Chapter 25 Loss, dying, death and grief

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define loss, grief, bereavement and mourning.

• Discuss the categories of loss.

• Describe normal grief patterns for adults.

• Describe normal grief patterns for children.

• Explain the physiological, social and psychological aspects of dying.

• Describe the key approaches to care and support for the dying person.

• Discuss the care of the body following death.

• Identify the ways nurses can address self-care in providing end-of-life care.

Birth, living, dying and death—this is the inevitable cycle of the human condition. Life brings with it the unavoidable experiences of change, with gain and loss in a dynamic relationship with each other. Some losses are seemingly innocuous—a change of school, the loss of visual acuity with age, the gradual distancing of friends over time; while others, such as the unexpected loss of employment, the destruction of a home in a natural disaster or the death of a family member, are clear, tangible and often traumatic events. Yet each loss, regardless of its apparent magnitude, brings with it a constellation of reactions that are both normal and laden with risk for those experiencing it.

Understanding the language and nature of loss and grief is an essential foundation to providing therapeutic benefits to those receiving nursing care. Confronting and engaging with the concept and reality of human mortality—that each of us will die—can enable us to appropriately support those in our care who are nearing the end of their lives. It is difficult to identify an area of practice where nurses will not encounter people who are nearing the end of their lives; it is not just the remit of palliative-care services or aged-care facilities to care for dying people. Learning and practising excellence in the clinical care of those dying and grieving can produce optimal outcomes for the most vulnerable in our communities. Acknowledging our own reactions to the losses we observe in others in the course of our nursing practice can empower us to ensure our self-care is effective. Compassionate and skilful nursing practice in loss, dying and grief provides an opportunity to promote the living to be done between birth and death.

Loss, grief, bereavement and mourning

No one is immune to the effects of loss at some time during the course of a lifetime. When nurses care for those who are experiencing reactions to loss, they will find wide-ranging behaviours and, perhaps, confronting encounters with people in distress. For many nurses these reactions are the source of concern, either through empathy for suffering of others or from a sense of inadequacy in dealing appropriately with the situation. For some nurses early in their practice, it can be tempting to rely on standard problem-solving techniques and responses learned by rote; but these may not always be possible or desirable in times of crisis. Frequent encounters with death have been found to be the most challenging and intensely personal experiences of those working in the healthcare environment (Currow, 2004).

Clearly, it is important for nurses to have an accurate understanding of the key terms in this field: loss, grief, bereavement and mourning. Sometimes these are colloquially used interchangeably, and certainly can be used in varying cultures and communities in different ways. However, the foundations for understanding rest in these definitions.

Loss refers to that state that exists when something to which one has an attachment is now gone. While commonly used to describe the experiences of people following the death of another person to whom they are emotionally or socially attached, it also applies to any loss experienced following detachment: for example burglary with theft of personal possessions; miscarriage; divorce; the loss of functional independence with chronic illness or injury; the loss of dignity, privacy and confidence that may accompany relocation into a residential-care facility. Types of losses are explored in more detail below.

The multifaceted assortment of reactions to the experience of loss is called grief. These reactions are complex, and experienced with interrelated physical, emotional, behavioural and cognitive aspects. Raphael (1999:22) once described grief as ‘an inevitable consequence of the intensity of human attachments’; it has been described as the price we pay for love and investing ourselves in others. Grief has the power to upset the body’s stability, which is vital to our sense of self (Freeman, 2005) and may manifest itself in ways that are disruptive and disturbing to the person experiencing it. Grief is both unique to each person and a highly complex sociological phenomenon. Grief varies enormously from one person to another and sometimes between men and women, and may be hindered or helped by the support offered. Descriptions of normal and abnormal grief reactions in adults and children follow.

Bereavement is a term referring to the objective state of having lost attachment to something of value; it is situational and tangible. In Australia and New Zealand, the word is largely used to apply specifically to a person who has a relative or friend who has died, although this usage varies. Thus it is possible to refer to someone as ‘bereaved’—such as a widow or widower—who may not be actually ‘grieving’ if their adjustment to their changed circumstances has resolved.

The cultural and social practices around the expression of grief and bereavement are collectively known as mourning. These are influenced by culture, religious affiliation, family expectations, personality and other factors. Mourning typically possesses a ritualistic quality. Martin and Doka (2000) indicated that ritual is best defined as ‘special acts that offer sacred meaning to events’. Funerals are rituals; they provide visual confrontation of the death, social support, a safe haven for the bereaved, rites of passage for the deceased and a way of disposing of the body. For thousands of years people have relied on some form of ritual to mark human death and fulfil vital psychological, spiritual and social needs of the bereaved. Ceremonies have formed part of mourning and burial rituals for tens of thousands of years of human history (Howarth, 2007; Kellehear, 2007).

In recent decades traditional forms of mourning have become less prevalent, with more informal and secular practices increasing in popularity. For example, in Australia and New Zealand fewer people are opting for church funerals; instead, secular events facilitated by a civil funeral celebrant in non-consecrated settings are seen more often. While predominantly secular in nature, these ceremonies can still have ritual power—recent incidents of mass death of younger persons, such as in the 2003 Bali bombings, saw secular mourning rituals played out on football fields and in ‘surf circles’ throughout the region (Rosenberg, 2009).

Categories of loss

It can be helpful to think about different categories of loss; it can be seen from these descriptions that loss may take many forms and does not simply describe the loss of a person through their death. Understanding these categories of loss enables the nurse to anticipate the likely lived experience of the client. This in turn can enable the nurse to respond appropriately and sensitively to the client’s reaction to their loss.

• Actual loss describes the change to a person’s situation that follows when something to which one has an attachment is now gone. For example, bereavement is usually a description of the actual loss of a person through death, such as a spouse, partner, family member or friend.

• Perceived loss is more difficult to identify, as it is less obvious to the observer. The loss of dignity, modesty, confidence, prestige or self-esteem are all examples of perceived losses. It is easy to see how a client in an unfamiliar hospital setting might react to these perceived losses and their subsequent vulnerability.

• Maturational loss occurs as a result of normal life transitions. For instance, when a child goes to school for the first time, the sense of loss may be profound for both child and parents. The loss experienced upon retirement may weigh heavily on the person whose sense of identity has rested on their role as primary wage earner.

• Situational loss occurs in response to sudden, unpredicted and specific events that have the capacity to threaten and immobilise a person’s physiological, psychological and social equilibrium. Some frequently documented and commonly encountered situational losses include divorce, separation from the family, childbirth, life-threatening or chronic illness, and death. Situational loss also includes the multiple losses caused by natural disasters—such as flooding and fire—where survivors must deal with losses that are enough to overwhelm them and render them, their families and communities helpless.

Normal grief patterns for adults

People’s reactions to loss are varied and highly individual; however, a number of patterns can be identified that are considered ‘normal’. Sadness, anger, fear, anxiety and denial are common reactions to loss and can sometimes represent adaptive responses to stress. It is, however, important to note that the grieving person does not necessarily experience all of them. Freeman (2005) and Corr and others (2003) suggest that responses from physical, behavioural, cognitive, emotional and spiritual domains may be manifested during the grief experience (Box 25-1).

BOX 25-1 MANIFESTATIONS OF THE GRIEVING EXPERIENCE

PHYSICAL

Hollowness in the pit of the stomach, tightness in the chest or throat, muscular weakness, lack of energy, dry mouth, insomnia, depression, generalised anxiety, loss of appetite, anhedonia (absence of pleasurable experience), sense of depersonalisation (‘Nothing seems to be real, including me’).

BEHAVIOURAL

Withdrawal from others, dreams of the deceased, searching and calling out, sighing, loss of interest in normal events, increased consumption of tobacco and alcoholic beverages, startled reactions, crying and difficulties sleeping, a wish for isolation, suspiciousness.

COGNITIVE

Preoccupation with the deceased, intrusive thoughts, disbelief, calculation difficulties, confusion, images about death, nightmares, decreased attention span, sense of presence and hallucinations, or decreased interest, motivation, initiative or direction.

There have been some groundbreaking grief theories that have helped us have better insights into the experience of people experiencing loss. The early work of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) introduced three significant concepts that influenced 20th century thinking about grief:

• a developmental perspective—that as children develop, they change in their reactions to loss

• the idea of grief work—the process of withdrawing emotional attachment to the object of loss, and

Freud’s work was influential in subsequent attempts to describe the experience of grief. An important contribution was made by John Bowlby (1907–1990), who proposed that a person’s reaction to loss is underpinned by a sense of violation of their attachment to the lost object. He went on to describe four phases experienced following loss: numbing, yearning, disorganisation and reorganisation; importantly, he noted that these phases do not happen in a set order, and this is an important concept to grasp in understanding grief (Cobb, 2008). Similarly, Colin Murray Parkes (1928–) explored grief as a transition between a world that is assumed to be known and stable, and one in which control is lost as the bereaved person adjusts to a new reality. Parkes also described phases, using the terms numbness, pining, depression and recovery, to describe normal patterns of grieving; again, he notes that these are not necessarily a linear process (Cobb, 2008).

