Chapter 27 Health assessment

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Explain the purposes of health assessment for nursing practice.

• Apply the functional health patterns framework to systematically collect data required for focused health assessments.

• Identify specific nursing history information to collect across the various areas of the functional health framework.

• Describe interview techniques used to enhance communication during history taking.

• Identify the physical, psychological and environmental considerations and patient preparations required before and during an examination.

• Identify ways of respecting patient preferences when conducting health assessments.

• Describe the physical assessment techniques relevant to each area of health assessment.

• Differentiate normal from abnormal assessment findings.

• Use patient data to formulate problem statements.

Health assessment and physical examination

Learning about health assessment and physical examination is one of the most important and challenging aspects of becoming a registered nurse (RN). While often invisible to others, assessment comprises a major part of what expert RNs do in their daily practice. As a nurse, you will constantly observe and analyse situations to make clinical judgments. Learning to assess patients systematically and comprehensively is important because your assessment drives all components of the nursing process (Douglas and Stolic, 2011). Incomplete or inaccurate assessment leads to errors in identifying problems or making poor judgments, which put your patients at risk of ineffective, inefficient or unsafe nursing care (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2010). Assessment data provide the foundation on which nurses base their decisions, interventions and evaluations.

Nurses are usually the first healthcare professional to identify and act on changes in the patient’s condition. Health assessment skills allow nurses to identify life-threatening complications and recognise subtle, as well as obvious, changes that reflect deterioration of the patient’s health status. Through early detection and intervention for patient problems, nurses save lives and improve patient outcomes every day.

This chapter presents an overview of the fundamental health assessment knowledge and skills you will need as a beginning RN. Advanced or specialised assessment skills and techniques are beyond the scope of this chapter. The interested reader should consult a comprehensive nursing health assessment text such as Jarvis’s Physical examination and health assessment (Forbes and Watt, 2012).

Frameworks for health assessment

Health assessment can be organised in a number of different ways using frameworks such as body systems, head-to-toe, activities of daily living and functional health assessment. A framework provides focus and structure for your assessment. While it is important to become familiar with each of these approaches, the type of assessment required will depend on the patient and the context of nursing care.

This chapter is broadly organised around Gordon’s (1994) 11 functional health patterns framework (see Table 27-1). This holistic framework assists in developing a nursing perspective to health assessment which helps you to focus on relevant aspects of the person and how their health and function are affected by changes in health status. The framework is used to identify possible areas where there is a change in function, as well as associated risks. Once you have collected patient information (subjective and objective data), you are then able to identify actual and potential health problems. Once the problems are known, evidence-based interventions can be implemented.

TABLE 27-1 FUNCTIONAL HEALTH PATTERNS HEALTH ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK

| FUNCTIONAL HEALTH PATTERN |

FOCUS OF HEALTH ASSESSMENT |

| Health perception–health management pattern |

Describes the individual’s perceived pattern of health and well-being and how health is managed

Reason for seeking healthcare

Description of present illness (onset, course, treatment)

Description of health (usual)

Relevance of health to activities

Preventative measures, general healthcare behaviour

Previous hospitalisations, expectations for this episode

|

| Nutritional–metabolic pattern |

Describes patterns of food and fluid consumption relative to metabolic needs and pattern indicators of local nutrient supply

Usual food and fluid intake (24-hour dietary recall)

Daily eating times

Recent weight change and reason

Food restrictions or preferences, supplements

Swallowing, chewing, eating problems, food allergies

Skin lesions and general ability to heal

Condition of the skin, hair, nails, mucous membranes and teeth

|

| Elimination pattern |

Describes patterns of excretory function (bowel, bladder and skin)

Bowel, bladder and skin excretion

Regularity of urination and bowel evacuation

Colour, quality and quantity of urine and faeces

Aids used to facilitate function, such as routines, devices (laxatives, suppositories, enemas) and methods to control excretion

Changes or disturbances in bowel or bladder elimination

|

| Activity–exercise pattern |

Describes patterns of exercise, activity, leisure and recreation. The activity–exercise pattern describes three functions that are important to everyone’s daily life:

Mobility—movement, posture, balance and gait

Independent self-care—ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs)

Exercise and leisure—exercise tolerance, activities requiring energy expenditure

|

| Cognitive–perceptual pattern |

Describes sensory-perceptual and cognitive patterns. The ability to collect information from the environment and use it in reasoning and other thought processes

Adequacy of hearing, vision, smell, touch, taste

Impact on ADLs and compensation or devices used such as glasses or hearing aids

Pain and how it is managed

Cognitive functional abilities such as orientation, memory, reasoning, judgment and decision making

|

| Sleep–rest pattern |

Describes patterns of sleep, rest and relaxation in a 24-hour period

Usual sleep routine, sleep pattern

Perception of quality and quantity of sleep

Rest and relaxation or quiet periods during the day

Sleep disturbances

Use of aids to sleep, such as medications or night-time routines

|

| Coping–stress tolerance pattern |

Describes the client’s general coping pattern and the effectiveness of the pattern in terms of stress tolerance

Stressors and stress tolerance

General coping strategies

Support systems

Perceived ability to control or manage situations

|

| Role–relationship pattern |

Describes the work, family and social roles and relationships of individuals that may be influenced by health-related factors or may offer support during illness

Life roles and responsibilities

Satisfaction or dissatisfaction in family, work and social relationships

Impact of illness on roles and relationships

|

| Self-perception–self-concept pattern |

Describes the client’s self-concept pattern and perceptions of self (e.g. self-identity, esteem and body image, self-efficacy, mood state)

Self-description

Effects of illness on self-concept

Body image, identity, self-esteem

Posture, eye contact, voice and speech patterns

|

| Sexuality–reproductive pattern |

Describes the client’s patterns of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with sexuality pattern; describes reproductive pattern

Perceived satisfaction or dissatisfaction with sexuality–reproductive pattern

Impact of illness or treatments on sexual activity

Adequacy of sexual knowledge

Reproductive development and state (e.g. menstruation and menopause)

|

| Values–beliefs pattern |

Describes patterns of values, beliefs (including spiritual) and goals that guide the client’s choices or decisions

Values, goals or beliefs that are basis for decision making

Spiritual or religious affiliation

Spiritual practices and religious needs

|

Adapted from Gordon M 2007 Manual of nursing diagnosis, ed 11. Ontario, Jones & Bartlett.

Examples of how to apply a body systems assessment framework are also provided throughout the chapter with the inclusion of focused assessment skills in each relevant functional health pattern. These can also be contrasted with a head-to-toe assessment framework (e.g. see Boxes 27-1 and 27-2 for examples of focused cardiovascular and respiratory assessments). The important point here is that there are multiple frameworks available, and you must decide which is the most relevant to the clinical situation. The key to a successful nursing assessment is to learn to be organised and systematic during data collection.

BOX 27-1 EXAMPLE OF FOCUSED CARDIOVASCULAR ASSESSMENT USING A HEAD-TO-TOE FRAMEWORK

GENERAL SURVEY

Observe colour and mental status

UPPER LIMBS

Inspect hands and nails for temperature, capillary refill time

Palpate radial pulse rate, rhythm, strength

Measure blood pressure

NECK AND CHEST

Inspect neck veins

Inspect chest

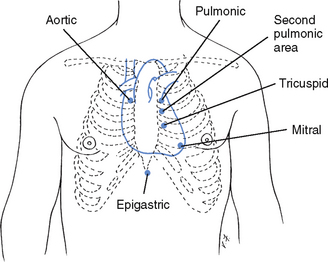

Auscultate heart sounds (for normal S1 and S2)

Auscultate posterior lung sounds

Palpate for sacral oedema

ABDOMEN

Palpate abdomen

Measure urine output

LOWER LIMBS

Inspect and palpate for colour, warmth, movement, sensation

Palpate pulses

Palpate calves for tenderness

Inspect and palpate for oedema

BOX 27-2 EXAMPLE OF FOCUSED RESPIRATORY ASSESSMENT USING A HEAD-TO-TOE FRAMEWORK

General survey

Observe colour, mental status, posture and work of breathing

UPPER LIMBS

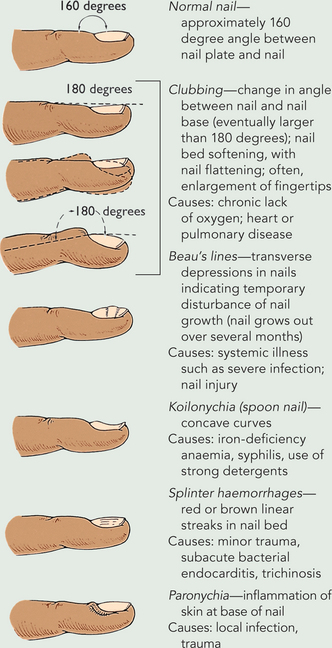

Inspect nails for clubbing and capillary refill time

Measure pulse and blood pressure

Measure peripheral oxygen saturation

HEAD, EARS, EYES, NOSE AND THROAT (HEENT)

Measure temperature

Observe cough/sputum

Inspect for cyanosis

Inspect trachea is midline

CHEST

Measure respiratory rate

Inspect and palpate chest for size, shape, symmetry

Auscultate anterior/posterior lung sounds

Gathering a health history: subjective data collection

The main objective of asking the patient questions is to find out what is central to their concerns so that you can identify the areas requiring physical examination. You would then explore these concerns in depth to determine onset, duration, location, severity, pattern and factors associated with the symptom(s). From there you would determine any risk factors for the patient (e.g. risk of falling or skin breakdown), as well as changes in level of function. These questions may be referred to as a health or nursing history (see Chapter 6).

