Lifespan

Middle and later years (adulthood to ageing)

The material in this chapter will help you to:

describe the major developmental theories relevant from early to late adulthood

describe the major developmental theories relevant from early to late adulthood

discuss the diversity of partner selection, marriage and family structures

discuss the diversity of partner selection, marriage and family structures

discuss the complexities of employment, career and lifestyle during adulthood and the implications of these for health.

discuss the complexities of employment, career and lifestyle during adulthood and the implications of these for health.

Introduction

In this chapter we examine theories of adulthood and ageing in the context of health psychology. The period from emerging adulthood to end-of-life spans a huge part of human experience, with a wide range of events taking place. While it is not possible to review all the health psychology material relevant to adulthood in one chapter, a range of issues relevant to adulthood will be covered and this will, perhaps, inspire you to seek out more information on related topics. The purpose is to give you a developmental perspective when confronting issues in your healthcare practice.

A common practice among researchers and theorists is to partition adulthood into stages or milestones, even though these might not apply universally. The broad stages of early, middle and late adulthood show major differences in physical, social, emotional and cognitive abilities, as well as circumstances. Theorists have observed quantum changes in how people behave across these periods. Additionally, theorists have more recently been discussing the transition from adolescence to adulthood, referring to this stage as emerging adulthood (Arnett 2000, Arnett et al 2011, Arnett & Tanner 2006). However, a drastic change in, for example, economic circumstances in contemporary society, can result in changes to adult circumstances. For example, young adults may find they live at home with their parents longer than they have in the past when economic circumstances were more favourable.

In this chapter, we will focus on adulthood as the time in a person's life in which they have taken on greater responsibility, whether through employment, marriage or partnership, having children or living away from primary caregivers. The times at which these events occur varies substantially in different people's lives and it is therefore essential to have an understanding of the various conceptions of age, such as chronological, psychological, social and biological.

Chronological age, or the number of years since someone was born, becomes important during emerging adulthood for a number of legal issues, such as being able to drive, vote or have certain jobs, or to get access to healthcare benefits. Chronological age, however, does not necessarily correlate with psychological age, which relates to an individual's ability to adapt to various circumstances compared with others who might be the same chronological age. Psychological age also differs from social age, or the social roles and expectations relative to chronological age. While someone might be functioning at an advanced social age (relative to their chronological age), this does not necessarily imply that they are also advanced psychologically, although these tend to be related.

Biological age, or the age in terms of physical health and development, is yet another conception of age. For example, while a 14-year-old female may biologically be capable of motherhood, the social role of motherhood is often considered more appropriate for women in their 20s or 30s in Western societies (social age). Similarly, at the other end of the spectrum are the wide differences between older people of various chronological ages and biological ages. For example, a 60-year-old may participate in competitive athletics and be healthier than many 40-year-olds, but both these differ from a 60-year-old who has been diagnosed with dementia and has had double knee replacements.

Chronological age is the concept that is almost exclusively used in healthcare practice, but it has many limitations and health professionals need to be careful about basing health judgments on this alone. Because of the extreme variability in the health of older people, some have argued that healthcare should not be related to chronological age but, instead, should be relevant to need, health conditions or biological age. For example, because policies are related to healthcare provision relevant to specific chronological ages (e.g. various cancer screening programs are only available for certain age groups), those who do not ‘fit’ in this conception (e.g. residents from refugee backgrounds or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with chronic conditions) can miss out on important healthcare (see, for example, the case study: Jane on page 67).

Theories

The theories of human development usually outline various stages of life pinned to chronological ages. However, others have argued that imposing chronological age on human development is imprecise at best (Hendry & Kloep 2002, Kloep et al 2009) and can be demeaning, or even damaging at worst. We will consider some of the stage theories while also bringing in other views of what occurs during human development. In this section, we will first review Erikson's theory, and will then explore Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory, Kohlberg's theory of moral judgment, and Hendry and Kloep's lifespan model of developmental challenge.

Erikson's theory

Erik Erikson is probably the most well known developmental psychologist whose lifespan theory extends into adulthood. Other theorists, such as Freud and Piaget, only extended their theories to puberty (Freud's ‘genital stage’) and around age 11 (Piaget's ‘stage of formal operations’. See Chs 1 and 2 for more information on these.). Perhaps the complexities with adulthood and the lack of well-defined, discrete, developmental stages directly related to age have challenged theorising in this area.

The three main stages of Erikson's theory relevant to adulthood are the stages of intimacy versus isolation, generativity versus stagnation and integrity versus despair (Erikson 1950, 1982, Erikson & Erikson 1997) (see Ch 2, Table 2.2). The stage of intimacy versus isolation is characterised by either the seeking of companionship and intimate love with another person or becoming emotionally isolated and fearing rejection or disappointment. This stage is usually said to occur during early adulthood and is often associated with the chronological ages of 18–24 years. In terms of healthcare practice, health professionals who recognise that people at this stage may be struggling to come to terms with intimacy issues and those multiple factors that contribute to isolation can serve a very useful role in assisting clients to successfully resolve this stage. For example, linking clients with support services, community organisations or self-help programs and groups can go a long way in preventing issues that could become more serious if left unrecognised and reinforce their isolation. This is supported by considering the relationship between social isolation and mental disorders such as schizophrenia (e.g. Cantor-Graae 2007) and that three in four mental disorders occur before age 24 (Kessler et al 2005).

Middle adulthood, according to Erikson, is characterised by a contribution to the next generation, usually through work or employment or having a family (i.e. generativity) or by becoming socially inactive (i.e. stagnation). One of the limitations of the application of Erikson's theory is that it can be interpreted as an either/or dichotomy; whereas, in reality, adults may find that in some aspects of their lives they have been generative but in other aspects have a sense of stagnation. Take, for example, a woman who is highly successful in her career but who never had children. While she may have a strong sense of generativity in her career, she may have regrets for not having had children (being stagnant in that area), although we must not assume that someone who has not had children would have regrets. However, it is also usually not this simple. For example, many families also contribute to their siblings' families rather than have their own families (see section on adoption later in this chapter) and this could be considered either generativity or stagnation, depending upon how the person sees it. It is therefore important to consider diversity in the development and understanding of these concepts and the importance of considering assumptions that might be made around these concepts. Always check with clients about their own understanding of where they are at in life.

Finally, in Erikson's theory, older adults make sense of their lives either as having integrity (i.e. being meaningful) or they may despair about the things that they did not achieve or accomplish in life. Erikson's theory is usually considered in the context of an individual and his or her resolution of these stages. However, the wider social context has much to contribute to these stages of development. For example, health professionals, again, can serve an important role in assisting clients to develop a sense of integrity rather than despair when working with people who are chronically ill or those nearing the end of life.

