CHAPTER 28 Nutrition

At the completion of this chapter and with some further reading, students should be able to:

• Identify the three major groups of nutrients

• List the six groups of vitamins required for health

• List the eight major elements or electrolytes required for health

• Identify the functions and common food sources of the essential nutrients

• Describe the physical characteristics associated with a usual nutritional status

• Identify factors and disorders that may affect a client’s nutritional status

• Identify commonly used assessment techniques to measure a client’s nutritional status

• State the components of a healthy balanced diet

• State the principles of good nutrition

• Describe how the healthy balanced diet can be adapted to meet specific dietary beliefs and/or requirements

• Apply appropriate principles to meet nutritional needs throughout the life span, during episodes of illness or alterations in physiological or psychological status

• Assist in meeting a client’s nutritional needs accurately and safely in relation to assisting at mealtimes and caring for a client requiring enteral and parenteral feeds

This chapter focuses on the nutritional needs of clients over the life span and how a client’s wellbeing can be affected by an alteration in the quantity and quality of absorbed nutrients. Nurses are required to assess and educate clients to maintain nutritional health status and provide information on how to undertake care for clients related to nutrition. Nutritional practices and requirements may vary according to age, height, sex, religion, culture, socioeconomic factors and physical and psychological status. Nurses must be able to accommodate for all these different factors when they plan, care and educate clients.

I was admitted to a hospital for a knee replacement recently and I was there for 10 days. During that time I lost over 7 kg and my GP told me I was dehydrated when I was discharged. During my stay I was unable to move easily due to knee splints and my age; often meals were brought into my room and left on the table, which was often out of my reach. By the time the nursing staff came to check that I had received my meal, the food was cold and unappealing, I was unable to eat it and after a few days I no longer had an appetite. After a week my wife talked to the unit manager and nursing staff were encouraged to check that I was able to access my table prior to the meals being delivered. This made such a difference. The other thing that some nurses did which made me feel refreshed and more likely to eat was check that all my hygiene needs had been met. Something as simple as a face and hand wash before the meal arrived made such a difference. Another message I would like to give nursing staff is that it is important that patients have access to fluid regularly, as well as with their meals. My water jug was often not accessible and that meant that I didn’t drink, so not only did I not eat but also I became very dehydrated which I believe had a negative impact on my recovery.

NUTRITION OVERVIEW

Food and nutrition have long been recognised as important contributors to health. However, food and nutrition affect more than just the physical aspects of our health and wellbeing. The buying, preparing and eating of food is part of everyday life. For many cultures, including Australia and New Zealand, food is a focus for social interactions with family and friends. For some, it is also an economic concern.

While eating has a psychosocial and cultural significance in life, the major roles of food intake are to provide nutrients necessary for the development and growth of cells and the replacement of substances required by cells to maintain efficient body function. Information about the ingestion and digestion of food and the absorption of nutrients is provided in Chapter 30. After the digested nutrients have been absorbed into the blood and lymph, they are distributed to the cells for further chemical processing, releasing the energy necessary for body function. The process of metabolism converts the nutrients into chemical forms that produce energy and rebuild body tissue. The two phases of metabolism are: anabolism (or constructive phase), when simple substances derived from the nutrients are converted into complex substances that can be used by the cells; and catabolism (or destructive phase), when these complex substances are reconverted into simpler forms to release the energy necessary for cell function (Harris et al 2006).

The term nutrition is used to describe all the processes by which the body uses food for energy, maintenance and growth. It is important to recognise that nutritional requirements vary in response to changes throughout the life span. Factors that increase the body’s metabolic demand include the periods of rapid growth during infancy and adolescence, pregnancy and lactation, increased physical activity and periods of stress, disease or trauma. Metabolic requirements diminish with reduced energy demands, decreased physical activity and age.

Adequate nutrition is partially dependent on the ability of the body to ingest and digest food, to absorb nutrients from the intestine and to excrete waste products. Additionally, the quality and quantity of food consumed has an important influence on a client’s current and future health status. It is important that a diet contains the essential nutrients for each stage of the life span in order to maintain health and wellbeing.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines undernutrition or malnutrition as:.

Malnutrition means ‘badly nourished’ but it is more than a measure of what we eat, or fail to eat. Clinically, malnutrition is characterized by inadequate intake of protein, energy, and micronutrients and by frequent infections or disease (WHO Expert Consultation 2004).

Food is not just a source of nutrients. It is important for good social and emotional health as well as physical health. Food and eating are part of the way people live their lives (NHMRC 1998). The eating patterns of individuals and families are constantly being shaped and changed by a variety of factors. Some of these include:

• The kinds of food that are available at the local supermarket or shop

• Cultural, religious and family background

• The amount of time available to shop for, prepare and cook food

• The personal likes and dislikes of household members

• Values, attitudes and beliefs about food and eating

• Knowledge about food and nutrition

• Advertising campaigns and food promotions

• The amount of money that can be spent on the food budget

• Physical or psychological status of the client such as allergies or an intolerance to specific foods or nutrients; difficulty in chewing or swallowing; level of independence/dependence; disorders that interfere with nutrition which may result in maldigestion, malabsorption or loss of nutrients. These, in turn, can lead to emotional states such as depression or anxiety, which may further impact on the physical or psychological status of the client.

NUTRITION ASSESSMENT

It is important for the nurse to realise when commencing a nutritional assessment that nutritional status is the result of the complex interaction between the food we eat, our overall state of health and the environment in which we live: in short, food, health and caring are the three ‘pillars of well-being’. These three pillars of well-being should be included in a nursing assessment (National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 1998).

Obtaining information about the client’s appetite, food preferences, height, weight, level of activity and observing their general appearance will enable the nurse to assess a client’s nutritional status. Observation of a client’s general appearance provides information about their general state of health and their nutritional status. Some characteristics of altered nutritional status are presented in Table 28.1. Assessing the client’s eating pattern and their nutritional status may also identify problems or risk factors.

Table 28.1 Characteristics of altered nutritional status

| General | Cachexia, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, cardiomegaly, weight loss or gain |

| Hair | Dull, dry or brittle hair; hair thinning or loss |

| Nails | Brittle, broken, ridged or spoon shaped. Pale nail bed |

| Skin | Dry or scaly, bruising or petechiae unrelated to trauma, ulceration, abnormal colour changes, dermatitis |

| Oral mucosa | Pale mucous membrane, ulceration and cracking, ketone-smelling breath |

| Lips | Angular stomatitis, cheilosis |

| Tongue | Swollen or smooth tongue, atrophic papilla, cracking or fissuring |

| Gums | Spongy and/or bleeding gums, gum recession |

| Teeth | Mottled, dental caries, absent teeth |

| Conjunctiva | Pale to reddish-pink |

| Vision | Diminished visual acuity or loss |

| Cardiac | Tachycardia, cardiomegaly, palpitations, angina |

| Muscles | Muscle wasting, atrophy, diminished strength or tone, constipation |

| Skeleton | Curvature of arms or legs, altered gait, shortened stature, fractures |

| Neurological | Altered mood or affect, reduced concentration span, coordination, sensory or motor activity and reflexes, vision loss |

| Urine | Ketonuria, urobilinogen, haemoglobinuria, haematuria |

In addition to the physical characteristics associated with poor nutritional status, psychological symptoms may be evident. A client with a poor nutritional status may experience irritability, lethargy, apathy or inability to concentrate. It is possible, however, that these symptoms and the physical signs presented in Table 28.1 may be related to an underlying condition and/or the client’s nutritional status. Certain groups of clients may be more at risk of a poor nutritional status, including those who are:

• Suffering emotional or physical stress

• Impaired cognitively or intellectually

• Alcohol, drug or nicotine dependent

• Diagnosed with a chronic illness

To maintain or promote an appropriate intake of food and therefore a good nutritional status, clients should be encouraged to follow the principles of a balanced healthy diet that provides the body with essential nutrients. However, it is also important when looking after clients to take into account that while the consumption of food provides for the physiological needs of a client, it can also contribute to their social and emotional needs (NHMRC 2003b).

Nutritional assessment and the older person

When performing a nutritional assessment on an older person it is important that the nurse determines the type, quantity and frequency of food eaten. According to Watson and colleagues (2006) clients who eat ≤2 meals a day are at risk of undernutrition. Nurses should ask the older person about the following:

• Any special diets (e.g. low-salt, low-carbohydrate) or self-prescribed fad diets

• Intake of dietary fibre and prescribed or over-the-counter vitamins

• Weight loss and change of fit in clothing

• Amount of money clients have to spend on food

• Accessibility of food stores and suitable kitchen facilities

The ability to eat (e.g. to chew and swallow) needs to be evaluated. Poorly fitted dentures, decreased taste or smell may reduce the pleasure of eating, so clients may eat less. Clients with decreased vision, arthritis, immobility or tremors may have difficulty preparing meals and may injure or burn themselves when cooking. Clients who are worried about urinary incontinence may reduce their fluid intake; as a result, they may eat less food (Watson et al 2006).

