Current methods of contraception

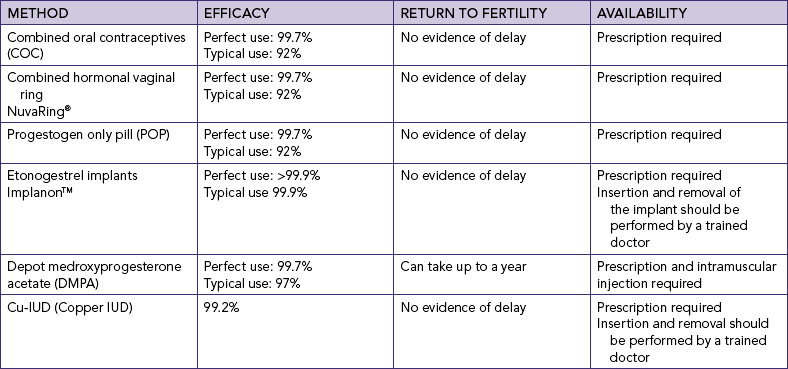

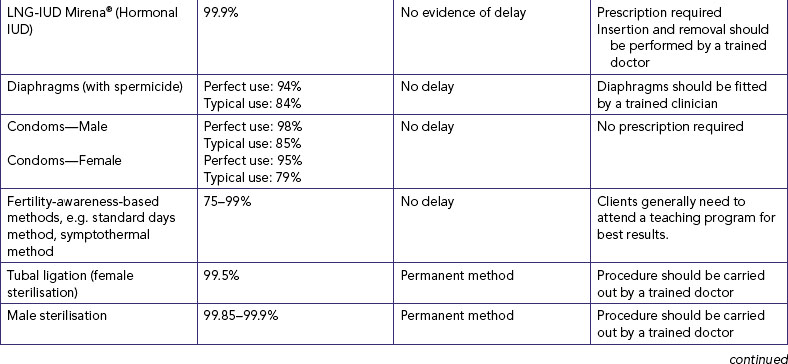

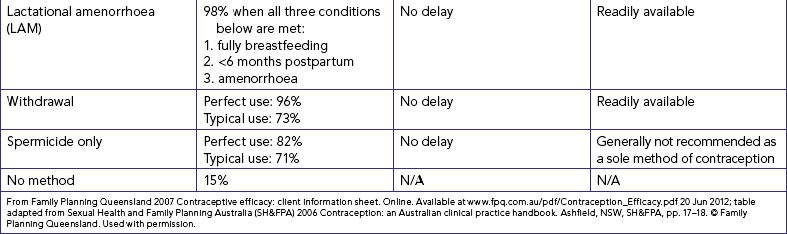

This section provides a brief introduction only to the methods of contraception available in Australia and New Zealand. There is no perfect method of contraception. For most methods, effectiveness depends on user compliance, which may be improved by information provision, counselling and the support of healthcare providers (Family Planning Queensland, 2007; see Table 24-2). Moreover, some medical conditions can affect the suitability of a particular method of contraception. Table 24-3 provides a summary of contraceptive methods for women with existing health problems.

TABLE 24-3 CONTRACEPTIVE METHODS FOR WOMEN WITH EXISTING HEALTH PROBLEMS

COC = combined oral contraceptive; DMPA = depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; EC = emergency contraception; GA = general anaesthetic; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IUD = intrauterine device; IUS = intrauterine system; LNG = levonorgestrel; POI = progestogen-only injectables; POP = progestogen-only pill.

Based on World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Geneva, WHO. Online. Available at www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9789241563888/en/index.html 9 May 2011.

Contraceptive prescriptions and advice are most commonly provided by general practitioners (GPs) and by nursing and medical staff in specialised organisations that provide contraceptive services, listed at the end of this chapter. A comprehensive assessment that takes into account the woman’s general health, financial circumstances, lifestyle, cultural and spiritual health and previous experience with contraceptive methods is integral to the selection of the most appropriate contraceptive method for her.

Fertility-awareness-based (FAB) methods

These methods, sometimes called ‘natural methods’ or ‘natural family planning’, use recognition of the changes in a woman’s body at various times of the menstrual cycle. They acknowledge that the estimation of the period of fertility needs to take into account the viability of sperm in the female genital tract—an average of 3–4 days with a theoretical possibility of up to 7 days—and the fertile period of the ovum, which is estimated to be 24 hours (Guillebaud, 2009).

Calendar (rhythm) method

The calendar method is the least reliable of these methods. It is based on the premise that ovulation occurs in the middle of the cycle and the fertile period lasts for six days—the five days before ovulation and the day of ovulation (Jennings and Arevalo, 2007).