Kohlberg's theory

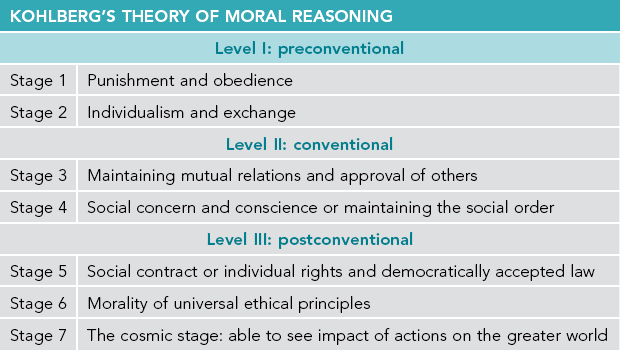

Kohlberg's theory of moral reasoning (1976) included three levels and six stages, roughly from age four to adulthood (see Table 3.1). Level I, or preconventional morality, includes stages 1 (orientation towards punishment and obedience) and 2 (individualism and exchange). Level II, or conventional morality, generally relates to children aged 10–13 and includes stages 3 (maintaining mutual relations and approval of others) and 4 (social concern and conscience or maintaining the social order). Level III, or postconventional morality, includes stages 5 (social contract or individual rights and democratically accepted law) and 6 (morality of universal ethical principles). Stages 5 and 6 are most relevant to adulthood and healthcare, although Kohlberg postulated that some people never enter these stages. In stage 5, people are rational and can be thoughtful and critical of laws and legal issues but inevitably will conform to laws and human rights as morally ideal. In stage 6, however, universal ethical principles will outweigh legal concerns in a moral dilemma. Kohlberg also later included a stage 7 (the cosmic stage) in which people would be able to see the impact of their action on the greater world, rather than only their immediate world (Kohlberg & Ryncarz 1990).

In terms of healthcare, the relevance of Kohlberg's theory is obvious. There are many moral and ethical dilemmas that health professionals contend with on a regular basis and the resolution of these dilemmas will partly depend on where a person is at in terms of these stages and how the dilemmas are resolved. But it is perhaps too restrictive to view these as internal stages of moral development. Dealing with moral dilemmas regularly and the social and structural systems in place to facilitate this, such as the quality of debates with coworkers or the policies in place surrounding moral dilemmas, will influence the resolutions of these dilemmas. Take, for example, the issue of euthanasia or, for a less contentious issue, the use of a medication that has serious side effects. Kohlberg's theory would suggest that how you think about these issues can differ with a more or less developed sense of moral reasoning. Therefore, health professionals need to consider all forms of reasoning and not just believe there is only one right or wrong answer to euthanasia or medication.

Health professionals will not only benefit from understanding Kohlberg's theorising in their own practice, but consideration of Kohlberg's stages in respect of clients will help in treating clients. For example, issues of violence, drug abuse and even parenting can be understood better by considering these stages of moral development. Health professionals might consider that some clients will be thinking about these issues very differently and this may influence how health professionals will interact with and understand their clients.

Carol Gilligan is a theorist who argued that human development theories (especially Kohlberg's) do not adequately account for development as it relates to girls and women (Gilligan 1982). In her research with pregnant women contemplating abortion, she found that conflicts with responsibility to self and to others related to moral development for women that is not adequately addressed in Kohlberg's theory. Overall, Gilligan found that morality for women relates to an ethic of care and suggested that differences between men and women should not be minimised (Gilligan & Farnsworth 1995). Although some research (e.g. Jaffee & Hyde 2000) has shown that Gilligan's critiques of Kohlberg's theory were unjustified, her theorising drew attention to the often male-dominated theorising in human development.

Others' theories

Limitations to these classic theories have resulted in the need for theories that are more contextual and not so limited to Western notions of individuality and chronological age (Qin & Comstock 2005). These more recent theories include the ecological approach of Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979, 2004), Paul Baltes' lifespan perspective (Baltes 2000, Baltes & Baltes 1990, Baltes et al 2006) and the lifespan model of developmental challenge (Hendry & Kloep 2002, Kloep et al 2009).

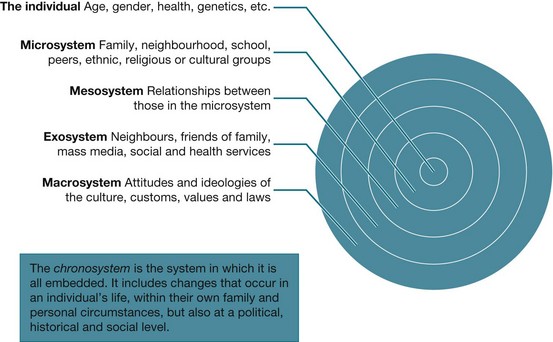

Bronfenbrenner's (1979, 2004) theory considers individual development in a wider social context that includes micro (e.g. family and work), meso (the interactions between the individual's social connections e.g. your mother interacting with your partner), exo (the social connections that the individual's social connections have e.g. your partner's work colleagues) and macro systems (e.g. religion and politics). Bronfenbrenner's system, also called a ‘bioecological’ system, is multidirectional in that it is not only the social systems that impact on the individual but that the individual also impacts on those systems (Fig 3.1). ‘Development is not something that just “happens” to the individual person but an interactive, dynamic process that involves all the system levels of a society' (Hendry & Kloep 2002 p 12).

Figure 3.1 Bronfenbrenner's model of human development Based on Urie Bronfenbrenner's 1979 model

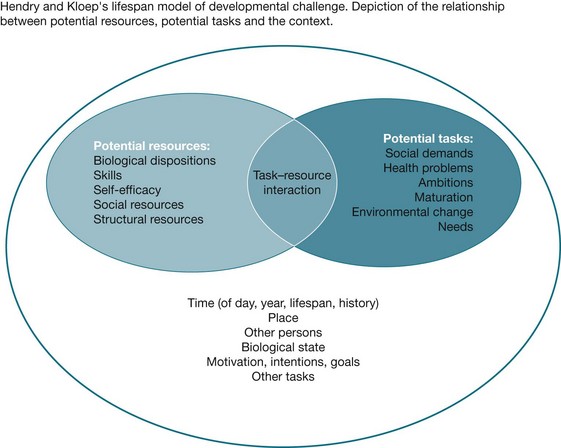

Lifespan perspectives, or lifespan theories, of human development consider development across the full lifespan and suggest that to fully understand someone's development, one needs to consider how life events influence development. The lifespan perspective also considers important social and political factors that impact on development such as policies impacting on Aboriginal Australians (like the ‘stolen generations’) or economic conditions (such as the global financial crisis). Marion Kloep and Leo Hendry, proposed such a lifespan model of developmental challenge (Hendry & Kloep 2002, Kloep et al 2009). In their model, the concepts of challenges, resources, stagnation and decay feature prominently (2002). Basically, in this model, people have ‘potential resources’, and these resources influence how an individual will respond to various challenges (‘potential tasks’) that will occur throughout life. Resources include an individual's biology, social resources, skills, self-efficacy and structural resources. An interesting feature of this model is the relationship between task demands (whether there are many or few) and the availability of resources and how they relate to feelings of anxiety or security, and whether the task is then a risk, a challenge or routine. If tasks are often routine and the resources exceed the task, then stagnation can result. Also, if there are not enough resources and the tasks are risky, then decay can result.

