CHAPTER 21 Hygiene and comfort

At the completion of this chapter and with further reading, students should be able to

• State the significance of personal hygiene to the maintenance of health

• Identify factors that influence hygiene practices

• Identify complications that may result if personal hygiene is neglected

• Perform nursing procedures for client hygiene accurately and safely

• Identify the factors that may interfere with client comfort

• Identify the importance of a well-made bed and comfortable positioning of clients to the promotion of health and wellbeing

• Apply appropriate principles to select supplementary equipment used in conjunction with bed making

• Apply appropriate principles when planning and implementing measures to promote comfort

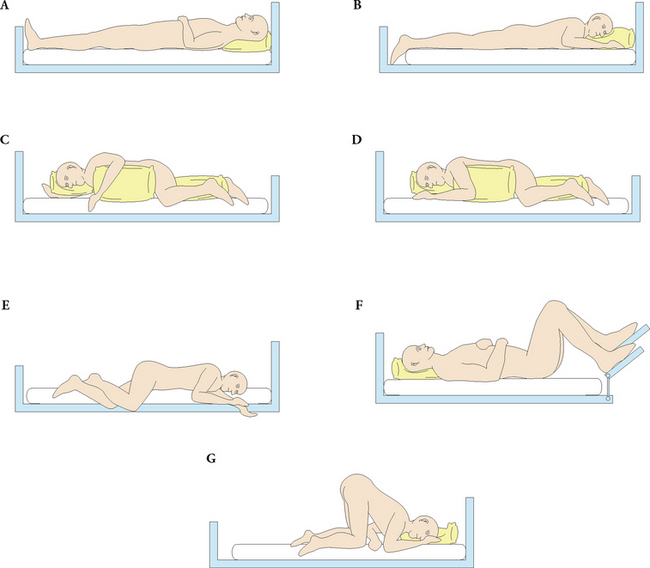

• Describe the positions that clients may be required to assume in bed

Hygiene is the science of health. It has also been described as the self-care by which people maintain cleanliness that is conducive to the preservation of health. Personal hygiene includes activities such as bathing, toileting, general body hygiene and grooming (Parker 2012). Hygiene helps the individual to maintain a positive body image and helps protect the body against disease such as infection.

Comfort is often associated with compassionate care and many nursing interventions are implemented to provide comfort (Bourgeois & Van der Riet 2012). Comfort is subjective and may also be described as a feeling of ease or wellbeing; for people to feel comfortable their physiological, psychological and spiritual needs must be met. This chapter introduces the nurse to the knowledge and skills required to assist clients with their hygiene and physical comfort needs.

‘The nurse came into my room this morning to ask me if I wanted to have a shower. I told her that I felt a bit tired and asked if we could we leave it for an hour or two; I hadn’t slept very much as I am worried about how I will manage at home. The nurse then looked at her watch, sighed heavily and said she would come back later. I wonder if she realises that I now feel like a burden and that she will be inconvenienced if she has to shower me in a couple of hours. I think I will leave my shower until later in the day after she has gone home.’

John, aged 82 years, day 3 following the surgical repair of a fractured neck of femur which he sustained after falling at home

Many factors influence whether or not a client is comfortable; they relate to physical, emotional and spiritual needs being met. To most people, physical comfort means being clean, dry, warm and free of hunger and pain. Emotional comfort relates more to being relatively free from stress and feeling satisfied with interpersonal relationships; in particular, people are more likely to be emotionally content when they feel loved and are able to love others. Spiritual comfort is connected to a sense of purpose and satisfaction in life that may or may not be entwined with religious meaning. The nurse considers all these interrelated elements when caring for clients’ comfort. This chapter discusses the physical elements of comfort, specifically in relation to hygiene care and moving and positioning clients. Management of pain is discussed in depth in Chapter 31. (Information about assisting clients with stress and spiritual comfort is provided in Chs 25 and 37.)

FACTORS AFFECTING PERSONAL HYGIENE

Personal hygiene refers to the measures people take to keep their bodies clean. Neglect of personal hygiene can have a detrimental effect on physical and psychological health and the comfort of an individual. Many factors influence people with regard to personal hygiene practices. It is important for nurses to appreciate that emphasis on cleanliness varies according to an individual’s personal preference, cultural, religious values and lifestyle. Other factors that may affect an individual’s hygiene practices include:

• Physical and intellectual capabilities

• Knowledge of the significance of hygiene

Nurses should respect individual preferences and cultural norms and, whenever possible, enable clients to follow their usual routine of personal cleansing (Berman et al 2012). For example, if a client prefers to shower in the evening rather than the morning, or to shower every second day, these practices are best continued. Maintaining routine and normality can help limit the stress during times of illness.

Many clients will be able to attend to their own hygiene, while others will require partial or total assistance from the nurse. Some clients, for example, those who are unconscious, will be unable to participate in planning their own hygiene care. In these instances, it is the responsibility of the nurse to ensure that suitable nursing care plans are devised to meet hygiene needs. Assessing clients’ abilities to care for their own hygiene needs safely and effectively includes identifying factors such as loss of balance, poor vision, decreased sense of touch or limitations in mobility. In the case of some older people with dementia, the ability to remember, plan and carry out self-care activities will need to be assessed. It is important for the nurse to recognise that an inability to care for personal hygiene needs without assistance and the lack of privacy that accompanies intervention by another person can be very embarrassing for the client. The associated loss of independence can have a negative impact on the client’s feelings of self worth; they may feel that they are a burden to the nurses. A calm, sensitive, caring and professional approach can help reduce these feelings. Wherever care is provided, the nurse’s role is to ensure that the client maintains high standards of personal hygiene for efficient body function and sense of wellbeing. It is important for the nurse to be aware of the function and care requirements of areas such as the skin, hair, mouth, eyes, nose, ears and nails to help clients maintain high standards of personal hygiene in each of these areas. Assisting with hygiene provides an ideal opportunity for the nurse to observe and assess the client for any abnormalities or changes in health status. It also provides a time to talk informally and privately together, which can provide the nurse with insights about the client’s psychological and spiritual wellbeing. The nurse must, on every occasion, seek the consent of the client before starting to provide any personal care and assistance.

SKIN AND SKIN CARE

The skin is the largest organ of the body. It is a semi-permeable layer that protects underlying tissues and organs from injury or invasion by microorganisms. It is waterproof, controls the rate at which water is lost from the body by evaporation, helps regulate body temperature and produces keratin, melanin, sweat and sebum. The skin also plays an important role in perception of sensation through the sensory nerve endings it contains, which are sensitive to touch, pressure, pain and temperature (Crisp & Taylor 2009). (See Chs 27 and 32 for more information about the skin and sensory abilities.)

If the skin is not washed regularly dirt, sebum, dried sweat and dead skin cells collect, providing an ideal medium for the growth of bacteria and fungi. Bacteria decompose the dirt and dried sweat producing an unpleasant body odour, and infections such as boils are more likely if the skin is not cleansed adequately.

Skin undergoes many changes during a person’s life span and, as a result, care needs may vary according to the client’s age or stage of development. In addition, characteristics of normal skin may vary according to ethnic or racial background.

Infants

In infancy, the skin is thin and easily blistered or excoriated by friction, acid or alkaline substances. It is very sensitive to heat or cold, so it is vital that the temperature of bath water is tested before bathing; approximately 38°C is recommended as the newborn’s skin is prone to irritation (Gunn 2010). Mild, non-irritating soaps or soap-free solutions may be used on the skin and, as the infant has no bladder or bowel control, thorough cleansing of the genital and anal areas is necessary to prevent excoriation. After washing, the infant’s skin should be patted dry with a soft towel, paying particular attention to skin creases and folds. Cradle cap is a common form of dermatitis of infants which consists of thick, yellow waxy scales on the scalp, which may occur as a result of an accumulation of sebum. It can usually be prevented by regular gentle washing and drying of the scalp and hair (Barker 2009; Pantley 2003).

Adolescents

Adolescence is accompanied by many changes that are due to hormonal activity. Sweating from the axillae usually occurs at this stage and the adolescent may need education concerning the importance of having a regular shower or bath. Education can also include information about the function of deodorant and antiperspirant (Berman et al 2012). Acne is a common problem as sebaceous glands become more active in adolescence. Skin hygiene, together with a balanced diet, is important in preventing secondary skin infections.

