Lifespan

The early years (birth to adolescence)

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe some of the major developmental changes of infants, children and adolescents

describe some of the major developmental changes of infants, children and adolescents

» describe and critique the main theories of child development (Freud, Erikson, Piaget, Vygotsky)

» describe the main parenting styles and the influences on parenting

» describe how health professionals can adapt their practice when working with children at different ages and why this is important.

Introduction

Numerous theories and stage models have been proposed to describe the years of life from birth to adolescence (e.g. Erikson 1959, 1963, Freud 1917, Piaget 1952, 1954, 1962, Vygotsky 1978). Rather than learn these exhaustively, it is more important to understand the broad changes that can be observed across these years. These observable changes are important for health professionals to consider when working with children.

If we were to compare a two-year-old child with a 12-year-old child we would find enormous differences in almost everything about their life situation and their behaviour. Researchers and theorists observe the changes in activities and processes that occur as children develop and then describe and explain them in various ways. The patterns that are thought to occur between these monumental differences prompt researchers to develop and propose their theories, and when they observe patterns of change they propose stage models.

Clearly, there are many changes taking place as a child develops including physical, emotional, cognitive, social and psychological changes. All of these changes (‘developments’) occur within historical and cultural contexts that also influence development. While this may seem obvious, it was not that long ago that children were viewed as ‘little adults’ with the same cognitive, emotional and psychological abilities of adults, although without all the physical abilities (Aries 1962). Theorists have attempted to simplify the many details of changes throughout childhood and adolescence and to describe and explain how the changes take place. How these theorists have attempted to do this has varied because they have focused on different aspects of development.

In this chapter the focus is on the social and psychological aspects of development. The biological or physical development of children is a large field that, due to improvements in technology, is changing drastically and is therefore not discussed in this chapter. Students with particular interest in biological development might like to read Gottesman and Hanson's review article (2005) or Stiles' (2011) article that discusses the nature versus nurture debate and contemporary understandings of brain development.

When learning about developmental theories, avoid focusing solely on learning the theories; it is important to learn what the theorists were observing, reacting to and trying to describe or explain in their theories. To help with this, complete Classroom activity, Exercise 1.

Theorising about development

Having completed Classroom activity, Exercise 1 you are hopefully devising your own ideas and theories about what changes between these age groups. There are many ways to categorise theories: reductionistic, mediational, deterministic, essentialistic, causal, contextual, explanative or descriptive. A reductionistic theory, or reductionism, is a theory in which complex things are reduced or understood in terms of basic, simplified elements. For example, risk-taking behaviour among adolescents would be understood in terms of brain development in a reductionistic theory. Specifically, research has shown that the prefrontal cortex, which is considered to be the site of higher order cognitive functioning (i.e. the ability to think things through), is not yet fully developed in adolescents (Nelson & Guyer 2011).

A mediational theory is similar to reductionism but the key element in mediationism is that a behaviour or concept is mediated by something else. Using again the example of adolescent risk taking, a mediationist would say that brain development mediates risk-taking behaviour. Another example would be that an adolescent who is observed to be sleeping excessively, lacks interest in things they used to enjoy and spends a lot of time alone, might then be considered to be depressed, such that depression is then the mediator of these behaviours. This is an important distinction because it influences how we then go about intervening or what we do to change the behaviour. Do we change the sleeping, lack of interest, the time spent alone, or the depression?

Determinism is a theoretical approach in which the behaviour we observe is determined by past history: history of relationships (e.g. parental relationships in the case of Freud) or the history of consequences of behaviours (in the case of the behaviourism of B F Skinner, discussed later). Using the above examples, risk-taking behaviour may be explained in a deterministic way by referring to the history of consequences of behaviour, specifically that risk-taking behaviour has been positively reinforced, perhaps by getting attention. In contrast, essentialism views characteristics of groups (e.g. groups based on ethnicity, gender or age) as fixed or unchangeable, therefore risk taking by adolescents would be seen as an essential quality or characteristic among adolescents that is not changeable or influenced by context.

Causal and contextual theorising can be understood by contrasting them. Causal theories look to understand exactly what it is that causes what we observe while a contextual theory looks to understand the contexts in which those behaviours emerge. Again, for adolescent risk-taking behaviour, we could say that brain development causes risk taking or, contextually, that risk-taking behaviour is more likely to occur in groups of youth in unsupervised situations, for example.

Finally, explanative or descriptive theories can also be understood by contrasting them. They are similar to causal and contextual theorising, with an explanative theory similar to causal explanations and descriptive theories similar to contextual explanations. Using the depression example, we could refer to physiological deficits (e.g. low serotonin levels) to explain why an adolescent is depressed, or we could describe the contexts (especially social ones) in which depressive behaviours are more or less likely to occur, such as a lack of social support.

These theoretical approaches are not mutually exclusive and refer to different perspectives. Most theorists develop a view based on their own experiences and understandings in the same way you did in your first Classroom activity.

In this chapter we will refer to only one major difference between theories: whether changes that arise with age are explained by something within the person and their body (reductionism, mediationism, essentialism) or by forces outside of the person (contextualism or determinism). While many theorists today combine theories and do not rely exclusively on one or the other, this distinction will help to understand what the original theorists observed and were trying to explain.

