Carbohydrates and Lipids

Introduction

Carbohydrates and lipids are major sources of energy and are stored in the body as glycogen and triglycerides

This chapter describes the structure of carbohydrates and lipids found in the diet and in tissues. These two classes of compounds differ significantly in physical and chemical properties. Carbohydrates are hydrophilic; the smaller carbohydrates, such as milk sugar and table sugar, are soluble in aqueous solution, while polymers such as starch or cellulose form colloidal dispersions or are insoluble. Lipids vary in size, but rarely exceed 2 kDa in molecular mass; they are insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents. Both carbohydrates and lipids may be bound to proteins and have important structural and regulatory functions, which are elaborated in later chapters. This chapter ends with a description of the fluid mosaic model of biological membranes, illustrating how protein, carbohydrates and lipids are integrated into the structure of biological membranes that surround the cell and intracellular compartments.

Carbohydrates

Nomenclature and structure of simple sugars

The classic definition of a carbohydrate is a polyhydroxy aldehyde or ketone

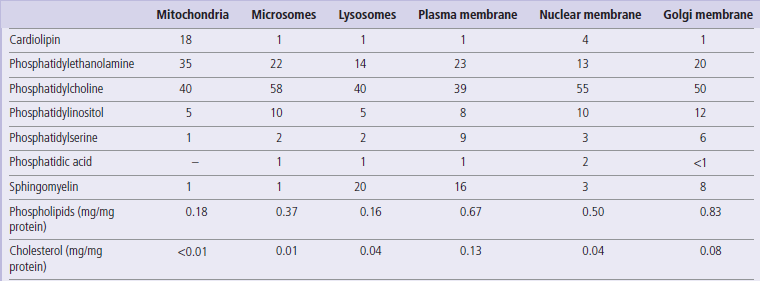

The simplest carbohydrates, having two hydroxyl groups, are glyceraldehyde and dihydroxyacetone (Fig. 3.1). These three-carbon sugars are trioses; the suffix ‘ose’ designates a sugar. Glyceraldehyde is an aldose, and dihydroxyacetone a ketose sugar. Prefixes and examples of longer-chain sugars are shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1

Classification of carbohydrates by length of the carbon chain

| Number of carbons | Name | Examples in human biology |

| Three | Triose | Glyceraldehyde, dihydroxyacetone |

| Four | Tetrose | Erythrose |

| Five | Pentose | Ribose, ribulose*, xylose, xylulose*, deoxyribose |

| Six | Hexose | Glucose, mannose, galactose, fucose, fructose |

| Seven | Heptose | Sedoheptulose* |

| Eight | Octose | None |

| Nine | Nonose | Neuraminic (sialic) acid |

*The syllable ‘ul’ indicates that a sugar is ketose; the formal name for fructose would be ‘gluculose’. As with fructose, the keto group is located at C-2 of the sugar, and the remaining carbons have the same geometry as the parent sugar.

Fig. 3.1 Structures of the trioses: D- and L-glyceraldehyde (aldoses) and dihydroxyacetone (a ketose).

Numbering of the carbons begins from the end containing the aldehyde or ketone functional group. Sugars are classified into the D or L family, based on the configuration around the highest numbered asymmetric center (Fig. 3.2). In contrast to the L-amino acids, nearly all sugars found in the body have the D configuration.

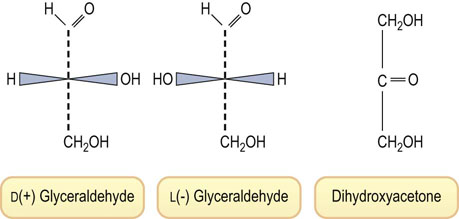

Fig. 3.2 Structures of hexoses: D- and L-glucose, D-mannose, D-galactose and D-fructose.

The D and L designations are based on the configuration at the highest numbered asymmetric center, C-5 in the case of hexoses. Note that L-glucose is the mirror image of D-glucose, i.e. the geometry at all of the asymmetric centers is reversed. Mannose is the C-2 epimer, and galactose the C-4 epimer of glucose. These linear projections of carbohydrate structures are known as Fischer projections.