Physical examination: objective data collection

This component of assessment requires systematic planning and focused data collection so that you can then identify solutions to actual and potential problems. Adherence to basic principles can help in laying the groundwork for a well-organised physical examination. Objective data collection should be designed to accommodate the patient’s immediate and ongoing needs. If a patient is acutely ill, it is essential that you recognise the presenting symptoms and focus the assessment accordingly. A complete examination may be conducted if necessary when immediate and life-threatening needs have been met.

Information gathered during an initial physical assessment provides a baseline of the patient’s functional abilities, symptoms being experienced and areas of risk. The baseline is not necessarily the normal range of physical findings, but rather the pattern of findings identified during initial assessment for that patient. This baseline serves as a comparison for future assessment findings and helps determine the patient’s response to therapeutic interventions.

Nurses use physical assessment skills to:

• gather baseline data about the patient’s health

• supplement, confirm or refute data obtained in the nursing history

• confirm and identify patient problems, areas of risk or change in function

• make clinical judgments about a patient’s changing health status and management

• evaluate the physiological outcomes of care.

• CRITICAL THINKING

What is the purpose of health assessment? How does health assessment from a nursing perspective differ from that in other healthcare disciplines?

Developing problem statements and a care plan

The combination of data from the health history and physical examination allows you to identify the patient problems which you are licensed to treat, either independently or collaboratively with the medical practitioner or allied health team members. The history allows you to gather a complete and detailed database about the patient’s areas of concern. A physical assessment is conducted to refute, confirm or supplement the existing database. Using critical thinking skills helps you to interpret the meaning of the information provided by the patient, apply knowledge from previous clinical care and methodically conduct an examination to create a clear picture of the patient’s status.

It is strongly recommended that you gather as much information as possible to ensure that you can correctly interpret the problem the patient is experiencing. For example, if the patient informs you that they have some abdominal discomfort and bloating, you will have some thoughts as to what the problem might be. You will more than likely ask questions about the person’s urinary and bowel elimination. You will then be in a position to focus your physical assessment to confirm the subjective data. Significant findings are grouped into patterns of data that reveal actual or potential patient problems. In relation to the previous example, you may identify that the person is constipated or has a potential to develop constipation.

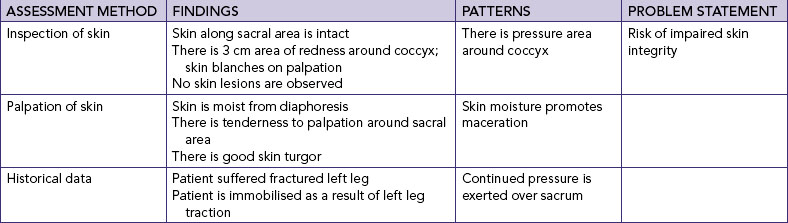

The database developed from the history and physical examination allows you to develop individualised problem statements for the patient (Table 27-2). Health assessment findings also help determine the aetiology of problems so that you can select the most appropriate nursing interventions.

Evaluating nursing care

Health assessment is ongoing in order to evaluate the patient’s response to interventions. This is achieved through monitoring physiological and behavioural outcomes of care. For example, palpation of the patient’s pulse is used as part of assessment and is also used to evaluate patient response to nursing interventions. Health assessment tools and techniques are also used to review existing problem statements, identify new problems and update the care plan in line with changes in the patient’s condition.

• CRITICAL THINKING

How will health assessment assist you to provide high-quality and safe nursing care for a patient?

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

A physical examination is performed by respecting patients’ preferences. How individuals behave as a result of their cultural heritage, health beliefs, use of alternative therapies, nutritional habits, relationships with family and comfort with the nurse’s physical closeness during an examination must be considered. Being sensitive to patient preferences is an important consideration when planning the assessment. Some patients prefer to have another person present, and this wish must be respected. Recognition of diversity will help you to respect a patient’s uniqueness and to provide person-centred care.

Integration of physical assessment with nursing care

A focused assessment is usually integrated into routine care. For example, you can assess the condition of the skin and other body parts during a bed bath or shower (see Chapter 30). You will have many opportunities to assess the patient during the day. For example, by observing the patient transferring into or out of the bed, walking down the corridor, feeding or dressing gives you a wealth of information about level of energy, activity tolerance, muscle strength, range of motion and gait.

Physical assessment techniques

Chapter 6 briefly described the techniques of inspection, palpation, percussion and auscultation. This chapter provides a more detailed description of those skills and their application to the physical examination.

Inspection

Inspection is the process of observation. The purpose of inspection is to detect normal characteristics or significant physical signs. You can observe many aspects of your patient as you are talking to them. For example, while you are performing nursing interventions such as assisting the patient with a shower or checking an intravenous infusion you will be observing the patient. To use inspection effectively, follow the following principles.

• Keep the patient informed. This includes providing a general explanation before starting the physical examination followed by a more specific explanation for each step of the examination.

• The patient should be relaxed and positioned comfortably because muscle tension impairs the effectiveness of the physical examination.

• Use good lighting and additional light (e.g. a penlight) to inspect body cavities such as the mouth.

• Position and expose body parts so that essential surfaces can be viewed while maintaining the patient’s dignity.

• Be aware of normal physical characteristics related to age and gender.

• Always pay attention to the patient, watching all movements and non-verbal cues.

• Inspect each area for size, shape, colour, symmetry, position, abnormalities and function.

• Compare each area inspected with the same area on the opposite side of the body.

• Do not hurry inspection—be thorough and pay attention to detail.

After inspection is completed, findings may indicate the need for further examination. Palpation is often used in conjunction with or after visual inspection.

Palpation

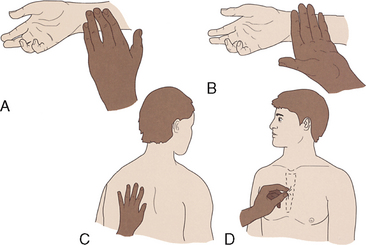

Further assessment is made through the use of touch. Through palpation, the hands can make delicate and sensitive measurements of specific physical signs, including resistance, resilience, roughness, texture and mobility (Table 27-3). Different parts of the hand are used when touching the skin to detect characteristics such as texture and temperature (Figure 27-1). Ask the patient to take slow, deep breaths as this enhances muscle relaxation.

TABLE 27-3 EXAMPLES OF CHARACTERISTICS MEASURED BY PALPATION

| AREA EXAMINED |

CRITERIA MEASURED |

| Skin |

Temperature

Moisture

Texture

Turgor and elasticity

Tender ness

Thickness

|

| Blood vessels (e.g. carotid or femoral artery) |

Symmetry and mobility

Pulse amplitude

Elasticity

Rate

Rhythm

|

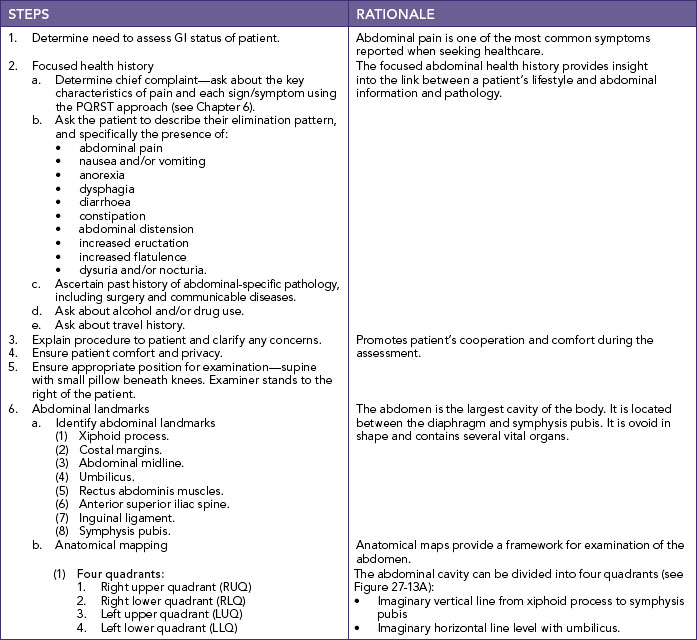

Patients appreciate warm hands, short fingernails and a gentle approach. Identify the body area to be palpated, as well as the reason for using palpation. Tender areas are palpated last. Ask the patient to point out the more sensitive areas. Place your hand on the part to be examined and depress the area about 1 cm. Tactile pressure is applied slowly, gently and deliberately. Lightly palpate structures to determine areas of tenderness. Note any non-verbal signs of discomfort.

Percussion

Percussion involves tapping the body with the fingertips to evaluate the size, borders and consistency of body organs and to discover fluid in body cavities. As such, it is a technique that is used in a limited way by beginning RNs. It requires considerable skill and can help to confirm other assessment findings. Percussion helps verify abnormalities assessed through palpation and auscultation. For example, in the case of abnormal or absent bowel sounds on auscultation of the abdomen, percussion may confirm the presence of fluid, air or solid material in the bowel.