It is important for the nurse to realise that ageing changes the interpretation of many measurements that reflect nutritional status in younger people. For example, ageing can alter height. Weight changes can reflect alterations in nutrition, fluid balance, or both. Despite these age-related changes, body mass index (BMI) is still useful in older clients. If abnormalities in the nutrition history (e.g. weight loss, suspected deficiencies in essential nutrients) or BMI are identified, a thorough nutritional evaluation, by the doctor, which includes laboratory measurements, is indicated (Watson et al 2006).

Healthy balanced diet

Eating a balanced diet is vital for good health and wellbeing. Food provides human bodies with the energy, protein, essential fats, vitamins and minerals to live, grow and function properly. People need a wide variety of different foods to provide the right amounts of nutrients for good health. Enjoyment of a healthy diet can also be one of the great cultural pleasures of life. The foods and dietary patterns that promote good nutrition are outlined in the Australian Dietary Guidelines (NHMRC 2003b, 2003c). An unhealthy diet increases the risk of many diet-related diseases.

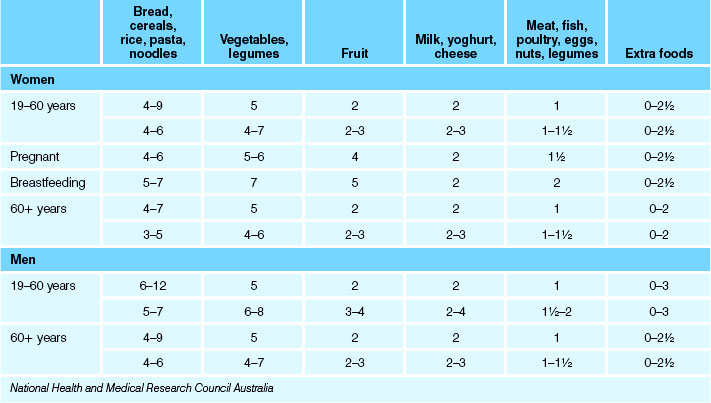

The total amount of food that a person needs each day to provide themself with the energy and nutrient needs will vary depending on the person’s age, sex and activity levels, and whether or not the person is pregnant or breastfeeding. The NHMRC (2003b) provides recommended dietary intake levels (RDIs) for energy and the various nutrients across various conditions, age and sex categories. The RDIs are specified in the nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand. RDIs or ‘allowances’ are the levels of intake of essential nutrients considered adequate to meet the nutritional needs of most healthy individuals. They are based on estimates of requirements for age/sex groups and, therefore apply to the ‘average individual’ in each group. As they incorporate generous factors to allow for variations in metabolism, absorption and individual needs, RDIs exceed the actual nutrient requirements for most healthy persons. Therefore they are not synonymous with requirements. For these reasons, 70% of the RDI is often used as a basis for guidance about individual food intake.

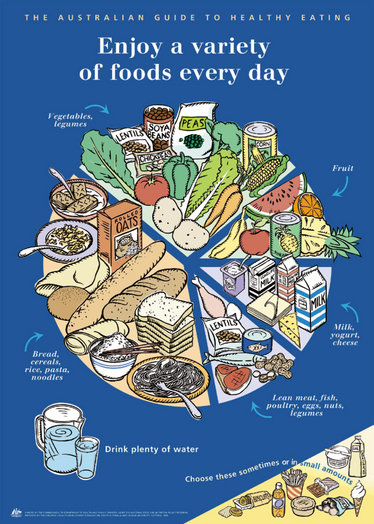

The Australian Guide to Healthy Eating is Australia’s current food selection guide. It is the official food selection guide of the Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, and is based on the Dietary Guidelines for Australians (NHMRC 1988). A diet consistent with the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating recommends people consume a variety of foods across and within the five food groups and avoid foods that contain too much added fat, salt and sugar. The Guide aims to promote healthy eating habits throughout life to assist in reducing the risk of health problems, such as heart disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes. The Australian Guide to Healthy Eating is a visual representation of the Dietary Guidelines for Australians. The aim of the Guide is to encourage the consumption of a variety of foods from each of the food groups every day in proportions that are consistent with the Dietary Guidelines. There are four main messages in the Guide: enjoy food—eating should be an enjoyable experience; eat a variety of foods every day (this means eating foods from each of the food groups); some foods should be eaten only occasionally or in small amounts; drink plenty of water.

It is important to acknowledge that the five food groups have changed. Foods are now grouped according to the main nutrient they contain. Fruits and vegetables are now two separate food groups and there is no fat group. The five foods groups are:

It is expected that small amounts of unsaturated fats and oils will be consumed with breads and cereals but additional fats and foods such as cakes, biscuits, hot chips and sugary drinks should be consumed only occasionally. For a sample of serve suggestions from the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating for women and men see Table 28.2.

Nutritional needs of infants and children

Throughout all stages of development, a healthy balanced diet is necessary to provide the nutrients required for the body’s needs. For information on maternal and newborn nutrition, see Chapter 43.

Breast milk or an appropriate infant formula should remain the main source of milk until 12 months of age, although cow’s milk can be used in cooking or with other foods (Australasian Society of Clinical Immunologists and Allergists (ASCIA) 2008). More research is needed to determine the optimal time to start complementary solid foods. Based on the currently available evidence, many experts across Europe, Australia, New Zealand and North America recommend introducing complementary solid foods from around 4–6 months. There is little evidence that delaying the introduction of complementary solid foods beyond 6 months reduces the risk of allergy. When a child is ready to eat solids, the parents/carers should consider introducing a new food every 2–3 days according to what the family usually eats (regardless of whether the food is thought to be highly allergenic). One new food should be introduced at a time so that reactions can be more clearly identified. If a food is tolerated, this should be continued as a part of a varied diet (ASCIA 2008).

The aim of introducing solids is to wean the infant off milk to prevent such problems as failure to thrive, malnutrition and anaemia, and also to educate the palate to different tastes and textures; eating therefore becomes largely a learning process. Rice cereal, pureed stewed fruit and vegetables are suitable first foods. By 6–8 months of age, chewing movements begin and the infant can be introduced to more coarsely textured foods.

When the infant begins to grasp objects and put them in their mouth, they may be ready to be introduced to finger foods. An infant can take fluids from a cup at about 7–8 months of age. Giving fruit juice to a child from a bottle should be discouraged, as this may contribute to the development of jaw and tooth deformity and dental caries, and excessive volumes of fruit juice may result in diarrhoea.

At about 12 months of age the infant should be eating a range of basic foods. The diet should consist of bread and cereals, fruit and vegetables, meat and/or other protein foods, milk and/or milk products and small amounts of butter or margarine. Salt, sugar and fatty foods should be avoided.

The toddler and pre-school child

During this stage of development a child’s rate of growth is slower than in infancy and this is normally reflected by a decrease in appetite, although appetite is generally unpredictable during these years. Children are learning to feed themselves and to eat new foods. They should eat a variety of foods from all of the food groups.

Children should be encouraged to eat a variety of nutritious foods, which should be served at regular times in a calm and relaxed atmosphere. Because young children are active, snacks between meals are important. The foods offered for snacks should contribute to the nutritional needs of the child, while foods with poor nutritional value should be avoided. Small hard foods, such as nuts, raw carrots, etc., are potentially dangerous for the young child, as they may be inhaled and obstruct airways. Some other things to watch for are:

The school-age child

During the first 12 months of life the foundation is laid down for good dietary practices. By the time the child is of school age, eating patterns are usually firmly established. As the child grows and develops, their tastes can change, and foods that were previously enjoyed may be refused, while the child may acquire a taste for other foods, due in part to social interaction and their changing physiological needs and subsequent sensory changes.