Basal body temperature method

The basal body temperature (BBT) method is based on the fact that there is a drop in a woman’s body temperature 12–24 hours prior to ovulation, with a sustained rise for several days afterwards. Knowledge of temperature change is only useful in establishing when ovulation has already occurred over several cycles and thus the infertile period in which safe intercourse can occur.

Cervical mucus charting (ovulation or Billings method)

In this method, the woman is taught to recognise her fertile days by both the appearance and the sensation of mucus at the vulva. The fertile mucus (Spinnbarkeit mucus) assists the sperm to enter the cervix and is produced under the influence of unopposed oestrogen in the follicular phase of the cycle (Guillebaud, 2009). It is likely that ovulation occurs within 1 day before, during or 1 day after the last day of abundant slippery discharge (Jennings and Arevalo, 2007).

Symptothermal method

This method incorporates cervical mucus observation and BBT as described previously, with additional indicators of ovulation. These include symptoms such as the recognition of the softening and lowering of the external cervical os at the time of ovulation by the woman palpating her cervix (Guillebaud, 2009). Additional symptoms which may occur around the time of ovulation include mittelschmerz pain caused by follicular rupture and resulting in symptoms such as dragging pain in the lower abdominal area, and rectal pain which may occur before, during or after ovulation. Other symptoms may include increased libido, mood changes, breast tenderness and tenseness.

Barrier methods

Barrier methods include male and female condoms and diaphragms, and are used only as they are required. Condoms, in addition to their contraceptive value, prevent the transmission of some sexually transmitted infections (STIs), discussed later in this chapter.

Male condom

This is a widely available and popular method of male contraception. Male condoms are one-use-only sheaths most commonly made of latex (rubber). Polyurethane (plastic) condoms are also available but are more expensive than latex condoms. They are thinner and have a higher breakage rate than latex condoms, although they provide a good alternative for individuals with allergies, sensitivities or personal preferences that might prevent the use of latex condoms (Gallo and others, 2006).

It is recommended that lubricants are used with male condoms. Only water-based lubricants should be used with latex condoms. Oils and creams can break down the latex and should not be used—these include vaginal products used to treat Candida albicans as well as oil-based lubricants like Vaseline, baby oil, massage oils and hand and body lotions. Oil-based lubricants can be used with polyurethane condoms. Care must be taken in the handling of all condoms to ensure that tearing does not occur at any time during their use.

Condoms are most effective against STIs to and from the male urethra. These include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), gonorrhoea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis and hepatitis B. They are less effective against STIs transmitted by skin-to-skin contact or contact with mucosal surfaces, for example genital herpes, human papilloma virus and syphilis, because the infected areas may not be covered by the condom (Warner and Steiner, 2007).

Female condom

The new-generation female condom (FC2) is a loose synthetic nitrile sheath that is inserted into the vagina. It has a ring at one end that fits into the vaginal fornices in contact with the cervix (in much the same way as a diaphragm) and an outer ring that is in contact with the vulva, preventing it from retracting into the vagina. As with male condoms, female condoms afford protection against several STIs (Guillebaud, 2009). Because they are made of synthetic nitrile rather than latex, they can be used with oil-based lubricants. In Australia, women should be referred to their local family planning and sexual health organisation (see Additional resources) for information about availability, which varies from state to state. Female condoms are also available from some online pharmacies. In New Zealand, female condoms are imported by the Family Planning Association and sold through clinics and by mail order.

Diaphragm

A diaphragm is a soft latex or silicone dome with a flexible metal ring encased in the rim. It is inserted into the vagina to cover the cervix (Cook and others, 2003). Diaphragms come in circumferences ranging from 70 mm to 90 mm and must be fitted by a medical practitioner or sexual health nurse. Although use of a spermicide with the diaphragm is recommended by manufacturers, spermicide is not currently available in Australia or New Zealand.

Intrauterine devices

The intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) is inserted into the uterus and left in situ, and when removed will provide prompt return of fertility. In Australia, the Copper-T 380a™ and Multiload Cu 375™ are available, both of which are copper-bearing. The Copper-T can be left in place for 8 years, and the Multiload for 5 years. In New Zealand, the Multiload Cu 375™ is available. The Mirena™ intrauterine system (IUS), a levonorgestrel (LNG) releasing system, is also available in Australia and New Zealand and has a 5-year life span. It releases 20 micrograms of LNG per day and blocks oestrogen and progesterone receptors, and also reduces sperm penetrability of the uterine fluid and cervical mucus. In addition to its contraceptive action, it is also effective in reducing menorrhagia.