An aldohexose, such as glucose, contains four asymmetric centers, so that there are 16 (24) possible stereoisomers, depending on whether each of the four carbons has the D or L configuration (see Fig. 3.2). Eight of these aldohexoses are D-sugars. Only three of these are found in significant amounts in the body: glucose (blood sugar), mannose and galactose (see Fig. 3.2). Similarly, there are four possible epimeric D-ketohexoses; fructose (fruit sugar) (see Fig. 3.2) is the only ketohexose present at significant concentration in our diet or in the body.

Because of their asymmetric centers, sugars are optically active compounds. The rotation of plane polarized light may be dextrorotatory (+) or levorotatory (−). This designation is also commonly included in the name of the sugar; thus D(+)-glucose or D(−)-fructose indicates that the D form of glucose is dextrorotatory, while the D form of fructose is levorotatory.

Cyclization of sugars

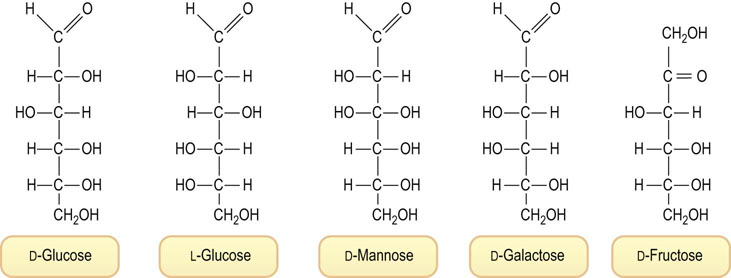

The linear sugar structures shown in Figure 3.2 imply that aldose sugars have a chemically reactive, easily oxidizable, electrophilic, aldehyde residue. Aldehydes such as formaldehyde or glutaraldehyde react rapidly with amino groups in protein to form Schiff base (imine) adducts and crosslinks during fixation of tissues. However, glucose is relatively resistant to oxidation and does not react rapidly with protein. As shown in Figure 3.3, glucose exists largely in nonreactive, inert, cyclic hemiacetal conformations, 99.99% in aqueous solution at pH 7.4 and 37°C. Of all the D-sugars in the world, D-glucose exists to the greatest extent in these cyclic conformations, making it the least oxidizable and least reactive with protein. It has been proposed that the relative chemical inertness of glucose is the reason for its evolutionary selection as blood sugar.

Fig. 3.3 Linear and cyclic representations of glucose and fructose.

(Top) There are four cyclic forms of glucose, in equilibrium with the linear form: α- and β-glucopyranose and α- and β-glucofuranose. The pyranose forms account for over 99% of total glucose in solution. These cyclic conformations are known as Haworth projections; by convention, groups to the right in Fischer projections are shown below the ring, and groups to the left, above the ring. The squiggly bonds to H and OH from C-1, the anomeric carbon, indicate indeterminate geometry and represent either the α or the β anomer. (Middle) The linear and cyclic forms of fructose. The ratio of pyranose : furanose forms of fructose in aqueous solution is ∼3 : 1. The ratio shifts as a function of temperature, pH, salt concentration and other factors. (Bottom) Stereochemical representations of the chair forms of α- and β-glucopyranose. The preferred structure in solution, β-glucopyranose, has all of the hydroxyl groups, including the anomeric hydroxyl group, in equatorial positions around the ring, minimizing steric interactions.

When glucose cyclizes to a hemiacetal, it may form a furanose or pyranose ring structure, named after the 5- and 6-carbon cyclic ethers, furan and pyran (see Fig. 3.3). Note that the cyclization reaction creates a new asymmetric center at C-1, which is known as the anomeric carbon. The preferred conformation for glucose is the β-anomer (∼65%) in which the hydroxyl group on C-1 is oriented equatorial to the ring. The β-anomer is the most stable form of glucose because all of the hydroxyl groups, which are bulkier than hydrogen, are oriented equatorially, in the plane of the ring. The α- and β-anomers of glucose can be isolated in pure form by selective crystallization from aqueous and organic solvents. They have different optical rotations, but equilibrate over a period of hours in aqueous solution to form the equilibrium mixture of 65 : 35 β : α anomer. These differences in structure may seem unimportant, but in fact some metabolic pathways use one anomer but not the other, and vice versa. Similarly, while the fructopyranose conformations are the primary forms of fructose in aqueous solution, most of fructose metabolism proceeds from the furanose conformation.