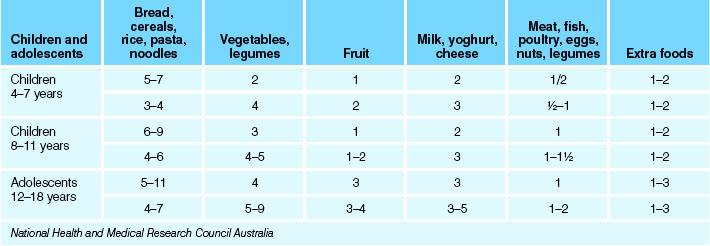

Nutritional requirements are similar to those for children of preschool age, although kilojoule needs are diminished in relation to body size (Table 28.3). However, fat and protein reserves are being laid down for the increased growth needs of the adolescent period, and the school-age child should be encouraged to consume a healthy balanced diet consisting of foods from each of the five food groups and should be discouraged from consuming foods that have poor nutritional value. If the child consumes an excessive quantity of food and/or food that is high in kilojoules, and does not exercise, they may be at risk of childhood obesity and subsequent development of conditions such as adult-onset diabetes and cardiovascular disease. A study by Booth and colleagues (2001) showed that the rates of overweight and obesity in Australian and New Zealand children increased more rapidly in the previous 10–15 years than in earlier decades. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2010) reported that three in five adults (61%) were either overweight or obese in 2007–08 and one in four children (25%) aged 5–17 years were overweight or obese in 2007–08. Wake and colleagues (2003) state that approximately 60% of obesity may be due to lifestyle factors such as unhealthy eating habits, decreased physical activity and increased sedentary behaviours. The NHMRC has stated that there is a demonstrated association between childhood obesity and adult obesity. Overweight and obesity are associated in later life with many diseases and conditions such as coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and osteoarthritis (AIHW 2010). Iron-deficiency anaemia is a more immediate nutritional problem in school-age children due to inadequate amounts of iron in the diet.

Adolescence

From 10 years of age, children’s bodies are developing rapidly to prime the body for reproduction. A pre-puberty growth spurt occurs earlier in girls than in boys, as they store more fat, which initiates adolescence faster (see Ch 11 for more information). During this time there can be major changes in the selection and volume of food; hormones alter senses such as taste to enable the adolescent to adapt to changing nutrient requirements. Some clients at this age may be vulnerable to self, peer and social influences that alter their perception of appearance and self-worth and drastically modify their eating habits (see ‘Eating disorders’ later in this chapter).

Energy requirements

In addition to the consumption of foods from the five food groups that provide the essential nutrients, dietary requirements need to be considered in terms of energy requirements. Energy is needed for all the chemical and physical activities of the body, such as muscular activity, production of glandular secretions and the synthesis of substances in cells. The amount of energy required is the amount necessary to maintain physiological processes and depends on factors such as age, sex, climate, body build, height and weight, level of physical activity and usual function or dysfunction.

Energy requirements are increased during periods of rapid growth, for example, during pregnancy, infancy and adolescence and when a person engages in a high level of physical activity. Certain types of body dysfunction, such as hyperthyroidism, a disorder of the thyroid gland, can also increase the amount of energy required. Energy requirements are decreased when a client’s level of physical activity is low, with certain metabolic conditions, such as hypothyroidism, and during stages of development when there is little growth, such as old age.

The two units of measurement that specify the energy value of food are calories and joules. A calorie is defined as the amount of heat required to raise 1 g of water by 1°C. A joule, which is the standard international (SI) unit of energy and heat, is equivalent to the amount of work performed when a 1 kg mass is moved 1 m by the force of 1 newton. One calorie is equal to 4.184 joules. As joules are very small units, it is more convenient to measure food energy in terms of kilojoules. One kilojoule (kJ) is 1000 joules.

The energy values of the three major types of nutrients are:

Energy expenditure varies with the level of physical activity a client engages in and ranges from about 5 kJ/min during sleep to about 120 kJ/min during heavy physical activity. When the intake of kilojoules is increased or energy expenditure is decreased, weight gain occurs. Conversely, loss of weight occurs when the intake of kilojoules is decreased or energy expenditure is increased.

Basal metabolism is the term used to describe the minimal maintenance of all normal body functions at rest and in the absence of disease. The amount of energy required to support basal metabolism is measured when a client is awake but at complete rest and has not eaten for at least 12 hours. The measurement is expressed as basal metabolic rate (BMR), according to the number of kilojoules consumed per hour per square metre of body surface area (or per kilogram of body weight). The BMR is one diagnostic test commonly used to estimate nutritional needs. Variations in the BMR between clients of the same weight and height may be due to alteration in body composition, such as muscle mass as opposed to fatty tissue, and the presence of certain disease states.

There are two types of measurement which may be used by clinicians when determining body fat and risk of chronic disease. These are the body mass index (BMI) and a weight circumference.

The BMI is a simple index of weight-for-height that is commonly used to classify underweight, overweight and obesity in adults. It is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2). For example, the BMI of a male who is 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and weighs 115 kg is:

The value obtained when this formula is used should be rounded to the nearest whole number.

BMI values are age-independent and the same for both sexes. However, BMI may not correspond to the same degree of fatness in different populations due, in part, to different body proportions. The health risks associated with increasing BMI are continuous and the interpretation of BMI gradings in relation to risk may vary for different populations (World Health Organization Expert Consultation 2004).

A BMI value below 20 is common in certain ethnic groups, such as people of Asian descent, and in athletes, but otherwise indicates that a person is underweight. A BMI of 20–25 is within the healthy weight range. A BMI of 25–30 may indicate more muscular build or overweight, while a value of 28–40 is defined as moderate to severe obesity and a value above 40 signifies morbid obesity (WHO Expert Consultation 2004).

The waist measurement compares closely with a person’s body mass index (BMI), and is often seen as a better way of checking for risk of developing a chronic disease. Measuring the waist circumference is a simple check to tell how much body fat is present and where it is placed around the body. Where body fat is located can be an important sign of the risk for developing an ongoing health problem. Extra body fat around the abdomen sits very close to vital organs and creates more stress on the heart. Abdominal or belly fat is strongly linked to elevated levels of insulin. It increases the serious risk of developing insulin resistance syndrome and type 2 diabetes.

Regardless of your height or build, for most adults a waist measurement of greater than 94 cm for men and 80 cm for women is an indicator of the level of internal fat deposits which coat the heart, kidneys, liver and pancreas and increase the risk of chronic disease. Recommended waist measurements are yet to be determined for all ethnic groups. It is believed that they may be lower for Asian men than for Caucasian men and are likely to be higher for Pacific Islanders and African Americans (men and women). The limited data currently available indicates that the risk factors in Aboriginal populations appear to be similar to those in Asian populations; and the risk factors in Torres Strait Islander populations appear to be similar to those found in Pacific Islander populations (NHMRC 2003b).

Measuring a client’s waistline is a simple check for a nurse to perform and for accurate measurement the nurse should ensure that:

• Measurement occurs against the skin

• The client breathes out normally

• The tape measure is snug but does not compress the skin

• The correct place to measure the waist is horizontally halfway between the lowest rib and the top of the iliac crest. This is roughly in line with the client’s navel (belly button).

Glycaemic index

Glycaemic index (GI) classifies carbohydrate foods according to how rapidly glucose is released from them and absorbed into the blood. It has traditionally been used to treat clients with diabetes mellitus but is now being used for establishing optimal diets for the general populace. The lower the GI the slower the rate of absorption and the slower the rate of insulin release. Complex carbohydrates such as starch provide lower GI nutrients and result in a more stable blood glucose level (Harris et al 2006).

Some simple carbohydrates, such as those found in fruits, have a lower GI value than some complex carbohydrates, such as those found in rice and potatoes. Foods with low-GI values have been used to treat hypercholesterolaemia and obesity. Low-GI foods include multigrain breads, bran, legumes, milk, yoghurt and fruits. High-GI foods, of which there are more than 70, include rice, potatoes, wholemeal and white bread, and some cereals. Further health benefits may be gained by including foods that are high in fibre.

NUTRIENTS

Nutrients are chemical substances in food that provide energy, build and maintain cells or regulate body processes. The essential nutrients are:

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are a group of organic compounds that includes sugar, starch and cellulose. They are composed of one or more monosaccharide (single-sugar) units. Sugars can be classified as either simple or complex and are divided into groups according to the complexity of their molecular structure. Simple sugars, or monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose and galactose (Harris et al 2006). Disaccharides, which are a combination of two sugars, include sucrose, lactose and maltose. For example, glucose and fructose combine to form sucrose. Complex sugars or polysaccharides are a combination of many sugars and include starch, glycogen and cellulose. Before carbohydrates can be utilised by the body cells, disaccharides and polysaccharides must be converted by chemical digestion into glucose.

Carbohydrates provide energy, assist in the metabolism of fat and act as a protein sparer (if there is insufficient carbohydrate in the diet, protein is converted to glucose and used for energy). Carbohydrate foods also supply indigestible cellulose, which adds bulk to the intestinal contents, resulting in stimulation of peristalsis. The major food sources of carbohydrates are:

Proteins

Proteins are a group of nitrogenous compounds composed of chains of amino acid subunits. Twenty-two amino acids have been identified in humans. Eight of these, the essential amino acids, the body is unable to make, and they must be obtained from dietary sources. The remaining 14 non-essential amino acids can be synthesised by the body. Before proteins can be utilised by the cells, they must be broken down by physical and chemical digestion into their constituent amino acids. According to the number and type of amino acids present, proteins are classed as either complete (containing all essential amino acids) or incomplete (lacking one or more essential amino acids) (Harris et al 2006).