Perhaps one of the best-known grief theories has emerged from the work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1926–2004), a Swiss-American psychiatrist who interviewed dying people to better understand their experiences as their lives came to an end (Kübler-Ross, 1969). In its application to bereavement, it proposes that people move through stages of grief not unlike the phases suggested by Bowlby; the theory gained tremendous traction both with healthcare professionals and with the general public, and is often assumed to be the most accurate description of ‘normal grieving’; however it has been strongly criticised because these stages have been assumed to take place sequentially. Payne and others 1999 have provided a comprehensive critique of this model.

In his pioneering work in the area of grief and loss, J. William Worden (1932–) proposed that the grieving person faces four ‘tasks of mourning’ that contribute to their adjustment to their loss:

1. to face the reality of the loss

2. to experience the pain of grief

3. to adjust to a world without the deceased

4. to emotionally relocate the deceased and move on with life in a new reality (Worden, 1991).

Importantly, over time Worden has amended this fourth task to reflect the ongoing nature of remembrance and so that ‘moving on’ or ‘getting over it’ is no longer the goal of mourning; rather, the adjustment to changed reality is an ongoing process. It has been rephrased as ‘to reinvest energy in life, loosen ties to the deceased and forge a new type of relationship with them based on memory, spirit and love’. More recently, Worden has modified this model to include consideration of meaning making, resilience and continuing bonds (Worden, 2009).

Think about an experience of bereavement in your life, and consider Worden’s ‘tasks of mourning’. Ask yourself the following questions; you may like to write down your answers for your own reflection.

To accept the reality of the loss:

1. How do you remind yourself that the loss you have experienced is real?

2. What reminders are there in daily life that your loss is real?

To experience the pain of grief:

3. What feelings, thoughts and sensations have you experienced since your loss?

4. How have they affected your ability to go about your life?

To adjust to the new environment where the deceased is missing:

To reinvest energy in life, loosen ties to the deceased and forge a new type of relationship with them based on memory, spirit and love:

Each of these attempts to describe the nature of grieving may be helpful, but should be used with caution by nurses. Indeed, some argue that applying standardised models of bereavement can be the source of depersonalised care that devalues the experience of the griever (Cobb, 2008). Grieving is a highly individual phenomenon, influenced by personality, culture, family and other contextual issues, and any model must not be considered prescriptive of the process. These models should thus be used to provide frameworks for understanding the experiences of loss and grief, rather than as some sort of ‘recipe’.

Grief and gender

Some discussion has taken place regarding gendered differences in grieving patterns (Millan, 2010; Rosenberg, 2009). Most cultures provide social sanctions for the expression of emotions such as sorrow and anger which often differ between men and women. Emotions expressed by people of one culture may not necessarily be sanctioned in another; for instance, in many Western cultures men have been socialised not to cry and society discourages men from the public expression of tears (Golden, 1996). A notable exception to these gendered expectations in Australia and New Zealand can be found in the sanctioned grieving and memorialisation on ANZAC Day, where fallen soldiers are commemorated and returned soldiers honoured; in this setting, the public expression of emotion by men in the context of grieving is considered acceptable (Rosenberg, 2009).

In Australia and New Zealand, then, certain assumptions about gender are popular: we have a stereotypical picture, for example, of the stoic, controlled man whose grieving is intensely private; we have an impression, perhaps, of the grieving woman who shares her feelings readily and finds great solace in the connections she makes in a grief support group. Are there are ways of grieving that are more ‘masculine’ or more ‘feminine’? Consider the assumptions listed in the critical thinking exercise below.

In your experience, do these assumptions about gender and grieving hold true?

| Women talk readily about feelings. | Men are stoic and appear to lack feelings. |

| Women tell and retell their stories to make sense of it. | Men know the story is etched in their mind; no need to be reminded. |

| Women seem to feel their way through grief—emotions are the pilot. | Men tend to think their way through grief—intellect is the guide. |

| Feminine language is often described as intuitive, earthy, fluid. | Masculine language is thought to be orderly, concise, controlled and goal-orientated. |

| Women focus on connection, intimacy and interdependence. | Men focus on independence, self-reliance, less self-disclosing, less expressiveness. |

| Women seek companionship, including groups. | Men appreciate time alone to think it through. |

| Women are more amenable to demonstrative expression of feelings in group work. | Men are more likely to benefit from being left alone to work through their grief. |

In reflecting on these assumptions, it would be fairly easy to identify a number of people for whom they simply don’t apply: a woman who is intensely private in her grieving, or a man who is demonstrative and open about his feelings of sadness. Most grieving people sit somewhere between the two, and it can be helpful to conceptualise grief patterns and gender along a continuum, rather than in two mutually exclusive boxes.

Yet this continuum is not ‘female  male’ or even ‘feminine

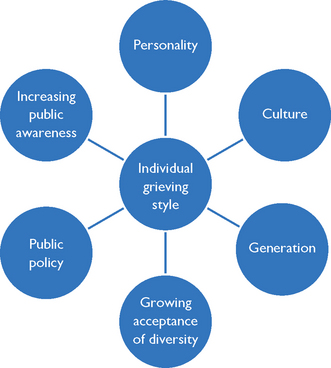

male’ or even ‘feminine  masculine’. Grieving is not really about gender, but about individual styles, and is in a constant state of change. Figure 25-2 illustrates a number of factors that influence how an individual might grieve; importantly, these factors themselves are dynamic and changing—for example, cultural norms around mourning behaviour in a second-generation Australian may have been modified by assimilation.

masculine’. Grieving is not really about gender, but about individual styles, and is in a constant state of change. Figure 25-2 illustrates a number of factors that influence how an individual might grieve; importantly, these factors themselves are dynamic and changing—for example, cultural norms around mourning behaviour in a second-generation Australian may have been modified by assimilation.

Individual grieving styles

Another way of understanding individual grieving styles comes from considering differing styles on a continuum ‘intuitive  instrumental’ (Figure 25-3). The characteristics of each end of this continuum are described below.

instrumental’ (Figure 25-3). The characteristics of each end of this continuum are described below.

• experiences intense feelings of loss

• will talk to process feelings

• demonstrates outward expressions such as crying and lamenting, which mirror their inner experience (‘wear your heart on your sleeve’)

• may experience prolonged periods of confusion, inability to concentrate, disorganisation and disorientation

An intuitive griever’s adaptation to loss is shown through their lived experience of grief and their expression of feelings; they typically benefit from connection with others, sometimes in groups. As many of these characteristics have been assumed to be ‘feminine’, some male intuitive grievers may seek validation that their grief reaction is ‘normal for a man’.

Intuitive grievers are at risk of slowing their own progress towards adjustment, as their empathy for others can distract them from their own needs. Moreover, as intuitive grievers rely on relationships and interconnection to navigate their grief, they can focus fully on this process at the cost of their health and usual activities.

At the other end of the continuum, the instrumental griever:

• experiences feelings, but these are less intense and less obvious

• tends not to cry, although may feel pressure to do so

• considers mastery of their feelings and recovery as important; controlling their behaviour is valued

• talks to process issues, not feelings

• commonly experiences brief periods of cognitive dysfunction—confusion, forgetfulness, obsessiveness

• Often has enhanced energy levels; ‘doing stuff’ is an outlet.

Instrumental grievers typically use problem solving as a strategy to enable mastery of their feelings and control of the environment in creating their ‘new normal’. Not always isolated, their connections with others can be made by ‘doing with’ rather than ‘sharing with’. Female instrumental grievers can be judged as ‘cold’ or ‘uncaring’ because their grieving doesn’t necessarily include crying.

The risk for instrumental grievers is that because their grieving style is less obvious, they can in fact be leaving their grief unattended to, and poor health outcomes can eventuate as a result. Significantly, both intuitive and instrumental grievers can experience prolonged periods of confusion, inability to concentrate, disorganisation and disorientation as a normal reaction to grief.

It is important to remember that while people will usually demonstrate predominantly one or the other tendency on this continuum, most sit somewhere in between, in a ‘blended’ mix of the two.

