Chapter 34 Hygiene

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Describe factors that influence personal hygiene practices.

• Discuss the role critical thinking plays in the provision of hygiene care.

• Conduct a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s total hygiene needs.

• Discuss conditions that place patients at risk of impaired skin integrity.

• Discuss factors that influence the condition of the nails and feet.

• Explain the importance of foot care for the patient with diabetes.

• Discuss conditions that place patients at risk of impaired oral mucous membranes.

• List common hair and scalp problems and their related interventions.

• Describe how hygiene care for the older adult may differ from that for the younger patient.

• Discuss the different approaches used in maintaining a patient’s comfort during hygiene care.

• Successfully perform hygiene procedures for the care of the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, skin, perineum, feet and nails.

Maintenance of personal hygiene is necessary for a person’s comfort, safety and wellbeing. Well people are capable of meeting their own hygiene needs, but ill or physically challenged people may require assistance. A variety of personal and sociocultural factors influence the patient’s hygiene practices. The nurse determines a patient’s ability to perform self-care, and provides hygiene care according to the patient’s needs and preferences. In the home setting, the nurse helps the patient and family adapt hygiene techniques.

Because hygiene care requires close contact with the patient, the nurse uses communication skills (see Chapter 12) to promote a caring therapeutic relationship and to use the time with the patient for teaching and counselling. The nurse can integrate other nursing activities into hygiene care, including patient assessment and interventions such as range-of-motion exercises, inspection of pressure points or inspection and care of intravenous sites. While providing hygiene, the nurse must preserve as much of the patient’s independence as possible, ensure privacy, convey respect and foster physical comfort as well as dignity.

Scientific knowledge base

Proper hygiene care requires an understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the integument, oral cavity, eyes, ears, nose and perineal area. While administering hygiene, the nurse is able to apply this knowledge in recognising abnormalities and taking appropriate action to prevent further injury to sensitive tissues. The skin and mucosa cells exchange oxygen, nutrients and fluids with underlying blood vessels. The cells require adequate nutrition, hydration and circulation to resist injury and disease. Good hygiene techniques promote the normal structure and function of body tissues.

In addition to anatomy and physiology, the nurse applies knowledge of pathophysiology to provide good preventive hygiene care. The nurse learns to recognise those disease states that create changes in the integument, oral cavity and sensory organs. For example, diabetes mellitus may result in chronic vascular changes that impair healing of the skin and mucosa. In the early stages of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), fungal infections of the oral cavity are common. As a result of a cerebral vascular accident, paralysis of the trigeminal nerve eliminates the blink reflex, causing corneal drying. In the presence of conditions such as these and in patients with sensory impairment, the nurse adapts practices to anticipate hygiene needs and minimise any injurious effects (Huskinson and Lloyd, 2009).

The skin

The skin is an active organ with the functions of protection, secretion, excretion, temperature regulation and sensation (Table 34-1). The skin has three main layers: epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous. The epidermis (outer layer) is composed of several thin layers of cells undergoing different stages of maturation. It shields underlying tissue against water loss and injury and prevents entry of disease-producing microorganisms. The innermost layer of the epidermis generates new cells to replace the dead cells that are continuously shed from the skin’s outer surface. The epidermis also contains melanocytes, special cells that produce melanin or dark pigment of the skin. Bacteria commonly reside on the outer epidermis. These resident bacteria are normal flora (see Chapter 29) that do not cause disease but instead inhibit the multiplication of disease-causing microorganisms.

TABLE 34-1 FUNCTIONS OF THE SKIN AND IMPLICATIONS FOR CARE

The dermis is a thicker skin layer containing bundles of collagen and elastic fibres to support the epidermis. Nerve fibres, blood vessels, sweat glands, sebaceous glands and hair follicles course through the dermal layers. Sebaceous glands secrete sebum, an oily, odorous fluid, into the hair follicles. Sebum lubricates the skin and hair. There are two types of sweat glands: eccrine and apocrine. The eccrine glands are distributed throughout the skin. Sweat excreted from the eccrine glands assists in temperature control through evaporation. The apocrine glands can be found in the axillary and genital areas. The bacterial decomposition of sweat from these areas is responsible for body odour. In the ears, ceruminous glands secrete cerumen (earwax) into the external ear canal. This heavy, oily substance traps foreign material entering the ear.

The subcutaneous tissue layer contains blood vessels, nerves, lymph and loose connective tissue filled with fat cells. The fatty tissue is a heat insulator for the body. Subcutaneous tissue also supports upper skin layers to withstand stresses and pressure without injury. Very little subcutaneous tissue underlies the oral mucosa.

The skin often reflects a change in physical condition by alterations in colour, thickness, texture, turgor, temperature and hydration (see Chapter 28). As long as the skin is intact and healthy, its physiological function remains good.

The feet, hands and nails

The feet and hands are important to physical and emotional health. The structure of the foot is similar to that of the hand, with certain differences that adapt it for supporting weight (Thibodeau and Patton, 2007). The tarsals and metatarsals play the major role in the functioning of the foot as a supporting structure. Any injury or deformity to the foot, including any growths or injuries to the overlying skin, can be painful and thus interfere with a patient’s normal ability to walk and bear weight.

The hand, in contrast to the foot, is constructed largely for manipulation rather than support. A wide range of dexterity exists in the hand because of the wide range of movement between the thumb and fingers. Any condition that interferes with movement of the hand (e.g. superficial or deep pain, joint inflammation) can impair a patient’s self-help abilities.

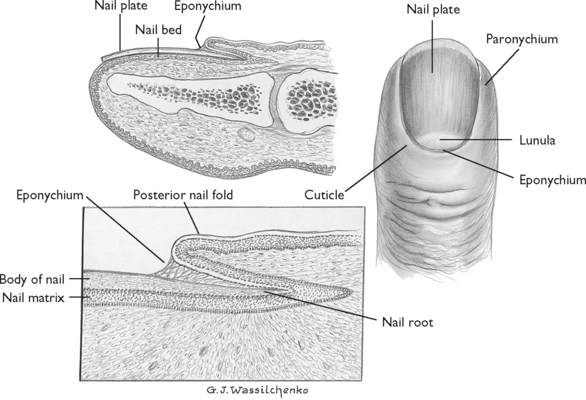

The nails are epithelial tissues that grow from the root of the nail bed, located in a groove hidden by the fold of skin called the cuticle. The visible part of the nail is the nail body. It has a crescent-shaped white area known as the lunula. Under the nail lies a layer of epithelium called the nail bed (Figure 34-1). The abundance of blood vessels in the nail bed creates its pink or light tan appearance (depending on race). Normally the nails grow about 0.5 mm a week, with fingernails growing faster than toenails (Thibodeau and Patton, 2007).

The oral cavity

The oral cavity is lined with mucous membranes continuous with the skin. The oral or buccal cavity consists of the lips surrounding the opening of the mouth, the cheeks running along the side walls of the cavity, the tongue and its muscles and the hard and soft palates. The oral mucosa is normally light pink and moist. The floor of the mouth and the undersurface of the tongue are richly supplied with blood vessels. Any type of ulceration or trauma can result in significant bleeding. There are three pairs of salivary glands that secrete about 1 L of saliva a day. The buccal glands found in the mucosa lining the cheeks and mouth secrete less than 5% of the total saliva; however, buccal gland secretion maintains the hygiene and comfort of oral tissues. Salivary secretion in the mouth can be impaired through dehydration, mouth breathing, the effects of medications and exposure to radiation.

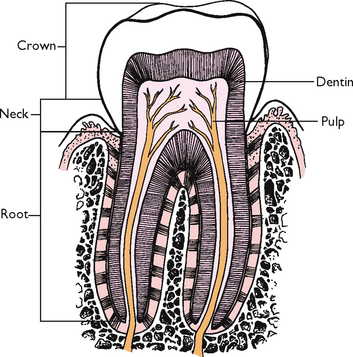

The teeth are the organs of chewing, or mastication. They are designed to cut, tear and grind food so it can be mixed with saliva and swallowed (Thibodeau and Patton, 2007). A normal tooth consists of the crown, neck and root (Figure 34-2). The periodontal membrane lies just below the gum margins, surrounds a tooth and holds it firmly in place. Healthy teeth appear white, smooth, shiny and properly aligned. Difficulty in chewing can develop when surrounding gum tissues become inflamed or infected, or when teeth are lost or become loosened. Regular oral hygiene is necessary to maintain the integrity of tooth surfaces and thus prevent dental caries and gingivitis (gum inflammation).

