Research Problem and Purpose

We are constantly asking questions to better understand ourselves and the world around us. This human ability to wonder and ask creative questions about behaviors, experiences, and situations in the world provides a basis for identifying research topics and problems. Identifying a problem is the initial step, and one of the most significant, in conducting quantitative, qualitative, outcomes, and intervention research. The research purpose evolves from the problem and directs the subsequent steps of the research process.

Research topics are concepts or broad problem areas that researchers can focus on to enhance evidence-based nursing. Research topics contain numerous potential research problems, and each problem provides the basis for developing many research purposes. Thus, the identification of a relevant research topic and a challenging, significant problem can facilitate numerous study purposes to direct a lifetime program of research. However, the abundance of research topics and potential problems frequently are not apparent to an individual struggling to identify his or her first research problem.

This chapter differentiates a research problem from a purpose, identifies sources for research problems, and provides a background for formulating a problem and purpose for study. The criteria for determining the feasibility of a proposed study problem and purpose are described. The chapter concludes with examples of research topics, problems, and purposes from current quantitative, qualitative, outcomes, and intervention studies.

WHAT IS A RESEARCH PROBLEM AND PURPOSE?

A research problem is an area of concern where there is a gap in the knowledge base needed for nursing practice. Research is conducted to generate knowledge that addresses the practice concern, with the ultimate goal of providing evidence-based health care. A research problem can be identified by asking questions such as the following: What is wrong or is of concern in this clinical situation? What information do we need to improve this situation? Will a particular intervention work in a clinical situation? Would another intervention be more effective in producing the desired outcomes? What are the outcomes of the intervention? What changes must we make to improve this intervention based on the outcomes?

By questioning and reviewing the literature, the researcher will begin to recognize a specific area of concern and the knowledge gap that surrounds it. The knowledge gap, or what is not known about this clinical problem, determines the complexity and number of studies needed to generate essential knowledge for nursing practice (Wright, 1999). In addition to the area of concern, the research problem also identifies a population and often a setting for the study.

A research problem includes significance, background, and a problem statement. The significance of a problem indicates the importance of the problem to nursing and to the health of individuals, families, and communities; the background for a research problem briefly identifies what we know about the problem area; and the problem statement identifies the specific gap in the knowledge needed for practice. The following example research problem is from the study by Andrews, Felton, Wewers, Waller, and Tingen (2007), who examined the effects of a smoking cessation intervention on smoking cessation and abstinence in African-American women residing in public housing.

In this example, the research problem identifies an area of concern (tobacco use) for a particular population (African-American women) in a selected setting (public housing). The significance of the problem focuses on the health concerns with tobacco use and the high incidence of smoking among African-American women living in subsidized housing. The background research in this area identifies the reasons the women smoke and a community-based intervention that might encourage them to stop smoking. The last sentence in this example is the problem statement that identifies the gap in the knowledge needed for practice. In this study, there is limited research on specific interventions designed to encourage African-American women of low socioeconomic status to cease smoking.

The research problem in this example includes concepts or research topics such as tobacco use, preventable death, health disparities, cigarette smoking, smoking cessation intervention, low socioeconomic status, and smoking cessation. Smoking cessation intervention is an abstract concept, and a variety of nursing actions could be implemented to determine their effectiveness in encouraging members of different populations to give up smoking. Thus, each problem may generate many research purposes. The knowledge gap regarding the effectiveness of interventions to promote smoking cessation among African-American women of low socioeconomic status provides clear direction for formulating the research purpose.

The research purpose is a clear, concise statement of the specific goal or aim of the study that is generated from the research problem. The purpose usually indicates the type of study (quantitative, qualitative, outcomes, or intervention) to be conducted and often includes the variables, population, and setting for the study. The goals of quantitative research include identifying and describing variables, examining relationships among variables, and determining the effectiveness of interventions in managing clinical problems. The goals of qualitative research include exploring a phenomenon, such as depression as it is experienced by pregnant women; developing theories to describe and manage clinical situations; examining the health practices of certain cultures; and describing the historical evolution of leaders in the profession and of health-related issues, events, and situations (Munhall, 2001; Munhall & Boyd, 1999). The focus of outcomes research is to identify, describe, and improve the outcomes or end results of patient care (Doran, 2003). Intervention research focuses on investigating the effectiveness of a nursing intervention in achieving the desired outcomes in a natural setting (Sidani & Braden, 1998). Regardless of the type of research, every study needs a clearly expressed purpose statement. Andrews et al. (2007) clearly and concisely stated the purpose of their study following the literature review section of their article:

The purpose of this research was to test the effectiveness of a community-partnered intervention to promote smoking cessation among African American women in subsidized housing developments. (Andrews et al., 2007, p. 46)

This research purpose indicates that Andrews et al. conducted a quantitative quasi-experimental study to determine the effectiveness of an independent or treatment variable (a community-partnered smoking cessation intervention) on a dependent or outcome variable (smoking cessation) in a population of African American women living in public housing (setting). The researchers also identified five hypotheses to direct their study, which included additional dependent variables of social support, smoking cessation self-efficacy, and spiritual well-being (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of hypotheses). The study results showed a 6-month continuous smoking abstinence of 27.5% in the intervention group and 5.7% in the comparison group. Andrews et al. (2007, p. 45) indicated “These findings support the use of a nurse/community health worker model to deliver culturally tailored behavioral interventions with marginalized communities.” The findings from this study and other research provided evidence of the effectiveness of methods designed to manage smoking behaviors in marginalized populations.

SOURCES OF RESEARCH PROBLEMS

Research problems are developed from many sources, but you need to be curious, astute, and imaginative to identify problems from these sources. Moody, Vera, Blanks, and Visscher (1989) studied the source of research ideas and found that 87% came from clinical practice, 57% from the literature, 46% from interactions with colleagues, 28% from interactions with students, and 9% from funding priorities. These findings indicate that researchers often use more than one source to identify a research problem. The sources for research problems included in this text are (1) clinical practice, (2) researcher and peer interactions, (3) literature review, (4) theory, and (5) research priorities identified by funding agencies and specialty groups.

Clinical Practice

The practice of nursing must be based on knowledge or evidence generated through research. Thus, clinical practice is an extremely important source for research problems. Problems can evolve from clinical observations. For example, while watching the behavior of a patient and family in crisis, you may wonder how you as a nurse might intervene to improve the family’s coping skills. A review of patient records, treatment plans, and procedure manuals might reveal concerns or raise questions about practice that could be the basis for research problems. For example, you may wonder what nursing intervention will open the lines of communication with a patient who has had a stroke? What is the impact of home visits on the level of function, readjustment to the home environment, and rehospitalization pattern of a child with a severe chronic illness? What is the most effective treatment for acute and chronic pain? What is the best pharmacological agent or agents for treating hypertension in an elderly, African American, diabetic patient—βα-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker, calcium channel blocker, αα1 antagonist, or diuretic, or a combination of these drugs? What are the most effective pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for a patient with a serious and persistent mental illness? These significant clinical questions could direct you to research that will generate essential evidence for use in practice.