Normal grief patterns for children

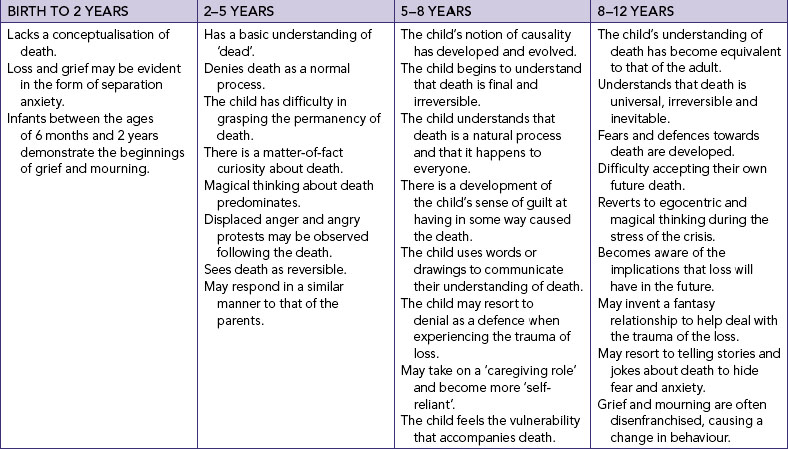

Understanding of death and responses to loss and death vary according to age. Like adults, children are not immune from grief reactions to loss and bereavement. Understanding the psychological and emotional development of a child is essential to the provision of support that is appropriate to each child’s developmental stage. Children experience age-related constraints on their ability to comprehend and deal with loss (Piaget, 1970). All children move through cognitive developmental stages in a set sequence; however, the rate of cognitive development varies among children. Although children may not totally comprehend the concept of death at an early age, it has been argued that they do experience separation anxiety and a perception of what it is to lose something or someone. As the child grows, an understanding of what it means to die develops (Table 25-1), and this conceptual understanding continues through middle to old age where the loss effect is diminished.

There are certain rules that govern the sequence of stages:

• children do not advance from one stage to another simply because it is their birthday

• children advance through each stage in the prescribed order

• children may exhibit cognitive aspects of both stages as they exit one stage and enter another

• adolescent children (and, on odd occasions, adults) may rely on lower levels of thinking even though they are capable of advanced reasoning

Personal experience is also an important component of human development. It is crucial to shaping an individual’s attitudes and behaviours, and this is particularly relevant in terms of each person’s experience with death, dying, grief and bereavement. Coming to terms with loss entails a personal quest by the survivor to make sense and meaning of the loss experience—consider Worden’s tasks of mourning discussed above. It is also a time for putting the loss experience into perspective, re-evaluating previously held knowledge, beliefs and attitudes, and moving on. This is largely influenced by how people perceive their social world and their place in it. During bereavement, four factors which develop throughout childhood, adolescence and young adulthood help condition emotional responses: personality, social roles, personal values and perception of the importance of the deceased.

Personality

Put simply, behaviour is the way one conducts oneself. The personalities of individual human beings are often consistent, and reveal qualities in their behaviour that in many respects can be predicted. For instance, some people will shy away in some circumstances where others will, perhaps, be aggressive, warm or outgoing. People have learned to count on certain behaviours in those they know, for example family members and close friends.

By assuming that a person will react in a certain way, the implication is that we have certain knowledge about that person’s personality. A working definition of personality is proposed by Clarke (1995) as ‘a dynamic compilation of instinctual emotional predispositions and psychological factors which, when combined, determine our unique adjustment to the environment’. Personality is unique to the person, yet relatively stable across a lifetime. It is a concept referring to the person as a unified whole and not just a part of the person (Peterson, 2004). If a person over the course of their lifetime has consistently run away during crises, then it is highly likely that person will behave in the same manner during a time of grief. Alternatively, a person with high esteem and self-concept and a positive approach is well placed for a healthy resolution in a grieving situation.

Social roles

Everyone has social roles they fulfil. In a family, everyone has interdependent roles, and members depend on one another for support, nurturance, guidance and social interaction. Following the death of a family member, losses resulting from the unoccupied role become apparent and are grieved for. Adaptation to the loss may become increasingly difficult as new roles are assigned and extra demands and new responsibilities are absorbed. It is a time for struggling with loss, and it is seldom clear at the time exactly what is lost. This can be particularly apparent if a person has lost a parent.

Personal values

A person’s value system represents personal beliefs and attitudes about the worth of different experiences and possible outcomes. Values are shared ideas about what is good, right and desirable, and are learnt in a number of ways, for example moralising (a direct but subtle way of inculcating preferred values in someone else), laissez faire (values are determined on an individual basis), modelling (the actions of someone else are copied) and value clarification (learners are taught the process of valuing). Everyday life situations that call for opinions, thought, decision making and action challenge each person. Each time a decision is called for, a choice has to be made based on the values that are held. A person’s values will have an enormous impact on that person’s experience of the death of another, as well as on their own death. Children will often mimic the apparent values of their parents, although as they move into adolescence they are more likely to adhere to peer-group values.

Perception of the deceased person’s importance

A further factor in the grief response is the importance of the deceased person, or the place the deceased person held in the survivor’s life. For adults, the loss of a spouse (for instance) may or may not mean the loss of a sexual partner, companion, accountant, gardener, baby-minder, audience, breadwinner, and so on, depending on the particular roles normally performed by this partner. In addition, relationships as complex as marriages vary in terms of the levels of loving or caring shared between the partners. For children, however, the loss of a parent can violate the child’s sense of safety, or remove a source of affection and direction; equally, the loss of a peer can confront a child’s sense of their own mortality and expedite their movement through elements of the developmental stages. Generally speaking, the closer the perceived relationship, the stronger the grief response.

Complicated or high-risk grief

There is some expectation in society that those who are grieving will eventually ‘get over it’ and return to their previous state of functioning; some people who are grieving become distressed when they don’t ‘feel better’ 12 months after the loss. However, rather than framing the outcome of grieving as ‘resolution’, it can be helpful to understand it, in the terms put forward by Worden, as the process of readjustment to a changed reality. For many people, however, this readjustment can be compromised by a number of factors that place them at high risk of ongoing emotional instability or withdrawal from usual tasks or activities that were once viewed as meaningful. It has been proposed (Payne, 2008) that the risk factors for complicated grief are influenced by:

• the circumstances of the death

• the meaning of the relationship with the deceased

• the internal resources of the bereaved, and

• the quality of social support and other external resources.

These are considered further below.

Many people in our society expect to live a long life with a peaceful death at its conclusion. The circumstances of the death may indeed follow this pattern; while this is the experience of only some, a number of people find themselves expecting the death of a family member or friend. In this case, anticipated death can provide opportunities to begin to adjust to the impending loss. Such deaths maximise the chances of uncomplicated grieving on the part of the survivors, although other factors interact with the nature of the death and this may not always be the case. For example, the nature of the relationship between the deceased person and the survivor may place a person at risk of complicated grieving.

Relationship between deceased and survivor can represent a risk factor for complicated grief. As noted above, the closer the perceived relationship, the stronger the grief response. The death of a spouse/partner disrupts all aspects of the survivor’s life—from the moment of rising to going to sleep in an empty bed. Habits of action (setting the table for two) and thoughts (‘I must ask my wife about that’) are confronted, sometimes daily. Grief following death is aggravated if the person lost is the person to whom one would turn in times of trouble; a widow may find herself repeatedly turning towards a person who is not there. Similarly, many widowed men feel isolated and alone in their grief. There is a feeling of being dismembered, of being acutely aware of the scope and dimension of the loss and that everything has changed. Further, there is painful self-examination and the tendency for physical and psychological health decline.

The death of a child is particularly difficult, as it ends plans, hopes and dreams for the child’s life. The death is regarded as being out of sequence and against the natural order of things. The death of a child, irrespective of age, gives rise to intense emotional and physical reactions and is identified in the literature as a ‘high-grief’ death.

On the other hand, the death of a parent represents the loss of a potential or actual long-term relationship. During the developmental years, children receive nurturing, support, care and protection, security, regulation of behaviour and socialisation from their parents. The loss of a parent signals a critical point in the life of the surviving children. It is a time for reflecting on the developing years and for reviewing the importance of relationships. It is also a time when grown children may become acutely aware of how old they are and that they are indeed adults. Perceptions about life and what it means may drastically change.

Disenfranchised grief occurs when people experience a loss that, for whatever reason, is not or cannot be socially sanctioned, publicly mourned or openly acknowledged (Corr, 1999). Such a concept recognises the notion of social control. All societies have systems of social control, whereby behaviours are socially and culturally defined. Mourning ‘rules’ exist in societies to ensure that their members generally behave in appropriate, expected and approved ways (DeSpelder and Strickland, 2005). There are four reasons the grief of survivors may be disenfranchised:

1. the relationship is not recognised

3. the griever is not recognised, and

4. the death is clearly affected by specific social values and attitudes (Bruce, 2000; Corr, 1999; Doka, 1989).

Consider the examples in Box 25-2.

BOX 25-2 DISENFRANCHISED GRIEF—EXAMPLES

• When others see the relationship between the bereaved and the deceased as relatively superficial or undeveloped, e.g. relationships between friends, a stillborn infant, colleagues, ex-spouses and caregivers, or non-traditional relationships such as same-sex partnerships and those involved in extramarital affairs.

• When the loss is one that falls outside everyday notions of loss, e.g. loss of a body part, the death of a pet, an elective abortion, or a miscarriage.

• When ‘psychological death’ occurs, e.g. if an individual’s personality drastically changes as a result of a chronic, debilitating mental illness such as Alzheimer’s disease.

• When, as Doka (1993) notes, those ‘individuals to whom the socially recognised status of griever is not attached’ experience loss, e.g. very young children, the elderly, people with intellectual disability or professionals who care for dying and distressed clients.

