Chapter 23 Dimensions of self: pathways to self-identity

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Explain the five components of self: identity, body image, self-esteem, roles and spirituality.

• Define the components of what constitutes a healthy self as related to psychosocial and cognitive stages of development.

• Discuss the relationship of spirituality to an individual’s conception of self.

• Describe the relationship between faith, hope, trust and spiritual wellbeing.

• Identify most commonly recognised spiritual needs.

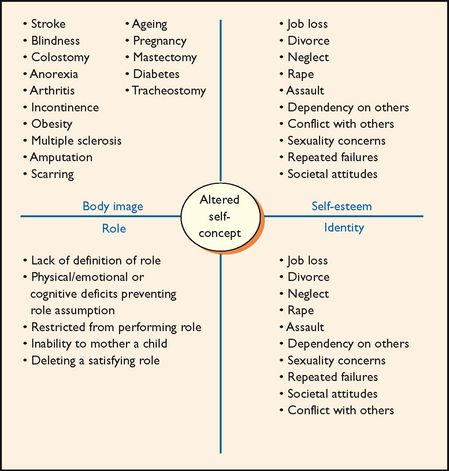

• Describe stressors that can affect a person’s perception of self.

• Describe behaviours indicating identity confusion, disturbed body image, low self-esteem, role conflict and spiritual distress.

• Identify and discuss ways in which nursing activities can affect the client’s perception of self.

• Discuss nursing interventions designed to promote spiritual healing and spiritual health.

• Identify important aspects of culture that affect nursing care in support of clients’ conception of self.

Relationship with oneself is the most intimate relationship and one of the most important aspects of life experience, yet it is one of the most difficult to define. What we think and feel about ourselves affects the way in which we care for ourselves and others physically, psychologically, emotionally and spiritually. People with a poor conception of self often do not feel a sense of personal worth, which influences whether they seek physical, emotional and spiritual help as the need arises.

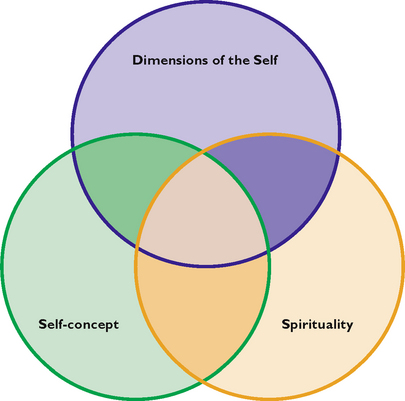

Dimensions of the self

The ways in which a person comes to know and understand themself as a unique individual is primarily determined by two key elements: self-concept and a person’s spirituality. Self-concept is an individual’s awareness about the self (e.g. ‘I am good at maths’) (Stein-Parbury, 2005), while a person’s spirituality is concerned with a search for meaning, purpose and interconnectedness with self, others/nature and possibly an ultimate other.

A person’s conception of self as a unique individual has its origins in the psychic representation of an individual, the central core of ‘I’ around which all perceptions and experiences are organised. It is developed through a range of processes involving five key elements—identity, body image, self-esteem, role performance and one’s spirituality. The development of a person’s conception of self is a dynamic combination formulated over years and based on the following:

• reactions of others to one’s body

• ongoing perceptions of the reactions of others to the self

• relationships with self and others

• perceptions of stimuli that have an impact on the self

• present feelings about the physical, emotional, social and spiritual self

A positive conception of self gives a sense of continuity, wholeness and consistency to a person. A healthy conception of self has a high degree of stability despite the person experiencing either positive or negative feelings towards the self. Being ‘oneself’ is the crux of a healthy self in all its dimensions (Edward and others, 2011).

The five dimensions that constitute self—identity, body image, self-esteem, role performance and the spiritual self or a person’s spirituality—form the basis of an individual’s overall sense of who they are as a human being (see Figure 23-1).

Identity

Identity involves a person’s sense of individuality, wholeness and consistency in various life circumstances over time. The concept of identity thus includes constancy and continuity. Identity implies being distinct and separate from others—being able to view oneself as a unique individual.