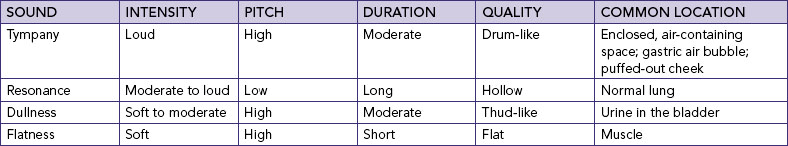

Percussion involves striking one object against another, thus producing vibration and subsequent sound waves. When the examiner strikes the body’s surface with a finger, vibration is transmitted through the body tissues. Sound waves are heard as percussion tones arising from vibrations 4–6 cm deep in body tissue (Seidel and others, 2011). The character of the sound depends on the density of the underlying tissue. Percussion produces characteristic sounds: tympany, resonance, dullness and flatness. Each sound is created by certain types of underlying tissues and is judged by its intensity of pitch, duration and quality (Table 27-4). For example, the percussion of the abdomen can elicit sounds with high intensity and low pitch.

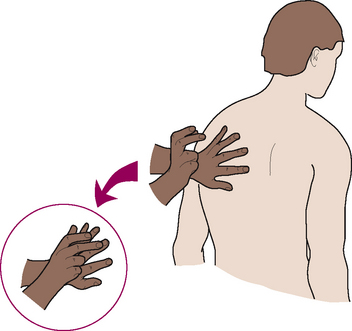

Percussion is performed by placing the middle finger of the non-dominant hand (called the pleximeter) firmly against the body surface, keeping the palm and remaining fingers off the skin. The tip of the middle finger of the dominant hand (called the plexor) strikes the base of the distal joint of the pleximeter (Figure 27-2). The examiner uses a quick, sharp stroke with the plexor finger, keeping the forearm stationary. The wrist remains relaxed to deliver the proper blow. If the blow is not sharp, if the pleximeter is held loosely or if the palm rests on the body surface, the sound is dampened or softened, preventing transmission of sound to underlying structures. The same force must be applied to each area so that an accurate comparison of sounds can be made.

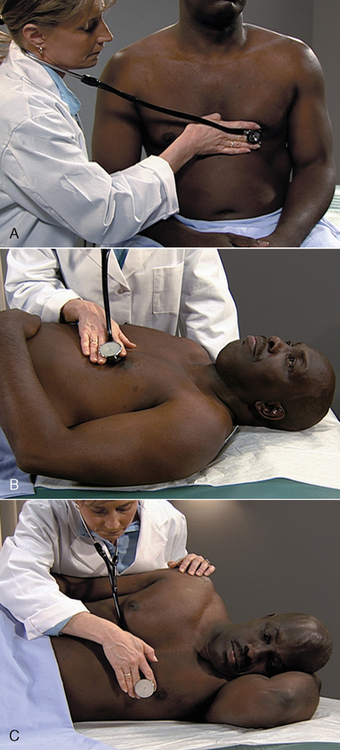

Auscultation

Auscultation is listening to sounds produced by the body and helps you to interpret the findings from the other examination techniques. Auscultation is generally carried out after inspection, palpation and percussion techniques are used, with the exception of abdominal assessment (see section on elimination).

To auscultate correctly, you will need practice, good hearing acuity, a good-quality stethoscope and knowledge of how to use the stethoscope properly. The stethoscope should always be placed directly on skin, because clothing obscures sound. The bell is best for low-pitched sounds and the diaphragm is best for high-pitched sounds, such as bowel and lung sounds.

A number of extraneous sounds created by movement of the tubing or chest-piece interfere with auscultation. You will learn to recognise and disregard them during the actual examination (Box 27-3). Through auscultation, note the following characteristics of sounds:

• Loudness, or the amplitude of a sound wave. Auscultated sounds are described as loud or soft.

• Quality, or sounds of similar frequency and loudness from different sources. Terms such as blowing or gurgling describe the quality of sound.

• Duration, or the length of time that sound vibrations last. The duration of sound is short, medium or long. Layers of soft tissue dampen the duration of sounds from deep internal organs.

BOX 27-3 EXERCISES TO INCREASE FAMILIARITY WITH THE STETHOSCOPE

• Ensure that the earpiece follows the contour of the ear canal. Learn what fit is best for you by comparing amplification of sounds with the earpieces in both directions.

• Place the earpieces in your ears with the tips of the earpieces turned towards the face. Lightly blow into the diaphragm. Again place the earpieces in your ears, this time with the ends turned towards the back of the head. Lightly blow into the diaphragm. After you have learned the right fit for the loudest amplification, wear the stethoscope the same way each time.

• Put on the stethoscope and lightly blow into the diaphragm. If the sound is barely audible, lightly blow into the bell. Sound is carried through only one part of the chestpiece at a time. If the sound is greatly amplified through the diaphragm, the diaphragm is in position for use. If the sound is barely audible through the diaphragm, the bell is in position for use. Rotation of the diaphragm and bell places the chestpiece in the desired position. Leave the diaphragm in position for the next exercise.

• Place the diaphragm over the anterior part of your chest. Ask a friend to speak in a normal conversational tone. Environmental noise seriously detracts from hearing the noise created by body organs. When a stethoscope is used, the client and the examiner should remain quiet.

• Put the stethoscope on and gently tap the tubing. It is often difficult to avoid stretching or moving the stethoscope’s tubing. The examiner should be in a position so that the tubing hangs free. Moving or touching the tubing creates extraneous sounds.

CARE OF THE STETHOSCOPE

Earpieces should be removed regularly and cleaned of cerumen (ear wax). The bell and diaphragm are cleaned of dust, lint and body oils. The tubing should be kept away from nurses’ body oils. Avoid draping the stethoscope around the neck next to the skin. Cleansing the tubing with alcohol can dry and crack the material and is not recommended. Mild soap and water are preferred.

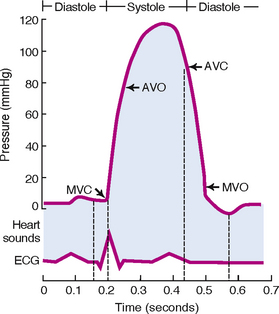

To recognise abnormal sounds and their origins, try closing your eyes and considering the part of the body being auscultated and the causes of the sounds. For example, the first heart sound (S1) is caused by closure of the atrioventricular (AV) heart valves and so you can hear S1 at the same time as you feel the carotid pulse.

Olfaction

Familiarity with the nature and source of body odours will assist you to interpret various odours. For example, a patient with a plaster cast is expected to experience discomfort after an injury. However, evidence of a strong odour may be related to wound infection. The discomfort alone does not reveal the presence of infection. Findings from olfaction and other assessment skills allow the detection of serious abnormalities.

Preparation for examination

Proper preparation of the environment, equipment and patient ensures a smooth and accurate health assessment with few interruptions or errors.

Infection control

Hand hygiene is essential before equipment preparation (Box 27-4) and the examination, to reduce the transmission of microorganisms. The equipment needed for an examination should function correctly, be clean and be readily available. The equipment should be warmed as required. For example, the diaphragm of the stethoscope may be briskly rubbed between the hands before it is applied to the skin.

BOX 27-4 EQUIPMENT USED FOR COMPLETE PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

Cotton applicators

Disposable pad

Drapes

Torch and spotlight

Forms (e.g. physical, laboratory)

Gloves (clean)

Gown for patient

Water-soluble lubricant

Paper towels

Scale with height measurement rod

Sphygmomanometer and cuff

Stethoscope

Tape measure

Thermometer

Tissues

Tongue depressors

Wristwatch with second hand or digital display

Examination techniques increase the risk of contact with body fluids and discharge. Standard precautions should be used throughout the examination (see Chapter 29). Gloves and/or a gown may be necessary during palpation and percussion only if there is a risk of coming into contact with the patient’s body fluids.

Environment

Health assessment requires privacy. Although a well-equipped examination room is preferable, in hospitals the examination usually occurs in the patient’s room. It is necessary wherever the assessment is conducted to use room curtains or dividers around the bed, shut the door and talk to the patient in a low voice if possible. In the home, the examination would normally be conducted in the patient’s bedroom.

Adequate lighting is needed for proper illumination of body parts. The main lighting can be either daylight or artificial light, as long as the light is direct enough to reveal skin characteristics without distortion from shadows. Sometimes it is difficult to examine patients who are in beds or on stretchers. Special examination tables make examinations easier and help patients assume particular positions. In this case, patients who are examined on examination tables require assistance getting on and off the table. Never leave a confused or uncooperative patient unsupervised. When the patient lies supine, provide a small pillow and raise the head of the table about 30 degrees.

Physical preparation of the patient

The patient’s physical comfort is vital to a successful examination. Before starting, ask if the patient needs to use the toilet. An empty bladder and bowel facilitate examination of the abdomen, genitalia and rectum, and provide the opportunity to collect urine or faecal specimens if required.