• When the death itself falls within areas of societal sexual taboos, e.g. death through human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The grief associated with this is complicated in many ways, both for the person infected by the disease and for significant others. First, every society carefully regulates the sexual behaviour of its members, and Benton (1999) makes it clear that HIV/AIDS has forced us to examine those aspects of life that are often taboo: sex, sexuality, blood, drugs and deviations from expected norms in lifestyles and behaviours. People whose relationships do not conform to society’s expectations, who live with and love those infected with the disease or who deviate from expected lifestyles and behaviours are forced to endure disenfranchisement, discrimination and stigma imposed by communities (Klein, 1999). Stigmatisation in itself creates multiple problems when it deprives the survivor of the opportunity to grieve the loss, and of support and religious rituals required for healthy confirmation of the death and subsequent mourning (Mooney, 1998).

• When the death comes about through suicide. Suicide is considered one of the most difficult deaths that a mourner must contend with, and is considered traumatic by its survivors. Suicide poses many difficulties in relation to grief resolution by significant others, as a sense of moral repugnance on the part of others may lead to the withdrawal of support for survivors (Noonan, 1999). Some proposed reasons for this reaction are the fear of death, fear of mental illness and fear of contamination by suicide. The survivors in turn may withdraw into themselves and become further isolated and choked by guilt (Corr and others, 2003).

Benton K 1999 Grief and HIV/AIDS: an Australian story. Grief Matters 2:3; Corr CA and others 2003 Death and dying; life and living, ed 4. Belmont, CA, Thomson Wadsworth; Klein SJ 1999 HIV/AIDS grief and mourning: unique and ongoing in spite of advanced treatments. Grief Matters 2:8; Mooney DC 1998 Disenfranchised grief: in the wake of suicide. Oral conference paper presented at Suicide—an enigmatic stigma: a journey through grief, Brisbane, Qld, 24 October 1998; Noonan K 1999 The truth hurts: the dilemmas of supporting children bereaved by suicide. Grief Matters 2:47.

When multiple losses occur, intense grief is experienced. Multiple deaths may be associated with the loss of two or more members of the same family at the same time in the same event, such as a multiple-fatality car accident. Alternatively, it may be associated with many deaths occurring within a relatively short period of time, such as the Black Saturday bushfires and the Lockyer Valley flood disaster in Australia or the Christchurch earthquakes in New Zealand. Multiple deaths cause multiple losses and have an immense impact, not only on the survivors, but also on family and the wider community.

In stark contrast to an anticipated death at the end of a ‘normal’ lifespan is sudden and unnatural death. Unexpected death by suicide, homicide, accident, injury or disaster is difficult to accept and has been found to be a precursor to poor psychological adjustment (Updegraff and Taylor, 2000). Surviving a disaster in which others have gone missing, are injured or have died presents unique grief responses for people. They survive not only the overwhelming, frightening and often sudden experience of the disaster and its aftermath, but also the death of others. ‘Survivor guilt’ is a term sometimes used in this situation to describe the feelings of those who, in all probability, would have also been victims.

Suicide remains a confronting experience in our communities. It is typically unexpected and premature, and seldom makes sense to those left behind. Suicide poses many difficult problems when it comes to healthy grieving by the victim’s significant others. Difficulty in coming to terms with the sudden death is considered by many researchers as the trigger for extreme difficulties with the bereavement experience and a disturbed kind of mourning by those left behind (Corr and others, 2003). This places survivors at high risk of physical and psychological health problems.

Following a death by suicide, significant others are often left feeling like victims themselves. Anger, shame, guilt, rejection and abandonment serve to strengthen negative grief responses (Mooney, 1998). Survivors are often left with a numbing feeling and ask themselves questions like ‘Why did he do this to me?’ Such questions and personal torment increase the impact of emotions. Suicide is often described as the ultimate affront, the final insult—one that, because it cannot be answered, compounds the survivor’s frustration and anger (DeSpelder and Strickland, 2005).

Rynearson (1996) suggests that following a homicide the survivors are at a high risk of complicated mourning and developing post-traumatic stress disorder. Not only is the death unexpected, senseless and random, but also it is brutal. Body mutilation and difficulties associated with retrieving the body following death tragically alter and further complicate mourning processes (Corr and others, 2003). For the survivor, anger and fear seem to predominate and can be exacerbated during a coronial inquiry into the death. Not only is the death difficult to comprehend, but also the grief is re-stimulated and compounded by events such as facing and identifying the accused, recollecting the event, court hearings, appeals, coronial proceedings and the intrusion of media into the event, as well as anniversaries and other significant events pertaining to family life. This can be particularly problematic following intrafamilial homicide.

How can we know when grief has moved from ‘normal’ to ‘complicated’? The Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement (2012) describes some of the possible features of complicated grieving. They suggest that further help may be required if the grieving person:

• does not have people who can listen to them and care for them

• finds themself unable to manage the tasks of daily life, such as going to work or child care

• finds their personal relationships are being seriously affected

• has persistent thoughts of self-harm or harming others

• persistently over-uses alcohol or other drugs

• experiences panic attacks or other serious anxiety or depression

• remains preoccupied and acutely distressed by grief over time

• feels that, for whatever reason, they need help to get through this experience.

Nursing practice and grief

The information provided above demonstrates that everyone grieves in their own way. Imposing inflexible or unfounded expectations on people experiencing grief can be inappropriate at best, and harmful at worst. Most importantly, time limits are unhelpful and, as Anstey and Lewis (2001) remind us, they cannot be considered as a valid outcome measure in determining successful adjustment. Mourning is a way of coping, is considered labour-intensive and unique and is regarded as a private and personal journey that no two people experience in the same way. Nurses have a responsibility to assess each situation as it arises, taking into account the many factors described above that lead a person to respond to loss in a particular manner. Nurses who understand the importance of grief and bereavement are better placed to facilitate grief work and help their clients and family survivors cope with their loss.

Supporting the grieving person

Most people’s grief reactions, while possibly uncomfortable to witness, can usually be considered a normal reaction to loss. Clearly not every nurse is going to be trained in grief and bereavement support; however, there are some fundamental attitudes and skills that promote optimal practice in the support of the grieving person.

Understand the therapeutic relationship

The primacy of the therapeutic relationship in palliative care nursing was identified by Canning and others (2007). While nursing practice is a set of activities requiring scientific knowledge and expert clinical skills, it is fundamentally also an interpersonal engagement with a therapeutic intent. Whether a death is sudden or anticipated, takes place in the home or the hospital, involves a baby, a child, an adolescent or a middle-aged or elderly person, it is nearly always the nurse who provides the final care and supports those most deeply affected by the loss. Sympathy, compassion and involvement have long been recognised as essential components of nursing care. A truly compassionate approach involves willingness to learn from others, viewing each situation as unique, responding to situations in an honest, sensitive and caring manner and taking the time to intervene sensitively and appropriately when caring for those who have experienced a loss.

Avoid judgment

Clearly, each person has their own approach to dealing with loss. The interpretation of loss is diverse and, as noted above, depends on such factors as cultural and ethnic heritage, socioeconomic status, gender and religious and racial perspectives. The concept of culture encapsulates those complex learned behavioural patterns that enable the individual or group to adopt specific habits based on a prescribed set of norms related to their daily conduct. In the Western world, grieving is often viewed as a very personal and private process. In many other parts of the world, such as India and the Middle East, public expression of grief is commonplace. The values and beliefs evident within a culture shape and direct an individual’s pathway through life, including religious, social and cultural sympathies. Although values and beliefs are not easily assessed, it is essential for nurses to understand the ways in which they are manifested through behaviour.

Maintain open communication

Remember that the grief behaviours witnessed by many nurses are not about the witness! Even when anger is being expressed, by approaching each situation in a non-judgmental way and being open and sensitive in communication with families, the skilled nurse conveys acceptance and represents commitment to the grieving person at a time when their sense of control may be compromised.

Stay informed of resources and support

It is not within the scope of practice of every nurse to be an expert bereavement counsellor. But staying informed of the resources and other forms of support available within the workplace and in the wider community is a reasonable expectation. The nurse should be able to access hard-copy materials or online resources that may assist the griever. A list of local psychologists or counsellors who are skilled in bereavement support can be an invaluable resource, as can an after-hours telephone support number in the griever’s community.

ASSESSMENT AND PLANNING

Assessment provides an opportunity for the nurse to explore with the client information relating to perceived and actual health problems. Grieving is a natural response to a loss and is considered to be a beneficial coping process. It is also a reactive process and has therapeutic value. Grieving is healthy and enables the bereaved to reflect on and accept the reality of the loss. The nurse must feel confident to assess the situation critically and make an initial needs analysis. The overall goal of the assessment is to gain a total view of the client’s health and psychosocial status by carefully exploring information gained from the interaction and collating the data in a precise and methodical way.

Both verbal and non-verbal communication techniques can encourage free flow of information and provide meaningful data for evaluation. These include listening, reflecting, clarifying, using non-verbal cues, appropriate use of silence, sharing perceptions, confronting contradictions and reviewing the discussions.