Proteins build and repair tissue and supply energy (protein that is not needed for growth and repair of tissues is converted into glucose and stored in the liver and muscles as a reserve store of energy). The major food sources of protein are meat, fish, eggs, cheese, milk, poultry and soya beans (complete (or first-class) protein); and cereals, lentils, legumes and nuts (incomplete (or second-class) protein).

Lipids (fats)

Lipids are a group of substances that are insoluble in water and are composed of fatty acids and glycerol. Fatty acids are classed as saturated or unsaturated. Saturated, or solid, fats are chiefly of animal origin, such as butter, and contain a full complement of hydrogen. Unsaturated, or soft or liquid, fats are chiefly of vegetable origin, such as margarine, and are capable of adding more hydrogen to their molecular structure.

Before fats can be utilised by the body cells they must be broken down by chemical digestion into their constituent fatty acids and glycerol. Fat supplies energy and may be used in the tissues or stored in adipose tissue, which functions to support and protect nerves and organs from trauma, insulate the body to prevent excessive heat loss or gain and as a reserve store of fuel. Fats also supply the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K as well as stimulating adolescence, fertility and mood, and suppressing appetite through the action of hormones such as leptin, secreted by adipocytes (Harris et al 2006).

The major food sources of fat are animal fats, present in meat, butter, cream, egg yolk, cheese and fish oils, and vegetable fats, present in margarine, cocoa and oils such as olive, safflower, corn and peanut.

Water

Water is a chemical compound obtained by the body from food and fluid and as a result of the metabolism of protein, fat and carbohydrate in the tissues. Water constitutes about 60% of the total body weight in an adult and is present as intracellular fluid and extracellular fluid. Water is also the basis of all body secretions and excretions.

Water is necessary for the digestion, absorption and metabolism of food, for the production of secretions and for the maintenance of body fluids. Water is also necessary for the regulation of body temperature by evaporation of sweat, and for the elimination of waste products through the kidneys, bowel, skin and lungs.

Water is present in all body fluids and as part of the cellular structure of solid foods. Foods vary in water content; fruit and vegetables contain about 80–90% water, meat contains about 70% and bread contains about 35%.

Fibre

Dietary fibre, often referred to as cellulose, is the fibrous parts of food that the digestive system has difficulty in digesting. Fibre creates bulk in the stools, which enhances defecation and is used to prevent or minimise symptoms of certain disorders, such as haemorrhoids, diverticular disease, formation of gallstones, simple constipation and intestinal cancer (Harris et al 2006). Foods with high fibre content are fruits, vegetables and wholegrain products. Clinical Interest Box 28.1 provides discussion on the effects of constipation on the older client.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 28.1 Constipation and the older client

Constipation can occur at any age but is common in the elderly, associated with diminished exercise, fibre and fluid intake, as well as diminished neurogenic gastrointestinal regulation. Measures to avoid constipation are required to reduce the incidence of conditions such as diverticulosis, megacolon, carcinoma, strokes and heart attacks. A nutritional assessment of dietary intake is required, as is examination for any underlying pathologies, such as those causing disorders such as iron-deficiency anaemia from per-rectal bleeding. The clinical features of this anaemia include constipation, lethargy, easy exhaustion, pale conjunctivae and pagophagia (craving for ice). Iron is obtained in large quantities from meat, and many older clients may be unable to obtain and consume or absorb the required amounts. Iron-replacement therapy may be required; however, supplemental iron can result in constipation, false-positive occult blood test and gastrointestinal upset.

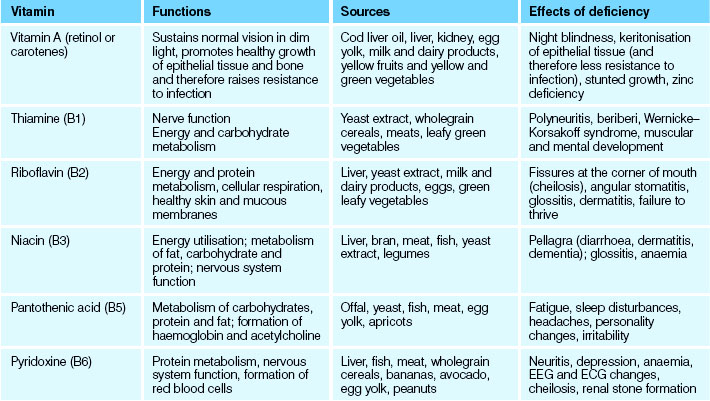

Vitamins

Vitamins are a group of organic compounds that, with few exceptions, must be obtained from dietary sources. Although they have no energy value, they are essential for normal metabolic and physiological bodily function. The term vitamin was first used in 1912, and letters of the alphabet were assigned to them as they were discovered. Now that more is known about their composition, the chemical name for a vitamin is frequently used.

Vitamins are classed as being either water- or fat-soluble. The water-soluble vitamins are easily destroyed during the preparation and prolonged cooking of food. If they are consumed in excess of the body’s need, they are excreted in the urine. Fat-soluble vitamins are oxidised by exposure to air, light and high temperatures. As fat-soluble vitamins are not soluble in water, any excess is stored in the body, and a condition known as hypervitaminosis may occur, which may result in organ failure (Harris et al 2006).

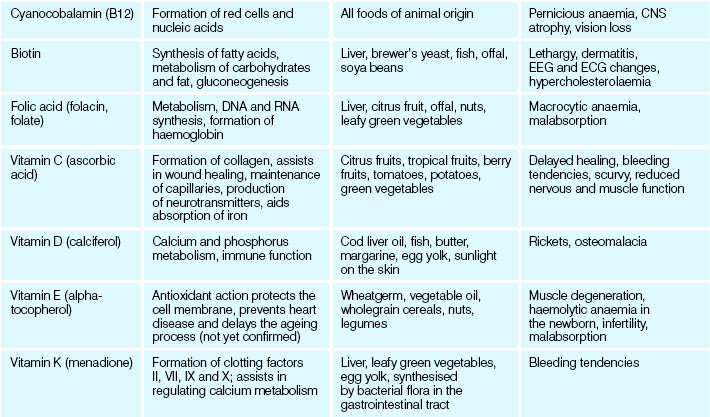

Excessive intake of vitamin A over long periods can result in hypervitaminosis A, a condition characterised by yellow discolouration of the skin (often mistaken as jaundice), loss of appetite and dry itchy skin. Excessive intake of vitamin B may result in allergic-type reactions. Hypervitaminosis D may occur if excessive amounts of vitamin D are taken and is characterised by nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, general irritability and severe impairment of kidney function. In normal circumstances a healthy balanced diet will provide the body with sufficient quantities of all vitamins without the need for supplemental vitamin ingestion. Table 28.4 describes the functions and effects of vitamin deficiencies.

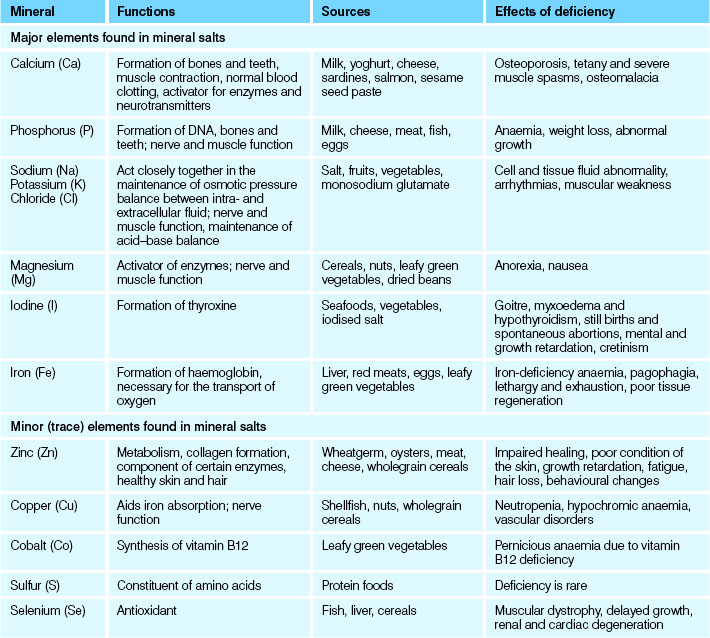

Mineral salts

Mineral salts are a group of compounds that play an important role in metabolism, maintenance of blood pressure, cardiac function, fluid and electrolyte balance, acid–base balance and the regulation of other body processes. Storage and processing of food does not alter its mineral content, although mineral salts may be lost when food is soaked or cooked in water. The elements that mineral salts contain are classed as either major or trace elements; trace elements are present in only minute quantities in the body. A mineral salt that has the property of being a conductor of electrical current is referred to as an electrolyte. The functions and effects of mineral salt deficiencies are listed in Table 28.5.