Preparation involves ensuring the patient is appropriately dressed and draped. A patient in the hospital is likely to be wearing a simple gown. If the examination is limited to certain body systems, it may be unnecessary for the patient to undress completely. The patient should have privacy during undressing and plenty of time to finish—walking into the room as the patient undresses can cause embarrassment. After the patient has undressed and donned the gown, they should sit or lie down with a drape over the lap or lower trunk. Make sure the patient stays warm by eliminating draughts, controlling room temperature and providing warm blankets.

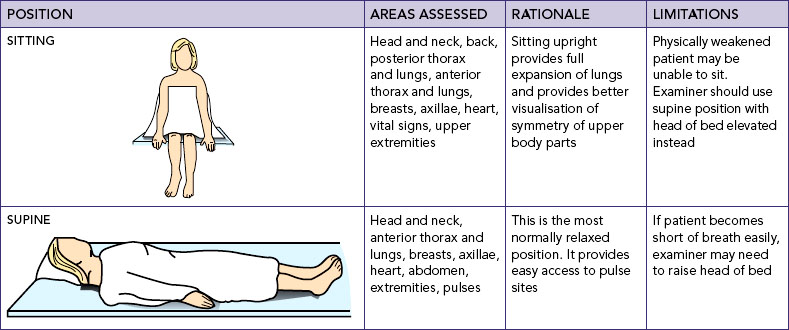

Positioning

You may need to ask the patient to assume positions which increase the accessibility of body parts and facilitate patient comfort (Table 27-5). Patients’ abilities to assume positions will depend on their physical strength, mobility, ease of breathing, age and degree of wellness. The drapes are adjusted to facilitate an examination of a specific area without unnecessarily exposing other body parts. More than one position can be assumed for the same part of an examination (e.g. supine and sitting for assessment of the anterior thorax), so choose the position that provides greater accessibility and accuracy in assessing body parts. However, if the patient is too weak or physically unable to assume a position, you will need to choose an alternative position. Patients should also be positioned so that they avoid looking into the source of light.

Psychological preparation of the patient

Patients can be embarrassed when asked to answer sensitive questions about bodily functions or when body parts are exposed and examined. The possibility of an abnormal finding also creates anxiety, so reduction of this anxiety may be your highest priority before commencing the assessment. This is achieved by conveying an open, receptive and professional approach. A stiff, formal demeanour may inhibit the patient’s ability to communicate, but an overly casual style may fail to instil confidence (Seidel and others, 2011). An initial explanation tells patients what to expect and their role and rights throughout the examination. As the examination progresses, a more detailed explanation of each step is provided.

Simple terms are used when describing the steps of the examination. Complicated terminology may confuse the patient and add to their fears. Encourage the patient to ask questions and to mention any discomfort they feel during the assessment. If the patient is of the opposite gender, it may be necessary to have another person of the same gender in the room, especially during examination of the sexual organs. This third person acts as a witness to the proper conduct of the examination and their presence reassures the patient that the examiner will behave ethically.

During the assessment observe the patient’s emotional responses—does the patient’s facial expression convey fear or concern and body movements reveal anxiety, such as frequently pulling the drape around the body or tensing up as the examiner touches the body? It may be necessary to stop the examination to confirm such findings and take time to reassure the patient and clarify the purpose of the examination, and proceed only when the patient is comfortable. Postponing the examination to a later time may be advantageous because the findings may be more accurate when the patient is more relaxed.

Assessment of age groups

Different interview styles and approaches to physical examinations are used for patients of different age groups.

Children

When assessing children, be sensitive and anticipate the child’s reaction to the examination as a strange and unfamiliar experience. The focus of a comprehensive and routine paediatric examination is on growth and development, sensory screening, dental examination and behavioural assessment. Beginning nurses will not normally perform this type of assessment. However, the following tips help beginning nurses to gather focused health assessment data.

• When obtaining histories on infants and children, you will need to gather all or part of the information from parents or guardians.

• Perform the examination in a non-threatening area and provide time for play so nurse and child can become acquainted.

• Because parents may think they are being tested by the examiner, offer support during the examination and do not pass judgment.

• Call children by their given name, and address the parent(s) using title and family name rather than given name.

• Always use open-ended questions to allow parents to share more information and describe more of the children’s problems.

• Interview older children and observe parent–child interactions. Older children can often provide details about their health history and severity of symptoms.

• Adolescents tend to respond best when treated as adults and individuals.

• Remember, adolescents have the right to confidentiality. After talking with parents about historical information, speak alone with adolescents.

Older adults

Health assessment of older adults should include an evaluation of mental status, review of family relationships, group involvement and religious and occupational pursuits (Ebersole and Hess, 2008). An important part of health assessment involves analysis of the basic activities of daily living (dressing, bathing, toileting, grooming, feeding and continence) and the more complex instrumental activities of daily living (using a telephone, preparing meals, managing money).

Characteristically, older adults present more blunted or atypical signs and symptoms. Do not discount slight changes in expected signs and symptoms (Meiner, 2011). Principles to follow during examination of an older adult include the following:

• Do not stereotype ageing patients. Most are able to adapt to change and learn about their health. Similarly, they are reliable historians.

• Recognise that sensory or physical limitations can affect how quickly you are able to interview older adults and conduct examinations. You may need to plan for more than one examination session.

• Perform the examination with adequate space; this is especially important for patients with mobility aids such as a walking stick or walker.

• Allow for pauses, and observe for details. Recognise normalities of later life that would be abnormal in a younger patient.

• Older patients may find giving certain types of health information stressful. Illness may be seen as a threat to independence and a step towards institutionalisation.

• Perform the examination near bathroom facilities. The patient may experience an urgent need to void.

• Be alert to signs of increasing fatigue, such as sighing, grimacing, irritability, leaning against objects for support and drooping of the head and shoulders.

Organisation of the examination

When performing a health assessment, information from the history is used to focus attention on specific parts of the examination. For example, if the history reveals symptoms of abdominal discomfort, the abdomen is also examined following a specific format. If the patient reports difficulties in performing basic activities of daily living, a focused assessment of the cardiac, respiratory, musculoskeletal and neurological areas is performed. The examination should be systematic and well organised so that important information is not omitted. The following tips will help you to prioritise aspects of your approach to health assessment.

• If a patient is seriously ill, first assess the systems of the body more at risk of being abnormal. For example, a patient with chest pain should undergo a cardiovascular assessment first.

• If a patient gets tired, offer rest periods between assessments.

• Compare both sides of the body for symmetry. A degree of asymmetry is normal (e.g. the biceps muscles in the dominant arm may be more developed than the same muscles in the non-dominant arm).

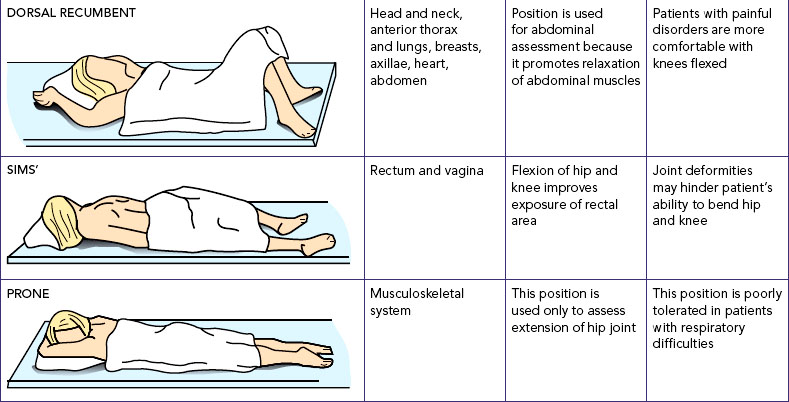

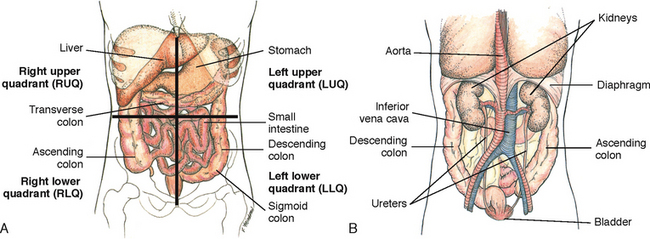

• Record results of the examination in specific anatomical and scientific terms so that any healthcare professional can interpret the findings (Figure 27-3).

• Use common and accepted clinical terminology and abbreviations to keep notes brief and concise.

• Record quick notes during the examination to avoid keeping the patient waiting.

• Document all assessment findings at the end of the examination.

GENERAL SURVEY

Assessment begins when you first meet the patient. Determine the reason the patient is seeking healthcare, and begin with a review of the patient’s primary health problems. As you do this, note the patient’s behaviour and appearance. The examination begins with a general survey of appearance and behaviour, vital signs and height and weight ratio. The survey provides information about characteristics of an illness, a patient’s hygiene and body image, emotional state, recent changes in weight, and developmental status. If abnormalities or problems are found, the affected body system is then closely assessed.

General appearance and behaviour

Assessment of appearance and behaviour begins as you prepare the patient for the assessment. The review of general appearance and behaviour includes the following.

Gender and cultural background

A person’s gender affects the type of examination performed and the manner in which assessments are made. Different physical features are related to gender and ethnic background.

Age

Age influences normal physical characteristics and the ability to participate in some parts of the examination.