The middle years

Middle age is often associated with further skin changes, particularly during the male climacteric (decreased levels of androgens) or the female menopause—because of a decrease in circulating ovarian hormone levels (primarily oestrogen and progesterone) the skin may become drier and the pubic and axillary hair may become sparse. Some women may experience thinning and dryness of the skin of the external genitalia, which may be accompanied by pruritus (Berman et al 2012). Lubricants are available to reduce any discomfort associated with such changes.

Older adults

Older age is associated with increasing change in the dermis, with the result that skin is thinner, less elastic and dry. The decreased production of sebum and associated dryness mean that the skin of older people is less able to tolerate soap. To help counteract the dryness, a mild soap or soap-free washing lotion can be used and a moisturising lotion applied after a bath or shower. To prevent skin irritation caused by dry skin some older people choose to change from a daily shower or bath to every second day or less frequently (Clinical Interest Box 21.1).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 21.1 Hygiene and the elderly

I have noticed over the last couple of years that my skin feels and looks significantly dry. My local pharmacist recommended that I use a soap-free cleanser in the shower and suggested that I apply moisturiser to the dry, flaky skin after I wash. She also suggested that I shower every second day and just have a quick wash at other times.

Mrs Anderson, aged 76

Cultural considerations

A client’s cultural beliefs and personal values may influence hygiene care. People from diverse cultural backgrounds follow different self-care practices. In many cultural groups in Australia, it is common to bathe or shower daily, whereas in some other cultural groups it is customary to bathe completely only once a week (Berman et al 2012).

Culture plays a role not only in hygiene practices and preferences but also in sensitivity to personal space; for example, some Chinese people may view tasks associated with closeness and touch as being offensive or impolite (Crisp & Taylor 2009). The nurse should ask the client what would make them feel most comfortable during a bath. Perhaps they would prefer only a partial bath from the nurse, with a family member assisting with the bathing of more private body parts. The client may also want to defer part of the hygiene. If, in the nurse’s judgment, hygiene is critical to prevent problems, such as skin breakdown, the nurse must try to understand the client’s concerns then help them understand the reason for accepting the nurse’s intervention. The nurse can play a very important role, particularly when caring for patients in rural settings, poor patients and older adults, in being able to screen for abnormalities such as dental decay and referring dental problems to a dental professional.

Hair care may also be important to people from other cultures. When caring for patients from different cultures, it is important to learn as much as possible from them or their family about preferred hair care practices. Cultural preferences may also affect how hair is combed and styled (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Nursing observations of the skin

The skin should be observed for:

• Colour. Particular note should be taken of any abnormalities such as pallor, jaundice, cyanosis or altered pigmentation. Areas of red, deep pink or mottled skin that do not become paler with fingertip pressure may be a sign that a pressure ulcer is developing. (See Ch 27 for information on the development and prevention of pressure ulcers.)

• Hydration. Deviations from normal include excessive dryness or oiliness, increased sweating and fluid retention (oedema)

• Texture. The skin may be smooth and supple or contain rough scaly patches. It is also important to observe if the skin appears thin and fragile

• Turgor. Picking up and then releasing a small fold of skin is the simplest way to assess skin turgor. Adequately hydrated skin returns rapidly to its previous state, whereas the skin of a client who is dehydrated is slow to respond. The skin of an older client may also resume its shape more slowly because of reduced elasticity

• Lesions. The skin should be observed for the presence of bruises, blisters, inflammation, rashes and localised swellings such as cysts, petechiae, bites, scratch marks or puncture marks.

Abnormalities and changes should be reported and documented and appropriate nursing care implemented in response to nursing observations.

Care of the skin includes maintenance of cleanliness and protection from injury. The skin must be protected against injury by gentle handling and the use of appropriate bed linen and equipment. Cleansing involves the use of soaps and lotions that do not cause irritation or dryness and careful drying of the skin, particularly in folds or creases. If the client wishes, and it is not contraindicated, deodorants, powders and perfumes may be used to enhance the feeling of freshness and to improve morale. Cleansing of the skin may be achieved by several means and the method selected depends on the client’s level of mobility and independence. Some clients will be able to have a bath or shower, while more dependent clients may require a bed or trolley bath. Whichever method of cleansing is used the nurse must ensure the client’s privacy, comfort and safety. It is now sometimes a reality that male and female clients are accommodated in the same ward or unit area and some even share bathroom and toilet facilities. This can increase the client’s discomfort and concerns about privacy, especially during hygiene and toileting procedures. The nurse will need to be sensitive to the concerns of clients faced with this situation and reassure them that every effort will be made to maintain their personal privacy (Crisp and Taylor 2009; deWit 2009; Springhouse Staff 2007).

BATHING AND SHOWERING

A client may have either a bath or a shower, depending on individual preference and general condition. Both methods of cleansing refresh the client, stimulate circulation and promote relaxation. They also provide an opportunity for the nurse to observe the condition of the client’s body, including assessment of mobility and strength.

Nursing observations and assessment

If clients are able to attend to personal hygiene needs safely and independently, they may be left to bathe in private. It is the responsibility of the nurse to ensure that the bathroom has been prepared for use and that the client has all the necessary items. The nurse should ensure that the client knows where the call bell is located and that they know how to use it to call for a nurse.

It is the nurse’s responsibility to assess how much assistance a dependent client requires. Some clients may require help with transfers, while others will require the nurse to remain with them throughout the entire procedure. The nurse should remain with, and provide assistance for, any client who is weak, frail, unsteady or confused. Some clients may require a shower chair to sit on during the shower. For example, a chair would be helpful for a postoperative client who can walk to the shower but is at risk of becoming easily fatigued.

Devices used to assist when bathing and showering

There are several other devices designed to assist the nurse when providing hygiene care for clients. These include handrails, bath seats, mechanical hoists, mobile baths and shower trolleys.

Grab (hand) rails fixed to the wall at the side of the bath or shower can be used for support by clients who are able to stand. Bath benches or seats fit across the top of a bath and allow the client to shower using a hand-held shower hose.

Lifting devices such as hoists or standing machines may be used to safely transfer non-ambulatory clients onto a mobile shower chair so that they have the opportunity to shower or bathe. It is generally easier to remove the client’s clothing before the lift and transfer to the bathroom, but being moved around in a lifting device can feel extremely undignified and distressing. It is recommended in the policy of many institutions that hoists and standing machine transfers be used by two nurses to ensure maximum client safety. For further information regarding safe transfer of clients, refer to www.worksafe.vic.gov.au. The utmost care must be taken to ensure that the client’s privacy and dignity are maintained, in particular the client’s private body areas must be securely covered from view during transfer to the bathroom. Any client who requires the use of a mechanical lifting machine must never be left unattended in the device or in the bath. Clients who may require the use of a mechanical lifter include those who are heavy or extremely weak, frail or helpless.

When clients require aids in the home, structural alterations to the house may be necessary to facilitate their use. Government-funded care packages sometimes provide for this need. In some situations, nurses teach family members who are providing home-based care for dependent relatives how to use the hoist safely. (See the Australian Department of Health and Ageing at www.health.gov.au.)

Mobile baths are available in some healthcare facilities. A mobile bath can be moved to the client’s bedside. The client is transferred from the bed into the bath and transported to the bathroom. The bath is filled and the client bathed in the usual manner.

Shower trolleys are designed for use in the normal shower area. Using a hoist, the client is positioned onto the trolley and wheeled to the bathroom. The surrounding edge is inflated and converts the trolley into a shallow bath and the nurse washes the client using the shower hose.

A full explanation about the aid being used, reassurance about its safety and maintaining the client’s personal privacy and dignity during use are important components of reducing stress and embarrassment for the client. Examples of some aids that are available are illustrated in Figure 21.1.

Figure 21.1 Devices to assist bathing and showering. A: Mechanical lifting device. B: Shower chair. C: Handrails attached to the walls in the shower and toilet. D: Hand-held shower. E: Shower trolley

(A: Reproduced by permission of Haycomp Pty Ltd; B: © Lisa F. Young/Shutterstock; C: Copyright 2012 J.B.S.I—Custom Medical Stock Photo, All Rights Reserved; D: © B. Brown/Shutterstock; E: Image supplied by Hills Healthcare Equipment www.hillshealthcare.com.au)

Key aspects of assisting a client to bathe or shower are outlined in Procedural Guideline 21.1.