The hair

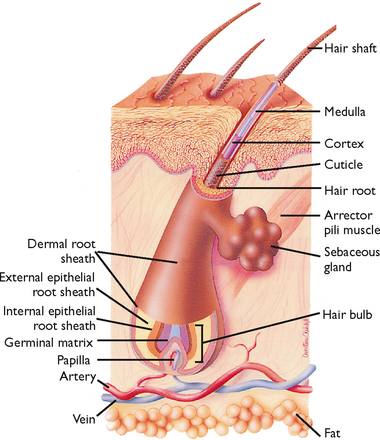

Hair growth, distribution and pattern can indicate a person’s general health status. Hormonal changes, emotional and physical stress, medications, ageing, infection and certain illnesses can affect hair characteristics. The hair shaft itself is inert and cannot be directly affected by physiological factors. However, changes in its colour or condition are caused by hormonal and nutrient deficiencies of the hair follicle. The hair follicle contains live cells and a rich capillary blood supply (Figure 34-3).

The eyes, ears and nose

When nurses provide hygiene care, the eyes, ears and nose require careful attention. Chapter 27 describes the structure and function of these organs. Cleaning of the sensitive sensory tissues should be done in a way that prevents injury and discomfort for the patient.

The perineal area

Provision of hygiene care to the perineal area requires tact and appreciation of the patient’s dignity, culture, emotions and physical safety as well as privacy. Maintaining a clean and dry perineal area helps to prevent breakdown and maceration of these sensitive tissues. Soiling with urine, faecal material and perspiration causes irritation and discomfort. Care of the perineal area of a patient with a retention catheter is performed more frequently than daily hygiene (see Skill 34-2, later in the chapter).

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

Perineal care can be undertaken by nurse assistants under the guidance of the registered nurse (Division 1).

EQUIPMENT

Additional supplies are needed when perineal care is given other than during a bath:

| STEPS | RATIONALE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretions that accumulate on surface of skin surrounding genitalia act as reservoirs for infection. Tissues traumatised by surgery or by presence of foreign object provide route for introduction of infectious organisms. | ||||

| Determines patient’s ability to perform self-care and determines level of assistance required from nurse. | ||||

|

3. Assess genitalia for signs of inflammation, skin breakdown or infection (see Chapter 29). |

Determines extent of perineal care required by patient. | |||

| Patients at risk of infection in perineal area may be unaware of importance of cleanliness. Reflects patient’s need for education. | ||||

| Helps minimise anxiety during procedure that is often embarrassing to nurse and patient. | ||||

| As used when administering a bed bath. | ||||

| Maintains patient’s privacy and ensures orderly procedure. | ||||

| Facilitates good body mechanics. Provides easy access to genitalia. | ||||

| Eliminates transmission of microorganisms. | ||||

|

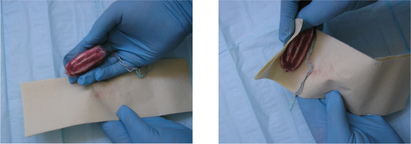

10. If faecal material is present, enclose in a fold of underpad or toilet paper, and remove with disposable wipes or toilet paper. Clean buttocks and anus, washing front to back (see illustration). Clean, rinse and dry area thoroughly. If needed, place an absorbent pad under patient’s buttocks. Remove and discard underpad and replace with clean one. |

Cleaning reduces transmission of microorganisms from anus to urethra or genitalia. | |||

| Protects skin from maceration and irritants in urine or stool | ||||

| a. Raise side rail. Fill washbasin with warm water. | ||||

| Equipment placed within nurse’s reach prevents accidental spills. | ||||

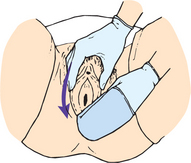

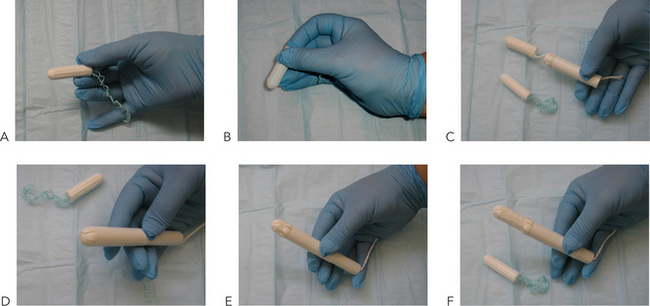

| A. Female perineal care | ||||

| Provides easy access to genitalia. | ||||

| Provides full exposure of female genitalia. Minimise degree of abduction in female if position causes pain because of arthritis or reduced joint mobility. | ||||

| Exposes perineal area for easy accessibility. | ||||

| Prevents unnecessary exposure of body parts and maintains patient’s warmth and comfort during procedure. | ||||

| Skinfolds may contain body secretions that harbour microorganisms. Wiping from perineum to rectum (front to back) reduces chance of transmitting faecal organisms to urinary meatus. | ||||

|

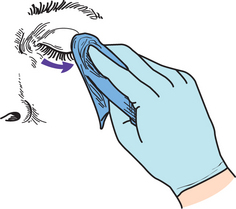

(7)Separate labia with non-dominant hand to expose urethral meatus and vaginal orifice. With dominant hand, wash downwards from pubic area towards rectum in one smooth stroke (see illustration). Use separate section of cloth for each stroke. Clean thoroughly around labia minora, clitoris and vaginal orifice. |

Cleaning method reduces transfer of microorganisms to urinary meatus. (For menstruating women or patients with indwelling urinary catheters, clean with cotton balls.) | |||

| Rinsing removes soap and microorganisms more effectively than wiping. Retained moisture harbours microorganisms | ||||

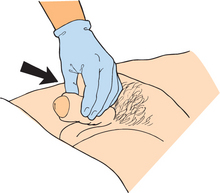

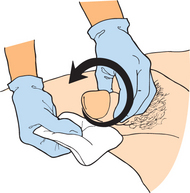

| B. Male perineal care | ||||

| Provides full exposure of male genitalia. | ||||

| Exposes perineal area for easy accessibility. Draping promotes comfort and minimises patient’s anxiety. | ||||

| Minimises transmission of microorganisms. Keeping patient draped until procedure begins minimises anxiety. Build-up of perineal secretions can soil surrounding skin surfaces. | ||||

| Direction of cleaning moves from area of least contamination to area of most contamination, preventing microorganisms from entering urethra. | ||||

| Tightening of foreskin around shaft of penis can cause local oedema and discomfort. | ||||

| Vigorous massage of penis can lead to erection, which can embarrass patient and nurse. Underlying surface of penis may have greater accumulation of secretions. Abduction of legs provides easier access to scrotal tissues. | ||||

| Moisture and body secretions on gloves can harbour microorganisms. | ||||

| Patient’s comfort helps to minimise stress of procedure. | ||||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | ||||

| Thick secretions may cover underlying skin lesions or areas of breakdown. Evaluation determines need for additional hygiene. | ||||

| Evaluates patient’s comfort level. | ||||

| Evaluates presence of infection. | ||||

| RECORDING AND REPORTING | HOME CARE CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

Nursing knowledge base

Nurses view patients’ healthcare needs from a holistic perspective. In the case of hygiene, it is important to consider the knowledge that is available regarding the numerous sociocultural, economic and developmental factors that influence hygiene practices. Application of this knowledge base allows the nurse to provide individualised hygiene care. As healthcare professionals, nurses must be conscious of their own hygiene, as they are considered a role model by the patient.

Social practices

Social groups influence hygiene preferences and practices, including the type of hygiene products used and the nature and frequency of personal care. During childhood, hygiene is influenced by family customs. This may include, for example, the frequency of bathing, the time of day bathing is performed and the type of oral hygiene practised. As children enter their adolescent years, personal hygiene may be influenced by peer-group behaviour. Young girls, for example, may become more interested in their personal appearance and begin to wear makeup. During the adult years, involvement with friends and work groups shape the expectations people have about their personal appearance. Older adults’ hygiene practices may change because of living conditions and available resources.

Personal preferences

Each person has individual desires and preferences about when to bathe, shave and perform hair care. People select different products according to personal preferences, needs and financial resources. These desires should help the nurse deliver individualised care. In addition, the nurse should help the patient develop new hygiene practices when indicated by an illness or condition.

Body image

A patient’s general appearance may reflect the importance hygiene holds for that person. Body image is a person’s subjective concept of their physical appearance (Chapter 23). These images can change frequently. Body image affects the way hygiene is maintained. If a patient is neatly groomed, the nurse considers the details of grooming when planning care and consults the patient before making decisions about how hygiene care is to be provided. Patients who appear unkempt or uninterested in hygiene may require education about its importance, and the nurse should assess the contributing factors. Culturally, maintaining cleanliness may not hold the same importance for some ethnic groups as it does for others. The nurse should be sensitive in considering that the patient’s economic status may influence the ability to regularly maintain hygiene, and never convey feelings of disapproval when caring for patients whose hygiene practices are different from the nurse’s.