Hormonal methods

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs)

COMBINED ORAL CONTRACEPTIVE PILLS

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs), commonly known as ‘the pill’, are an effective and popular method of contraception. COCs are a combination of synthetic oestrogen and progestogen in different amounts depending on the brand. COCs are either monophasic (all pills in the packet are identically active with the same strength of oestrogen and progestogen) or multiphasic. Multiphasic pill types include biphasic (two types of active pills in the packet; the oestrogen dosage and type remain constant and the type of progestogen changes between the two last weeks of the active pills) or triphasic (three types of active pills in the packet; the oestrogen level may remain constant or change with the progestogen component, and progestogen has three different levels in the three weeks of active pills) (Nelson, 2007).

Pills are taken each day at around the same time for the 21 active pills in the packet. For the remaining 7 days, which is also called the ‘pill-free interval’ or PFI, either no pills are taken or placebo pills are taken. A withdrawal bleed occurs during that time. An extension of the PFI week risks ovulation and thus the possibility of pregnancy should intercourse occur at that time. This means that every pill in the packet should be taken, and the woman needs to plan ahead so that she has a new packet ready to take at the end of the PFI. If women are hospitalised, they will need to be advised about how to manage their pill-taking to prevent pregnancy if any pills are missed.

PROGESTOGEN-ONLY PILL

The low-dosage progestogen-only pill (POP), also known as the ‘mini-pill’, provides the same amount of one of three progestogens (levonorgestrel, norethisterone or ethynodiol) in each tablet. It is suitable for women in whom oestrogen—and thus COCs—is contraindicated. The POP is taken every day with no PFI. Unlike the COC, which has a 12-hour leeway for the dose of active pills, POPs have to be taken within 3 hours of the same time each day. The action of POPs is via blocking passage of sperm by thickening the cervical mucus, inhibiting ovulation in a variable proportion of cycles, and decreasing endometrial receptivity (Raymond, 2007a). As with the other progestogens, bleeding patterns may be altered during POP use, although amenorrhoea is likely during lactation (Guillebaud, 2009). If women are hospitalised, they will need to be advised about how to manage their pill-taking to prevent pregnancy if any pills are missed.

Hormonal vaginal contraceptive ring

The hormonal vaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing™) is the newest method of contraception available in Australia and New Zealand. This form of contraception releases 120 micrograms of etonorgestrel and 15 micrograms of ethinyloestradiol from a soft, flexible plastic ring (outer diameter of 54 mm) inserted into the vagina. Its action is to suppress ovulation, with other likely actions being to increase cervical mucus viscosity and endometrial thinning (Nanda, 2007). The ring is left in situ for three weeks and removed for the fourth week—the ring-free period. The ring is discarded and a new ring used after the ring-free period.

Injectable contraception

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), known as Depo-Provera™ 150 micrograms, is an intramuscular contraceptive injection that is effective for 3 months. It suits women who prefer a non-coitus-dependent method of contraception, but should be used in conjunction with condoms for women who are at risk for STIs. It is suitable for women who need a method that does not include oestrogen (e.g. a smoker, or where there is a history of thrombosis), women who have oestrogen-related side-effects from COCs or those who are taking medications that are contraindicated with COCs.

DMPA is administered by deep intramuscular injection into the gluteus maximus or deltoid. The woman is given the date for the next injection calculated as 3 calendar months from current injection, although there is a leeway of up to 14 weeks in which the next injection can be administered. The action of DMPA is to suppress ovulation by inhibiting the surge in LH and FSH, thicken cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, slow tubal and endometrial motility and cause thinning of the endometrium (Goldberg and Grimes, 2007).

Contraceptive implant

Implanon™ is a matchstick-sized progestogen-releasing rod, implanted under local anaesthetic parallel to the skin on the inside upper arm. It has a 3-year life span and high efficacy rate, and suits women who want a non-coitus-dependent method that is ‘set and forget’. The action, side effects and precautions related to the use of Implanon™ are the same as for DMPA. Implanon™ contains 68 micrograms of etonogestrel and releases 60 micrograms of progestogen per day. It acts by blocking passage of sperm by thickening the cervical mucus, inhibiting ovulation and making the endometrium atrophic (Raymond, 2007b).

Emergency contraception

Emergency contraception is an important and underused method of contraception that can be used for contraceptive failure (e.g. ruptured or slipped condom, missed pill(s), dislodged diaphragm), non-use of contraception, and sexual assault. It is a method of contraception that should be included as part of counselling for most contraceptive methods as well as be made more widely known about in the community (Calabretto, 2009). Hormonal emergency contraception (EC) is the main approach for EC (although the IUD can also be used). An important multicentre trial led to the current LNG-only method of EC (World Health Organization, 1998). EC is sometimes erroneously thought to be an abortifacient. It is important to understand that EC does not interrupt an already implanted pregnancy (Calabretto and Galloway, 2004). The regimen is 1500 micrograms of LNG in a one-dose pill taken within 120 hours of unprotected sex. The sooner it is taken, the more effective it is. The principal mechanism of action of LNG as EC is to inhibit or delay ovulation, with no demonstrated effect of an implanted ovum (ICEC and FIGO, 2011).