DIETS TO MEET CLIENT NEEDS

A person’s normal diet depends on their age, pattern of eating and the food they choose. Dietary requirements may change during illness; for example, a client may avoid eating foods that cause adverse reactions such as indigestion, nausea or diarrhoea. The client’s diet may also need to be adapted as part of their treatment during certain conditions and disease states.

While acknowledging the factors that influence a client’s choice of foods and observing any restrictions to their diet in the management of disease processes, nurses should encourage the consumption of healthy balanced meals, following the principles of good nutrition. The principles of good nutrition are that:

• A variety of foods from each of the basic food groups should be eaten each day

• The intake of fat, sodium, sugar and alcohol should be limited

• The intake of complex carbohydrate and dietary fibre should be high

• Adequate amounts of water should be consumed

• Food should be prepared and cooked in such a way that the nutrient value is not lost

• Dietary intake and energy expenditure should be adjusted to achieve and maintain the appropriate weight for age and height

• Breastfeeding for babies is recommended

• People should become aware of the information in the labels of prepared and packaged foods. Notice should be taken of the expiry date, the presence of preservatives and other additives. The listing of ingredients on the container denotes the relative quantities of each, with the major ingredient listed first. The remainder are listed in order of decreasing quantities.

Clients may choose, or may be prescribed, certain diets, as follows.

Healthy balanced diet

A healthy balanced diet is one without dietary restrictions or modifications. A client may select the foods they prefer within the principles of good nutrition and diets based on age, health and cultural or religious beliefs. Some clients choose to follow a diet in which specific foods or nutrients are restricted or increased, as part of a commitment to a healthy lifestyle. Other people will follow a diet based on cultural or religious commitment.

Nutrition Australia uses different food ‘models’ to depict a healthy approach to eating based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines. An example is the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating Model (Fig 28.1) and includes:

Vegetarian diets

Clients may choose to follow a vegetarian diet for health, personal, ecological or religious reasons. Vegetarian diets exclude all flesh foods, such as meat, fish and poultry, and have an intake high in plant foods. The lacto (milk)–ovo (egg) vegetarian diet includes milk, other dairy products and eggs, while a lacto-vegetarian diet includes milk and other dairy products but excludes eggs. The vegan diet (strict vegetarian) excludes all animal-derived products and consists of plant foods only.

Religious and cultural diets

Certain religious or cultural groups have particular rules concerning the choice, preparation and storage of specific items in the diet; however, clients may vary in their adherence to religious dietary doctrines and the nurse should not assume that all people who are of a particular faith strictly follow the religious dietary restrictions. Some examples of religious dietary restrictions are:

• Hinduism (Hindu): people of the Hindu faith abstain from eating beef products and follow a vegetarian diet. Stimulants are forbidden

• Islam (Moslem, Muslim): all pork and pork products, alcohol and caffeine are forbidden. Any meat consumed must be from animals slaughtered according to strict rules (Halal). Ramadan, a period of fasting, forbids eating or drinking of any substance from sunrise to sunset for one lunar month

• Jehovah’s Witness: dietary restrictions against any foods that are prepared with blood, for example, some meat pies and blood sausages. Additionally, some Jehovah’s Witnesses may refuse to eat meats if they are unsure if the meat presented was not properly bled. There are no specific ‘rules’ for correct bleeding of an animal so it is best to discuss this requirement with the individual client and their family

• Judaism (Jewish faith): foods must be ‘kosher’ (prepared according to Jewish law) and only certain parts of an animal may be eaten. All pork, shellfish and predatory birds are prohibited. Meat and dairy products are never eaten at the same time and are required to be stored and prepared separately. Certain periods of fasting are observed, such as Yom Kippur, a 24-hour fast. Passover, lasting 8 days, prohibits the consumption of leavened (yeast-containing) bread. Cooking is not permitted on Saturdays (the Sabbath)

• Mormon (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints): meat, although not forbidden, is eaten infrequently. Drinks containing caffeine (e.g. tea, coffee and cola) are not permitted. Tobacco is also forbidden

• Roman Catholic: Ash Wednesday and Good Friday are specified days on which abstinence from meat is obligatory. In addition, Roman Catholics are required to fast for 1 hour before taking Holy Communion

• Seventh-Day Adventist: a lacto-vegetarian diet is commonly followed and stimulants such as coffee, tea and alcohol are not permitted.

Therapeutic diets

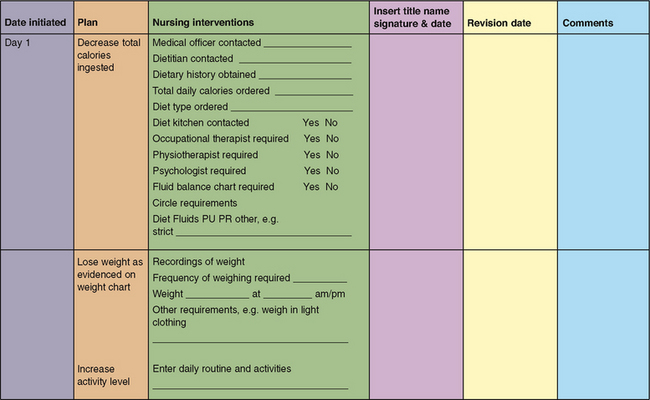

A specific diet may be prescribed to rectify a nutritional deficiency, to decrease specific nutrients or to provide modifications in the texture or consistency of food. If a therapeutic diet is prescribed, it is important that the client understands the reasons for any restrictions or modifications. Information about various therapeutic diets is provided in Table 28.6. Figure 28.2 shows part of a sample nursing care plan for a client on a restricted diet.

| Diet | Description | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Clear liquid | No solids permitted and only fluids that leave no residue, are non-irritating and non-gas forming are allowed, e.g. water, black tea or coffee, clear soups and fruit drinks | |

| Full liquid | All fluids, plus foods that become liquid at room temperature, e.g. jelly and ice-cream, are permitted | |

| Soft | Semi-solid easily digested foods are permitted, e.g. soup, cooked cereal, milk pudding, mashed or pureed vegetables and fruit, eggs, soft meats and fish | |

| Low fibre | Foods that can be absorbed easily and leave no colour or residue are permitted, e.g. clear soup, tender meat, fish or chicken, eggs, refined cereal products, jelly, ice-cream | |

| High fibre | Foods that contain residue that adds bulk to the faeces and stimulates peristalsis, e.g. fruit, vegetables, nuts, wholegrain products | |

| Low kilojoule | The number of kilojoules is reduced below the usual daily requirement. Foods that are low in fat or refined carbohydrate are permitted | Weight reduction |

| High kilojoule | The number of kilojoules is increased above the usual daily requirements. Foods that are high in carbohydrate, protein and fat are included | Weight gain. To replace and repair damaged tissue, e.g. after severe burns |

| Low cholesterol | Foods that are high in fat and cholesterol are restricted, e.g. butter, cream, whole milk, cheese, egg yolk, meat | Prevention or treatment of heart disease, atherosclerosis, high serum cholesterol levels |

| Low fat | Foods that are high in fat are restricted, e.g. butter, cream, whole milk, cheese, fatty meat | |

| Low protein | The amount of protein is restricted and fat and carbohydrate is increased | Kidney or liver failure |

| High protein | The amount of protein is increased and foods high in complete protein are included, e.g. meat, fish, eggs, cheese, milk | To replace and repair damaged tissue |

| High iron | Foods that are rich in iron are included, e.g. liver, red meat, green leafy vegetables | Prevention and treatment of iron-defciency anaemia |

| Controlled carbohydrate (diabetic) | The amounts of carbohydrate, kilojoules and protein are controlled to meet nutritional needs, to control blood sugar levels and to maintain an appropriate body weight | Diabetes mellitus |

| Controlled sodium | Foods that are high in sodium are omitted and no salt is added to food | Cardiovascular disease. Certain kidney diseases, liver failure, fluid retention (oedema) |

| Gluten restricted | Foods that contain gluten are eliminated, e.g. wheat, rye, oats, malt, barley. Rice and corn are permitted | Coeliac disease |

| High vitamin | A balanced healthy diet that includes foods that are high in one or more defcient vitamins |

NURSING PRACTICE AND NUTRITIONAL NEEDS

Each institution has its own system for delivering meals, and the nurse should ensure that both the client and their immediate environment are prepared in readiness for mealtimes.