When patients undergo surgery, illness or a change in functional status, body image can change dramatically. For this reason, the nurse needs to make an extra effort to promote the patient’s hygiene, comfort and appearance.

Socioeconomic status

A person’s economic resources influence the type and extent of hygiene practices used. The nurse determines whether patients can afford necessary supplies such as deodorant, shampoo, toothpaste and cosmetics. When basic care items are not affordable, the nurse tries to find alternatives. It is also important to learn whether use of these products is a part of the social habits practised by the patient’s social group. For example, not all patients may choose to use shampoos, deodorant or cosmetics. Access to a reliable water supply in some isolated communities alters hygiene practices.

When a nurse cares for a patient it is important to learn about the individual’s routine adherence to hygiene practices and whether the patient values those practices. Health promotion focuses on equity of access to resources while enabling people to increase control over the determinants of their health (Ridde, 2007). Thus, health promotion represents combining personal choice with social responsibility for health. When people have the added problem of a lack of socioeconomic resources, it becomes difficult to participate and take a responsible role in health-promotion activities such as basic hygiene.

Health beliefs and motivation

Knowledge about the importance of hygiene and its implications for wellbeing influences hygiene practices. However, knowledge alone is not enough. The patient also must be motivated to maintain self-care. Health motivation is part of an individual’s health beliefs or attitudes that influence health-related behaviours. The health belief model includes four variables that influence the individual’s motivation towards health promotion: (1) the likelihood of experiencing a harmful condition in response to behaviours; (2) perceived seriousness or threat of the condition; (3) perceived effectiveness of modifying behaviours to reduce a threat; and (4) negative aspects of the behaviour (Gillibrand and Stevenson, 2006). In regard to a patient’s hygiene practices, it is important for the nurse to know whether, for example, a patient perceives being at risk of dental disease, thinks dental disease to be serious, thinks brushing and flossing to be effective in reducing risk and believes there are any negative implications from following recommended hygiene practices. When patients recognise there is a risk and reasonable action can be taken with no negative consequence, they will be more receptive to the nurse’s counselling and teaching efforts.

Cultural variables

A patient’s cultural beliefs and personal values influence hygiene care. People from diverse cultural backgrounds follow different self-care practices (Chapter 17). In many cultural groups in Australia, it is common to bathe or shower daily, whereas in some other cultural groups it is customary to bathe completely only once a week (see Working with diversity).

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY Focus on cultural care

For Hindus, personal hygiene is an important part of each day. A daily bath is part of their religious duty. Bathing needs to take place at correct times and in the correct way. For example, bathing after a meal is believed by some Hindus to be injurious. Similarly, a bath that is too hot may injure the eyes. Hot water may be added to cold water, but cold water is not to be added to hot water when one is preparing a bath. Once a bath is completed, the body is dried thoroughly with a towel.

Adapted from Giger JN, Davidhizar RE 2008 Transcultural nursing: assessment and intervention, ed 5. St Louis, Mosby.

Physical condition

Patients with certain types of physical limitations or disabilities often lack the physical energy and dexterity to perform hygiene care. A patient in traction or a cast or who has an intravenous line or other device connected to the body will need assistance with hygiene. Illnesses that cause pain may limit the dexterity and range of motion needed to perform certain measures. Patients still under the effects of sedation will not have the mental clarity or coordination to perform self-care. Chronic illnesses, such as cardiac disease, cancer, neurological disorders and certain mental health conditions, may exhaust or incapacitate a patient. A weakened grasp resulting from arthritis, cerebrovascular accident or muscular disorders can prevent a patient from using a toothbrush, washcloth or comb.

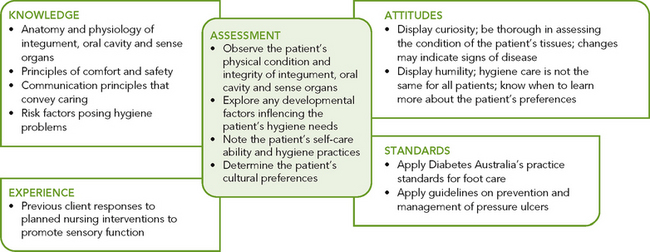

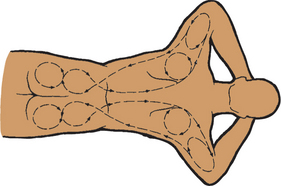

Critical thinking synthesis

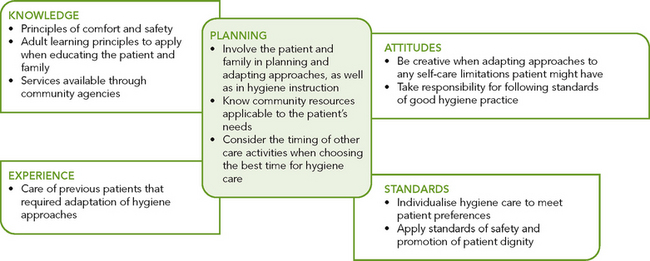

Because hygiene care is so important for a patient to feel comfortable, refreshed and renewed, the nurse avoids making hygiene care a simple routine. Instead, the nurse synthesises knowledge, previous experience with patients, critical-thinking attitudes and standards in judging the most effective way to provide effective hygiene. A middle-aged woman with abdominal pain who had major surgery only 24 hours previously will require a different approach to hygiene from an older adult who has left-sided paralysis. During the nurse’s assessment (Figure 34-4), all critical-thinking elements are considered in understanding the patient’s needs and in making appropriate nursing diagnoses. In addition, while hygiene is being administered, the nurse makes important observations (e.g. condition of patient’s skin, ability of patient to move and initiate activities) and uses them when making clinical judgments about the patient’s overall nursing care.

NURSING PROCESS

ASSESSMENT

Nursing assessment is an ongoing process. The nurse may not have assessed all body regions before administering hygiene; however, the nurse routinely assesses the patient’s condition whenever care is given. For example, during oral care the condition of the teeth and mucosa can be inspected. When a patient has had an ongoing problem (e.g. dry skin, inflamed oral mucosa), then it is important to conduct an assessment before care is administered because variations in technique may be necessary. Hygiene care allows the nurse to make assessment findings for a variety of healthcare problems and thus helps set healthcare priorities.

Physical examination

While assisting a patient with personal hygiene, the nurse assesses the integument, oral cavity structures, and the eyes, ears and nose (Chapter 27). Using the skills of inspection and palpation, the nurse looks for alterations in the integrity and function of tissues. The assessment also reveals the type and extent of hygiene care required. Special attention is given to the characteristics most influenced by hygiene measures. Is the skin dry from too much bathing? Are there calluses of the feet that may benefit from soaking and moisturising lotion? Is there a coating of the tongue that requires frequent brushing and hydration? Over time, the nurse’s assessment provides the baseline for determining whether hygiene measures maintain or improve the patient’s condition.

SKIN

While inspecting the skin, the nurse thoroughly examines its colour, texture, thickness, turgor, temperature and hydration. The skin should be smooth, warm and supple with good turgor. The nurse pays special attention to the presence and condition of any lesions (see Chapter 27). Certain common skin problems affect how hygiene is administered (Table 34-2). Special care is also given to assess less-obvious or difficult-to-reach skin surfaces, such as under the female’s breasts, under the male’s scrotum or around the female’s perineal tissues (see Chapter 38). The nurse who observes skin problems should explain proper skin care and specific hygiene techniques to the patient.

TABLE 34-2 COMMON SKIN PROBLEMS

Certain conditions place patients at risk of impaired skin integrity (Box 34-1). Nurses must be particularly alert when assessing patients with reduced sensation, vascular insufficiency and immobility. Be sure to assess extremities and help turn a patient so that a skin surface can be fully viewed. The development of pressure ulcers is a common complication that can extend hospital stays and threaten the wellbeing of the extended-care patient (Bluestein and Javaheri, 2008).

BOX 34-1RISK FACTORS FOR SKIN IMPAIRMENT

IMMOBILISATION

When restricted from moving freely, dependent body parts are exposed to pressure, reducing circulation to affected body parts. The nurse should know which patients need help to turn and change positions.

REDUCED SENSATION

Patients with paralysis, circulatory insufficiency or local nerve damage are unable to sense an injury to the skin. During a bath, assess the status of sensory nerve function by checking for pain, tactile sensation and temperature sensation.