Extensive patient data, such as diagnoses, treatments, and outcomes, are now computerized. Analyzing this information might generate research problems that are significant to a clinic, community, or nation. For example, you may ask, why has adolescent obesity increased so rapidly in the past 10 years and what treatments will be effective in managing this problem? What pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments have been most effective in treating common acute illnesses such as otitis media, sinusitis, and bronchitis in your practice or nationwide? What are the outcomes (patient health status and costs) for treating such chronic illnesses as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in your practice? Some students and nurses keep logs or journals that contain research ideas derived from their practice (Artinian & Anderson, 1980). They might record their experiences, thoughts, and the observations of others. These logs often reveal patterns and trends in a setting and help these nurses and students to identify patient care concerns such as the following: Do the priority needs perceived by the patient direct the care received? Why do patients frequently fail to follow the treatment plan provided by their nurse practitioner or physician? How are family members involved in patient care, and what impact does this have on the family unit?

Questions about the effectiveness of and the desire to improve certain interventions and health care programs have led to the development of intervention effectiveness research (Sidani & Braden, 1998). Studies have focused on interventions directed at alleviating well-defined clinical problems and on a research program that combines interventions that address various aspects of patient health and are focused on improving overall health outcomes.

Because health care is constantly changing in response to consumer needs and trends in society, the focus of current research varies based on these needs and trends. For example, research evidence is needed to improve practice outcomes for infants and new mothers, the elderly and residents in nursing homes, and persons from vulnerable and culturally diverse populations. Health care agencies would benefit from studies of varied health care delivery models. Society would benefit from interventions recognized to promote health and prevent illness. In summary, clinically focused research is essential if nurses are to develop the knowledge needed for evidence-based practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005).

Researcher and Peer Interactions

Interactions with researchers and peers offer valuable opportunities for generating research problems. Experienced researchers serve as mentors and help novice researchers to identify research topics and formulate problems. Nursing educators assist students in selecting research problems for theses and dissertations. When possible, students conduct studies in the same area of research as the faculty. Faculty members can share their expertise regarding their research program, and the combined work of the faculty and students can build a knowledge base for a specific area of practice. This type of relationship could also be developed between an expert researcher and a nurse clinician. Building an evidence-based practice for nursing requires collaboration between nurse researchers and clinicians, as well as collaboration with researchers from other health-related disciplines.

Beveridge (1950) identified several reasons for discussing research ideas with others. Ideas are clarified and new ideas are generated when two or more people pool their thoughts. Interactions with others enable researchers to uncover errors in reasoning or information. These interactions are also a source of support in discouraging or difficult times. In addition, another person can provide a refreshing or unique viewpoint, which prevents conditioned thinking or following an established habit of thought. A workplace that encourages interaction can stimulate nurses to identify research problems. Nursing conferences and professional organization meetings also provide excellent opportunities for nurses to discuss their ideas and brainstorm to identify potential research problems.

The Internet has greatly extended the ability of researchers and clinicians around the world to share ideas and propose potential problems for research. Most schools of nursing have websites that identify faculty research interests and provide mechanisms for contacting individuals who are conducting research in your area of interest. Thus, interactions with others are essential to broaden your perspective and knowledge base and to support you in identifying significant research problems and purposes.

Literature Review

Reviewing research journals, such as Advances in Nursing Science, Applied Nursing Research, Clinical Nursing Research, Evidence Based Nursing, International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Journal of Advanced Nursing, Journal of Research in Nursing, Nursing Research, Nursing Science Quarterly, Research in Nursing & Health, Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research, and Western Journal of Nursing Research, as well as theses and dissertations will acquaint novice researchers with studies conducted in an area of interest. The nursing specialty journals, such as American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, Dimensions of Critical Care, Heart & Lung, Infant Behavior and Development, Journal of Pediatric Nursing, and Oncology Nursing Forum, also place a high priority on publishing research findings. Reviewing research articles enables you to identify an area of interest and determine what is known and not known in this area. The gaps in the knowledge base provide direction for future research. (See Chapter 6 for the process of reviewing the literature.)

At the completion of a research project, an investigator often makes recommendations for further study. These recommendations provide opportunities for others to build on a researcher’s work and strengthen the knowledge in a selected area. For example, the Andrews et al. (2007) study, introduced earlier in this chapter, examined the effect of a multicomponent smoking cessation intervention on the ability of African-American women to quit smoking and provided excellent recommendations for further research.

These researchers encouraged others to validate their findings through replication studies that varied the dosage and intensity of the CHW interventions. They also encouraged other researchers to generate new knowledge about the effects of spirituality interventions designed to improve the outcomes for study participants who sought to stop smoking and to make other lifestyle behavior changes.

Replication of Studies

Reviewing the literature is a way to identify a study to replicate. Replication involves reproducing or repeating a study to determine if similar findings will be obtained (Fahs, Morgan, & Kalman, 2003). Replication is essential for knowledge development because it (1) establishes the credibility of the findings, (2) extends the generalizability of the findings over a range of instances and contexts, (3) reduces the number of type I and type II errors, (4) corrects the limitations in studies’ methodologies, (5) supports theory development, and (6) lessens the acceptance of erroneous results (Beck, 1994; Fahs et al., 2003). Some researchers replicate studies because they agree with the findings and wonder if the findings will hold up in different settings with different subjects over time. Others want to challenge the findings or interpretations of prior investigators. Some researchers develop research programs focused on expanding the knowledge needed for practice in an area. This program of research often includes replication studies that strengthen the evidence for practice.

Four different types of replication are important in generating sound scientific knowledge for nursing: (1) exact, (2) approximate, (3) concurrent, and (4) systematic extension (Beck, 1994; Haller & Reynolds, 1986). An exact (or identical) replication involves duplicating the initial researcher’s study to confirm the original findings. All conditions of the original study must be maintained; thus, “there must be the same observer, the same subjects, the same procedure, the same measures, the same locale, and the same time” (Haller & Reynolds, 1986, p. 250). Exact replications might be thought of as ideal to confirm original study findings, but these are frequently not attainable. In addition, one would not want to replicate the errors in an original study, such as small sample size, weak design, or poor-quality measurement methods.

When conducting an approximate (or operational) replication, the subsequent researcher repeats the original study under similar conditions, following the methods as closely as possible (Beck, 1994). The intent is to determine whether the findings from the original study hold up despite minor changes in the research conditions. If the findings generated through replication are consistent with the findings of the original study, these data are more credible and have a greater probability of accurately reflecting the real world. If the replication fails to support the original findings, the designs and methods of both studies should be examined for limitations and weaknesses, and further research must be conducted. Conflicting findings might also generate additional theoretical insights and provide new directions for research.

For a concurrent (or internal) replication, the researcher collects data for the original study and the replication study simultaneously thereby checking the reliability of the original study (Beck, 1994; Brink & Wood, 1979). The confirmation, through replication of the original study findings, is part of the original study’s design. For example, your research team might collect data simultaneously at two different hospitals and compare and contrast the findings. Consistency in the findings increases the credibility of the study and the likelihood that others will be able to generalize the findings. Some expert researchers obtain funding to conduct multiple concurrent replications, in which a number of individuals conduct of a single study, but with different samples in different settings. Clinical trials that examine the effectiveness of the pharmacological management of chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, are examples of concurrent replication studies. As each study is completed, the findings are compiled in a report that specifies the series of replications that were conducted to generate these findings. Some outcome studies involve concurrent replication to determine if the outcomes vary for different health care providers and health care settings across the United States.