Signs of distress

There may be obvious signs or symptoms indicating pain, difficulty in breathing or anxiety. These signs establish priorities regarding what to examine first.

Body type

Observe whether a patient appears trim and muscular, obese, or excessively thin. Body type can reflect the level of health, age and lifestyle.

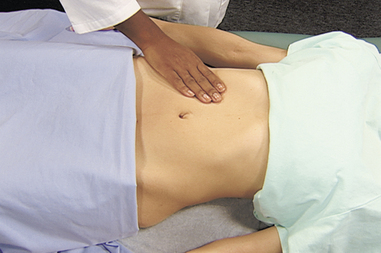

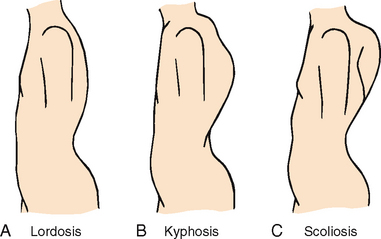

Posture

Standing posture is normally an upright stance with parallel alignment of the hips and shoulders. Sitting posture normally involves some degree of rounding of the shoulders. Observe whether the patient has a slumped, erect or bent posture. Posture may reflect mood or presence of pain. Many older adults assume a stooped, forward-bent posture, with the hips and knees somewhat flexed and the arms bent at the elbows, raising the level of the arms.

Gait

Observe the patient walking into the room. Note whether movements are coordinated or uncoordinated. A person normally walks with the arms swinging freely at the sides, with the head and face leading the body.

Body movements

Observe whether movements are purposeful and note if there are any tremors involving the extremities. Determine if any body parts are immobile.

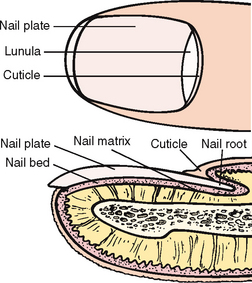

Hygiene and grooming

The patient’s level of cleanliness is noted by observing the appearance of the hair, skin and nails. Note whether the patient’s clothes are clean. Grooming may depend on the activities being performed just before the examination, as well as the patient’s occupation. Also note the amount and type of cosmetics used.

Dress

Lifestyle, socioeconomic level and personal preference affect the type of clothes worn. Note whether the type of clothing worn is appropriate for the temperature and weather conditions. Patients who have mental illness may be unable to choose appropriate clothing.

Body odour

An unpleasant body odour may result from physical exercise, stress, poor hygiene or certain disease states. Poor oral hygiene or oral or upper respiratory tract infections may cause bad breath.

Affect and mood

Affect is a person’s feelings as they appear to others. A person’s mood or emotional state is expressed verbally. Note whether verbal expressions match non-verbal behaviour and whether the patient’s mood is appropriate for the situation. For example, the mood is inappropriate if the patient seems unusually happy after recently being diagnosed with cancer. Observe facial expressions as questions are asked.

Speech

Normally speech is understandable and moderately paced, and shows an association with the person’s thoughts. Note whether the patient talks rapidly or slowly—abnormal pace may be caused by emotions or neurological impairment—or in a normal tone with clear inflection of words.

Substance abuse

Healthcare providers’ recognition of patients who abuse alcohol, prescribed medications or illegal drugs is typically poor. Several visits often reveal behaviours that can be confirmed with a well-focused history and physical examination. The patient should be approached in a caring and non-judgmental way, since issues of substance abuse involve both emotional and lifestyle issues. When abuse is suspected, ask general questions and then refer to more experienced members of staff or professionals specialising in the area of substance abuse.

Vital signs

Following on from general inspection and survey, the next stage of health assessment involves assessment of vital signs; this is discussed in Chapter 28. Although vital signs assessment is usually conducted in the first part of the physical examination, it will also be appropriate for you to measure specific vital signs in more detail during assessment of individual body systems. For example, the pulse is palpated for rate, rhythm and strength, but when performing a cardiac assessment a range of pulses are palpated and compared bilaterally.

Measurement of head and chest circumference

A more detailed assessment of infants and children requires measurement of the circumferences of the head and chest. A paper measuring tape is used to record the infant’s measurements at each health visit until 2 years of age, and then to measure the child’s head circumference until 6 years of age (Seidel and others, 2011).

Accurate measurements require placement of the measuring tape at the correct anatomical location. The tape is wrapped snugly around the child’s head at the occipital protuberance and supra-orbital prominence. This is the location of the largest circumference. The measurement is recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm and compared with growth charts.

A chest circumference can be compared with the head circumference to rule out problems in head or chest size. The measuring tape is firmly wrapped around the infant’s chest at the nipple line without causing a skin indentation. Measurement is taken midway between inspiration and expiration and read to the nearest 0.5 cm.

Mrs Marsaja, aged 85 years, was admitted to hospital with a fractured neck of femur. She was found on the floor of her bathroom where she had been lying for two days. On admission you note that she is excessively thin, very agitated and her hair is matted. While assisting her to transfer into bed you notice a very unpleasant body odour. She has been a widow for 5 years and now lives alone. She has no past medical history.

• CRITICAL THINKING

How does the general survey assist you in focusing the health assessment of Mrs Marsaja?

Nutritional–metabolic pattern

Nutrition and metabolism are compromised by disease, genetic disorders, injury and surgical and medical treatments. Hospitalisation and illness also put elderly people at risk of malnutrition (Webster and Healy, 2009. Nutrition and metabolism assessment considers the food and fluid intake of the patient and the indicators of how these meet functional needs.

Subjective assessment includes the patient’s description of dietary and fluid intake, use of dietary supplements, food preferences and requirements, eating patterns, ability to chew, nutritional knowledge and activity and exercise patterns. Questions are also focused on recent alterations in appetite, weight, presence of nausea/vomiting, condition of hair, skin and nails, and medications that may affect intake and activity and exercise capacity. Cant (2011) recommends use of a malnutrition screening tool to identify patients at risk of malnutrition. Physical assessment includes examination of the mouth, measurement of height and weight, and assessment of the abdomen, skin, hair and nails. The combination of the subjective and objective data will assist you to identify appropriate nursing interventions to support the person’s nutritional state. Alternatively, you may work collaboratively with other members of the healthcare team to determine collaborative interventions.

BOX 27-5 ALTERATIONS IN NUTRITIONAL STATUS VARY ACCORDING TO CAUSE: TYPICAL ASSESSMENT FINDINGS

MOUTH LIPS, GUMS, TONGUE AND TEETH

• Oral mucosa is swollen, dry and reddened (niacin, folate, vitamin B12 deficiency).

• The tongue may appear pale or raw; there may be swollen lips and cracks at the corner of the mouth.

• Reddening and cracking at the corners of the mouth (vitamin B6 deficiency).

• Teeth may show evidence of poor dentition, cavities.

Skin

• Dry, flaky, rough feel (B vitamins deficiency).

• Bruising, pinpoint haemorrhages (vitamin C deficiency).

• Oedema (protein–calorie malnutrition).

• Pallor (anaemia).

HAIR

• Dull, thin, sparse, coarse, easily plucked, changes in pigmentation (protein–calorie malnutrition).

Nails

• Spoon-shaped, ridges across the nail plate, brittle.

HEIGHT–WEIGHT RATIO

• Weight loss (protein–calorie malnutrition).

• Decreased muscle mass, and weakness (protein–calorie malnutrition).

Abdomen

• Ascites (protein–calorie malnutrition).

• Wound healing delayed (vitamin C, zinc deficiency).

OTHER

• Neurological: confusion, irritability (thiamine deficiency); ataxia (vitamin B12 deficiency).

• Cognitive impairment (protein–calorie malnutrition).

• Eyes; night blindness (zinc deficiency).

Adapted from Morley J, Thomas D, Kamel, H 1998 Nutritional deficiencies in long-term care. Ann Long-Term Care 6:183–191.

Mouth

The mouth is assessed (Table 27-6) to detect signs of overall health, determine oral hygiene needs and detect dehydration or chewing difficulties. Assessment of the mouth, lips and tongue will provide information for you to develop interventions for patients who are dehydrated, are on restricted intake or have experienced oral trauma that may affect their ability to maintain an adequate nutritional and fluid intake. To assess the oral cavity, a penlight, tongue depressor or a single gauze square is required. Gloves should be worn during examination of the mouth. Assessment of the oral cavity can also be made during administration of oral hygiene (see Chapter 34).

TABLE 27-6 NURSING HISTORY ORAL ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

| Do you wear dentures/retainer? Are they comfortable? |

Dentures must be removed to visualise and palpate gums. Ill-fitting dentures chronically irritate mucosa and gums |

| Have you had a recent change in appetite or weight? |

Symptoms may result from painful mouth conditions or poor oral hygiene |

| Do you smoke? |

Tobacco users have greater risk of mouth and throat cancers than non-users |

| Review daily alcohol intake |

Heavy drinkers appear to have greater risk of oral cancer.