Take, for example, a person who is overworked with high family demands but on a low income. Over time, the resource pool will deplete and the person's development risks ‘decay’. Success, in this model, is ‘development’ and development can contribute more resources to the pool. However, people can be in a state of ‘dynamic security’ in which their resource pool is full and there are not many challenges. This is not necessarily an ideal situation because boredom can ensue. It is in this way that the model is also interesting, in that individuals are active players through their seeking or not seeking challenges to continue their development. If people do not seek out a challenge they may then be in a state of ‘contented stagnation’. On the contrary, ‘unhappy stagnation’ occurs when there are no challenges but the individual does not have the resources to seek them out.

Kloep and Hendry's lifespan model of developmental challenge (Fig 3.2) is useful for health professionals because it reflects the complex realities of people's lives that we observe in real situations. Health professionals are in a position where they may see people experiencing a challenge (e.g. a health condition or an accident) and can determine whether people and their families have the resources to successfully develop through the challenge. From the client's perspective, a health professional who assists in identifying these factors will contribute to improved outcomes, both from the healthcare situation and more holistically for the client.

Figure 3.2 Hendry and Kloep's lifespan model of developmental challenge From Lifespan development: resources, challenges and risks by Hendry L B, Kloep M 2002, Thomson, Australia, page 24. Reproduced by permission of Cengage Learning EMEA Ltd.

Milestones of adulthood

So far in this chapter we have examined theories of lifespan development in adulthood that delineate stages. We will now look at adulthood from the perspective of the main milestones of adulthood and the complexities associated with these. As key examples of milestones of adult development, we will discuss: marriage, partnership and family; parenting, mothering and caregiving; employment and career development; lifestyle, leisure, spirituality and wellbeing; retirement and the development of chronic or other illness during adulthood; and dying, death and bereavement.

Marriage, partnership and family

Being in a close relationship with another person, either through marriage, a civil union or co-habitation, is perhaps one of the most significant milestones of human life. With around 50% of the adult population currently married, and certainly many more in other forms of close and lasting relationships, and a variety of health and legal implications for those who are married or not, it is certainly an important topic for health professionals. Marriage and civil unions are also currently a highly politically charged topic worldwide. Although some countries now have legalised civil unions (i.e. a legally recognised relationship between people of either the same or opposite sex), same-sex relationships are not nationally legally recognised in many countries including Australia (although civil unions are recognised in some states, Australian Marriage Equality 2012). In New Zealand, the Civil Union Act 2004 came into effect in 2005 (Department of Internal Affairs 2011). Even so, in Australia, in 2009–10, there were 23,000 documented same-sex couple families (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2011).

With the huge religious and cultural diversity of Australia, mate selection, marriage, partnership and family are correspondingly diverse (de Vaus 2004, Hartley 1995). We might think that differences in marriage fall into distinct categories of ‘love marriages’ or ‘arranged marriages’ or we may have our own ideas about what it is that makes up a family. These ideas are strongly influenced by our own family, the media and other social influences.

A family, according to the ABS, is two or more people, one of whom is at least 15 years of age, who are related by blood, marriage (registered or de facto), adoption, step or fostering, and who are usually resident in the same household (ABS n.d.). This definition is a very Western conception and revolves around the concept of the ‘nuclear’ family. In that definition, for example, ‘family’ who do not live in the same household are not considered to be part of that family unit. The ABS also identifies couple families with and without children, one-parent families, step families and blended families but these, too, are basically variations on ‘nuclear’ family conceptions. However, how families are conceptualised can differ quite drastically in different cultural groups. For example, for some, the ‘family’ would not exclude those who ‘are not usually resident in the same household’ and the relevance of the ‘household’ may have different meanings for different people and groups. For some people, companion animals are very much considered to be part of the ‘family’, though they would not be included in official records or documentation.

Marriage is generally considered to be a permanent and legally recognised arrangement between two people that includes both a sexual and an economic relationship with mutual rights and obligations. An endogamous marriage is one where the bride and groom are from the same group (like Italians marrying other Italians or Jewish people marrying other Jewish people) and an exogamous marriage is one in which the partners are from differing groups (like a Catholic marrying a Muslim or someone from Iraq marrying someone from France). For example, for some Australian Aboriginal groups it is important to marry outside of one's ‘skin group’ and to marry someone from certain other skin groups only.

While only monogamous marriages are legal in Australia and New Zealand (i.e. only have one husband or wife), it is perhaps useful to know that this is not the case in all countries around the world, and with increasing migration from non-Western countries, health professionals should be aware of other types of marriage arrangements. For example, polygamy, or marriage to multiple spouses, is desirable in many Islamic countries and communities, where it is acceptable and even expected for men to have up to four wives (also called polygyny), but this arrangement is illegal in Australia. Less common are polyandrous marriages where a woman has more than one husband at the same time. Perhaps more common in Australia and New Zealand is serial monogamy, or successive marriages that may be short or long term.

There are also various notions of relatives that are important for health professionals to recognise. For example, consanguineal kin are people who are related by blood, ancestry or descent and affinal kin are people who are related by marriage. In-laws and their relatives are therefore affinal kin. Adopted kin are family created through adoption and fictive kin are those who you might consider to be related to you, like calling your best friend your sister or a family friend your ‘aunt’.

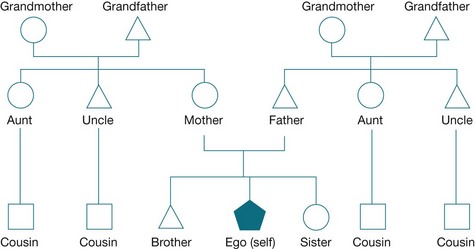

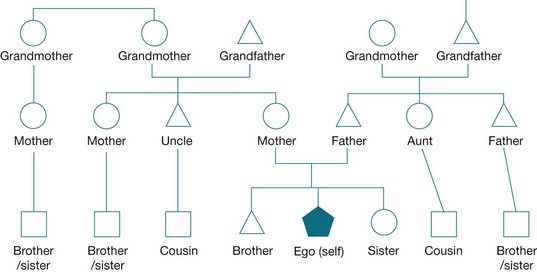

Figures 3.3 and 3.4 illustrate only two of the many ways that relationships in a family can be construed. Figure 3.3 shows the Euro kinship pattern while Figure 3.4 illustrates the Dravidian kinship pattern. The Euro kinship pattern is common in Western groups, while the Dravidian system is found in South India and in some Aboriginal and Oceanic groups. These are only two kinship patterns and there are a number of other ways in which relationships between blood and marriage can be understood. However, in Australia and New Zealand, perhaps the Dravidian and the Euro patterns are most common.

Figure 3.3 Euro kinship DOUSSET, Laurent 2011. Australian Aboriginal Kinship: An introductory handbook with particular emphasis on the Western Desert. Marseille: pacific-credo Publications.

Figure 3.4 Dravidian or Australian Aboriginal kinship DOUSSET, Laurent 2011. Australian Aboriginal Kinship: An introductory handbook with particular emphasis on the Western Desert. Marseille: pacific-credo Publications.