A systematic (or constructive) replication is done under distinctly new conditions. The researchers conducting the replication do not follow the design or methods of the original researchers; rather, the second investigative team identifies a similar problem but formulates new methods to verify the first researchers’ findings (Haller & Reynolds, 1986). The aim of this type of replication is to extend the findings of the original study and test the limits of the generalizability of such findings. Intervention research might use this type of replication to examine the effectiveness of various interventions devised to address a practice problem (Sidani & Braden, 1998).

Beck (1994) conducted a computerized and manual review of the nursing literature from 1983 through 1992 and found only 49 replication studies. Possibly, the number of replication studies is limited because (1) some view replication as less scholarly or less important than original research, (2) the discipline of nursing lacks resources for conducting replication studies, and (3) editors of journals limit the number of replication studies they publish (Beck, 1994; Fahs et al., 2003). However, the lack of replication studies severely limits the generation of sound research findings needed for evidence-based practice in nursing (Beck, 1994; Fahs et al., 2003; Martin, 1995; Reynolds & Haller, 1986). Thus, replicating a study should be respected as a legitimate scholarly activity for both expert and novice researchers. Funding from both private and federal sources is needed to support the conduct of replication studies, with a commitment from journal editors to publish these studies.

Replication provides an excellent learning opportunity for the novice researcher to conduct a significant study, validate findings from previous research, and generate new research evidence about different populations and settings. Students studying for their master’s degree could be encouraged to replicate studies for their theses, possibly to replicate faculty studies. Expert researchers, with programs of research, implement replication studies to generate sound evidence for use in practice. When developing and publishing a replication study, it is important to designate the type of replication conducted and the contribution the study made to the existing body of knowledge.

Landmark studies are significant research projects that not only generate knowledge but influence a discipline and sometimes society. These studies are frequently replicated or are the basis for the generation of additional studies. For example, Williams (1972) studied factors that contribute to skin breakdown, and these findings provided the basis for numerous studies on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Many of these studies are summarized in the document Pressure Ulcers in Adults: Prediction and Prevention published by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (Panel for the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers in Adults, 1992). Updates and revisions of this guideline can be found online at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (see www.ahrq.gov) and the National Guideline Clearinghouse (see www.guideline.gov).

Theory

Theories are an important source for generating research problems because they set forth ideas about events and situations in the real world that require testing (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). In examining a theory, one notes that it includes a number of propositions and that each proposition is a statement of the relationship of two or more concepts. A research problem and purpose could be formulated to explore or describe a concept or to test a proposition from a theory. In qualitative research, the purpose of the study might be to generate a theory to describe a new event or situation (Marshall & Rossman, 2006; Munhall, 2001).

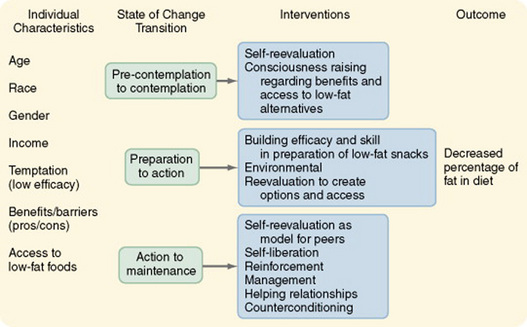

Some researchers combine ideas from different theories to develop maps or models for testing through research. The map serves as the framework for the study and includes key concepts and relationships from the theories that the researchers want to study. Frenn, Malin, and Bansal (2003, p. 38) conducted a quasi-experimental study to examine the effectiveness of a “4-session Health Promotion/transtheoretical Model-guided intervention in reducing percentage of fat in the diet and increasing physical activity among low- to middle-income culturally diverse middle school students.” The intervention was based on the “components of two behaviorally based research models that have been well tested among adults—Health Promotion Model (Pender, 1996) and Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska, Norcross, Fowler, Follick, & Abrams, 1992)—but have not been tested regarding low-fat diet with middle school–aged children” (Frenn et al., 2003, p. 36). They developed a model of the study framework (Figure 5-1) and described the concepts and propositions from the model that guided the development of different aspects of their study.

Figure 5-1 The health promotion stage of change model: A synthesis of health promotion and transtheoretical models guiding low-fat diet intervention for students in an urban middle school.

Frenn et al. (2003) used the Pender (1996) Health Promotion Model and the Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska et al., 1992) to develop the following research questions, which guided their study:

The findings from a study either support or do not support the relationships identified in the model. The study by Frenn et al. (2003) added support to the Health Promotion/Transtheoretical Model with their findings that the classroom intervention decreased dietary fat and increased physical activity for middle school–age adolescents. Further research is needed to determine if classroom interventions over time reduce body mass index, body weight, and the percentage of body fat of overweight and obese adolescents. As a graduate student, you could use this model as a framework and test some of the relationships in your clinical setting.

Research Priorities

Since 1975, expert researchers, specialty groups, professional organizations, and funding agencies have identified nursing research priorities. The research priorities for clinical practice were initially identified in a study by Lindeman (1975). Those original research priorities included nursing interventions related to stress, care of the aged, pain, and patient education. Developing evidence-based nursing interventions in these areas continues to be a priority.

Many professional nursing organizations use websites to communicate their current research priorities. For example, the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN) determined initial research priorities for this specialty in the early 1980s (Lewandowski & Kositsky, 1983) and revised these priorities in 1993 (Lindquist et al., 1993) and 1999. The most current AACN (2006) research priorities are identified on this organization’s website as (1) effective and appropriate use of technology to achieve optimal patient assessment, management, or outcomes; (2) creation of a healing, humane environment; (3) processes and systems that foster the optimal contribution of critical care nurses; (4) effective approaches to symptom management; and (5) prevention and management of complications. The AACN website is located at www.aacn.org (search for “research priorities”). If your specialty is critical care, this website might assist you in identifying a priority problem and purpose for study.

The American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE, 2006) provides a discussion of their research priorities online at www.aone.org/aone/edandcareer/priorities.html. For 2007, AONE identified more than 25 research priorities in four strategic areas: (1) design of future patient care delivery systems, (2) healthful practice environments, (3) leadership, and (4) the positioning nurse leaders as valued health care executives and managers. To promote the design of future patient care delivery systems, AONE encourages research focused on new technology, patient safety, and the work environment that allows strategies for improvement crucial to the success of the delivery system. In the area of healthful practice environments, AONE encourages research focused on practice environments that attract and retain nurses and promote professional growth and continuous learning, including mentoring of staff nurses and nursing leaders. In the area of leadership, AONE encourages research focused on evidence-based leadership capacity, measurement of patient care quality outcomes, and technology to complement patient care. To promote the positioning of nurse leaders as valued health care executives and managers, AONE encourages research focused on patient safety and quality, disaster preparedness, and workforce shortages. AONE recognizes the importance of supporting education and research initiatives to create a healthy work environment, a quality health care system, and strong nurse executives. You can search online for the research priorities of other nursing organizations to assist you in identifying priority problems for study.

A significant funding agency for nursing research is the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR). A major initiative of the NINR is the development of a national nursing research agenda that will involve identifying nursing research priorities, outlining a plan for implementing priority studies, and obtaining resources to support these priority projects. The NINR has an annual budget of more than $90 million with 74% of the budget used for extramural research project grants, 7% for predoctoral and postdoctoral training, 6% for research management and support, 5% for the centers program in specialized areas, 5% for other research including career development, 2% for the intramural program, and 1% for contracts and other expenses.