Developmental theorists

Sigmund Freud is probably best known for his theories of psychoanalysis, but he also developed a theory of psychosexual development where he suggested that events that occurred in childhood determined behaviour patterns later in life (Freud 1917, also see Ch 1). In his clinical practice, Freud talked extensively with many hundreds of people and believed that there was a pattern in which particular events in people's early history contributed to the kind of person they would become. Freud believed that key events in childhood, such as learning to control eating, drinking and defecating (‘potty training’), learning about genitals and learning the rules about them (‘you will be punished if you touch them’), and learning about family control were the most important factors contributing to personality development. Specifically, Freud suggested five stages of psychosocial development: oral, anal, phallic, latency and genital, and that these stages corresponded with age, from birth to death.

Very simply put, Freud's experience with people suggested that these key events in childhood could lead to various peculiarities that he could detect when talking to people with serious clinical issues later in life. For example, Freud suggested that an adult who was very obsessive would have had trouble relating to ‘potty training’. If a person's obsessiveness became serious to a clinical extent then Freud's psychoanalysis would involve talking about obsessiveness as well as their early childhood history (including ‘potty training’) in therapy sessions.

Freud's theorising about adult behaviour, and that it was influenced by earlier childhood experiences, was actually quite revolutionary at that time. While the particulars of Freud's theories have not been supported with rigorous research, there is no doubt that Freud's theories have had a huge impact on Western society. Consider the popularised use of phrases like ‘anal retentive’ to label someone with obsessive qualities as described above, or even the use of ‘Freudian slip’ to describe verbal faux pas usually with sexual connotations. As we will see later, Erik Erikson also followed through with psychoanalytic theory but made the social dimension much larger than just the family circle.

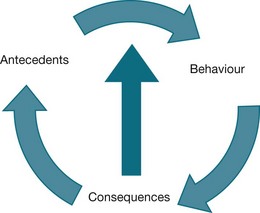

Burrhus Frederick Skinner (Fred) (1938, 1957, 1969) was a famous psychologist who mainly worked with animals. What he found fascinating was that changing minute details of an animal's environment or context (primarily its cage and the lights and switches in its cage) could control how the animal behaved. Skinner's theory, known as radical behaviourism, includes and elaborates on the basic concepts of antecedents (environments, contexts or stimuli), behaviour and consequences (what happens when a behaviour occurs). For example, rats that had to press a lever (behaviour) more than once to get food (consequences) when a light was on (antecedent or stimuli) would persist in pressing the lever longer when the food supply was stopped compared with those rats that received food on every press they made. Skinner was impressed that small and not easily observed changes in an animal's environment could make a large difference to its behaviour. Figure 2.1 illustrates how antecedents (or the environment/context) can influence behaviour that then leads to a consequence. These consequences contribute to both changing the environment, and changing behaviour in a circular pattern.

These observations led Skinner to advocate a theory that almost all behaviour was determined or controlled by factors in the environment rather than something that seemed to be ‘stored’ inside the body or that was ‘made into your personality’ (i.e. Freud's approach or mediationism). Skinner found that he could change the environment for his animals and watch their behaviour change subtly and in precise and predictable ways. This means that for any behaviour changes observed, we need to examine and describe the environment or context very carefully for the details that might be controlling that change or influencing the behaviours observed.

When applying this to humans, opinions are divided. One perspective is that such environmental factors do not apply to humans since we often complete actions although nothing can be found in the environment that might have changed. The other perspective says that we are not looking hard enough for these factors and that they might be observable but have occurred in the earlier history. For example, using the depression example above, we might not be able to see anything in the immediate environment that can explain the behaviour, so we say that the person is ‘depressed’, but it may be that past events contributed to the development of depression and that other factors then contribute to the maintenance of the behaviours we then call ‘depression’. According to Skinner, it would be possible (although often very difficult) to discover environmental changes that contribute to all human behaviour.

Skinner's work and observations with children and humans was mostly in relation to his own children. Perhaps his best known work with children was his development of an air crib for his own child. Skinner believed that a highly controlled environment would eliminate the mundane tasks of baby care such as keeping them warm and clean. In this way, parents could more effectively (and would have more time to) engage in other aspects of parenting such as playing and reading.

The original testing ground for Skinner's ideas about human behaviour involved looking at what controls our talking and use of language (Skinner 1957). While some researchers stated that no observable environmental changes could be seen when children start talking or using language Skinner's response was that they had not been looking in the right places. His ideas about environmental influences on language development and use were not well received (e.g. Chomsky 1959); however, newer versions of Skinner's ideas have been developed (Andresen 1990, Catania 1997, Hayes et al 1994).

Watch it on YouTube! See a short video about B F Skinner at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mm5FGrQEyBY>.

Jean Piaget (1952, 1954, 1962) was the most famous psychologist to consider how children think (cognition) and speak (language). In contrast to Skinner, he was not looking for environmental influences but was more interested in theoretical ideas of ‘information processing’ centres and ‘cognitive processes’ in the brain.

Like both Freud and Skinner, Piaget spent a lot of time observing behaviour, particularly by participating in thinking games with children, which contributed to the development of his theories. Regardless of the theory or issue under consideration, understanding children requires spending a lot of time systematically observing and participating with them.

Piaget observed that children of different ages think in very different ways from each other. What he saw was not a continuum of thinking from simple to complex but a set of stages (see Table 2.1 for a summary). For example, he observed that very young children did not seem to be able to think in terms of causality – that one event can cause another event. It was not that the children had different causes for the same event but, rather, they did not seem to be able to think in terms of causes at all. He surmised that causality was not thinkable below a certain age. Piaget observed that older children start to explain what caused events, naming events and objects that might have caused something else and trying to justify the way things occurred the way they did.