In Euro kinship, siblings are called brothers and sisters and offspring from the brothers and sisters of one's mother and father are called cousins. The brothers and sisters of one's mother and father are not distinguished and are referred to as aunts or uncles, based on gender. Similarly, the parents of one's parents are referred to as grandmother or grandfather, again, depending on gender.

In Dravidian kinship, on the other hand, a person can have multiple mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers who are outside the immediate family unit. For example, the sister of one's mother is also called mother and the daughter or son of that mother is called a brother or sister. In terms of parenting (discussed next), this kinship pattern can be very useful. For example, if a teenage boy, whose biological father is not available, is getting into trouble, then another ‘father’ may be called upon to offer guidance. In terms of healthcare, a mother's sister may take children to healthcare appointments in her role as another mother. Another characteristic in Aboriginal kinship systems is ‘avoidance relationships’, which is the avoidance of, or not interacting with, certain relatives out of respect. For example, a man and his mother-in-law constitutes an avoidance relationship.

Overall, the number of marriages per year, and the marriage rate, has decreased over time (Hayes et al 2011, Statistics New Zealand 2012). Age at marriage has been steadily increasing, and living together before getting married (i.e. cohabitating) is now a very common practice (Hayes et al 2011, Statistics New Zealand 2012).

Marriage is an important consideration of health professionals because of the research showing various relationships between marriage (or being single) and health (Jaffe et al 2007). For example, people who are married have a longer life expectancy: ‘Marriage reduces the risk of an earlier death as a person is less likely to participate in risky behaviour and more likely to nurture or “guardian” each other's health through promoting good diet and physical care' (Elliot 2008 p 1). A large study in the United States by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Schoenborn 2004) found that married people were overall (except in bodyweight) healthier than people who were not married. This research also showed that marriage benefits the health of men more so than women. This better health includes being less likely to suffer various conditions such as headaches or back pain, as well as healthier lifestyle factors such as not smoking, not drinking alcohol or not being physically inactive. Married men, however, were more likely to be overweight, which might lend some credibility to the old saying that the best way to a man's heart is through his stomach! Interestingly, the patterns did not hold for people who were living together but not married. Their health was similar to the poorer health reported by divorced or separated adults (Schoenborn 2004).

Divorce and family breakdown

Like marriage, partnership and having a family, divorce and family breakdown are major milestones in adult development when they occur, and can have both positive and negative consequences. These effects depend on the social contexts and consequences of the divorce or family breakdown. For example, divorce with children involved can be very complicated, but the outcomes largely depend on how these complications are managed (Amato 2010). While there is a large body of research showing negative health consequences of divorce (Amato 2010, Schoenborn 2004), staying in violent marriages or in highly dysfunctional relationships may be more harmful (Amato 2010, Emery 2009). Whether those involved marry again is another consideration in the interpretation of the health consequences of divorce. When working in healthcare with people who have divorced or separated from long-term partners, or children of parents who have divorced, it is important to get a full contextual picture of the family situation before making assumptions about the health and social effects.

Parenting, caregiving and re-conceptualising children

Data indicate that the average Australian family includes roughly 1.7 children who are, on average, 18 months different in age (Hayes et al 2010). The mother would have been about 30 years old when she had her first child and chances are the couple will have divorced after 12 years of marriage. While this can contribute to a static and narrow view of families in Australia and New Zealand, the reality is that family composition, parenting and divorce are highly diverse and change drastically over time (Cribb 2009, de Vaus 2004, Hayes et al 2010). Take, for example, sole-parent households, blended families, teenage parents, same-sex parents, fostering, adoption and grandparents taking responsibility for bringing up their grandchildren. Becoming a parent or the caregiver of children is a major milestone of adulthood, challenging identity and social roles. In fact, being a parent or carer of children changes almost everything a person does and can do.

As discussed in Chapter 2, parenting is an important contributor to children's development, but it is highly complex and diverse. One of the complexities of parenting relates to the different ways of parenting or interacting with children. Most research has been conducted in Western countries, with corresponding biases in terms of what is considered to be 'good parenting', as well as how parenting styles are represented.

For example, as discussed in Chapter 2 (see Box 2.3) one popular version of parenting includes four dimensions: authoritative, indulgent, neglectful and authoritarian (Baumrind 1991, Baumrind et al 2010). Although authoritative parenting is generally considered a preferable parenting style in the Western context, there are communities and contexts in which this parenting style would be considered inappropriate. Consider a context in which the environment is socially or physically dangerous, such as a socially and economically depressed locale with high rates of violence. In this context, authoritative parenting might not be beneficial and authoritarian parenting might have better health and social outcomes for children. Similarly, in a context in which being educated is the most important and useful goal and the environment is less risky, then authoritative or even indulgent parenting may be preferable.

Another issue related to parenting style is the way a society or parents view children. In some contexts children are viewed as an economic resource for parents because they can gain employment and bring money into the household, or they can work around the house and thereby relieve the parents for employment purposes, or they will marry into another family and attract wealth. In some contexts, babies may be considered dispensable in poverty conditions or other problematic conditions (Omokhodion & Uchendu 2010, Scheper-Hughes 1985). In contexts with greater social and economic stability, such as in the West, children may be viewed more idealistically and seen as people in themselves rather than as resources for the family.

Dharmalingam (1996) studied family size preferences in a small village in southern India where there were two major industries: a brickwork and a beedi factory (beedis are a type of cigarette). Children could begin employment at the age of five years. Dharmalingam found several interesting things. First, villagers who were more economically disadvantaged reported wanting more children than those who were better off. About 50% of those who wanted more children reported wanting as many as possible or as many as God gave them. From a Western perspective this seems irrational because those with less money and fewer resources should want fewer children. However, the social logic is quite clear when children are considered as resources: those who are economically more disadvantaged have greater benefits with more children because they attract more resources than what they use. However, when Dharmalingam asked the villagers about their reasons for having boys or girls, direct economic reasons were usually ranked third. But the major reasons for having boys were so that they could inherit the property, provide security against risks and provide for the parents in their old age. All of these are to do with economic resources.

Importantly, when children are considered as a resource, parenting patterns will be very different from when children are not seen in that way (Scheper-Hughes 1985). Advising people in different social and economic contexts to reduce the number of children they have because of the problems associated with the increasing world population, while good-intentioned, may inadvertently result in compromising their standard of living and social and economic resources. The values that are derived in one social and economic context can be harmful when applied in a different context.

In greater socially and economically advantaged contexts, having fewer children has greater advantages and benefits, especially in relation to education and the cost of education, particularly in many Western contexts. Having fewer children provides for a greater share of the resources because of the way that resources are allocated or structured in Western societies. Therefore, having fewer children and educating them better has the same social logic spelt out by Dharmalingam's participants but built upon the particular social and economic context.

Health professionals are often in the position to observe family dynamics and interactions between caregivers and children and it is important to recognise and not be critical of dynamics that may seem unusual or different from one's own way of doing things. Family relationships and how children are viewed within the family depends heavily on the context, milieu or culture in which people have been raised and it is these factors that may not be easily accessible to health professionals.