Culture and developmental considerations are two factors that influence communication. Culture has a profound effect on the way people communicate and behave. It is therefore important to keep in mind that cultural differences may influence how verbal and non-verbal messages are interpreted. For example, in many South-East Asian cultures—of which there are significant immigrant populations in both Australia and New Zealand—many women avoid eye contact with men. Conversely, many Western women look directly at the person to whom they are talking. Age or developmental level can also affect the way the assessment is handled, especially if the client is very young or very old. In the young, communication depends on the child’s cognitive maturity, as noted above. In the elderly, consideration must be given to the extent to which the memory and sensory function may be affected by the ageing process. There are times when both the young and the elderly, in particular, are hesitant to share personal information, and developing communication skills that maximise the possibility of open communication is a priority for student nurses.

During periods of loss or anticipated loss, a client’s emotions and behaviours may be in a state of flux; this makes assessment all the more difficult. Nurses should not assume they know how a client or family members will react. Continual assessment is essential if support and/or interventions are to be compatible with their current needs. Assessment of the client and family begins by exploring the meaning of the loss to the people involved. Examples of topics to be explored include the survivor’s model of the world, personal characteristics such as personality, values, the nature of family relationships, support systems, nature of loss, cultural and spiritual beliefs, loss of personal life goals, hope, phase of grief, risks and nursing role perceptions.

When interviewing the client and family, it is important that an honest and empathetic approach is taken. Be mindful of setting the tone and direction of the interview and of establishing a mutual understanding of the purpose of the exchange. In the initial phase it is important to establish rapport, ensure a comfortable and non-threatening setting and clarify the expectations or goals of the interview.

Establishing rapport

Establishing trust and rapport is a challenging process, particularly given the cultural diversity of Australian and New Zealand populations. A clear demonstration of respect for the client and an acceptance of the client’s uniqueness as a person facilitate rapport. Greet the client by name and introduce yourself. It is usual practice not to use the client’s first name unless invited to do so. In Australasian society, offering to shake hands is one way to demonstrate sincerity and acceptance.

Non-verbal behaviours

Non-verbal behaviours should match the verbal messages. Appropriate and sensitive eye contact and non-intimidating positioning should be used. Sincere and open eye contact (except in certain cultures/circumstances) is often vital with a vulnerable person, as normal contact with others may be disrupted by the emotions generated by the circumstances surrounding the death. Position yourself so that you are facing the client. If the client is seated, sit at a slight angle opposite but facing, with an appropriate distance between. Avoid non-verbal behaviours such as frowning or yawning, or expression of impatience or boredom, which imply a lack of interest. When beginning the interview, it may be appropriate to start with a brief but casual conversation that helps the client relax. Client-focused casual conversation may help alleviate any awkwardness the client may feel in talking to a stranger in the healthcare setting. Casual conversation can also be a source of valuable information.

Ensuring comfort

Ensure that the exchange of information takes place in a private setting free from interruptions and distractions. It is important to clarify that the client is feeling up to the interview before starting. Verbal therapeutic communication techniques involve open-ended questions that give the client a sense of control over the process—for example, ‘Tell me about your family’, ‘How you are feeling now?’ or ‘Can you tell me about the relationship from the beginning?’

Defining expectations

At the beginning of any interaction it is important to clarify what both the nurse and the client expect from the exchange. Make it clear that any information that is exchanged will be treated with sensitivity and respect; this is especially important in Australian Indigenous culture where the abuses of the past continue to have impacts on establishing trust in services.

During the assessment phase, it is important to focus on how the client is reacting, not on how you believe they should be reacting (Featherstone, 1997). Give special attention to grief-related behaviours displayed by the client, and pay careful attention to the client’s experience and the tasks of grief that may be left incomplete to threaten the client’s psychological or physical health. When people are in crisis they expect the nurse to meet them on an equal footing, so be honest, non-judgmental, open, compassionate and willing to listen. Dignity in the face of death and grief is also expected, and the nurse should accept emotional responses and personal disclosures in a non-threatening and accepting manner.

Clients’ responses to grief will vary, and depend on many factors. Remember that the bereavement models described above are guides only to help nurses understand the grieving pathway. For example, there may be times when a client becomes angry, does not seem happy with anything and takes it out on everyone, including the nurse who just walked in the door. In this situation, it would be easy to assess that the client is in the anger phase and the anger is not really directed towards the nurse but towards the situation. Of course, there could be any number of complex and interrelated factors contributing to the client’s anger. Rather than responding in a defensive or aggressive manner, the nurse should acknowledge the client’s feelings: ‘You’re obviously upset. I’m here to talk when you’re ready.’ It is important that the nurse remains available to clients, and that clients eventually understand that their outburst has not isolated them from support they may require later (Featherstone, 1997).

It is clearly within the scope of nursing practice to have a grasp of the issues that influence grieving. The information above can be distilled into a guide to the therapeutic conversation you can have with the client (Table 25-2).

TABLE 25-2 ASSESSMENT FACTORS FOR GRIEVING CLIENTS

| FACTORS | AREAS/SUGGESTED QUESTIONS TO EXPLORE |

|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | |

| Nature of relationships | |

| Social support system | |

| Nature of loss | |

| Cultural and spiritual beliefs | |

| Loss of personal life goals | |

| Hope | |

| Phases of grief | |

| Family’s grief for dying client | |

| Risk factors in survivors | |

| General health issues |

Grief work is unique to the griever and may take months or even years to adjust. Consideration by the nurse of the factors that influence grief reactions is necessary for planning and practising appropriate approaches to care. Grieving is an individual process and does not depend on a set schedule or follow a particular set of guidelines. It is important for clients and their families to share their concerns and talk about the experience with significant others. Continual evaluation of the care provided to clients and families by nurses is necessary for maintaining quality of life and facilitating a forum conducive to healthy grieving.

The physiological, psychological, existential and social aspects of dying

Palliative-care services and aged-care facilities are not the only settings of care where dying people are supported. Whether practising in midwifery, neonatal care, paediatrics, acute medical or surgical care, mental health, intensive care or accident and emergency, nurses will encounter dying people. The knowledge and skills required therefore are wide-ranging.

To understand the holistic nature of dying, it is essential to remember:

The experiences of serious illness, dying, caregiving, grieving and death cannot be completely understood within a medical framework alone. These events are personal, but also fundamentally communal. Medical care and health services constitute essential components of a community’s response, but not its entirety. (Byock, 2001:760)

In other words, your work as a nurse with a dying person and their family represents just one component of the whole experience of dying taking place. Most people try not to think about how and when they are going to die. There are, however, many changes that occur leading up to death. Sudnow (1967) made the influential suggestion that a dying person might move through four types of death: social, psychological, biological and physiological death; this suggestion has persisted and continues to underpin observations of withdrawal (Kellehear, 2007). Of course, these components are artificially separated for the sake of learning about them—in reality, all are experienced interdependently.

• Social death refers to gradual social withdrawal and represents the symbolic death of the person in relation to the world they have known. Both the individual and those who know them gradually drift away from one another.

• Psychological death refers to the death of aspects of the dying person’s personality. Regression and varying degrees of dependency may occur as the illness progresses. Grief over losses, both physical and symbolic, leads to psychological death. Medications and illness bring on biochemical changes within the body, sometimes leading to a personality change, changes in relationships, isolation and invalidation. Rando (1984) suggests that ‘In essence, the individual, as others know that person, dies.’

• Biological death is determined by medical criteria and refers to death in which the organism as a human entity no longer exists. The physiological changes experienced as a person nears death depend largely on the disease processes taking place. Historically, palliative-care services emerged from cancer care; however, in the past decade or so, an acknowledgement of the application of palliative-care principles and practices to end-of-life care for people without malignancy has become more evident (Addington-Hall and Higginson, 2001). For example, if you consider the most recently compiled primary causes of death in Australia, you will see that most people don’t die of cancer. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) reported that, in 2010, the leading causes of death in Australia were cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease (see Table 25-3). It is clear from this information that many of the leading causes of death were preventable, but it is important to note that a large proportion of Australian deaths are also predictable. That is to say, many of the people who died in 2009 were known to have had a disease or diseases that would inevitably lead to their death: cancer; chronic heart, lung, kidney or liver disease; dementia; and even stroke can have a trajectory where the death of the person can be predicted.

• Physiological death is the complete cessation of all vital organs. Death is recognised when respiration and cardiac action cease. The pupils of the eyes become fixed and dilated and the skin on the face and extremities becomes cool to the touch. The time of death should be noted and documented and the attending doctor or medical officer informed. However, physiological death is not clear-cut; it is debated whether a person is actually dead when, for example, they are on a life-support system with biological function but are considered ‘brain dead’.