Table 2.1

PIAGET'S STAGES OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

| Approx. age | Stage | Description |

| Birth–2 years | Sensorimotor | An infant understands the world through senses (sensori) and movement (motor) |

| 2–7 years | Preoperational | A child begins to use words and symbols to make sense of the world |

| 7–11 years | Concrete operational | Reason is used to logically make sense of concrete events in the world and to classify objects |

| 11–15 years through adulthood | Formal operational | Reasoning becomes more abstract, logical, and idealistic |

These observations led Piaget to argue for a stage model in which children learn more and more complex ways of thinking whereby they are not able to think in one level until they have achieved the level before that in the sequence. He also argued that once a certain stage of thinking was reached this had consequences for what the child could accomplish and would lead to new ways of communicating or thinking. For example, once a child could think in terms of causality, then they could think in terms of making excuses and getting themselves out of trouble. ‘I only did it because Giles told me to’ requires a level of causal thinking before it can be thought at all.

While Piaget described a number of stages and substages of cognitive development, we focus here on the broader overall changes he described and not the complex details of these stages. Table 2.1 shows the basic stages, the approximate ages associated with those stages and a brief description. (You may like to refer to a developmental psychology textbook such as Peterson 2009 for more detailed versions.) The first broad stage Piaget called sensorimotor because children at this age think, as it were, through their senses and their physical movements. Something like, ‘If I can’t see it, taste it or touch it then it does not exist and I cannot think it!’. Children explore and learn only what they physically interact with through their senses. At this stage, children cannot ‘think’ about a cat being somewhere else if it is not in front of them, or they are not touching it, or they do not have its tail in their mouth.

At the preoperational stage children begin to attribute words to the things around them and use those words, but this stage is ‘pre’ operational, with ‘operational’ referring to ‘logic’. This is not just being able to reliably say a sound when something is there, as even very young children can say ‘caaa’ when a cat is presented. It is the beginning of ‘representing’ things by words so that the child can also say ‘caaa’ when the cat's box is there or ‘caaa’ when a parent gets the cat's food out of the cupboard.

One interesting thing Piaget found for children at an early age was that if, say, a cat was hidden under a blanket, the child would act as if the cat had gone for good and was no longer in existence – ‘out of sight, out of mind’. However, as a child developed, they began to look under the blanket for the cat – that is, the object has permanence even if it cannot be seen. Piaget called this developmental aspect object permanence. Around the same time children would also begin using the word ‘caaa’ in the preoperational sense explained above. These were the sorts of real changes Piaget noted from his extensive observations and that he was trying to capture in his theories and stages.

From this preoperational stage of beginning to ‘see things that are not immediately there’ and being able to talk about things not in front of them, children then develop the ability to reason and to classify and code. In the concrete operational stage children begin to use logical forms of reasoning (note that there are several main systems of logic, not just one) and to classify things into groups based on characteristics. However, these processes are only for concrete things and events, such as ‘my trucks’ or ‘Gracie got an ice cream, why can’t I have one?’ rather than anything more abstract.

The ability to complete complex tasks or abstract ways of thinking arise in the formal operational stage in which abstract thinking is possible and can be used in reasoning and logical processes. Piaget, as well as other child development researchers, devised a number of tests to determine development at this stage and it is not so much the resolution to these tests that is important but, rather, how children come up with the resolution. For example, to combine a yellow solution with a blue solution to create a green solution, a child in the concrete operational stage may, through trial and error, mix the solutions together. However, a child in the formal operational stage may use logic to come up with the answer before using trial and error.

Typically, the ages associated with these stages are: sensorimotor 0–2 years, preoperational 2–7 years, concrete operational 7–11 years and formal operational 11–adulthood. However, these have been found to vary depending upon the education system and the context of the child and, indeed, not everyone may reach every stage. What is important is that vast changes are taking place in the very way children think and talk about things through these ages and this is what Piaget observed through intense observations and then tried to put into a formal theoretical structure. For us, whether the latter is exactly correct or not is not so important and learning the real changes is what matters most.

Piaget consistently focused his observations and theorising on individual children and the ways that they were thinking and talking about events. He treated the stages he saw as changes in internal information processing or the ‘structure’ of cognition. Later theorists spent more time in those same situations but focused on how the children's social interactions influenced the ‘individual cognitive’ abilities (Bruner 1973). As we will see Vygotsky, Bruner and others showed there was a ‘social scaffold’ that supported ‘cognitive’ development.

Lev Vygotsky (1978), a Russian theorist in the early 1900s, was the first of a series of theorists who, like Skinner, explored the environmental or external factors that control the changes that appeared to occur ‘within’ the child. However, it is interesting that Vygotsky was not familiar with Skinner's work even though it came earlier and that Vygotsky's work was not known in English-speaking countries until much later.

The important contribution that Vygotsky made to our understanding of human development was that the ‘hidden’ environmental factors that bring about developmental changes but that are hard to see are social ones. That is, he suggested that the internal cognitive changes and stages depend upon social relationships – hence, his theory is known as a sociocultural theory or a constructivist theory. The idea was that the ‘mind’ and the ‘cognitive processes’ were in fact controlled by social factors that were very subtle and not easy to observe unless you observed closely and over a long period. According to this line of thinking, the mind is not inside the body but, rather, it is a name for processes of social interaction that cannot be directly seen and that occur over time.