Parenting and attachment theory

With an increasing diversity of family composition and parenting roles, particularly in developed Western countries, there has been greater attention to the role of ‘mothering’ in society and in families. Early theorists such as John Bowlby emphasised that mothers are of crucial importance to children and developed his original attachment theory primarily based on clinical observations and monkeys raised without their mothers. He believed, and the ethos at the time agreed wholeheartedly, that mothers are of special importance to raising healthy and happy children as the primary caregiver, and described this bond as of ‘lasting psychological connectedness between human beings’ (Bowlby 1969 p 194).

While the early attachment of children to parents and others is not disputed and has had a revival of late (Holmes 2011), attachment no longer refers solely to mothers and their children. Depending on how mothering is defined, it may or may not involve only women as mothers. Consider, for example, Arendell's (2000) definition of a mother as someone who does the relational and logistical work of child rearing. This work can be done by men or women. For example, currently, in Sweden, men can be considered to be ‘mothering’ under some conditions of work practice and have time off work. However, others have argued that the role of motherhood is unique for women and that men cannot fully be ‘mothers’ (Doucet 2006). Riggs and Due (2010) discuss the complexities in relation to gay male parents and surrogacy in India, arguing for greater recognition of issues of gender as well as power and privilege and how that intersects with roles of mothering and caretaking.

In terms of considerations for health professionals, again, the diversity of parenting roles and relationships cannot be underestimated. How health professionals manage diversity in practice can significantly impact on healthcare and health outcomes.

Adoption or fostering

Adoption or fostering of children provides another interesting example of the diversity of family dynamics and the role of children within families. Often, in Western countries, a child may be homed through adoption or fostering because the mother or parents cannot look after her or him. This may be because of poverty, drug habits, violence, neglect, death or illness, and so a child may be taken as a ward of the state or country. In many circumstances an opportunity is first provided to other family members, such as grandparents, aunts or uncles, to look after the child. In many cases this is not possible so people who are completely unrelated (biologically) may adopt or foster and raise the child. These adoptive parents are also becoming increasingly diverse in their circumstances. For example, consider that with greater recognition of same-sex partnerships, that these couples may opt for fostering or adoption as a way to raise children. While there are some lay views that these ‘non-traditional’ parenting arrangements are problematic, a recent study on adoptions by gay or lesbian couples found very few differences to heterosexual couples who raised adopted children (Farr et al 2010).

However, in many non-Western countries, and in many communities within Western countries, forms of adoption and fostering are and have always been a common event. Children may be raised by kin (with full knowledge of their origin) with no problematic situations and within very healthy contexts. This is common, for example, in both traditional and contemporary M ori social relations. For example, a woman might ask her sister if she would raise one of her children and this can be arranged even before the child is born. This arrangement can be viewed as an ultimate gift from sister to sister. These arrangements can be made for a wide range of reasons. For example, it may be that the adopting sister has had problems conceiving and therefore would like a child. In other cases the adopting sister might already have a family but still be asked to raise a child, maybe because of her parenting skills. This sort of adoption process can be seen as another way of facilitating and maintaining bonds and relationships between people in kin-based communities.

ori social relations. For example, a woman might ask her sister if she would raise one of her children and this can be arranged even before the child is born. This arrangement can be viewed as an ultimate gift from sister to sister. These arrangements can be made for a wide range of reasons. For example, it may be that the adopting sister has had problems conceiving and therefore would like a child. In other cases the adopting sister might already have a family but still be asked to raise a child, maybe because of her parenting skills. This sort of adoption process can be seen as another way of facilitating and maintaining bonds and relationships between people in kin-based communities.

It is important to emphasise that, in some circumstances, when this kind of fostering or adoption occurs, it does not necessarily indicate that any of the people involved are having problems such as the baby being in danger of neglect or that the family are not fully able to raise the child. Sometimes grandparents might raise children and the grandparents might not be much older than the parents. It is unlikely, as would be the case for many Western families, that a 70-year-old grandmother would raise a newborn baby for her daughter. But a 40-year old grandparent might easily raise a grandchild.

One important element in this fostering scenario is that the context involves a kin-based community in which everyone spends time together and is close (even if conflict occurs regularly). This means that the child would know his or her ‘biological’ parents and see them regularly, which is unlike how adoption was conducted until very recently in most Western systems – where the child was made anonymous and the ‘biological’ parents' names were kept secret. There are numerous examples of this sort of kin-adoption or fostering and reports of this from all corners of the world, mainly where extended or kin-based families remain intact. This practice is still common among M ori in New Zealand, for example (e.g. Cameron 1966, Hegar 1999, Hegar & Scannapieco 1999, McRae & Nikora 2006, Shirley et al 1997).

ori in New Zealand, for example (e.g. Cameron 1966, Hegar 1999, Hegar & Scannapieco 1999, McRae & Nikora 2006, Shirley et al 1997).

Overall, the stage of adult life involving parenting and child rearing is common and important. This is not just for the children involved but also for the parents. Nevertheless, while disagreement exists between some researchers and theorists regarding exactly how this developmental phase operates in adult life, there is agreement that what is considered ‘normal’ adult behaviour at this stage is now diverse and changing. These early life contexts also contribute significantly to health outcomes, the development of health and health issues, and influence the effectiveness of healthcare interventions. Healthcare services will be much more effective when health professionals are informed with even a basic understanding of these contexts and complexities of their clients.

Employment, career and lifestyle

Employment and careers are obviously important to our life stages, but research shows that the nature of career development has changed over time. While parents or grandparents may have been employed in the same place for their entire adult life, many people today make substantial career changes throughout their working life. Again, while the majority of Australians and New Zealanders will finish high school and then go on to either trades training or university before moving into a career, there is a substantial minority who will not navigate such a clear path to employment opportunities and career options.

In Australia Census data show that the percentage of families with children with both parents employed has gradually increased to 63% in 2009–10, while the percentage of families with children where neither parent is employed has gradually decreased from 7% in 1996 to 5.4% in 2006 and 5% in 2009–10 (ABS 2011). The employment status of parents is related to the age of dependent children in the household (ABS 2011). For example, as children get older, there is a higher proportion of parents employed. Overall, the 2009–10 data show an increase in the employment of mothers, with 66% of mothers employed in couple families with dependent children (compared with only 59% in 1997) (ABS 2011). Additionally, in lone mother families with dependent children, in 2009–10, 60% were employed, but in 1997 only 46% were employed. Although there are a number of economic benefits for families when the caregivers are employed, this also means that there are many children in homes where the only parent is working. There are many social and health effects of these arrangements and they are not necessarily all positive.

‘Being employed’ is a major aim and milestone of adulthood and has a number of health benefits. Equally, being unemployed can negatively impact on health, as can being employed in the wrong job or in poor working conditions (Bambra et al 2010, Benach et al 2010). Underemployment is when someone is employed at a level lower than their qualifications or skills. Overemployment, in contrast, is the employment of someone in a position that requires greater skills or knowledge than what the person has. Both of these conditions can be stressful and adversely impact on health. Additionally, poor work environments and high-risk jobs can make employment more problematic than beneficial.