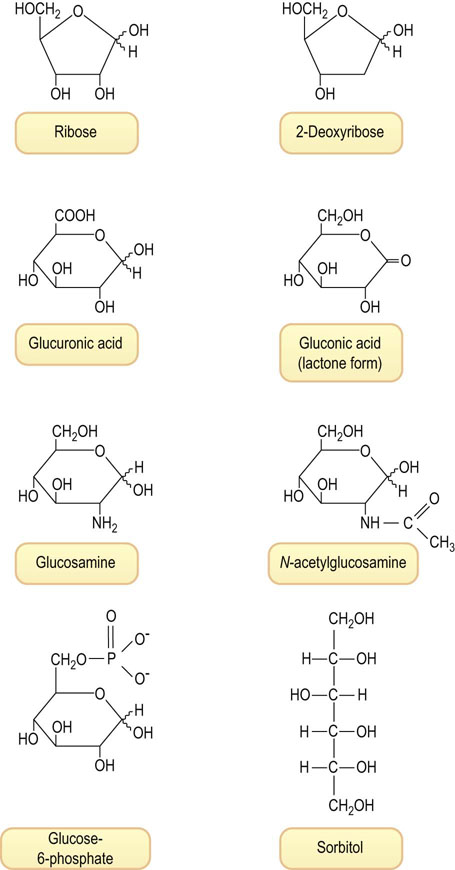

In addition to the basic sugar structures discussed above, a number of other common sugar structures are presented in Figure 3.4. These sugars, deoxysugars, aminosugars and sugar acids, are found primarily in oligosaccharide or polymeric structures in the body, e.g. ribose in RNA and deoxyribose in DNA, or they may be attached to proteins or lipids to form glycoconjugates (glycoproteins or glycolipids, respectively). Glucose is the only sugar found to a significant extent as a free sugar (blood sugar) in the body.

Fig. 3.4 Examples of various types of sugars found in human tissues.

Ribose, the pentose sugar in ribonucleic acid (RNA); 2-deoxyribose, the deoxypentose in DNA; glucuronic acid, an acidic sugar formed by oxidation of C-6 of glucose; gluconic acid, an acidic sugar formed by oxidation of C-1 of glucose, shown in the δ-lactone form; glucosamine, an amino sugar; N-acetylglucosamine, an acetylated amino sugar; glucose-6-phosphate, a phosphate ester of glucose, an intermediate in glucose metabolism; sorbitol, a polyol formed on reduction of glucose.