Watch it on YouTube! You can hear a brief description of Vygotsky's theory:

Vygotsky's developmental theory: An introduction at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hx84h-i3w8U&feature=related>.

Vygotsky did not theorise about children ‘having’ or ‘possessing’ skills (whether physical or cognitive), nor did he talk or theorise about children learning to think in ‘stages’ set apart from their social interactions, conversations, modelling and other social experiences. Instead, Vygotsky wrote about how children think in the context of development, especially in the social context. This idea of considering the social influences on what seem to be purely ‘internal’ thinking events has been developed in various ways. For example, some researchers have looked for patterns in social relationship thinking that facilitate thinking about causality or mathematics. Researchers have also looked at how social support, encouragement or training facilitates cognitive thinking. Psychologists still have some way to go in describing the finer details of these approaches (see Guerin 2001, 2004).

Vygotsky's ideas often become clearer to people in the context of his notion of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Rather than conceiving of children reaching new stages of cognition as a result of changes taking place inside them somewhere, Vygotsky proposed that the changes occur within interactions with other people, through processes of imitation, cooperation, support, guidance and enrichment. If children act totally alone then there are many things they cannot do and cannot easily learn to do – this is the lower limit to the ZPD. If children act with other people in concert, or with support, they can do a lot of things by accepting the other person's responsibility and help – this is the upper limit of the ZPD.

Therefore, there are skills children learn through others and, perhaps, when they are not present, they can no longer do those skills. For example, a child may learn how to turn on the computer and open the program to play their favourite game when she is with her older brother and in response to his prompting, but later she may not be able to recall all the necessary steps to play the game when he is not there. Eventually, as people get older, they can do more without other people's direct involvement. But this Vygotskian way of thinking means that skills are not absolute, all-or-none possessions that once gained cannot be lost. We lose skills as well as develop them and we have a variable set of skills that we sometimes have and sometimes do not have.

We can apply these ideas to children and physical activity, and how behaviour can change depending on the people the children are with and the contexts. For example, learning to ride a bike may develop with help from parents or older siblings. Riding without training wheels may start with someone holding onto the seat and letting go when the rider is not aware, but this skill may depend on the presence of others until the skill refines. Eventually, riding a bike may develop into very complex skills such as riding with friends at a bike park. But, after not riding a bike for a long time, a child would not be able to go straight back to the bike park and perform all the tricks again. Even though we may be able to ride a bike even after a long period of not riding one, some of the finer skills would require practise to re-learn.

The Vygotskian answer to the question of ‘What cognitive stage is that child up to?’ is: ‘Well, it depends on who that child has been interacting with and has been supported by. By themselves they might not be showing too many thinking skills, but when interacting with a parent or a favourite carer or teacher they might show remarkable cognitive prowess’. In essence, the answer is in the environment (social environment), not inside the child.

Some recent approaches to describing human development have set similar ideas within multidimensional approaches. This means that human biology, social factors, psychological factors, spirituality, structural issues and culture are all considered when trying to understand human development (Harms 2005). Some call these approaches biopsychosocial models, ecological approaches or contextual approaches. What they all try to encapsulate is that human development is obviously made up of lots of changes, that most of the determinants of these changes are difficult to observe easily and that the changes all involve the body, the environment and the social world. Psychologists do not yet know how these elements might all fit together, but these approaches suggest that all of these elements are necessary ingredients.

Overall development

Much of the theorising and research discussed in this chapter revolves around the development of thinking and social relationships. Others have characterised the whole development sequence through the use of stages. Sometimes this is called lifespan development (e.g. Santrock 2008). In this regard it is worth looking at the model of Erik Erikson, since he also proposed a very different and interesting stage theory of development.

Instead of proposing a series of stages that all people purportedly travel through, Erikson suggested a series of life conflicts, tasks or issues that are dealt with at different ages. These conflicts can result in good outcomes or poor outcomes depending upon the environment and the previous history of the individual. He proposed eight stages from infancy through to late adulthood (60 years old and beyond). Only the first five that are relevant to childhood development are discussed in this chapter; however, all of the stages are included in Table 2.2 because they will be considered in Chapter 3.

Table 2.2

ERIKSON'S DEVELOPMENTAL STAGES

| Erikson's stages | Developmental stage (age) |

| Trust versus mistrust | Infancy (first year) |

| Autonomy versus shame and doubt | Late infancy (years 1–3) |

| Initiative versus guilt | Early childhood (years 3–5) |

| Industry versus inferiority | Middle and late childhood (years 6 to puberty) |

| Identity versus identity confusion | Adolescence (years 10–20) |

| Intimacy versus isolation | Early adulthood (20s, 30s) |

| Generativity versus stagnation | Middle adulthood (40s, 50s) |

| Integrity versus despair | Late adulthood (60s onwards) |

Notice that this sequence includes development relevant to family social relationships, cognitive development and friendship. This was shown through the ideas of Vygotsky and others, where being able to function successfully in social relationships is a prerequisite for any ‘cognitive’ or ‘mind’ development. Therefore, working in normal relations will facilitate the ZPD and lead to improvement in all theories that have been discussed in this chapter.