Procedural Guideline 21.1 Assisting a client to bath or shower

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

Clients requiring special consideration

Clients who are weak, frail, unsteady or confused will require the nurse’s assistance to bathe or shower. A client may feel faint and collapse in the bath or shower. If this occurs the nurse should immediately drain the bath or turn off the shower. Towels should be used to cover the client for warmth and dignity and extra towels should be placed under the client’s legs and feet to increase venous return. The nurse should summon immediate assistance and remain with the client, ensuring that the airway is clear. (See Ch 42 for full emergency care actions in situations in which a person has fainted.) Clinical Scenario Box 21.1 discusses the hygiene needs of a client following a stroke.

Clinical Scenario Box 21.1

Mrs Joan Bennett is a 68-year-old woman who was admitted to hospital 10 days ago following the sudden onset of left-sided arm and leg weakness. She has been diagnosed as having a right-sided stroke and has moderate weakness down her left side.

Mrs Bennett says that she knows she has had a stroke but insists that she can attend to her own hygiene needs; she prefers to shower daily in the evening when she is at home.

Mrs Bennett is right handed so is able to assist the nurse with washing herself but she tends to only wash her chest and right leg; she forgets to wash the left side of her body unless prompted to do so by the nurse.

She requires supervision with ambulation as she is unsteady on her feet; the physiotherapist has provided her with a walking frame which she has reluctantly agreed to use. She says she prefers to walk unassisted as she is very independent. She needs to be reminded to walk with supervision as she has been found in the bathroom alone on several occasions attempting to get into the shower. She needs to sit down when showering in order to prevent a fall.

Mrs Bennett also requires assistance with dressing due to her left-sided weakness.

• What would the nurse need to do to ensure Mrs Bennett’s safety during the showering process?

• What actions would the nurse take to allow Mrs Bennett to remain as independent as possible with her hygiene care?

• How would the nurse assist Mrs Bennett to be as independent as possible with dressing?

• Apart from the physiotherapist, which other members of the healthcare team would be involved in the care of Mrs Bennett?

• What hygiene equipment could the nurse use to assist Mrs Bennett in the shower?

Some clients will require special consideration when bathing or showering; for example, special attention is needed for clients who have drainage or intravenous (IV) tubing, wound dressings, plaster casts or specific skin disorders. There may also be special needs associated with surgical or other interventions.

A client with dementia

Difficulties often arise when bathing clients who have dementia. The nurse can reduce their discomfort by avoiding running water over their face, maintaining warmth and keeping them covered as much as is practicable. Keeping routines and giving clear, simple instructions, cues or demonstrations, and allowing the client as much independence as possible will also allay the anxiety associated with bathing (Berman et al 2012). Music, singing or talking during bathing may distract the client from fretful reactions and improve the experience. It is necessary to check the water temperature prior to washing the client. The skin of the older person may be more sensitive to temperature extremes due to deterioration in control mechanisms such as vasodilation and vasoconstriction (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

A client with a skin disorder

Soap-free cleansers are best used on clients with any dryness, erythema or pruritus, with care taken to follow any medically prescribed treatments. Emollient creams or lotions may also need to be applied following bathing. Where the application of medicated creams or lotions is required, gloves should be applied before they are administered because they are absorbed through the skin.

A client with an intravenous line

Care is necessary to avoid kinking or dislodging IV tubing and precautions must be taken to prevent the intravenous site becoming wet. Pumps should be switched to battery mode when the client is showering. The nurse will need to assist the client to change their clothing. Remove the client’s gown or pyjamas. If an extremity has reduced mobility or is injured, begin removal from the unaffected side, then lower the IV container or remove from pump and slide gown covering affected arm over tubing and container. Rehang the IV container and check the flow rate or reset the pump rate. Do not disconnect the IV tubing.

A client with a urinary catheter or wound drainage tubing

Drainage tubing and the container receiving the drainage fluid must be positioned below the area into which the tubing is inserted in order to promote drainage and to prevent backflow of fluids into the body. For example, a urinary catheter bag should not be raised above the level of the client’s bladder.

Bathing the client in bed

Clients who are confined to bed or whose condition does not enable them to have a bath or shower may be provided with equipment for washing in bed, or may be given a bed bath (also referred to as a sponge) by the nurse. If clients are able to wash unaided, they are provided with all necessary items, the upper bedclothes turned down and a towel placed over them for warmth and privacy. The nurse will need to help with washing and drying the back and any other parts of the body the client is unable to attend to independently. When the bath is completed and the client’s hair and teeth have been attended to, the nurse remakes the bed.

A complete bed bath involves washing the entire body of a client in bed. It is performed by the nurse when a client is unable to wash unaided. Clients who may require a bed bath include those who have a debilitating illness or are paralysed or unconscious. A bed bath is also frequently needed after surgery. Depending on the client’s level of mobility, either one or two nurses perform the procedure. Healthcare facilities commonly adopt their own specific guidelines concerning how to perform a bed bath. An alternative to the traditional sponge bowl method is the bag bath method (see Clinical Interest Box 21.2).

CLINICAL INTEREST BOX 21.2 Bag bath method of washing a client in bed

This method involves the use of a bag containing 10 pre-moistened disposable cloths, each one used for a different area of the client’s body. A bag bath is convenient because it is easy and quick to prepare by warming in the microwave for about 1.5 minutes. After washing, the skin is allowed to air dry so that moisturisers contained in the cloth can remain on the skin. Clients who have mild–moderate skin conditions have reported improvement with consistent use of this method (Bauer 2009). However, they are an expensive option and are not used as commonly as other methods.

The following description of conducting a bed bath explains a more common approach. The basic equipment required for a bed bath is:

• Soap or soap-free alternative

• Disposable gloves (when risk of contacting body fluids)

• Items for oral hygiene (e.g. toothbrush, toothpaste, dental floss, denture cup, water)

Key aspects related to performing a bed bath or sponge are:

• Throughout the bed bath the nurse should promote the privacy, safety and comfort of the client, while ensuring that all hygiene needs are met

• During the bed bath the nurse assesses the status of the client’s skin, hair, nails and level of mobility. The bed bath also provides time to talk with the client without interruption and it is often during this time that issues of concern are raised

• Clients should be encouraged to help themselves as much as they are able, to promote independence

• Clients who have not been bathed in bed before may be embarrassed about the exposure of their bodies and their loss of independence. It is the responsibility of the nurse to demonstrate sensitivity and to ensure adequate privacy throughout the procedure. The client’s privacy and warmth is maintained by exposing only the area that is being washed: this is achieved by using a dry towel to cover other areas of the client’s body

• The nurse who is to perform the bed bath must be aware if there are any limitations of movement or positioning for the client. For example, a client who has had a total hip replacement must not lie on the affected side until the surgeon has given their approval (Childs & Wyllie 2008) and a client who is experiencing difficulty in breathing may need to remain sitting up throughout the bed bath to prevent further respiratory distress

• During the bed bath, the client’s joints should be put through the full range of motion, unless this is contraindicated. Movement improves circulation, maintains joint mobility and preserves muscle tone

• When dressing a client who has some impairment of an arm or leg (e.g. paralysis), the affected limb should be placed into the garment first so that maximum use may be made of the flexibility of the unaffected limb

• If a client is experiencing pain (e.g. after surgery) ensure that prescribed analgesia is given before the bed bath is performed; make sure you allow sufficient time for the analgesia to take effect prior to commencing the procedure

• Ensure that the water is the correct temperature and changed throughout the procedure when it becomes cool, too soapy, dirty or after washing the genital area

• If clients have a range of movement that permits it, when cleaning nails it may be helpful to place their hands and/or feet in the bowl of water. This is more refreshing for clients and enables the nails to be cleansed more effectively

• Ensure that all soap is rinsed off the skin, as residual soap may cause dryness

• Special care should be taken to ensure that all skin folds and creases are washed and thoroughly dried; for example, under breasts, in the groin area between the buttocks, between fingers and toes. If these areas are not dried properly the skin may become excoriated and painful

• Throughout the bed bath the client’s skin should be observed for areas of redness, breaks, bruises and other deviations from normal. Deviations should be reported and documented. Nursing measures should be implemented as appropriate

• If the client has an indwelling urinary catheter or has had certain types of gynaecological surgery, it is important to thoroughly clean the perineal area in order to prevent vaginal or urinary tract infection.

The complete guidelines for performing a bed bath are provided in Procedural Guideline 21.2.