Disaccharides, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides

Sugars are linked to one another by glycosidic bonds to form complex glycans

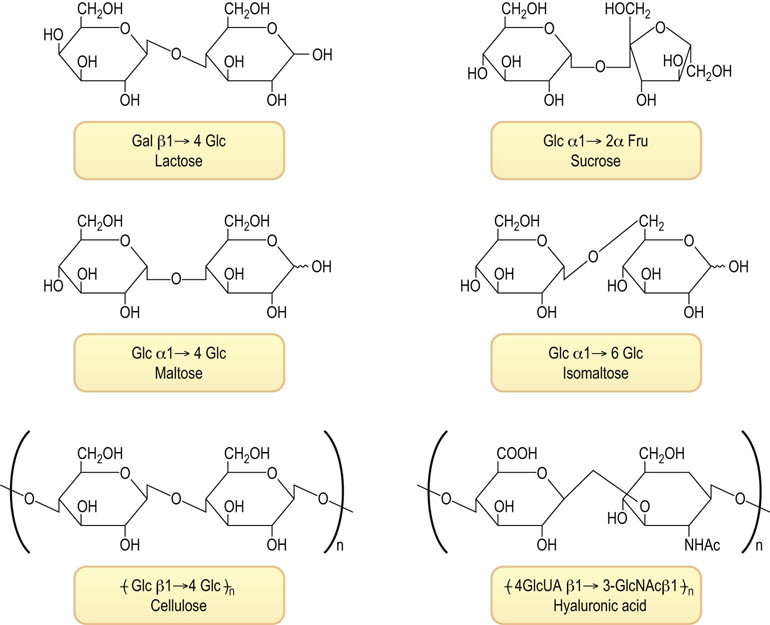

Carbohydrates are commonly coupled to one another by glycosidic bonds to form disaccharides, trisaccharides, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides. Saccharides composed of a single sugar are termed homoglycans, while saccharides with complex composition are termed heteroglycans. The name of the more complex structures includes not only the name of the component sugars but also the ring conformation of the sugars, the anomeric configuration of the linkage between sugars, the site of attachment of one sugar to another, and the nature of the atom involved in the linkage, usually an oxygen or O-glycosidic bond, sometimes a nitrogen or N-glycosidic bond. Figure 3.5 shows the structure of several common disaccharides in our diet: lactose (milk sugar), sucrose (table sugar), maltose and isomaltose, which are products of digestion of starch, cellobiose, which is obtained on hydrolysis of cellulose, and hyaluronic acid.

Fig. 3.5 Structures of common disaccharides and polysaccharides.

Lactose (milk sugar); sucrose (table sugar); maltose and isomaltose, disaccharides formed on degradation of starch; and repeating disaccharide units of cellulose (from wood) and hyaluronic acid (from vertebral disks). Fru, fructose; Gal, galactose; Glc, glucose; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; GlcUA, glucuronic acid.

Differences in linkage of sugars make a big difference in metabolism and nutrition

Amylose, a component of starch, is an α-1→4-linked linear glucan, while cellulose is a β-1→4-linked linear glucan. These two polysaccharides differ only in the anomeric linkage between glucose subunits, but they are very different molecules. Starch is soluble in water, cellulose is insoluble; starch is pasty, cellulose is fibrous; starch is digestible, while cellulose is indigestible by humans; starch is a food, rich in calories, while cellulose is roughage.

Lipids

Lipids are found primarily in three compartments in the body: plasma, adipose tissue and biological membranes

This introduction will focus on the structure of fatty acids (the simplest form of lipids, found primarily in plasma), triglycerides (the storage form of lipids, found primarily in adipose tissue), and phospholipids (the major class of membrane lipids in all cells). Steroids, such as cholesterol, and (glyco)sphingolipids will be mentioned in the context of biological membranes, but these lipids and others, such as the eicosanoids, will be addressed in detail in later chapters.

Fatty acids

Fatty acids exist in free form and as components of more complex lipids

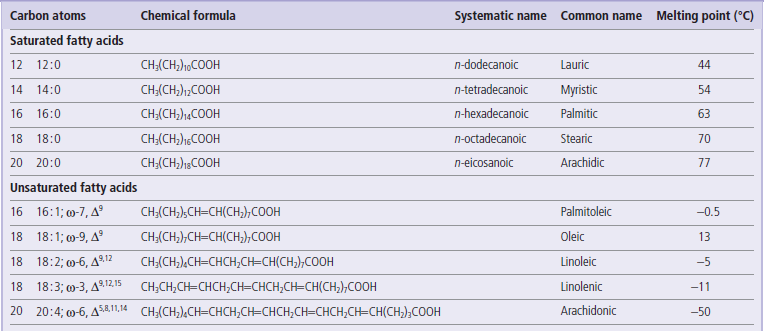

As summarized in Table 3.2, they are long, straight-chain alkanoic acids, most commonly with 16 or 18 carbons. They may be saturated or unsaturated, the latter containing 1–5 double bonds, all in cis geometry. The double bonds are not conjugated, but separated by methylene groups.

Table 3.2

Structure and melting point of naturally occurring fatty acids in the body

For unsaturated fatty acids, the ω designation indicates the location of the first double bond from the methyl end of the molecule; the Δ superscripts indicate the location of the double bonds from the carboxyl end of the molecule. Unsaturated fatty acids account for about two-thirds of all fatty acids in the body; oleate and palmitate account for about one half and one quarter of total fatty acids.

Fatty acids with a single double bond are described as monounsaturated, while those with two or more double bonds are described as polyunsaturated fatty acids. The polyunsaturated fatty acids are commonly classified into two groups, ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids, depending on whether the first double bond appears three or six carbons from the terminal methyl group. The melting point of fatty acids, as well as that of more complex lipids, increases with the chain length of the fatty acid, but decreases with the number of double bonds. The cis-double bonds place a kink in the linear structure of the fatty acid chain, interfering with close packing, therefore requiring a lower temperature for freezing, i.e. they have a lower melting point.