During infancy, according to Erikson, the main hurdle is to develop a basic sense of trust in people and the world, rather than to develop a general mistrust. He proposed that an optimal social environment or context would result in a person who will generally trust that their needs will be met and have confidence in themselves and the world they are in. In a social environment where an infant's needs are not met, then Erikson believed this child would develop to generally mistrust the world and the people around them and therefore not be willing to risk events with other people. This would mean that opportunities would be lost. It is not so much mistrusting that is the problem but the opportunities for further development that get restricted if a basic trust in people and the world is not present.

Later in infancy and toddlerhood, the task is for the child to begin acting independently and to be less reliant upon parents and others. This was characterised as a conflict between autonomy and shame or doubt, but the same thing can apply without those latter terms. A child who is too dependent might not develop self-doubt or shame, especially considering they are aged under three years at this point, but they still have not managed an important skill in the context of their future development; shame and doubt could develop as a consequence.

Similar comments apply to the stage in early childhood. The basic idea is that the child needs to have a context in which they can show initiative and start events by themselves. They need to get up in the morning, sometimes get food without asking or being told to, and need to initiate games and peer interaction. If this does not occur for the child, once again, numerous cognitive and social opportunities for further skill development will be missed. Though, as mentioned, we do not necessarily have to agree that the lack of initiative necessarily leads to guilt. A child might not even be aware or be able to verbalise what is going on if this contextual skill development is missed. But the basic process is still important and necessary for further development.

Erikson's fourth life task is the development of ‘industry’, meaning that things get done. The child is able to execute tasks. This includes all the cognitive, logical, social and other skills discussed in this chapter. Inability to do this is characterised as inferiority but, once again, we might temper this and say that children might grow up with different ideas of what they can and cannot do. Certainly in some circumstances this would lead to what is called a sense of inferiority but not in all cases. Some might accept (unwittingly) that this is just how things are and others might feel ‘safer’ not attempting everything.

Finally, adolescence is said to be characterised by the development of a sense of identity or a sense of identity confusion. This can have a couple of meanings. First, it can refer to the ways we learn to talk about ourselves to ourselves and others and what talk we can get away with. Are others agreeable with how we talk about who we think we are and what we can do? Second, it can mean a sense of taking on more adult-like roles and responsibilities and whether we do a good job – what special and unique things can I do and take responsibility for? Basically, how we talk about ourselves is related to whether we are good at doing these jobs and taking on responsibility.

Summary of developmental theories

Key theorists have all spent extensive time observing behaviour or interacting with people; their theories were attempts to describe systematically the changes in development that they had observed, however biased or selective we might now view these to be. Some theorists emphasised that changes resulted from environmental changes, some from internal cognitive changes or biology and others tried to meld these two perspectives together. Perhaps the most useful approaches consider social influences as the key in understanding developmental changes because these are things that are observable or can change.

Major influences on developmental changes

In this section, we focus on some of the main influences on child development. There are obvious key events and people that influence children as they grow older. Most children in developed countries are given a long and complex education of some sort or another and this must impact on how they change. Children are exposed to family, friends and communities, and this exposure also impacts on how children change. There is also a huge array of media events that impact on children from television to computers, and from MP3 players to mobile phones.

Parents, family and community

It is often assumed that parents comprise a major determinant of children's development. Freud, Skinner and ecological approaches would all suggest that parents are a major influence in the child's environment and surely influence development. However, there are two limitations to the view that parents are a major determinant of children's development. First, parent-centred life for children is not universal around the world or even within countries. For many children, parents are busy working and children spend more time with an extended family or with others in their wider community. The image in Western, English-speaking communities is that families comprise one or two parents and their children in a house (i.e. the ‘nuclear’ family) who make visits to other houses that contain relatives and family friends. However, many children spend a lot of time – or even live with – their grandparents or uncles and aunts, or even with strangers. In China, in fact, children as young as two from affluent families may board in childcare centres and only see their parents on the weekends (Brassard & Chen 2005). Most research, though, has focused on families in Western societies and the influence of parents. Whatever the findings, parents may have different impacts in the hugely diverse range of family and community settings.

Second, researchers are not unanimous in declaring parents a major influence (Collins et al 2000, Harris 1995). Research of this nature is very difficult to arrange so that clear answers are produced. We have to decide whether the evidence is that parents are not greatly influential over children or whether the research has not been done properly because of the difficulties in setting up such research. Showing whether a behaviour is primarily due to genetics or to the environment is not a simple dichotomous question and no methodology is straightforward. Let us outline both sides of the story.

Harris (1995) considered several lines of research to explore the case for parents having little or no influence on their children. For example, while twin studies show that twins reared apart are more different than those raised together (suggesting that the environmental factors such as parents are highly influential) it was pointed out that even identical twins reared together in the same home with the same parents are very different in many ways. News stories have focused on a few examples of twins amazingly liking or doing similar things that are unusual despite being reared apart, such as both wearing rubber bands on their wrists or reading magazines from back to front (Dowling 2004), but these cases are not common over the whole population. This suggests that environmental factors other than the parents are playing a major role in development. Harris argued that adolescent groups and friendships play a greater role in developmental changes, rather than the home environment of the parents.

Collins et al (2000) examined the quality of the research being cited. They suggested a greater role for parents than Harris (1995) but also argued that many of the research methods were flawed or had limitations. They worked within the types of ecological or biopsychosocial theories described earlier and identified roles for genetics, parents and peers.