Identity develops over time. A child learns culturally accepted values, behaviours and roles through identification. The child first identifies with parenting figures and later with teachers, peers and heroes. To form an identity, the child must be able to bring together learned behaviours and expectations into a coherent, consistent and unique whole (Erikson, 1963).

The achievement of identity is necessary for intimate relationships because one’s identity is expressed in relationships with others. Sexuality is a part of one’s identity. Sexual identity is a person’s image of the self as a man or a woman and the meaning of this image. This image and its meaning are influenced by sociocultural values that are learned through socialisation (see Chapter 24).

Body image

Body image is an individual’s mental picture of their physical appearance. It includes a person’s feelings and attitudes towards the body. These images are not necessarily consistent with the actual body structure or appearance. Body image may change within a few hours, days, weeks or months, depending on the impact of external stimuli on the body and actual changes in appearance, structure or function. Body image is also influenced by personal views of physical characteristics and abilities and by perceptions of others. For example, a controlling, violent husband might tell his wife that she is ugly and that no one else would want her. Over the years of marriage, she believes this image of herself and incorporates it into her self-concept.

Body image is affected by cognitive development and physical growth. Normal developmental changes such as physical growth and ageing have a more apparent effect on body image than on other aspects of self-concept (Saucier, 2004). Hormonal changes during adolescence and menopause influence body image. Changes associated with ageing (e.g. wrinkles, greying hair and decrease in visual acuity, hearing and mobility) may also affect body image.

Cultural and societal attitudes and values also influence body image (Cafri and others, 2005) (see Working with diversity). In Australian society, youth, beauty and wholeness are emphasised—a fact apparent in television programs, movies and advertisements. Western cultures have been socialised to accept the normal ageing process as a part of life, whereas in Eastern cultures ageing is viewed very positively and the older adult is respected.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

Culture influences what people tend to value in their lives. How people think about themselves, what motivates them and how they behave are all related to the culture within which people are socialised. In order to provide culturally safe care, healthcare professionals need to be aware of the significance of culture to a person’s health and wellbeing. This involves becoming culturally aware and responding to the cultural needs of individuals and their families. It is important to remember that a person’s cultural needs and spiritual needs are intertwined. This means that in providing culturally safe care, the spiritual needs of the person must be considered.

Body image depends only partly on the reality of the body. When physical changes occur, people may or may not incorporate these changes into their body image (Landa and Bybee, 2007). Often, for example, people who have experienced significant weight loss do not perceive themselves as thin. Older adults often report that they do not feel different despite such changes as wrinkled skin or greying hair.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem is an individual’s sense of self-worth. It is influenced by both self-evaluation and the responses of others. According to Erikson (1963), young children begin to develop a sense of usefulness or industry by learning to act on their own initiative. A child’s self-esteem is related to the child’s evaluation of their effectiveness at school or work, within the family and in social settings. The evaluation of others is also likely to have a profound influence on the child’s self-esteem. A person’s family and society in general set the standards by which individuals evaluate themselves. A child who excels in school and who is liked by peers is likely to have high self-esteem, whereas a child who has difficulty in school and is not liked by peers is likely to develop low self-esteem.

Understanding self-esteem can be enhanced by considering the relationship between a person’s self-concept and the ideal self. The ideal self consists of the aspirations, goals, values and standards of behaviour that a person considers ideal and strives to attain. The ideal self originates in the preschool years and develops throughout life. It is influenced by societal norms and the expectations and demands of parents and significant others. In general, a person whose self-concept comes close to matching the ideal self has high self-esteem, whereas a person whose self-concept varies widely from the ideal self has low self-esteem.

A person’s perception of self is based on gender, age, perceived health status, background, family roles, occupation, social roles and use of leisure time. Basic feelings about the self tend to be constant, even though there is some fluctuation, with good and bad days. An individual’s self-perception does not necessarily match the perceptions of others. Self-evaluation is an ongoing mental process. A positive sense of self-worth, or self-esteem, is a basic human need, according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1954). People’s self-esteem affects their self-concept and how they function in the world.