Lifestyle patterns largely develop during early adulthood with the development of social circles, employment and education and family (married or not, having children or not). Lifestyle patterns that develop during early adulthood – such as smoking, alcohol or other drug consumption; religious or spiritual activity; physical activity; and dietary habits – reveal their impacts in middle adulthood. Lifestyle, in health psychology, has largely been a concept relevant to individuals and research, and intervention in this area has largely focused on individual behaviour change. However, lifestyle is inextricably linked with social conditions, economic circumstances such as employment, place of residence and the larger community.

Spirituality and wellbeing

The massive growth in literature and research relating to spirituality and religion and their relevance to wellbeing and health is testament to the importance of these topics for contemporary health professionals. During adulthood, religious or spiritual development can change dramatically depending on many factors such as social groups that one is involved with, employment situations and major life events (especially traumatic ones). Additionally, beliefs and practices may change more than once. This is known as ‘religious mobility’ or ‘religious switching’. For example, someone may become involved in a new church through the invitation of someone at work, but then, perhaps after moving to a new town, may find that their church attendance ceases, but they commence other activities, such as joining a social running group.

Overall, research generally finds that religiosity or spirituality contribute to improved wellbeing and can contribute to health improvements and healing from illnesses (Koenig et al 2012), although these benefits can change with religious switching (Scheitle & Adamczyk 2010). Spirituality, while once (and still often) synonymous and used interchangeably with ‘religion’ and organised religious practices (e.g. Catholicism, Islamism and Buddhism), has become a field of study on its own, encompassing both secular and religious practices. In this sense, the definition proposed by Gomez and Fisher (2003) is apt: ‘… spiritual well-being can be defined in terms of a state of being reflecting positive feelings, behaviours, and cognitions of relationships with oneself, others, the transcendent and nature, that in turn provide the individual with a sense of identity, wholeness, satisfaction, joy, contentment, beauty, love, respect, positive attitudes, inner peace and harmony, and purpose and direction in life’ (Gomez & Fisher 2003 p 1976).

La Cour and Hvidt (2010) described the three domains of secular, spiritual and existential orientations in terms of meaning-making in relation to health and illness. They consider the three domains in relation to knowing (cognition), doing (practice) and being (importance), providing a useful tool to extract some of the complexities of these important topics. For example, using this framework, researchers can tease out some of the relationships between religion and health such as the social supports often associated with some religious practices (e.g. going to church) or the influence of meditation or prayer activities on health.

Given the importance of links between religion or spirituality and health, health professionals may find it very beneficial for clients to have their religious or spiritual needs considered, particularly in acute care or end-of-life contexts. For example, a recovering alcoholic undergoing inpatient cancer treatment may find it helpful for healthcare staff to assist with locating a local 12-step recovery meeting. Twelve-step recovery groups are based on spiritual principles and belief in a ‘higher power’ to relieve one of their addictions. Health professionals may also recommend, when appropriate, that clients explore religion or spirituality as part of their healing processes.

Demography

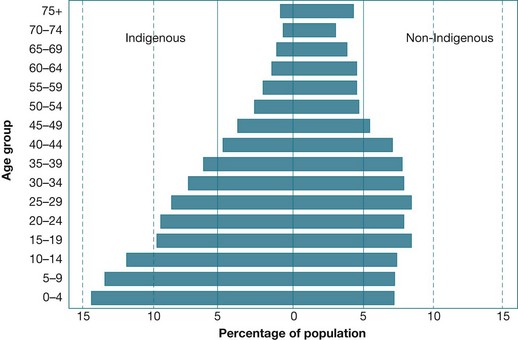

In order to appreciate the importance of age and ageing in healthcare practice, a look at the statistics or the demography of the population is essential. For example, different population groups have different age structures. This is shown in ‘population pyramids’ such as depicted in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5 Population pyramid of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations of Australia, 2011 Source: HealthInfoNet 2011

Figure 3.5 illustrates the percentage of the population in five-year age groups for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population of Australia. We can deduce from this figure that the social issues for human development might vary considerably for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. For example, while non-Indigenous Australians have a greater proportion of people in the middle-age groups, Indigenous Australians have a greater proportion of the population represented in the younger age groups. The social impact of that is the greater demand on older Indigenous Australians for child care (compared with non-Indigenous Australians) but greater demands on non-Indigenous Australians for elderly care. These data illustrate the importance of a wide range of factors (in this case, population structure) when considering human development.

Other demographic factors that are important to consider in healthcare include, for example, the populations living in urban, rural or remote areas and access to health services. It is also important to consider gender and place of birth and languages spoken as important considerations in healthcare. With an understanding of the demographics of the places where we live and work, we can potentially anticipate and prepare for ensuring that the health services we provide are appropriate and meeting the needs of the clients we see.

Chronic illness and other health issues

Chronic illness, disability and other health issues increasingly become a part of reality as people age. Health psychology has also gained an increasing role in chronic and other illnesses because of the growing recognition of behavioural and social factors contributing to these conditions. For example, in 2010, ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and dementia and Alzheimer's disease were the top three underlying leading causes of death in Australia (ABS 2012). With the ‘ageing’ population of Australia, it is perhaps not surprising that for the leading causes of death in Australia, dementia and Alzheimer's disease have gone from rank 8 in 1997 to rank 6 in 2001 to rank 4 in 2006 and in 2010, rank 3. Deaths from dementia and Alzheimer's disease have nearly doubled since 1997 (from 3294 in 1997 to 6542 in 2006) and are more likely to affect women than men (ABS 2008).

For health professionals, these statistics suggest that illnesses are more common partly because people are living longer. But, more importantly, as people age and certain illnesses become more prevalent, people will increasingly need care and specialised processes and equipment. For example, there has been an increase in the need for dialysis machines for kidney disease stemming from diabetes. Therefore, not only are there a greater number of people with various illnesses, but also people are required to travel to access specialised equipment and care and their final years may be involved with hospitals rather than living close to families.

Death, dying and bereavement

The topics of death, dying and bereavement are often addressed in the context of older people but obviously they can affect people of all ages. They are discussed here because death, dying and bereavement become more likely as people grow older and therefore are a major part of human development for adults. Death, dying and bereavement may affect people differently depending on many factors such as the contexts of the death (e.g. whether by an accident or after a long illness), the family and support situation available (to both the person who dies and those who love or have cared for them), and economic circumstances.

Bereavement has been defined as the ‘objective situation of a person who has suffered the loss of someone significant’ (Boerner & Wortman 2001 p 1151) and grieving relates to the emotional experience of a bereavement. Perhaps the most well known theory of stages of bereavement is Elizabeth Kubler-Ross' model, which suggests that people go through stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. While the model has been useful in helping people understand their emotional experiences during a time of bereavement, it has been argued that this theory has been taken too literally, is too simplistic and has not necessarily been supported in the literature (Boerner & Wortman 2001). The idea of staged bereavement can also contribute to professionals placing too much emphasis on the stages and then pathologising people who do not go through the stages in the way a model, such as Kubler-Ross', predicts (Boerner & Wortman 2001). Some research has looked at applying ideas from stress and coping to understand grieving (Stroebe & Schut 2001).