NUTRITION AND HYDRATION ALTERATIONS

Patients with limited kilojoule and protein intake can develop thinner, less-elastic skin, with loss of subcutaneous tissue. This can result in impaired or delayed wound healing.

SECRETIONS AND EXCRETIONS ON THE SKIN

Moisture on the skin’s surface serves as a medium for bacterial growth and can cause irritation, soften epidermal cells and lead to skin maceration. Presence of perspiration, urine, watery faecal material and wound drainage on the skin can result in breakdown and infection.

VASCULAR INSUFFICIENCY

Inadequate arterial supply to tissues and impaired venous return decrease circulation to the extremities. Inadequate blood flow can cause ischaemia and breakdown. Risk of infection also exists because delivery of nutrients, oxygen and white blood cells to injured tissues is inadequate.

FEET AND NAILS

Assessment of the feet involves a thorough examination of all skin surfaces, including areas between the toes and over the soles of the feet. The heels, soles and sides of the feet are prone to irritation from poorly fitting shoes. In addition, the nurse inspects the shape and size of toes and the shape of the foot. The toes are normally straight and flat. The feet should be in straight alignment with the ankle and tibia. Inspection of the feet for lesions includes noting areas of dryness, inflammation or cracking.

The nurse assesses the patient’s gait. Painful foot disorders or decreased sensation can cause limping or an unnatural gait. The nurse asks whether the patient has foot discomfort and determines factors that aggravate the pain. Foot problems may result from bone or muscular alterations rather than skin disorders.

Patients with peripheral vascular disease, such as those with diabetes mellitus, should be assessed for the adequacy of circulation to the feet (Chapter 27). Palpation of the dorsal pedis and posterior tibial pulses indicates whether adequate blood flow is reaching peripheral tissues. Oedema and changes in skin colour, texture and temperature can indicate whether the patient requires special hygiene care.

People with diabetes mellitus should also be checked for neuropathy, degeneration of the peripheral nerves characterised by a loss of sensation. The nurse assesses the patient’s sensation to light touch and temperature.

The nurse inspects the condition of the fingernails and toenails, looking for lesions, dryness, inflammation or cracking (Table 34-3). The nail is surrounded by a cuticle, which slowly grows over the nail and must be regularly pushed back. The skin around the nail beds and cuticles should be smooth and without inflammation. The nurse should ask women whether they frequently polish their nails and use polish remover, because chemicals in these products can cause excessive nail dryness. Disease can change the shape and curvature of the nails (see Chapter 27). Inflammatory lesions and fungus of the nail bed can cause thickened, horny nails, which can separate from the nail bed. Reduced circulation to the feet can cause thickening and brittleness of the toenails.

TABLE 34-3 COMMON FOOT AND NAIL PROBLEMS

| CHARACTERISTICS | IMPLICATIONS | INTERVENTIONS |

|---|---|---|

| CALLUS | ||

| Condition may cause discomfort when wearing tight shoes | ||

| CORNS | ||

| PLANTAR WARTS | ||

| Fungating lesion appears on sole of foot and is caused by papillomavirus | Warts may be contagious. They painful and make walking difficultare | Treatment ordered by doctor may include applications of salicylic acid, electrodesiccation (burning with electrical spark) or freezing with solid carbon dioxide |

| ATHLETE’S FOOT (TINEA PEDIS) | ||

| Athlete’s foot can spread to other body parts, especially hands. It is contagious and frequently recurs | ||

| INGROWN NAILS | ||

| Toenail or fingernail grows inwards into soft tissue around nail; often results from improper nail trimming | Ingrown nails can cause localised pain when pressure is applied | |

| RAM’S HORN NAILS | ||

| Ram’s horn nails are usually long, curved nails | Attempt by nurse to cut nails may result in damage to nail bed with risk of infection | Nurse refers patient to podiatrist |

| PARONYCHIA | ||

| Inflammation of tissue surrounding nail occurs after hangnail or other jury; occurs in people who frequently have their hands in water and is common in diabetic patients | Area can become infected | |

| FOOT ODOURS | ||

| Foot odours are the result of excess perspiration promoting microorganism growth | Condition may cause discomfort because of excess perspiration and embarrassment because of odour | Frequent washing, use of foot deodorants and powders and wearing clean footwear prevent or reduce problem |

ORAL CAVITY

Chapter 27 describes in detail the nurse’s assessment of the patient’s lips, teeth, buccal mucosa, gums, palate and tongue. The nurse inspects all areas carefully for colour, hydration, texture and lesions. People who do not follow regular oral hygiene practices may have receding gum tissue, inflamed gums, a coated tongue, discoloured teeth (particularly along gum margins), dental caries (chalky white discolouration of tooth or presence of brown or black discolouration), missing teeth and halitosis (bad breath). Note that halitosis can also arise from conditions in other parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Localised pain is a common symptom of a gum disease and certain tooth disorders. An infection of the mouth may involve organisms such as Treponema pallidum, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and herpesvirus hominis.

It is especially important to examine the oral cavity of patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy. Both treatments can cause serious changes in salivary gland function and mucosal integrity. The nurse’s assessment serves as a basis for preventive care for patients as they undergo treatment (Harris and others, 2008).

HAIR

Before performing hair care, the nurse assesses the condition of the hair and scalp. Normally the hair is clean, shiny and untangled, and the scalp is clear of lesions. The hair of dark-skinned patients is usually thicker, drier and curlier than that of lighter-skinned patients. Table 34-4 summarises hair and scalp problems that the nurse may identify. In the community-health and home-care settings, it is particularly important to inspect the hair for lice so that appropriate hygiene treatment can be provided. If Pediculosis capitis (head lice) is suspected, the nurse guards against self-infestations by handwashing and using gloves or tongue blades to inspect the patient’s hair. The loss of hair (alopecia) can result from the effects of chemotherapy medications, hormonal changes or unsuitable hair care practices. Patients at risk of scalp problems are those who have experienced head trauma and those who practise poor hygiene.

TABLE 34-4 HAIR AND SCALP PROBLEMS

| CHARACTERISTICS | IMPLICATIONS | INTERVENTIONS |

|---|---|---|

| DANDRUFF | ||

| Scaling of scalp is accompanied by itching In severe cases, dandruff is found on eyebrows | Shampoo regularly with medicated shampoo. In severe cases, obtain doctor’s advice | |

| TICKS | ||

| Small, grey-brown parasites burrow into skin and suck blood | Ticks transmit several diseases to people, including typhoid, Lyme disease, spotted fever and tick paralysis. Some species of tick can cause paralysis | |

| LICE (PEDICULOSIS) | ||

| Lice may spread through bed linen, clothing or furniture, or between persons via sexual contact | ||

| HAIR LOSS (ALOPECIA) | ||

| Patches of uneven hair growth and loss alter person’s appearance | Stop hair-care practices that damage hair |

EYES, EARS AND NOSE

The nurse’s examination assesses the condition and function of the eyes, ears and nose (see Chapter 27). Normally the eyes are free of infection and irritation. The sclerae are visible anteriorly as the white portion of the eye. The conjunctivae (linings of the eyelids) are clear, pink and without inflammation. The eyelid margins are in close approximation with the eyeball, and the lashes are turned outwards. The lid margins are without inflammation, drainage or lesions. The eyebrows should be symmetrical.

Another important aspect of an eye examination is to determine whether the patient wears contact lenses. This is especially significant for patients who enter hospitals or other agencies unresponsive or in a confused state. An undetected lens can cause severe corneal injury when left in place too long.

Assessment of the external ear structures includes inspection of the auricle, external ear canal and tympanic membrane. While performing hygiene measures, the nurse notes the presence of accumulated cerumen or drainage in the ear canal, local inflammation or pain.

The nurse inspects the nares for signs of inflammation, discharge, lesions, oedema and deformity. The nasal mucosa is normally pink and clear and has little or no discharge. A clear, watery discharge may be the result of allergies. If the patient has any form of tubing exiting the nose (e.g. nasogastric), the nurse should look at the nares’ surfaces that come in contact with the tubing for tissue sloughing, localised tenderness, inflammation and bleeding.

Developmental changes

The normal process of ageing influences the condition of body tissues and structures and thus the manner in which hygiene measures are performed.

SKIN

The neonate’s skin is relatively immature at birth. The epidermis and dermis are loosely bound together and the skin is very thin. Friction against the skin layers can cause bruising. The nurse must handle the neonate carefully during bathing. Any break in the skin can easily lead to infection.