A person’s ability to contribute in a meaningful way to society often affects their self-concept and self-esteem. Individuals who are sick and unable to be involved in society may feel a sense of worthlessness (Fung and others, 2006; Luxton and others, 2006). The nurse’s acceptance of a client as an individual with worth and dignity can be vital in maintaining and improving the client’s self-esteem.

Role performance

Role performance is concerned with the roles individuals assume or follow in given situations and involves expectations or standards of behaviour that they have developed over time. An individual develops role behaviour based on patterns established through socialisation. Socialisation begins just after birth, when an infant responds to adults and adults respond to the infant’s behaviours. The patterns of behaviour established in early life change only minimally during adulthood. A child learns behaviours that are approved by society through the following processes (Parsons, 1951):

• Reinforcement–extinction: certain behaviours become common or are avoided, depending on whether they are approved and reinforced or discouraged and punished.

• Inhibition: a child learns to refrain from behaviours, even when tempted to engage in them.

• Substitution: a child replaces one behaviour with another, which provides the same personal gratification.

• Imitation: a child acquires knowledge, skills or behaviours from members of the social or cultural group.

• Identification: a child internalises the beliefs, behaviour and values of role models into a personal, unique expression of self.

Through the process of socialisation, a child generally develops the skills necessary for functioning in many different roles. Unsuccessful socialisation is an inability to function according to society’s values.

Ideal societal role behaviours are often hard to live out in real life where individuals have multiple roles and individual needs. Successful adults learn to distinguish between ideal role expectations and realistic possibilities. To function effectively in roles, people must know the expected behaviour and values, must want to conform to them and must be able to meet the role requirements. Most individuals have more than one role. Common roles include mother or father, wife or husband, daughter or son, employee or employer, sister or brother, and friend. Each role involves meeting certain expectations. Fulfilment of these expectations leads to rewards. Difficulty or failure in meeting role expectations often contributes to decreased self-esteem.

Role performance is the way people perceive their competency in carrying out significant roles (Sargent, 2003). An individual’s perception of competency may or may not match the evaluation of others who relate to the person.

Spirituality

The word spirituality derives from the Latin word spiritus, which refers to breath or wind. The spirit gives life to, or animates, a person. It signifies whatever is at the centre of all aspects of a person’s life, including a sense of self (Elder and others, 2009). The human spirit is a powerful force that defines our existence, offers a source of hope and helps to achieve inner harmony (Edward and others, 2011).

Spirituality is a concept that is unique to each individual. People’s definitions of their own spirituality are influenced by their culture, development, life experiences, beliefs and ideas about life. A person’s spirituality enables the person to love, have faith and hope, seek meaning in life and to nurture relationships with others. Spirituality offers a sense of connectedness intrapersonally (connected within oneself), interpersonally (connected with others and the environment) and transpersonally (connected with what a person may perceive as a higher power). Elements of spirituality often found in the literature include spiritual health, spiritual needs and spiritual awareness. Berman and others (2010) describe spiritual wellbeing as a force that provides meaning and purpose in life and a sense of harmony between self, others/nature and an ‘Ultimate Other’, which exists throughout and beyond time and space. There are two important characteristics of spirituality about which most authors agree: it is a unifying theme in people’s lives, and it is a state of being.

There are people who either do not believe in the existence of a god (atheist) or who do not believe in any ultimate meaning for the way things are (agnostic). However, this does not mean that spirituality is not an important concept for the atheist or agnostic. Atheists often search for meaning in life through their work and their relationships with other people. They also tend to believe in a joint responsibility for others. In acting for themselves, they feel they should also act for all humankind. In the case of agnostics, it is important for them to discover or find meaning in what they do or how they live. Spirituality can be viewed from other perspectives, including faith, religion and hope.

Faith

The concept of faith has two definitions in the literature. In the first, faith is defined as a cultural or institutional religion, such as Judaism, Buddhism, Islamism or Christianity. (Faith as a religion is described in the next section.) The second deals with faith as a relationship with a divinity, higher power, authority or spirit that incorporates a reasoning and a trusting faith (Doucet, 2008). A reasoning faith deals with a person’s belief and confidence in something for which there is no proof. It is an acceptance of what reasoning cannot reach. However, faith is also manifest in the manner in which a person chooses to live life. Faith in this sense enables action. For example, a person might believe that having a positive outlook on life is the best way to achieve life’s goals. The belief that comes with faith involves transcendence, or an awareness of that which one cannot see or know in ordinary physical ways. It gives purpose and meaning to a person’s life. A trusting faith deals with the inner resources that allow a person to act. For example, clients with cancer who have faith in a positive outlook on life might search out more knowledge about their disease and continue to pursue daily activities rather than resign themselves to the disease’s symptoms.