TABLE 25-3 LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH IN AUSTRALIA 2010

| CAUSE OF DEATH | NUMBER OF DEATHS | RANK |

|---|---|---|

| Ischaemic heart diseases | 21 708 | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 11 204 | 2 |

| Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease | 9 003 | 3 |

| Trachea and lung cancer | 8 099 | 4 |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 6 122 | 5 |

| Colon and rectal cancer | 4 056 | 6 |

| Diabetes | 3 945 | 7 |

| Blood and lymph cancer (including leukaemia) | 3 933 | 8 |

| Heart failure | 3 468 | 9 |

| Diseases of the kidney and urinary system | 3 315 | 10 |

| Prostate cancer | 3 235 | 11 |

| Breast cancer | 2 864 | 12 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2 434 | 13 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 2 364 | 14 |

| Suicide | 2 359 | 15 |

| Skin cancers | 1 897 | 16 |

| Hypertensive diseases | 1 734 | 17 |

| Accidental falls | 1 648 | 18 |

| Cirrhosis and other diseases of liver | 1 592 | 19 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 1 535 | 20 |

Data from Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2012 Causes of death, Australia, 2010. Cat. no. 3303.0. Melbourne, ABS. Online. Available at www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3303.0 29 May 2012.

Key approaches to care and support for the dying person

The area of healthcare and nursing practice that specialises in the care and support of dying people and their families is called palliative care. Like grief and loss, the language and definitions of palliative care are continually evolving according to the cultural and social influences of the time. Nevertheless, there are some core definitions and themes of palliative care that have endured since the emergence of the modern hospice movement in the 1960s. The central goal of palliative care is to promote quality of life even when cure is unlikely or impossible. This is now a global message, articulated by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2011) in this way:

Palliative care is an approach that improves quality of life of clients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychological and spiritual.

The WHO (2011) also states that palliative care:

• provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

• affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

• intends neither to hasten nor to postpone death

• integrates psychological and spiritual aspects of client care

• offers a support system to help clients live as actively as possible until death

• offers a support system to help the family cope during the client’s illness and in bereavement

• uses a team approach to address the needs of clients and their families, including bereavement counselling if indicated

• will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness, and

• is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

In some settings where end-of-life care is provided by non-specialists, this care is referred to as the palliative approach. A palliative approach aims to improve the quality of life for individuals with a life-limiting illness and their families, by reducing their suffering through early identification, assessment and treatment of pain, physical, cultural, psychological, social and spiritual needs (Kristjanson and others, 2003).

In Australia, Palliative Care Australia is the peak national organisation representing the interests and aspirations of all who share the ideal of high-quality care at the end of life for all (see Online resources). The equivalent organisation in New Zealand is Hospice New Zealand (see Online resources), which has stated its core values as follows:

• Clients come first: every decision we make is based on this belief.

• Caring: we genuinely care about our people, clients and their families’ needs.

• Respect: we demonstrate respect in all our dealings with clients and families, recognising diversity.

• Professional: in all instances we will act professionally and with compassion.

• Determination: we are driven to work in partnership with our members and communities as guardians of the hospice philosophy.

These peak bodies inform their nations’ health services and communities about dying, death, grief and the role of palliative care. In Australia, Palliative Care Australia has developed the 13 national Standards for providing quality palliative care for all Australians (Palliative Care Australia, 2005); these are listed in Box 25-3 and describe the parameters for the organisation of palliative care services in Australia.

BOX 25-3 STANDARDS FOR PROVIDING QUALITY PALLIATIVE CARE FOR ALL AUSTRALIANS

1. Care, decision making and care planning are each based on a respect for the uniqueness of the client, their caregiver/s and family. The clients, their caregiver/s and families’ needs and wishes are acknowledged and guide decision making and care planning.

2. The holistic needs of the client, their caregiver/s and family are acknowledged in the assessment and care planning processes, and strategies are developed to address those needs, in line with their wishes.

3. Ongoing and comprehensive assessment and care planning are undertaken to meet the needs and wishes of the client, their caregiver/s and family.

4. Care is coordinated to minimise the burden on the client, their caregiver/s and family.

5. The primary caregiver/s is provided with information, support and guidance about their role according to their needs and wishes.

6. The unique needs of dying clients are considered, their comfort maximised and their dignity preserved.

7. The service has an appropriate philosophy, values, culture, structure and environment for the provision of competent and compassionate palliative care.

8. Formal mechanisms are in place to ensure that the client, their caregiver/s and family have access to bereavement care, information and support services.

9. Community capacity to respond to the needs of people who have a life-limiting illness, their caregiver/s and family is built through effective collaboration and partnerships.

10. Access to palliative care is available for all people based on clinical need and is independent of diagnosis, age, cultural background or geography.

11. The service is committed to quality improvement and research in clinical and management practices.

12. Staff and volunteers are appropriately qualified for the level of service offered and demonstrate ongoing participation in continuing professional development.

13. Staff and volunteers reflect on practice and initiate and maintain effective self-care strategies.

From Palliative Care Australia (PCA) 2005 Standards for providing quality palliative care for all Australians. Canberra, PCA.

Hospice New Zealand has developed a similar set of standards which can be viewed on their website (see Online resources).

Settings of care

In the same way that nurses will care for dying people in all sorts of fields, so too will dying people be found in many settings of care. The majority of people in Australia and New Zealand currently die in hospital. For many, this is an expected death in the course of treatment of chronic and progressive disease or its treatment. For others, it is the outcome of severe trauma or another lethal health event. In some hospital settings, non-palliative care clinicians are able to competently provide end-of-life care—many larger hospitals include a consultative specialist palliative-care service or even a sub-acute palliative-care unit, both of which provide specialist-level knowledge and care to hospital clients at the end of life.

A longstanding feature of modern palliative care is the presence of the hospice as a setting of care. Encapsulating the philosophy of palliative care, a hospice is not simply a building but a program of support that may include medical and nursing care, respite care and end-of-life care for those unable to be supported at home to die (Palliative Care Australia, 2008). Hospices are an alternative approach to traditional care. They are places where specially trained healthcare personnel care for people who are dying (Rumbold, 1998). The main reason for developing hospice-based services is a philosophy of care for the dying person that emphasises spiritual care, pain relief and control, and open communication between the dying person and carers. Physical, psychological, social and spiritual support underlies the philosophy. Although the guidelines may vary from state to state, it is generally accepted that a hospice will accept clients with a life expectancy of less than six months.

Home is, of course, a place of care for people nearing the end of life. In fact, most people in the final year of their lives will spend most of their time at home, not in hospital. Community-based palliative care, or the provision of a palliative approach by primary care providers such as general community nurses and general practitioners, is a key strategy in supporting dying people and their families. Nurses can play a vital role in helping the dying person and their family assess their situation and support infrastructure, and determine the adequacy of coping resources. Deteriorating health, anxiety and uncertainty about the future pose difficulties for the client and family, and they will benefit from support in the form of domiciliary nursing services, or a home care/outreach program or respite care. Respite care is a form of care that provides time out for the family while the client is cared for by a temporary caregiver. When the client dies, workers from the hospice team often visit the family. This is important for the survivor/s in grief work and eventually in making the transition to life without the deceased.

BOX 25-4 SUGGESTIONS FOR INVOLVING FAMILY IN THE CARE OF A DYING CLIENT

• Help plan a visit schedule for family members to prevent the client and family from becoming tired.

• Allow young children to visit a dying parent when the client is able to communicate.

• Be willing to listen to family complaints about the client’s care and feelings about the client.

• Help family members learn to interact with the dying person (e.g. using attentive listening, avoiding false assurances, conducting conversations about normal family activities or problems).

• Allow family members to help with simple care measures such as feeding, bathing and straightening bed linen. Recognise that family members are often more successful than nursing staff in persuading the client to eat.

• When the family becomes tired with care activities, relieve them from their duties so that they can get needed rest and support. Refer them to resources for meals and lodging.

• Support the mutual act of grieving by the client and family. Provide privacy when preferred. Do not discourage open expression of grief by the family and client.

• Provide information daily with regard to the client’s condition. Prepare the family for sudden changes in the client’s appearance and behaviour.

• Communicate news of impending death when the family is together, if possible. Remember that members can provide support for one another. Convey the news in a private area and be willing to stay with the family.

• As death nears, help the family stay in communication with the dying person through short visits, caring silence, touch, and telling the client of their love.

• After death, help the family with decision making, such as selection of an undertaker, transport of family members and collection of the client’s belongings.

Home care can be a challenging practice setting for nurses, who need to be able to work largely autonomously in a multidisciplinary team, without the immediacy of the hospital infrastructure, and comprehend the social nature of health and illness. Entering the home of another person, regardless of the intention to provide palliative care, places the nurse on another’s ‘turf’; the nurse is, in many ways, a visitor (Rosenberg, 2011). How visitors to the home are viewed is also subject to cultural variations; some ethnic groups in Australia and New Zealand have strong cultural practices regarding welcoming visitors, while others may consider privacy to be paramount. Of course, these differences can occur between households and are not solely cultural in nature.