Procedural Guideline 21.2 Performing a bed bath

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Offer the client use of toilet facilities before starting the procedure | Helps promote comfort during the procedure |

| Clear the top of the locker or over-bed table | Provides space for bath equipment |

| Shut windows and doors and/or draw the screens around the bed and close blinds | Promotes privacy and warmth |

| Adjust the bed to a suitable height | Facilitates the procedure and prevents strain on the nurse’s back |

| Assemble all the items necessary at the bedside | Nurse must remain with the client throughout the procedure |

| Ascertain whether the assistance of a second nurse or a mechanical lifting device is necessary | Promotes comfort and safety |

| Perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Remove the upper bed covers and place them on a chair. Place a towel over the client | Facilitates the procedure and promotes warmth and privacy |

| Remove the client’s upper nightclothes | Exposes the body for adequate cleansing |

| Position the client lying back on one or two pillows, unless contraindicated | Allows a relaxing position, facilitates the procedure and prevents it from causing discomfort or distress |

| Begin to wash and dry the client (using one towel to protect the bedclothes) in the following suggested order: | Logical progression that ensures that all areas of the body are washed |

| Roll the client onto one side of the bed to wash the back. Straighten or replace the bottom bed sheets | Avoids moving the client again unnecessarily |

| Roll the client onto the other side and fit the bottom sheet into position over the mattress | To complete making the bottom part of the bed |

| Dress the client in clean nightclothes | Promotes warmth and comfort |

| Replace pillows and assist the client into position | Promotes comfort |

| Attend to the client’s hair and oral hygiene and a facial shave if necessary | All hygiene needs must be attended to |

| Replace the upper bedclothes and remove the towel | Promotes comfort and warmth |

| Replace equipment (e.g. the client’s personal items in the locker, and the signal device in easy reach) | Ensures that the surroundings are tidy and that client has easy access to their belongings |

| Infection control | |

| Note client’s response, document the procedure and report observations | Appropriate care can be planned and implemented |

Perineal care

Many clients prefer to wash their own perineal area and privacy should be provided for them if they are able to do so. The nurse may provide a degree of privacy by holding the covering towel or sheet up and away from the client’s body, forming a tent while the client washes their genital area beneath it. If the client is unable to wash the perineum independently, the nurse is advised to put on gloves and place a waterproof sheet (often referred to as a ‘bluey’) under the client to protect the mattress. Only the area to be washed should be exposed. If faecal material is present it should be enclosed in a fold of the bluey or tissue and removed with disposable wipes. The anus and buttocks are then cleansed and dried and the soiled sheet removed and replaced with a clean one. The perineum should be washed and rinsed thoroughly and patted dry. Care should be taken to wash a female client’s perineum from front to back to minimise the risk of contamination from the anal area. Frequent hygiene care may be needed for menstruating women. If needed, a fresh sanitary pad should be put in place at the completion of the perineal wash.

Care should be taken to retract the foreskin of uncircumcised adult male clients so that the head of the penis can be cleaned effectively. Once the area is cleaned, the foreskin should be returned to its natural position. The scrotum should be lifted and the area below washed, rinsed and dried thoroughly. Retraction of an infant’s or child’s foreskin is not recommended. The foreskin is resistive to retraction until separation of the foreskin and glans penis occurs naturally at about age 3–5 years. After this it is recommended that the child’s foreskin be checked only very occasionally for retraction. Therefore, under normal circumstances the nurse will not need to retract the foreskin of children during their hygiene care. However, if the tip of a child’s penis shows signs of irritation this should be reported and documented.

If there is a urinary catheter in situ, the area around it should be carefully washed with unperfumed soap (or alternative) and water. When the perineal wash is completed the underpad is removed, all washers must be immediately disposed of and the client made comfortable.

Providing intimate care can cause embarrassment to the nurse and to the client, but this should never result in personal hygiene being neglected. A professional, dignified and sensitive manner can help with uncomfortable feelings (Crisp & Taylor 2009; deWit 2009).

Bathing an infant

Bath time should be an enjoyable occasion for the infant and the bath should be completed as quickly and safely as possible because prolonged exposure may cause the loss of body heat (Berman et al 2012). Preparation for a bath includes:

• Ensuring that the room is warm and draught-free

• Assembling all the items required: baby bath half-filled with water at 38°C, bath thermometer, two towels, a face washer, cotton wool swabs, a mild, soap-free cleansing lotion, a clean set of clothing and nappies, clean linen for the cot, a receptacle for soiled linen and a gown or apron

• Preparing an area (e.g. place a towel on the bench or table beside the bath) on which the infant can be placed while being undressed, dried and dressed.

The procedure for bathing the infant is as follows:

• Wash hands and put on gown or apron

• Undress the infant, except for the nappy, which is left on

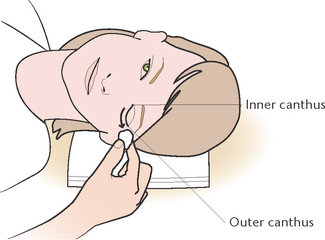

• Wrap the infant in a towel, and wash the face with cotton wool swabs moistened with warm water. Care should be taken to wash the eyes from the inner to the outer canthus (corner) (Pisani et al 2009). Items such as cotton swabs should not be inserted into the nose or ears. The inside of the ears should be left alone, but the outer ear should be cleansed with moistened cotton wool. Pat the face gently to dry.

• With the infant on the bench, unwrap the towel and remove the nappy. The infant should be washed in a top-to-toe direction, turning the surface of the washcloth as the bath progresses. The genitalia should be washed from front to back to prevent faecal matter from coming into contact with the urethra, as this would risk the onset of a urinary tract infection. A mild soap may be needed for heavily soiled areas. Alkaline soaps should be avoided because they alter the pH of skin. Particular attention should be paid to the skin folds, axillae, groin and between the fingers and toes and under the chin where food accumulates. The infant must always be held firmly but gently with the dominant hand and never left unattended. Lowering the infant slowly into the water avoids startling

• The infant should be allowed some time to splash and kick in the water

• The nurse then lifts the infant from the bath and returns the infant to the prepared bench. The infant is dried quickly but thoroughly. Where skin areas come in contact with each other there is a possibility of chafing, and particular care is needed when drying these areas: the use of baby powder is not recommended because it may irritate the respiratory tract (Leifer 2007)

• The infant is then dressed before becoming cold

• The nurse reports and documents anything of concern relating to the infant.

As the infant grows rapidly in the first 12 months, the procedure is adapted to suit the child’s developmental level and as the child grows, most of the actual washing is done in the bath, with the nurse supporting the infant as needed. Infants and young children must never be left unsupervised in a bath. Nurses have an important role in providing support and reassurance for new mothers, particularly when instructing them how to bathe their babies.

HAIR CARE

Hair care is very personal and the appearance of the hair can indicate a person’s general health status (Parker 2012). Hair that is well groomed generally promotes a positive body image. Hair that is not washed and brushed tends to become tangled, greasy and malodorous. The scalp can become encrusted with sebum and dried sweat, which causes a feeling of discomfort. In an attempt to relieve the discomfort the individual may scratch the scalp and cause breaks in the skin that provide a portal of entry for microorganisms.

Hair care includes beard and moustache care as well as shaving, brushing, combing and shampooing head hair. Brushing and combing the hair stimulates scalp circulation, removes dead skin cells and distributes the natural oils that give the hair a healthy sheen (Crisp & Taylor 2009). To brush hair, the nurse parts the hair into several sections. Brushing from the scalp towards the hair ends reduces pulling. Shampooing removes grease, dirt, blood or other substances and prevents an offensive odour. The frequency of hair care depends on the length and texture of the hair, the client’s usual practice and general condition. Hair should be brushed or combed at least twice daily and shampooed according to personal preference or as necessary. Plaiting can help to avoid tangles, but plaits should be unplaited and the hair combed to ensure good hygiene. Plaits that are too tight can lead to discomfort and bald patches.

During long periods of hospitalisation, clients may desire the services of a hairdresser to cut or style their hair, but hair should not be cut or restyled unless the client gives permission. Brushes and combs should be washed regularly and never shared between clients.

Nursing observations and assessment of the hair and scalp

As part of client assessment, the nurse should observe for and report any abnormalities such as excessive dryness, hair fragility or dandruff, alopecia (hair loss) or pediculosis capitis (head lice). The scalp should be observed for redness, heavy scaling, flaking or lesions. Some clients will be able to care for their hair independently, while others will require the nurse’s assistance. Clients may have their hair shampooed during a bath or a shower, or it may be done with the client sitting in front of a sink. If the client is confined to bed the hair may be washed with the client in bed or lying on a trolley.