The NINR (2006) developed four strategies for building the science of nursing for 2006–2010: “(1) integrating biological and behavior science for better health; (2) adopting, adapting, and generating new technologies for better health care; (3) improving methods for future scientific discoveries; and (4) developing scientists for today and tomorrow.” The areas of research emphasis for 2006–2010 include (1) promoting health and preventing disease, (2) improving quality of life, (3) eliminating health disparities, and (4) setting directions for end-of-life research (NINR, 2006). Specific research priorities were identified for each of these four areas of research emphasis and included in the NINR Strategic Plan for 2006–2010. These research priorities provide important information for nurses seeking funding from the NINR. Details about the NINR mission, strategic plan, and areas of funding are available on its website at www.nih.gov/ninr.

Another federal agency that is funding health care research is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). The purpose of the AHRQ is to enhance the quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness of health care services, and access to such services, by establishing a broad base of scientific research and promoting improvements in clinical practice and in the organization, financing, and delivery of health care services. Some of the current funding priorities are research focused on prevention; health information technology; patient safety; long-term care; pharmaceutical outcomes; system capacity and emergency preparedness; and the cost, organization, and socio-economics of health care. For a complete list of funding opportunities and grant announcements, see the AHRQ website at www.ahcpr.gov.

Nursing research priorities are also being identified in Europe, Africa, and Asia. Some European countries (United Kingdom, Denmark, and Finland) have been conducting nursing research for more than 30 years, but most of the countries have been involved in nursing research for less than a decade. The European countries have identified the following research topics as priorities: (1) promoting health and well-being across the life span, (2) managing symptoms, (3) caring for the elderly, (4) evaluating cost-effectiveness, (5) restructuring health care systems, (6) examining self-care and self- management of health and illness, and (7) developing knowledge for practice (Tierney, 1998). The two major priorities for nursing research in Africa are human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and health behaviors. In Asia, limited nursing research is being conducted, with the priorities focused on health service research, including human resources and health outcomes (Henry & Chang, 1998).

The World Health Organization (WHO) is encouraging the identification of priorities for a common nursing research agenda among countries. A quality health care delivery system and improved patient and family health have become global goals. By 2020, the world’s population is expected to increase by 94%, with the elderly population increasing by almost 240%. Seven of every 10 deaths are expected to be caused by noncommunicable diseases, such as chronic conditions (heart disease, cancer, and depression) and injuries (unintentional and intentional). The priority areas for research identified by WHO are to (1) improve the health of the world’s most marginalized populations; (2) study new diseases that threaten public health around the world; (3) conduct comparative analyses of supply and demand of the health workforce of different countries; (4) analyze the feasibility, effectiveness, and quality of education and practice of nurses; (5) conduct research on health care delivery modes; and (6) examine the outcomes for health care agencies, providers, and patients around the world (WHO, 2006). A discussion of WHO’s mission, objectives, and research priorities can be found online at www.who.int/en.

Healthy People 2010 identifies and prioritizes the health objectives of all age groups over the next decade (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). These health objectives direct future research in the areas of health promotion, illness prevention, illness management, and rehabilitation and can be accessed online at www.health.gov. Betz (2002, pp. 154–155) identified 123 objectives from Healthy People 2010 that address the concerns of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. Some of the top health objectives for children include the following:

(1) increasing the proportion of persons with health insurance; (2) increasing the proportion of persons appropriately counseled about health behaviors; (3) reducing hospitalization rates for three ambulatory-care-sensitive conditions—pediatric asthma, uncontrolled diabetes, and immunization-preventable pneumonia and influenza; (4) reducing the proportion of children and adolescents who are overweight or obese; and (5) reducing the number of cases of HIV infections among adolescents and young adults. (Betz, 2002, pp. 154–155)

In summary, funding organizations, professional organizations, and governmental health care organizations nationally and internationally are sources for identifying priority research problems and offer opportunities for obtaining funding for future research.

FORMULATING A RESEARCH PROBLEM AND PURPOSE

Potential nursing research problems often emerge from real-world situations, such as those in nursing practice. A situation is a significant combination of circumstances that occur at a given time. Inexperienced researchers tend to want to study the entire situation, but it is far too complex for a single study. Multiple problems exist in a single situation, and each can be developed into a study. A researcher’s perception of what problems exist in a situation depends on that individual’s clinical expertise, theoretical base, intuition, interests, and goals. Some researchers spend years developing different problem statements and new studies from the same clinical situation.

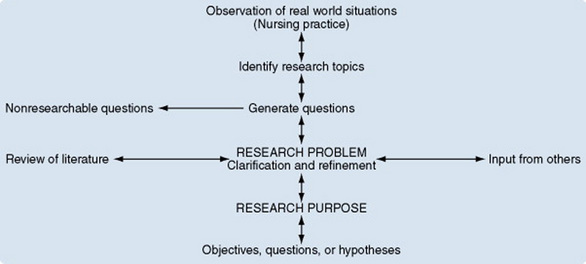

The exact thought processes used to extract problems from a situation have not been clearly identified because of the abstractness and complexity of the reasoning involved. However, in formulating their study problems, researchers often implement the following steps: (1) examine a real-world situation, (2) identify research topics, (3) generate questions, and (4) ultimately clarify and refine a research problem. From the problem, the researcher develops a specific goal or research purpose for study. The flow of these steps is presented in Figure 5-2 and described in the following sections.

Research Topics

A nursing situation often includes a variety of research topics or concepts that identify broad problem areas requiring investigation. Nurses frequently investigate patient- and family-related topics such as stress, pain, coping patterns, the teaching and learning process, self-care deficits, health promotion, rehabilitation, prevention of illness, disease management, and social support. Other relevant research topics focus on the health care system and providers, such as cost-effective care, advanced practice nurse role (nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, midwife, and nurse anesthetist), managed care, and redesign of the health care system. Outcomes research focuses on topics of health status, quality of life, cost-effectiveness, and quality of care. A specific outcome study might focus on a particular condition such as terminal cancer and examine outcomes such as nutrition, hygiene, skin integrity, and pain control with a variety of treatments (Doran, 2003).

Generating Questions

Situations encountered in nursing stimulate a constant flow of questions. The questions fit into three categories: (1) questions answered by existing knowledge, (2) questions answered with problem solving, and (3) research-generating questions. The first two types of questions are nonresearchable and do not facilitate the formulation of research problems that will generate knowledge for practice. Some of the questions raised have a satisfactory answer within the nursing profession’s existing body of knowledge, and these answers are available in the literature and online, from evidenced-based guidelines, or from experts in nursing or other disciplines. For example, suppose you have questions about performing some basic nursing skills, such as a protocol for taking a temperature or giving injections; you can find answers to questions such as these in the research literature and procedure manuals. However, suppose your questions focus on investigating new techniques to improve existing skills, patient responses to techniques, or ways to educate patients and families to perform techniques. Your efforts to answer these types of questions could add to knowledge needed for evidence-based practice.

Some of the questions raised can be answered using problem-solving or evaluation projects. The problem-solving process addresses a particular problem situation, and the goal of the research process is the generation of knowledge to be generalized to other similar situations. Many evaluation projects are conducted with minimal application of the rigor and control required with research. These projects do not fit the criteria of research, and the findings are relevant for a particular situation. For example, quality assurance is an evaluation of the patient care implemented by a specific health care agency; the results of this evaluation project are usually relevant only to the agency conducting the review.