Effects of alcohol are independent of tobacco use

|

| Assess dental hygiene practices, including use of fluoride toothpaste, frequency of brushing and flossing and frequency of dental visits |

Assessment will reveal if patient needs education and/or financial support

Periodontal disease has a higher prevalence in older adults who have history of high plaque build-up, use tobacco and visit the dentist infrequently

|

| Do you have pain when chewing or eating? If so, ask if mouth lesions are present, including duration and associated symptoms |

May be associated with broken tooth, tooth grinding or temporomandibular joint problems |

Lips

The lips are inspected for colour, texture, hydration, contour and lesions. With the patient’s mouth closed, view the lips from end to end. Normally they are pink, moist, symmetrical and smooth. Female patients should remove their lipstick before the examination.

Teeth

The quality of dental hygiene is easily determined by inspecting the teeth (Box 27-6). Ask the patient to clench the teeth and smile, which allows assessment of teeth occlusion. The position and alignment of the teeth are noted. The upper molars should rest directly on the lower molars, with the upper incisors slightly overriding the lower incisors. To examine the posterior surface of the teeth, have the patient open their mouth with the lips relaxed. A tongue depressor will be needed to retract the lips and cheeks, especially when viewing the molars.

BOX 27-6 CLIENT TEACHING DURING ORAL ASSESSMENT

OBJECTIVES

• Patient will practise proper oral hygiene measures and dental care.

• Patient will describe warning signs of oral cancer.

• Older adult will maintain normal solid food intake.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Discuss proper techniques for oral hygiene, including brushing and flossing (see Chapter 34).

• Explain the early warning signs of oral cancer, including a sore that bleeds easily and does not heal, a lump or thickening and a red or white patch on the mucosa that persists. Difficulty chewing or swallowing is a late symptom.

• Encourage regular dental examination every 6 months for children, adults and older adults.

• Identify older patients who have difficulty in chewing and changes in the teeth. Teach patients to eat soft foods and cut food into small pieces.

EVALUATION

• Ask patient to demonstrate brushing.

• Have patient identify when to have regular dental check-ups.

• Have patient identify the warning signs of oral cancer.

• Ask older adult to keep a diet record for 3 days.

Tartar along the base of the teeth, dental caries (cavities), extraction sites and tooth colour should be noted. Normal, healthy teeth are smooth, white and shiny. A chalky white discolouration of the enamel is an early indication of caries formation. Brown or black discolourations indicate the formation of caries. In the older adult, loose or missing teeth are common because of bone resorption, teeth often feel rough when tooth enamel calcifies and yellow or darkened teeth are common because of general wear and tear exposing the darker, underlying dentin.

Buccal mucosa and gums

Buccal mucosa and gums are pink, soft, moist and smooth. View the inner oral mucosa by having the patient open and relax the mouth slightly, and then gently retract their lower lip away from the teeth (Figure 27-4). The mucosa is inspected for colour, hydration, texture and lesions such as ulcers, abrasions or cysts. Retracting the cheeks facilitates an inspection for colour, oedema, retraction, bleeding and lesions of the gums (gingivae). This process is repeated for the upper lip. The cheek is palpated with one finger along the inner mucosa and the thumb along the outside cheek to check for deep-seated lumps or ulcerations. Gently palpate any lesions with a gloved hand, assessing for tenderness, size and consistency.

An increase in colour or hyperpigmentation is normal in 10% of the population after the age of 50 years. For patients with normal pigmentation, the buccal mucosa is a good site to inspect for jaundice and pallor. In older adults, the mucosa is normally dry because of reduced salivation. Thick white patches (leucoplakia) can be seen in heavy smokers and alcoholics, and should be reported because they can also be precancerous lesions. Individual or coalescent white deposits adhering to the mucous membrane of any part of the mouth which leave bleeding points when scraped off may be evidence of thrush (Candida albicans). Assessment for thrush is required in infants, the elderly and patients prescribed antibiotics, corticosteroids or immunosuppressant medication. Small, yellow-white raised lesions commonly seen on the buccal mucosa and lips are Fordyce spots, or ectopic sebaceous glands (Seidel and others, 2011).

The gums around the back molars should be viewed because this is a difficult area to reach when cleaning teeth. Healthy gums are pink, smooth and moist, with a tight margin at each tooth. In older adults the gums are usually pale. Using gloves, palpate the gums to assess for lesions, thickening or masses. There should be no tenderness on palpation. Spongy gums that bleed easily indicate periodontal disease and vitamin C deficiency. If the patient has loose or mobile teeth, swollen gums or pockets containing debris at the tooth margins, periodontal disease or gingivitis can be suspected.

Palate

The patient should extend the head backwards, holding the mouth open to facilitate inspection of the hard and soft palates for colour, shape, texture and extra bony prominences or defects. The hard palate, or roof of the mouth, is located anteriorly (Figure 27-5) and is whitish and dome-shaped. The soft palate, best seen while depressing the tongue with a tongue blade, extends posteriorly towards the pharynx. It is normally light-pink and smooth. A bony growth, or exostosis, between the two palates is common.

Tongue and floor of mouth

The tongue is examined for colour, size, position, texture and coatings or lesions. The tongue should be medium or dull red in colour, moist, slightly rough on the top surface and smooth along the lateral margins. The tongue is carefully inspected on all sides, and the floor of the mouth is checked. The under-surface of the tongue and the floor of the mouth are highly vascular (Figure 27-6). Extra care is taken to inspect these areas, which are common sites for oral cancer lesions. The patient lifts the tongue by placing its tip on the palate behind the upper incisors. Observe for colour, swelling and lesions such as nodules or cysts. The ventral surface of the tongue is pink and smooth, with large veins between the frenulum folds. Varicosities (swollen, tortuous veins) may be seen. Although common in the older adult, these rarely cause problems.

Assessment of tongue movement is also required. The patient first relaxes the mouth and sticks the tongue out halfway. When the tongue protrudes, it lies midline. The patient raises the tongue and moves it from side to side to test for tongue mobility (should move freely). Any deviation, tremor or limitation in movement may indicate poor hypoglossal nerve function.

Height and weight

A person’s general level of health can be reflected in the ratio of height to weight. Both measures are routine when patients are admitted to a healthcare setting, at health screenings and during medical assessments. Infants’ and children’s height and weight are measured to assess growth and development. In older adults, height and weight coupled with a nutritional assessment are important in determining the cause and treatment of any impairment in nutritional, eating and other functional activities (Box 27-7). Look for overall trends in height and weight changes.

BOX 27-7 DIETARY HISTORY FOR OLDER ADULTS

• Does the older adult need or have help in preparing meals?

• Are meals ever skipped?

• Are the required number of servings (based on age and activity level) from all food groups included in the daily diet?

• Does the older adult take nutritional supplements, such as multivitamins?

• Does the older adult take any medication affecting appetite or absorption of nutrients?

• Does the older adult have a special diet, or does the patient’s diet contain an unusual amount of alcohol, sweets or fried food?

• Does the older adult have problems chewing?

Data from Ebersole P, Hess P 2008 Toward healthy aging, ed 7. St Louis, Mosby.

A patient’s weight will normally vary nominally because of daily fluid loss or retention. The nursing history can help to focus on possible causes for a change in weight (Table 27-7). A weight gain of 0.5–1 kg in a day may indicate fluid retention problems. If the adult patient has lost more than 5% of bodyweight in a month or 10% in 6 months, the loss is significant. A downward trend in weight for a frail older adult may indicate serious reduction in nutritional reserves.

TABLE 27-7 NURSING HISTORY FOR WEIGHT ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

| Have you lost or gained weight recently? Over what period of time did this loss/gain occur? |

Determines severity of problem and may reveal whether related to disease process, change in eating pattern or pregnancy |

| If weight loss desired, describe your eating pattern, diet plan followed, usual daily calorie intake and appetite. |

Helps to determine appropriateness of diet plan followed |

| If weight loss undesired, what is your appetite like? Have you had any vomiting, diarrhoea, thirst, frequent urination, change in lifestyle or activity? |

Focuses on problems that may cause weight loss (e.g. gastrointestinal problems) |

Are you experiencing an increase in stress in your life?

What effect has that had on your eating patterns?

|

Lifestyle changes can contribute to weight changes |

| What medications are you taking? |

Weight gain or loss can be a side effect of the following medications: chemotherapy, diuretics, insulin, psychotropics, steroids, non-prescription diet pills or laxatives |

Patients should be weighed at the same time of day, on the same scale and in the same clothes to allow an objective comparison of subsequent weights. Although measuring bodyweight may seem routine, care should be taken to be certain of accuracy, since medical and nursing decisions (e.g. drug dosage determinations, lifting and positioning) may be based on weight. Patients capable of bearing their own weight use a standing scale. Electronic scales are automatically calibrated each time they are used. The patient stands on the scale platform and remains still and the weight is automatically displayed within seconds (Figure 27-7). Stretcher and chair scales are available for patients unable to bear weight. After being transferred to the scale, the patient is lifted above the bed by a hydraulic device and the weight is measured on a balance beam or digital display. Caution must be used when transferring patients to and from the scales.

When weighing infants, remove clothing and weigh in dry disposable nappies to ensure accurate readings. The weight (in grams) can be adjusted later for the weight of the nappy. The room should be warm to prevent chills. A light cloth or paper placed on the scale’s surface prevents cross-infection from urine or faeces. Place the infant in the basket or on the platform and hold a hand lightly above the infant to guard against accidental falls.