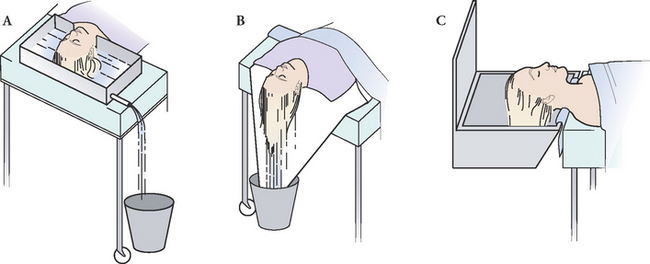

Washing the client’s hair in bed

Certain devices are available to facilitate hair washing in bed, such as a shampoo tray (Fig 21.2A). If specially designed equipment is not available, a waterproof sheet can be placed under the client’s head and arranged so that the water can drain into a bucket at the side of the bed (Fig 21.2B). Clients who can be moved from the bed onto a trolley may be wheeled to a sink and positioned so that the neck is supported on a pillow and the head extended over the sink (Fig 21.2C).

Figure 21.2 Hair washing in bed. A: Using a shampoo tray. B: Hair wash in hospital. C: Client on a trolley for hair wash

The method of giving the client a shampoo is usually determined by the facilities available and the client’s condition. A suggested procedure for shampooing the hair of a client confined to bed is outlined in Procedural Guideline 21.3. The basic equipment for shampooing the hair consists of:

• Shampoo of the client’s choice

• Protection for the bed (e.g. a waterproof sheet)

• Warm water (directed with handheld nozzle or jug)

Procedural Guideline 21.3 Washing a client’s hair in bed

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Arrange the equipment in a convenient location | Facilitates the procedure |

| Position the client lying flat, if not contraindicated | Facilitates the procedure |

| Protect the client and bed linen with waterproof sheet and/or towels | Prevents client and bed from becoming wet |

| Place shampoo tray under the client’s head, or fashion a trough (Fig 21.2B) | Facilitates drainage of water |

| Place a dry face washer across the client’s eyes | Protects eyes from water and shampoo |

| Wet the hair thoroughly, apply shampoo and lather gently | The hair needs to be adequately cleansed and the scalp stimulated |

| Rinse the hair thoroughly | Shampoo must be rinsed off the hair and scalp to prevent dryness |

| Repeat the shampoo and rinsing if necessary | Hair must be adequately cleansed |

| Apply conditioner if the client wishes, comb through and then rinse off | Conditioner helps to keep the hair soft and glossy |

| Remove the tray or trough and wrap a towel around the client’s head. Rub the hair dry or use a hair dryer | It is important to dry the hair quickly to avoid chilling the client |

| Comb or brush the hair | Removes any tangles and helps promote comfort |

| Change any wet bed linen or nightclothes, and assist the client into position | Helps promote warmth and comfort |

| Disinfect used equipment, perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Note the client’s response, document the procedure and report observations | Appropriate care may be planned and implemented |

If a client is too ill or cannot tolerate a shampoo with water, a dry shampoo may be used. Several commercially prepared substances are available that are applied to the hair then brushed out.

Management of pediculosis (lice)

Pediculosis is a condition in which hair is infested with lice. Lice (or pediculi) are parasitic insects that suck blood from the skin and inject a toxin that causes itching, which may result in excoriation from scratching. The lice lay eggs (or nits) which attach themselves along the shaft of the hair with a cement-like substance that makes removal difficult. Pediculosis can occur wherever there is hair and the three varieties of lice infestation are pediculi capitis (head lice) pediculi corporis (body lice) and pediculi pubis (pubic lice). Signs and symptoms that pediculi have infested the hair include pruritus, excoriation of the skin from scratching and visible lice or nits. The body louse tends to adhere to clothing and may not be evident on the body (Parker 2012). Untreated pediculosis can result in secondary skin infection such as dermatitis. The lice also spread from person to person on clothing, bedding, combs and brushes. It is important to note that pediculosis is not necessarily a sign of poor personal hygiene, as the parasites survive equally well on clean hair. The nits and lice can be destroyed by the use of a prescribed lotion or shampoo. With the available preparations, one single application is often effective. Sometimes a second treatment is recommended about 1 week later, in case any remaining nits have hatched into lice. The bed linen, personal clothing, hair brush and comb belonging to the person infested with lice must also be treated to prevent reinfestation. To avoid transmitting the parasites to others, the nurse should wear gloves and perform thorough handwashing after the treatment.

Shaving

Many men shave every day; if so, this should be continued during illness. Shaving promotes client comfort by removing whiskers that may itch and irritate the skin. A facial shave can be performed using an electric or blade razor. Because the skin can be cut or nicked with a blade razor, an electric one is preferable. If a client is unable to shave independently the nurse will need to assist or perform the procedure for the client. Electric razors should be checked for function and cleanliness before use and brushed free of whiskers after use. If the razor head is adjustable the appropriate setting will need to be selected. The nurse proceeds as follows:

• The electric razor is moved in a circular motion, pressed firmly against the skin, and each area of the client’s face shaved until it is smooth

• If a blade razor is used the blade should be checked to see that it is clean, sharp and rust free. Many blade razors are disposable and used once only

• When using a blade razor it is best to use hot water and soap or shaving cream to lather the skin. Shaving is easier if the skin is held taut and the razor drawn over the skin in firm strokes

• When using a blade razor it is best to shave in the direction the hair is growing and to rinse the razor frequently to remove soap and whiskers

• Short gentle strokes are best around the nose and mouth to avoid irritation of these sensitive areas

Some females develop a growth of facial hair, and this is usually removed by depilatory creams, tweezers or wax. Shaving should be avoided because the blunt angle of the cut hairs makes the regrowth look heavier.

EYE, EAR AND NASAL CARE

Assessment and care of the eyes

The eyes are the organs of sight through which visual information about the environment is transmitted to the brain for interpretation. If the eyes are not cleansed adequately, secretions may accumulate. The conjunctiva of the eyes should be observed for inflammation or pallor, and the sclera observed for signs of jaundice. Any discharge, discomfort or pain and the presence of contact lenses, prostheses or spectacles should be noted. Under normal circumstances the eyes are kept clean by face washing and showering. If the eyes become irritated or infected, some clients may require extra care, which consists of cleansing, usually with sterile, soft gauze swabs, to remove secretions from the eyelids and to reduce discomfort. As eye bathing is sometimes required as part of the client’s hygiene needs, guidelines for the procedure are outlined in Procedural Guideline 21.4.

Procedural Guideline 21.4 Performing an eye toilet

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assemble the equipment and place in a convenient location | Items should be readily accessible during the procedure |

| Ensure adequate lighting | Facilitates observation of the client’s eyes |

| Ensure adequate privacy | Reduces embarrassment |

| Position the client with the head slightly to one side | Facilitates the procedure and prevents fluid running down the face |

| Perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Place a towel under, and kidney dish beside, the client’s cheek. Observe for abnormalities | Protects the client and bedding. Additional treatment may be indicated |

| Using sterile technique, open sterile pack and add sterile solution and extra gauze swabs if required | Reduces the risk of cross-contamination |

| Perform handwash procedure and don gloves | Gloves are applied to prevent cross-infection |

| Beginning with the least affected eye, ask the client to close the eye | Prevents contamination from infected eye being transferred to unaffected eye |

| Moisten gauze swabs and cleanse eyelids, from inner canthus to outer canthus (see Fig 21.3) | Prevents injury to the eyeball and prevents fluid and debris from entering the nasolacrimal duct. For safety reasons, forceps are not used |

| Use a clean gauze swab for each wipe and continue until the eye is clean | Prevents cross-contamination |

| Repeat the procedure for the other eye | |

| After cleansing, instil any prescribed drops or ointment | Drops or ointment may be prescribed to treat irritation or infection |

| Wipe any moisture from the client’s face, remove the towel and reposition the client if necessary | Helps promote comfort |

| Remove equipment, dispose of soiled swabs, perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Report and record the procedure | Appropriate care may be planned and implemented |

When bathing the eyes the nurse uses an aseptic technique to reduce the risk of introducing microorganisms. (See Ch 20 for information concerning aseptic technique and the prevention and control of infection.) The eyes are always cleansed from the inner to the outer canthus. The procedure must be carefully performed to prevent any injury to the eyes (Fig 21.3).