Assisting clients at mealtimes

Key aspects related to providing clients with meals

• Nursing care should be planned to ensure that there are no unpleasant sights, sounds, smells or treatments being performed during mealtimes, as these could interfere with appetite.

• Clients should be offered the use of toilet facilities, and their hygiene needs should be attended to before meals arrive in the ward.

• Ambulant clients may need assistance to a table; non-ambulant clients should be assisted into a comfortable position. Eating areas should be cleared of unnecessary items to provide space for the meal tray, and placed within reaching distance for the client.

• When the meals arrive the nurse should ensure that each client receives the correct meal, prepared in the correct manner according to their dietary, ethnic, cultural or religious requirements and that all the necessary items (e.g. correct eating utensils) are provided.

• Medications that are required before, during or after the meal are administered (e.g. insulin).

• During mealtimes the nurse should assist as necessary (e.g. by cutting food, opening packets, pouring fluids or help with feeding).

• If a client is not able to eat what has been provided, measures should be taken to obtain an alternative meal type or other form of nourishment.

• The nurse should observe and chart the client’s intake of food and inform nursing, medical or dietitian staff if the client’s intake declines.

• Following the meal, the nurse should ensure that the client has the opportunity and equipment to perform normal hygiene (e.g. cleaning of hands, face and teeth or dentures).

Certain clients may experience difficulty or be unable to feed themselves for a variety of reasons, including age, general weakness, pain due to surgery, paralysis or limitation of movement due to, for example, the presence of arm splints, intravenous lines or casts. A client who is dependent may experience embarrassment if they require assistance at mealtimes; the nurse should therefore endeavour to make mealtimes as normal and enjoyable as possible.

Key aspects related to assisting an adult client at mealtimes

• Ensure that the client is comfortable before starting a meal.

• Elimination and hygiene needs should be attended to before a meal is started.

• The client may require to be assisted into a comfortable position and the table adjusted to the appropriate height.

• The meal should be placed where it can be seen and smelt, to stimulate the appetite.

• Condiments (e.g. salt and pepper) should be provided and may be added to the food, provided the client is not on a salt-restricted diet.

• The nurse should ascertain whether the client prefers one food at a time or a combination (e.g. meat alone, or combined with a vegetable). It is also important to ensure that food or fluids are not too hot or cold.

• Suitable utensils should be selected (e.g. a client may prefer to eat using a spoon rather than a fork). The amount of food placed on the utensil should be easily managed by the client. The utensil should be placed gently into the front of the mouth, to avoid injury or stimulation of the gag reflex.

• The food should be presented at a rate that meets the client’s needs, giving them sufficient time to chew and swallow each mouthful and to maintain dignity.

• Sips of fluid should be offered during the meal. A flexible straw, rather than a cup or glass, may be easier for some clients to manage.

• To maintain dignity and to promote independence, the client should be encouraged to be as independent as possible and may be encouraged, but never forced, to eat a meal.

• Allow the client to wipe their mouth with a serviette during the meal, or assist if necessary.

• On completion of the meal, the client’s hygiene and comfort needs should be met. The nurse should report and document the intake of food and fluid.

Key aspects related to assisting a child at mealtimes

Mealtimes in a hospital should be pleasant unhurried occasions and the environment should be one that enables the child to enjoy mealtimes. The nurse should communicate effectively with the parent/carer and child to ensure that the appropriate foods are being served. Some guidelines are:

• Mealtimes should be free from distractions

• Servings need to be small to minimise the psychological reaction to a large-sized serving

• Adequate time should be allowed for the meal to be eaten without hurrying

• The child should be prepared for the meal. Toilet needs should be attended to, nappy changed if necessary, hands and face washed, serviette or bib provided, distractions such as toys put away and the child made comfortable in bed or seated on a chair at a table. The child should be discouraged from eating in front of the television or video

• Painful or emotionally distressing procedures should not be performed immediately before or after a meal, and activities should be timed so that a child does not become too tired to eat a meal

• Meals should be served attractively, in amounts appropriate to the age and the condition of each child

• Children should be encouraged to feed themselves, even though they may do it in a ‘messy’ fashion

• Assistance should be given if the child is unable to manage or to use distractive therapy to maintain input

• Some children may need coaxing, but a child must never be forced to eat.

Uneaten food should be removed without comment and the nurse in charge informed. If the child’s illness is causing anorexia, other forms of nutrition may be offered. Refusal to eat may be an attempt by the child to gain more attention, or it may be that the foods are different in appearance, presentation, availability of condiments or timing to the meals they are used to eating. Every attempt should be made to provide nutritious foods that the child enjoys. In a clinical setting, a lot of patience may be required to assist a child to eat a healthy balanced diet, particularly if their carers are not present. The child may be apprehensive of their setting, in pain, used to different foods or their diet at home may be of a poor standard.

Children should be observed for any adverse reaction to food and the nurse in charge and/or medical officer informed if a child vomits before, during or after a meal; develops diarrhoea; or develops what may be an allergic reaction to a food, such as a rash, pruritus or breathing difficulties.

Key aspects related to assisting a client with chewing or swallowing difficulties

Some clients who experience difficulty in chewing or have dysphagia due, for example, to glossitis, stomatitis, cerebral vascular accidents or dental conditions, are at risk of malnutrition because of limitations to the types of foods they can chew and swallow safely. Clinical Interest Box 28.2 provides an example of how gastro-oesophageal reflux can affect the nutritional status of a child. Clients may require modifications to the consistency of food. Depending on the cause and degree of difficulty, the client’s needs may be met by:

• Referral to a speech pathologist to ascertain the cause of the problem by observing the client’s swallowing reflex and by investigations such as salivagrams, fluoroscopy or barium swallows

• Providing meals comprised of soft foods or thickened fluids

• Initiating the swallowing reflex by gentle pressure on the tongue with the feeding utensil

• Offering all food and fluid carefully and monitoring to avoid or detect aspiration

• Placing the food into the unaffected side of the mouth in clients with a facial paralysis (e.g. Bell’s palsy) or after a cerebrovascular accident. The nurse should ensure that food does not accumulate in the cheek of the affected side.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 28.2 Gastro-oesophageal reflux and failure to thrive

Failure to thrive is a term used in paediatrics to describe a newborn, infant, toddler or child who fails to gain weight when measured against percentile charts for age, head circumference and height. In infancy failure to thrive can be associated with mild to severe alterations in nutritional state as a consequence of numerous clinical disorders.

A common condition is gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR), which can be due to lax cardiac sphincter muscle or changes in coordination of oesophageal peristalsis. GOR can cause oesophagitis from intermittent bathing of oesophageal tissue in stomach acid. Common symptoms may also include food refusal, diminished intake, prolonged feeding times, distractibility, sleep disorders and continued crying, which may lead some to diagnose an infant as a ‘colicky baby’. Diagnosis is made by history and monitoring oesophageal pH over a 24-hour period. Treatments may include thickening agents, positioning up to 30 degrees from the horizontal, peristaltic medications and gastric acid inhibitors.

Key aspects related to assisting a client with visual impairment at mealtimes

• It is important to encourage independence; the nurse should therefore consult the client about the type of assistance that would be most beneficial. For example, clients may find it helpful if the nurse describes the meal by referring to the plate as a clock face. The nurse should state where each food on the plate may be located (e.g. the meat at 2 o’clock, the potatoes at 4 o’clock and the beans at 6 o’clock).

• To avoid injury the client should be made aware of the proximity and location of hot articles (e.g. cups of tea or coffee) and the nurse should ask if assistance to pour the fluids is required.

• If the client is unable to feed themself, they should be asked to indicate when they are ready for the next mouthful.

• Self-feeding should be encouraged at all ages to promote independence and dignity. When a client is being fed, the nurse should perform the procedure in a relaxed and confident manner, with due regard for maintaining their dignity. A variety of self-help devices are available to assist clients in feeding themselves (Fig 28.3). Such devices may be helpful for a client who has limited arm mobility, limited grasp or reduced coordination and include:

COMMON DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH NUTRITION

Although many disorders are related to a specific nutrient deficiency, the common disorders of nutrition may be classified as malnutrition, obesity, eating disorders and nutrient loss as a result of vomiting or diarrhoea.

Malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs as a consequence of continued poor nutrition status and may be described as the condition in which nutrients are being used or lost by the body in excess of the intake and absorption or utilisation of nutrients. Identifying factors that put a client at risk is an important step in ensuring that all clients have their individual nutritional needs met. People who are at risk of malnutrition include those who:

• Are experiencing increased metabolic demands or protracted loss of nutrients; for example, due to burns, surgery, inflammatory conditions or infections, vomiting, diarrhoea, physical or psychological trauma, hormonal imbalance or prolonged pyrexia

• Are not consuming oral food or fluid for more than a few days

• Have a BMI value below 20 or who have recently experienced a loss of more than 10% of their normal body weight

• Are alcohol or drug dependent

• Are receiving medications or treatments that have an anti-nutrient or have catabolic properties (e.g. immunosuppressants or antitumour agents)

• Have a disorder that results in defective digestion, utilisation or absorption of nutrients (e.g. gastrectomy, diabetes mellitus, Crohn’s disease).