The type of question that can initiate the research process is one that requires further knowledge to answer it. Some of the questions that come to mind about situations include the following: Is there a need to explore or describe concepts, to know how they are related, or to be able to predict or control some event within the situation? What is known and what is not known about the concepts? What are the most urgent factors or outcomes to know? Is there a need to generate or test theory in an area important to practice? Which intervention is most effective in achieving quality patient outcomes? Research experts have found that asking the right question is frequently more valuable than finding the solution to a problem. The solution identified in a single study might not withstand the test of time or might be useful in only a few situations. However, one well-formulated question can generate numerous research problems, direct a lifetime of research activities, and significantly contribute to a discipline’s body of knowledge.

Clarifying and Refining a Research Problem

Fantasy and creativity are part of formulating a research problem, so imagine prospective studies related to the situation. Imagine the difficulties likely to occur with each study, but avoid being too critical of potential research problems at this time. Which studies seem the most workable? Which ones appeal intuitively? Which problem is the most significant to nursing? Which study is of personal interest? Which problem has the greatest potential to provide a foundation for further research in the field? (See Campbell, Daft, & Hulin, 1982; Kahn, 1994; Wright, 1999.)

The problems investigated need to have professional significance and potential or actual significance for society. A research problem is significant when it has the potential to generate or refine knowledge to build an evidence-based practice for nursing (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). Moody et al. (1989) surveyed nurse researchers and identified the following criteria for significant research problems: They should be (1) focused on real-world concerns (57%), (2) methodologically sound (57%), (3) knowledge building (51%), (4) theory building (40%), and (5) focused on current or timely concerns (31%). The problems that are considered significant vary with time and the needs of society. The priorities identified earlier indicate some of the current, significant nursing research topics and problems.

Personal interest in a problem influences the quality of the problem formulated and the study conducted. A problem of personal interest is one that an individual has pondered for a long time or one that is especially important in the individual’s nursing practice or personal life. For example, if you know someone who has had a mastectomy, you may be particularly interested in studying the emotional impact of a mastectomy or strategies for caring for mastectomy patients. This personal interest in the topic can become the driving force needed to conduct a quality study (Beveridge, 1950).

Answering these questions regarding significance and personal interest can often assist you in narrowing the number of problems. Without narrowing potential problems to only one idea, try some of the ideas out on colleagues. Let them play the devil’s advocate and explore the strengths and weaknesses of each idea. Then begin some preliminary reading in the area of interest. Examine literature related to the situation, the variables within the situation, measurement of the variables, previous studies related to the situation, and supportive theories. The literature review often will enable you to refine the problem and clearly identify the gap in the knowledge base. Once you have identified the problem, you must frame it or ground it in past research, practice, and theory (Stone, 2002). The discussion of the problem must culminate in a problem statement that identifies the gap in the knowledge base that your proposed study will address. Thus, the refined problem has documented significance to nursing practice, is based on past research and theory, and identifies a gap in nursing knowledge that directs the development of the research purpose.

Research Purpose

The purpose is generated from the problem, identifies the goal or goals of the study, and directs the development of the study. In the research process, the purpose is usually stated after the problem, because the problem identifies the gap in knowledge in a selected area and the purpose clarifies the knowledge to be generated by a study. The research purpose must be stated objectively, that is, in a way that does not reflect particular biases or values of the researcher. Investigators who do not recognize their values might include their biases in the research. This can lead them to generate the answers they want or believe to be true and might add inaccurate information to a discipline’s body of knowledge (Kaplan, 1964). Therefore, based on your research purpose, you can develop specific research objectives, questions, or hypotheses to direct your study (see Chapter 8).

The purpose of an outcomes research project is usually complex and requires a team of multidisciplinary health care providers to accomplish it. Your research team members must be cautious in identifying a purpose that will make a significant contribution to the health care system and yet be feasible. Some possible purposes for outcomes research projects include the following:

(1) Comparing one treatment with another for effectiveness in the routine treatment of a particular condition; (2) describing in measurable terms the typical course of a chronic disease; (3) using variations in outcomes to identify opportunities for improving clinical process; and (4) developing decision support programs for use with individual patients when choosing among alternative treatment options. (Davies, Doyle, Lansky, Rutt, Stevic, & Doyle, 1994, p. 11)

EXAMPLE OF PROBLEM AND PURPOSE DEVELOPMENT

You might have observed the women receiving treatment at a psychiatric facility and noted that many were withdrawn, depressed, and unable to discuss certain events in their lives. Their progress in therapy was usually slow, and they seemed to have similar physical and psychological symptoms. Often, after developing a rapport with a therapist, they would reveal that they were victims of sexual abuse as a child. This situation could lead you to identify research topics and generate searching questions. Research topics of interest include sexual abuse, childhood incest, physical and psychological symptoms of incest, history of incest, assessment of emotional problems, and therapeutic interventions to manage sexual abuse. Possible questions include the following: What are the physical and psychological symptoms demonstrated by someone who has experienced childhood sexual abuse? How would one assess the occurrence, frequency, and impact of rape or incest on a woman? What influences do age and duration of abuse have on the woman’s current behavior? How frequently is childhood sexual abuse a problem in the mentally disturbed adult female? How does a health care provider assess and diagnose the emotional problems of adult survivors of child sexual abuse? What type of treatment is effective in an individual who has experienced child abuse? These are the types of questions that Brown and Garrison (1990) might have raised as they developed the following problem, purpose, and questions for their investigation.

Child sexual abuse is a significant health care topic because it occurs frequently and has a long-lasting impact on the victim’s physical and emotional health. The problem statement that “a systematic assessment tool is needed to identify childhood incest in this high-risk population” is supported by past research, practice, and theory.

This purpose clearly develops from the problem and identifies the goals of the study, which are to ascertain patterns of symptoms and design an assessment instrument. The variables studied are physical and psychosocial symptoms and an assessment instrument in a population of adult women incest survivors.

These research questions are clearly developed from the first part of the purpose, “to identify physical and psychosocial patterns of symptomatology.” However, there is no link of the research questions to the second part of the purpose that focused on designing an assessment instrument. This is a break in the logical flow of this study and could lead to problems in the development of the remaining steps of the research process.

FEASIBILITY OF A STUDY

As the research problem and purpose increase in clarity and conciseness, the researcher has greater direction in determining the feasibility of a study. The feasibility of a study is determined by examining the time and money commitment; the researcher’s expertise; availability of subjects, facility, and equipment; cooperation of others; and the study’s ethical considerations (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Rogers, 1987).

Time Commitment

Conducting research frequently takes longer than anticipated, which makes it difficult for any researcher, especially a novice, to estimate the time that will be involved. In estimating the time commitment, the researcher examines the purpose of the study; the more complex the purpose, the greater the time commitment. You can approximate the time needed to complete a study by assessing the following factors: (1) type and number of subjects needed, (2) number and complexity of the variables to be studied, (3) methods for measuring the variables (are instruments available to measure the variables or must they be developed?), (4) methods for collecting data, and (5) the data analysis process. Also, researchers often overlook the time commitment necessary to write the research report for presentation and publication. You must approximate the time needed to complete each step of the research process and determine whether the study is feasible.