Clients who may require special eye care include those whose corneal reflex is impaired, due to altered consciousness or facial paralysis and those whose eyes are irritated or infected. Clients with conjunctivitis, a common condition caused by infection, allergies or irritating substances such as dust or smoke, may also require special eye care. Swabbing or bathing the eyes is sometimes referred to as an ‘eye toilet’ and the basic equipment consists of:

Procedural Guideline 21.4 provide the guidelines for performing an eye toilet but it should be noted that, provided that the principles of asepsis are maintained, it may not always be necessary to use a sterile dressing pack each time an eye toilet is performed. It is best to consult the policy and procedure/safe operating procedure manuals of individual institutions for appropriate guidelines.

Assessment and care of the ears

Lack of aural hygiene can lead to an accumulation of dirt and wax, which may result in discomfort and temporary hearing loss. The ears are cleaned as part of normal hygiene practices, for example, during a shower. They should be assessed for any discharge or complaints of tinnitus, discomfort or pain, and the use of a hearing aid should be noted. (See Ch 32 for relevant information about hearing aids.)

Clients who are dependent on others for their hygiene needs should have their ears cleansed with the face washer during the shower or bath. If there is an accumulation of debris or wax in the orifice, this should be documented and reported. The nurse should not insert any object, including cotton-tipped applicators, into a client’s ear canal as part of routine hygiene. Applicators may compact the cerumen, making the ear more difficult to clean (deWit 2009). Excessive cerumen or dry wax necessitates ear irrigation. This is undertaken only after examination and authorisation by a medical officer and should only be performed by someone who is experienced in this procedure (Linton & Lach 2007).

Assessment and care of the nose

Secretions from the mucous membrane that lines the nose may accumulate, causing discomfort and providing a medium for the growth of microorganisms. The nose should be assessed for the presence of any discharge other than the normal mucus secretion, for bleeding, swelling of the mucosa or any obstruction.

Blowing the nose is the most effective way of removing secretions from the nostrils. If clients are unable to perform this function, as a result of being unconscious or due to presence of an intranasal tube, the nurse may be required to clean the nostrils. This is commonly achieved using small cotton-wool-tipped applicators moistened with a solution such as water or normal saline. An applicator is inserted gently into the nostril, rotated and withdrawn, and the technique is repeated until the nostrils are clean. Sometimes a water soluble cream is applied around the nostrils to prevent soreness. If a client has an endotracheal, nasogastric or feeding tube inserted through the nose, any tapes anchoring the tube should be changed at least daily (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

MOUTH CARE

Poor oral hygiene leads to dental decay and unhealthy mucous membranes, providing a potential source of infection as well as being a source of discomfort for the individual. If food particles are not removed from the mouth and teeth, an unpleasant taste and halitosis (bad breath) can result. The mouth should be inspected for obvious dental decay, pallor, inflammation or the presence of ulcers on the mucosa. The lips should be observed for hydration, pallor or cyanosis and the presence of cracks or vesicles. Dentures, partial plates, bridges and crowns should be noted.

Oral hygiene

Oral hygiene involves measures to keep the mouth and teeth clean and in healthy condition. Care of the mouth includes brushing the teeth, mouth rinses and regular visits to the dentist. The measures necessary to maintain the mouth and teeth in a healthy condition include:

• An adequate fluid intake to stimulate the flow of saliva. Saliva helps maintain a healthy mouth by washing away shed epithelial cells, food debris and microorganisms. Saliva also keeps the mouth lining moist and acts as a mild antiseptic that inhibits the growth of microorganisms, and maintains the pH balance inhibiting the formation of caries (Berman et al 2012).

• A well-balanced diet that provides the tissues with the nutrients necessary for growth and repair. Foods that require chewing stimulate saliva flow as well as blood circulation to the gums and should be included when possible

• Brushing and flossing the teeth to remove plaque and food debris massages the gums, while tongue brushing and cleansing prevent mouth odour and infection

• Rinsing the mouth with alcohol-free mouth washes to remove unpleasant tastes or odours

• Regular visits to the dentist to allow inspection of the teeth for decay, cleaning and treatment of any cavities and other abnormalities.

If oral hygiene is neglected, complications may occur, including:

• Reduced nutrition due to inability to chew and diet restrictions

• Coated tongue and subsequent dulling of taste, which may lead to loss of appetite

• Inflammation of the oral mucosa (stomatitis), inflammation of the tongue (glossitis), inflammation of the gums (gingivitis) and periodontitis (inflammation of ligaments, gums and bones supporting the teeth)

• An accumulation of food particles, dead epithelial cells and microorganisms on the teeth, tongue and lips

• The spread of oral infections to other parts of the body such as the parotid glands, eustachian (auditory) tubes and respiratory tract

At-risk clients

Clients with reduced flow of saliva or those who experience difficulty with normal chewing or whose swallowing actions are impaired are particularly prone to developing an unhealthy condition of the mouth. Examples include clients who:

• Experience dyspnoea, which results in mouth-breathing and consequently a dry mouth

• Are not taking food or fluids orally or whose fluid intake is restricted

• Are receiving certain medications that cause dryness of the mouth

• Have impaired movement of the mouth, such as facial paralysis or surgical immobilisation of the jaw

• Have a nasogastric tube or airway in position, which may irritate or damage the mucosa or lead to an accumulation of debris in the mouth

• Wear partial or full dentures, which allow food particles to accumulate in the mouth

• Are unable to care for their oral hygiene adequately because of their physical or emotional state (Crisp & Taylor 2009; Berman et al 2012).

Clients who have had chemotherapy or radiotherapy are at risk of developing oral thrush and mucositis. It is, therefore, recommended to clean the mouth using saline or water after every meal (Engelking et al 2008).

Assisting the client with oral hygiene

Many clients are able to attend to their oral hygiene but others may require encouragement and some assistance. The nurse should offer clients the opportunity to brush their teeth after meals and in the evening. The nurse should ensure that each client has a toothbrush and toothpaste and should assist them to the bathroom if necessary.

Some clients with cognitive or memory impairment may need repeated prompting to enable them to complete the task of cleaning their teeth. Clients may not clean effectively or may refuse to clean their teeth at all; clients with Alzheimer’s or dementia may not understand what it is they are being asked to do. They may get frustrated, irritated, agitated and even aggressive as a result. Sometimes the problem may be resolved by temporarily distracting the client with another activity and returning later to cleaning the teeth. It may be helpful to follow the routine for cleaning the teeth conducted previously, for example the same time of the day, after breakfast or after getting dressed. It may even help to have a familiar mirror, towel or other object from home. It should be remembered that the client is not being deliberately difficult; a calm, quiet approach and gentle encouragement is often the key to managing challenging responses. Nurses need to find the key to gaining trust from each person.

For clients confined to bed, the nurse should provide teeth-cleaning equipment consisting of a toothbrush, toothpaste, a mug of water, a container for used water and a towel. Clients who are accustomed to using dental floss as part of their normal hygiene should be encouraged to continue the practice. Flossing involves inserting waxed or unwaxed dental floss between the teeth. The motion used to pull floss between teeth removes plaque and tartar from tooth enamel. To prevent bleeding, patients who are receiving chemotherapy or radiation or are on anticoagulant therapy should use unwaxed floss and avoid flossing near the line of the gum. To aid in cavity prevention, apply toothpaste before flossing, thus allowing fluoride to come in direct contact with tooth surfaces. Flossing once a day is sufficient. Floss holders are available for patients who have difficulty managing the floss (Crisp & Taylor 2009).

Clients who are unable to brush their teeth will require the nurse’s assistance with this procedure. Clients are taken to the bathroom, or teeth-cleaning equipment is brought to the bedside. The client should be assisted into a comfortable sitting position and the clothing protected by a towel. The nurse should apply toothpaste to a dampened toothbrush and gently but thoroughly brush the client’s teeth using an up-and-down movement. Water is provided for the client to rinse the mouth, and a container is positioned to receive the used rinsing water. The mouth is then rinsed, but leaving some paste helps protect the teeth. Finally the lips are wiped dry, the toothbrush and toothpaste put away and the mug and container removed for cleaning.

Some clients wear partial or full dentures, which, like natural teeth, require effective care to remove deposits and to prevent mouth odour. Care of dentures involves removing, brushing and rinsing them after meals. If it is the client’s usual practice, dentures may be soaked in a commercial denture cleaner before brushing. All dentures should be removed at night, so the nurse should ensure that they are put in a container labelled with the client’s name and placed in a safe position. Many clients are very reluctant to be seen without their dentures, so it is important to pull curtains and close doors to provide privacy when necessary. If clients are not able to care for their dentures independently it is the nurse’s responsibility to attend to this.