Different techniques exist for measuring the height of weightbearing and non-weightbearing patients. Patients able to stand remove their shoes. The patient is asked to stand erect with straight posture, and a measuring stick is placed horizontally at a 90-degree angle on the head (Figure 27-8). A non-weightbearing patient (such as an infant) is positioned supine on a firm surface. Portable devices are available that provide a reliable way to measure height. The infant is placed on the device, with the parent holding the infant’s head against the headboard. With the infant’s legs straight at the knees, the footboard is placed against the bottom of the infant’s feet (Figure 27-9). The infant’s length is recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm.

Once the height and weight measurements have been obtained, the body mass index (BMI) is calculated. The BMI is a standard measure of weight for height and an indicator of overweight, obesity or protein–calorie malnutrition. The BMI formula is:

BMI = (weight in kg) divided by (height in metres)2

Interpretation of BMI for adults (Department of Health and Ageing, 2011) is as follows:

| < 18.5 |

underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 |

normal weight |

| 25.0–29.9 |

overweight |

| 30.0–39.9 |

obesity |

| > 40 |

extreme obesity. |

Skin

Assessment of the skin can reveal a variety of skin conditions, including changes in oxygenation, circulation, nutrition, local tissue damage and hydration. Patients most at risk of significant skin lesions are those suffering from neurological impairments, chronic illnesses, orthopaedic problems, diminished cognitive and/or mental status, poor tissue oxygenation, low cardiac output, inadequate nutrition and immobility. Skin odours are usually noted in the folds of the skin, such as the axillae or under a female patient’s breasts. The skin is routinely assessed for colour, moisture, oedema, temperature, texture, turgor, vascularity and primary lesions. Without proper care, primary lesions can quickly deteriorate to become secondary lesions requiring extensive nursing care. Patients who develop a pressure injury, for example, can have a lengthened hospital stay (Chapter 30).

Table 27-8 shows some examples of questions that you could ask when doing a skin assessment. It helps to ask patients if they have noticed any lesions, what caused them, to describe any recent changes, describe how a lesion bothers them and outline all previous management of the lesion. Many patients react with fear and anxiety to rashes or other lesions. Cancerous lesions often undergo changes in colour and size (Box 27-8). Patients with abnormal lesions should be referred to a specialist because further examination may be required.

TABLE 27-8 NURSING HISTORY FOR SKIN ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

Do you have a history of changes in the skin: dryness, pruritus, sores, rashes, lumps, colour, texture, odour, lesion that does not heal?

Have you noticed any changes on a mole or lesion?

|

Patient is best source to recognise change. Skin cancer may first be noticed as a localised change in skin colour

Most skin changes do not develop suddenly. Change in character of lesion might indicate cancer. Bruising indicates trauma or bleeding disorder

|

| Do you have a tendency to burn easily? |

Age over 50; male; fair, freckled, ruddy complexion; light-coloured hair or eyes; tendency to burn easily are risk factors for skin cancer |

Do you work or spend excessive time outside? If so, do you wear a sunscreen?

Do you work with creosote, coal tar and/or petroleum products?

|

Exposed areas such as face and arms will be more pigmented than rest of body. Use of sunscreen is recommended by Cancer Council Australia.

Exposure to these agents creates risk of skin cancer

|

| If skin is dry, ask: How often do you bathe/shower? What type of soap do you use? |

Excessive bathing and use of harsh soaps can cause dry skin |

| Have you had a recent trauma to your skin? |

Injury can cause bruising and changes in skin texture |

| Do you have any allergies? |

Skin rashes commonly occur from allergies |

| Do you use cream, medication or home remedies on your skin? |

Incorrect use of topical agents may cause inflammation or irritation |

| Do you use tanning salons, use sun lamps or take tanning pills? |

Overexposure of skin to these irritants can cause skin cancer |

| Do you have a family history of skin disorders such as skin cancer or psoriasis? |

Family history may reveal information about patient’s condition |

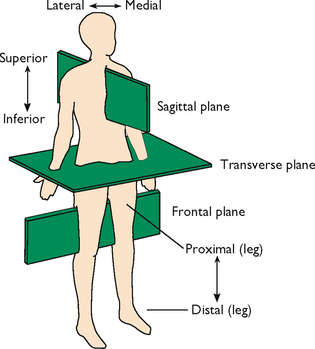

BOX 27-8 SKIN MALIGNANCIES

Illustrations from Belcher AE 1995 Cancer nursing. St Louis, Mosby; Habif TP 2009 Clinical dermatology: a color guide to diagnosis and therapy, ed 5. St Louis, Mosby; Zitelli BJ, Davis HW 2007 Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, ed 5. St Louis, Mosby.

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

• 0.5–1.0 cm crusted lesion that may be flat or raised and may have a rolled, somewhat scaly border.

• Frequently there are underlying, widely dilated blood vessels that can be seen clinically within the lesion.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

• Occurs more often on mucosal surfaces and non-exposed areas of skin, compared with basal cell.

• 0.5–1.5 cm scaly lesion, may be ulcerated or crusted. Appears frequently and grows more rapidly than basal cell.

MELANOMA

• 0.5–1.0 cm brown, flat lesion that may arise on sun-exposed or non-exposed skin. Variegated pigmentation, irregular borders and indistinct margins.

• Ulceration, recent growth or recent change in long-standing mole are ominous signs.

The physical assessment skills of inspection, palpation and olfaction are used to assess the function and integrity of the integument, which includes the skin, hair, scalp and nails. Initially either inspect all skin surfaces or assess the skin gradually while other parts of the body are being examined. You might need to incorporate cardiac and respiratory assessment when assessing the skin, since changes in breathing and circulation will often be reflected in the skin.

Illumination of the skin is required for accurate inspection. The recommended choice is natural or halogen lighting, but sunlight is best for detecting skin changes. Room temperature may also affect skin assessment. A room that is too warm may cause superficial vasodilation, resulting in an increased redness of the skin. A cool environment may cause sensitive patients to develop cyanosis around the lips and nail beds.

Inspection of the skin

COLOUR

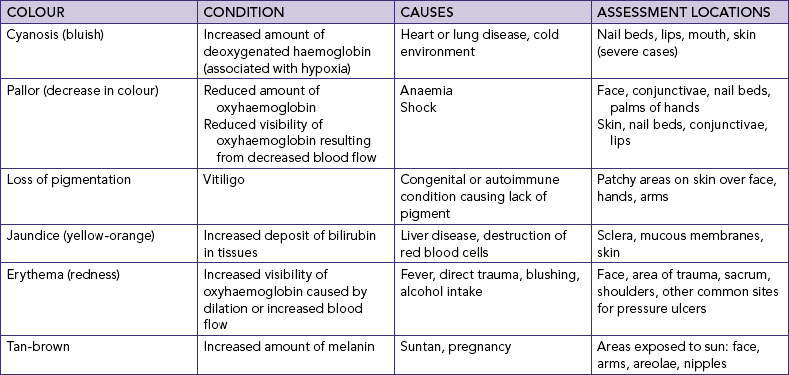

An initial, brief but careful, overall visual sweep of the entire body will give you a good idea of the distribution and extent of any lesions, as well as the overall symmetry of skin colour (Seidel and others, 2011). Colour varies from body part to body part and from person to person. Normal skin pigmentation ranges in tone from ivory or light pink to ruddy pink in light skin, and from light to deep brown or olive in dark skin. Despite individual variations (Table 27-9), skin colour is usually uniform over the body. Colour may be masked by cosmetics or tanning agents. Because you will inspect all skin surfaces, the patient must assume several positions. If abnormalities are seen during the examination, palpate the involved areas. The skin is normally free of lesions, except for common freckles or age-related changes such as skin tags, senile keratosis (thickening of skin), cherry angiomas (ruby-red papules) and atrophic warts.

The assessment of colour first involves areas of the skin not exposed to the sun, such as the palms of the hands. Note whether the skin is unusually pale or dark. Areas exposed to the sun, such as the face and arms, will be darker. Areas of increased colour (hyperpigmentation) and decreased colour (hypopigmentation) are common.

Inspect for any patches or areas of skin-colour variation. Localised skin changes, such as pallor or erythema (red discolouration), may indicate circulatory changes. In dark-skinned patients, because erythema is not easily observed, you need to palpate the area for heat and warmth to note the presence of skin inflammation. An area of an extremity appearing unusually pale may result from arterial occlusion or oedema. It is important to ask patients whether they have noticed any changes in skin colouring.

Cyanosis (bluish discolouration) is best observed in the lips, ear lobes, nail beds, palpebral conjunctivae and palms. The lips, nail beds and mucous membranes should also be assessed for generalised pallor; if pallor is present, the mucous membranes will be ashen grey. Cyanosis is a response to cardiopulmonary insufficiency. For further assessment detail refer to the activity and exercise section of this chapter, in particular cardiac and respiratory assessment. The best site to inspect for jaundice (yellow-orange discolouration) is the patient’s sclera and in regions exposed to pressure (sacrum and heels) for normal reactive hyperaemia (redness).

It is more difficult to note changes such as pallor or cyanosis in patients with dark skin. Usually colour hues are best seen in the palms, soles of the feet, lips, tongue and nail beds. Skin creases and folds are darker than the rest of the body in dark-skinned patients. Sites are inspected where abnormalities are more easily identified. For example, pallor is more easily seen in the buccal (mouth) mucosa, conjunctiva and nail beds. In dark-skinned patients, pallor in normal brown skin appears to be yellow-brown and in normal black skin appears to be ashen grey.