A toddler’s skin layers are more tightly bound together than the neonate’s, so the child has a greater resistance to infection and skin irritation. However, because of the child’s more-active play and the absence of established hygiene habits, greater attention is needed from parents and caregivers to provide thorough hygiene and to begin teaching good hygiene habits.

During adolescence the growth and maturation of the integument increases. In girls, oestrogen secretion causes the skin to become soft, smooth and thicker, with increased vascularity. In boys, male hormones produce an increased thickness of the skin with some darkening in colour. Sebaceous glands become more active, predisposing adolescents to acne. Eccrine and apocrine sweat glands become fully functional during puberty. Adolescents usually begin to use antiperspirants. More-frequent bathing and shampooing also become necessary to reduce body odours and eliminate oily hair. Sweating is usually more pronounced in boys in temperate climates.

The condition of the adult’s skin depends on hygiene practices and exposure to environmental irritants. Normally the skin is elastic, well hydrated, firm and smooth. When an adult bathes frequently or is exposed to an environment with low humidity, the skin can become very dry and flaky. With age, the skin loses its resilience and moisture, and sebaceous and sweat glands become less active. The epithelium thins and elastic collagen fibres shrink, making the skin fragile and subject to bruising and breaking (see Working with diversity). These changes warrant caution when turning and repositioning older adults. Typically, the older person’s skin is dry and wrinkled. Daily bathing as well as bathing with water that is too hot or soap that is harsh may cause the skin to become excessively dry.

FEET AND NAILS

Changes in the infant’s feet occur during infancy and early childhood as locomotion and weightbearing progress. At birth the feet are flat because the arches are protected by fat pads on the soles. As the bones in the arches develop, the pads disappear and the feet begin to assume a mature shape (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2007).

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON OLDER ADULTS

With normal ageing the skin decreases in thickness and elasticity. The epidermal cells of the older adult contain less moisture and the skin often has a dry and wrinkled appearance. The connections between the dermis and epidermis are reduced and therefore increase the possibility for skin tears. For many older adults the slightest impact or friction against their fragile skin will cause a skin tear. The nurse plays a critical role in maintaining skin integrity of the older adult. Extra care must be taken to protect fragile skin when assisting elders to move and re-position in the bed and to complete hygiene measures, as well as in other activities of daily living.

From Tabloski P 2006 Gerontological nursing. Upper Saddle River, NJ, Pearson.

The main reason for shoes is protection. Shoes should retain their fit, be made of durable material with a smooth interior and few construction seams to irritate the skin and be soft and flexible, especially in the toes. During weightbearing there should be at least the space of half the width of the thumbnail, or 1.25 cm, between the end of the longest toe and the shoe (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2007). Frequent changes in shoe size are needed to accommodate the infant’s rapidly growing feet. Curled toes when shoes are removed and redness and irritation of the skin on the bottom of the toes indicate the need for a larger shoe size. As children grow, it is important that they continue to be fitted with a proper shoe size. The more active a child becomes, the greater the need for sturdy shoes that protect the feet from injury.

During standing, the foot provides body support and absorbs shock. With ageing, the feet begin to show signs of wear and tear. This may occur earlier if a person has not worn comfortable, supportive footwear. The cushioning layer of fat on the soles of the feet becomes thin. Years of walking cause the metatarsal bones to spread and ligaments to stretch, which results in wider feet (Kwan and others, 2010).

Chronic foot problems are a common part of ageing. Older adults often have dry feet because of a decrease in sebaceous gland secretion, dehydration of epidermal cells and poor condition of footwear. Fissures that result in itching often develop. The feet of older adults often develop abnormalities over time, which can become disabling if not cared for appropriately (Touhy and Jett, 2011). Painful feet can be the result of congenital deformities, weak structure, injuries, and diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis is generally the cause of changes in the feet after age 55 years. Additional common problems of the feet include hammer and claw toes (flexion contractures); bunions, corns and calluses; heel spurs and gout (Touhy and Jett, 2011). Fungal infections occur under toenails, causing yellow streaks or total discolouration. The nails can also become opaque, scaly and hypertrophied. If foot or nail problems stay unresolved, an older adult can easily become disabled. The nurse applies knowledge of typical changes in the feet and nails when anticipating the type of hygiene a patient will require.

THE MOUTH

At approximately 6–8 months of age, infants begin teething (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2007). The eruption of the deciduous (primary) teeth usually begins with the lower central incisors, followed closely by the upper central incisors (Table 34-5). When the crown of a tooth breaks through the periodontal membrane, some discomfort can be experienced. Drooling, increased finger-sucking or biting on hard objects may be the only signs of discomfort. Some children can become very irritable and have difficulty sleeping and eating. Teething continues to occur until the final molars erupt, at around 27–29 months of age.

TABLE 34-5 PHYSIOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE MOUTH

Adapted from Hockenberry M, Wilson D 2009 Wong’s Essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby; Jarvis C 2008 Physical examination and health assessment, ed 5, St Louis, Saunders.

The first permanent (secondary) teeth erupt between 5 and 8 years of age (Thibodeau and Patton, 2007). Before their appearance they have been developing in the jaw beneath the primary teeth. Meanwhile, the roots of primary teeth are gradually absorbed, so that at the time a deciduous tooth is shed, only the crown remains. The pattern of shedding primary teeth and the eruption of secondary teeth varies widely among children. Many of the difficulties created by crowding of teeth become apparent. Since it is during the school-age years that the permanent teeth erupt, good dental hygiene and regular attention to dental caries are a part of health-promotion practices. Children of this age tend to be lax about oral hygiene and are not motivated by improved appearance and odour, as they will be during adolescence. In addition, children prefer sugary sweets and soft drinks for snacks. Parental support is critical for health maintenance.

From adolescence, when all of the permanent teeth are in place, through middle adulthood, the teeth and gums remain healthy if a person follows good eating patterns and good dental care. Avoidance of fermentable carbohydrates and sticky sweets are central to keeping the teeth free of caries. Regular brushing and flossing helps to prevent caries and periodontal disease (Huskinson and Lloyd, 2009).

As a person grows older there are numerous factors that can result in poor oral care (see Research highlight). These include age-related changes of the mouth, chronic disease such as diabetes, physical disabilities involving hand grasp or strength, lack of attention to oral care, and prescribed medications that have oral side effects. Effects of inadequate care include dental caries and loss of teeth; periodontal disease; systemic infection; and long-term effects on self-esteem, the ability to eat and the maintenance of relationships. Many older people are edentulous (without teeth) and wear complete or partial dentures. It is important for the nurse to learn whether older adults wear dentures and the condition of underlying supportive gum tissue.

HAIR

Throughout life, changes in the growth, distribution and condition of the hair influence the hygiene a person requires (Table 34-6). As males reach adolescence, shaving becomes a part of routine grooming. Young girls who reach puberty may begin to shave or wax their legs and axillae. With ageing, as scalp hair becomes thinner and drier, shampooing is usually done less frequently.

TABLE 34-6 PHYSIOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF HAIR GROWTH

| AGE | CONDITION OF HAIR |

|---|---|

| Infancy | |

| Childhood | |

| Middle childhood to puberty | Androgenic hormones cause increase in thickening and darkening of scalp hair, growth of hair in axillae and pubic areas in both sexes and growth of facial hair in boys |

| Adolescence | |

| Adulthood | Men with genetic tendency develop baldness |

| Older adulthood |

EYES, EARS AND NOSE

Chapter 26 covers the changes in hearing, vision and smell as a result of growth and development.

Self-care ability

Research focus

Poor oral health in adult life has been linked to socioeconomic status in childhood. Studies have also been conducted linking oral disease to other conditions in adult life. This study reports the lessons learned from an interprofessional education initiative where two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care.

Research abstract

Nursing and dental hygiene students at George Brown College were brought together in an initiative to learn from each other about the overlapping roles they share in oral-health and blood-pressure monitoring. The World Health Organization (WHO) has long advocated for ‘multiprofessional’ education among undergraduate healthcare students to build ‘the skills necessary for solving the priority health problems of individuals and communities that are known to be particularly amenable to team-work’.

There is evidence of a connection between oral health and systemic health, and the increased need for proper daily oral health assessment and care for populations within acute and long-term care. At present, members of the nursing profession whose scope of practice includes providing oral assessment and daily oral care are the frontline caregivers for these populations. The increase in high blood pressure within the general population is also a priority health problem. Dental hygienists are frontline healthcare professionals in oral assessment and oral care education whose scope of practice includes taking blood pressure and pulse.