Triacylglycerols (triglycerides)

Triglycerides are the storage form of lipids in adipose tissue

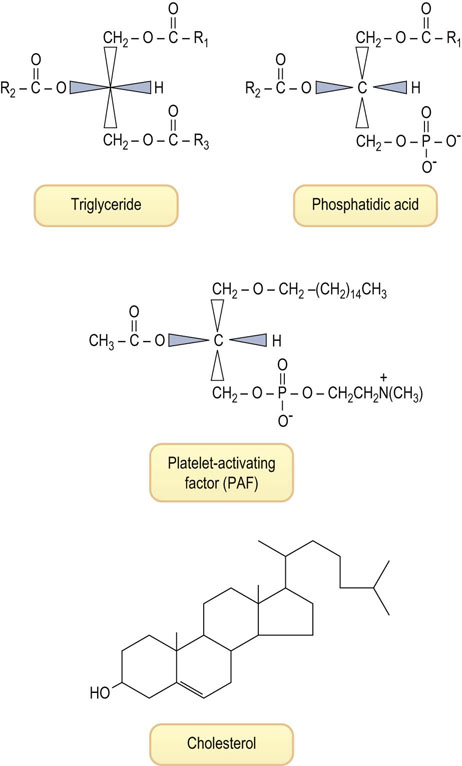

Fatty acids in plant and animal tissues are commonly esterified to glycerol, forming a triacylglycerol (triglyceride) (Fig. 3.6), either oils (liquid) or fats (solid). In humans, triglycerides are stored in solid form (fat) in adipose tissue. They are degraded to glycerol and fatty acids in response to hormonal signals, then released into plasma for metabolism in other tissues, primarily muscle and liver. The ester bond of triglycerides and other glycerolipids is also readily hydrolyzed ex vivo by a strong base, such as NaOH, forming glycerol and free fatty acids. This process is known as saponification; one of the products, the sodium salt of the fatty acid, is soap.

Fig. 3.6 Structure of four lipids with significantly different biological functions.

Triglycerides are storage fats. Phosphatidic acid is a metabolic precursor of both triglycerides and phospholipids (see Fig. 3.7). Platelet-activating factor, a mediator of inflammation, is an unusual phospholipid, with a lipid alcohol rather than an esterified lipid at the sn-1 position, an acetyl group at sn-2, and phosphorylcholine esterified at the sn-3 position. Cholesterol is less polar than phospholipids; the hydroxyl group tends to be on the membrane surface, while the polycyclic system intercalates between the fatty acid chains of phospholipids.

Glycerol itself does not have a chiral carbon, but the numbering is standardized using the stereochemical numbering (sn) system, which places the hydroxyl group of C-2 on the left; thus all glycerolipids are derived from L-glycerol (see Fig. 3.6). Triglycerides isolated from natural sources are not pure compounds, but mixtures of molecules with different fatty acid composition, e.g. 1-palmitoyl, 2-oleyl, 3-linoleoyl-L-glycerol, where the distribution and type of fatty acids vary from molecule to molecule.

Phospholipids

Phospholipids are the major lipids in biological membranes

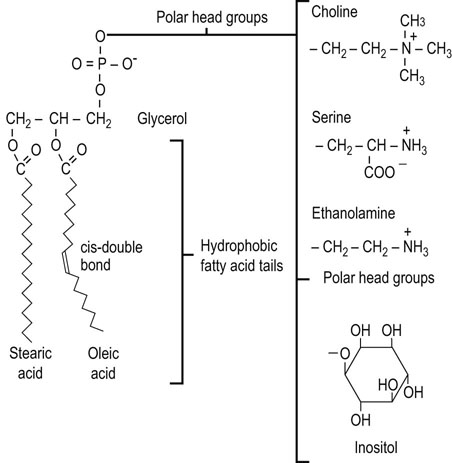

Phospholipids are polar lipids derived from phosphatidic acid (1,2-diacyl-glycerol-3-phosphate) (see Fig. 3.6). Like triglycerides, the glycerophospholipids contain a spectrum of fatty acids at the sn-1 and sn-2 position, but the sn-3 position is occupied by phosphate esterified to an amino compound. The phosphate acts as a bridging diester, linking the diacylglyceride to a polar, nitrogenous compound, most frequently choline, ethanolamine or serine (Fig. 3.7). Phosphatidylcholine (lecithin), for example, usually contains palmitic acid or stearic acid at its sn-1 position and an 18-carbon, unsaturated fatty acid (e.g. oleic, linoleic or linolenic) at its sn-2 position. Phosphatidylethanolamine (cephalin) usually has a longer-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid at the sn-2 position, such as arachidonic acid. These complex lipids contribute charge to the membrane: phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine are zwitterionic at physiologic pH and have no net charge, while phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol are anionic. A number of other phospholipid structures with special functions will be introduced in later chapters.