Most researchers propose a designated period of time or set a specific deadline for their project. For example, an agency might set a 2-year deadline for studying the turnover rate of staff. The researcher must determine whether the identified purpose can be accomplished by the designated deadline; if not, the purpose could be narrowed or the deadline extended. Researchers are often cautious about extending deadlines because a project could continue for many years. The individual interested in conducting qualitative research frequently must make an extensive time commitment of 2 years or longer to allow for quality collection and analysis of data. Time is as important as money, and the cost of a study can be greatly affected by the time required to conduct it.

Money Commitment

The problem and purpose selected are influenced by the amount of money available to the researcher. Potential sources for funding should be considered at the time the problem and purpose are identified. For example, Andrews et al. (2007), who studied the effects of a smoking cessation intervention for African American women, obtained funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the American Legacy Foundation to support their study. Federal and private sources of funding greatly strengthen the feasibility of conducting a research project.

The cost of a research project can range from a few dollars for a student’s small study to hundreds of thousands of dollars for complex projects, such as multisite clinical trials and major qualitative studies. In estimating the cost of a research project, the following questions need to be considered as well as other areas of expense based on the study conducted:

1. Literature: What will the review of the literature —including computer searches, copying articles, and purchasing books—cost?

2. Subjects: How many subjects will need to be recruited for the study, and will the subjects have to be paid for their participation in the project?

3. Equipment: What will the equipment for the study cost? Can the equipment be borrowed, rented, bought, or obtained through donation? Is the equipment available, or will it need to be built? What type of maintenance will be required for the equipment during the study? What will the measurement instruments cost?

4. Personnel: Will assistants or consultants, or both, be hired to collect, computerize, and analyze the data and assist with the data interpretation? Will clerical help be needed to type and distribute the report and prepare a manuscript for publication?

5. Computer time: Will computer time be required to analyze the data? If so, what will be the cost?

6. Transportation: What will be the transportation costs for conducting the study and presenting the findings?

7. Supplies: Will any supplies—such as envelopes, postage, pens, paper, or photocopies—be needed? Will a cell phone be needed to contact the researcher about potential subjects? Will long-distance phone calls or overnight mailing be needed?

Researcher Expertise

A research problem and purpose must be selected based on the ability of the investigator. Initially, you might work with another researcher (mentor) to learn the process and then investigate a familiar problem that fits your knowledge base or experience. Selecting a difficult, complex problem and purpose can only frustrate and confuse the novice researcher. However, all researchers need to identify problems and purposes that are challenging and collaborate with other researchers as necessary to build their research background.

When a team of researchers conducts a study, the team members often have a variety of research and clinical experiences that add to the quality of the study conducted. In the study conducted by Andrews et al. (2007), these investigators had research and clinical expertise in biobehavioral nursing, public health, biostatistics, and pediatric medicine. They were all doctorally prepared and seasoned faculty members of universities, usually indicating research expertise. On the first page of the article the types of positions and employment sites for the investigators were identified as follows: (1) Andrews was an assistant professor, Department of Biobehavioral Nursing, Medical College of Georgia; (2) Felton was a professor at the College of Nursing, University of South Carolina; (3) Wewers was a professor and associate dean for research, Department of Public Health, Ohio State University; (4) Waller was an associate professor, Department of Biostatistics, Medical College of Georgia; and (5) Tingen was an associate professor, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Georgia (Andrews et al., 2007). The researchers all appear to have strong backgrounds for conducting research in the discipline of nursing and health care. You can obtain more information about the authors by searching their name online.

Availability of Subjects

In selecting a research purpose, you must consider the type and number of subjects needed. Finding a sample might be difficult if the study involves investigating a unique or rare population, such as quadriplegic individuals who live alone and are currently attending college. The more specific the population selected for study, the more difficult it is to find subjects. The money and time available to the researcher will affect the subjects selected. With limited time and money, the researcher might want to investigate subjects who are accessible and do not require payment for participation. Even if you identify a population with a large number of potential subjects, those individuals may be unwilling to participate in the study because of the topic selected. For example, nurses could be asked to share their experiences with alcohol and drug use, but many might fear that sharing this information would jeopardize their jobs and licenses. Researchers need to be prepared to pursue the attainment of subjects at whatever depth is necessary. Having a representative sample of reasonable size is critical for generating quality research findings (Kahn, 1994). Andrews et al. (2007) selected settings where they could obtain the sample size that they needed for their study of the smoking cessation intervention as identified in the following quote:

Two of 16 subsidized housing developments in Augusta-Richmond County, Georgia were selected based on similar number of residents, housing units, and household income from data supplied by the Augusta Housing Authority. These two low-income housing communities were 99.5% African American, with 95% living at or below the poverty level. Approximately 500 women resided in these two communities and an estimated 200 women were current smokers. (Andrews et al., 2007, p. 47)

Availability of Facilities and Equipment

Researchers need to determine whether their studies will require special facilities to implement. Will a special room be needed for an educational program, interview, or observations? If the study is conducted at a hospital, clinic, or school or college of nursing, will the agency provide the facilities that are needed? Setting up a highly specialized laboratory for the conduct of a study would be expensive and probably require external funding. Most nursing studies are done in natural settings such as a hospital room or unit, a clinic, or a patient’s home. Andrews et al. (2007) conducted all their research activities in the community centers for two housing developments (natural settings). The NINR and the American Legacy Foundation funding assisted with the study costs.

Nursing studies frequently require a limited amount of equipment, such as a tape or video recorder for interviews or a physiological instrument, such as a scale or thermometer. Often you can borrow equipment from the facility where the study is conducted, or you can rent it. Some companies are willing to donate equipment if the study focuses on determining the effectiveness of the equipment and the findings are shared with the company. If specialized facilities or equipment are required for a study, you must be aware of the options available before actively pursuing the study.

Cooperation of Others

A study might appear feasible but, without the cooperation of others, it is not. Some studies are conducted in laboratory settings and require the minimal cooperation of others. However, most nursing studies involve human subjects and are conducted in hospitals, clinics, schools, offices, or homes. Having the cooperation of people in the research setting, the subjects, and the assistants involved in data collection is essential. People are frequently willing to cooperate with a study if they view the problem and purpose as significant or if they are personally interested. Andrews et al. (2007) gained the support of the managers for the housing developments and the women living in these developments, so that 103 women participated in the study. Having the cooperation of others can improve the subject participation and promote the successful completion of the study (see Chapter 17 for details on the data collection process).

Ethical Considerations

The purpose selected for investigation must be ethical, which means that the subjects’ rights and the rights of others in the setting are protected. If your purpose appears to infringe on the rights of the subjects, you should reexamine that purpose and the investigation may have to be revised or abandoned. There are usually some risks in every study, but the value of the knowledge generated should outweigh the risks. Andrews et al. (2007) received Human Assurance Committee approval from two universities before the study started and informed consent from each of the study participants. By taking these steps, the researchers attempted to implement an ethical study that protected the rights of the African-American women who participated (see Chapter 9 for details on ethical conduct in research).

QUANTITATIVE, QUALITATIVE, OUTCOMES, AND INTERVENTION RESEARCH TOPICS, PROBLEMS, AND PURPOSES

Quantitative and qualitative research approaches enable nurses to investigate a variety of research problems and purposes. Examples of research topics, problems, and purposes for some of the different types of quantitative studies are presented in Table 5-1. The research purpose usually reflects the type of study that is to be conducted. The purposes of descriptive research are to describe variables, identify relationships among variables, or compare and contrast groups on selected variables. For example, Minnick, Mion, Johnson, Catrambone, and Leipzig (2007) described the prevalence and variation of physical restraint use in acute care settings in the United States. The research topics, problems, and purposes for this study are presented in Table 5-1.