Collins et al (2000) also pointed out that even if you show influences from peers, it takes a special research methodology to determine whether that peer influence was moderated by the parents in the first place. It could be that a child is influenced by peers at school but that the context for being influenced in such a way was produced by the parents (Hayes et al 2004). Similarly, Bamberg et al (2001) suggest that parents influence this selection of peers because adolescents who have parents who frequently smoke or drink alcohol are more likely to choose to associate with peers who display these behaviours. This is saying that there can still be a parental influence on children even if the children seem to be influenced by their friends, since the parents might facilitate or inhibit the children's receptivity to peer influence, or at least to certain types of peers. A child could be influenced by a peer at school, but the parental influence on friend selection might have encouraged their child to make friends with just that sort of peer. For example, a parent may tell a child, ‘Only play with the nice boys when you get to school. Okay, Vincent?’, or they may influence friend selection through their own networks such as by only inviting children of parents that they know over to play. This is shown more in the following sections.

In summary, children's development is influenced by parents, families, peers and communities but there is no single model for how much these play a role in all instances. As mentioned, communities and families are highly diverse, with some built on the nuclear family model and others with extended families and communities. Also, the many pathways through which parents, families and peers influence development are not clear and different contexts will produce different mixes of these. A single model of parental influence on children should perhaps not be expected.

Influence from friends and peers

In relation to peer influence, research methods can be limited in their ability to provide clear answers to what seem easy questions such as, how do peers influence children? As suggested earlier, peers are a strong force, though not as influential as some have argued, and it is often difficult to tease out parental influence on choosing peers in the first place (Collins et al 2000, Harris 1995, Hayes et al 2004).

But how might peer influence actually function in reality? A common view is that ‘peer pressure’ forces teenagers belonging to a group to do everything done by that group. People commonly say that teenagers all dress the same and do the same things because of peer pressure (a causal theory). A child gets into a group and then that group pressures them to do the same things such as wear the same clothes, listen to the same music, or imbibe the same alcohol, drugs and tobacco. However, this view may be too simplistic.

As discussed earlier the way people view the influences from family, friends and communities is changing and new ways of thinking about these issues are emerging. Bauman and Ennett have explored the role of adolescent groups on smoking, drinking and drug use (Bauman & Ennett 1994, Chuang et al 2009, Ennett & Bauman 1993, 1994, Ennett et al 1994, Fisher & Bauman 1988) and others have shown similar results with other behaviours (Billy & Udry 1985, Kandel 1978). These challenge the common view that groups of peers pressure children into behaviours they would not do otherwise, but, more importantly, they expand our notions and see ‘peer pressure’ as one social strategy among others. Peer influence is bi-directional (i.e. peers influence each other) and these influences can be both positive and negative (Sumter et al 2009). Additionally, as adolescents get older, resistance to negative peer influence increases and girls have been found to be more resistant to peer influence than boys (Sumter et al 2009).

As suggested earlier when discussing parental influence, it is not that children become involved in groups that then pressure them in various ways but, rather, for a multitude of reasons (including parental influence) children participate in certain groups, get expelled from certain groups or are selected into groups. Participation in groups is very complex and requires further research, but it is also important not to oversimplify this complexity. Billy and Udry (1985) found a similar thing for sexual behaviours. People who were non-virgins tended to hang out with people who were also non-virgins and virgins tended to hang out with virgins, but their data showed that this does not mean that there is peer pressure to do what others in the group are doing (or not abstaining from). Rather, their longitudinal study found that when someone had sex for the first time they tended to join new groups of non-virgins. Therefore, it is once again the selection into and out of groups that make groups similar or homogeneous rather than pressure within a group for all the members to be similar.

There are four other points to consider in relation to this research. The first is that peer pressure is not necessarily negative. Ennett and Bauman (1993) found that most of their cliques tended to consist entirely of non-smokers. So, in this case, there is good argument that if there is peer pressure, it is beneficial in potentially reducing the number of smokers rather than acting to increase smoking. Second, research suggests that people overestimate the similarity among group members, especially groups other than their own. This is clearly part of the illusion that it is peer pressure that contributes to the behaviour of adolescents. Peers within groups are quite aware of small differences within their group, and outsiders (e.g. parents) may not be able to identify those differences. Third, it is in parents' best interests to portray their own children as innocent victims of peer pressure, rather than believe that their children actually self-select into groups. The final consideration is that far from adolescent smokers being compliant in a group of peers that pressure them to smoke, other research found that girls who smoked were more self-confident and socially skilled than non-smoking peers (Michell & Amos 1997) and therefore unlikely to be easily peer pressured into smoking.

From these strands of research you may find that the links between parents, peers and influences on a child's development are very convoluted and complex and simple generalisations are not useful.

Education and schooling

In this section, we consider the influence of education on children's development. First, we have seen that peers at school are one major influence on development, whatever the causal pathways. When children do not go to school then there might be less influence of non-related peers. Schooling in Western societies creates many opportunities for peer social influence and pressure that do not exist in other groups around the world.

Second, education is not the same as schooling and in many communities children are sometimes educated out of school more than in school. For example, families educate their children explicitly (even if informally) in and around the home and social environment. This might be in activities that are useful for the community and ritual activities, as well as reading, writing and arithmetic. Some families do not attempt to educate children except in a moral sense; they leave education to the schools. And in some cases, even moral education is left to the schools (as in religious or other private schools that may teach ‘values’). Some parents, however, explicitly teach children, sometimes formally, as in home schooling.