A review by Stroebe et al (2007) of the health outcomes of bereavement suggested that there are a number of risk factors that increase vulnerability to problems with bereavement. Death of a spouse, in terms of stressfulness of life events, ranks as the most stressful experience that people have (Holmes & Rahe 1967). Grieving after someone dies is normal and, indeed, not grieving, especially if the death was of a close family member or friend, would be seen as problematic. Reactions to bereavement are generally classified according to affective (emotional), cognitive (thought-based), behavioural, physiologic-somatic and immunological and endocrine changes. Overall, bereavement increases physical ill health and physical health complaints, as well as the incidence of seeking healthcare. Complicated grief, however, is when the psychological and social aspects of grieving exceed what might be considered ‘normal’ (Ray & Prigerson 2007).

As with research on other topics relevant to health psychology (e.g. trauma and stress), it should not be surprising that research in bereavement is also exploring the positive aspects of grief and challenging previously held notions. For example, Schaefer and Moos (2001) looked at positive growth (see also literature on posttraumatic growth) following bereavement and Heilman (2005) looked at the diversity of the grief experience, particularly the positive dimensions, following the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York. Other research has explored the possibilities of creativity and art as therapy in bereavement (Bolton 2007). Chapter 11 also examines loss resulting from death, dying and bereavement.

Conclusion

To summarise, this chapter explored various stage theories in adult developmental psychology, including Erikson, Kohlberg, Bronfenbrenner, and Hendry and Kloep. Developmental milestones, such as marriage and employment, were explored and the relevance of these to healthcare practice was discussed. All of these theories and ideas can be critiqued and exceptions made to the stages or theories. While stages and generalisations about adulthood and ageing can be made, it is important to consider different circumstances at different ages and how people of various ages in differing situations might be affected. It is not possible to determine exactly how people will behave at different times of their lives, but learning how to identify differences and to expect these differences will improve the appropriateness of healthcare practice.

For example, knowing that a client in your health clinic is 21 years old provides very different health expectations compared with knowing that a client is 50 or 80 years old. However, expectations and treatment would differ greatly for a single 21-year-old client who grew up in urban Australia compared with a 21-year-old client with three children and recently arrived from the Middle East. Theories about developmental stages of adulthood can provide a guide to understanding clients but cannot predict exactly the lived human experience.

Developing an understanding of developmental (st)ages is at least partly dependent on personal experience, in addition to experience with others to understand the diversity of people's lives. With so much diversity, asking your clients about their contexts, circumstances, milestones and stages of life will go far in ensuring that the healthcare provided is appropriate and relevant.

Breen, L.J., O'Connor, M. The fundamental paradox in the grief literature: a critical reflection. Omega. 2007; 55:199–218.

Hildon, Z., Smith, G., Netuveli, G., et al. Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008; 3:726–740.

Liu, H., Umberson, D.J. The times they are a changin’: marital status and health differentials from 1972 to 2003. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008; 49:239–253.

Slater, C.L. Generativity versus stagnation: an elaboration of Erikson's adult stage of human development. Journal of Adult Development. 2003; 10:53–65.

Teachman, J. Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008; 70:294–305.

Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet

The Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet is an innovative web resource that makes knowledge and information on Indigenous health easily accessible to inform practice and policy.

Australian Institute of Family Studies

The Australian Institute of Family Studies provides bibliographies on a range of topics of interest to health psychology and lifespan development including:

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

The AIHW website provides an extensive range of publications and information relevant to material covered in this chapter. See, for example, Australia's Health 2008 Chapter 6 ‘Health across the life stages’.

http://www.healthinsite.gov.au/topics/Family_Breakdown

HealthInsite provides some useful resources relating to family breakdown and divorce.

Multicultural Mental Health Australia

MMHA provides national leadership in building greater awareness of mental health and suicide prevention among Australians from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. Through unique partnerships with Australian mental health specialists, services, advocacy groups and tertiary institutions, MMHA actively promotes the mental health and wellbeing of Australia's diverse communities through a series of campaigns, projects and information fact sheets. MMHA also produces a series of resources and training for specialist and mainstream mental health professionals.

References

Amato, P.A. Research on divorce: continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010; 72(3):650–666.

Arendell, T. Conceiving and investigating motherhood: the decade's scholarship. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000; 62:1192–1207.

Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000; 55:469–480.

Arnett J.J., Kloep M., Hendry L.B., et al, eds. Debating emerging adulthood: stage or process? New York: Oxford, 2011.

Arnett J.J., Tanner J.L., eds. Emerging adulthood in America: coming of age in the 21st century. Washington DC: American Psychological Association, 2006.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Causes of death, Australia 2006, 3303.0. Online Available http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/2093DA6935DB138FCA2568A9001393C9, 2008. [11 Aug 2008].

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Family characteristics, Australia 2009–10, 4442.0 Online Available http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4442.0Main%20Features22009-10?opendocument%26tabname=Summary%26prodno=4442.0%26issue=2009-10%26num=%26

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). n.d. Family and community glossary. Online Available http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/c311215.NSF/43b68f1dafb94862ca256eb0000221a5/dc61793ed26c330bca25715500193159!OpenDocument. [11 Aug 2008].

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Causes of death, Australia 2010, 3303.0. Online Available http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/6BAD463E482C6970CA2579C6000F6AF7?opendocument, 2012. [11 Nov 2012].

Australian Marriage Equality. Civil unions in Australia. Online Available http://www.australianmarriageequality.com/civilunions.htm, 2012.

Baltes, P.B. Life-span developmental theory. In: Kazdin A., ed. Encyclopedia of psychology. Washington DC & New York: American Psychological Association & Oxford University Press, 2000.

Baltes, P.B., Baltes, M.M. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: the model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes P.B., Baltes M.M., eds. Successful aging: perspectives from the behavioural sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Baltes, P.B., Lindenberger, U., Staudinger, U.M. Lifespan theory in developmental psychology. In: Damon W., Lerner R.M., eds. Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development. sixth ed. New York: Wiley; 2006:569–664.

Bambra, C., Gibson, M., Sowden, A., et al. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2010; 64:284–291.

Baumrind, D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991; 11(1):56–95.

Baumrind, D., Larzelere, R.E., Owens, E.B. Effects of preschool parents’ power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2010; 10:157–201.

Benach, J., Muntaner, C., Chung, H., et al. The importance of government policies in reducing employment related health inequalities. British Medical Journal. 2010; 340:c2154.

Boerner, K., Wortman, C.B. Bereavement: international encyclopedia for the social and behavioral sciences. Elsevier; 2001. [pp. 1151–1155].

Bolton G., ed. Dying, bereavement and the healing arts. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2007.

Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss. Attachment; Vol. 1. Basic Books, New York, 1969.

Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979.

, Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Bronfenbrenner U. Sage, Thousand Oaks, 2004.

Cameron, B.J., Adoption Online. AvailableMcLintock A.H., ed. 2007 (originally published in 1966). An encyclopaedia of New Zealand, 1960. http://www.teara.govt.nz/1966/A/Adoption/Adoption/en [26 Sep 2008].