The results of the Canadian Health Measures Survey show that approximately 70% of the population sees an oral health practitioner on an annual basis. Dental hygienists are in an ideal position to monitor and screen for high blood pressure.

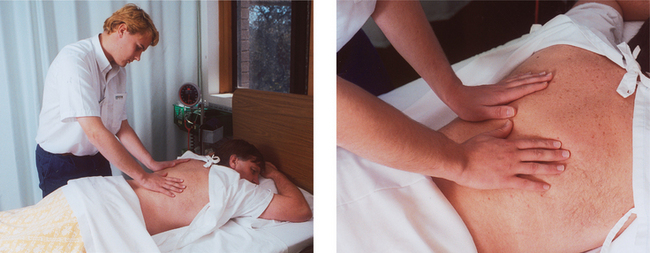

Patients’ self-care abilities determine whether assistance is needed in managing activities of daily living (ADLs), including routine hygiene. The nurse assesses a patient’s physical and cognitive ability to perform basic hygiene measures. The nurse’s assessment must include measurement of a patient’s muscle strength, flexibility and dexterity, balance, coordination, and activity tolerance necessary in performing activities such as bathing, brushing teeth and bending over to inspect the feet (Figure 34-5). For example, observing a patient’s ability to completely brush the front surfaces of all lower front teeth in 30 seconds and noting the patient’s ability to pick up and use the brush is a way to assess ability to brush the teeth (Miegel and Watchel, 2009). The degree of assistance needed by a patient during hygiene care may also depend on vision, the ability to sit without support, attached equipment, hand grasp and the range of motion in the patient’s extremities. Painful conditions of the upper extremities pose special problems. The nurse can assess self-care ability by asking patients to perform activities such as brushing the teeth or combing the hair. Observe the patient carefully and note not only whether the activity is performed correctly, but also whether the patient is thorough and can complete the task without undue fatigue.

FIGURE 34-5 The nurse observes patient brushing teeth. During such observations the nurse can determine how much help the patient may need.

When patients have self-care limitations, part of the nurse’s assessment is determining whether family or friends are available to assist. In addition, the nurse assesses the home environment and its influence on the patient’s hygiene practices. Are there barriers in the home that may affect the patient’s self-care abilities? Taps that are too tight to easily adjust, baths with high sides and a bathroom too small to fit a chair in front of a sink are a few examples. Burns to small children and the elderly often occur because the tap-water temperature is set too high. Ideally, the temperature should be no higher than 49°C.

Hygiene practices

Each patient has a preferred routine for how to perform hygiene. The nurse should not assume that all patients typically bathe and groom early each morning after getting out of bed. Some patients may bathe on a weekly basis only. In addition, patients vary in the type of hygiene products used and in which hygiene measures they practise. In assessing a patient’s practices, the nurse may ask a patient to describe what is typically done to care for the skin, teeth, hair and feet. The nurse also observes the patient’s appearance. For example, dull, tangled and dirty hair indicates improper care. Unkempt hair may result from lack of interest, depression, lack of grooming resources, a physical inability to care for the hair, or the patient’s preference. When a patient’s appearance suggests poor hygiene, the nurse must be sensitive in learning what the causes are.

Assessment of hygiene practices reveals the patient’s preferences for grooming. For example, a patient may choose to groom the hair in a certain style or choose to trim nails in a certain way. When a patient has a physical disability, special precautions may be needed to perform grooming without injury. Asking the patient to help or teach the nurse how to perform preferred grooming practices gives the patient a greater sense of independence and helps the nurse avoid causing the patient any discomfort or injury.

Because of a significant increase in the numbers of older adults and minorities, dental practice is facing new challenges. Immigrant communities may have high levels of untreated dental caries or gingivitis. This pattern suggests deficient hygiene practices, limited access to dental care resources or improper hygiene techniques. Helpful questions to use in assessing dental hygiene practices include the following:

• How often does the patient brush the teeth?

• What type of toothbrush and toothpaste are used?

• Does the patient have dentures, partials or bridges? When and how are they cleaned?

• Does the patient use mouthwash, which can cause excess mucosal drying?

• Does the patient floss? If so, how often?

• When was the patient’s last dental visit? How often are visits to a dentist made? What were the most recent results?

Toothbrushes should be discarded every 3 months or after an upper respiratory infection or pharyngitis. This prevents infection or reinfection from microbial colonisation on the toothbrush (Harris and others, 2008)

Cultural factors

A patient’s cultural background is an influential factor when determining hygiene needs. Culture plays a role not only in hygiene practices and preferences, but also in sensitivity to personal space (see Chapter 12). For example, some Chinese people may view tasks associated with closeness and touch as being offensive or impolite (Giger and Davidhizar, 2008). The nurse should ask patients what would make them feel most comfortable during a bath. Perhaps a patient would prefer only a partial instead of a full bath from the nurse, with a family member completing the bathing of more-private body parts. The patient may also defer part of the hygiene. If, in the nurse’s judgment, hygiene is critical to prevent or worsen problems, such as skin breakdown, the nurse must take the time to understand the patient’s concerns and then offer an explanation that will help the patient accept the nurse’s intervention.

Patients at risk of hygiene problems

Some patients present risks that require more attentive and rigorous hygiene care (Table 34-7). These risks result from side effects of medications, a lack of knowledge, an inability to perform hygiene or a physical condition that potentially injures the skin, integument or other structures. An immobilised patient who has a fever, for example, will require more-frequent bathing to minimise sweat on the skin, and more frequent turning and positioning to reduce the chance of skin breakdown. The nurse anticipates whether a patient is predisposed to such risks and follows through with a complete assessment. For example, if a patient is receiving chemotherapy there is the risk of the medication destroying normal flora in the mouth, allowing for the overgrowth of opportunistic microorganisms, e.g. fungal organisms such as Candida albicans; therefore, the oral examination should be more thorough and detailed, with the nurse examining all surfaces of the tongue and mucosa. If a patient is diaphoretic, the nurse will give special attention to body areas such as a woman’s breasts and perineal area to check where moisture may collect and irritate skin surfaces. The nurse anticipates problems created by these risks so as to provide appropriate preventive care. The nurse’s assessment will include a review of the patient’s medical and surgical history, medications and the specific risk factors the patient is likely to have.

TABLE 34-7 RISK FACTORS FOR HYGIENE PROBLEMS

| PROBLEM | HYGIENE IMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|

| ORAL PROBLEMS | |

| People who are unable to use upper extremities due to paralysis, weakness or restriction (e.g. cast or dressing) | Person lacks upper-extremity strength or dexterity needed to brush teeth |

| Dehydration, inability to take fluids or food by mouth (NBM) | Causes excess drying and fragility of mucosa; increases accumulation of secretions on tongue and gums |

| Presence of nasogastric or oxygen tubes; mouth breathers | Causes drying of mucosa |

| Chemotherapeutic drugs | Drugs kill rapidly multiplying cells, including normal cells lining oral cavity; ulcers and inflammation can develop |

| Lozenges, cough drops, antacids and chewable vitamins over-the-counter (OTC) | Medications contain large amounts of sugar; repeated use increases sugar or acid content in mouth |

| Radiation therapy to head and neck | Reduces salivary flow and lowers pH of saliva; can lead to stomatitis and tooth decay. |

| Oral surgery, trauma to mouth, placement of oral airway | Cause trauma to oral cavity with swelling, ulcerations, inflammation and bleeding |

| Immunosuppression; alters blood clotting | Predisposes to inflammation and bleeding gums |

| Diabetes mellitus | Prone to dryness of mouth, gingivitis, periodontal disease and loss of teeth |

| SKIN PROBLEMS | |

| Immobilisation | Dependent body parts are exposed to pressure from underlying surfaces. The inability to turn or change position increases risk of pressure ulcers |

| Reduced sensation due to stroke, spinal cord injury, diabetes, local nerve damage | Normal transmission of nerve impulses not received when excessive heat or cold, pressure, friction or chemical irritants are applied to skin |

| Limited protein or kilojoule intake and reduced hydration (e.g. fever, burns, gastrointestinal alterations, poorly fitting dentures) | |

| Excessive secretions or excretions on the skin from perspiration, urine, watery faecal material and wound drainage | Moisture is a medium for bacterial growth and can cause local skin irritation, softening of epidermal cells and skin maceration |

| Presence of external devices (e.g. casts, restraint, bandage, dressing) | Device can exert pressure or friction on skin’s surface |

| Vascular insufficiency | Arterial blood supply to tissues is inadequate, or venous return is impaired, causing decreased circulation to extremities. Tissue ischaemia and breakdown may occur; risk of infection is high |

| FOOT PROBLEMS | |

| Person unable to bend over or has reduced visual acuity | Person is unable to fully see entire surface of each foot, impairing ability to adequately assess condition of skin and nails |

| EYE CARE PROBLEMS | |

| Reduced dexterity and hand coordination | Physical limitations create inability to safely insert or remove contact lens |

Special considerations in hygiene assessment

Depending on the type of hygiene a nurse plans to provide, there are focused assessments that are important to conduct.