The third point is that researchers who have studied children's cognitive or thinking development outside of the school setting may not show the full impact of the explicit education of children in how to think, count, etc. Many children, by the age of three or four years, are engaged in an education program aimed at facilitating or developing their abilities. Clearly, what is taught in kindergartens and schools will be a major influence on children. Discovering how children develop requires a perusal of formal schooling, as well as any peer or informal family education.

Stages, ages and milestones of development

Developmental milestones are a useful guide to parents, caregivers, educators and health professionals to gauge a child's development. Milestones can indicate whether a child is developing within a ‘normal’ range, although it is also important to acknowledge that deviations from these milestones do not necessarily mean there is anything wrong. Take, for example, talking. While talking among toddlers varies greatly, it would be important to explore why a toddler might not be talking by 24 months and to rule out physical causes such as hearing difficulties. For example, a toddler in a large family may not be talking because others in the family do all the talking, or they might be able to talk but do not do this out loud because they normally do not have a chance. There are many well-developed milestone charts that are used by parents and health professionals to help understand children's development. Some websites of developmental milestones are presented at the end of this chapter. You may find different charts or ways of presenting milestones more useful than others. It is worthwhile to explore different milestone charts and approaches to see their differences and to determine which ones work for you or the parents who you might be working with.

Conclusion

In this chapter several theories of human development have been explored, with an emphasis on understanding the key features of these theories. Theorists have attempted to explain the behaviours they observed in children and adolescents that were inexplicable or interesting.

Some of the main influences on development have been discussed and the relative weights of those influences were critically examined. Critical thinking has been encouraged about influences that are often taken for granted such as the influence of peers or parents on children's development. We also discussed the diversity of parenting practices and the complexities of schooling and education.

Christensen, P., Mikkelsen, M.R. Jumping off and being careful: children's strategies of risk management in everyday life. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008; 30:112–130.

Coyne, I., Gallagher, P. Participation in communication and decision-making: children and young people's experiences in a hospital setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011; 20(15–16):2334–2343.

Hawthorne, K., Bennert, K., Lowes, L., et al. The experiences of children and their parents in paediatric diabetes services should inform the development of communication skills for healthcare staff (the DEPICTED Study). Diabetic Medicine. 2011; 28(9):1103–1108.

Morrow, A.M., Hayen, A., Quine, S., et al. A comparison of doctors’, parents’ and children's reports of health states and health-related quality of life in children with chronic conditions. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2011; 38(2):186–195.

Wagmiller, R.L., Lennon, M., Kuang, L. Parental health and children's economic well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008; 49:37–55.

There are a number of useful sources of information regarding childhood developmental milestones. Below is a list of just a few of these. Remember, milestone charts are useful as an indicator of development, but many factors contribute to when these milestones are met. If a child has not reached a milestone this should be seen as an opportunity to rule out possible problems while also keeping in mind that variation in development is normal.

Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit at the University of Otago

This site provides information conducted in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Research Unit including one of the largest ever longitudinal studies on human development, which has been going for nearly 40 years.

The Health Insite website from the Australian Government is a useful website for accessing information about a wide range of health issues. Search for ‘developmental milestones’ to access topic pages relevant to baby and child development.

Ministry of Health (New Zealand) Child Health section

www.health.govt.nz/our-work/life-stages/child-health

The child health section of the New Zealand Ministry of Health website provides useful information on a range of services offered in New Zealand relevant to child health as well as a link to publications.

The Raising Children Network is a web resource for parents that is supported by the Australian Government and provides a wide range of useful materials and information about raising children and links to services and support.

The Community Child Health Service for Queensland Health

www.health.qld.gov.au/cchs/growth_approp.asp

This website provides a number of useful milestone guides in various languages.

US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones

The US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website includes an interactive milestones chart for parents as well as other developmental information for a range of age groups from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

References

Andresen, J.T. Skinner and Chomsky thirty years later. Historiographia Linguistica. 1990; 17:145–165.

Aries, P. Centuries of childhood. New York: Vintage Books; 1962.

Azize, P.M., Humphreys, A., Cattani, A. The impact of language on the expression and assessment of pain in children. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2011; 27:235–243.

Bamberg, J., Toumbourou, J.W., Blyth, A., et al. Change for the best: family changes for parents coping with youth substance abuse. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. 2001; 22(4):189–198.

Bauman, K.E., Ennett, S.T. Peer influence on adolescent drug use. American Psychologist. 1994; 49:820–822.

Baumrind, D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991; 11(1):56–95.

Bibace, R., Walsh, M.E. Development of children's concepts of illness. Pediatrics. 1980; 66:912–917.

Billy, J.O.G., Udry, J.R. Patterns of adolescent friendship and effects on sexual behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1985; 48:27–41.

Brassard, M.R., Chen, S. The boarding of upper middle class toddlers in China. Psychology in the Schools. 2005; 42(3):297–304.

Bruner, J.S. Beyond the information given: studies in the psychology of knowing. New York: Norton; 1973.

Catania, A.C. An orderly arrangement of well-known facts: retrospective review of B F Skinner's verbal behavior. Contemporary Psychology. 1997; 42:967–970.

Chomsky, N. A review of B F Skinner's verbal behavior. Language. 1959; 35:26–58.

Chuang, YC., Ennett, S.T., Bauman, K.E., et al. Relationships of adolescents’ perceptions of parental and peer behaviors with cigarette and alcohol use in different neighborhood contexts. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009; 38:1388–1398.