Malnutrition results in impaired growth and development, lowered resistance to infection, damage to tissues and delayed healing and anaemia. Treatment includes identifying the cause and providing adequate nutrients. See Clinical Interest Box 28.3 on high rates of malnutrition in the elderly.

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 28.3 High rates of malnutrition in elderly

A ground-breaking Australian study involving UNSW revealed alarming levels of malnutrition in the elderly, with close to 80% malnourished or at risk when first admitted to hospital.

However, early intervention with a dietitian proved it was possible to dramatically reduce length of hospital stay and health costs.

The findings follow a 1-year study by a team of gastroenterologists, geriatricians and dietitians at Sydney’s Prince of Wales Hospital.

The study, led by Professor Terry Bolin of the Gut Foundation, with the Prince of Wales Department of Geriatric Medicine and Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, showed that the 80% of elderly clients admitted to hospital who were malnourished or at risk could have their hospital stay halved by implementing a nutritional care program. Professor Bolin said:

What this study has shown is that the prevalence of malnutrition among the elderly in the community is high but we have simple and effective remedies. Malnutrition has significant impact on mortality, morbidity, length of hospital stay and readmission. The benefit of early action could potentially save our health system hundreds of millions of dollars.

The study is believed to be the first randomised study of its kind examining malnutrition in a clinical setting with control and intervention groups.

Obesity

Obesity is the condition in which there is an excess of body fat, and is determined by calculating the client’s BMI or waist measurement. Obesity may result from excessive kilojoule intake, metabolic disturbances, side effects of drugs such as steroids, an inadequate expenditure of energy or from a combination of factors. Obesity may have serious consequences, including cancer, premature cardiovascular disease, breathing difficulties, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, gallbladder disease or psychosocial problems.

Principles of treatment include reducing dietary intake and any causative drugs or hormones, while planning exercise, dietary and behaviour modification and the administration of medications such as appetite suppressants, hormonal therapy or oral substances containing, for example, cellulose. Surgical intervention is sometimes indicated in instances of morbid obesity. A variety of surgical procedures is available and most are aimed at reducing the capacity of the stomach.

Eating disorders

The two most recognised disorders of eating are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Anorexia nervosa is characterised by self-imposed starvation and consequent emaciation. Body image, with a consequential loss of weight, becomes the client’s prime focus and is the result of a belief that their body is too fat, even when extreme emaciation is evident. Bulimia nervosa is characterised by episodes of ‘bingeing’ on large quantities of food, followed by purging with laxatives or self-induced vomiting.

The causes of both disorders are difficult to determine, but most experts agree that they result from an interaction of biological, psychological and sociocultural factors. Treatment, which is difficult and varied, includes behaviour modification, psychotherapy and, in some cases, hospitalisation until the desired weight is achieved.

Nutrient loss as a result of vomiting

Vomiting, if prolonged, may result in significant nutrient deficiency, dehydration and electrolyte disturbance. To correct the imbalance, oral, enteral, intravenous therapy or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) may be indicated. Vomiting is not a disease itself but is a symptom of disease and may occur as a result of:

• Diseases of the stomach, intestines, liver, biliary system, pancreas or peritoneum

• Hypersensitivity to certain foods

• Ingestion or presence of irritants

• Acidosis, either metabolic or respiratory

• Adverse reaction to, or a side effect of, certain medications

• Hormonal changes during early pregnancy

• Disturbances of equilibrium (e.g. travel sickness, vestibulitis)

• Disorders of the central nervous system (e.g. concussion, cerebral oedema, brain tumours)

• Psychological factors (e.g. apprehension, unpleasant sights or smells).

Vomiting (emesis) is the expulsion of the contents of the stomach or small intestine and is a reflex action caused by stimulation of the emesis centre in the medulla oblongata. When this centre is stimulated the glottis and nasopharynx close, the cardiac sphincter of the stomach relaxes and contractions of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles occur. As a result of the increased intra-abdominal pressure, the stomach or intestinal contents are forced upwards and are expelled through the mouth. Vomiting may be preceded by a feeling of sickness (nausea) and accompanied by salivation, sweating and pallor. In conditions such as intestinal or sphincter obstruction, ‘projectile’ vomiting may occur, in which the vomited material is ejected with great force.

Vomiting should be assessed in terms of the nature of vomiting (effortless or projectile) and the characteristics of the material vomited (vomitus). Observations made of the vomitus may assist in determining the cause of vomiting and include observations of the:

• Consistency: the vomitus may consist of fluid, partially digested or undigested food

• Colour: vomitus may vary in colour from clear to yellow, to brown or green. The presence of bile tends to colour vomitus yellow or green and may indicate propulsion of the contents of the small intestine into the stomach

• Presence of blood: blood may be present as bright red streaks or clots, or may have a ‘coffee grounds’ appearance. The latter occurs when blood has been partially digested by gastric acid secretions. Vomiting of blood is called haematemesis. Forceful vomiting may induce blood-stained vomit (e.g. Weismann’s tear)

• Odour: vomitus is usually sour smelling, but a ‘faecal’ odour indicates reflux of bowel contents due to an intestinal obstruction (e.g. paralytic ileus)

• Quantity: if possible, vomitus should be measured in millilitres to assess the amount of fluid being lost, particularly if haematemesis is present.

Key aspects related to care of a client who is vomiting

• If the client is sitting, place an emesis bowl under the chin and position a towel to protect clothes and bedding.

• If the client is lying down, lift and turn the head to one side to reduce the risk of aspiration.

• Ensure privacy, as clients will feel distressed and embarrassed by the incident.

• Ensure dentures do not become dislodged.

• The nurse should stay with the client to provide comfort and support, to ensure aspiration is recognised or prevented and to splint an abdominal wound or area of pain to reduce further pain or dehiscence of wounds, if present.

• The vomitus should be removed as soon as the episode is over to reduce the risk of a recurrence caused by the sight, smell or thought of the vomitus.

• Soiled linen or clothing should be changed and removed immediately from the room.

• Hands and face should be washed to refresh the client and to remove any vomitus.

• Oral hygiene should be attended to by cleaning teeth, plates or dentures and providing a suitable mouth rinse to eliminate any unpleasant aftertaste.

• The client should be assisted into a position of comfort and permitted to rest quietly.

• If antiemetics are ordered they should be administered by appropriate nursing staff.

• The nurse should report and document the incident so that appropriate nursing or medical actions may be implemented. An antiemetic medication may be prescribed by a medical officer and administered to reduce nausea and to prevent further vomiting.

Alternative methods to meet nutritional needs

An alternative method of meeting nutritional needs may be indicated when a client is unable to consume food or fluid orally. Alternative methods include total parenteral nutrition (TPN), intravenous therapy and tube feeding via orogastric, nasogastric, nasoduodenal, nasojejunal, gastrostomy, gastroduodenal or gastrojejunal tubes.

Total parenteral nutrition

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is sometimes referred to as hyperalimentation and it involves the parenteral administration of a complete nutritional preparation that contains high concentrations of essential nutrients and which may include intralipid solutions, containing fats. This method of feeding may be indicated when it is not possible for the client’s nutritional needs to be met via the digestive tract.

Clinical Scenario Box 28.1

Amelia, a 12-year-old girl, has been brought into hospital for an adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy. While admitting her you discover she weighs 80 kg. She is accompanied by her mother who you notice is also overweight. As a nurse in the team looking after Amelia, it is important that your care of Amelia is person centred and ensures that Amelia has the best possible health outcomes both in the hospital and on discharge.

• What are the implications that Amelia’s weight may have on her short-term and long-term health?

• Does Amelia’s weight have any implications for her pre- and postoperative care? If yes what are these concerns?

• How would you as the nurse caring for Amelia address her weight issue? Is it appropriate to also involve her parents in this discussion?

• What nursing advice would you give to Amelia and her family? How would you address an issue like Amelia’s diet, which could have health behavioural implications?

Hypertonic solutions are administered through a catheter that has been inserted into a large vein, such as the subclavian vein. The solution containing nutrients enters directly into the bloodstream. TPN solutions administered by this route provide a medium for rapid bacterial growth and, because the tubing provides access for the entry of microorganisms, contamination and septicaemia must be prevented. The catheter is inserted by a medical officer using sterile equipment and technique. Care of the equipment throughout the course of treatment requires strict asepsis.