Before giving foot care, the nurse assesses the type of footwear worn by a patient. Children or young adults who often don’t wear socks may have excess perspiration that promotes fungal growth. Tight or poorly fitting shoes, socks, garters or knee-high stockings may cause skin irritation and interfere with circulation to the feet. The nurse also assesses whether patients wear clean footwear daily, because repeated use of soiled footwear can lead to infection. If the patient has diabetes mellitus or other peripheral vascular disease, it is extremely important that correct footwear be worn. Extra-wide and extra-deep shoes will accommodate bunions or hammer toes. Cushioned inner soles help redistribute pressure on the metatarsal head.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Mrs Viera is 62 years old and is being seen in the internal medicine clinic during her follow-up appointment for management of her diabetes mellitus. During the nurse’s conversation with Mrs Viera, the patient says, ‘You know, last week I found a sore on my left foot; I didn’t even know it was there.’ What type of assessment should the nurse conduct for Mrs Viera, and what might be the implications of her findings?

A patient’s eating patterns are important to assess prior to oral care. The presence of any problems may help the nurse to locate abnormalities. The nurse asks a patient if any problems are noted with chewing, denture fit or swallowing. A patient may have changed the type of food in the diet as a result of chewing difficulties. The presence of an ulcer or irritation may impair chewing and cause a patient to avoid eating. This is common in an older adult with poorly fitting dentures.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005), people living in rural or remote areas have a greater incidence of poor dental health than city people, and have less access to dental care. Indigenous Australians have twice the level of edentulism or complete tooth loss compared with other Australians. The nurse can play a very important role, particularly when caring for patients in rural settings, poor patients and older adults, in being able to screen for abnormalities such as dental decay and referring dental problems to a dental professional.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Alison Jakes is 14 years old and visiting the clinic for a vaccination. She mentions to the clinic nurse that she has a toothache. What assessment would be required for Alison? What recommendations might the clinic nurse make about dental care?

If patients wear glasses, contact lenses, artificial eyes or hearing aids, the nurse assesses the patient’s knowledge of methods used to care for the aids, and the presence of any problems. Box 34-2 outlines factors to assess in patients who use sensory aids. Findings have implications for patient education and nursing care.

BOX 34-2 ASSESSING PATIENT’S USE OF SENSORY AIDS

CONTACT LENSES

• Frequency and duration of time lenses are worn (including sleep time)

• Presence of symptoms (e.g. burning, excessive eye-watering, redness, irritation, swelling, sensitivity to light)

• Techniques used to clean, store, insert and remove lenses

• Use of eye drops or ointments

• Use of emergency identification bracelet or card that warns others to remove patient’s lenses in case of emergency

Patient expectations

As is the case in any nursing assessment, it is important to know what a patient expects from nursing care. In regard to hygiene care, the patient may simply expect to have hygiene preferences and practices applied in the healthcare setting. The nurse can learn a patient’s expectations by asking questions such as ‘To make you most comfortable and feel at home, how can I best perform your bath and personal care?’ or ‘How can we help you to care for your teeth, nails and hair, now that you are back home?’

Learning a patient’s expectations and applying them in practice is important in establishing a caring relationship. Truly individualising hygiene care shows the nurse’s respect for the patient’s needs. As the nurse learns what the patient expects, this information can be incorporated into goal development (see Planning, below).

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

The nurse’s assessment will reveal the condition of the skin, oral cavity and other tissues, as well as the patient’s need for and ability to meet personal hygiene needs. The nurse reviews all data gathered, considers previous patients cared for, reviews knowledge pertaining to pre-existing conditions and then looks for clusters of data suggesting a problem trend. For example, an older adult with degenerative arthritis presents to the home health nurse with pain in the joints, weakness, mobility limitations in the dominant hand and a generally unkempt appearance. Closer review of assessment data reveals defining characteristics of an inability to wash body parts and difficulty turning and regulating a tap. The nursing diagnosis of bathing/hygiene self-care deficit is supported and becomes part of the nurse’s plan of care. The nurse’s accurate selection of nursing diagnoses requires critical thinking to identify actual or potential health problems (Box 34-3). Assessment activities must be thorough in revealing all appropriate defining characteristics so that an accurate diagnosis can be made.

BOX 34-3 SAMPLE NURSING DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| HYGIENE CARE | ||

|---|---|---|

| ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS | NURSING DIAGNOSIS |

| Inspect condition of patient’s perianal and perineal tissues. | Skin is becoming reddened over perianal area. | Risk of impaired skin integrity related to chemical irritation. |

| Observe character of patient’s loose stools. | Stools are diarrhoeal in nature, occurring 5-6 times daily. | |

| Note frequency of loose stools. | ||

| Observe patient attempt to bath self either in bed or at bathroom sink. (Note: be sure positioning does not restrict potential movement.) | Patient is unable to wash body or body parts. | Self-care deficit, bathing/hygiene related to upper extremity weakness. |

| Observe patient adjust flow of water. | Patient is unable to regulate water flow. | |

| Assess patient’s upper extremity strength, range of motion and coordination. | Patient has reduced upper extremity movement and strength. | |

Whether a patient has an actual alteration (e.g. impaired tissue integrity) or is at risk (e.g. risk of infection) determines the focus of nursing interventions. The patient with an actual alteration will require extensive hygiene care, often more thorough than routine hygiene might involve. For example, if the patient has skin breakdown, the nurse must initiate care more frequently to keep existing skin surfaces clean and dry and to eliminate factors such as moisture or drainage that can worsen the condition of the skin. The nurse would also provide care to promote healing of injured skin surfaces (see Chapter 30). If the patient is at risk of a problem, the nurse will institute preventive measures. In the case of risk of impaired oral mucous membranes, the nurse will keep the mucosa well hydrated, minimise foods irritating to tissues and provide cleaning that soothes and reduces tissue inflammation.

The identification of related factors guides the nurse in the selection of nursing interventions. A diagnosis of altered oral mucous membrane related to malnutrition and one of altered oral mucous membrane related to chemical trauma require very different interventions. When malnutrition is a causal factor, the nurse will obviously confer with a dietitian for appropriate dietary supplements and incorporate patient education into the plan. When mucosa are injured as a result of chemical trauma from chemotherapy, techniques for cleaning and hydrating inflamed tissues and eliminating sources of irritation will be the focus of nursing care. Box 34-4 summarises possible nursing diagnoses that apply to patients in need of hygiene care.

PLANNING

During planning, the nurse synthesises information from multiple resources (Figure 34-6). Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates all that the nurse knows about the individual patient and key critical-thinking elements. Previous experience with other patients can be very useful in knowing how to adapt hygiene techniques for special needs. Professional standards are especially important to consider when the nurse develops a plan of care. These standards often establish scientifically proven guidelines for effective nursing interventions. For example, Diabetes Australia’s guidelines are valuable for preventive foot care in diabetic patients (see Online resources).

Goals and outcomes

The nurse develops an individualised plan of care for each of the patient’s nursing diagnoses (see Sample nursing care plan). The nurse and patient work together to identify goals and expected outcomes. Goals are established with the patient’s self-care abilities and resources in mind. Outcomes should be measurable and achievable within patient limitations. The nurse works further with the patient to then select hygiene measures that are appropriate and realistic. For example, a goal for self-care deficit hygiene might be: ‘The patient will complete his own hygiene care with supervision within 1 week.’ The expected outcomes would be ‘remains free of body odour, states satisfaction with the ability to use aids in the shower and bathes with minimal assistance in and out of shower’.

HYGIENIC CARE

ASSESSMENT*

Mrs Wyatt is a 57-year-old who has had multiple sclerosis for 10 years. She was recently hospitalised for an acute exacerbation of the disease. The nurse, Jeannette, makes the initial home visit for Mrs Wyatt. Jeannette’s assessment reveals that Mrs Wyatt has reduced hearing, requiring Jeannette to speak clearly and to stand so Mrs Wyatt can see her lip movements. Mrs Wyatt is married, but her husband, Lon, works full-time during the day. Her sister comes over periodically to help with her care and household chores. Mrs Wyatt has muscular weakness of both upper extremities, making it difficult for her to raise her arms above her shoulders. She has some foot dragging and ataxia (unsteady gait), so she bathes in a chair placed in front of the bathroom sink. Recently her sister has helped with bathing. With some spasticity in her right dominant arm, Mrs Wyatt has difficulty grasping objects. Jeannette arranged her assessment in the morning to observe Mrs Wyatt bathe. She had increased spasticity while bathing and became very fatigued after only about 5 minutes. Mrs Wyatt continues to be very independent in making decisions about her care. She tells Jeannette, ‘It is important for me to be able to bath myself.’