To remove a partial denture the nurse, wearing disposable gloves, exerts equal pressure on the clips each side of the plate ensuring that pressure is not placed on the borders, because they may easily bend or break. A full upper denture may be removed by breaking the seal of the denture from the palate. This can be achieved by taking hold of the denture at the front or side with the thumb and index finger. A lower denture is removed by holding it in the centre, and turning it slightly before lifting it out of the mouth. A gauze square may be used to provide a firm grip on the dentures. Dentures should be gently placed in a denture container and taken to the bathroom for cleaning and rinsing. When handling dentures care must be taken to avoid damage.

Before the dentures are replaced, the client’s mouth is rinsed and the gums brushed to remove any debris. When clients are unable to insert their own dentures the nurse should assist. Moistening the dentures facilitates easier insertion and aids correct positioning into the mouth to keep them firmly in place. Clients should be encouraged to wear their dentures to facilitate eating and speaking and to prevent changes in the gum line that may affect denture fit.

If normal oral hygiene practices are not possible, the mouth and teeth must be cleaned by other means. Special mouth care is often required if the client:

• Is not taking oral food or fluids

• Experiences any impairment to mouth movement (e.g. facial paralysis)

• Has developed sores inside the mouth

• Has a very dry mouth (e.g. as a result of mouth breathing, dehydration, or the effect of certain medications).

In these instances, the client’s mouth is cleansed either by the use of alcohol free mouth rinses or by carefully swabbing all areas. The latter procedure is often referred to as a ‘mouth toilet’. A variety of substances may be used to clean and refresh the mouth. The nurse should refer to the healthcare facility’s policy and procedure/safe operating procedure manual for information on the equipment, substances and method to be used.

A suggested procedure for performing special mouth care (swabbing) is outlined in Procedural Guideline 21.5. The basic equipment consists of:

• Cotton-wool-tipped or foam-tipped applicators

• A receptacle for soiled items

• Cleaning solution (water or diluted sodium bicarbonate)

• Lip cream. (Crisp & Taylor 2009)

Procedural Guideline 21.5 Performing special mouth care (swabbing)

| Review and carry out the standard steps for all nursing procedures/interventions |

| Action | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Assemble the equipment and place it in a convenient location | Nurse must remain with the client throughout the procedure |

| Ensure adequate lighting | Visualisation of the mouth is essential |

| Ensure adequate privacy | Reduces embarrassment |

| Position the client so the head is turned to one side | Reduces the risk of aspiration of fluid |

| If the client is unconscious, suction equipment should be available | To remove excess fluid from the mouth, and prevent aspiration |

| Place a towel under the client’s cheek | Protects client and bedding |

| Perform hand hygiene, don gloves | Prevents cross-infection |

| Remove any partial or total dentures | Allows access to all areas of the mouth |

| Use the tongue depressor to help keep the client’s mouth open, and inspect the mouth | The nurse must be able to see inside the mouth to detect any abnormalities |

| Gently and thoroughly swab all surfaces of the teeth, tongue and mouth | All debris and secretions must be removed |

| Ensure any prescribed substances are applied to ulcers or infected areas | Assists healing |

| Clean dentures thoroughly before replacing them in the mouth | All aspects of oral hygiene must be attended to |

| Apply a lubricant to the lips | Prevents soreness and cracking |

| Wipe any excess solution from the client’s face, remove the towel and reposition the client if necessary | Promotes comfort |

| Remove equipment, dispose of soiled items, perform hand hygiene | Prevents cross-infection |

| Report and document the procedure | Appropriate care may be planned and implemented |

NAIL CARE

Care of the nails involves keeping them clean, shaped and trimmed. Regular care of the nails is important because dirty fingernails can carry microorganisms which may be transferred to food or passed to other people. People who have dirty nails can also infect themselves by scratching. Many clients will be able to care for their nails independently, while others will require assistance. For example, clients who have limbs encased in plaster, are unconscious, confused or vision impaired may need the nurse to assist with nail care.

Routine nail care

Nails should be kept clean and trimmed according to the policy of the healthcare agency and the client’s personal preference. As part of the policy of many healthcare facilities, a podiatrist is required to perform nail care for clients. Nails can be kept clean by removing any visible dirt with a blunt instrument such as an orangewood stick. A metal nail file is not used because it can make the nails rough and trap dirt. Some clients will have their own hand-care products and they should be encouraged to use them after a shower or bath. Nails that are particularly dirty or thickened are easier to attend to if the client’s hands or feet are soaked in warm soapy water for 5–10 minutes before the care begins. Whenever nails are being trimmed, extreme care must be taken to prevent any damage to the nail beds and surrounding tissue

At-risk clients

Clients who have diabetes or any circulatory disorder that affects the lower limbs are at high risk of infection, which can start easily in a damaged nail bed. It is therefore often the policy of the institution that such clients have foot and nail care undertaken only by a podiatrist. The podiatrist is also often required to care for the feet of older people whose nails have become thickened and distorted with age or for those with conditions such as corns, calluses or in-growing toenails. Nail clippers are used in preference to scissors for trimming nails. Toenails should be cut straight across. Nails not trimmed in this way tend to grow inwards, creating a risk for pain and infection in the surrounding soft tissue.

Nursing observations and assessment

While undertaking nail care the nurse observes for:

• Discolouration, such as pallor or cyanosis

• The presence of inflammation around the nail edges

• Signs of brittleness or cracks

• Deviations from normal shape, such as a spoon-shaped or concave appearance.

Pallor or cyanosis of the nails may indicate heart disease, while brittleness and/or a spoon-like shape may indicate the presence of an iron-deficiency anaemia. Any change or abnormality should be reported and documented. During nail care, the nurse can take the opportunity to educate clients, or those who care for them at home, on how best to provide nail care. Education can also include how to inspect the hands and feet for lesions, dryness or signs of inflammation or infection, and the importance of reporting any change or abnormality promptly to the registered nurse or medical officer.

HYGIENE SUMMARY

Personal hygiene needs must be met to keep the body clean, to maintain healthy functioning and to promote a positive body image. Neglect of personal hygiene needs causes discomfort and may lead to infection and other serious complications. Continuous assessment of the client’s total body is important for planning and implementing appropriate, high-quality nursing care. It is the nurse’s responsibility to ensure that all clients have access to the facilities necessary for meeting their hygiene needs. Dependent clients require assistance from the nurse in meeting these needs and the nurse should ensure that the client’s dignity, comfort and safety are promoted throughout all hygiene care procedures. The nurse also has an important role to play in educating clients and those who care for them at home about all aspects of hygiene that promote optimal health.

PROMOTING COMFORT

Human comfort depends on meeting a wide range and complex interaction of needs. Nutritional, fluid, elimination, oxygen and temperature regulation needs must be met for the human body to function efficiently and comfortably. The nurse’s role incorporates monitoring and meeting these needs. In addition, the nurse promotes the comfort of clients by promoting ease of movement, rest and sleep and freedom from pain. (See the relevant chapters in Unit 8 for specific information relating to these areas.)

Physical and emotional comfort are interdependent and if either aspect is disrupted, the other is commonly affected. For example, if clients are experiencing some form of physical discomfort such as pain, they may develop emotional tension and become withdrawn, anxious or depressed. Conversely, an anxious person may develop physical symptoms such as headaches, loss of appetite or gastrointestinal disturbances. Therefore, for clients to be comfortable, they must be free from physical discomfort and emotional tension. An important nursing responsibility is assessing factors that are interfering with clients’ comfort, then planning and implementing measures that promote their physical and emotional ease. Discomfort can result from stimuli of physical or psychosocial origin. Freedom from anxiety is important in helping the client to develop a sense of wellbeing and emotional security. To promote the physical comfort of clients the nurse should assist in meeting all care needs. This includes ensuring that clients are wearing comfortable clothing which is suitable for the environment; clients should be nursed in the most comfortable position possible.

Clothing and comfort

A person’s comfort is enhanced if they are able to wear clothes of their own choice. Many people feel uncomfortable and undignified if they are required to wear clothing such as a hospital gown provided by the healthcare facility. For this reason, clients returning from surgery or other procedures are changed into their personal attire as soon as their condition allows. Some residents living in aged-care facilities or special accommodation do not have adequate clothing of their own. In this case the nurse should ensure that the clothes supplied by the agency are appropriately selected to meet the residents’ individual needs. For example, for an older person living in an aged-care facility the choice of clothes should be appropriate in terms of age, gender, temperature and other environmental conditions. They should be clean, fit well and, in the case of clients who are very frail or confused, be easy for them to manage, for example, velcro fastenings for ease of dressing and toileting.