Management of a client who is receiving TPN is the responsibility of the registered nurse (RN), and the client must be monitored continually to prevent or detect possible complications. Complications that may result from TPN include:

• Hyperglycaemia or hypoglycaemia

• Fluid and electrolyte imbalance

• Catheter-related septicaemia

• Infection of the catheter site

• Extravasation of blood from the vein as a result of catheter trauma

• The nurse may be required to assist with the care of a client receiving TPN and must be aware of the scope of their role in promoting safety and comfort.

Intravenous therapy

Intravenous therapy involves the introduction of a solution or solutions into a peripheral or central vein. Information about intravenous therapy is provided in Chapter 22.

Enteral tube feeding

Naso-enteric tubes are orogastric, nasogastric, naso-duodenal or nasojejunal tubes used to administer a range of nutritional feeds to a client for a variety of reasons, including:

• Malabsorption (e.g. inflammatory bowel disorders)

• Surgery (e.g. oral or throat surgery)

• Central nervous system disorders (e.g. paraplegia, unconsciousness, pharyngeal paralysis)

• Metabolic disorders (e.g. hyperinsulinaemia, hypoglycaemia)

• Food refusal or dysphagia, when the client is too ill or weak to eat normally.

The nurse should be aware of the policies and regulations regarding their role and responsibilities in checking the location of the tip of the enteral tube, and infection-control policies, in their healthcare setting. For information on insertion of a nasogastric tube see Procedural Guideline 28.1.

Procedural Guideline 28.1 Inserting a nasogastric tube

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Validate the medical orders in the client record | Ensures correct procedure is about to take place |

| Explain the procedure to the client | Reduces anxiety and gains client’s consent and cooperation |

| Critically think through your assessment data and problem solving, e.g. provide privacy, comfort measures, pain relief | Evaluating each aspect and its relationship to other data will help identify specific problems and modifcations of the procedure that may be needed for the individual |

| Prepare equipment | |

| Locate and gather the equipment including suction equipment or equipment related to providing nutrition as indicated prior to beginning the procedure. In addition to the tube, you will need the following: | Ensures all equipment is at client’s bedside to maximise effciency, reduce apprehension on the client’s part and increases the confidence in the nurse |

| Assist the client into the high Fowler’s position unless contraindicated | Facilitates tube insertion and reduces risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux and aspiration |

| Perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross infection and contamination of tubing |

| Don appropriate equipment and clothing as per infection control protocols | Minimises risk of cross infection |

| Implementation | |

| Explain the procedure and why it is needed | Ask the client if either nostril is obstructed (history of broken nose, deviated septum or nasal surgery) |

| Raise the bed to the appropriate working position based on your height and assess the client’s nostrils | Asking the client to breathe through one nostril while occluding the other will help ascertain if one nostril has an occlusion |

| Measure the portion of tube to be inserted by extending it from the tip of the client’s nose to the earlobe and from the earlobe to the xyphoid process | Determines the insertion length of the tube to ensure the tube is inserted an adequate distance so that the distal tip rests in the stomach |

| Mark the tube with tape at this point | |

| Lubricate the first 6–10 cm of the tube with water-soluble lubricant. Note: Some small-bore tubes self-lubricate when dipped in water | The use of lubricant will ease insertion by decreasing friction |

| Grasp the tube with your right hand and gently insert it into the nostril, guiding it straight back along the foor of the nose. Have an emesis basin and tissues in the client’s lap | Insertion of the NGT can stimulate the gag reflex |

| Next, ask the client to tilt the head slightly forwards | Flexing the head forwards allows the tube to follow the posterior wall of the nasopharynx and enter the oesophagus rather than the trachea |

| Have the client swallow while you gently but steadily advance the tube. DO NOT gives sips of water as the tube is being inserted | The muscular movement of swallowing helps advance the tube |

| When the tube has been advanced as far as the tape marker, secure the tube to the client’s nose using tape or the adhesive bandage | Ensures the tube does not move out of the stomach |

| Check for proper placement of the tube. Follow the protocol for the techniques required at your facility (auscultation, aspiration, x-ray) | Ensures the tube is in the correct location and not in the trachea |

| Increases the client’s psychological comfort and reduces the material that can be media for growing bacteria | |

| Report and document the procedure and any complications | Documentation increases the communication between healthcare professionals and complies with legal requirements for reporting change |

Nasogastric tubes

Feeds given by a nasogastric tube inserted via the nares into the stomach (Fig 28.4) are normally administered to clients who experience short-term difficulties in nutrition, or when surgically placed tubes such as gastrostomy tubes (see below) may be contraindicated by the client’s physical condition.

Nasoduodenal and nasojejunal tubes

Tubes placed into the duodenum or jejunum are used for clients with gastric disorders that contraindicate gastric placement, such as severe reflux, partial or total gastrectomy and malabsorption.

Gastrostomy tubes

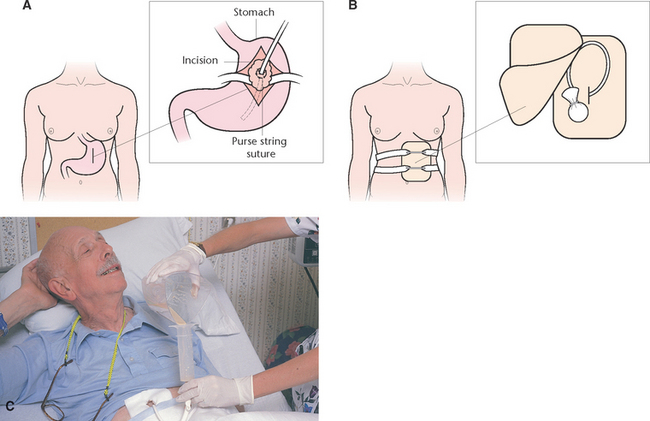

Feeding via a gastrostomy tube may be indicated if there has been recent surgery or an obstruction in the upper part of the digestive tract, or as a long-term treatment for feeding difficulties. A gastrostomy tube is a hollow tube, often composed of silicone, inserted through the abdomen into the stomach by a surgeon either through an external approach, via an incision through the abdominal wall, or endoscopically via the mouth through the stomach and through the abdominal wall. The opening around the tube may be sutured to prevent leakage or accidental removal (Fig 28.5) or held in place by the use of an inflatable balloon and a flange or similar device that applies pressure to hold the tube against the inside wall of the stomach.

Figure 28.5 Gastrostomy feeding. A: Gastrostomy incision and procedure. B: When not in use the end of the tube is covered by sterile gauze then covered by a pad held in place with straps. C: Pouring the feeding formula into a syringe connected to the gastrostomy tube

(C: deWit 2001, 2005)

Gastrostomy (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)) and jejunostomy (percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ)) devices are used for long-term nutritional support, generally more than 6–8 weeks (Berman et al 2012). Fluid enteral feeds are normally introduced 24 hours later through the tube, into the lumen of the stomach, duodenum or jejunum. Some tubes may require replacement to prevent or treat occlusion or disintegration; long-term silastic tubes may be left in situ indefinitely. In the event of accidental tube removal, the client should have a Foley or Malecot catheter available, to enable a medical officer to ensure the stoma’s patency and continuity of feed.

Prepared enteral feeds are administered either by:

• Intermittent or bolus feeds, in which a solution is administered at regular intervals (e.g. every 4 hours). Administered to clients who are able to tolerate volumes at a rate they could normally drink orally. A syringe or giving set is attached to the end of the nasogastric tube and filled with the feed or fluid, which is allowed to flow in slowly by gravity or by the use of an enteral feeding pump. The rate of administration can be adjusted; for example, by the height at which the syringe or set is held at, or by adjusting the enteral pumping rate; or

• Continuous feeds, in which a gravity infusion set or a controlled enteral feeding pump is used that can deliver the fluid at a regulated rate over a predetermined time. Continuous feeds are administered to clients who have experienced difficulty in tolerating bolus doses, or for clients with malabsorption, reactive hyperinsulinaemia, diarrhoea or other metabolic problems.

Depending on the institution and the nutrition required, the enteral feed may come pre-packaged, for example in cans, and will not require refrigeration, while other solutions stored in containers such as waxed cardboard or made in-house do require refrigeration.

The nurse should be aware of the policies and regulations in their healthcare setting regarding their role and responsibilities in checking the location of the tip of the nasogastric tube (see Procedural Guideline 28.2).

Procedural Guideline 28.2 Care required before starting an enteral feed

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

Care specific to gastrostomy type tubes

For clients who may be discharged home or to encourage independence with enteral tubes in situ, the client may be taught how to test, administer and perform the care required independently. Part of the education involves discussing some of the complications and how to deal with them, as described below.

Care and cleaning of gastrostomy tube and equipment