TABLE 5-1

Quantitative Research: Topics, Problems, and Purposes

| Type of Research | Research Topic | Research Problem and Purpose |

| Descriptive research | Physical restraints, acute care hospitals, therapy disruption, patient safety | Title of study: “Prevalence and variation of physical restraint use in acute care settings in the U.S.” (Minnick et al., 2007, p. 30). |

| Problem: “Practitioners’ use of physical restraints (PR) in health care settings is a controversial practice that occurs in developed countries worldwide (Choi & Song, 2003; Hamers & Huizing, 2005…). Although intended to protect patients, physical restraint use can have direct deleterious effects, e.g., pressure ulcers and death…. For the past 15 years, U.S. regulatory and accrediting agencies have launched major initiatives aimed at restraint reduction in hospitals (U.S. DHHS [Department of Health and Human Services], 1992, 1995…). Despite these regulatory pressures, little is known about the current extent of PR use” (Minnick et al., 2007, p. 30). | ||

| Purpose: The purpose of this study was “to (a) describe U.S. hospital PR rates and patterns, and (b) explore how U.S. policy and research initiatives might be shaped by the findings” (Minnick et al., 2007, p. 30). | ||

| Correlational research | Hypertension, blood pressure, psychosocial factors, biological factors | Title of study: “The relationships among anxiety, anger, and blood pressure in children” (Howell et al., 2007, p. 17). |

| Problem: “Hypertension affects over 50 million Americans aged 6 and over and is a recognized risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease (American Heart Association, 2004). Although few children have hypertension or cardiovascular disease, biological and psychosocial risk factors for the development of hypertension in adulthood are estimated to be present in children by the age of 8 (Solomon & Matthews, 1999)…. Although the contribution of these factors to the development of hypertension has been investigated in adults and adolescents… much less research has been done with children (Hauber, Rice, Howell, & Carmon, 1998)” (Howell et al., 2007, p. 17). | ||

| Purpose: “The purpose of this study was to determine the relationships between trait anxiety, trait anger, height, weight, patterns of anger expression, and blood pressure in a group of elementary school children” (Howell et al., 2007, p. 18). | ||

| Quasi-experimental research | Obesity, overweight, coping skills, behavior control, stress management, multiethnic | Title of study: “An intervention for multiethnic obese parents and overweight children” (Berry et al., 2007). |

| Problem: “Obesity is increasing at an alarming rate in the United States [U.S.]. The percentage of at risk for overweight or overweight children and overweight and obese adults has increased dramatically over the past 40 years, with Black, Hispanic, and native American families disproportionately affected (Jolliffe, 2004; U.S. Department of health and Human Services, 2001). Currently, 64% of adults are either overweight or obese, and 30% of the children.… Coping skills training (CST) is a form of a cognitive behavioral intervention and is based on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), which is designed to improve self- efficacy outcomes…. Grey, Boland, Davidson, Li, and Tamborlane (2000) found that in female patients with type 1 diabetes, CST prevented weight gain and improved long-term metabolic and psychosocial outcomes… There are no data about interventions using CST to target multiethnic obese parents and their overweight children attending weight management programs” (Berry et al., 2007, pp. 63–64.) | ||

| Purpose: “The purpose of this pilot study was to determine the effects of the addition of coping skills training for obese multiethnic parents whose overweight children were attending a weight management program” (Berry et al., 2007, 63). | ||

| Experimental research | Pain management, morphine, beta-endorphin, circadian rhythm, animals | Title of study: “Effects of morphine and time of day on pain and beta-endorphin” (Rasmussen & Farr, 2003). |

| Problem: “Although narcotics have been used as analgesics for many years, clients still are experiencing pain.… Morphine is an important pharmacological modulator of pain and initiator of analgesia.… Circadian (approximately 24 hours) rhythms influence the expression of pain and the body’s responsiveness to analgesic medications (Gagnon et al., 2001).… Endogenous opioids, such as morphine, activate the descending pain control system.… Currently, the timing of the administration of morphine is not based on its circadian effects. Both PLRL [paw-licking response latency in mice] and BE [beta-endorphin] are known to exhibit a circadian rhythm, or a rhythm that repeats once in a 24-hour period. Yet no well-controlled, time-based studies have been conducted to test the effects of morphine on pain response (PLRL) and plasma BE when administered at different times of day” (Rasmussen & Farr, 2003, pp. 105–107). | ||

| Purpose: The purpose of the study was to “investigate whether there were time-of-day differences in the effects of morphine on the pain tolerance threshold and the circadian plasma BE response to pain” (Rasmussen & Farr, 2003, p. 107). |

The purpose of correlational research is to examine the type (positive or negative) and strength of relationships among variables. In their correlational study, Howell, Rice, Carmon, and Hauber (2007) examined the relationships among anxiety, anger, and blood pressure in children (see Table 5-1). Quasi- experimental studies are conducted to determine the effect of a treatment or independent variable on designated dependent or outcome variables. Berry, Savoye, Melkus, and Grey (2007) examined the effects of a coping skills training (CST) intervention on the body mass index (BMI) and body fat percentage (BFP) of obese multiethnic parents whose overweight children were attending a weight management program. The parents receiving the CST had significantly lower BMI and BFP than the parents in the comparison group (Berry et al., 2007).

Experimental studies are conducted in highly controlled settings and under highly controlled conditions to determine the effect of one or more independent variables on one or more dependent variables. Rasmussen and Farr (2003) conducted an experimental study of the effects of morphine and time of day on pain and beta-endorphin (BE) in groups of mice in a laboratory setting. In this basic research, the investigators found that morphine abolishes the BE response to pain but does not inhibit pain equally at all times of the day. Thus, morphine doses should be titrated to maximize pain control with less medication. However, additional human research is needed before the findings will have implications for nursing practice.

The problems formulated for qualitative research identify an area of concern that requires investigation. The purpose of a qualitative study indicates the focus of the study and whether it is a subjective concept, an event, a phenomenon, experience, or a facet of a culture or society (Marshall & Rossman, 2006; Munhall, 2001). Examples of research topics, problems, and purposes from some different types of qualitative studies are presented in Table 5-2. Phenomenological research seeks an understanding of human experience from an individual researcher’s perspective, such as the lived experience of adult survivors of childhood cancer conducted by Prouty, Ward-Smith, and Hutto (2006). Four themes emerged from this study: “(1) ongoing consequences for having had cancer, (2) living with uncertainty, (3) the cancer experience is embodied into one’s present sense of self, and (4) support is valued” (Prouty et al., 2006, p. 143).