Remember that the home is not always a place of loving kindness, supportive families and skilled family caregivers. Longstanding family conflicts, domestic violence, illicit drug use and other social problems can all be encountered by nurses practising in the home setting. Moreover, a small proportion of people dying at home have no family caregiver, or have an aged, perhaps frail spouse unable to cope with the physical demands of the caregiving role.

An increasing number of older persons spend the end of their lives in residential aged care facilities, or nursing homes. The Australian Department of Health and Ageing has provided Guidelines for a palliative approach in residential aged care (Department of Health and Ageing, 2006). These guidelines provide comprehensive information regarding the application of a palliative approach to support the dying older person in a residential aged-care facility:

• physical symptom assessment and management

• social support, intimacy and sexuality

• Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues

It is important to remember that not everyone who is dying lives in these various settings. People also do their dying in prisons, in shelters and public spaces and in boarding houses and hotel rooms.

What does ‘quality of life’ mean?

Whatever the setting of care, the goal during palliative and end-of-life care is to improve the quality of life for clients, their families and carers by providing care that addresses the many needs clients, families and carers have, including physical (including treatment of pain and other symptoms), psychological, social and spiritual care. The aim is to help the person live as well as possible, even in the presence of advanced illness and expected death. Support is also offered to help family and carers manage during the client’s illness and in bereavement. What ‘quality’ means in this context is typically defined by the client and their family or carers.

Advance care directives

As a person receiving care, the client is an important partner in planning their care and managing their condition. Family and carers also have an important role in this area. When people are well informed, participate in treatment decisions and communicate openly with their doctors and other healthcare professionals, they help make their care as effective as possible. Care planning is an important process in ensuring the client’s wishes, in relation to care, are met. Clients can anticipate their changing needs and specify their wishes for end of life care through advance care planning. This can be defined as a collaborative process between patients, families and healthcare providers during which preferences for future care are decided for when the patient is no longer able to articulate such wishes.

Advance care planning provides a mechanism to improve the quality of end-of-life care for people. It enables the coordination of their desired access to resources and services, to match their anticipated care needs (Tulsky, 2005). An advance care directive is the formal written documentation of this process. As with all aspects of palliative care, such approaches need to be tailored to the needs of the individual patient.

Discussions about appointing a substitute decision maker may also be important; this proxy decision maker is often referred to as the power of attorney.