Fig. 3.7 Structure of the major phospholipids of animal cell membranes.

Phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylinositol (see also Chapter 28).

When dispersed in aqueous solution, phospholipids spontaneously form lamellar structures and, under suitable conditions, they organize into extended bilayer structures – not only lamellar structures but also closed vesicular structures termed liposomes. The liposome is a model for the structure of a biological membrane, a bilayer of polar lipids with the polar faces exposed to the aqueous environment and the fatty acid side chains buried in the oily, hydrophobic interior of the membrane. The liposomal surface membrane, like its component phospholipids, is a pliant, mobile and flexible structure at body temperature.

Biological membranes also contain another important amphipathic lipid, cholesterol, a flat, rigid hydrophobic molecule with a polar hydroxyl group (see Fig. 3.6). Cholesterol is found in all biomembranes and acts as a modulator of membrane fluidity. At lower temperatures it interferes with fatty acid chain associations and increases fluidity, but at higher temperatures it tends to limit disorder and decrease fluidity. Cholesterol–phospholipid mixtures have properties intermediate between the gel and liquid crystalline states of the pure phospholipids; they form stable but supple membrane structures.

Structure of biomembranes

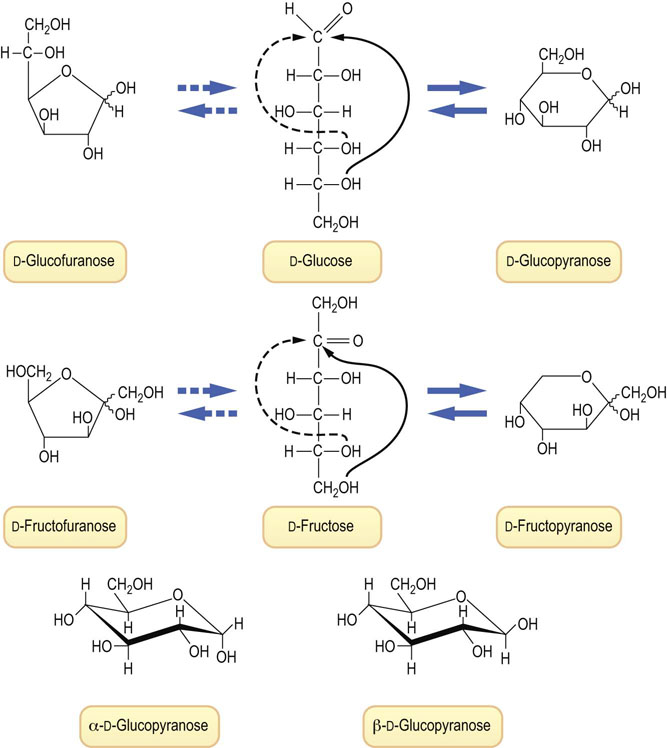

Eukaryotic cells have a plasma membrane, as well as a number of intracellular membranes that define compartments with specialized functions

Cellular and organelle membranes differ significantly in protein and lipid composition (Table 3.3). In addition to the major phospholipids described in Figure 3.7, other important membrane lipids include cardiolipin, sphingolipids (sphingomyelin and glycolipids), and cholesterol, which are described in detail in later chapters. Cardiolipin (diphosphatidyl glycerol) is a significant component of the mitochondrial inner membrane, while sphingomyelin, phosphatidylserine and cholesterol are enriched in the plasma membrane (see Table 3.3). Some lipids are distributed asymmetrically in the membrane, e.g. phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine are enriched on the inside, and phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin on the outside, of the red blood cell membrane. The protein to lipid ratio also differs among various biomembranes, ranging from about 80% (dry weight) lipid in the myelin sheath that insulates nerve cells, to about 20% lipid in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Lipids affect the structure of the membrane, the activity of membrane enzymes and transport systems, and membrane function in processes such as cellular recognition and signal transduction. Exposure of phosphatidylserine in the outer leaflet of the erythrocyte plasma membrane increases the cell's adherence to the vascular wall and is a signal for macrophage recognition and phagocytosis. Both of these recognition processes contribute to the natural process of red cell turnover in the spleen.