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: Self-care deficit, bathing/hygiene related to muscle spasticity and fatigue.

PLANNING

| GOALS | EXPECTED OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

| Patient will be able to perform self-bathing without assistance within 1 month. |

| INTERVENTIONS† | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Energy management | |

| Will minimise occurrence of fatigue. | |

| Self-care assistance | |

| Easy access to equipment will reduce muscle fatigue. | |

| Decrements in the ability to perform gross motor function over time indicate need for aids and a modified environment to help control symptoms and to make activities of daily living easier to perform. | |

| Stretching prevents muscle contraction and reduces muscle spasms. |

†Intervention classification labels from Bulechek GM and others 2008 Nursing interventions classification (NIC), ed 5. St Louis, Mosby.

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

The patient’s condition influences the plan for delivering hygiene. A seriously ill patient usually needs a daily bath because body secretions accumulate and can become a source of infection. An older patient at home may require a visit from a home health aide to help with a bath. Patients who are normally inactive during the day and have skin that tends to be dry may need to bathe only twice a week. Timing is also important in planning hygiene. Being interrupted in the middle of a bath to go to an X-ray examination can frustrate and embarrass a patient. Following extensive diagnostic tests (e.g. a stress test), it may be best to delay hygiene and allow a patient to rest. In the home, bathing may be planned to refresh the patient before daily activities. The nurse should try to plan hygiene around tests, procedures and patient needs. This can be difficult in a hospital because tests are often not scheduled for specific times.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Mr Wilkes is a 54-year-old patient with advanced stages of lung cancer. The tumour has spread to the bone, causing Mr Wilkes considerable pain and predisposing him to pathological fractures (fractures that result when bone is weakened by tumour growth). The patient has been experiencing a high fever almost daily. What might you consider in anticipating Mr Wilkes’s hygiene needs?

When a patient needs assistance as a result of a self-care limitation, the family becomes a valuable resource to the nurse. Family members can usually help with hygiene measures but may need guidance in adapting techniques to fit patient limitations. In devising a plan that involves family members, the nurse tries to match the family’s schedule of availability with patient needs. It is also important to have the family member with whom the patient is most comfortable routinely involved (Paquay and others, 2010).

Setting priorities

Although hygiene needs are not the top priority for saving lives, for patients these needs are often a higher priority than nurses perceive them to be. The discomfort and lowered self-esteem of knowing that your body odour is offensive or that your teeth feel thick and you have halitosis or that your skin is sweaty and uncomfortable cause hygiene needs to assume a high priority.

Continuity of care

Discharge planning involves alerting the community nurse to the patient’s needs and functional ability. Information sharing is crucial to patients receiving seamless care from hospital to home. Social workers may need to become involved to provide funds for home aids or alterations. Occupational therapists are able to assess the patient’s home environment and suggest changes that would improve independent living. The nurse must plan for necessary assistance for patients who are weakened or possess poor coordination. For example, a partially paralysed patient who has had difficulty getting out of a bath should have a bath chair, handrails, a handheld shower or extra people available to help.

The nurse may need various community resources in planning hygiene care. For example, the nurse involved in the care of a homeless patient may need to be aware of the location of clothing distribution centres for basic hygiene supplies or a shelter where bathing facilities are available. Frequently the nurse will consult with social workers or staff in local churches and schools to be sure patients have the resources they need to maintain hygiene.

IMPLEMENTATION

Providing hygiene is a very basic but important part of a patient’s care. The nurse learns to use caring practices that help to alleviate the patient’s anxiety and promote comfort and relaxation while performing each hygiene measure. For example, while giving a patient a bath and changing a gown, the nurse uses a gentle approach in turning and repositioning. Using a soft, gentle voice while conversing with the patient helps to relieve any fears or concerns. For patients suffering symptoms such as pain or nausea, administering symptom relief therapies prior to hygiene will better prepare the patient for any procedure.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Thanos is an 18-year-old admitted to the neurosurgical intensive care unit following a head injury. He is currently unconscious, responsive only to painful stimulus. What assessment is critical for the nurse to perform before providing oral hygiene?

Another important part of implementation is assisting and preparing patients so that they are able to administer their own hygiene. This includes educating patients in proper hygiene techniques and connecting patients with the community resources necessary to enable them to perform hygiene care. Patients at risk of hygiene problems are the ones in greatest need of understanding their risks, knowing the implications and then having the information they need to make choices about when and how hygiene is performed.

Health promotion

In primary healthcare settings, nurses educate and counsel patients and families on proper hygiene techniques. A new mother will need help to learn how to bath her newborn infant. An older adult will need to be informed about the importance of regular ear care to avoid any hearing deficits resulting from accumulated cerumen. The hygiene skills described throughout this chapter provide standards for excellent physical care. When helping patients, the nurse tries to maintain these standards and incorporate adaptations as needed to the patient’s lifestyle, living arrangements and preferences. Tips to help the nurse educate patients about hygiene include the following.

• Make instructions relevant. After assessing a patient’s knowledge, motivation, health beliefs and ability/capacity for self-care, provide information that relates to the patient’s situation and which will be most useful in resolving the patient’s problem. For example, when offering foot care instruction to a patient with diabetes mellitus, explain how the circulation to the feet can be impaired and when the skin becomes cut or broken this poses a risk for poor healing and infection.

• Adapt instruction of any techniques to the patient’s personal bathing facilities. Not all patients will have the ideal situation that exists in a healthcare setting (e.g. easily accessible shower or a bedside table to place over a bed). Use what facilities or equipment the patient has so that personal care items are easy to reach, the patient’s safety is ensured and the patient feels comfortable in performing hygiene. For example, a young mother may feel that bathing an infant will be safer (with more room) if she uses her kitchen sink and counter rather than her bathroom sink.

• Be sure to teach the patient steps to take to avoid injury. Almost any hygiene procedure can pose risks (e.g. cutting a nail too close to the skin, failing to adjust the water temperature of the bath or using tap-water for contact lens care). Any instruction must clearly outline safety risks.

• Reinforce infection control practices. Damage to the skin, mucosa, eyes or other tissues creates an immediate risk of infection. Be sure the patient understands the relationship between healthy and intact skin and tissues and the prevention of infection.

Acute and restorative care

In healthcare settings where patients receive direct nursing care, nurses provide a variety of hygiene measures. Box 34-5 describes the different hygiene care schedules commonly found in acute care and extended-care settings. Times may change because of factors affecting the nurse’s organisation or scheduling of care, such as patient preferences, planned diagnostic and treatment procedures, the patient’s need for more hygiene, or the nurse’s work assignment. In extended-care facilities and nursing homes, the schedule for hygiene may be less frequent.

BOX 34-5 HYGIENE CARE SCHEDULE IN ACUTE CARE AND EXTENDED-CARE SETTINGS

EARLY MORNING CARE

Nursing personnel on the night shift provide basic hygiene to patients getting ready for breakfast, scheduled tests or early-morning surgery. This includes offering a bed pan or urinal if the patient is not mobile, washing the patient’s hands and face and helping with oral care.

MORNING, OR AFTER-BREAKFAST, CARE

In care performed after breakfast, the nurse helps by offering a bed pan or urinal to patients confined to bed; providing a bath or shower; providing oral, foot, nail and hair care; giving a back rub, changing the patient’s gown or pyjamas; changing the bed linen; and straightening the patient’s bedside unit and room.

AFTERNOON CARE

Hospitalised patients often undergo many exhausting diagnostic tests or procedures in the morning. In rehabilitation centres, patients may participate in physical therapy during the morning. Afternoon hygiene care includes washing the hands and face, helping with oral care, offering a bed pan or urinal and straightening bed linen.

EVENING, OR HOUR-BEFORE-SLEEP, CARE

Before bedtime, the nurse offers personal hygiene care that helps a patient relax to promote sleep. This may include changing soiled bedclothes, gowns or pyjamas; helping the patient wash the face and hands; providing oral hygiene; giving a back massage; and offering a bed pan or urinal to non-mobile patients. Some patients may enjoy a drink such as juice.

BATHING AND SKIN CARE