Comfort and the environment

A suitable physical environment is one in which there is adequate lighting, fresh air, ventilation, warmth and cleanliness. Depending on the patient’s age and physical condition, the room temperature should be maintained between 20°C and 23°C. The acutely ill, infants and older adults may need a warmer room. However, some ill clients benefit from cooler room temperatures to lower the body’s metabolic demands (Crisp & Taylor 2009). Ideally the environment should be free from excessive noise and unpleasant sights and smells. In addition, there should be sufficient space for the client’s personal belongings, and facilities available for visitors. In the case of residents in long-term accommodation the environment should be as home-like as possible, have attractive views to the outside world and an outdoor area that is safe and accessible. Ideally, residents will have a single room. If not, the facility should provide a room where residents can spend private time with visitors if they wish. The environment should also provide a relaxed happy atmosphere and opportunities to enjoy activities that enhance quality of life, such as outings, concerts and games. For those who are able, the environment should provide the chance for residents to participate in simple everyday activities such as watching television, gardening, crafts or cooking. Comfort can be enhanced by promoting a psychological climate in which the client is encouraged to communicate any fears or anxieties. A physical environment that reduces the client’s privacy and independence is unsuitable and can be a source of stress and discomfort.

Equipment to promote comfort

Provision of a comfortable bed

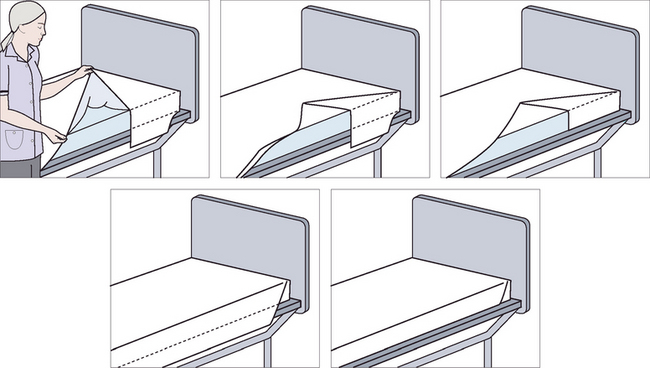

A comfortable position is, to a significant extent, dependent on the client’s bed. The prime objective of bed making is the promotion of comfort, as a bed that is made incorrectly may disrupt rest and sleep and may be a contributing factor to the development of complications such as decubitus ulcers (Berman et al 2012). Beds may be made up in a variety of ways to meet the client’s needs and each healthcare facility commonly adopts its own method of bed making. Although the techniques may vary slightly, the principles of bed making remain the same.

Various types of bed are available, most of which can be adjusted manually, mechanically or electronically. Most beds can be raised or lowered horizontally and most can also be adjusted to alter the position of the head, foot or centre. Beds are fitted with wheels, which enables them to be moved easily when necessary, and a brake device that prevents inadvertent movement. The nurse should check that the brakes are applied at all times when the bed is stationary. There are several special types of beds, frames and mattresses that are used for particular circumstances.

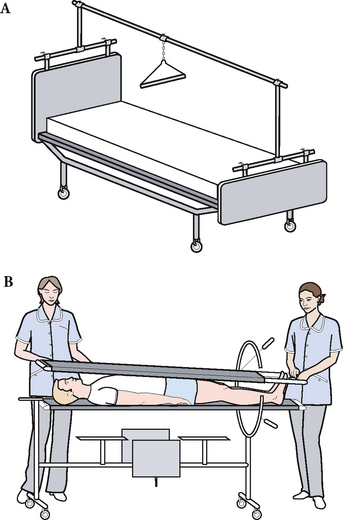

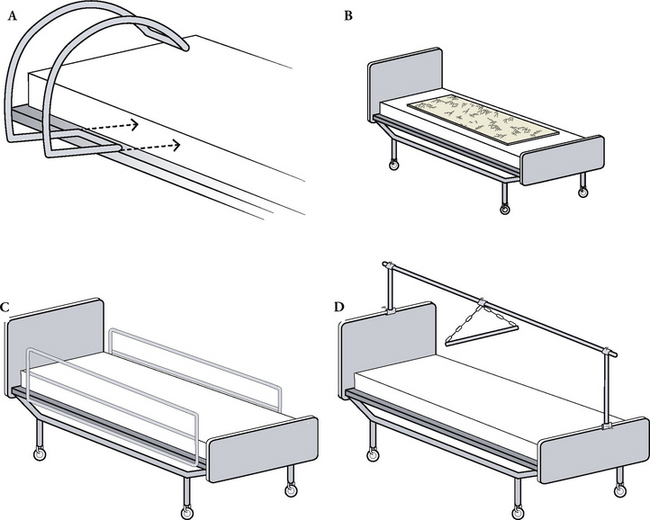

Frames are available that may be either fitted to the bed or used in place of a more conventional bed. The Balkan frame, for example, is made from wood or metal, extends lengthwise above the bed, and may be used in conjunction with traction apparatus. The Bradford frame consists of a metal frame across which canvas slings are stretched, and may be used to nurse a person who has a fracture or disease of the hip or spine. The Stryker frame consists of two canvas-covered frames attached to a metal frame and may be used to facilitate changing the position of a person with a spinal cord injury or paralysis. Figure 21.4 illustrates the Balkan and Stryker bed frames.

Figure 21.4 Bed frames and special beds. A: Balkan frame. B: Stryker frame. The client is turned to the prone or supine position. Body alignment is not changed during repositioning

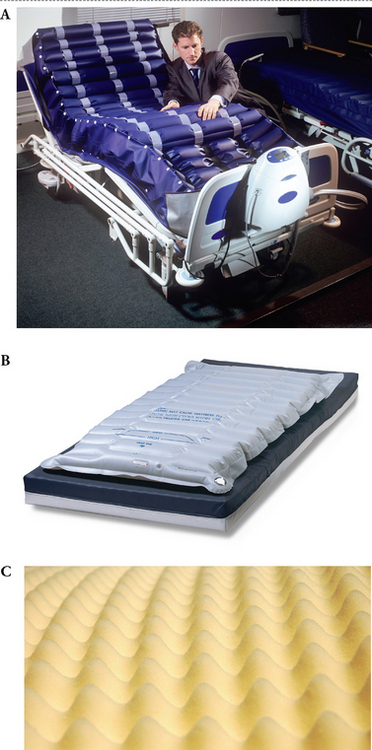

Foam mattresses are commonly covered with a waterproof fabric, which facilitates cleaning and therefore helps to prevent cross-infection. Clients with specific needs, such as those who are more vulnerable to the development of decubitus ulcers, may be nursed on special mattresses. The most commonly used pressure relieving devices are alternating air mattresses. These devices work by over- and underinflating in sequence as the client moves around in the bed (Fig 21.5A). Other, less commonly used devices include the gel mattress (Fig 21.5B) and the foam overlay (egg-crate style) mattress (Fig 21.5C). The type of mattress selected must meet the client’s needs, provide comfort and support and should help prevent development of complications.

Figure 21.5 Special mattresses. A: Air mattress. B: Gel mattress. C: An egg-crate mattress

(A: © Brian Bell/Science Photo Library/Getty Images; B: Blue Chip Medical Products, Inc.; C: © kanusommer/Shutterstock)

Pillows are available in a variety of materials, most of which are enclosed in a protective waterproof covering over which a pillow slip is placed. The number of pillows used depends on the needs of the client, and should be sufficient to provide maximum comfort and support.

Sheets are commonly available in two styles: the long sheet is similar to a conventional single-bed sheet; the draw sheet is a narrow sheet that may be placed across the bottom sheet. Because of their design, draw sheets are easy to replace under a client without disturbing the other bedclothes. A waterproof sheet may be placed under the draw sheet to protect the bottom sheet against moisture, for example, if a client is incontinent or is required to use toilet utensils in bed. In some care settings, special reusable incontinence bed protectors with tuck-in flaps are available and may be used instead of a draw sheet. These maintain a client’s comfort because they are double or multi-layered and very absorbent. They have an integral waterproof barrier, which means that the side on which the client lies remains dry. They are commonly referred to as ‘Kylie sheets’. Disposable liners are more commonly used these days. Care needs to be taken if an air mattress is in place that sheets are not tucked in, as this interferes with the inflation/deflation.