MOISTURE

The hydration of skin and mucous membranes helps to reveal fluid imbalances and changes in skin environment, and body temperature regulation. Moisture refers to wetness and oiliness. The skin is normally smooth and dry. Skin folds such as the axillae are normally moist. Increased perspiration may be associated with activity, warm environments, obesity, anxiety or excitement. Ungloved fingertips are used to palpate intact skin surfaces, but gloves are worn for breaks in the skin and obvious exfoliation. The skin should be observed for dullness, dryness, crusting and flaking. Flaking is the appearance of flakes resembling dandruff when the skin surface is lightly rubbed. Scaling involves fishlike scales that are easily rubbed off the skin’s surface. Both flaking and scaling are common in older adults, people who use excessive amounts of soap and in skin conditions such as eczema and dermatitis. Other factors causing dry skin include lack of humidity, exposure to sun, smoking, stress, excessive perspiration and dehydration.

OEDEMA

Areas of the skin become swollen or oedematous from a build-up of fluid in the tissues as a result of direct trauma or impairment of venous return. Oedematous areas should be inspected for location, colour and shape. Typical sites for dependent oedema caused by poor venous return are the feet, ankles and sacrum. The formation of oedema separates the skin’s surface from the pigmented and vascular layers, masking skin colour. Oedematous skin looks stretched and shiny. Palpate areas of oedema to determine mobility, consistency and tenderness. Pitting oedema is where pressure from the examiner’s fingers leaves an indentation in the oedematous area. Pressing the oedematous area firmly with the thumb for 5 seconds, releasing and then assessing the depth of pitting (in millimetres) determines the degree of oedema (Seidel and others, 2011). Record from 1+ to 4+, where 1+ oedema equals a depth of 2 mm.

TEMPERATURE

The temperature of the skin depends on the amount of blood circulating through the dermis. Localised erythema or redness of the skin may often be accompanied by an increase in skin temperature. A reduction in skin temperature reflects a decrease in blood flow. It is important to remember that if the room is cold, the patient’s skin temperature may be affected.

Temperature is more accurately assessed by palpating the skin with the dorsum (back) of the hand. Compare symmetrical body parts. Normally the skin temperature is warm. Skin temperature may be the same throughout the body, or may vary in one area. Assessment of skin temperature is always done for patients at risk of having impaired circulation, such as after a plaster cast application or vascular surgery. In addition, you can identify a stage 1 pressure injury early by noting warmth and erythema on an area of the skin (see Chapter 30).

TEXTURE

Texture refers to the character of the skin’s surface and the feel of deeper portions. Determine whether the patient’s skin is smooth or rough, thin or thick, tight or supple, and indurated (hardened) or soft by stroking it and palpating it lightly with the fingertips. The texture of the skin is normally smooth, soft, even and flexible in children and adults. The skin on the palms of the hand and soles of the feet tends to be thicker. In older adults, the skin becomes wrinkled and leathery because of a decrease in collagen, subcutaneous fat and sweat glands.

TURGOR

Turgor is the skin’s elasticity, which can be altered by oedema or dehydration. Normally the skin loses its elasticity with age. To assess skin turgor, a fold of skin on the back of the forearm or on the sternal area is grasped with the fingertips and released (Figure 27-10). Normally the skin lifts easily and snaps back immediately to its resting position. The back of the hand is not the best place to test for turgor, since skin is normally loose and thin there (Seidel and others, 2011). When testing skin turgor, note the ease with which the skin moves and the speed at which it returns to place. Slowness of the skin to resume its normal contour or shape and remaining pinched or tented may indicate dehydration.

VASCULARITY

The circulation of the skin affects the appearance of superficial blood vessels. With ageing, capillaries become fragile. Localised pressure areas, found after a patient has been in one position for a time, appear reddened, pink or pale (see Chapter 30). Petechiae are tiny, pinpoint-sized red or purple spots on the skin caused by small haemorrhages in the skin layers. Petechiae may indicate serious blood-clotting disorders, drug reactions or liver disease.

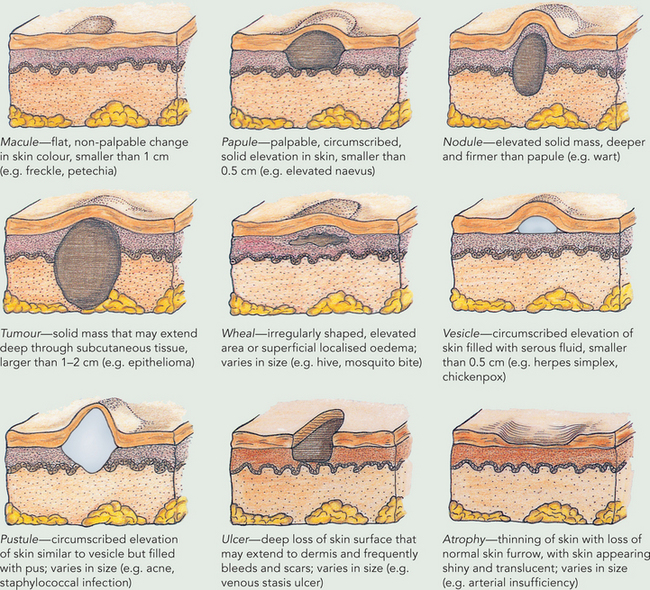

SKIN LESIONS

When a lesion is detected, it is inspected for colour, location, texture, size, shape, type, grouping (clustered or linear) and distribution (localised or generalised). Any exudate is observed for colour, odour, amount and consistency. Lesions should be measured in all dimensions (height, width, depth) when possible with a flexible ruler marked in centimetres.

Palpation determines the lesion’s mobility, contour (flat, raised or depressed) and consistency (soft or indurated). Certain types of lesions present a characteristic pattern. For example, a tumour is usually an elevated, solid lesion larger than 2 cm. Primary lesions, such as macules and nodules, arise from stimulus to the skin (Box 27-9). Secondary lesions, such as ulcers, occur as alterations in primary lesions. The lesion is firstly inspected then palpated gently, covering its entire area. If the lesion is moist or draining fluid, gloves are worn during palpation.

BOX 27-9 TYPES OF PRIMARY SKIN LESIONS

Abnormal findings of the skin

Lesions may be primary (occurring as initial spontaneous manifestations of a pathological process), such as the wheal of an insect bite, or secondary (resulting from later formation or trauma), such as a pressure injury.

Cutaneous malignancies are the most common neoplasms seen in patients. It is important to incorporate a thorough skin assessment on all patients with education about self-examination (Loescher and others, 2006) (Box 27-10). Australia has the highest incidence of malignant melanoma in the world, and its incidence is increasing. In 2008 melanoma caused 1437 deaths in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). It is especially prevalent in the tropical north. Melanoma accounts for 11% of all cancers diagnosed in Australia and is the third most common diagnosed cancer in men and women (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). In 2008, melanoma was the fourth most common cancer in New Zealand, with 2256 cases; in that same year there were 317 deaths from melanoma in New Zealand (Cancer Society of New Zealand, 2008). Basal cell carcinomas are another type of skin lesion. They are most commonly seen in sun-exposed areas and frequently occur in a background of sun-damaged skin. In older adults, pigmentation increases unevenly, causing discoloured skin.

BOX 27-10 CLIENT TEACHING FOR SKIN ASSESSMENT

OBJECTIVES

• Patient will perform a monthly self-examination of the skin.

• Patient will identify factors that increase the risk of skin cancer.

• Patient will follow hygiene practices aimed at maintaining skin integrity.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Teach patient to conduct a complete monthly self-examination of the skin, noting moles, blemishes and birthmarks. Show patient how to inspect all skin surfaces. Cancerous melanomas start as small, mole-like growths that increase in size, change colour, become ulcerated and bleed. A simple ABCD mnemonic outlines warning signals:

B.

is for Border irregularity; edges are ragged, notched or blurred

C.

is for Colour; pigmentation is not uniform

D.

is for Diameter; greater than 6 mm.

• Inform patient to report to their healthcare provider any change in skin lesions or a sore that bleeds or does not heal.

• Teach patient to prevent skin cancer by avoiding overexposure to the sun: wear wide-brimmed hats and long sleeves, apply sunscreens with SPF of 15 or greater approximately 15 minutes before going into the sun and after swimming or perspiring, avoid tanning under the direct sun at midday (10 am to 3 pm) and do not use indoor sunlamps, tanning salons or tanning pills. Medications such as oral contraceptives and antibiotics can make the skin more sensitive to the sun. Special care should be taken to protect children from the sun.

• To treat excessively dry skin, tell patient to avoid hot water, harsh soaps and drying agents such as rubbing alcohol. Use a superfatted (e.g. Dove) soap and pat rather than rub the skin after bathing.

• The patient should apply moisturisers (mineral oil) to the skin regularly to reduce itching and drying, and wear cotton clothing.

EVALUATION

• Patient performs skin assessment.

• Patient describes signs of skin cancer and measures to prevent skin cancer.

• Patient describes methods for keeping the skin lubricated and supple.