The fluid mosaic model

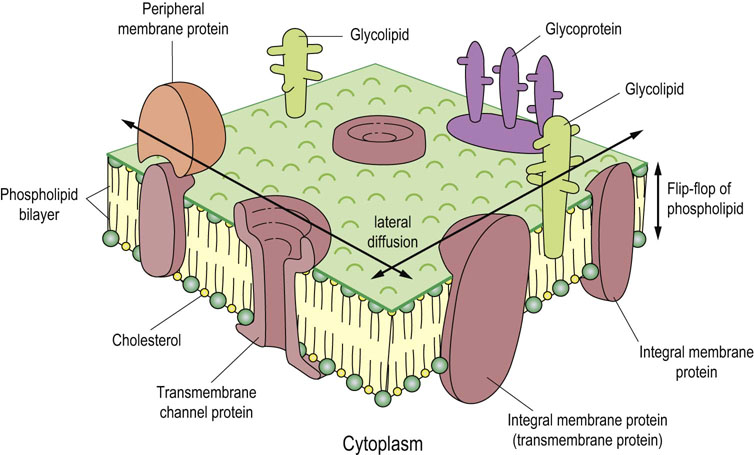

The fluid mosaic model portrays cell membranes as flexible lipid bilayers with embedded proteins

The generally accepted model of biomembrane structure is the fluid mosaic model proposed by Singer & Nicolson in 1972. This model represents the membrane as a fluid-like phospholipid bilayer into which other lipids and proteins are embedded (Fig. 3.8). As in liposomes, the polar head groups of the phospholipids are exposed on the external surfaces of the membrane, with the fatty acyl chains oriented to the inside of the membrane. Whereas membrane lipids and proteins easily move on the membrane surface (lateral diffusion), ‘flip-flop’ movement of lipids between the outer and inner bilayer leaflets rarely occurs without the aid of the membrane enzyme flippase.

Fig. 3.8 Fluid mosaic model of the plasma membrane.

In this model, proteins are embedded in a fluid phospholipid bilayer; some are on one surface (peripheral) and others span the membrane (transmembrane). Carbohydrates, covalently bound to some proteins and lipids, are not found on all subcellular membranes, e.g. mitochondrial membranes. On the plasma membrane, they are located almost exclusively on the outer surface of the cell (see Chapters 8 and 28).

Membrane proteins are classified as integral (intrinsic) or peripheral (extrinsic) membrane proteins. The former are embedded deeply in the lipid bilayer and some of them traverse the membrane several times (transmembrane proteins) and have both internal and external polypeptide segments that participate in regulatory processes. In contrast, peripheral membrane proteins are bound to membrane lipids and/or integral membrane proteins (see Fig. 3.8); they can be removed from the membrane by mild denaturing agents, such as urea, or mild detergent treatment without destroying the integrity of the membrane. In contrast, transmembrane proteins can be removed from the membrane only by treatments that dissolve membrane lipids and destroy the integrity of the membrane. Most of the transmembrane segments of integral membrane proteins form α-helices. They are composed primarily of amino acid residues with non-polar side chains – about 20 amino acid residues forming six to seven α-helical turns are enough to traverse a membrane of 5 nm (50 Å) thickness. The transmembrane domains interact with one another and with the hydrophobic tails of the lipid molecules, often forming complex structures, such as channels involved in ion transport processes (see Fig. 3.8 and Chapter 8).

Membranes maintain the structural integrity, cellular recognition and the transport functions of the cell

There is growing evidence that many membrane proteins have limited mobility and are anchored in place by attachment to cytoskeletal proteins. Membrane substructures, described as lipid rafts, also demarcate regions of membranes with specialized composition and function. Specific phospholipids are also enriched in regions of the membrane involved in endocytosis and junctions with adjacent cells. However, the fluidity is essential for membrane function and cell viability. For example, when bacteria are transferred to lower temperature, they respond by increasing the content of unsaturated fatty acids in membrane phospholipids, thereby maintaining membrane fluidity at low temperature. The membrane also mediates the transfer of information and molecules between the outside and inside of the cell, including cellular recognition, signal transduction processes and metabolite and ion transport; fluidity is essential for these functions. Overall, cell membranes, which are often viewed by microscopy as static, are well-organized, flexible and responsive structures. In fact, the microscope picture is like a high-speed stop-action photo of a sporting event; it may look peaceful and still but there's a lot of action going on.