TABLE 5-2

Qualitative Research: Topics, Problems, and Purposes

| Type of Research | Research Topic | Research Problem and Purpose |

| Phenomenological research | Lived experience, childhood cancer, survivorship, phenomenology | Title of study: “The lived experience of adult survivors of childhood cancer” (Prouty et al., 2006, p. 143). |

| Problem: “In the mid-1970s fewer than 65% of children diagnosed with cancer survived 5 years…. Today, as many as 78% of children diagnosed with and treated for cancer before age 20 survive 5 years, and as many as 70% of those survivors live to adulthood (American Cancer Society, 2000). By 2010, it is estimated that 1 in every 250 young adults will be a long-term survivor of childhood cancer…. Physical consequences of cancer and treatment are well documented in the literature, and psychosocial issues have also been addressed. However, little is known about the adult survivor’s perspective of living with the consequences of having had and having been treated for cancer” (Prouty et al., 2006, pp. 143–144). | ||

| Purpose: “The purpose of this phenomenological study was to examine the lived experience of 12 adults who survived childhood cancer” (Prouty et al., 2006). | ||

| Grounded theory research | Self-care, poverty, schizophrenia, diabetes mellitus | Title of study: “Doing my best: Poverty and self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus” (El-Mallakh, 2007, p. 49). |

| Problem: “Mental health clinicians and researchers increasingly recognize that individuals with schizophrenia have a high risk of developing diabetes mellitus (DM) (Bushe & Holt, 2004…). Whereas rates of diabetes in the general populations range from 2% to 6%, prevalence rates of diabetes among individuals with schizophrenia range from 15% to 18%, and up to 30% have impaired glucose tolerance (Bushe & Holt, 2004; Schizophrenia and Diabetes Expert Consensus Group, 2004)…. The recent mental health literature has focused on the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of diabetes in this population, including discussions of the risks and benefits of atypical antipsychotic use…. However, few researchers have investigated the influence of social and demographic characteristics on diabetic self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes” (El-Mallakh, 2007, pp. 49–50). | ||

| Purpose: “A grounded theory study was conducted to examine several aspects of diabetic self-care in individuals with schizophrenia and DM” (El-Mallakh, 2007, p. 50). | ||

| Ethnography research | Critical illness, mechanical ventilation, weaning, family presence | Title of study: “Family presence and surveillance during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation” (Happ et al., 2007, p. 47). |

| Problem: “During critical illness, mechanical ventilation imposes physical and communication barriers between family members and their critically ill loved ones…. Most studies of family members in the intensive care unit (ICU) have focused on families’ needs for information, access to the patient, and participation in decisions to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment…. Although numerous studies have been conducted of patient experiences with short- and long-term mechanical ventilation (LTMV), research has not focused on family interactions with patients during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Moreover, the importance of family members’ bedside presence and clinicians’ interpretation of family behaviors at the bedside have not been critically examined” (Happ et al., 2007, pp. 47–48). | ||

| Purpose: “With the use of data from an ethnographic study of the care and communication processes during weaning from LTMV, we sought to describe how family members interact with the patients and respond to the ventilator and associated ICU bedside equipment during LTMV weaning” (Happ et al., 2007, p. 48). | ||

| Historical research | Disclosure, terminal status, death, dying, historical analysis | Title of study: “An historical analysis of disclosure of terminal status” (Krisman-Scott, 2000). |

| Problem: “In the last century the manner and place in which Americans experience death has changed. Sudden death has decreased and slow dying has increased…. Often, in response to both avoidance and denial, the dying pretend to be unaware. This cycle of pretense, instead of being helpful, robs a person of the opportunity to make appropriate end-of-life decisions and maintain power and control over what remains of life.… Nurses, for a variety of reasons, have for the most part avoided telling people they are close to death, even though secrecy creates serious problems in caring for the dying.… The amount of information given to patients about illness, treatment, and prognosis has changed over time. Movement toward greater disclosure of health information to patients has occurred in the past 60 years” (Krisman-Scott, 2000, p. 47). | ||

| Purpose: “The purpose of this study was to examine the concept of disclosure as it relates to terminal prognosis and trace its historical development and practice in the United States over the last 60 years” (Krisman-Scott, 2000, p. 47). | ||

| Philosophical analysis research | Rights, human rights, patient rights, health care | Title of study: “Conceptual analysis of rights using a philosophic inquiry approach” (Reckling, 1994). |

| Problem: “Nurses encounter the word right(s) in many aspects of their personal and professional lives. Patients’ rights documents are displayed in healthcare institutions.… Yet the idea of rights often is not understood clearly. For instance, controversy exists regarding whether access to healthcare is a human right. Furthermore, individual rights are not always honored. Sometimes rights are in conflict, as when one individual’s right to confidentiality conflicts with another’s right to information” (Reckling, 1994, p. 309). | ||

| Purpose: “Philosophers have analyzed the ontology and epistemology of rights: Do rights exist? If so, what constitutes them? How do we recognize one when we see it? Where do rights originate? What does having a right imply?” (Reckling, 1994, p. 311). | ||

| Critical social theory research | Oppressed group behaviors | Title of study: “A case study of oppressed group behavior in nurses” (Hedin, 1986). |

| Problem: “The study of the behavior of others sometimes reflects our own behaviors.” | ||

| Purpose: “A study was carried out in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) to analyze the social, economic, and political factors affecting the nursing education system…. Theoretical constructs from the work of critical social theorist Jurgen Habermas and adult educator Paulo Freire were used to achieve a deeper understanding of the interrelations between the cultural context and the nursing education system as well as to provide direction for conceptualizing ways to transcend oppressive circumstances” (Hedin, 1986, p. 53). |

In grounded theory research, the problem identifies the area of concern and the purpose indicates the focus of the theory to be developed from the research (Munhall, 2001). For example, El-Mallakh (2007) investigated the poverty and self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Based on the findings from this grounded theory study, El-Mallakh (2007, p. 49) developed a “model, Evolving Self-Care, that describes the process by which respondents developed health beliefs about self-care of dual illnesses. One subcategory of the model, Doing My Best, was further analyzed to examine the social context of respondents’ diabetic self-care.”

In ethnographic research, the problem and purpose identify the culture and the specific attributes of the culture to be examined, described, analyzed, and interpreted. Happ, Swigart, Tate, Arnold, Sereika, and Hoffman (2007) conducted an ethnographic study of family presence and surveillance during weaning of their family member from a ventilator. These researchers concluded that “this study provided a potentially useful conceptual framework of family behaviors with long-term critically ill patients that could enhance the dialogue about family-centered care and guide future research on family presence in the intensive care unit” (Happ et al., 2007, p. 47).

The problem and purpose in historical research focus on a specific individual, a characteristic of society, an event, or a situation in the past and identify the period in the past that will be examined. For example, Krisman-Scott (2000) conducted a historical study of disclosure of terminal status from 1930 to 1990 (see Table 5-2). The researcher concluded that disclosure of terminal status has slowly changed over time, from concealment in the 1930s to more general acceptance of disclosure today. The groundwork for the change took place in the 1950s and 1960s and culminated in the 1970s. This change is based on the expanding view of individual rights, perceptions of death, and the responsibilities of health care providers. The information from this study can assist nurses in knowing what and when to communicate to patients with terminal illness.

The problem and purpose in philosophical inquiry identify the focus of the analysis, whether it is to clarify meaning, make values manifest, identify ethics, or examine the nature of knowledge. Of the three types of philosophical inquiry (foundational inquiry, philosophical analysis, and ethical analysis), only an example of philosophical analysis is provided with an analysis of the concept of “rights” (Reckling, 1994). The problem and purpose in critical social theory identify a society and indicate the particular aspects of the society that will be examined to determine their influence on an event, a situation, or a system in that society. Hedin (1986) conducted critical social theory research in examining the oppressed group behaviors in nurses.