NURSING ASSESSMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF CARE

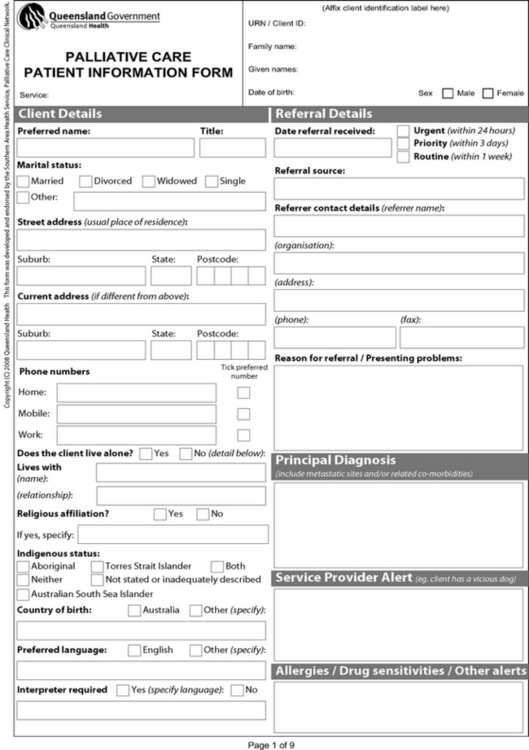

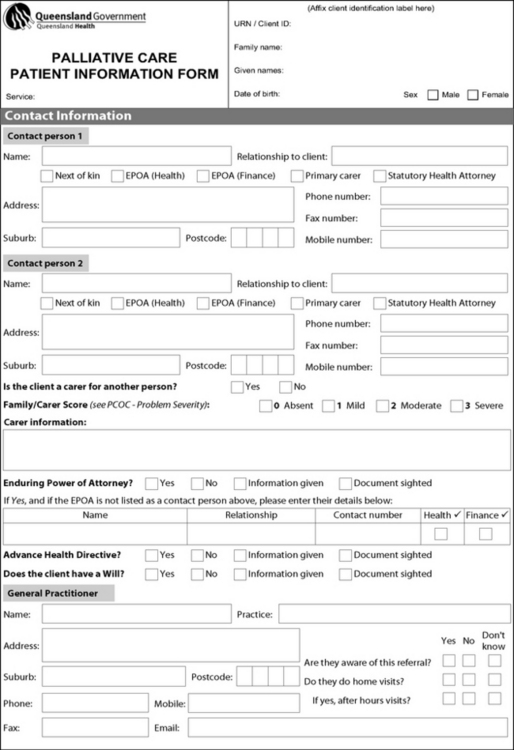

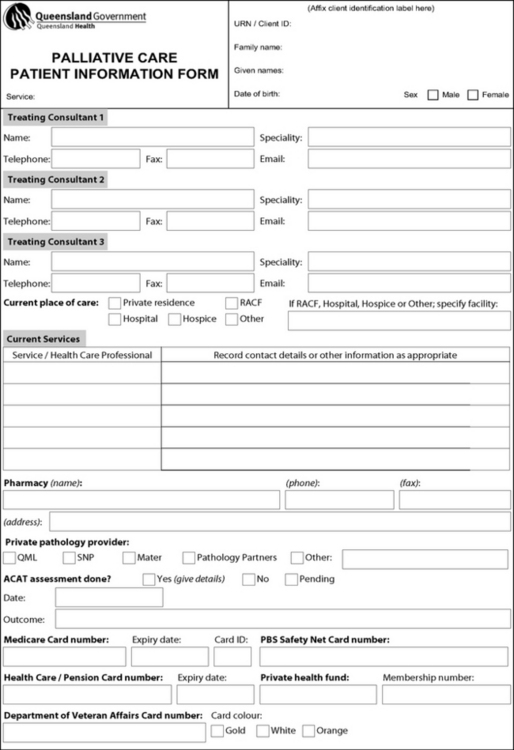

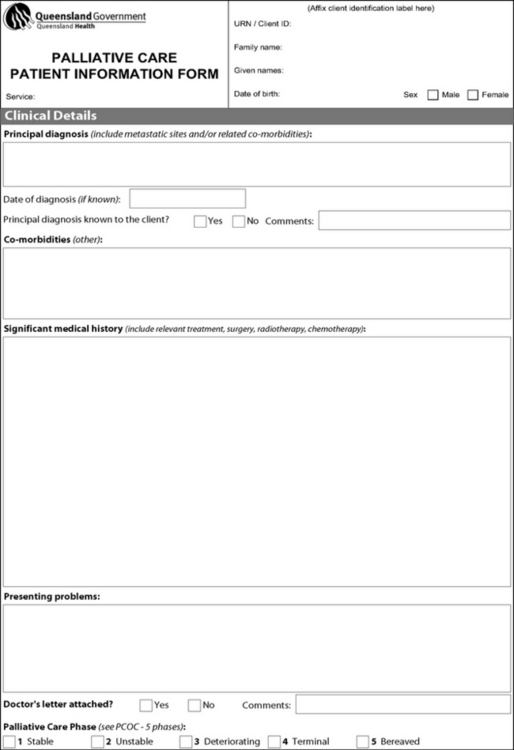

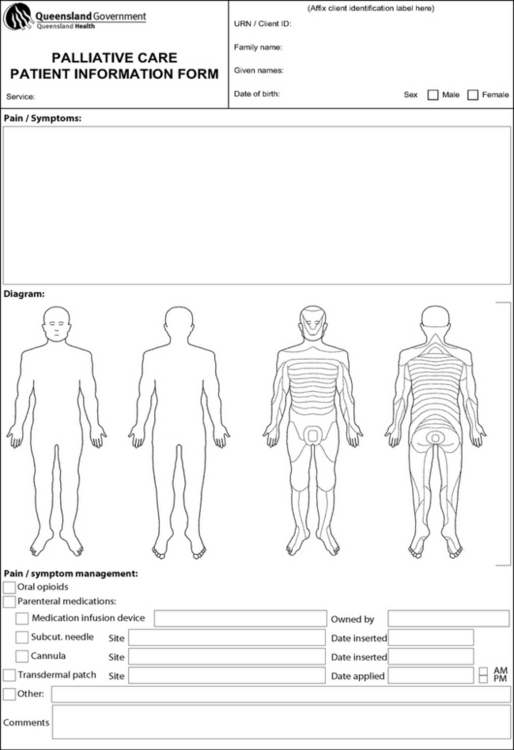

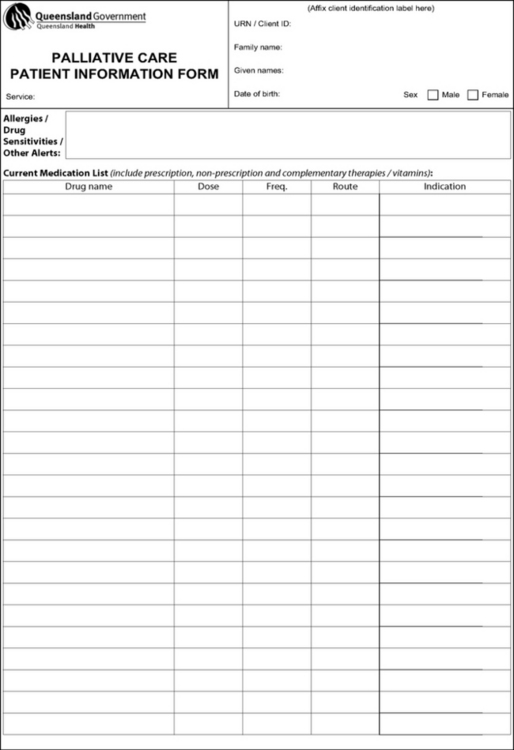

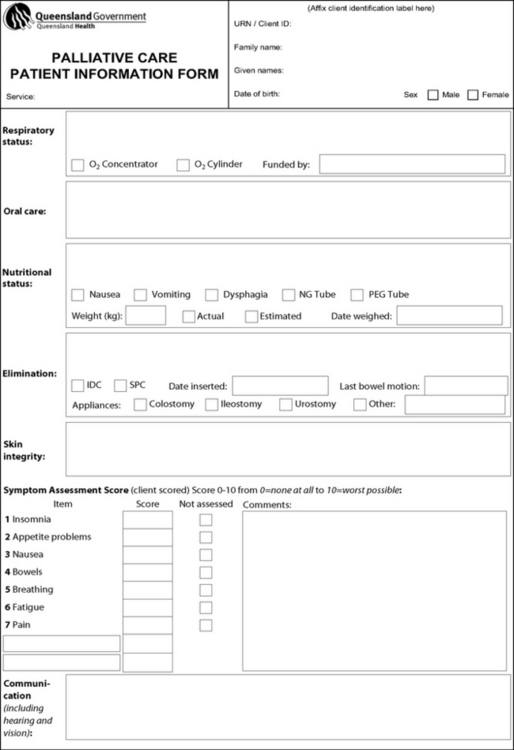

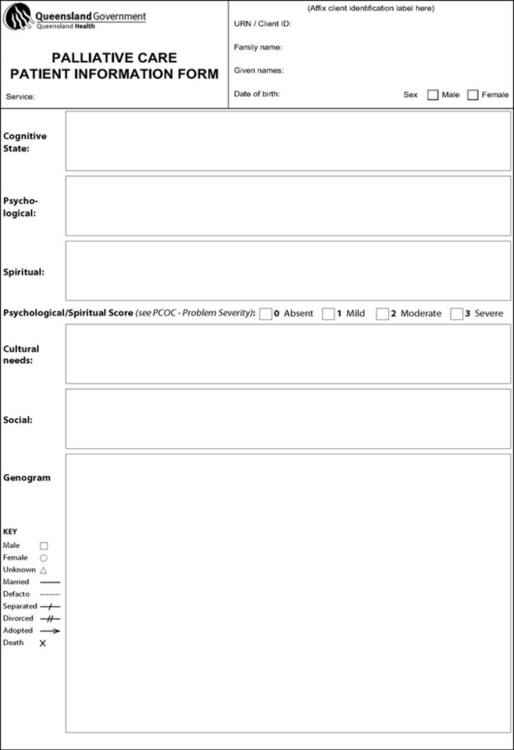

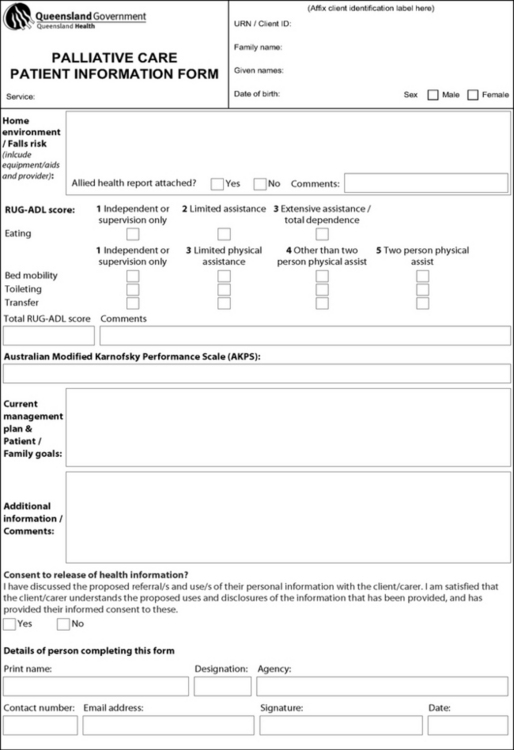

Impeccable assessment is a fundamental component of nursing practice in the care of dying people. There are many ways in which the clinical assessment of palliative-care clients can be documented; regardless of what is in use in each setting of care, a good-quality palliative care assessment tool will address the physiological, psychological, social and spiritual complexities being experienced.

One example of such an assessment tool is the 10-page Palliative care client information form from Queensland Health (Figure 25-4). It is a standardised electronic and hard-copy document that represents consensus best practice regarding admission data required for palliative clients managed across inpatient and community settings by public, non-government and private service providers. The form has been developed with the aims of:

• decreasing the need for unnecessary client re-assessment

• decreasing duplication of clinician effort

• facilitating seamless transition of care

© State of Queensland (Queensland Health), Brisbane South Palliative Care Collaborative (Metro South Hospital and Health Service/Griffith University School of Medicine). e-mail: bspcc@health.qld.gov.au

The form is used to record and confirm client information on admission to a palliative-care service and can also be used to transfer information during discharge and referral to other service providers as a means of facilitating the admission process for those services, and for the provision of feedback to service providers. This enhances communication regarding a client across the care continuum.

The likely benefits of utilising such a form include:

• smooth and timely transitions of client care across and within services

• standardisation of information collection and presentation across and within services

• improved clinical time efficiency

• its contribution to a basis for palliative-care data collection.

This form makes it obvious that the complex needs of many palliative-care clients require sound nursing interventions. These are the subject of detailed discussion in specialised palliative-care nursing textbooks; a brief summary of the main points is given in Table 25-4.

TABLE 25-4 PROMOTING COMFORT IN THE SERIOUSLY ILL CLIENT

| CHARACTERISTICS OR CAUSES | NURSING IMPLICATIONS | SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| PAIN | ||

| Pain can be acute or chronic (with acute exacerbations) |

Administer narcotic and adjuvant analgesics on a regular schedule (see Chapter 41) |

|

| Pain from advanced disease is often chronic |

Use combinations of analgesics or other therapies as client’s needs change Use relaxation, guided imagery, distraction and peripheral nerve stimulators to provide relief Administer narcotics as ordered (oral route for narcotics is preferred, but other routes including transdermal patches and continuous intravenous infusions are available) |

|

| Any source of physical irritation may worsen pain | Minimise irritants through skin care, including daily baths, lubrication of skin, frequent repositioning and dry, clean bed linen | |

| As client approaches death, mouth remains open, tongue and lips become dry and cracked | Provide frequent oral care every 2–4 hours. Use soft toothbrushes or foam swabs for frequent mouth care. Use plain water sprays or atomisers as desired. Artificial saliva products can be used. Apply light film of petroleum jelly to lips (see Chapter 34) | Mouth swabs containing lemon and glycerine exacerbate oral dehydration and are not recommended for use |

| Blinking reflexes diminish near death, causing drying of cornea | Remove crusts from eyelid margins and provide eye care. Reduce corneal drying with artificial tears | |

| FATIGUE | ||

| Metabolic demands of advanced disease cause weakness and fatigue | Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms in people with advanced disease, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders such as motor neuron disease and multiple sclerosis | |

| INEFFECTIVE BREATHING PATTERNS | ||

| Causes include disease progression involving lung tissue capacity, pneumonia, pulmonary oedema or anaemia | ||

| DEHYDRATION | ||

| As disease progresses, client is less willing or able to maintain oral fluid intake | Provide relief of thirst by using ice chips, sips of fluids or moist cloth to lips | |

| INADEQUATE NUTRITION | ||

| Nausea and vomiting can decrease appetite | Meals often have strong symbolic value in family—loss of appetite can cause distress as it represents the person’s inevitable deterioration | |

| NAUSEA AND VOMITING | ||

| Nausea and vomiting may result from disease process (e.g. gastric cancer), complications (e.g. bowel obstruction) or treatment, including medications | Nausea and vomiting are common side effects of narcotic analgesics | |

| CONSTIPATION | ||

| Narcotic medications and immobility slow peristalsis | Provide preventive care, including increasing fluid intake (e.g. bran, whole-grain products and fresh vegetables in diet) and encouraging exercise | Impeccable assessment of bowel function underpins improved outcomes for patients: a complete bowel history, with auscultation, palpation and digital rectal examination, are essential components of nursing assessment |