Summary

Following the previous chapter on amino acids and proteins, this chapter provides a broader foundation for further studies in biochemistry, by introducing the basic structural features and physical and chemical properties of two major building blocks – carbohydrates and lipids.

Carbohydrates are polyhydroxyaldehydes and ketones; they exist primarily in cyclic forms, which are linked to one another by glycosidic bonds.

Carbohydrates are polyhydroxyaldehydes and ketones; they exist primarily in cyclic forms, which are linked to one another by glycosidic bonds.

Glucose is the only monosaccharides that exists in the body in free form.

Glucose is the only monosaccharides that exists in the body in free form.

Lactose and sucrose are important dietary disaccharides.

Lactose and sucrose are important dietary disaccharides.

Starch, cellulose and glycogen are important homoglucan polymers of glucose.

Starch, cellulose and glycogen are important homoglucan polymers of glucose.

Carbohydrates may be linked to proteins and lipids to form glycoconjugates, known as glycolipids and glycoproteins.

Carbohydrates may be linked to proteins and lipids to form glycoconjugates, known as glycolipids and glycoproteins.

Lipids are hydrophobic compounds, commonly containing fatty acids esterified to glycerol.

Lipids are hydrophobic compounds, commonly containing fatty acids esterified to glycerol.

Fatty acids are long chain alkanoic acids; unsaturated fatty acids contain one or more cis-double bonds, which decrease the melting (freezing) point of lipids.

Fatty acids are long chain alkanoic acids; unsaturated fatty acids contain one or more cis-double bonds, which decrease the melting (freezing) point of lipids.

Triglycerides (triacylglycerols) are the storage form of lipids in adipose tissue.

Triglycerides (triacylglycerols) are the storage form of lipids in adipose tissue.

Phospholipids are amphipathic lipids found in biological membranes; they contain a phosphodiester at C-3 of glycerol, linking a diglyceride to an amino compound, most frequently choline, ethanolamine or serine.

Phospholipids are amphipathic lipids found in biological membranes; they contain a phosphodiester at C-3 of glycerol, linking a diglyceride to an amino compound, most frequently choline, ethanolamine or serine.

The Fluid Mosaic Model describes the essential role of phospholipids, integral and membrane proteins and other lipids in the structure and function of biological membranes.

The Fluid Mosaic Model describes the essential role of phospholipids, integral and membrane proteins and other lipids in the structure and function of biological membranes.

Biological membranes compartmentalize cellular functions, and also mediate ion and metabolite transport, cellular recognition, signal transduction, and electrochemical processes involved in bioenergetics, nerve transmission and muscle contraction.

Biological membranes compartmentalize cellular functions, and also mediate ion and metabolite transport, cellular recognition, signal transduction, and electrochemical processes involved in bioenergetics, nerve transmission and muscle contraction.

Brand-Miller, J, Buyken, AE. The glycemic index issue. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012; 23:62–67.

Kar, S, Webel, R. Fish oil supplementation and coronary artery disease: does it help? Mo Med. 2012; 109:142–145.

Kusumi, A, Fujiwara, TK, Chadda, R, et al. Dynamic organizing principles of the plasma membrane that regulate signal transduction: commemorating the fortieth anniversary of Singer and Nicolson's fluid-mosaic model. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012; 28:215–250.

Shanmugam, T, Banerjee, R. Nanostructured self-assembled lipid materials for drug delivery and tissue engineering. Ther Deliv. 2011; 2:1485–1516.

Singer, SJ. Some early history of membrane molecular biology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004; 66:1–27.

Taubes, G. Good calories, bad calories: fats, carbs, and the controversial science of diet and health. New York: Anchor Books; 2008.

Zhang, YM, Rock, CO. Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008; 6:222–233.

History of membrane models. www1.umn.edu/ships/9-2/membrane.htm.

Soaps and saponification. www.kitchendoctor.com/articles/soap.html.