) with generalized lesions of the gingiva: a case report. J Periodontol. 1993;64:63.

Narana, N., Epstein, J.B. Classifications of oral lesions in HIV infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:137.

Pankhurst, C.L. Candidiasis (oropharyngeal). Clin Evid. 2006;15:1849.

Peterman, T.A., et al. The changing epidemiology of syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(Supp):S4.

Praetorius, F. HPV-associated diseases of the oral mucosa. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:399.

Rams, T.E., et al. Microbiological study of HIV-related periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1991;62:74.

Redding, S.W., Luce, E.B., Boren, M.W. Oral herpes simplex virus infection in patients receiving head and neck radiation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:578.

Robinson, J.L., Vaudry, W.L., Dobrovolsky, W. Actinomycosis presenting as osteomyelitis in the pediatric population. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:365.

Ryder, M.I. An update on HIV and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1071.

Samaranayake, L.P. Oral mycoses in HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:171.

Schiodt, M. HIV-associated salivary gland disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;37:164.

Shirlaw, P.J., et al. Oral and dental care and treatment protocols for the management of HIV-infected patients. Oral Dis. 2002;8(Suppl 2):136.

Siegel, M.A. Diagnosis and management of recurrent herpes simplex infections. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1245.

Soysa, N.S., Samaranayake, L.P., Ellepola, A.N. Diabetes mellitus as a contributory factor in oral candidosis. Diabet Med. 2006;23:455.

Swango, P.A., Kleinman, D., Konzelman, J.L. HIV and periodontal health. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:49.

Watkins, P. Impetigo: aetiology, complications and treatment options. Diabet Med. 2005;19:51.

Williams, C.A., et al. HIV-associated periodontitis complicated by necrotizing stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:351.

Zhu, W.Y., et al. Human papillomavirus DNA in the dermis of condyloma acuminatum. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:447.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. The most specific of the body's defense mechanisms against infection is:

A The primary lesion of syphilis is called a chancre.

B The secondary lesion of syphilis occurs at the site of inoculation with the

3. Perioral lesions of impetigo may resemble:

4. Which of the following is not associated with group A, β-hemolytic streptococcal

5. Oral candidiasis is caused by a:

A Angular cheilitis may be caused by Candida albicans.

B White lesions resulting from candidiasis may not rub off the mucosal surface.

C Erythematous candidiasis is usually completely asymptomatic.

7. Which type of infection is involved when normal components of the oral microflora can cause disease?

8. The most characteristic clinical feature of herpes zoster is:

9. A cytologic smear may be helpful in the diagnosis of:

10. Which condition is not associated with the Epstein-Barr virus?

11. Which of the following stages of syphilis is not infectious?

12. Which of the following is not associated with syphilis?

13. Which of the following microorganisms causes tuberculosis?

14. A positive skin reaction to PPD indicates:

15. A specific clinical characteristic found in actinomycosis is:

16. Which of the following is not a clinical characteristic of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis?

17. Which of the following is associated with chronic osteomyelitis?

18. Which of the following is not associated with the development of oral candidiasis?

A Clinically resembles an irritative fibroma.

B Is caused by a human papilloma virus.

20. Another name for a common wart is:

21. Which of the following is caused by a papilloma virus and is considered a sexually transmitted disease?

22. Painful oral ulcers, gingivitis, fever, malaise, and cervical lymphadenopathy in a child younger than 6 years old would cause the hygienist to suspect which of the following diseases?

23. The most common form of recurrent herpes simplex infection is:

24. The primary infection with the varicella-zoster virus is called:

26. Antibody testing to determine if a person has been infected with HIV includes which of the following tests?

27. Which one of the following oral conditions is an early sign of a deficiency in the immune system and is commonly found in patients with HIV infection?

28. Hairy leukoplakia most commonly occurs on the:

29. Which one of the following oral conditions is not a lesion associated with HIV or AIDS?

30. LGE has specific characteristics that include spontaneous bleeding, petechiae on the attached gingiva and alveolar mucosa, and a band of erythema at the gingival margin. Which one of the following statements is true?

A These tissues respond well to scaling and root planing.

B Excellent oral hygiene and home care techniques will eliminate these gingival conditions.

C This condition will automatically develop into advanced periodontal disease in all HIV patients.

D Linear gingival erythema patients do not respond to scaling or oral hygiene techniques; the gingival condition exists independently of the patient's oral hygiene status.