Religion

Emblen (1992) defines religion as a system of organised beliefs and worship that a person practises to outwardly express spirituality. Many people hold a faith or belief in the doctrines and expressions of a specific religion or sect, such as the Anglican church within Christianity or the Orthodox Jewish faith. Religion serves different purposes in people’s lives. For some, religion is a set of rules and rituals used to worship a supreme being. For others, religion is a way of life providing nourishment and a connectedness to all life. In this latter context, religion is more directly associated with spiritual wellbeing. Religion is the system that may form the basis of and nurture some people’s spirituality. Many people are spiritual without being religious, and some people may be religious without being overtly spiritual. The writings and lives of leaders such as Gandhi are rich in spiritual material that may be influential for others in their spiritual quest. In the literature, spirituality and religiosity are often referred to as being synonymous, but for an accurate assessment of clients’ spiritual needs it is important for the nurse to realise that they are not the same and to be able to make that distinction (Baldacchino and Draper, 2001).

Hope

Spirituality is often identified as a key element in hope. When a person has the attitude of something to live for and look forward to, hope is present. Miller and Powers (1988) describe hope as a multidimensional concept consisting of anticipation of a continued good, an improvement or the lessening of something unpleasant. Hope is energising, giving people a motivation to achieve and the resources to use towards that achievement. It is an invaluable personal resource whenever someone is faced with a loss (Chapter 25) or a challenge that seems difficult to achieve. Hope has purpose and direction and gives reason for being (Berman and others, 2010). Loss of hope can give way to spiritual distress in which the person feels abandoned and left with no direction or sense of purpose.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

Spirituality is not limited to the concepts of faith, religion and hope from a religious perspective, but is also present within the context of culture. There are numerous cultural groups throughout the world whose sense of the spiritual is not aligned with religion but with their cultural heritage, identity, connection to the land and language group. Evidence of cultural alignment to a person’s sense of spirituality can be found in such cultural groups as the North American Indians, Māri, and Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders. Each of these cultural groups has a rich repository of spiritual beliefs that play a significant role in daily life, illness, health and healing. Premonitions, apparitions and visitations are points of connection with the spirit world—both past and present (Eckermann and others, 2006).

From the perspective of Māri culture, which embodies both a belief in a deity and a spiritual bonding with the earth, spirituality overarched both of these notions. Connection with a deity was achieved through the use of a godstick which was used by a priest or qualified person of the community for ritualistic occasions to speak to the spirit of a particular god. In relation to connecting with the land, many of New Zealand’s geographical features have spiritual meaning and are important anchors in defining self. Underpinning Māri culture is the belief that each human being has a spiritual essence which is connected to the person, nature, land, and objects made by man.

Eckermann AK, Dows T, Chong E and others 2006 Binan Goonj: bridging cultures in Aboriginal health, ed 2. Sydney: Elsevier.

Research focus

During the last few decades a large and growing body of research has emerged examining the relationship between spirituality and health. Williams and Sternthal (2007) provide a review of the empirical evidence linking measures of spirituality or religious involvement to health, with an emphasis on recent Australian research.

Research findings

• Levels of spirituality and religious beliefs and behaviour are relatively high in Australia, although lower than those in the United States.

• There is mounting scientific evidence of a positive association between religious involvement and multiple indicators of health.

• The strongest evidence exists for the association between religious attendance and mortality, with higher levels of attendance predictive of a strong, consistent and often graded reduction in mortality risk.

• Negative effects of religion on health have also been documented for some aspects of religious beliefs and behaviour and under certain conditions.

• Health practices and social ties are important pathways by which religion can affect health. Other potential pathways include the provision of systems of meaning and feelings of strength to cope with stress and adversity.