Other contraceptive methods

Lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM)

Breastfeeding can provide a natural contraceptive effect and can be used for contraception when a woman is exclusively or near-exclusively breastfeeding for the first 6 months following a birth, providing 98% protection against pregnancy if the following conditions are met:

• the woman must breastfeed both day and night, providing a minimum of 90% of the infant’s nutritional requirements

• she must be amenorrhoeic, and

• the infant must be under 6 months old (World Health Organization, 2010a).

Spermicides

Spermicides are chemical agents that destroy or immobilise sperm, making them incapable of fertilising an ovum. They are not recommended as a contraceptive alone, but are useful in increasing the efficacy of barrier methods such as diaphragms. Nonoxynol-9 is the active agent in most spermicides, and spermicides are effective against several STIs; however, they are not effective against the acquisition of HIV infection by women from men. Repeated and frequent use of this spermicide has also been associated with increased risk of genital lesions, and may actually increase the risk of HIV (Wilkinson and others, 2007). It is for this reason that condoms which come pre-lubricated with spermicide are no longer recommended; nor is the use of spermicides as a lubricant with condoms.

Vaginal douche

There is an erroneous belief that vaginal douching has a contraceptive effect by flushing sperm out of the vagina. Most sperm are contained in the first few drops of ejaculate, and sperm enter the cervical canal within 90 seconds of the deposit of semen at the cervical os. It is impossible to douche in time to prevent pregnancy, and douching may also cause an increased risk of pelvic infections. This practice should not be recommended (Cates and Raymond, 2007).

Coitus interruptus (withdrawal)

This is a method that requires the man to withdraw his penis from the vagina before he ejaculates. The method may variously be described as ‘withdrawal’, ‘being safe’ or ‘being careful’ or by other euphemisms (Varney, 1997). It is important to be aware of the meaning behind such descriptions when a woman discusses her contraceptive method. It has a low rate of contraceptive efficacy, although when used consistently and correctly it has the same efficacy as barrier methods and therefore should not be dismissed.

Permanent methods of contraception

These highly effective surgical methods block the passage of ova in women and sperm in men. Although reversibility may be possible for some procedures, sterilisation should be considered as permanent, and it is therefore important that appropriate counselling is provided so that expectations are accurate. None of the procedures affect the hormonal levels in the body, and will not diminish but may in fact enhance sexual response because the fear of pregnancy is removed. These techniques do not provide protection against STIs, and so use of condoms is needed for people who are at risk for STIs.

Tubal sterilisation

Female sterilisation, or tubal occlusion, is performed by a gynaecologist under conscious sedation or under general or local anaesthetic. The surgical approaches that may be used are laparoscopy, mini-laparotomy (performed after childbirth) or laparotomy. Once the fallopian tubes have been accessed, they are sealed off with clips, rings or bands applied to the tubes, or diathermy may be used to heat and seal the tubes. The method is effective immediately, and sexual intercourse may be resumed when the woman is ready to do so.

The newest method of female sterilisation—the Essure™ technique—is performed using a cervical block and leaves no abdominal scars. Nickel titanium microcoils are inserted hysteroscopically into the ampullae of the fallopian tubes to cause scarring, and thus blockage, of the tubes. At 3 months, a hysterosalpingogram or ultrasound is performed to confirm the presence and position of the coils (Teoh and others, 2003). Until the blockage is confirmed, another method of contraception must be used. At present in Australia, the Essure™ method is performed in a number of public hospitals under Medicare arrangements. Private health funds will cover the cost of the device and insertion but usually with a gap payment. In New Zealand the procedure can only be undertaken privately. Although it is the least-invasive method of female sterilisation, it is the least-commonly performed procedure at present.

Hysterectomy

Removal of the uterus for obstetric emergencies, cancer or gynaecological problems also confers permanent contraception.

Vasectomy

This is a male method of contraception where the ductus deferens is cut and the end sutured to block the ductus deferens and passage of sperm from the testes. There is local swelling and discomfort for a few days after the procedure. After vasectomy, sperm are reabsorbed. The procedure is usually performed under local anaesthesia, by a urologist, surgeon or GP. Following the procedure, between 15 and 20 ejaculations are needed for the remaining sperm to be expelled from the body, so additional precautions need to be taken until a semen analysis is done to confirm the absence of sperm in the seminal fluid.