Collins, W.A., Maccoby, E.E., Steinberg, L., et al. Contemporary research on parenting: the case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist. 2000; 55:218–232.

Darling, N., Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993; 113(3):487–496.

De Vries, H., Engels, R., Kremers, S., et al. Parents’ and friends’ smoking status as predictors of smoking onset: findings from six European countries. Health Education and Research. 2003; 18(5):627–636.

Dowling, J.E. The great brain debate. Washington DC: Joseph Henry Place; 2004.

East, P.L., Rook, K.S. Compensatory patterns of support among children's peer relationships: a test using school friends, nonschool friends and siblings. Developmental Psychology. 1992; 28:163–172.

Ennett, S.T., Bauman, K.E. Peer group structure and adolescent cigarette smoking: a social network analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993; 34:226–236.

Ennett, S.T., Bauman, K.E. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: the case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994; 67:653–663.

Ennett, S.T., Bauman, K.E., Koch, G.G. Variability in cigarette smoking within and between adolescent friendship cliques. Addictive Behaviors. 1994; 19:295–305.

Erikson, E.H. Identity and the lifecycle – selected papers 1959. New York: International University Press; 1959.

Erikson, E.H. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1963.

Fisher, L.A., Bauman, K.E. Influence and selection in the friend-adolescent relationship: findings from studies of adolescent smoking and drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988; 18:289–314.

Freud, S. A general introduction to psychoanalysis. New York: Washington Square Press; 1917.

Goodenough, B., Thomas, W., Champion, G.D., et al. Unravelling age effects and sex differences in needle pain: ratings of sensory intensity and unpleasantness of venipuncture pain by children and their parents. Pain. 1999; 80(1–2):179–190.

Gottesman, I.I., Hanson, D.R. Human development: biological and genetic processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005; 56:263–286.

Guerin, B. Individuals as social relationships: 18 ways that acting alone can be thought of as social behavior. Review of General Psychology. 2001; 5:406–428.

Guerin, B. Handbook for analyzing the social strategies of everyday life. Reno: Context Press; 2004.

Harms, L. Understanding human development: a multidimensional approach. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Harris, J.R. Where is the child's environment? A group socialization theory of development. Psychological Review. 1995; 102:458–489.

Hayes, L., Smart, D., Toumbourou, J.W., et al. Parenting influences on adolescent alcohol use, Research report No. 10. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2004.

Hayes S.C., Hayes L.J., Sato M., et al, eds. Behavior analysis of language and cognition. Reno: Context Press, 1994.

Kandel, D.B. Homophily, selection and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology. 1978; 84:427–436.

Kortesluoma, R.L., Punamaki, R.L., Nikkonen, M. Hospitalized children drawing their pain: the contents and cognitive and emotional. Journal of Child Health Care. 2008; 12:284–300.

Lin, C.Y.C., Fu, V.R. A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese and Caucasian-American parents. Child Development. 1990; 61:429–433.

Lin, H.P., Mu, P.F., Lee, Y.J. Mothers’ experience supporting life adjustment in children with T1DM. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2008; 30:96–110.

Michell, L., Amos, A. Girls, pecking order and smoking. Social Science and Medicine. 1997; 44:1861–1869.

Nelson, E.E., Guyer, A.E. The development of the ventral prefrontal cortex and social flexibility. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011; 1:233–245.

Olson, L.M., Radecki, L., Frintner, M.P., et al. At what age can children report dependably on their asthma health status? Pediatrics. 2007; 119(1):e93–e102.

Peterson, C. Looking forward through the lifespan, fifth ed. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education; 2009.

Piaget, J. The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook, Translation). New York: International Universities Press; 1952.

Piaget, J. The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books; 1954.

Piaget, J. Play, dreams and imitation. New York: WW Norton; 1962.

Piaget, J. The child's conception of the world. New York: Routledge; 1992.

Santrock, J.W. Lifespan development, eleventh ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

Skinner, B.F. The behavior of organisms. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1938.

Skinner, B.F. Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957.

Skinner, B.F. Contingencies of reinforcement: a theoretical analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1969.

Stiles, J. Brain development and the nature versus nurture debate. Progress in Brain Research. 2011; 189:3–22.

Sumter, S.R., Bokhorst, C.L., Steinberg, L., Westenberg, P.M. The developmental pattern of resistance to peer influence in adolescence: Will the teenager ever be able to resist? Journal of Adolescence. 2009; 32:1009–1021.

Ungar, M.T. The myth of peer pressure. Adolescence. 2000; 35:167–180.

Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in society: the development of higher psychological functions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1978.

Wyatt-Brown, B. The mask of obedience: male slave psychology in the old South. American Historical Review. 1988; 93:1228–1252.

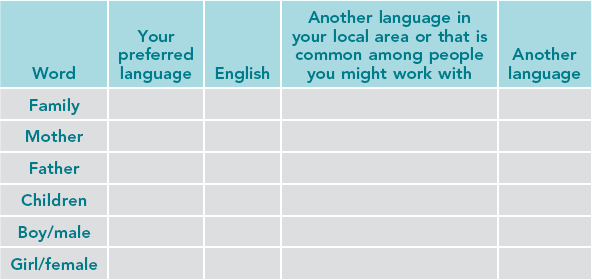

ori words are often used interchangeably with English words. Consider words such as whanau (family) or tamariki (children).

ori words are often used interchangeably with English words. Consider words such as whanau (family) or tamariki (children).