Cantor-Graae, E. The contribution of social factors to the development of schizophrenia: a review of recent findings. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007; 52:277–286.

Cribb, J. Focus on families: New Zealand families of yesterday, today and tomorrow. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. 2009; 35:4.

Davis, S., Bartlett, H. Healthy ageing in rural Australia: issues and challenges. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2008; 27(2):56–60.

de Vaus, D. Diversity and change in Australian families: a statistical profile. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2004.

Department of Internal Affairs Te Tari Taiwhenua. Civil unions. Online Available http://www.dia.govt.nz/diawebsite.nsf/wpg_URL/Services-Births-Deaths-and-Marriages-Civil-Union?OpenDocument, 2011. [18 Apr 2012].

Dharmalingam, A. The social context of family size preferences and fertility behaviour in a South India village. Genus. 1996; 52:83–103.

Doucet, A. Do men mother? Fatherhood, care, and domestic responsibility. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2006.

Dousset, L. Australian Aboriginal Kinship: An introductory handbook with particular emphasis on the Western Desert. Marseille: Pacific-credo Publications; 2011.

Elliot, J., Marriage increases life expectancy. Minister for Ageing, Canberra, 2008. Online Available http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/mr-yr08-je-je135.htm [11 Aug 2008].

Emery, C.R. Stay for the children? Husband violence, marital stability and children's behavior problems. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009; 71(4):905–916.

Erikson, E.H. Childhood and society. New York: WW Norton; 1950.

Erikson, E.H. The life cycle completed. New York: WW Norton; 1982.

Erikson, E.H., Erikson, J.M. The life cycle completed. New York: WW Norton; 1997.

Farr, R.H., Forsell, S.L., Patterson, C.J. Parenting and child development in adoptive families: Does parental sexual orientation matter? Applied Developmental Science. 2010; 14(3):164–178.

Gilligan, C. In a different voice: psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1982.

Gilligan, C., Farnsworth, L. A new voice for psychology. In: Chester P., Rothblum E.D., Cold E., eds. Feminist foremothers in women's studies, psychology, mental health. Binghamton: Harrington Park Press, 1995.

Gomez, R., Fisher, J.W. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the spiritual well-being questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003; 35:1975–1991.

Hartley, R. Families and cultural diversity in Australia. Sydney: Allen and Unwin; 1995.

Hayes, A., Weston, R., Qu, L., et al. Families then and now: 1980–2010. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2010.

Hayes, A., Qu, L., Weston, R., et al. Families in Australia 2011: sticking together in good and tough times Australian Institute of Family Studies. Online Available http://www.aifs.gov.au/institute/pubs/factssheets/2011/fw2011/index.html, 2011. [11 Nov 2012].

HealthInfoNet, What details do we know about the Indigenous population Online. Available, 2011. http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/health-facts/health-faqs/aboriginal-population [18 Apr 2012].

Hegar, R.L. The cultural roots of kinship care. In: Hegar R.L., Scannapieco M., eds. 1999. Kinship foster care: policy, practice and research. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999:17–27.

, Kinship foster care: policy, practice and research. Hegar R.L., Scannapieco M. Oxford University Press, New York, 1999.

, Death, bereavement and mourning. Heilman S.C. Transaction, New Brunswick, 2005.

Hendry, L.B., Kloep, M. Lifespan development: resources, challenges and risks. Australia: Thomson; 2002.

Holmes, J. Attachment, autonomy, intimacy: some clinical implications of attachment theory. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 2011; 70(3):231–248.

Holmes, T.H., Rahe, R.H. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967; 11:213–218.

Jaffe, D.H., Manor, O., Eisenbach, Z., et al. The protective effect of marriage on mortality in a dynamic society. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007; 17(7):540–547.

Jaffee, S., Hyde, J.S. Gender differences in moral orientation: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2000; 126(5):703–726.

Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-or-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005; 62:593–602.

Kloep, M., Hendry, L., Saunders, D. A new perspective on human development. Conference of the International Journal of Arts and Sciences. 2009; 1(6):332–343.

Koenig, H.G., King, D.E., Carson, V.B. Handbook of religion and health. Auckland: Oxford; 2012.

Kohlberg, L. Moral stages and moralization: the cognitive developmental approach. In: Lickona T., ed. Moral development and behaviour: theory, research and social issues. New York: Holt; 1976:33–35.

Kohlberg, L., Ryncarz, R.A. Beyond justice reasoning: Moral development and consideration of a seventh stage. In: Alexander C.N., Langer E.J., eds. Higher stages of human development. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990:191–207.

La Cour, P., Hvidt, N.C. Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Social Science and Medicine. 2010; 71(7):1292–1299.

McRae, K.O., Nikora, L.W. Whangai: remembering, understanding and experiencing. MAI Review. 2006; 1:1–18.

Omokhodion, F.O., Uchendu, O.C. Perception and practice of child labour among parents of school-aged children in Ibadan, southwest Nigeria. Child Care and Health Development. 2010; 36(3):304–308.

Qin, D., Comstock, D.L. Traditional models of development: appreciating context and relationship. In: Comstock D.L., ed. Diversity and development: critical contexts that shape our lives and relationships. Australia: Thomson, 2005.

Ray, A., Prigerson, H., Grieving. Encyclopaedia of stress. second ed. Fink, G., eds., eds. Encyclopaedia of stress; Vol. 2. Elsevier, Australia, 2007:238–242.

Riggs, D.W., Due, C., Gay men, race, privilege and surrogacy in India. Outskirts 2010; 22. Online Available http://www.outskirts.arts.uwa.edu.au/volumes/volume-22/riggs [1 May 2012].

Schaefer, J.A., Moos, R.H. Bereavement experiences and personal growth. In: Stroebe M.S., Hansson R.O., Stroebe W., et al, eds. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2001:145–167.

Scheitle, C.P., Adamczyk, A. High-cost religion, religious switching, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010; 51(3):325–342.

Scheper-Hughes, N. Culture, scarcity and maternal thinking: Maternal detachment and infant survival in a Brazilian shantytown. Ethos. 1985; 13:291–317.

Schoenborn, C.A. Marital status and health: United States, 1999–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 351. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004.

Shirley, I., Koopman-Boyden, P., Pool, I., et al. New Zealand. In: Kamerman S.B., Kahn A.J., eds. 1997 Family change and family policies in Great Britain, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997:207–304.

Smith, K., LoGiudice, D., Dwyer, A., et al. Ngana minyarti? What is this? Development of cognitive questions for the Kimberley Indigenous Cognitive Assessment. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2007; 26(3):115–119.

Statistics New Zealand. Marriages, civil unions, and divorces: year ended December 2011. Online Available http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/marriages-civil-unions-and-divorces/MarriagesCivilUnionsandDivorces_HOTPYeDec11.aspx, 2012. [11 Nov 2012].

Stroebe, M.S., Schut, H. Models of coping with bereavement: a review. In: Stroebe M.S., Hansson R.O., Stroebe W., et al, eds. Handbook of bereavement research: consequences, coping and care. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2001:375–404.

Stroebe, M.S., Schut, H., Stroebe, W. Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet. 2007; 370:1960–1973.